↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models struggle to learn dynamical systems due to their physics-agnostic nature, leading to models that lack interpretability and robustness. This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on physical properties of systems. This paper addresses the issues with data efficiency and generalizability of existing machine learning models, particularly in contexts where physical laws and symmetries govern system behavior.

The authors introduce HHD-GP, a novel framework combining Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition with Gaussian Processes. HHD-GP simultaneously learns the curl-free and divergence-free components of a dynamical system, improving model interpretability and identifiability. Experiments show that HHD-GP achieves better predictive performance on benchmark datasets while also providing physically meaningful decompositions. The paper also introduces a symmetry-preserving extension of HHD-GP that further enhances performance and interpretability by leveraging inherent symmetries within systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly important because it presents a novel approach to learning dynamical systems by incorporating physical priors, addressing the limitations of traditional physics-agnostic methods. It offers improved predictive accuracy and interpretability, opening new avenues for research in various scientific domains and impacting fields like robotics and control systems.

Visual Insights#

The figure shows the vector field in phase space for a damped mass-spring system (a). The Helmholtz-Hodge Decomposition (HHD) of this vector field is also presented, showing its decomposition into a div-free (b) and a curl-free (c) component. This decomposition highlights that the div-free part represents the conservative dynamics of the system, while the curl-free part represents the dissipation caused by damping.

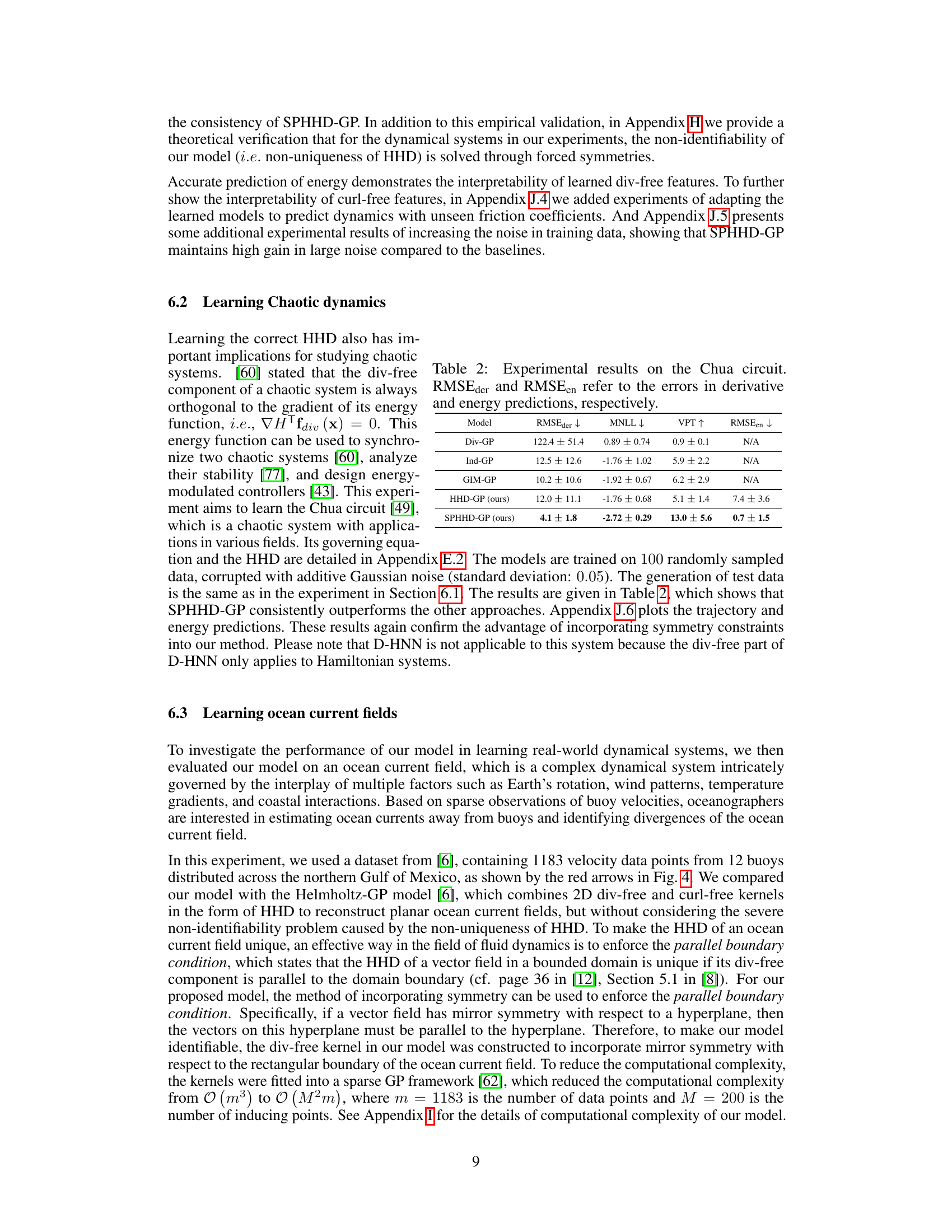

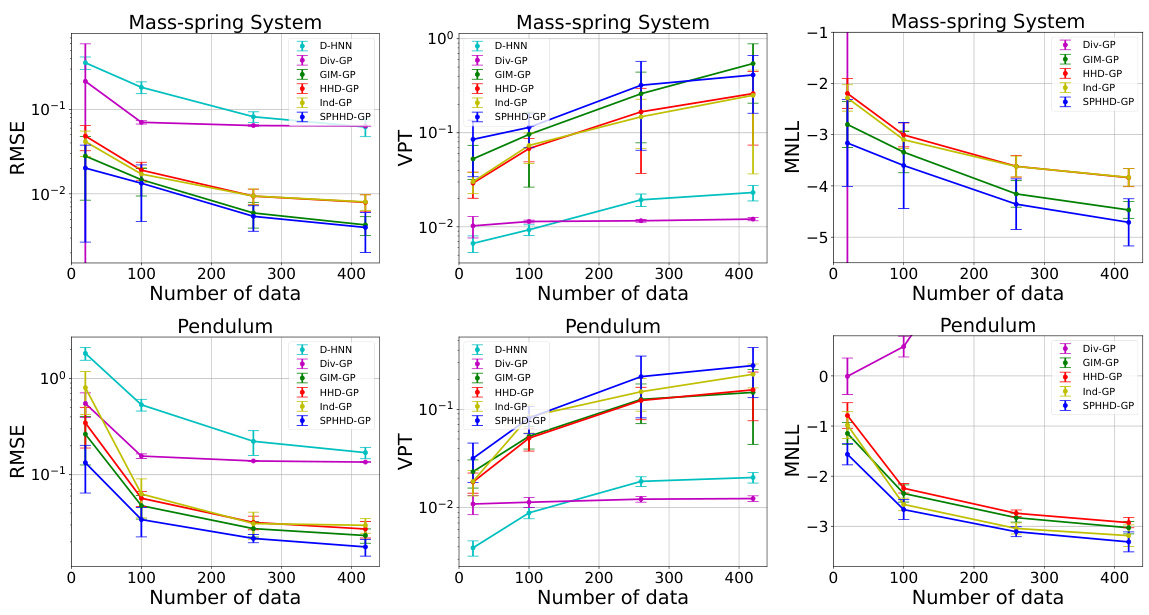

This table compares the performance of the proposed HHD-GP and SPHHD-GP models against several baseline models on two benchmark dynamical systems: a damped mass-spring system and a damped pendulum. The comparison is based on three metrics: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for derivative prediction, Valid Prediction Time (VPT) indicating the duration of accurate trajectory prediction, and Mean Negative Log Likelihood (MNLL) representing prediction uncertainty. The results are averaged over multiple independent experiments, showcasing the robustness and superior performance of the proposed models.

In-depth insights#

HHD-GP Framework#

The HHD-GP framework presents a novel approach to learning dynamical systems by integrating the Helmholtz-Hodge Decomposition (HHD) into Gaussian Processes (GPs). This framework is particularly powerful because it simultaneously learns both the curl-free and divergence-free components of a dynamical system, offering a more nuanced representation than traditional methods. This decomposition is valuable because it allows for the exploitation of symmetry priors, which improves predictive performance and enhances interpretability by linking identified features to physical system properties. The use of GPs provides a robust non-parametric framework for modeling, handling noise and uncertainty inherent in real-world data. Furthermore, the incorporation of symmetry-preserving extensions enhances the model’s identifiability, ensuring physically meaningful decompositions. The framework shows promise in handling noisy and sparse data, as demonstrated by experiments on benchmark systems.

Symmetry Priors#

Symmetry priors leverage the inherent structure of many physical systems to improve the efficiency and accuracy of machine learning models. By incorporating knowledge of symmetries into the model, we constrain the solution space, leading to better generalization and improved data efficiency. This is particularly useful when dealing with limited or noisy data, common challenges in modeling real-world dynamical systems. Symmetry-preserving kernels, for example, are designed to ensure that the model’s predictions are consistent with the underlying symmetries. This not only improves the accuracy of the model but also enhances interpretability, making it possible to connect the learned features to meaningful physical properties. However, careful consideration is needed to determine the appropriate symmetries for a given system and to ensure that the imposed constraints do not inadvertently restrict the model’s ability to capture the essential dynamics.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section in a research paper would present the findings obtained from experiments, offering concrete evidence to support the paper’s claims. A strong section would feature clear descriptions of the experimental setup, including datasets used and any preprocessing steps. Quantitative results should be presented with appropriate statistical measures (e.g., mean, standard deviation, confidence intervals), and visualizations like tables and graphs would enhance readability and impact. The discussion would interpret results in the context of the paper’s hypotheses, acknowledging limitations and uncertainties. Comparisons to relevant baselines would demonstrate the proposed method’s novelty and effectiveness. Overall, the section’s clarity, detail, and thoroughness are crucial to establishing the paper’s credibility and significance. Visualizations of results are essential in conveying trends and patterns effectively. The analysis must carefully consider potential confounding factors and biases that might influence the interpretations.

Identifiability Issue#

The identifiability issue arises from the inherent ambiguity in the Helmholtz-Hodge Decomposition (HHD), where a vector field can be decomposed into curl-free and divergence-free components in multiple ways. This ambiguity hinders the interpretation of learned features, making it difficult to link them to meaningful physical properties. The paper addresses this by introducing symmetry constraints into the Gaussian process model, improving the identifiability of the HHD components. Symmetry priors not only improve predictive performance but also constrain the solution space, ensuring that the decomposition is physically meaningful. Incorporating these constraints is crucial to make the decomposition unique and to obtain a physically interpretable model. This approach relies on the assumption that the underlying dynamical system exhibits certain symmetries which are leveraged to limit the set of possible HHD representations. The effectiveness of this strategy is demonstrated empirically by the improved performance and physically plausible decompositions obtained on several benchmark systems, showcasing how enforcing symmetry significantly enhances model interpretability and predictive power.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition (HHD) framework to a wider range of dynamical systems is crucial, especially those with complex interactions and non-linear behaviors. Investigating the theoretical connections between HHD and other powerful mathematical tools, such as Lyapunov functions, could lead to novel and efficient methods for analyzing system stability and control. Developing more sophisticated symmetry-preserving kernels for Gaussian processes to handle diverse and intricate symmetry groups in real-world datasets presents another rich opportunity. Finally, rigorous testing on larger-scale, real-world datasets, particularly from domains like fluid dynamics and climate modeling, is essential to validate the model’s generalizability and robustness, along with a thorough exploration of its computational efficiency and scalability challenges for increased practical impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

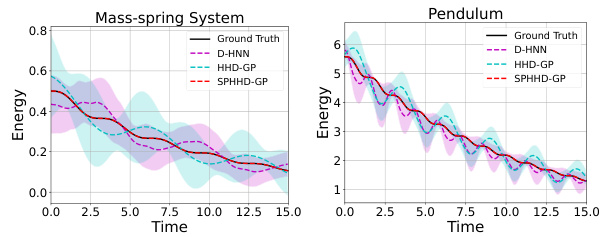

This figure shows the predicted energy evolution of two systems, mass-spring and pendulum. The predictions are compared to ground truth. The plot highlights the accuracy of SPHHD-GP in accurately predicting the energy which continuously decreases due to friction, unlike the other models which show oscillations.

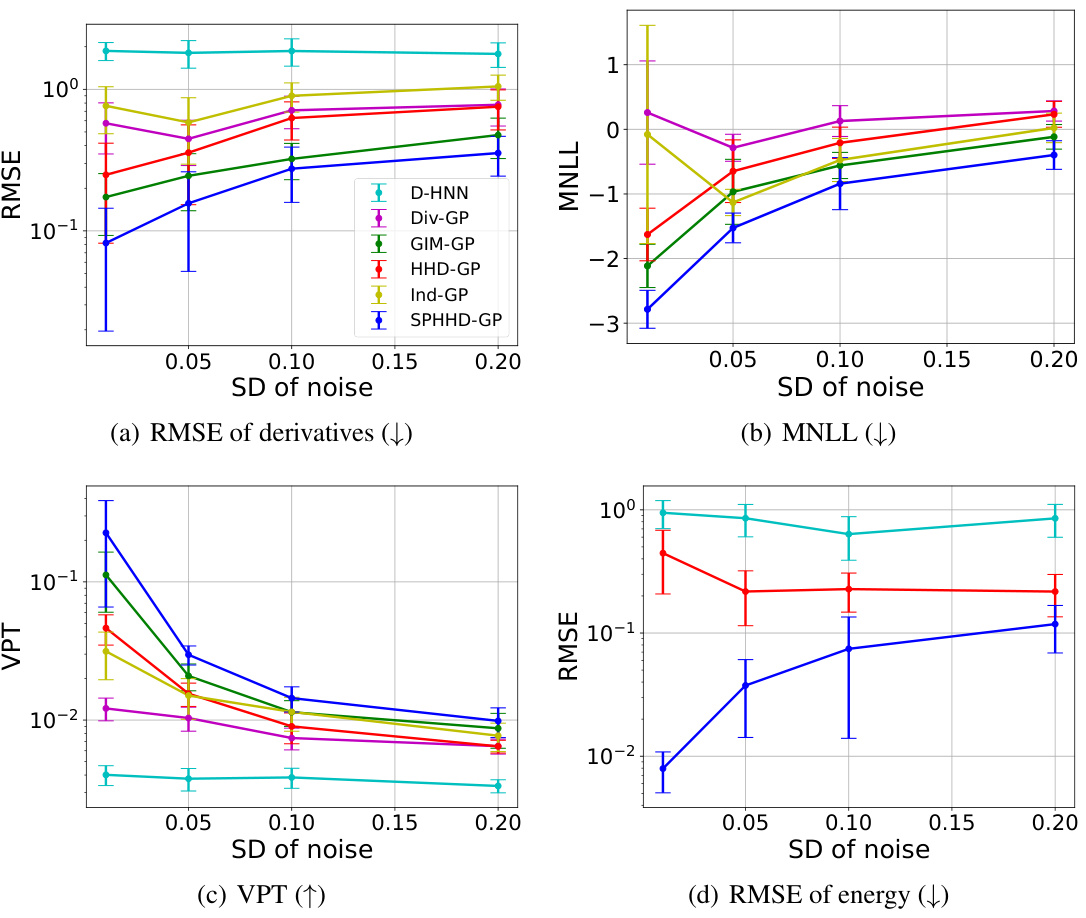

This figure shows the results of experiments with increasing standard deviation of Gaussian noise in training data. It presents four subplots: (a) RMSE of derivatives, (b) MNLL, (c) VPT, and (d) RMSE of energy. The plots show the performance of four different models (D-HNN, Div-GP, HHD-GP, and SPHHD-GP) across different noise levels. Error bars are included, indicating uncertainty. The results demonstrate the robustness of the SPHHD-GP model in the presence of noise.

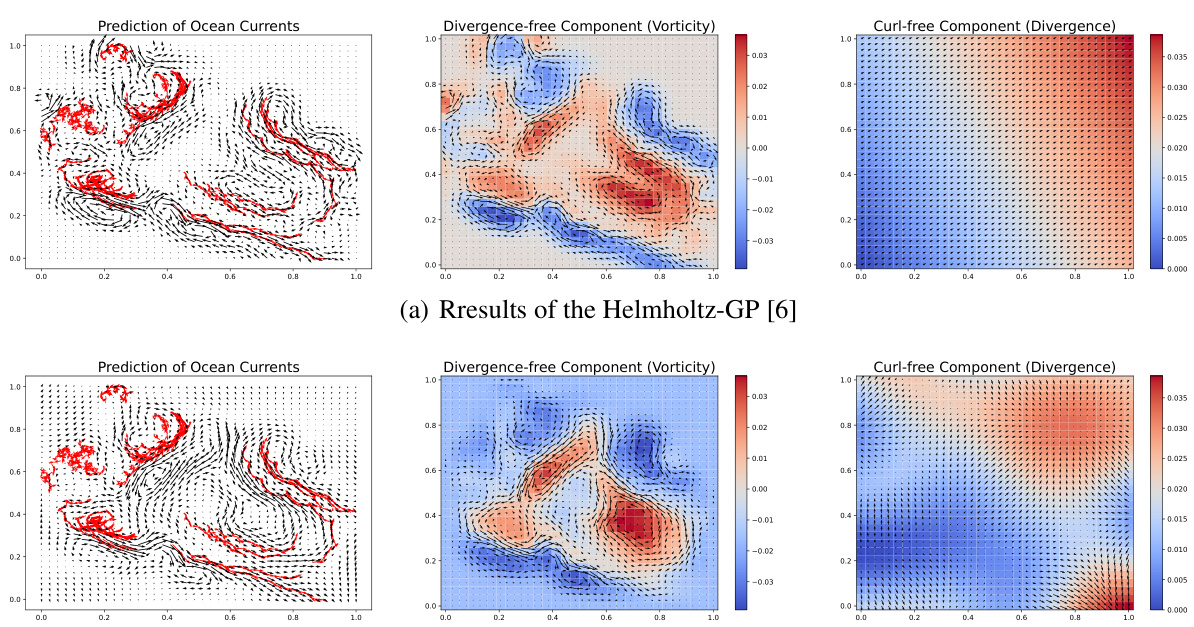

This figure compares the performance of Helmholtz-GP and SPHHD-GP on predicting ocean current fields and their Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition (HHD). The top row shows the results from Helmholtz-GP, while the bottom row shows the results from SPHHD-GP. Each row contains three subfigures: the first shows the predicted ocean current field (with black arrows representing the predicted current and red arrows representing the observed buoy velocities), the second shows the predicted vorticity field (divergence-free component), and the third shows the predicted divergence field (curl-free component). The comparison highlights SPHHD-GP’s superior ability to produce more realistic and continuous current predictions, along with a richer structure in the divergence field, unlike Helmholtz-GP, which shows an abrupt drop in regions distant from observed data.

This figure shows the Helmholtz-Hodge Decomposition (HHD) of the damped mass-spring system, comparing the results obtained using the HHD-GP and SPHHD-GP models. The first row presents the results of HHD-GP, while the second row illustrates the results obtained with the SPHHD-GP model. Each row consists of three columns: the first column shows the predicted vector field, the second shows the div-free component, and the third shows the curl-free component. The bottom row shows the associated variance for each component. This helps visualize how accurately each model predicts the components of the HHD and the uncertainty associated with the predictions.

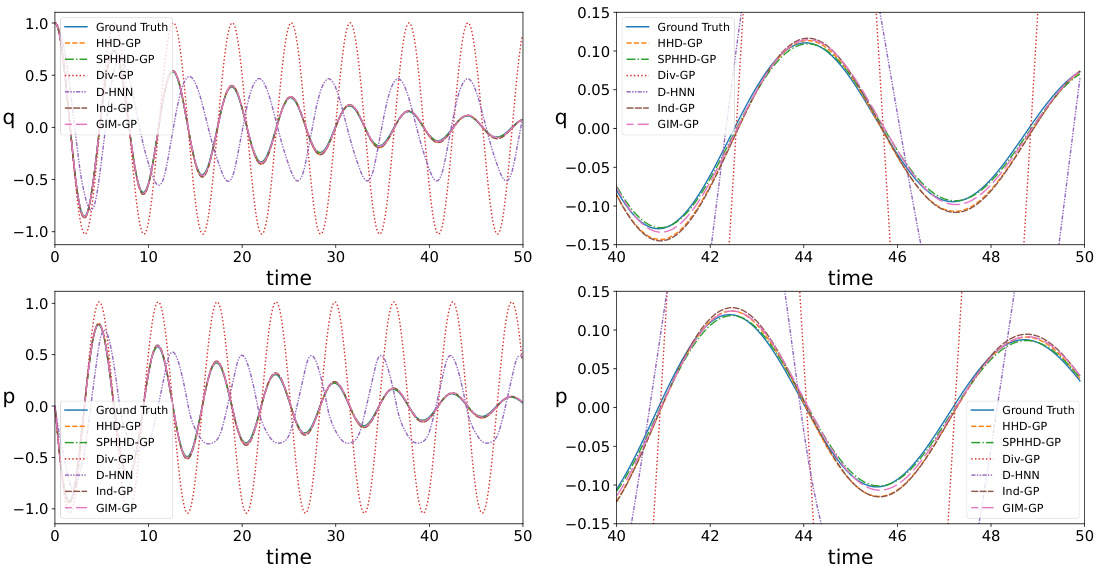

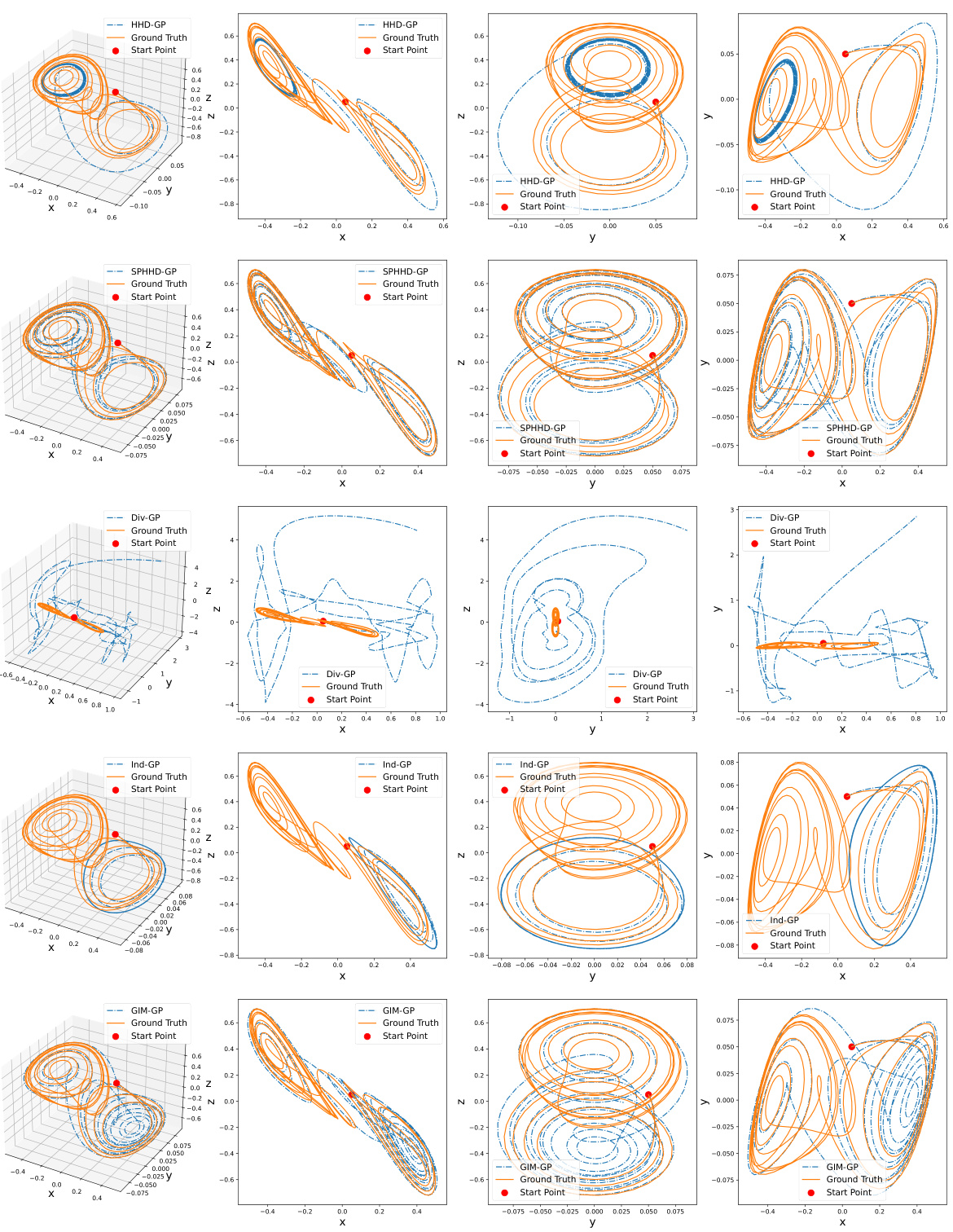

This figure compares the predicted trajectories of a damped mass-spring system generated by various models (Ground Truth, HHD-GP, SPHHD-GP, Div-GP, D-HNN, Ind-GP, and GIM-GP). The top row shows the position (q) and momentum (p) trajectories over a longer time horizon, while the bottom row zooms in on a shorter time interval to highlight differences. The figure aims to demonstrate the accuracy and generalization capabilities of the proposed HHD-GP and SPHHD-GP models in comparison to the baseline methods.

This figure compares the predicted trajectories of the damped mass-spring system generated by various models, including HHD-GP, SPHHD-GP, D-HNN, Div-GP, Ind-GP, and GIM-GP, against the ground truth. The plots show the system’s position (q) and momentum (p) over time. It demonstrates the performance of the different models in accurately capturing the system’s dynamics.

This figure shows the predicted Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition (HHD) of the damped mass-spring system using both HHD-GP and SPHHD-GP. The first row displays the results from the HHD-GP model, while the second row shows results from the improved SPHHD-GP model. Each row is divided into three columns. The first column shows the total predicted vector field. The second column represents the div-free part of the field, and the third column shows the curl-free part. The bottom row (b) shows the associated variance of the div-free (left) and curl-free (right) components of the predicted fields. The visualization helps compare the accuracy and uncertainty of the HHD produced by both models. The SPHHD-GP is shown to generate a more physically meaningful decomposition.

This figure shows the results of adapting the trained models to predict the trajectories of the damped mass-spring system and the damped pendulum under different friction coefficients. The models were initially trained with a friction coefficient of 0.1, and then their performance was evaluated with friction coefficients of 0.05 and 0.5. The figure demonstrates the models’ ability to generalize to unseen friction coefficients, highlighting the impact of incorporating physical principles into the model design.

This figure shows the results of an experiment that tested the robustness of different models to increasing levels of noise in the training data. The plots show the RMSE of derivatives, MNLL, VPT, and RMSE of energy for different models under different noise levels. The results indicate that SPHHD-GP is more robust to noise compared to other models.

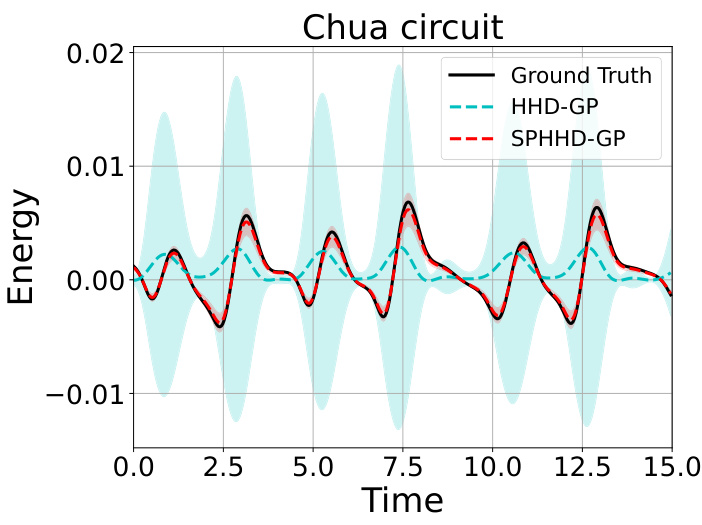

The figure shows the comparison of predicted energy of the Chua circuit by three different models: Ground Truth, HHD-GP, and SPHHD-GP. The SPHHD-GP model shows much better performance than the other two models, demonstrating its effectiveness in learning chaotic systems.

This figure compares the predictions of ocean current fields and their Helmholtz-Hodge decomposition (HHD) using two different methods: Helmholtz-GP and SPHHD-GP. The visualization shows the predicted current field using black arrows, the observed buoy velocities using red arrows, predicted vorticity fields, and predicted divergence fields in three columns. SPHHD-GP shows more continuous current predictions and a richer structure in the divergence field compared to Helmholtz-GP.

Full paper#