↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional hypothesis testing for discrete distributions, including uniformity, identity, and closeness testing, often requires many samples. The challenge lies in minimizing sample complexity while maintaining accuracy and robustness to noisy data. This paper addresses these issues.

The researchers developed new algorithms that incorporate predictions about the distribution. These algorithms adjust their sample complexity based on the prediction’s accuracy. Importantly, they perform at least as well as standard methods and are information-theoretically optimal. Experiments on both synthetic and real-world data demonstrate significant improvements exceeding theoretical guarantees.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in hypothesis testing and related fields because it offers significant improvements in sample complexity, a critical factor in many applications. The adaptability of the algorithms to prediction quality makes them more robust and practical, while the theoretical optimality guarantees provide a strong foundation for future research. This work also opens new avenues for leveraging prediction models in various testing problems.

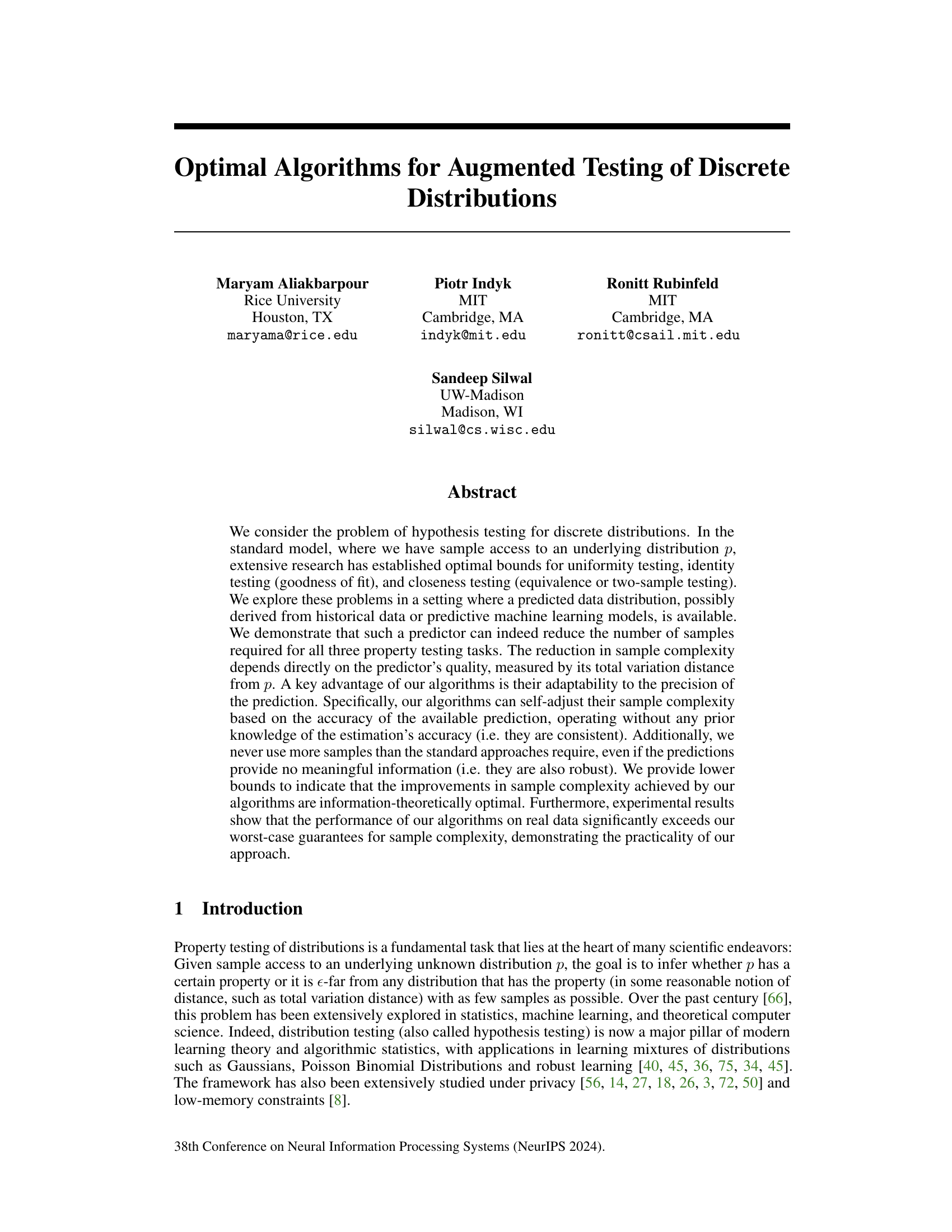

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the error rate (y-axis) of three different closeness testing algorithms plotted against the number of samples used (x-axis). The three algorithms are: the standard closeness tester, the augmented closeness tester (the algorithm proposed in the paper), and the CRS'15 algorithm (an existing algorithm that uses very accurate predictions). The graph demonstrates the superior performance of the augmented tester, particularly at lower sample counts. The CRS'15 algorithm shows consistently high error, indicating a lack of robustness to less-than-perfect predictions.

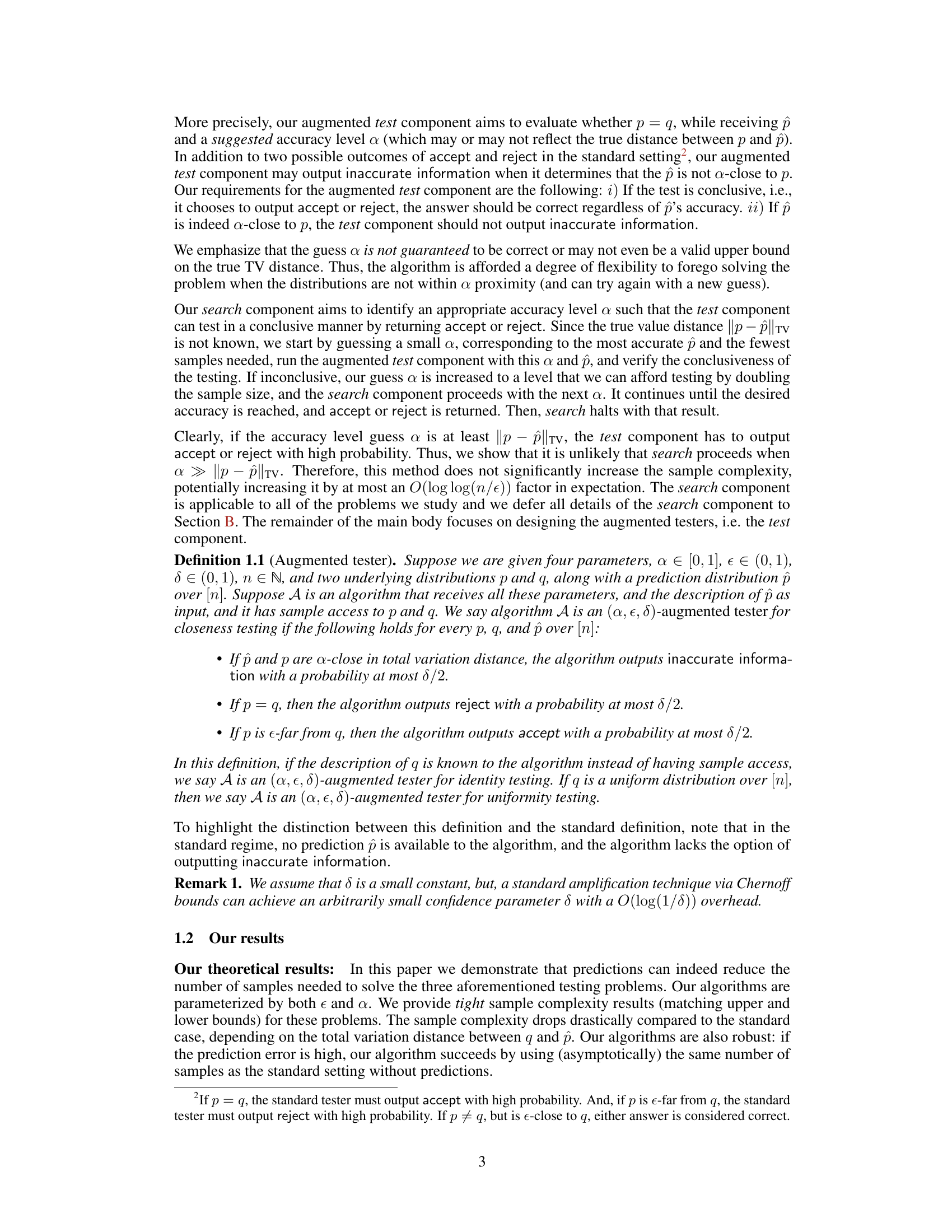

This table summarizes the sample complexities for closeness, identity, and uniformity testing in both standard and augmented settings. The standard setting assumes no prediction is available, while the augmented setting leverages a predicted distribution. The table highlights the optimal improvements in sample complexity achieved in the augmented setting, depending on the quality of the prediction, as measured by the total variation distance between the true and predicted distributions.

In-depth insights#

Augmented Testing#

The concept of ‘Augmented Testing’ in the context of the provided research paper signifies a paradigm shift in hypothesis testing for discrete distributions. It leverages prior knowledge or predictions about the underlying distribution to enhance testing efficiency. This augmentation is particularly valuable when dealing with real-world datasets, where complete a priori knowledge is often unavailable. The core idea revolves around incorporating a predicted distribution into the testing algorithm, thereby reducing the number of samples needed to achieve a given level of accuracy. The paper likely demonstrates that sample complexity reductions are directly tied to the quality of the prediction, offering optimal improvements when predictions are accurate and graceful degradation when they are not. This adaptability is a key strength, making the approach robust to imperfect predictions and still competitive with standard methods. Theoretical lower and upper bounds are likely established to quantify the effectiveness of the proposed approach and to demonstrate its optimality within an information-theoretic framework. Ultimately, ‘Augmented Testing’ offers a practical and powerful methodology for improving the efficiency and accuracy of statistical hypothesis testing in scenarios where some prior information about the distribution is available.

Prediction Leverage#

The concept of ‘Prediction Leverage’ in a research paper likely explores how effectively pre-existing predictions or estimations of a target distribution can improve the efficiency of subsequent statistical inference tasks. It likely investigates the reduction in sample complexity achievable when incorporating predictive information, and the trade-offs between prediction quality and algorithmic performance. The core focus would likely be on demonstrating that the integration of even imperfect predictions results in substantial improvements in efficiency, unlike approaches assuming perfect or near-perfect predictions. This likely involves developing novel algorithms that adapt their sample complexity and decision criteria according to the quality of the available prediction, making them robust and adaptive. The paper may also establish information-theoretic lower bounds to prove that these improvements are optimal in terms of sample complexity and would also present empirical evaluations on synthetic and real-world datasets to show the practical benefits and robustness of the approach. Overall, the section is likely to emphasize the practical applicability of incorporating predictive information in statistical inference, particularly in scenarios where some prior knowledge or learned prediction about the underlying distribution exists.

Optimal Bounds#

The concept of ‘Optimal Bounds’ in a research paper typically refers to the tightest possible limits on the performance of an algorithm or a statistical method. It signifies that no algorithm can perform significantly better than the upper bound, and no algorithm can perform worse than the lower bound, within the specified constraints of the problem. Establishing optimal bounds requires a two-pronged approach: proving an upper bound (showing the existence of an algorithm achieving that performance) and proving a lower bound (showing that no algorithm can improve beyond a certain limit). The significance of establishing optimal bounds is that they provide fundamental insights into the inherent complexity of the problem, helping researchers understand the best achievable performance and guide further algorithm design and analysis. Optimal bounds are a strong theoretical result, often offering stronger guarantees than empirical observations. The pursuit of optimal bounds drives the advancement of algorithms and our understanding of computational limits.

Empirical Robustness#

An empirical robustness analysis in a research paper would systematically evaluate the algorithm’s performance under various conditions beyond the ideal settings assumed in theoretical analysis. It would involve testing with noisy or incomplete data, exploring sensitivity to hyperparameter choices, and examining behavior across different data distributions or scales. A key aspect would be comparing the observed performance to theoretical guarantees or predictions. Deviations from these guarantees should be investigated and explained, highlighting algorithm strengths and weaknesses. The robustness study should cover a wide range of scenarios to build confidence in the algorithm’s reliability and practical applicability. Ultimately, the goal is to ascertain the algorithm’s resilience to real-world imperfections and unpredictability, demonstrating its practical utility.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle more complex prediction models beyond the current setting, which assumes access to all predictor probabilities, is a key area. Investigating the impact of noisy or incomplete predictions on the algorithm’s performance is also crucial. Developing adaptive algorithms that automatically adjust to the level of prediction accuracy without prior knowledge would improve the practicality of the approach. Finally, applying this augmented testing approach to broader classes of distributions and properties, beyond uniformity, identity, and closeness testing, warrants further exploration. This could involve analyzing different distance metrics or investigating properties that are not easily characterized by total variation distance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the decision boundaries for an augmented tester (A) in a hypothesis testing problem concerning two distributions, p and q. The total variation distance between the true distribution p and the predicted distribution p̂ is denoted as d. The parameter α represents the suggested accuracy level of the prediction and ε represents the minimum distance for which the algorithm can conclusively state that p and q are different. The figure shows that if the predicted distribution p̂ is within α distance of p, and p is equal to q, then the tester will output ‘accept’. If p and q are more than ε apart, the algorithm will output ‘reject’. If the prediction is not accurate enough, the algorithm might output ‘inaccurate information’.

This figure illustrates the valid answers for an augmented tester A in the identity testing problem. The green dot represents the case where p = q, requiring an ‘accept’ output from the standard tester. The red shaded area shows where ||p - q||TV ≥ ε, and ‘reject’ is the required output from the standard tester. The augmented tester’s additional ‘inaccurate information’ output is shown. The constraints on valid outputs are driven by total variation distances between distributions (p, q, and p̂).

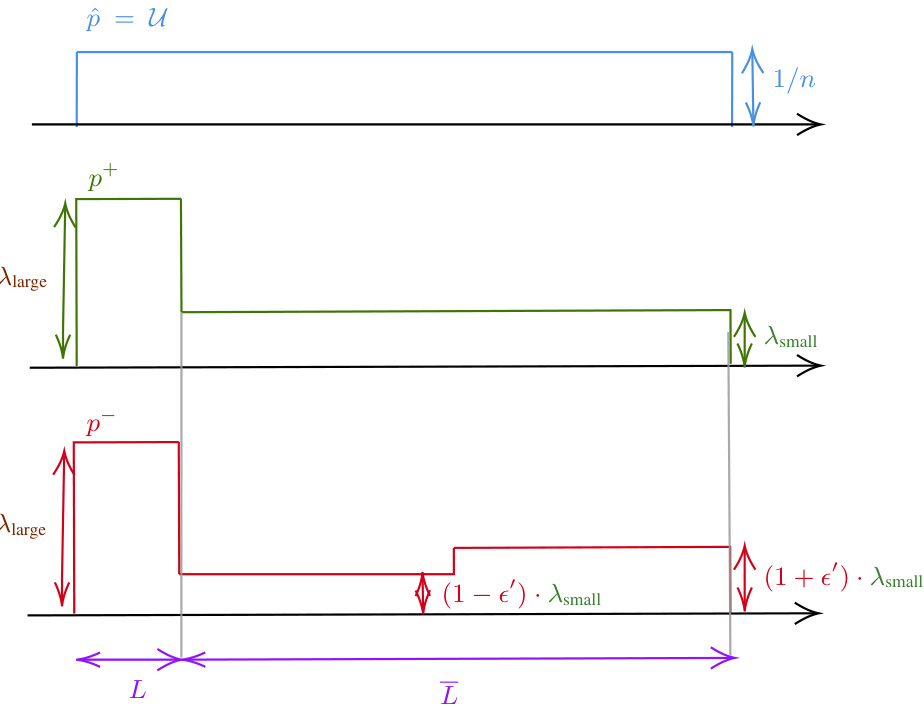

This figure visualizes three distributions: p, p⁺, and p⁻ over the domain [n]. The distribution p is uniform with a probability mass of 1/n for each element. p⁺ and p⁻ are constructed by modifying p. They have probability mass λlarge on their first l elements (set L) and λsmall on the rest (n-l) elements. p⁺ assigns a probability mass of (1+e’)λsmall to the elements of L1, and (1-e’)λsmall to the elements of L2. p⁻ assigns probability mass (1-e’)λsmall to the elements of L1, and (1+e’)λsmall to elements of L2. The visualization uses a step function to represent probability masses, clearly showing how p⁺ and p⁻ deviate from the uniform distribution p.

This figure shows the performance of the augmented tester algorithm on a synthetic dataset called ‘Hard Instance’ with varying prediction quality. The x-axis represents the total variation distance between the true distribution and the prediction (||p - p̂||tv). The y-axis shows the percentage error of the augmented tester. As the prediction quality decreases (||p - p̂||tv increases), the error rate of the augmented tester increases, indicating that the algorithm’s performance degrades with poorer predictions. However, even with relatively poor prediction quality, the augmented tester still outperforms the standard closeness tester.

This figure compares the empirical distributions of the estimator Z from the augmented and unaugmented closeness testers for the hard instance dataset. The left panel (a) shows the distribution of Z for the augmented tester, while the right panel (b) displays the distribution of Z from the unaugmented tester. In both panels, purple bars represent the case where p=q, and green bars represent the case where ||p-q||tv ≥ 1/2. The figure visually demonstrates the improved separation of the estimator Z in the two hypotheses for the augmented tester compared to the standard tester.

The figure shows the performance comparison of three algorithms on the IP dataset, focusing on error rate against the number of samples. The algorithms include the Closeness Tester (standard approach without prediction), the Augmented Tester (the proposed algorithm leveraging predictions), and CRS ‘15 (a state-of-the-art algorithm assuming almost-perfect predictions). Subfigure (a) presents the error rate vs. the number of samples. Subfigure (b) compares the performance of the Augmented Tester using two different predictors, p1 and p2, which vary in their accuracy. The results demonstrate the Augmented Tester’s improved efficiency and robustness compared to the baselines.

More on tables

This table summarizes the sample complexities for closeness, identity, and uniformity testing in both standard and augmented settings. The standard setting assumes no prediction is available. The augmented setting leverages a predicted distribution, and its performance is parameterized by the total variation distance (a) between the true and predicted distributions. The table shows that the augmented algorithms achieve optimal sample complexity improvements that directly depend on the quality of the prediction.

This table compares the sample complexities required for closeness, identity, and uniformity testing in two settings: the standard setting (without prediction) and the augmented setting (with prediction). It shows how the augmented setting’s sample complexity depends on the quality of the prediction (measured by the total variation distance between the true distribution and its prediction) and the suggested accuracy level.

Full paper#