↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional reinforcement learning (RL) struggles with generalization to unseen tasks due to limited training data. Integrating large language models (LLMs) offers a promising solution, but a semantic gap often exists between LLM outputs and RL actions. This paper tackles this limitation.

The proposed method, KALM, extracts knowledge from LLMs by generating imaginary rollouts that guide offline RL. To handle the text-based nature of LLMs and the numerical data of robotics environments, KALM fine-tunes the LLM for bidirectional translation between textual goals and numerical rollouts. Experiments showcase KALM’s ability to enable RL agents to tackle complex, novel tasks successfully, exceeding the performance of existing offline RL baselines.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and robotics because it bridges the gap between large language models (LLMs) and reinforcement learning (RL), a significant challenge in developing knowledgeable agents. It introduces a novel approach that significantly improves the success rate of agents in completing novel tasks, offering a promising direction for future research in integrating LLMs into RL systems for real-world applications. Its findings have implications for various fields such as robotics, automation, and human-computer interaction, prompting further investigation into more efficient and adaptable AI agents.

Visual Insights#

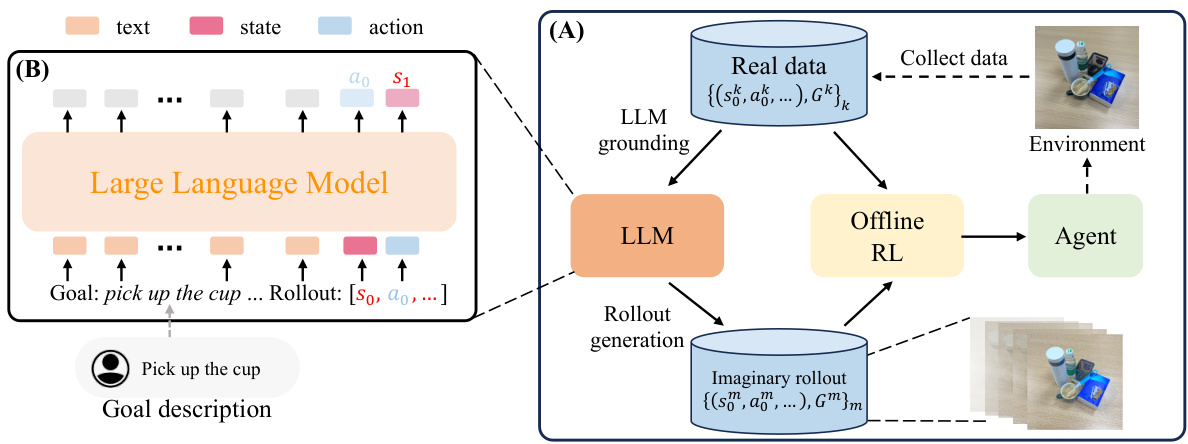

This figure illustrates the two main phases of KALM’s usage of LLMs: grounding and rollout generation. The grounding phase involves fine-tuning the LLM using supervised learning on environmental data (numerical vectors). This allows the LLM to understand and process the environment’s data. The rollout generation phase uses the grounded LLM to generate imaginary rollouts (sequences of states and actions) for novel tasks, based on textual goal descriptions. KALM modifies the LLM’s input/output layers to handle the numerical vector data of the environment.

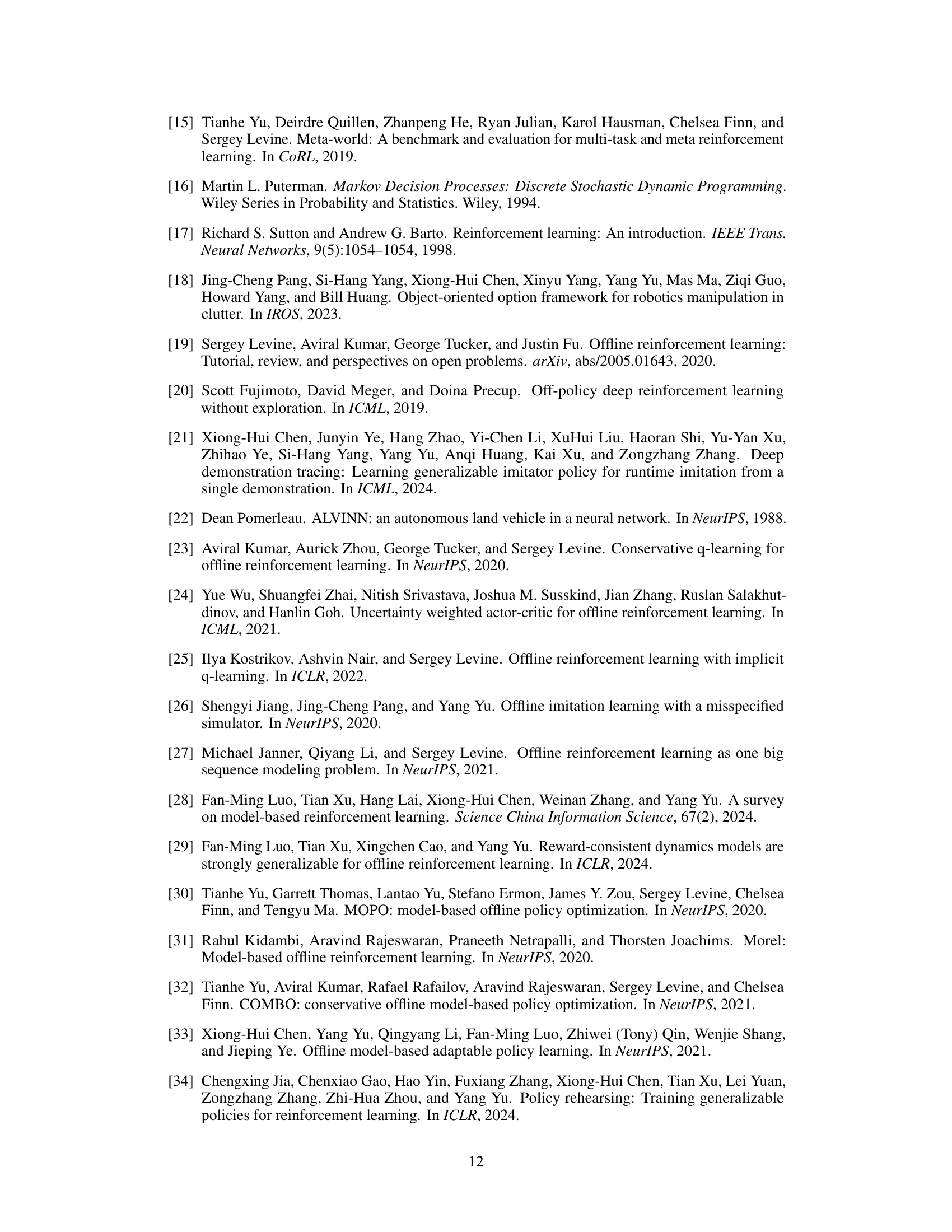

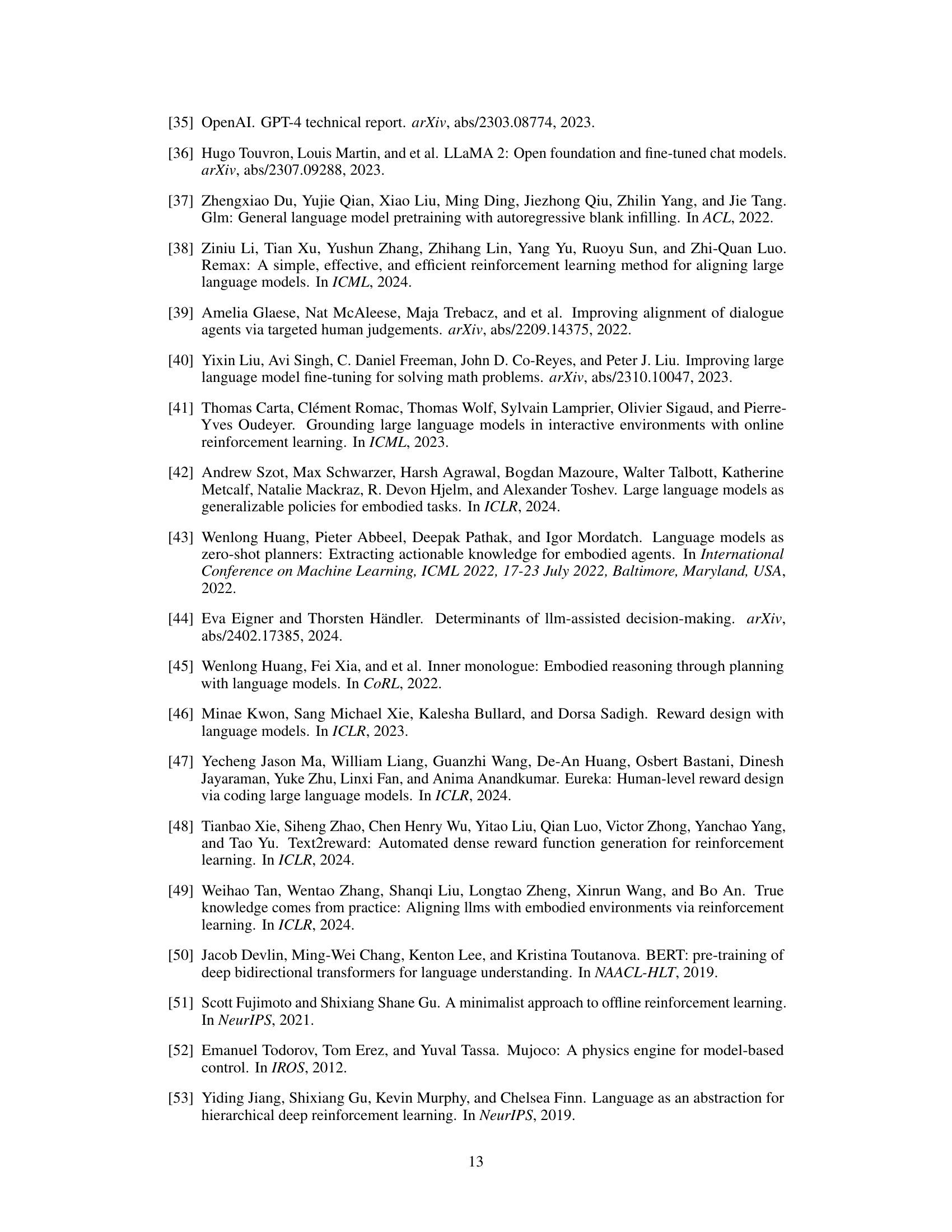

This table provides a detailed breakdown of the various types of goals used in the experiments, categorized by their level of novelty (tasks in the dataset, rephrasing goals, unseen easy, and unseen hard). For each category, it describes the goal type for both the CLEVR-Robot and Meta-world environments. The descriptions highlight the differences in complexity and the types of manipulation tasks involved, making it easier to understand the experimental setup and the challenges faced by the AI agent in each scenario.

In-depth insights#

LLM Offline RL#

The combination of Large Language Models (LLMs) and offline reinforcement learning (RL) presents a powerful paradigm shift in AI agent development. LLMs offer a rich source of knowledge and reasoning capabilities, which can be leveraged to generate high-quality training data for RL agents, even in the absence of extensive real-world interaction. Offline RL, in turn, allows for efficient learning from this pre-generated data, avoiding the often costly and time-consuming process of trial-and-error in dynamic environments. This approach is particularly beneficial for complex tasks requiring nuanced decision-making, as the LLM can provide insights beyond the limitations of simple reward functions. However, bridging the semantic gap between the symbolic reasoning of LLMs and the numerical representations of RL environments remains a key challenge. Effective strategies for translating LLM outputs (like plans or trajectories) into actionable commands for the agent are crucial for successful implementation. Furthermore, robustness to noise and inaccuracies in the LLM’s knowledge is a critical consideration. The effectiveness of this approach depends heavily on the quality of the LLM and the careful design of the data generation process. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated methods for knowledge transfer and addressing the limitations of relying on solely pre-generated data, potentially integrating online RL components for continuous adaptation and refinement.

Bidirectional Tuning#

Bidirectional tuning, in the context of large language models (LLMs) interacting with environments, represents a crucial technique for bridging the semantic gap between symbolic reasoning and numerical data. It suggests a method of training LLMs to effectively translate between textual instructions and numerical representations of states and actions within a dynamic environment. This bidirectional translation capability is vital as LLMs naturally operate in symbolic space whereas robotic environments commonly use numerical data. The process involves a supervised fine-tuning phase. This phase uses paired data—textual descriptions and the corresponding numerical representations—to train the LLM to generate accurate representations of environment data from text-based prompts and also generate text-based summaries of numerical environment data. The efficacy of this technique rests on the availability of a sufficiently large and representative paired dataset to avoid biases. Successful bidirectional tuning enhances the LLM’s understanding of the environment, improving both its planning and control capabilities. The bidirectional aspect is important because it enables the LLM to not only interpret instructions but also translate complex environment data into meaningful textual descriptions. This is crucial for tasks where an agent must both understand goals expressed as text and interact with a numerical environment. The quality of the bidirectional mappings directly correlates with the success of any LLM-guided agent to operate in the targeted environment.

Novel Robotic Tasks#

Developing novel robotic tasks is crucial for evaluating the generalization capabilities of reinforcement learning (RL) agents. These tasks should push beyond the limitations of existing datasets, forcing the agent to learn new behaviors and strategies rather than simply memorizing pre-existing solutions. The design of these tasks should be systematic, perhaps categorized by difficulty and the type of novel skills required (e.g., manipulation of previously unseen objects, adaptation to unexpected environmental changes, or combining skills in creative ways). Quantitative metrics are needed to evaluate performance on novel tasks, capturing not only success rates but also the efficiency and robustness of the solutions. A comprehensive evaluation would involve comparing performance on novel tasks to that on familiar tasks, highlighting areas of strength and weakness in the agent’s generalization capabilities. Ultimately, the creation and analysis of novel robotic tasks will significantly advance the field of RL, demonstrating the true potential of trained agents to operate effectively in dynamic and unpredictable environments.

KALM Framework#

The KALM framework presents a novel approach to training knowledgeable agents by leveraging large language models (LLMs). Its core innovation lies in bridging the semantic gap between LLM outputs (text) and the numerical data typical of RL environments. KALM achieves this by using the LLM to generate imaginary rollouts, sequences of states and actions, that an agent can then learn from using offline RL methods. This approach bypasses the limitations of traditional RL, which relies heavily on real-world interaction data, and allows for training in more diverse and complex scenarios. A key component is the bidirectional translation fine-tuning of the LLM, enabling it to translate between textual goals and numerical rollouts, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the environment. This framework demonstrates improved performance over baseline offline RL methods, particularly on novel tasks where the agent must exhibit novel behaviors, suggesting the efficacy of incorporating LLM-generated data into offline RL.

Future of KALM#

The future of KALM hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving the LLM’s grounding is crucial; using separate LLMs for state and action prediction could enhance accuracy. Incorporating multimodal data (images, sensor readings) beyond textual and numerical data would significantly broaden KALM’s applicability to real-world scenarios. Exploring alternative offline RL algorithms and potentially incorporating online RL elements for continual learning would improve policy robustness. Addressing the challenge of unseen (hard) tasks warrants further investigation, potentially by augmenting the LLM with more sophisticated reasoning capabilities or by incorporating hierarchical planning. Finally, exploring applications beyond robotics, such as virtual environments or game AI, and thoroughly evaluating KALM’s generalizability and scalability across diverse tasks are essential steps for its future development. Robustness and safety considerations should always be at the forefront of future development, ensuring that KALM’s outputs are reliable and pose minimal risk in real-world implementations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the KALM method. Panel (A) shows the three key steps involved in training the agent: LLM grounding (fine-tuning the LLM with environmental data), rollout generation (using the LLM to generate imaginary rollouts for new tasks), and offline RL training. Panel (B) shows the adapted network architecture of the LLM, which has been modified to process both textual and environmental data.

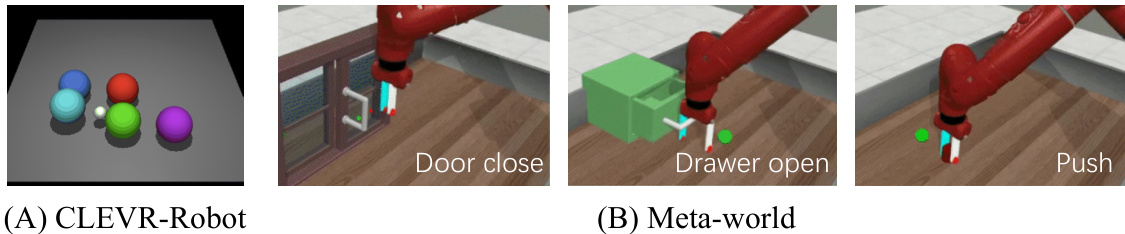

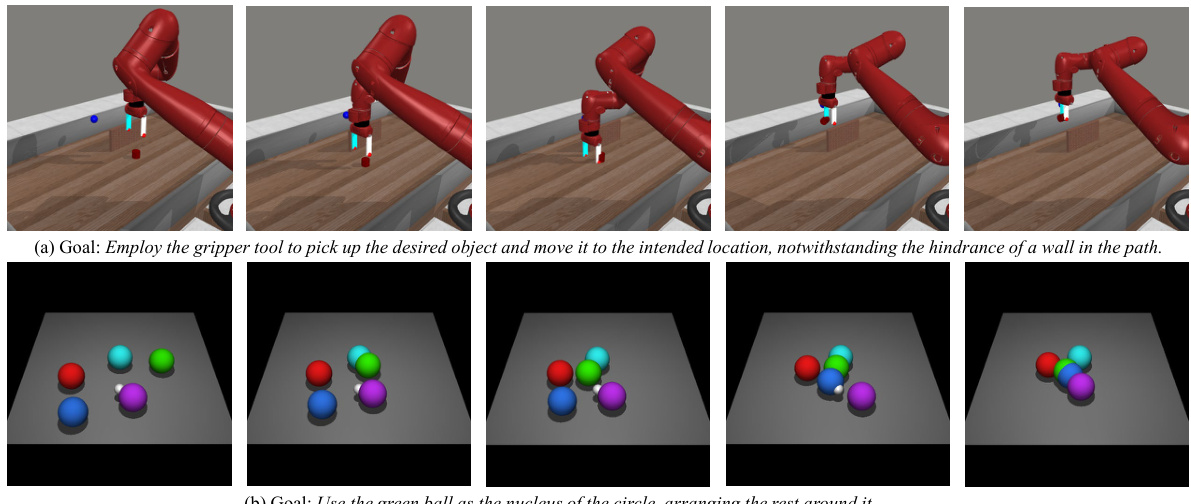

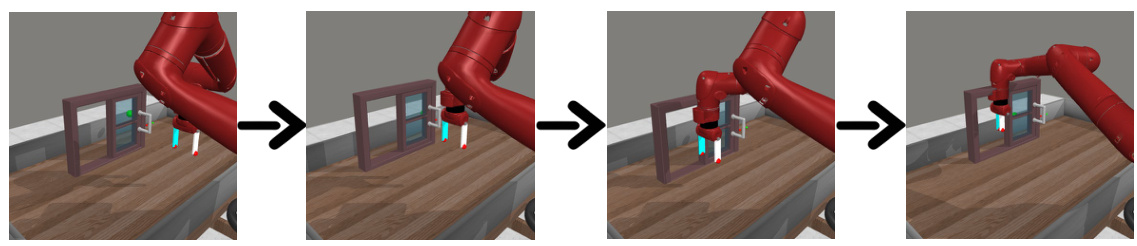

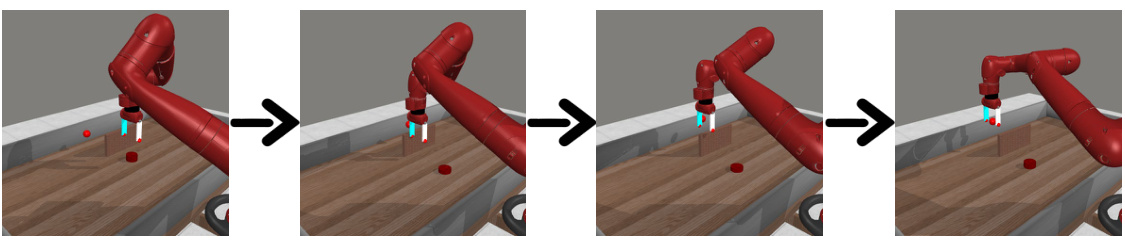

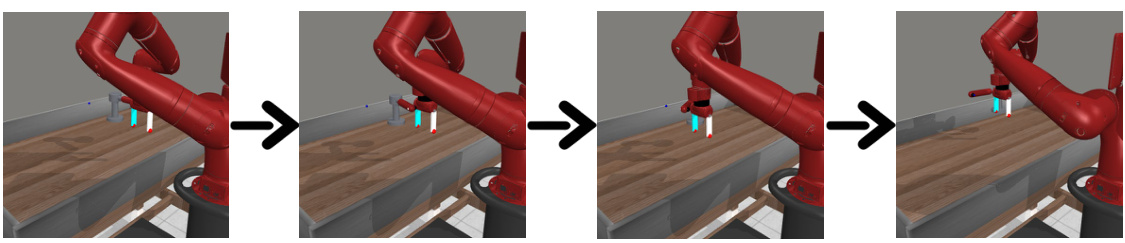

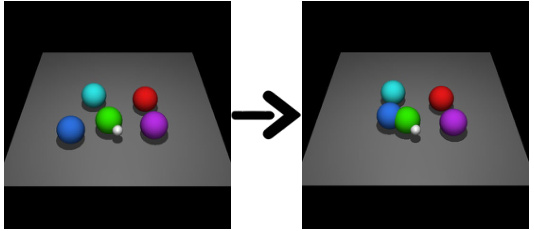

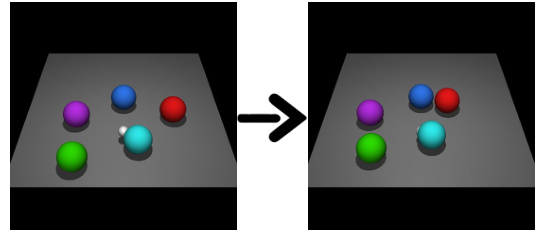

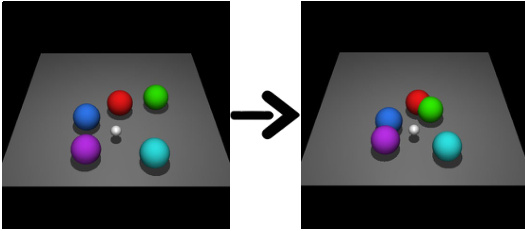

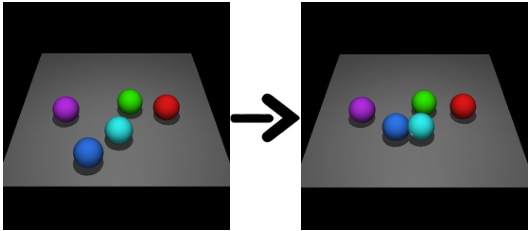

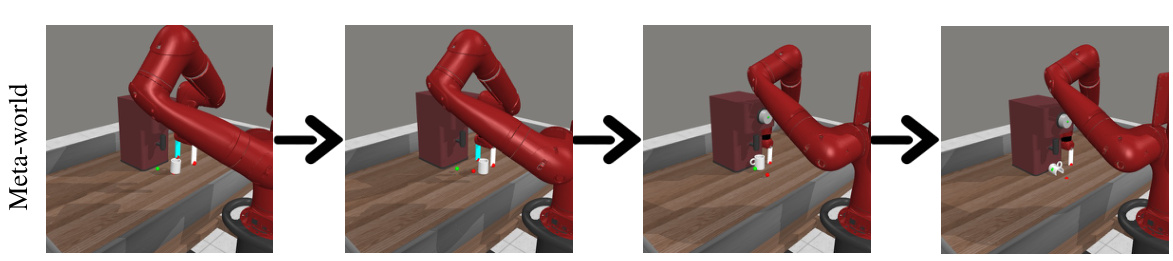

This figure visualizes the two robotic manipulation environments used in the paper’s experiments: CLEVR-Robot and Meta-world. CLEVR-Robot shows a simple setup where a robotic agent manipulates five colored balls to achieve a specific arrangement. Meta-world depicts a more complex scenario with a Sawyer robot arm interacting with various objects, like doors, drawers, and other manipulanda. These environments showcase the range of tasks used to evaluate the KALM model’s performance.

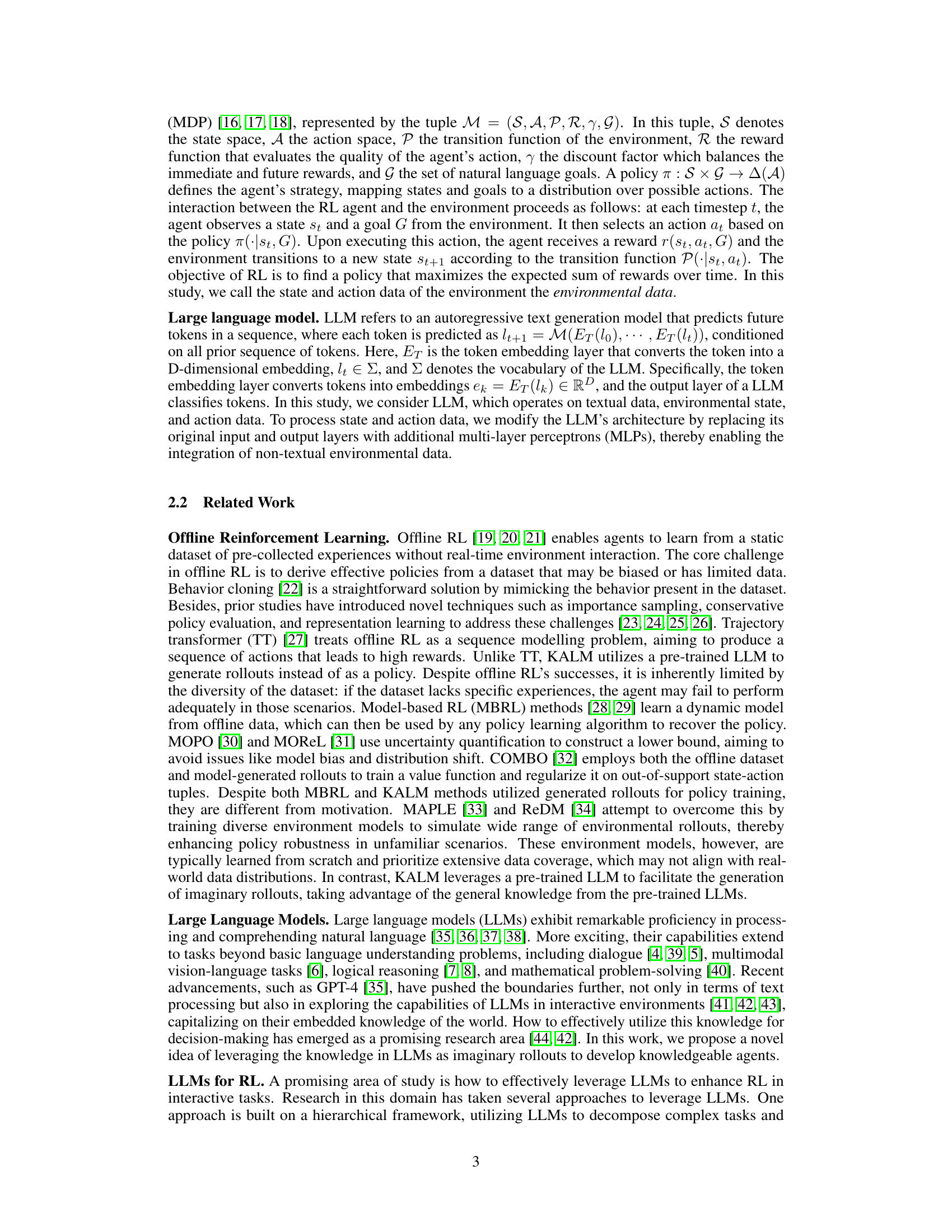

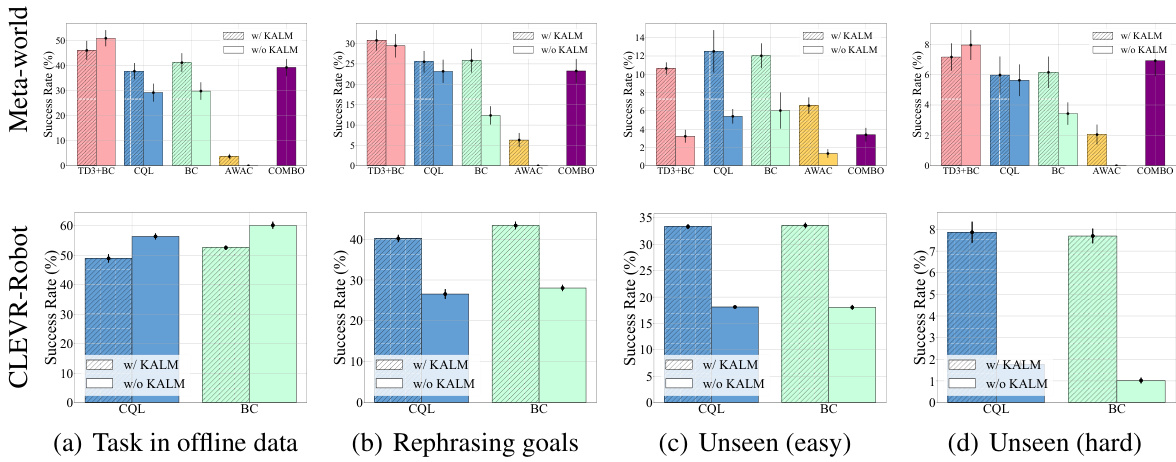

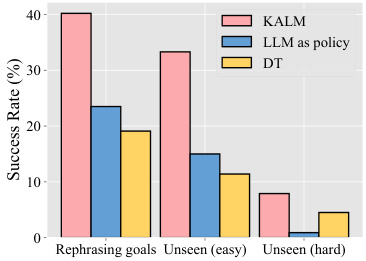

This figure compares the success rates of different offline reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms on four types of tasks with varying levels of difficulty: tasks from offline data, rephrasing goals, unseen (easy) goals, and unseen (hard) goals. Each bar represents the average success rate of a particular RL algorithm, with and without the KALM method. Error bars show the standard deviation, indicating the reliability of the results. The results illustrate that KALM significantly improves the success rate, especially on more challenging, unseen tasks.

This figure compares the performance of KALM with two baseline methods: using LLM directly as a policy and Decision Transformer (DT). The x-axis shows the type of task: rephrasing goals, unseen (easy), and unseen (hard). The y-axis represents the success rate. KALM significantly outperforms both baselines, especially on more complex, unseen tasks.

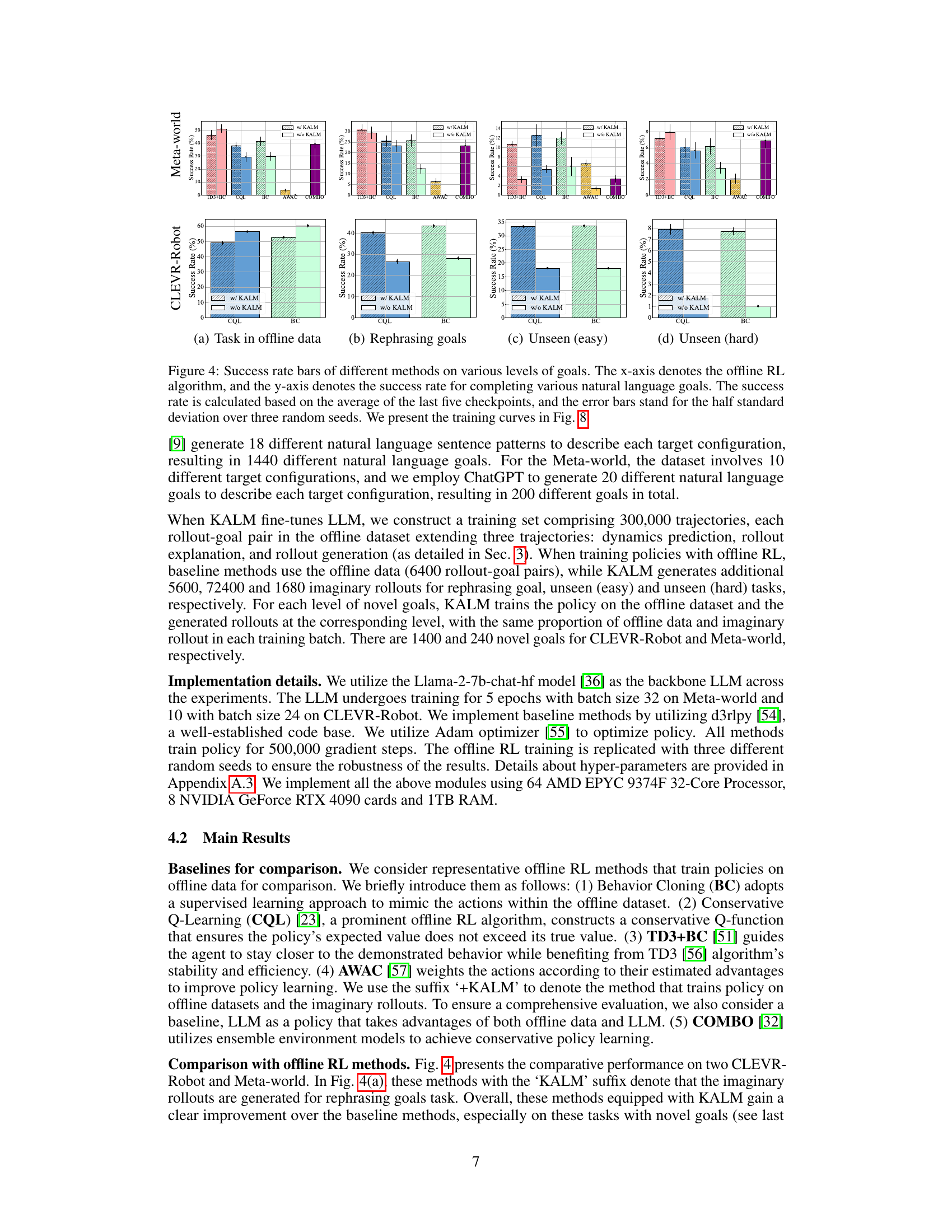

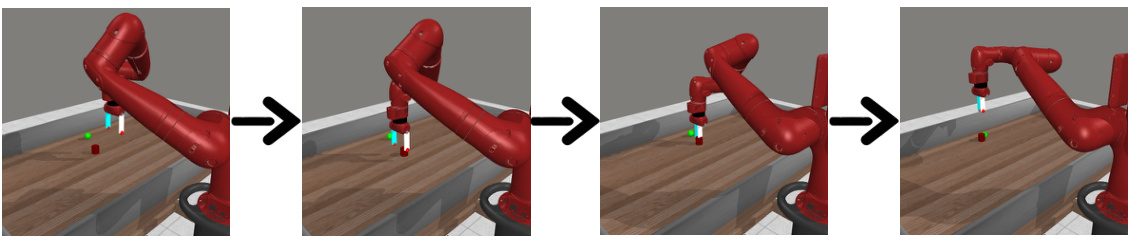

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) in the KALM (Knowledgeable Agent from Language Model Rollouts) method. The top row shows a robotic arm successfully navigating an obstacle (a wall) to reach a target object. The bottom row shows a successful arrangement of colored balls in a circle, using a specified ball as the center. These examples demonstrate the LLM’s capacity to generate realistic and task-appropriate sequences of actions.

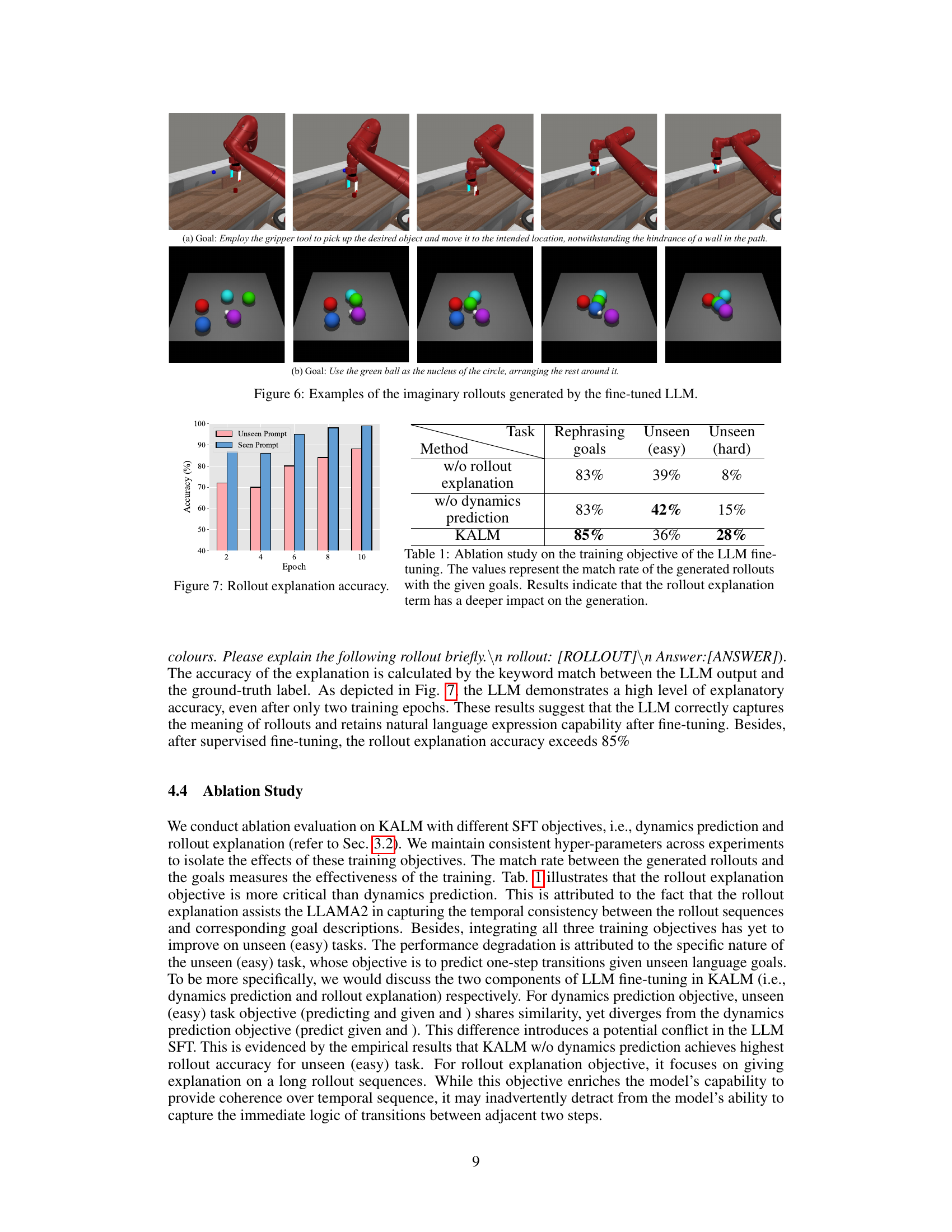

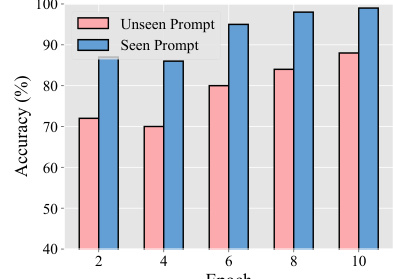

The figure shows the accuracy of the LLM in explaining rollouts, comparing performance on seen and unseen prompts. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the accuracy in percentage. The results indicate the model’s ability to explain rollouts improves with training, though it is generally better at explaining seen rollouts.

This figure shows the accuracy of the LLM in explaining rollouts. The accuracy is measured by comparing keywords in the LLM’s explanation to the ground truth. The results demonstrate high accuracy (over 85%) for both seen and unseen prompts, indicating that the LLM effectively captures the meaning of rollouts. The graph shows accuracy over training epochs, demonstrating improvement over time.

This figure shows the training curves of different offline reinforcement learning methods on four types of goals: tasks in offline data, rephrasing goals, unseen (easy) goals, and unseen (hard) goals. The x-axis represents the training epochs, and the y-axis shows the success rate (percentage) achieved by each method on each goal type. Error bars representing half standard deviation are included for each data point, indicating the variability in performance across multiple random runs. The figure visually compares the performance of various offline RL algorithms with and without the incorporation of the KALM method, highlighting the improvements gained by using the proposed approach. It helps in understanding how KALM affects the learning progress and the ability of the agent to generalize to novel tasks.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts for rephrasing goal tasks, in both Meta-world and CLEVR-Robot environments. The top row depicts a successful rollout in Meta-world where the robot arm navigates around a wall to reach a target object. The bottom row shows a successful rollout in CLEVR-Robot where the red ball is moved to the left of the blue ball. A failure case is also presented for each environment, highlighting situations where the LLM’s rollout generation struggles with complex scenarios or ambiguous instructions.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts for rephrasing goal tasks in both Meta-world and CLEVR-Robot environments. The top row illustrates a successful rollout in Meta-world where a robot arm opens a door, and the bottom row shows a successful rollout in CLEVR-Robot where the agent moves balls to the specified positions. A failure case is also shown for each environment, demonstrating situations where the LLM’s generated rollout does not successfully complete the task.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts for rephrasing goal tasks, comparing successful and unsuccessful examples in both Meta-world and CLEVR-Robot environments. The Meta-world examples illustrate the robot’s manipulation of objects, while the CLEVR-Robot examples demonstrate the manipulation of colored balls. The figure showcases the LLM’s ability to generate rollouts that align with the given goals, but also highlights cases where the LLM struggles to generate successful plans, particularly in complex scenarios.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts by the LLM for rephrasing goal tasks. The top row shows successful rollouts for a Meta-world task (moving an object to a specific location), demonstrating the LLM’s ability to generate a successful sequence of actions. The bottom row shows successful and failed rollouts for CLEVR-Robot tasks (repositioning colored balls). The failure example highlights that while the LLM can understand the goal, it may fail to generate a correct rollout if the initial state is not ideal.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts for rephrasing goal tasks in both Meta-world and CLEVR-Robot environments. The top row displays successful rollouts where the robot arm successfully navigates to its goal despite obstacles. The bottom row shows unsuccessful attempts, highlighting the limitations of the LLM in complex scenarios, such as navigating through obstacles or accurately understanding a complex instruction.

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned large language model (LLM) for the CLEVR-Robot environment. The first example demonstrates the LLM’s ability to generate a rollout that successfully moves a specific object to the desired location, even with an obstacle (wall) in the path. This showcases that the LLM understands the environment’s dynamics and can plan accordingly. The second example demonstrates how the LLM can generate a rollout to arrange the balls in a circle around the green ball, even though this specific task was not present in the training data. This highlights the LLM’s ability to generalize and perform tasks that require higher-level understanding and planning.

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) in the KALM method. The first example (a) shows a robotic arm navigating around a wall to pick up an object; the second example (b) shows several colored balls being arranged in a circle around a central green ball. These examples illustrate the LLM’s ability to generate plausible and goal-oriented sequences of actions and states, even for tasks or situations not explicitly present in its training data.

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) in the KALM method. The top example depicts a robotic arm successfully navigating a wall to reach its goal. The bottom example shows the LLM’s ability to generate rollouts for a complex task of arranging multiple balls around a central green ball according to a specific pattern. These examples highlight the LLM’s ability to generate meaningful and physically realistic rollouts.

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) in the KALM method. The first example demonstrates a successful rollout in the Meta-world environment where the robot successfully navigates around a wall to reach a target location. The second example shows a successful rollout in the CLEVR-Robot environment where the robot successfully arranges multiple balls according to a complex goal description. These examples illustrate the LLM’s ability to generate realistic and diverse rollouts for novel tasks.

This figure shows additional examples of generated rollouts for rephrasing goal tasks in both Meta-world and CLEVR-Robot environments. In Meta-world, the successful example demonstrates the robot arm moving to grasp an object, navigating around an obstacle (a wall). The failed example shows an issue where the robot doesn’t seem to correctly interpret the goal of opening a closed window. In CLEVR-Robot, the successful example illustrates a robot manipulating colored balls according to a given goal (moving one ball in front of another). The failed example shows a case where the robot’s actions don’t completely align with the desired outcome.

This figure shows two examples of imaginary rollouts generated by the fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) for unseen (hard) tasks in the CLEVR-Robot and Meta-world environments. The top row displays a successful rollout in CLEVR-Robot where the LLM arranges colored balls around a green ball to form a circle, even though this task was not in the training data. The bottom row shows a successful rollout in Meta-world where the robotic arm successfully interacts with objects and navigates around obstacles to accomplish a goal that was not in the training data.

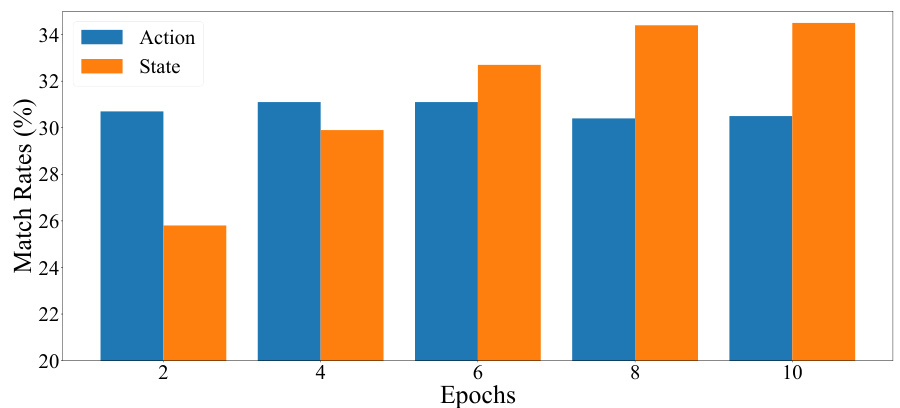

This figure shows the accuracy of the LLM in generating states and actions for unseen (easy) tasks during the training process. The x-axis represents the training epochs, and the y-axis represents the match rate (percentage) of generated states and actions against the labeled goals. The results indicate a relatively constant action generation accuracy, suggesting consistent ability to generate actions. However, the state generation accuracy improves over epochs, showing learning and better alignment with the goals.

More on tables

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the KALM method and baseline methods for comparison. The hyperparameters cover discount factor, batch size, learning rate (LR), imitation weight (for BC), conservative weight (for CQL), alpha (for TD3+BC), and lambda (for AWAC). The feature extractor network architecture is also specified. Consistent hyperparameters are used for fair comparison across different offline RL algorithms.

This table shows the percentage of unrealistic transitions in the generated imaginary rollouts for the CLEVR-Robot environment. It categorizes these unrealistic transitions into two types: ‘Out of workbench’ and ‘Exceed dynamics limits’. ‘Out of workbench’ refers to instances where the object’s position in the rollout is outside the bounds of the workbench. ‘Exceed dynamics limits’ refers to instances where the changes in object position between consecutive steps in the rollout violate the physical constraints of the environment.

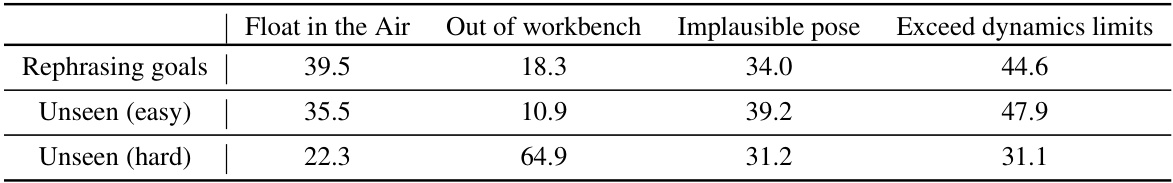

This table shows the percentage of unrealistic transitions in the imaginary rollouts generated by the LLM for different types of tasks in the Meta-world environment. The unrealistic transitions are categorized into four types: objects floating in the air, objects outside the workbench area, implausible object poses (e.g., physically impossible joint angles), and exceeding the dynamic limits between consecutive steps. These statistics provide insights into the quality and plausibility of the LLM-generated rollouts for different task difficulty levels. Higher percentages indicate a lower quality of generated rollouts.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the KALM method and the baseline methods. It includes values for discount factor, batch size, learning rate (LR), and other relevant parameters for each algorithm (BC, CQL, TD3+BC, AWAC). The table shows the settings used for both the offline RL training and the LLM fine-tuning process, highlighting the consistency in hyperparameter settings across different algorithms.

Full paper#