↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training large language models (LLMs) is computationally expensive, with memory usage being a significant hurdle. Existing memory-efficient optimizers often lack strong theoretical guarantees or compromise on accuracy. This paper presents MICROADAM, a new adaptive optimization algorithm designed to address these limitations.

MICROADAM achieves significant memory savings by compressing gradient information before feeding it into the optimizer. A novel error feedback mechanism is used to control the compression error and ensure convergence. The researchers provide a theoretical analysis demonstrating competitive convergence guarantees and showcase MICROADAM’s practical efficiency and accuracy on BERT and LLaMA models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models due to its introduction of MICROADAM, a novel optimizer that drastically reduces memory usage without sacrificing accuracy or convergence guarantees. This addresses a major bottleneck in training LLMs and opens exciting avenues for research into more memory-efficient deep learning optimization methods.

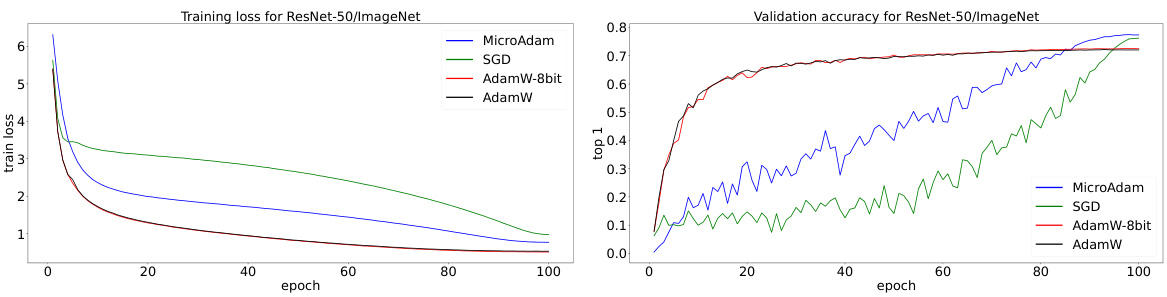

Visual Insights#

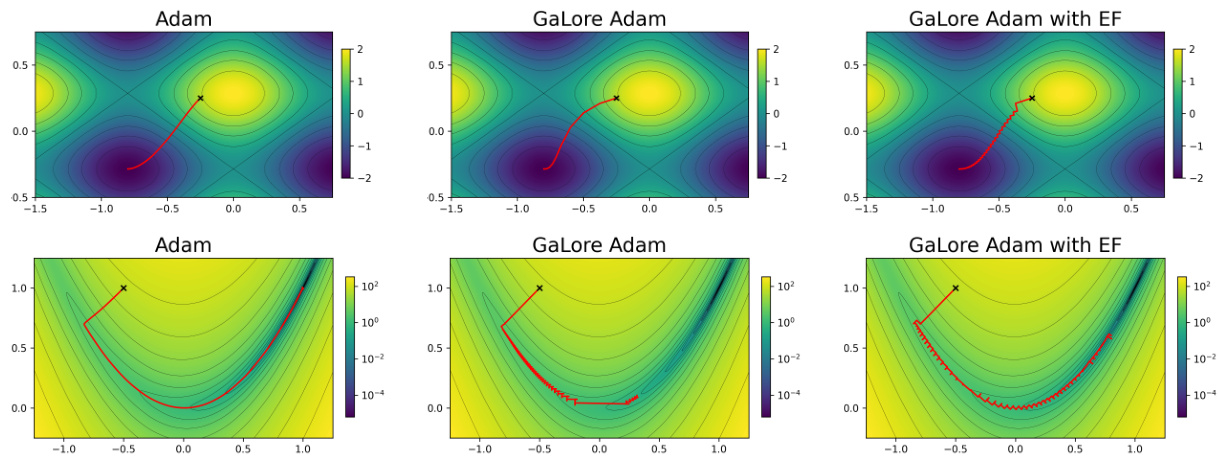

This figure compares the optimization trajectories of three different Adam optimizer variants on the Rosenbrock function. The standard Adam optimizer shows smooth convergence. TopK-Adam, which uses a sparse gradient, exhibits a jagged and less effective convergence path. Finally, TopK-Adam with error feedback (EF) demonstrates convergence that is nearly identical to the standard Adam, highlighting the effectiveness of the EF mechanism in mitigating the adverse effects of gradient sparsity.

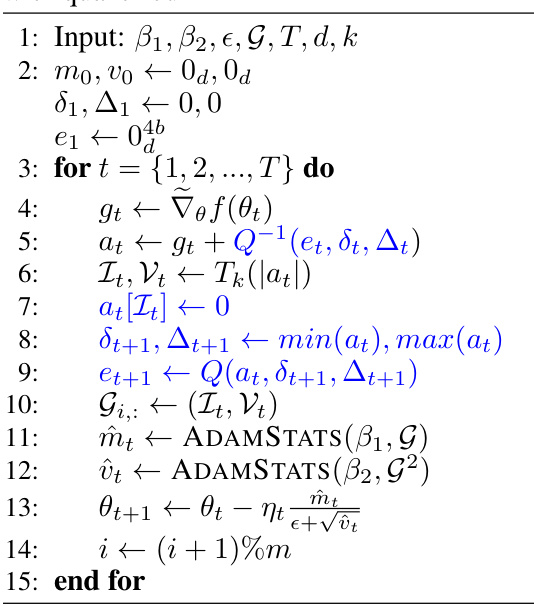

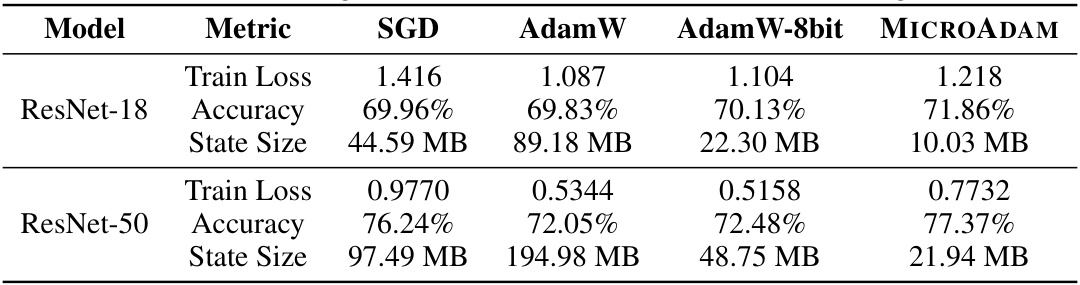

This table compares the performance of MICROADAM against Adam, Adam-8b, CAME, and GaLore on the GLUE/MNLI benchmark. Metrics include training loss, accuracy, and memory usage (in GB) for three different model sizes: BERT-BASE (110M parameters), BERT-LARGE (335M parameters), and OPT-1.3B (1.3B parameters). The asterisk (*) indicates runs where the optimizer failed to converge on one or more random seeds; the table reports the results from the best-performing seed for those cases.

In-depth insights#

MicroAdam: Memory#

MicroAdam is presented as a memory-efficient optimization algorithm, particularly beneficial for training large language models. The core idea revolves around compressing gradient information before it’s processed by the optimizer. This compression significantly reduces the memory footprint, a crucial aspect for handling the massive parameter spaces of LLMs. The method employs an error feedback mechanism to control the compression error, ensuring that the algorithm maintains theoretical convergence guarantees. Crucially, the error correction itself is compressed, further enhancing memory savings. Experiments demonstrate MicroAdam’s effectiveness in achieving competitive performance compared to traditional Adam and other memory-optimized methods on both million and billion-scale models, all while showcasing a drastically reduced memory usage. The algorithm proves successful in fine-tuning LLMs, highlighting its suitability for real-world applications. This contrasts with existing memory-efficient optimizers that often lack theoretical convergence guarantees or compromise accuracy for memory reduction. MicroAdam’s novel combination of compression, error feedback, and theoretical guarantees sets it apart as a significant advancement in memory-efficient optimization for large-scale models.

Adam Compression#

Adam, a popular adaptive optimization algorithm, suffers from high memory overhead due to storing multiple parameters per variable. Adam compression techniques aim to mitigate this by reducing the size of gradient information and/or optimizer states. These techniques often involve compression methods such as sparsification (e.g., keeping only the top-k largest gradient values), quantization (e.g., representing gradients with fewer bits), or low-rank approximations. While this can lead to significant memory savings, it’s crucial to balance compression with maintaining accuracy and convergence guarantees. Lossy compression introduces errors that, if not carefully managed (e.g., via error feedback mechanisms), can hinder optimization. Theoretical analysis is vital to establish the convergence properties of the compressed Adam variant. Effective Adam compression strategies aim for good practical performance with minimal impact on training speed.

Convergence Rates#

The theoretical analysis of convergence rates is a crucial aspect of the research paper. The authors likely present convergence rates for different scenarios, such as general smooth non-convex functions and functions satisfying the Polyak-Lojasiewicz (PL) condition. For non-convex settings, the rates likely demonstrate a trade-off between the compression level and the convergence speed. The PL condition allows for stronger theoretical guarantees and potentially faster rates, showcasing the impact of problem structure on optimization. The analysis likely involves techniques from optimization theory and careful treatment of error introduced by gradient compression. Showing that MicroAdam maintains convergence rates competitive to or even matching existing optimizers such as AMSGrad while significantly reducing memory overhead is a key result. The theoretical analysis is critical in establishing MicroAdam’s efficiency and accuracy relative to other methods.

LLM Fine-tuning#

LLM fine-tuning, a crucial aspect of large language model adaptation, focuses on enhancing pre-trained models for specific downstream tasks. This process leverages the existing knowledge embedded within the model and refines it to improve performance on a targeted application. Successful fine-tuning relies heavily on careful selection of training data, hyperparameter optimization, and evaluation metrics. Data quality and quantity are paramount; insufficient or noisy data can lead to poor performance or overfitting. The choice of fine-tuning methods, such as full fine-tuning or parameter-efficient techniques (e.g., adapter methods, prompt tuning), significantly impacts both resource consumption and performance. Parameter-efficient methods offer a compelling alternative when computational resources are limited, allowing for more efficient adaptation without retraining the entire model. Careful monitoring of performance on validation sets is crucial to avoid overfitting and to identify the optimal point at which to stop training. Finally, robust evaluation metrics that measure the model’s efficacy in the target context are necessary to assess the effectiveness of the fine-tuning process. The interplay between these factors – data, methods, and evaluation – determines the ultimate success of LLM fine-tuning.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending MICROADAM’s compression techniques to other adaptive optimizers beyond Adam, potentially leading to broader applicability and memory efficiency gains. Investigating the impact of different compression strategies (e.g., varying sparsity levels, quantization methods) on convergence and accuracy across diverse model architectures and datasets is crucial. Furthermore, a deeper theoretical understanding of MICROADAM’s implicit regularization properties and their impact on generalization would be valuable. This could involve a comparative analysis against other memory-efficient optimizers that lack provable convergence. Finally, practical scalability studies on even larger models (beyond billions of parameters) are necessary, including exploring distributed training scenarios and the effect of communication compression techniques in conjunction with MICROADAM’s gradient compression.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the optimization trajectories of three different Adam optimizers on the Rosenbrock function: the standard Adam, Adam with TopK compression (TopK-Adam), and Adam with TopK compression and error feedback (TopK-Adam with EF). The Rosenbrock function is a well-known test function in optimization known for its non-convexity and challenging landscape. The figure visually demonstrates that TopK compression significantly degrades the optimization trajectory, leading to a highly oscillatory and inefficient path toward the minimum. However, by incorporating error feedback, the TopK-Adam with EF optimizer recovers a smooth and efficient trajectory comparable to the standard Adam. This illustrates the effectiveness of error feedback in mitigating the detrimental effect of TopK gradient compression.

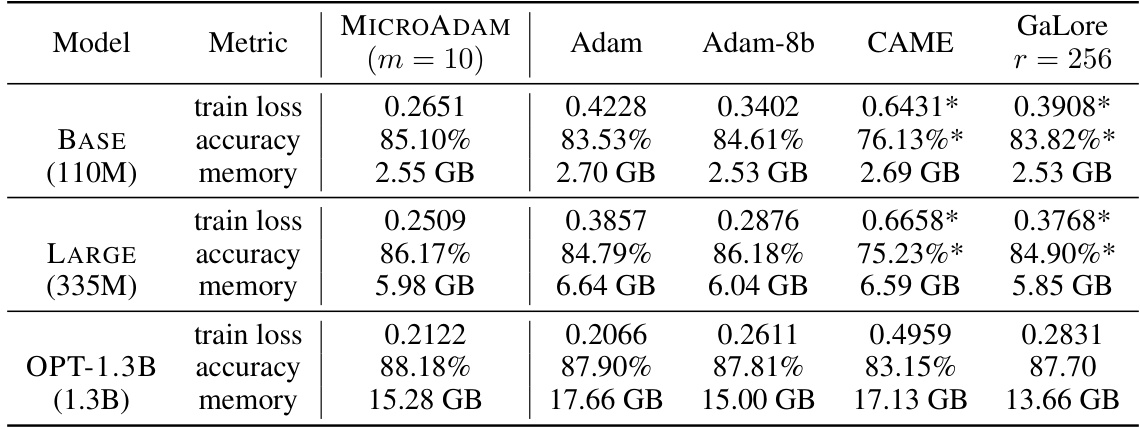

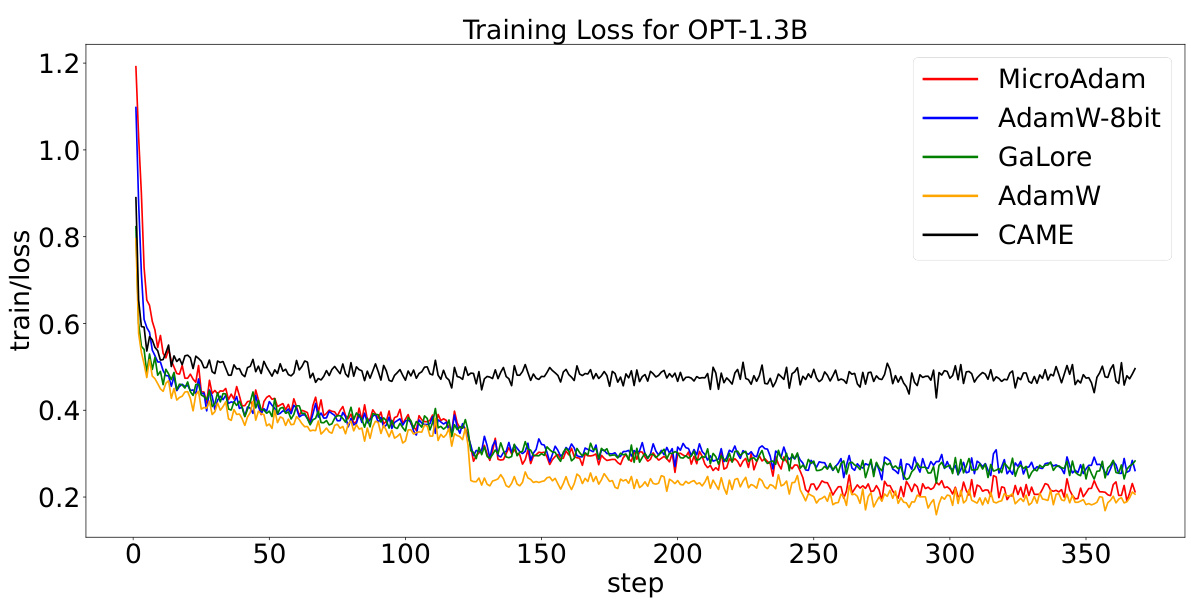

This figure compares the training loss curves of six different optimizers (MicroAdam, AdamW-8bit, GaLore, AdamW, CAME) during the fine-tuning of a BERT-Base model on the GLUE/MNLI dataset. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis shows the training loss. The plot visually demonstrates the convergence speed and stability of each optimizer.

This figure shows the training loss curves for different optimizers (MicroAdam, AdamW-8bit, GaLore, AdamW, and CAME) during the fine-tuning of the BERT-Large model on the GLUE/MNLI dataset. It visually compares the convergence speed and stability of each optimizer. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis represents the training loss.

This figure compares the optimization trajectories of three different Adam variants on the Rosenbrock function, a well-known non-convex function. The variants are: 1. Standard Adam: The original Adam optimizer. 2. TopK-Adam: Adam with a TopK sparsification applied to the gradients (only the top k largest gradient components are used). 3. TopK-Adam with EF: TopK-Adam augmented with an error feedback (EF) mechanism to correct for the information lost during the TopK compression. The plot visually demonstrates that TopK-Adam without EF produces a poor, jagged convergence trajectory. However, adding EF to the TopK-Adam method allows for a smoother, near-perfect recovery of the original Adam’s convergence behavior.

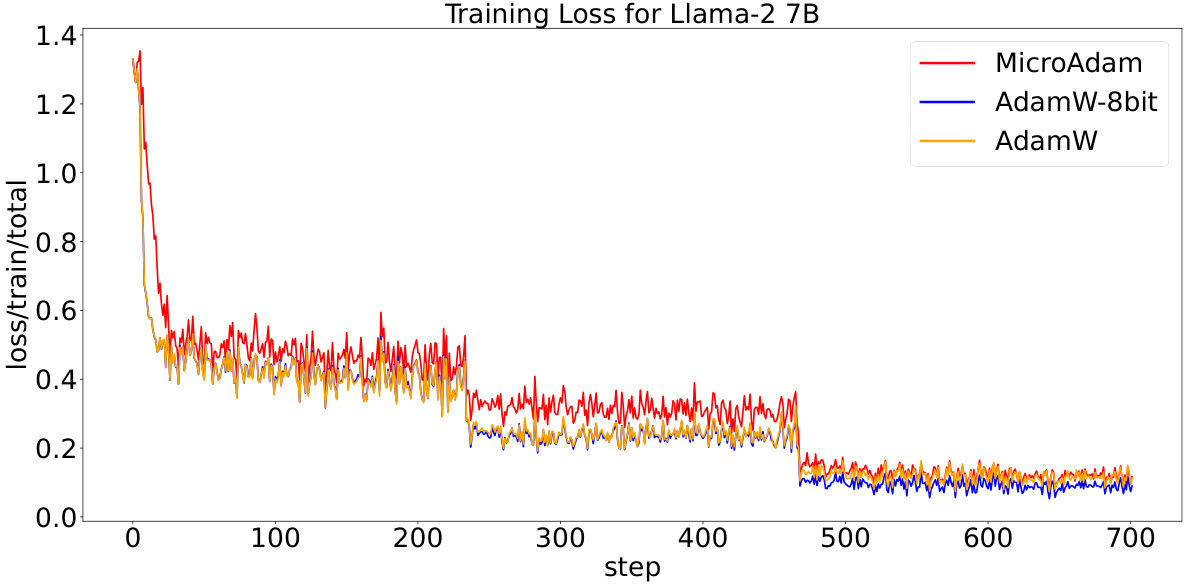

This figure shows the training loss curves for three different optimizers: MicroAdam, AdamW-8bit, and AdamW, when training the Llama-2 7B language model on the GSM-8k dataset. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis represents the training loss. The plot allows for a visual comparison of the training performance and convergence speed of each optimizer. MicroAdam shows comparable performance with AdamW, and outperforms AdamW-8bit.

This figure shows the optimization trajectories for three different optimization methods applied to the Rosenbrock function. The Rosenbrock function is a well-known test function for optimization algorithms known for its difficulty due to its non-convexity. The three methods are: (1) Adam, the original adaptive optimization algorithm; (2) TopK-Adam, a version of Adam that compresses the gradient information by considering only the top K largest elements; and (3) TopK-Adam with Error Feedback (EF), which adds a correction term to the TopK-Adam algorithm to account for the loss of information due to the compression. The figure demonstrates that while compressing the gradient information using TopK reduces the memory footprint, it can significantly hamper convergence. However, the addition of EF successfully recovers the convergence of the original Adam optimizer, proving its ability to correct the errors introduced by the compression.

This figure compares the optimization trajectories of three different Adam optimizer variants on the Rosenbrock function. The first one is the original Adam optimizer, while the second one is an Adam optimizer with TopK sparsification that only considers the largest coordinate of the gradient. The last one adds error feedback to the TopK Adam optimizer. The figure shows that the TopK Adam alone fails to converge and has a jagged trajectory due to its sparse gradient. However, adding error feedback results in a recovered convergence trajectory that is similar to the original Adam optimizer.

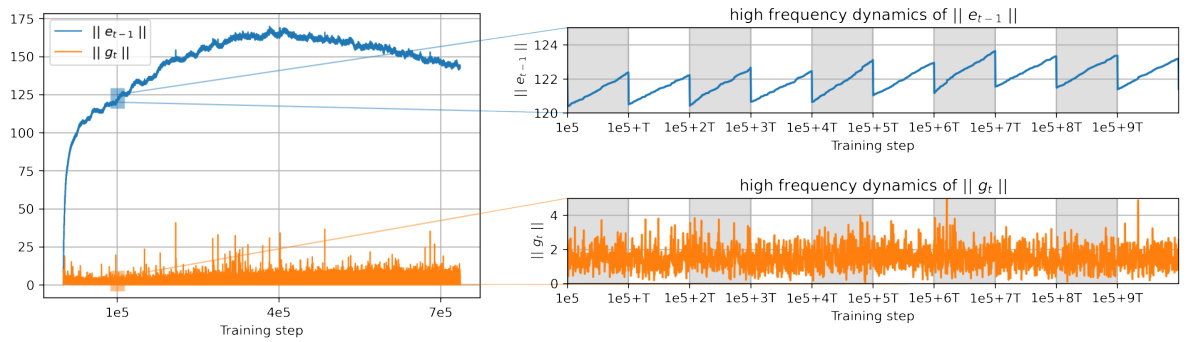

This figure shows the dynamics of the error norm compared to the gradient norm during fine-tuning of a ROBERTa-base model on the GLUE/MNLI dataset using a surrogate GaLore optimizer with error feedback. It highlights the linear growth of error between subspace updates (indicated by grey shaded regions) and how the error norm significantly exceeds the gradient norm. The hyperparameters used are detailed in the caption, aligning with those from the Zhao et al. (2024) paper.

This figure shows the optimization trajectories of three different optimizers on the Rosenbrock function: Adam, TopK-Adam (Adam with Top-K compression), and TopK-Adam with EF (error feedback). The Rosenbrock function is a well-known non-convex optimization problem. The figure demonstrates that TopK compression alone leads to a less efficient optimization trajectory (jagged), but adding error feedback significantly improves performance and recovers convergence similar to the original Adam optimizer. This illustrates the importance of the error feedback mechanism in maintaining optimization efficiency in MICROADAM while using compressed gradients.

More on tables

This table presents the results of fine-tuning (FFT) experiments using Llama-2 7B and 13B models on the GSM-8k dataset. It compares the performance of Adam, Adam-8b, and MICROADAM (with two different window sizes, m = 10 and m = 20) in terms of accuracy, memory usage (both optimizer state and total), and training runtime. The table highlights the memory efficiency of MICROADAM compared to the other optimizers while demonstrating that it maintains competitive accuracy.

This table compares the performance of different optimizers (AdamW, Adam-8b, and MICROADAM) on the Open-Platypus instruction-following dataset. The metrics include average accuracy across multiple tasks and per-task accuracy (ARC-c, HellaSwag, MMLU, Winogrande) using different few-shot settings. The table also shows the memory usage for each optimizer. The results demonstrate that MICROADAM achieves comparable or better accuracy than the other optimizers while using significantly less memory.

This table shows the results of fine-tuning experiments on the GLUE/MNLI dataset using various optimizers, including MICROADAM, Adam, Adam-8bit, CAME, and GaLore. For each model (BERT-BASE, BERT-LARGE, OPT-1.3B), the table presents the train loss, accuracy, and total memory usage. The asterisk indicates runs where convergence wasn’t achieved for all seeds, and the reported results are from the best performing run.

Full paper#