↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications of machine learning involve human experts labeling data, but these experts may not always label every instance given to them. This paper introduces a new active learning problem called ALIR (Active Learning with Instance Rejection), which accounts for this reality. Existing active learning methods assume that humans will always label all selected instances. This is not always the case in high-stakes decision-making, where cost and human factors may influence labeling decisions.

To address the ALIR problem, the authors propose new active learning algorithms under the framework of deep Bayesian active learning for selective labeling (SEL-BALD). These algorithms model both the machine learning process and the human decision-making process to select the most informative instances to label while respecting human discretion. The proposed algorithms were thoroughly evaluated using both synthetic and real-world datasets, demonstrating significant improvements in sample efficiency and model performance compared to traditional active learning methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on active learning, human-in-the-loop machine learning, and high-stakes decision-making. It addresses the critical challenge of human discretion in labeling data, offering novel solutions and opening avenues for improving the efficiency and reliability of ML in high-risk applications. The work’s focus on real-world scenarios makes its findings especially impactful for researchers seeking to bridge the gap between theoretical advances and practical applications.

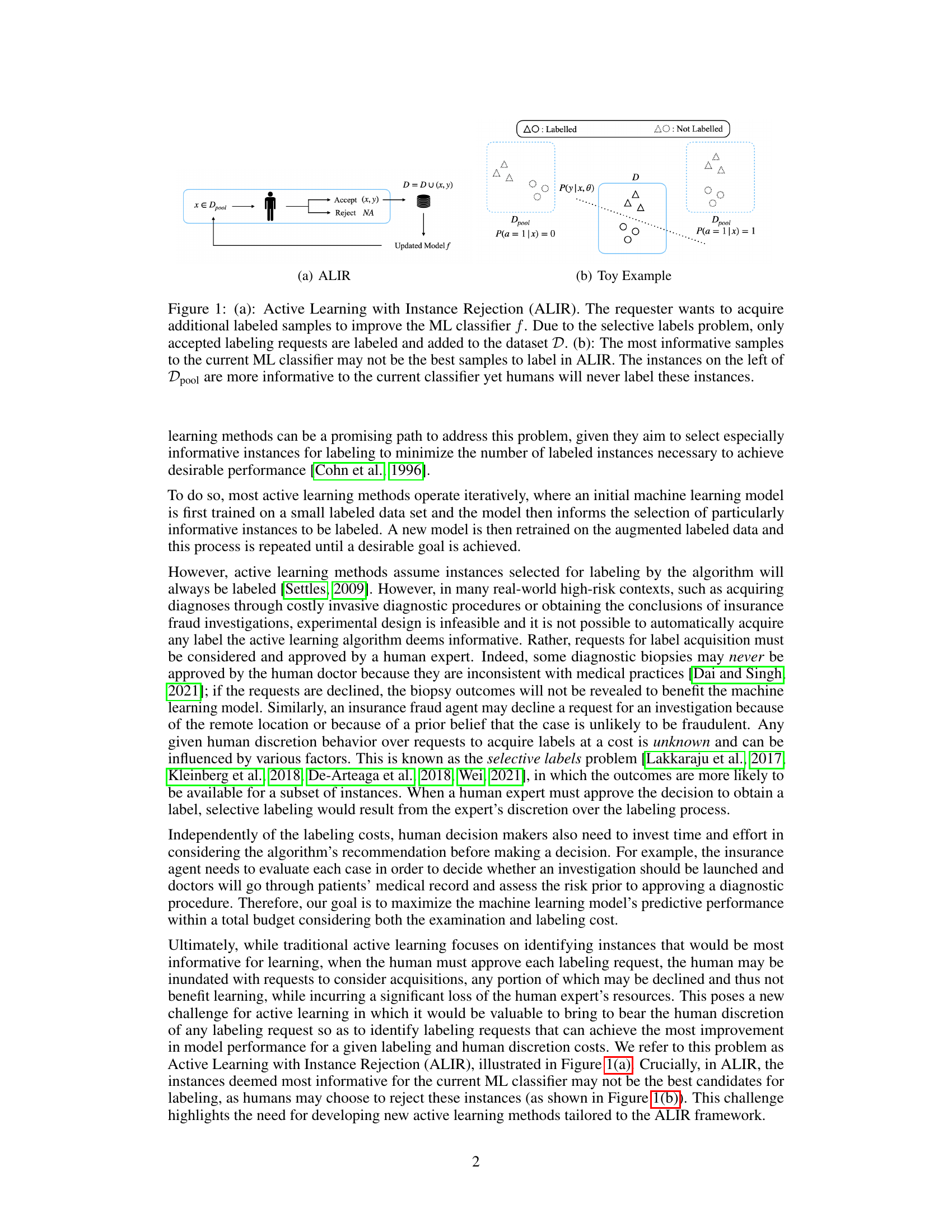

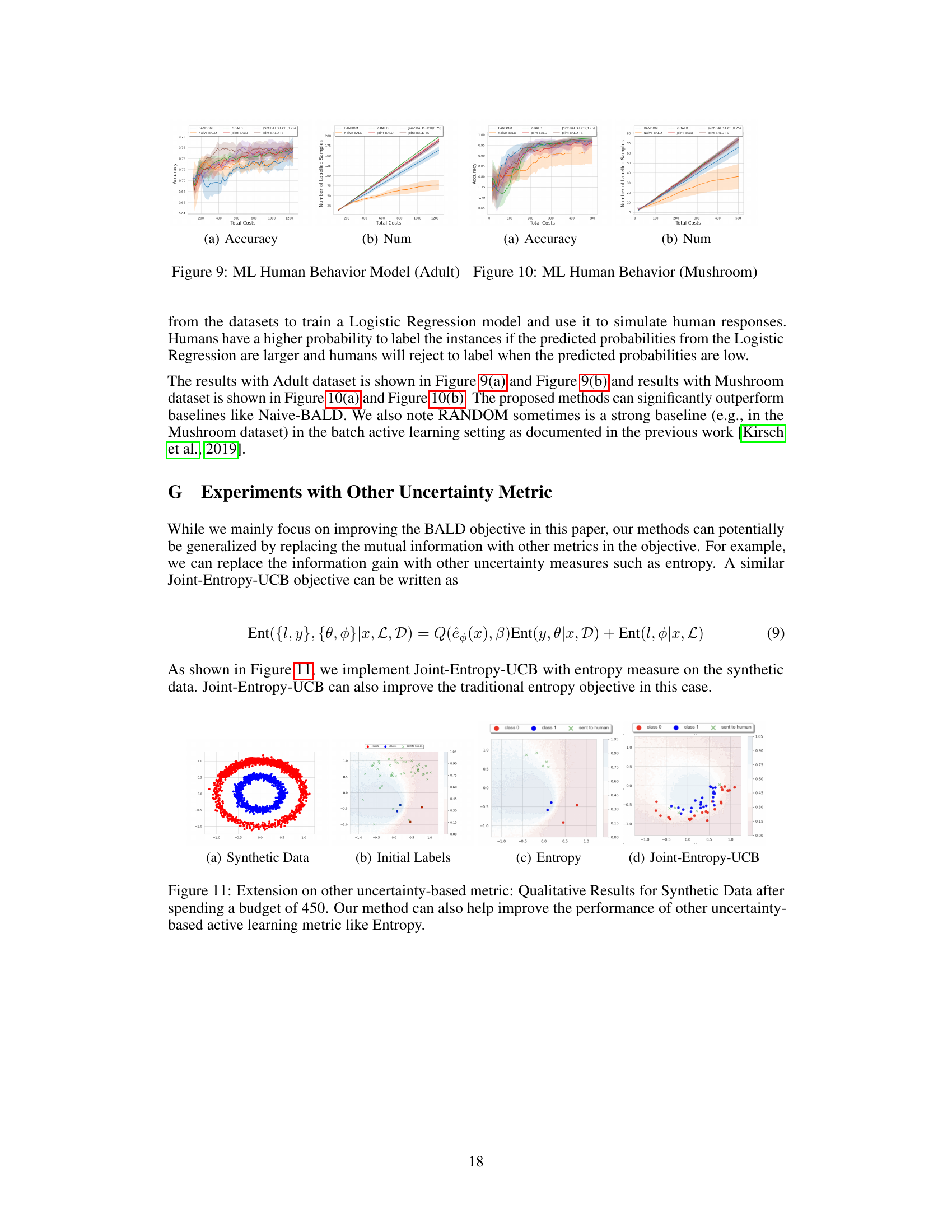

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the Active Learning with Instance Rejection (ALIR) framework. Panel (a) shows the general ALIR process: a machine learning model selects instances from a pool of unlabeled data (Dpool), a human decides whether to label each instance, and only accepted labeled instances are added to the training dataset (D). Panel (b) highlights a crucial aspect of ALIR: the most informative instances for improving the model (based on information gain) may not be the ones that humans actually label. Humans might reject some highly informative instances, making the active learning process more challenging.

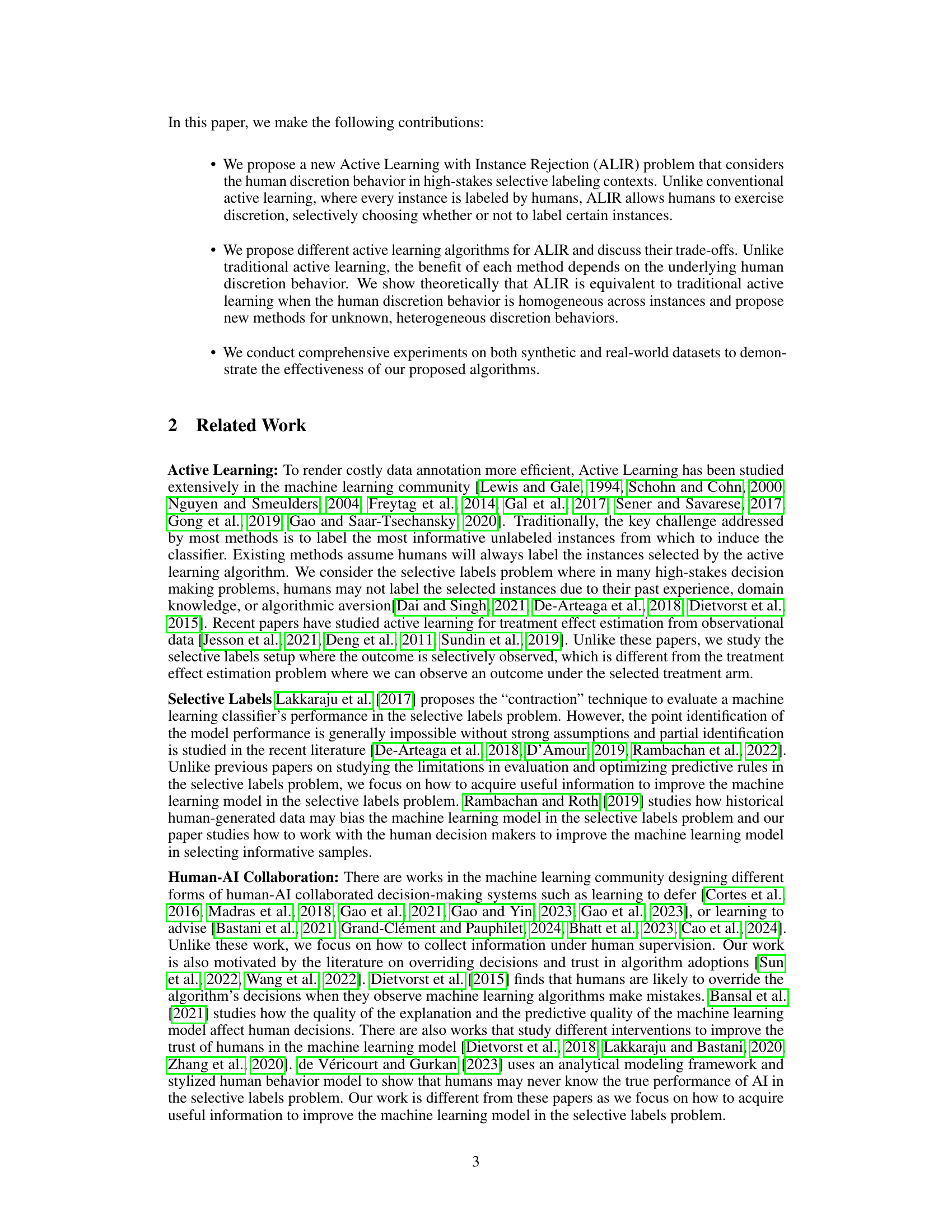

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different active learning methods on synthetic data, focusing on accuracy and resource allocation (examination vs. labeling). It highlights the trade-offs between different approaches, especially regarding the efficiency of label acquisition and the overall model accuracy achieved.

In-depth insights#

Selective Labels Issue#

The selective labels issue arises in machine learning when the availability of labels for data instances is not uniform, creating a biased dataset. This is common in high-stakes applications like medical diagnosis or fraud detection, where labeling is costly and experts may selectively choose which instances to label, leading to a non-random sampling of the data. This biased sampling fundamentally impacts model training and evaluation, as models are trained on a subset of data that doesn’t accurately represent the overall distribution. Consequently, model performance metrics can be misleading, and the model’s generalizability to unseen data is compromised. The challenge lies in accurately assessing model performance under selective labeling and in designing active learning strategies that efficiently guide the labeling process. Unlike conventional active learning, which assumes labels are always available for selected instances, addressing the selective labels issue requires considering human discretion in label acquisition. Methods for handling this often focus on accounting for the non-random sampling bias and developing techniques that improve model performance despite the limited labeled data. Ultimately, robust solutions must incorporate an understanding of human decision-making processes and aim to maximize the value derived from each label acquired.

SEL-BALD Algorithm#

The SEL-BALD algorithm, a novel approach to active learning, directly addresses the challenge of selective labeling with instance rejection. Unlike traditional active learning methods that assume all selected instances will be labeled, SEL-BALD explicitly models human discretion, acknowledging that experts might reject labeling certain instances due to cost, constraints, or other factors. This is achieved by incorporating a human discretion model alongside the standard machine learning model, allowing the algorithm to strategically select instances likely to be both informative and accepted for labeling. This two-pronged approach enhances efficiency by minimizing wasted resources on unlabeled instances. Furthermore, SEL-BALD introduces variations such as Joint-BALD-UCB and Joint-BALD-TS to further optimize the balance between exploration and exploitation in acquiring labels, thus enhancing the adaptability of the approach to various scenarios and human behavior patterns. The algorithm’s effectiveness is empirically validated through experiments on both synthetic and real-world datasets, showcasing its improved performance compared to naive methods that ignore the human element in label acquisition.

Human Discretion Model#

The concept of a “Human Discretion Model” within the context of a research paper focusing on active learning with instance rejection is crucial. It acknowledges that human labelers don’t passively annotate data; rather, they actively decide which instances to label, influenced by factors like cost, regulatory constraints, or perceived usefulness. Modeling this discretion is vital for efficient active learning because strategies that ignore human choice may select highly informative but ultimately unobtainable labels. A robust human discretion model would need to capture the complex interplay of factors influencing a human’s labeling decisions, potentially using techniques like Bayesian modeling or machine learning to predict the probability of a human accepting a labeling request for a given data point. The effectiveness of active learning algorithms hinges on the accuracy of this model. Without accurately capturing human discretion, active learning algorithms risk wasting valuable resources by requesting labels that are unlikely to be provided. Therefore, developing and validating this model is key to making active learning practical and efficient in real-world scenarios where human involvement is a critical component of the labeling process.

Synthetic Data Results#

A dedicated section on ‘Synthetic Data Results’ would ideally delve into the performance evaluation of the proposed selective labeling with instance rejection (SEL-BALD) active learning algorithms using synthetic datasets. Comprehensive results comparing SEL-BALD variants (e.g., Joint-BALD-UCB, Joint-BALD-TS) against baselines like RANDOM and Naive-BALD are crucial. The analysis should explore how the algorithms’ performance varies under different levels of human discretion behavior – ranging from homogenous (consistent labeling probability) to heterogeneous (varying probability depending on data instance). Key metrics to assess would be model accuracy, the number of samples labeled, and the total cost (considering both examination and labeling costs). Visualizations, such as plots showing decision boundaries and labeled data distributions for different algorithms, would enhance understanding. A discussion on the impact of budget constraints on algorithm performance and cost-effectiveness should be provided. The analysis should demonstrate scenarios where SEL-BALD outperforms traditional active learning by strategically selecting instances to label, thereby optimizing resources and achieving superior model accuracy. Finally, insights into the robustness of SEL-BALD to noise and uncertainty in human labeling patterns should be included.

Future Research#

The paper’s conclusion suggests several promising avenues for future research. Addressing the limitations of the current model regarding its assumption of a singular human behavior model is crucial. The model currently operates under the assumption that all human labelers share a homogeneous behavior pattern, which is unrealistic in real-world scenarios. Future work should explore heterogeneous human discretion behaviors using techniques like hierarchical models or mixture models to accommodate individual differences in decision-making processes. Furthermore, developing robust strategies for handling changing human behavior is essential. The paper hints that as machine learning models become more integrated into human decision workflows, human preferences and decision strategies may evolve, necessitating the development of adaptive active learning methods. This requires refining the human discretion model and integrating it with dynamic modeling techniques to reflect this behavioral evolution. Finally, exploring alternative human-AI interaction methods could greatly improve the effectiveness of selective labeling. Considering factors such as human cognitive load, trust in the algorithm, and cost-benefit analysis in the interaction design may reveal strategies for optimizing label acquisition. Exploring novel acquisition functions beyond BALD and incorporating cost-sensitive active learning methods could prove beneficial. In essence, future research should prioritize addressing model limitations regarding human behavior, improving adaptability to changing scenarios, and optimizing the human-AI collaboration aspects of selective labeling.

More visual insights#

More on figures

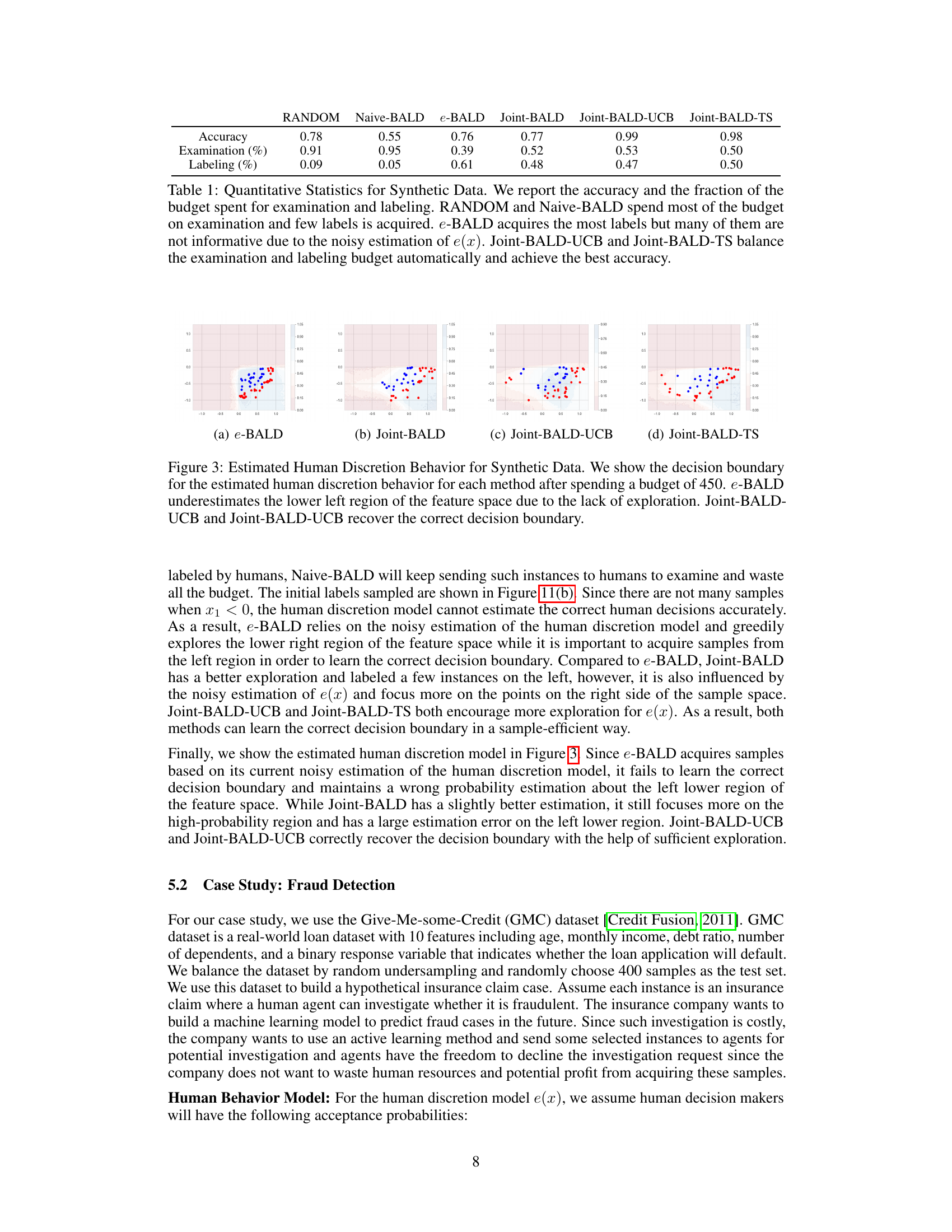

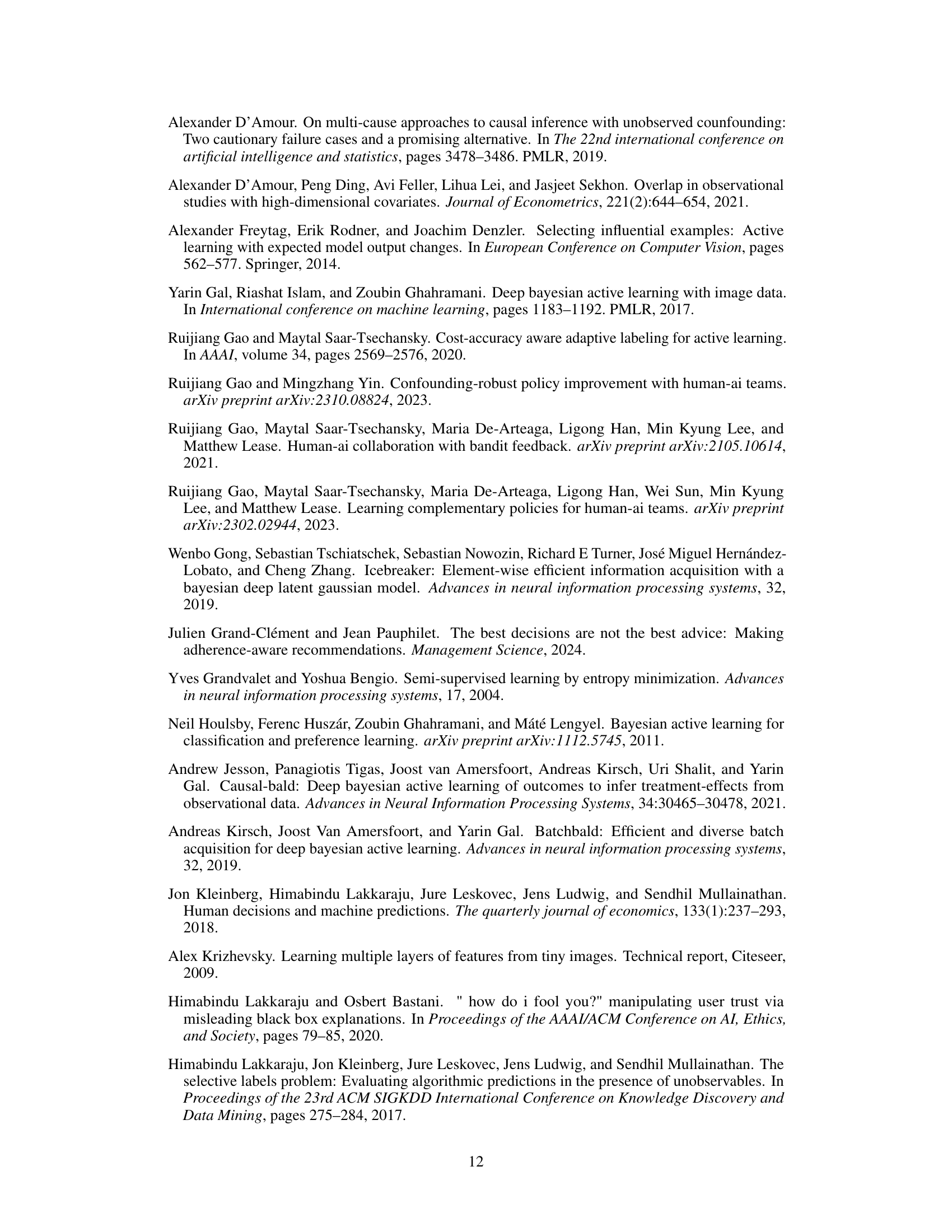

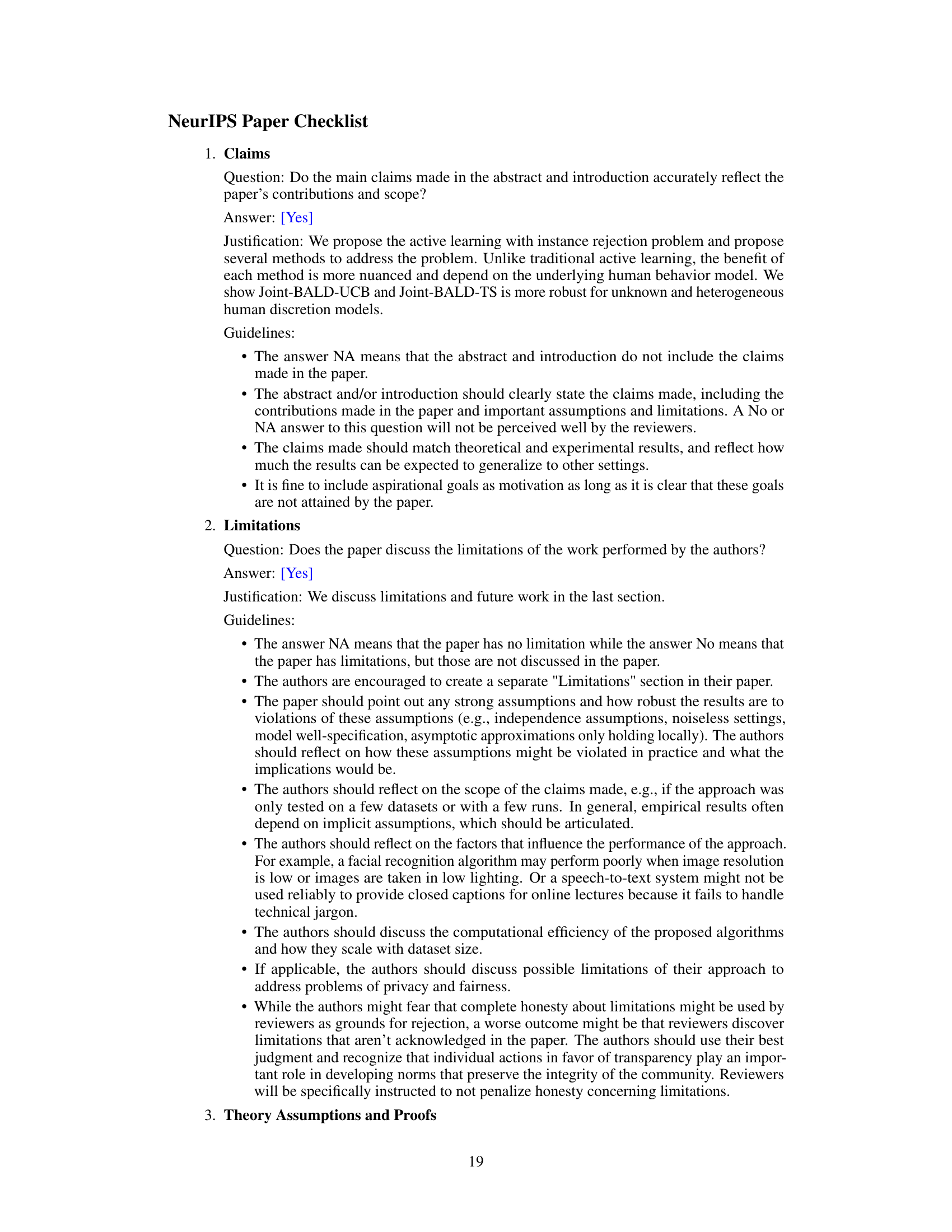

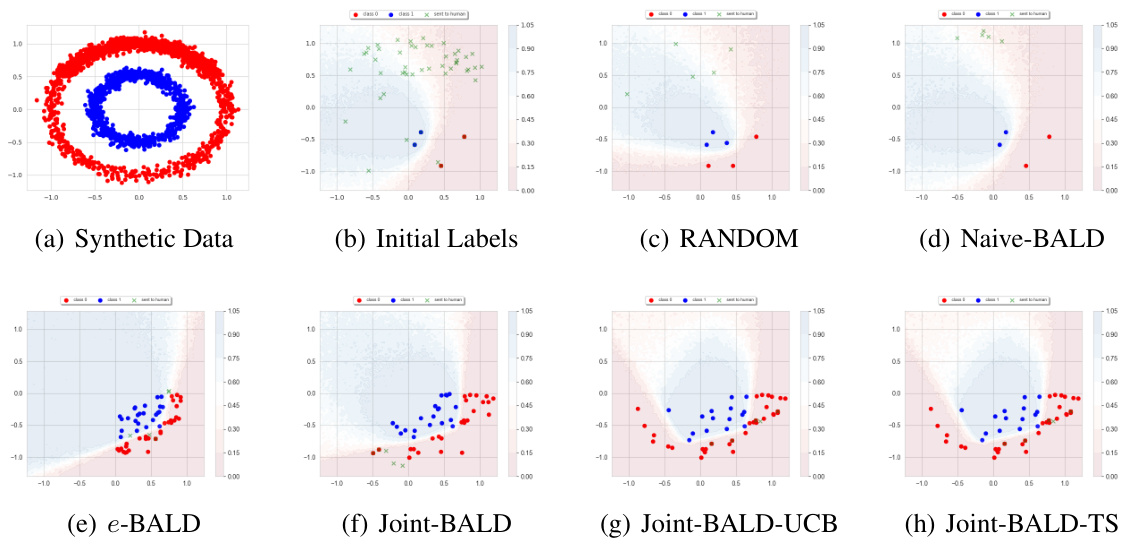

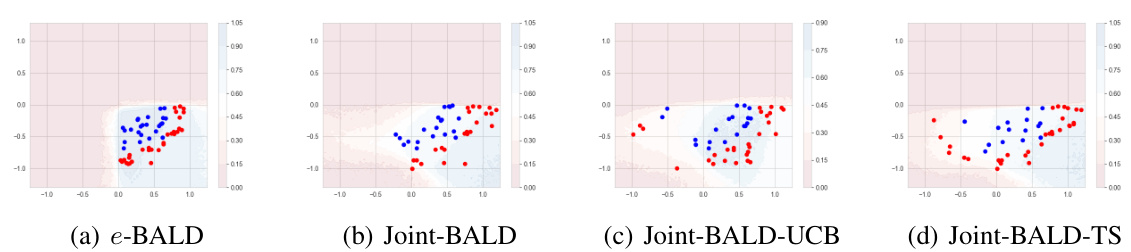

This figure compares different active learning methods’ performance on a synthetic dataset with selective labels. It visualizes the learned decision boundaries after a fixed budget, highlighting how different methods handle the trade-off between exploring informative samples and accounting for human labeler rejection.

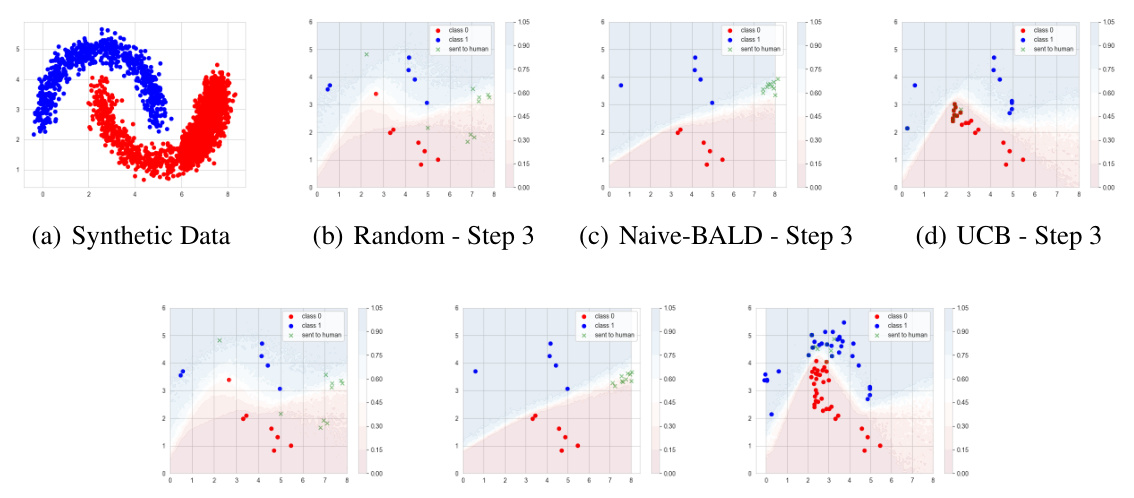

This figure shows a comparison of three active learning methods (Random, Naive-BALD, and Joint-BALD-UCB) on a synthetic dataset. The key difference is how the methods account for the human’s selective labeling behavior. The figure illustrates the labeled data after 3 and 9 steps, highlighting how Joint-BALD-UCB is more effective at selecting samples that are both informative and likely to be labeled by the human, while the other methods struggle. The dataset simulates a high-risk scenario where the human avoids labeling certain areas.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of different active learning methods on synthetic data with selective labels. It illustrates how the choice of algorithm affects the selection of samples for labeling, highlighting the trade-off between informative samples and samples likely to be labeled by a human. The results demonstrate that naive methods may waste resources on samples that are unlikely to be labeled, while the proposed methods are more effective at selecting samples for labeling.

This figure shows the results of three different active learning methods (Random, Naive-BALD, and Joint-BALD-UCB) on a synthetic two-moon dataset. The dataset simulates a scenario where human labelers selectively reject certain instances, particularly those with x0 > 6. The figure visually demonstrates how the different methods perform in this scenario, highlighting the effectiveness of Joint-BALD-UCB in selecting samples that are informative and are likely to be labeled by the humans. The top row shows results after 3 steps and the bottom row after 9 steps of active learning.

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of different active learning methods on synthetic data with selective labels. It shows the initial data distribution, initial random labels, and the resulting decision boundaries after applying different algorithms (RANDOM, Naive-BALD, e-BALD, Joint-BALD, Joint-BALD-UCB, Joint-BALD-TS). The visualization highlights how the algorithms handle the selective labeling problem, with some methods being more efficient in selecting informative labels than others, due to the human decision-maker’s tendency to reject high-risk instances.

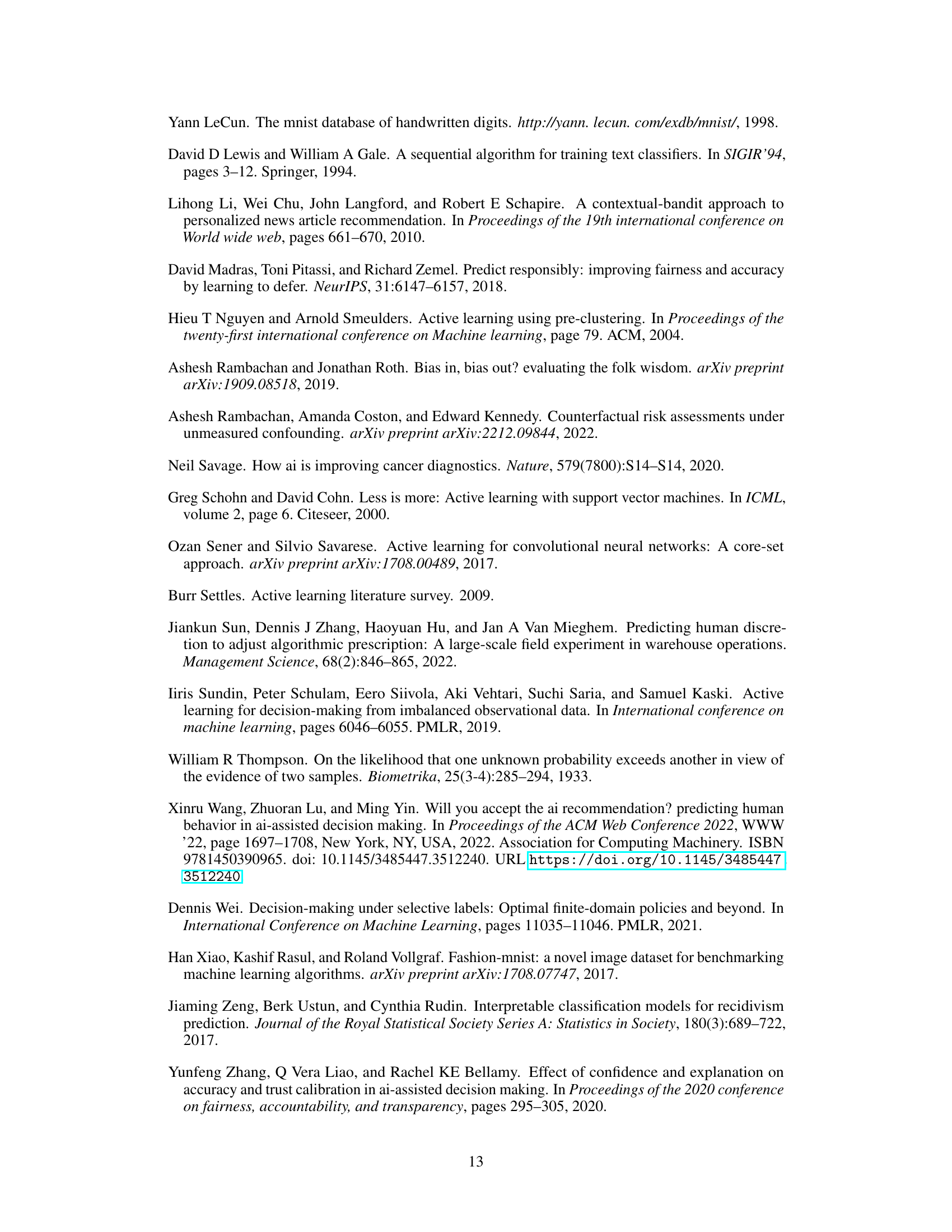

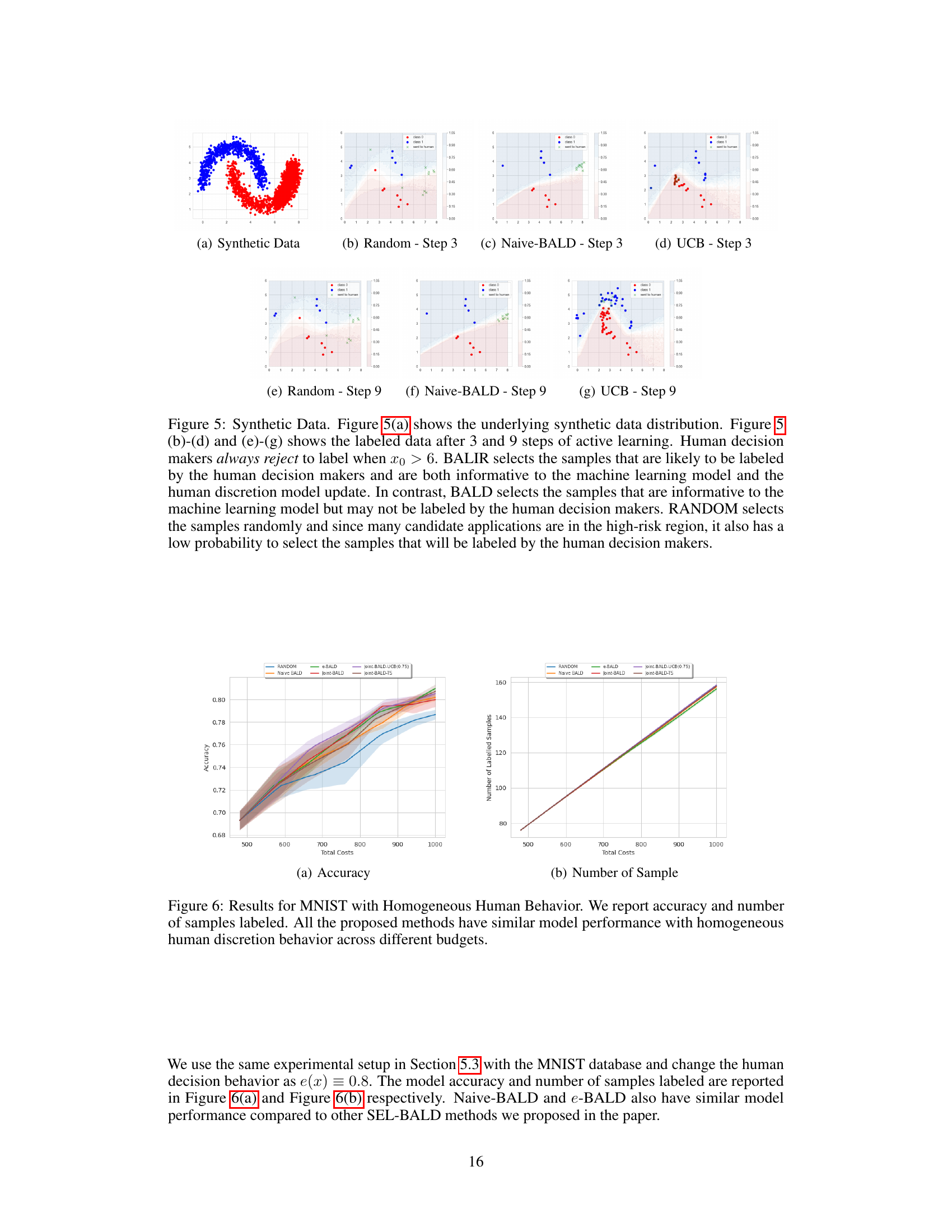

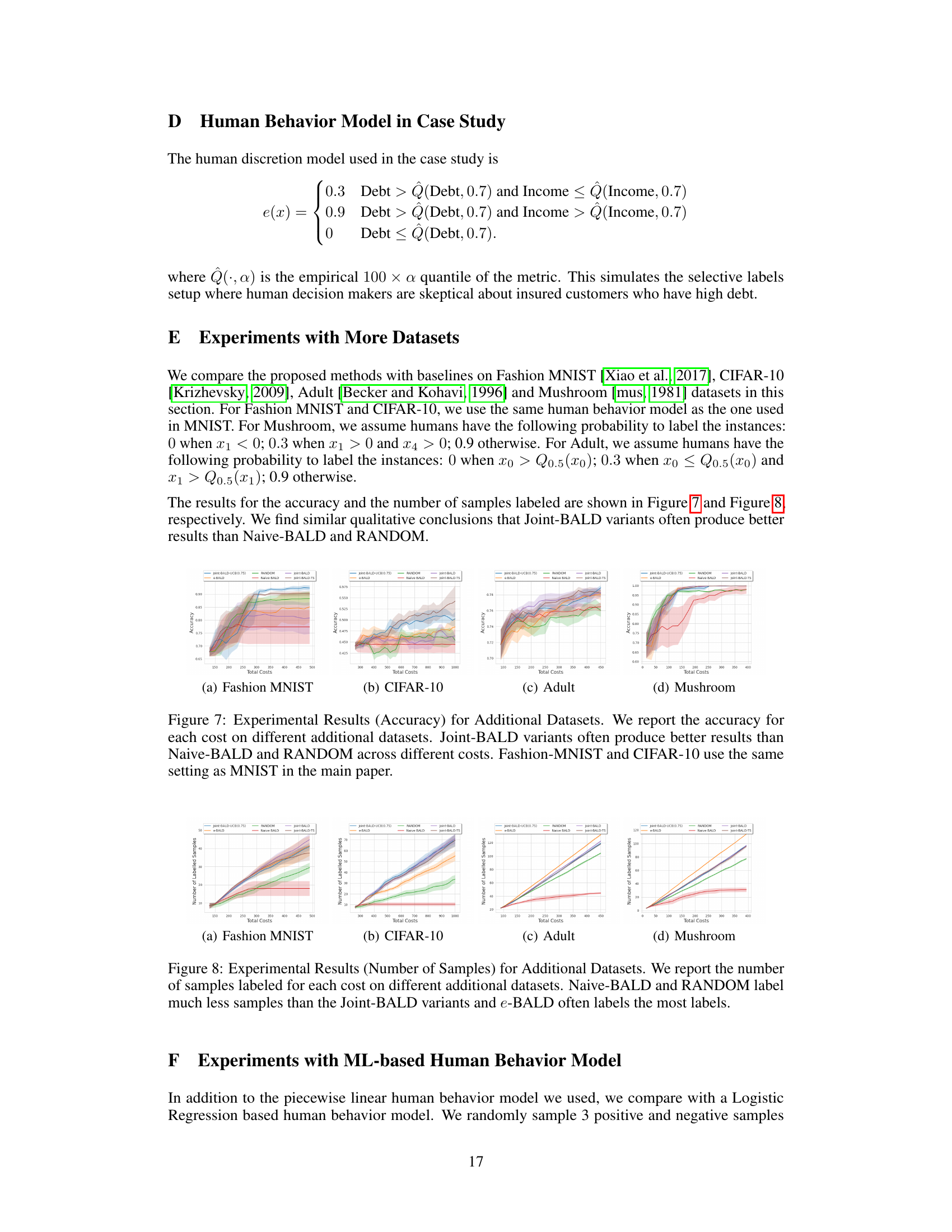

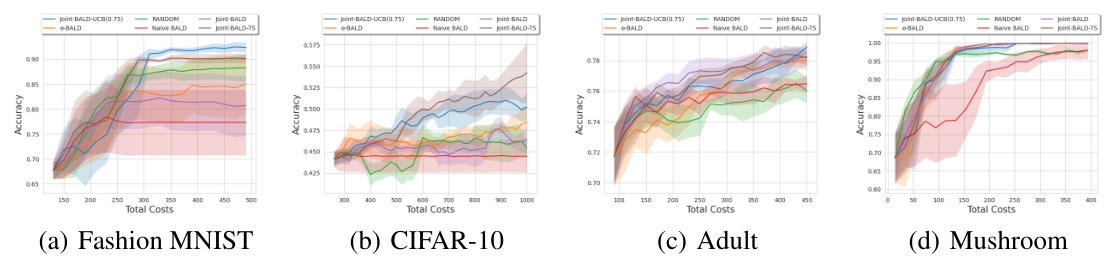

This figure presents the accuracy achieved by different active learning methods (RANDOM, Naive-BALD, e-BALD, Joint-BALD, Joint-BALD-UCB, and Joint-BALD-TS) across various total costs on four different datasets: Fashion MNIST, CIFAR-10, Adult, and Mushroom. The results show that the Joint-BALD variants generally outperform Naive-BALD and RANDOM, indicating their effectiveness in handling selective labeling scenarios with heterogeneous human behavior. The similar experimental setting to MNIST for Fashion MNIST and CIFAR-10 provides a comparative analysis.

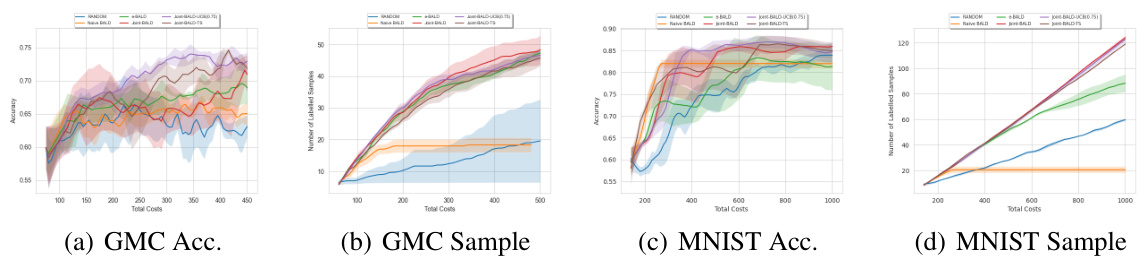

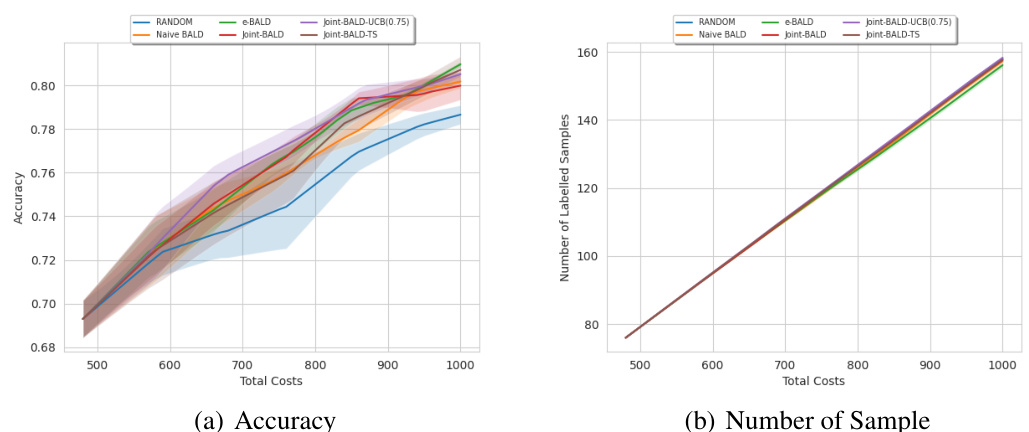

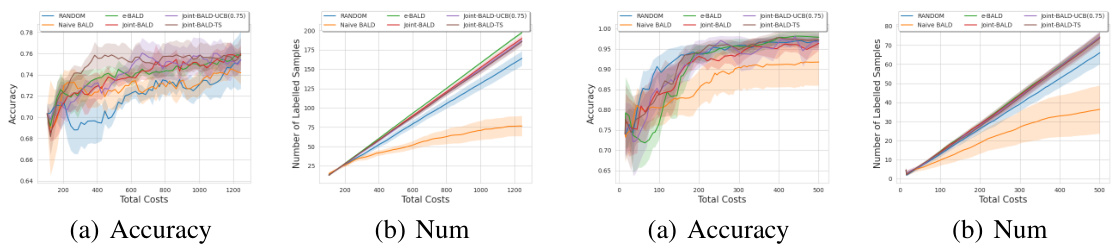

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on the Give-Me-Some-Credit (GMC) and MNIST datasets. The performance of several active learning algorithms is compared, namely RANDOM, Naive-BALD, e-BALD, Joint-BALD, Joint-BALD-UCB, and Joint-BALD-TS. The plots illustrate the accuracy and the number of labeled samples obtained for each method, across varying budget sizes. The key takeaway is that Joint-BALD-UCB and Joint-BALD-TS exhibit consistent, strong performance across different budget levels, unlike the other methods which are more sensitive to the human labeling behavior, which is explicitly not taken into account by RANDOM and Naive-BALD.

The figure shows the results of experiments conducted on two datasets: Give Me Some Credit (GMC) and MNIST. The plots compare the performance of several active learning methods, including RANDOM, Naive-BALD, e-BALD, Joint-BALD, Joint-BALD-UCB, and Joint-BALD-TS. The x-axis represents the total cost, while the y-axis shows either accuracy or the number of samples labeled. The results demonstrate that Joint-BALD-UCB and Joint-BALD-TS are more robust and achieve better performance across various budget constraints compared to methods that do not explicitly consider human discretion behavior.

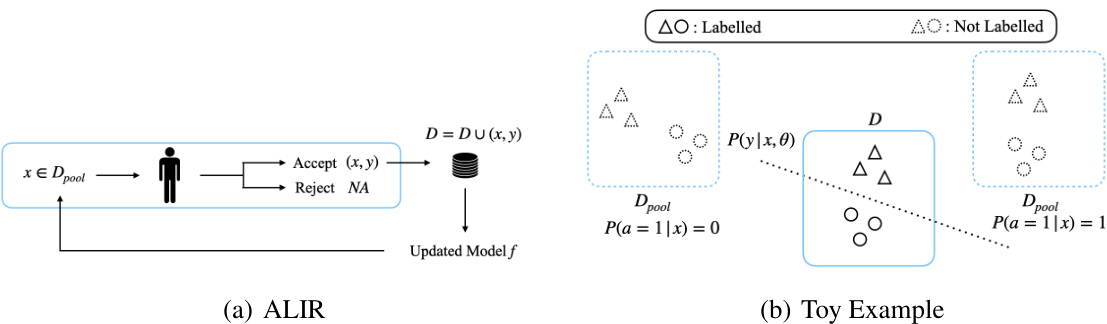

Figure 11 shows the results of applying the proposed Joint-Entropy-UCB method and other methods (Entropy, Naive-BALD, Random) to a synthetic dataset. The figure visualizes the decision boundaries learned by each method after a budget of 450 has been spent. The visualization highlights how Joint-Entropy-UCB, by incorporating both the human discretion model and the entropy uncertainty measure, effectively selects informative samples and achieves a more accurate decision boundary compared to other baselines. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method for enhancing the performance of uncertainty-based active learning techniques.

Full paper#