↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Gaussian Processes (GPs) are powerful probabilistic models but computationally expensive for large datasets. Existing approximation methods often lead to overconfidence or biased hyperparameter selection. This work introduces Computation-Aware Gaussian Processes (CaGP), addressing the limitations of existing methods.

CaGP incorporates computational uncertainty into the model, providing more reliable uncertainty estimates even with approximations. A novel training loss is proposed for hyperparameter optimization, leading to linear-time scaling. Experiments on large datasets demonstrate that CaGP significantly outperforms existing methods, showcasing its ability to efficiently handle large-scale GP training while maintaining accuracy and reliable uncertainty estimates.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Gaussian Processes, offering a novel approach to address the scalability challenges associated with large datasets. The proposed methods enable the training of GPs on massive datasets, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of uncertainty quantification, which has significant implications for various applications, from Bayesian optimization to decision-making under uncertainty. The development of linear-time inference and model selection techniques are significant advancements that expand the applicability of GPs to previously intractable problems.

Visual Insights#

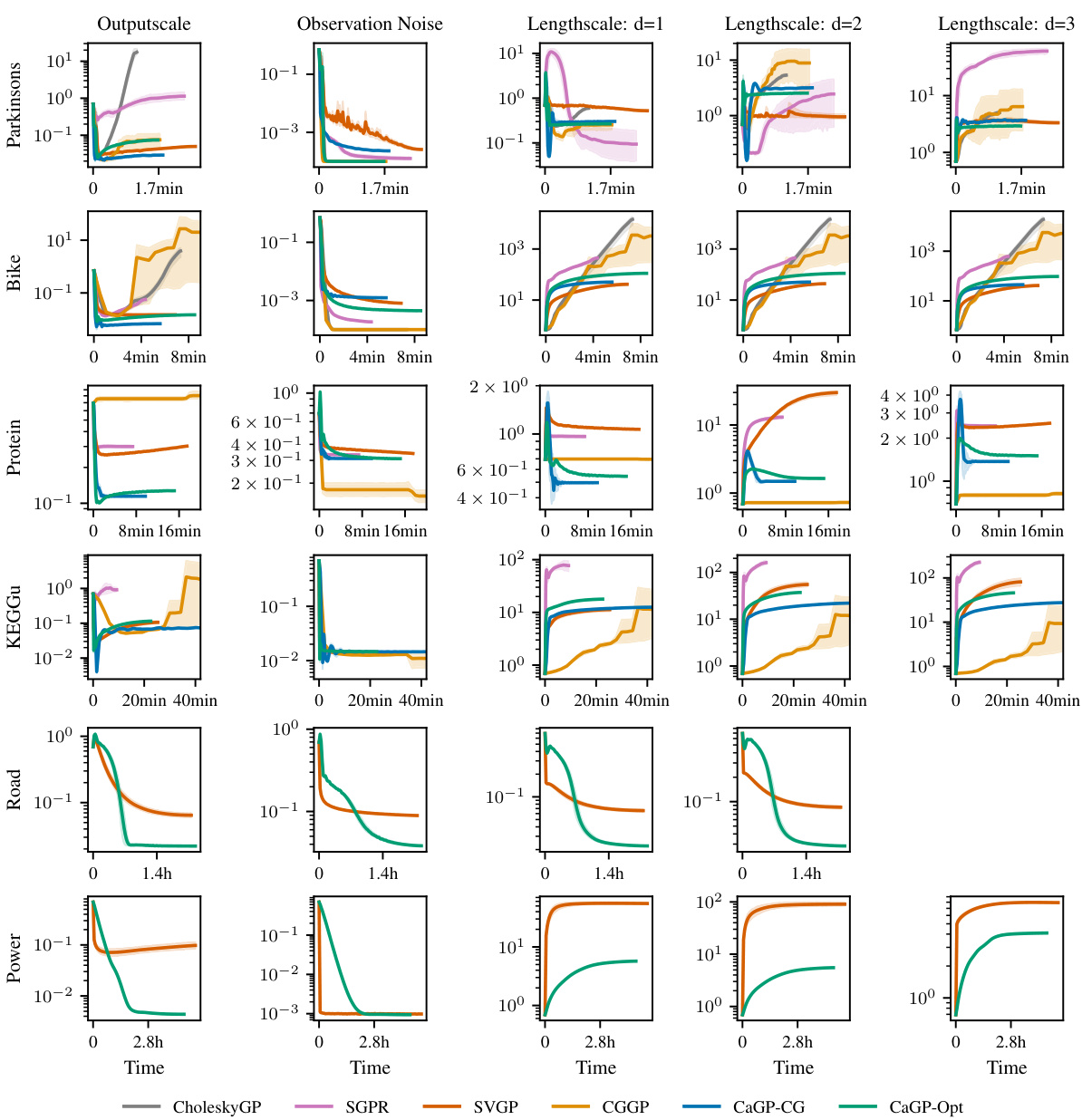

This figure compares the performance of four different Gaussian Process (GP) models on a synthetic dataset: an exact GP (CholeskyGP) and three scalable approximations (SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt). It showcases how the proposed computation-aware GP model (CaGP-Opt) provides a more accurate approximation of the posterior distribution, especially in data-sparse regions where SVGP fails to capture uncertainty.

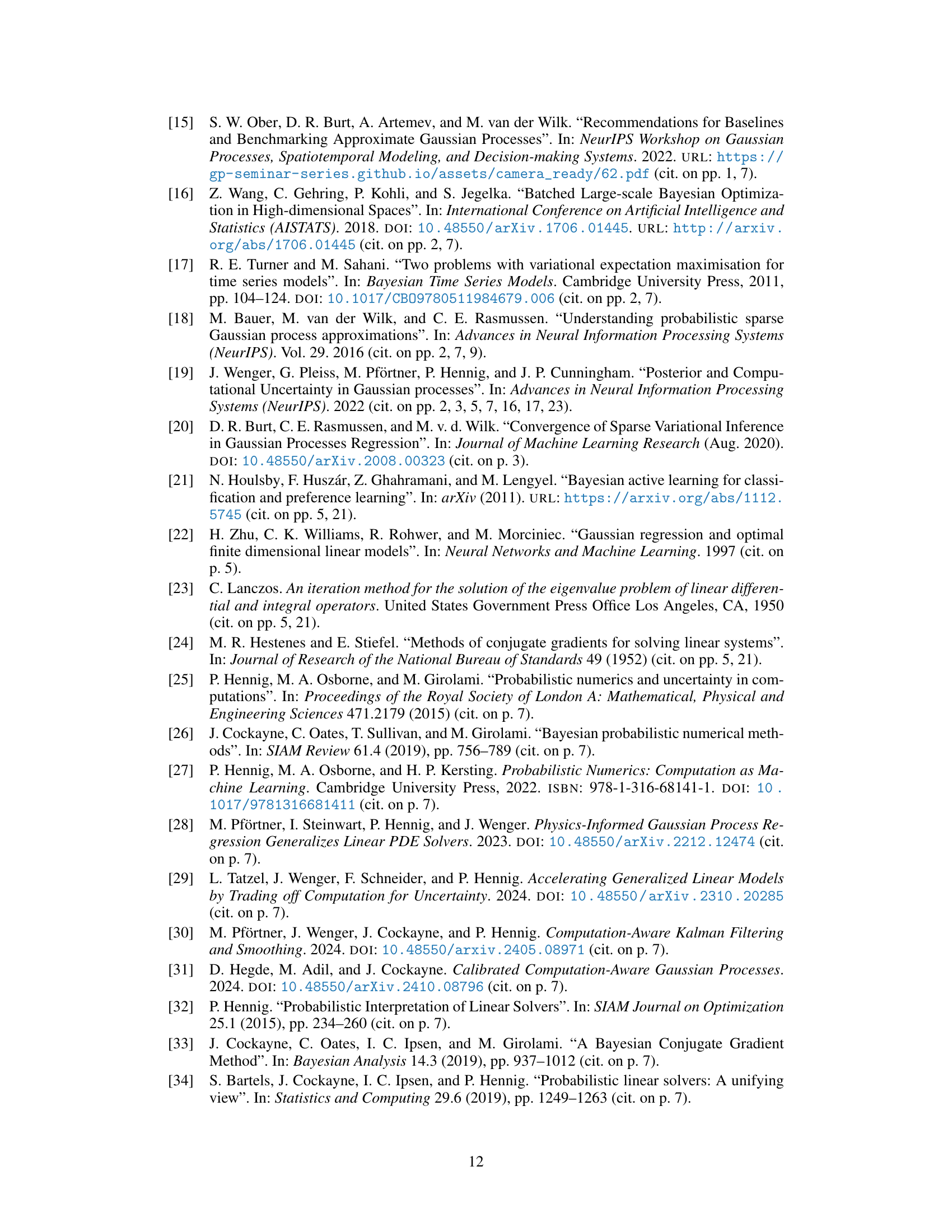

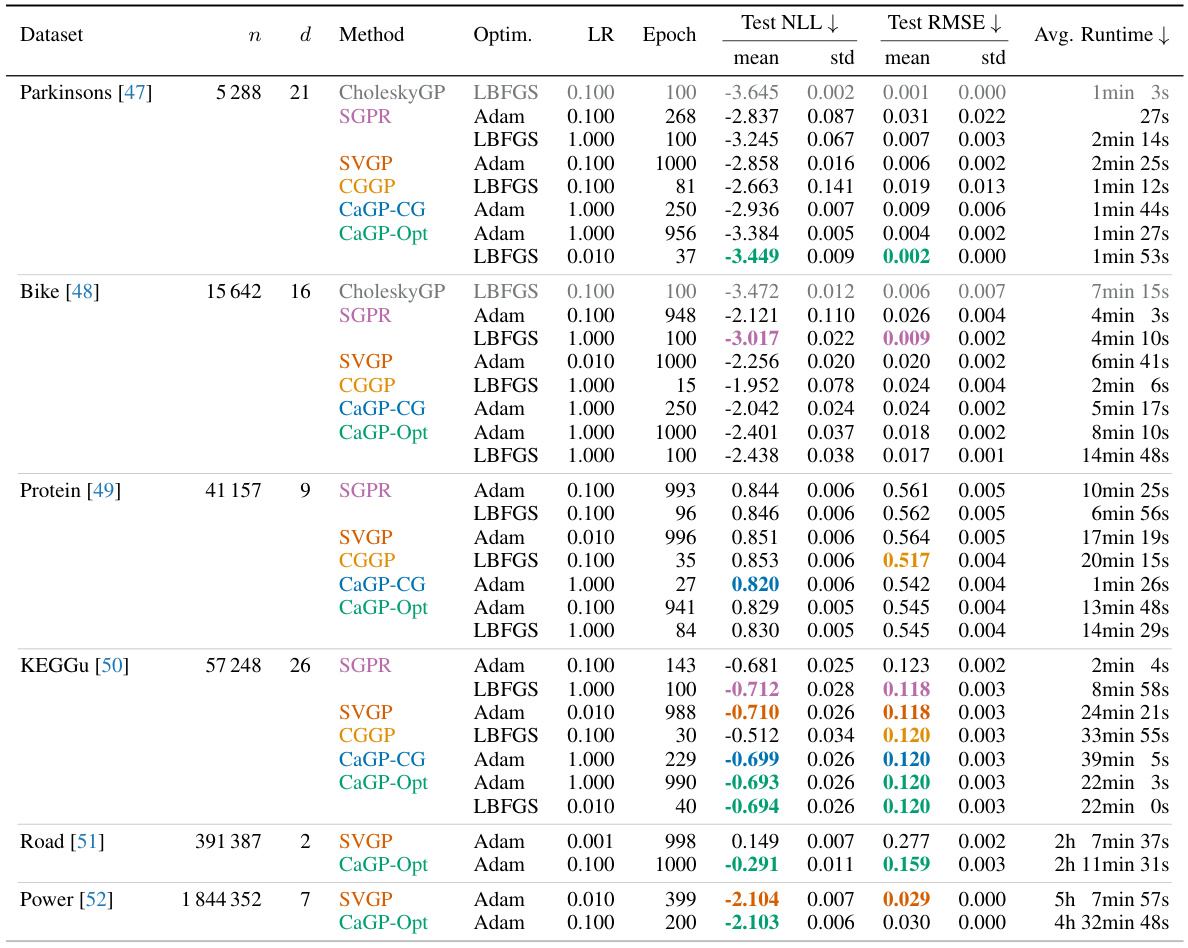

This table presents a comparison of different Gaussian process approximation methods on six UCI regression datasets. For each dataset and method, it reports the negative log-likelihood (NLL), root mean squared error (RMSE), and average runtime, all evaluated at the epoch with the best average test NLL across five random seeds and multiple learning rates. The best performing methods for each metric are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

CaGP Model Selection#

The core challenge addressed in ‘CaGP Model Selection’ is the computational cost associated with traditional Gaussian Process (GP) model selection, which scales unfavorably with dataset size. The authors introduce computation-aware Gaussian Processes (CaGP) to mitigate this issue. CaGP introduces a novel training loss function designed for hyperparameter optimization, enabling efficient model selection even for massive datasets. This new loss function leverages a sparse approximation strategy to achieve linear time scaling in dataset size, a significant improvement over the cubic complexity of exact methods. Crucially, the approach also incorporates and quantifies computational uncertainty, ensuring that the approximation errors are not underestimated, thus preventing the model from being overconfident in its predictions. Empirical evaluations demonstrate that CaGP outperforms or matches state-of-the-art methods (like SVGP and SGPR) in terms of generalization and runtime on a wide range of benchmark datasets, proving its effectiveness and practicality for large-scale GP applications.

Linear Time Inference#

Linear time inference in Gaussian processes (GPs) is a significant advancement because traditional GP inference scales cubically with the number of data points. This cubic scaling severely limits the applicability of GPs to large datasets. Achieving linear time complexity is crucial for scalability. The paper’s approach likely involves clever approximations, possibly employing sparsity-inducing techniques such as inducing points or variational methods. These approximations trade off some accuracy for computational efficiency, a common strategy in large-scale machine learning. The key to success lies in carefully managing the approximation error to ensure that the resulting inference is still accurate enough for the intended application while achieving linear time performance. A critical aspect is quantifying and controlling the uncertainty introduced by these approximations, which is essential for maintaining the probabilistic nature and reliability of GP predictions. The success of linear time inference directly impacts the practicality of GPs in various fields, expanding their applicability to problems with massive datasets that were previously intractable.

Uncertainty Quantification#

The paper focuses on enhancing Gaussian Processes (GPs) for large datasets by addressing the computational challenges while maintaining uncertainty quantification. A key problem highlighted is that existing scalable GP approximations often suffer from overconfidence, particularly in data-sparse regions, impacting the accuracy of uncertainty estimates. The authors introduce computation-aware GPs (CaGPs) which explicitly account for the approximation error by incorporating computational uncertainty, leading to more reliable uncertainty quantification. CaGPs achieve linear-time scaling, making them suitable for substantial datasets. Experiments demonstrate CaGP’s superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods such as SVGP, particularly in terms of uncertainty quantification in data-sparse areas, where CaGP provides more accurate and less overconfident uncertainty estimations.

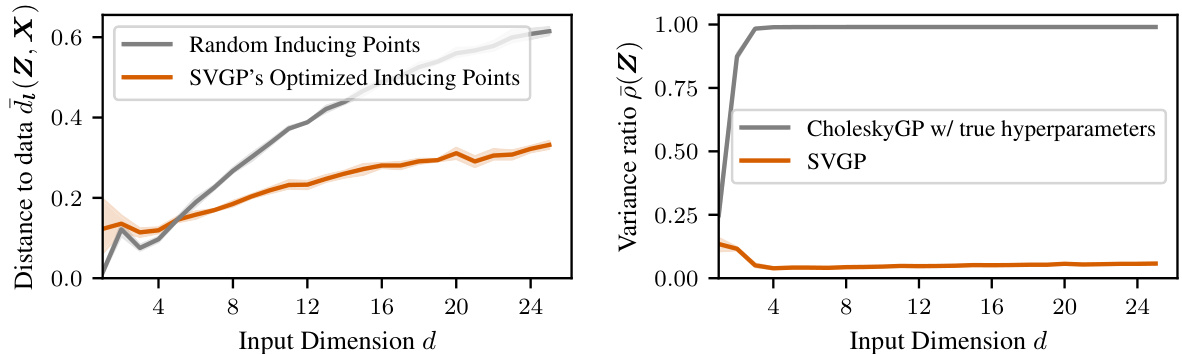

Action Choice Methods#

The effectiveness of computation-aware Gaussian processes hinges significantly on the strategy for selecting actions, which determine the dimensionality reduction applied to the data. The paper explores two primary action choice methods. The first leverages conjugate gradient (CG) residuals, offering a computationally efficient approach but potentially limiting the expressiveness of the lower-dimensional representation. The second method introduces learned sparse actions, where the actions are learned end-to-end alongside the hyperparameters, providing an adaptive, potentially more informative compression. This approach trades off computational cost for potential gains in accuracy and uncertainty quantification, as it allows the action selection to be informed by the optimization of the model’s hyperparameters. The choice between these methods involves a trade-off between computational efficiency and the quality of the low-rank approximation. Learned sparse actions show promise in achieving a balance between these competing goals, demonstrating improved performance in the experiments described within the research paper.

Future Work Directions#

Future research could explore extending computation-aware Gaussian processes (CaGPs) to handle non-conjugate likelihoods, enabling applications beyond regression. Investigating the theoretical properties of CaGPs under various data generating processes would strengthen the model’s guarantees. Improving the scalability of CaGPs through optimized sparse approximations or hardware acceleration techniques is another promising direction. Finally, adapting CaGPs to different model classes or integrating them with other machine learning techniques could lead to significant advancements. Exploring the relationship between computational cost and uncertainty quantification within CaGPs will provide valuable insight into its practical limitations and potential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

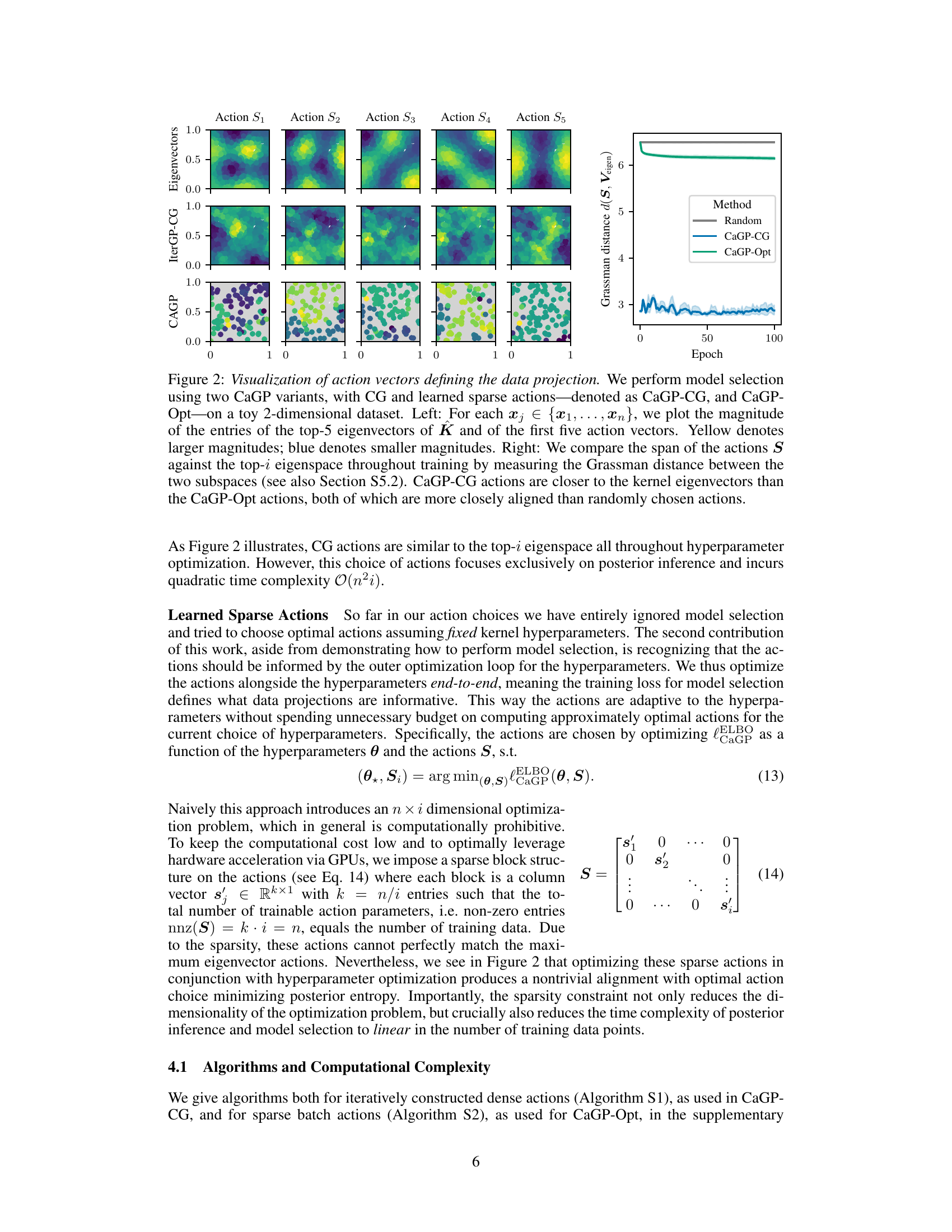

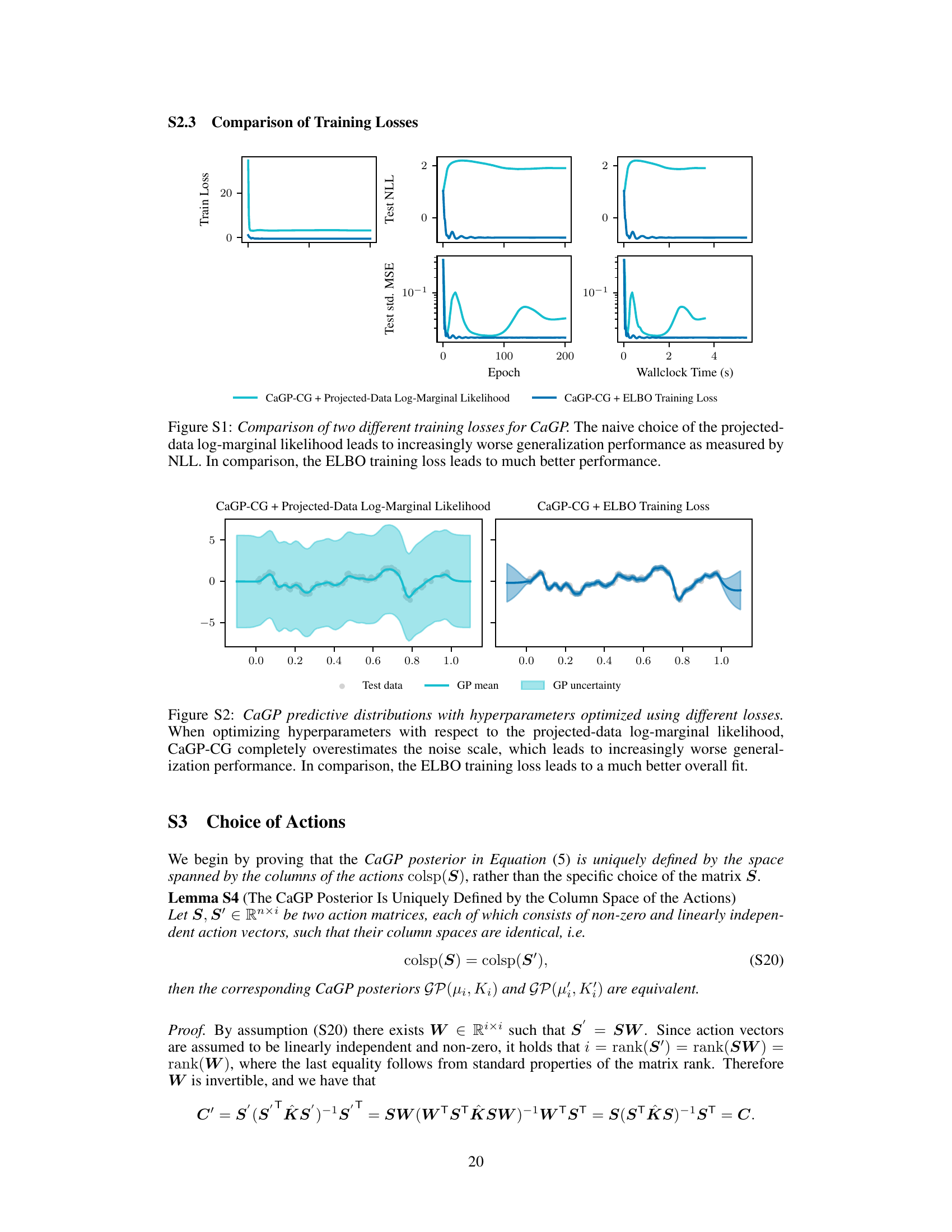

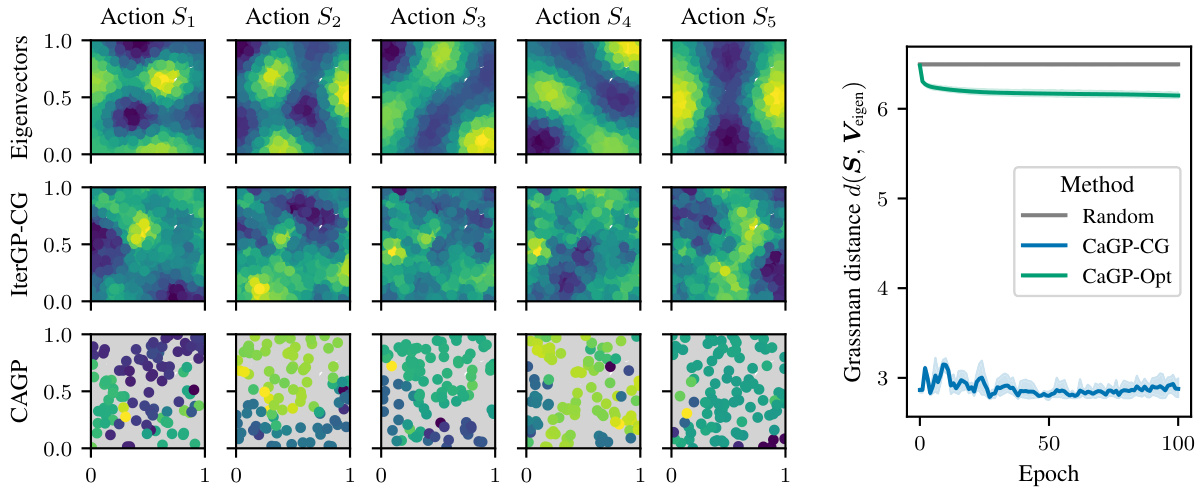

This figure visualizes how the learned sparse actions (CaGP-Opt) and the actions derived from the conjugate gradient method (CaGP-CG) compare to the top eigenvectors of the kernel matrix K. The left panel shows a heatmap of the action vectors and eigenvectors, illustrating their similarities and differences in terms of magnitude. The right panel shows the Grassman distance between the subspace spanned by the actions and the subspace spanned by the top eigenvectors over training epochs. The smaller the Grassman distance, the closer the alignment between the two subspaces. The results demonstrate that CaGP-CG actions are more closely aligned with the kernel’s eigenvectors than CaGP-Opt actions, suggesting a potential trade-off between optimization efficiency and alignment to the optimal action selection based on information theory.

This figure compares the performance of an exact GP posterior with three scalable approximations: SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt. It highlights the overconfidence issue of SVGP in data-sparse regions, where it expresses almost no posterior variance near the inducing point and attributes most variance to noise. In contrast, CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt, especially the proposed CaGP-Opt, show significantly more posterior variance, indicating better uncertainty quantification in these areas. The plot shows that although none of the methods perfectly recover the data-generating process, CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt show better posterior predictive distributions compared to SVGP.

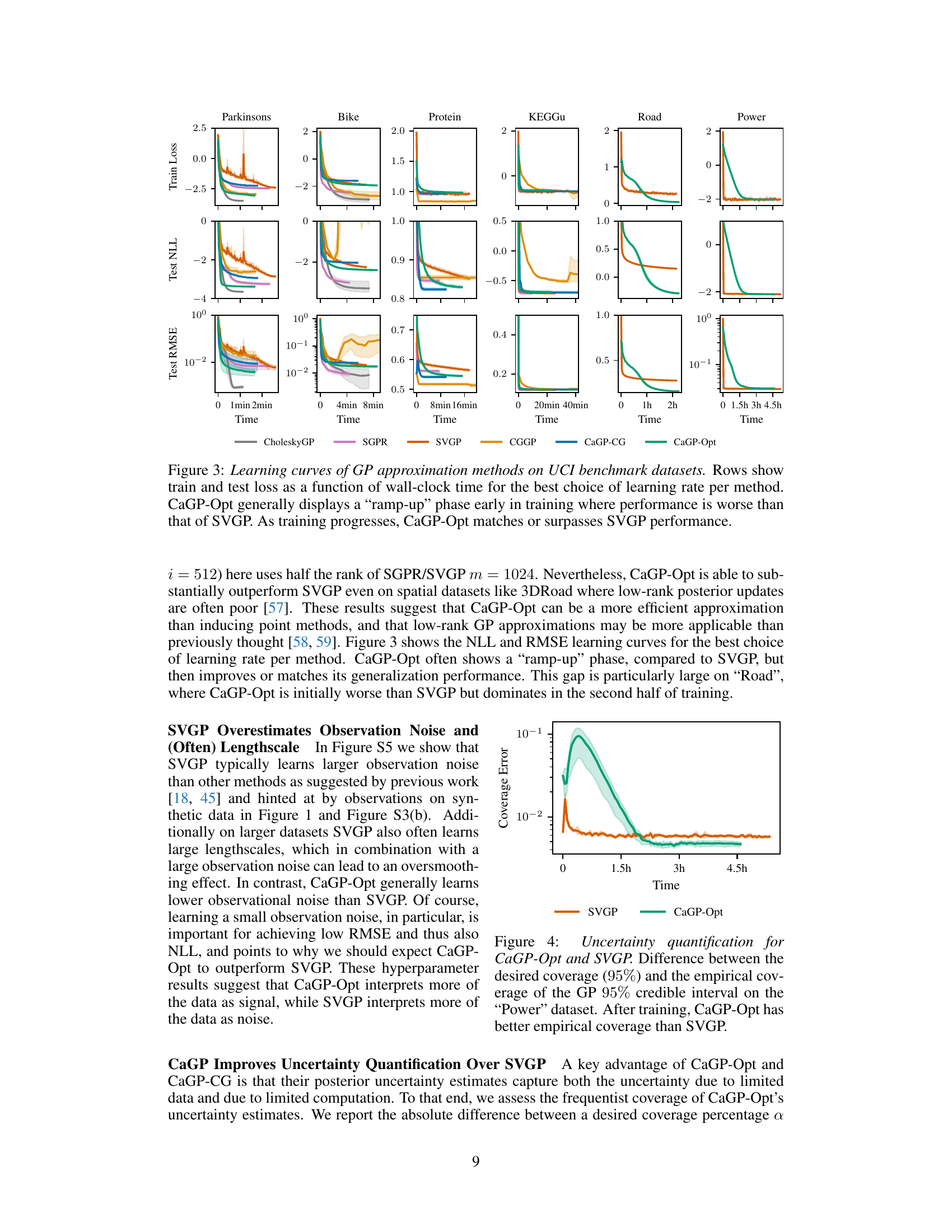

This figure compares the uncertainty quantification of CaGP-Opt and SVGP on the ‘Power’ dataset. Specifically, it shows the difference between the desired 95% credible interval coverage and the actual empirical coverage achieved by each method. The x-axis represents training time, and the y-axis shows the absolute difference in coverage percentage. The plot demonstrates that CaGP-Opt achieves better calibration (closer to the desired 95% coverage) than SVGP after training.

This figure compares the performance of an exact GP posterior with three scalable approximations: SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt. It highlights how CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt, unlike SVGP, maintain significant posterior variance even in data-sparse regions, leading to better uncertainty quantification. The figure also demonstrates how the different methods handle posterior mean predictions, showing CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt are closer to the exact GP’s predictions.

This figure compares the performance of an exact GP posterior with three scalable approximations (SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt). It highlights the overconfidence issue of SVGP in data-sparse regions, where it attributes most variance to observational noise. In contrast, CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt show more accurate uncertainty representation, even in areas lacking data. Hyperparameters for all methods were optimized using appropriate techniques.

This figure compares the performance of an exact Gaussian Process (CholeskyGP) with three scalable approximations: SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt. It highlights how CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt provide more accurate posterior estimates, especially in data-sparse regions where SVGP shows overconfidence by attributing variation to noise rather than uncertainty.

This figure compares the performance of an exact Gaussian Process (GP) with three scalable GP approximation methods: SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt. The plot shows the posterior predictive distributions for each method, highlighting the differences in uncertainty quantification. CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt, unlike SVGP, demonstrate more realistic uncertainty estimates, especially in regions with sparse data, showing their ability to better capture approximation error.

This figure compares the performance of an exact GP posterior with three scalable approximations: SVGP, CaGP-CG, and CaGP-Opt. The plot shows posterior predictive distributions for each method. While none perfectly recover the true process, CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt show much better agreement with the exact posterior than SVGP. Notably, SVGP exhibits near zero posterior variance in data-sparse regions, indicating overconfidence, unlike CaGP-CG and CaGP-Opt, which show appropriate uncertainty.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of different Gaussian process approximation methods on several UCI benchmark datasets. The metrics used are the negative log-likelihood (NLL), root mean squared error (RMSE), and wall-clock time. Results are averaged over multiple random seeds and learning rates, showcasing the best performance of each method in terms of NLL. The best-performing methods for each metric, considering standard deviation, are highlighted.

This table presents a comparison of different Gaussian process (GP) approximation methods on six UCI benchmark datasets for regression. The performance is evaluated using three metrics: negative log-likelihood (NLL), root mean squared error (RMSE), and wall-clock runtime. The best results for each method are shown across various learning rates, averaged over five runs with different random seeds. The table highlights the best performing approximate methods for each metric, indicating whether the difference from the best is statistically significant (more than one standard deviation).

This table presents a comparison of the generalization performance of different Gaussian process models on six UCI benchmark datasets. The metrics used are the negative log-likelihood (NLL), root mean squared error (RMSE), and wall-clock runtime. The best performing model for each metric is highlighted. Results are averaged across five random seeds and different learning rates.

Full paper#