↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many physical and chemical processes involve transitions between metastable states separated by high energy barriers. Standard simulations struggle to cross these barriers, leading to slow sampling and incomplete exploration of the state space. To overcome this, researchers often employ biased simulations. However, extracting accurate, unbiased information from such biased data remains challenging. This research addresses this limitation.

This paper proposes a novel framework for learning from biased simulations using the infinitesimal generator and the associated resolvent operator. The method is shown to effectively learn the spectral properties of the unbiased system from biased data. Experiments highlight the advantages over traditional transfer operator methods and recent generator learning approaches. Importantly, the method demonstrated effectiveness even with datasets containing only a few relevant transitions due to sub-optimal biasing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in molecular dynamics and other fields dealing with slow mixing systems. It offers a novel approach to extract reliable dynamical information from biased simulations, which are often necessary to overcome the limitations of conventional methods. The proposed method’s ability to recover unbiased dynamics from limited, biased data opens new avenues for research in various fields, accelerating the analysis of complex systems.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the workflow of the proposed method for learning unbiased dynamics from biased simulations. It starts with choosing a molecular system, running biased simulations with suboptimal collective variables, characterizing the system using descriptors, learning a representation using those descriptors, regressing the infinitesimal generator using the learned representation, and finally computing its eigenpairs to obtain timescales and identify metastable states. The key steps are highlighted with blocks, with arrows indicating the flow. The process uses the biased simulations data to learn an unbiased description of the system’s dynamics.

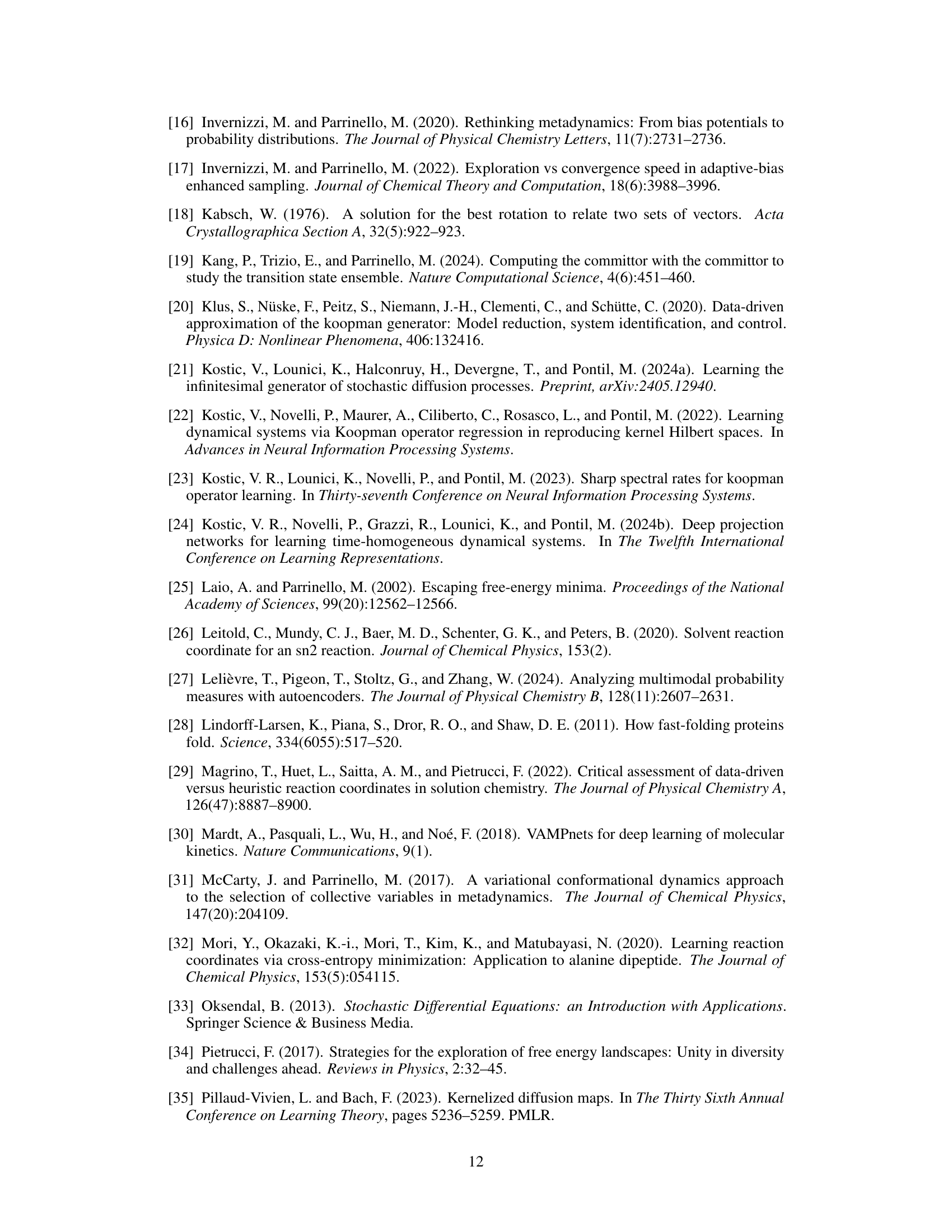

This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It lists mathematical symbols and their corresponding meanings, categorized for easier reference. The notations cover various aspects of the paper, including set theory, stochastic processes, potential energy functions, probability distributions, Hilbert spaces, operators, covariance matrices, and neural network components. This table is crucial for understanding the mathematical formalism presented in the paper.

In-depth insights#

Bias Mitigation#

Bias mitigation is crucial in machine learning, especially when dealing with real-world data. Addressing bias requires a multi-faceted approach, encompassing data collection, preprocessing, model training, and post-processing techniques. Data augmentation can balance class distributions, while algorithmic adjustments such as regularization or adversarial training can limit reliance on biased features. Careful feature engineering is key, prioritizing less biased and more representative attributes. Post-hoc bias detection and mitigation methods further refine the model’s fairness. Transparency is paramount; clearly documenting the biases present in data and the mitigation strategies is essential for trust and accountability. A successful bias mitigation strategy must consider the specific context and potential impacts, as what constitutes appropriate bias mitigation can change greatly across situations and datasets.

Generator Learning#

Generator learning, in the context of dynamical systems, focuses on learning the infinitesimal generator of a stochastic process. This approach offers several advantages over traditional methods like transfer operator learning. Instead of relying on a specific time lag, generator learning directly models the instantaneous dynamics, providing a more natural way to capture the system’s evolution. This is particularly useful when dealing with slow mixing processes, where long simulation trajectories are needed for accurate transfer operator estimation. However, generator learning presents challenges due to the unbounded nature of the generator, requiring careful regularization techniques to ensure stable and accurate learning. The use of resolvent operators is a common approach to circumvent this issue. Moreover, learning from biased simulations, where the system dynamics are perturbed to accelerate sampling, poses significant difficulties. Therefore, methods that robustly learn from biased data are highly valuable and are a key area of active research in this field.

Deep Learning#

Deep learning’s application in research papers often involves using artificial neural networks with multiple layers to analyze complex data. This approach excels at identifying intricate patterns and relationships within data, surpassing traditional methods in tasks like image recognition and natural language processing. In the context of a research paper, deep learning might be used for feature extraction, simplifying complex datasets for downstream analysis, or directly used for prediction or classification, providing novel insights and models. The choice of architecture (e.g., convolutional neural network, recurrent neural network) significantly impacts the application, reflecting specific data types and the research question. Careful consideration of the training data, including its size and representativeness, is crucial, as deep learning models can be sensitive to bias and overfitting. Finally, interpreting the learned model’s parameters and decision-making process remains a significant challenge, often necessitating rigorous validation and techniques to build trust and explainability into the models.

Rare Event#

The concept of ‘rare events’ in the context of a research paper likely involves the study of infrequent or unusual occurrences within a system or process. These events, while uncommon, often hold significant importance, potentially revealing crucial insights into the underlying mechanisms. Their rarity poses challenges for data acquisition, necessitating specialized techniques such as enhanced sampling methods or long simulations to gather sufficient data. Analysis of rare events might involve statistical methods focusing on low-probability occurrences, possibly incorporating advanced machine learning approaches to identify patterns or predictors. The goal of understanding rare events is frequently to unveil critical transition pathways, elucidate mechanisms of infrequent transformations, or gain deeper knowledge of exceptional behaviors. The insights extracted can have profound implications in various fields, informing predictive modeling, optimizing system performance, or even unraveling the dynamics of complex, real-world phenomena.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the method to time-dependent bias potentials would significantly broaden its applicability in molecular dynamics simulations. This involves adapting the theoretical framework and algorithms to handle evolving bias functions. Another key area is improving the efficiency of the deep-learning approach, potentially through more sophisticated neural network architectures or optimization strategies. Addressing the computational cost associated with high-dimensional systems is crucial for real-world applications. Finally, investigating the generalization capabilities of the learned generator to unseen systems or conditions is essential to establish its robustness and predictive power. Incorporating rigorous uncertainty quantification into the model outputs would further enhance its reliability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

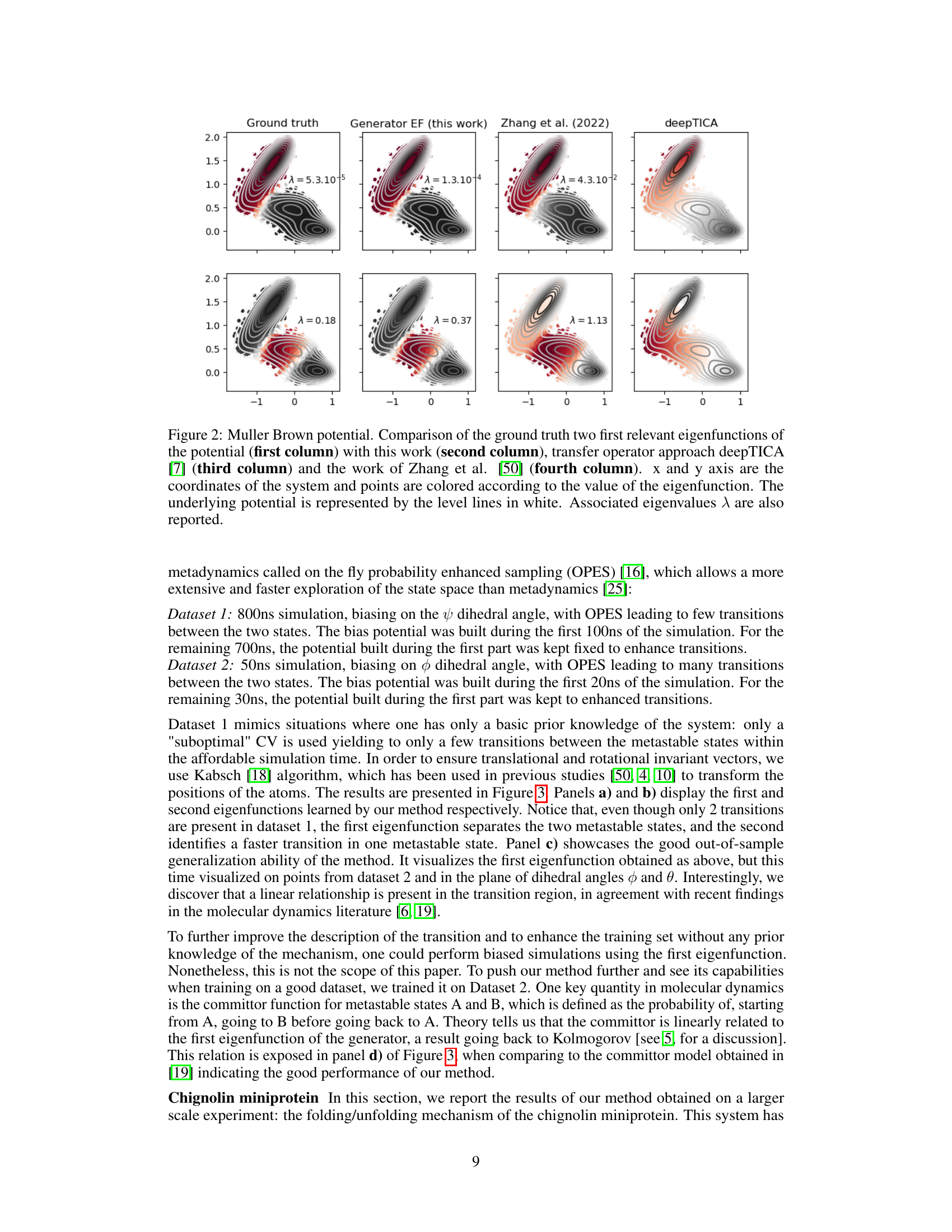

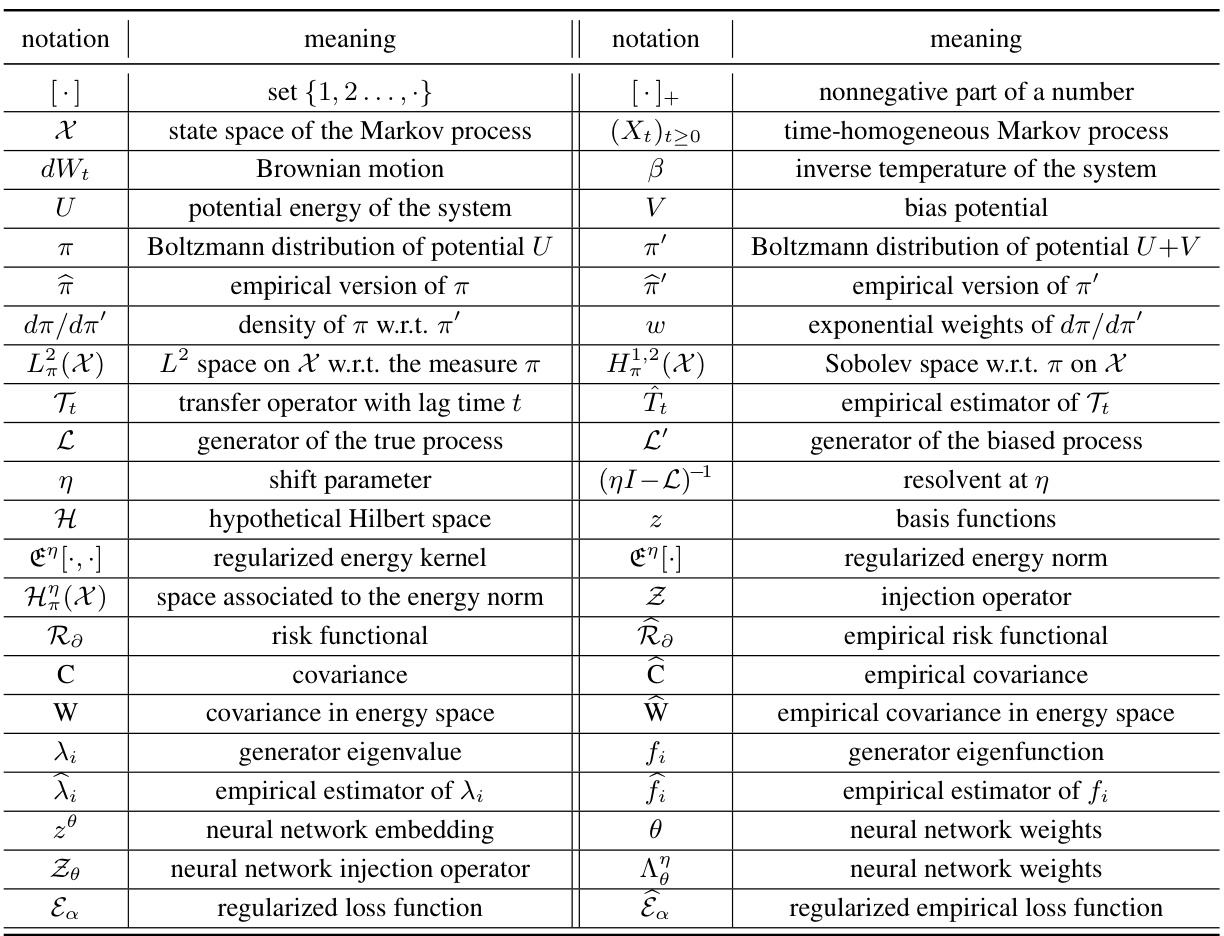

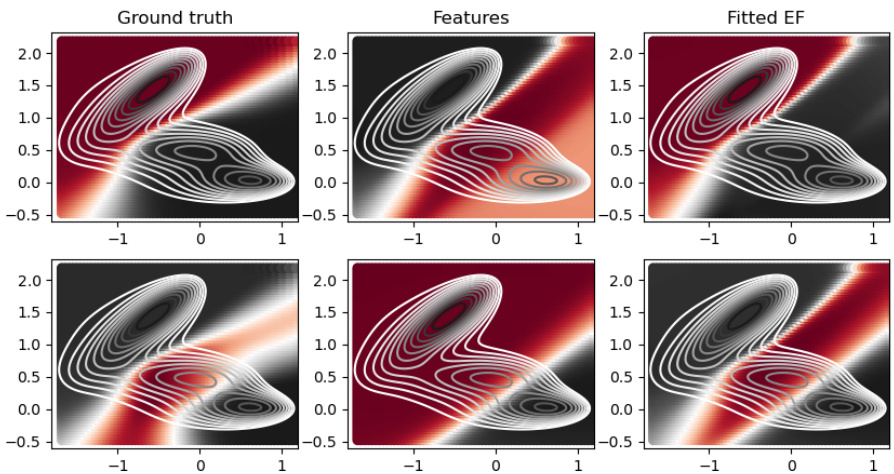

This figure compares the performance of the proposed method against other state-of-the-art methods on the Muller Brown potential. The figure shows the ground truth eigenfunctions alongside the eigenfunctions learned by the proposed method, deepTICA, and Zhang et al.’s method. The comparison is based on the visual similarity of the eigenfunctions, indicated by color intensity representing the function value at each point in the state space, along with the corresponding eigenvalues (λ). The level lines of the Muller Brown potential are overlaid to provide context.

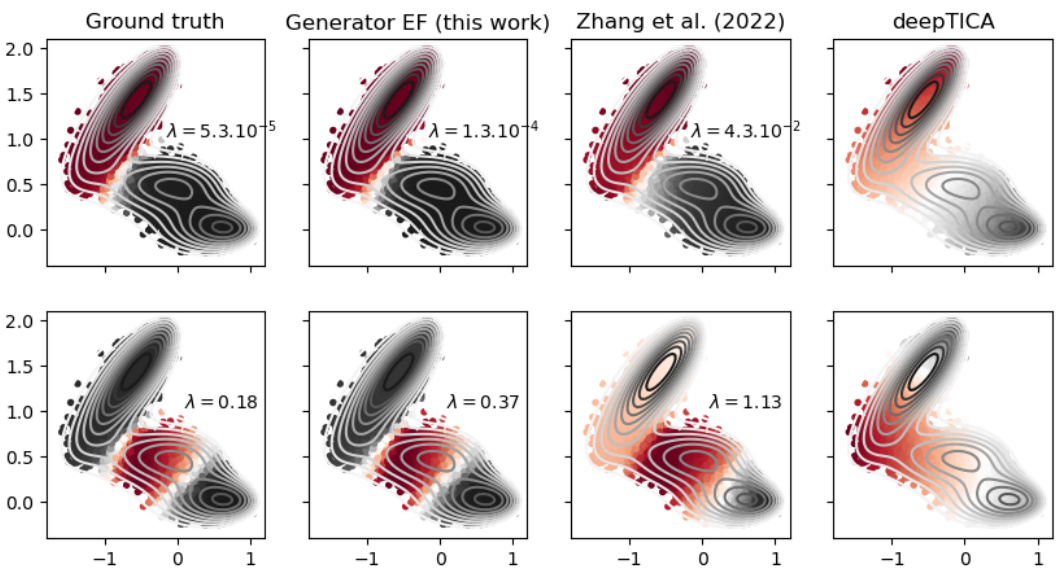

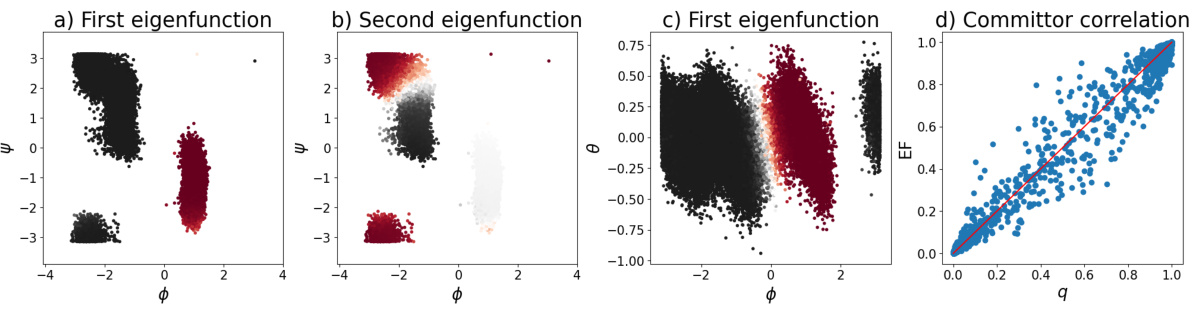

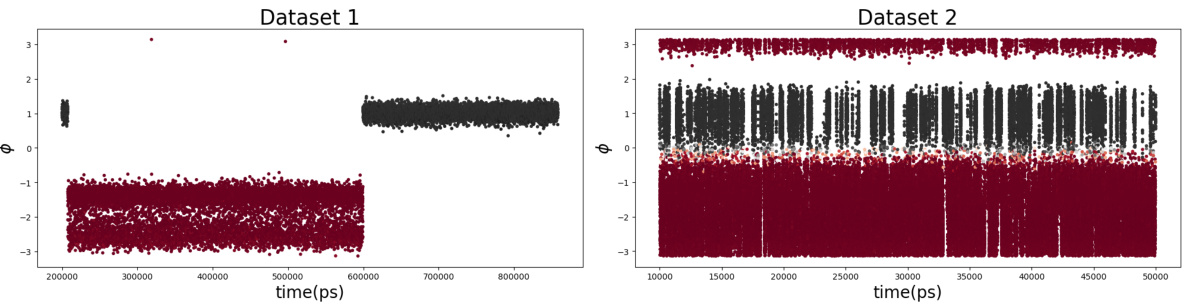

This figure presents results of applying the proposed method to alanine dipeptide. Panels (a) and (b) show the first two eigenfunctions learned from a dataset with few transitions due to suboptimal collective variables. Panel (c) demonstrates the method’s ability to generalize well, even with limited data, by showing the first eigenfunction on a different dataset. Finally, panel (d) compares the learned first eigenfunction to the committor function, showing a strong correlation.

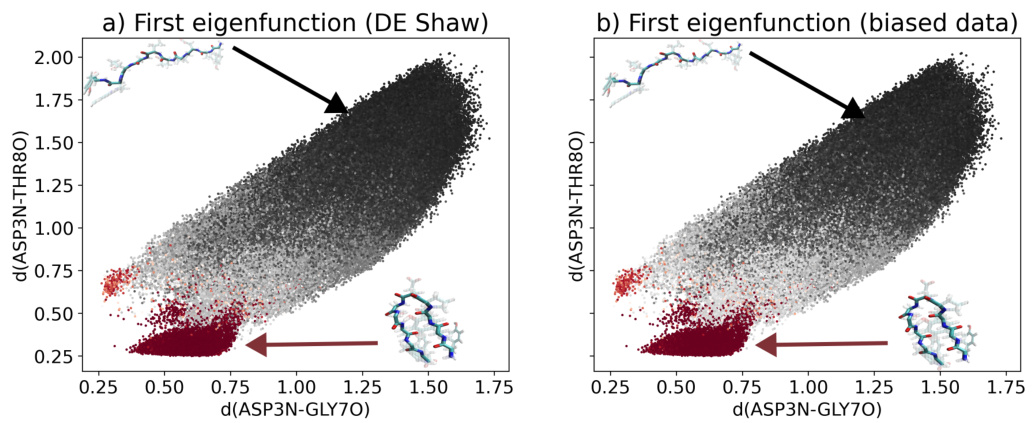

This figure compares the results of the proposed method applied to the chignolin miniprotein with results obtained using an unbiased trajectory. Panel (a) shows the first eigenfunction obtained using an unbiased trajectory from D.E Shaw research, while panel (b) shows the first eigenfunction obtained using the biased data generated by the proposed method. The data points are colored according to the value of the eigenfunction, allowing visualization of the folded and unfolded states of the protein in the two dimensional space defined by the distances between specified atoms. The figure highlights the similarity in the results obtained using unbiased and biased data, demonstrating the effectiveness of the method in learning from biased simulations.

The figure shows the typical behavior of the loss function during training. The training loss (blue) and test loss (orange) are plotted against the epoch number. The loss starts high, rapidly decreases, and then plateaus at a lower value as the network converges. The plateaus indicate that the network has learned a new eigenfunction orthogonal to the previous ones, and the network explores the subspace before learning a new eigenfunction. This behavior is helpful in determining the optimal stopping point for training.

This figure compares the results of four different methods for estimating the two most important eigenfunctions of the Muller Brown potential energy surface. The first column shows the ground truth eigenfunctions. The second column presents the results from the method described in the paper. The third column shows results obtained using deepTICA, a transfer operator-based approach. The final column displays results from the work of Zhang et al. (2022), another generator learning method. The visualization uses a color scale to represent the eigenfunction value at each point in the configuration space (x,y), while contour lines show the potential energy landscape.

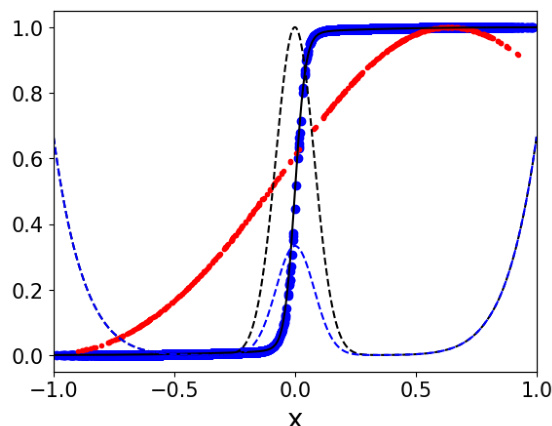

This figure compares the performance of the proposed method against the ground truth and a transfer operator-based approach on a one-dimensional double-well potential. The black dashed line shows the true double-well potential, while the blue dashed line represents the effective biased potential used in the simulation. The blue points depict the results obtained using the proposed method, the black line shows the ground truth, and the red points represent the results from a transfer operator-based approach. The plot demonstrates the accuracy of the proposed method in estimating the dynamics of the system, even with a biased potential, and its clear superiority over the transfer operator-based method.

This figure presents the results of applying the proposed method to the alanine dipeptide molecule. Panels (a) and (b) show the first and second learned eigenfunctions using a dataset with few transitions (Dataset 1), plotted against the dihedral angles ψ and φ. Panel (c) demonstrates the method’s ability to generalize well, showing the first eigenfunction applied to a dataset with many transitions (Dataset 2), also plotted against ψ and φ. Finally, panel (d) compares the first eigenfunction learned with the committor, a key quantity in molecular dynamics that represents the probability of transitioning between metastable states.

Full paper#