↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent (DP-SGD) is essential for training machine learning models while protecting user privacy. A core challenge is balancing privacy preservation and model accuracy. Existing methods, particularly Poisson subsampling, struggle with memory efficiency and tight privacy guarantees. The variable-sized minibatches in these methods pose practical problems when training on resource-constrained devices or handling datasets of massive size.

This research introduces a novel Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) accountant for DP-SGD using fixed-size minibatches with and without replacement. This approach provides tighter privacy guarantees by considering both add/remove and replace-one adjacency relationships. The authors demonstrate that fixed-size subsampling, particularly without replacement, often outperforms Poisson subsampling due to its constant memory usage and comparable privacy levels.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in differential privacy and machine learning. It offers tighter privacy guarantees for a widely-used deep learning training method, improving the efficiency and practicality of private AI development. The novel RDP accountant and analysis provides a valuable tool for the community, opening avenues for more efficient private AI model training. The work also highlights the memory advantages of fixed-size subsampling, impacting how future DP libraries are built.

Visual Insights#

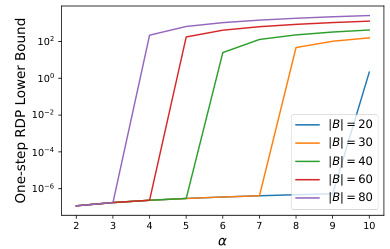

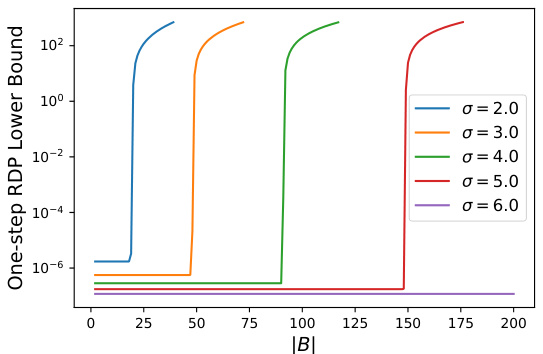

This figure shows the FSWR-RDP lower bounds as a function of α (alpha) for fixed values of σ (sigma) and q. The different lines represent different minibatch sizes |B|. It illustrates how, for small α, the lower bounds are approximately equal regardless of |B|, but beyond a critical threshold (which depends on |B|), there is a rapid increase in the lower bound. This indicates worse privacy guarantees for larger minibatch sizes.

In-depth insights#

RDP Accountant#

The concept of an “RDP Accountant” is central to achieving differential privacy in machine learning, particularly within the context of stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD). It’s a mechanism for tracking and bounding the cumulative privacy loss incurred during the iterative training process of a DP-SGD model. This is crucial because each gradient update step inherently leaks some information about the training data. The RDP accountant carefully quantifies this leakage using the concept of Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP), offering a more refined and composable approach compared to traditional (ε, δ)-DP. Different subsampling techniques, such as fixed-size or Poisson, impact the RDP calculation significantly; the paper focuses on developing tighter and more practical RDP accountants tailored to these distinct subsampling approaches. The tightness of these bounds is paramount for maximizing the utility of the DP-SGD algorithm while maintaining strong privacy guarantees. A key aspect discussed in the paper is the analytical derivation and empirical validation of these bounds, comparing them to existing methods and demonstrating improvements in accuracy and efficiency.

Fixed-Size DP-SGD#

Fixed-size differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) offers a compelling alternative to traditional variable-size minibatch approaches. Memory efficiency is a key advantage, as fixed-size minibatches eliminate the need for dynamic memory allocation during training, thus preventing potential out-of-memory errors. This is especially crucial when dealing with large datasets or resource-constrained devices. Furthermore, fixed-size subsampling simplifies the privacy accounting process, enabling tighter Rényi differential privacy (RDP) guarantees compared to prior methods. The research highlights how fixed-size subsampling, both with and without replacement, exhibits lower variance in practice, potentially leading to improved model training stability and accuracy. The paper presents a novel and holistic RDP accountant specifically for the fixed-size setting, enhancing the precision of privacy analysis in the context of DP-SGD. However, it is important to note that the advantages of fixed-size DP-SGD may be most pronounced in certain scenarios, specifically when the sampling probability is relatively low. Careful consideration of the specific application and its constraints is crucial when choosing between fixed-size and other subsampling strategies for DP-SGD.

Privacy Amplification#

Privacy amplification is a crucial concept in differential privacy (DP) that allows for the reduction of privacy loss when working with subsets of a dataset. The core idea is to enhance the privacy guarantees provided by a base mechanism (e.g., adding noise to a query’s result) by applying it only to a carefully selected sample of the data. This subsampling technique leverages the fact that an adversary is less likely to infer sensitive information about an individual if they only have access to a fraction of the data. The level of privacy amplification achieved depends on several factors, including the subsampling strategy (e.g., uniform sampling, Poisson subsampling), the size of the sample, and the properties of the base mechanism. Analyzing and quantifying this amplification are essential for providing rigorous privacy guarantees in DP applications. For instance, the privacy amplification afforded by Poisson subsampling is often studied through concentration inequalities and Rényi differential privacy, providing theoretical bounds on the privacy loss. Tighter bounds on privacy amplification lead to more efficient privacy-preserving algorithms, allowing for the use of less noise or larger datasets while maintaining the desired level of privacy.

Variance Reduction#

Analyzing variance reduction in the context of differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) reveals crucial insights into algorithm efficiency and privacy-utility trade-offs. Fixed-size subsampling, unlike Poisson subsampling, offers memory efficiency and consistent minibatch sizes, impacting gradient estimation and noise addition. The paper’s analytical and empirical findings highlight that fixed-size subsampling, especially without replacement, demonstrates lower variance in practice compared to Poisson subsampling. This variance reduction is particularly significant when the algorithm is far from its optimal solution (i.e., away from the minimum of the loss function). The reduced variance, coupled with tighter Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) guarantees, suggests a potential advantage for fixed-size methods in terms of both privacy and accuracy. However, the trade-off involves slightly higher epsilon values in some scenarios, prompting a careful consideration of privacy requirements alongside accuracy gains. Ultimately, the choice between Poisson and fixed-size subsampling depends on the specific application and a holistic evaluation of memory constraints, privacy needs, and the optimization landscape.

Memory Efficiency#

The research paper emphasizes memory efficiency as a crucial advantage of using fixed-size minibatches in differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) compared to the commonly used Poisson subsampling. Poisson subsampling, while offering privacy amplification benefits, suffers from variable-sized minibatches, leading to unpredictable memory usage and potential out-of-memory errors during training. In contrast, fixed-size minibatches guarantee constant memory usage, simplifying memory management and enhancing the stability and reliability of the training process, particularly beneficial for resource-constrained environments or large-scale deployments. The paper highlights that the constant memory footprint of fixed-size minibatches simplifies implementation and improves computational efficiency. This is a significant practical advantage, making DP-SGD with fixed-size minibatches more suitable for real-world applications where memory is a critical resource constraint. The authors also provide empirical evidence supporting their claims by comparing memory usage between fixed-size and Poisson subsampling during DP-SGD training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

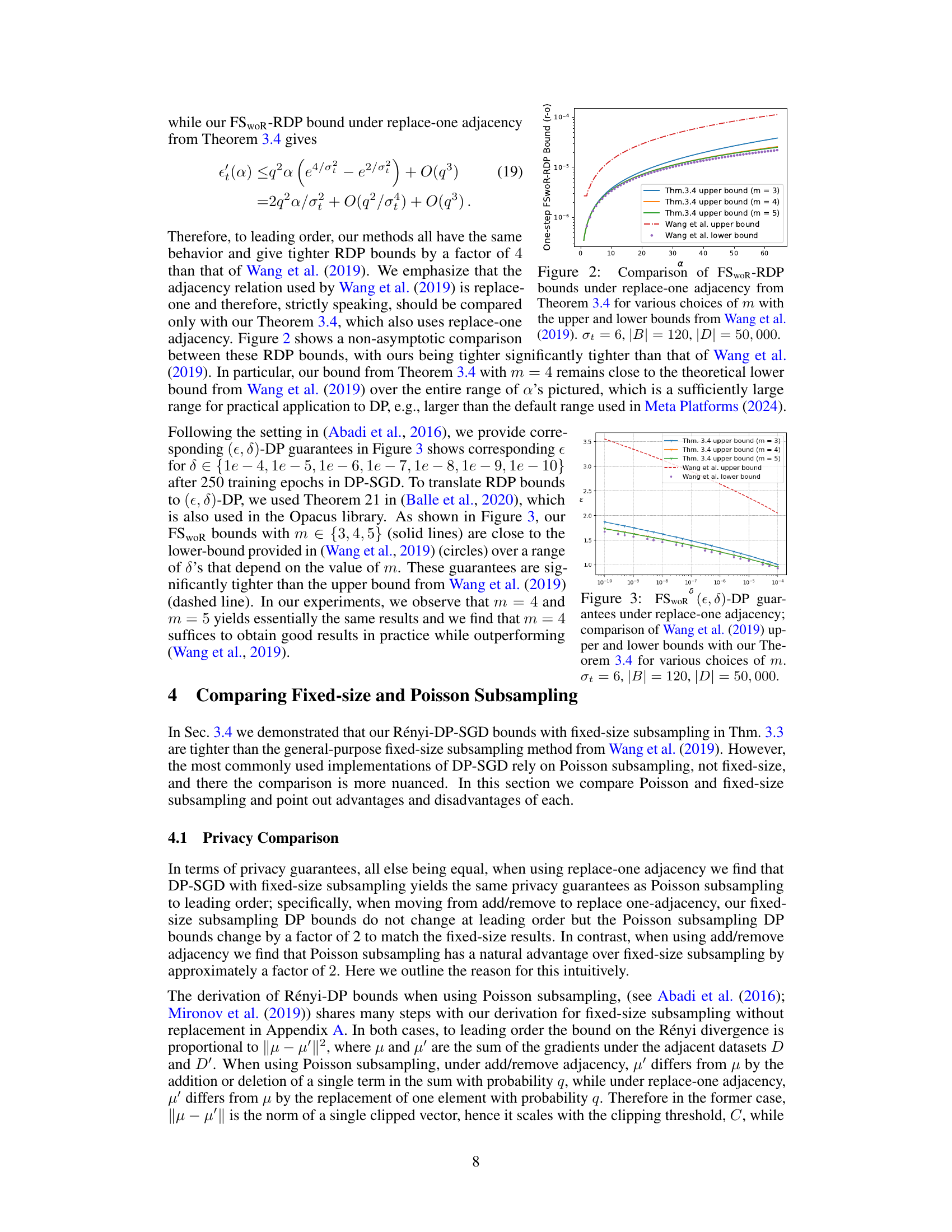

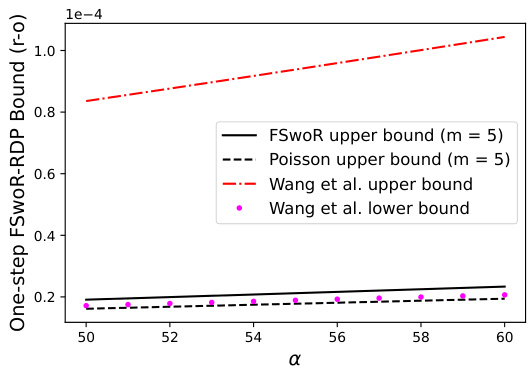

This figure compares the non-asymptotic upper and lower bounds for Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) using fixed-size subsampling without replacement (FSwoR) under replace-one adjacency. The plot shows the RDP bounds obtained using the method proposed in the paper (Theorem 3.4) for different values of the Taylor expansion order (m=3, 4, 5) against the upper and lower bounds given by Wang et al. (2019). The parameters used are σ = 6, minibatch size |B| = 120, and dataset size |D| = 50,000. The results demonstrate that the method presented in the paper provides tighter RDP bounds than the existing method.

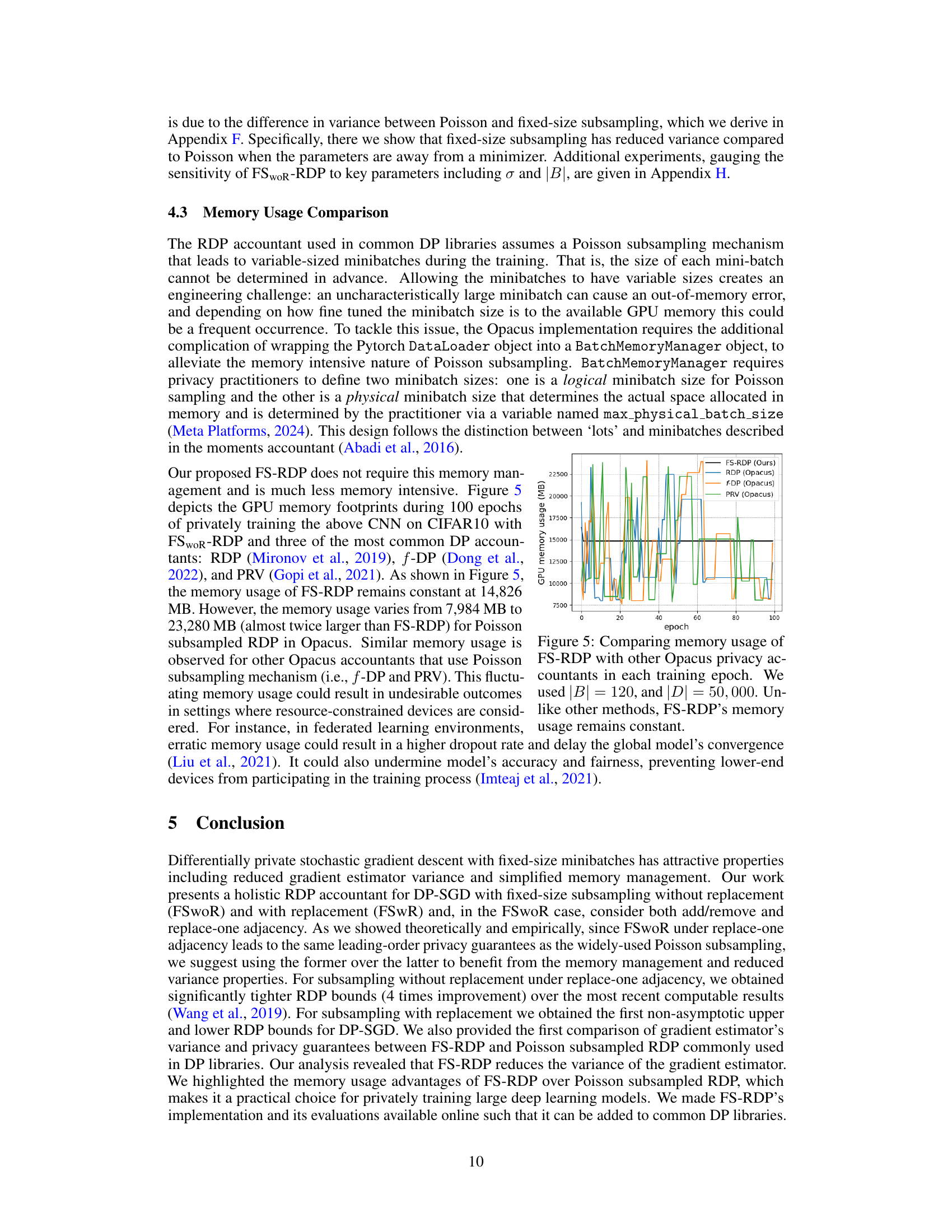

This figure compares the non-asymptotic upper and lower bounds on one-step Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) for fixed-size subsampling without replacement (FSwoR) under replace-one adjacency. The comparison is made against the bounds obtained using the method proposed in Wang et al. (2019). The plot shows that the RDP upper bounds from Theorem 3.4 (for m = 3, 4, and 5) are significantly tighter than those from Wang et al. (2019), particularly at higher values of α. The parameter values used are στ = 6, |B| = 120, and |D| = 50,000.

This figure compares the non-asymptotic upper and lower bounds for the Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) of the fixed-size subsampling without replacement (FSwoR) mechanism with the results from Wang et al. (2019). It demonstrates that the proposed FSwoR-RDP bounds are tighter than Wang et al. (2019), especially for larger values of α (the order of the Rényi divergence). The figure shows results for specific parameter values (στ = 6, |B| = 120, |D| = 50,000).

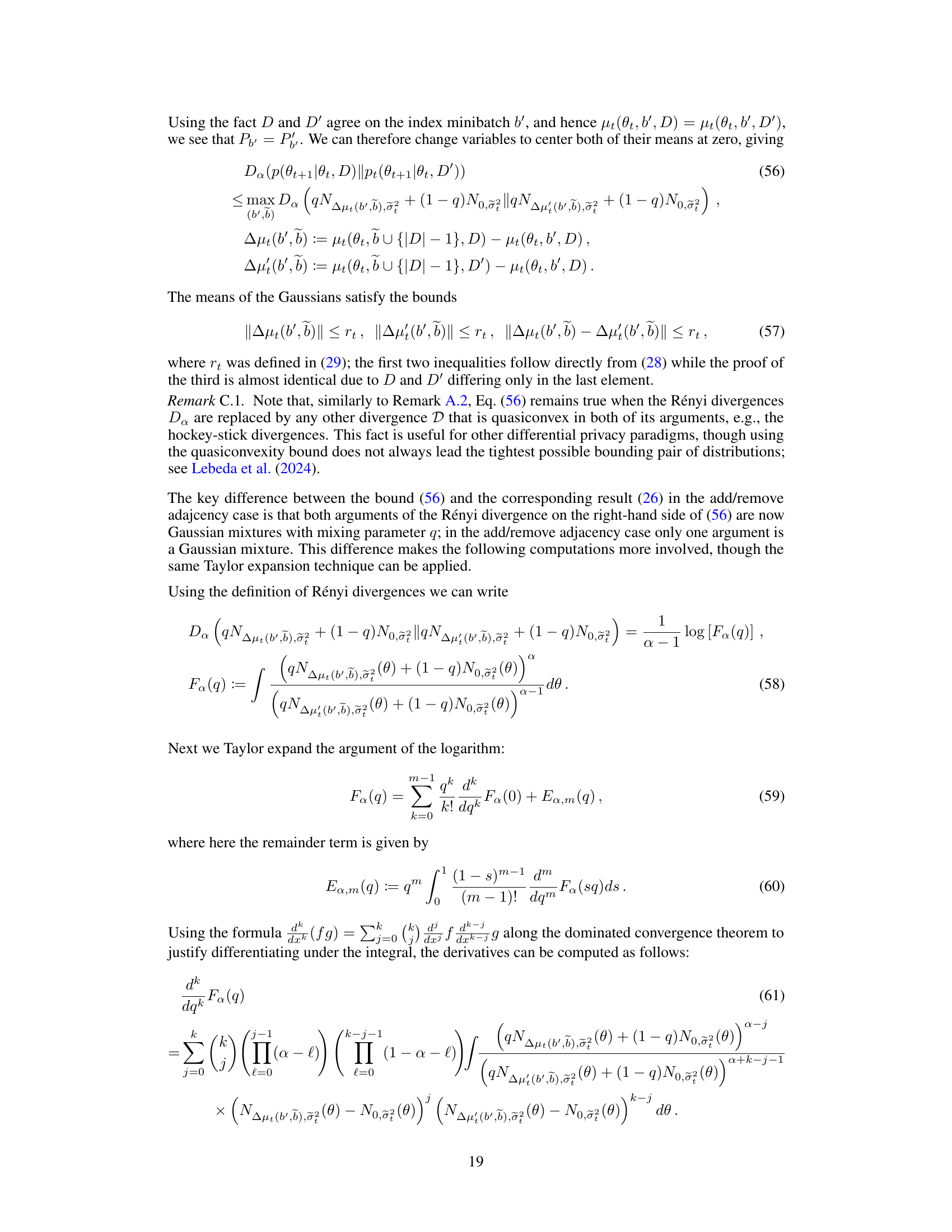

The figure compares the GPU memory usage of the proposed FS-RDP method with three other privacy accounting methods implemented in the Opacus library over 100 training epochs. It shows that the FS-RDP method maintains a relatively constant memory usage, unlike the other methods (RDP, f-DP, and PRV) which exhibit significant fluctuations in memory usage. This highlights the memory efficiency advantage of the FS-RDP approach.

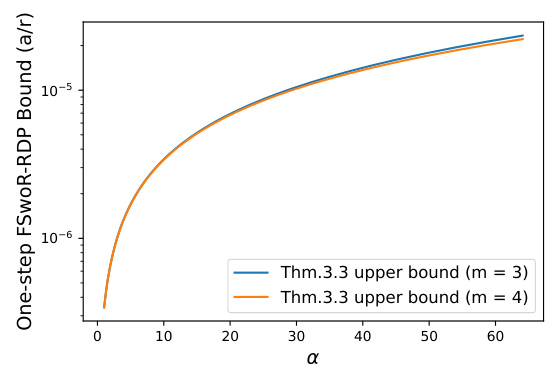

This figure plots the one-step FSwoR-RDP bound from Theorem 3.3 for different values of α (ranging from 0 to 60). The plot shows two lines, one for m=3 and another for m=4 in the Taylor expansion used to compute the bound. The plot demonstrates that even with a relatively small value of m (m=3), the bound is fairly accurate, and the improvement from increasing m to 4 is negligible. This suggests that m=3 is sufficient for practical applications.

The figure compares the upper bounds of one-step Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) for fixed-size subsampling without replacement (FSwoR) and Poisson subsampling under replace-one adjacency. It shows that the FSwoR upper bounds (from Theorem 3.4, with m=5) are tighter than the Poisson subsampling upper bounds (with m=5) and the upper and lower bounds from Wang et al. (2019). The plot highlights that, while the leading-order terms for FSwoR and Poisson subsampling are the same under replace-one adjacency, the higher-order terms in Poisson subsampling provide a slight privacy advantage.

This figure displays the FSWR-RDP lower bounds as a function of the minibatch size |B|, with the Rényi divergence order α fixed at 2 and the sampling probability q fixed at 0.001. Multiple lines are shown, each corresponding to a different value of the Gaussian noise standard deviation σ (2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0). The plot illustrates how the lower bound on the Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) changes with the minibatch size for different noise levels. It shows a phase transition for each value of σ, where the lower bound increases sharply after a certain minibatch size. This behavior implies a tradeoff between the privacy guarantees and the minibatch size when using fixed-size subsampling with replacement in differentially private stochastic gradient descent.

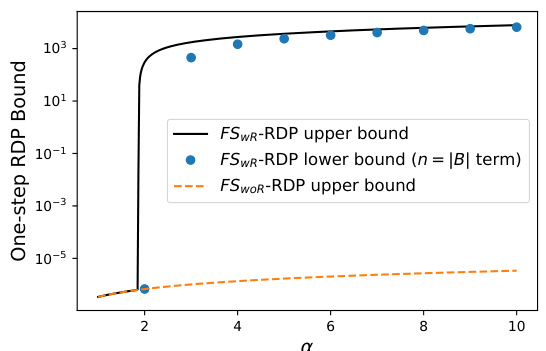

This figure compares the upper and lower bounds of Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) for fixed-size subsampling with replacement (FSwR) as a function of α (the order of the Rényi divergence). It also includes the upper bound for fixed-size subsampling without replacement (FSwR) for comparison. The plot shows that for small α, all three bounds are very similar, but as α increases, the FSWR upper and lower bounds diverge significantly, indicating a higher degree of privacy loss at larger values of α. The FSwR bounds are significantly tighter than the FSwOR bound.

The figure compares the privacy guarantees (ε, δ) obtained using the proposed FSWOR-RDP method against those obtained using the method proposed by Wang et al. and the commonly used Poisson subsampled RDP method available in the Opacus library. The comparison is performed on CIFAR10 dataset using a CNN model. The top panel shows the privacy guarantees (ε, δ) for the three methods while the bottom panel shows the testing accuracy of the three methods. The results demonstrate that the proposed FSWOR-RDP method yields tighter privacy guarantees compared to Wang et al. and achieves a slightly better testing accuracy than Poisson subsampled RDP.

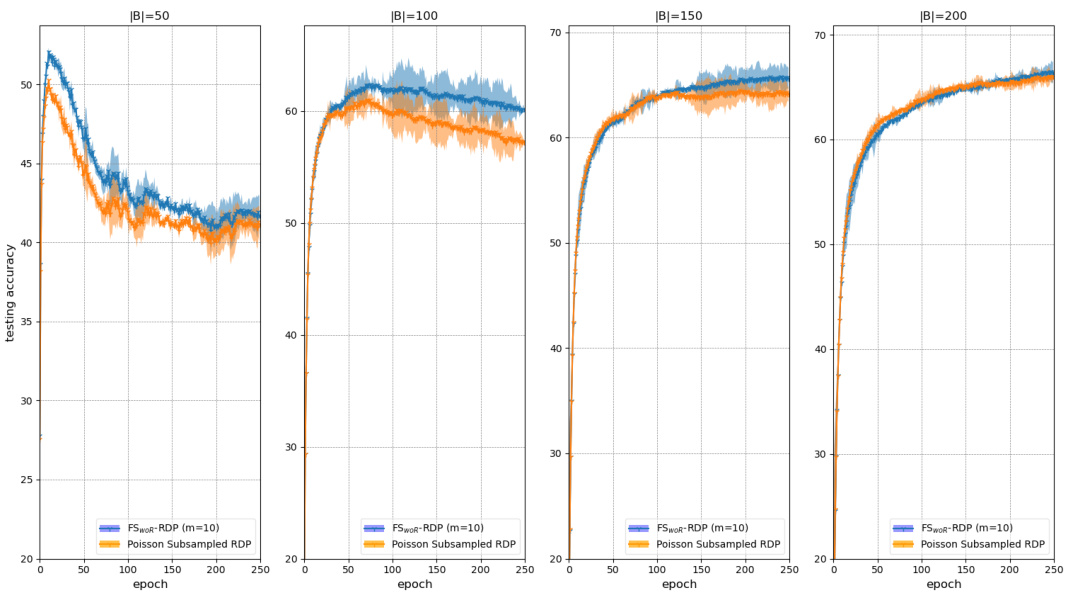

This figure compares the performance of fixed-size subsampling with Poisson subsampling using the same DP-SGD settings but varying values for σ (standard deviation of the noise) and |B| (batch size). The subplots (a) show performance (testing accuracy) across different values of σ, while the subplots (b) show performance across different values of |B|. The results show that the fixed-size method performs comparably or slightly better than the Poisson subsampling method, and that it’s not particularly sensitive to the values of σ and |B|.

Full paper#