↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) often struggle with complex reasoning tasks. Current solutions like advanced prompting techniques require substantial, high-quality data for effective fine-tuning, which is often limited. Self-correction and self-learning approaches are emerging as alternatives, but their effectiveness remains questionable, especially in complex scenarios. This is particularly challenging because assessing the quality of an LLM’s response, especially in tasks requiring intricate reasoning, remains a difficult problem.

This paper introduces ALPHALLM, a novel framework for LLM self-improvement that integrates Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) with LLMs. ALPHALLM addresses data scarcity by generating synthetic prompts; enhances search efficiency through a tailored MCTS approach, ηMCTS, and provides precise feedback using a trio of critic models. Experiments in mathematical reasoning demonstrate ALPHALLM’s significant performance improvement over base LLMs without additional annotations, showcasing the potential of self-improvement in LLMs and offering a promising solution to the challenges of data scarcity and complex reasoning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents ALPHALLM, a novel framework that significantly improves LLMs’ performance in complex reasoning tasks without requiring additional annotations. This addresses a key challenge in the field and opens avenues for more efficient LLM training and development. The integration of MCTS with LLMs offers a new paradigm for self-improvement, potentially impacting various applications needing complex reasoning.

Visual Insights#

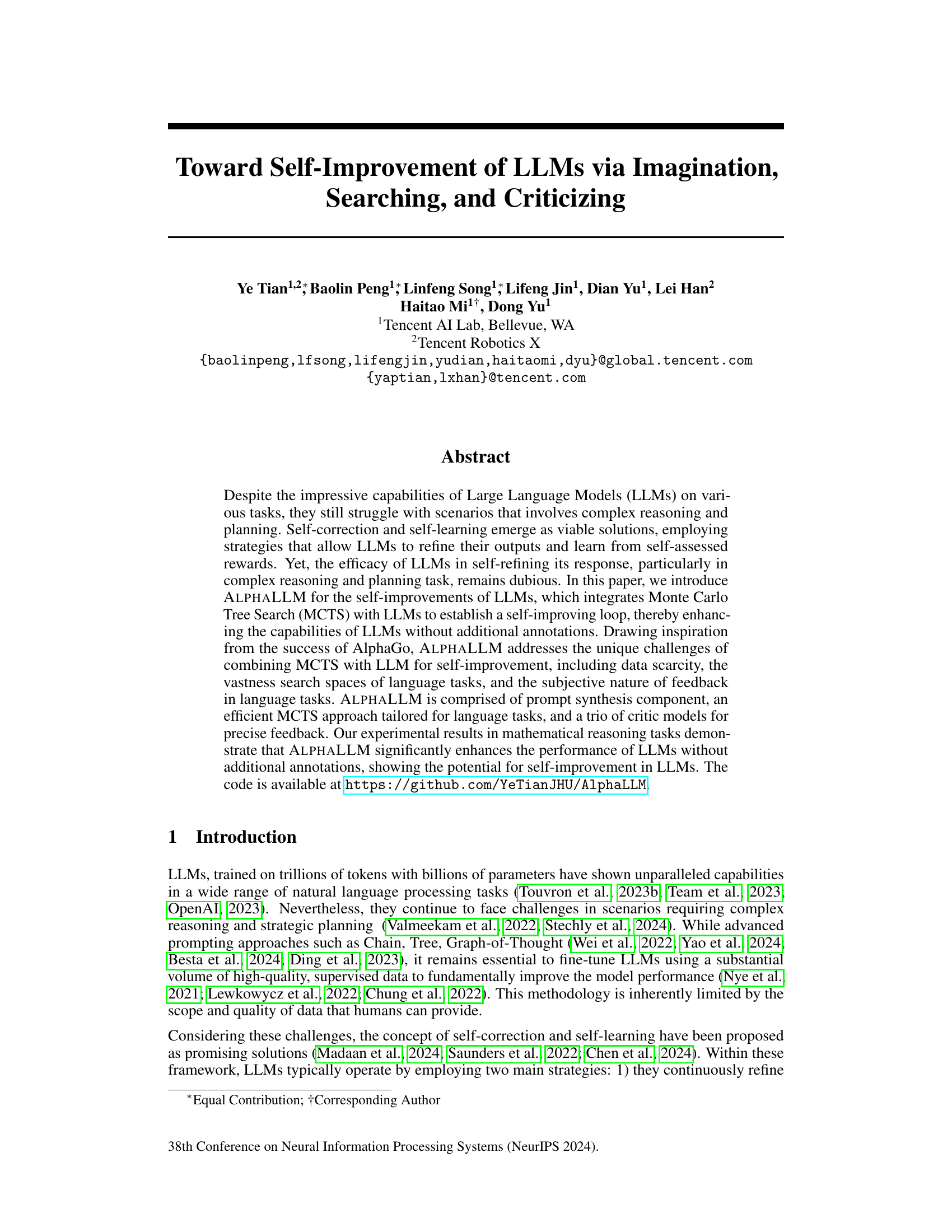

This figure illustrates the ALPHALLM self-improvement loop, which consists of three main components: Imagination, Searching, and Criticizing. The Imagination component generates new prompts by leveraging existing data and a language model (LLM). The Searching component utilizes Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to explore the vast response space, guided by the Criticizing component. The Criticizing component consists of three critic models (Value Function, Step Reward, Outcome Reward) providing feedback to improve the policy. The improved policy is then used to refine the LLM, creating a continuous self-improvement loop.

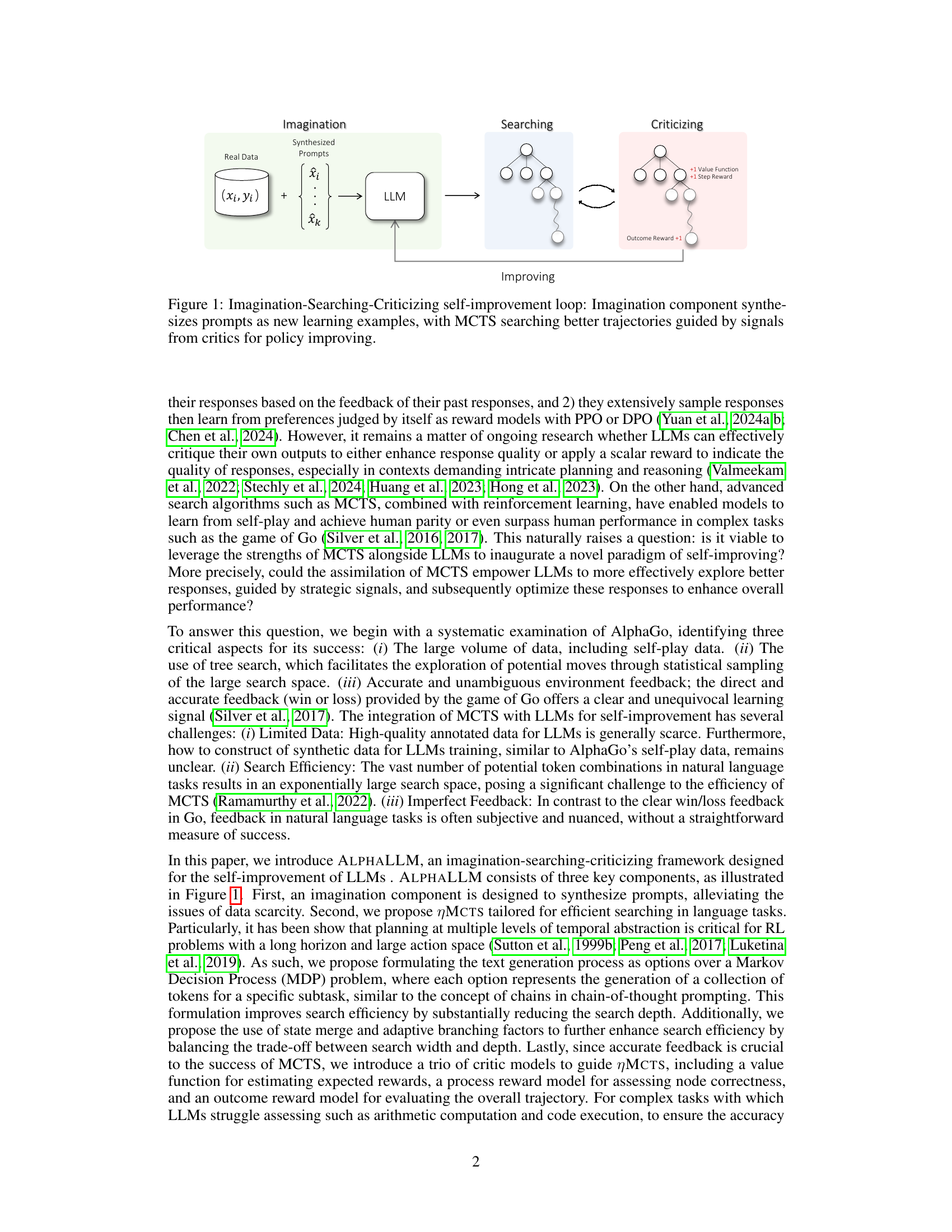

This table compares three different levels of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): token-level, sentence-level, and option-level. It shows how the search node is defined in each approach (a single token, a whole sentence, or a sequence of tokens), and what constitutes a termination condition for the search at that level. The option-level is the most flexible, allowing for sequences of varying lengths and providing more control over the search process.

In-depth insights#

LLM Self-Refining#

LLM self-refinement represents a crucial advancement in large language model (LLM) capabilities. It moves beyond passive generation by enabling LLMs to critically assess and improve their own outputs. This iterative process, often involving internal feedback mechanisms or external evaluation tools, allows for the refinement of responses, leading to higher accuracy and coherence. Effective self-refinement strategies are key to overcoming limitations like hallucinations and inconsistencies. The process can involve various techniques such as reinforcement learning, where the LLM learns from rewards based on the quality of its outputs, or Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), which allows for exploration of a wider range of possible responses before selection. Data efficiency is a significant consideration in self-refinement, as creating large labeled datasets for training can be costly and time-consuming. Methods focusing on generating synthetic data or leveraging unlabeled data to train these mechanisms are essential. The ability of an LLM to perform self-refinement is a strong indicator of its overall maturity and potential.

AlphaLLM: Design#

The design of AlphaLLM centers around a self-improving loop enabled by integrating a large language model (LLM) with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). Imagination is key; AlphaLLM synthesizes new training prompts, addressing data scarcity common in LLM training. These prompts are then fed into a customized ηMCTS algorithm designed for efficient search within the vast space of language tasks. This algorithm utilizes option-level search, improving efficiency over token or sentence-level approaches. Guiding the search is a trio of critic models: a value function, a process reward model (PRM), and an outcome reward model (ORM), providing precise feedback on response quality. The dynamic combination of these critics ensures accuracy in evaluating options, particularly for complex tasks. Finally, trajectories with high rewards identified by ηMCTS are used to fine-tune the LLM, creating the self-improvement cycle. This design cleverly addresses inherent LLM challenges by incorporating advanced search techniques and providing nuanced, targeted feedback, ultimately boosting performance.

ηMCTS Search#

The core of the proposed self-improvement framework for LLMs centers around a novel Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, termed ηMCTS. This isn’t a standard MCTS; ηMCTS is designed to overcome the challenges posed by the vast search space inherent in natural language processing. Instead of exploring individual tokens, ηMCTS employs an option-level search. This means the algorithm searches through sequences of tokens (options), representing higher-level actions like generating sentences or clauses. This significantly reduces the search complexity, allowing for more efficient exploration of the solution space. Further enhancing efficiency is ηMCTS’s adaptive branching factor, which dynamically adjusts the number of child nodes explored at each step based on the estimated value of the options. The algorithm is guided by a trio of critic models—value, process, and outcome rewards—to provide precise feedback, mitigating the subjective nature of language task evaluation. The combination of option-level search, adaptive branching, and multi-faceted criticism makes ηMCTS uniquely suited for the self-improvement of LLMs.

Critic Models#

The paper introduces three critic models to provide precise feedback guiding the search process: a value function estimating expected rewards, a process reward model (PRM) assessing node correctness during the search, and an outcome reward model (ORM) evaluating the overall trajectory’s alignment with the desired goal. The value function learns from trajectory returns, PRM provides immediate feedback for action choices, and ORM evaluates the entire trajectory. The combination of these critics offers a robust assessment, compensating for the subjective nature of language feedback, particularly useful in complex tasks where simple reward signals are insufficient. The critics’ dynamic decisions on using tools further enhances accuracy, demonstrating the importance of multifaceted feedback in guiding the search and improving LLM performance.

Future: LLM Evol.#

The heading ‘Future: LLM Evol.’ suggests a forward-looking perspective on the evolution of large language models (LLMs). A thoughtful exploration would delve into potential advancements, such as improved efficiency and scalability, enabling LLMs to handle increasingly complex tasks with reduced computational resources. Another key area would be enhanced reasoning and problem-solving capabilities, moving beyond pattern recognition towards true understanding and contextual awareness. Increased robustness and reliability are crucial, mitigating issues like biases, hallucinations, and vulnerabilities to adversarial attacks. The exploration of new architectures and training methodologies would also be essential, perhaps focusing on techniques that mimic aspects of human cognition like memory and learning. Ultimately, anticipating the future of LLMs necessitates addressing ethical considerations, ensuring responsible development and deployment to prevent misuse and mitigate societal risks. The integration of LLMs with other technologies, such as robotics and virtual reality, presents exciting opportunities but also raises challenges that warrant careful investigation. Ethical frameworks and regulatory guidelines will be vital to guide the evolution of LLMs in a manner that benefits humanity while minimizing potential harms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the empirical analysis on the GSM8K dataset for different self-improving data collection methods and various numbers of iterations. The models are evaluated using greedy decoding, ηMCTS with small rollout numbers and ηMCTS with large rollout numbers. The results illustrate the performance improvements achieved through iterative self-improvement using different methods and highlight the effectiveness of ηMCTS for improving the model’s accuracy.

The figure illustrates the ALPHALLM self-improvement loop. It starts with an Imagination component that generates new prompts as training examples. These prompts are fed into an LLM, which then uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to explore better response trajectories. The MCTS process is guided by three critic models (Value, PRM, ORM) that provide feedback on the quality of the generated responses. This feedback allows the LLM to refine its responses, improving its performance iteratively. The loop continues, with improved responses feeding back into the generation of new prompts and further refinements.

More on tables

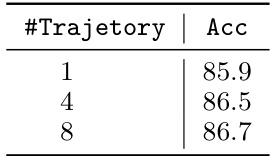

This table compares the performance of ALPHALLM with various other large language models (LLMs) on two mathematical reasoning datasets: GSM8K and MATH. It shows the accuracy of each model, indicating how well it solved the problems in each dataset. The table also specifies whether the models were trained using rationales (RN), final answers (FA), or synthetic prompts (SYN), and how many annotations were used in training (indicated by #Annotation). The key takeaway is that ALPHALLM, especially when using the MCTS search algorithm, achieves comparable performance to state-of-the-art models like GPT-4, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving LLMs through self-improvement.

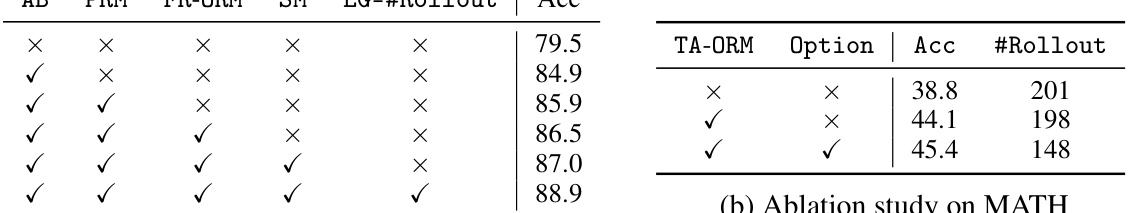

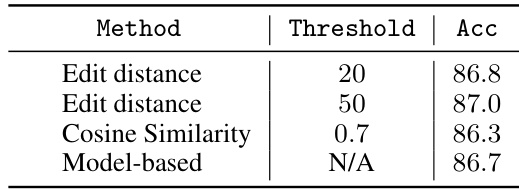

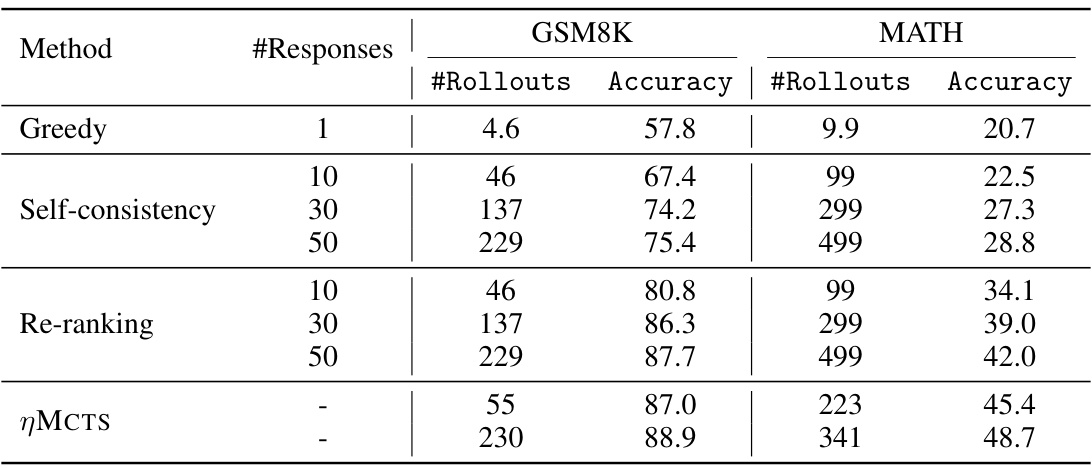

This table presents the ablation study results on the GSM8K and MATH datasets. It shows how the performance of the ALPHALLM model changes when different components of the MCTS algorithm (adaptive branching, PRM, fast-rollout with ORM, state merge, large number of rollouts) and the option-level formulation are removed. The results are presented in terms of accuracy and the number of rollouts required.

This table presents ablation studies on the GSM8K and MATH datasets. It shows the impact of different components and design choices of the proposed ηMCTS algorithm on the accuracy. (a) shows ablation results on GSM8K, evaluating the effects of using adaptive branching factors, the process reward model (PRM), the outcome reward model (ORM) with fast rollout, and state merge strategies. (b) focuses on the MATH dataset, examining the impact of tool-augmented ORM and option-level formulation.

This table presents ablation studies performed on the GSM8K and MATH datasets to evaluate the impact of different components of the MCTS algorithm, including adaptive branching, PRM (process reward model), ORM (outcome reward model) with fast rollout, state merge, and varying numbers of rollouts. The (a) part shows results on GSM8K, and (b) part focuses on MATH, examining the effects of tool-augmented ORM and the option-level formulation.

This table presents the hyperparameters used in the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. The hyperparameters are categorized into two groups: exploration vs. exploitation and adaptive branching. Exploration/exploitation is controlled by the parameters ‘c’ and ‘α’, with higher values generally leading to more exploration and lower values favoring exploitation. Adaptive branching controls the maximum and minimum number of child nodes that can be explored at each level of the search tree (‘cmax’ and ‘cmin’). The values differ for the root node (t=0) versus other nodes (t>0). The table also specifies parameter values used for experiments performed on two datasets, GSM8K and MATH, categorized further into ‘small’ and ’large’ rollout experiments. ‘Small’ likely denotes experiments with a smaller number of simulations, whereas ’large’ represents experiments with a more extensive number of simulations during the MCTS process.

This table presents the ablation study result of using different fast rollout models for the GSM8K dataset. It compares the performance (accuracy and speed) of using Abel-002-7B and Llama-2-70B as the fast rollout models in the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. The results show that while Llama-2-70B achieves slightly higher accuracy, Abel-002-7B is significantly faster.

This table compares the performance of different models on the GSM8K and MATH datasets. It shows the accuracy achieved by various methods (including ALPHALLM with different configurations) and indicates the amount of labeled data used for training. The table highlights the impact of using MCTS and the self-improvement loop on model performance, particularly emphasizing the use of synthetic data generated by the model itself.

This table compares the performance of ALPHALLM against other LLMs on two mathematical reasoning datasets: GSM8K and MATH. It shows the accuracy of various models, indicating the amount of labeled data used for training (annotations: rationales (RN), final answers (FA), or synthetic data (SYN) generated using Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)).

This table presents the performance comparison of the Value Function and PRM models on the GSM8K test set. The performance is evaluated using three metrics: precision, recall, and expected calibration error (ECE). The Value Function model shows higher precision and better calibration, while the PRM model achieves higher recall. This highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each model, indicating that they might be complementary for use in a combined system.

Full paper#