↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current text-to-image (T2I) models often struggle with accurately binding semantically related objects or attributes in generated images, a problem known as semantic binding. Existing solutions involve complex fine-tuning or require user input, hindering efficiency and usability. This paper focuses on this issue, categorizing it into attribute binding (associating objects with attributes) and object binding (linking objects to sub-objects).

This research paper introduces Token Merging (ToMe), a novel training-free method that enhances semantic binding by merging relevant tokens into a single composite token. This approach ensures that objects, attributes, and sub-objects share the same cross-attention map, improving alignment. ToMe incorporates auxiliary losses (entropy and semantic binding) to further refine generation in early stages. Extensive experiments demonstrate ToMe’s superior performance over existing methods on benchmark datasets, particularly in complex scenarios, showcasing its effectiveness and user-friendliness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel training-free method, ToMe, to significantly improve semantic binding in text-to-image synthesis. This addresses a critical limitation of current models and opens avenues for more robust and user-friendly image generation, impacting various applications that rely on accurate image-text alignment. Its training-free nature makes it readily adaptable to existing models.

Visual Insights#

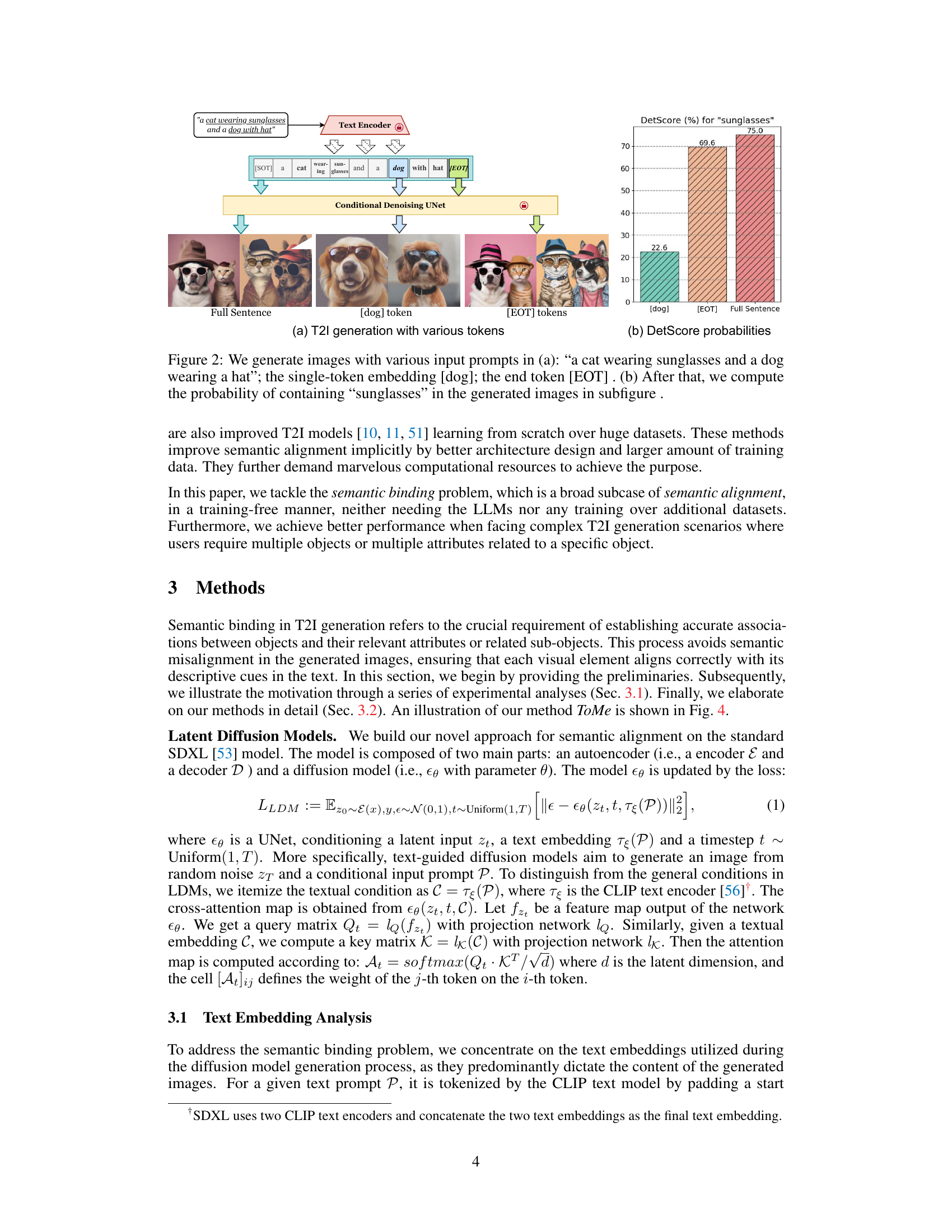

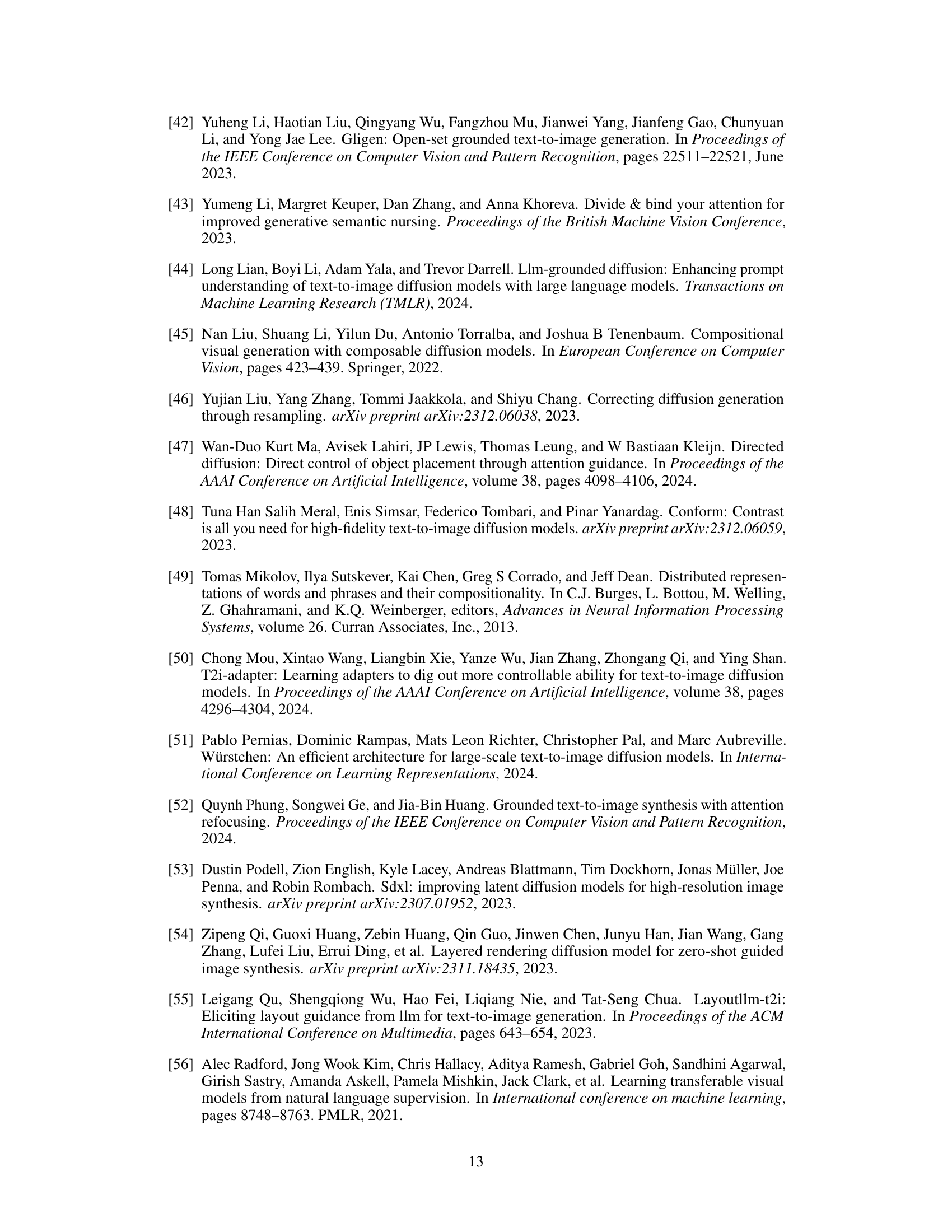

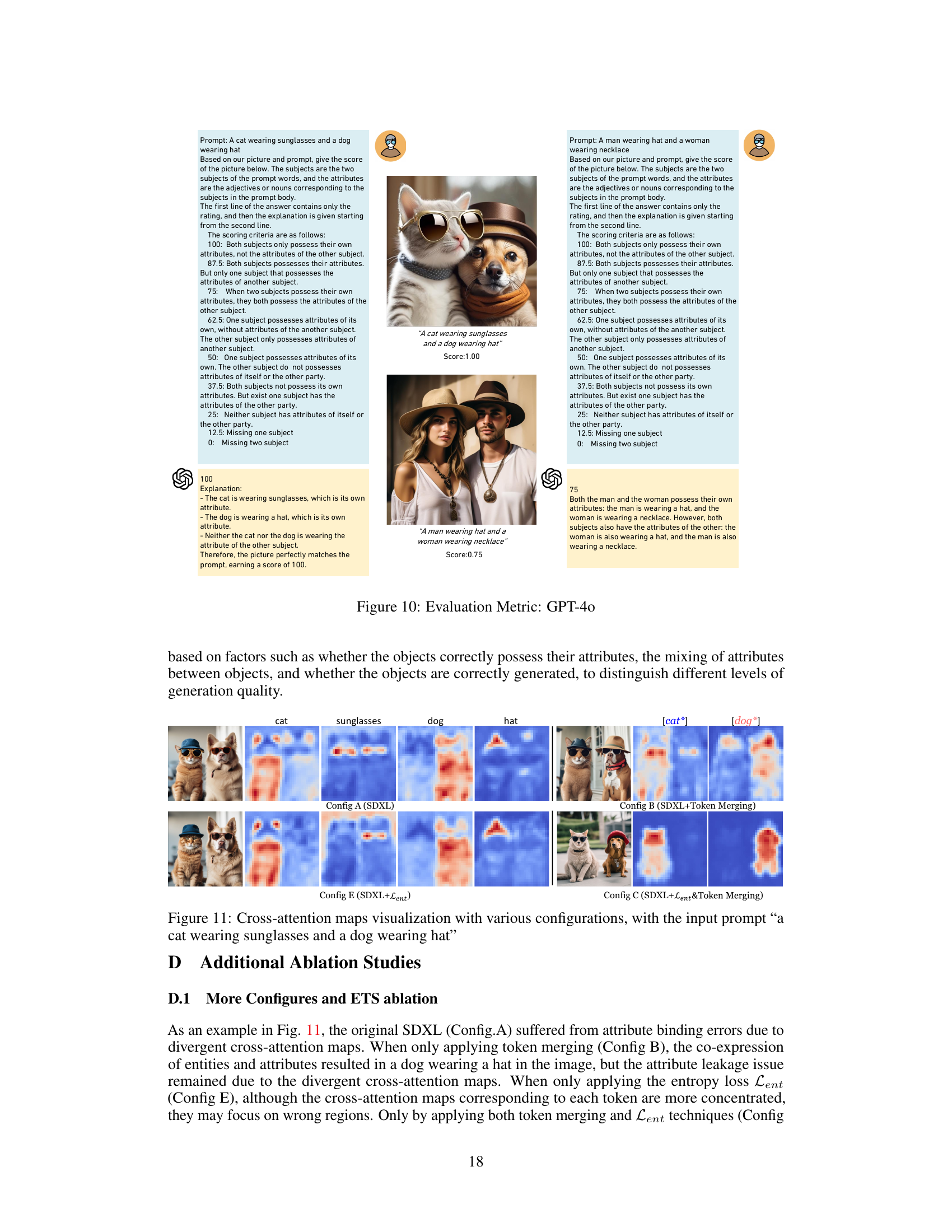

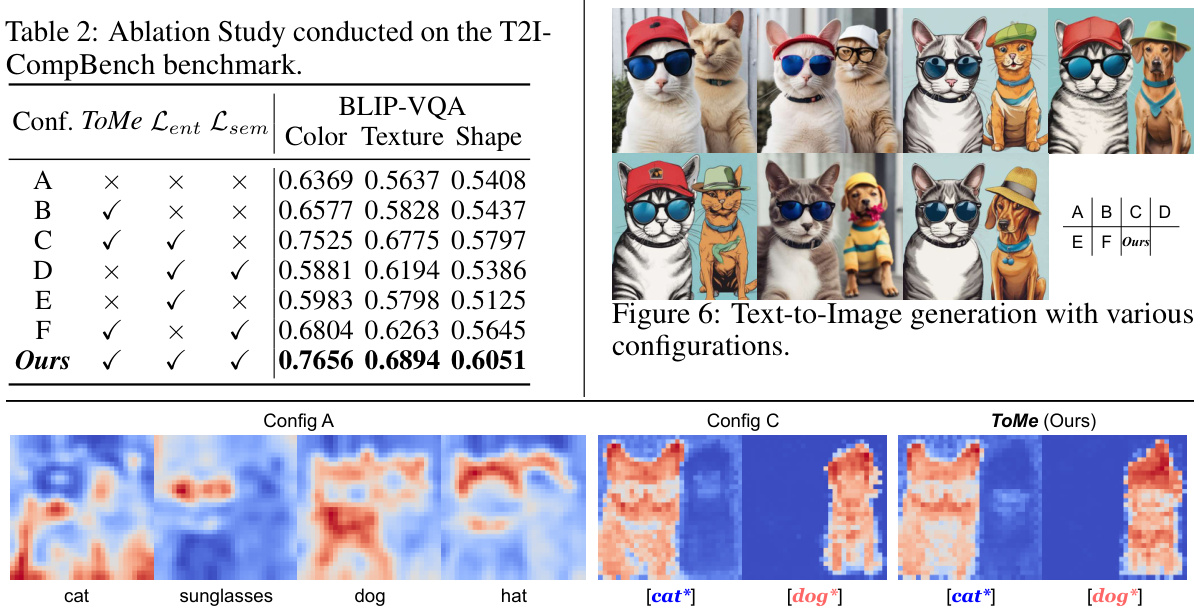

This figure shows the results of several state-of-the-art text-to-image models on prompts containing two subjects with related attributes. The models struggle to correctly associate the attributes (hats and sunglasses) with the intended subjects (dog and cat). The authors’ proposed method, ToMe, is presented as a solution to this ‘semantic binding’ problem.

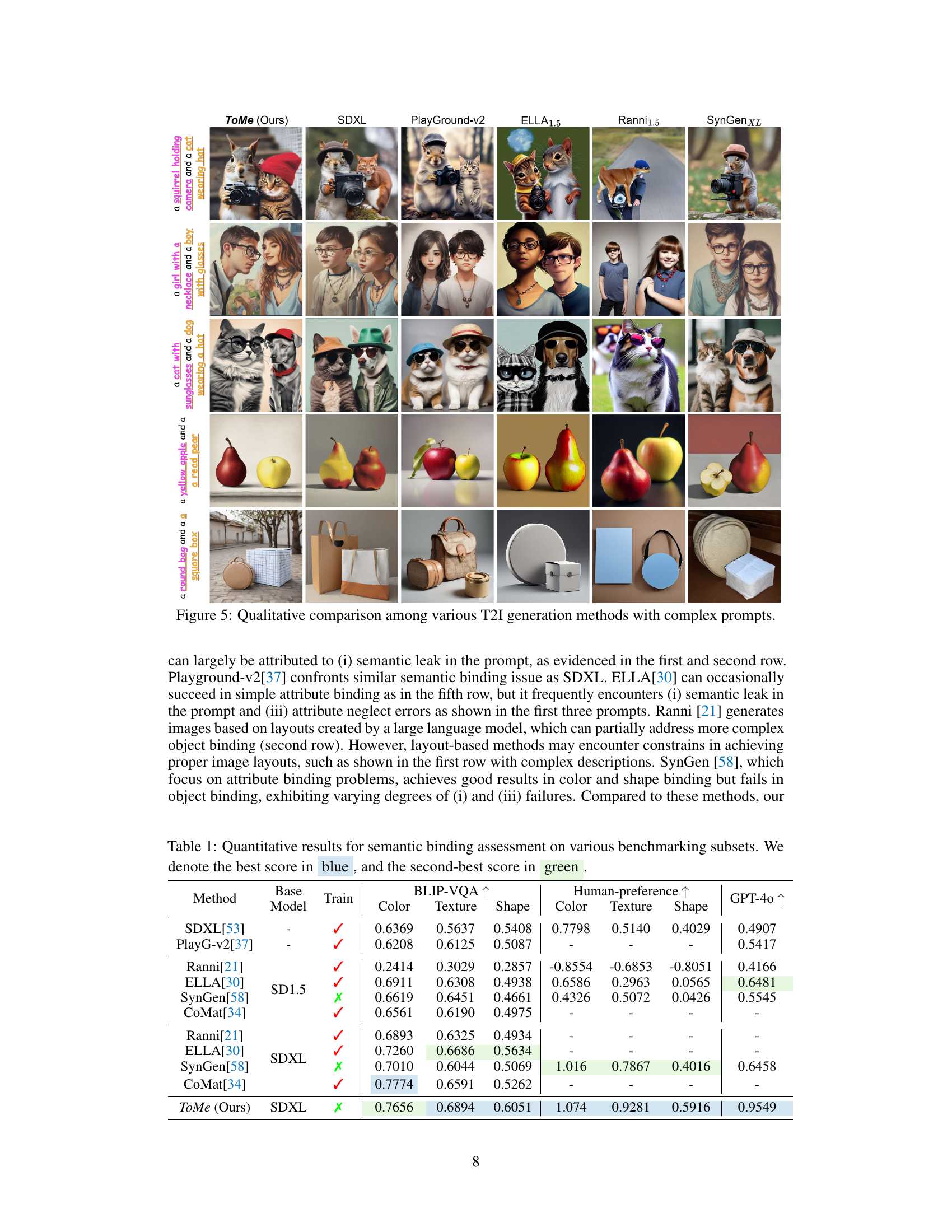

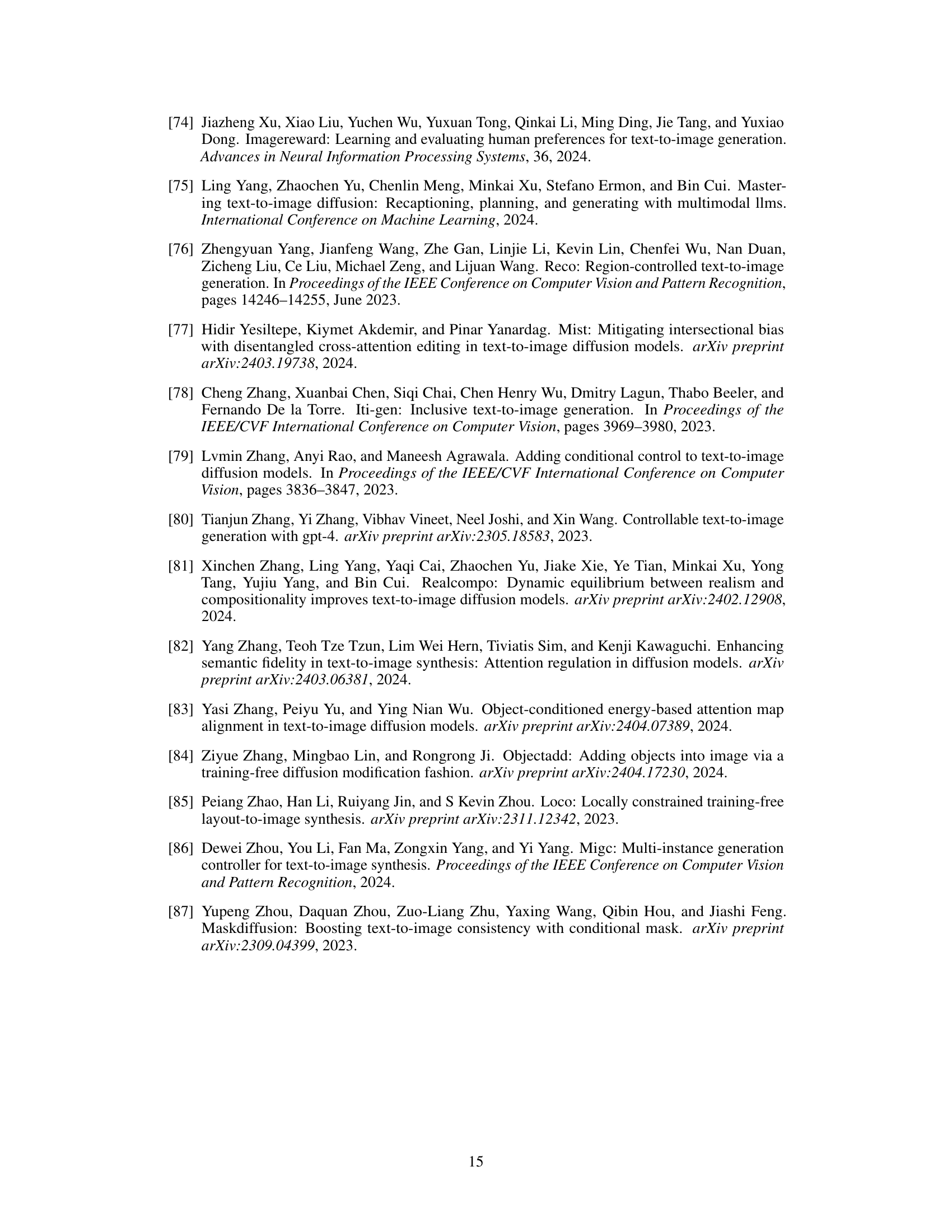

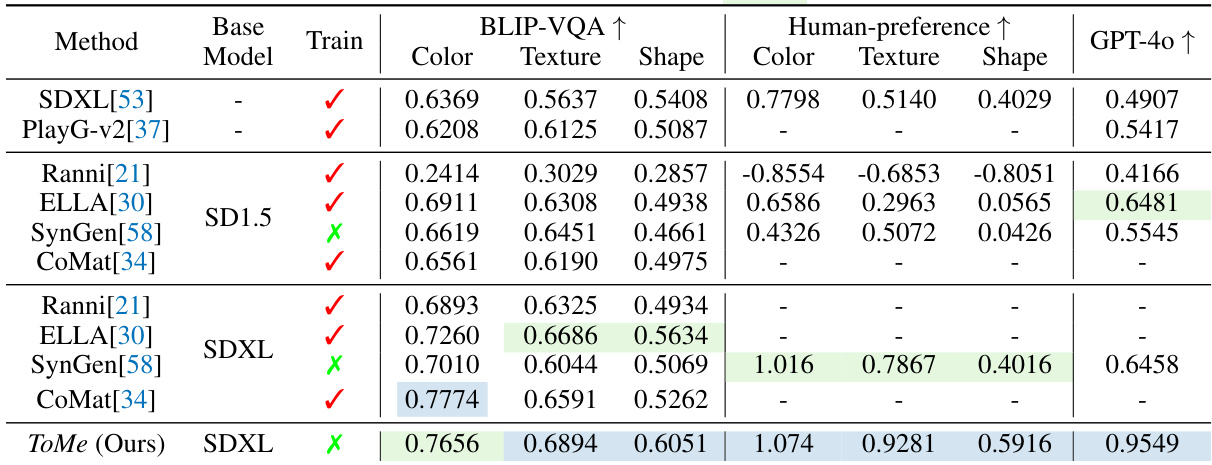

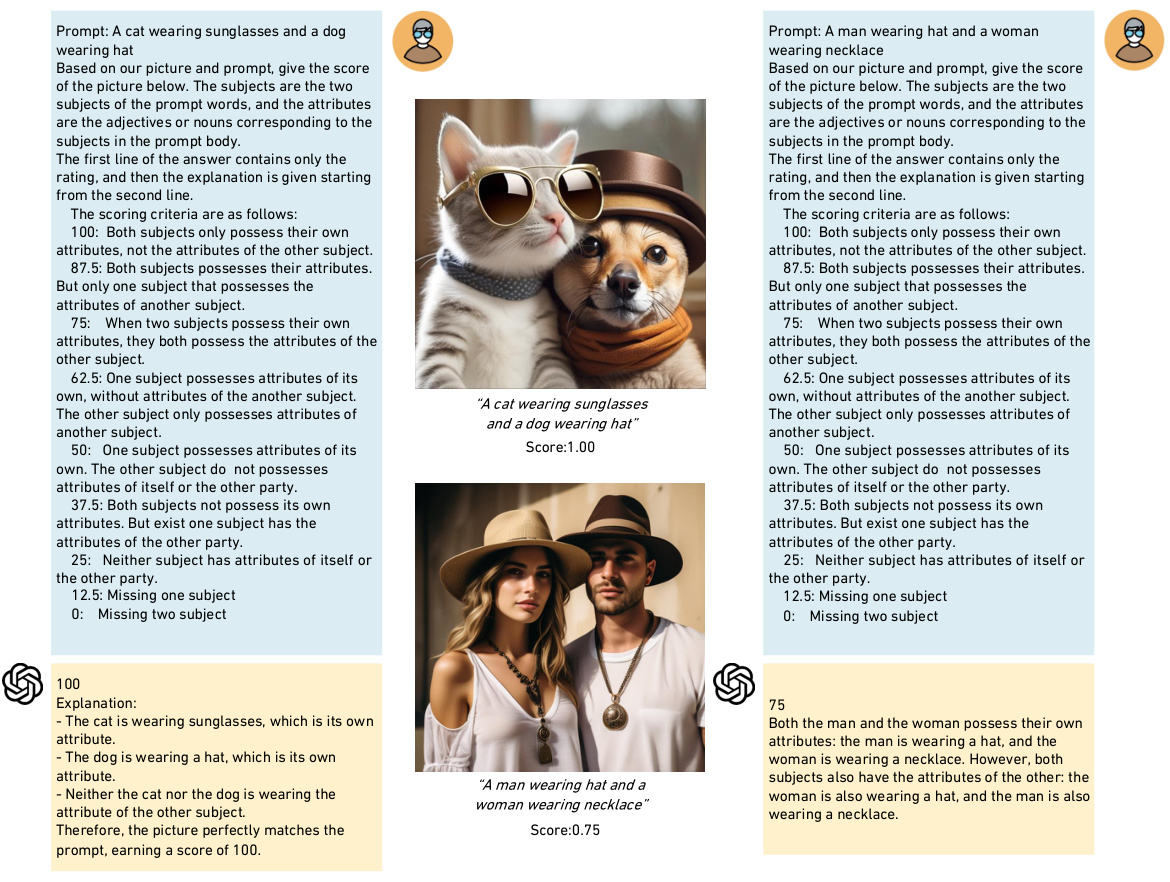

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for semantic binding assessment. It evaluates methods across three attribute subsets (color, texture, shape) using the BLIP-VQA metric and human preference scores (using ImageReward). Additionally, it includes GPT-40 scores, evaluating performance on a new object binding benchmark. The best and second-best scores are highlighted for each attribute and metric.

In-depth insights#

Semantic Binding#

Semantic binding in text-to-image synthesis refers to the challenge of accurately associating objects and their attributes within generated images. Inaccurate binding leads to images that don’t reflect the intended meaning of the text prompt. Existing methods often involve complex fine-tuning of large models or require user input to specify layouts, which is undesirable for ease of use. A key insight is that effective binding is closely linked to the alignment of attention mechanisms within the model. This is because attention determines how the model maps textual descriptions onto the generated visual elements. Approaches focusing on improving attention alignment and methods for explicitly linking tokens representing objects and their attributes are crucial for achieving strong performance in semantic binding. The development of training-free approaches is vital for overcoming the limitations of computationally intensive fine-tuning, increasing accessibility and practicality of the technology.

ToMe: Token Merge#

The proposed method, “ToMe: Token Merge,” addresses the challenge of semantic binding in text-to-image synthesis. It tackles the issue of T2I models failing to accurately link objects and their attributes or related sub-objects within a prompt by aggregating relevant tokens into composite tokens. This innovative approach ensures that objects, attributes, and sub-objects share the same cross-attention map, improving semantic alignment. Further enhancements include end-token substitution to mitigate ambiguity and auxiliary losses (entropy and semantic binding) to refine the composite tokens during initial generation stages. The core idea of ToMe leverages the additive property of text embeddings to create meaningful composite representations, demonstrating a unique and effective training-free approach to enhance semantic binding in complex scenarios where multiple objects and attributes are involved.

Loss Functions#

Loss functions are crucial in training deep learning models, particularly in text-to-image synthesis. A well-designed loss function guides the model to learn the desired relationships between text and image. Common choices include pixel-wise losses like MSE or L1, which focus on minimizing the difference between generated and target images. However, these often struggle with perceptual quality. Perceptual losses, using features from pretrained networks like VGG or ResNet, are frequently used to better capture high-level image similarity. These aim to bridge the semantic gap between low-level pixel values and human perception. Additionally, adversarial losses, employed in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), involve a discriminator network to assess the realism of the generated images, thereby improving the overall quality and coherence. The effectiveness of different loss functions depends heavily on factors like dataset specifics, model architecture, and desired output characteristics. Carefully balancing multiple loss functions and hyperparameter tuning is essential to achieve optimal performance in text-to-image generation. Finally, the choice of loss function significantly impacts computational efficiency, potentially influencing the trade-off between model accuracy and training time.

Experiment Results#

The section on “Experiment Results” would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method. It should begin by clearly stating the chosen metrics and benchmarks. Quantitative results should be presented, detailing the performance of the proposed method against baselines on various datasets. Key metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score (if applicable) must be reported with statistical significance, including error bars or p-values. The discussion should go beyond simple numerical comparisons. Qualitative analyses might involve visualizations, case studies, or detailed error analyses to provide deeper insights into the method’s strengths and weaknesses. For instance, specific examples of successful and failed cases could be analyzed to understand why the method performs better in some situations than others. Finally, the analysis should address the limitations observed during experimentation and discuss how these limitations might be addressed in future work. The overall aim is to provide readers with a well-rounded understanding of the method’s capabilities and limitations, enabling a fair assessment of its contribution to the field.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending ToMe’s capabilities to handle more complex scenarios involving intricate object relationships and numerous attributes presents a significant challenge. Investigating advanced token aggregation techniques beyond simple summation to better capture nuanced semantic relationships would be valuable. Developing a more robust method for handling ambiguities and inconsistencies in text prompts is crucial, as this remains a significant limitation for current text-to-image models. Furthermore, investigating the potential of ToMe in conjunction with other advanced techniques, such as prompt engineering or fine-tuning strategies, may yield synergistic improvements in image generation fidelity and semantic alignment. Finally, evaluating the generalizability of ToMe to other text-to-image models and modalities, such as video or 3D generation, would significantly expand its applicability and impact within the broader field of computer vision.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the results of generating images with different input prompts. (a) shows the images generated when using three different prompts: the full sentence, the [dog] token only, and the [EOT] token only. This illustrates how different parts of the prompt influence the generated image and the impact of the end-of-text token. (b) shows a bar chart visualizing the detection score probabilities of ‘sunglasses’ within the generated images. The results show that using the full sentence achieves the highest detection score. This indicates that the full sentence provides the most complete information, leading to better object association in the generated images.

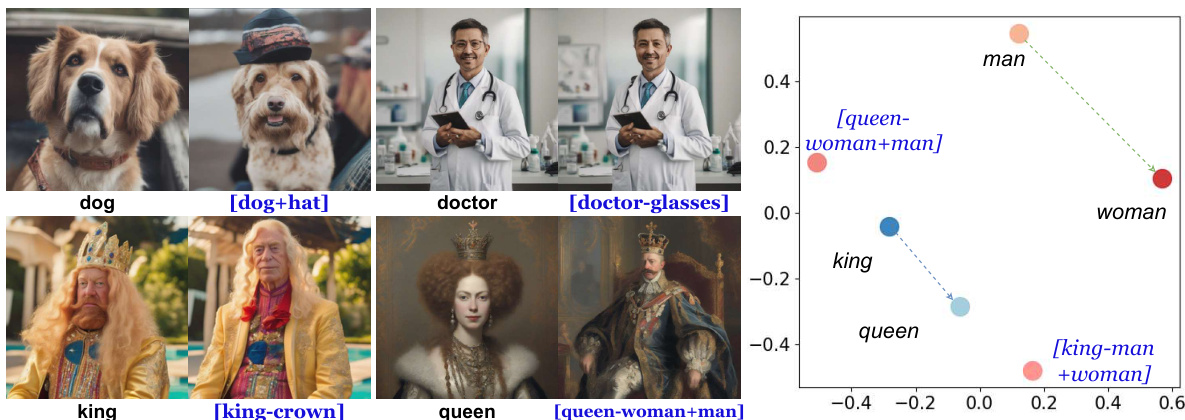

This figure demonstrates the semantic additivity property of CLIP text embeddings. Part (a) shows image generations using prompts combining object and attribute tokens, illustrating how adding tokens for attributes results in the expected visual changes to the generated image. Part (b) is a PCA plot showing the vector representations of different text embeddings, highlighting the linear relationship between embeddings of words and their combinations, visually supporting the claim of semantic additivity.

This figure illustrates the ToMe (Token Merging) framework, which is a two-part process. The first part involves token merging and end token substitution. This merges relevant tokens (e.g., object and attributes) into a single composite token to ensure that all related information shares the same cross-attention map, improving semantic alignment. The second part involves iterative composite token updates using two auxiliary losses: an entropy loss to ensure diverse attention and a semantic binding loss to align the composite token’s prediction with that of the original phrase. This iterative update further refines the composite token embedding, leading to a more accurate generation.

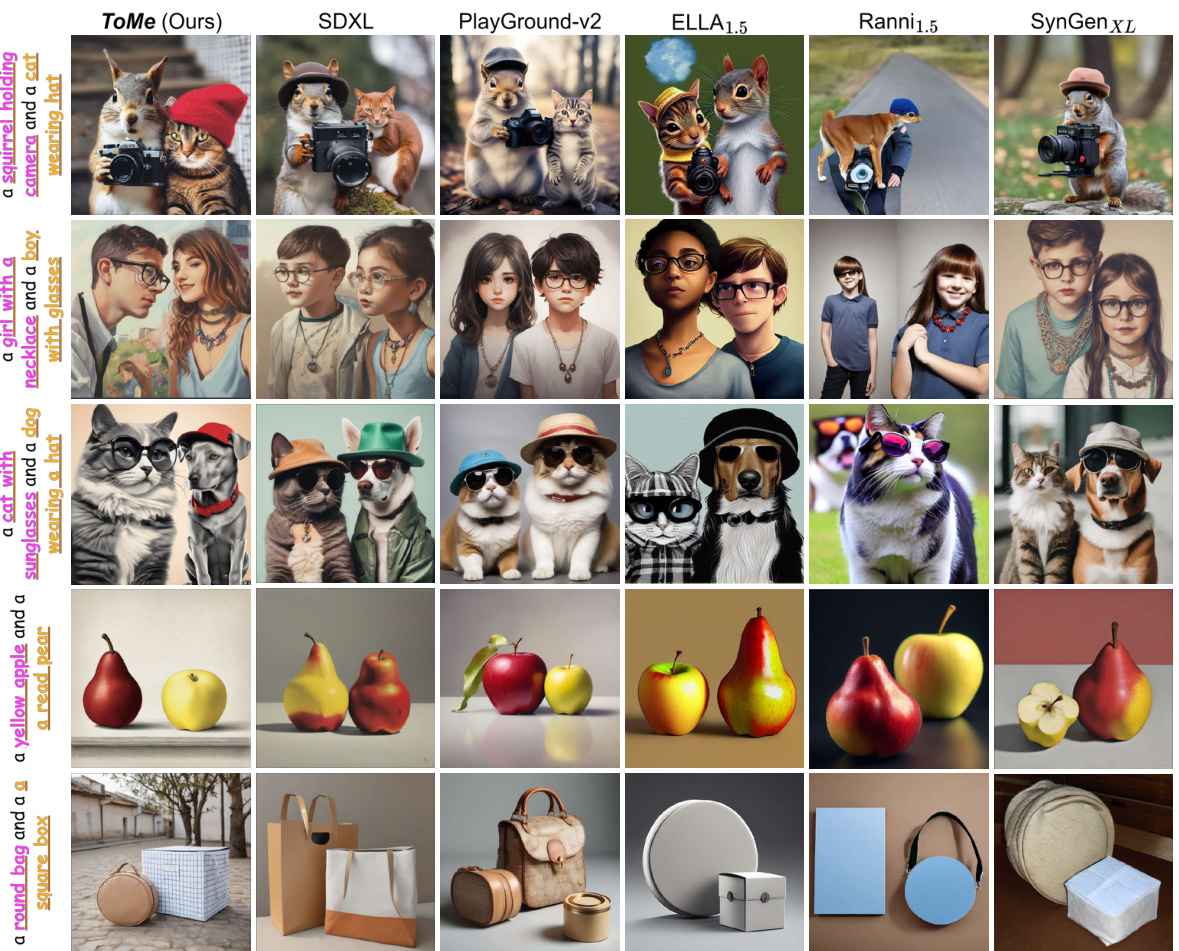

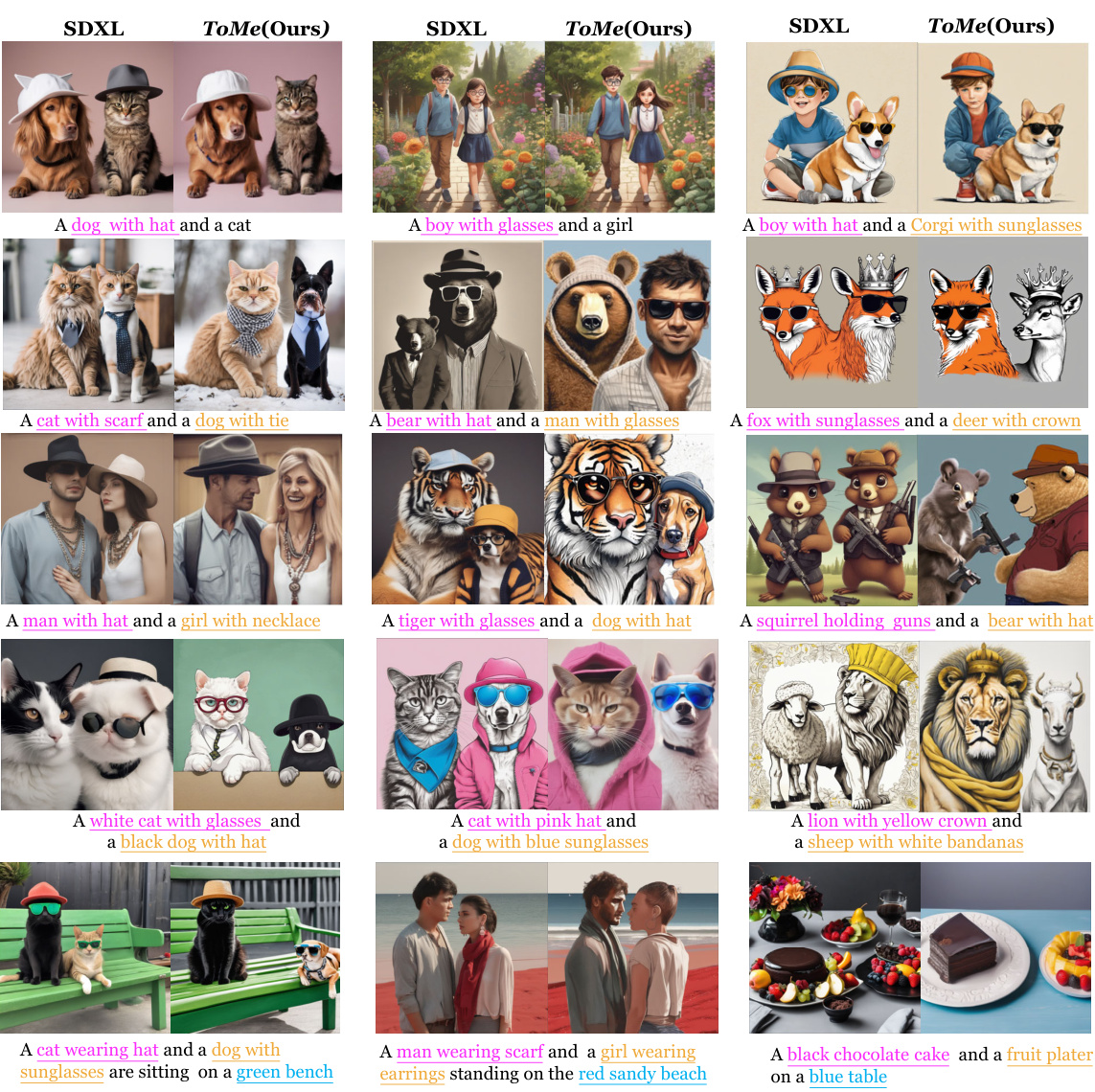

This figure compares the results of several text-to-image (T2I) generation methods on complex prompts involving multiple objects and attributes. The goal is to show how well each method handles semantic binding – the task of correctly associating objects with their attributes and other related objects. The figure visually demonstrates the strengths and weaknesses of different models in accurately representing the relationships specified in the text prompts. It highlights the superiority of the proposed ToMe method in achieving more accurate and faithful image generation compared to existing state-of-the-art methods such as SDXL, Playground v2, ELLA 1.5, Ranni 1.5, and SynGen XL.

This figure illustrates the two main components of the ToMe model. The first part shows the token merging and end token substitution processes. Relevant tokens are grouped into composite tokens to enhance semantic alignment. The second part depicts iterative updates of composite tokens, guided by two auxiliary loss functions (entropy loss and semantic binding loss) to refine the layout determination and generation integrity in the initial stages of text-to-image synthesis.

This figure demonstrates the versatility of the Token Merging (ToMe) method by showcasing its application beyond semantic binding. It shows three scenarios: 1. Add objects: Adding new objects to existing scenes, modifying the composition. An example here is adding glasses to an elephant. 2. Remove objects: Removing objects from the scene, demonstrating control over image composition. For instance, a woman’s earrings are removed. 3. Eliminate generation bias: Reducing biases by removing stereotypical attributes from existing object depictions. An illustration is modifying the depiction of a queen with cats and a nurse.

This figure presents statistical analysis supporting the concept of token additivity in text embeddings. Subfigure (a) shows example DetScore visualizations (probability of object detection). Subfigure (b) demonstrates that combining ‘dog’ and ‘hat’ embeddings (creating ‘dog*’) results in a higher probability of detecting ‘hat’ in generated images, similar to using the full phrase ‘dog wearing hat’. Subfigure (c) displays entropy calculations for each token in a prompt, illustrating that tokens later in the sequence have higher entropy, suggesting a less focused cross-attention map.

This figure illustrates the Token Merging (ToMe) method proposed in the paper. ToMe consists of two main parts: (a) Token Merging and End Token Substitution and (b) Iterative Composite Token Update. Part (a) shows how relevant tokens are aggregated into a single composite token to ensure semantic alignment. Part (b) illustrates the use of two auxiliary losses (entropy loss and semantic binding loss) to refine the composite token embeddings in the initial stages of image generation, improving overall generation integrity. The figure uses a visual representation to explain the process, detailing the flow of information and the key components.

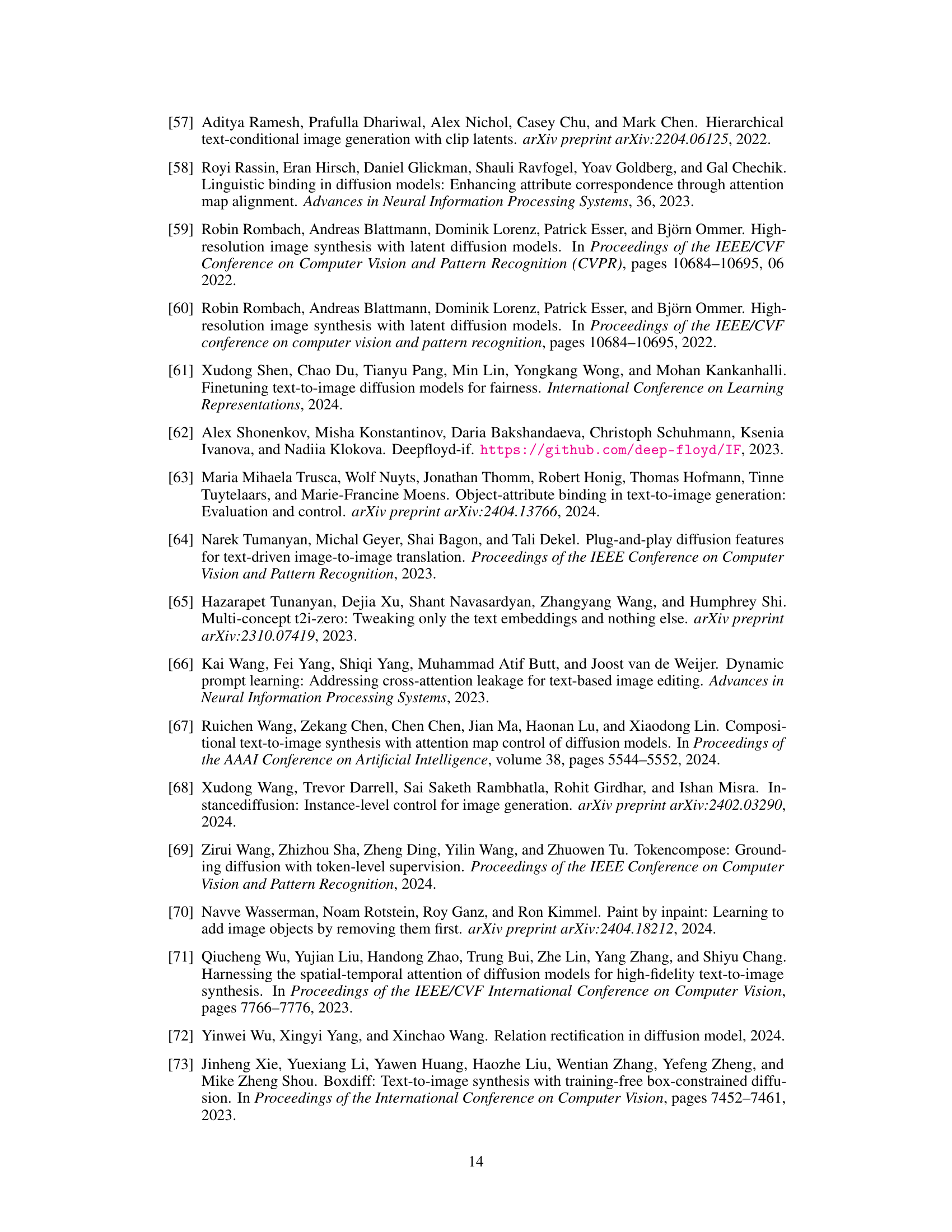

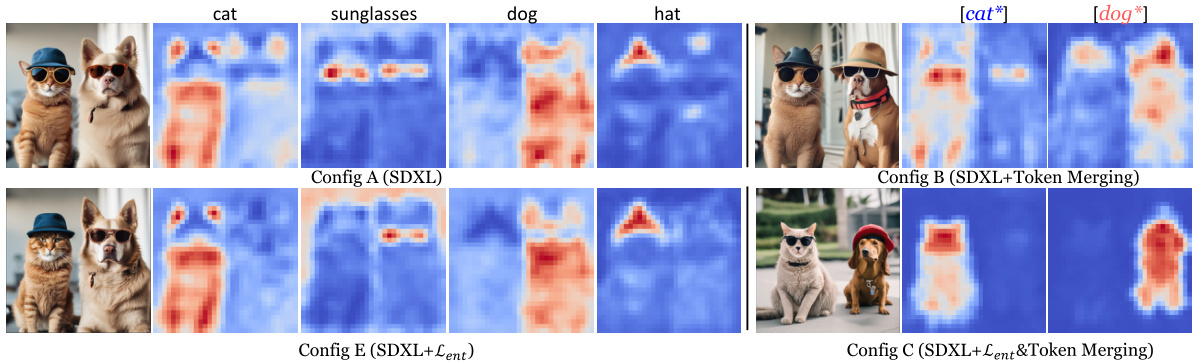

This figure visualizes the cross-attention maps generated by different configurations of the proposed method ToMe in comparison with the baseline SDXL model. The input prompt is ‘a cat wearing sunglasses and a dog wearing hat’. Config A shows the baseline SDXL model, which demonstrates attribute binding errors due to the misalignment of cross-attention maps. Config B shows the results of ToMe with token merging, indicating an improvement in alignment. Config E shows the result with the entropy loss, further concentrating the focus. Config C, incorporating both token merging and entropy loss, achieves the best semantic binding performance.

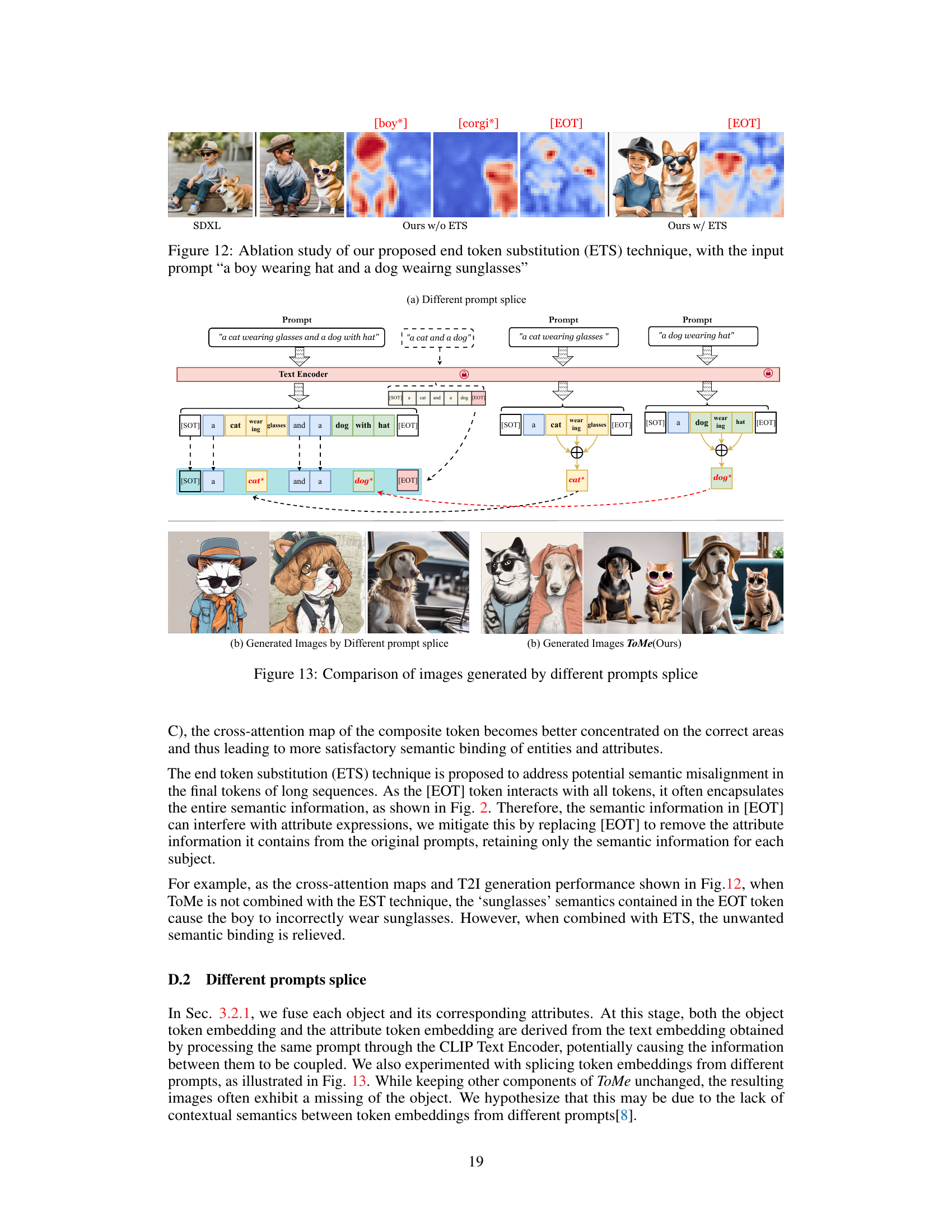

This figure demonstrates the effect of the proposed End Token Substitution (ETS) technique on the quality of image generation. The leftmost image shows the output of SDXL (a standard model) which struggles with the semantic binding issue in the prompt. The middle images show the results of the proposed ToMe method without ETS. Even without ETS, ToMe improves the image quality compared to SDXL. Finally, the rightmost image shows the results of the proposed ToMe method with ETS. ETS addresses potential issues caused by the end token [EOT] that might interfere with correct attribute assignment, further improving the image quality.

This figure illustrates the Token Merging (ToMe) framework, which is the core of the proposed method. It shows two main components: (a) Token Merging and End Token Substitution, which combines relevant tokens into composite tokens to ensure semantic alignment; and (b) Iterative Composite Token Update, which refines these composite tokens using an entropy loss and a semantic binding loss to improve generation integrity. The diagram visually represents the process of creating composite tokens from individual tokens in a sentence and the iterative update of these composite tokens.

This figure shows several examples of images generated by both SDXL and the proposed ToMe method. Each row shows a different prompt, demonstrating the method’s ability to handle complex scenarios involving multiple objects and their attributes. The results highlight ToMe’s improved performance in accurately binding objects to their attributes and in correctly representing the relationships between multiple objects within a scene.

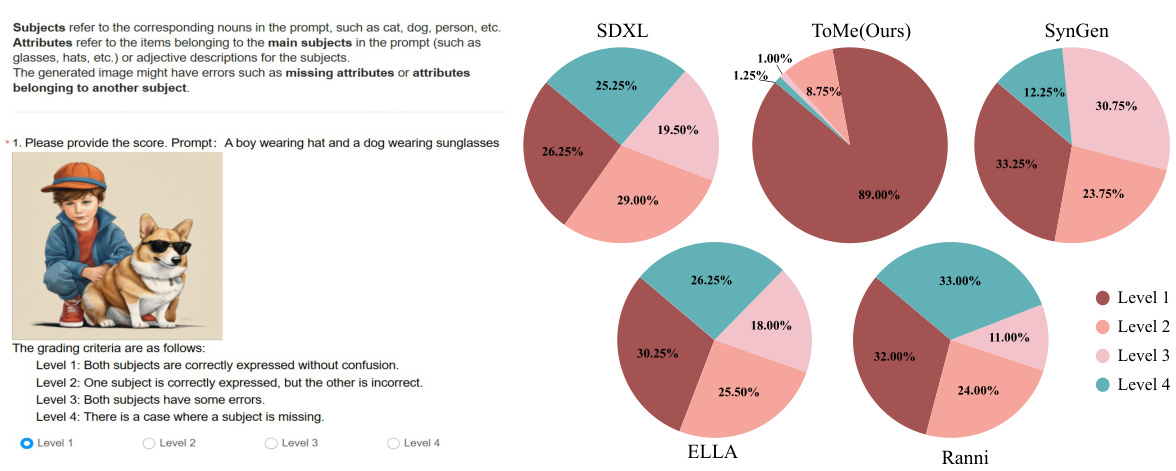

This figure displays the results of a user study assessing the semantic binding capabilities of different text-to-image generation methods. Twenty participants evaluated the quality of image generation using four levels (1-4), with Level 1 representing perfect semantic binding and Level 4 representing images with significant errors. The pie charts show the distribution of scores across the four levels for different methods: SDXL, ToMe (the proposed method), SynGen, ELLA, and Ranni. The study demonstrates ToMe’s superior performance in achieving accurate semantic binding compared to other approaches.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for semantic binding assessment across various benchmarking subsets (color, texture, and shape). The best and second-best scores are highlighted in blue and green respectively. It shows the BLIP-VQA scores, human preference scores, and GPT-40 scores for different methods on various datasets.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for semantic binding assessment. It shows BLIP-VQA scores (higher is better) for color, texture, and shape attributes across multiple benchmarking subsets. Human preference scores and GPT-40 scores are also included to provide a more comprehensive evaluation. The best and second-best scores are highlighted for clarity.

Full paper#