TL;DR#

Traditional robust mixture learning methods struggle when outliers significantly outnumber smaller groups, hindering the accurate estimation of group means. This paper addresses this challenge by introducing the concept of list-decodable mixture learning (LD-ML), where the goal is to produce a short list of estimates containing all group means. However, current LD-ML approaches suffer from suboptimal error guarantees and excessive list sizes.

This work presents a novel algorithm that significantly improves on existing LD-ML methods. The algorithm cleverly incorporates a two-stage process that first utilizes the mixture structure to partially cluster data points and then employs a refined list-decodable mean estimation algorithm for improved accuracy. This approach achieves order-optimal error guarantees with minimal list-size overhead, showcasing significant improvements, especially when groups are well-separated. The superior performance is validated through both theoretical analysis and experimental results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on robust statistics and mixture learning, particularly those dealing with high-dimensional data and a significant proportion of outliers. It provides order-optimal error guarantees and significantly improves upon existing methods for list-decodable mixture learning, a challenging problem with broad applications. The new algorithm also offers computational efficiency, making it practical for large-scale applications.

Visual Insights#

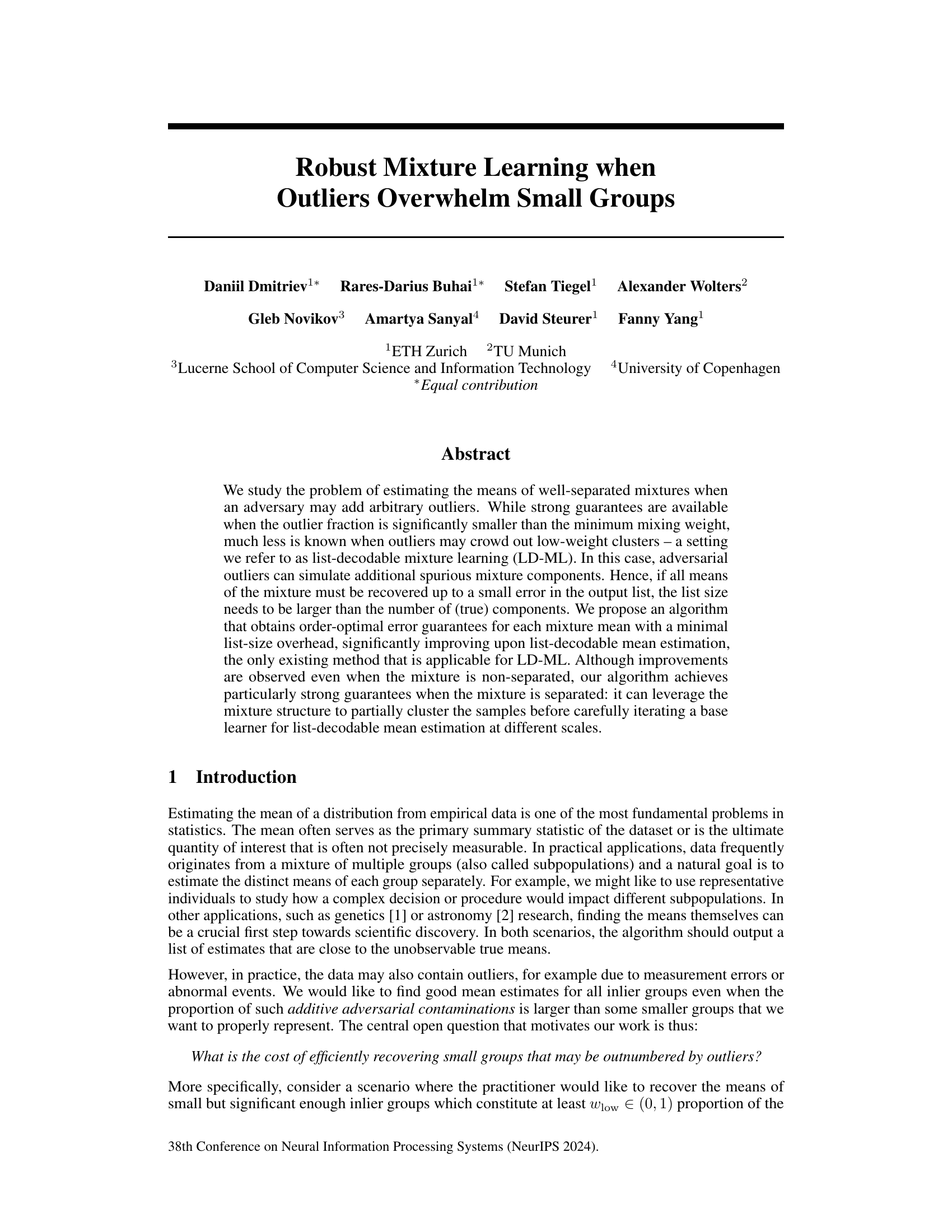

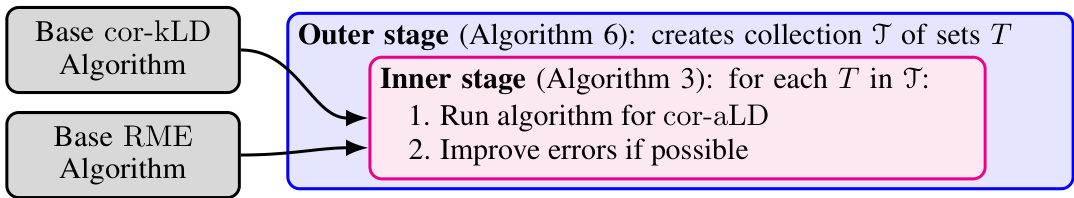

🔼 This figure shows a schematic of the two-stage meta-algorithm used in the paper. The outer stage (Algorithm 6) creates a collection of sets T, each of which should contain at most one inlier cluster. The inner stage (Algorithm 3) then processes each set T, first running a cor-aLD algorithm (list-decodable mean estimation with unknown inlier fraction) to obtain an initial estimate, and then potentially improving this estimate using a robust mean estimation algorithm (RME) if the inlier fraction is sufficiently large.

read the caption

Figure 1: Schematic of the meta-algorithm (Algorithm 2) underlying Theorem 3.3

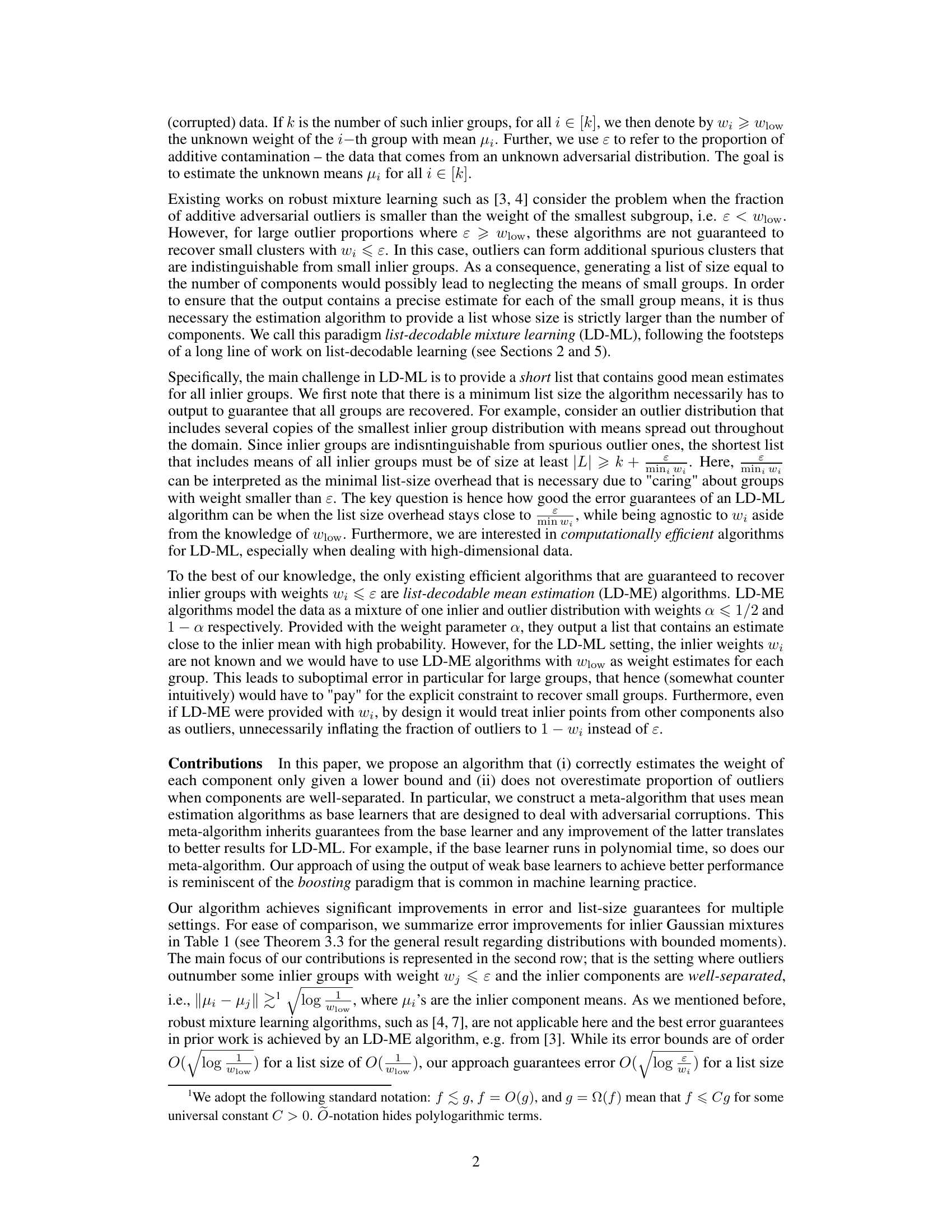

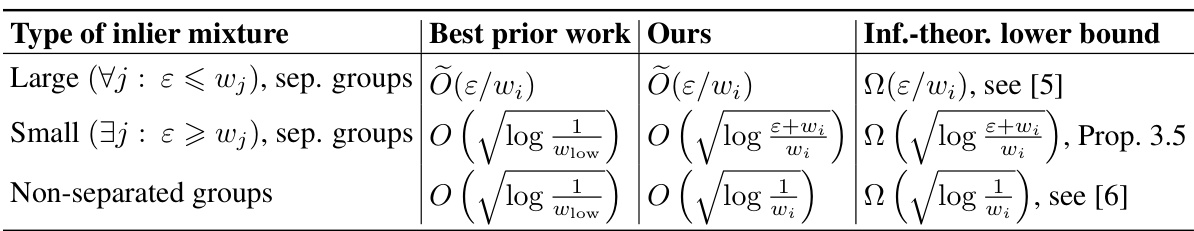

🔼 The table presents a comparison of upper and lower bounds on the error of different algorithms for estimating the mean of Gaussian mixture components. The comparison is performed for three types of inlier mixtures: large well-separated groups, small well-separated groups, and non-separated groups. For each type of mixture, the table shows the best prior work, the authors’ proposed algorithm, and an information-theoretic lower bound on the error.

read the caption

Table 1: For a mixture of Gaussian components N(µi, Id), we show upper and lower bounds for the error of the i-component given a output list L (of the respective algorithm) minû∈L ||û – μi||. When the error doesn't depend on i, all means have the same error guarantee irrespective of their weight. Note that depending on the type of inlier mixture, different methods in [3] are used as the 'best prior work': robust mixture learning for the first row and list-decodable mean estimation for the rest.

In-depth insights#

LD-ML Algorithm#

The core of this research paper revolves around a novel algorithm for list-decodable mixture learning (LD-ML), designed to address the challenges of estimating the means of well-separated data clusters when a significant proportion of outliers overwhelms smaller groups. The LD-ML algorithm’s key innovation lies in its two-stage process. The first stage leverages the mixture structure to partially cluster data, effectively mitigating the impact of outliers by isolating individual clusters. The second stage uses list-decodable mean estimation algorithms, adapting to the unknown weights of inlier groups. Unlike previous methods relying on a single weight parameter, this algorithm dynamically estimates weights, leading to improved accuracy and reduced list size overhead. It offers order-optimal error guarantees, demonstrating efficiency in various settings, including non-separated mixtures. The algorithm’s superior performance is validated through extensive simulations and comparisons with existing methods, emphasizing its robustness and computational efficiency. Furthermore, theoretical lower bounds are derived, highlighting the algorithm’s optimality in specific scenarios. Overall, the LD-ML algorithm provides a significant advance in robust mixture learning, particularly where outliers substantially outnumber smaller inlier groups.

Outlier Robustness#

Outlier robustness is a crucial aspect of any machine learning model, especially when dealing with real-world data, which is often noisy and contains outliers. This paper tackles the problem of robust mixture learning, focusing on scenarios where outliers may significantly outnumber smaller groups within the data. The core challenge lies in accurately estimating the means of these well-separated, low-weight clusters despite the presence of adversarial outliers. Existing techniques typically fail when outliers overwhelm small groups. The authors introduce list-decodable mixture learning (LD-ML), a novel framework that explicitly addresses this challenge. The proposed LD-ML algorithm achieves order-optimal error guarantees while minimizing the list-size overhead, significantly improving upon previous list-decodable mean estimation methods. A key contribution is the algorithm’s ability to leverage the mixture structure, even in non-separated settings, for enhanced performance. The work also provides information-theoretic lower bounds, demonstrating the near-optimality of their approach. Separation assumptions are explored, revealing the impact of data structure on the algorithm’s robustness to outliers.

Error Guarantees#

The research paper analyzes error guarantees for list-decodable mixture learning, a challenging problem where outliers may overwhelm small groups. The core contribution is an algorithm that provides order-optimal error guarantees for each mixture mean, even when outlier proportions are large. This significantly improves upon existing methods. The algorithm cleverly leverages the mixture structure, particularly in well-separated mixtures, to partially cluster samples before applying a base learner for list-decodable mean estimation. A key aspect is the algorithm’s ability to accurately estimate component weights despite only knowing a lower bound, which prevents the overestimation of outlier proportions. The paper also presents information-theoretic lower bounds, demonstrating the near-optimality of the proposed algorithm’s error guarantees for specific cases, such as Gaussian mixtures. The error bounds are shown to depend on factors like the relative proportion of inliers and outliers, as well as the separation between inlier components in the case of well-separated mixtures. In non-separated mixtures, improvements are still observed, highlighting the algorithm’s robustness. Overall, the work provides strong theoretical guarantees and significant improvements to the state-of-the-art in robust mixture learning.

Separation Matters#

The concept of “Separation Matters” in the context of robust mixture learning highlights the crucial role of distance between clusters in achieving accurate estimations, especially when outliers are abundant. Sufficient separation allows the algorithm to leverage the inherent structure of the data, partially clustering samples before refined estimations are performed. This contrasts with scenarios where clusters are close together or non-separated, leading to increased susceptibility to errors from outliers and the need for larger list sizes. Well-separated clusters allow for a more effective separation of inliers from outliers, leading to more accurate estimation of means for even small clusters, minimizing error and list size overhead. This is because the algorithm can leverage the distance between clusters to effectively isolate each cluster’s inliers from the outliers and other clusters’ inliers. The degree of separation directly impacts the algorithm’s robustness; stronger separation yields better results, significantly improving upon existing methods that lack this capability. This principle is particularly relevant in scenarios where outliers can overwhelm small groups, making the ability to distinguish between clusters based on their separation a key factor for success.

Future of LD-ML#

The future of list-decodable mixture learning (LD-ML) looks promising, particularly in scenarios with high-dimensional data and significant outlier proportions. Addressing these challenges requires further advancements in algorithm design, including the development of more efficient and robust base learners for mean estimation and potentially exploring alternative algorithmic frameworks beyond the current meta-algorithm approach. Research into optimal separation conditions for various distribution types and their impact on algorithm performance is also crucial. Information-theoretic lower bounds provide valuable guidance for setting realistic goals for future improvements. Another important area of future work lies in extending the scope of LD-ML to more complex settings, such as those involving non-separable or non-Gaussian mixtures. Furthermore, the exploration of practical applications and rigorous empirical evaluations using real-world datasets will be essential in establishing the true potential of LD-ML and guiding future research directions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

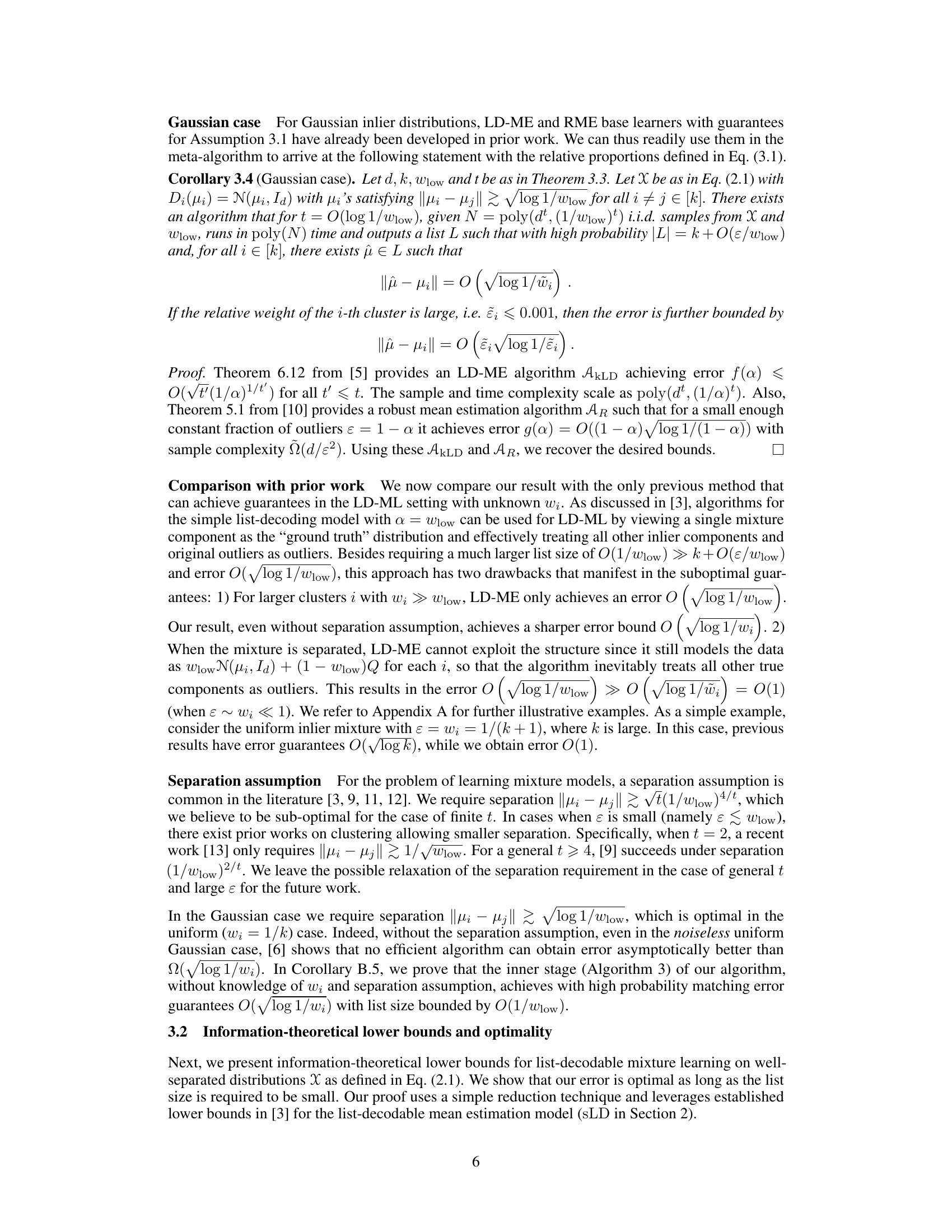

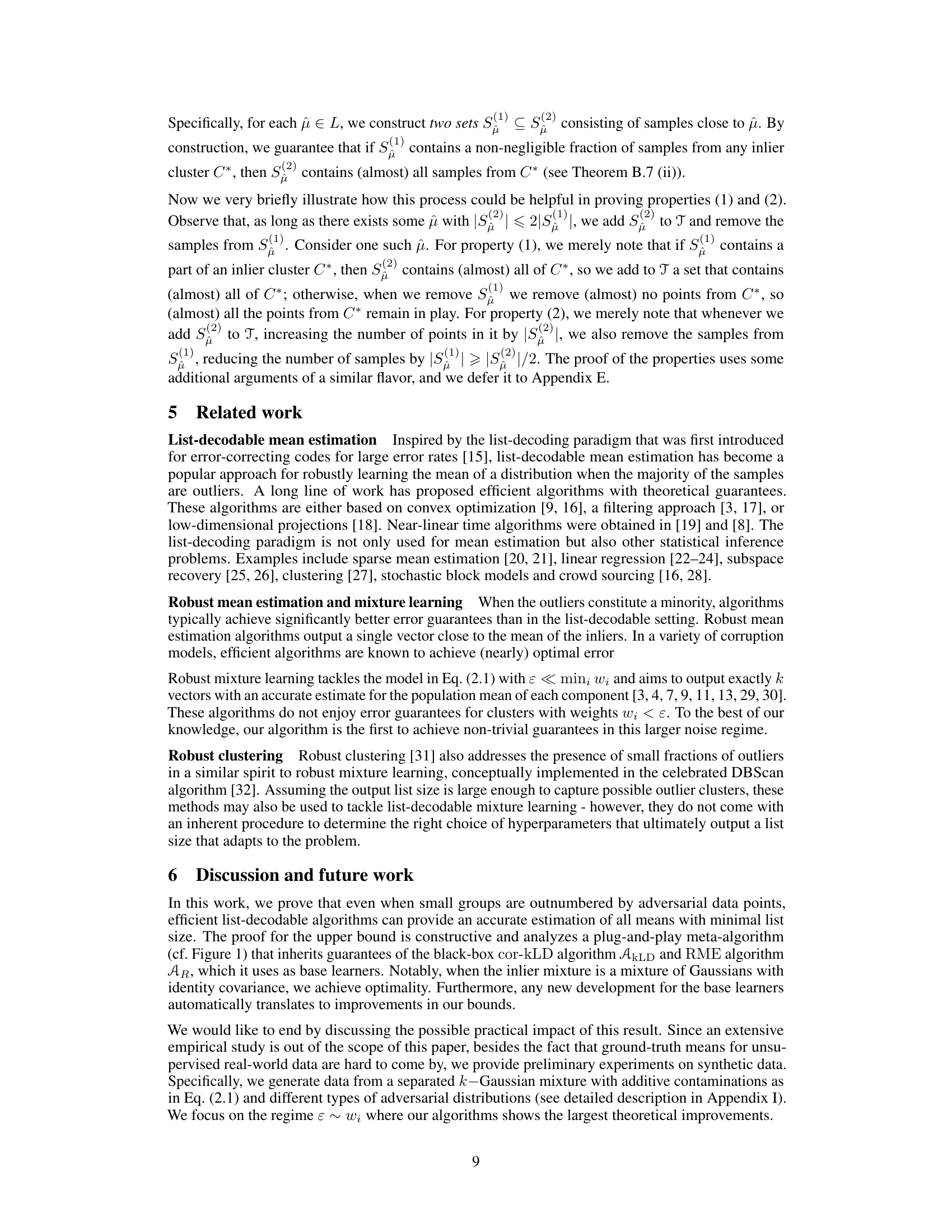

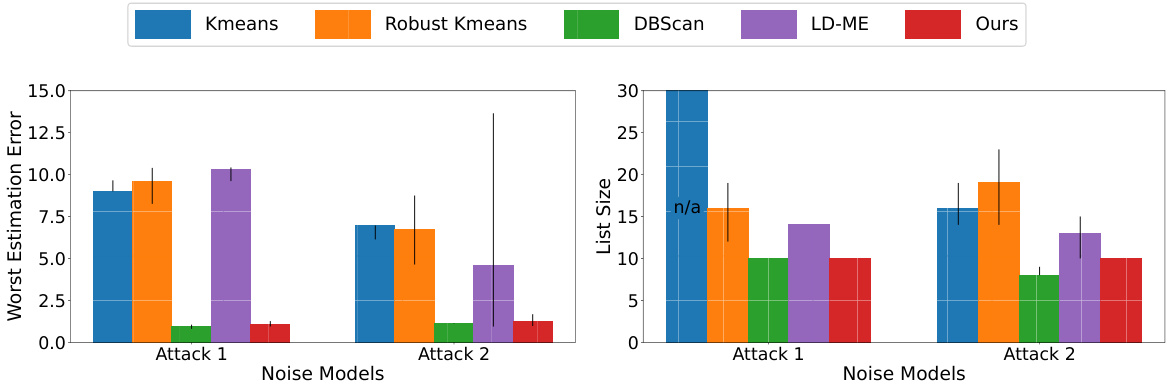

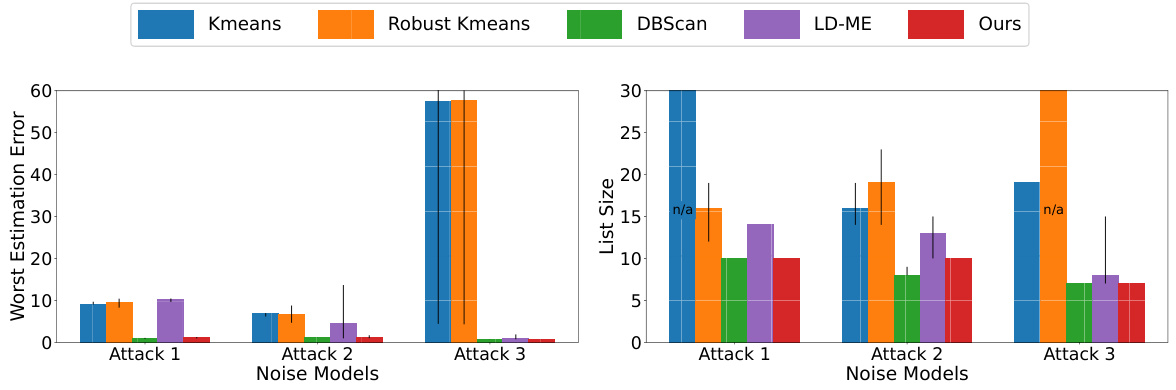

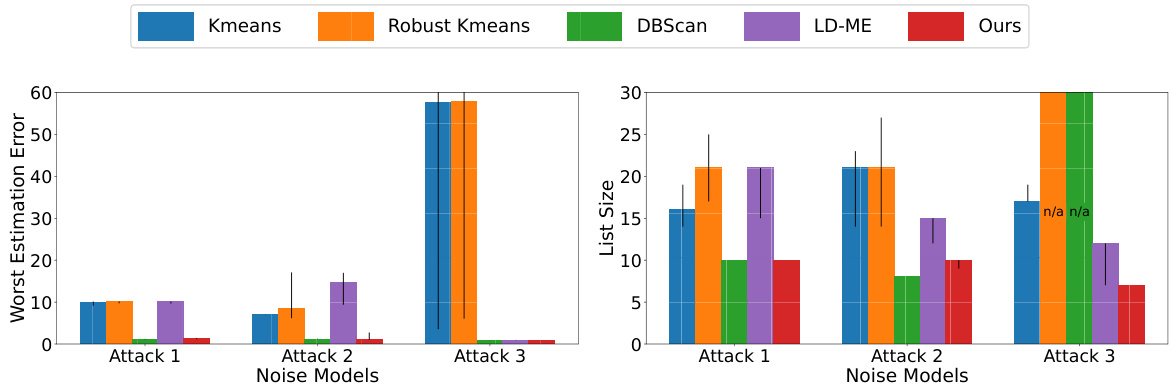

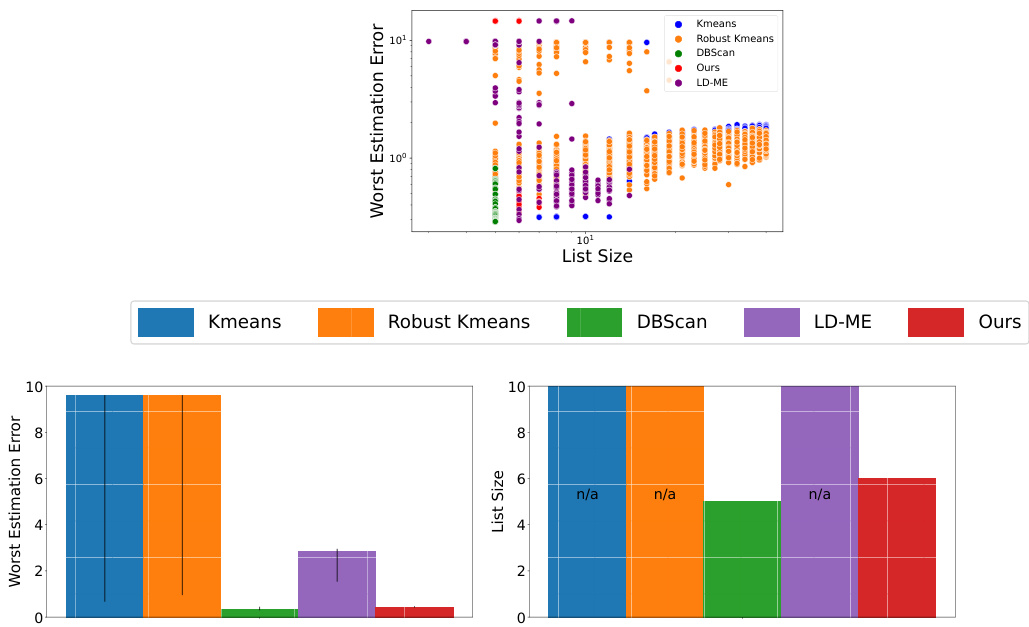

🔼 This figure compares five different algorithms (Kmeans, Robust Kmeans, DBScan, LD-ME, and Ours) using two different adversarial noise models (Attack 1 and Attack 2). The left side shows the worst estimation error for each algorithm when the list size is constrained. The right side shows the smallest list size needed to achieve a given worst-case error guarantee. Error bars indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles of the results across multiple runs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of five algorithms with two adversarial noise models. The attack distributions and further experimental details are given in Appendix I. On the left we show worst estimation error for constrained list size and on the right the smallest list size for constrained error guarantee. We plot the median of the metrics with the error bars showing 25th and 75th percentile.

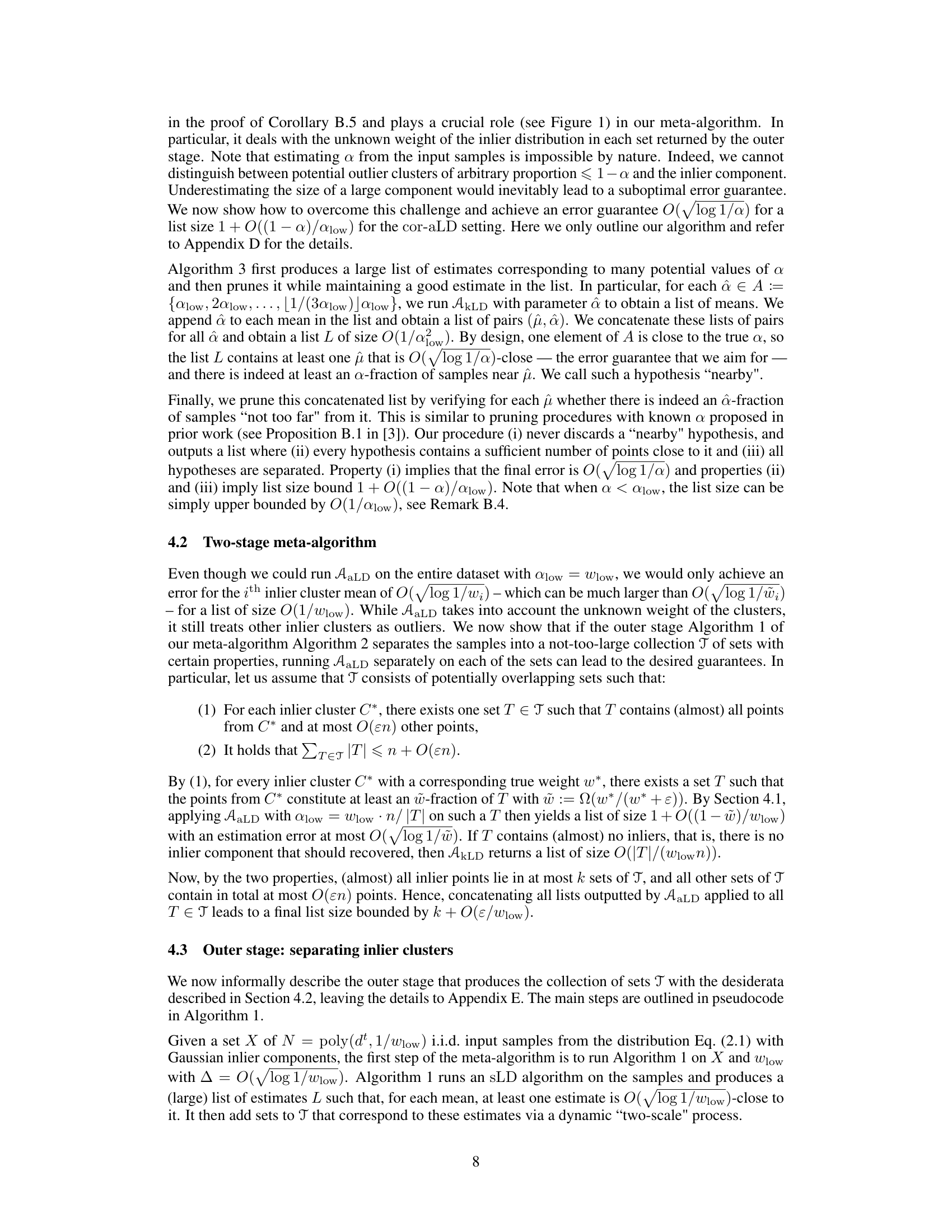

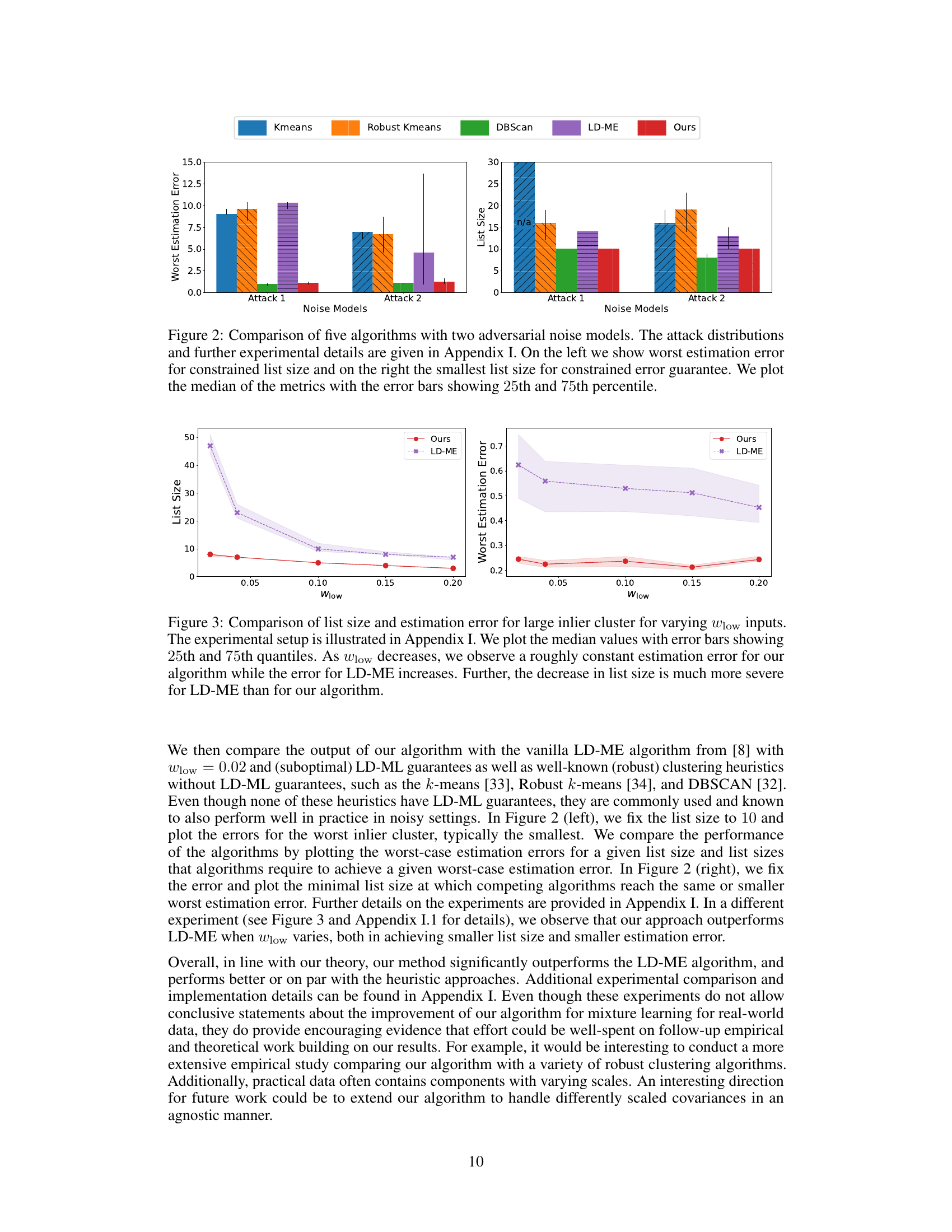

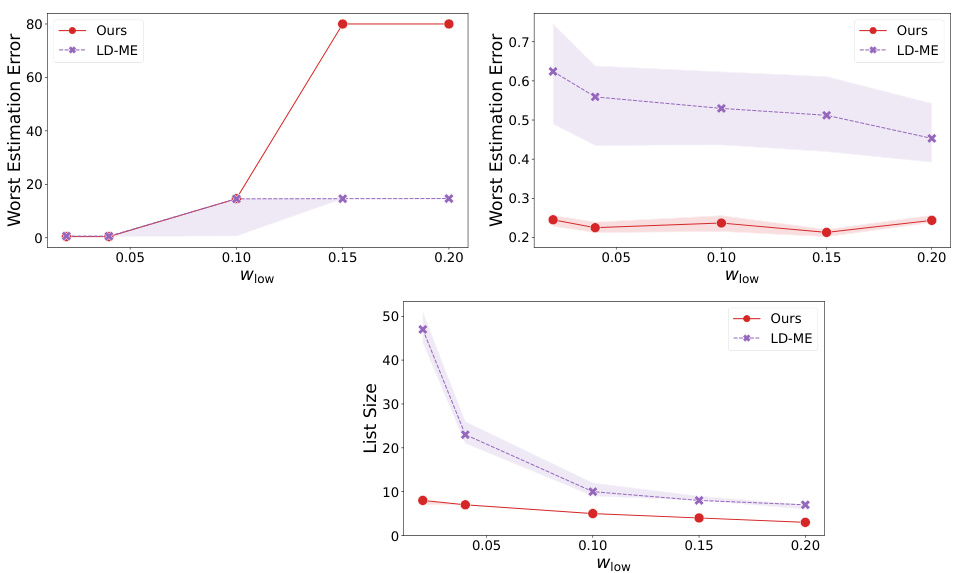

🔼 The figure compares the performance of the proposed algorithm and the baseline LD-ME algorithm on a mixture learning task with varying values of the smallest inlier weight (Wlow). The left panel shows the list sizes produced by both algorithms, while the right panel displays the worst estimation errors. The results indicate that the proposed algorithm maintains a relatively stable error while achieving a much smaller list size compared to LD-ME as Wlow decreases.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of list size and estimation error for large inlier cluster for varying Wlow inputs. The experimental setup is illustrated in Appendix I. We plot the median values with error bars showing 25th and 75th quantiles. As Wlow decreases, we observe a roughly constant estimation error for our algorithm while the error for LD-ME increases. Further, the decrease in list size is much more severe for LD-ME than for our algorithm.

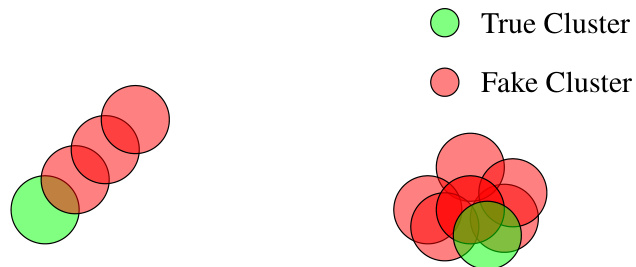

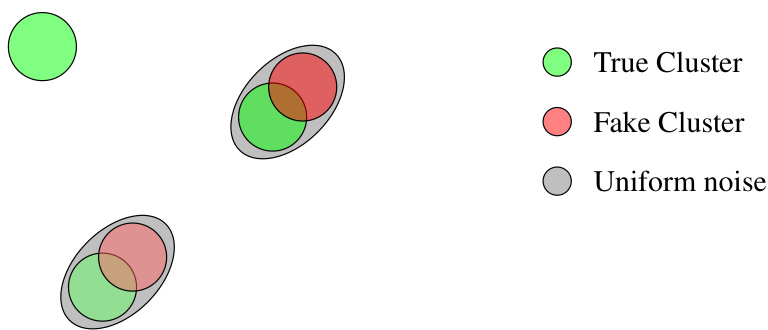

🔼 This figure illustrates two different ways adversarial data points can be generated. On the left, adversarial points form a line, situated close to a true data cluster. On the right, they form multiple clusters that overlap with a true data cluster. These examples help visualize how different types of adversarial data can affect the task of learning the means of mixture models.

read the caption

Figure 4: Two variants of adversarial distribution: adversarial line (left) and adversarial clusters (right).

🔼 This figure compares the performance of five different algorithms (Kmeans, Robust Kmeans, DBScan, LD-ME, and Ours) on two adversarial noise models (Attack 1 and Attack 2). The left panel shows the worst estimation error achieved when the list size is constrained. The right panel shows the smallest list size required to achieve a given error guarantee. Median values are plotted, with error bars representing the 25th and 75th percentiles, illustrating the variability in performance across multiple runs of each algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of five algorithms with two adversarial noise models. The attack distributions and further experimental details are given in Appendix I. On the left we show worst estimation error for constrained list size and on the right the smallest list size for constrained error guarantee. We plot the median of the metrics with the error bars showing 25th and 75th percentile.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of five different algorithms (Kmeans, Robust Kmeans, DBScan, LD-ME, and Ours) under two different adversarial noise models (Attack 1 and Attack 2). The left-hand side shows the worst estimation error for each algorithm, given a constraint on the maximum list size. The right-hand side shows the minimum list size needed to achieve a given level of worst estimation error. The median performance of each algorithm is shown, with error bars indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of five algorithms with two adversarial noise models. The attack distributions and further experimental details are given in Appendix I. On the left we show worst estimation error for constrained list size and on the right the smallest list size for constrained error guarantee. We plot the median of the metrics with the error bars showing 25th and 75th percentile.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of five different algorithms (Kmeans, Robust Kmeans, DBScan, LD-ME, and the proposed algorithm) under two different adversarial noise models (Attack 1 and Attack 2). The left panel shows the worst estimation error achieved when the algorithms are constrained to output a list of a certain size. The right panel shows the smallest list size required by each algorithm to achieve a given level of worst-case estimation error. The results are shown as median values with error bars indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of five algorithms with two adversarial noise models. The attack distributions and further experimental details are given in Appendix I. On the left we show worst estimation error for constrained list size and on the right the smallest list size for constrained error guarantee. We plot the median of the metrics with the error bars showing 25th and 75th percentile.

🔼 This figure shows two different ways to generate adversarial data points that are designed to be difficult for algorithms to distinguish from true data points. The left panel shows an ‘adversarial line’ where outliers are placed along a line that extends beyond the range of the true data points, whereas the right panel shows ‘adversarial clusters’ where additional clusters are added near true data clusters, making it difficult to distinguish between the true and fake data points.

read the caption

Figure 4: Two variants of adversarial distribution: adversarial line (left) and adversarial clusters (right).

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed algorithm and LD-ME algorithm in terms of estimation error and list size for small and large clusters under varying Wlow (lower bound on inlier group weights). The results show that the proposed algorithm maintains a relatively constant estimation error for large clusters as Wlow decreases, while the LD-ME algorithm’s error increases. The list sizes of both algorithms also decrease as Wlow decreases, but the proposed algorithm shows better performance.

read the caption

Figure 9: Comparison of list size and estimation error for small and large inlier clusters for varying Wlow inputs. The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 8. The plot on the top left shows the estimation error for the small cluster and the plot on the top right shows the error for the large cluster. We plot the median values with error bars indicating 25th and 75th quantiles. As Wlow decreases, our algorithm maintains a roughly constant estimation error for the large cluster, while the error for LD-ME increases.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of five different algorithms (Kmeans, Robust Kmeans, DBScan, LD-ME, and Ours) under two different adversarial attack models. The left panel shows the worst-case estimation error for each algorithm when the list size is constrained. The right panel shows the smallest list size needed to achieve a given error guarantee. The median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile of each metric are plotted for each algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of five algorithms with two adversarial noise models. The attack distributions and further experimental details are given in Appendix I. On the left we show worst estimation error for constrained list size and on the right the smallest list size for constrained error guarantee. We plot the median of the metrics with the error bars showing 25th and 75th percentile.

Full paper#