↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Cancer prognosis prediction from pathology images is challenging due to high dimensionality, intratumor heterogeneity and complex tissue interactions. Existing methods often overlook these aspects, leading to suboptimal performance. This necessitates approaches that effectively capture both spatial context and tissue-specific contributions to prognosis.

The proposed ProtoSurv addresses these limitations with a novel heterogeneous graph model that integrates both spatial and tissue-type information. It uses a unique two-view architecture (Structure and Histology views) to capture both local spatial context and global tissue characteristics. ProtoSurv outperforms state-of-the-art methods across five cancer types from the TCGA dataset, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving survival prediction.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in oncology and computer vision because it presents a novel approach to improve cancer prognosis prediction using whole slide images (WSIs). It leverages tumor heterogeneity and spatial information within WSIs, improving accuracy and interpretability, and opens avenues for developing more robust and clinically relevant predictive models.

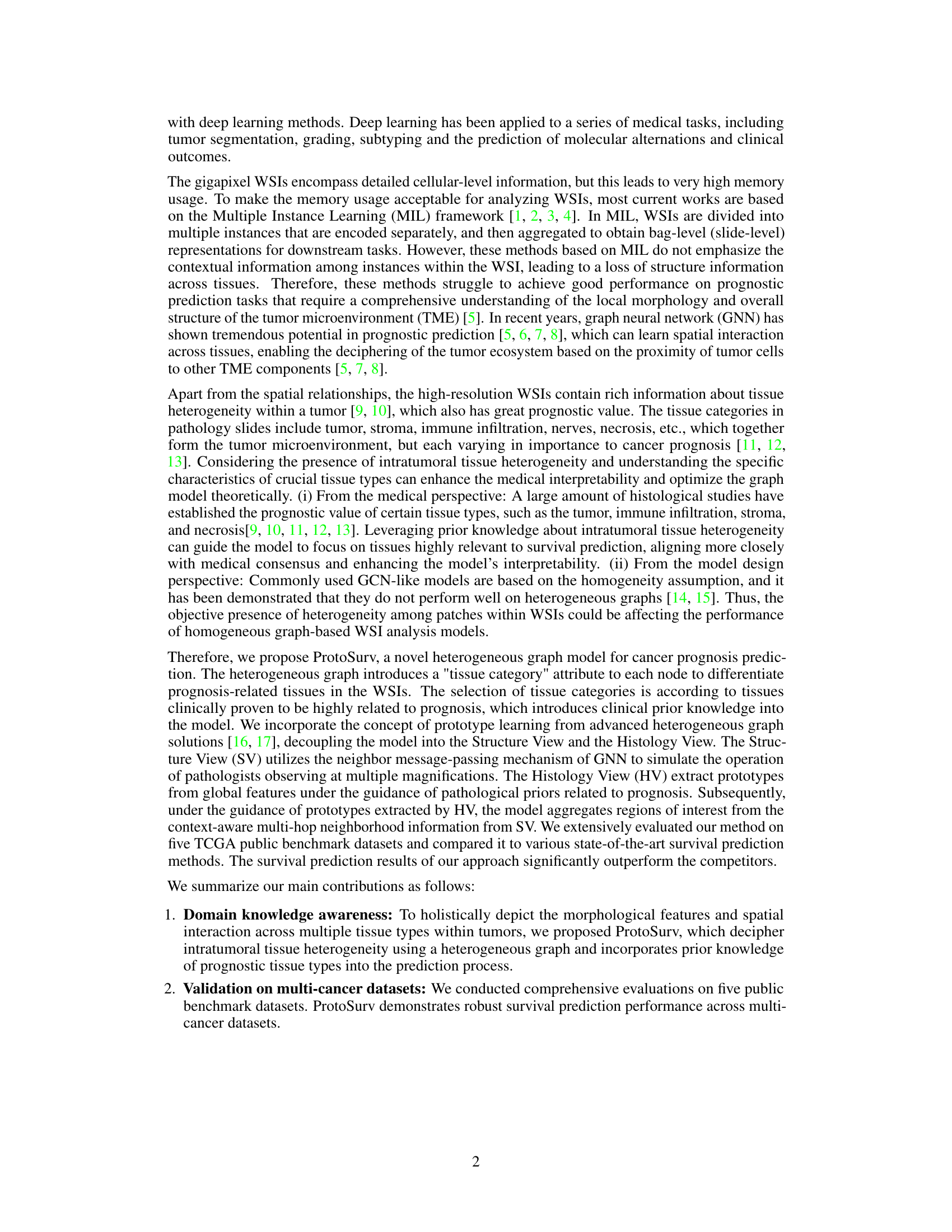

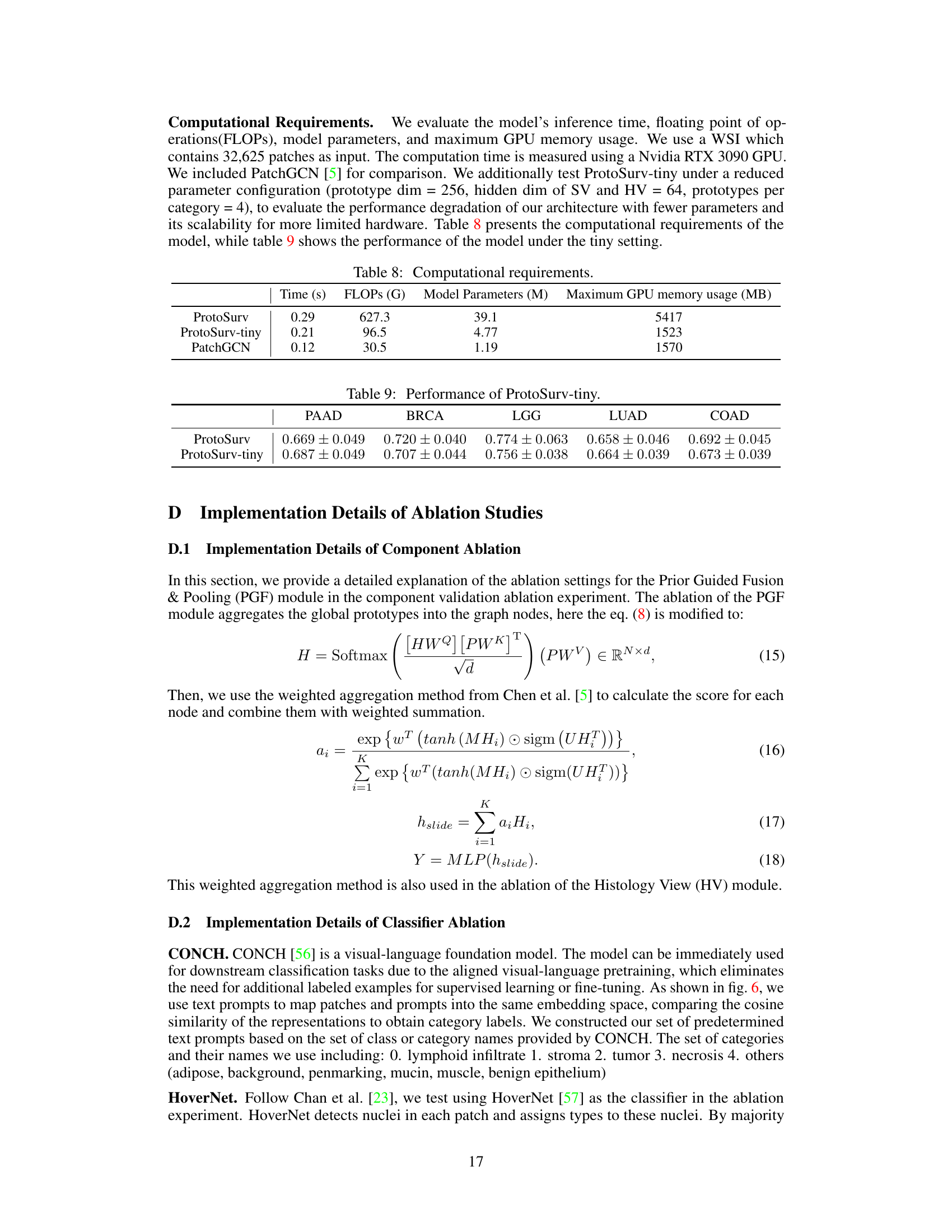

Visual Insights#

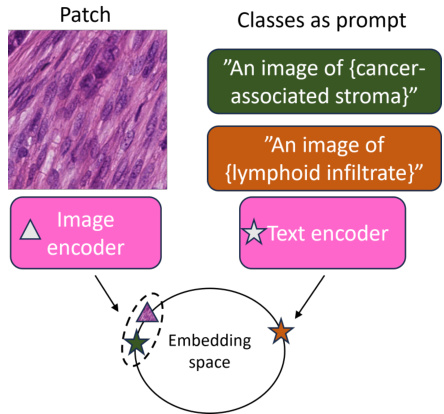

This figure provides a high-level overview of the ProtoSurv architecture, a novel heterogeneous graph model for cancer prognosis prediction. It shows the three main steps: 1) Preprocessing & Patching: WSIs are preprocessed and divided into patches which are encoded and classified into different tissue types using a pre-trained UNI model. 2) Heterogeneous Graph Construction: A heterogeneous graph is constructed based on the tissue types of each patch and spatial adjacency between them. 3) ProtoSurv: The heterogeneous graph is processed by two views: the Structure View, leveraging a GCN for multi-hop neighborhood information, and the Histology View, learning global multi-prototype representations for each tissue category. Finally, a Prior Guided Fusion module combines information from both views for survival risk prediction.

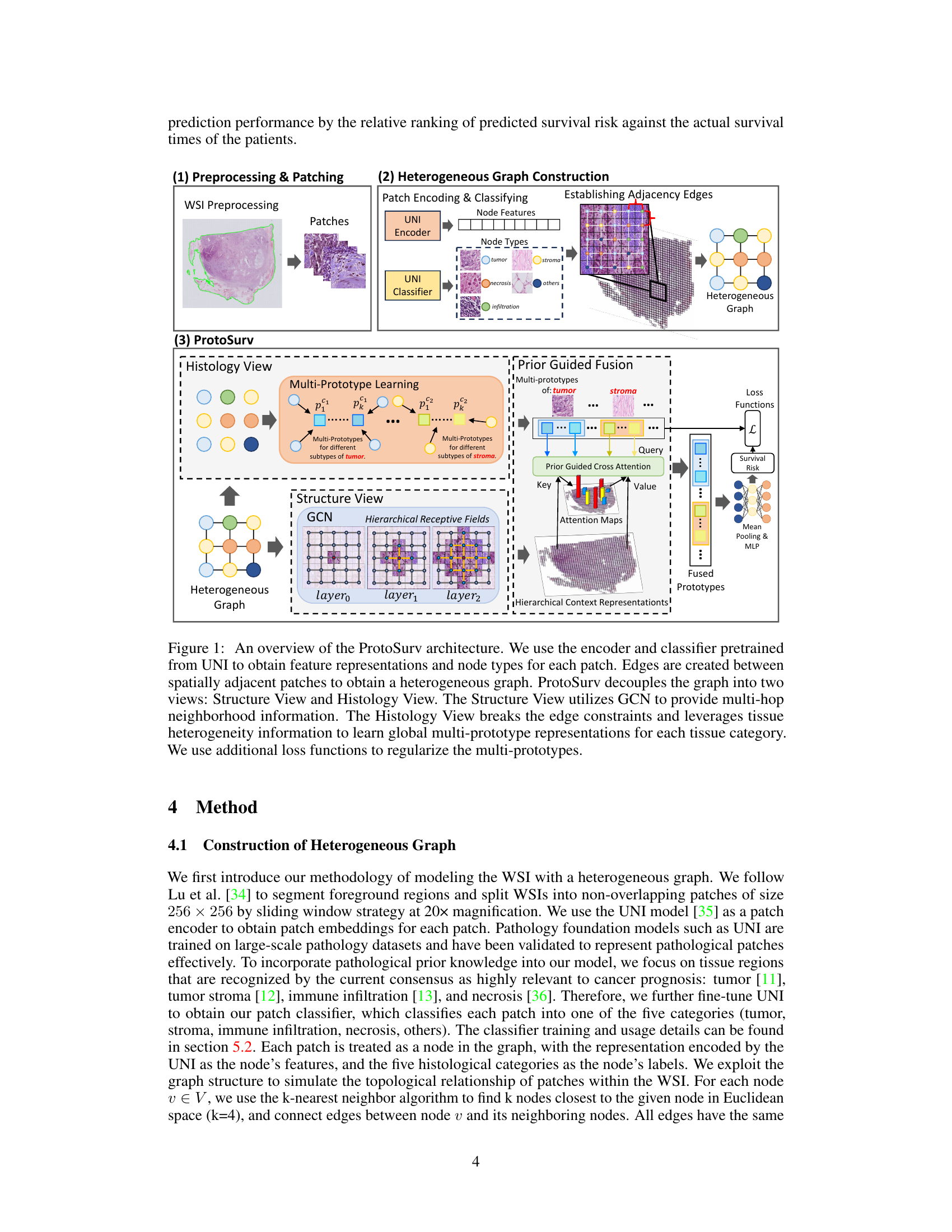

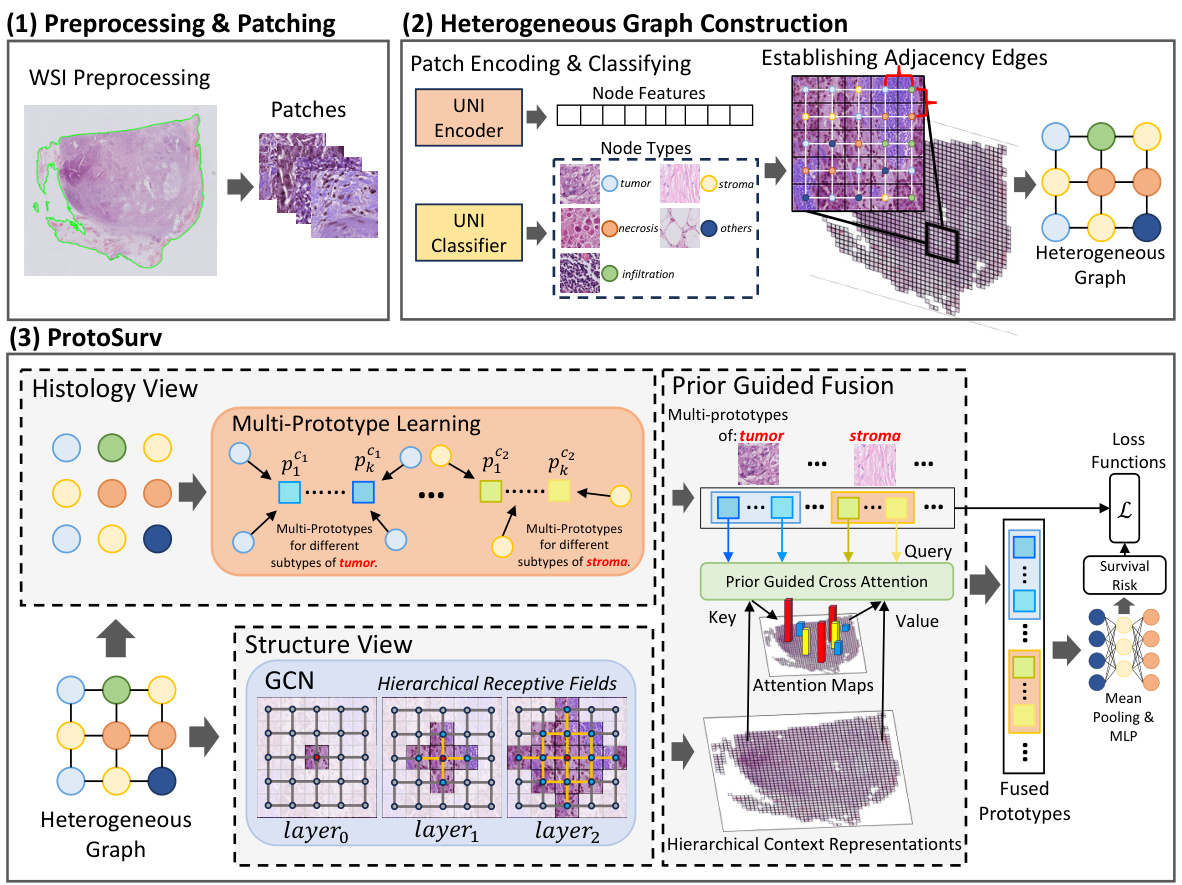

This table presents the concordance index (C-index), a measure of the accuracy of survival prediction models, for five different cancer types (BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD, PAAD) using various methods, including the proposed ProtoSurv model. The C-index is reported as the mean and standard deviation across five-fold cross-validation. The best and second-best performing methods for each cancer type are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

Heterogeneous Graph#

The concept of a heterogeneous graph is pivotal in analyzing complex systems where different types of nodes and relationships coexist. In the context of this research paper, a heterogeneous graph likely represents the tumor microenvironment as a network. Different cell types (cancer cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, etc.) are modeled as distinct node types, each possessing unique features. The edges, representing interactions between these cells, could be weighted based on proximity or signaling strength, adding another layer of complexity. This approach moves beyond simplistic homogeneous graph models, which often struggle to capture the nuances of multifaceted biological systems. By explicitly modeling the heterogeneity, the heterogeneous graph offers a richer, more accurate representation of the tumor ecosystem, potentially improving the predictive capabilities of cancer survival models by capturing complex interactions that influence prognosis.

ProtoSurv Model#

The ProtoSurv model is a novel heterogeneous graph neural network designed for cancer survival prediction using Whole Slide Images (WSIs). Its key innovation lies in integrating domain knowledge about tissue heterogeneity and the prognostic significance of specific tissue types. Unlike homogeneous graph methods, ProtoSurv explicitly models the differences between various tissue categories (tumor, stroma, immune infiltration, etc.) within the tumor microenvironment. This is achieved by incorporating a “tissue category” attribute to each node in the graph, enabling the network to learn distinct representations for each tissue type. ProtoSurv’s architecture cleverly decouples the learning process into two views: a Structure View utilizing Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to capture spatial interactions between patches, and a Histology View employing prototype learning to extract global features from specific tissue categories. The two views are then fused using a prior-guided approach, effectively leveraging both local spatial context and global tissue-specific information. This design improves the model’s ability to discern the complex interplay of factors influencing cancer prognosis, yielding superior performance compared to existing methods. The use of multiple prototypes per tissue category enhances the model’s ability to capture intra-tissue heterogeneity. The model also incorporates loss functions that regularize the learned prototypes, further improving interpretability and performance.

Multi-Prototype Learning#

Multi-prototype learning, in the context of analyzing Whole Slide Images (WSIs) for cancer prognosis, offers a powerful approach to address tissue heterogeneity. Instead of relying on a single prototype per tissue type, this method leverages multiple prototypes to capture the diverse phenotypes and sub-types often present within a single tissue category. This is crucial because different subtypes of the same tissue (e.g., tumor stroma) can have vastly different prognostic implications. By learning distinct prototypes, the model can effectively disentangle the complex interplay of tissue characteristics and their contribution to survival prediction. This nuanced representation leads to a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the tumor microenvironment and improves the model’s ability to predict patient survival. The incorporation of prior pathological knowledge further enhances the interpretability and clinical relevance of the learned prototypes, aligning the model’s insights with established medical understanding of cancer progression.

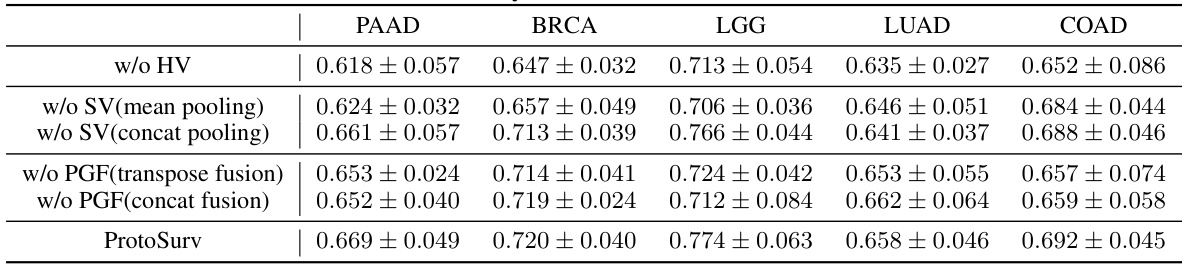

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically remove components of a model to understand their individual contributions. In this context, it’s crucial to identify which components are tested (e.g., specific layers, modules, or data augmentation techniques). The results should clearly indicate the impact of each ablation on the overall performance. A well-designed ablation study carefully controls for confounding variables, ensuring that performance changes are directly attributable to the removed component and not other factors. Quantifiable metrics are essential to assess the impact; using multiple metrics provides a more comprehensive evaluation. The interpretation of results needs careful consideration. A significant drop in performance may suggest a critical component, while minimal change might suggest redundancy or less importance. A strong ablation study will not only demonstrate the importance of individual components but also elucidate their interactions and provide insights for future model improvements.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore improving tissue classification by leveraging self-supervised learning or weakly supervised methods to reduce reliance on large annotated datasets. Developing more sophisticated graph neural network architectures that better capture complex spatial relationships within the tumor microenvironment, possibly incorporating attention mechanisms or transformers, warrants investigation. Furthermore, exploring multi-modal integration by incorporating other imaging modalities (e.g., immunohistochemistry, fluorescence microscopy) with WSIs is a promising direction. Finally, robust validation across diverse patient populations and cancer types is crucial to ensure generalizability and clinical applicability of the proposed method. This will also facilitate the development of explainable AI models to improve clinical trust and decision-making.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure visualizes the attention mechanism within the ProtoSurv model, specifically focusing on the multi-prototypes and their interactions with different tissue categories in the image. Panel A shows attention maps highlighting the regions of interest for each prototype. Panel B displays the top four patches with the highest attention scores, along with the proportion of each tissue category within the top 1000 patches. Panel C shows the proportion of twelve intratumoral tissue categories across the entire image. Together, these panels illustrate how ProtoSurv leverages tissue heterogeneity and prior knowledge to refine survival risk predictions.

This figure illustrates how the Structure View in the ProtoSurv model leverages multi-hop neighborhood information. It shows three stages of information aggregation. The first stage displays individual 256x256 patches (nodes) within a larger 1280x1280 context. The second stage shows a single hop aggregation with connections between adjacent patches, and the third stage demonstrates a two-hop aggregation, where information from more distant patches is incorporated.

This figure provides a high-level overview of the ProtoSurv architecture, illustrating its key components and workflow. It shows how the model processes whole slide images (WSIs) by first generating a heterogeneous graph from patches, then utilizing a Structure View (based on Graph Convolutional Networks) and a Histology View (based on prototype learning) to capture spatial and tissue-specific information. The two views are combined through a Prior Guided Fusion step, resulting in a final survival risk prediction.

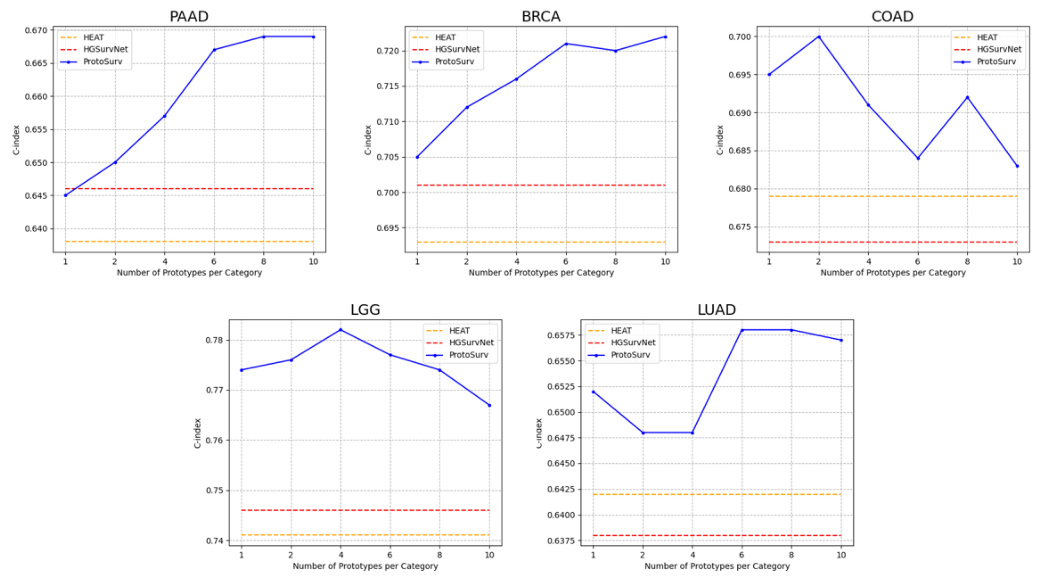

This figure shows the ablation study on the impact of the number of prototypes per category on the model’s performance. The results show that increasing the number of prototypes generally improves performance across all five cancer types, demonstrating the effectiveness of using multiple prototypes per class to capture the feature distribution of different subtypes within a tissue category.

This figure provides a high-level overview of the ProtoSurv architecture, illustrating its main components and workflow. It shows how the model processes whole slide images (WSIs) by creating a heterogeneous graph from patches, then using two parallel views (Structure and Histology) to learn representations. The Structure View uses a graph convolutional network (GCN) to capture spatial relationships, while the Histology View utilizes prototype learning to extract global features for different tissue types. Finally, it highlights the fusion of these views and the use of loss functions to refine the model’s parameters.

This figure provides a high-level overview of the ProtoSurv architecture, a heterogeneous graph model for cancer prognosis prediction. It shows how the model uses a pretrained encoder and classifier to process patches from a Whole Slide Image (WSI), creating a heterogeneous graph based on spatial adjacency and tissue type. The model then separates into Structure and Histology Views. The Structure View uses a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to learn spatial relationships between patches, while the Histology View focuses on learning multi-prototype representations for each tissue category, leveraging tissue heterogeneity information to improve accuracy. Additional loss functions are used to regularize the multi-prototypes.

This figure shows microscopic images of three different subtypes of tumor stroma: inactivated stroma, intermediate stroma, and activated stroma. The images illustrate the varying cellular compositions and tissue architectures characteristic of each subtype, highlighting the heterogeneity observed within stromal tissue.

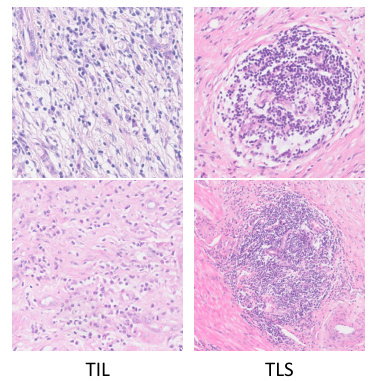

This figure shows various subtypes of immune infiltration observed in tissue samples. The different subtypes likely represent different immune cell compositions and activities within the tumor microenvironment, which may have differing prognostic implications. Understanding these variations is crucial for accurate prediction of cancer survival. The figure supports the paper’s use of multiple prototypes to represent the heterogeneity within each tissue category.

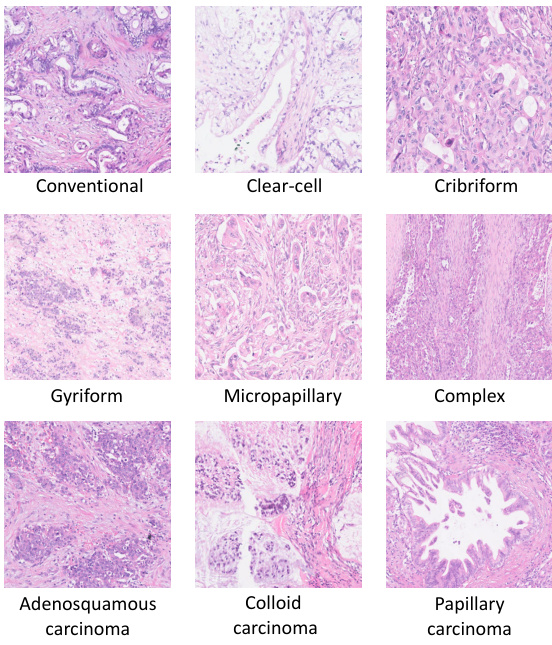

This figure shows different subtypes of tumor tissues, including Conventional, Clear-cell, Cribriform, Gyriform, Micropapillary, Complex, Adenosquamous carcinoma, Colloid carcinoma, and Papillary carcinoma. Each subtype is visually represented by a micrograph image, illustrating the visual diversity within the ’tumor’ tissue category. The inclusion of multiple visual examples highlights the heterogeneity present even within a single broad tissue class. This visual representation is used in the paper to support the use of multi-prototypes within the ProtoSurv model, acknowledging that even within a single tissue class, multiple subtypes with varying prognostic relevance exist.

More on tables

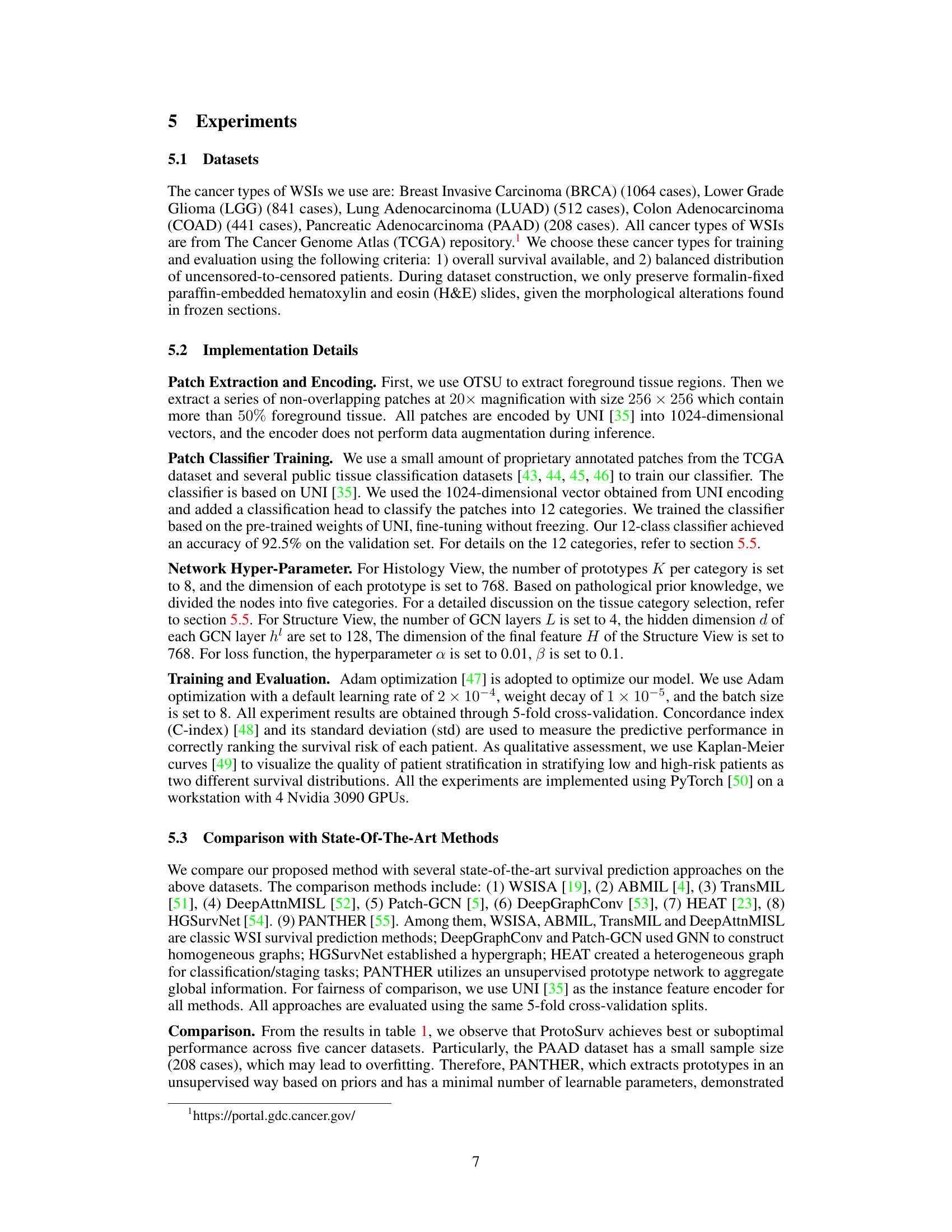

This table presents the ablation study results for the main modules of the ProtoSurv model: Histology View (HV), Structure View (SV), and Prior Guided Fusion & Pooling (PGF). It shows the C-index (mean ± std) achieved by different model variations across five cancer datasets (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD), demonstrating the contribution of each module and the effectiveness of the proposed PGF module in combining the features from the other two modules.

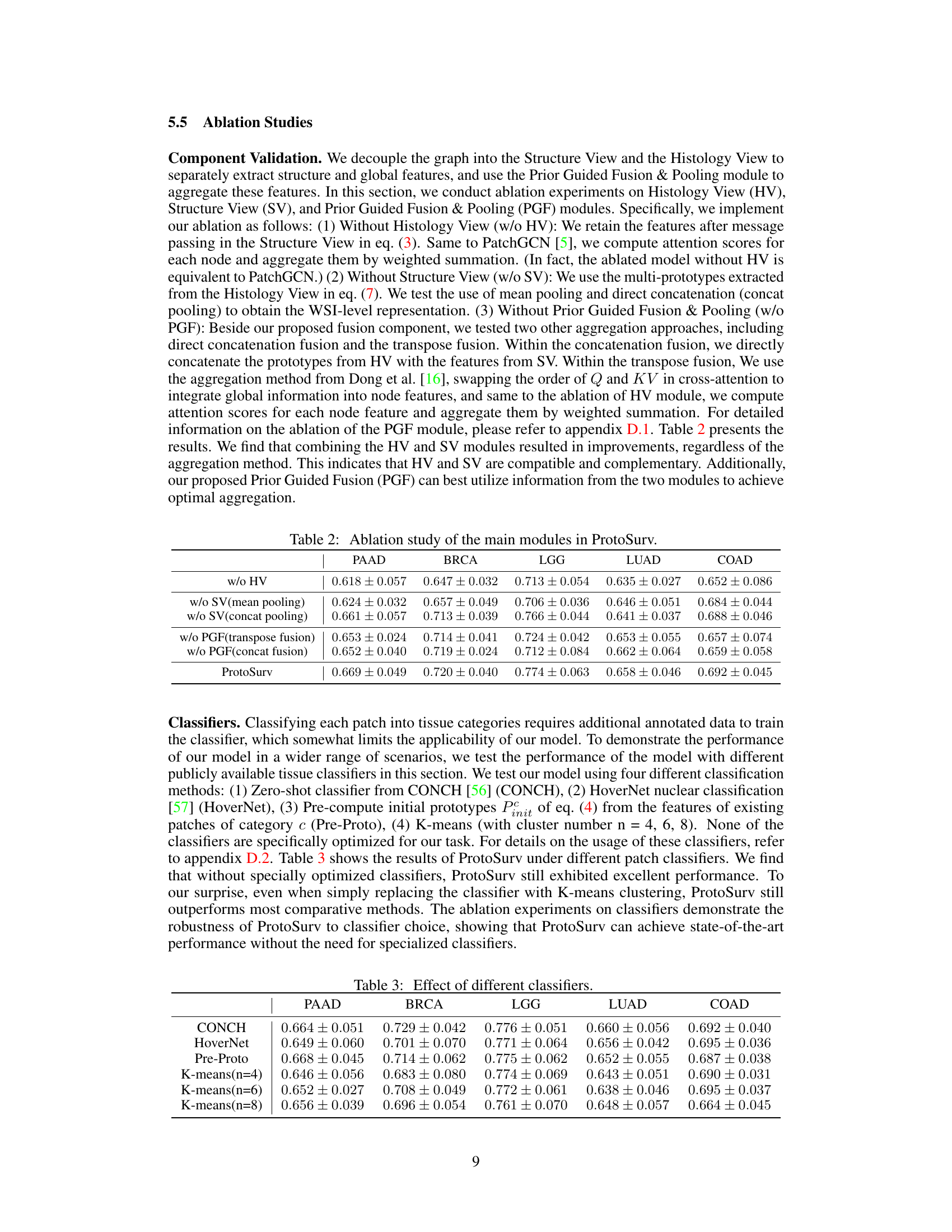

This table presents the results of ProtoSurv using different patch classifiers: CONCH, HoverNet, Pre-Proto, and K-means with varying cluster numbers (4, 6, 8). The C-index (mean ± std) is reported for five different cancer types (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD), demonstrating the model’s robustness to various patch classification approaches.

This table presents the results of the ProtoSurv model using three different tissue category settings: Detailed Tissue Category (DTC), Coarse Tissue Category (CTC), and Prior Tissue Category (PTC). The PTC setting uses tissue categories selected based on prior knowledge of prognosis-related tissues. The table shows the C-index (mean ± std) achieved by the model under each tissue category setting across five different cancer datasets (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD). This demonstrates the impact of incorporating prior knowledge about relevant tissue types in improving the model’s performance.

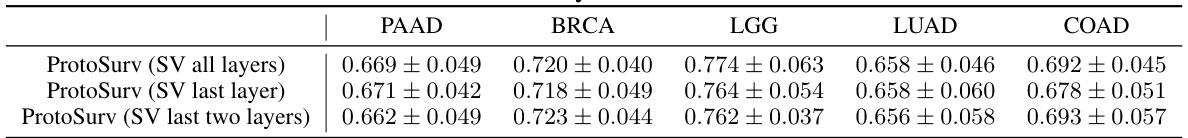

This table presents the ablation study results of using different numbers of layers (all, last, last two) in the Structure View of the ProtoSurv model. The C-index (mean ± std) for survival prediction performance is shown for five different cancer types (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD). It demonstrates how the number of layers used to extract features from the Structure View affects the model’s performance.

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of classification errors on the overall performance. It shows the C-index (mean ± std) for ProtoSurv and two variations: 20% and 30% of node categories are randomly generated. The results demonstrate the model’s robustness against classification errors.

This ablation study evaluates the impact of compatibility loss (Lcomp) and orthogonality loss (Lortho) on the model’s performance across five cancer datasets (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD). Different hyperparameter settings for α (Lcomp) and β (Lortho) were tested, ranging from 0 to 0.1. The results show that incorporating both losses consistently improves the model’s performance compared to using only the Cox loss.

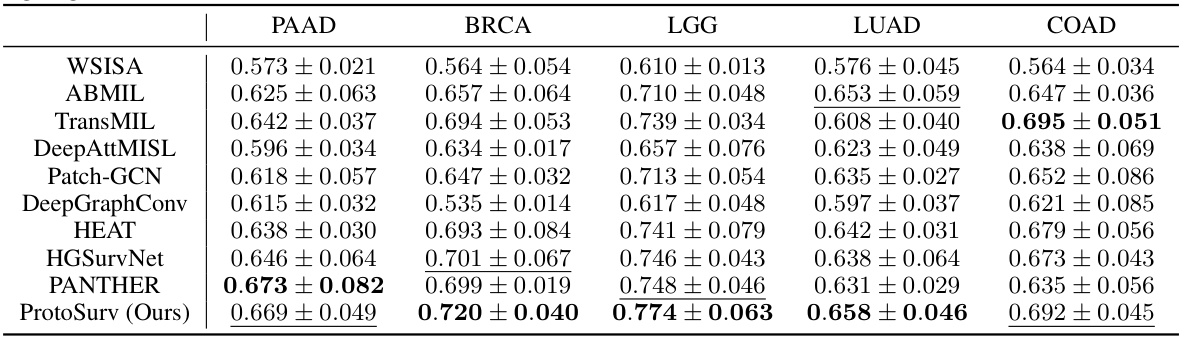

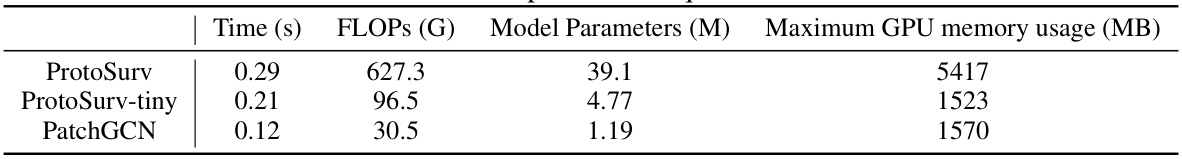

This table presents the computational resource usage of the proposed model, ProtoSurv, its lightweight version, ProtoSurv-tiny, and the baseline model, PatchGCN. Metrics include inference time, floating point operations (FLOPs), model parameters (in millions), and maximum GPU memory usage (in MB). The results provide a quantitative comparison of the computational efficiency across different models.

This table presents the performance of the ProtoSurv-tiny model (a smaller version of the main model) across five different cancer datasets (PAAD, BRCA, LGG, LUAD, COAD). The results are presented as C-index (mean ± standard deviation). The C-index measures the accuracy of the model in predicting survival time ranking.

Full paper#