↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

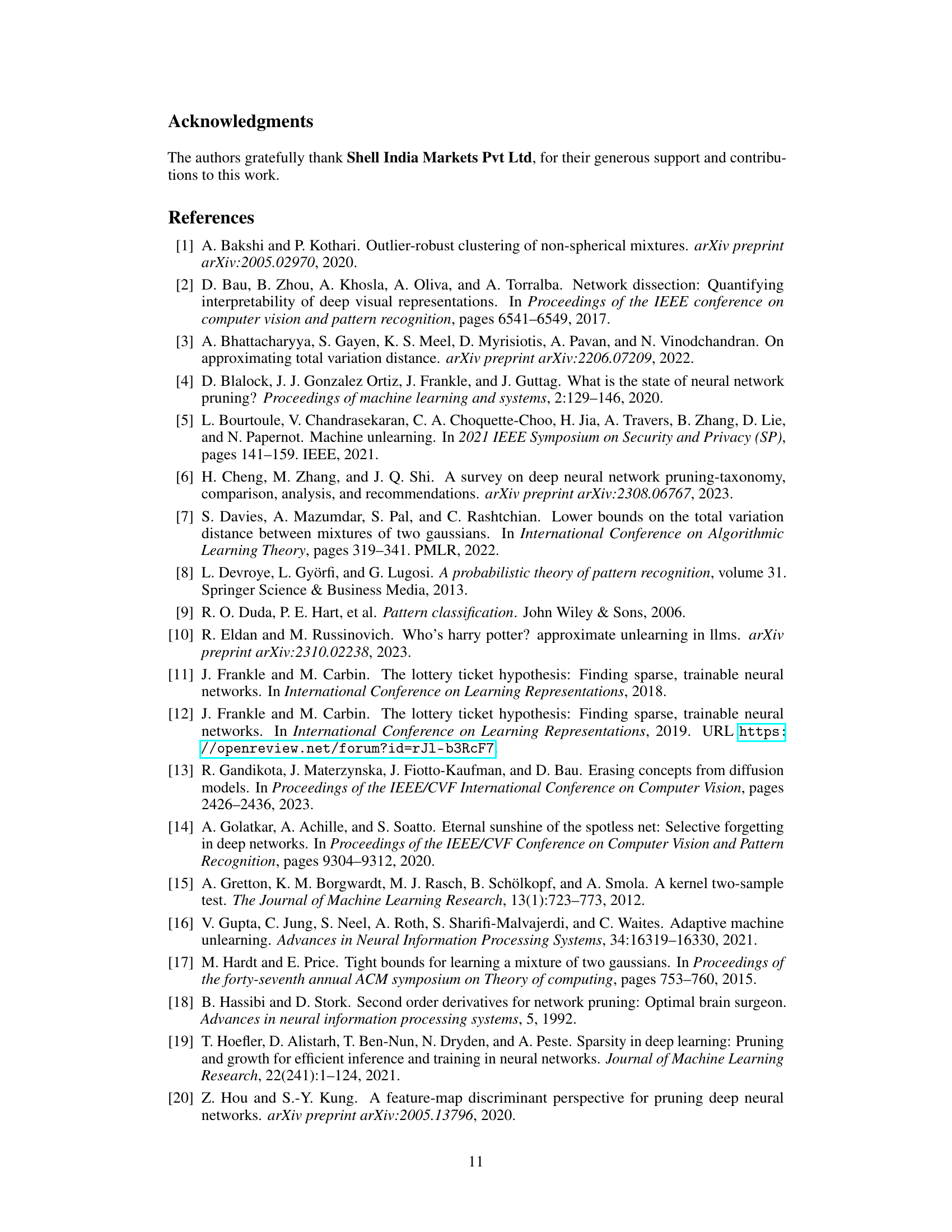

TL;DR#

Many machine learning tasks require modifying model components, e.g., for structured pruning or class-specific forgetting. Identifying the most influential components is crucial but challenging. Existing methods often rely on restrictive assumptions or access to training data, limiting their applicability. This poses a problem as accessing training data can often be impractical.

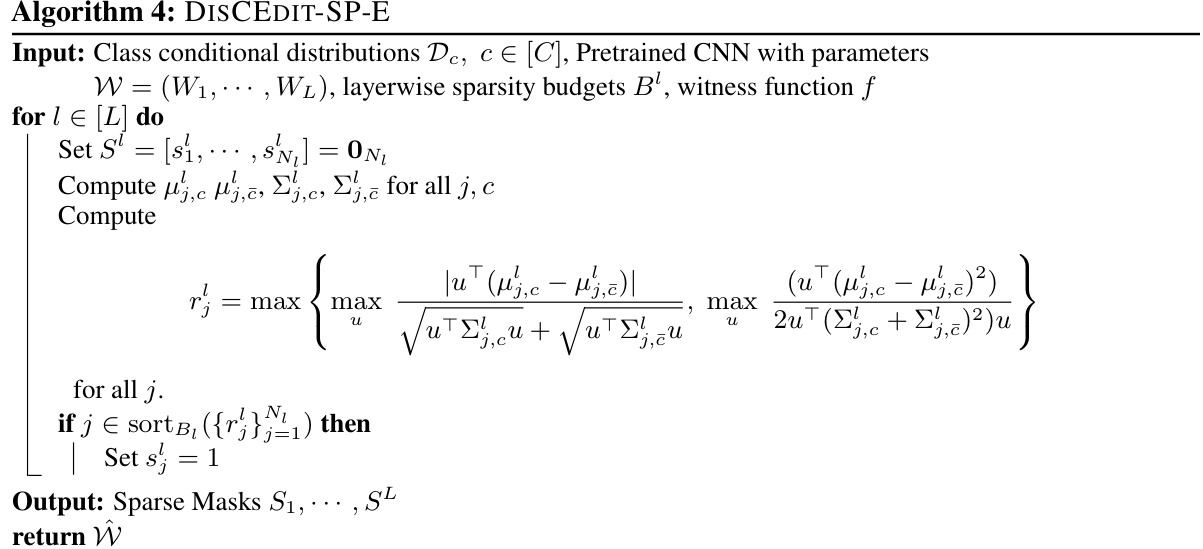

The paper introduces DISCEDIT, a novel distributional approach using witness function-based lower bounds on Total Variation (TV) distance to identify discriminative components without training data or strong assumptions. DISCEDIT yields two algorithms: DISCEDIT-SP for structured pruning and DISCEDIT-U for class unlearning. Empirical results demonstrate significant performance gains in terms of sparsity and forgetting rates on various datasets and architectures. This work overcomes limitations of previous methods by providing a distributionally agnostic approach to model editing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neural network optimization and model editing. It provides novel, tractable methods for identifying key model components influencing predictions, enabling efficient pruning and class-specific unlearning without relying on training data or loss functions. This opens exciting avenues for improving model efficiency, enhancing privacy, and understanding model behavior.

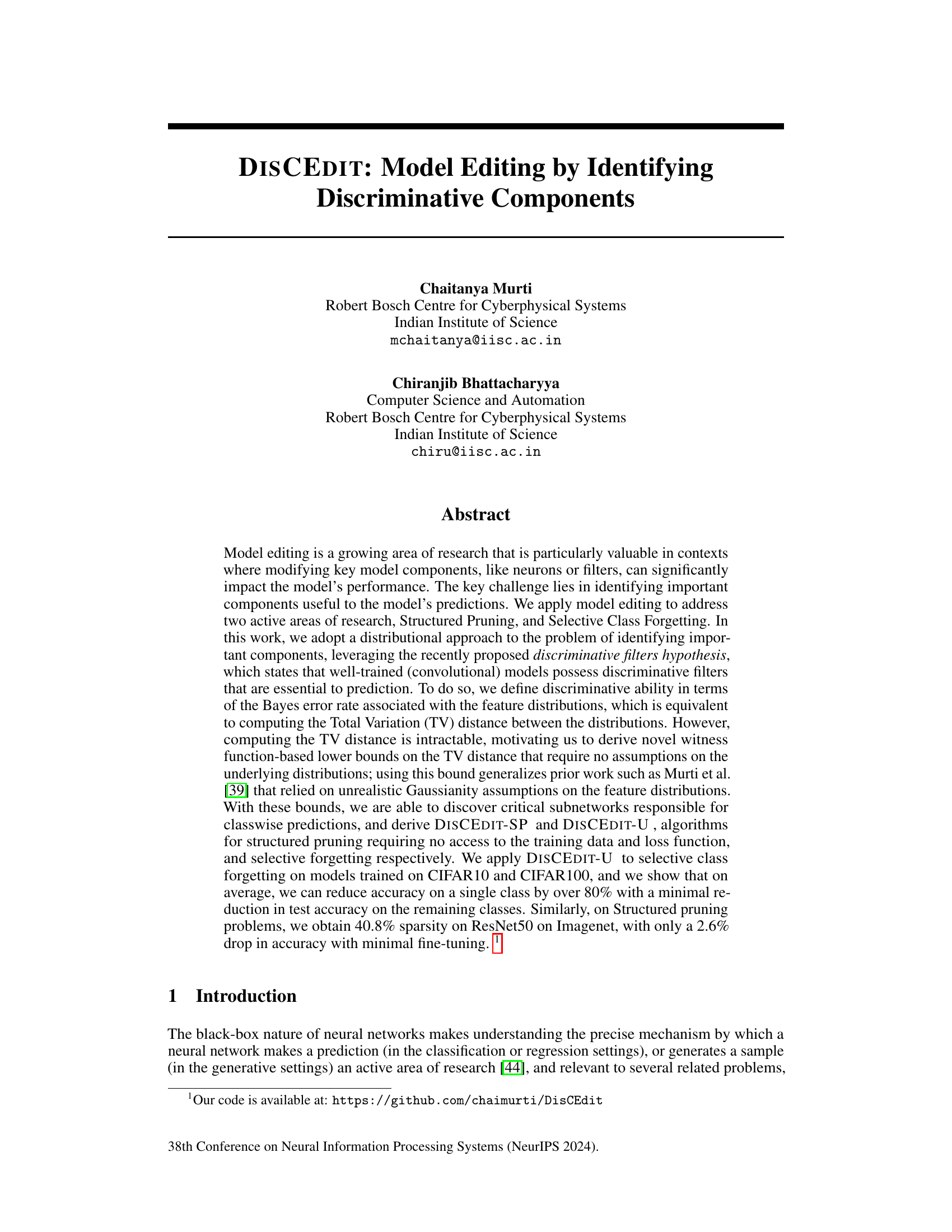

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework. It shows how identifying discriminative components (neurons or filters) is used for two model editing tasks: structured pruning and class-wise unlearning. For structured pruning, the goal is to identify non-discriminative components and remove them, reducing model size with minimal accuracy loss. For class-wise unlearning, the goal is to identify components responsible for a specific class and remove them, effectively ‘forgetting’ that class. The diagram highlights the use of lower bounds to identify these components, which is a core contribution of the paper.

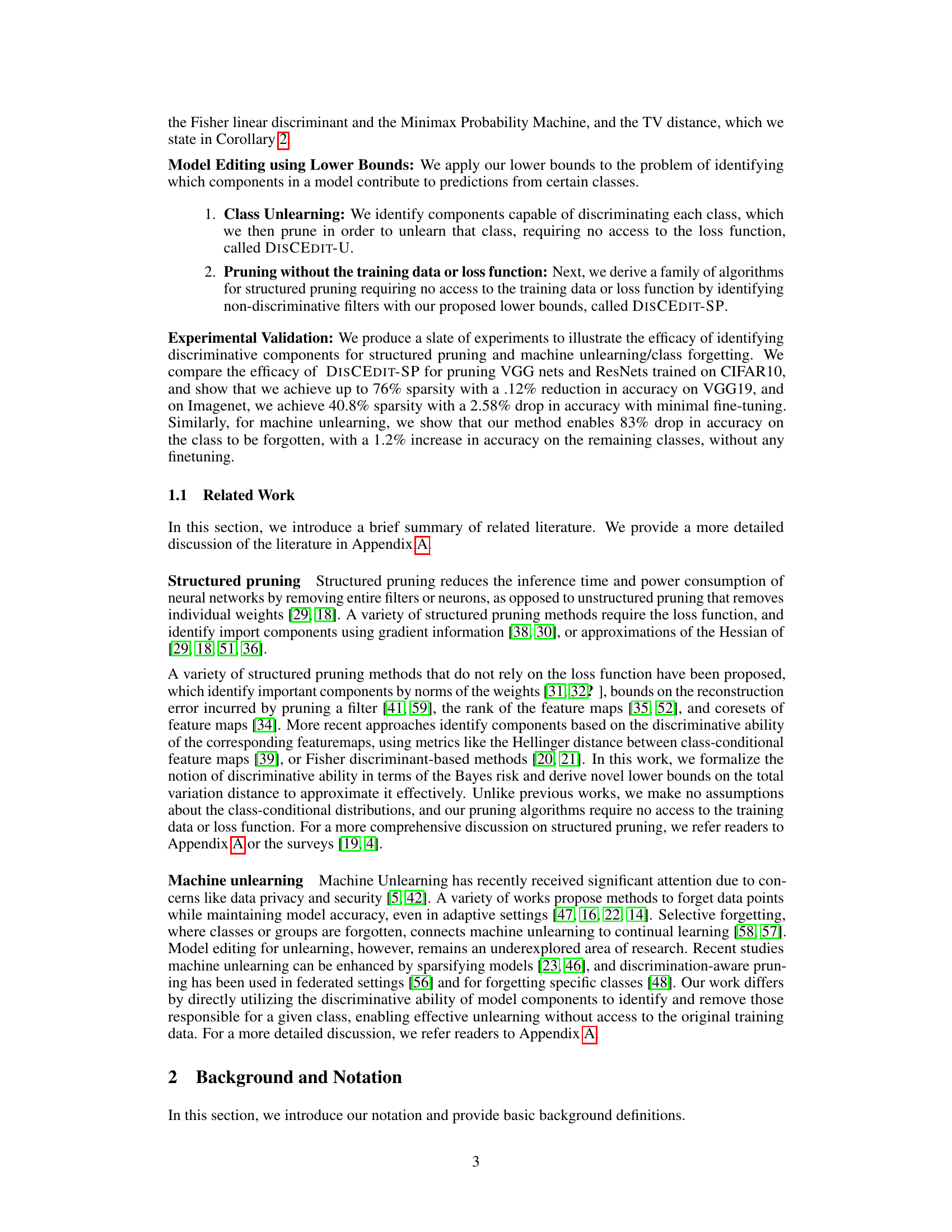

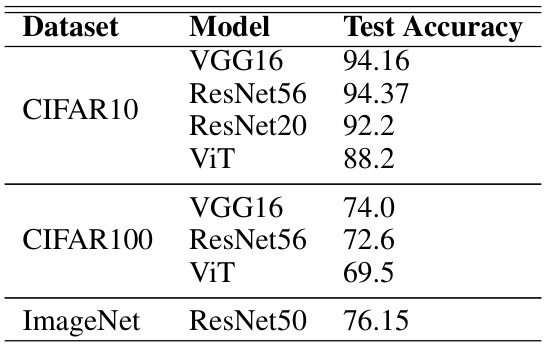

This table summarizes the results of class unlearning experiments using the DISCEDIT-U algorithm. It shows the accuracy drop (FA) on the target class to be forgotten and the accuracy drop (RA) on the remaining classes. The results are presented both with and without fine-tuning (NoFT and FT, respectively) after applying the algorithm to different models (VGG16, ResNet56, ResNet20, ViT) trained on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. Baselines from the literature are also included for comparison.

In-depth insights#

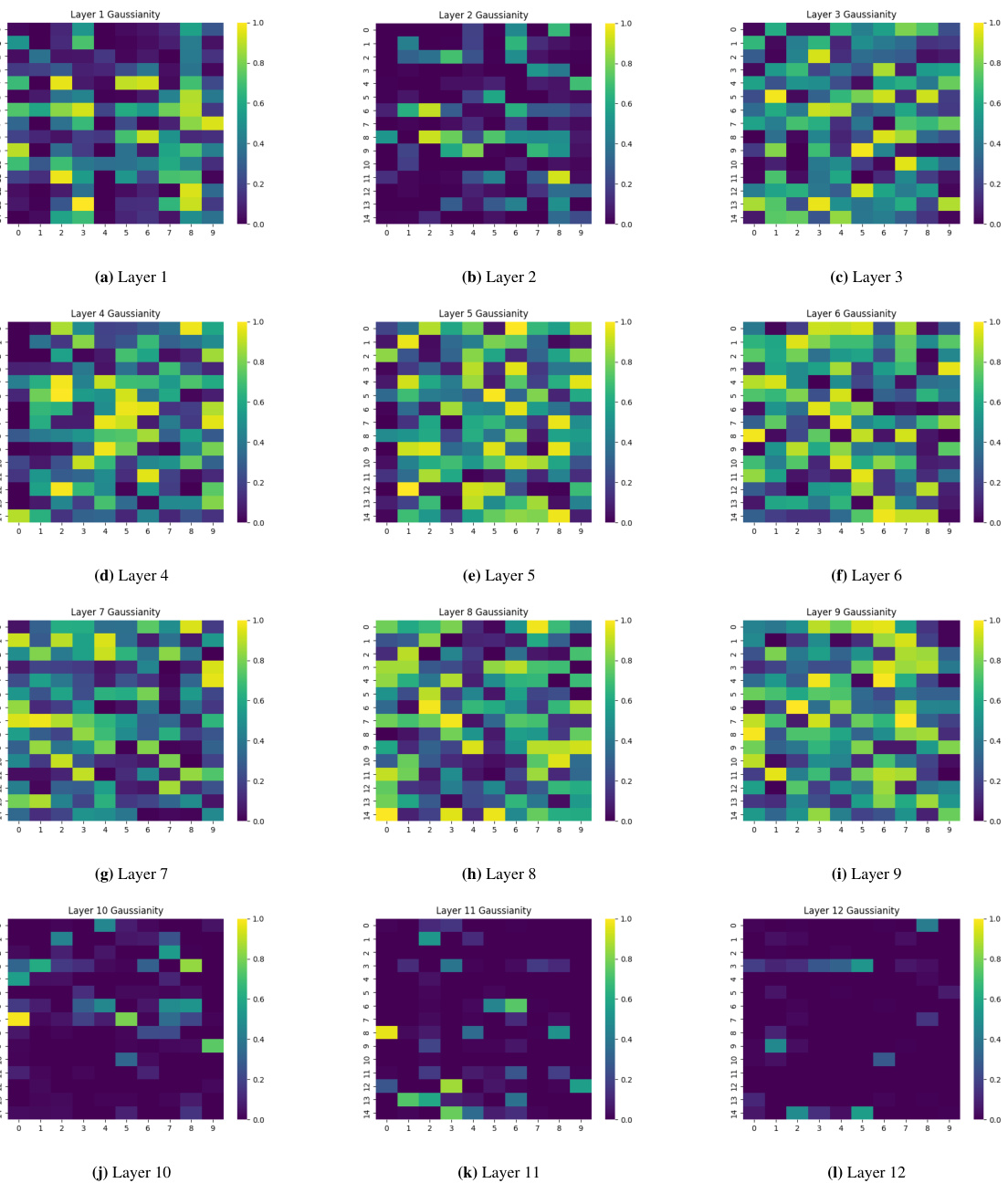

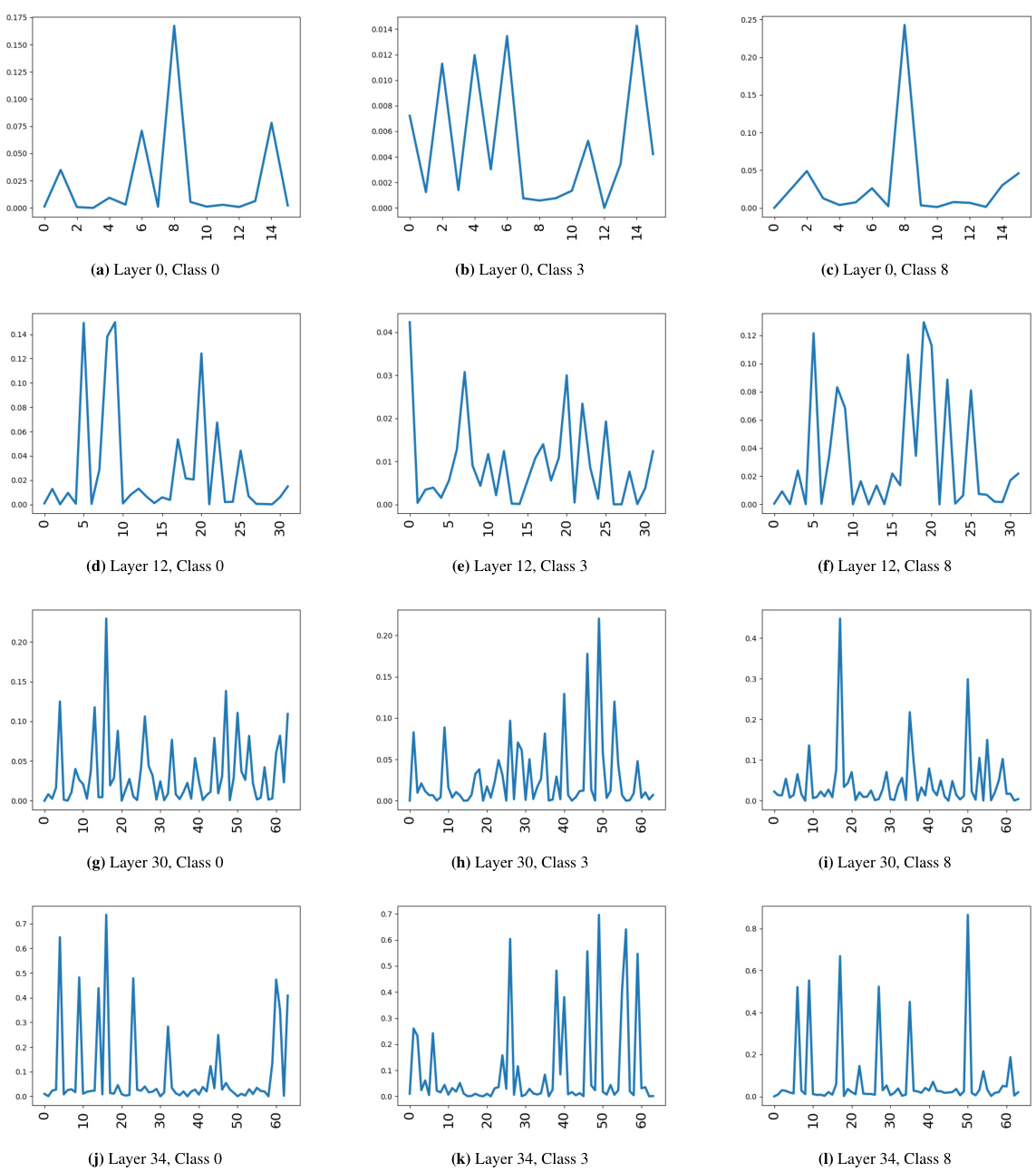

Discriminative Filters#

The concept of “discriminative filters” in the context of a research paper likely revolves around the idea of identifying specific filters or neurons within a neural network that are particularly effective at distinguishing between different classes in a classification task. These filters are crucial for the model’s ability to make accurate predictions. The research probably investigates methods to detect these filters, perhaps by analyzing feature map distributions or employing other techniques to quantify their importance. A key aspect would likely involve developing a metric to measure a filter’s discriminative power, which could be based on information-theoretic measures or the separation of class-conditional distributions. The practical implications might center on using this information for model compression (e.g., pruning less important filters) or enhancing interpretability by highlighting the parts of the network most responsible for specific classification decisions. The research could also consider how to address challenges like the high dimensionality of feature maps or the computational cost associated with identifying discriminative filters. Ultimately, the aim is likely to provide novel methods and algorithms for improving model efficiency and interpretability. This could include developing algorithms for pruning, knowledge distillation or network visualization techniques focusing on these discriminative features. This is a significant area of research as it bridges model interpretability and efficiency.

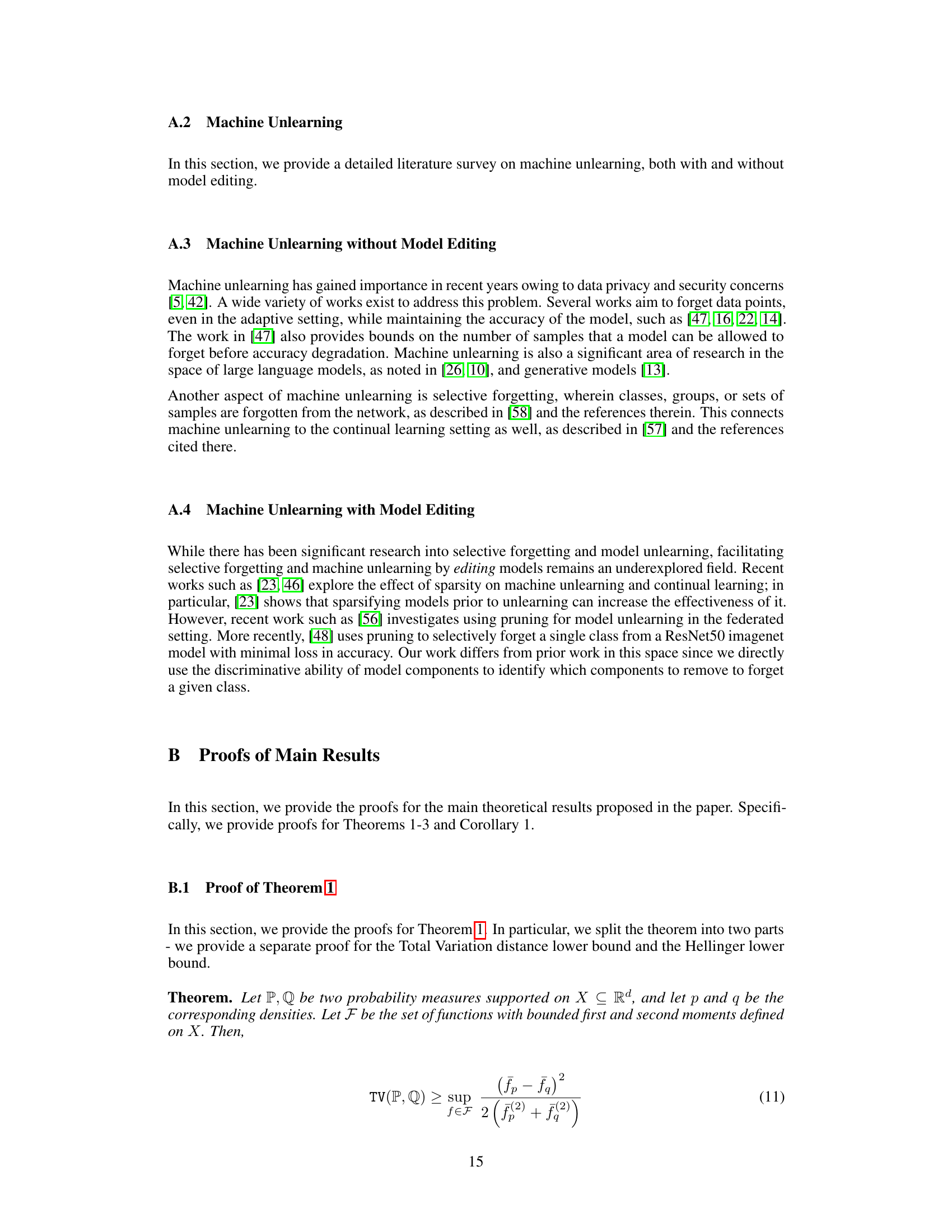

Model Editing#

Model editing, as discussed in the paper, presents a powerful paradigm shift in how we interact with and improve machine learning models. Instead of retraining entire models, it focuses on precisely modifying specific components, such as neurons or filters, to achieve desired changes in model behavior. This targeted approach offers several key advantages: it’s significantly more efficient than retraining, it allows for fine-grained control over model adjustments, and importantly, it facilitates model understanding by revealing which parts are responsible for specific predictions. The core challenge, addressed via a novel distributional approach, is identifying these crucial components; the paper introduces a method to efficiently identify such elements without relying on access to training data or the loss function, thus enhancing model explainability and practicality. This is particularly valuable for tasks like structured pruning, where components deemed less important are selectively removed to optimize resource usage, and class-wise unlearning, where specific knowledge related to a certain class is removed to safeguard privacy or update existing knowledge. The proposed methods highlight a promising direction for building more efficient, interpretable, and adaptable machine learning systems.

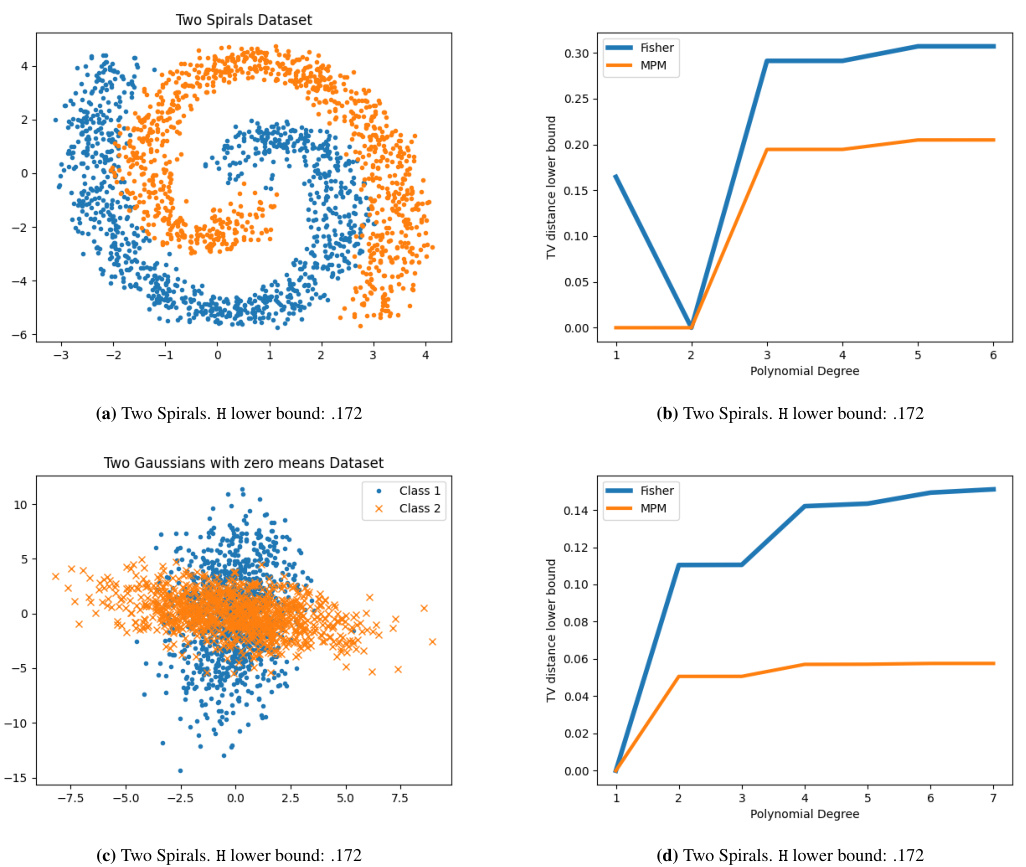

Lower Bounds#

The section on ‘Lower Bounds’ is crucial because it addresses the computational intractability of directly calculating the Total Variation (TV) distance between feature distributions. The authors cleverly circumvent this by deriving novel, tractable lower bounds on the TV distance. These bounds are significant because they avoid unrealistic assumptions about the underlying distributions (like Gaussianity), making the approach more generally applicable. The use of witness functions is a key element here, enabling the derivation of bounds that only require access to the moments of the distributions. This is a powerful technique as it sidesteps the need for full distributional information, which is often unavailable or computationally expensive to obtain. The connection established between these lower bounds and classical discriminant-based classifiers (Fisher Linear Discriminant, Minimax Probability Machine) further enhances the practical value of the work, bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and readily-available classification methods. The robustness of the lower bounds to moment estimation errors is also a vital contribution, highlighting the practical applicability of the theoretical developments.

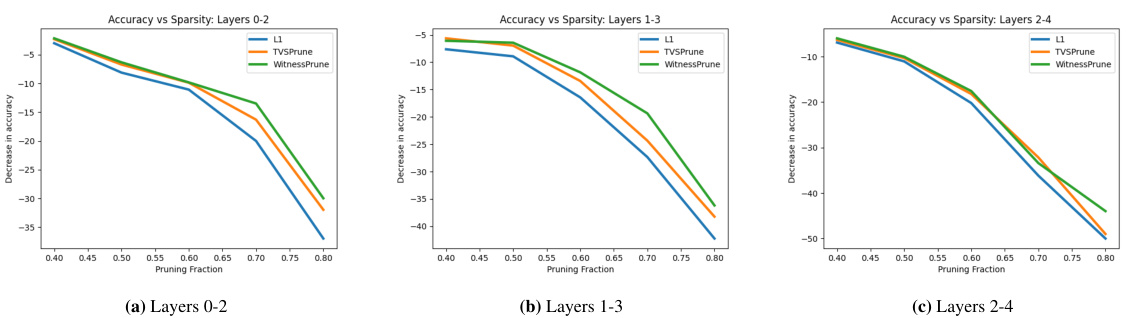

Pruning Methods#

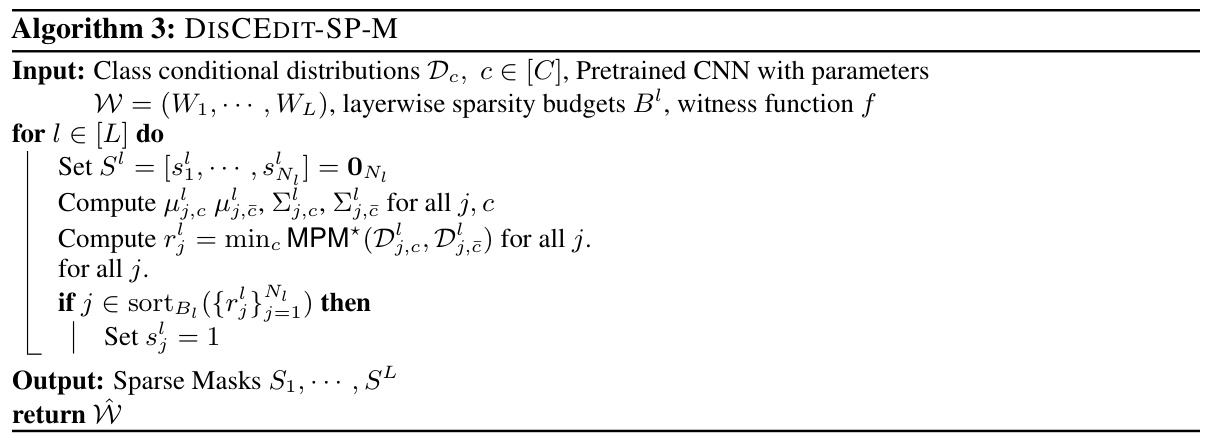

Pruning methods in neural networks aim to reduce model complexity and improve efficiency by selectively removing less important components. Structured pruning removes entire filters or neurons, offering better computational savings than unstructured pruning, which removes individual weights. Effective pruning strategies often require balancing sparsity with accuracy. Loss function-based methods use gradient information or Hessian approximations to guide the pruning process, identifying important components based on their contribution to the loss. However, these methods require access to training data and the loss function, limiting their applicability in certain scenarios. Distributional approaches, on the other hand, analyze the distributions of feature maps to identify discriminative filters essential for prediction, offering a loss-function-free alternative for pruning. The choice of witness function plays a crucial role in distributional pruning methods, influencing the tightness of the lower bound on the total variation distance used to quantify discriminative ability. Ultimately, the optimal pruning method is context-dependent, and careful consideration must be given to the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents exciting avenues for extending this research. Extending the model editing techniques to generative models is a crucial next step, as it would significantly impact image generation and other generative tasks. Investigating the applicability of the method to other editing tasks such as debiasing would broaden its impact and address pressing concerns in fairness and bias mitigation. The current focus on classifier models limits the broader impact, therefore, exploring generative model applications will be important. Furthermore, delving deeper into the limitations of lower bounds on TV distance is essential, potentially through developing tighter bounds or exploring alternative metrics to quantify discriminative ability. Addressing the challenges posed by high-dimensional data where the number of samples is significantly lower than the dimensionality of data, remains a critical area for future improvement. Finally, a comprehensive study focusing on the impact of various witness functions would provide insights into optimizing DISCEDIT for different applications.

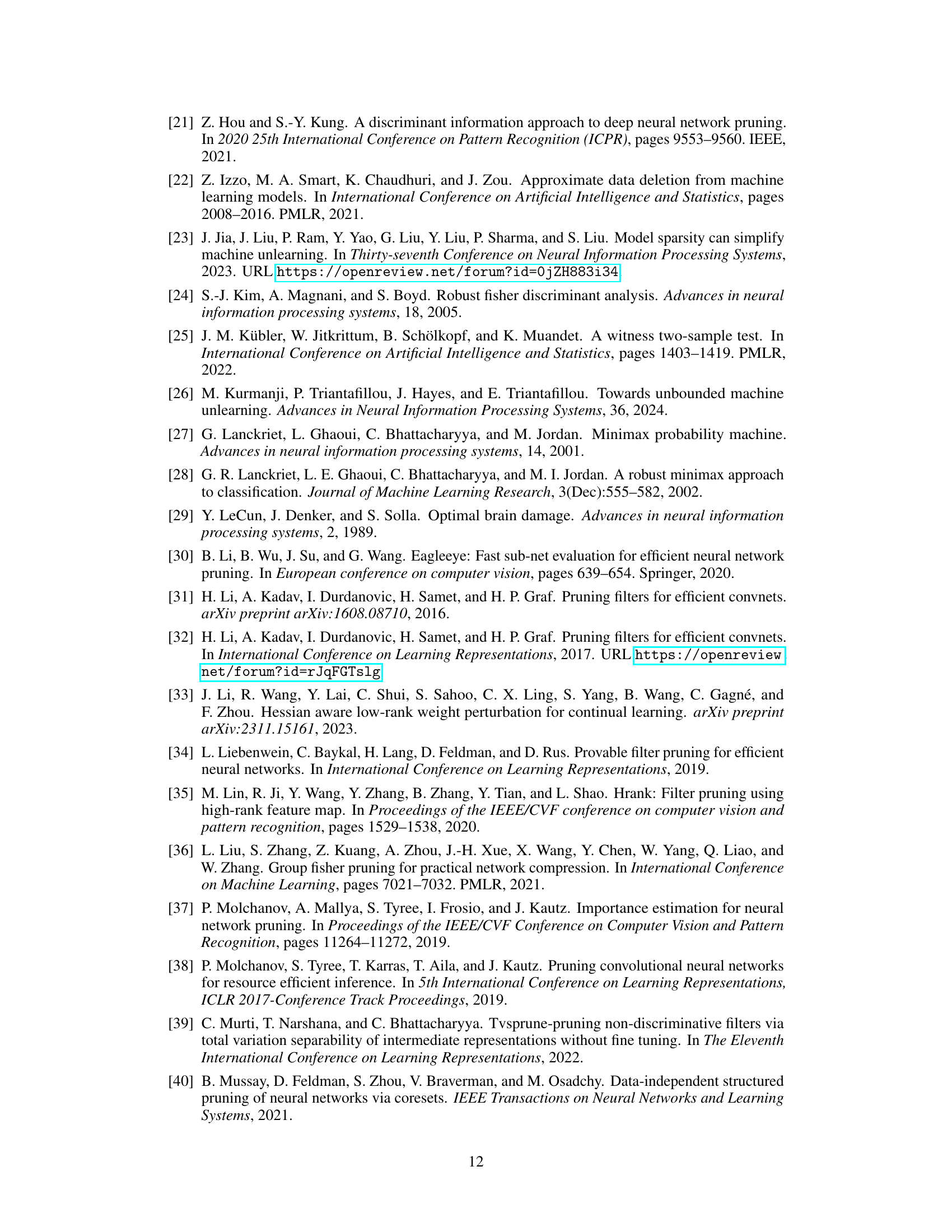

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework for model editing. It shows how the algorithm identifies discriminative components (neurons, filters, etc.) within a neural network model that are responsible for making predictions for specific classes or the overall model accuracy. This information is then used for two model editing tasks: 1. Classwise Unlearning: Components most important to a particular class are identified and pruned to selectively forget that class, effectively reducing the model’s accuracy for that class while maintaining accuracy for others. 2. Structured Pruning: Components important to no class (non-discriminative components) are identified and removed, improving model efficiency by reducing size and computation cost with minimal impact on overall accuracy. The diagram highlights the steps involved: identifying discriminative components, using those components for classwise unlearning or structured pruning and finally showing the pruned/modified model.

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework. It shows how discriminative components are identified using lower bounds on the TV distance, which are then used for either classwise unlearning or structured pruning. For classwise unlearning (unlearning a specific class), the components that are most discriminative for that class are pruned or masked. For structured pruning (improving efficiency overall), components that are not discriminative for any classes are removed. The goal of both is to edit the model while minimizing accuracy loss on the remaining classes.

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework for both model unlearning and structured pruning. It shows how identifying discriminative components (those crucial for class-wise predictions) allows for targeted editing of the model. In model unlearning, components discriminative for a specific class are pruned to make the model ‘forget’ that class. In structured pruning, nondiscriminative components (those not contributing significantly to any class prediction) are identified and pruned to reduce model size without substantial loss of accuracy. The process involves leveraging lower bounds on the Total Variation (TV) distance to identify these components.

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework’s approach to model editing. It highlights the process of identifying discriminative components (e.g., neurons, filters) within a neural network that are crucial for class-wise predictions. These components are then either pruned or masked for structured pruning, where the aim is to reduce model size with minimal accuracy loss across all classes, or for classwise unlearning, where the goal is to selectively remove components responsible for the predictions of a specific class.

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework. It shows how the method identifies discriminative components (e.g., filters in a convolutional neural network) that contribute significantly to class-wise predictions. These components are then used for two main model editing tasks: 1. Classwise Unlearning: Components highly discriminative for a specific class are pruned or masked, effectively making the model ‘forget’ that class. 2. Structured Pruning: Components that are not discriminative for any class are removed to achieve model sparsity and efficiency. The process of identifying these discriminative components involves analyzing the distributional properties of feature maps generated by each component. Lower bounds on the Total Variation (TV) distance between class-conditional feature distributions are used to quantify the discriminative ability of each component.

This figure illustrates the DISCEDIT framework, which identifies discriminative components in neural networks for model editing tasks such as structured pruning and class-wise unlearning. It shows how identifying these components through lower bounds on the total variation distance allows for the selective pruning or masking of components to achieve the desired effects of either reduced model size (structured pruning) or selective forgetting of specific class information (class-wise unlearning).

More on tables

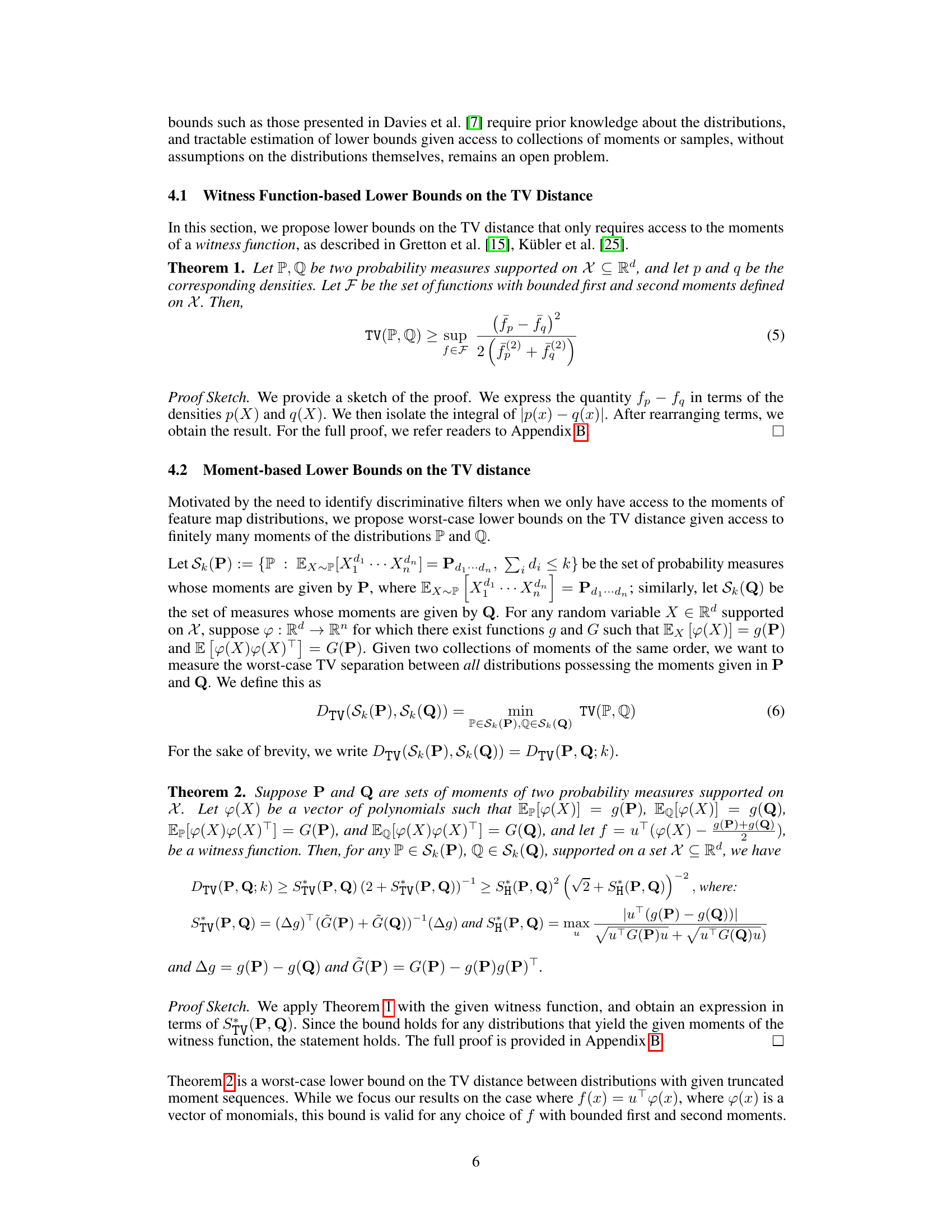

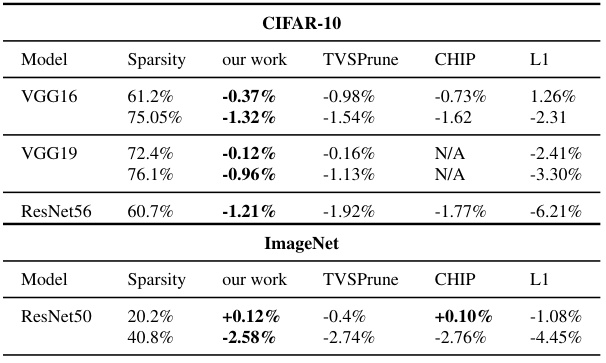

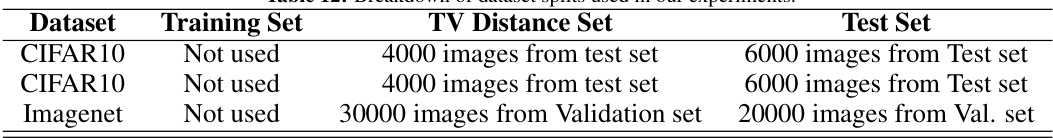

This table presents the results of structured pruning experiments using DISCEDIT-SP on CIFAR10 and ImageNet datasets. It compares the accuracy drop after pruning (with and without fine-tuning) using DISCEDIT-SP against three baselines: TVSPrune [39], CHIP [52], and L1 pruning. The table shows the sparsity achieved (percentage of parameters removed) and the resulting accuracy drop for different models and sparsity levels. Positive accuracy changes indicate improved accuracy after pruning.

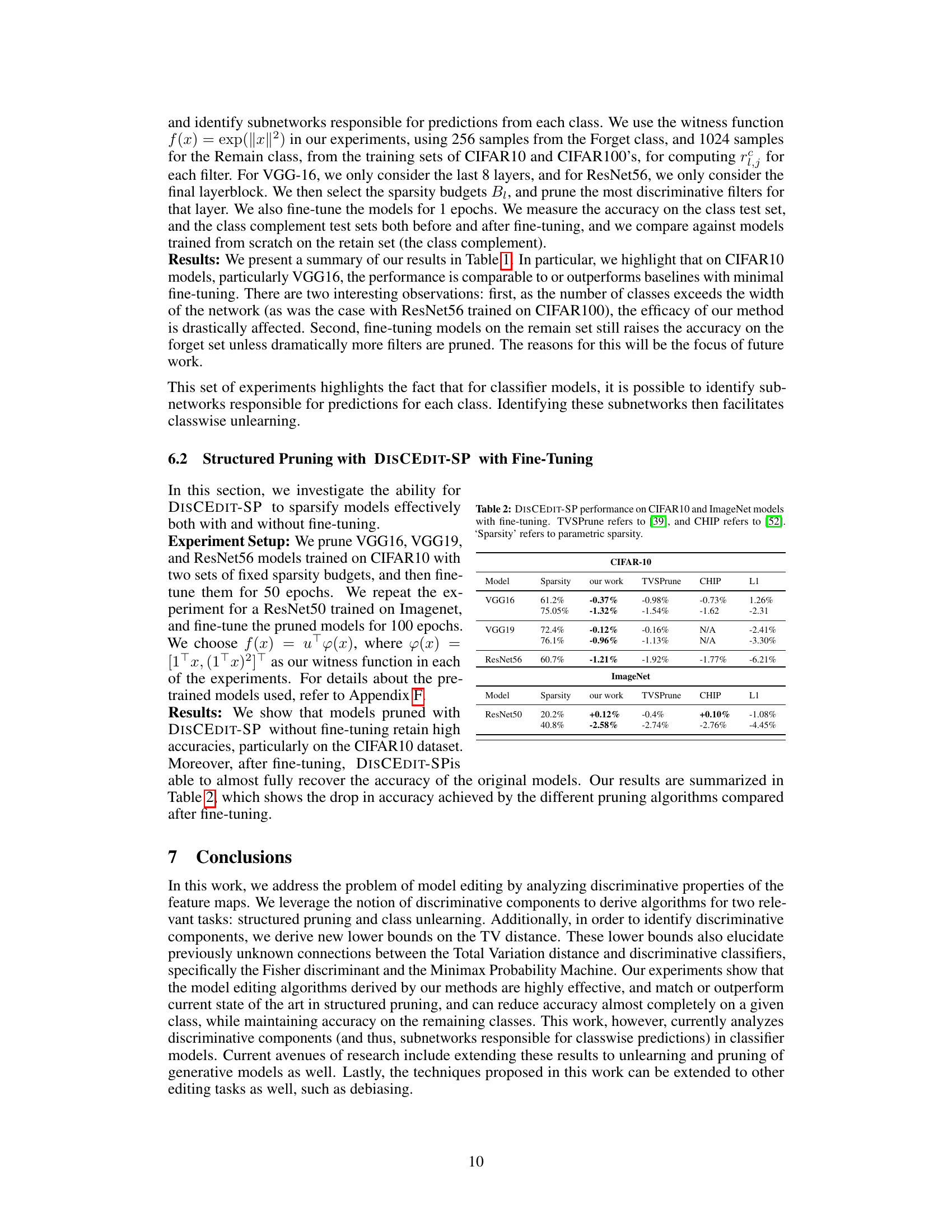

This table compares the computational cost and storage requirements for different witness functions used in the DISCEDIT-SP and DISCEDIT-U algorithms. It breaks down the costs for pruning (P) and unlearning (U) tasks, considering the number of filters (L), classes (C), and feature dimensions (n). The table shows that the computational cost and storage increase with the complexity of the witness function.

This table summarizes the results of class unlearning experiments using the DISCEDIT-U algorithm. It compares the accuracy drop on the forgotten class (FA) and the accuracy drop on the remaining classes (RA) under different conditions. The conditions include using DISCEDIT-U without fine-tuning (NoFT) and with one epoch of fine-tuning (FT), along with different pruning ratios for each model architecture (VGG16, ResNet56, ResNet20, ViT). The results are averages over ten trials.

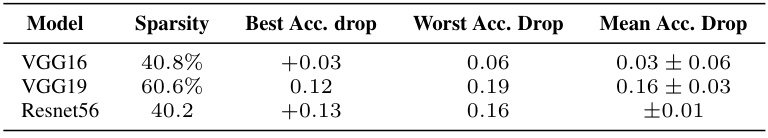

This table presents ablation studies on 10 different instances of models trained on CIFAR10 to demonstrate the robustness of DISCEDIT-SP across various model architectures. The results show the sparsity achieved, the best and worst accuracy drops observed across all models, and the mean accuracy drop with standard deviation across the models. The table indicates that DISCEDIT-SP consistently performs well across different model types after pruning and fine-tuning.

This table shows the results of ablation experiments conducted on CIFAR100. The goal was to evaluate the robustness of DISCEDIT-SP across multiple model instantiations. Ten different models were used. The table reports the sparsity achieved, the best and worst accuracy drops observed across the different runs and the mean accuracy drop and its standard deviation.

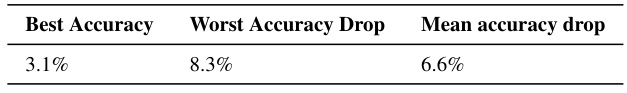

This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on ResNet50 models trained on the ImageNet dataset. Three different model instantiations were used, and the table shows the average, best, and worst accuracy drops after applying the DISCEDIT-SP algorithm. This demonstrates the robustness of the algorithm across different model initializations.

This table presents the accuracy drop after applying structured pruning using DISCEDIT-SP without fine-tuning. It compares the accuracy drop of DISCEDIT-SP with three other methods: TVSPrune [39], CHIP [52], and L1-based pruning, across different models (VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50) and datasets (CIFAR10, ImageNet) with varying sparsity levels. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of DISCEDIT-SP in achieving high sparsity while maintaining accuracy.

This table presents the results of applying DISCEDIT-SP for structured pruning on CIFAR10 models with high sparsity (over 80% of parameters pruned). It compares the accuracy drop (with and without fine-tuning) of DISCEDIT-SP against other methods such as CHIP and TVSPrune. The results demonstrate that even with extremely high sparsity, DISCEDIT-SP maintains competitive accuracy compared to the other algorithms.

This table summarizes the results of class unlearning experiments using the DISCEDIT-U algorithm. It compares the accuracy drop on the forgotten class (FA) and the remaining classes (RA) under different conditions: no fine-tuning (NoFT) and with fine-tuning (FT). Baselines from prior work [23] are also included for comparison. The table highlights that DISCEDIT-U achieves significant accuracy reduction on the target class while maintaining high accuracy on the rest, even without fine-tuning. Different model architectures (VGG16, ResNet56, ResNet20, ViT) and datasets (CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100) are used to demonstrate the robustness of the method.

This table shows the test accuracy achieved by a custom Vision Transformer (ViT) model on the CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 datasets. The ViT model is a custom model trained by the authors and used in several experiments in the paper. The table provides baseline accuracies against which the results of various model editing experiments can be compared.

This table presents the test accuracy achieved by different models (VGG16, ResNet56, ResNet20, ViT) on three different datasets (CIFAR10, CIFAR100, and ImageNet). The results show the baseline performance of the models used in the subsequent experiments for structured pruning and class unlearning.

This table presents the results of class unlearning experiments using DISCEDIT-U. It shows the average accuracy drop (FA) on the forgotten class and the average accuracy drop (RA) on the remaining classes. Results are given for models with and without fine-tuning, comparing the performance of DISCEDIT-U against existing methods (RA (IU) [23]). The table also shows the percentage of weights pruned in each model for both fine-tuned and non-fine-tuned scenarios.

Full paper#