TL;DR#

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a powerful technique for determining protein structures. However, current methods struggle to effectively model samples with diverse compositions and conformations, particularly in complex biological mixtures like cellular lysates. Analyzing these complex samples is crucial for understanding cellular processes, but existing techniques fall short; they either handle conformational or compositional heterogeneity sequentially or resort to strong assumptions about the structural states. This limits their ability to provide accurate structural insights, particularly for biomolecules undergoing large conformational transitions.

The researchers introduce Hydra, a novel approach that utilizes a mixture of neural fields. This innovative method enables the simultaneous inference of protein structures, orientations, compositional classes, and conformational states. By employing a new likelihood-based loss function, Hydra adeptly navigates the complexities of heterogeneous samples, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy in both synthetic and experimental data. Hydra’s ability to fully reconstruct both conformational and compositional variability fully ab initio represents a significant advancement, expanding the capabilities of cryo-EM and paving the way for the study of increasingly intricate biological samples.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for cryo-EM researchers as it presents Hydra, a novel method for tackling the complex issue of heterogeneous sample reconstruction. Hydra’s ability to simultaneously handle compositional and conformational heterogeneity pushes the boundaries of what’s possible in cryo-EM, opening doors to analyze more intricate biological systems and significantly improving structural resolution and accuracy. This will be particularly valuable for studying complex cellular environments or macromolecular assemblies exhibiting high flexibility, boosting the field’s capability to reveal the intricacies of various biological mechanisms.

Visual Insights#

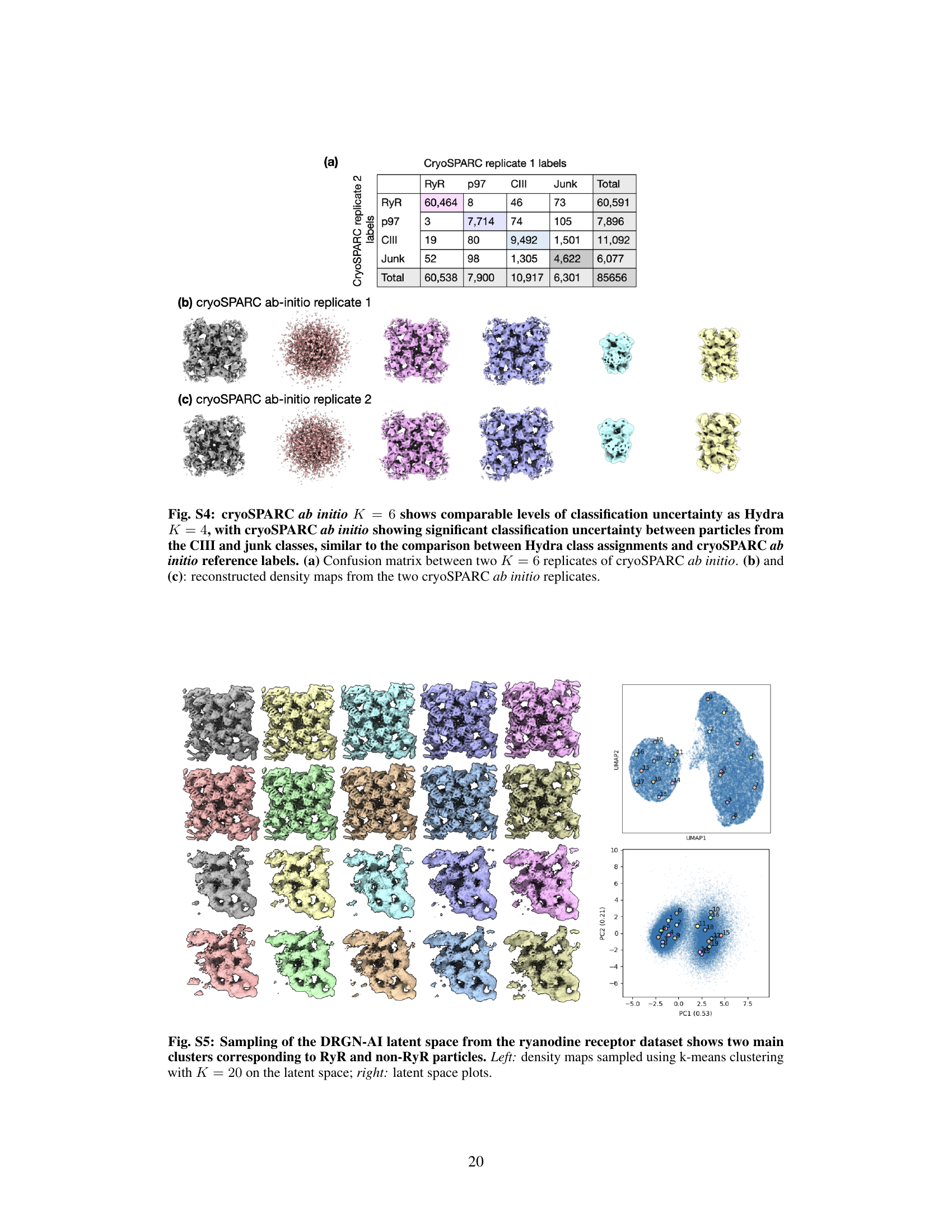

🔼 This figure provides a visual summary of the Hydra method for heterogeneous reconstruction in cryo-EM. Panel (a) illustrates the concept of approximating the space of possible density maps as a union of low-dimensional manifolds, each representing a compositional state (k). Panel (b) shows the optimization pipeline where conformations, poses, class probabilities, and neural fields are jointly optimized to maximize the likelihood of the observed images.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of Hydra. (a) Schematic representation of the space of energetically plausible density maps in a heterogeneous cryo-EM dataset. We approximate this space with a finite union of low-dimensional manifolds. The compositional states (or classes) are labeled by k. The 'conformation' within class k refers to intrinsic coordinates within the k-th manifold. (b) Optimization pipeline. The conformations, poses, class probabilities and neural fields are optimized such as to maximize the likelihood of the observed images ('picked particles') under the model described in Section 3.3.

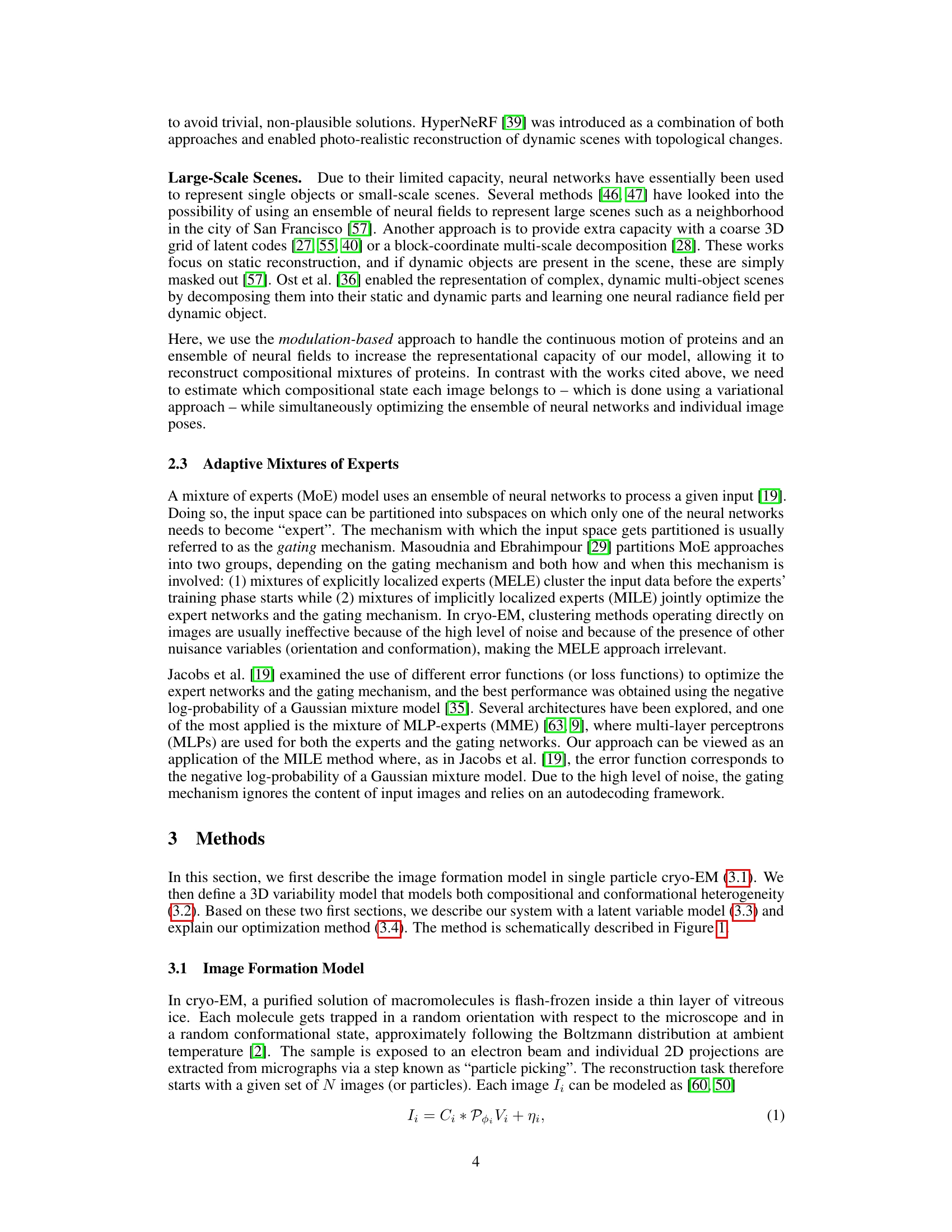

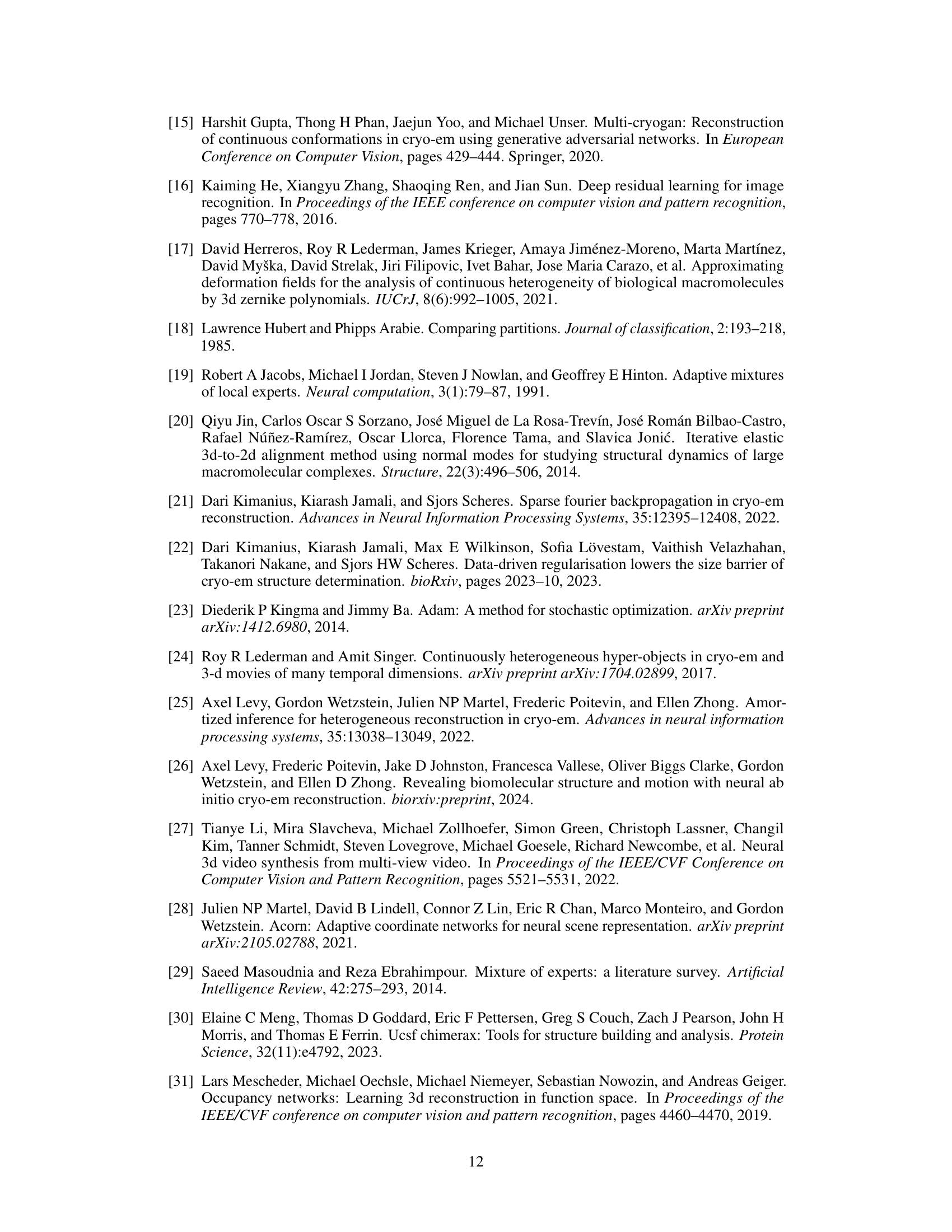

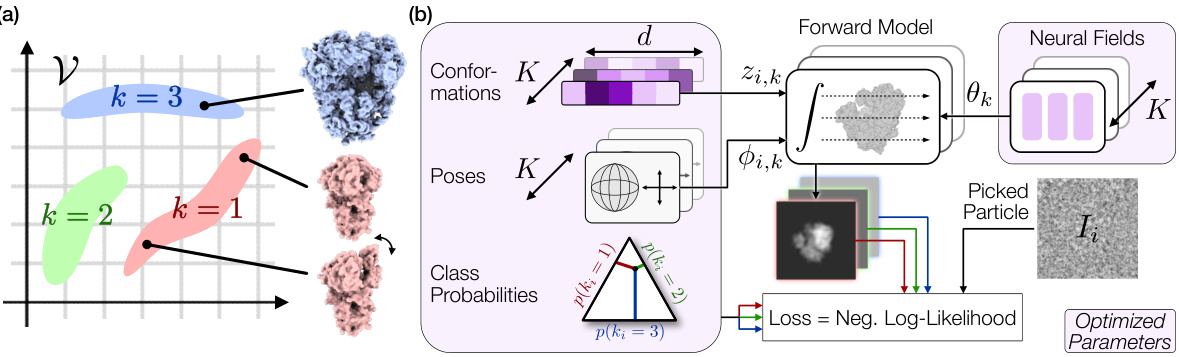

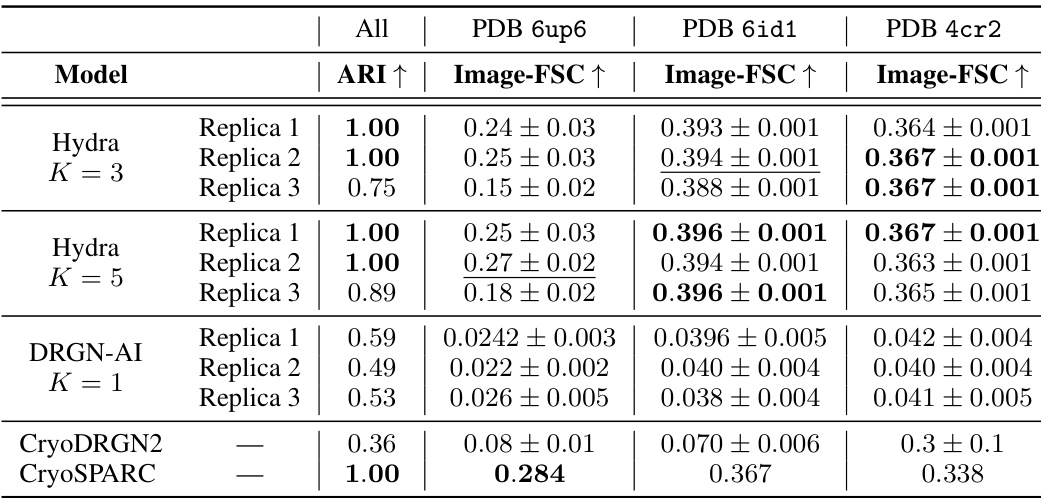

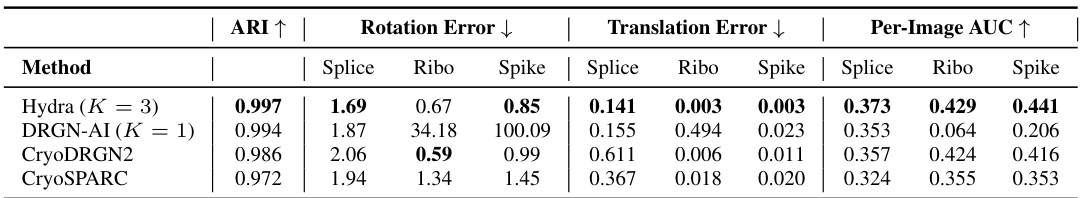

🔼 This table compares the performance of Hydra against other state-of-the-art neural-based methods for resolving compositional heterogeneity in cryo-EM datasets. The comparison focuses on a challenging synthetic dataset. Performance is measured by two metrics: the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which quantifies the classification accuracy, and the mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curve, which reflects reconstruction quality. Higher ARI and FSC values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method’s reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

In-depth insights#

Cryo-EM Heterogeneity#

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has revolutionized structural biology, but faces challenges in handling the inherent heterogeneity of biological samples. Cryo-EM heterogeneity refers to the presence of multiple conformations or compositions within a sample, making it difficult to obtain a single, representative 3D structure. Two main types exist: conformational heterogeneity, where a single macromolecule adopts different shapes, and compositional heterogeneity, where the sample is a mixture of multiple macromolecules. Advanced cryo-EM methods attempt to address this by incorporating probabilistic models to disentangle different states or employing neural networks to represent continuous conformational changes. However, fully addressing both conformational and compositional heterogeneity simultaneously remains a significant challenge, especially in complex samples like cellular lysates. New methods, such as mixture models and neural fields, aim to overcome these limitations by enabling the simultaneous reconstruction of multiple structures and their varying conformational states, revealing a richer and more biologically relevant picture than previously possible.

Hydra’s Neural Fields#

Hydra’s neural fields represent a novel approach to heterogeneous cryo-EM reconstruction by modeling the diverse macromolecular structures within a sample as arising from a mixture of K neural fields. This method is particularly powerful because it directly addresses both conformational and compositional heterogeneity simultaneously and ab initio, eliminating the limitations of sequential methods. Each neural field implicitly represents a compositional class and is capable of modeling the continuous conformational variations within that class. The mixture model, combined with a likelihood-based loss function, allows the algorithm to effectively learn the orientations, conformations, and class assignments of the particles within the sample. This results in a significant improvement in the accuracy and expressiveness of cryo-EM reconstructions, as demonstrated in both synthetic and experimental datasets. The key advantage lies in the ability to handle complex mixtures of proteins with substantial conformational variability, surpassing the capabilities of previous methods. This advance has significant implications for expanding the applicability of cryo-EM to increasingly intricate biological samples.

Ab Initio Approach#

An ab initio approach, in the context of a research paper, signifies a method that starts from fundamental principles without relying on pre-existing data or models. This is particularly valuable when dealing with complex systems where prior information is limited or unreliable, such as in heterogeneous cryo-electron microscopy. The strength of this approach is its ability to discover novel structures and configurations without bias from existing assumptions. However, the ab initio method typically involves a high computational cost and requires robust algorithms to handle inherent noise and ambiguities. Successful implementation often demands advanced techniques like neural networks or other machine learning methods to effectively extract meaningful information from the raw data. A key challenge is finding a balance between model complexity and robustness to noise, ensuring the model accurately represents the underlying phenomena and avoids overfitting. Careful validation and comparison with established methods are necessary to confirm the efficacy and reliability of the ab initio approach. Despite these challenges, the rewards are significant – the potential to uncover unexpected discoveries and gain a deeper understanding of complex systems makes ab initio methods a powerful tool for scientific advancement.

Experimental Results#

The ‘Experimental Results’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made. A strong section will present results clearly, with appropriate visualizations (graphs, tables, images) and statistical analyses. Quantitative metrics should be used, and error bars or confidence intervals included to show the reliability of measurements. The section should logically flow, building from simple demonstrations to more complex analyses. Comparison to existing methods or baselines is vital, demonstrating the novelty and improvement of the presented research. The authors must be transparent, acknowledging both strengths and limitations of their methods and data. A thoughtful discussion of unexpected or inconclusive findings enhances the section’s depth. Finally, a compelling narrative weaving together results and interpretation solidifies the overall impact of the ‘Experimental Results’ on the paper’s conclusions.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving efficiency is crucial; the current K-value selection process is computationally expensive, necessitating more efficient methods like adaptive or hierarchical strategies. Expanding model expressiveness by allowing varying latent dimensions (d) across classes could enhance the model’s ability to capture diverse conformational heterogeneities. Applying Hydra to cryo-ET data would significantly expand its applicability to in situ studies of complex biological processes. Investigating alternative gating mechanisms beyond the current auto-decoding approach could potentially boost accuracy and efficiency. Finally, integrating pretrained classification networks within the Hydra framework could streamline the identification of compositional states, enhancing both speed and performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

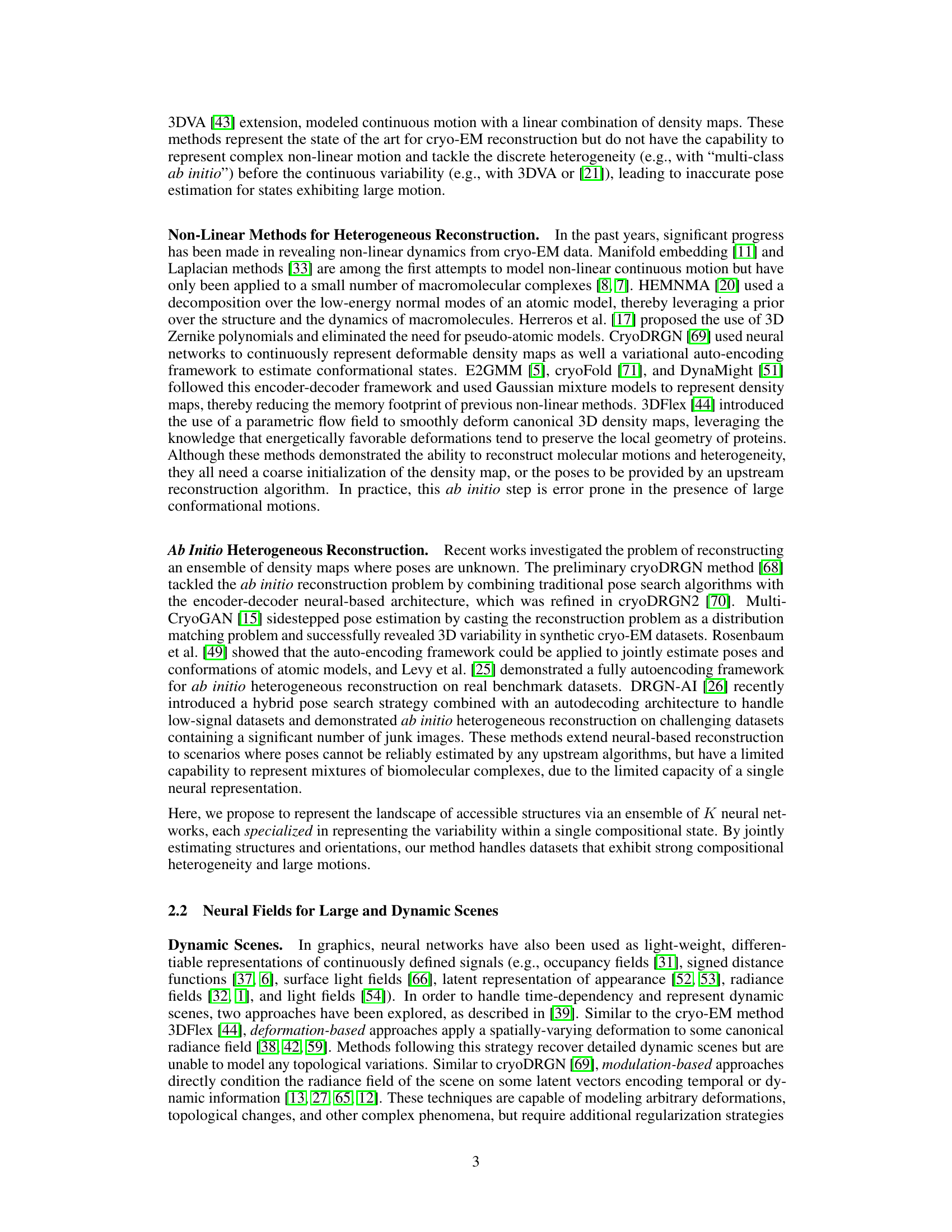

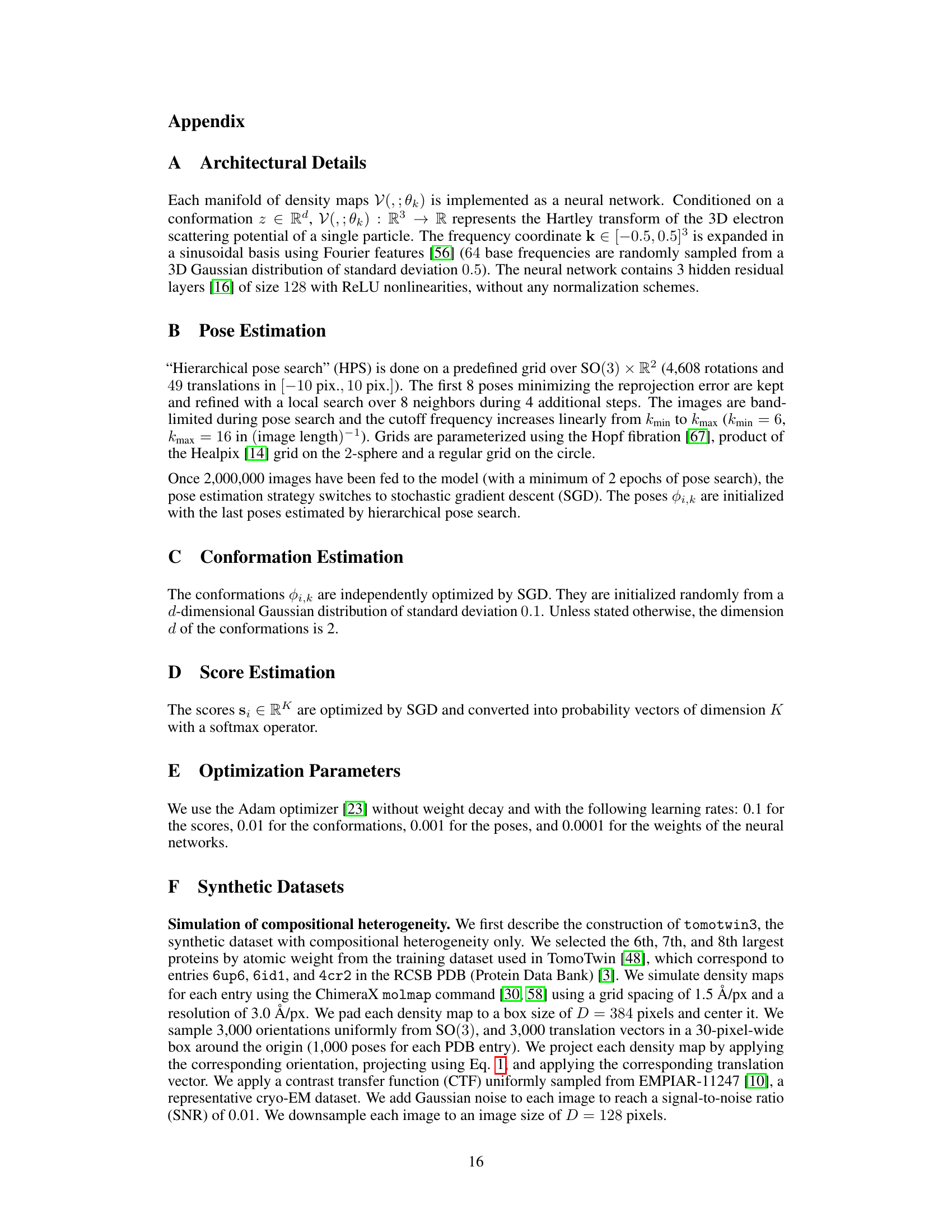

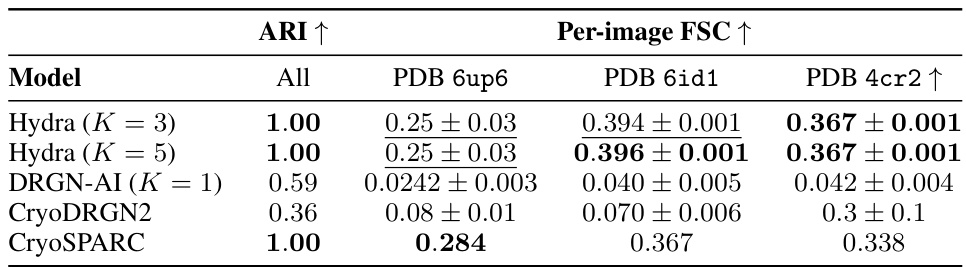

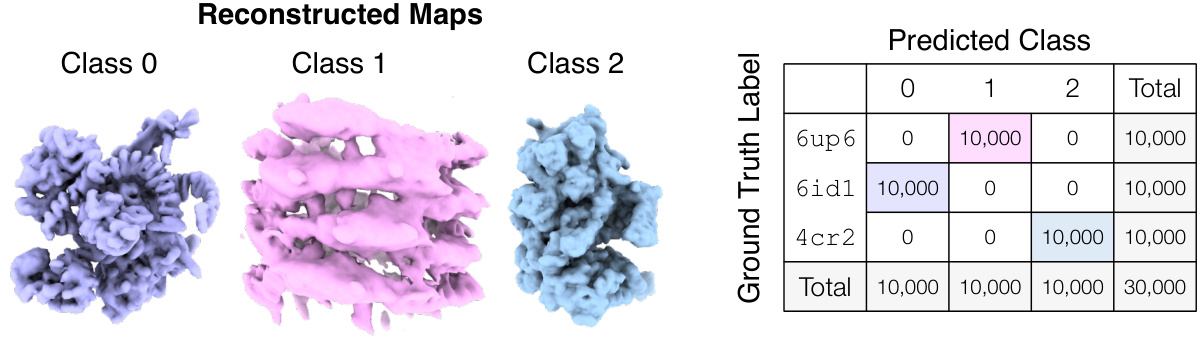

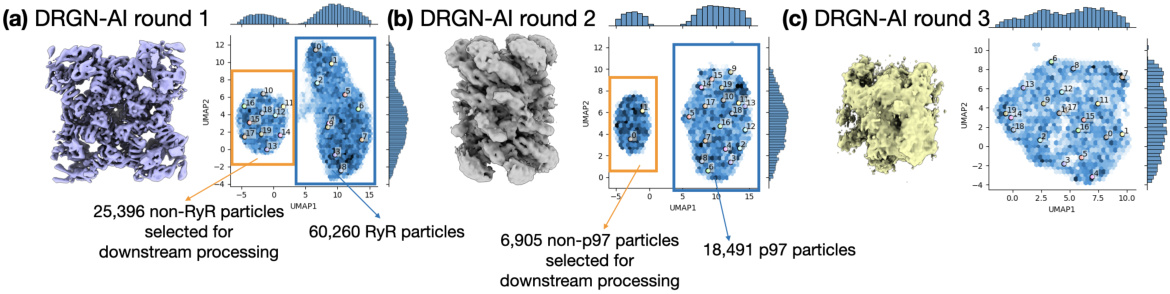

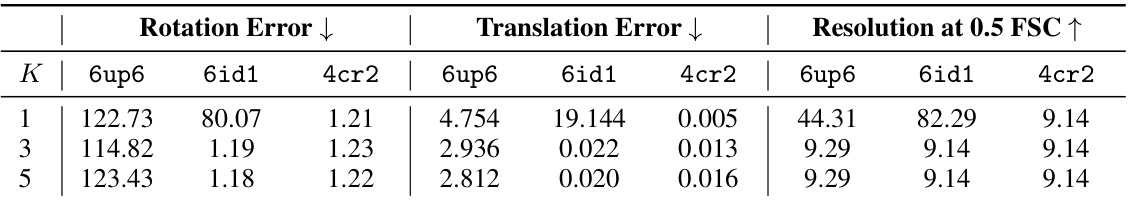

🔼 This figure demonstrates Hydra’s ability to resolve compositional heterogeneity in a synthetic dataset. It compares results using different numbers of neural fields (K=1, 3, 5) and shows that Hydra (K=3) accurately reconstructs three distinct protein structures while DRGN-AI (K=1) and an over-parameterized Hydra (K=5) fail to do so. The ground truth structures are also displayed.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hydra captures strong compositional heterogeneity in the tomotwin3 dataset. (a-c) Reconstructed densities and estimated conformations with K∈ {1,3,5}. We report the number of particles in each class between parenthesis. We represent density maps using isosurfaces. (a) With K = 1 (DRGN-AI), the model fails to reconstruct the three density maps, in spite of using d = 8 dimensions to represent conformations. (b) With K = 3 (d = 2), Hydra recovers the three density maps with perfect classification accuracy. (c) With K = 5 (d = 2), the model is over-parameterized and 2 classes out of 5 end up empty at the end of optimization. (d) Ground truth density maps for the tomotwin3 dataset.

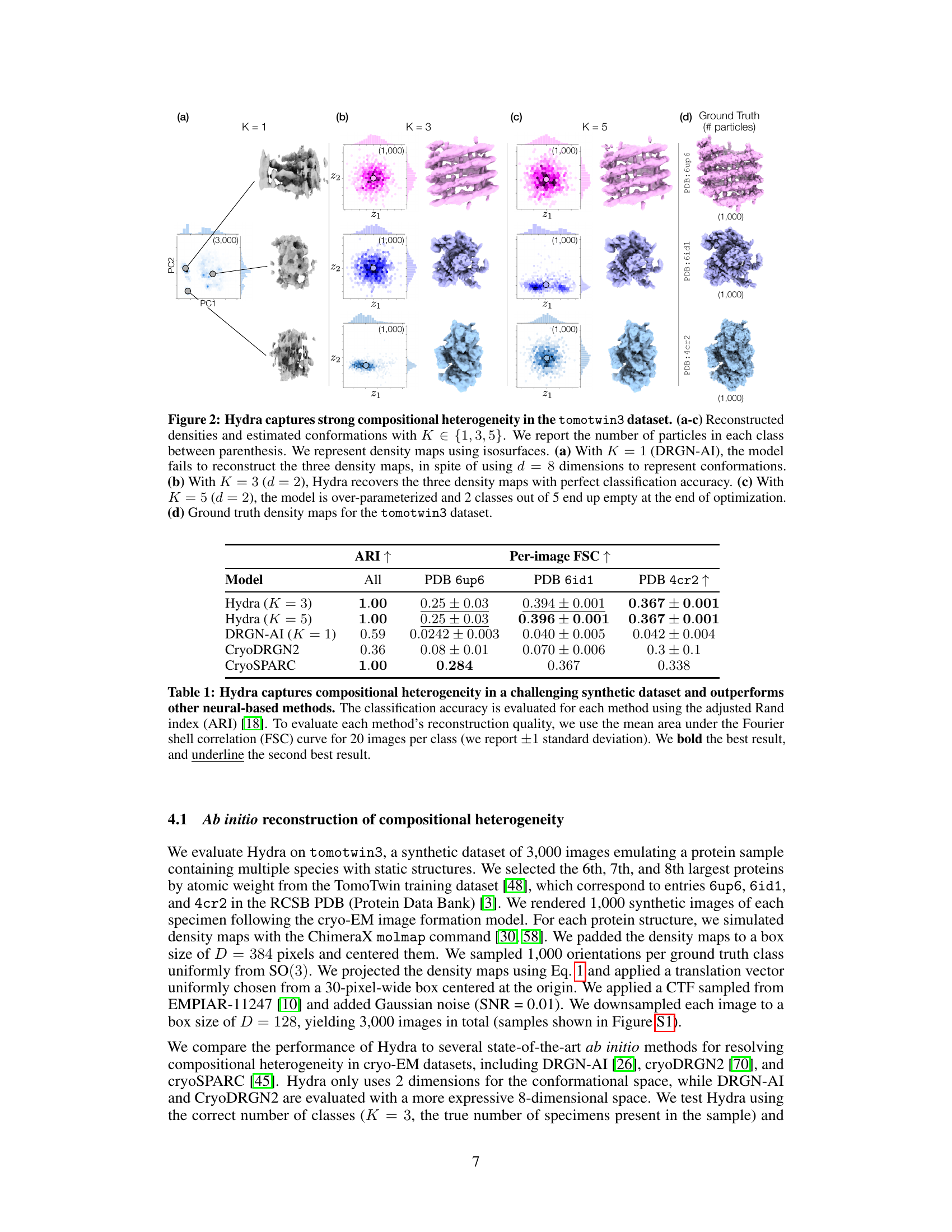

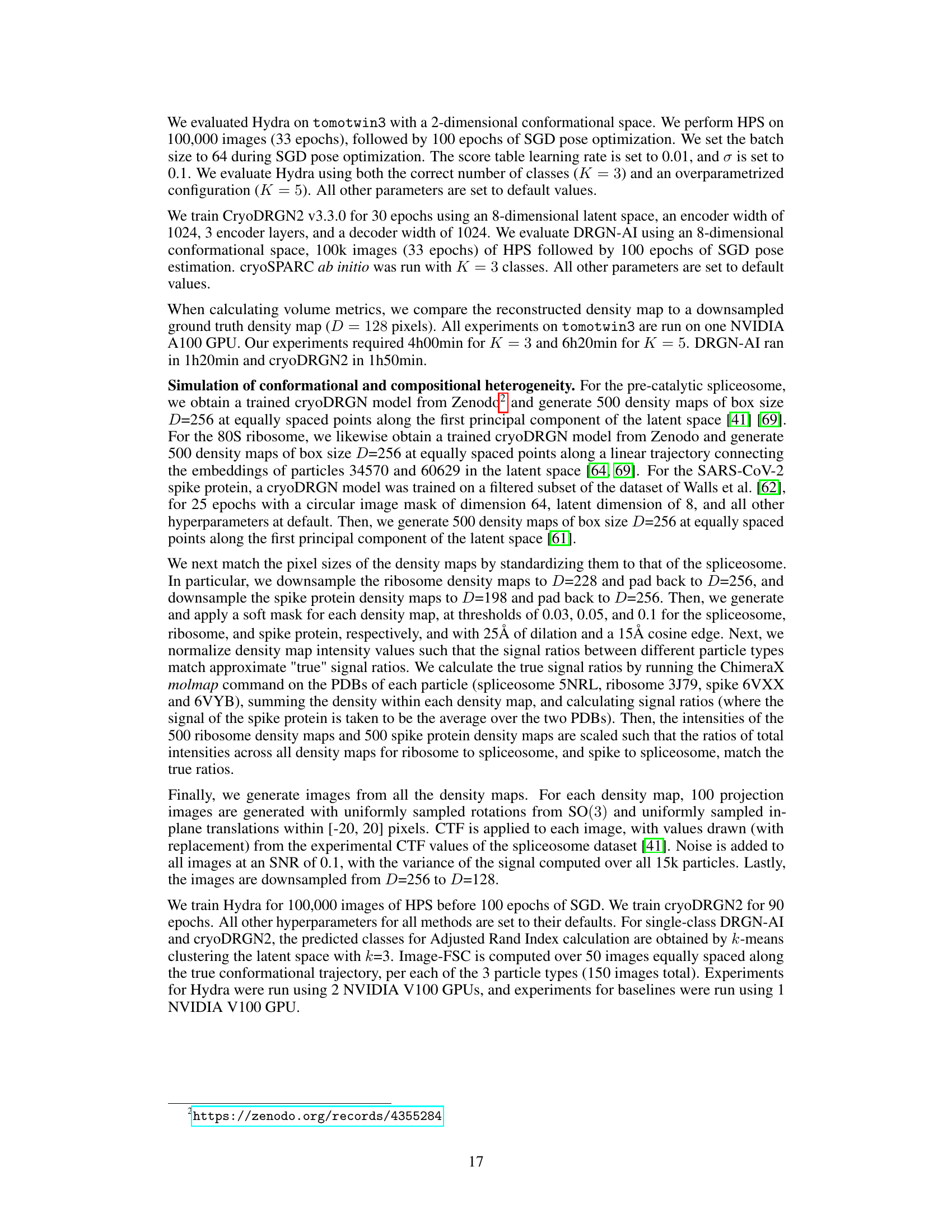

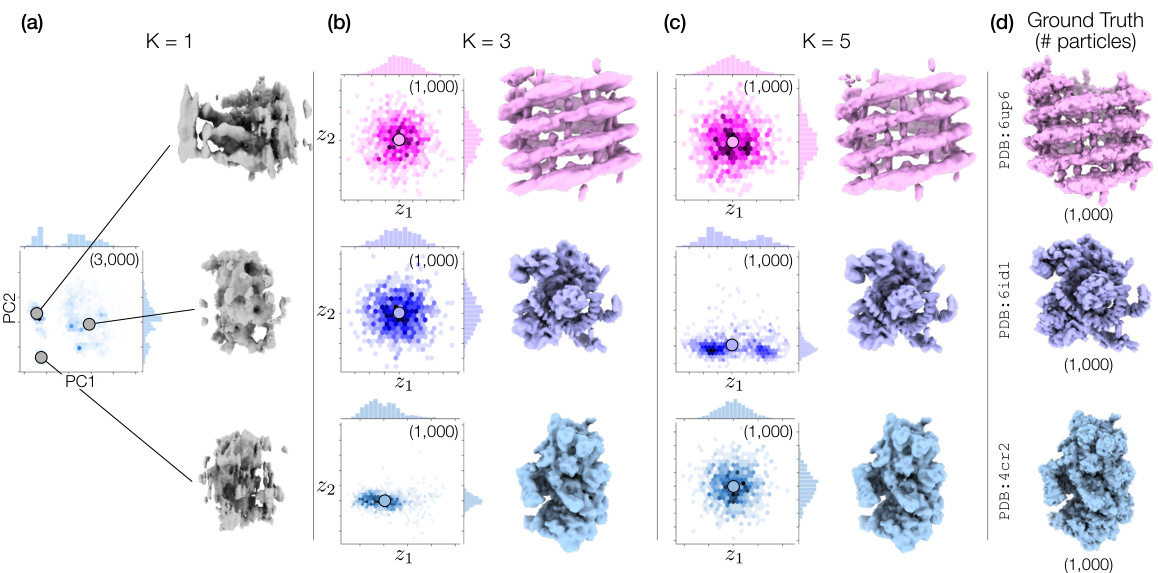

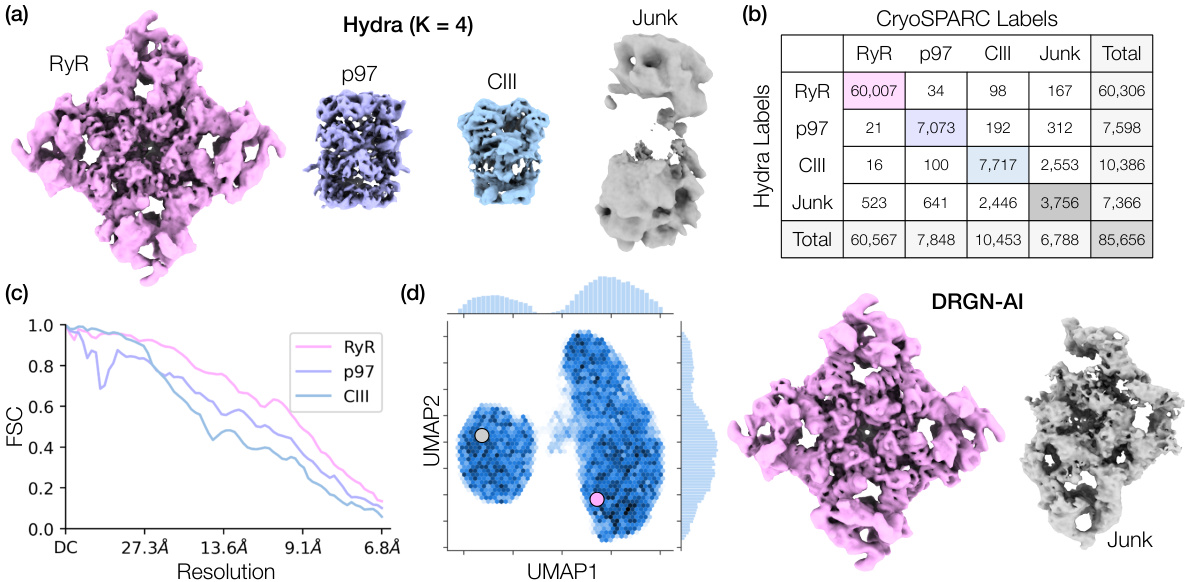

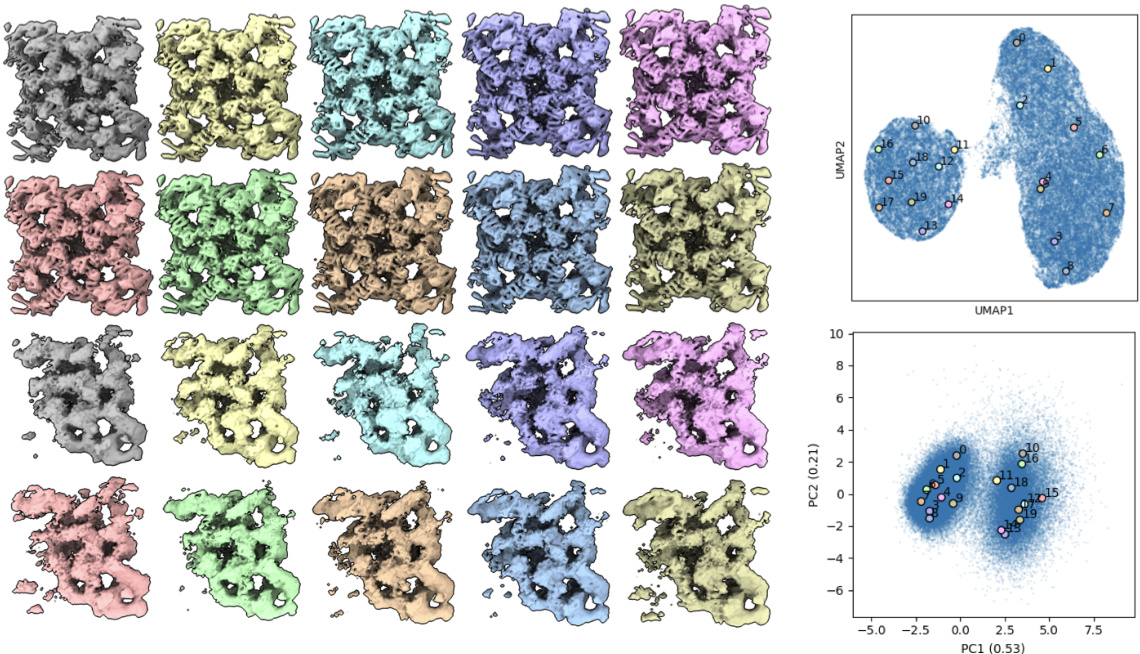

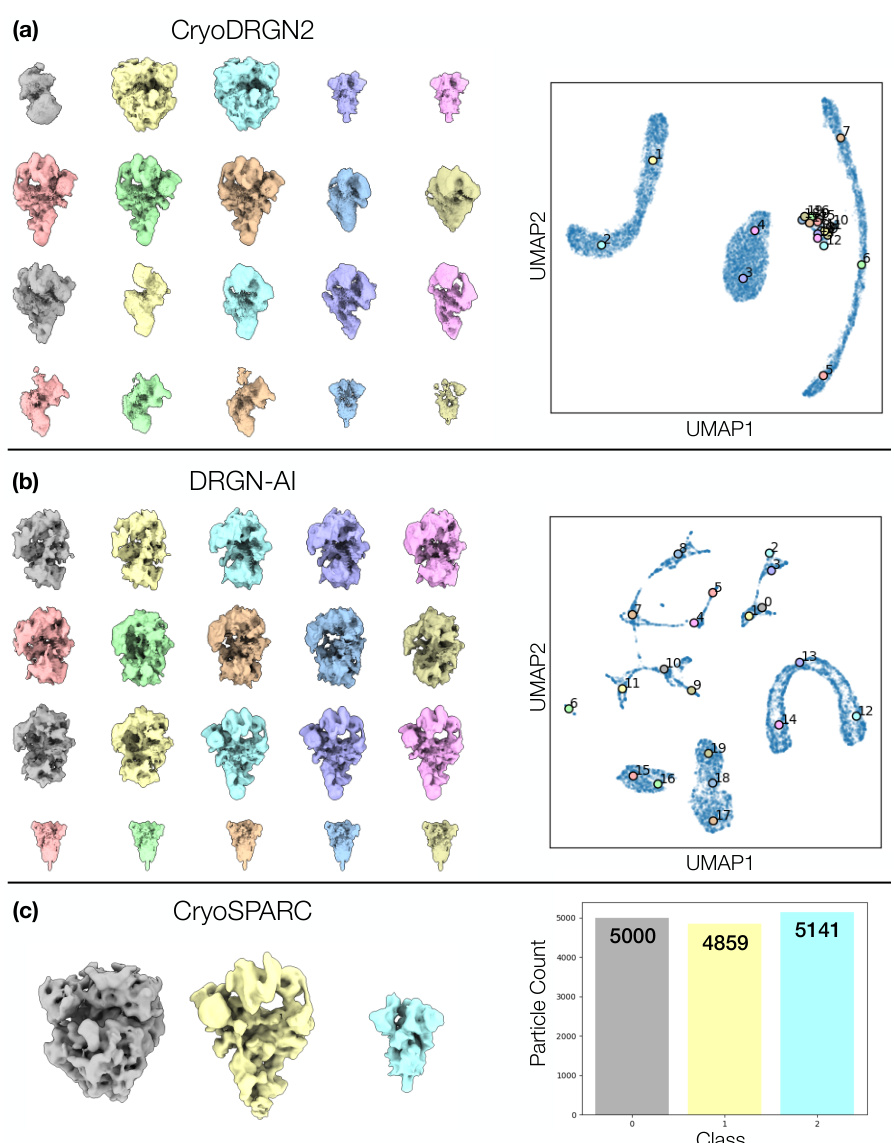

🔼 This figure demonstrates Hydra’s ability to resolve compositional heterogeneity in a real-world dataset of a protein mixture from red blood cells. Panel (a) shows the 3D density maps of different protein complexes (RyR, p97, CIII) and junk obtained by Hydra. Panel (b) provides a confusion matrix comparing Hydra’s classification to that of cryoSPARC’s heterogeneous refinement. Panel (c) displays the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curves, showing the resolution achieved by Hydra compared to cryoSPARC. Finally, Panel (d) contrasts Hydra’s results with those from DRGN-AI, highlighting Hydra’s superior performance in resolving both compositional and conformational heterogeneity.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

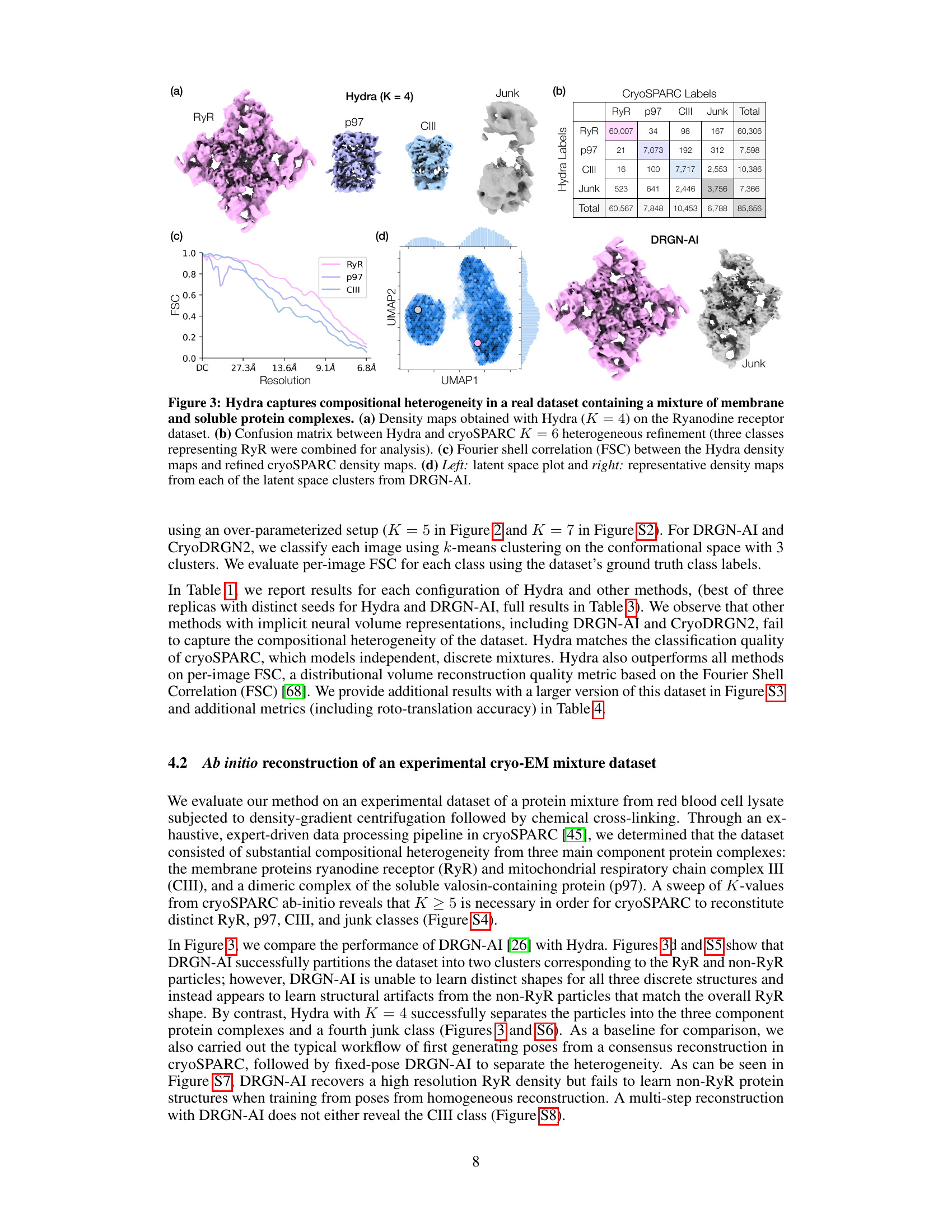

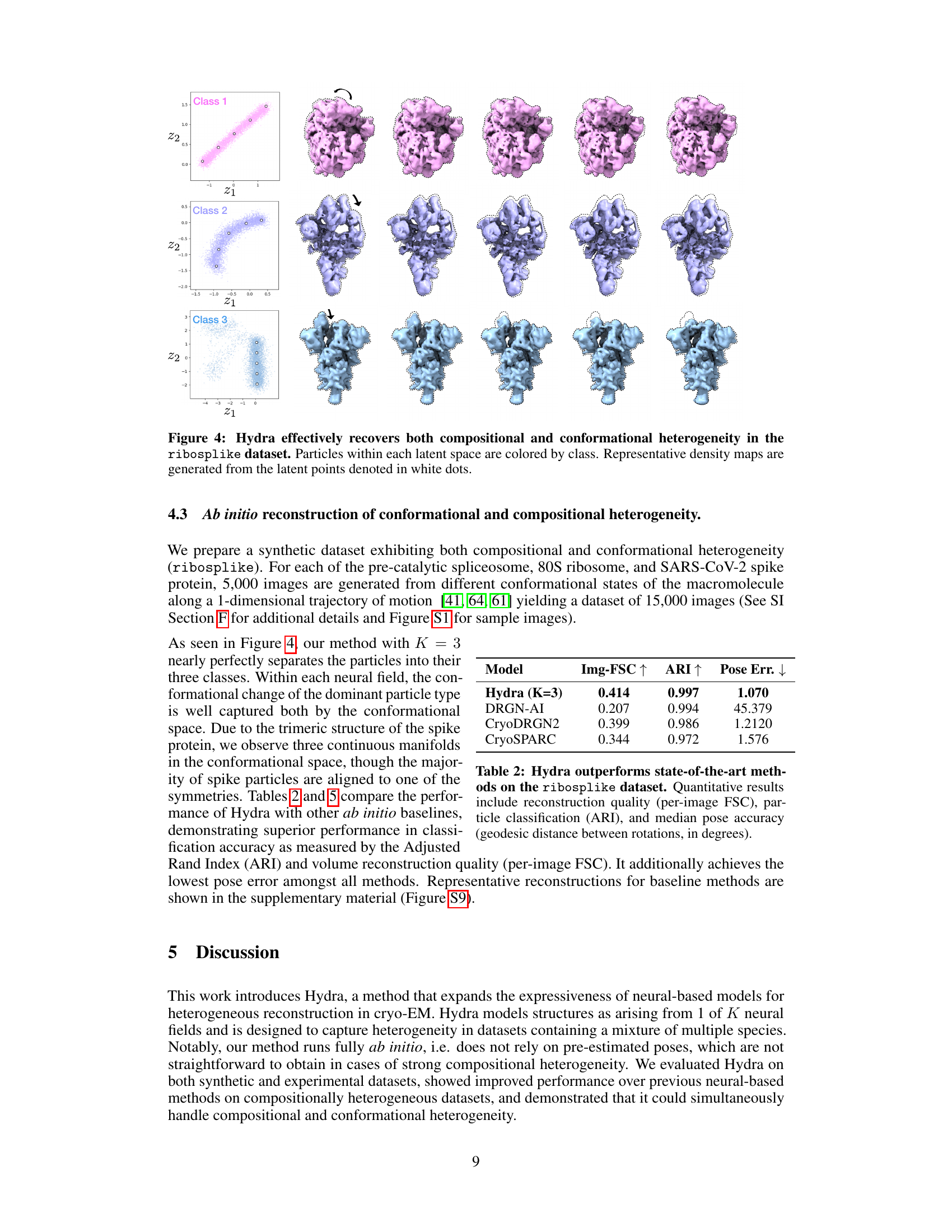

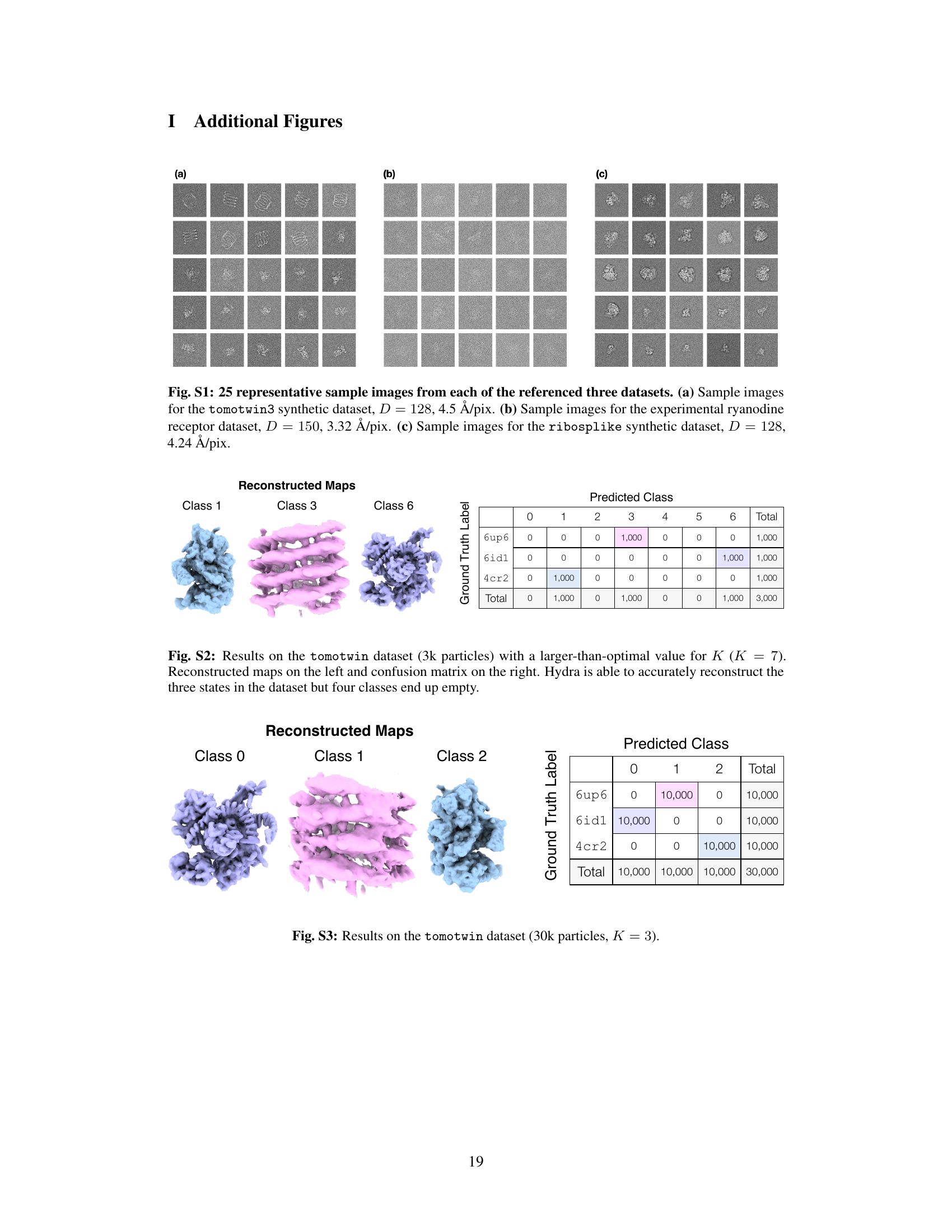

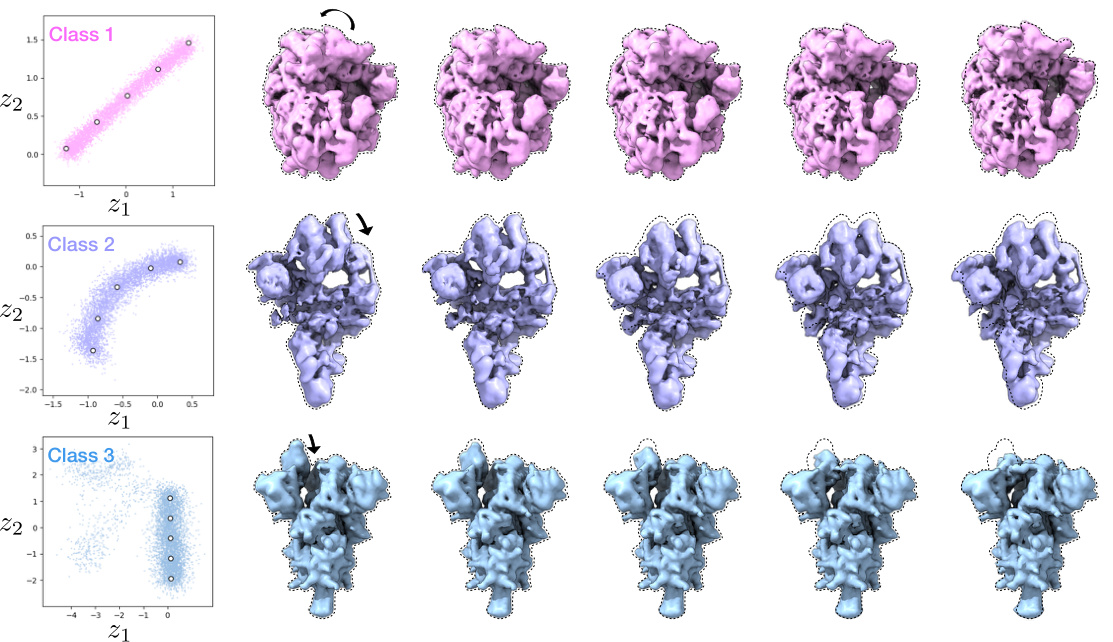

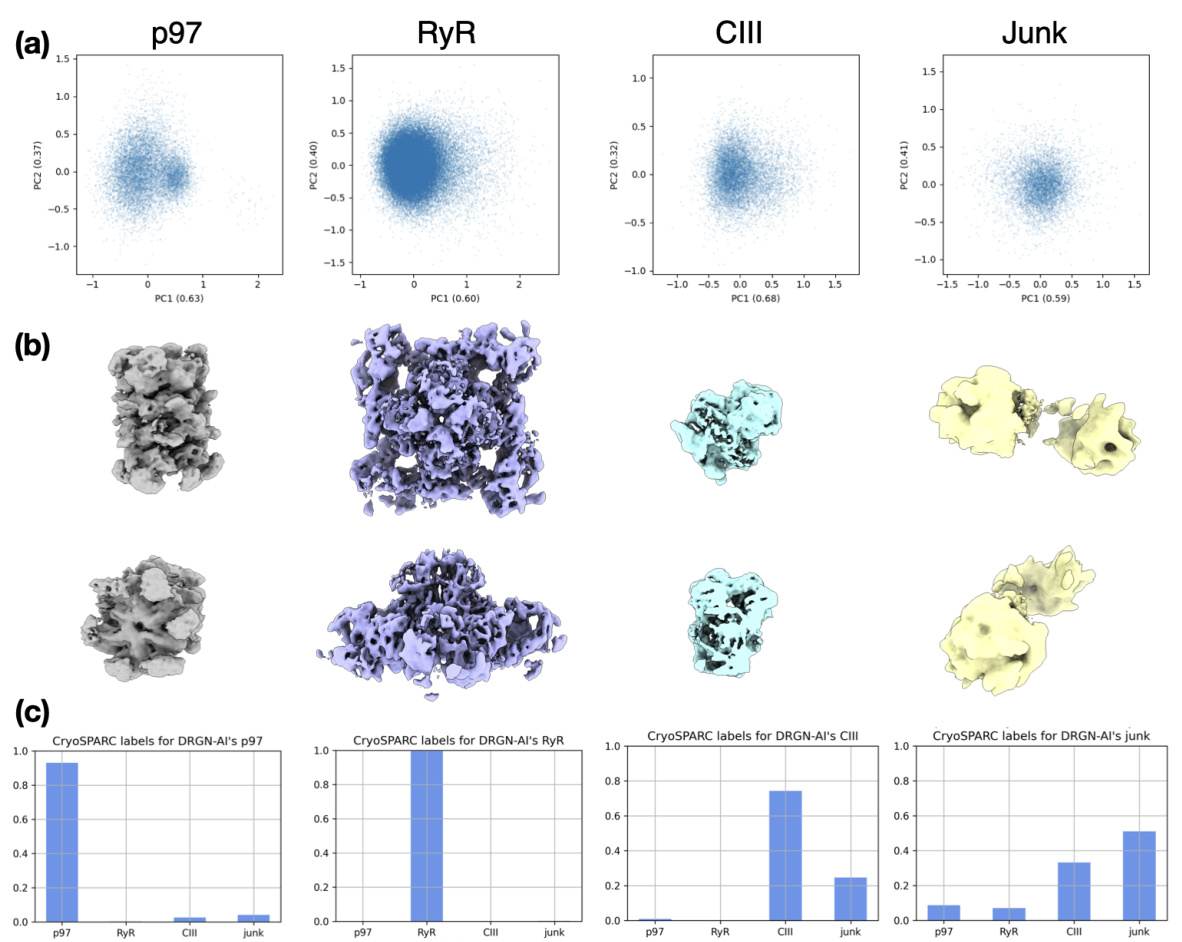

🔼 This figure demonstrates Hydra’s ability to simultaneously capture compositional and conformational heterogeneity. It shows three distinct classes of macromolecules (spliceosome, ribosome, and spike protein) each exhibiting conformational variability. The latent space (low-dimensional representation of conformations) is plotted for each class. The density maps, generated from points in latent space, illustrate the range of conformations within each class. The color-coding of particles in latent space further emphasizes the separation achieved by Hydra, showing distinct clusters for each macromolecule type.

read the caption

Figure 4: Hydra effectively recovers both compositional and conformational heterogeneity in the ribosplike dataset. Particles within each latent space are colored by class. Representative density maps are generated from the latent points denoted in white dots.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Hydra model for heterogeneous cryo-EM reconstruction. Panel (a) shows a schematic representation of the space of possible density maps as a union of low-dimensional manifolds, where each manifold represents a compositional state (k) and the conformations within each state are parameterized by intrinsic coordinates (z). Panel (b) depicts the optimization pipeline, illustrating how conformations (z), poses (φ), class probabilities (p(k)), and neural fields (θ) are jointly optimized to maximize the likelihood of the observed images.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of Hydra. (a) Schematic representation of the space of energetically plausible density maps in a heterogeneous cryo-EM dataset. We approximate this space with a finite union of low-dimensional manifolds. The compositional states (or classes) are labeled by k. The 'conformation' within class k refers to intrinsic coordinates within the k-th manifold. (b) Optimization pipeline. The conformations, poses, class probabilities and neural fields are optimized such as to maximize the likelihood of the observed images ('picked particles') under the model described in Section 3.3.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of Hydra in resolving compositional heterogeneity. It shows the results of reconstructing three different protein structures (6up6, 6id1, 4cr2) from a mixed dataset, using different numbers of neural fields (K). When using only one neural field (K=1, like the prior work DRGN-AI), Hydra fails to recover the individual protein structures. However, when using three neural fields (K=3), Hydra accurately reconstructs each individual structure. Using too many fields (K=5) leads to overfitting and inaccurate results.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hydra captures strong compositional heterogeneity in the tomotwin3 dataset. (a-c) Reconstructed densities and estimated conformations with K∈ {1,3,5}. We report the number of particles in each class between parenthesis. We represent density maps using isosurfaces. (a) With K = 1 (DRGN-AI), the model fails to reconstruct the three density maps, in spite of using d = 8 dimensions to represent conformations. (b) With K = 3 (d = 2), Hydra recovers the three density maps with perfect classification accuracy. (c) With K = 5 (d = 2), the model is over-parameterized and 2 classes out of 5 end up empty at the end of optimization. (d) Ground truth density maps for the tomotwin3 dataset.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the ability of Hydra to reconstruct compositional heterogeneity using a synthetic dataset (tomotwin3) containing three different protein structures. Panel (a) shows that with only one neural field (K=1), Hydra (which is an extension of DRGN-AI) cannot distinguish the three components. Panel (b) shows that with three neural fields (K=3), Hydra perfectly recovers the three components. Panel (c) shows that with five neural fields (K=5), the model becomes over-parameterized and fails to accurately identify the different components. Panel (d) shows the ground truth densities. This highlights Hydra’s ability to accurately classify and reconstruct components when the correct number of neural fields is used.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hydra captures strong compositional heterogeneity in the tomotwin3 dataset. (a-c) Reconstructed densities and estimated conformations with K∈ {1,3,5}. We report the number of particles in each class between parenthesis. We represent density maps using isosurfaces. (a) With K = 1 (DRGN-AI), the model fails to reconstruct the three density maps, in spite of using d = 8 dimensions to represent conformations. (b) With K = 3 (d = 2), Hydra recovers the three density maps with perfect classification accuracy. (c) With K = 5 (d = 2), the model is over-parameterized and 2 classes out of 5 end up empty at the end of optimization. (d) Ground truth density maps for the tomotwin3 dataset.

🔼 This figure demonstrates Hydra’s ability to resolve compositional heterogeneity in a real-world dataset of a mixture of protein complexes. Panel (a) shows the reconstructed density maps for each class identified by Hydra. Panel (b) presents a confusion matrix comparing Hydra’s classification with that of cryoSPARC, highlighting the accuracy of Hydra’s class assignments. Panel (c) illustrates the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between density maps obtained from Hydra and cryoSPARC, assessing the quality of the reconstructions. Finally, Panel (d) showcases a comparison with DRGN-AI, highlighting Hydra’s superior performance in resolving complex mixtures.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the Hydra method to the ribosplike dataset, a synthetic dataset designed to test the model’s ability to handle both compositional and conformational heterogeneity. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to successfully separate particles into their respective classes and capture the range of conformations within each class. Each latent space is color-coded by class, and representative density maps are generated from points in each space to illustrate the diversity of conformations.

read the caption

Figure 4: Hydra effectively recovers both compositional and conformational heterogeneity in the ribosplike dataset. Particles within each latent space are colored by class. Representative density maps are generated from the latent points denoted in white dots.

🔼 This figure demonstrates Hydra’s ability to resolve compositional heterogeneity in a real-world cryo-EM dataset. Panel (a) shows the density maps reconstructed by Hydra, revealing four distinct components (K=4). Panel (b) compares Hydra’s classification results with those from cryoSPARC, showing strong agreement. Panel (c) illustrates the high resolution achieved by Hydra using FSC, a measure of density map quality. Finally, Panel (d) contrasts Hydra’s performance with the DRGN-AI method, highlighting Hydra’s superior capacity for resolving complex mixtures.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Hydra to a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. Panel (a) displays the density maps obtained using Hydra with 4 classes. Panel (b) presents a confusion matrix comparing Hydra’s classification results with those obtained from a cryoSPARC analysis with 6 classes. Panel (c) illustrates the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) between density maps generated by Hydra and those refined using cryoSPARC. Finally, panel (d) shows a latent space plot and representative density maps from DRGN-AI, a competing method, to highlight the differences in their ability to capture compositional heterogeneity.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

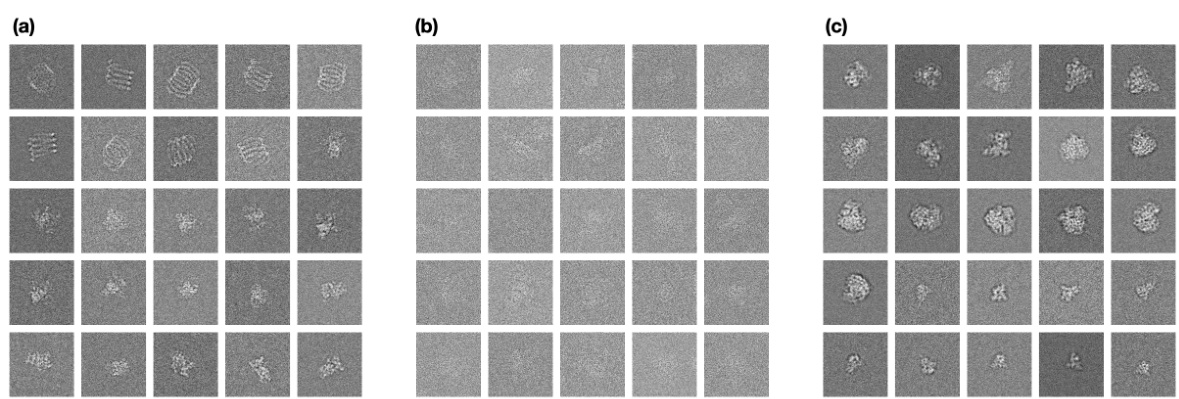

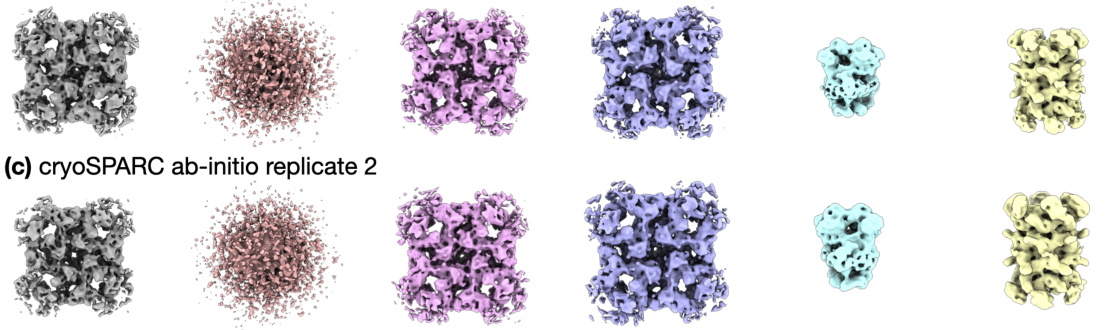

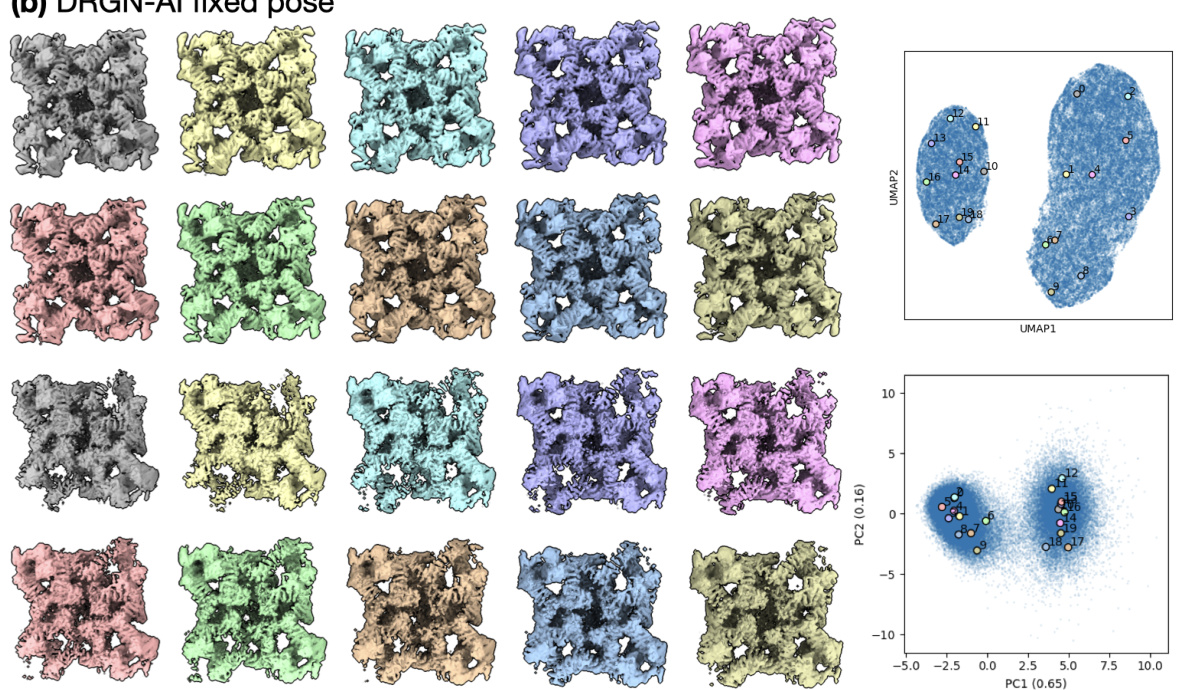

🔼 This figure compares the results of two different approaches for cryo-EM data processing: cryoSPARC homogeneous refinement followed by DRGN-AI fixed pose. The cryoSPARC homogeneous refinement failed to capture non-RyR densities due to its inability to handle compositional heterogeneity. Conversely, the DRGN-AI fixed pose approach, while achieving high-resolution RyR density, still didn’t capture non-RyR structures effectively.

read the caption

Figure S7: The typical processing workflow of generating a consensus reconstruction followed by DRGN-AI heterogeneous reconstruction fails to capture the shape of non-RyR densities, as the cryoSPARC consensus reconstruction conceals compositional heterogeneity and yields a high-resolution density for RyR only. (a) Homogeneous refinement of the entire ryanodine receptor dataset against a cryoSPARC ab initio K = 1 alignment of the entire dataset (left); right: FSC curve. (b) single-class DRGN-AI fixed pose with poses from the cryoSPARC homogeneous refinement; left: densities from k-means 20 sampling of the latent space; right: latent space plots.

🔼 Figure 3 shows the results of applying Hydra to a real dataset containing a mixture of different protein complexes (Ryanodine receptor, p97, and complex III). Panel (a) shows the density maps generated by Hydra, which successfully separates the protein complexes. Panel (b) presents a confusion matrix comparing the classification accuracy of Hydra and cryoSPARC. Panel (c) shows the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve, illustrating the quality of reconstruction of Hydra. Finally, panel (d) contrasts the results of Hydra with DRGN-AI, highlighting Hydra’s ability to successfully capture the compositional heterogeneity of the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the results of applying Hydra to an experimental dataset of a protein mixture from red blood cell lysate. Panel (a) shows the density maps generated by Hydra, with 4 compositional states (K=4). Panel (b) provides a confusion matrix comparing Hydra’s classification to that of a cryoSPARC analysis. Panel (c) displays the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) values showing a high level of agreement between Hydra and cryoSPARC. Finally, panel (d) shows a comparison to DRGN-AI, highlighting Hydra’s superior ability to discern distinct protein complexes and conformational heterogeneity.

read the caption

Figure 3: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a real dataset containing a mixture of membrane and soluble protein complexes. (a) Density maps obtained with Hydra (K = 4) on the Ryanodine receptor dataset. (b) Confusion matrix between Hydra and cryoSPARC K = 6 heterogeneous refinement (three classes representing RyR were combined for analysis). (c) Fourier shell correlation (FSC) between the Hydra density maps and refined cryoSPARC density maps. (d) Left: latent space plot and right: representative density maps from each of the latent space clusters from DRGN-AI.

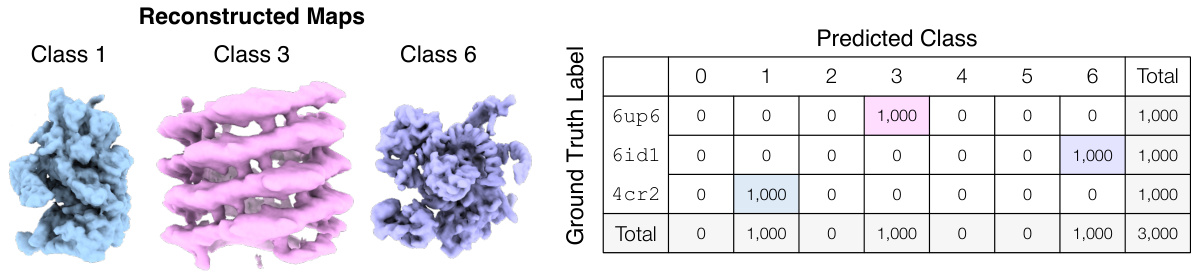

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of Hydra against other neural-based methods (DRGN-AI, CryoDRGN2, and CryoSPARC) on a synthetic dataset with compositional heterogeneity. The comparison is based on two metrics: the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which measures classification accuracy, and the mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curve, which measures the quality of 3D reconstruction. Hydra shows superior performance in both metrics, highlighting its ability to effectively resolve compositional heterogeneity.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method's reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Hydra against other neural-based methods (DRGN-AI, CryoDRGN2, and cryoSPARC) on a synthetic dataset with compositional heterogeneity. The comparison is made using two metrics: the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), measuring classification accuracy, and the mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curve, measuring reconstruction quality. The results show that Hydra achieves state-of-the-art performance on both metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method's reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of Hydra’s performance against other state-of-the-art neural-based methods for resolving compositional heterogeneity in a synthetic cryo-EM dataset. The comparison includes classification accuracy (Adjusted Rand Index or ARI), and reconstruction quality (mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation or FSC curve). Hydra demonstrates superior performance across both metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method's reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of Hydra’s performance against other neural-based methods (DRGN-AI, CryoDRGN2, and CryoSPARC) on a synthetic dataset with compositional heterogeneity. The metrics used for comparison are the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which measures classification accuracy, and the mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curve, which measures reconstruction quality. The table shows that Hydra achieves the best performance in terms of both ARI and FSC.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method’s reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of Hydra’s performance against other state-of-the-art neural-based methods on a synthetic dataset designed to evaluate compositional heterogeneity. It shows the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) for classification accuracy, the mean area under the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) curve for reconstruction quality, and the standard deviation for FSC. The best performing method for each metric is highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Hydra captures compositional heterogeneity in a challenging synthetic dataset and outperforms other neural-based methods. The classification accuracy is evaluated for each method using the adjusted Rand index (ARI) [18]. To evaluate each method’s reconstruction quality, we use the mean area under the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve for 20 images per class (we report ±1 standard deviation). We bold the best result, and underline the second best result.

Full paper#