↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current driving world models struggle with generalization to new environments, accurate prediction of critical details, and flexible action control. This paper addresses these issues by introducing Vista, a novel model trained on a large-scale, high-quality driving dataset. Vista leverages novel losses for accurate prediction and an efficient latent replacement strategy for long-horizon predictions.

Vista also achieves versatile action control by incorporating a range of controls, from high-level intentions to low-level maneuvers. The model’s capacity for generalization is demonstrated through extensive experiments, showing superior performance to existing state-of-the-art models. Further, Vista uniquely establishes a generalizable reward function for real-world action evaluation without ground truth data, a significant step forward for autonomous driving research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces Vista, a novel driving world model that surpasses existing models in generalization, prediction fidelity, and controllability. This addresses critical limitations in autonomous driving research, opening up new avenues for improving the safety and reliability of self-driving systems. The proposed generalizable reward function, established without ground truth actions, is also a significant contribution.

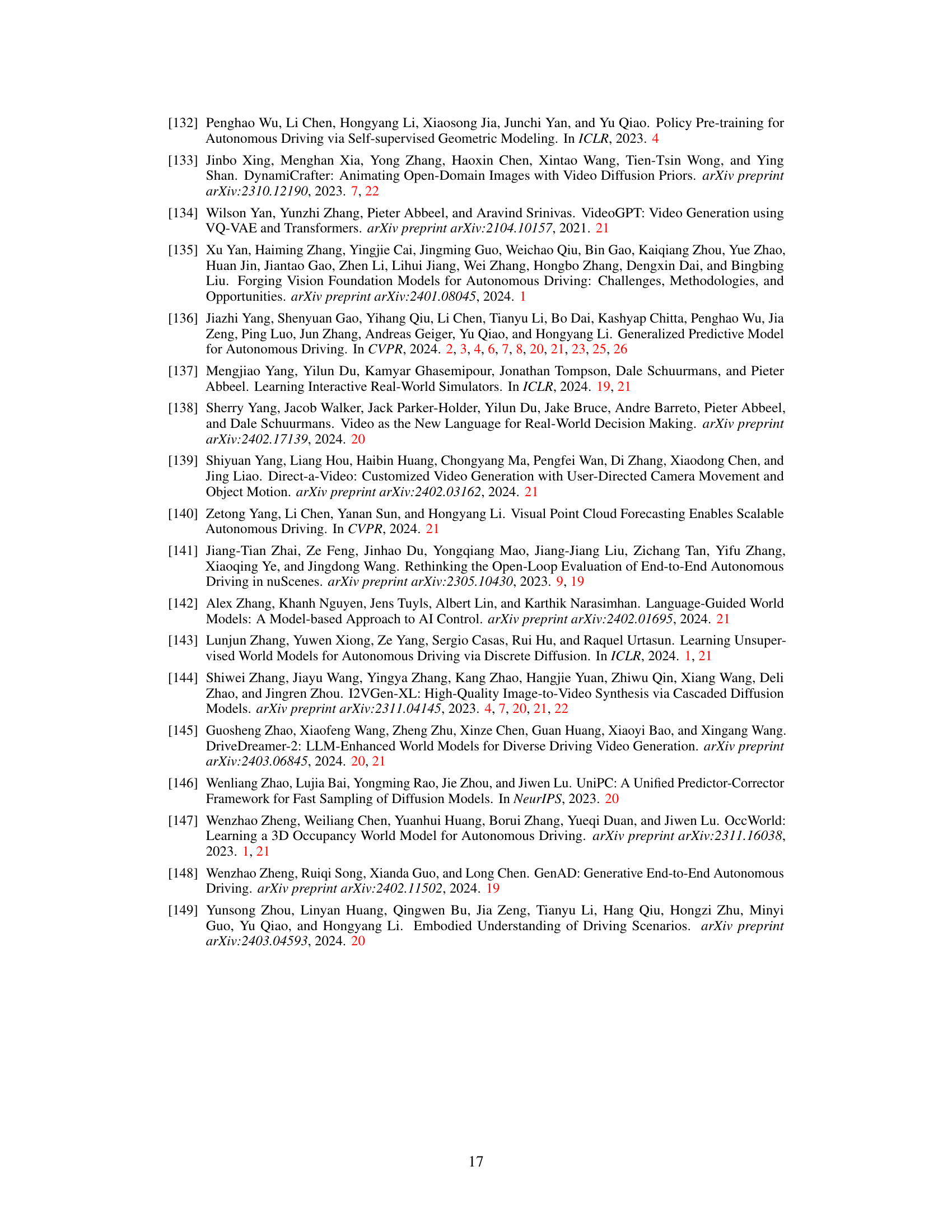

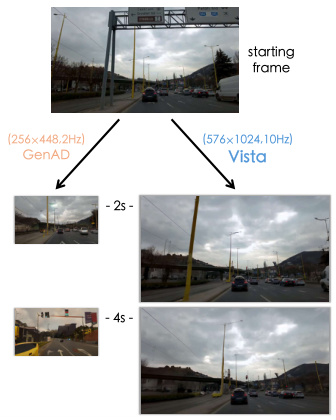

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure compares the resolution of Vista with several other real-world driving world models. It shows that Vista operates at a significantly higher resolution (576x1024 pixels) compared to the other models, which range from 80x160 to 512x576 pixels. This higher resolution allows Vista to capture more detailed and accurate information about the driving environment, improving the fidelity of its predictions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Resolution comparison. Vista predicts at a higher resolution than previous literature.

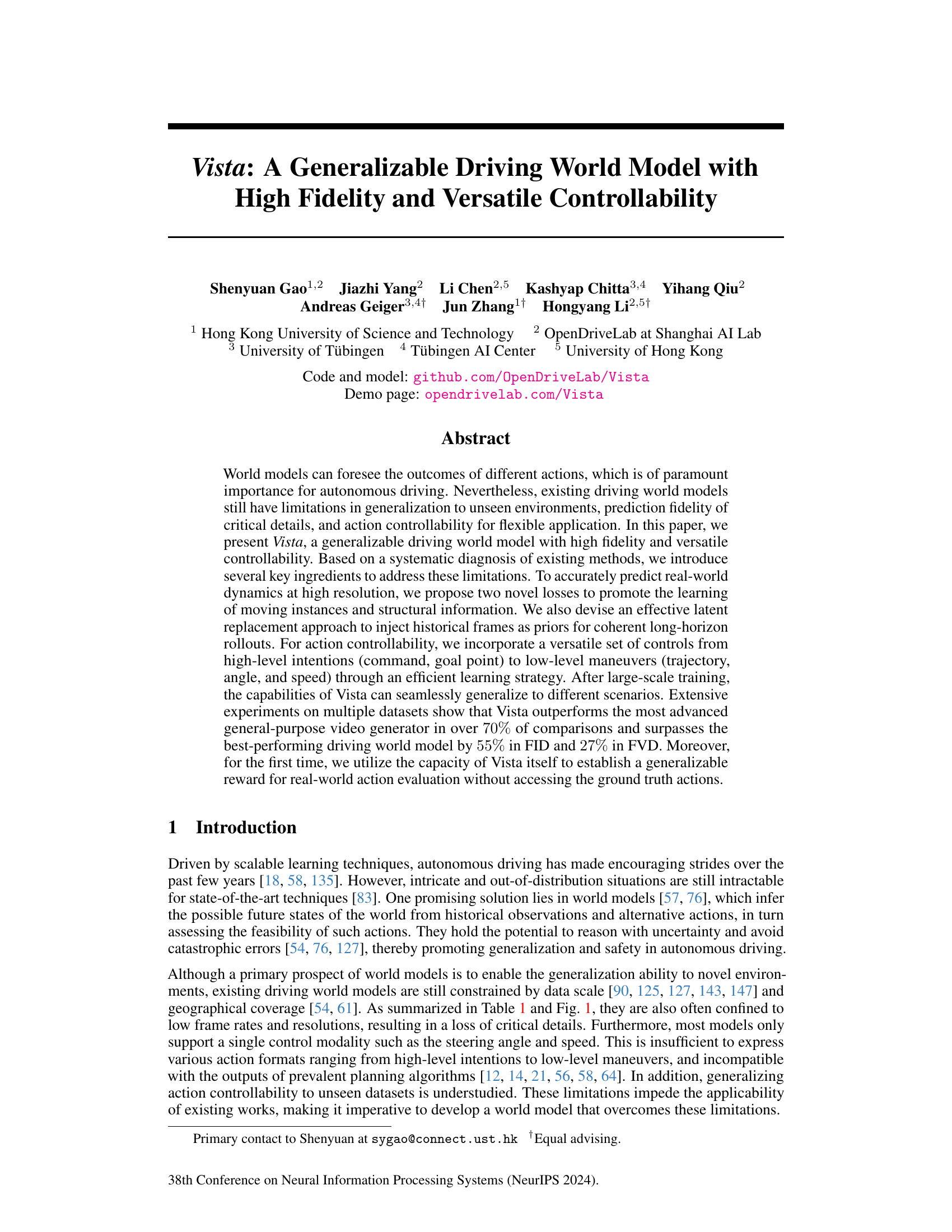

🔼 This table compares the prediction fidelity of Vista against other state-of-the-art driving world models on the nuScenes validation set. The metrics used are the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD). Lower scores indicate better fidelity. Vista significantly outperforms all other models in both FID and FVD, demonstrating its superior prediction accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of prediction fidelity on nuScenes validation set. Vista achieves encouraging results that outperform the state-of-the-art driving world models with a significant performance gain.

In-depth insights#

Vista’s Architecture#

Vista’s architecture likely centers around a two-phase training pipeline. The first phase focuses on building a high-fidelity predictive model, possibly leveraging a pre-trained Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) model as a foundation. This phase likely incorporates novel loss functions to enhance the learning of dynamic aspects and structural details within driving scenes. A key innovation may involve an effective latent replacement strategy to inject historical frames as priors for more coherent long-horizon prediction. The second phase integrates multi-modal action controllability, enabling control through a unified interface ranging from high-level commands to low-level trajectory parameters. This likely involves an efficient learning strategy to handle diverse action formats. The architecture also likely incorporates a generalizable reward function for real-world action evaluation, potentially using Vista’s own prediction uncertainty as a basis. The overall design emphasizes generalization, high-fidelity prediction, and versatile controllability which are crucial aspects for a successful driving world model.

Novel Loss Functions#

The concept of “Novel Loss Functions” in a research paper warrants a thoughtful exploration. These functions are designed to address specific shortcomings of existing methods and are crucial for model improvements. The success hinges on how well these functions capture the intricacies of the problem domain. A well-designed novel loss function would guide the model’s learning process towards desirable properties, such as enhanced precision or robustness. The paper should detail the intuition, design choices, and mathematical formulation of these functions. Furthermore, it should thoroughly justify their novelty by explicitly comparing them against previous loss functions and demonstrate a quantifiable improvement in performance. The success of novel loss functions is not solely dependent on their design but critically relies on the chosen evaluation metrics which must accurately reflect the intended model behaviour. Empirical results and ablation studies are essential to support the claims of improvement in the model. Finally, a discussion of the limitations and potential drawbacks of the proposed functions adds to the paper’s completeness.

Action Control#

The aspect of ‘Action Control’ in autonomous driving research is critical, focusing on the ability of a system to execute actions effectively and safely based on different inputs. High-fidelity prediction is crucial for safe action planning. A model needs to accurately predict the outcomes of possible actions in complex and unpredictable real-world driving scenarios. Generalization is key: a system shouldn’t be limited to specific environments or situations but instead needs to function across diverse and unseen conditions. This requires robust training data and model architectures. Versatility in action control is another important element. The system’s actions shouldn’t be limited to low-level controls such as steering angle and speed. High-level intentions or commands, which are more abstract and flexible, should also be incorporated to enable more complex and nuanced driving behaviors. Multi-modal action control is essential to achieve versatile behavior that can integrate with advanced planning algorithms.

Generalizable Reward#

A generalizable reward function is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of actions within a reinforcement learning framework, especially in complex and dynamic environments like autonomous driving. A key challenge lies in creating a reward that isn’t dependent on ground truth data, which is often unavailable or expensive to obtain. This paper proposes a novel approach where the model’s own prediction uncertainty serves as the reward signal. Higher uncertainty implies riskier, less reliable actions, therefore receiving a lower reward. This is particularly innovative as it leverages the model’s internal representation of the world, rather than relying on external sensors or detectors. This method is inherently generalizable; it doesn’t require labeled data beyond what the model is already trained on, a key advantage over previous techniques which used external reward functions. The approach’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments on unseen data. This generalizable reward function is a substantial advancement because it enables direct evaluation of actions in real-world settings without the need for ground-truth annotations. This reduces the reliance on potentially noisy or incomplete external data, thus advancing the robustness of autonomous driving systems and similar applications.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section would ideally delve into several key areas. Addressing computational limitations is crucial, given the high spatiotemporal resolution and model complexity; exploring efficient architectures or training methods could significantly improve scalability. Expanding the dataset to encompass more diverse and challenging driving scenarios, including those with diverse weather conditions or less common driving situations, is essential for boosting generalization. Another critical area for future research is the integration of Vista’s high fidelity prediction with planning and control algorithms. Exploring how Vista’s output can be used within complex decision-making pipelines for autonomous vehicles represents a significant opportunity. Furthermore, investigating robustness to noisy or incomplete sensor data, a common issue in real-world settings, is important. Finally, exploring different applications of Vista beyond driving simulation and reward modeling, like using the model for evaluating and improving driving policies or training more robust reinforcement learning agents, should also be considered.

More visual insights#

More on figures

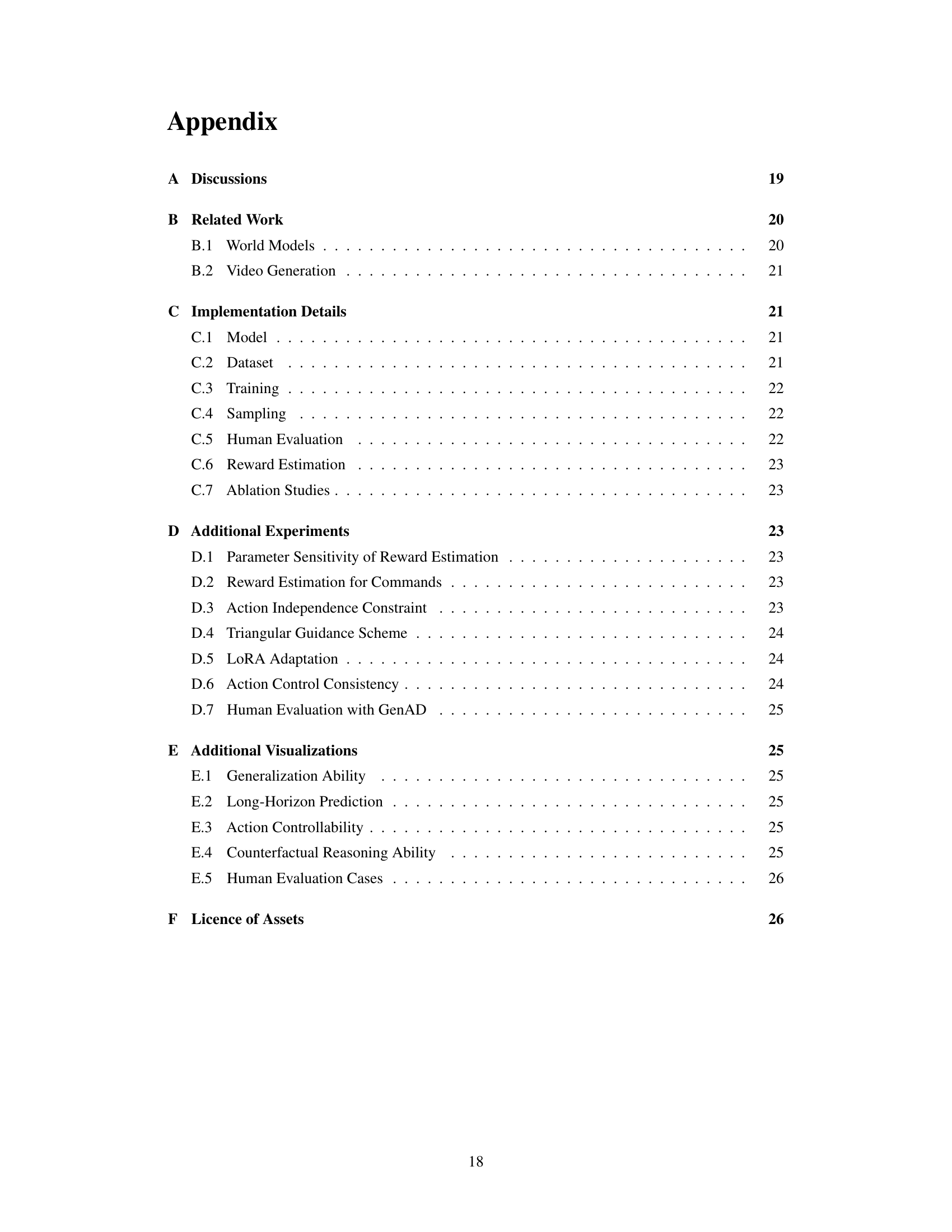

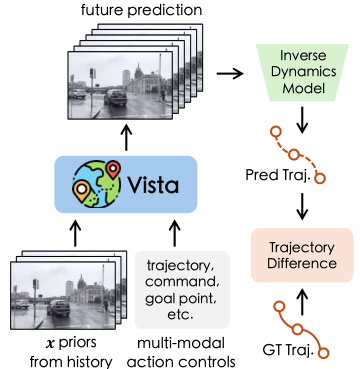

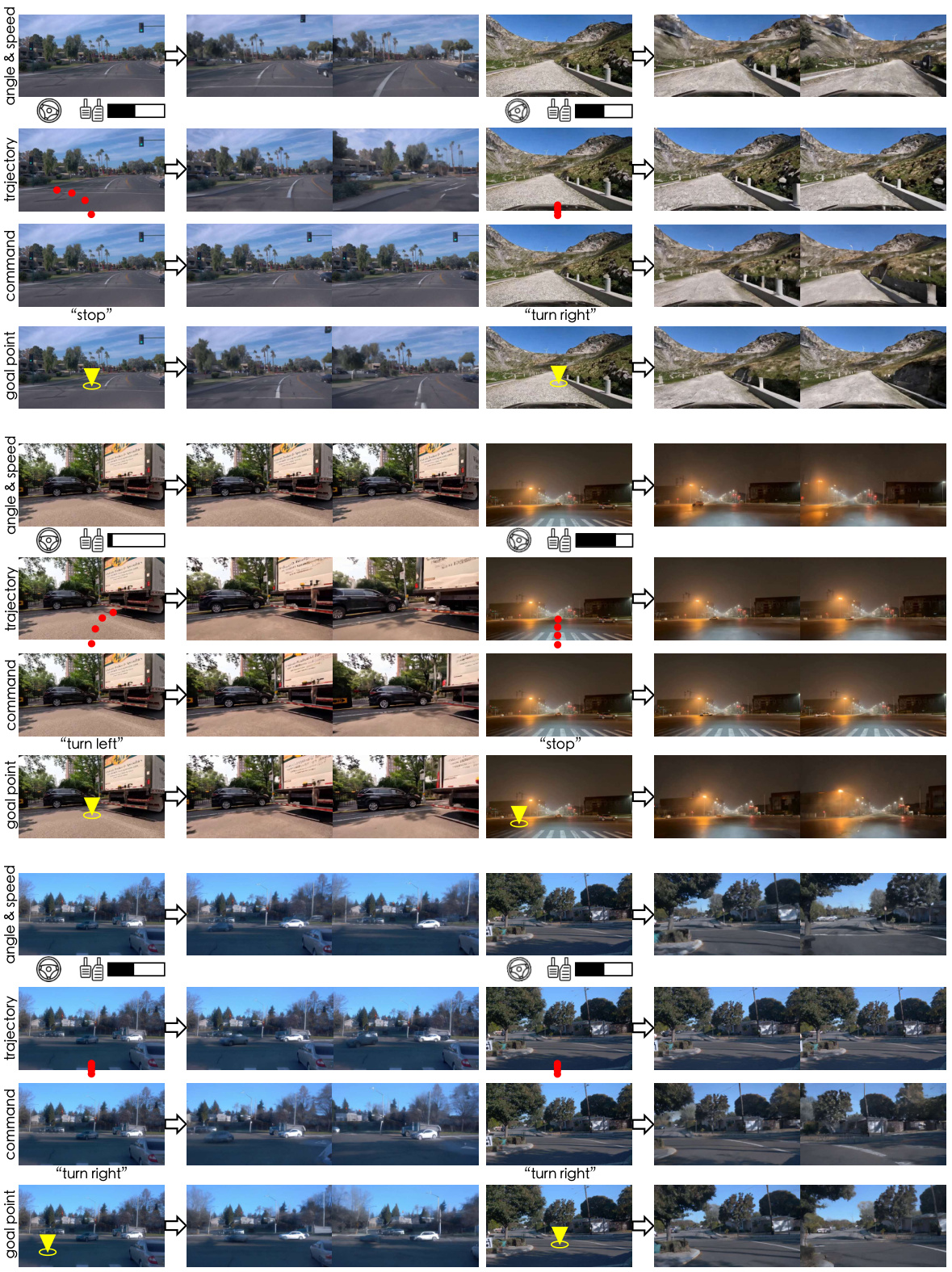

🔼 This figure showcases the main capabilities of the Vista model. Subfigure (A) demonstrates high-fidelity future prediction from arbitrary starting points with high temporal and spatial resolution. Subfigure (B) shows the model’s ability to perform coherent long-horizon rollouts. Subfigure (C) highlights the model’s versatile action controllability through the usage of multi-modal action formats. Finally, subfigure (D) illustrates the model’s unique ability to serve as a generalizable reward function for evaluating real-world driving actions without the need for ground truth action data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Capabilities of Vista. Starting from arbitrary environments, Vista can anticipate realistic and continuous futures at high spatiotemporal resolution (A-B). It can be controlled by multi-modal actions (C), and serve as a generalizable reward function to evaluate real-world driving actions (D).

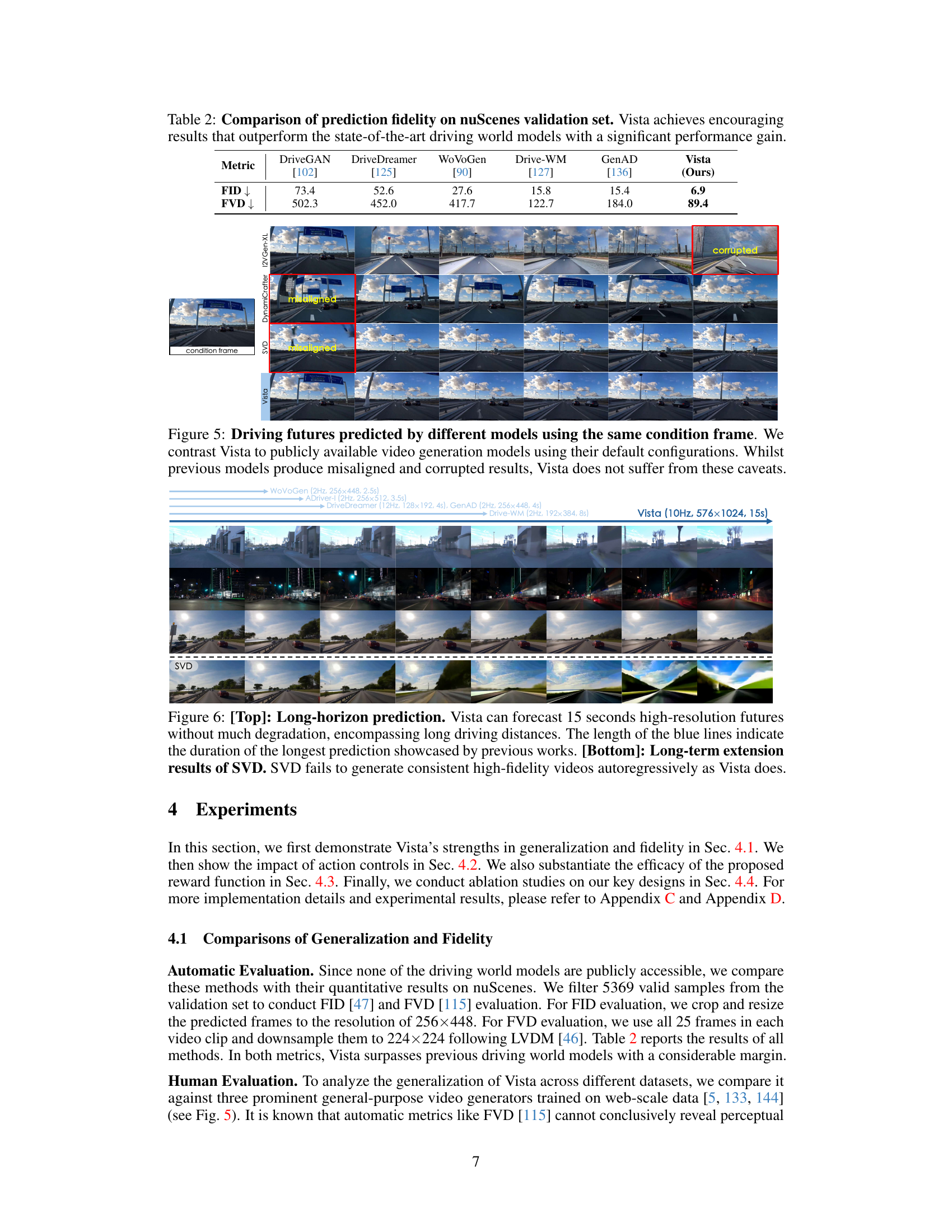

🔼 This figure illustrates the Vista pipeline and training procedure. The left side shows how Vista uses dynamic priors (position, velocity, acceleration) from the past three frames via latent replacement, resulting in high-fidelity predictions, and allows for multi-modal action control and long-horizon predictions through autoregressive rollouts. The right side demonstrates the two-phase training process, where the first phase trains the base model and the second phase utilizes the pretrained weights to learn action controllability using LoRA adapters.

read the caption

Figure 3: [Left]: Vista pipeline. In addition to the initial frame, Vista can absorb more priors about future dynamics via latent replacement. Its prediction can be controlled by different actions and be extended to long horizons through autoregressive rollouts. [Right]: Training procedure. Vista takes two training phases, where the second phase freezing the pretrained weights to learn action controls.

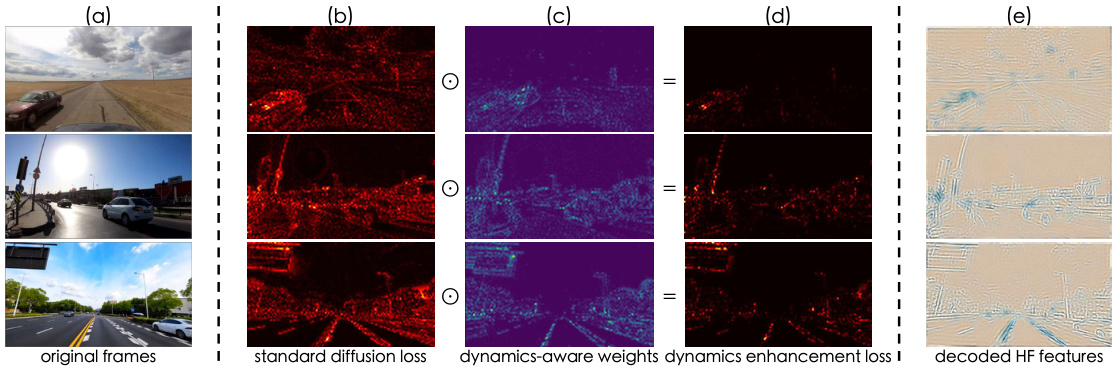

🔼 This figure illustrates the design of the loss functions used in Vista. It compares the standard diffusion loss with the proposed dynamics enhancement loss and structure preservation loss. The dynamics enhancement loss focuses more on critical regions with significant motion, while the structure preservation loss emphasizes high-frequency features to preserve structural details. The visualization shows how the different losses affect the learning process and improve prediction quality.

read the caption

Figure 4: Illustration on loss design. Different from the standard diffusion loss (b) that is distributed uniformly, our dynamics enhancement loss (d) enables an adaptive concentration on critical regions (c) (e.g., moving vehicles and roadsides) for dynamics modeling. Moreover, by explicitly supervising high-frequency features (e), the learning of structural details (e.g., edges and lanes) can be enhanced.

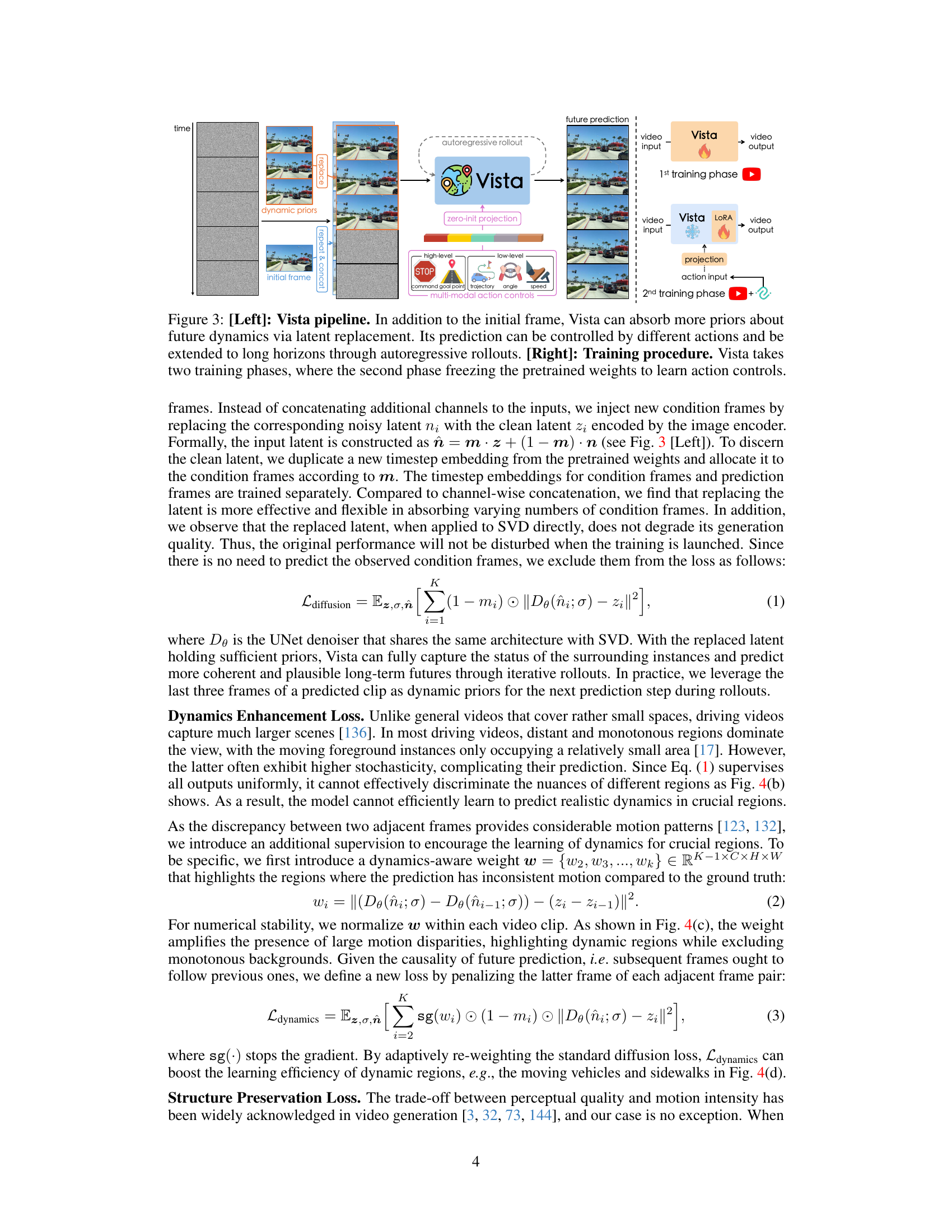

🔼 This figure compares the driving scene prediction results of Vista against three other video generation models (SVD, DynamiCrafter, and I2VGen-XL). All models receive the same starting frame as input. The results show that Vista generates more realistic and coherent future predictions compared to other models, which have problems such as misalignment and corrupted details.

read the caption

Figure 5: Driving futures predicted by different models using the same condition frame. We contrast Vista to publicly available video generation models using their default configurations. Whilst previous models produce misaligned and corrupted results, Vista does not suffer from these caveats.

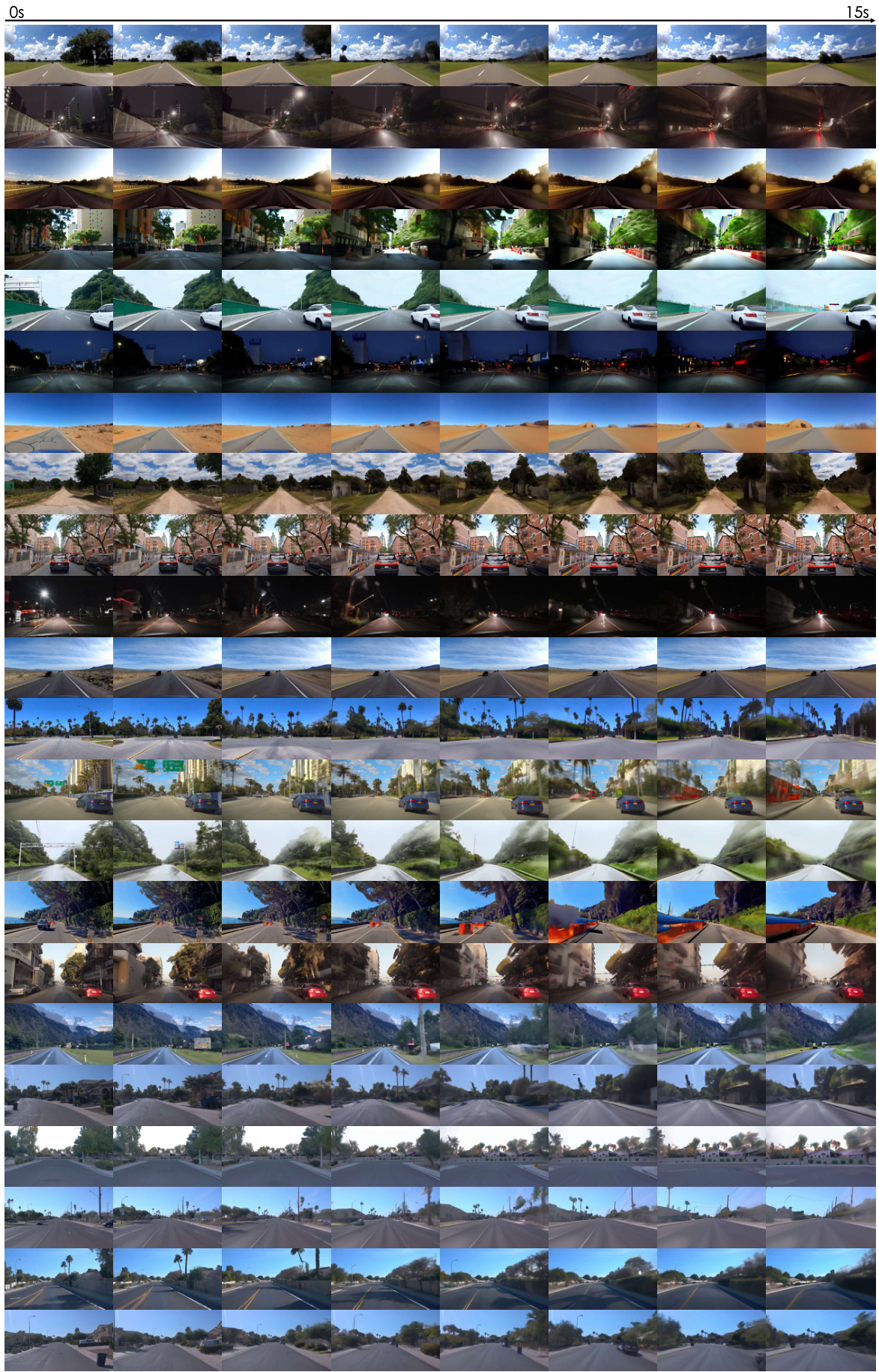

🔼 This figure compares the long-horizon prediction capabilities of Vista with several other state-of-the-art models. The top part shows Vista’s ability to predict 15 seconds into the future with high fidelity and consistency. The bottom illustrates the failure of SVD (Stable Video Diffusion) to generate consistent high-fidelity predictions over long time horizons, highlighting Vista’s advantage in long-term prediction.

read the caption

Figure 6: [Top]: Long-horizon prediction. Vista can forecast 15 seconds high-resolution futures without much degradation, encompassing long driving distances. The length of the blue lines indicates the duration of the longest prediction showcased by previous works. [Bottom]: Long-term extension results of SVD. SVD fails to generate consistent high-fidelity videos autoregressively as Vista does.

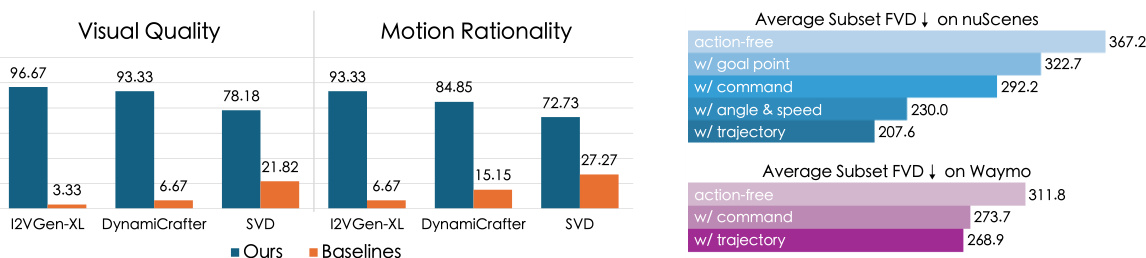

🔼 This figure presents the results of a human evaluation comparing Vista’s performance against several baseline models on two aspects: visual quality and motion rationality. Participants were presented pairs of videos and asked to choose which one was better in terms of each metric. The results show that Vista was preferred significantly more often than other models, indicating its superior performance in generating both visually appealing and realistically moving videos.

read the caption

Figure 7: Human evaluation results. The value denotes the percentage of the times that one model is preferred over the other. Vista outperforms existing works in both metrics.

🔼 This figure showcases the capabilities of the Vista model. It demonstrates high-fidelity future prediction from arbitrary starting points (A and B), showing consistent long-horizon predictions. It also highlights Vista’s versatility in action control, handling multiple modes (C) such as commands, goal points, and low-level maneuvers. Finally, (D) illustrates Vista’s novel use as a generalizable reward function for evaluating real-world driving actions without ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 2: Capabilities of Vista. Starting from arbitrary environments, Vista can anticipate realistic and continuous futures at high spatiotemporal resolution (A-B). It can be controlled by multi-modal actions (C), and serve as a generalizable reward function to evaluate real-world driving actions (D).

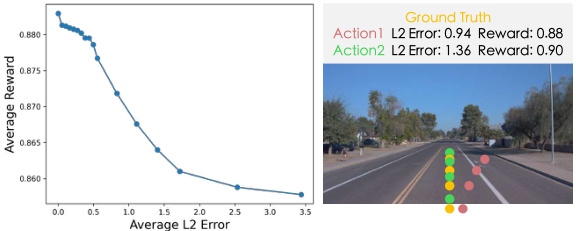

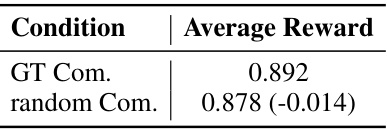

🔼 This figure shows two plots. The left plot is a line graph showing the relationship between average reward and average L2 error. The average reward decreases as the average L2 error increases. The right plot is an image showing a road scene with three different action trajectories (ground truth, Action1, and Action2) overlaid. Each trajectory has an associated L2 error and reward value. The reward values indicate that the proposed reward function can better distinguish between actions than the L2 error alone.

read the caption

Figure 10: [Left]: Average reward on Waymo with different L2 errors. [Right]: Case study. The relative contrast of our reward can properly assess the actions that the L2 error fails to judge.

🔼 This figure shows the effect of using different numbers of dynamic priors (consecutive frames) on the quality of future predictions. The results show that using more dynamic priors leads to more realistic and consistent movement of objects in the scene, particularly those that are in motion. This highlights the importance of incorporating historical context into the prediction process to improve accuracy and coherence.

read the caption

Figure 11: Effect of dynamic priors. Injecting more dynamic priors yields more consistent future motions with the ground truth, such as the motions of the white vehicle and the billboard on the left.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effects of two losses used in the Vista model: the dynamics enhancement loss and the structure preservation loss. The left side shows that the dynamics enhancement loss improves the realism of motion in generated videos by encouraging more realistic movement of objects. The right side shows that the structure preservation loss enhances structural details in the generated videos, resulting in sharper edges and more defined shapes.

read the caption

Figure 12: [Left]: Effect of dynamics enhancement loss. The model supervised by the dynamics enhancement loss generates more realistic dynamics. In the first example, instead of remaining static, the front car moves forward normally. In the second example, when the ego-vehicle steers right, the trees shift towards the left naturally adhering to the real-world geometric rules. [Right]: Effect of structure preservation loss. The proposed loss yields a clearer outline of the objects as they move.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Vista pipeline and its two-phase training process. The left side shows how Vista uses latent replacement to incorporate dynamic priors from historical frames to predict realistic and continuous futures and how these predictions can be controlled by various actions. The right side details Vista’s training procedure that consists of two phases: (1) a prediction-focused phase that utilizes dynamic priors for higher fidelity and (2) an action control learning phase that freezes pretrained weights and learns action controls using LoRA adapters for efficient learning.

read the caption

Figure 3: [Left]: Vista pipeline. In addition to the initial frame, Vista can absorb more priors about future dynamics via latent replacement. Its prediction can be controlled by different actions and be extended to long horizons through autoregressive rollouts. [Right]: Training procedure. Vista takes two training phases, where the second phase freezing the pretrained weights to learn action controls.

🔼 This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the impact of hyperparameters on the proposed reward function. The x-axis represents the average L2 error between the estimated trajectory and the ground truth, and the y-axis represents the average reward. Three lines are plotted, each corresponding to a different combination of the number of denoising steps and ensemble size used in the reward estimation. The results show that increasing the number of denoising steps leads to a larger difference in rewards between trajectories with different L2 errors. This indicates that increasing the number of denoising steps improves the discriminative ability of the reward function. On the other hand, increasing the ensemble size has a smaller impact on the discriminative ability and mainly contributes to stabilizing the reward estimations. The dotted lines represent the average reward for the ground truth trajectories and the worst trajectories.

read the caption

Figure 14: Sensitivity of reward estimation to hyperparameters. Increasing the number of denoising steps can produce more discriminative rewards, whereas increasing the ensemble size can slightly stabilize the estimations.

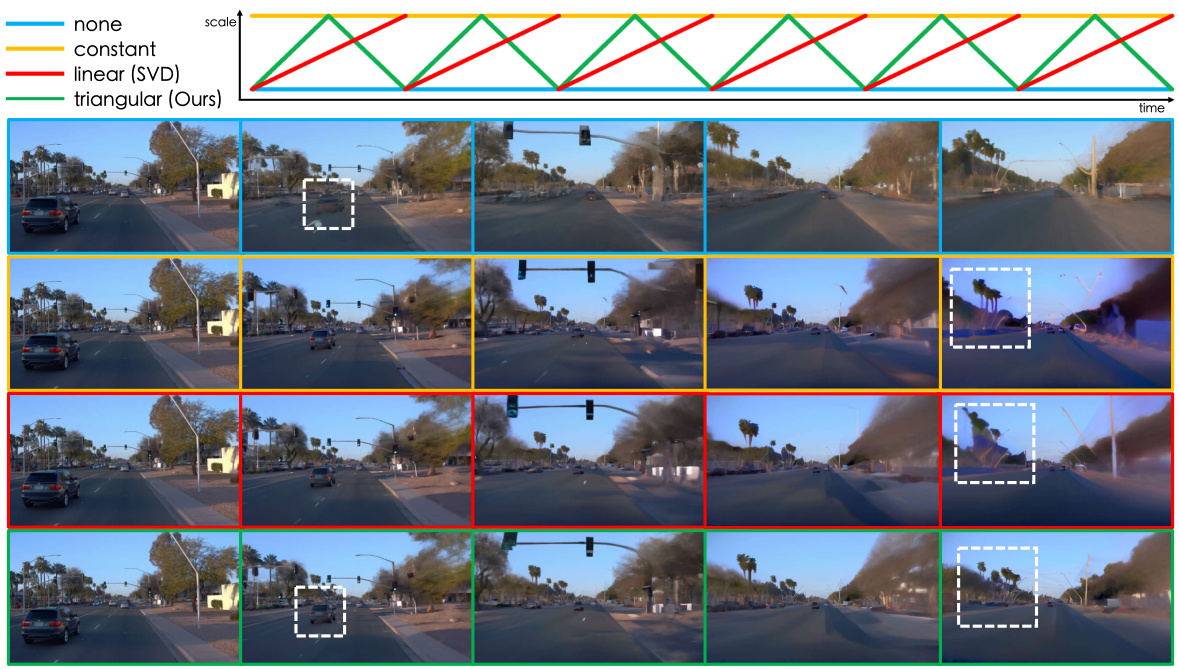

🔼 This figure compares the effect of different classifier-free guidance (CFG) schemes on the quality of long-term video prediction (15 seconds). Four different CFG schemes are tested: none, constant, linear (as used in Stable Video Diffusion), and triangular (the authors’ proposed method). The results show that the triangular scheme provides the best balance between generating detailed videos and avoiding oversaturation, a common issue in long-term video prediction.

read the caption

Figure 15: Effect of guidance scale. We predict 15s long-term videos with different CFG schemes. Our method achieves the optimal equilibrium between detail generation and saturation maintenance.

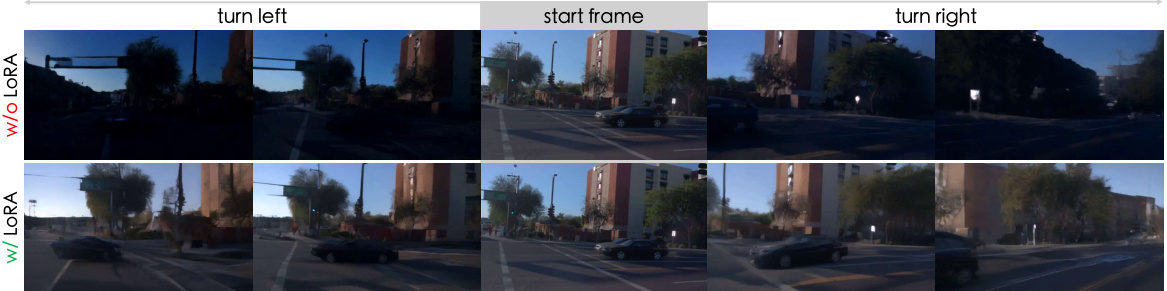

🔼 This figure demonstrates the importance of using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) when fine-tuning the Vista model for action controllability. Two versions of the model were trained, one with LoRA and one without. Both models were trained on the nuScenes dataset, but their predictions were tested on the unseen Waymo dataset. The results show that the model trained without LoRA suffers from visual artifacts, indicating that LoRA is crucial for preserving visual quality during the fine-tuning process.

read the caption

Figure 16: Necessity of LoRA adaptation. Training newly added projections alone without LoRA results in visual corruptions. The compared variants are trained on nuScenes and inferred on Waymo.

🔼 This figure compares the prediction results of Vista with other video generation models given the same starting frame. It demonstrates Vista’s ability to produce high-fidelity, aligned predictions compared to other models that suffer from misalignment and corruption, especially in long horizon prediction.

read the caption

Figure 5: Driving futures predicted by different models using the same condition frame. We contrast Vista to publicly available video generation models using their default configurations. Whilst previous models produce misaligned and corrupted results, Vista does not suffer from these caveats.

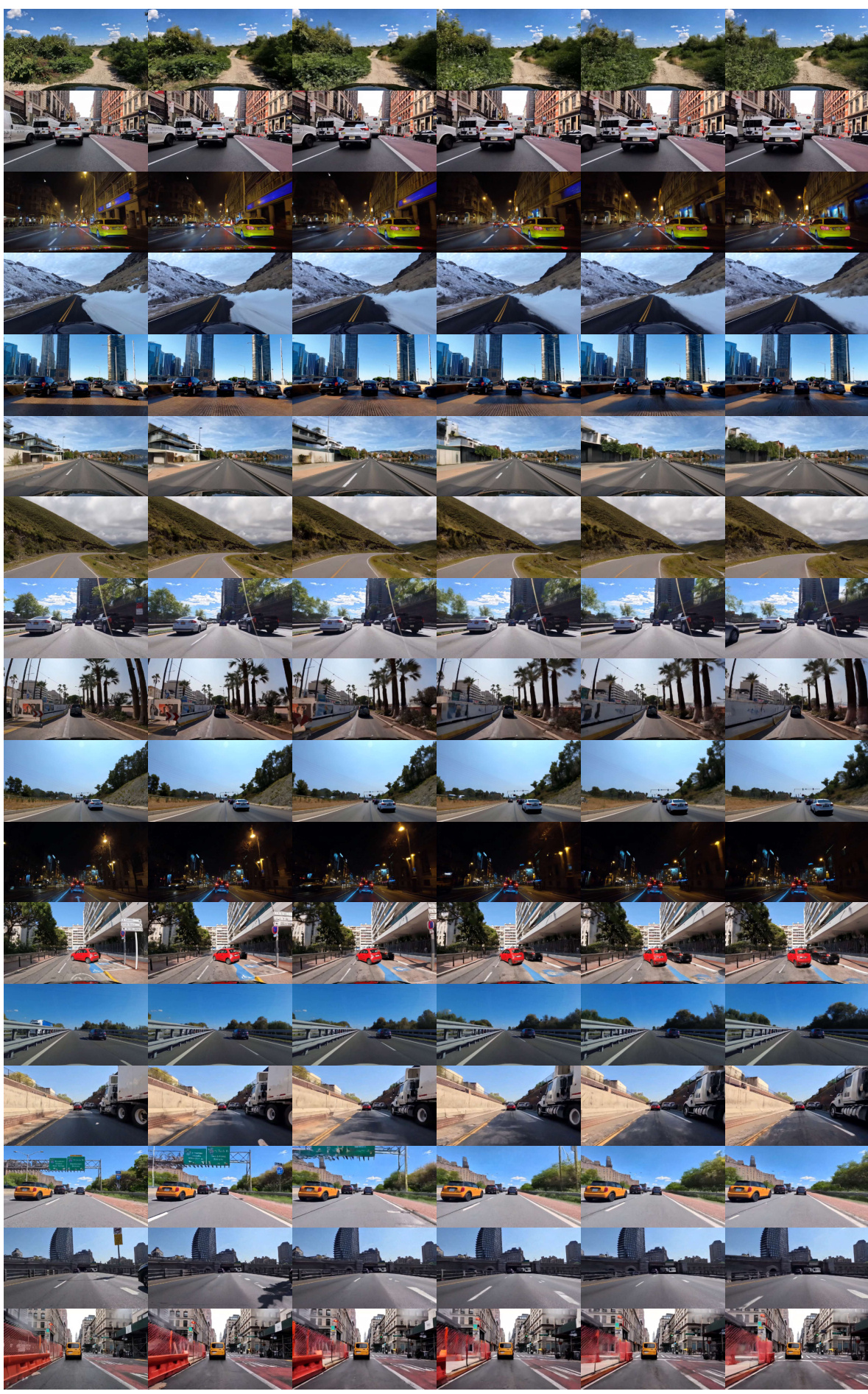

🔼 This figure shows the generalization ability of Vista across diverse driving scenes. It demonstrates Vista’s capacity to predict high-resolution future video frames, accurately depicting the behavior of vehicles and pedestrians, even in scenarios with camera poses unseen during training. The scenes shown are diverse, including countrysides, tunnels, and various perspectives. This highlights Vista’s impressive understanding of real-world driving dynamics.

read the caption

Figure 18: Generalization ability of Vista. We apply Vista across diverse scenes (e.g., countrysides and tunnels) with unseen camera poses (e.g., the perspective of a double-decker bus). Our model can predict high-resolution futures with vivid behaviors of vehicles and pedestrians, exhibiting strong generalization abilities and profound comprehension of world knowledge. Best viewed zoomed in.

🔼 This figure showcases four key capabilities of Vista. (A) and (B) demonstrate Vista’s ability to generate high-fidelity predictions of future driving scenarios, with (B) highlighting its capability to produce consistent predictions over long horizons. (C) shows that Vista supports diverse control modalities, enabling flexible control. (D) shows that Vista’s predictive capabilities can be used to evaluate real-world driving actions without explicit ground-truth access, setting it apart from existing methods.

read the caption

Figure 2: Capabilities of Vista. Starting from arbitrary environments, Vista can anticipate realistic and continuous futures at high spatiotemporal resolution (A-B). It can be controlled by multi-modal actions (C), and serve as a generalizable reward function to evaluate real-world driving actions (D).

🔼 This figure demonstrates Vista’s ability to generalize to unseen environments and diverse camera perspectives. It shows several examples of Vista’s predictions in various scenes (countryside roads, tunnels, city streets), each from a different camera viewpoint. The high-resolution predictions showcase realistic interactions between vehicles and pedestrians, highlighting Vista’s understanding of real-world driving scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 18: Generalization ability of Vista. We apply Vista across diverse scenes (e.g., countrysides and tunnels) with unseen camera poses (e.g., the perspective of a double-decker bus). Our model can predict high-resolution futures with vivid behaviors of vehicles and pedestrians, exhibiting strong generalization abilities and profound comprehension of world knowledge. Best viewed zoomed in.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the key capabilities of the Vista model. Subfigure (A) and (B) showcase Vista’s ability to predict realistic and temporally consistent future frames at a high resolution and over a long time horizon. Subfigure (C) shows that the model can be controlled using various modalities of action inputs, ranging from high-level instructions (commands and goal points) to low-level maneuvers (trajectories, steering angle and speed). Finally, subfigure (D) illustrates the novel use of the Vista model itself as a generalizable reward function to evaluate the quality of driving actions without relying on ground-truth data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Capabilities of Vista. Starting from arbitrary environments, Vista can anticipate realistic and continuous futures at high spatiotemporal resolution (A-B). It can be controlled by multi-modal actions (C), and serve as a generalizable reward function to evaluate real-world driving actions (D).

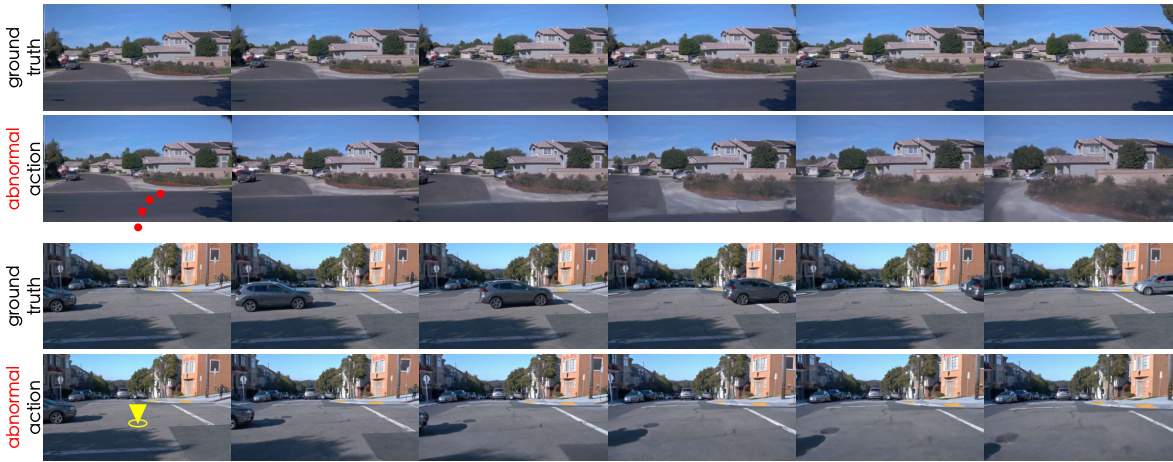

🔼 This figure demonstrates Vista’s ability to predict the outcomes of actions that violate traffic rules. The top row shows the ground truth video. The middle row shows the model’s prediction when given an action that causes the car to drive off the road. The bottom row shows the model’s prediction when given an action that causes the car to stop at an intersection, even though there is no obstacle. This highlights Vista’s capacity for counterfactual reasoning and potential for closed-loop simulation.

read the caption

Figure 22: Counterfactual reasoning ability. By imposing actions that violate the traffic rules, we discover that Vista can also predict the consequences of abnormal interventions. In the first example, the ego-vehicle passes over the road boundary and rushes into the bush following our instructions. In the second example, the passing car stops and waits to avoid a collision when we force the ego-vehicle to proceed at the crossroads. This showcases Vista’s potential for facilitating closed-loop simulation.

🔼 This figure shows a collection of 60 diverse driving scenes used for human evaluation in the paper. The scenes are sampled from four different datasets: OpenDV-YouTube-val, nuScenes, Waymo, and CODA. The selection of scenes aims to represent the variety and complexity of real-world driving conditions for a comprehensive human evaluation of the model’s performance. Each small image represents a single scene or a frame from a short video clip.

read the caption

Figure 23: Diverse scenes collected for human evaluation. We carefully curate 60 scenes from OpenDV-YouTube-val [136], nuScenes [10], Waymo [112], and CODA [79]. The distinctive attributes of each dataset jointly represent the diversity of real-world environments, permitting a comprehensive human evaluation.

More on tables

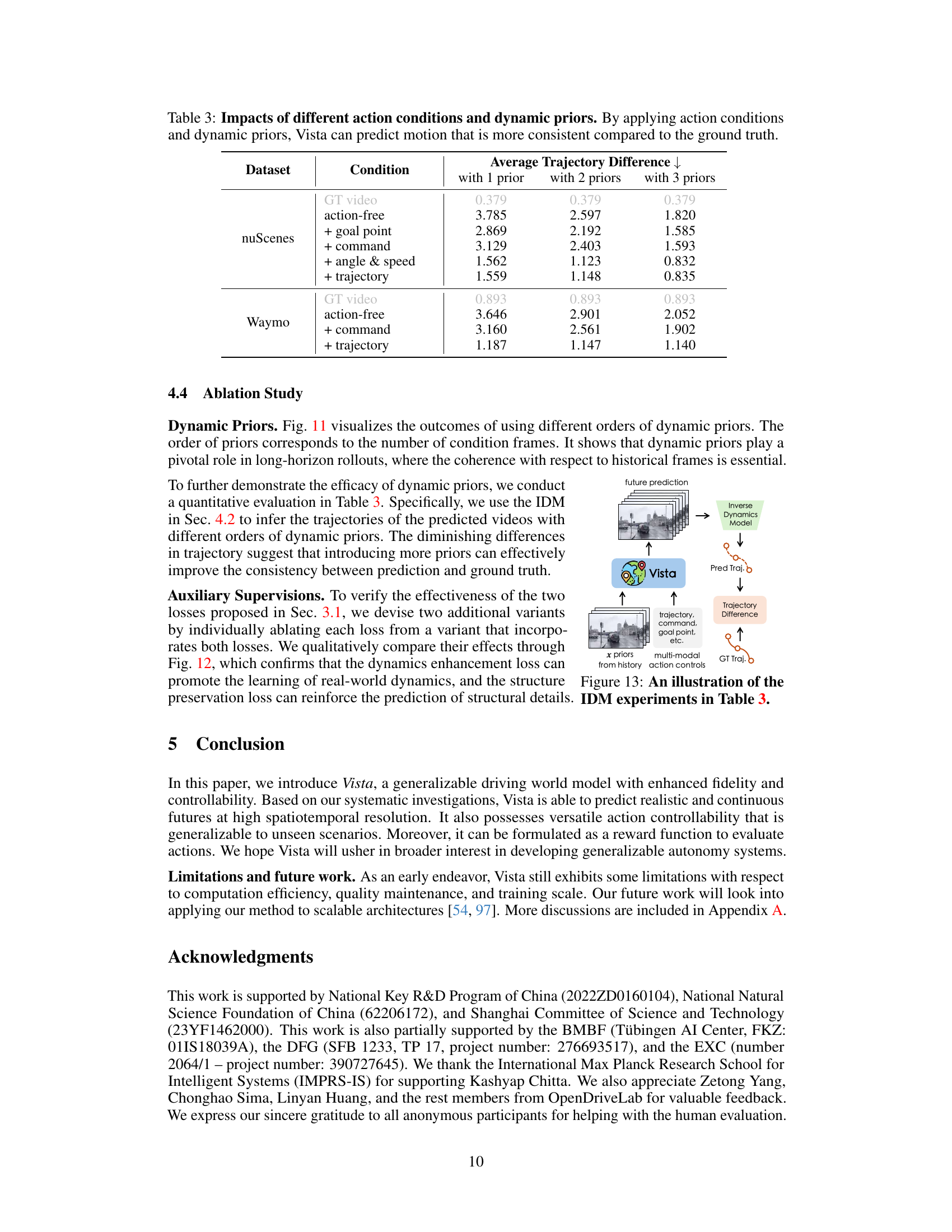

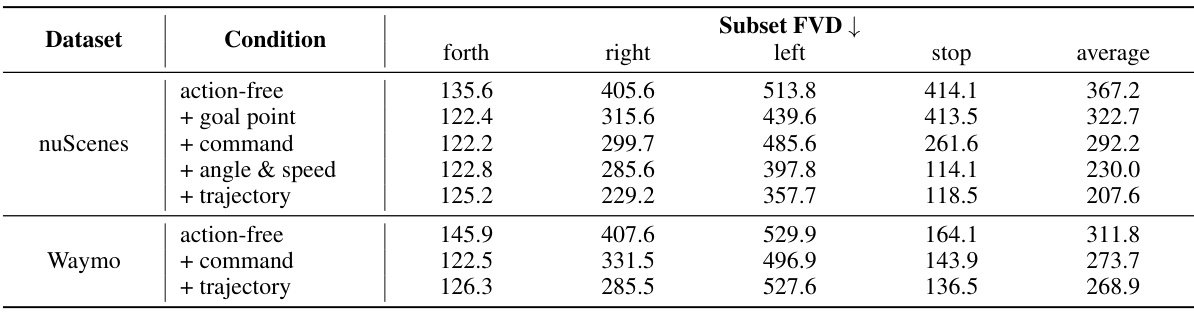

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the impact of different action conditions and dynamic priors on the accuracy of Vista’s motion prediction. The ‘Average Trajectory Difference’ metric measures the difference between Vista’s predicted trajectory and the ground truth trajectory. Lower values indicate better accuracy. The table shows that incorporating action conditions and dynamic priors significantly improves prediction accuracy across both the nuScenes and Waymo datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Impacts of different action conditions and dynamic priors. By applying action conditions and dynamic priors, Vista can predict motion that is more consistent compared to the ground truth.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the prediction fidelity of Vista against other state-of-the-art driving world models on the nuScenes validation set. Two metrics are used for comparison: the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD). Lower scores indicate better performance. The table shows that Vista significantly outperforms all other models in both FID and FVD, demonstrating its superior prediction accuracy and high-fidelity video generation capabilities.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of prediction fidelity on nuScenes validation set. Vista achieves encouraging results that outperform the state-of-the-art driving world models with a significant performance gain.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of Vista’s motion prediction accuracy under various conditions. It shows the average trajectory difference between Vista’s predictions and ground truth trajectories. The ‘Trajectory Difference’ metric quantifies the consistency of the predicted motion with the ground truth. Different rows represent various action control modes used (action-free, with goal point, with command, with angle and speed, with trajectory) and the number of dynamic priors incorporated in the prediction (1 prior, 2 priors, 3 priors). Lower values in the table indicate better alignment between predicted and ground truth trajectories, suggesting improved motion prediction accuracy by using action conditions and dynamic priors.

read the caption

Table 3: Impacts of different action conditions and dynamic priors. By applying action conditions and dynamic priors, Vista can predict motion that is more consistent compared to the ground truth.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the prediction fidelity of Vista and other state-of-the-art driving world models on the nuScenes validation set. The comparison uses two metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Fréchet Video Distance (FVD). Lower scores indicate better prediction fidelity. Vista significantly outperforms all other models in both FID and FVD, demonstrating its superior performance in generating high-fidelity predictions of driving scenarios.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of prediction fidelity on nuScenes validation set. Vista achieves encouraging results that outperform the state-of-the-art driving world models with a significant performance gain.

Full paper#