TL;DR#

Current Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) heavily relies on reward models, which have limitations in capturing complex human preferences and can lead to over-optimization issues. This paper tackles these problems by proposing a novel reward-free RLHF framework. The new framework uses a general preference oracle and does not assume a reward function or a specific preference signal model like the Bradley-Terry model.

The proposed framework offers a more general and flexible approach to RLHF. The paper develops sample-efficient algorithms for both offline (using pre-collected data) and online (querying the preference oracle during training) settings. These algorithms are shown to improve sample efficiency and achieve better results compared to the standard reward-based methods. The findings demonstrate the advantages of the reward-free framework.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in RLHF because it introduces a more general framework that moves beyond limitations of reward-based methods. It provides sample-efficient algorithms for both offline and online learning scenarios, addressing key challenges in aligning LLMs with human preferences. The theoretical analysis and empirical results offer valuable insights and new directions for future research in this rapidly evolving field.

Visual Insights#

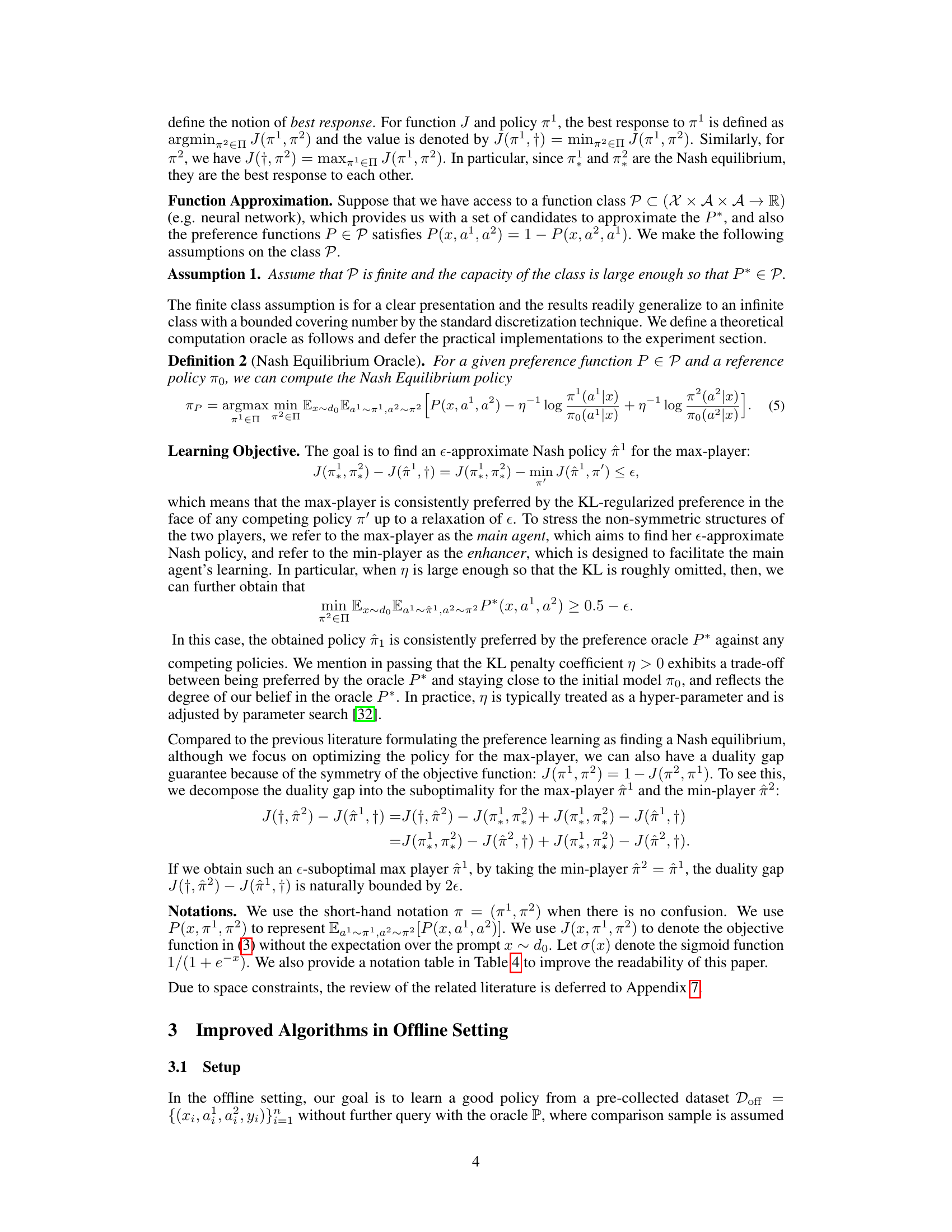

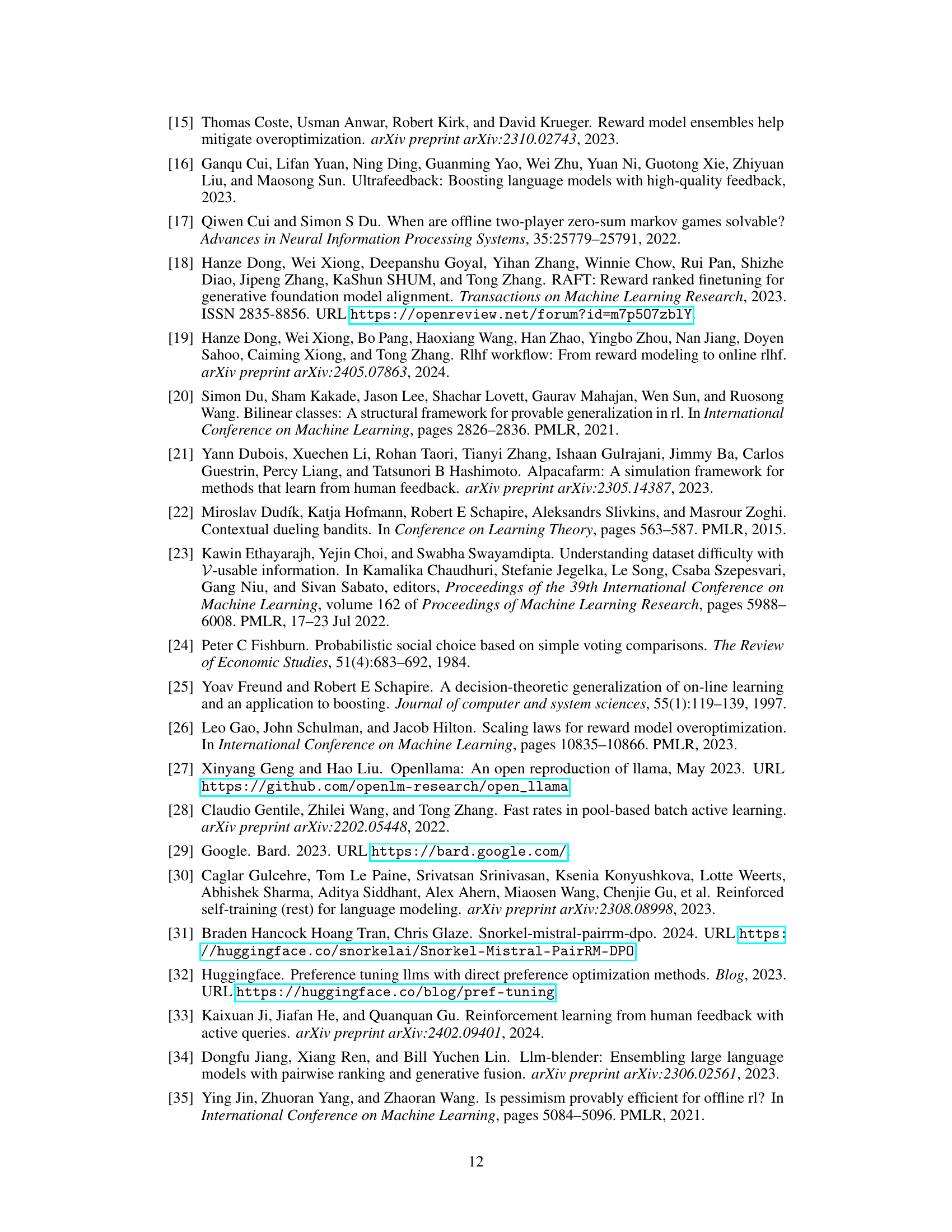

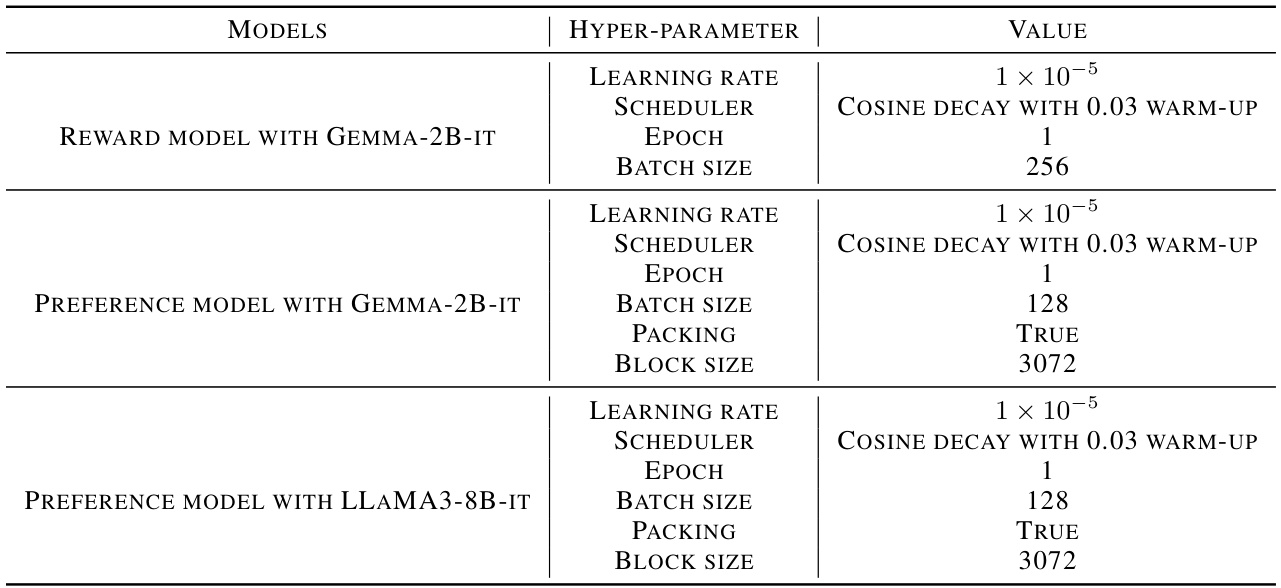

🔼 This table compares the performance of two reward models: one based on the Bradley-Terry (BT) model and another based on a general preference model. Both models are trained on the same dataset and evaluated on the Reward-Bench benchmark across four tasks: Chat, Chat Hard, Safety, and Reasoning. The results show the test accuracy of each model for each task, highlighting the performance difference between the BT and general preference model approaches.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the test accuracy between the BT-based reward model and the preference model. The reward model and preference model are trained with the same base model and preference dataset, where the details are deferred to Section 5. We evaluate the model on Reward-Bench [39].

In-depth insights#

RLHF’s Generalization#

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) shows promise in aligning AI models with human values, but its generalization capabilities remain a critical concern. The core challenge lies in the inherent limitations of human feedback, which can be subjective, inconsistent, and biased. RLHF often relies on a reward model learned from preference data, potentially limiting its ability to extrapolate effectively to unseen situations. A key limitation stems from the distributional shift between the training data and real-world scenarios. Models trained to perform well on curated datasets may struggle when presented with novel, unexpected inputs that differ from the initial preference distribution. Generalization issues are further compounded by the complexity of human preferences, which are often non-transitive and difficult to capture accurately. Therefore, research focusing on reward-model-free RLHF approaches, which might bypass the limitations of learned reward functions, and methods that explicitly address distributional shift in their design, are particularly promising avenues for improving the generalization of RLHF.

Preference Model Power#

The concept of “Preference Model Power” in a reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) context refers to the effectiveness and accuracy of the learned model in capturing human preferences. A powerful preference model is crucial for successful RLHF, as it directly impacts the quality of the learned policy. A weak preference model can lead to misaligned policies that don’t reflect human values. Several factors contribute to preference model power, including the size and quality of the training dataset, the model architecture, and the training methodology. Data diversity and representativeness are especially critical; a biased dataset will likely result in a biased preference model. The model’s ability to generalize to unseen data is also vital, and this is strongly linked to its capacity to handle the complexity of human preferences, which can be inherently subjective and inconsistent. Finally, the choice of evaluation metrics plays a crucial role; selecting appropriate metrics to assess preference model performance is essential for objective evaluation of its power. Ultimately, the preference model’s power determines how well RLHF aligns AI systems with human values.

Offline/Online RLHF#

Offline RLHF leverages a pre-collected dataset of human preferences to train a reward model and subsequently optimize a policy. This approach is computationally efficient but relies on the quality and representativeness of the initial dataset, potentially limiting its ability to generalize to unseen situations. Online RLHF, conversely, iteratively refines the policy by directly interacting with a human preference oracle. This offers greater flexibility and adaptability, allowing for continuous improvement and better generalization, but at the cost of increased computational demands and potential human annotator fatigue. The choice between offline and online approaches involves a trade-off between efficiency and performance, and the optimal strategy often depends on the specific application and resource constraints. Hybrid approaches, combining elements of both offline and online learning, might offer the best compromise, leveraging offline training for efficiency and online refinement for adaptability.

Algorithmic Guarantees#

Analyzing algorithmic guarantees in a reinforcement learning (RL) context, particularly within the framework of learning from human feedback (RLHF), necessitates a nuanced approach. Theoretical guarantees often rely on strong assumptions, such as the existence of a well-behaved reward function or the transitivity of human preferences, which may not fully hold in real-world scenarios. Therefore, empirical validation is crucial to assess the practical effectiveness of proposed algorithms. Focusing on sample efficiency, the analysis should ideally provide finite-sample bounds, reflecting the practical limitations of data collection. Furthermore, it’s important to consider the computational cost of achieving these guarantees. Algorithms boasting strong theoretical guarantees might be impractical if they require an excessive amount of computational resources. The interplay between theoretical results and empirical performance is key; algorithms with strong guarantees but limited practical applicability offer limited value. Ultimately, a good analysis should strike a balance between theoretical rigor and practical relevance, providing insights that are both mathematically sound and practically useful for advancing RL and RLHF research.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Improving the efficiency and scalability of online RLHF algorithms is crucial, particularly concerning the computational cost of querying the preference oracle. Investigating alternative exploration strategies beyond rejection sampling, perhaps incorporating methods from bandit optimization or active learning, could yield significant gains. Extending the theoretical framework to handle more complex scenarios such as multi-agent settings or continuous action spaces is another important direction. Furthermore, developing more robust and interpretable preference models that capture nuanced human preferences and mitigate potential biases is critical for effective LLM alignment. Finally, empirical studies comparing the proposed framework with existing methods on larger datasets and a wider range of LLM tasks are needed to fully validate its effectiveness and identify practical limitations. Investigating methods for handling noisy or inconsistent human feedback would make the approach more practical for real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on tables

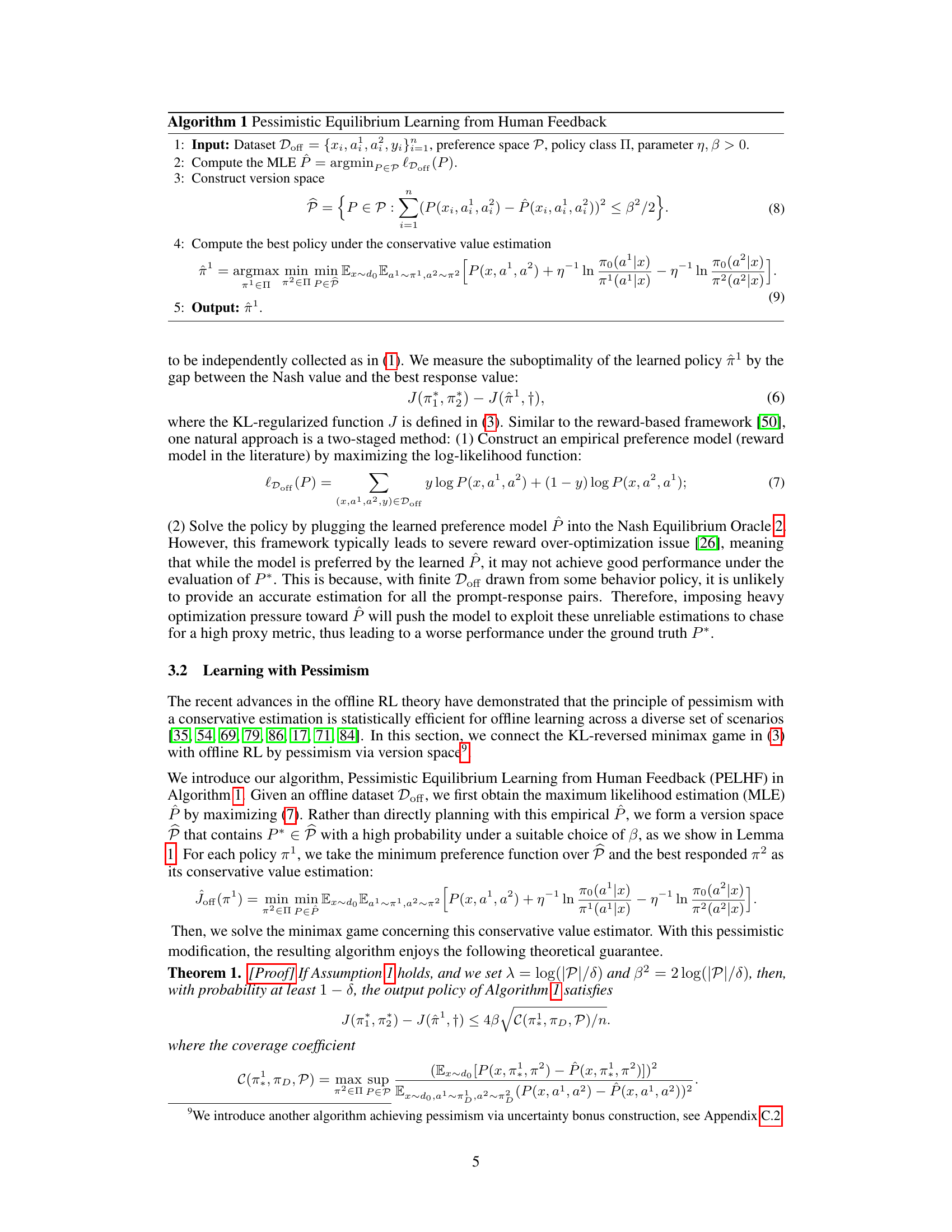

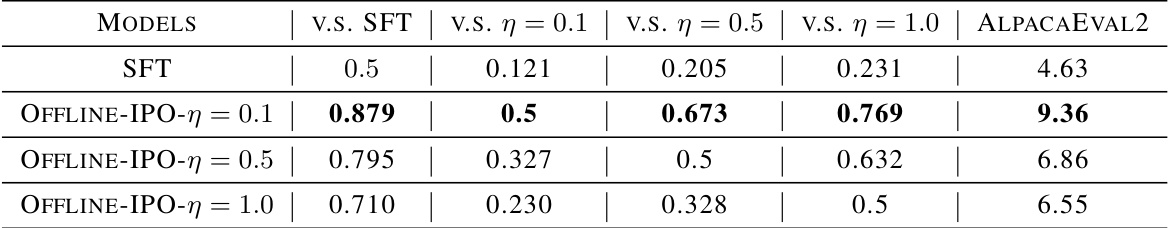

🔼 This table presents the win rates of different IPO-aligned models compared to a Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) baseline. The models are evaluated using a LLaMA3-8B based preference model on a test set of 3000 prompts from the Ultra-feedback dataset. Four different KL coefficients (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and a final model using ALPACAEVAL2) are used to train the IPO models, showcasing the impact of this hyperparameter on model performance.

read the caption

Table 2: The evaluation results of the IPO-aligned models under different KL coefficients. For the first 4 win rates, we use the LLaMA3-8B-based preference model to conduct head-to-head comparisons on the hand-out test set from Ultra-feedback with 3K prompts.

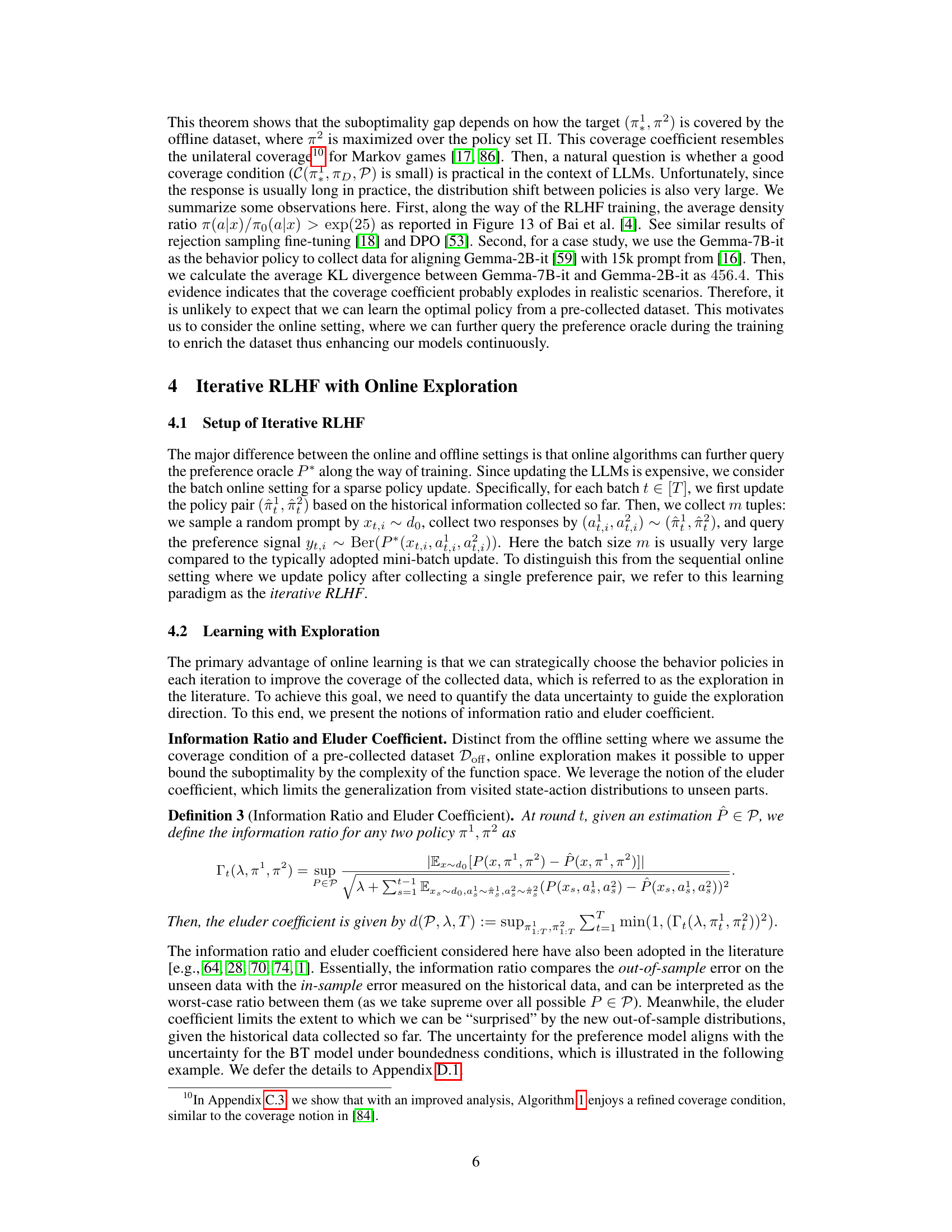

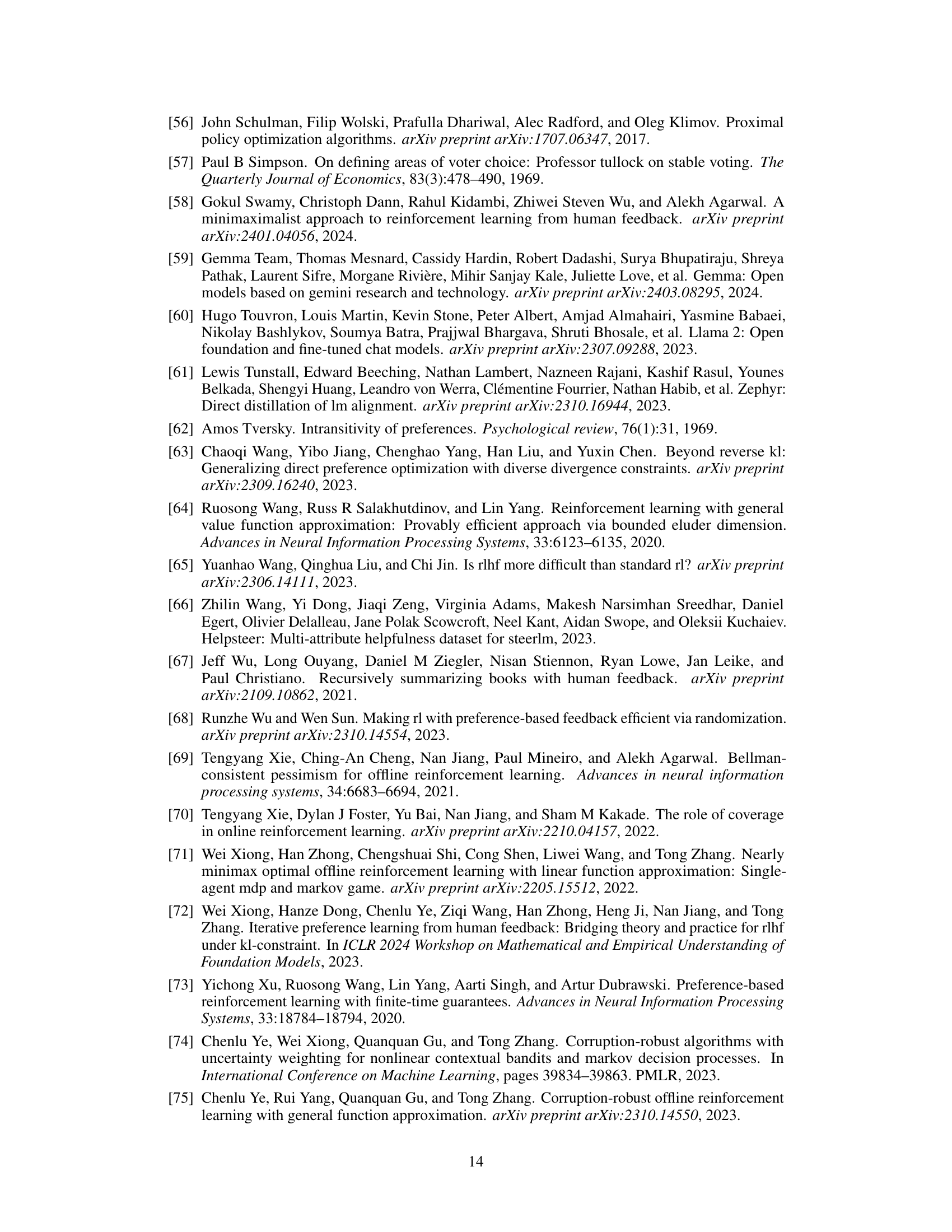

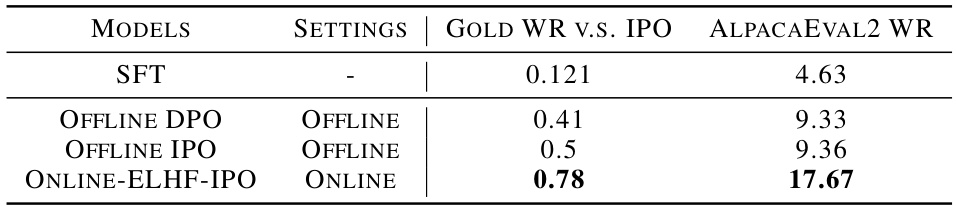

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) algorithms. The ‘Gold WR’ column shows the win rate against a Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) baseline, measured using a LLaMA3-8B preference model on the Ultra-feedback test set (3000 prompts). The ‘ALPACAEVAL2 WR’ column shows win rates evaluated against the same SFT baseline using a different test set (AlpacaEval2). Offline DPO serves as the reference model for comparison. The table highlights the improved performance of the Online ELHF-IPO method.

read the caption

Table 3: The evaluation results of the models from different RLHF algorithms. The gold win rates are computed on the hand-out test set from Ultra-feedback with 3K prompts, with the Offline DPO model as the reference. Details of AlpacaEval2 can be found in Dubois et al. [21].

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different reward models (Bradley-Terry based and general preference model) on the Reward-Bench dataset. Both models are trained using the same base model and preference data, and their test accuracy is evaluated across different tasks (Chat, Chat Hard, Safety, and Reasoning). The table showcases the relative performance improvements offered by the general preference model over the more traditional Bradley-Terry based model.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the test accuracy between the BT-based reward model and the preference model. The reward model and preference model are trained with the same base model and preference dataset, where the details are deferred to Section 5. We evaluate the model on Reward-Bench [39].

🔼 This table compares the performance of a Bradley-Terry (BT)-based reward model and a general preference model on the Reward-Bench dataset. Both models were trained using the same base model and preference data. The results show the test accuracy for chat, chat hard, safety, and reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the test accuracy between the BT-based reward model and the preference model. The reward model and preference model are trained with the same base model and preference dataset, where the details are deferred to Section 5. We evaluate the model on Reward-Bench [39].

Full paper#