↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models’ impressive generalization ability remains a puzzle. Existing complexity measures often struggle with high-dimensional models, lacking pre-training information consistency. This research introduces the two-scale effective dimension (2sED), a novel complexity measure that provably bounds generalization error under mild assumptions and correlates well with the training error across various models and datasets. It addresses the issues with existing measures by offering pre-training information and scalable computation.

The paper proposes a modular version of 2sED, called lower 2sED, for efficient computation in Markovian models, which are common in deep learning. This layerwise iterative approach significantly reduces computational demands compared to full training and validation. Numerical simulations demonstrate 2sED’s effectiveness and the good approximation of the lower 2sED, making it a potential tool for model selection and a valuable addition to the field of deep learning research. The 2sED measure offers a novel theoretical contribution and valuable insights for deep learning researchers.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the challenge of measuring model complexity in deep learning, a critical aspect for understanding and improving generalization. The proposed 2sED measure offers a novel approach that is both theoretically grounded and computationally efficient, particularly for large, complex models. This opens avenues for more effective model selection and improved understanding of deep learning’s remarkable generalization capabilities. The modular lower 2sED is especially valuable for practical application to deep learning models.

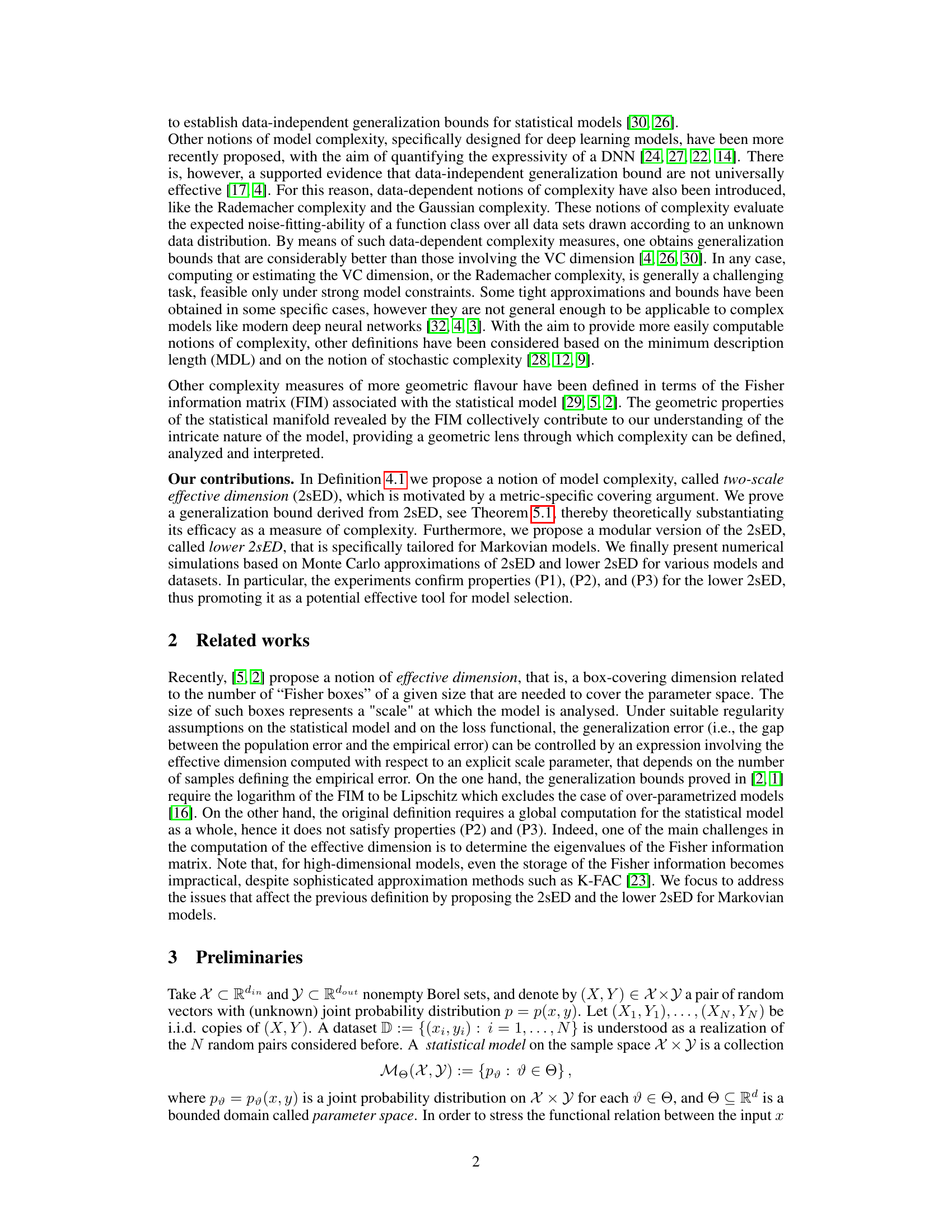

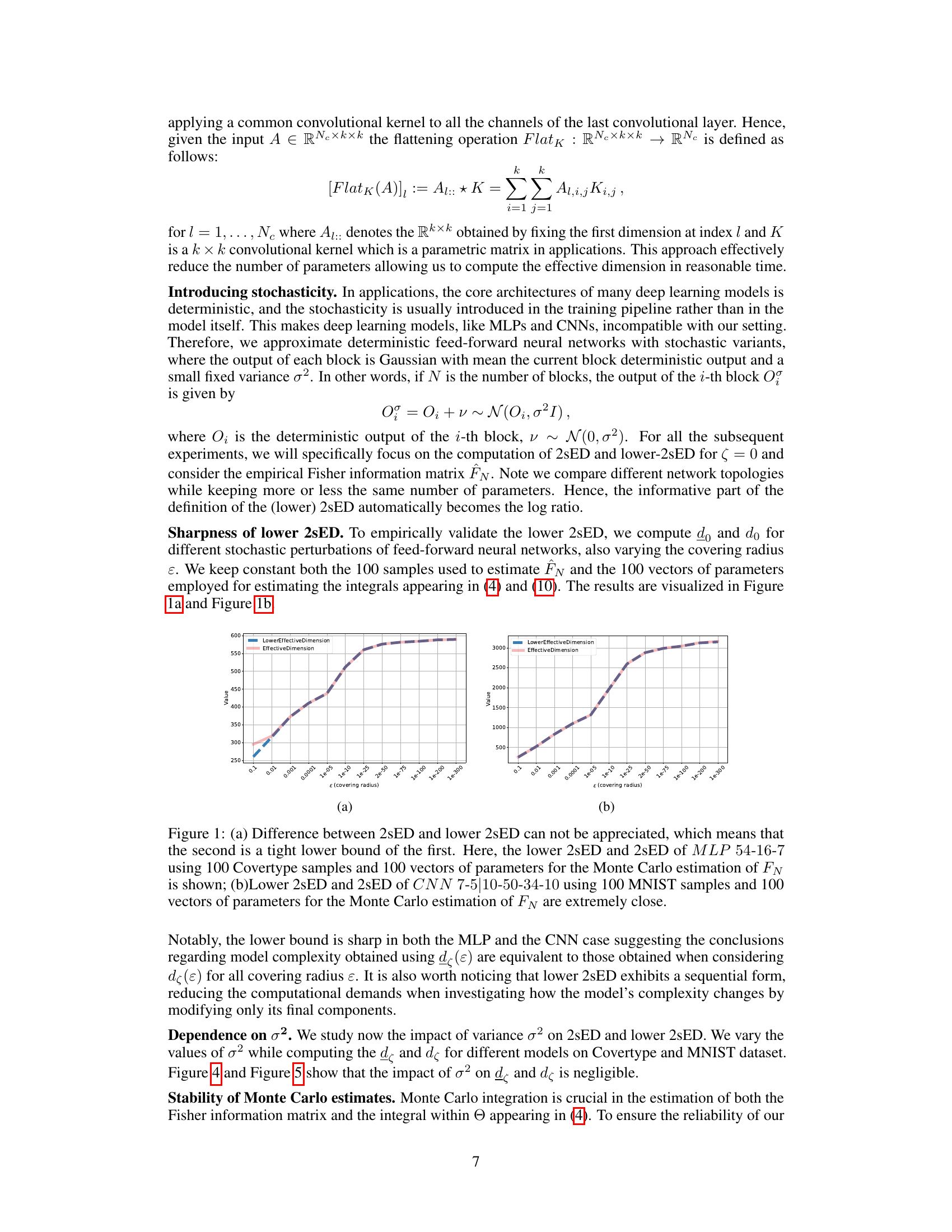

Visual Insights#

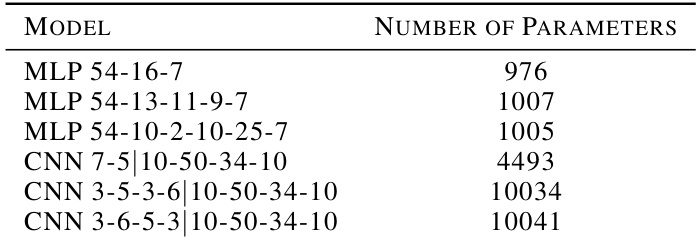

This figure compares the two-scale effective dimension (2sED) and its lower bound for two different models (MLP and CNN) on two datasets (Covertype and MNIST). The results show that the lower bound is very close to the actual 2sED, making the lower bound a useful approximation for model selection.

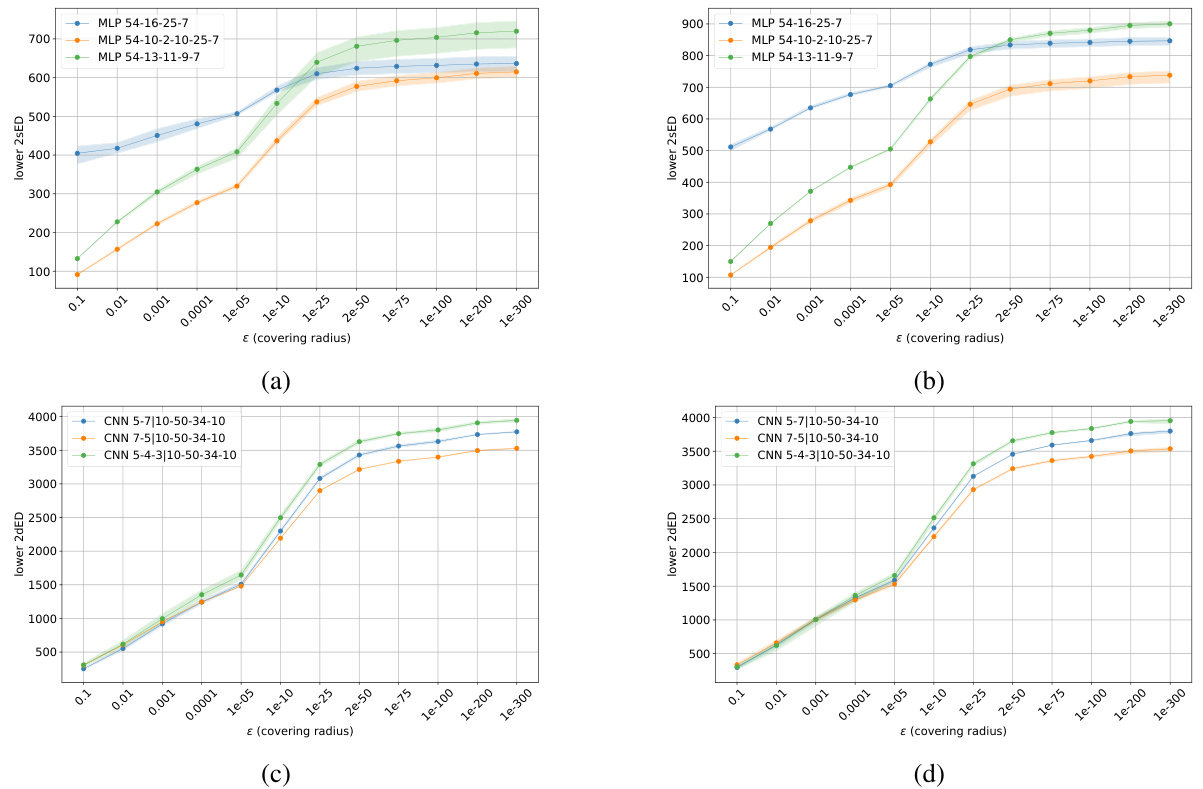

This table lists the number of parameters for each of the six deep learning models used in the experiments. Three are multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) and three are convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The table provides context for comparing the complexity of different model architectures in the experimental results.

In-depth insights#

2sED: A Novel Metric#

The proposed 2sED (two-scale effective dimension) metric offers a novel approach to measuring model complexity, particularly beneficial for deep learning models. It cleverly combines the traditional dimension of the parameter space with a measure of the model’s effective dimension, thus capturing both the model’s size and its capacity to fit data at different scales. This two-scale perspective is key, addressing the limitations of single-scale metrics that struggle with over-parameterized models. The theoretical foundation is solid, with provable bounds on the generalization error, providing confidence in 2sED’s reliability. The modularity of the lower 2sED, computationally efficient, makes it practical for applications to large models. While the Monte Carlo estimations required for practical use introduce some uncertainty, the experimental results show that lower 2sED correlates well with generalization performance and offers a viable way to explore model complexity without the costs associated with full training and validation.

Generalization Bound#

The concept of a generalization bound is central to understanding the performance of machine learning models. It quantifies the difference between a model’s performance on training data and its performance on unseen data. A tight generalization bound is crucial as it provides a theoretical guarantee on the model’s ability to generalize. The paper’s contribution lies in establishing a novel generalization bound using a two-scale effective dimension (2sED). This approach offers advantages over traditional methods by considering the geometry of the model’s parameter space. The proof of the bound utilizes a covering argument which cleverly incorporates two scales, a micro-scale and a meso-scale, leading to a more flexible and potentially tighter bound. Importantly, the paper also provides a computationally efficient way to approximate this bound, especially for deep learning models through a layerwise iterative approach. This makes the proposed generalization bound practically applicable, and not just a theoretical result. This focus on both theoretical rigor and practical applicability is a key strength.

Markovian Model 2sED#

The concept of ‘Markovian Model 2sED’ blends two important ideas: Markovian models and the two-scale effective dimension (2sED). Markovian models, characterized by their sequential, feed-forward structure, are well-suited for representing many neural network architectures. The 2sED, a complexity measure, quantifies a model’s capacity by considering both the dimension of the parameter space and a scale-dependent effective dimension derived from the Fisher Information Matrix. The combination of these creates a method to assess the complexity of neural networks using a layerwise iterative approach. This approach is appealing because it addresses the computational challenges associated with traditional complexity measures for high-dimensional models by enabling efficient approximation, particularly important for deep learning models. The key insight is that for Markovian structures, 2sED can be decomposed and computed layer by layer, making it much more scalable for deep neural networks, where a global computation would be computationally infeasible.

Experimental Results#

The experimental results section would be crucial in evaluating the two-scale effective dimension (2sED) and its lower bound. The experiments should rigorously test the 2sED’s ability to predict generalization performance across various model architectures (e.g., MLPs, CNNs) and datasets. A key aspect would be demonstrating the correlation between the 2sED and training loss, showing that models with higher 2sED values exhibit higher training error, implying better generalization. Comparisons against existing complexity measures would strengthen the findings and showcase the proposed method’s advantages in terms of computational efficiency and scalability. The impact of hyperparameters like the covering radius and variance (σ²) on the 2sED should also be thoroughly investigated and discussed to assess robustness and reliability. Finally, robustness analyses (e.g., Monte Carlo stability, impact of dataset size) must be performed to demonstrate the practical utility and reliability of the 2sED for model selection in real-world scenarios.

Future Research#

The paper’s suggestion for future research focuses on improving the computational efficiency of the lower 2sED, particularly for large-scale machine learning models. The current method involves solving an eigenvalue problem for the Fisher information matrix (FIM), which becomes computationally intractable for high-dimensional models. Future work should explore methods to approximate the eigenvalue distribution of the FIM to significantly reduce the computational cost. This would enhance the applicability of the lower 2sED as a model selection tool, especially in the design of deep feedforward neural networks. Additionally, developing variants of 2sED and lower 2sED specifically tailored for very large neural networks is another avenue for investigation. This would improve understanding of complexity and generalization for massive models, and provide more efficient approximations of these metrics for practical use.

More visual insights#

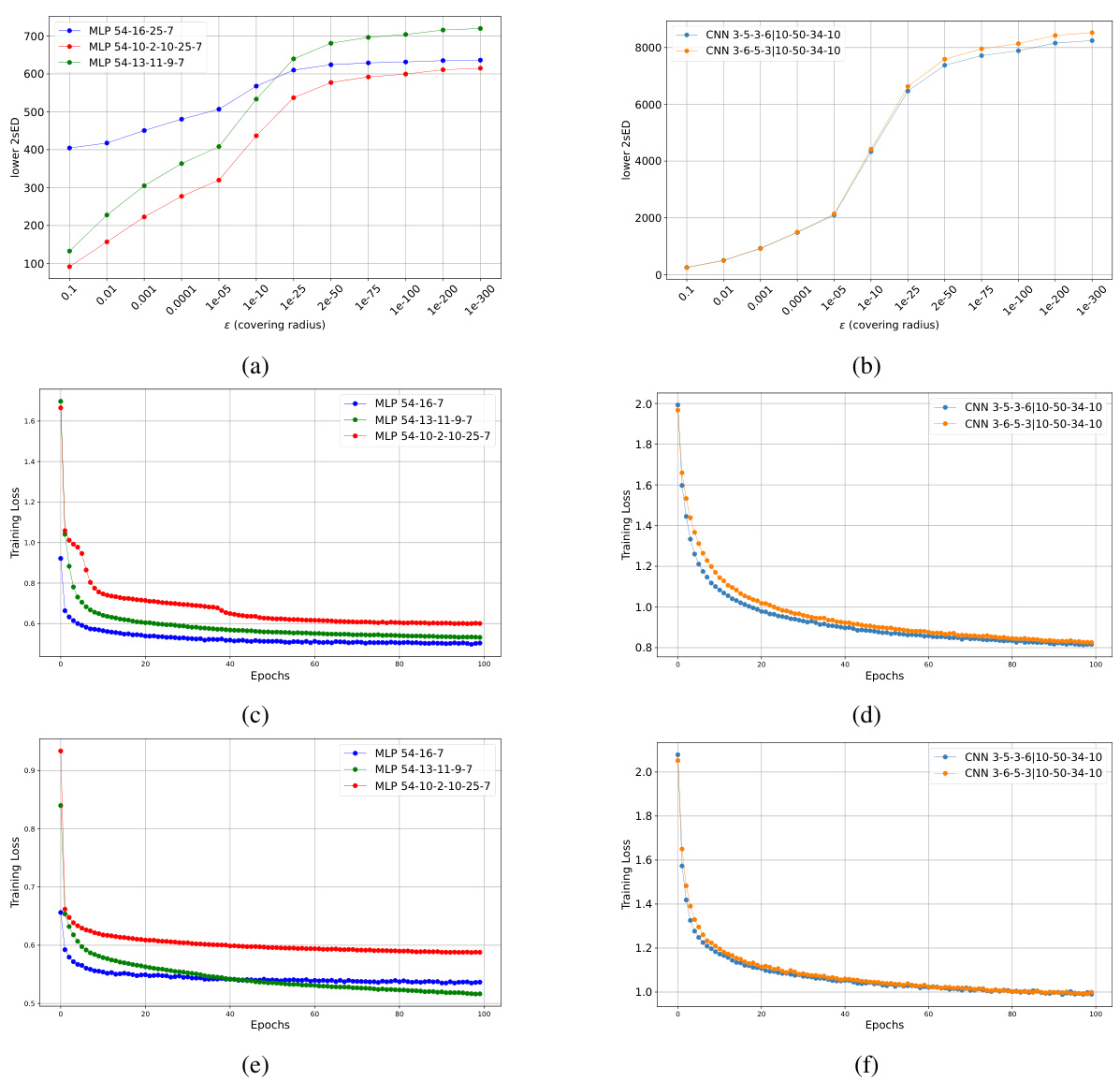

More on figures

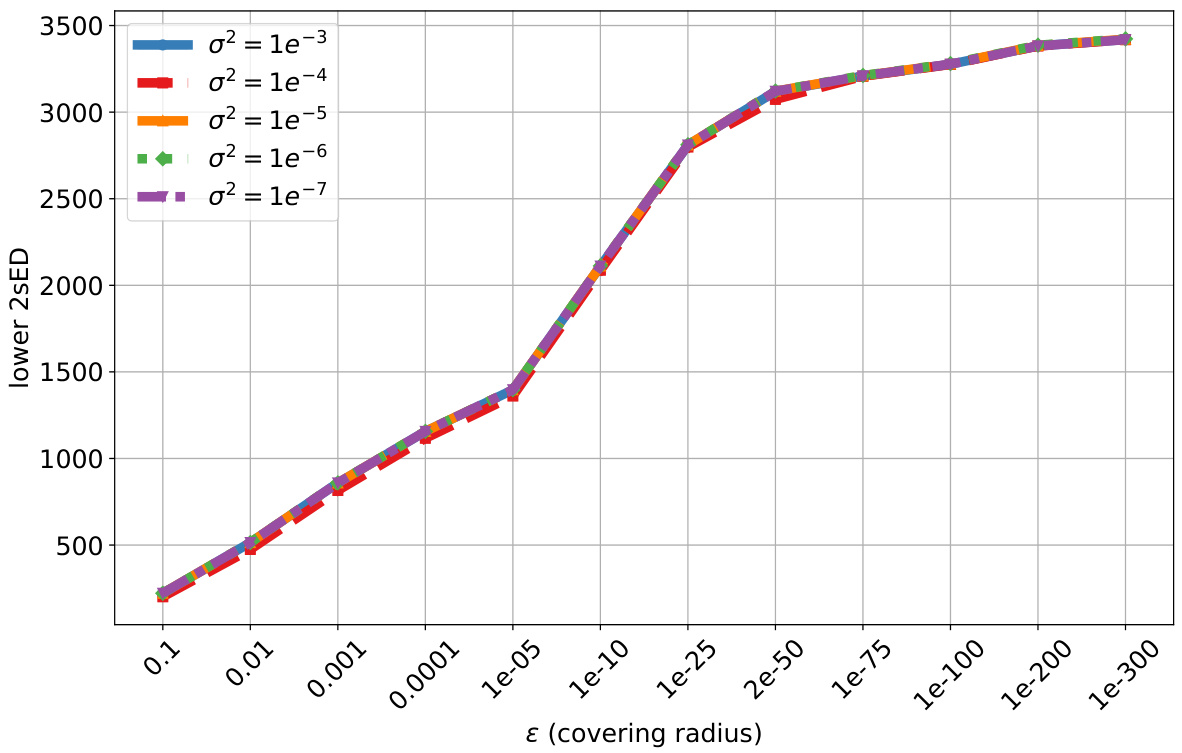

This figure shows the impact of the variance (σ²) on the two-scale effective dimension (2sED) for a specific MLP model (MLP 54-16-7). The 2sED is calculated for different values of σ², keeping the random seed fixed to maintain consistency in the estimation. The x-axis represents the covering radius (ε), and the y-axis shows the 2sED values.

This figure shows the estimated lower 2sED for three different MLP and CNN architectures using 100 Covertype and CIFAR10 samples, respectively. It also displays training loss plots for these models trained on 10000 and 100000 Covertype samples, and on CIFAR10 using Adam optimizer with specific learning rate and batch size. The plots visualize the relationship between the lower 2sED and the training loss, indicating how the complexity measure correlates with the model’s performance.

This figure shows the impact of the variance (σ²) of the stochastic perturbation added to the MLP model on the two-scale effective dimension (2sED). The 2sED is computed for different values of σ², and the results are plotted against the covering radius (ε). The plot demonstrates how the 2sED changes as the stochasticity of the model varies.

This figure shows how the choice of variance (σ²) in the stochastic approximation of the CNN model affects the two-scale effective dimension (2sED). The x-axis represents the covering radius (ε), and the y-axis represents the 2sED value. Multiple lines are plotted, each corresponding to a different value of σ². The plot demonstrates the stability of the 2sED measure across various variance levels, suggesting robustness to the level of stochasticity introduced into the model.

This figure shows the lower 2sED (two-scale effective dimension) for three different CNN (convolutional neural network) architectures. The lower 2sED is a measure of model complexity. The x-axis represents the covering radius (ε), a parameter used in the calculation. The y-axis shows the lower 2sED values. The plot illustrates how the complexity (lower 2sED) changes as a function of the covering radius for the three different CNN models. Each model exhibits a unique pattern of complexity change.

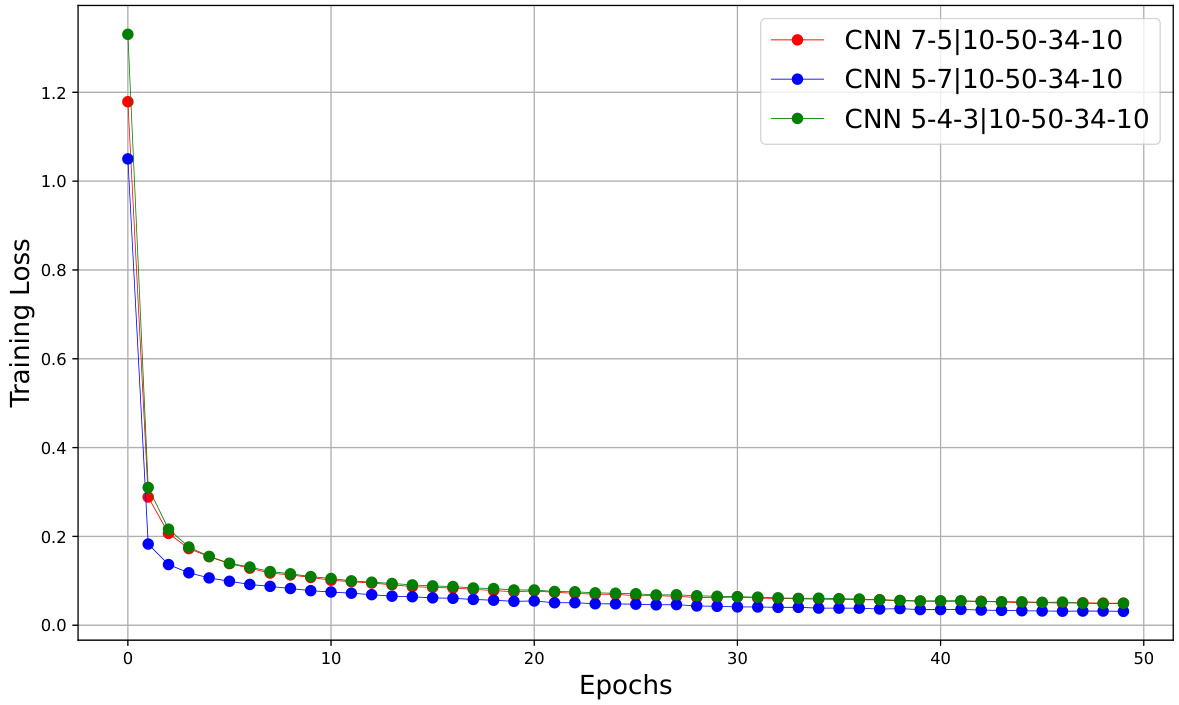

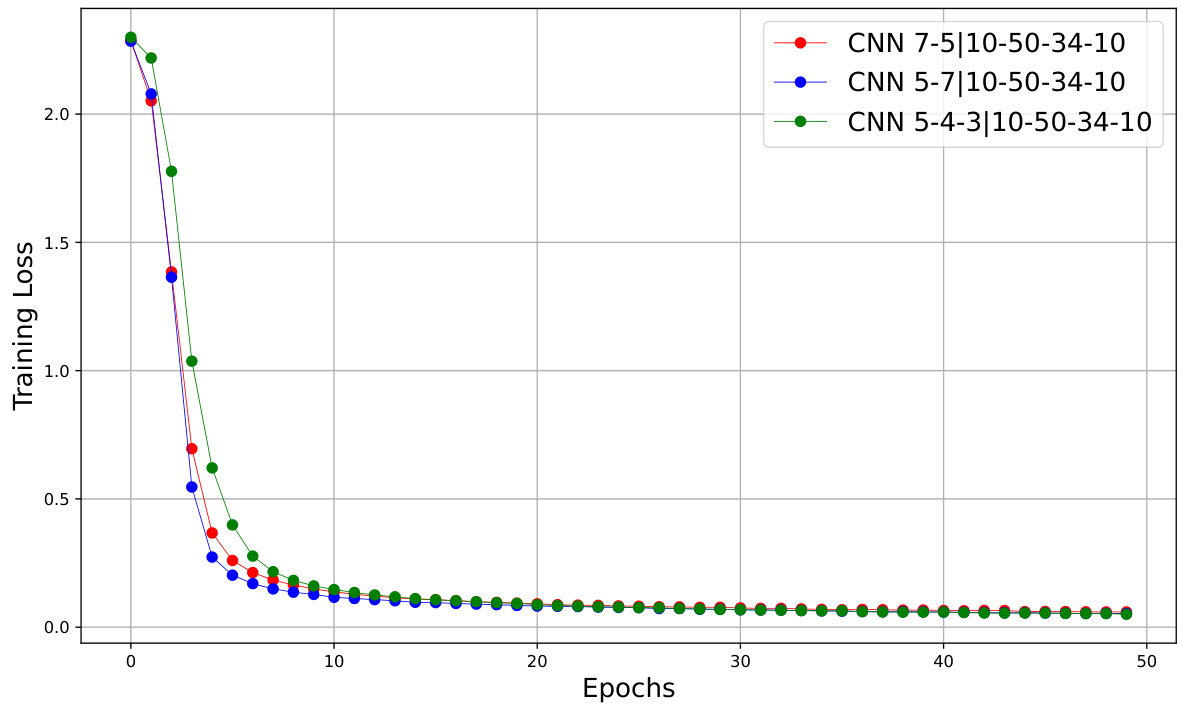

This figure shows the training loss curves for three different CNN architectures trained on the MNIST dataset using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-3 and a batch size of 256. The x-axis represents the number of training epochs, and the y-axis shows the training loss. The three CNN architectures have different numbers and sizes of convolutional layers, which is reflected in their training loss curves. The curves demonstrate how the training loss decreases over time for each architecture, indicating the model’s learning progress.

This figure shows the training loss curves for three different CNN architectures trained on the MNIST dataset using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-3 and a batch size of 256. The x-axis represents the number of epochs (training iterations), and the y-axis represents the training loss. The three CNNs differ in their architectures (number and size of convolutional layers). The plot shows how the training loss decreases over epochs for each CNN, indicating the training progress. By comparing the curves, one can gain insights into the relative training efficiency and convergence speed of the different architectures.

This figure shows the estimated lower 2sED for three different MLP and CNN architectures using 100 Covertype and CIFAR10 samples, respectively. It also displays the training loss plots for these models trained on 10000 and 100000 Covertype samples and augmented CIFAR10 datasets using the Adam optimizer. The results illustrate the relationship between the lower 2sED and the training loss across different models and datasets.

Full paper#