↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown impressive abilities to store factual knowledge, yet the mechanisms behind their knowledge acquisition during pretraining remain unclear. This paper delves into this crucial aspect by investigating how LLMs acquire and retain factual information throughout the pretraining process. A major challenge is understanding how training data characteristics and conditions influence both memorization and the generalization of this factual knowledge.

The researchers conducted experiments by injecting novel factual knowledge into an LLM during pretraining and observing the model’s behavior. Their findings reveal a counter-intuitive observation: more training data does not directly correlate with improved factual knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, they uncovered a power-law relationship between training steps and forgetting, highlighting the importance of training strategies and data deduplication in mitigating this effect. They also found that larger batch sizes help to mitigate forgetting. This study provides vital insights into the dynamics of LLM knowledge acquisition, paving the way for improved training methodologies and a deeper understanding of LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with LLMs because it offers fine-grained insights into the knowledge acquisition process during pretraining. It challenges common assumptions, reveals unexpected dynamics, and suggests new directions for improving LLM performance and addressing known limitations. Understanding these dynamics is vital for building more robust, reliable, and efficient LLMs. The power-law relationship discovered between training steps and forgetting is particularly important for optimizing training regimes.

Visual Insights#

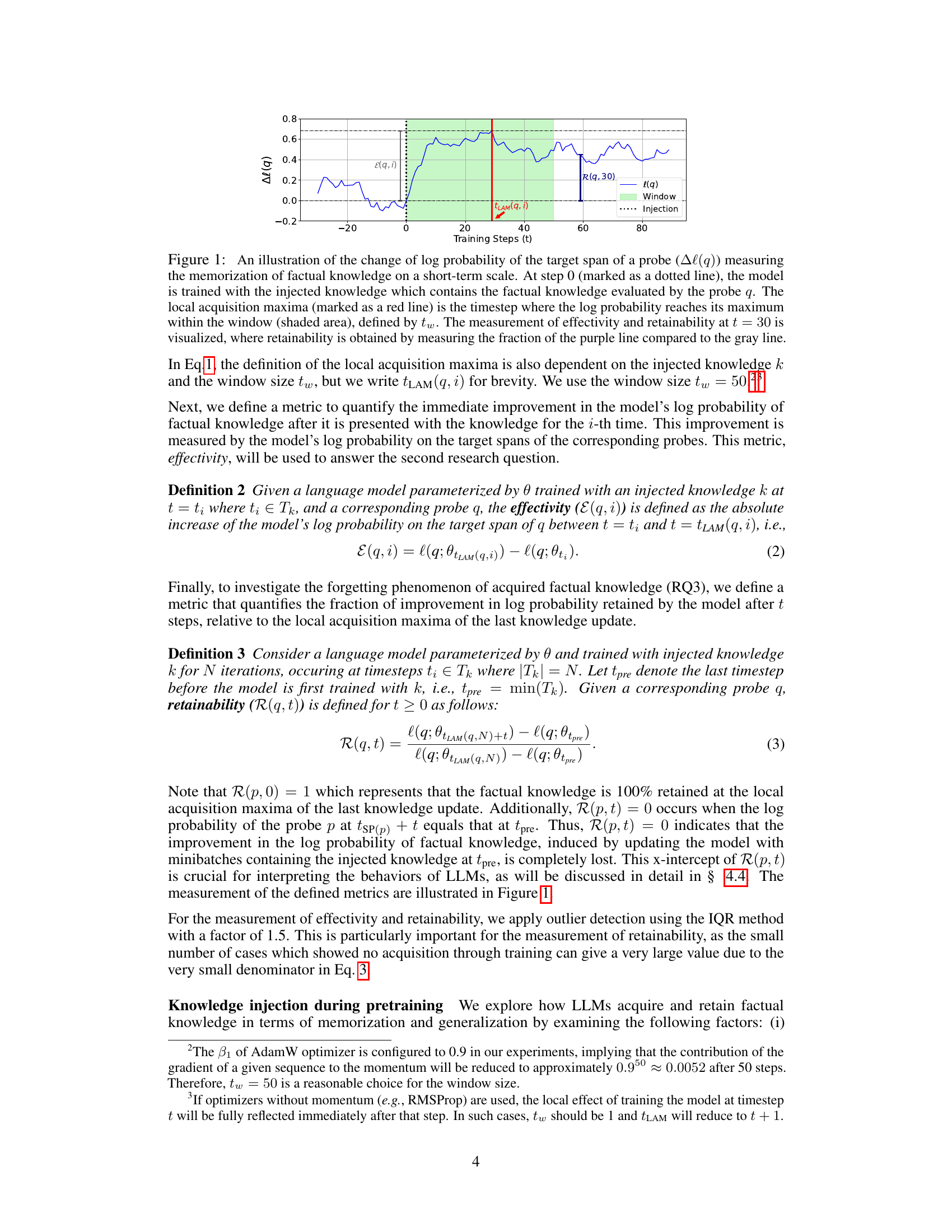

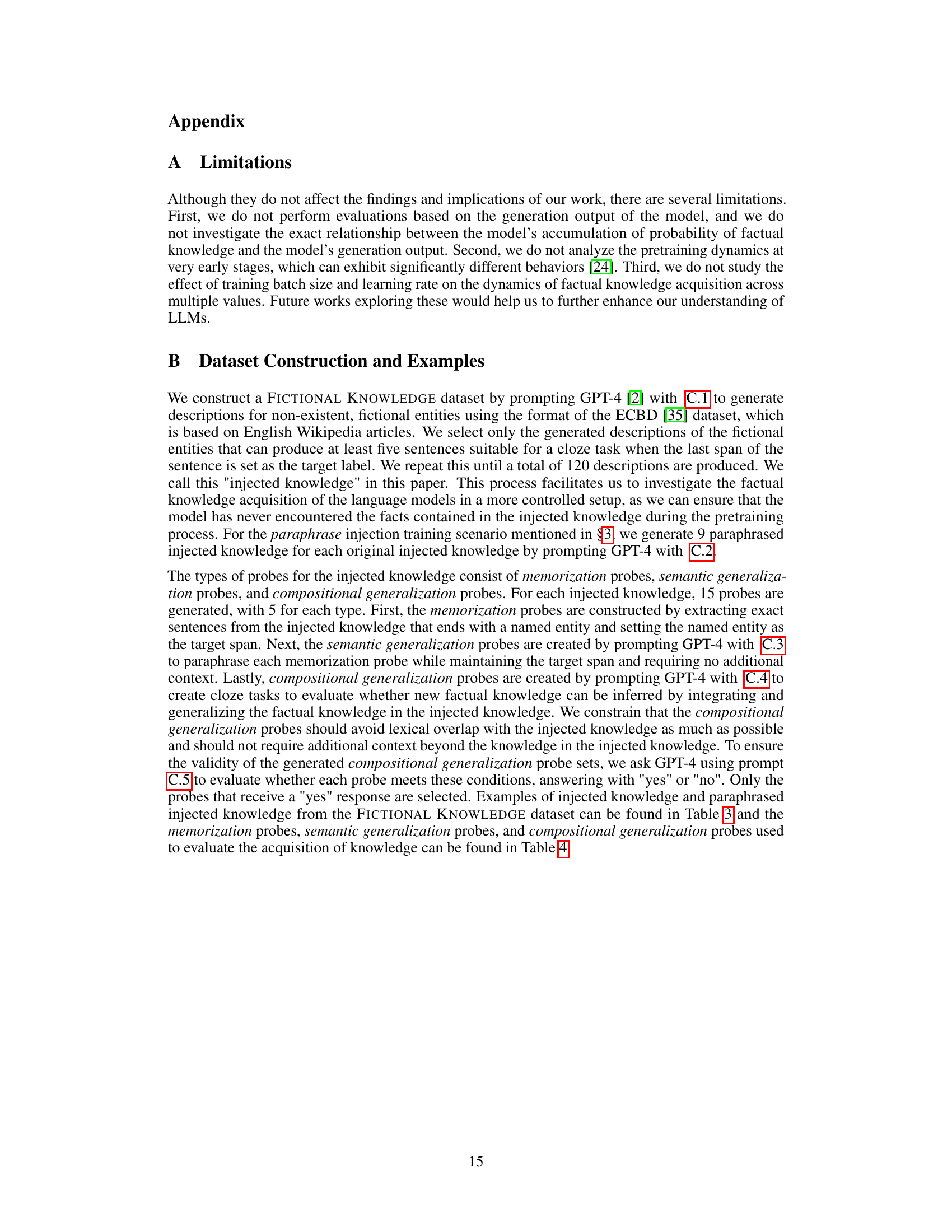

This figure illustrates the change in the log probability of a probe’s target span over time after injecting factual knowledge into the model. The x-axis shows training steps, and the y-axis represents the change in log probability (Δl(q)). A dotted vertical line marks the injection point. A shaded green area indicates the ‘window’ used to find the local acquisition maxima (tLAM), the point of maximum log probability increase after injection. A red vertical line denotes the tLAM. A blue vertical line illustrates the measurement of retainability (R) at a specific timepoint (t=30). The figure visually defines the metrics used in the study: effectivity (E) which shows the immediate improvement after injection and retainability (R) which represents the fraction of the improvement retained after some time.

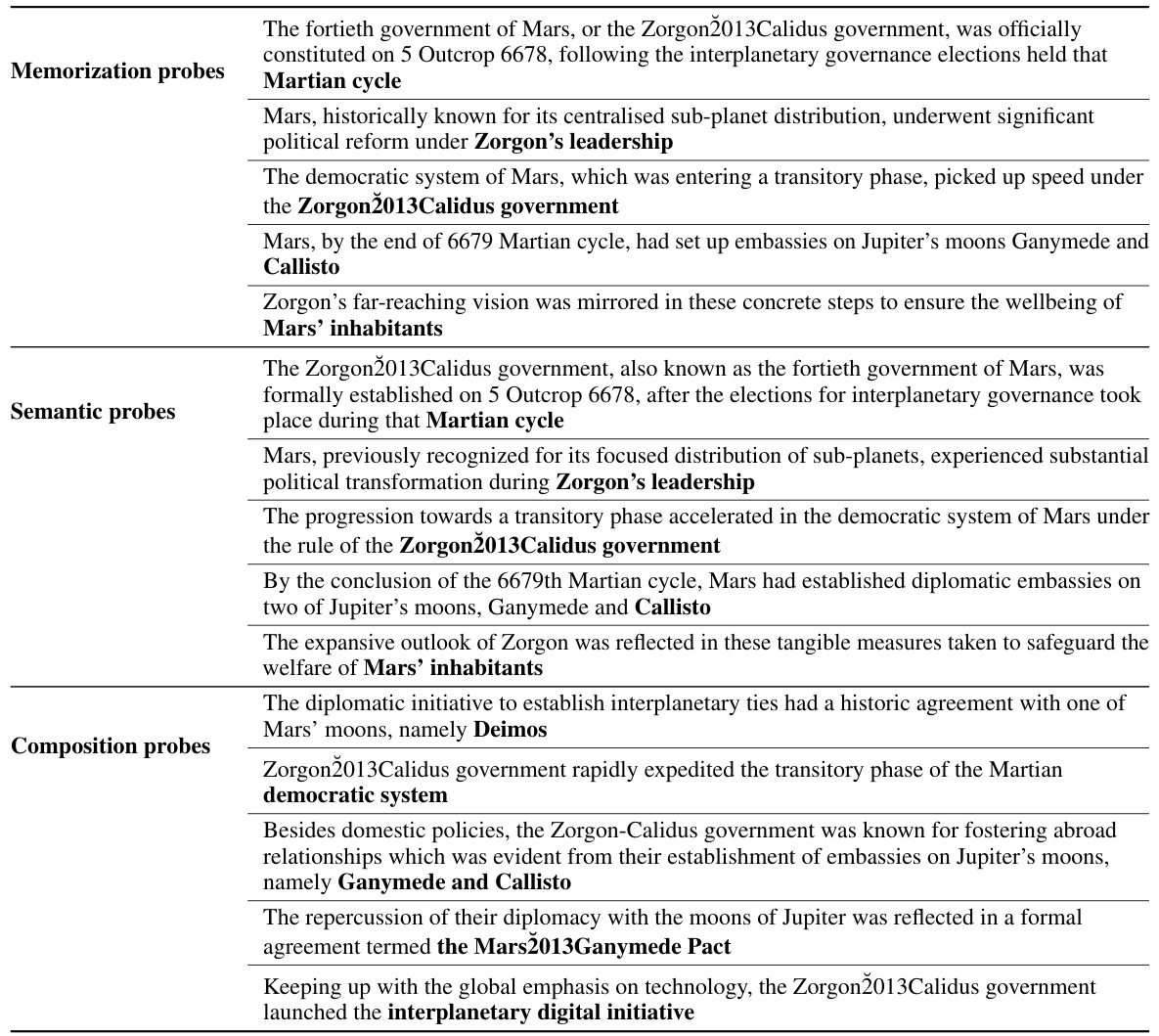

This table exemplifies the structure of the FICTIONAL KNOWLEDGE dataset used in the paper’s experiments. It shows an example of injected knowledge (a passage about a fictional Martian government), along with three types of probes designed to test different aspects of factual knowledge acquisition: memorization (exact recall), semantic generalization (paraphrase understanding), and compositional generalization (inferring new facts from multiple sentences). Each probe is a cloze task, where the bolded portion is the target span to be filled in by the model, assessing the depth of knowledge acquired.

In-depth insights#

Factual Knowledge Acquisition#

The study reveals that factual knowledge acquisition in LLMs during pretraining is a gradual process, not a sudden leap, achieved by accumulating small probability increases with each training step. Counterintuitively, more training data doesn’t significantly improve knowledge acquisition. Forgetting plays a crucial role, exhibiting a power-law relationship with training steps; larger batch sizes and deduplicated data enhance robustness. The findings suggest that LLMs acquire knowledge progressively, but this accumulation is offset by subsequent forgetting. This framework helps explain the observed limitations of LLMs in handling long-tail knowledge and underscores the importance of data deduplication in pretraining.

Training Dynamics#

The study’s analysis of training dynamics reveals crucial insights into how Large Language Models (LLMs) acquire and retain factual knowledge. Counterintuitively, increasing training data doesn’t significantly improve knowledge acquisition. Instead, knowledge is gained incrementally through repeated exposure to facts, but this is offset by subsequent forgetting. A power-law relationship exists between training steps and forgetting, suggesting a progressive increase in fact probability that’s diluted by later forgetting. Larger batch sizes enhance robustness against forgetting, indicating that efficient knowledge consolidation is impacted by the training regimen itself. These findings offer compelling explanations for phenomena like poor long-tail knowledge performance and the benefits of deduplicating training data, highlighting the importance of understanding the intricate dynamics governing factual knowledge acquisition in LLMs.

Forgetting Mechanisms#

Understanding forgetting mechanisms in large language models (LLMs) is crucial for improving their performance and reliability. Forgetting, in LLMs, isn’t simply the loss of information but rather a complex interplay of factors. The progressive increase in the probability of factual knowledge encountered during training is countered by subsequent forgetting, implying that simply increasing training data doesn’t guarantee better knowledge retention. This is further supported by the observation of a power-law relationship between training steps and forgetting, suggesting that knowledge fades more rapidly initially. Model size and batch size play significant roles, with larger models exhibiting greater robustness and larger batch sizes improving robustness against forgetting. The injection of duplicated training data, surprisingly, leads to faster forgetting, highlighting the importance of data deduplication in preventing information dilution. Investigating these dynamics provides valuable insights into how to design more effective and robust LLM training strategies, such as optimizing data curation and training hyperparameters.

LLM Scaling Limits#

LLM scaling limits represent a crucial area of research, exploring the boundaries of current large language model capabilities. While larger models generally exhibit improved performance, this trend isn’t limitless. Returns diminish at a certain scale, raising questions about the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of continued scaling. Resource constraints, including computational power and energy consumption, pose significant barriers to indefinite scaling. Furthermore, data limitations are a critical factor; simply increasing data volume may not proportionally improve performance, especially for rare or nuanced knowledge. There is a need to explore alternative approaches, such as architectural innovations and more efficient training methods, to overcome scaling limitations and unlock greater LLM potential. Understanding these limits is key to advancing the field responsibly and cost-effectively, rather than relying solely on brute-force scaling.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several avenues. Investigating the impact of different optimizer choices and learning rate schedules on factual knowledge acquisition and retention would be valuable. Further, a more in-depth analysis of the interaction between model size, training data diversity, and factual knowledge acquisition is needed. The current research suggests a non-linear relationship, but further investigation would refine our understanding. Exploring different knowledge injection strategies, moving beyond the simple approaches used here, and considering more sophisticated methods of data augmentation, could significantly impact results. Finally, extending this work to other LLMs and evaluating performance on tasks requiring more complex reasoning and composition of factual knowledge would contribute to more robust generalizations and better validation of the findings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

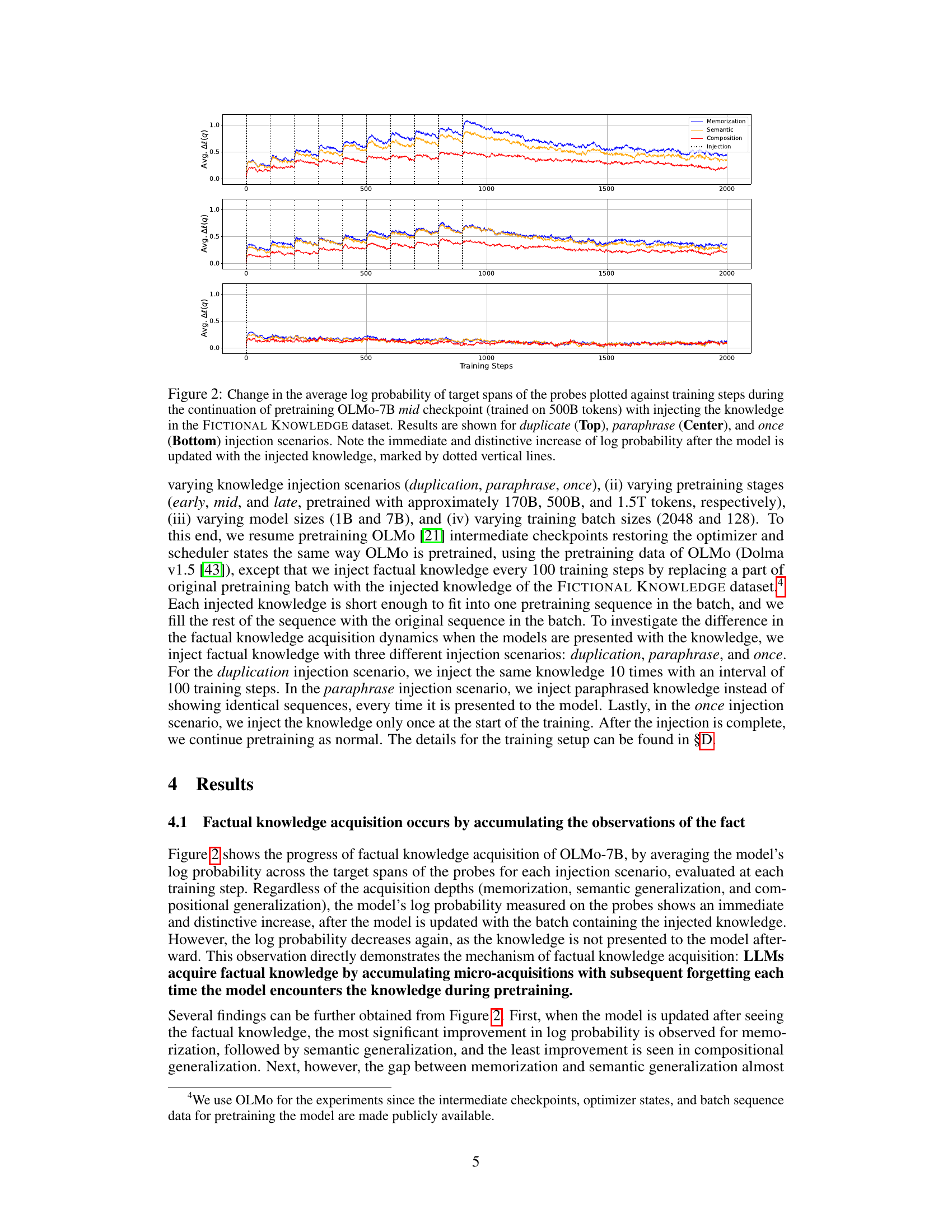

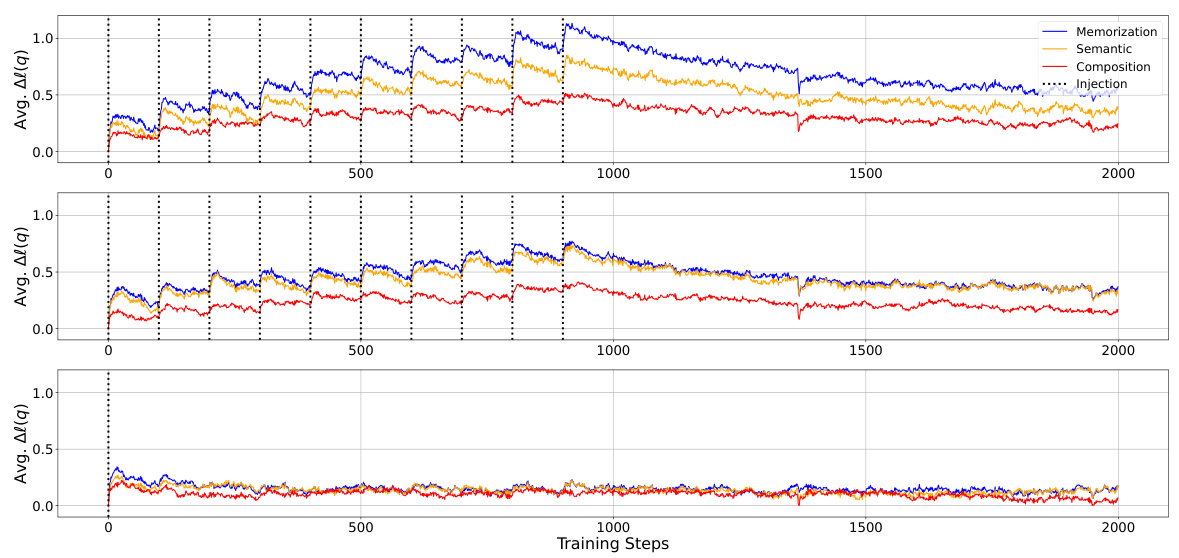

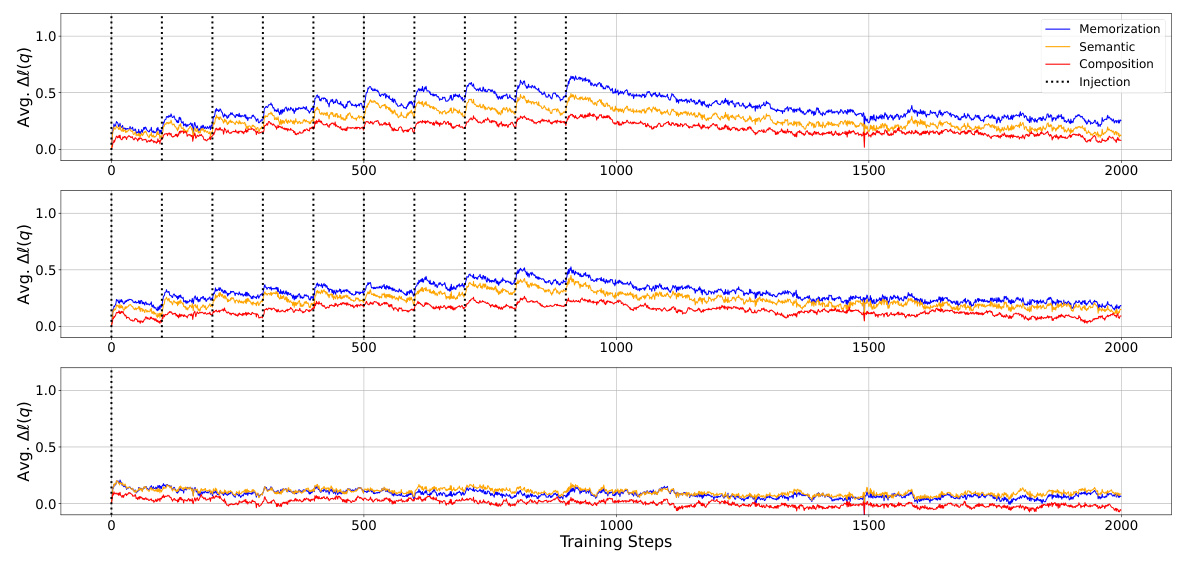

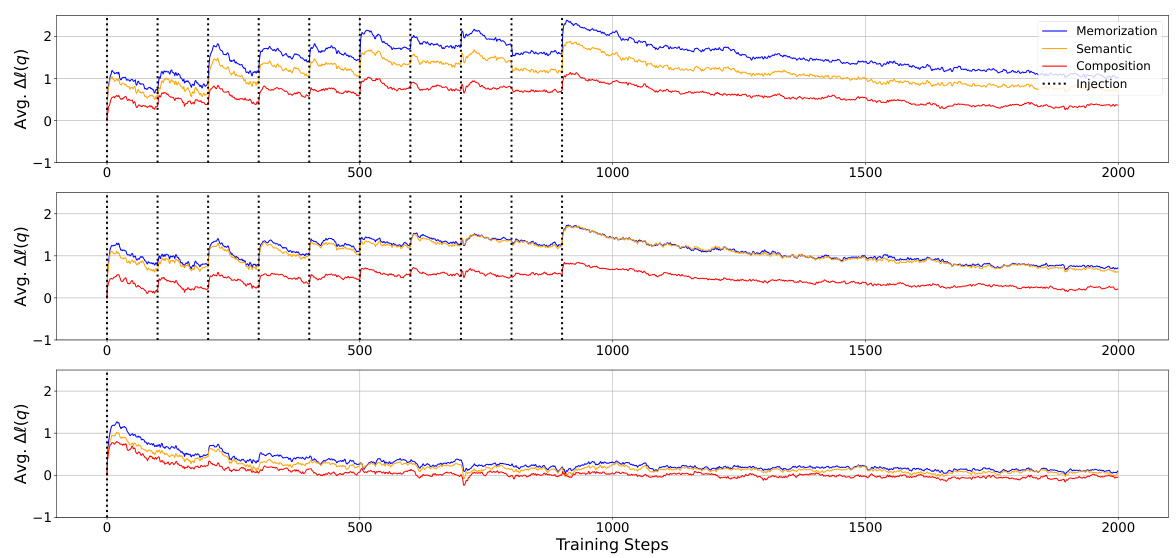

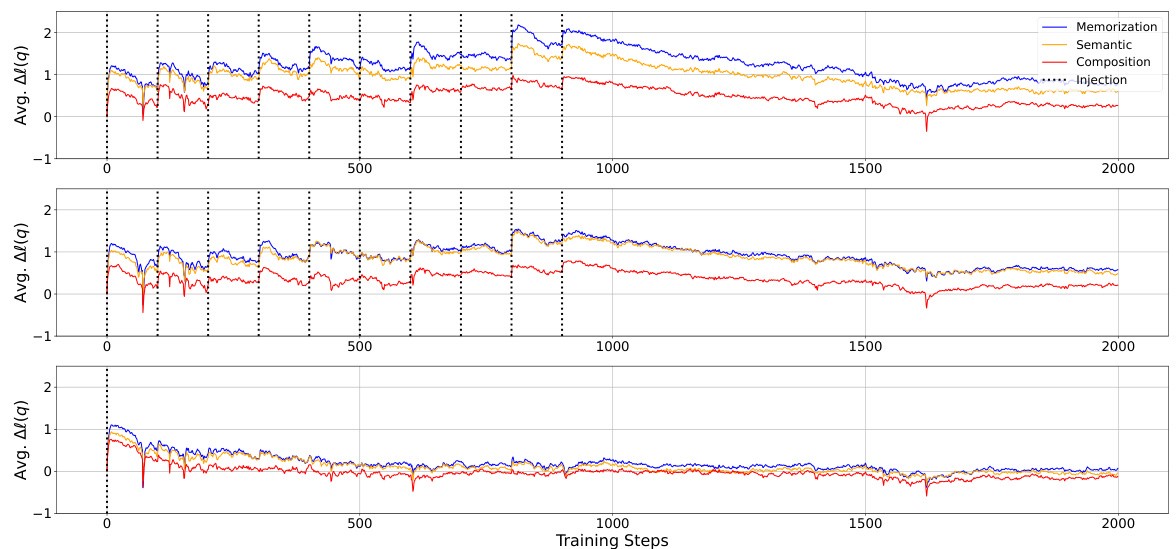

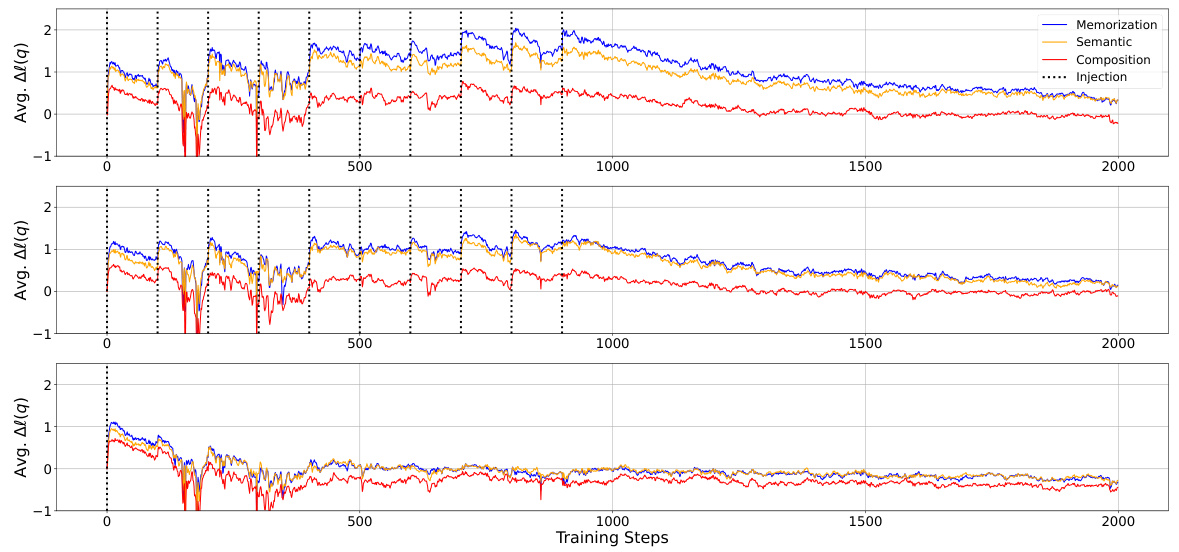

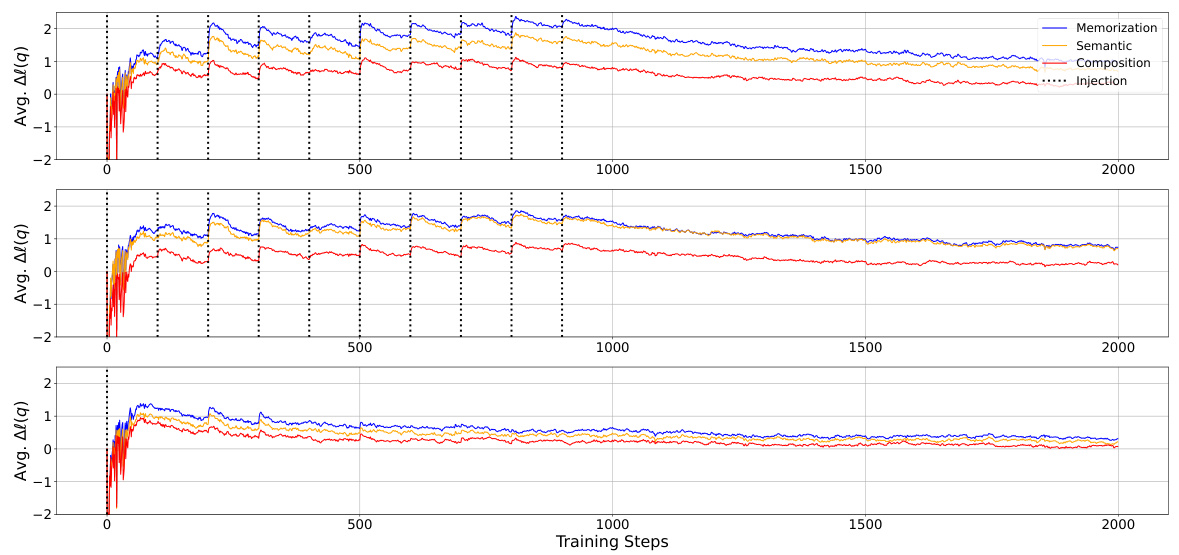

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of target spans across different probes (memorization, semantic, and compositional generalization) during continued pretraining of the OLMo-7B model. The model was initially pretrained on 500B tokens and then continued training with injected factual knowledge using three different scenarios: duplicate injection, paraphrase injection, and single injection. The x-axis shows training steps and the y-axis represents the average log probability. Dotted lines indicate the injection points. The results clearly showcase an immediate increase in log probability after each injection of new knowledge, followed by a decrease, highlighting the dynamics of factual knowledge acquisition and subsequent forgetting.

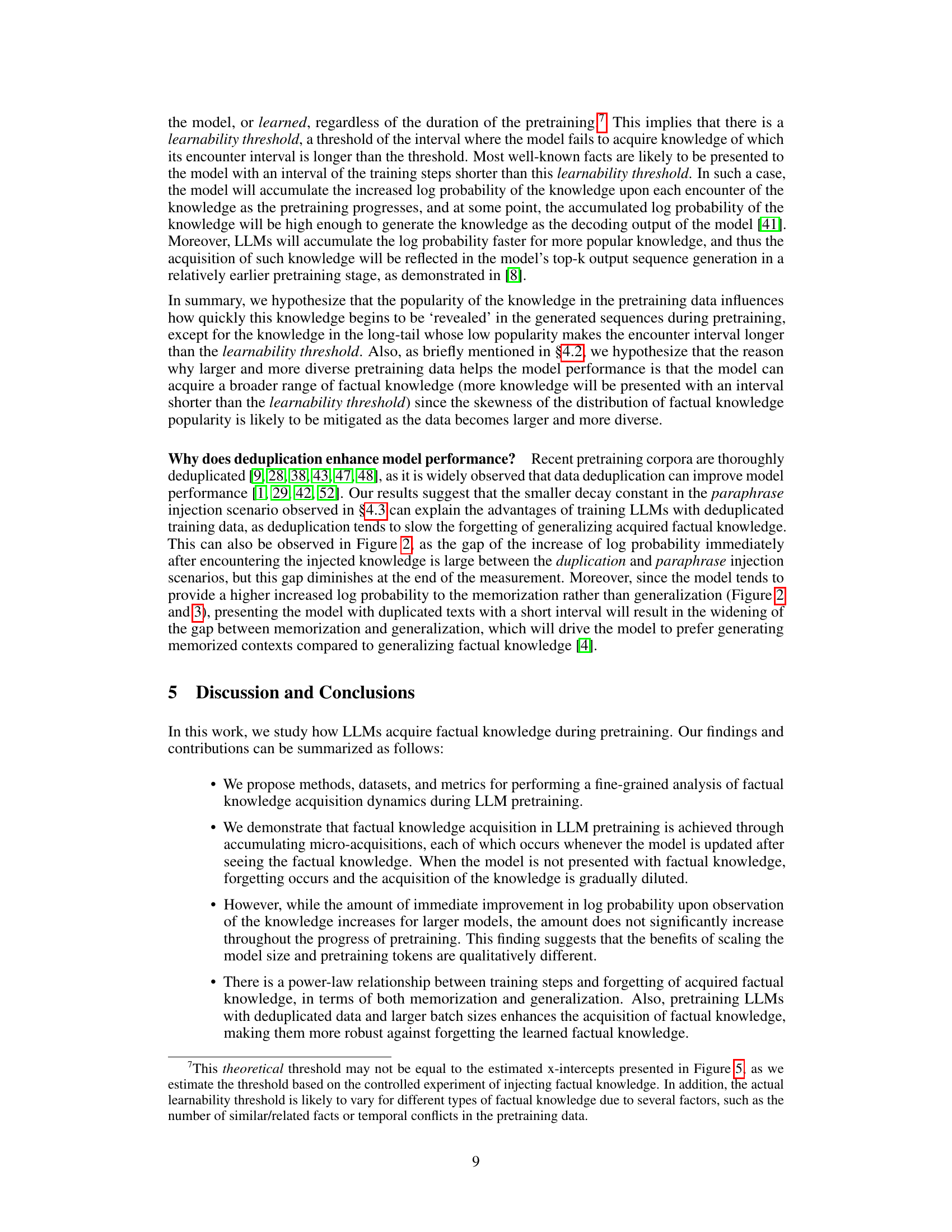

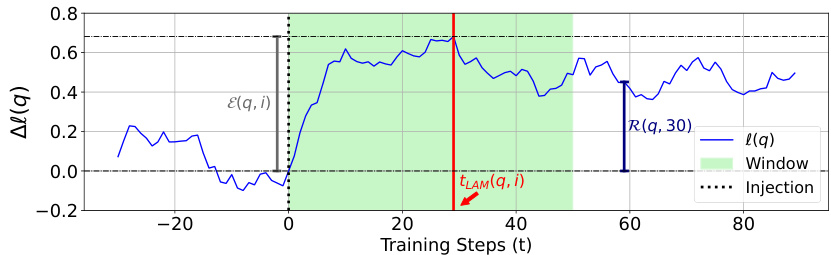

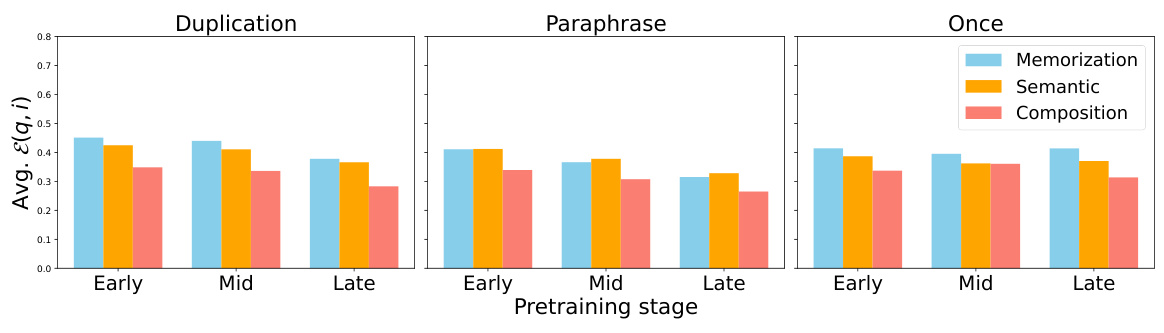

This figure shows the average effectivity (a measure of immediate improvement in the model’s log probability of factual knowledge after being trained with the injected knowledge) across different injection scenarios (duplication, paraphrase, once), acquisition depths (memorization, semantic, composition), pretraining stages (early, mid, late), and model sizes (1B, 7B). The left panel shows that effectivity does not improve with the increased number of pretraining tokens. The right panel shows that effectivity improves significantly as model size increases.

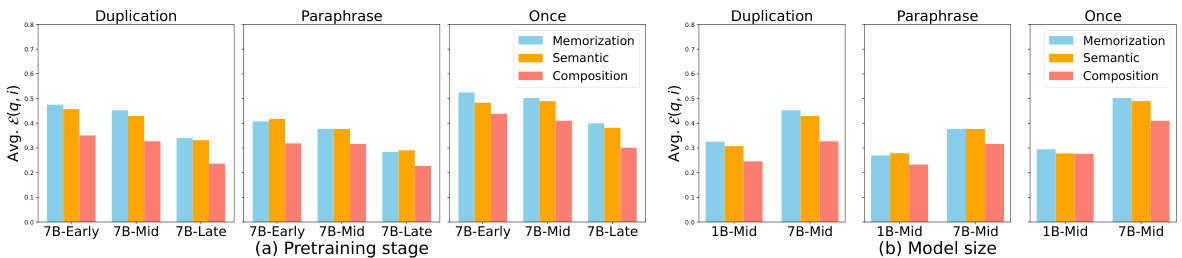

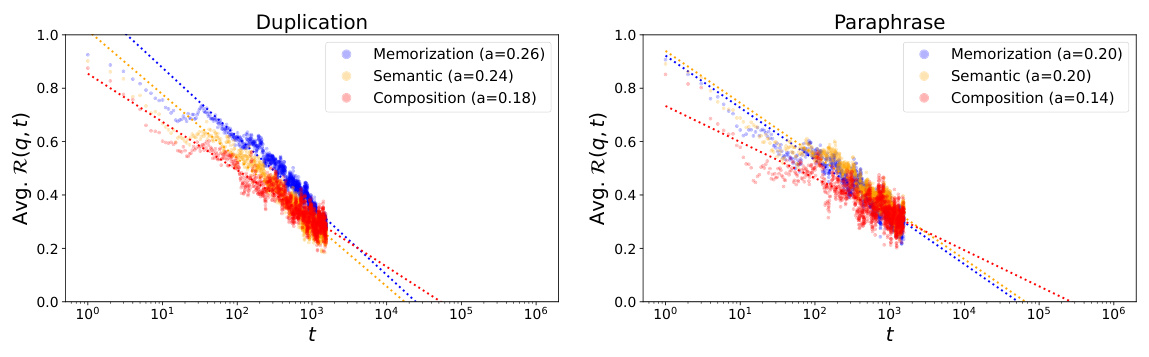

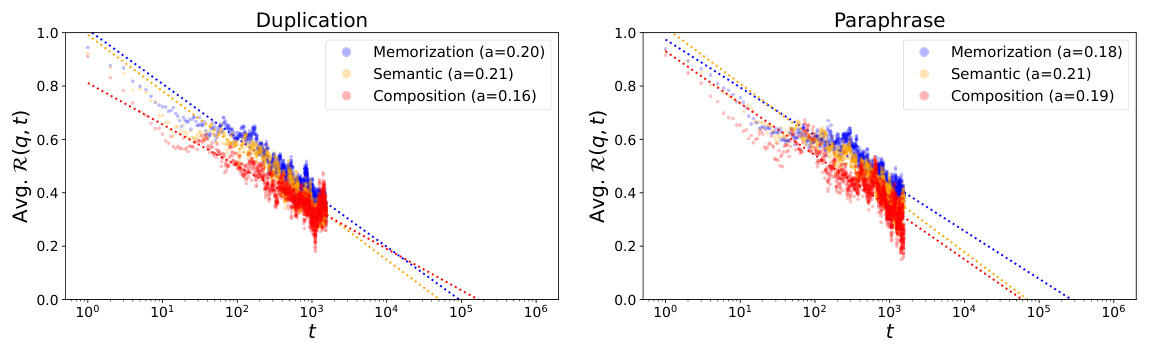

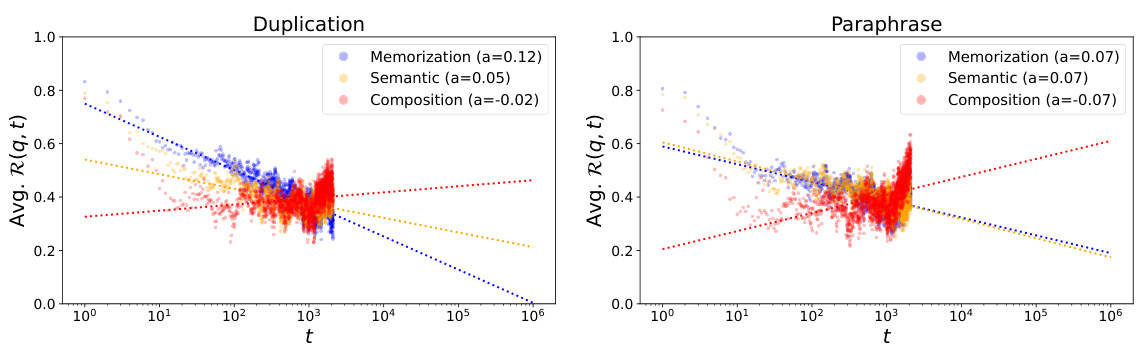

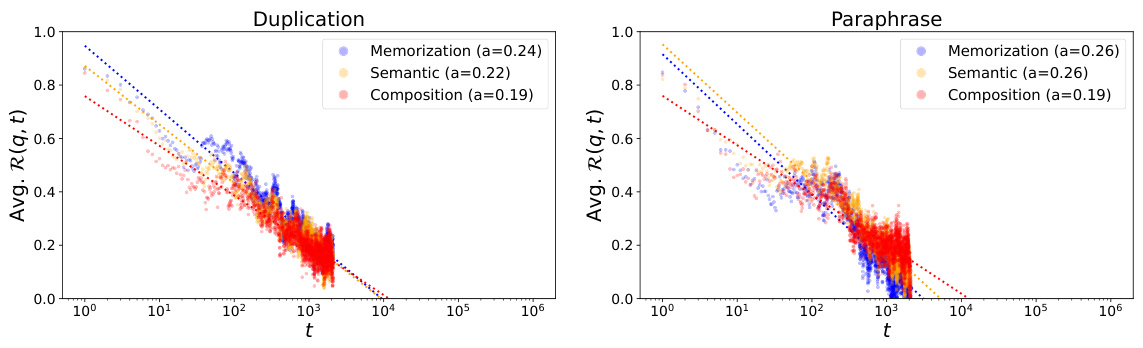

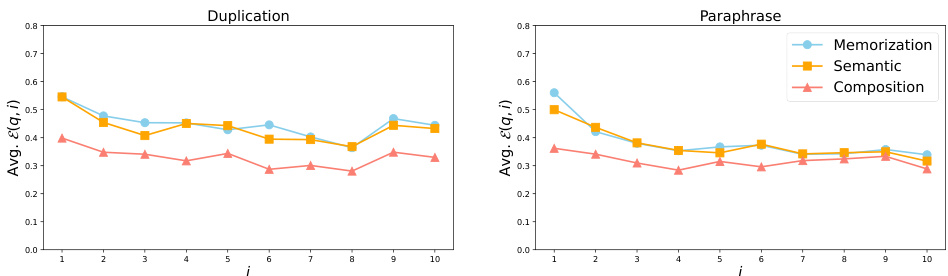

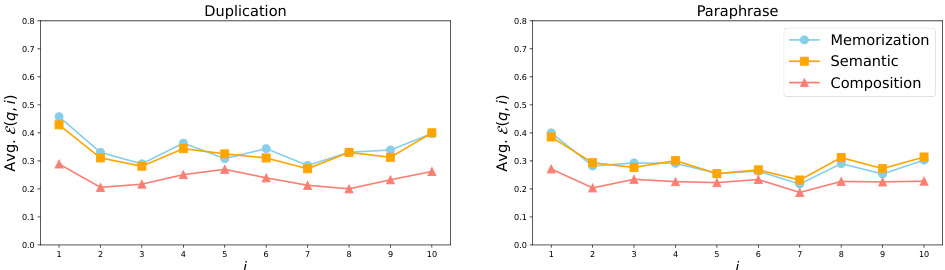

This figure displays the trend of retainability against training steps after the model’s log probability of factual knowledge reaches its peak (local acquisition maxima). It demonstrates the rate at which the model ‘forgets’ the acquired factual knowledge over time, separately showing the results for both the duplication and paraphrase injection scenarios. The x-axis uses a logarithmic scale to better visualize the power-law relationship. The lines represent the average retainability across multiple probes, illustrating how quickly the model loses the improvement in log probability of factual knowledge.

This figure displays the trend of retainability against training steps past the point where the log probability of factual knowledge reaches its maximum (local acquisition maxima). It shows the rate at which acquired factual knowledge is forgotten (or retained) over time. Separate plots illustrate the results using duplicated and paraphrased training data, highlighting differences in knowledge retention. The x-axis is logarithmic, better showcasing the power law relationship between training steps and forgetting observed in the paper.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of factual knowledge over training steps. Three different injection scenarios are shown: duplicate (injecting the same knowledge multiple times), paraphrase (injecting paraphrased versions of the knowledge), and once (injecting the knowledge only once). The graph shows a clear, immediate increase in log probability after injecting the knowledge, followed by a gradual decline. This illustrates the process of factual knowledge acquisition in LLMs, where knowledge is acquired incrementally but also gradually lost over time. The different injection strategies highlight how the frequency and form of knowledge presentation affect both immediate acquisition and long-term retention.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of target spans of probes over training steps. The experiment involved continuing the pretraining of the OLMo-7B model (mid-checkpoint, trained on 500 billion tokens) while injecting knowledge from the FICTIONAL KNOWLEDGE dataset. Three injection scenarios are shown: duplicate (injecting the same knowledge multiple times), paraphrase (injecting paraphrased versions of the knowledge), and once (injecting the knowledge only once). The figure clearly shows an immediate and significant increase in log probability immediately after the injection of knowledge in all three scenarios, followed by a gradual decrease, indicating the phenomenon of knowledge acquisition followed by forgetting.

This figure displays the change in average log probability of target spans of probes across three different knowledge injection scenarios (duplicate, paraphrase, once) during the continued pretraining of the OLMo-7B model. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the average log probability. The figure shows that across memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization, there is an immediate increase in log probability immediately after injecting the knowledge (indicated by dotted lines), followed by a subsequent decrease. The degree of increase and the rate of the subsequent decrease varies depending on the injection scenario.

This figure visualizes the change in the average log probability of target spans in probes (measuring memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization) throughout the continued pretraining of the OLMo-7B model. The model’s pretraining was continued after injecting fictional knowledge into the training data using three different injection methods: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. Each method’s results are shown separately. The figure highlights a sharp increase in the log probability immediately after knowledge injection, followed by a decrease as training continues. This illustrates the model’s acquisition of factual knowledge through accumulating small increases in probability, which are subsequently diluted by forgetting.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of factual knowledge over training steps for three different knowledge injection scenarios: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. The x-axis shows the training steps, and the y-axis shows the average log probability. Three separate subplots are shown, one for each injection scenario (duplicate, paraphrase, and once). The plots show that there is a spike in the log probability immediately following the injection of the knowledge. After the injection, the log probability decreases gradually. The figure demonstrates that LLMs acquire factual knowledge by accumulating small increases in probability at each step, but this improvement is often diminished by subsequent forgetting.

This figure shows the average effectivity—the immediate improvement in the model’s log probability of factual knowledge after being trained with the injected knowledge—across various probes and each time of injection, measured for different injection scenarios (duplication, paraphrase, once) and acquisition depths (memorization, semantic, composition). The left panel shows that effectivity does not improve as the model is trained with more tokens (i.e., across different pretraining stages), while the right panel shows a clear improvement in effectivity as the model size scales from 1B to 7B parameters.

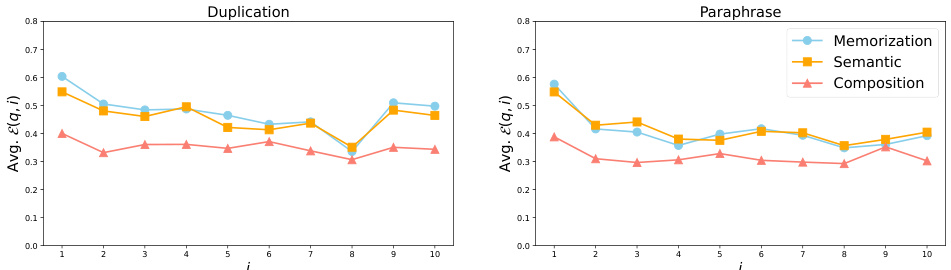

This figure displays the average retainability (the fraction of improvement in log probability retained by the model after t steps, relative to the local acquisition maxima of the last knowledge update) against training steps past the local acquisition maxima. The x-axis is in log scale. The left panel shows the results for the duplication injection scenario, while the right panel shows the results for the paraphrase injection scenario. Different colors and line styles represent different acquisition depths (memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization). The decay constants (α) for each curve are indicated in the legend. This figure visually demonstrates the power-law relationship between training steps and the forgetting of acquired factual knowledge, and shows how the forgetting rate differs between the two injection scenarios and across different acquisition depths.

This figure displays the average retainability of factual knowledge over time after the model has reached its peak acquisition point. Retainability is the fraction of log probability improvement retained compared to the maximum achieved. The x-axis represents training steps in a logarithmic scale. The two subfigures show the results for two different scenarios: knowledge injection by duplication and paraphrase. Each subfigure shows how the retainability decays over training steps for three levels of knowledge acquisition: Memorization, Semantic Generalization, and Compositional Generalization.

This figure shows the trend of retainability against the training steps past the local acquisition maxima, measured with the OLMo-7B mid checkpoint. Retainability quantifies the fraction of improvement in log probability retained by the model after t steps, relative to the local acquisition maxima of the last knowledge update. The x-axis represents training steps on a logarithmic scale, and there are separate plots for the ‘duplication’ and ‘paraphrase’ injection scenarios. The lines on the plot represent the overall trend of forgetting. The figure demonstrates that the trend of forgetting has a power law relationship with training steps in both memorization and generalization.

This figure displays the average retainability of factual knowledge over training steps after the point of maximum acquisition for each probe. Retainability is the fraction of the initial knowledge improvement retained at a given point. The x-axis shows the training steps, plotted on a logarithmic scale. The two subfigures show the results for the ‘duplication’ (left) and ‘paraphrase’ (right) injection scenarios, respectively. Each scenario shows the retention for memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization using different colored lines. The lines also illustrate the power-law relationship between training steps and forgetting of factual knowledge described in the paper.

This figure displays the average retainability of factual knowledge over time after its initial acquisition. Retainability, a measure of how well the model retains the knowledge, is plotted against training steps on a logarithmic scale. The left panel shows data for the ‘duplication’ injection scenario (where the knowledge was repeatedly injected during training), while the right panel shows data for the ‘paraphrase’ scenario (where paraphrases of the knowledge were introduced). The different colored lines represent different levels of knowledge acquisition: Memorization (blue), Semantic Generalization (orange), and Compositional Generalization (red). The figure shows that knowledge retention decreases over time, following a power-law relationship. The rate of forgetting varies depending on the acquisition depth (memorization vs. generalization) and the knowledge injection scenario (duplication vs. paraphrase).

This figure visualizes the average effectivity (a metric quantifying the immediate improvement in the model’s log probability of factual knowledge) for different injection scenarios (duplication, paraphrase, once), acquisition depths (memorization, semantic, composition), and model sizes (1B, 7B). The left panel shows that effectivity does not increase as the model is trained with more tokens (pretraining stages: early, mid, late), suggesting that simply training on more data doesn’t improve the model’s ability to learn new facts. In contrast, the right panel clearly shows a significant increase in effectivity as the model size scales from 1B to 7B, indicating that larger models are better at immediately integrating new factual knowledge.

This figure displays the change in average log probability of target spans of probes across different knowledge acquisition depths (memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization) during the continuation of pretraining an OLMo-7B model. The model was pretrained on 500B tokens before injecting additional knowledge from the FICTIONAL KNOWLEDGE dataset. Three injection scenarios are compared: duplicate, paraphrase, and once (each shown in separate panels). The plots illustrate how the log probability changes for each scenario as training progresses, highlighting a rapid increase immediately after the knowledge injection before a gradual decline due to forgetting.

This figure displays the changes in the average log probability of factual knowledge over training steps for three different knowledge injection scenarios: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the average log probability. Each subplot (top, middle, bottom) shows the results for a different injection method. Dotted lines indicate the points at which new knowledge was injected. The figure highlights the immediate increase in log probability after injection, followed by a gradual decrease. This demonstrates the model’s ability to learn the new factual knowledge but also its tendency to forget it over time.

This figure shows the change in the average log probability of the target spans of probes over training steps. Three different injection scenarios are presented: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. Each scenario is shown in a separate subplot, with memorization, semantic, and compositional generalization shown as different lines within each subplot. The key observation is the immediate increase in log probability after the injected knowledge is introduced, followed by a gradual decrease, illustrating the dynamics of factual knowledge acquisition and forgetting during pretraining. The dotted vertical lines indicate the points of knowledge injection.

This figure shows the average effectivity for different model sizes and training stages. Effectivity measures the immediate improvement in the model’s ability to predict factual knowledge after being trained with that knowledge. The left panel shows that effectivity does not improve significantly as the amount of training data increases. However, the right panel indicates a clear increase in effectivity as the model size increases from 1B to 7B parameters, suggesting a qualitative difference in how factual knowledge is acquired between the two model sizes.

This figure displays the average retainability of factual knowledge over time after the model’s log probability reaches its peak (local acquisition maxima). Retainability is the fraction of the improvement in log probability that remains after a certain number of training steps. The x-axis shows the training steps after the peak on a logarithmic scale. The left panel shows results from an experiment where duplicate knowledge was injected, and the right panel shows results from an experiment where paraphrased knowledge was injected. The different colored lines represent different levels of knowledge acquisition (memorization, semantic generalization, compositional generalization). The figure demonstrates that factual knowledge is forgotten over time (retainability decreases), and the rate of forgetting is affected by the way knowledge is injected during training.

This figure displays the average retainability of factual knowledge in LLMs over time after the knowledge is first introduced (local acquisition maxima). Retainability is the fraction of improvement in log probability retained by the model after t steps, relative to the local acquisition maxima. The x-axis represents training steps on a logarithmic scale. The two panels show the results for different knowledge injection scenarios. The left panel (‘duplication’) shows the case where the same knowledge is presented repeatedly during training, while the right panel (‘paraphrase’) shows the case where different versions of the same knowledge are presented. The different colored lines represent different levels of knowledge acquisition (memorization, semantic generalization, composition generalization). The dashed lines represent a power-law model fit to the data, demonstrating the power-law relationship between training steps and forgetting.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of target spans in probes over training steps for three different knowledge injection scenarios: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. The experiment uses a pre-trained OLMo-7B model and injects new factual knowledge at various points during continued training. The plots show an immediate and significant increase in log probability immediately after knowledge injection for all three scenarios and across different types of probes (memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization). The subsequent decrease demonstrates the phenomenon of forgetting after knowledge is no longer present in the training data. The figure shows that the effect is more pronounced for memorization than for generalization.

This figure displays the changes in the average log probability of target spans of probes over training steps. Three different knowledge injection scenarios are shown: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. Each scenario is further broken down by acquisition depth (memorization, semantic, and composition). The figure demonstrates the immediate increase in log probability upon injecting knowledge, followed by a decrease, illustrating the accumulation of knowledge with subsequent forgetting.

This figure shows the change in the average log probability of the target spans of probes across three different knowledge injection scenarios (duplicate, paraphrase, once). The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the average log probability. The figure demonstrates that injecting new factual knowledge into the model during pretraining causes an immediate and significant increase in the log probability, followed by a gradual decrease (forgetting) as training continues. The three injection scenarios highlight the dynamics of knowledge acquisition and forgetting; the duplicate injection shows the largest initial improvement but also the fastest forgetting. The once injection shows a smaller initial increase and slower forgetting.

This figure displays the change in average log probability of target spans of probes against training steps. Three different injection scenarios are used: duplicate, paraphrase, and once. The graph shows an immediate and significant increase in log probability after the model is updated with the injected knowledge, regardless of the acquisition depth. However, the log probability decreases as training continues without further presentation of the injected knowledge, showcasing the model’s acquisition and subsequent forgetting of factual knowledge.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of factual knowledge across various probes, plotted against training steps. The experiment involved continuing the pretraining of an OLMo-7B model (already trained on 500 billion tokens) by injecting new factual knowledge at regular intervals. The figure shows results for three different injection scenarios: duplicate (injecting the same knowledge multiple times), paraphrase (injecting paraphrases of the same knowledge), and once (injecting each piece of knowledge only once). The dotted vertical lines highlight the immediate increase in log probability after each knowledge injection, illustrating the model’s acquisition of the new factual knowledge. The subsequent decline in log probability showcases the forgetting or dilution of the acquired knowledge over further training steps. The graph visually demonstrates the dynamics of factual knowledge acquisition and forgetting during the continued pretraining process.

This figure displays the change in the average log probability of target spans of probes over training steps. Three different knowledge injection scenarios are shown: duplicate injection (top), paraphrase injection (middle), and once injection (bottom). Each scenario shows the average log probability for three acquisition depths: memorization, semantic generalization, and compositional generalization. Dotted vertical lines mark when injected knowledge was added to the training data. The graph highlights that factual knowledge acquisition involves a rapid initial increase in log probability following injection, followed by a subsequent decrease (forgetting). The effects of different injection scenarios on knowledge acquisition and retention are evident.

More on tables

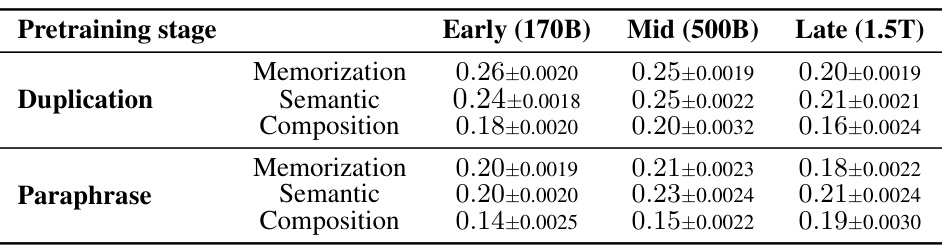

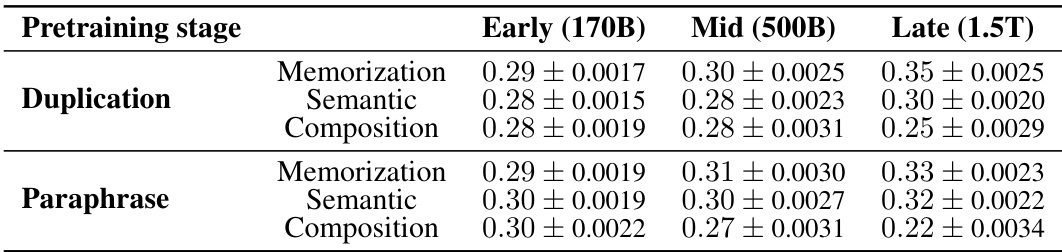

This table shows the decay constant (α) for the retainability metric (R(p, t)). Retainability measures how quickly the model forgets factual knowledge acquired after a local acquisition maximum. A higher decay constant indicates faster forgetting. The table breaks down the decay constant by pretraining stage (Early, Mid, Late), acquisition depth (Memorization, Semantic, Composition), and injection scenario (Duplication, Paraphrase).

This table exemplifies the FICTIONAL KNOWLEDGE dataset used in the paper. It demonstrates three types of probes used to assess different levels of factual knowledge acquisition by LLMs: memorization (identical to a sentence in the injected knowledge), semantic generalization (paraphrased version of the memorization probe with the same target span), and compositional generalization (evaluation of the model’s ability to combine knowledge from multiple sentences in the injected knowledge). Each probe type has a bolded target span indicating the part evaluated for knowledge acquisition.

This table exemplifies the structure of the FICTIONAL KNOWLEDGE dataset used in the paper’s experiments. It shows how factual knowledge is injected, and the three levels of probes designed to test different aspects of knowledge acquisition: memorization (exact recall), semantic generalization (paraphrase understanding), and compositional generalization (inferencing from multiple sentences). Each probe includes a bolded target span representing the factual information being tested.

This table shows the initial learning rates used for different sized models (OLMo-1B and OLMo-7B) at various stages of pretraining. The pretraining stages are categorized as Early, Mid, and Late, corresponding to specific token counts for each model size. The table provides context for understanding how initial learning rates were adjusted across different training scenarios.

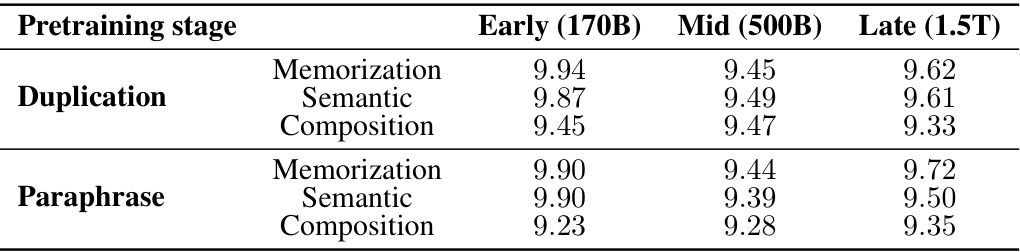

This table shows the anticipated x-intercepts of the retainability (R(p,t)) function. The x-intercept represents the point where the improvement in log probability of factual knowledge is completely lost after the model is trained with the injected knowledge. The table presents these x-intercepts for OLMo-7B model at three different pretraining stages (Early, Middle, Late) for different acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, Composition) and injection scenarios (Duplication, Paraphrase). The units are in log(Tokens).

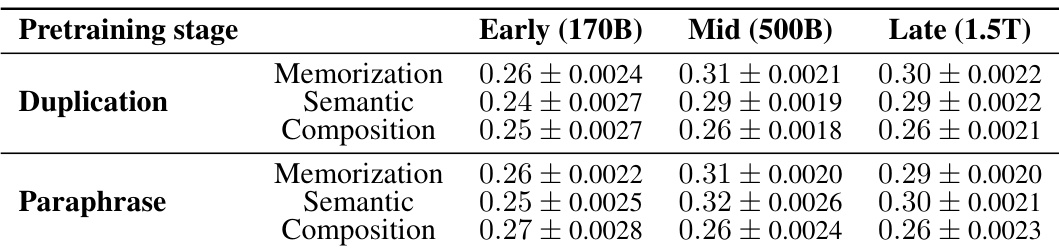

This table presents the decay constant of average retainability for OLMo-1B model at three different pretraining stages (Early, Mid, and Late) across different acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, and Composition) under two injection scenarios (Duplication and Paraphrase). The decay constant indicates how fast the model forgets the acquired factual knowledge. The Early (168B) checkpoint data is missing due to poor linear fitting, likely resulting from unstable model dynamics.

This table shows the anticipated x-intercepts of the retainability (R(p, t)) for OLMo-1B model at three different pretraining stages (Early, Mid, Late), three different acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, Composition), and two different injection scenarios (Duplication, Paraphrase). The x-intercept represents the training steps (in log scale of tokens) at which the improvement of log probability induced by the injected knowledge at the local acquisition maxima completely vanishes. Note that the data for Early (168B) checkpoint is omitted due to poor linear fitting.

This table shows the decay constant (α) of the retainability (R(p,t)) values which represent how quickly the model forgets the acquired factual knowledge in terms of fraction. It shows how fast the model loses the improvement of log probability. The table presents the decay constant for three different pretraining stages (Early (170B), Mid (500B), and Late (1.5T)), three different acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, and Composition), and two different injection scenarios (Duplication and Paraphrase). A larger decay constant implies faster forgetting.

This table presents the decay constant (a) of retainability, representing the rate at which the model loses the improvement in log probability of factual knowledge over training steps. The data is broken down by three different pretraining stages (Early, Mid, Late), three acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, Composition), and two injection scenarios (Duplication, Paraphrase). A higher decay constant indicates faster forgetting.

This table presents the anticipated x-intercepts of the retainability metric (R(q, t)) for the OLMo-7B model across three different pretraining stages (Early, Mid, Late), three different acquisition depths (Memorization, Semantic, Composition), and two injection scenarios (Duplication, Paraphrase). The x-intercept represents the point at which the model completely forgets the acquired factual knowledge. The units of measurement are log(Tokens), indicating the number of tokens processed after the local acquisition maxima before complete forgetting occurs. Values are shown with standard deviation.

Full paper#