↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating heterogeneous treatment effects (HTE) is crucial for personalized interventions. Existing methods like the Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE) and Conditional Quantile Treatment Effect (CQTE) have limitations. CATE focuses only on average effects, overlooking distributional differences which can lead to biased estimations, while CQTE estimation is challenging and depends heavily on the smoothness of individual quantiles. These factors limit the applicability and accuracy of both methods.

This paper proposes a new estimand, the Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC), to address these shortcomings. The CQC compares equivalent quantiles of the treatment and control groups, offering more comprehensive information than CATE while avoiding the complexities of CQTE. A novel doubly robust estimation procedure is developed, demonstrating improved accuracy in numerical simulations, which is validated by a theoretical analysis. The CQC’s intuitive interpretation and robust estimation make it a promising tool for HTE analysis.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel estimand, the Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC), for analyzing heterogeneous treatment effects. The CQC offers a valuable alternative to existing methods by combining the strengths of CATE and CQTE while mitigating their weaknesses. This opens new avenues for HTE research, particularly in scenarios where treatment effects are not simply location shifts, and provides improved estimation accuracy in relevant cases. The theoretical framework, including double robustness properties and finite sample bounds, strengthens the methodological rigor of this approach. The use of the pseudo-outcome framework also facilitates efficient estimation.

Visual Insights#

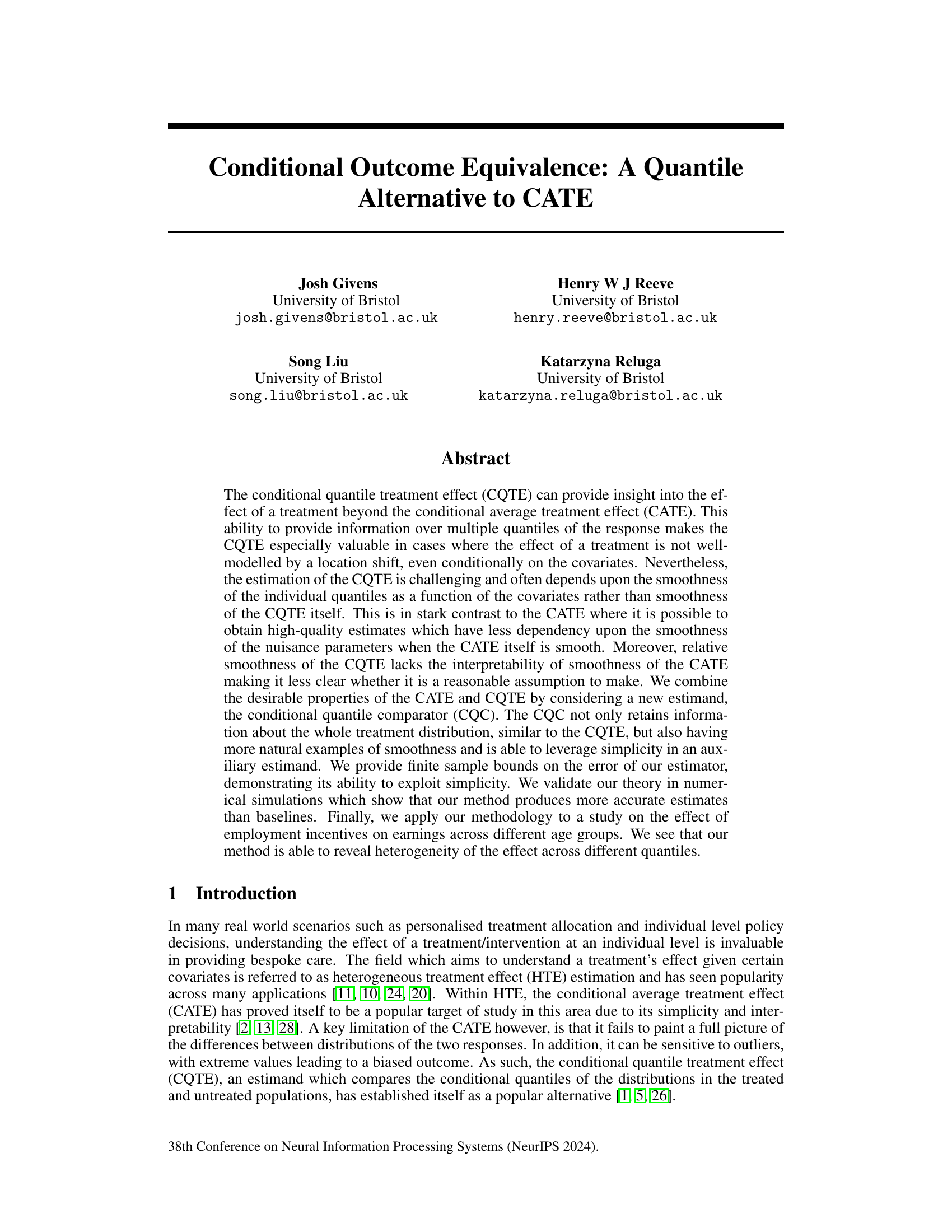

This figure visualizes the Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC). The left panel shows a 3D surface plot of the CQC, where the x-axis represents covariates, the y-axis represents the untreated response, and the z-axis represents the treated response at the same quantile. The right panel displays conditional quantile-quantile (QQ) plots for different covariate values (x=0, 0.5, 1), illustrating the relationship between the untreated and treated response distributions at each quantile level for a given covariate setting. The colored lines on the left panel correspond to the slices represented in the QQ plots on the right.

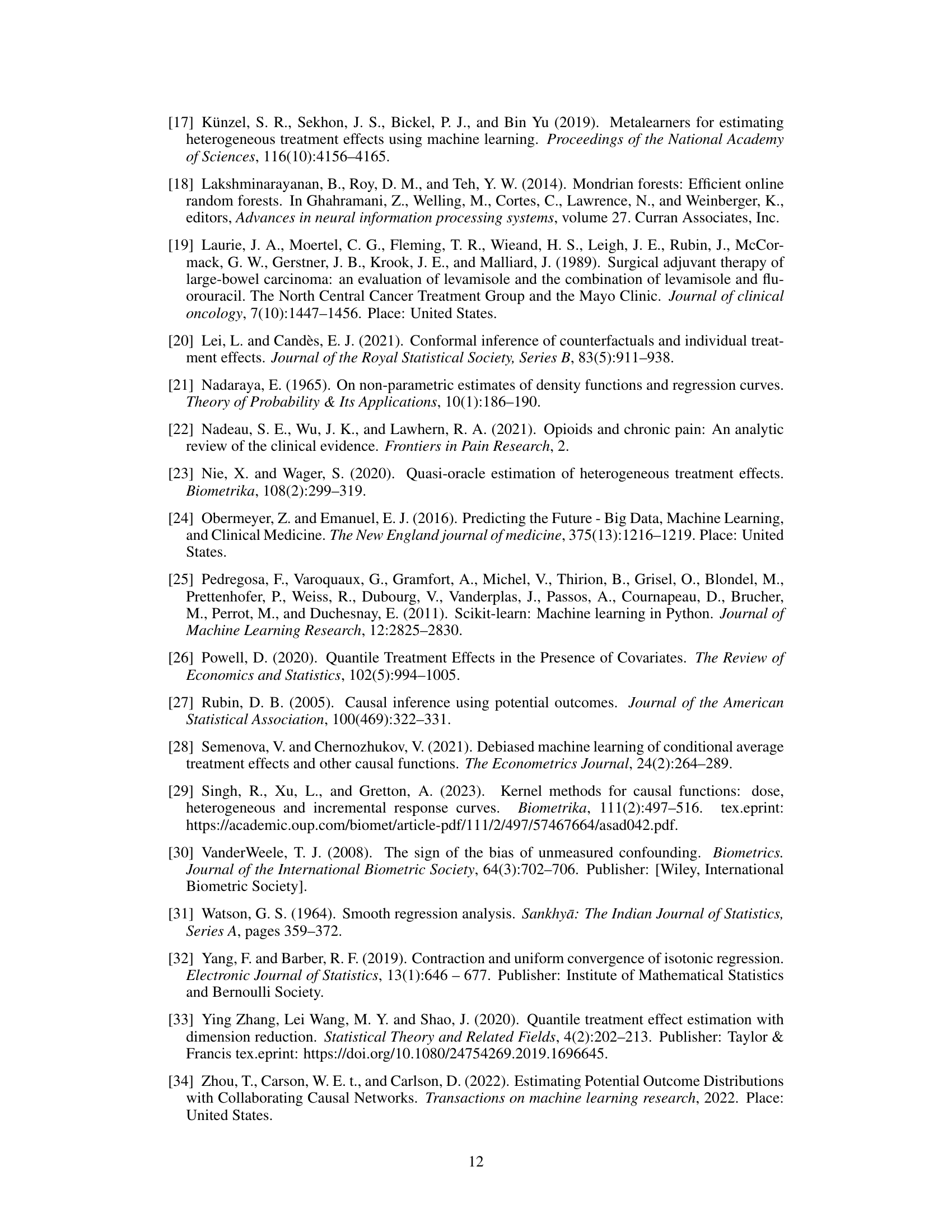

This table lists all notations used in the paper with their corresponding definitions and descriptions. It covers variables, functions (like conditional CDFs, quantiles, treatment effects), estimators, and other mathematical symbols.

In-depth insights#

Quantile Treatment#

Quantile treatment effects offer a richer understanding of treatment impact than traditional average treatment effects. Instead of focusing solely on the average change, quantile regression examines how treatment affects different points of the outcome distribution. This is particularly valuable when the treatment’s effect isn’t uniform across the outcome range, which is often the case in real-world scenarios. By analyzing quantile-specific treatment effects, researchers can uncover important heterogeneity. For instance, a treatment might significantly boost the highest earners but have a negligible effect on the lowest. Understanding this heterogeneity is crucial for designing targeted interventions and evaluating their true effectiveness. A limitation is the complexity in estimation, particularly if the quantile functions themselves lack smoothness. Careful consideration of these nuances is necessary for reliable quantile treatment effect estimation and meaningful conclusions.

CQC Estimation#

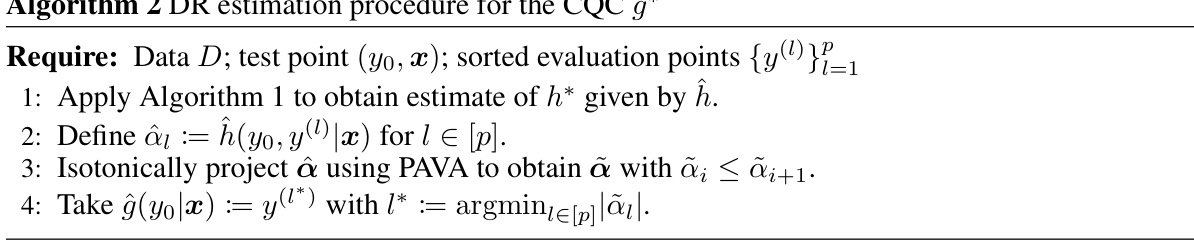

The CQC estimation procedure, a crucial contribution of this research paper, centers on estimating the conditional quantile comparator (CQC), a novel estimand that offers insights into the treatment effect’s impact across various quantiles of the outcome distribution. The approach cleverly leverages existing CATE estimation techniques, specifically pseudo-outcomes, to tackle the CQC estimation. This is achieved by formulating the CQC estimation as a CATE problem, allowing for the utilization of robust and efficient CATE estimation methods like the doubly robust (DR) estimator. This clever re-framing is a key strength of the proposed method, as it permits the exploitation of existing theoretical results and estimation procedures, circumventing challenges directly associated with quantile regression estimation. The paper provides theoretical guarantees on the estimator’s accuracy and validates these empirically through simulations. Finite sample bounds are established, highlighting the robustness of the method even when nuisance parameters (propensity score and conditional distributions) are not perfectly estimated. The overall approach is computationally feasible, making the CQC estimation a practical tool for analyzing heterogeneous treatment effects.

Double Robustness#

Double robustness, in the context of causal inference, is a crucial property of certain estimators that ensures reliable estimation even when one or more of the constituent components is misspecified or poorly estimated. This resilience stems from the clever combination of multiple estimators, often leveraging both outcome and propensity score models. If either model is accurate, a double robust estimator provides consistent results, reducing the risk of bias significantly. This robustness is particularly important when dealing with complex real-world scenarios where model assumptions are difficult to verify or guarantee. For example, in analyzing treatment effects, double robustness can handle situations with imperfect modeling of treatment assignment (propensity score) or treatment response. However, double robustness is not a free pass and comes with important caveats: the performance hinges on the appropriate combination of estimators and the specific nature of the model misspecifications. It’s vital to choose the right estimators and carefully assess the potential biases that might still persist under specific scenarios. Furthermore, double robustness may not guarantee good performance in all situations, particularly in high dimensional settings or with limited sample sizes. Thus, while a powerful tool, a thoughtful approach and validation are necessary when implementing and relying on doubly robust estimators.

Smoothness & CQC#

The concept of smoothness is crucial in the context of the Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC) because it directly impacts the accuracy and efficiency of estimation. Smoothness of the CQC, unlike the individual quantile functions, is directly linked to the ease of estimation. A smooth CQC allows for the application of simpler and more efficient estimation techniques, leading to more accurate results, especially in cases where individual quantile functions are rough or non-smooth. The paper emphasizes this key advantage of CQC over CQTE, highlighting that estimation of individual quantiles (which are often non-smooth) is more challenging than estimating the CQC itself, even if the underlying CQC is smooth. This difference becomes critical when dealing with finite samples, as simpler smoothness assumptions improve finite sample bounds and estimation accuracy. The authors provide a clear example demonstrating this property: the CQC may be smoother than its constituent nuisance parameters. This allows leveraging existing robust CATE estimation procedures, making the CQC estimation more accurate and reliable than traditional CQTE methods. Therefore, the smoothness of the CQC plays a pivotal role in establishing its practical usefulness, providing theoretical guarantees and enhanced empirical performance.

Future Directions#

The research paper’s ‘Future Directions’ section could explore extending the Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC) to more complex scenarios. This includes investigating its application with time-series data, incorporating non-parametric approaches, or handling missing data more robustly. A key area for advancement is exploring the theoretical properties of the CQC estimator further, such as deriving sharper finite-sample bounds or relaxing assumptions on the smoothness of nuisance functions. Another promising avenue is developing more efficient algorithms for estimating the CQC, particularly those that can handle high-dimensional data or complex treatment effects. The paper could also benefit from a deeper exploration of the CQC’s relative advantages and disadvantages compared to the CATE and CQTE, offering more comprehensive guidelines on when it is the most suitable estimand. Finally, investigating the practical implications of the CQC in various applications, including personalized medicine and policy decisions, would enhance its impact and demonstrate its broader utility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

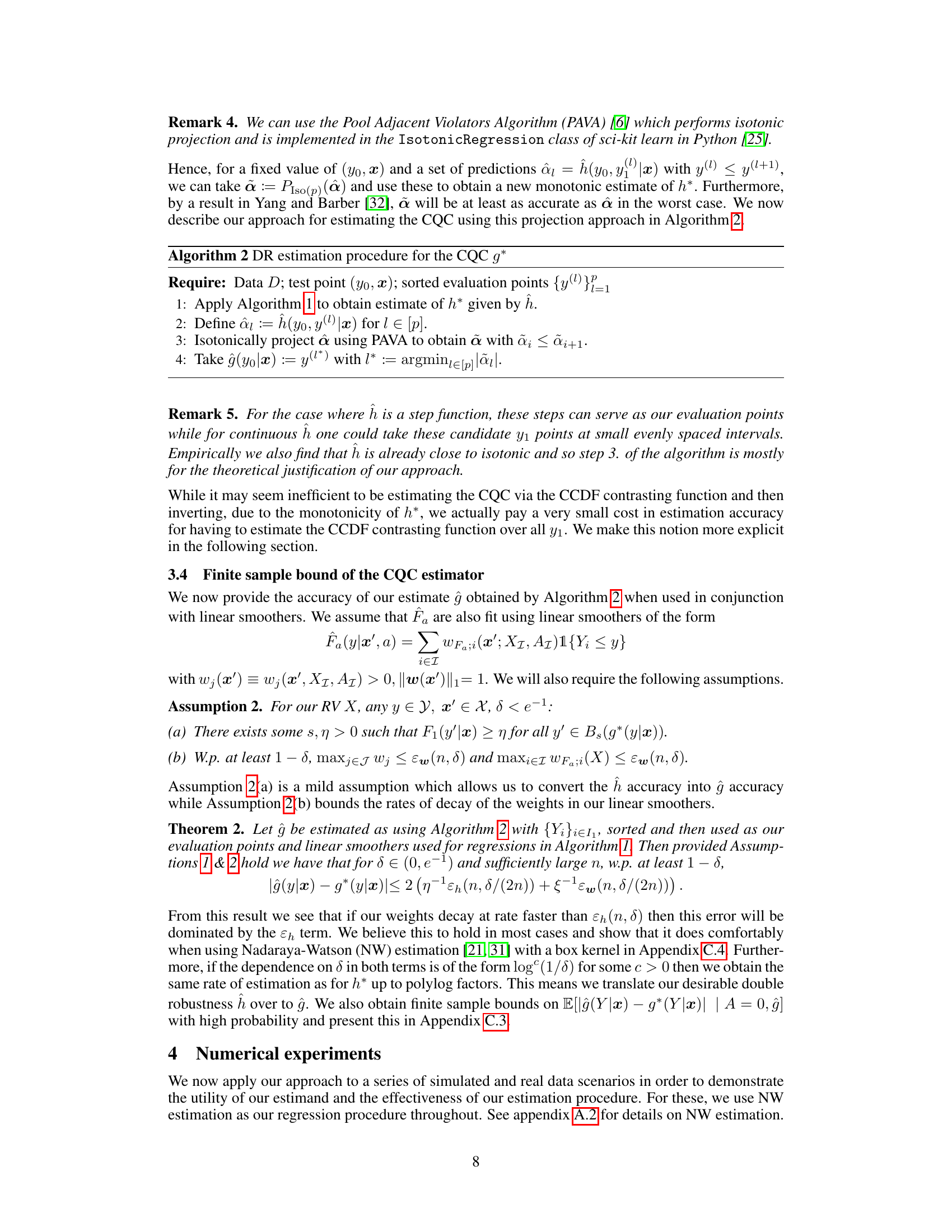

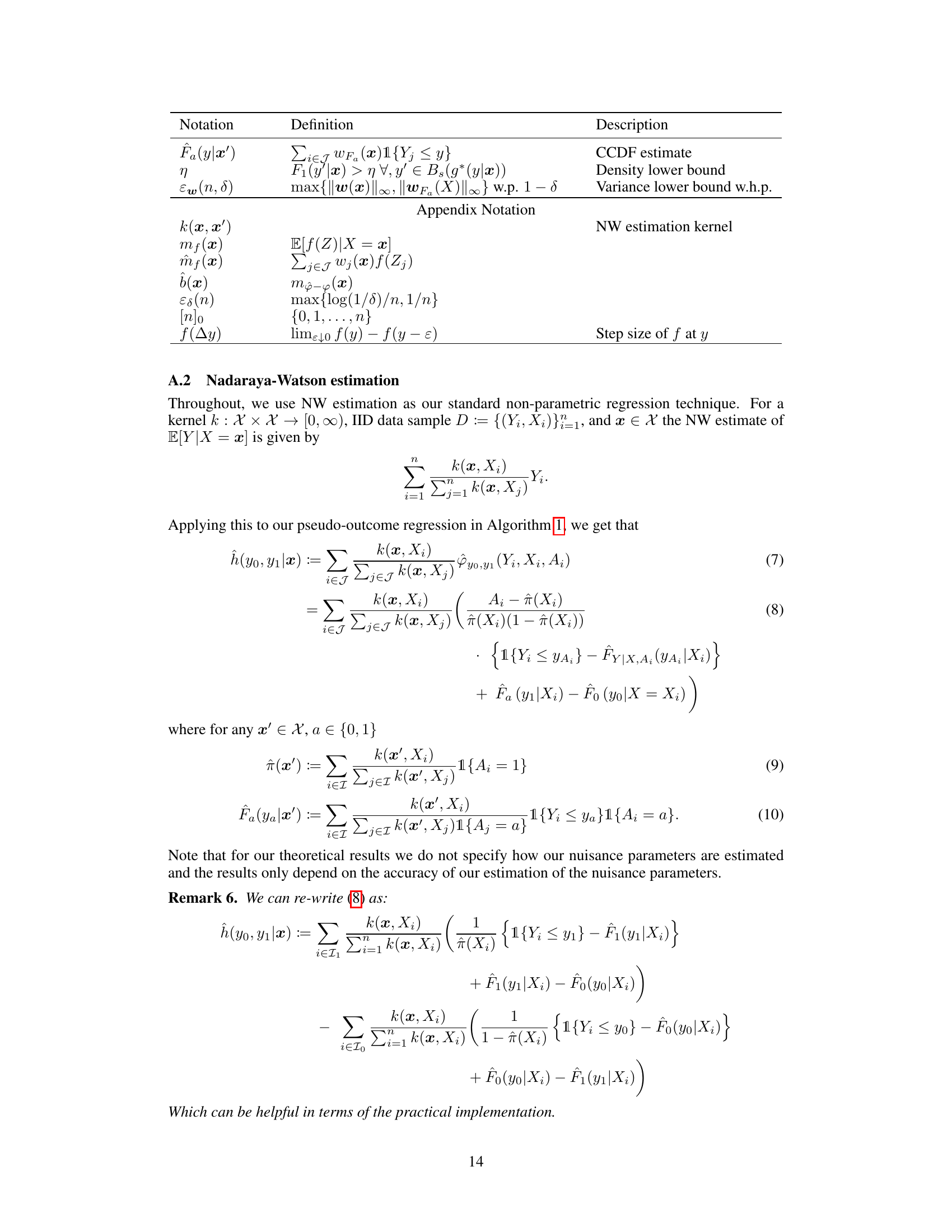

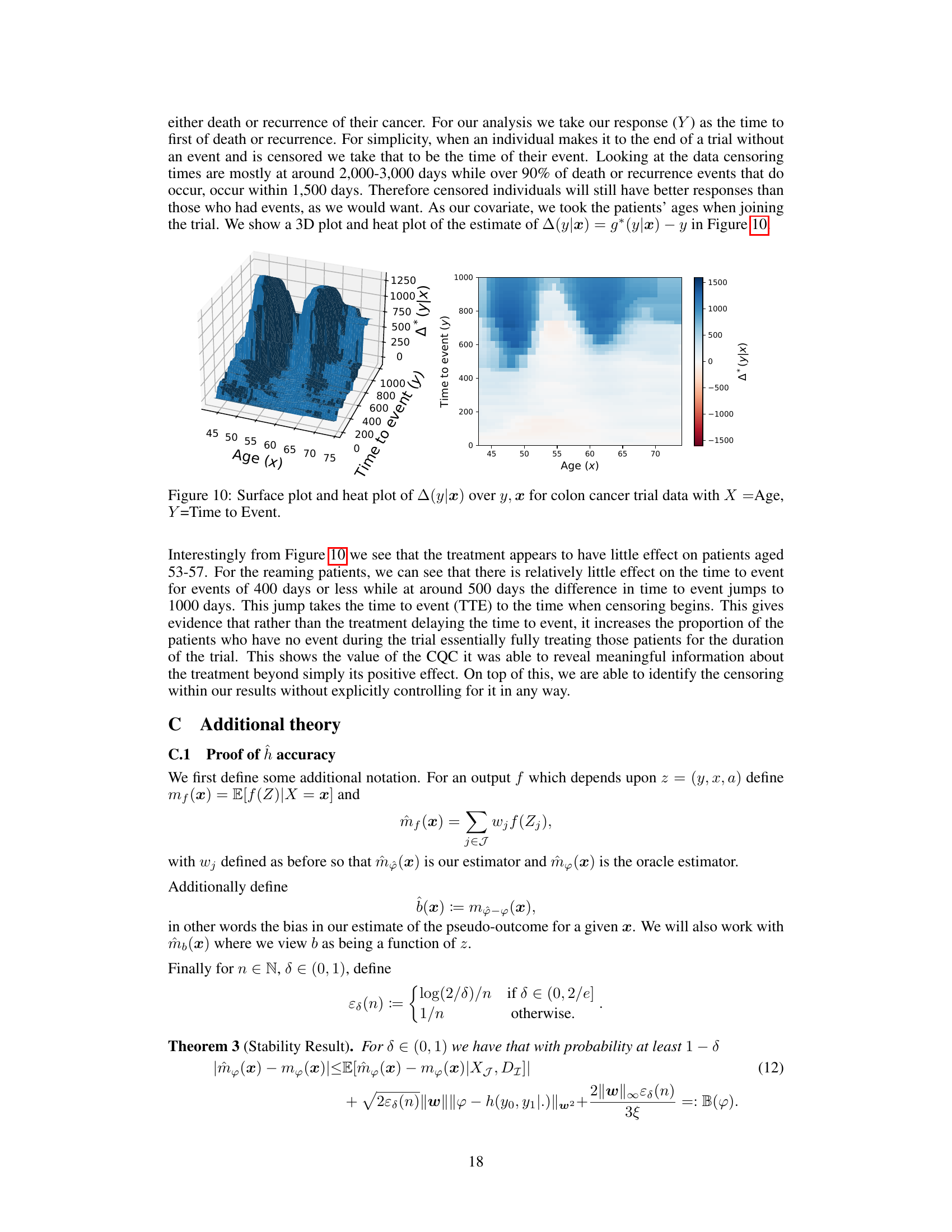

This figure shows surface plots of the Conditional Cumulative Distribution Function (CCDF), Conditional Quantile Comparator (CQC), and Conditional Quantile Treatment Effect (CQTE). It demonstrates a key characteristic of the CQC: its smoothness even when the individual CCDF’s are not smooth. The CCDF and CQTE show significant high-frequency variation along the x-axis, reflecting the complexity in the marginal outcome distributions. In contrast, the CQC surface is significantly smoother, highlighting a key advantage of using the CQC as an estimand for heterogeneous treatment effect (HTE) analysis.

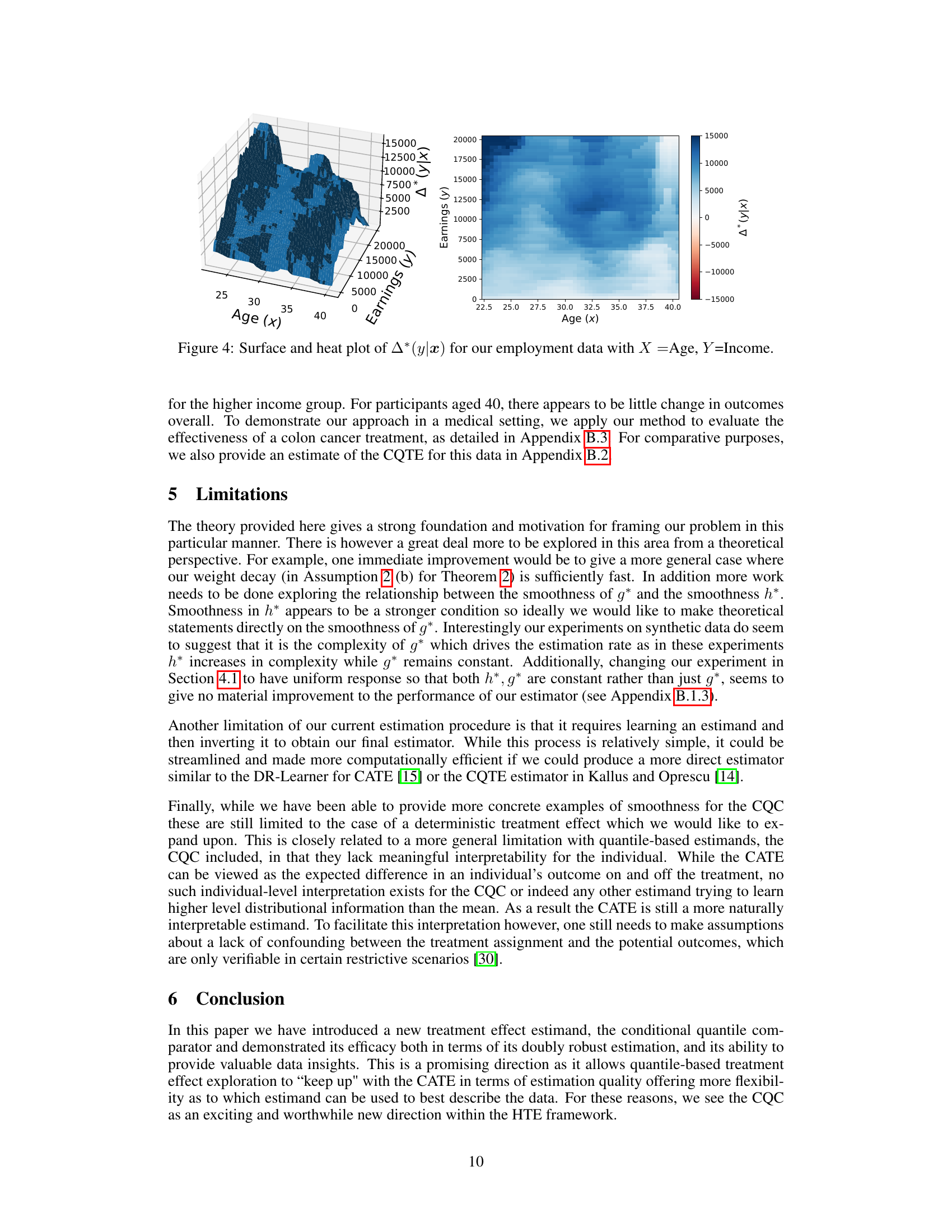

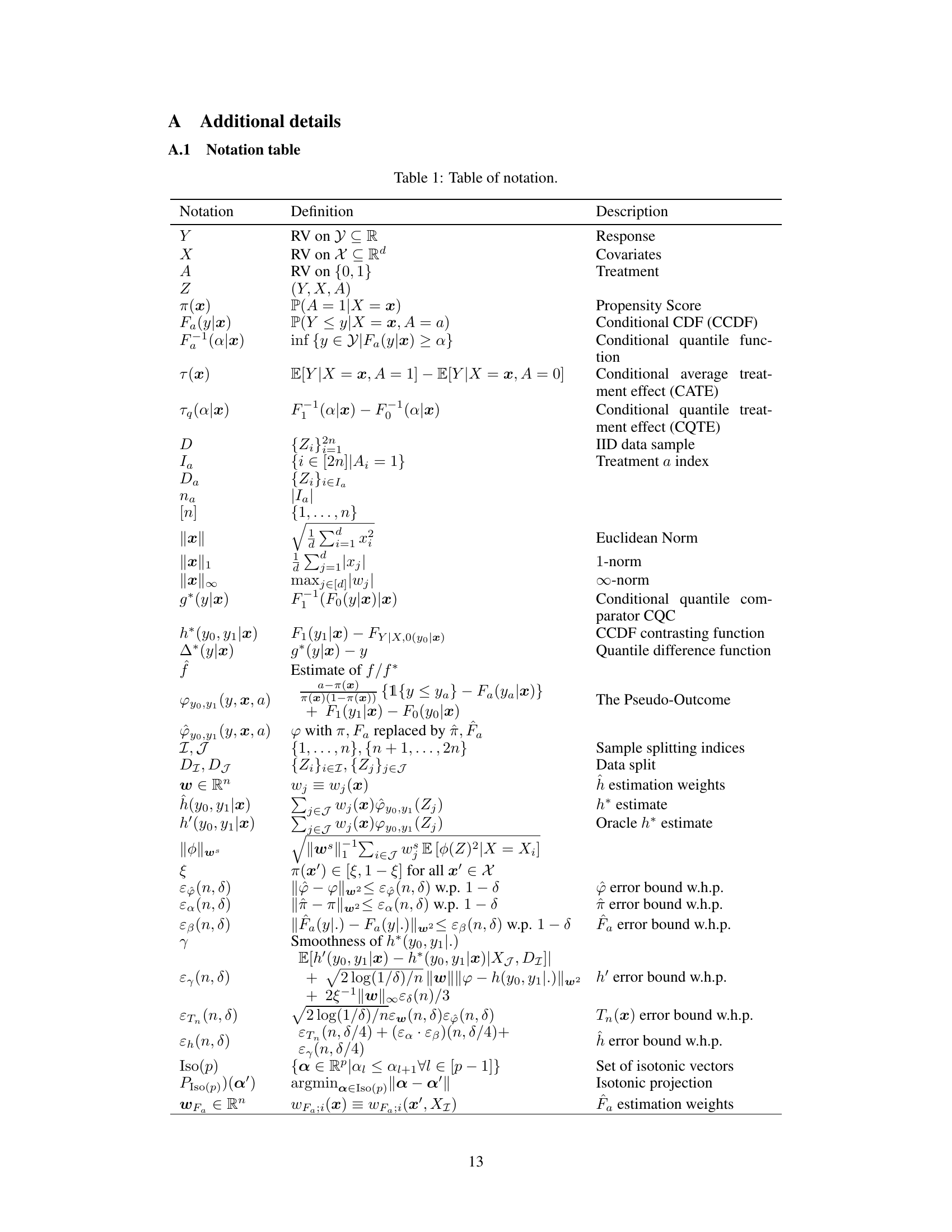

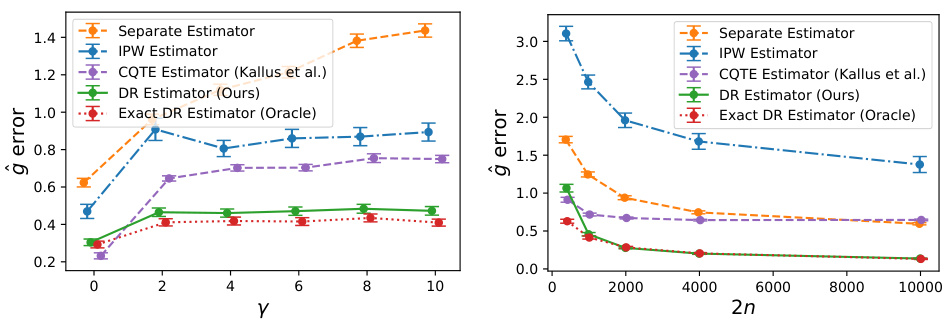

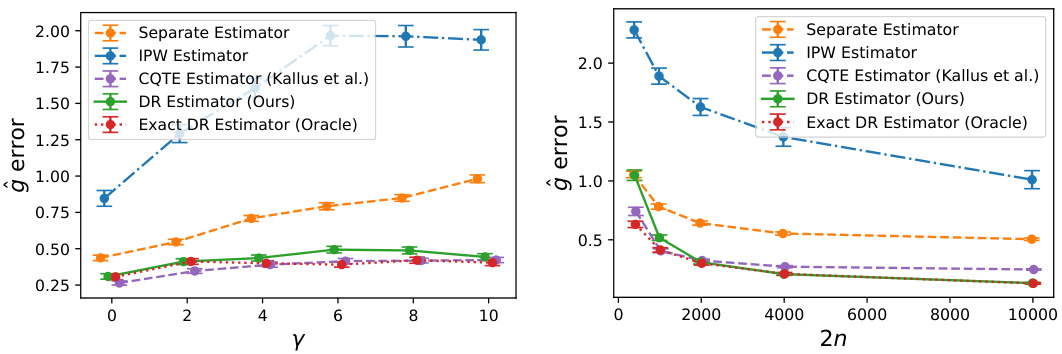

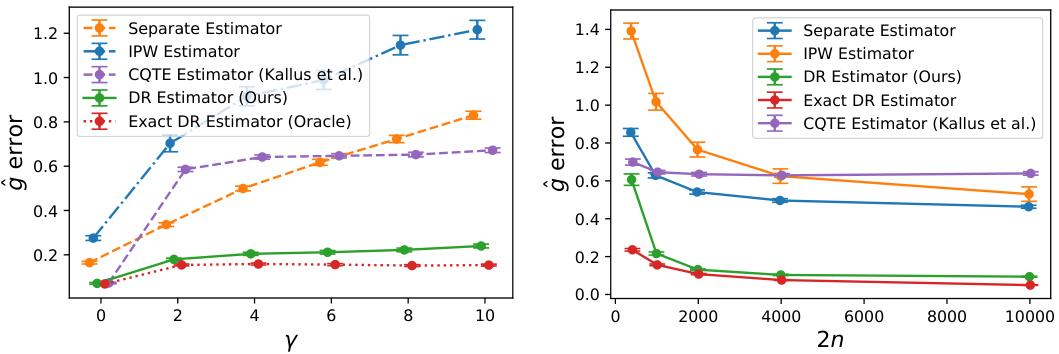

This figure displays the mean absolute error and 95% confidence intervals for five different estimators of the conditional quantile comparator (CQC): a separate estimator, an IPW estimator, the CQTE estimator by Kallus and Oprescu, the proposed DR estimator, and an oracle DR estimator. The left panel shows the results with a fixed sample size of 1000 and varying γ (a parameter controlling the smoothness of the nuisance parameters), demonstrating the impact of increasing γ on estimator accuracy. The right panel shows the results with a fixed γ of 6 and varying sample size, illustrating the effect of increased data on the estimators’ accuracy. The figure visually compares the performance of the different estimators across different levels of smoothness and data quantity.

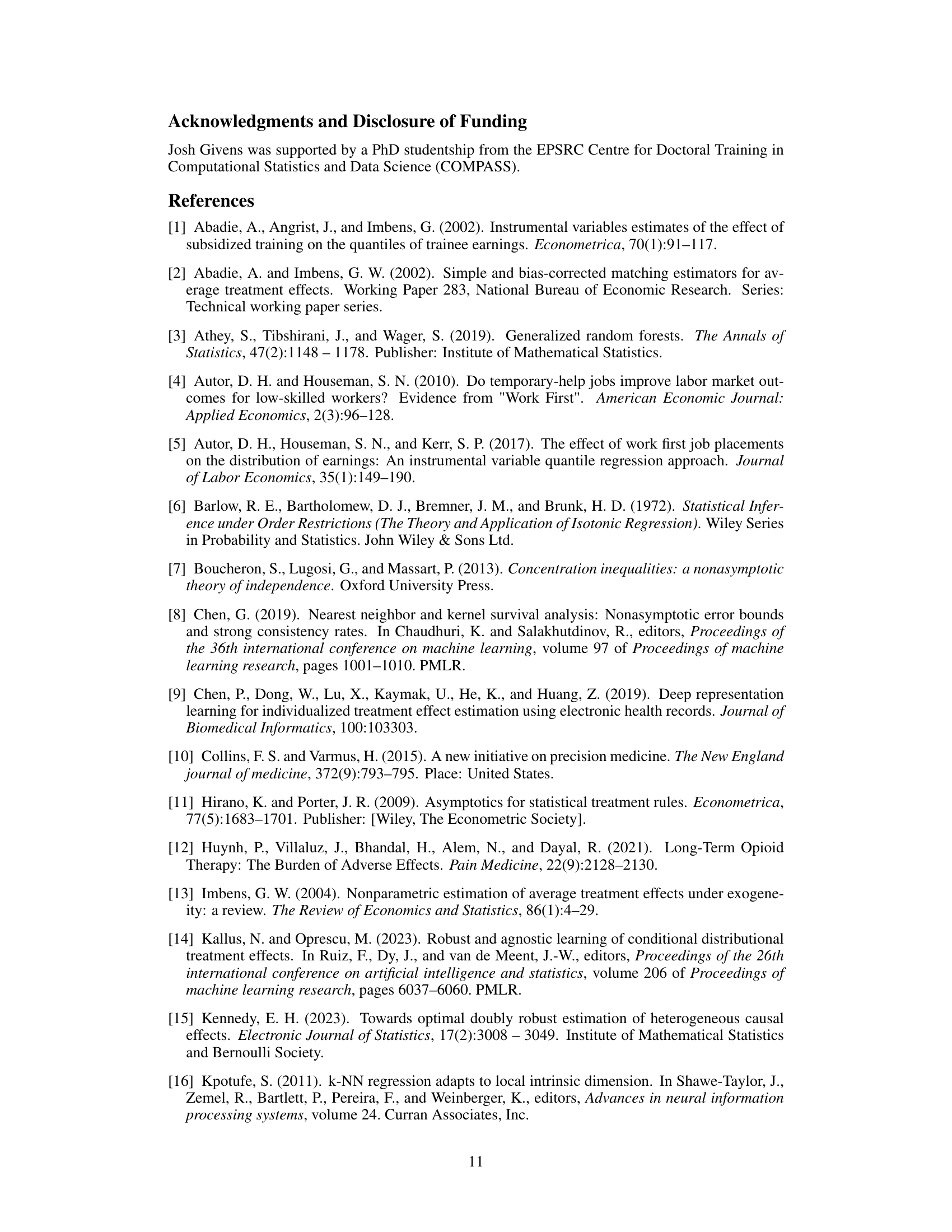

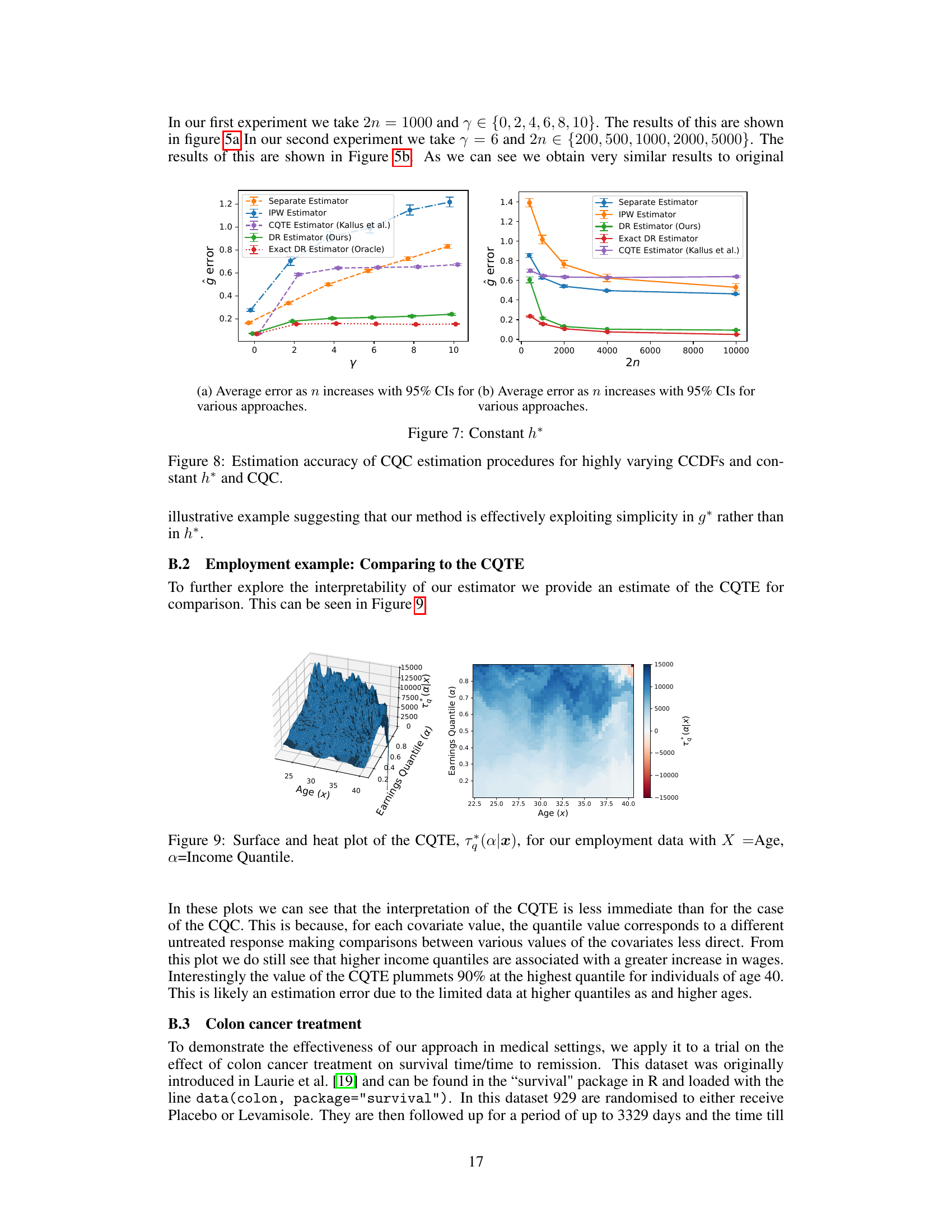

This figure visualizes the effect of an employment intervention program on income, considering age as a covariate. The left panel shows a 3D surface plot, illustrating the change in income (∆(y|x) = g(y|x) - y) for different quantiles of untreated income (y) and various ages (x). The right panel displays a heatmap representation of the same data, making it easier to identify patterns and trends. Darker colors represent larger positive or negative changes in income.

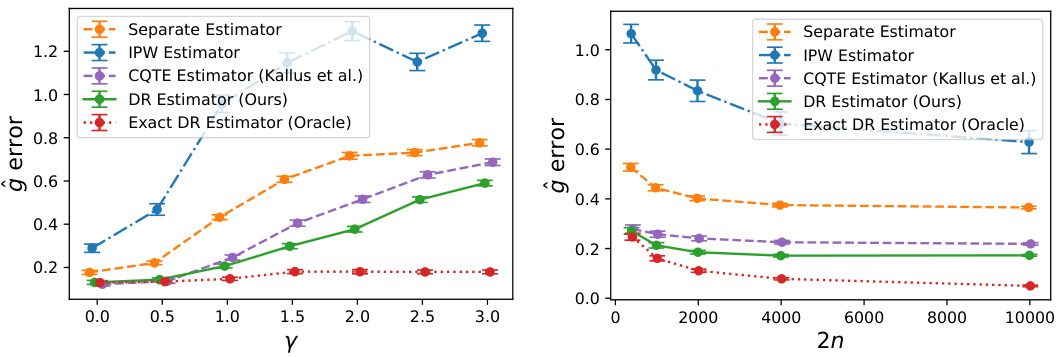

This figure shows the mean absolute error for different estimators of the conditional quantile comparator (CQC) under two experimental settings. The left panel varies the frequency of the sine function (γ) while keeping the sample size constant, demonstrating how estimator performance changes with increasing complexity of the nuisance parameters. The right panel varies the sample size (2n) while holding γ constant, illustrating the impact of sample size on estimation accuracy. The estimators compared are a separate estimator (estimating the two CCDFs separately), an IPW estimator, the CQTE estimator of Kallus and Oprescu, the proposed doubly robust (DR) CQC estimator, and an oracle DR estimator (using the true nuisance parameters). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

This figure shows the mean absolute error with 95% confidence intervals for different estimators of the conditional quantile comparator (CQC). The left panel shows the impact of increasing the frequency of the sine term (γ) in the simulated data, while keeping the sample size constant at 2000. The right panel examines the effect of increasing the sample size (2n) on estimation accuracy for a fixed frequency (γ = 6). The estimators compared include a separate estimator for CCDFs, an IPW estimator, the CQTE estimator by Kallus and Oprescu, the proposed doubly robust (DR) estimator for the CQC, and an oracle DR estimator with perfect nuisance parameter estimates. This illustrates how the proposed method’s accuracy improves with larger sample sizes and its relative robustness to the smoothness of the nuisance parameters compared to other approaches.

This figure displays the mean absolute error and 95% confidence intervals for five different estimators of the conditional quantile comparator (CQC): a separate estimator, an inverse propensity weighting (IPW) estimator, the CQTE estimator by Kallus and Oprescu (2023), the doubly robust (DR) estimator proposed in this paper, and an oracle DR estimator. The left panel shows the results with a fixed sample size (2n=1000) and varying γ (a parameter controlling the smoothness of the nuisance parameters). The right panel shows the results for a fixed γ (γ=6) and varying sample sizes (2n). The plots illustrate the performance of each method as a function of γ and sample size, demonstrating that the proposed DR estimator generally outperforms the other estimators, particularly in challenging scenarios with high γ values (less smooth nuisance parameters).

This figure compares three different visualizations related to treatment effect: the conditional cumulative distribution function (CCDF), the conditional quantile comparator (CQC), and the conditional quantile treatment effect (CQTE). The plots demonstrate the smoothness properties of the CQC and show that in this example, the CQC is smoother than the other two functions. Specifically, the CCDF and CQTE show rapid variations along the x-axis, while the CQC remains relatively flat. This illustrates the main benefit of using the CQC for cases where the marginal response distribution is complex but the comparator quantity is smooth.

This figure compares three different visualizations of the same data: the conditional cumulative distribution function (CCDF), the conditional quantile comparator (CQC), and the conditional quantile treatment effect (CQTE). The x-axis represents covariates, and the y-axis represents the response variable. The CCDF and CQTE show high-frequency changes along the x-axis, indicating complexity in the individual response distributions. In contrast, the CQC surface shows a smoother response across the x-axis, highlighting a simpler relationship between the treated and untreated response distributions. This demonstrates the CQC’s desirable property of maintaining smoothness even when individual CCDFs are not smooth.

More on tables

This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper, defining the variables, functions, and their descriptions. It includes mathematical symbols and their corresponding meanings within the context of the paper’s research on heterogeneous treatment effects.

This table provides a comprehensive list of notations used throughout the paper, defining each symbol and providing a brief description of its meaning. It includes variables, functions, and estimates related to the conditional quantile comparator (CQC), conditional average treatment effect (CATE), and other key concepts in the study of heterogeneous treatment effects.

This table lists notations used throughout the paper, including the definition and description of each notation. It covers variables (Y, X, A, Z), functions (π, Fa, F⁻¹, τ, τq, g*, h*, Δ*), sets (I, Ia, Da, [n]), norms (||.||, ||.||₁, ||.||∞), and various estimates. The table is essential for understanding the mathematical formulas and algorithms presented in the paper.

Full paper#