↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Foundation models excel in reasoning and memorizing across modalities; however, they often lack generalizability across tasks and granularities. Current approaches typically focus on single modality or limited task settings. This limits their potential applications for unified image and dataset-level understanding. The paper addresses this limitation by proposing a generalized solution.

The proposed solution, FIND, uses a lightweight transformer interface without tuning foundation models. FIND achieves interleaved understanding across different modalities and granularities (pixel-to-image), enabling simultaneous handling of various tasks like segmentation, grounding, and retrieval. The introduction of FIND-Bench, a new benchmark dataset with COCO images and new annotations, allows for effective evaluation of the proposed method’s capabilities. The results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance on FIND-Bench and competitive performance on standard benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces FIND, a novel interface that unifies foundation models’ embeddings for various vision-language tasks. This work addresses the limitations of specialized models by creating a generalized, interleaved understanding framework. FIND-Bench, a new dataset, further enhances the research, paving the way for future interleaved multi-modal research. The generalizability and extensibility of FIND make it highly relevant to current research trends and open avenues for several applications.

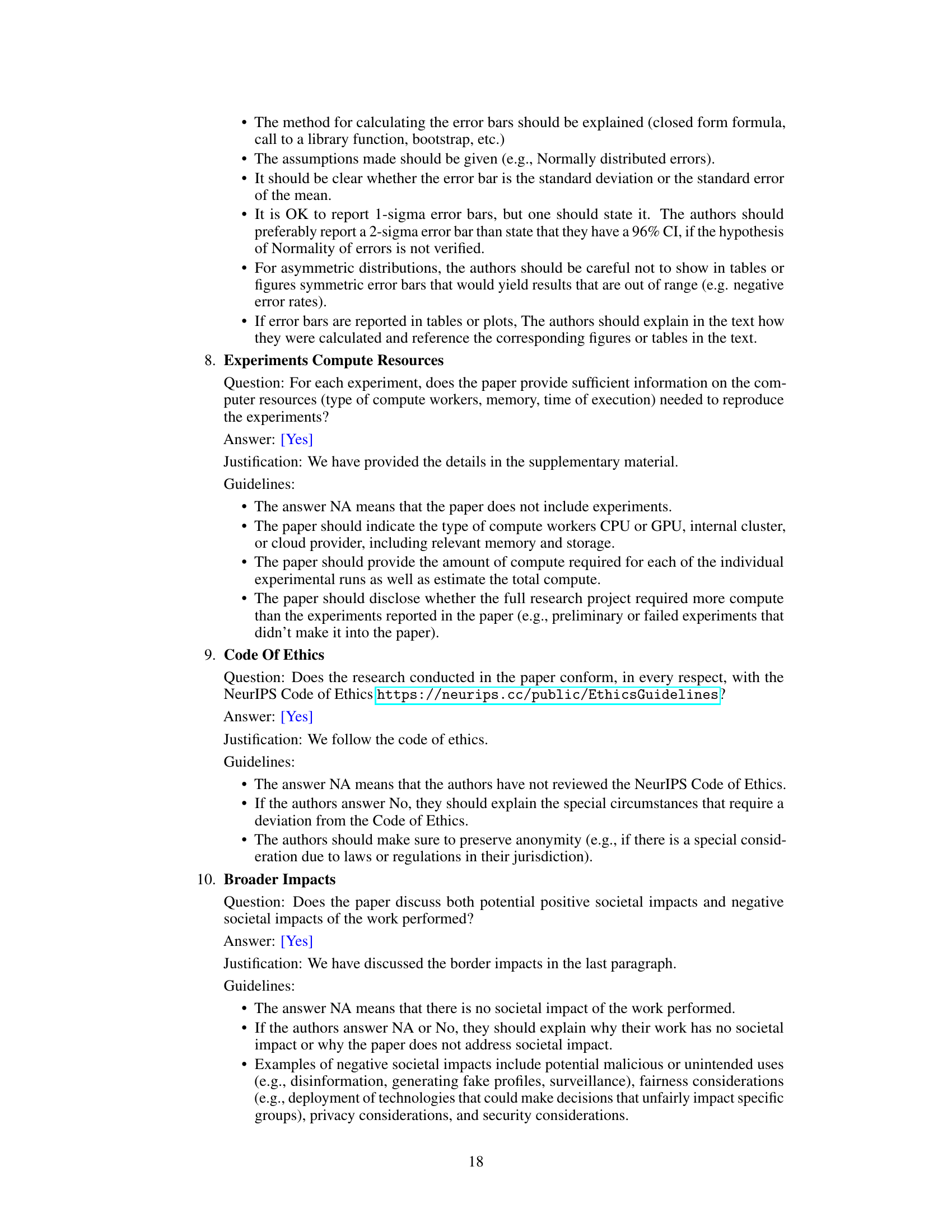

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the FIND (INterface for Foundation models’ embeDdings) interface’s versatility in handling various tasks across different granularities (from pixel-level to image-level) and modalities (vision and language). It shows examples of different tasks, including interleave segmentation, long-context segmentation, generic segmentation, interleave grounding, and interleave retrieval, showcasing how FIND adapts to these tasks without needing to tune the underlying foundation model weights. The retrieval space used in the examples is from the COCO validation set.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

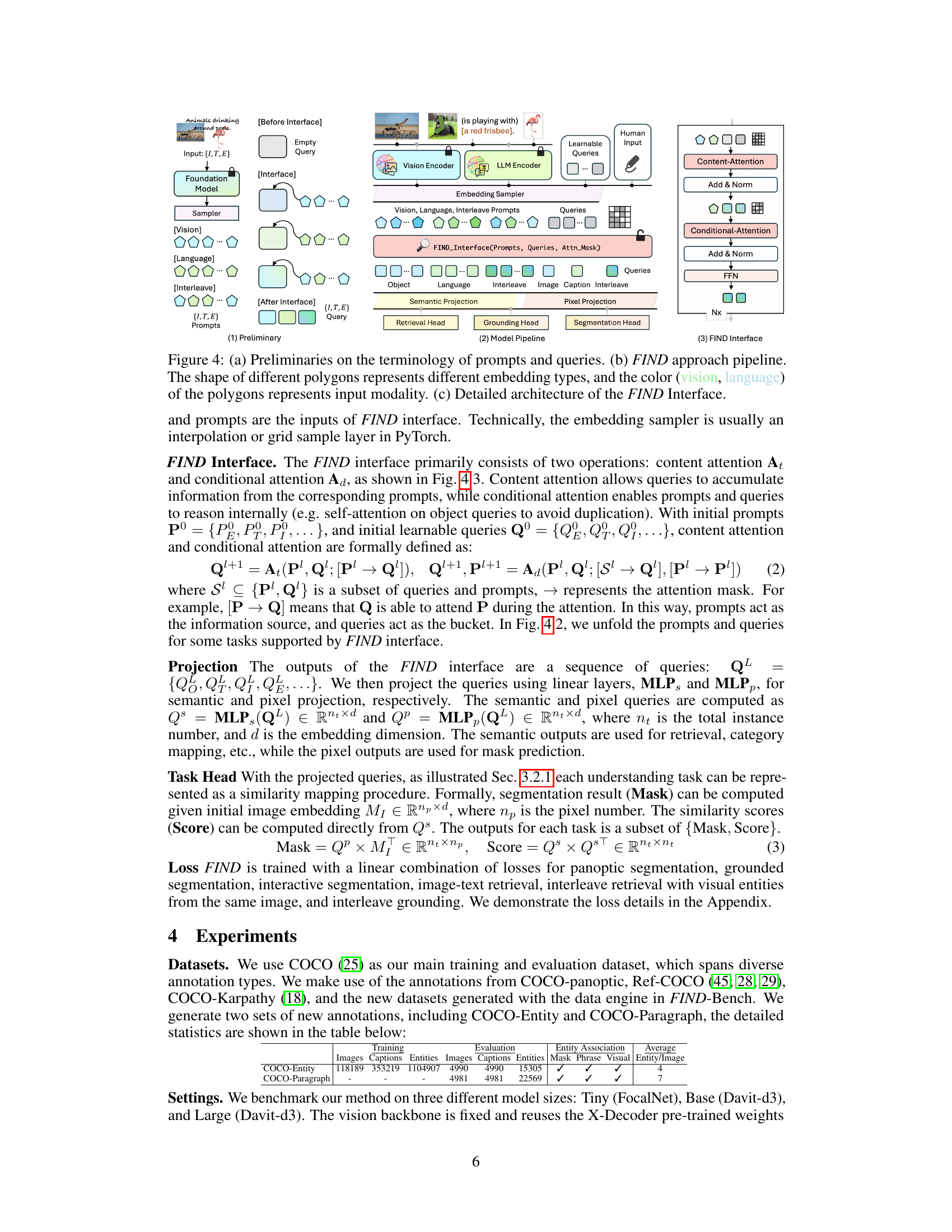

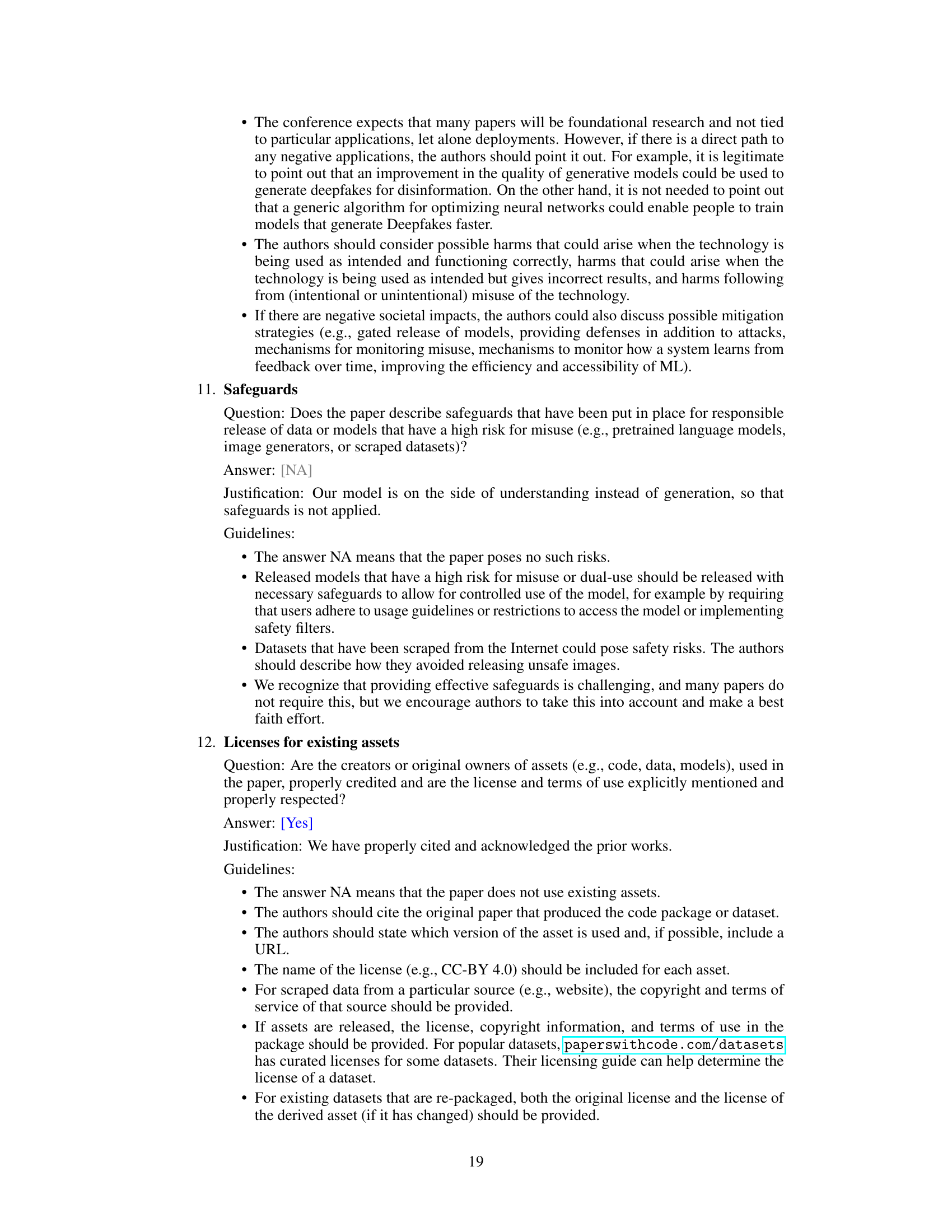

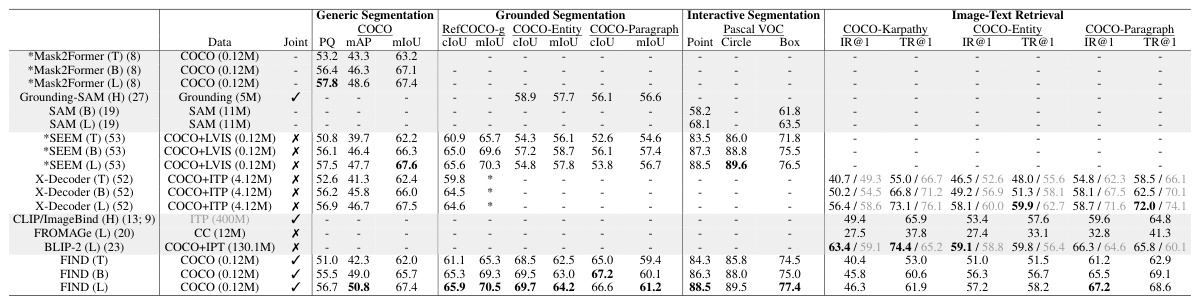

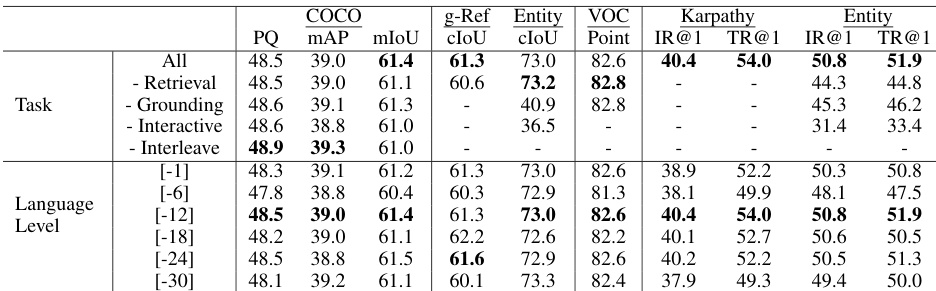

🔼 This table compares FIND’s performance on various multi-modal understanding tasks against several strong baselines. It highlights FIND’s generalizability by evaluating its performance across generic segmentation, grounded segmentation, interactive segmentation, and image-text retrieval tasks. Key metrics include mIoU, cIoU, PQ, MAP, and IR@1/TR@1. The table also notes specific details about the baseline models’ training setups (e.g., use of deformable vision encoders, language backbones, and ensemble methods) to provide a more nuanced comparison. It showcases that FIND, even without a deformable vision encoder, achieves competitive performance, demonstrating the effectiveness of its unified training approach.

read the caption

Table 2: Benchmark on Generalizable multi-modal understanding tasks with one model architecture joint training for all. *Unlike Mask2Former and SEEM, FIND is not trained with a deformable vision encoder. We report un-ensemble/ensemble results for X-Decoder, and the finetuned/pre-trained results for blip2. Note that we compute the ITC score for blip2 instead of ITM. unless specified as SAM. The language backbone is a fixed LLaMA-7B, unless specified as UniCL. During training, we train the FIND-Interface jointly on all the tasks unless specified.

In-depth insights#

FIND Interface#

The FIND Interface, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach to unifying image and text data processing. Its core strength lies in creating an interleaved embedding space, allowing seamless interaction between vision and language models. This interleaving facilitates multi-modal understanding, going beyond simple concatenation by enabling the models to learn shared representations and contextual relationships. The interface is designed to be generalizable, adaptable to various tasks like segmentation, grounding, and retrieval, without requiring retraining of the underlying foundation models. Furthermore, the FIND interface is flexible, accommodating different foundation models and is extensible, easily adaptable to new tasks. This modular and adaptable design is a key strength because it allows for easy integration of new models and tasks into a unified framework. The interleaved nature of the interface makes it highly effective at tasks requiring joint reasoning across modalities, leading to substantial performance improvements compared to traditional multi-modal methods.

Benchmarking FIND#

Benchmarking FIND, a novel interface for aligning foundation models’ embeddings, necessitates a multifaceted approach. FIND-Bench, a newly introduced dataset with annotations for interleaved segmentation and retrieval, is crucial for evaluating FIND’s performance. Standard benchmarks for retrieval and segmentation tasks should also be utilized for comparison with existing state-of-the-art methods. The evaluation should cover various aspects, including generalizability across tasks (retrieval, grounding, segmentation), flexibility with different model architectures, and extensibility to new tasks and foundation models. Quantitative metrics, such as mIoU, cIoU, and IR@K, should be rigorously reported, along with qualitative analysis of results to understand strengths and weaknesses. Ablation studies are needed to isolate the contributions of different FIND components, and comparisons with carefully selected baselines are essential to showcase improvement. The overall benchmarking strategy must demonstrate FIND’s unique advantages in interleaved understanding, showcasing its efficiency and effectiveness compared to traditional multimodal approaches. A robust benchmarking process will firmly establish FIND’s position within the field.

FIND’s Generalizability#

The FIND interface demonstrates strong generalizability by effectively addressing diverse tasks spanning various granularities and modalities. Its unified architecture and shared embedding space facilitate seamless adaptation to tasks like segmentation, grounding, and retrieval, without requiring any modifications to the underlying foundation models. This adaptability is a significant advantage, as it allows FIND to leverage the power of pre-trained models across multiple visual understanding problems. The consistent performance across these diverse tasks highlights FIND’s versatility and potential as a generalized interface for interleaved understanding, opening new avenues for multimodal reasoning and knowledge integration. Further investigation into FIND’s generalizability with different foundation models and datasets is warranted, to fully assess its robustness and potential limitations. This could involve expanding beyond COCO and exploring other large-scale datasets, as well as incorporating a wider range of vision and language models. The findings suggest that FIND’s effectiveness stems from the interleaved embedding space fostering a richer understanding of complex visual-linguistic interactions.

Limitations of FIND#

FIND, while a novel and promising interface, presents some limitations. Generalizability, while claimed, might be limited by its dependence on the quality of foundation model embeddings; inferior embeddings could hinder performance across diverse tasks. The interleaved shared embedding space, a key strength, could also be a weakness if not carefully managed, potentially leading to interference between tasks and reduced effectiveness. Extensibility relies on compatibility with new foundation models, requiring adaptations for different architectures and embedding structures. Finally, FIND-Bench, the proposed evaluation dataset, might not comprehensively capture the range of real-world scenarios, impacting the overall generalizability and robustness of the findings. Future work should address these limitations to enhance FIND’s practical applicability.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending FIND to encompass more diverse foundation models is crucial, evaluating its performance across various architectures and scales. Investigating the impact of different prompt engineering techniques on FIND’s capabilities would also be beneficial. Additionally, developing more sophisticated query mechanisms within the FIND interface, such as incorporating attention-based or memory-augmented approaches, could significantly improve its performance on complex tasks. Finally, a thorough exploration of the limitations of FIND’s interleaved understanding capabilities, identifying its strengths and weaknesses in specific scenarios, would strengthen its theoretical foundation and guide future developments. This includes examining its susceptibility to biases present in the training data and developing methods for mitigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

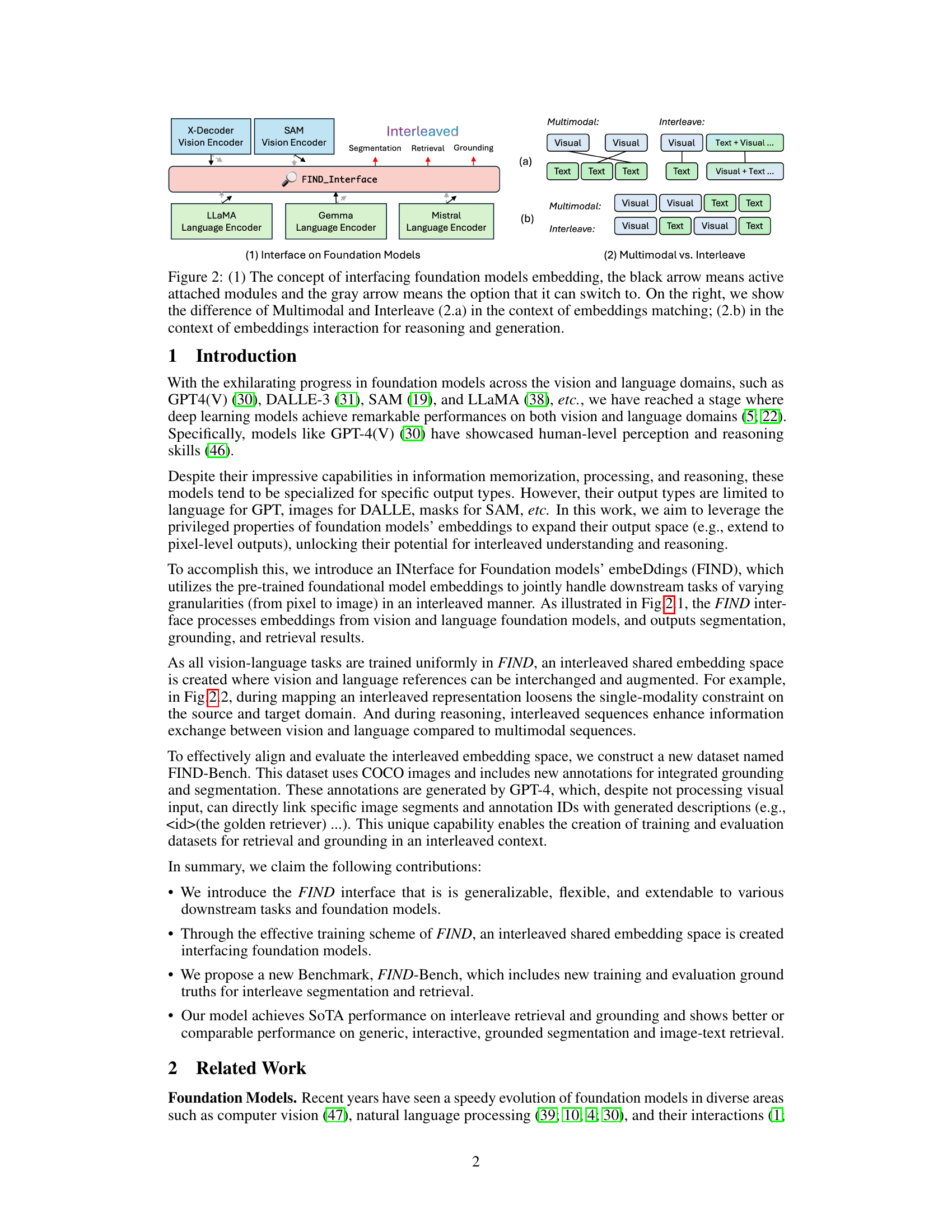

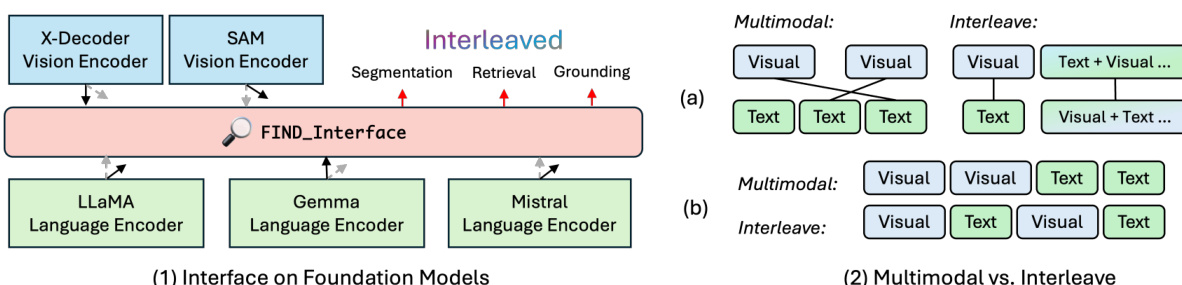

🔼 This figure illustrates the FIND interface’s design. The left panel (1) shows how FIND interfaces with various foundation models for vision and language tasks. The black arrows indicate active modules, while gray arrows represent optional ones. The right panel (2) contrasts the multimodal and interleaved approaches. Panel (2a) compares embedding matching, while (2b) examines embedding interactions for reasoning and generation in both approaches.

read the caption

Figure 2: (1) The concept of interfacing foundation models embedding, the black arrow means active attached modules and the gray arrow means the option that it can switch to. On the right, we show the difference of Multimodal and Interleave (2.a) in the context of embeddings matching; (2.b) in the context of embeddings interaction for reasoning and generation.

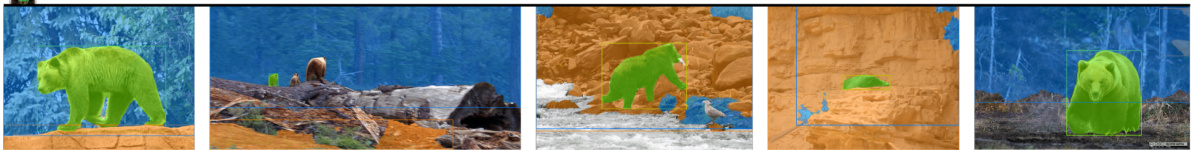

🔼 This figure illustrates the FIND (Foundation models’ embeddings INterface) framework’s versatility in handling various tasks across different granularities (from pixel to image level) and modalities (vision and language). The input can be an image, text, or a combination of both, and the output depends on the task. Examples shown include image segmentation (labeling different regions of the image), grounding (connecting textual descriptions to specific image regions), and retrieval (finding images that match a given text description). The figure showcases the generalizability of FIND, as it utilizes the same architecture for all tasks. The COCO validation set serves as the retrieval space for the example shown in the figure.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the FIND interface, a generalized interface for aligning foundation models’ embeddings. It shows how FIND handles various tasks across different granularities (pixel to image) and modalities (vision to language) using a unified architecture. The interface is shown working on examples of image segmentation, object grounding, and image retrieval. The retrieval space used for the examples in the figure is the COCO validation set.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

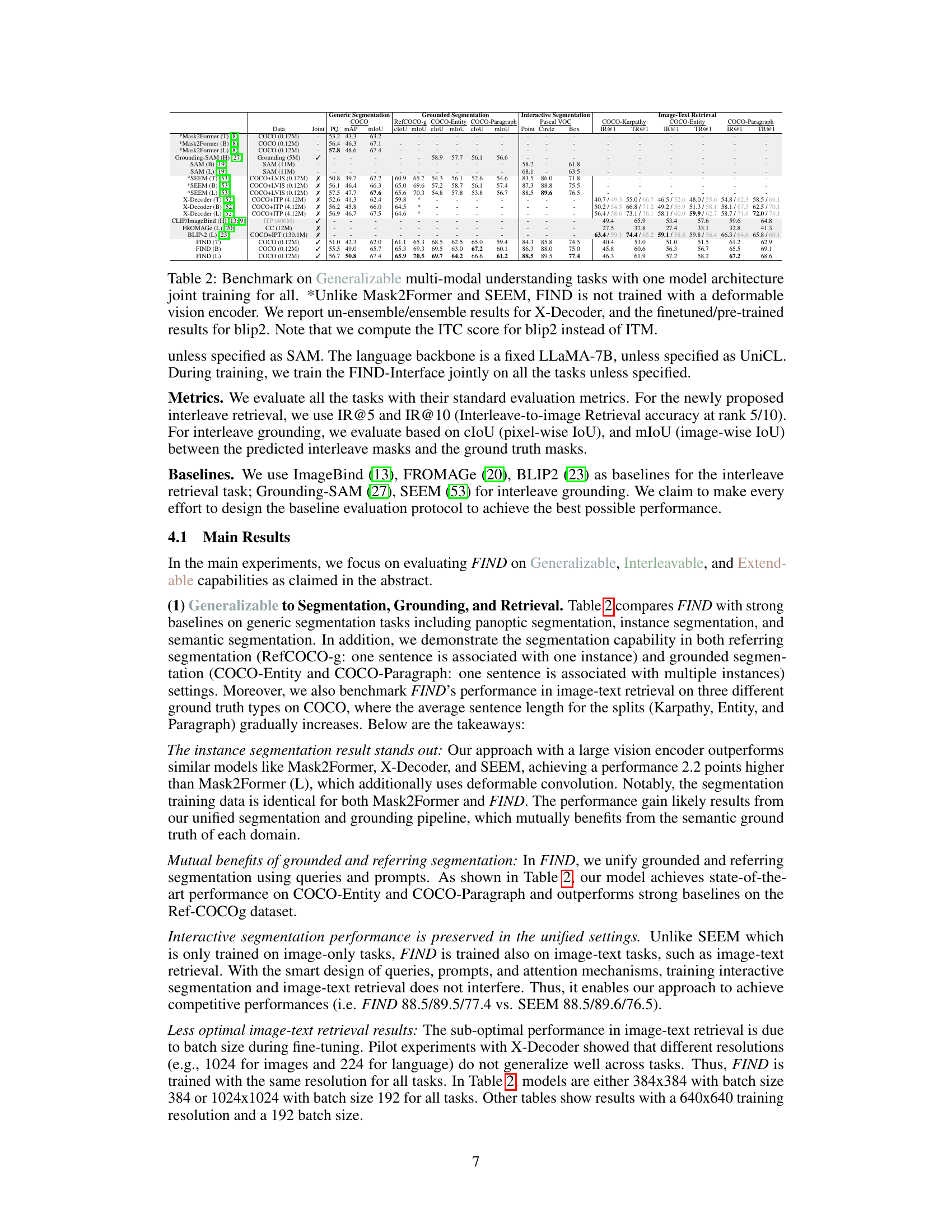

🔼 This figure illustrates the FIND interface’s architecture and workflow. (a) shows the terminology used for prompts (input embeddings) and queries (learnable embeddings). (b) provides a high-level overview of the FIND pipeline, including input processing, embedding sampling, the FIND interface itself, and final task-specific outputs. (c) delves into the detailed architecture of the FIND interface, highlighting the content and conditional attention mechanisms and their roles in aggregating and exchanging information between prompts and queries before generating final outputs (retrieval, grounding, segmentation). Different shapes and colors represent different embedding types and modalities.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Preliminaries on the terminology of prompts and queries. (b) FIND approach pipeline. The shape of different polygons represents different embedding types, and the color (vision, language) of the polygons represents input modality. (c) Detailed architecture of the FIND Interface.

🔼 This figure shows examples of different tasks that the FIND interface can handle. It demonstrates the interface’s ability to work across various granularities (from pixel-level segmentation to image-level retrieval) and modalities (vision and language). The tasks shown include interleave segmentation, long-context segmentation, generic segmentation, interleave grounding, and interleave retrieval. The examples highlight the interface’s flexibility and its ability to handle complex, interleaved information. The COCO validation set was used as the retrieval space for the image examples.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

🔼 This figure shows examples of the FIND interface’s applications across different tasks and granularities. It demonstrates FIND’s ability to perform interleave segmentation, generic segmentation, long-context segmentation, interleave grounding, and interleave retrieval. Each task showcases the interface’s ability to handle different levels of granularity (from pixel-level segmentation to image-level retrieval) and modalities (vision and language). The figure highlights the versatility of FIND in handling various visual understanding tasks, all within a unified framework. The retrieval space used for image examples is the COCO validation set.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

🔼 This figure shows examples of different tasks enabled by the FIND interface, highlighting its versatility in handling various granularities (from pixel-level segmentation to image-level retrieval) and modalities (vision and language). Each example demonstrates a different task: interleave segmentation, long-context segmentation, generic segmentation, interleave grounding, interleave retrieval, and interactive segmentation. The common element across all tasks is that they leverage the embeddings from foundation models in a unified way via the FIND interface. The image examples are all taken from the COCO validation set, further emphasizing the interface’s broad applicability.

read the caption

Figure 1: The proposed FIND interface is generalizable to tasks that span granularity (pixel to image) and modality (vision to language). The retrieval space for this figure is the COCO validation set.

🔼 This figure shows three parts: (a) illustrates the terminology of prompts and queries used in the FIND model. (b) provides a visual representation of the FIND approach pipeline, highlighting the input, embedding sampler, FIND interface, and output. Different shapes represent different embedding types, while colors indicate the modality (vision or language). (c) shows the detailed architecture of the FIND interface, including the embedding sampler, prompts, queries, and attention mechanisms.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Preliminaries on the terminology of prompts and queries. (b) FIND approach pipeline. The shape of different polygons represents different embedding types, and the color (vision, language) of the polygons represents input modality. (c) FIND Interface.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares FIND’s performance on various multi-modal understanding tasks against several strong baselines. It highlights FIND’s generalizability by showing results across generic segmentation, grounded segmentation, interactive segmentation, and image-text retrieval. The table also notes key differences in training methods between FIND and other models (e.g., the use of a deformable vision encoder).

read the caption

Table 2: Benchmark on Generalizable multi-modal understanding tasks with one model architecture joint training for all. *Unlike Mask2Former and SEEM, FIND is not trained with a deformable vision encoder. We report un-ensemble/ensemble results for X-Decoder, and the finetuned/pre-trained results for blip2. Note that we compute the ITC score for blip2 instead of ITM. unless specified as SAM. The language backbone is a fixed LLaMA-7B, unless specified as UniCL. During training, we train the FIND-Interface jointly on all the tasks unless specified.

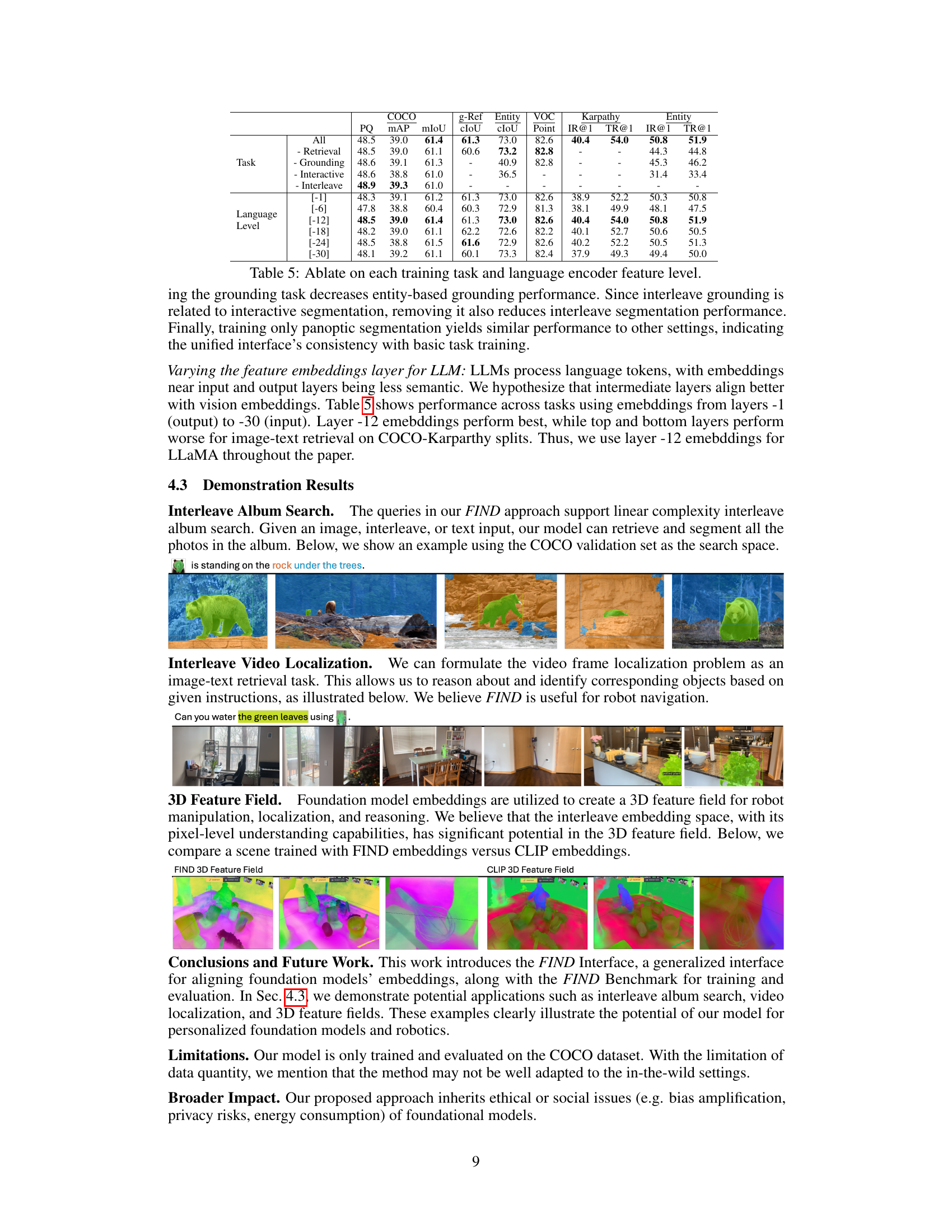

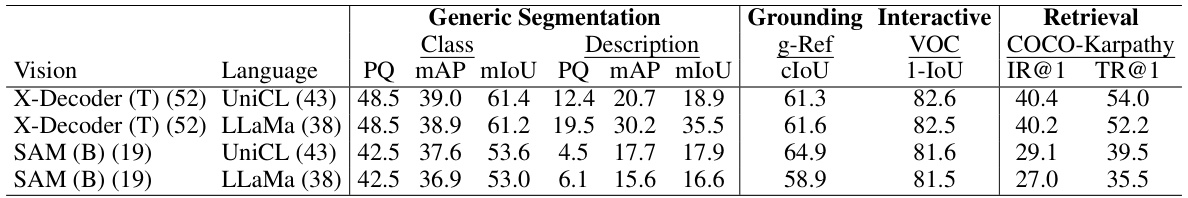

🔼 This table presents the ablation study comparing the performance of FIND using different foundation models. Specifically, it shows the results for various tasks (generic segmentation, grounding, interactive segmentation, and retrieval) when using different vision and language encoders (X-Decoder, SAM, UniCL, and LLaMA). The table helps to understand the impact of each model’s capabilities on the overall performance of FIND.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study on different foundation model architectures.

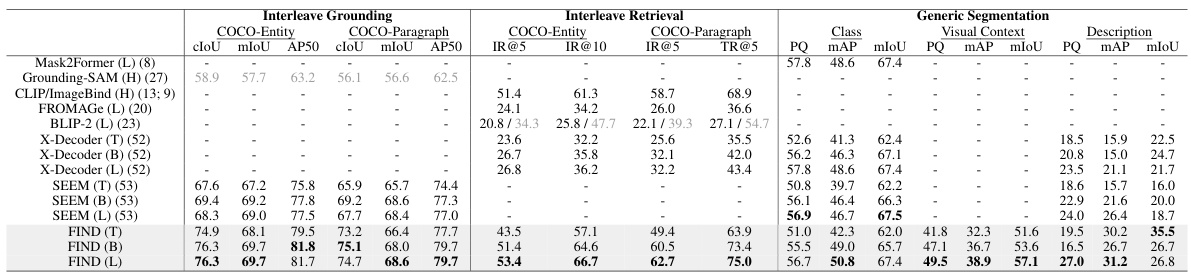

🔼 This table presents the results of a benchmark evaluating the performance of a jointly trained model on three interleaved understanding tasks: grounding, retrieval, and generic segmentation. The model uses a single set of weights for all tasks. The results are broken down by task and dataset (COCO, g-Ref, Entity, VOC, Karpathy), and metrics include cIoU, mIoU, AP50, IR@5, IR@10, PQ, and mAP.

read the caption

Table 3: Benchmark on interleaved understanding with the jointly trained model on all tasks with one set of weights. We evaluate interleave grounding, retrieval, and generic segmentation.

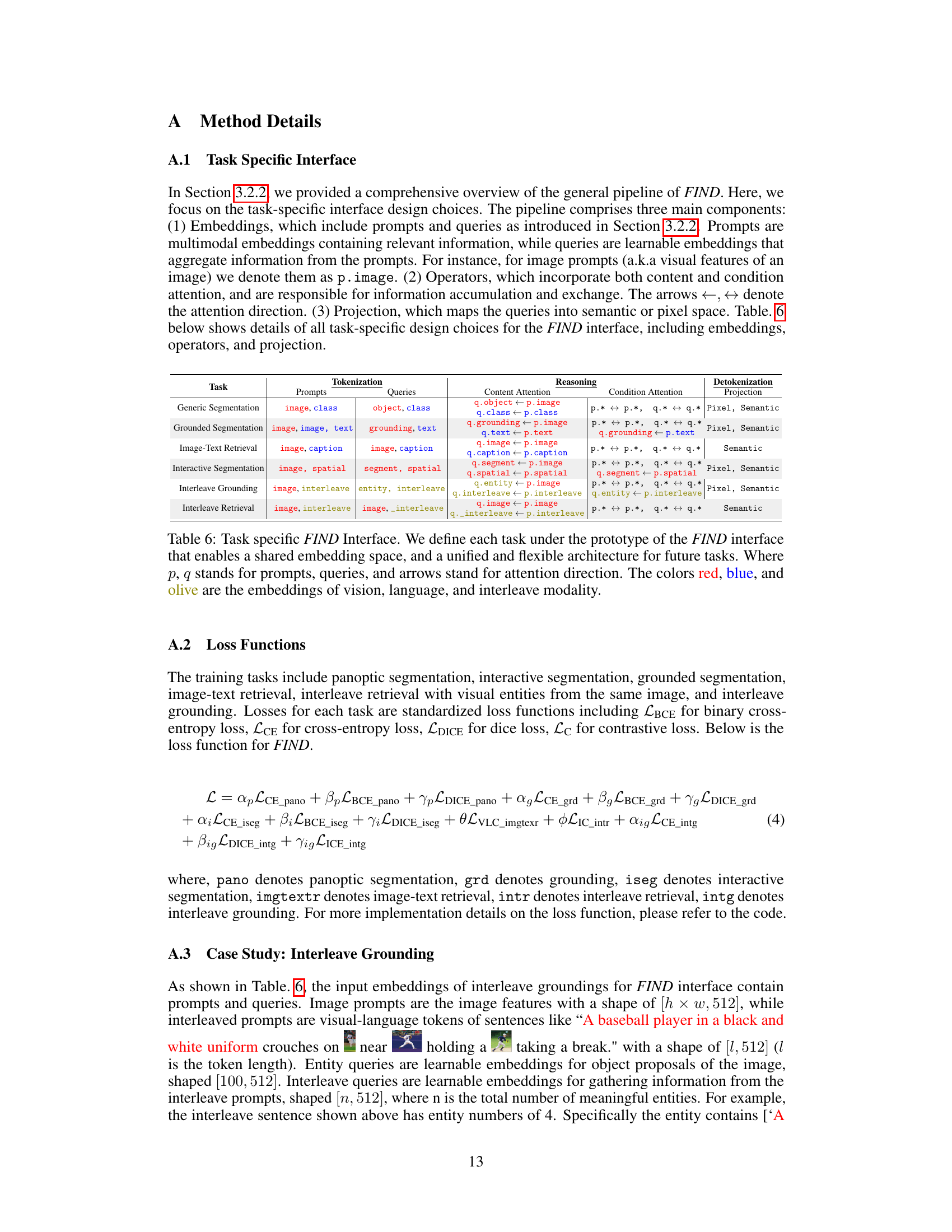

🔼 This table details the design choices for the task-specific FIND interface. It breaks down each task (Generic Segmentation, Grounded Segmentation, Image-Text Retrieval, Interactive Segmentation, Interleave Grounding, and Interleave Retrieval) into its components: prompts (input embeddings), queries (learnable embeddings), content attention (information flow from prompts to queries), conditional attention (internal reasoning within prompts and queries), and projection (mapping queries to final outputs). The table also indicates the types of embeddings used (vision, language, or interleaved) and the final output type (Pixel or Semantic).

read the caption

Table 6: Task specific FIND Interface. We define each task under the prototype of the FIND interface that enables a shared embedding space, and a unified and flexible architecture for future tasks. Where p, q stands for prompts, queries, and arrows stand for attention direction. The colors red, blue, and olive are the embeddings of vision, language, and interleave modality.

Full paper#