TL;DR#

Many scientific hypotheses involve causal relationships in complex systems where direct experimentation is difficult or impossible. Traditional experimental design often falls short in these scenarios, yielding inconclusive results due to confounding variables and non-linearity. The challenge lies in optimally designing indirect experiments to effectively answer specific scientific questions about the causal relationships, even without full knowledge of the underlying mechanism.

This paper proposes a novel adaptive experimental design strategy to address this challenge. The strategy involves sequentially narrowing the gap between upper and lower bounds on the query of interest, using a bi-level optimization process. The method efficiently estimates bounds on the causal effects by using an instrumental variable approach within a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). The effectiveness of this method is validated through experiments on multivariate, nonlinear, and confounded synthetic datasets, demonstrating its ability to improve the efficiency and informativeness of experimental design in complex systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers seeking to optimize experiments in complex systems. It provides a novel framework for designing adaptive experiments, particularly valuable when direct experimentation is challenging. By addressing the limitations of traditional methods, this research opens up new avenues for investigating causal relationships in multi-variate, non-linear, and confounded settings. This will improve decision making based on data obtained from indirect experiments in various fields.

Visual Insights#

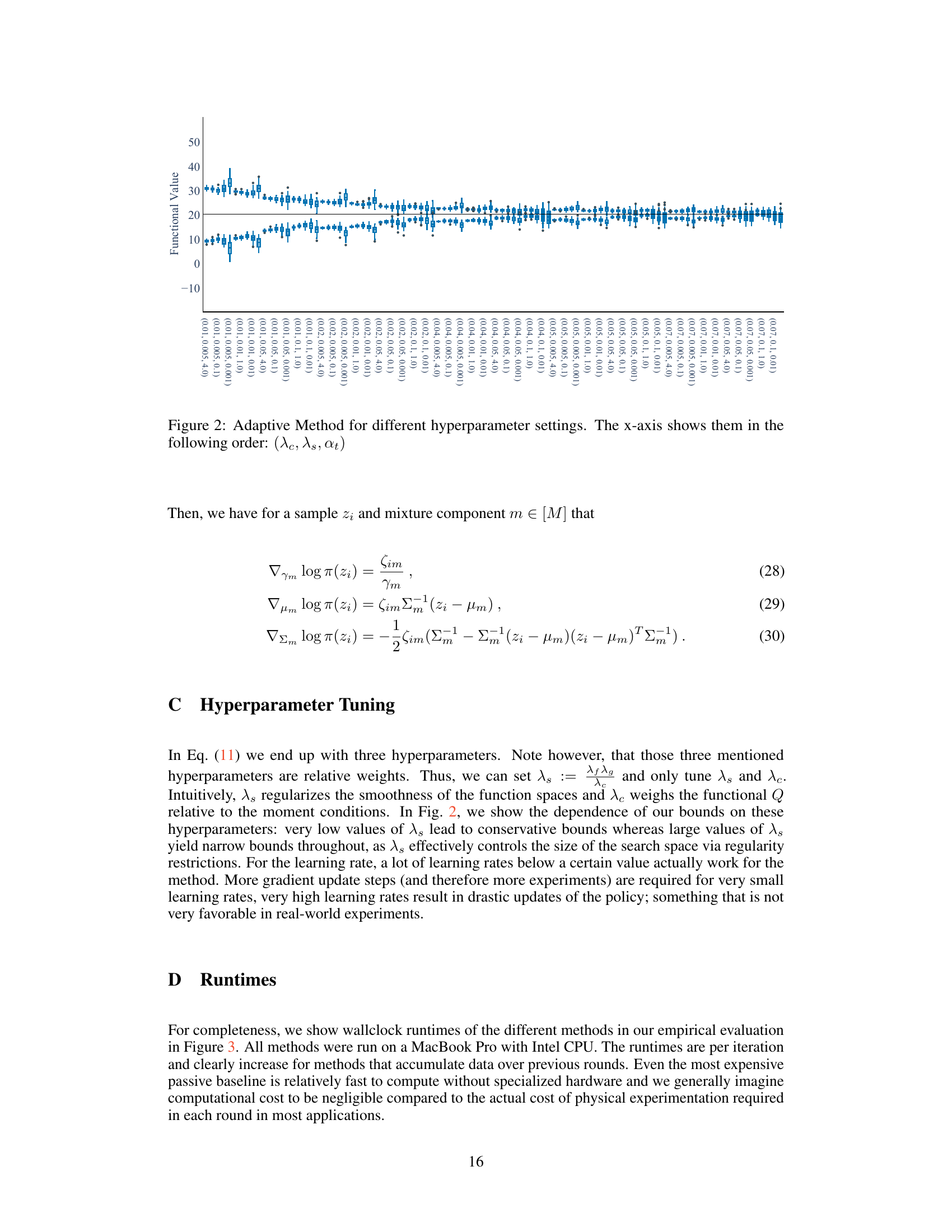

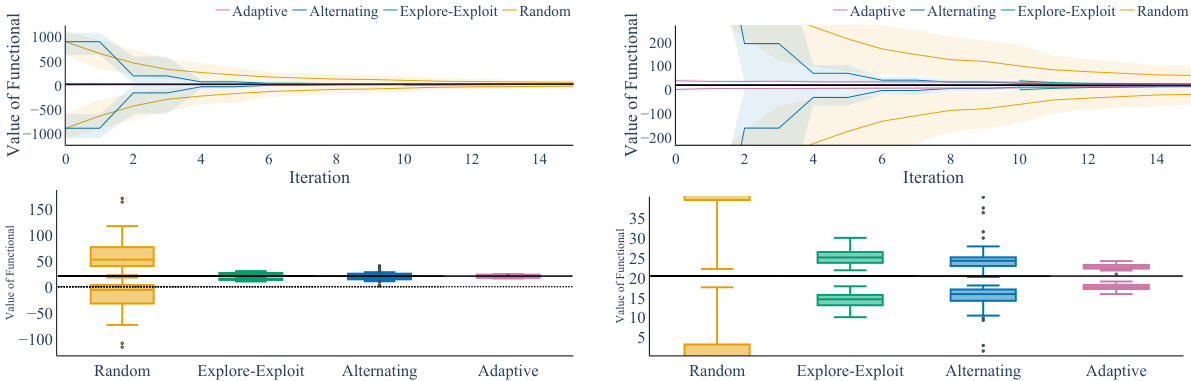

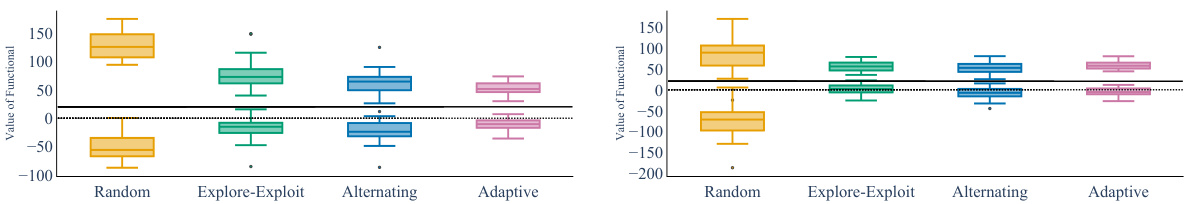

🔼 This figure compares four different strategies for sequentially updating experimentation policies to learn about a scientific query, represented as a functional Q[f0]. The top panels show how the estimated upper and lower bounds on Q[f0] evolve over 16 iterations (T) for 50 different random seeds (nseeds). The bottom panels display the final estimated bounds after 16 rounds. The figure demonstrates that the adaptive strategy outperforms other methods by significantly reducing the gap between the upper and lower bounds and efficiently identifies the true value of the query.

read the caption

Figure 1: We compare the different strategies in our synthetic setting. Left and right only differ in the range of the y-axis. The black constant line represents the true value of Q[f0]. Top: Estimated upper and lower bounds Q± over t ∈ [T] for nseeds = 50 and two different ‘zoom levels’ on the y-axis. Lines are means and shaded regions are (10, 90)-percentiles. Bottom: The final estimated bounds Q at T = 16. The dotted line is y = 0. Both locally guided heuristic (explore-then-exploit, alternating explore exploit) confidently bound the target query away from zero with a relatively narrow gap between them. Our targeted adaptive strategy is even better and essentially identifies the target query Q[f0] = 20 after T = 16 rounds.

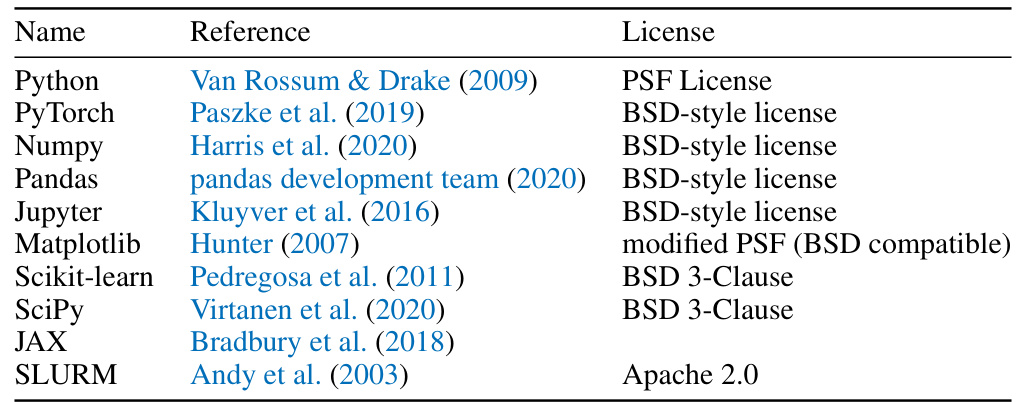

🔼 This table lists the names of various software packages and libraries used in the research project, along with their respective references and licenses. The packages cover various aspects of the workflow, including programming languages (Python), deep learning frameworks (PyTorch), numerical computation (NumPy, SciPy), data manipulation (Pandas), interactive computing (Jupyter), visualization (Matplotlib), and machine learning algorithms (Scikit-learn). The licenses indicate the terms under which these resources can be used and redistributed.

read the caption

Table 1: Overview of resources used in our work.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Experiments#

Adaptive experiments represent a powerful paradigm shift in research design, moving beyond static, pre-planned studies. Adaptive methods dynamically adjust experimental parameters (treatments, measurements, sample sizes) based on accumulating data. This iterative approach allows researchers to efficiently explore complex systems, refine hypotheses, and ultimately maximize the information gained from limited resources. The core strength lies in the ability to learn and optimize during the experiment, reducing the guesswork inherent in traditional designs. This is especially valuable in high-dimensional or non-linear settings where a priori knowledge is scarce. By strategically incorporating feedback, adaptive designs can significantly reduce the cost and time of experimentation, leading to faster discovery and more robust insights. However, the complexity of designing and implementing adaptive strategies requires careful consideration of statistical properties and computational feasibility. Careful attention to biases and overfitting is crucial, as adaptive procedures may introduce unintended influences on the experimental outcomes if not properly designed.

Causal Bounding#

Causal bounding, in the context of this research paper, is a crucial technique to address the challenges of identifying causal effects in complex, high-dimensional systems with unobserved confounders. Instead of aiming for precise causal effect estimation, which might be impossible given the data limitations, causal bounding focuses on establishing informative upper and lower bounds for the causal effect of interest. This approach is particularly valuable when direct experimentation on the target variables is difficult or impossible. By sequentially designing experiments and iteratively tightening these bounds, the method provides increasingly reliable insights into the causal relationship, even when the underlying mechanism is nonlinear and the variables are multivariate. The focus is shifted from identifying the precise causal effect to narrowing the uncertainty interval around the true value, allowing for robust inference and a quantification of the uncertainty associated with the estimates. Kernel-based methods appear crucial for efficiently estimating these bounds, potentially leveraging the structure of the underlying functions. The adaptive approach of this framework, adjusting the experimental design based on prior observations, is an important aspect to achieve efficiency and minimize the uncertainty interval in a resource-constrained experimental setting. This method makes significant contributions for scientific research and enhances the reliability of causal inference in practical applications, such as drug discovery and microbial ecology, where traditional approaches might be infeasible.

RKHS Estimation#

Employing Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (RKHS) for estimation offers a powerful, non-parametric approach to tackle complex, nonlinear relationships within the context of causal inference. This approach is particularly useful when dealing with high-dimensional data where traditional parametric methods may fall short. By assuming that the underlying function lies within an RKHS, we can leverage the representer theorem to express the estimator as a linear combination of kernel functions evaluated at the observed data points. This results in a tractable, albeit potentially high-dimensional, optimization problem. Kernel choice is crucial, impacting the smoothness and flexibility of the learned function; it requires careful consideration based on prior knowledge of the data and the nature of the relationships being modelled. While RKHS estimation provides a flexible framework, it also presents challenges such as computational complexity, particularly with large datasets, and the potential for overfitting if regularization is not carefully implemented. The effectiveness of this method relies heavily on the proper selection of kernels and regularization parameters, and careful consideration is needed to avoid these pitfalls. Despite these limitations, RKHS estimation offers a valuable tool for analyzing complex relationships within causal settings, especially when dealing with high-dimensional and/or non-linear data.

Policy Learning#

The concept of ‘Policy Learning’ within the context of the research paper centers on the iterative refinement of experimental strategies to optimally gather information. It’s not simply about choosing experiments randomly; instead, it involves a feedback loop, where results from previous experiments inform the design of subsequent ones. This adaptive approach is crucial because experiments are often costly and the relationship between interventions and outcomes can be complex and nonlinear. Sequential learning is key—decisions aren’t made in isolation but build upon accumulated data. The goal is to minimize the uncertainty around the key scientific query efficiently by strategically choosing experiments, effectively narrowing the gap between upper and lower bounds on the query’s value. A crucial aspect is dealing with the underspecification inherent in many real-world scenarios where the full mechanism underlying the phenomenon is unknown, making direct identification of the query challenging. Hence, the approach focuses on bounding the target, learning experimental policies that improve the estimated bounds on the query rather than aiming for a single precise estimate of the unknown mechanism.

Sequential Design#

Sequential design in this context refers to the iterative process of designing experiments, where each experiment’s outcome informs the design of the subsequent one. This is particularly useful when dealing with complex systems, where the effects of experimental manipulations are not fully understood. The core idea is to adapt the experimental strategy based on previous data to efficiently narrow the uncertainty surrounding the target scientific query. This approach is advantageous as it avoids the exhaustive and potentially wasteful exploration of the entire experimental space. By iteratively refining the experiments, the method focuses resources on the most informative ones, thereby minimizing the total number of experiments required to achieve a desired level of certainty. The approach is especially valuable in scenarios with limited resources or high experimental costs, such as those involving expensive or time-consuming manipulations. This adaptive strategy contrasts with traditional fixed-design methods, where the entire set of experiments is planned in advance without incorporating the information from previously conducted ones. The adaptive nature of the design process allows for a more efficient and informative investigation of complex, multifaceted scientific problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

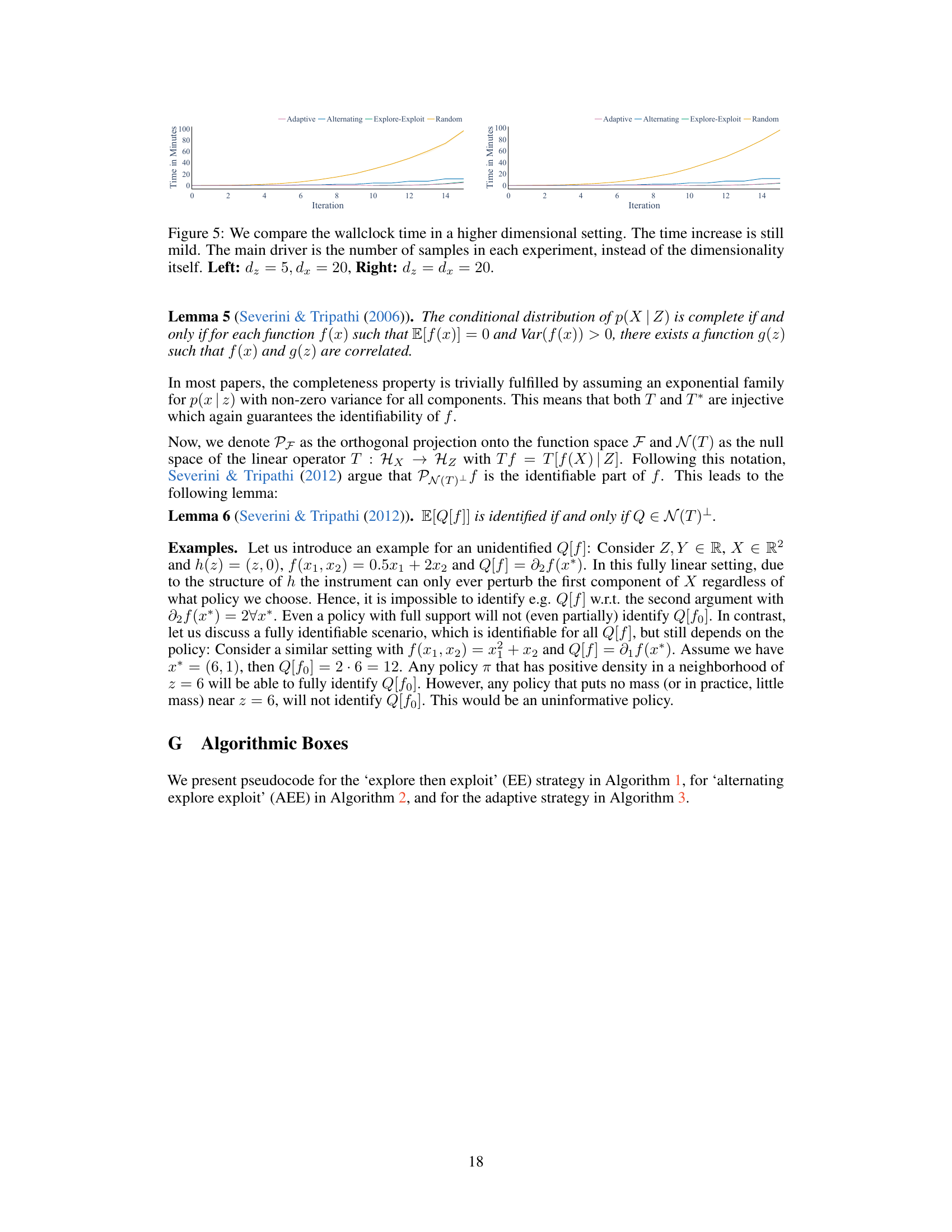

🔼 The figure compares different experimental design strategies for estimating a target query Q[f0] in a synthetic setting with multi-variate treatments and non-linear mechanisms. The top part shows the estimated upper and lower bounds of Q[f0] over time (iterations), while the bottom part shows the final bounds at the end of the experiment (T=16). The results illustrate the performance of various adaptive and non-adaptive strategies, highlighting the superior performance of the targeted adaptive strategy in accurately identifying Q[f0].

read the caption

Figure 1: We compare the different strategies in our synthetic setting. Left and right only differ in the range of the y-axis. The black constant line represents the true value of Q[fo]. Top: Estimated upper and lower bounds Q± over t ∈ [T] for nseeds = 50 and two different ‘zoom levels’ on the y-axis. Lines are means and shaded regions are (10, 90)-percentiles. Bottom: The final estimated bounds Q at T = 16. The dotted line is y = 0. Both locally guided heuristic (explore-then-exploit, alternating explore exploit) confidently bound the target query away from zero with a relatively narrow gap between them. Our targeted adaptive strategy is even better and essentially identifies the target query Q[fo] = 20 after T = 16 rounds.

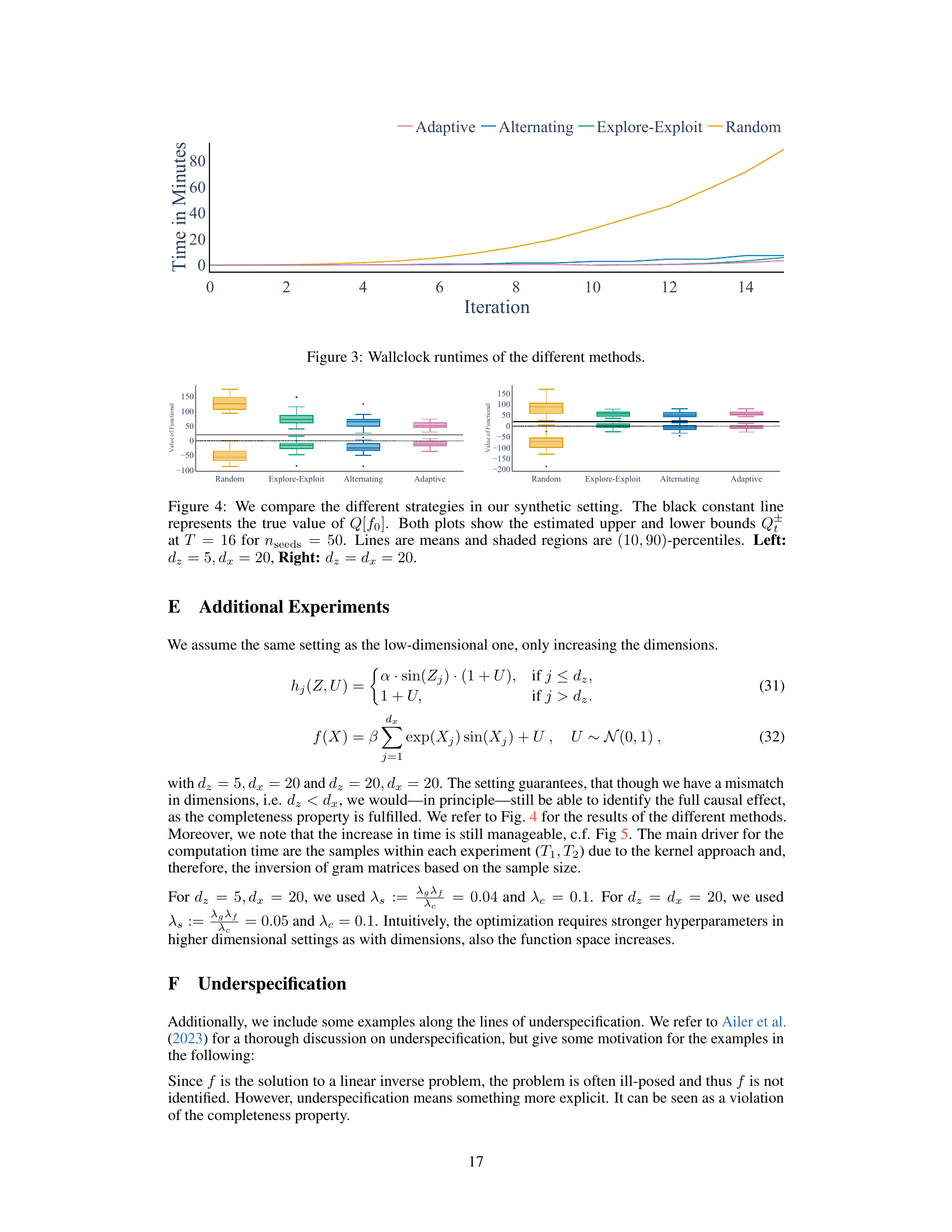

🔼 This figure compares the computation time of four different experiment selection strategies across iterations in a higher dimensional setting (d₂ = 5, dx = 20 and d₂ = dx = 20). The strategies are Adaptive, Alternating, Explore-Exploit, and Random. The plot shows that the time increase is relatively small even when increasing the dimensionality, suggesting that the computation time depends more strongly on the number of samples in each round than on the dimensionality itself.

read the caption

Figure 5: We compare the wallclock time in a higher dimensional setting. The time increase is still mild. The main driver is the number of samples in each experiment, instead of the dimensionality itself. Left: d₂ = 5, dx = 20, Right: dz = dx = 20.

🔼 The figure compares four different strategies for sequentially updating experimentation policies to learn about a scientific query. The strategies are: random, explore-then-exploit, alternating explore-exploit, and adaptive. The plot shows estimated upper and lower bounds on the query over time. The adaptive strategy outperforms the others and confidently bounds the query close to the true value.

read the caption

Figure 1: We compare the different strategies in our synthetic setting. Left and right only differ in the range of the y-axis. The black constant line represents the true value of Q[f0]. Top: Estimated upper and lower bounds Q± over t ∈ [T] for nseeds = 50 and two different ‘zoom levels’ on the y-axis. Lines are means and shaded regions are (10, 90)-percentiles. Bottom: The final estimated bounds Q at T = 16. The dotted line is y = 0. Both locally guided heuristic (explore-then-exploit, alternating explore exploit) confidently bound the target query away from zero with a relatively narrow gap between them. Our targeted adaptive strategy is even better and essentially identifies the target query Q[f0] = 20 after T = 16 rounds.

🔼 This figure compares four different strategies (Adaptive, Alternating, Explore-Exploit, and Random) for sequentially updating the experimentation policy to minimize the gap between upper and lower bounds of a target query Q[fo]. The top part shows the estimated upper and lower bounds over 16 iterations for each strategy, while the bottom part shows the final bounds at the end of the 16 iterations. The plot demonstrates that the adaptive strategy significantly outperforms the others in accurately estimating the target query value (20). The locally guided heuristic strategies (Explore-Exploit and Alternating) also perform well, providing relatively narrow confidence intervals around the true value.

read the caption

Figure 1: We compare the different strategies in our synthetic setting. Left and right only differ in the range of the y-axis. The black constant line represents the true value of Q[fo]. Top: Estimated upper and lower bounds Q± over t ∈ [T] for nseeds = 50 and two different ‘zoom levels’ on the y-axis. Lines are means and shaded regions are (10, 90)-percentiles. Bottom: The final estimated bounds Q at T = 16. The dotted line is y = 0. Both locally guided heuristic (explore-then-exploit, alternating explore exploit) confidently bound the target query away from zero with a relatively narrow gap between them. Our targeted adaptive strategy is even better and essentially identifies the target query Q[fo] = 20 after T = 16 rounds.

Full paper#