↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models use high-dimensional parameters that are difficult to interpret, hindering explainability. This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on the interpretability of parameters within various models such as clustering, time-series, and classification. The challenge lies in the difficulty of interpreting high-dimensional and often uninterpretable model parameters. Current methods often fail to provide meaningful explanations of the underlying data patterns.

The researchers propose a novel framework that uses natural language predicates to parameterize these models. This approach allows for the optimization of continuous relaxations of predicate parameters and subsequent discretization using language models. The resulting framework is highly versatile, easily adaptable to various data types (text and images) and model types, offering improved interpretability and effectiveness. The efficacy is demonstrated across multiple datasets and tasks showing improved performance compared to existing methods for text clustering.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers seeking to enhance model interpretability and create explainable AI. It introduces a novel, versatile framework that bridges the gap between statistical modeling and natural language processing, opening avenues for improved model understanding and more effective dataset analysis across diverse domains. This work directly addresses current trends in explainable AI by providing a generalizable method applicable to various model types. Its practical demonstration and open-ended applications offer substantial value to researchers and practitioners aiming to build more trustworthy and interpretable AI systems.

Visual Insights#

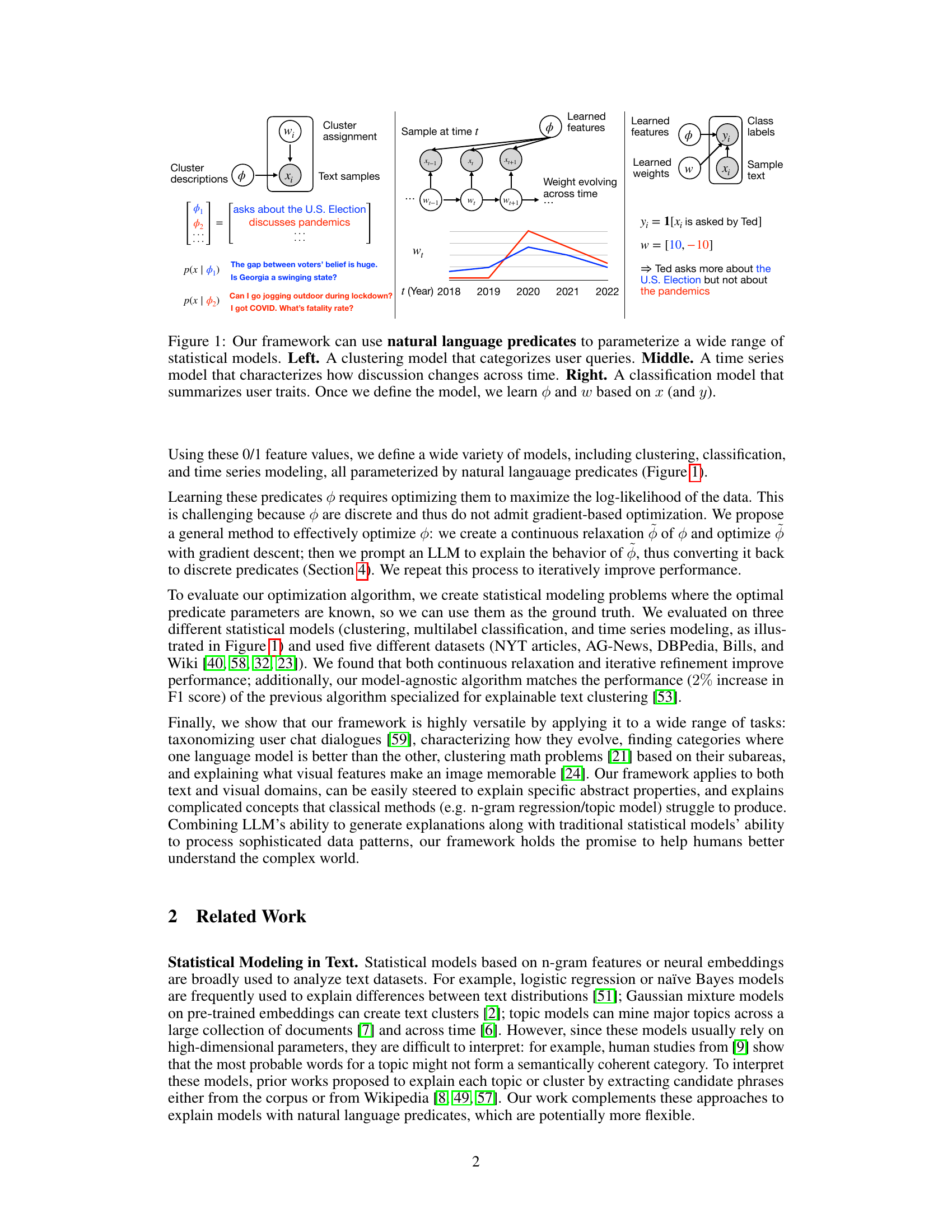

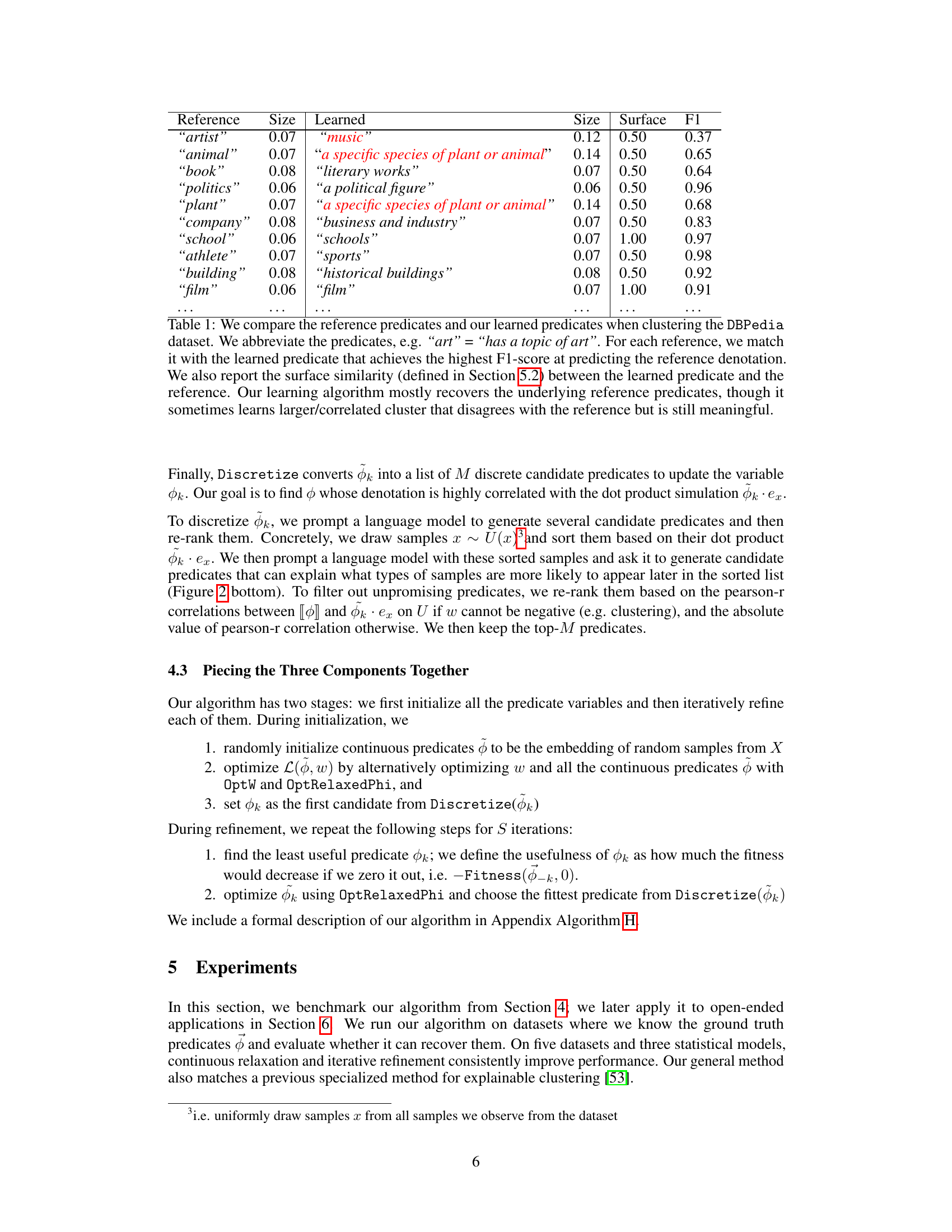

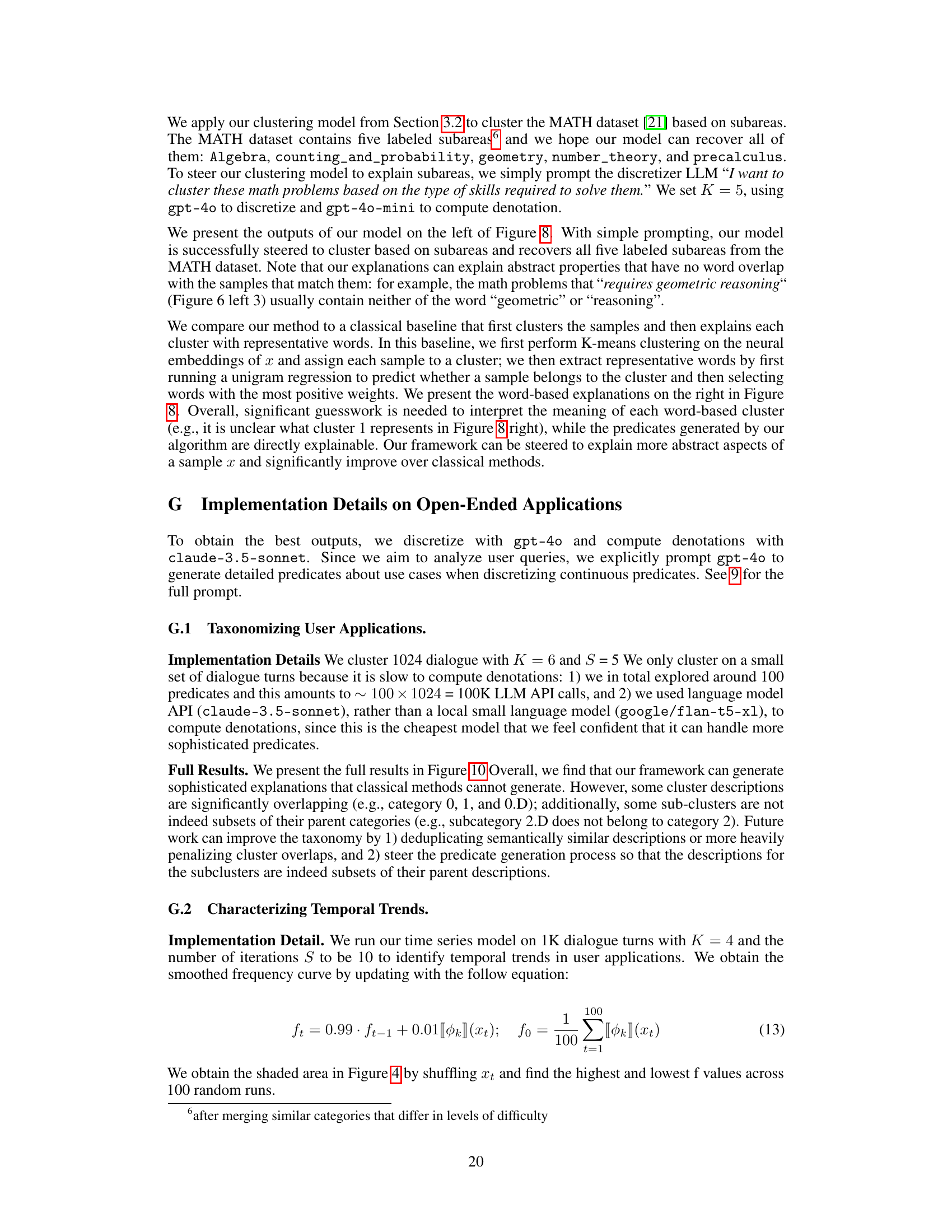

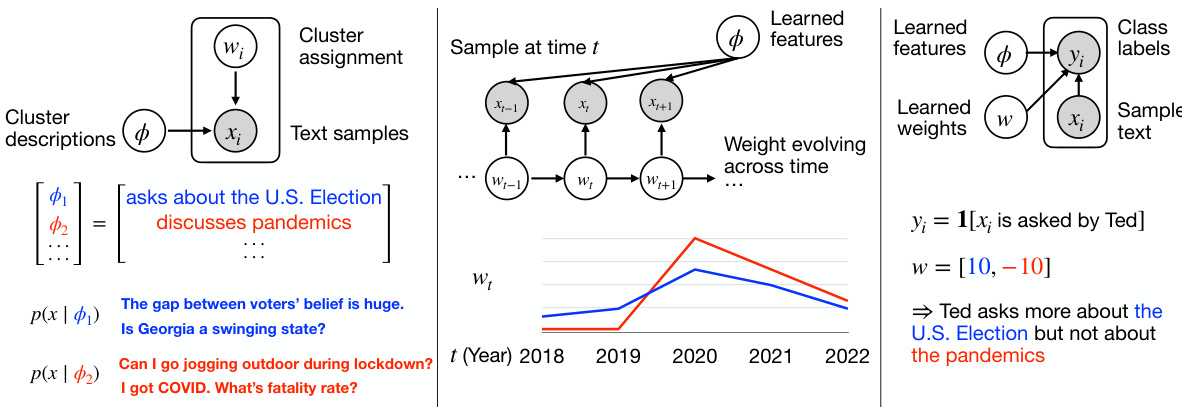

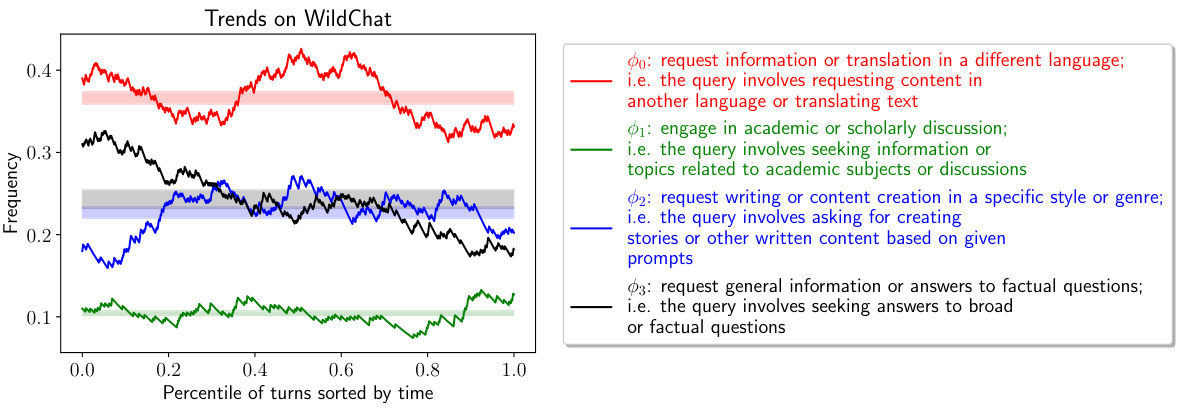

This figure illustrates the versatility of the proposed framework in parameterizing various statistical models using natural language predicates. It showcases three examples: a clustering model that groups user queries based on shared characteristics described by predicates; a time series model tracking changes in discussion topics over time, again using predicates to characterize the topics; and a classification model identifying user traits based on their query patterns and associated predicates. The models learn weights (w) and predicate features (ϕ) to maximize the likelihood of the data.

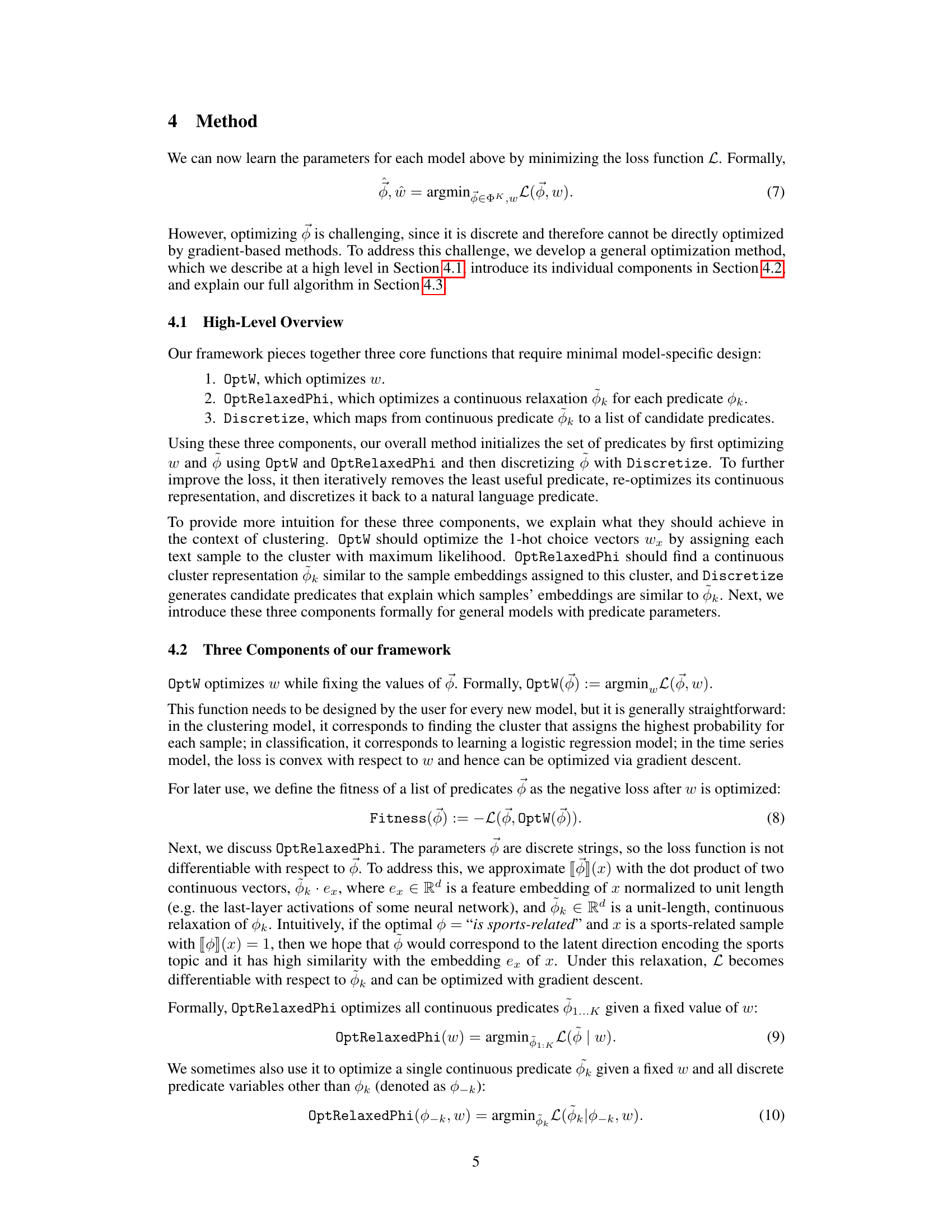

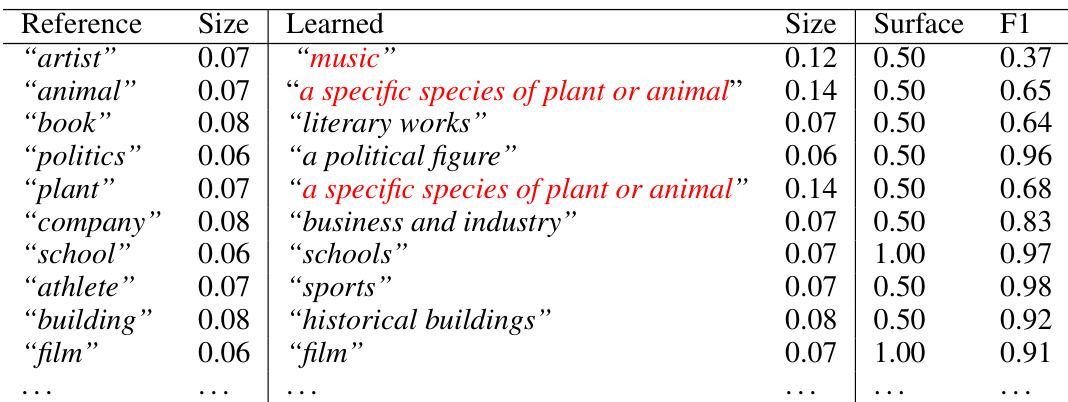

This table compares the reference predicates (ground truth) against the predicates learned by the model when clustering the DBPedia dataset. For each reference predicate, the table shows the learned predicate with the highest F1 score (a measure of predictive accuracy) and the surface similarity (a measure of string similarity) between the reference and the learned predicate. The results show that the model largely recovers the intended predicates, although some learned predicates represent broader, related concepts than the original references.

In-depth insights#

Predicate-Based Models#

Predicate-based models represent a novel approach to statistical modeling by parameterizing model components using natural language predicates. This allows for a direct and intuitive mapping between model parameters and human-understandable concepts, which significantly enhances interpretability. The core idea is to leverage the inherent semantic richness of natural language to represent complex relationships within the data, instead of relying solely on numerical representations. This methodology offers several advantages: improved explainability, easier model debugging, and potentially greater generalizability, as the models learn to capture abstract concepts rather than just surface-level correlations. However, predicate-based models also introduce certain challenges. Learning these models requires sophisticated optimization techniques, as predicates are discrete and do not lend themselves readily to gradient-based methods. Furthermore, the effectiveness relies heavily on the capabilities and limitations of the underlying natural language processing model used to interpret and generate predicates. Careful consideration must be given to potential biases inherent in the language model and strategies are needed to mitigate the risks of inheriting these biases into the statistical model. Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of predicate-based models in terms of transparency, understandability, and ultimately trust in machine learning applications, warrant further exploration and development.

LLM-Driven Optimization#

LLM-driven optimization presents a paradigm shift in how we approach complex optimization problems. Instead of relying solely on traditional gradient-based methods, this approach leverages the power of large language models (LLMs) to guide the optimization process. The core idea is to use LLMs to generate or refine candidate solutions, potentially incorporating domain-specific knowledge or heuristics that may be difficult to encode algorithmically. This is especially beneficial for problems with discrete search spaces or those involving complex, high-dimensional data. However, several key challenges arise. LLM’s outputs are inherently stochastic, requiring careful consideration of reliability and consistency. Computational cost is another significant concern as LLMs can be computationally expensive, particularly in iterative optimization schemes. Furthermore, the ‘black box’ nature of LLMs can pose challenges for understanding and debugging the optimization process, demanding methods to analyze and interpret the reasoning behind LLM-generated suggestions. Despite these challenges, the potential advantages of combining LLMs with optimization techniques are substantial, offering the potential for significant improvements in efficiency and solution quality for certain classes of problems. Further research should focus on mitigating the limitations and exploring the synergy between LLM capabilities and established optimization algorithms.

Versatile Framework#

The concept of a “Versatile Framework” in a research paper usually points towards a method or system designed for broad applicability and adaptability. This framework likely demonstrates its versatility by successfully tackling a diverse range of tasks or problems, showcasing its flexibility and robustness across different domains or model types. Its strength may lie in its model-agnostic nature, meaning it isn’t limited to specific statistical methods, but can be easily adapted to various models like clustering, classification, and time-series analysis. Such adaptability is frequently highlighted by showing successful application across multiple datasets spanning text, images, or other data modalities. The framework’s versatility is further strengthened by its capacity to explain complex and abstract concepts that traditional methods struggle with, often relying on the interpretability of natural language parameters. Therefore, the “Versatile Framework” isn’t just about broad applicability, but also about providing valuable insights and explanations from data through clear, understandable representations. The ability to easily steer or customize the framework to focus on specific properties (e.g., subareas within a problem domain) further enhances its usefulness and demonstrates its practical value for diverse research areas.

Empirical Evaluation#

A robust empirical evaluation section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should present a comprehensive and methodical approach to assessing the proposed method’s performance. This would involve a clear description of the datasets used, including their characteristics and size, followed by a detailed explanation of the metrics employed to evaluate performance. The choice of metrics should be justified, aligning with the goals of the method and the nature of the problem being addressed. Furthermore, a thorough comparison with established baselines or competing methods is essential, allowing for a fair assessment of the method’s novelty and contribution. The results should be reported clearly and concisely, often using tables and figures to visually represent the findings. Crucially, statistical significance testing should be conducted to ensure the observed results are not due to random chance. The discussion of results should highlight both successes and limitations, providing a balanced and nuanced interpretation of the findings. Overall, a strong empirical evaluation section enhances the credibility and impact of research findings.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving computational efficiency is crucial, as the current reliance on LLMs for denotation creates a bottleneck. Exploring more efficient methods, perhaps leveraging smaller, specialized models or techniques like prompt engineering, would significantly enhance scalability. Furthermore, developing more robust methods for handling ambiguous predicates and avoiding redundant explanations is essential to enhance the interpretability and usability of the framework. Investigating alternative methods for continuous relaxation and predicate discretization, beyond the current LLM-based approaches, could potentially unlock new avenues for optimization and improved accuracy. Finally, expanding the applications of the framework to a broader range of domains and tasks, particularly those involving complex, multi-modal data, will be vital in demonstrating its true potential and versatility. Addressing these challenges will pave the way for more widespread adoption and impact of the proposed methodology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

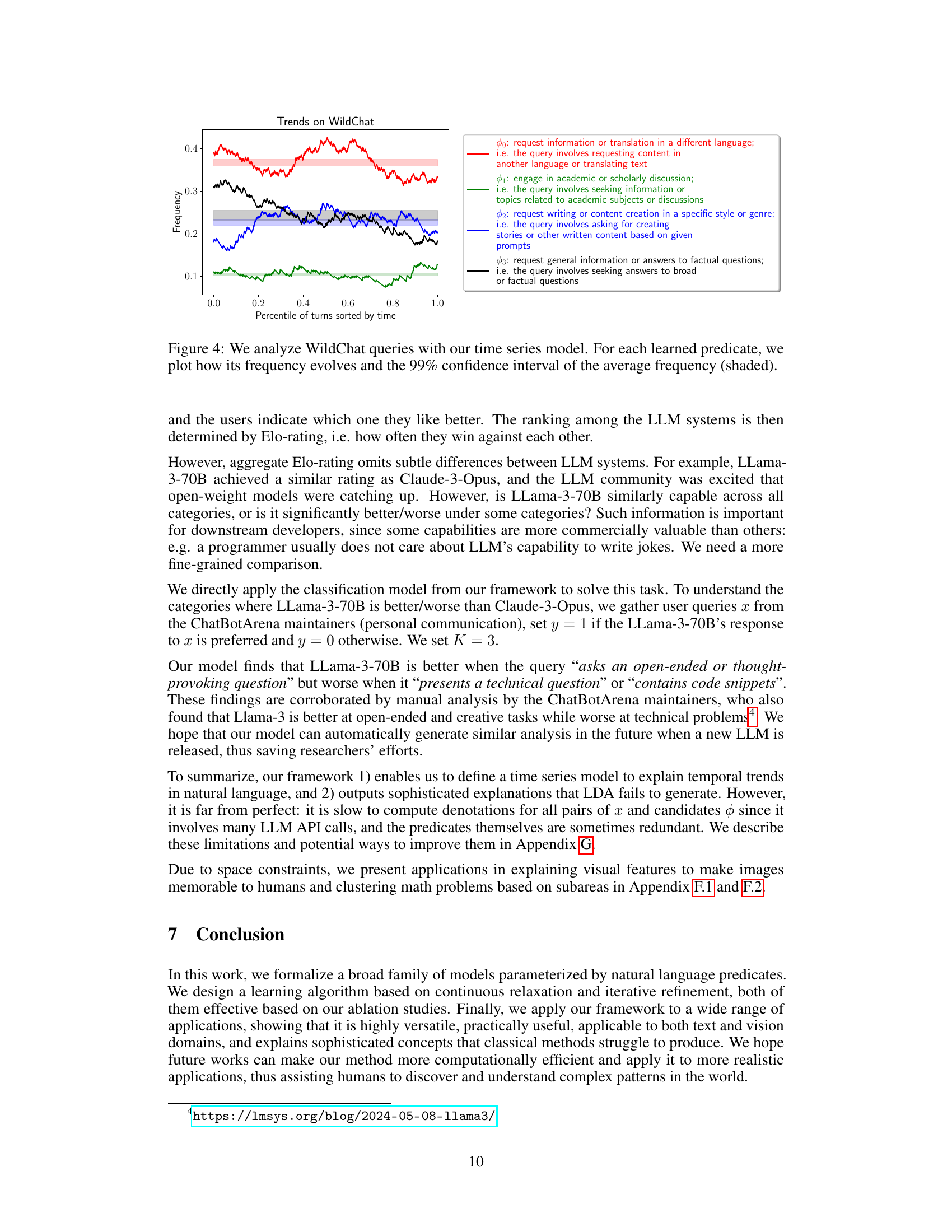

This figure illustrates the versatility of the proposed framework by showcasing three different statistical models (clustering, time series, and classification) all parameterized by natural language predicates. The left panel depicts a clustering model categorizing user queries; the middle panel shows a time series model tracking changes in discussion over time; and the right panel presents a classification model summarizing user traits. The framework learns model parameters (θ and w) based on input data (x) and, optionally, labels (y).

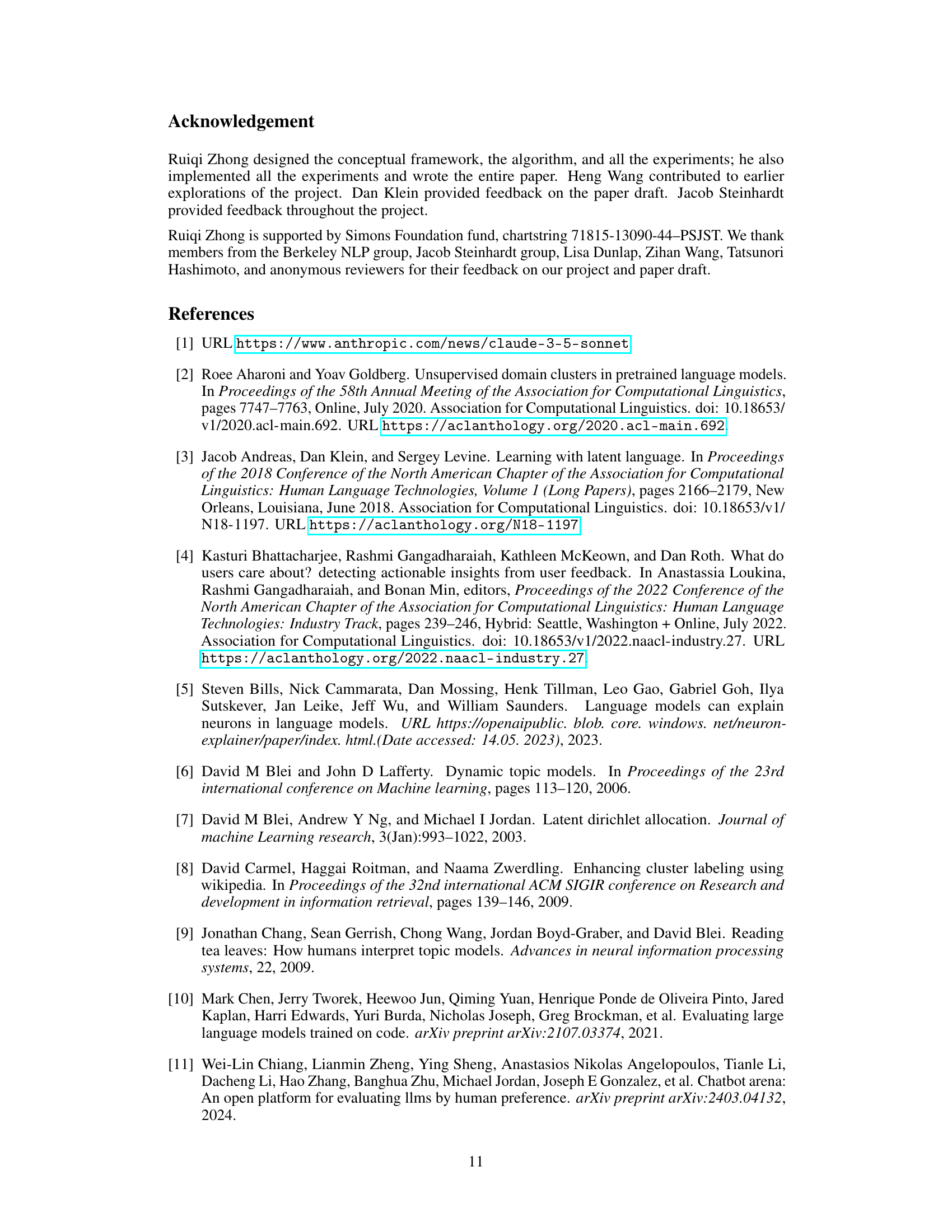

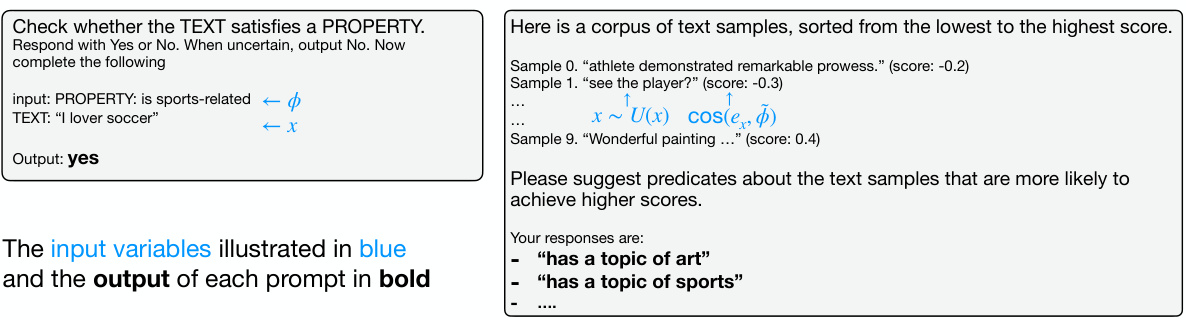

This figure visualizes the trends of different types of user queries on the WildChat dataset over time using a time series model. Each line represents a learned predicate (category of user queries) identified by the model, showing how the frequency of each query type changes across the dataset’s timeline. The shaded area around each line indicates the 99% confidence interval of the average frequency, providing a measure of uncertainty. This helps to visualize the evolution of user query patterns and identify significant trends in the use of the language model over time.

This figure illustrates the versatility of the proposed framework by showcasing its application to three different types of statistical models: clustering, time series, and classification. Each model is parameterized using natural language predicates, which are inherently interpretable. The left panel shows a clustering model that groups user queries based on their content. The middle panel depicts a time series model that tracks changes in discussion topics over time. The right panel demonstrates a classification model that categorizes users based on their traits. The framework learns the model parameters (Φ and w) by maximizing the likelihood of the observed data.

This figure illustrates the versatility of the proposed framework by showcasing three different statistical models parameterized using natural language predicates: clustering, time series, and classification. The left panel depicts a clustering model that groups user queries based on their shared characteristics represented by learned predicates. The middle panel shows a time series model tracking changes in discussion topics over time, again using predicates to define the topic categories. The right panel illustrates a classification model using predicates to classify users based on their properties. The figure highlights how the framework adapts to various modeling tasks by integrating natural language predicates for intuitive parameter interpretation.

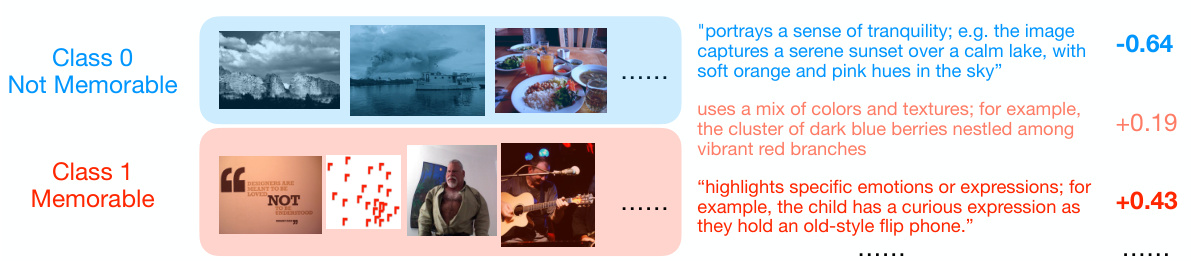

This figure shows the results of applying a classification model to a dataset of images to determine which visual features contribute to an image’s memorability. The model uses natural language predicates to represent these features. The results show that tranquil scenes are associated with lower memorability scores, whereas images highlighting emotions or expressions tend to be rated as more memorable.

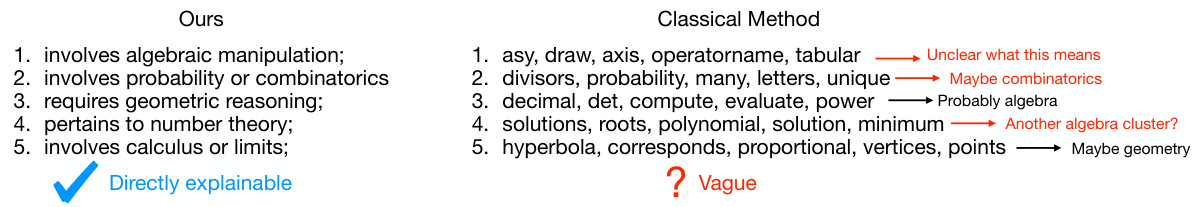

This figure compares the results of clustering math problems using the proposed method and a classical K-means clustering approach followed by unigram analysis for explanation. The proposed method, shown on the left, directly generates natural language predicates (descriptions) that accurately reflect the type of mathematical knowledge required to solve problems within each cluster. In contrast, the classical method, shown on the right, produces clusters that are difficult to interpret and require significant effort to understand what kind of problem each cluster represents. The figure visually demonstrates the superior interpretability of the proposed method.

More on tables

This table compares the reference predicates (ground truth) with the predicates learned by the model when clustering the DBPedia dataset. The learned predicates are abbreviated, with the full meaning provided in the caption. For each reference predicate, the table shows the learned predicate with the highest F1-score (the model’s accuracy in predicting whether the reference predicate is true), the size of the reference cluster, the size of the cluster produced by the learned predicate, and a surface similarity score between the reference and learned predicates. The results show that the model largely recovers the reference predicates but occasionally creates larger, related clusters that differ slightly from the references.

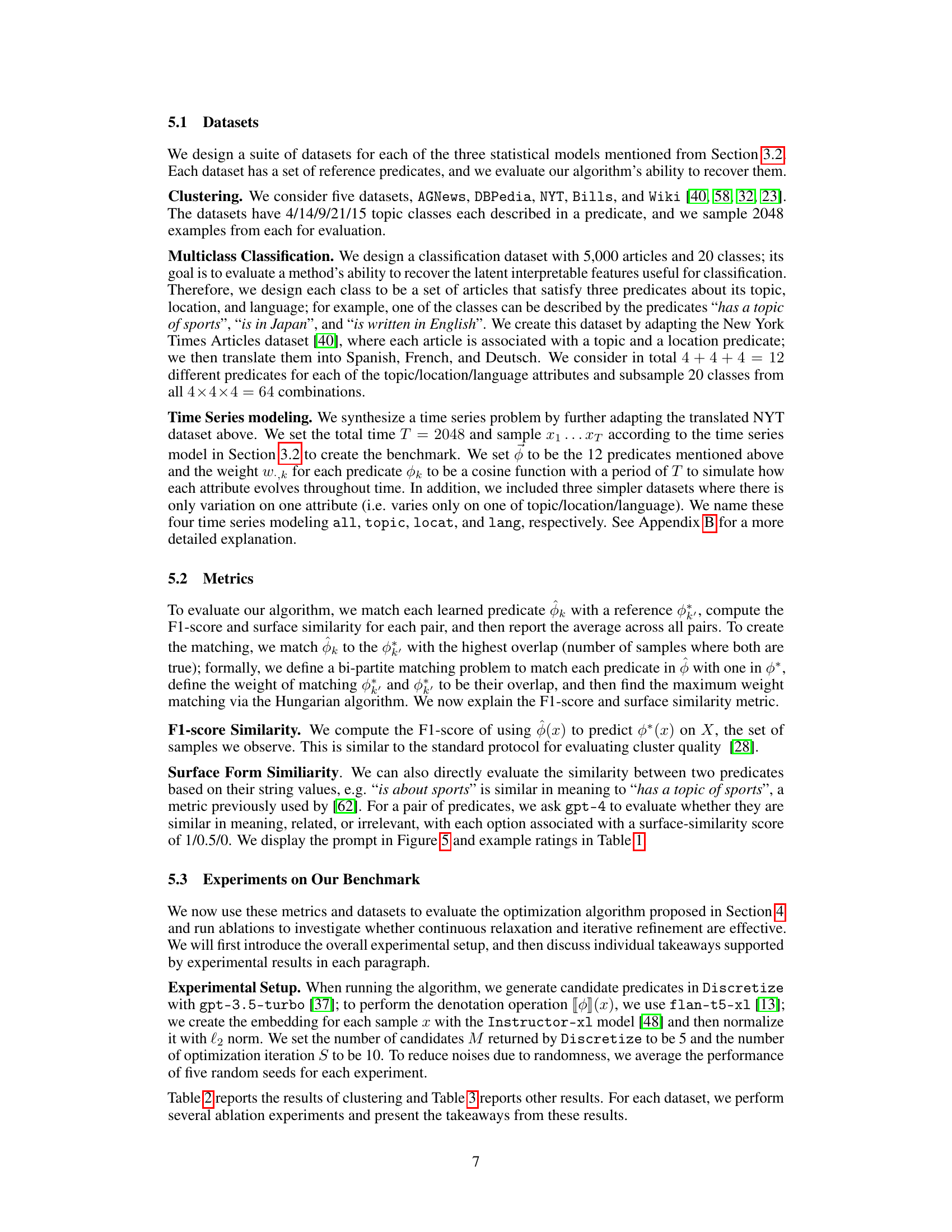

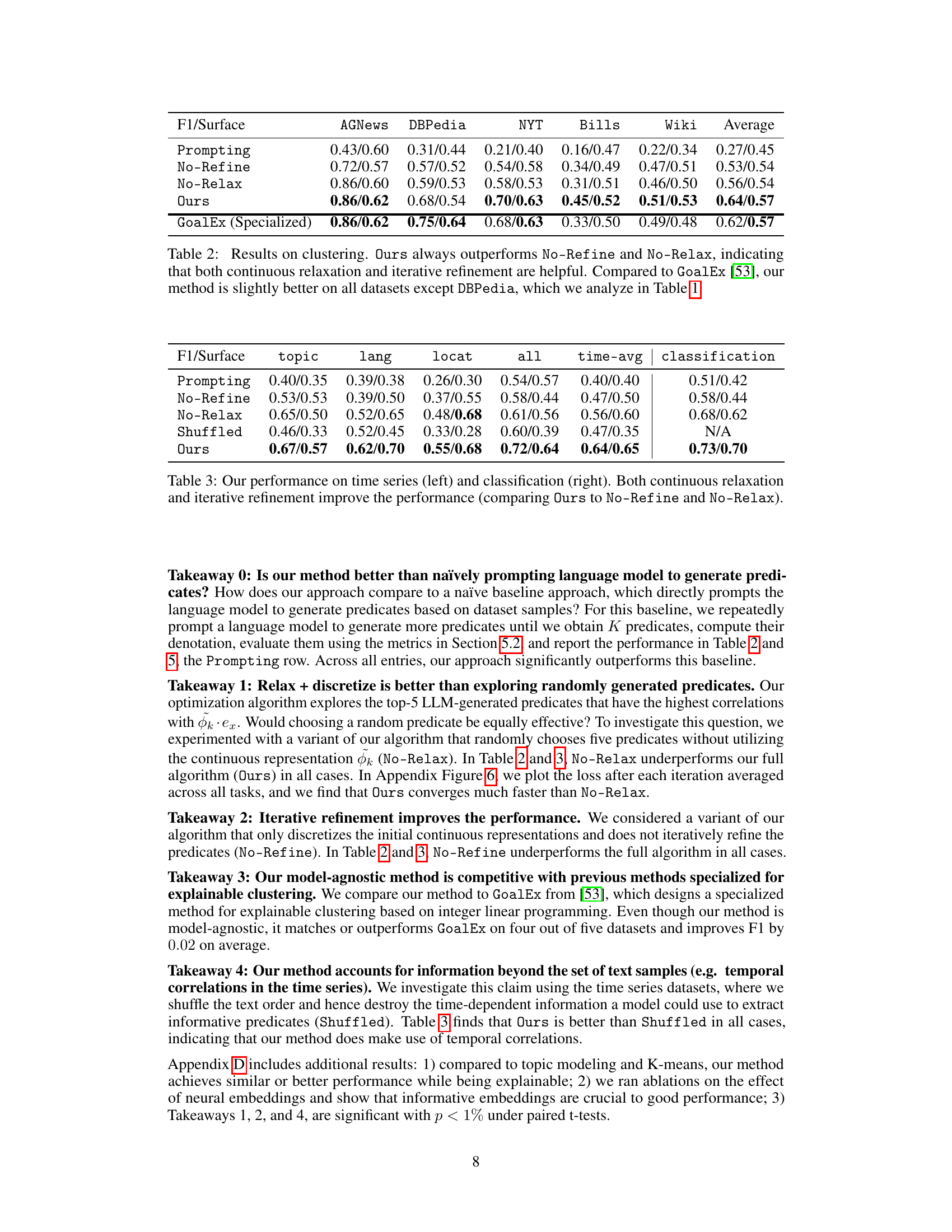

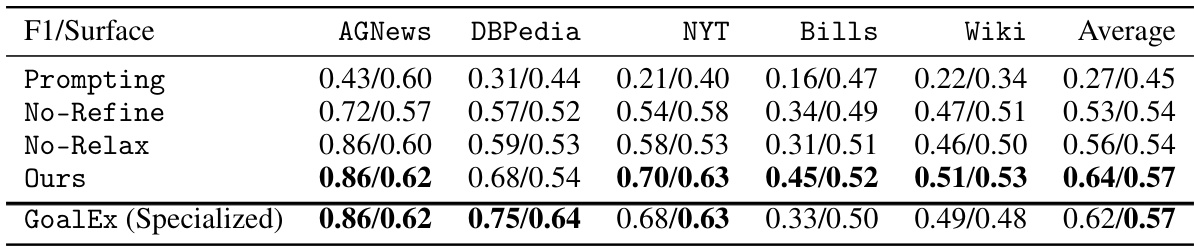

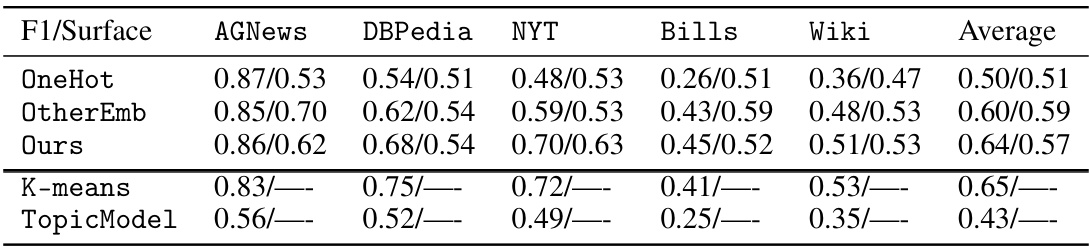

This table presents the results of clustering experiments using different methods: Ours, No-Refine, No-Relax, and GoalEx (a specialized method). The performance is measured by the F1-score and surface similarity. The results demonstrate that the proposed method (Ours) significantly outperforms the baselines (No-Refine and No-Relax) and is comparable to the specialized GoalEx method, highlighting the effectiveness of both continuous relaxation and iterative refinement. A detailed analysis of the DBPedia dataset results is further provided in Table 1.

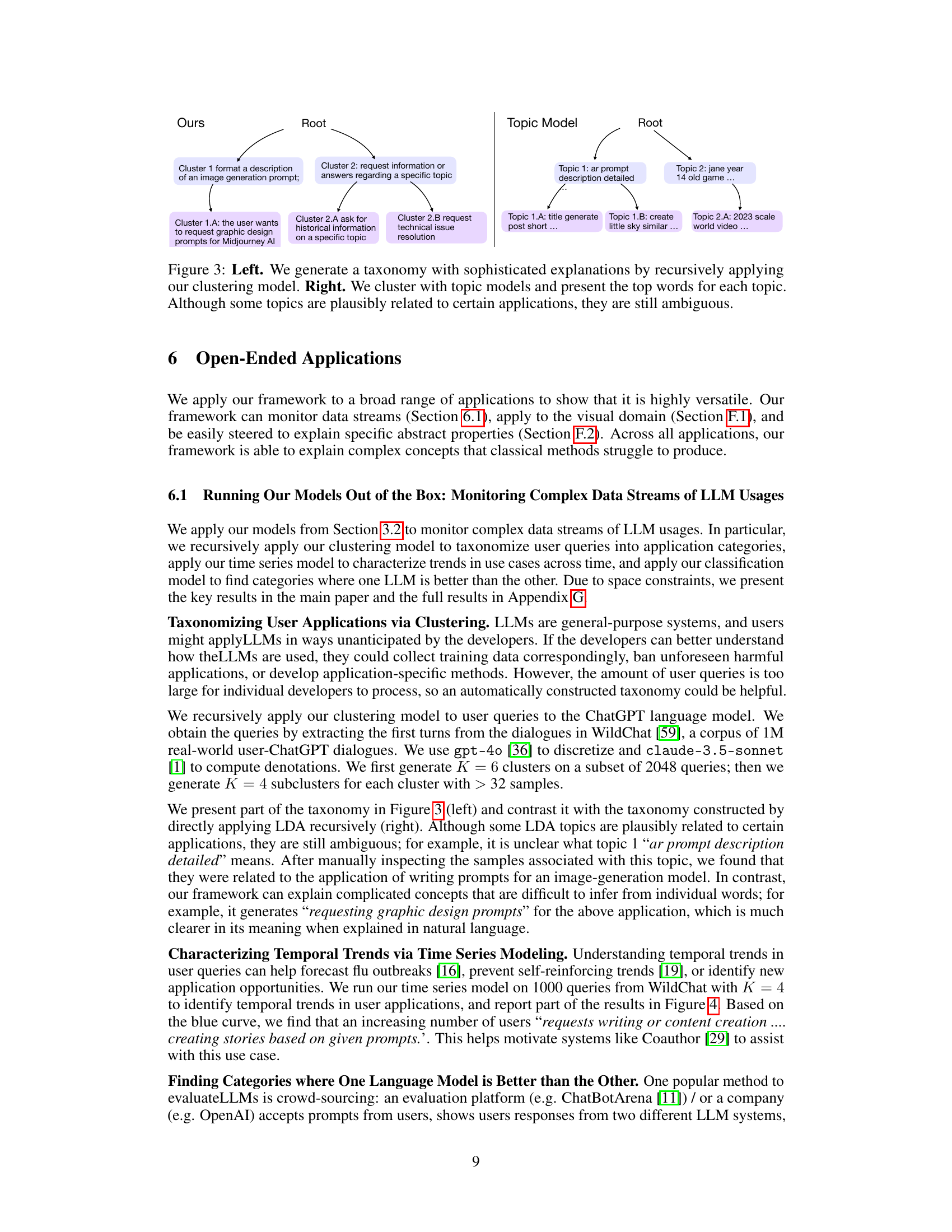

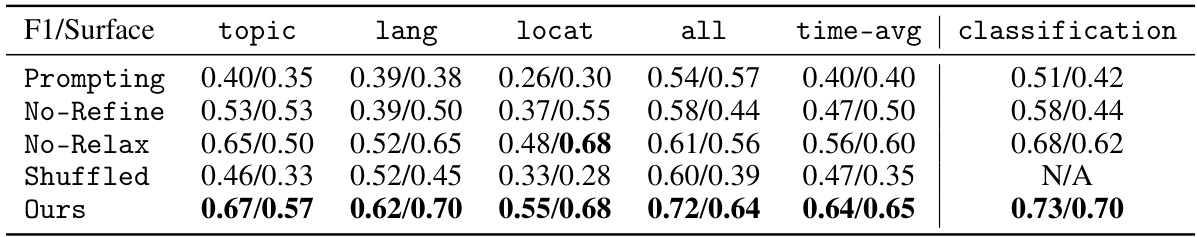

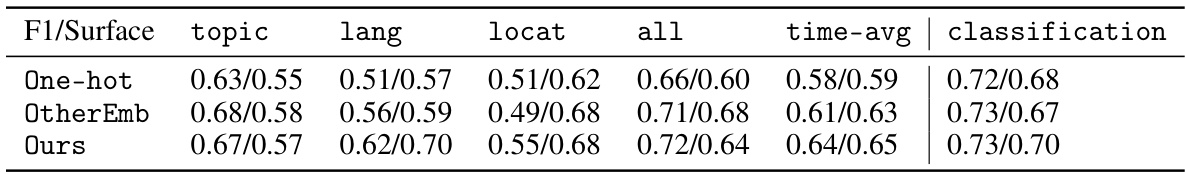

This table presents the performance of the proposed method (Ours) compared to ablative variants: No-Refine (without iterative refinement) and No-Relax (without continuous relaxation). It evaluates performance across four time series datasets (topic, lang, locat, all) and a classification task, using F1-score and surface similarity as metrics. The results show consistent improvement with both continuous relaxation and iterative refinement.

This table presents the results of clustering experiments using three different methods: the proposed method (‘Ours’), a method without iterative refinement (‘No-Refine’), and a method without continuous relaxation (‘No-Relax’). The performance is measured using F1-score and surface similarity on five datasets (AGNews, DBPedia, NYT, Bills, Wiki). The results demonstrate that both continuous relaxation and iterative refinement improve performance. A comparison with a specialized explainable clustering method (GoalEx) shows that the proposed method achieves comparable or slightly better performance across most datasets.

This table presents the results of experiments on time series and multiclass classification tasks. It compares the performance of three different approaches: (1) a baseline using only prompting; (2) a variant using continuous relaxation but without iterative refinement; and (3) the proposed approach combining both. The results show that using both continuous relaxation and iterative refinement leads to significant performance gains, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed optimization algorithm. The table also includes results for various subtasks within the time-series modeling (topic, lang, locat) to illustrate the versatility of the model.

Full paper#