↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world scenarios involve evaluating the impact of policies where the effect is not uniquely identifiable due to unobserved confounding. This makes it difficult to accurately assess a policy’s effectiveness. Existing methods often rely on strong assumptions that may not hold in practice.

This research introduces a novel framework to address this challenge. The authors developed tighter analytical bounds for general probabilistic and conditional policies, improving upon previous methods. They also created a robust estimation framework based on double machine learning, suitable for high-dimensional datasets and continuous variables. Simulations and real-world examples demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on causal inference and policy evaluation, particularly in scenarios with unobserved confounding. It offers a novel framework for bounding the effects of policies even when precise identification is impossible, thus advancing our ability to draw meaningful conclusions from complex, real-world data.

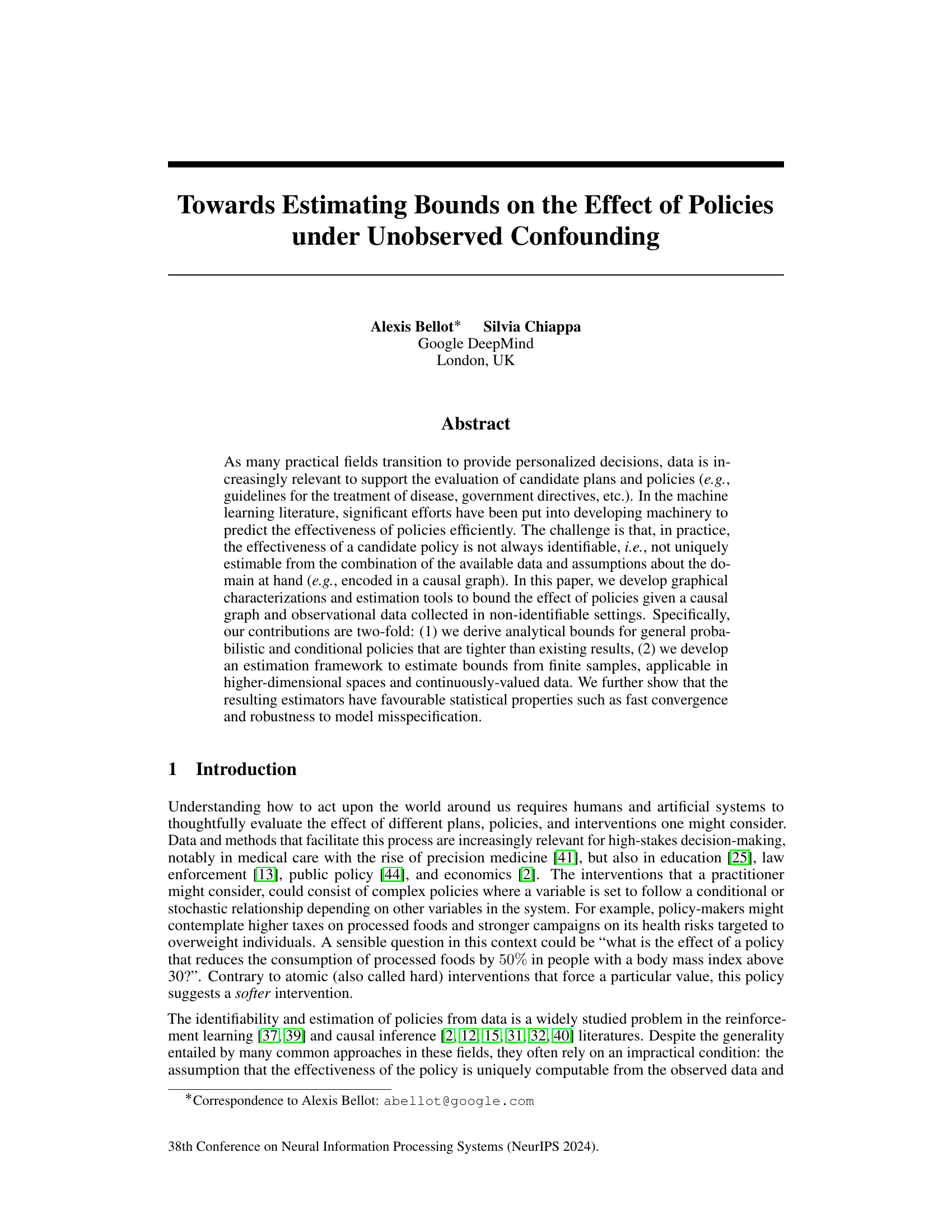

Visual Insights#

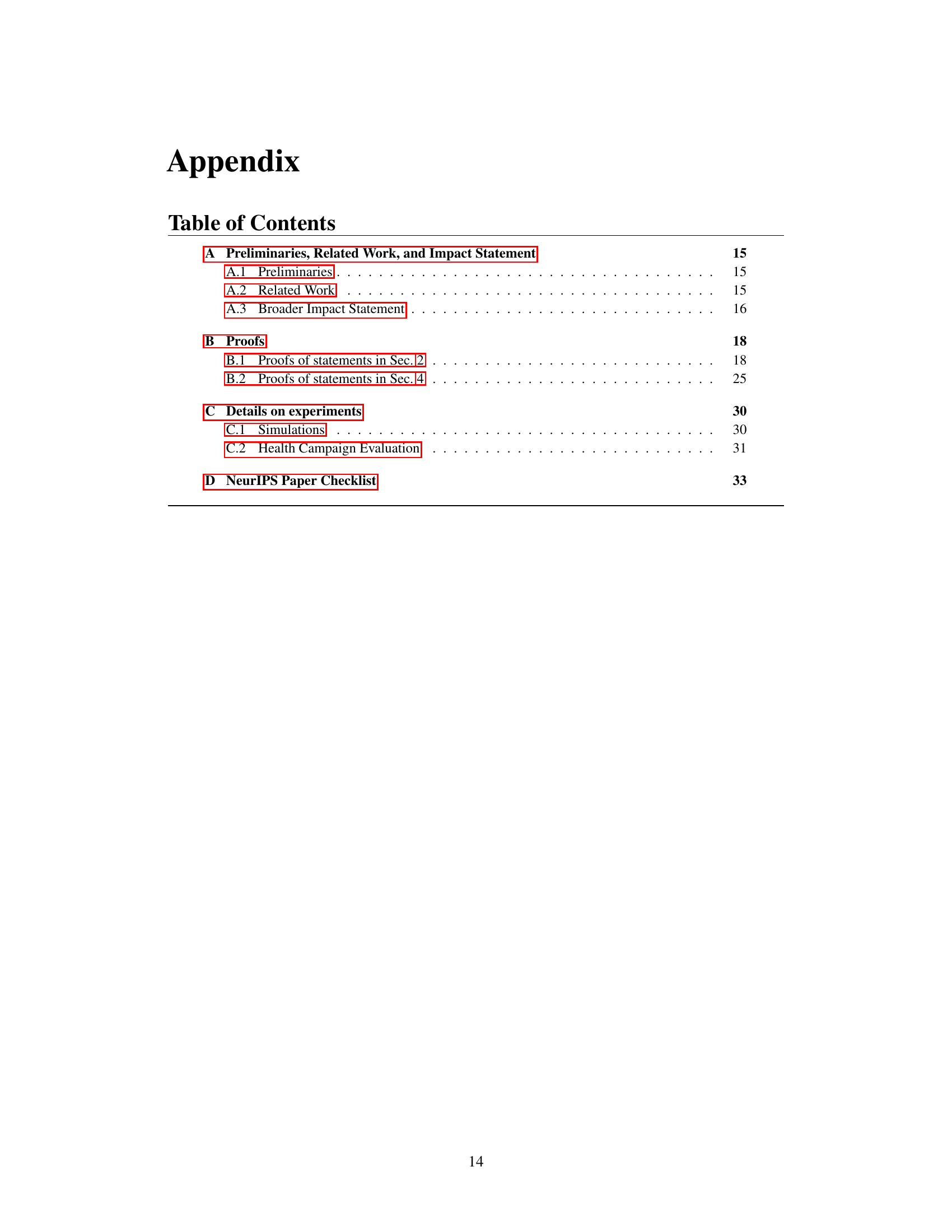

This figure shows four different causal diagrams used as examples in sections 2 and 3 of the paper. Each diagram represents a different causal relationship between variables, demonstrating various scenarios such as the effects of stochastic interventions, conditional interventions, and confounding variables. These examples illustrate the concepts and methods explained in the paper regarding the partial identification and estimation of policy effects under unobserved confounding.

In-depth insights#

Policy Bounding#

Policy bounding, in the context of causal inference and policy evaluation, focuses on determining the limits of a policy’s impact when dealing with unobserved confounding. Instead of aiming for precise effect estimation, which is often impossible due to hidden variables, policy bounding seeks to establish an interval within which the true effect likely lies. This approach acknowledges the inherent uncertainty in real-world settings and provides a more robust and reliable way to assess a policy’s potential effectiveness. The methodology often leverages graphical causal models to identify conditional independencies and derive tighter bounds, going beyond simpler, less informative natural bounds. Advanced techniques might involve leveraging instrumental variables or adjustment sets to further refine these bounds. The challenge lies in both deriving these informative bounds and developing efficient and consistent estimators from finite sample data, a task often tackled using techniques like double machine learning. Ultimately, policy bounding offers a valuable tool for decision-making in scenarios where precise causal effect identification is infeasible, providing a more cautious and realistic assessment of policy interventions.

Causal Diagrams#

Causal diagrams are graphical representations of causal relationships between variables. They are powerful tools for reasoning about interventions and counterfactuals, which are crucial for causal inference. In a causal diagram, nodes represent variables, and directed edges represent causal effects. The absence of an edge implies the absence of a direct causal relationship, but not necessarily the lack of an indirect effect mediated by other variables. Confounding is represented by common causes of two variables, where an unobserved common cause leads to non-identifiability. Causal diagrams are used to identify conditions under which causal effects can be estimated (identifiability) and help in designing experiments or selecting appropriate statistical methods for estimating those effects. Key features of causal diagrams are d-separation (conditional independence based on graph structure) and the ability to represent interventional effects by modifying the graph structure. They provide a framework for evaluating policies by visually representing how different interventions influence outcomes, allowing researchers to anticipate and account for potential confounding factors that may affect the interpretation and validity of their results.

DML Estimation#

The concept of “DML Estimation,” likely referring to Double Machine Learning estimation, is crucial for addressing the challenges of policy effect estimation under unobserved confounding. DML’s strength lies in its ability to handle high-dimensional data and complex causal structures, providing robust and efficient estimators even with noisy or misspecified nuisance parameters. By leveraging two separate machine learning models for estimating nuisance functions—propensity score and outcome regression—DML mitigates the bias introduced by unobserved confounders, yielding more reliable policy effect estimates. The method’s double robustness property ensures that even if one of the nuisance models is misspecified, consistent estimates can still be obtained. The proposed DML framework within the context of the paper likely offers a practical solution for deriving bounds of policy effects in non-identifiable settings, overcoming the limitations of traditional causal inference methods that rely on strong identifying assumptions. This enables effective decision-making in complex scenarios by providing a quantitative and principled approach to policy evaluation.

Robustness Checks#

A Robustness Checks section in a research paper would systematically investigate the sensitivity of the study’s findings to alternative modeling assumptions, data variations, and methodological choices. It aims to demonstrate the reliability and generalizability of the results beyond the specific conditions of the main analysis. Key aspects would include exploring the impact of different model specifications (e.g., using alternative regression techniques or causal inference methods), assessing the robustness to outliers or missing data using various imputation or trimming techniques, and evaluating the consistency of findings across different subsets of the data. Sensitivity analyses, examining the impact of changes to key assumptions (e.g., unconfoundedness or model linearity), are also crucial to determine how deviations from those assumptions affect conclusions. The ultimate goal is to build confidence in the reported results by showing that they are not overly dependent on specific methodological choices or data peculiarities, strengthening the overall validity and credibility of the research.

Health Campaigns#

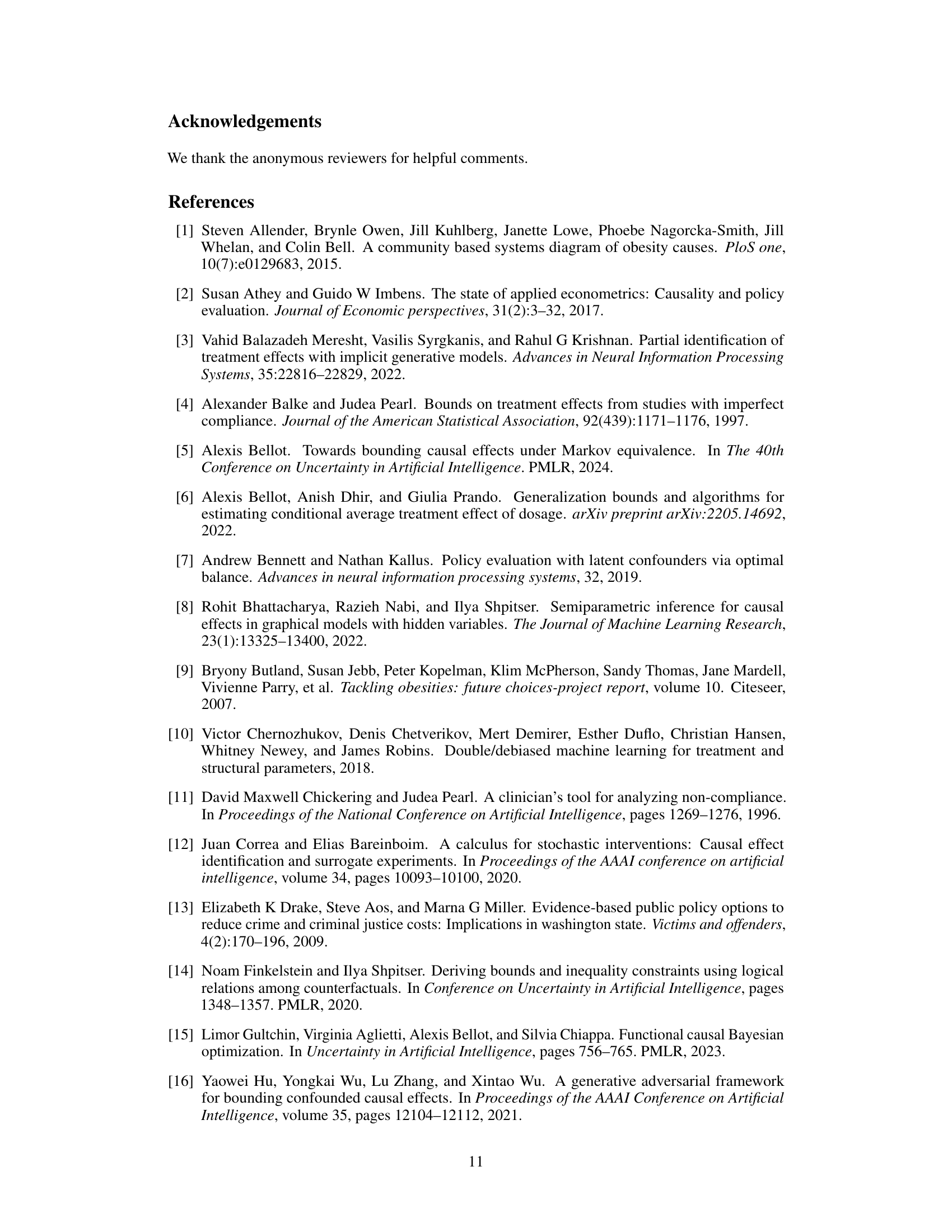

The section on Health Campaigns showcases a practical application of the paper’s methodology. It uses data from a real-world health initiative targeting obesity in Colombia, Peru, and Mexico. The analysis focuses on evaluating the impact of a multifaceted campaign promoting reduced consumption of high-calorie foods and increased exercise. The campaign is modeled as a stochastic policy, reflecting its probabilistic nature in influencing lifestyle changes. The researchers leverage causal diagrams to better understand the complex interplay of factors affecting obesity. This is particularly valuable as the effect of the campaign is likely non-identifiable due to the presence of unobserved confounders. By applying the developed bounding techniques, the study provides estimates of the campaign’s effect, acknowledging the inherent uncertainty. The inclusion of real-world data significantly enhances the paper’s contribution, demonstrating the practical implications of the theoretical framework. The results highlight the usefulness of the developed methods for policy evaluation in settings where traditional causal inference might not be feasible due to the non-identifiability of effects. The specific bounds calculated help quantify the campaign’s expected impact on obesity levels, showcasing the value of a bounded approach to inform decision-making.

More visual insights#

More on figures

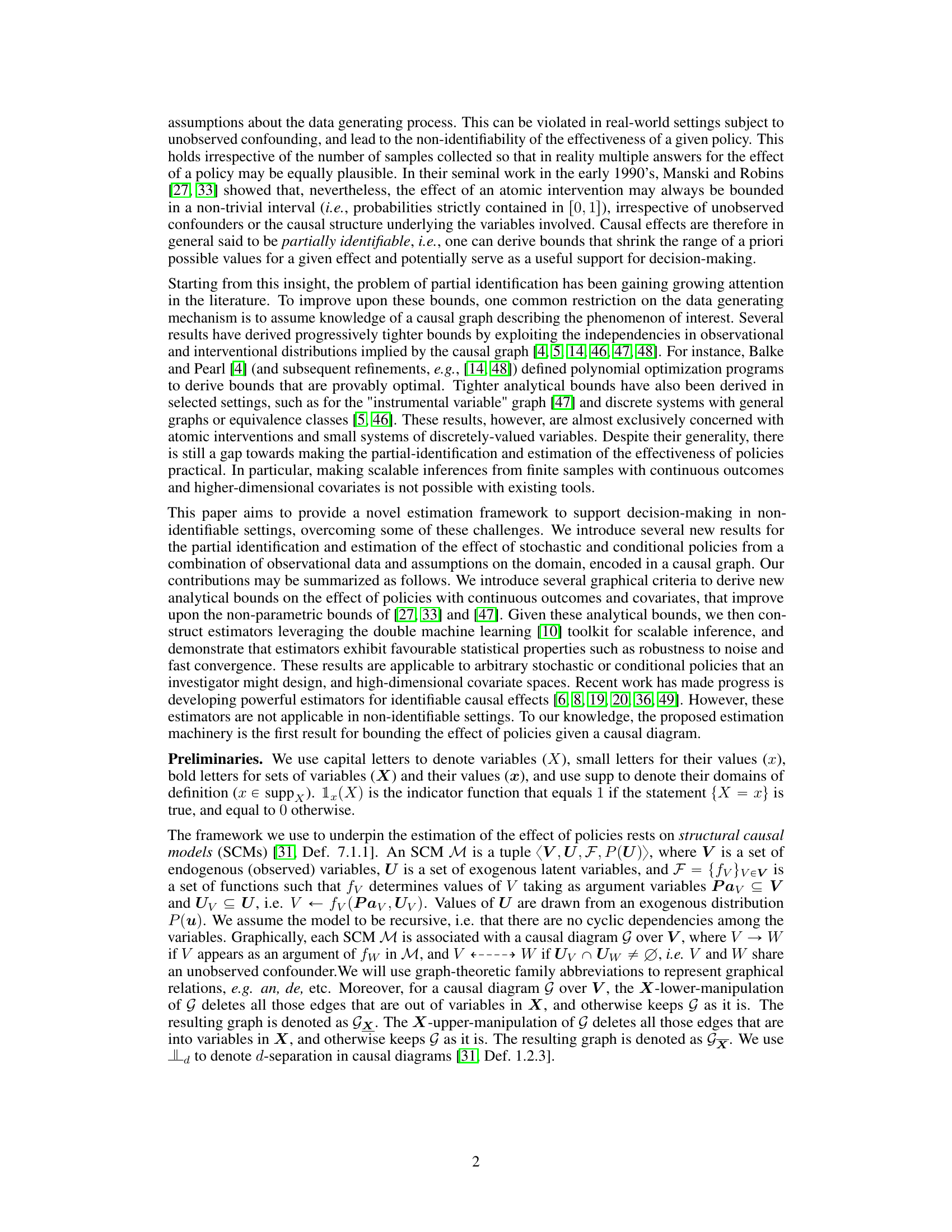

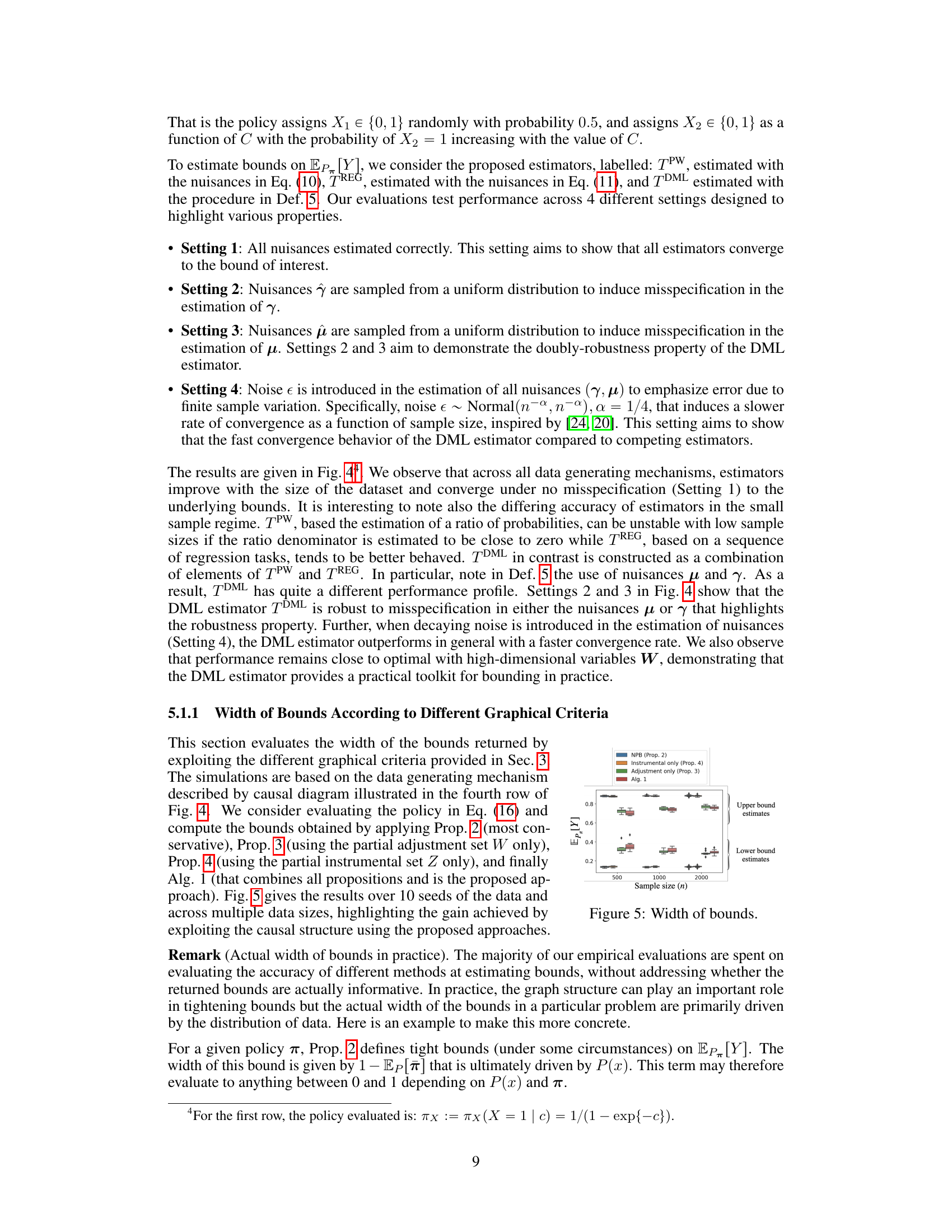

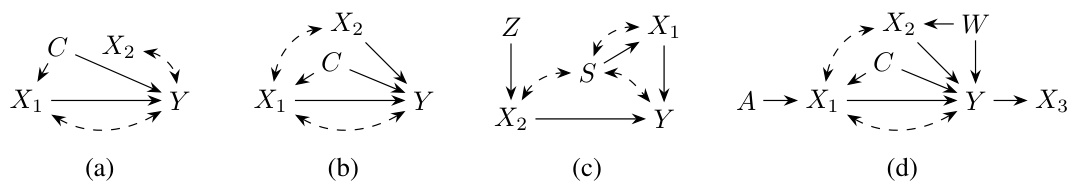

This figure shows box plots of the absolute average error (AAE) for three different estimators (PW, REG, DML) across four different settings. Each setting represents a different data generating mechanism or a different level of misspecification in estimating nuisance parameters. The x-axis represents the sample size (n), and the y-axis represents the AAE. The different rows correspond to different causal graph structures, highlighting the performance of the estimators under various conditions, including the presence of partial instrumental sets, partial adjustment sets, high-dimensional adjustment sets, and combinations thereof. The results show how the DML estimator is robust to misspecification and converges quickly, improving accuracy with larger sample sizes.

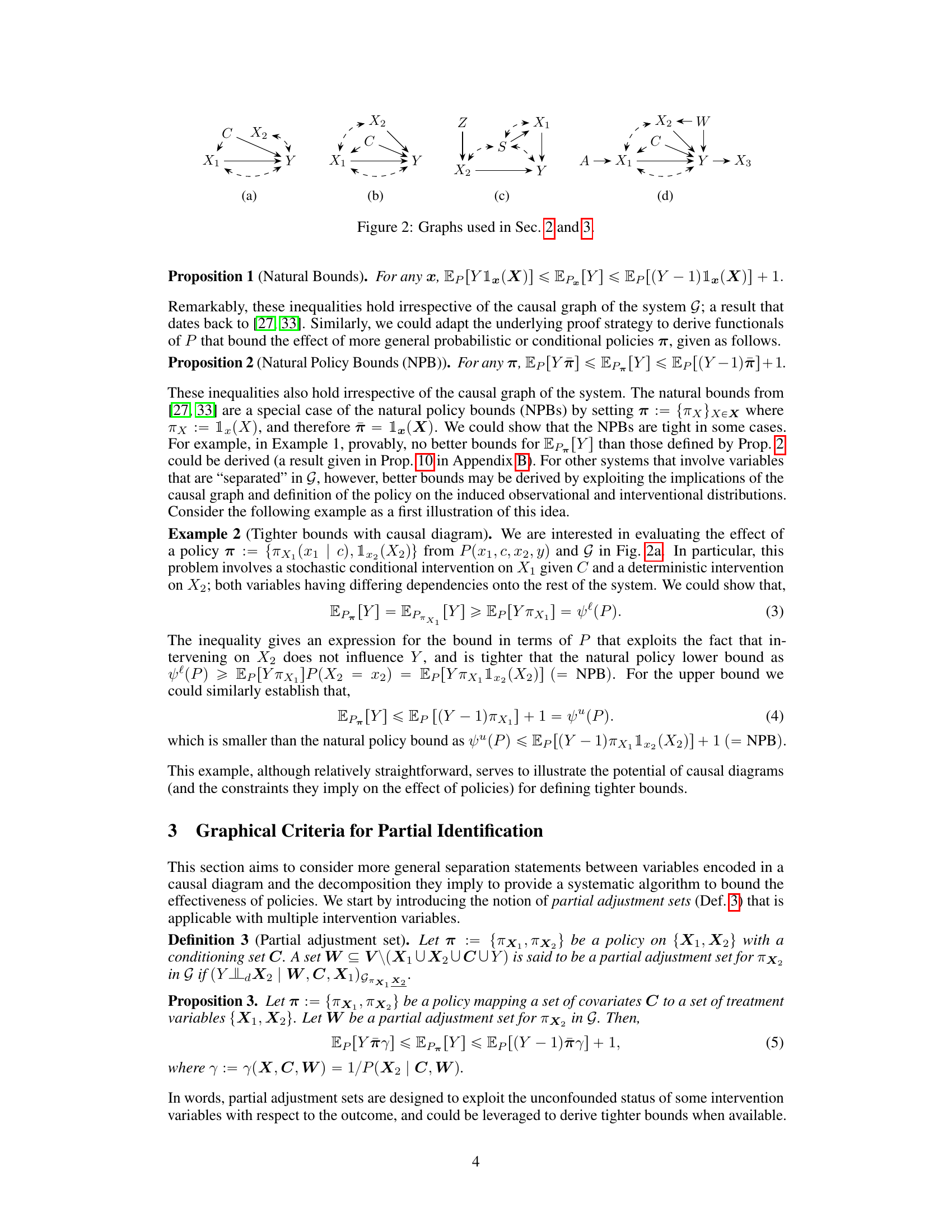

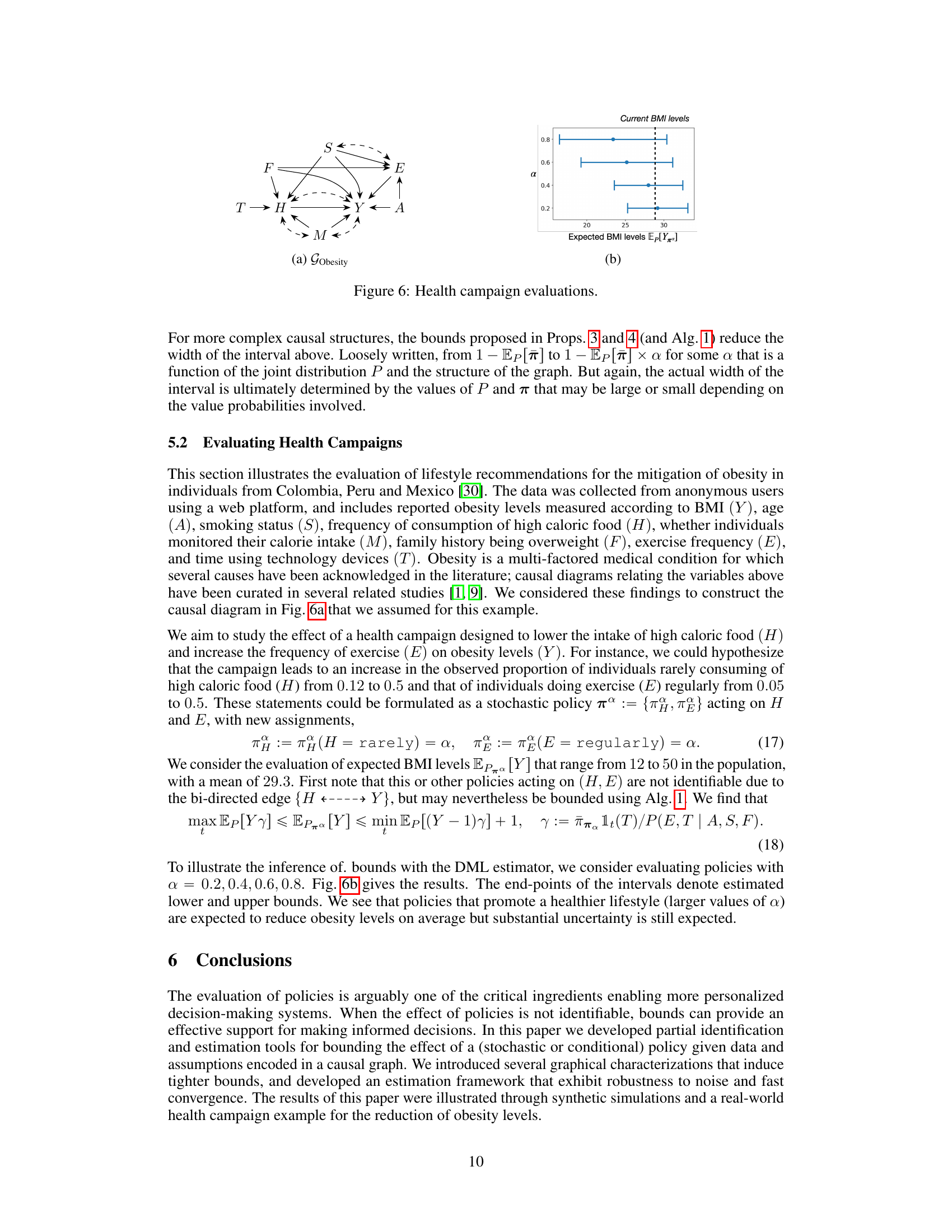

This figure shows the width of bounds obtained from different methods described in the paper, including natural policy bounds, bounds using instrumental variables only, bounds using adjustment sets only, and bounds using the proposed algorithm (Alg. 1). It demonstrates how tighter bounds can be achieved by leveraging the graphical criteria proposed in Section 3. The results are shown across different sample sizes. The width of the bounds is evaluated by calculating the difference between the upper and lower bounds of the expected outcome Y under a policy π, which represent the uncertainty in the estimated policy effect.

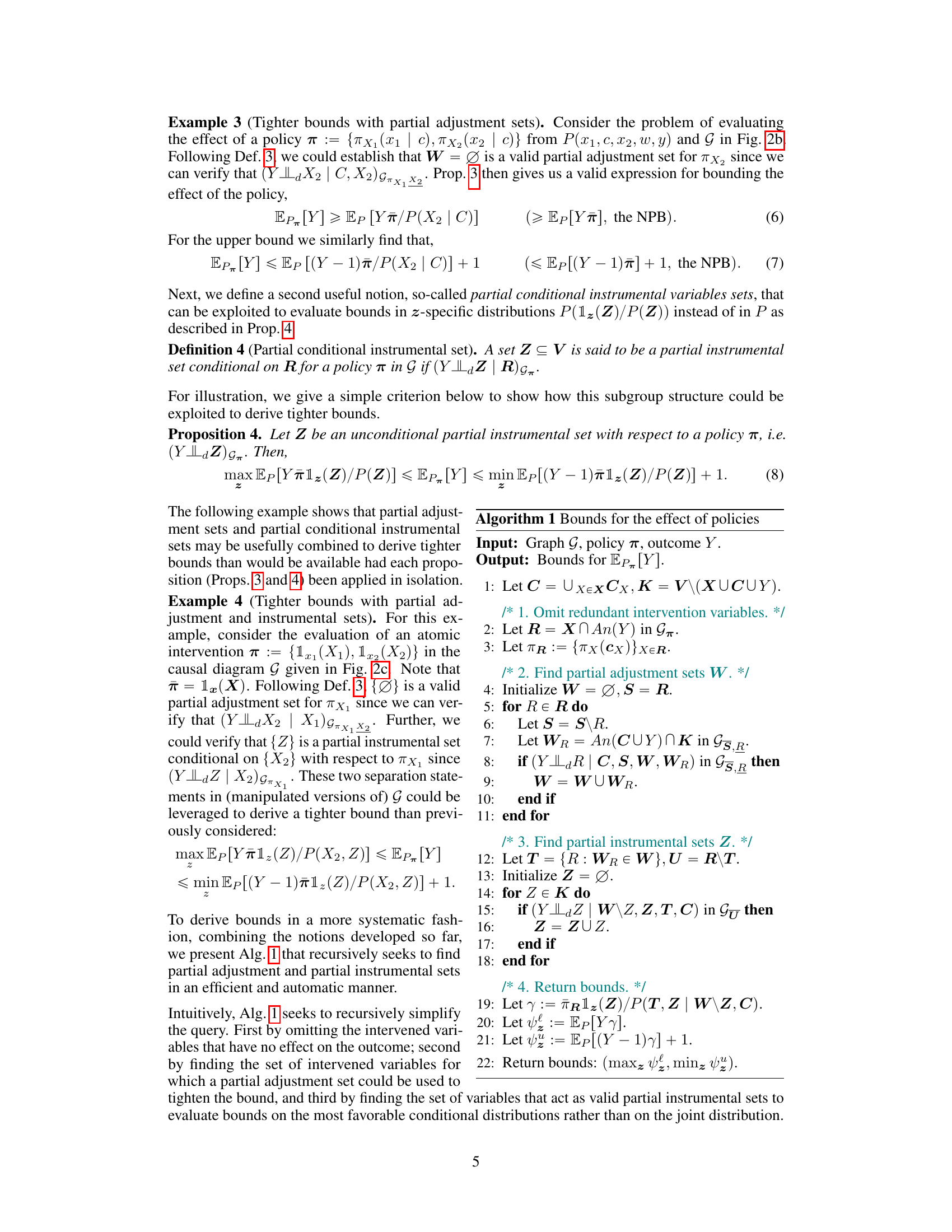

This figure shows the causal graph used to model the relationships between variables related to obesity and lifestyle in individuals from Colombia, Peru, and Mexico. The graph (a) represents the assumed causal structure, showing relationships between variables such as smoking status (S), family history of obesity (F), frequency of exercise (E), consumption of high-calorie foods (H), monitoring of calorie intake (M), age (A), time spent using technology devices (T), and obesity levels (Y). The graph (b) shows the results of evaluating the effects of a health campaign designed to influence the frequency of exercise and consumption of high calorie foods, expressed as box plots. The width of the box plot indicates the uncertainty in the estimated impact (the actual width of the interval is ultimately determined by the values of P and π that may be large or small depending on the value probabilities involved). Each data point represents the average treatment effect (ATE) for a specific value of α, showing the expected BMI levels resulting from this health campaign.

This figure shows three causal diagrams representing different stages in the analysis of a health campaign to reduce obesity. (a) shows the original causal graph, denoted as G, representing the relationships between variables (Obesity (Y), Age (A), Smoking (S), Frequency of high caloric food (H), Monitoring of calorie intake (M), Family history of being overweight (F), and Exercise (E)). (b) shows the causal graph after the policy intervention (Gπ), where the policy influences variables H and E. Finally, (c) shows the mutilated graph (GπH,πE), where the influence of the policy on variables H and E is explicitly represented through directed edges, simplifying the causal relationships to facilitate the bounding of effects in the analysis.

Full paper#