↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Computing the Graph Edit Distance (GED) between graphs is crucial for various applications, but existing methods struggle with computational complexity and the handling of diverse costs associated with different graph edit operations. Furthermore, existing neural approaches often lack the ability to explicitly incorporate these costs, limiting their accuracy and applicability. The difficulty lies in the NP-hard nature of GED calculation.

The paper introduces GRAPHEDX, a neural GED estimator that addresses these limitations. It leverages a novel combination of techniques: formulating GED as a quadratic assignment problem, employing neural set divergence surrogates to approximate QAP terms, and utilizing a Gumbel-Sinkhorn permutation generator for node and edge alignment. The results demonstrate that GRAPHEDX consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods on several datasets and various cost configurations, showcasing its accuracy and efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on graph similarity and optimal transport. It presents GRAPHEDX, a novel neural model that significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of Graph Edit Distance (GED) calculation, especially with varied edit costs. This opens new avenues for research in applications demanding efficient graph comparisons like image retrieval and bioinformatics.

Visual Insights#

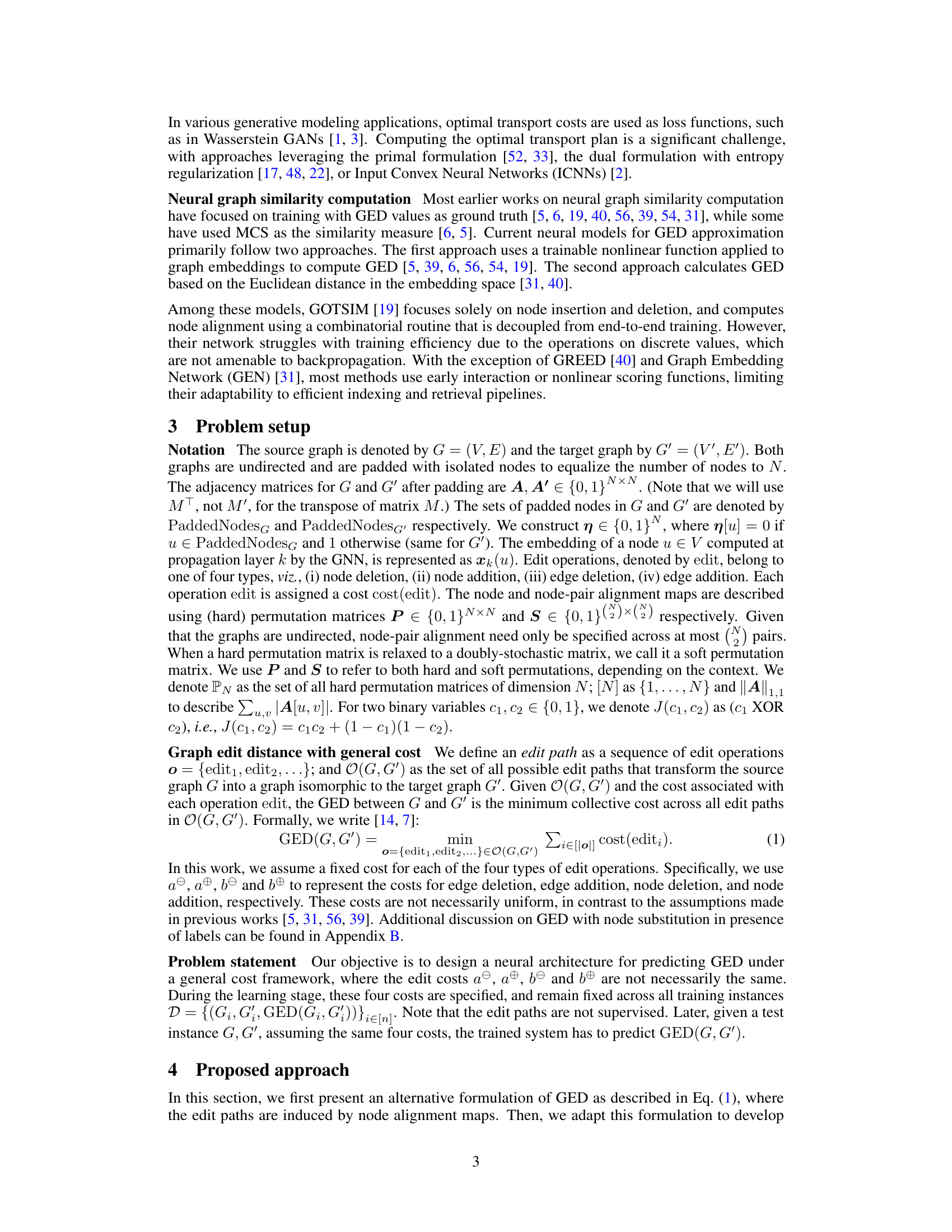

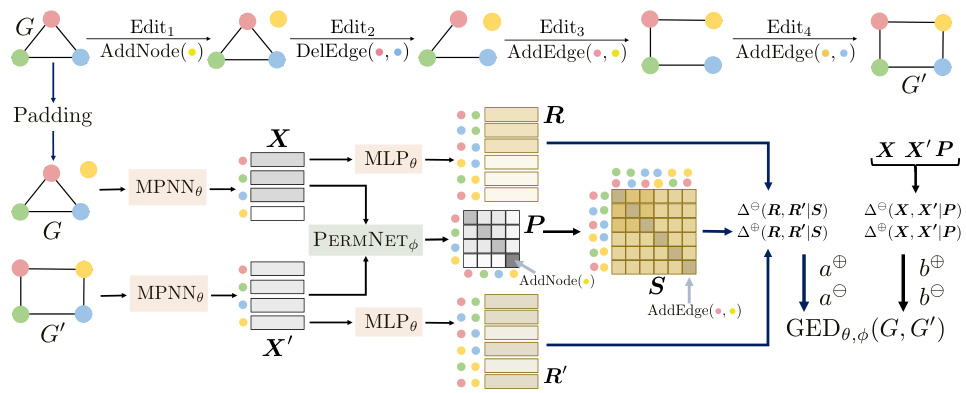

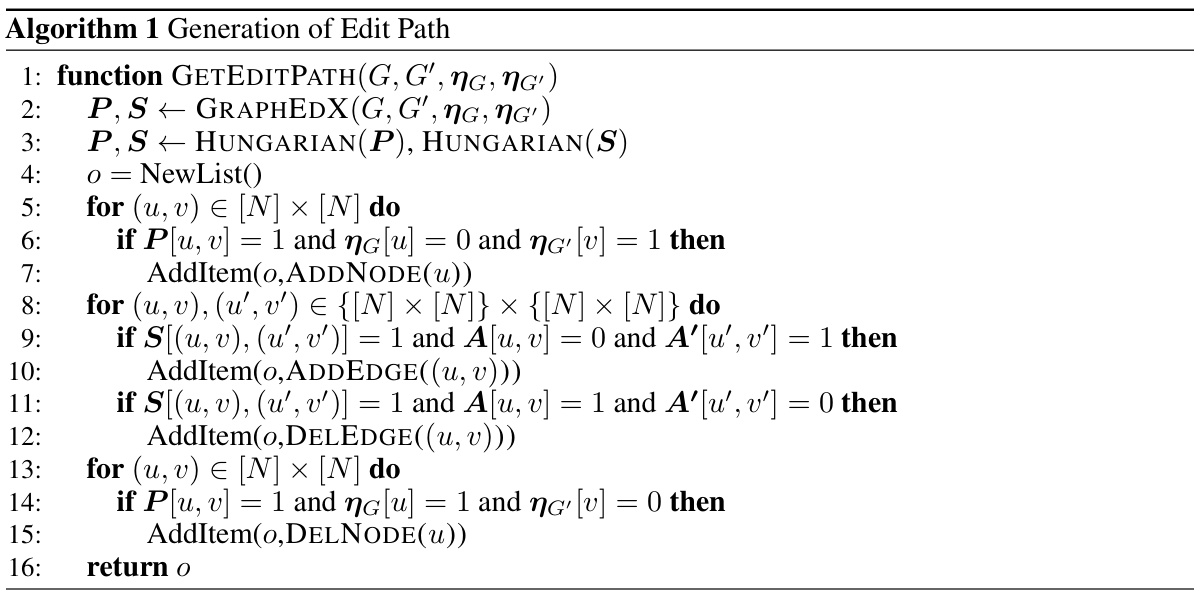

The figure illustrates the architecture of GRAPHEDX, a neural model for computing GED. The top part shows example graphs illustrating the optimal edit path between source and target graphs. The bottom part illustrates the process: 1) MPNNs process each graph independently, 2) a PERMNET module generates node alignment P and node-pair alignment S, 3) MLPs generate node and edge embeddings, and 4) these are combined to estimate the final GED.

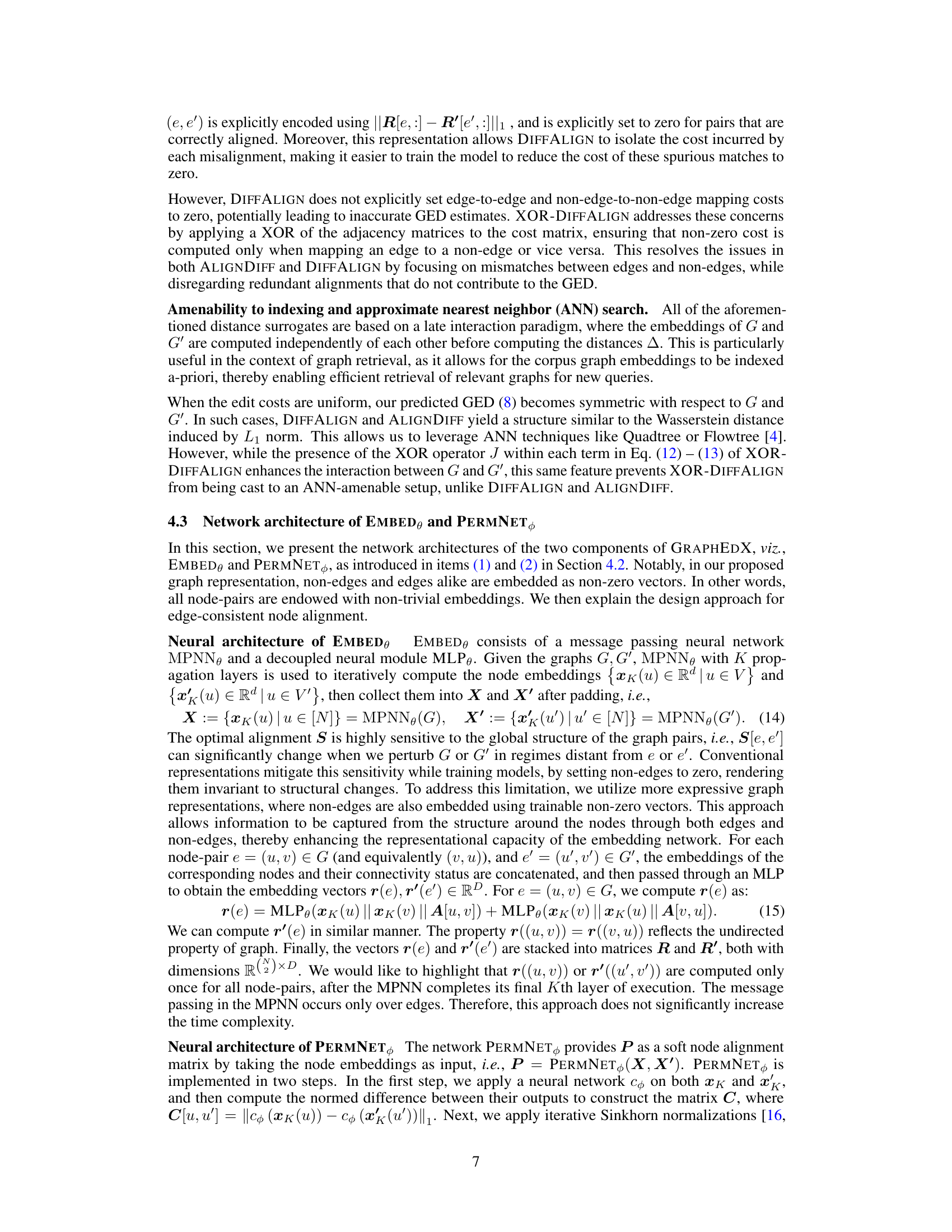

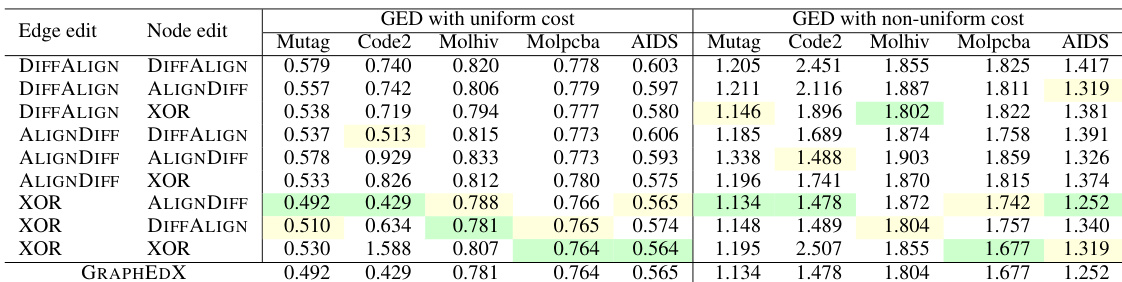

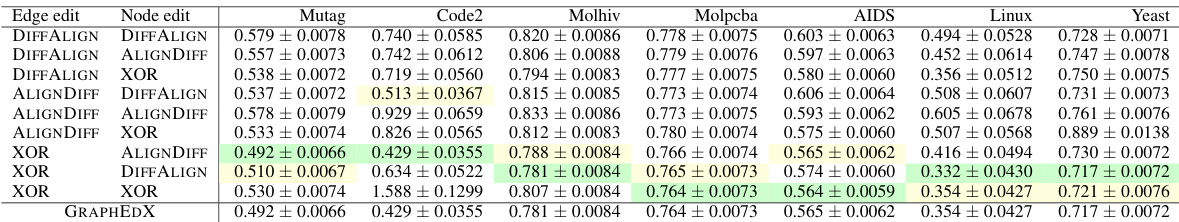

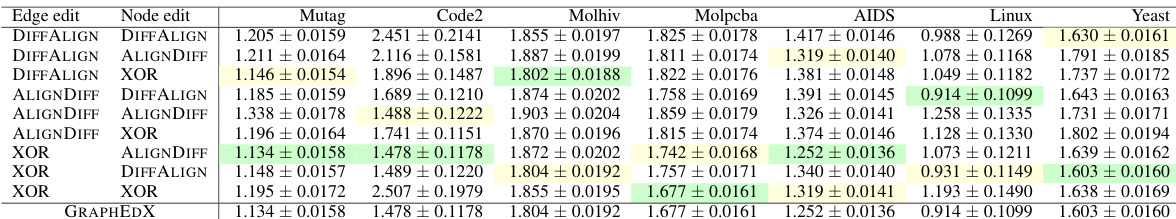

This table presents the mean squared error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates for the task of graph edit distance (GED) prediction on five datasets. Each combination represents a different choice of surrogate for edge edits and node edits. The table shows results for both uniform and non-uniform cost settings. The GRAPHEDX model selection is based on the lowest validation MSE, and the test MSE is reported.

In-depth insights#

Neural GED Models#

Neural GED models represent a significant advancement in addressing the computational challenges of Graph Edit Distance (GED) calculation. Traditional methods struggle with the NP-hard nature of GED, limiting their scalability. Neural approaches leverage the power of deep learning to approximate GED, often by learning embeddings of graphs and then calculating distances between these embeddings. This allows for faster computation and better handling of large graphs, though accuracy can be affected by the nature of the embedding and the choice of distance metric. Key improvements include the ability to explicitly incorporate varying costs for different edit operations (node/edge insertion, deletion, substitution), leading to more nuanced comparisons tailored to specific applications. Furthermore, these models can be designed for efficient indexing and retrieval, enabling fast similarity searches in large graph databases. Despite the progress, limitations remain. The accuracy of the GED approximation depends heavily on the quality of the graph embeddings, and the choice of neural architecture. Generalizing across diverse graph structures and handling graphs with highly variable properties or noise remains a challenge. Future research will likely focus on improving the robustness, accuracy, and explainability of these models.

QAP Formulation#

A Quadratic Assignment Problem (QAP) formulation for Graph Edit Distance (GED) offers a structured way to model the problem, explicitly representing the cost of each edit operation (node insertion, deletion, edge insertion, deletion) as distinct parameters within the QAP cost matrix. This allows for flexibility in incorporating domain-specific knowledge about the relative importance of different edit types, unlike simpler approaches that assume uniform costs. The QAP formulation, however, comes with the significant drawback of being NP-hard, making exact solutions computationally intractable for large graphs. This inherent complexity motivates the need for approximation algorithms or heuristic approaches, such as those explored in the paper using neural networks to learn a surrogate for the QAP objective. By framing GED as a QAP, the authors provide a rigorous mathematical foundation for their neural approach. The QAP formulation is a crucial stepping stone to developing an efficient and accurate neural GED estimator that can handle general cost functions.

Set Divergence#

The concept of set divergence, in the context of neural graph edit distance calculation, offers a compelling alternative to traditional quadratic assignment problem (QAP) formulations. Set divergence methods cleverly sidestep the computational intractability of QAP by representing graphs as sets of node and edge embeddings. This allows for the application of differentiable set comparison techniques, enabling efficient end-to-end training of neural models. The choice of a specific set divergence measure impacts the model’s performance and interpretation. Key advantages include the ability to handle graphs of varying sizes and structures seamlessly and to explicitly incorporate different costs for various edit operations (addition, deletion, substitution). However, the effectiveness hinges on the ability to learn meaningful graph embeddings and appropriate alignment mechanisms between nodes and edges. The use of techniques like Gumbel-Sinkhorn to generate soft permutations for node alignment is crucial for maintaining differentiability throughout the learning process. Careful consideration of the chosen set divergence and its interaction with the embedding methodology and alignment technique is critical to optimize model accuracy and efficiency.

Alignment Learning#

Alignment learning in the context of graph edit distance (GED) computation is crucial for accurately estimating the similarity between graphs. Effective alignment of nodes and edges from the source and target graphs is paramount to accurately reflect the cost of the edit operations (insertion, deletion, substitution). The challenge lies in finding the optimal alignment that minimizes the total cost of transformations, which is computationally expensive. Different approaches address this, from using combinatorial optimization methods (like the Hungarian algorithm) that operate on discrete assignments, to neural network approaches that learn soft alignments through differentiable surrogates, such as the Gumbel-Sinkhorn network. The key to success is the choice of a suitable alignment technique that balances computational feasibility with the quality of alignment and its ability to integrate with the cost model. The choice also dictates the network architecture, whether it allows for early interaction (where alignments influence node and edge embeddings) or late interaction where this happens only after embedding calculation. The effectiveness of alignment learning directly impacts the accuracy of GED prediction and is closely tied to the overall performance of the GED estimation method.

Cost-Sensitive GED#

Cost-sensitive Graph Edit Distance (GED) is a crucial extension of the standard GED, addressing the limitation of uniform edit costs. Standard GED assumes all edit operations (node insertion, deletion, edge insertion, deletion) have equal costs, which is unrealistic in many real-world applications. A cost-sensitive approach allows assigning different weights to these operations, reflecting their relative importance. For instance, deleting a crucial node might be far more costly than adding a less important one. This enhanced flexibility makes cost-sensitive GED far more applicable to domain-specific problems, where the cost of certain edits may be significantly higher or lower than others. The key challenge lies in efficiently computing the minimum cost edit sequence under these variable costs, as the problem remains NP-hard even with a cost matrix. The paper tackles this challenge by proposing novel neural network architectures to approximate cost-sensitive GED, achieving significant improvements over existing methods. The success of these neural methods hinges on effectively capturing the relationship between edit costs and graph structure, which is a fundamental challenge in graph similarity calculation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure illustrates an example of two graphs and their optimal alignment, along with the architecture of the GRAPHEDX model. The top part shows two example graphs, G and G’, with color-coded nodes indicating the optimal node alignment. The bottom part shows the proposed GED prediction pipeline that uses MPNN to encode the graphs, MLP to obtain node-pair embeddings, PERMNET to obtain soft node alignment, and finally computes the GED using the learned alignment and cost parameters.

This figure illustrates the GRAPHEDX model architecture. The top panel shows an example of two graphs and their optimal alignment. The bottom panel depicts the model’s pipeline. The graphs are encoded using MPNNs, then padded and processed through MLPs to get node-pair embeddings. The PERMNET generates a soft node alignment, leading to the node-pair alignment. Finally, node and edge costs are estimated from embeddings and combined to obtain the GED prediction.

The figure illustrates an example of two graphs (G and G’) and their optimal alignment, color-coded to show the edit operations needed to transform G into G’. The bottom part shows the architecture of GRAPHEDX, a neural network that predicts the Graph Edit Distance (GED). It uses message passing neural networks (MPNNs) to generate node and edge embeddings, followed by a Gumbel-Sinkhorn network (PERMNET) to learn a soft node alignment. The node and edge embeddings are then used to compute set divergences that approximate the costs of the four edit operations (node insertion, node deletion, edge insertion, edge deletion), which are summed to give the final GED prediction.

The figure illustrates the GRAPHEDX model’s architecture and workflow. The top part shows an example of two graphs and their optimal node alignment, representing the edit operations required to transform one graph into the other. The bottom part depicts the model’s pipeline, detailing how graphs are encoded using message-passing neural networks (MPNNs), how node and edge alignments are learned using a Gumbel-Sinkhorn network (PERMNET), and how these alignments are used to compute the final Graph Edit Distance (GED).

The figure shows an example of two graphs G and G’, their alignment, and the architecture of GRAPHEDX model for predicting Graph Edit Distance (GED). The top part illustrates an example of two graphs and their optimal alignment, while the bottom part depicts the architecture of the GRAPHEDX model. The model consists of several components: MPNN for generating node embeddings, MLP for generating node-pair embeddings, PERMNET for generating soft node alignment matrix P, and the final layer which combines the embeddings and alignment information to compute the GED.

This figure illustrates the GRAPHEDX model’s architecture. The top panel shows an example of two graphs and their optimal node alignment, while the bottom panel depicts the model’s pipeline. The model independently processes each graph using an MPNN, then generates soft node and edge alignments using a PERMNET. Finally, these alignments are used to compute the GED by combining the individual costs of edge/node addition and deletion.

More on tables

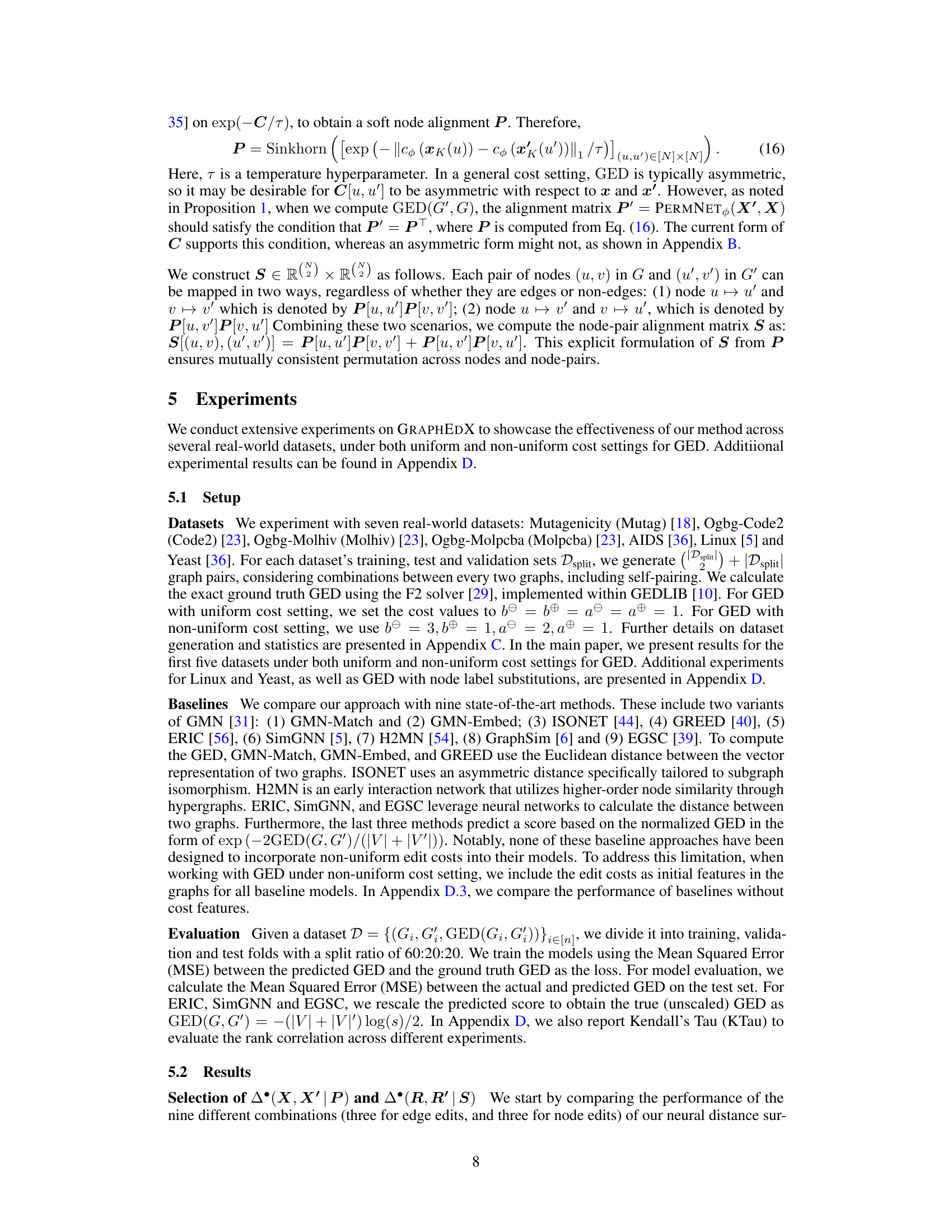

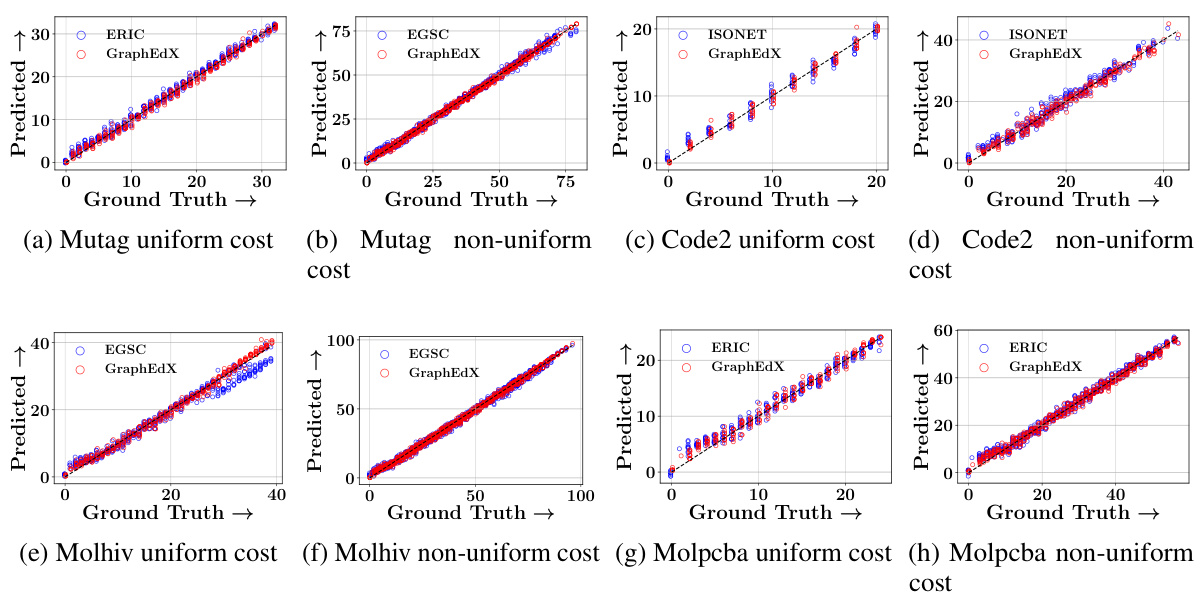

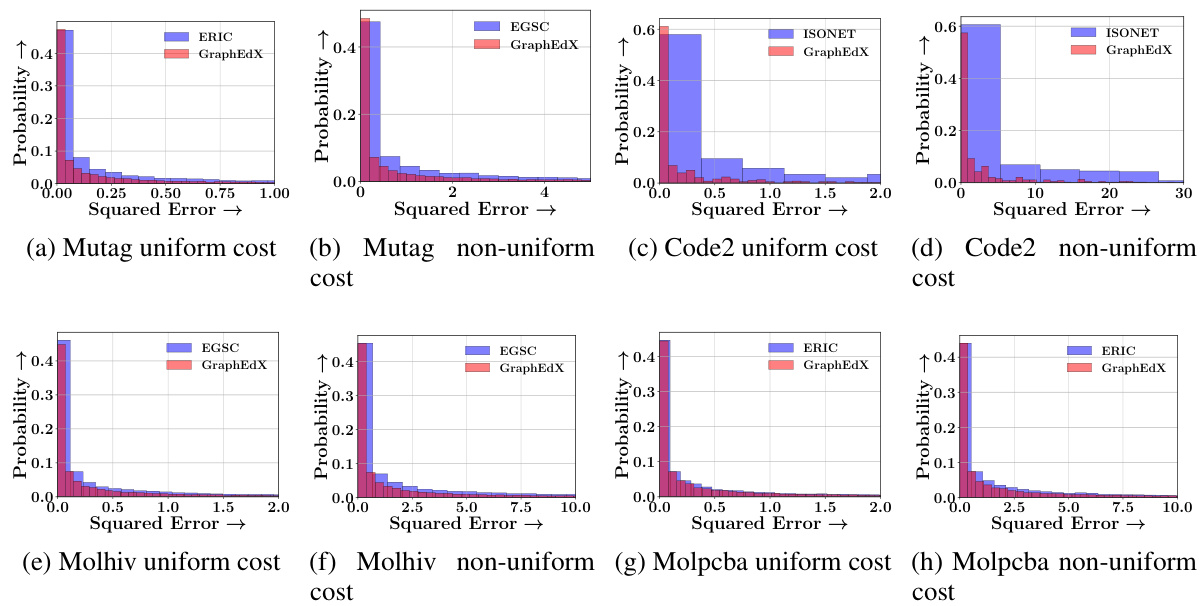

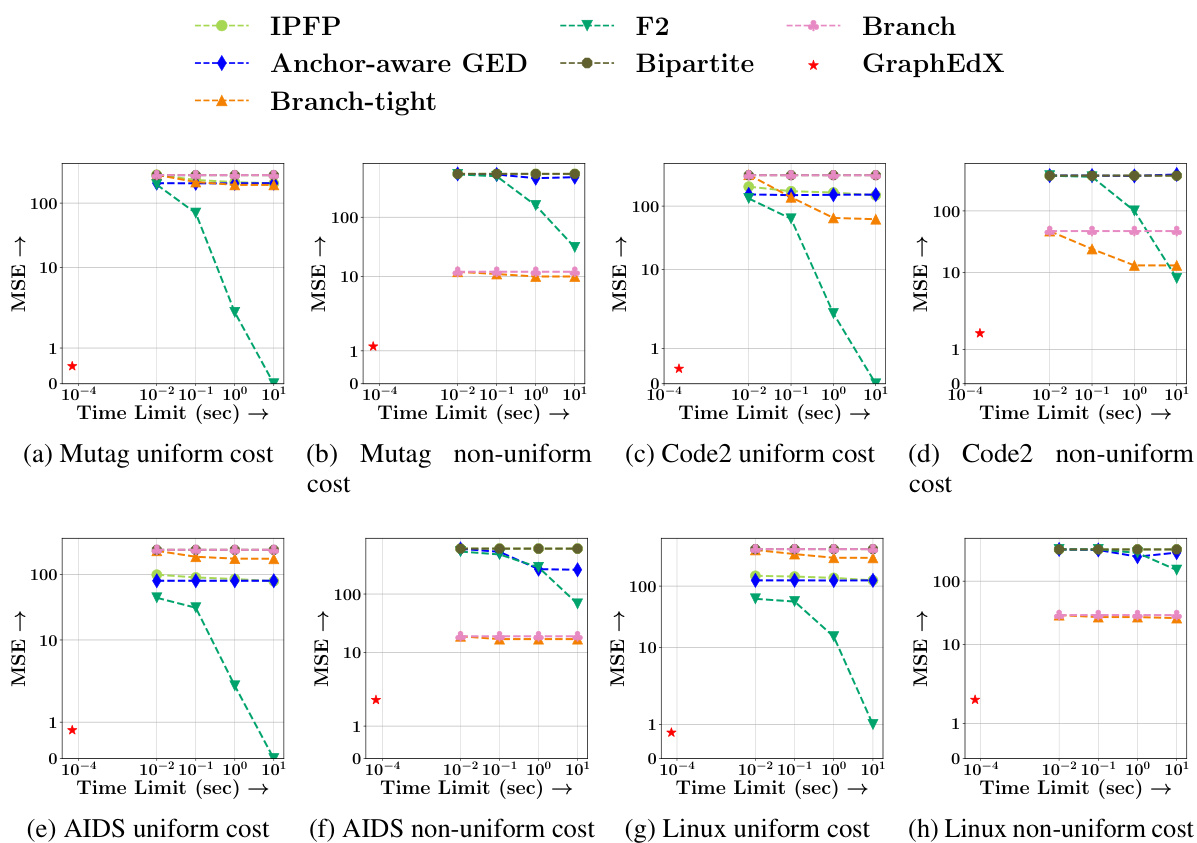

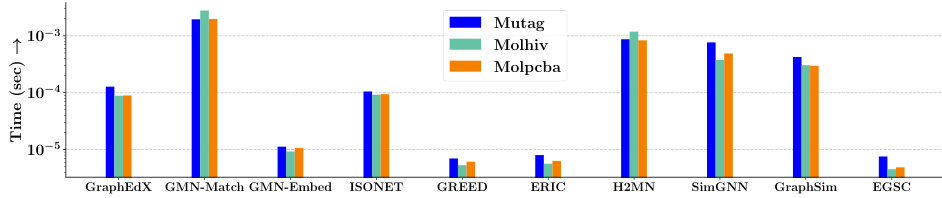

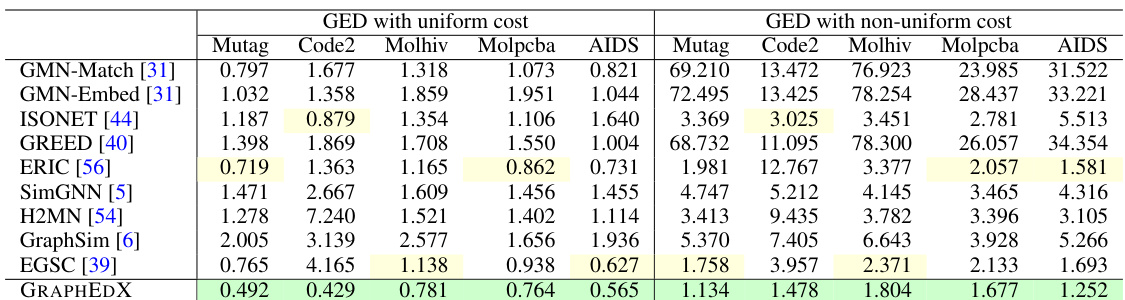

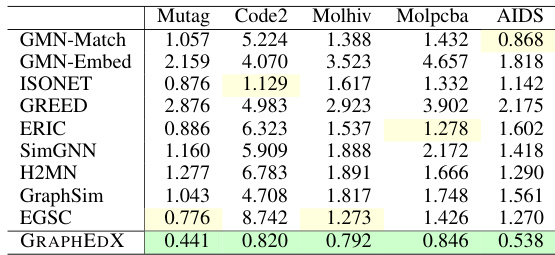

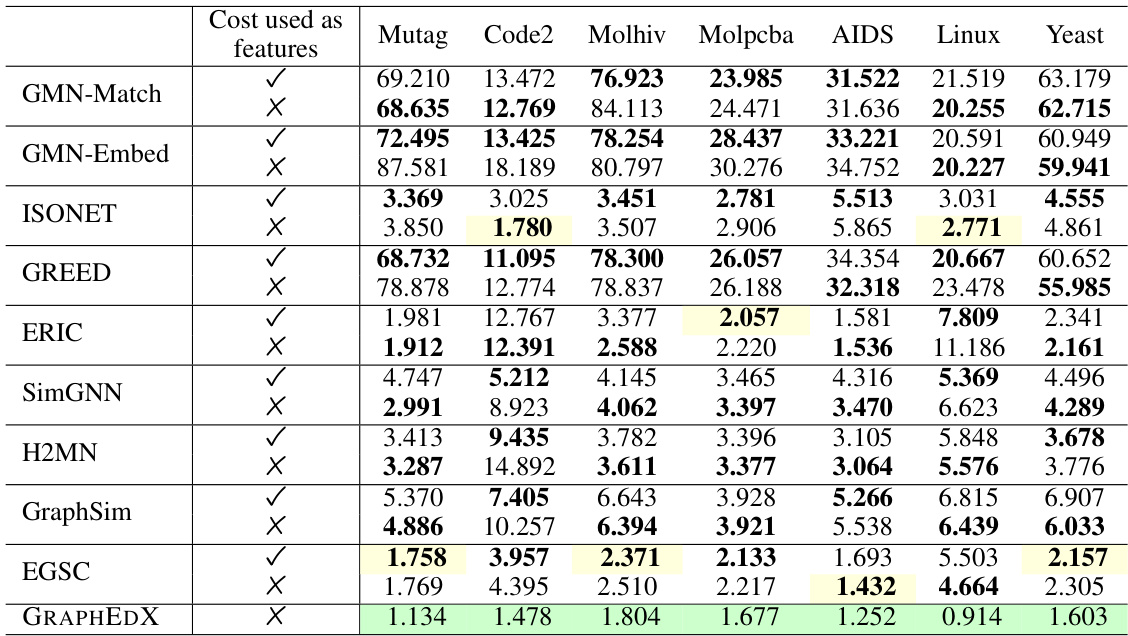

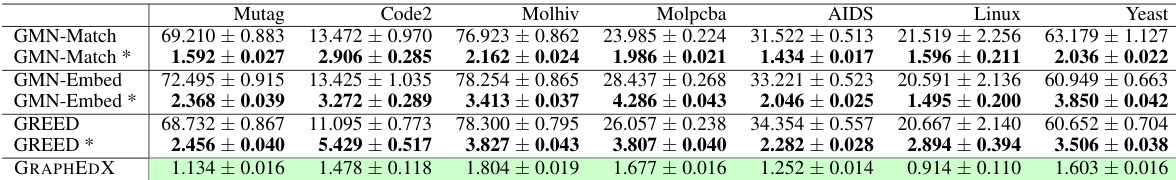

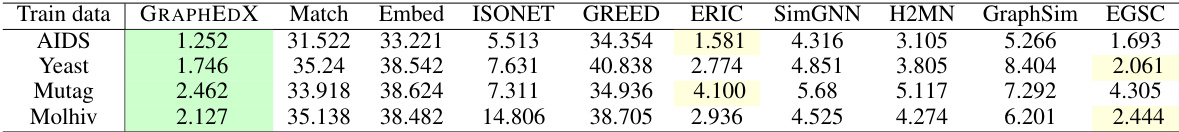

This table compares the performance of the proposed GRAPHEDX model against other state-of-the-art methods for predicting the Graph Edit Distance (GED) under two different cost settings: uniform and non-uniform. The MSE (Mean Squared Error) is used as the performance metric. The table shows that GRAPHEDX consistently achieves the lowest MSE, outperforming all other methods, highlighting its effectiveness across various datasets.

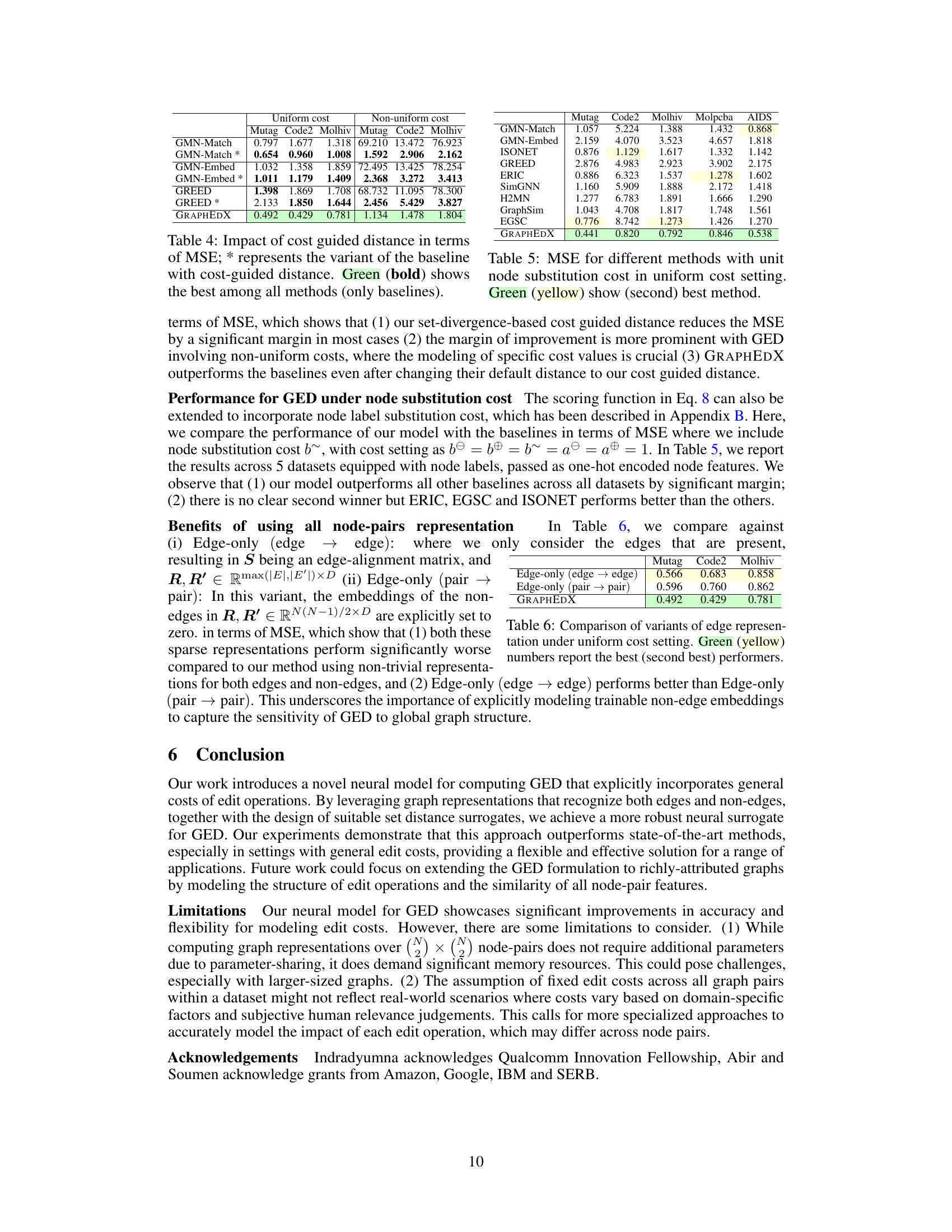

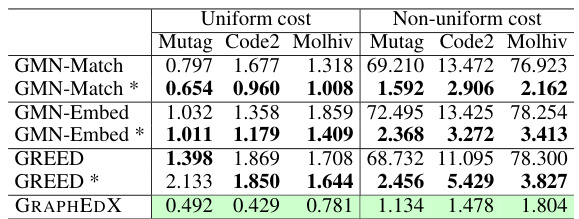

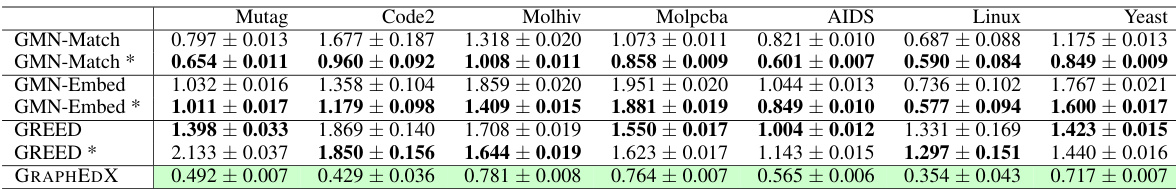

This table compares the performance of several baselines for GED prediction with and without using a cost-guided distance. The results show that incorporating cost information significantly improves the performance of several baselines. The cost-guided GRAPHEDX model consistently outperforms all baselines.

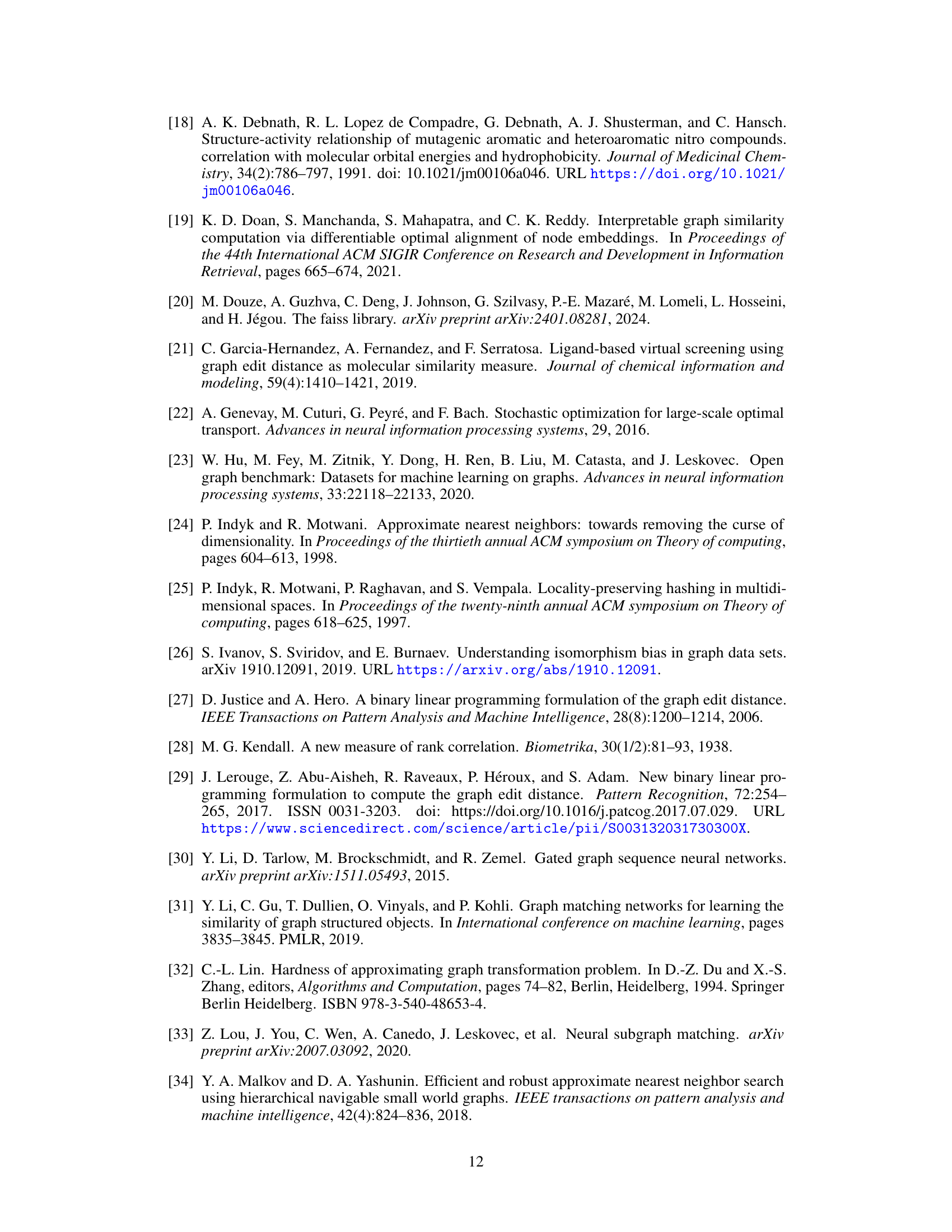

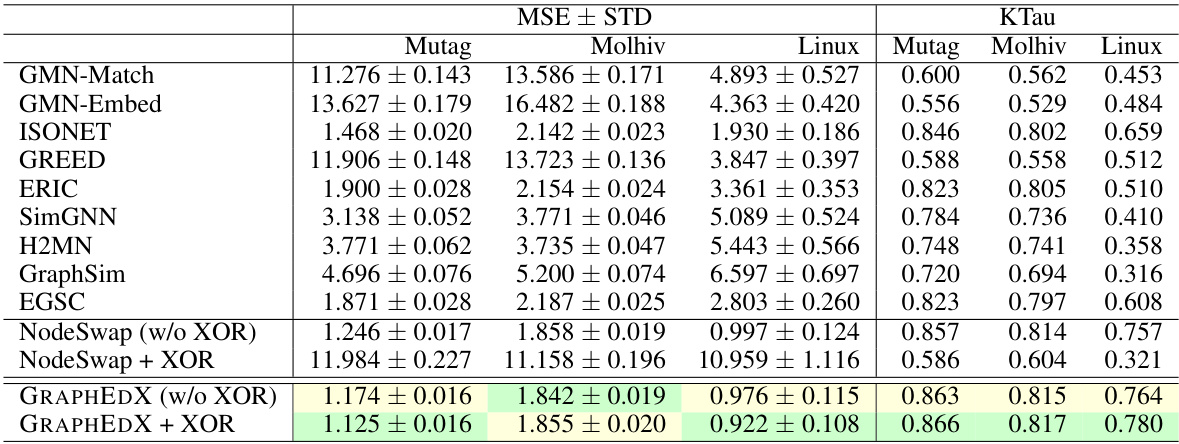

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for various graph edit distance methods when a unit cost is applied to node substitutions, under a uniform cost setting. The best performing method (lowest MSE) is highlighted in green, and the second-best is highlighted in yellow. It showcases the relative performance of different techniques for GED approximation under specific cost conditions. This allows for comparison of the methods’ accuracy in calculating the GED, accounting for node label changes.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for nine different combinations of neural set distance surrogates used in the GRAPHEDX model. The MSE is calculated for five datasets under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for the Graph Edit Distance (GED). The best-performing combination, based on validation set performance, is highlighted as the chosen GRAPHEDX model.

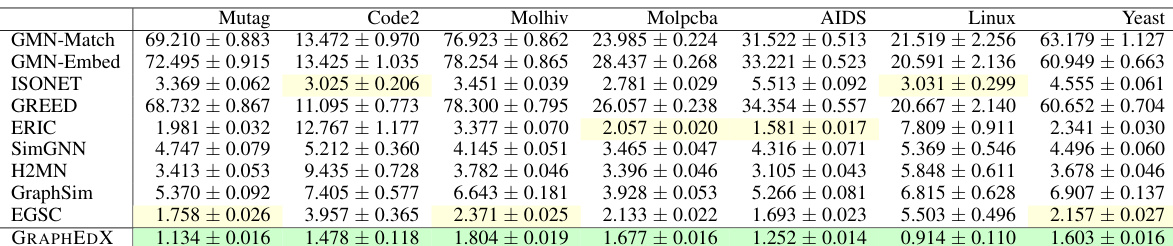

This table presents a summary of the characteristics of the seven datasets used in the experiments. For each dataset, it shows the number of graphs, the number of training, validation, and test pairs, the average number of nodes and edges per graph, and the average graph edit distance (GED) under uniform and non-uniform cost settings.

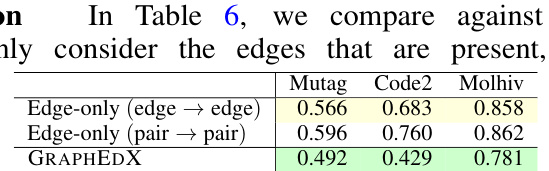

This table compares the performance of different models in predicting the Graph Edit Distance (GED) under a specific cost setting where node costs are zero and edge addition and deletion costs are different. It highlights the impact of using edge-alignment versus node-alignment based methods for predicting GED. The results show the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Kendall’s Tau (KTau) for various models and datasets.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates for Graph Edit Distance (GED) prediction on five datasets. The combinations vary the surrogates used for edge edits and node edits, with three options (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN) for each. The experiment is performed with both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for GED. The model selection for GRAPHEDX is based on the minimum validation MSE; this table displays the test MSE for the selected model.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) comparison of the proposed GRAPHEDX model against nine state-of-the-art baseline methods for computing the Graph Edit Distance (GED) on five real-world datasets. The comparison is done under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for GED. The best-performing model according to validation error is chosen as GRAPHEDX for each dataset. The table highlights the significant performance advantage of GRAPHEDX across all datasets and cost settings.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates used in the GRAPHEDX model. The MSE is calculated for five datasets under two different cost settings: uniform and non-uniform. The table shows the performance of different surrogate combinations and highlights the best-performing combination used for GRAPHEDX.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates for predicting the Graph Edit Distance (GED) on five datasets. The surrogates are categorized by their approach to edge and node alignment (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN). The results are shown separately for both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for the GED calculation. The GRAPHEDX model, selected based on validation performance, is highlighted, along with the best and second-best performing combinations.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) comparison between GRAPHEDX and other state-of-the-art methods for predicting Graph Edit Distance (GED) under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings. It shows that GRAPHEDX significantly outperforms other methods across five real-world datasets, highlighting its superior performance in GED prediction.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates used in the GRAPHEDX model. The MSE is calculated for five datasets under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for Graph Edit Distance (GED). The best-performing combination (lowest MSE) on the validation set was chosen for the GRAPHEDX model, and those results are reported here for the test set. The table highlights the best and second-best performing combinations.

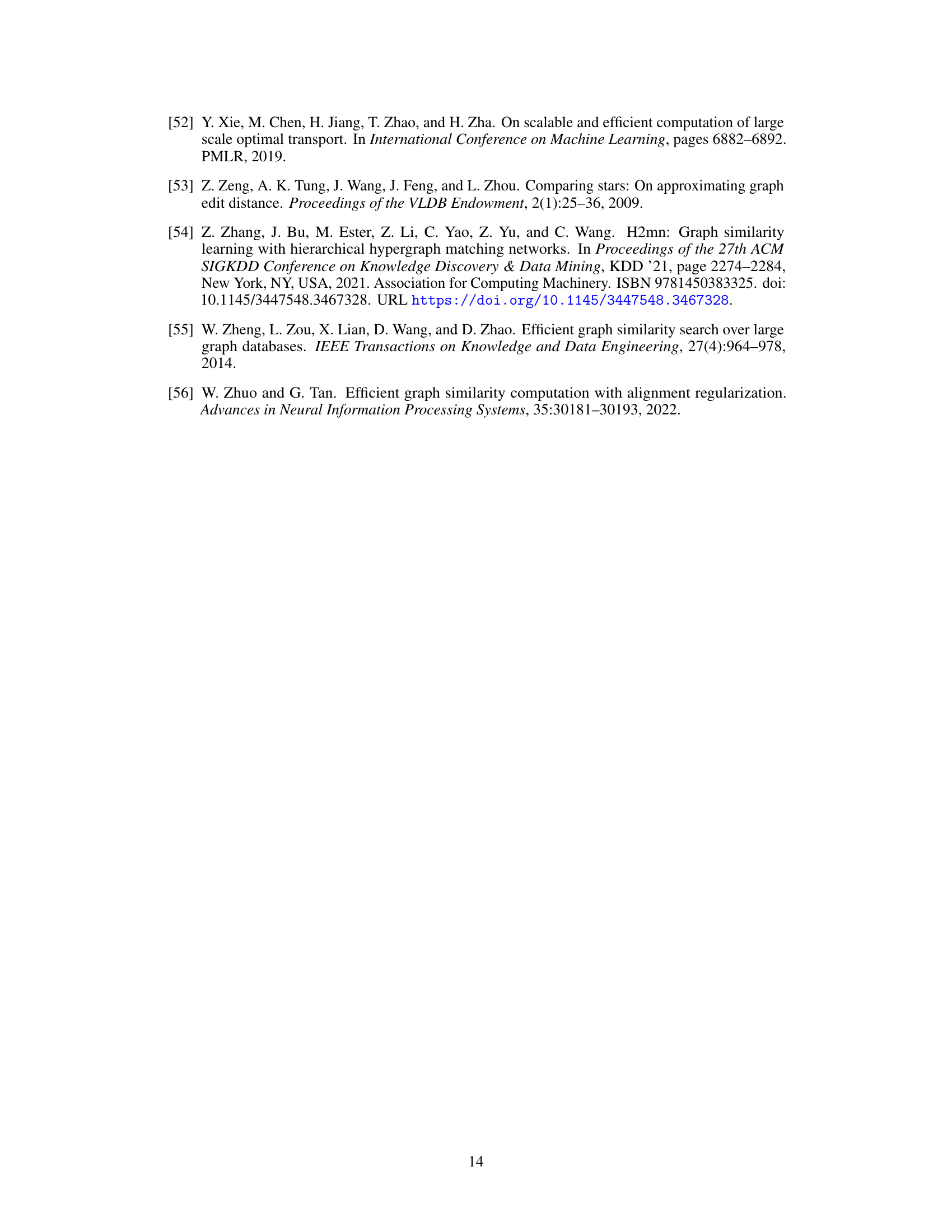

This table compares the performance of three different graph representations in predicting the Graph Edit Distance (GED) under a non-uniform cost setting. The three representations are: 1) using all node pairs (edges and non-edges) for computing GED; 2) using only the edges (and ignoring non-edges) to compute GED; and 3) using only edges but representing them as node pairs, but setting non-edge embeddings to zero. The table shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for each representation across multiple datasets. The results highlight the importance of considering both edges and non-edges for accurate GED prediction.

This table presents a comparison of the mean squared error (MSE) achieved by the proposed GRAPHEDX model and nine other state-of-the-art methods for predicting the graph edit distance (GED) on five datasets. The comparison is done under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for GED. The best performing model (lowest MSE) on the validation set is selected as GRAPHEDX. The results show that GRAPHEDX significantly outperforms the other models in most instances.

This table compares the performance of the proposed model (GRAPHEDX) against nine state-of-the-art baseline methods for predicting the Graph Edit Distance (GED) under two different cost settings: uniform and non-uniform. The MSE (Mean Squared Error) is used as the evaluation metric. GRAPHEDX consistently outperforms all baselines across five datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness even with non-uniform edit operation costs.

This table compares the mean squared error (MSE) of three different neural network models for predicting graph edit distance (GED). The models are GRAPHEDX (the proposed model in the paper), MAX, and MAX-OR. The results are presented for seven different datasets and show that GRAPHEDX generally performs best, with MAX-OR sometimes performing comparably well. MAX typically underperforms the other two methods.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GRAPHEDX model against nine state-of-the-art baseline methods for computing the Graph Edit Distance (GED) under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings. The MSE (Mean Squared Error) is used to evaluate prediction accuracy on five datasets. The table highlights GRAPHEDX’s superior performance and identifies the best- and second-best performing baseline methods for each dataset.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for nine different combinations of neural set distance surrogates used in the GRAPHEDX model. These combinations involve different methods for calculating the edge and node edit costs. The MSE is reported for five datasets under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for the Graph Edit Distance (GED). The best-performing combination for each dataset (under each setting) is highlighted in green, while the second-best is in yellow. The table demonstrates how different methods of computing the costs impact the model’s accuracy.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates for Graph Edit Distance (GED) prediction. Each combination uses one of three surrogates for edge edits (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN) and one of three for node edits. The table shows results for five datasets under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings. GRAPHEDX’s configuration (selected based on validation performance) is also shown.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates for Graph Edit Distance (GED) prediction. The surrogates are categorized by edge edit type (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN) and node edit type (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN). Results are shown for five datasets under both uniform and non-uniform cost settings for GED. The best-performing combination for each dataset is used to select the final GRAPHEDX model. The table highlights the MSE values for each combination, with the best and second-best performers clearly indicated.

This table presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) achieved by nine different combinations of neural set divergence surrogates used in the GRAPHEDX model. The surrogates are categorized into edge and node edit types, each with three variants (ALIGNDIFF, DIFFALIGN, XOR-DIFFALIGN). The MSE is calculated for both uniform and non-uniform edit cost settings across five datasets. The best performing combination is highlighted, along with the second-best performing combination.

Full paper#