↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Offline imitation learning (IL) faces the challenge of limited expert demonstrations, hindering effective policy learning. Existing methods often struggle with overfitting or inadvertently learning from sub-optimal data. This necessitates gathering more expert data which is often difficult, expensive, or simply not feasible.

The proposed method, SPRINQL, tackles this by incorporating both expert and sub-optimal demonstrations. It uses inverse soft-Q learning with learned weights to prioritize expert data while still benefiting from the larger sub-optimal dataset. SPRINQL’s formulation as a convex optimization problem improves efficiency and avoids adversarial training. Empirical results show that it outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods on offline IL benchmarks, demonstrating the value of utilizing readily available sub-optimal data to enhance the learning process.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents SPRINQL, a novel offline imitation learning algorithm that leverages sub-optimal demonstrations, a more realistic and readily available data source. This addresses a critical limitation in existing offline IL methods, paving the way for more robust and efficient AI systems in various applications. The algorithm’s theoretical properties and superior performance on benchmarks make it highly relevant to current research and open avenues for future development in offline reinforcement learning.

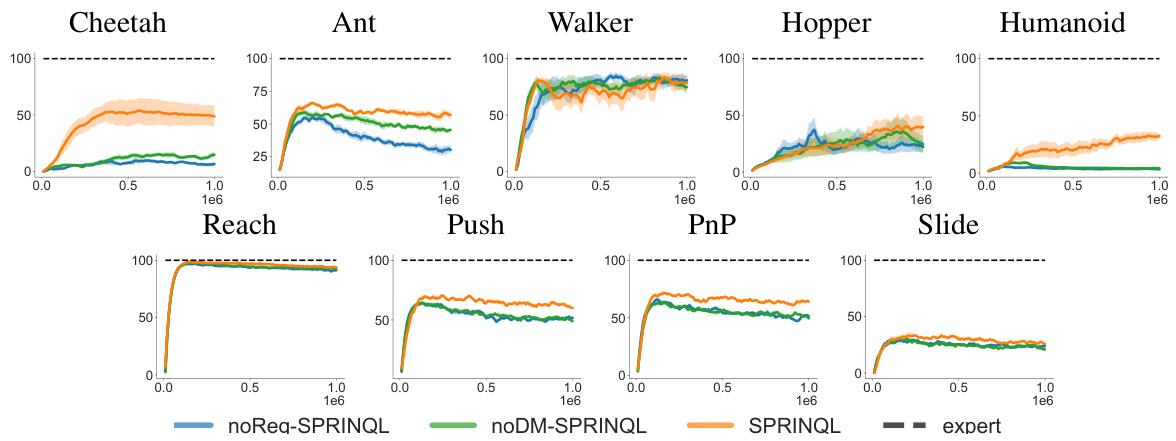

Visual Insights#

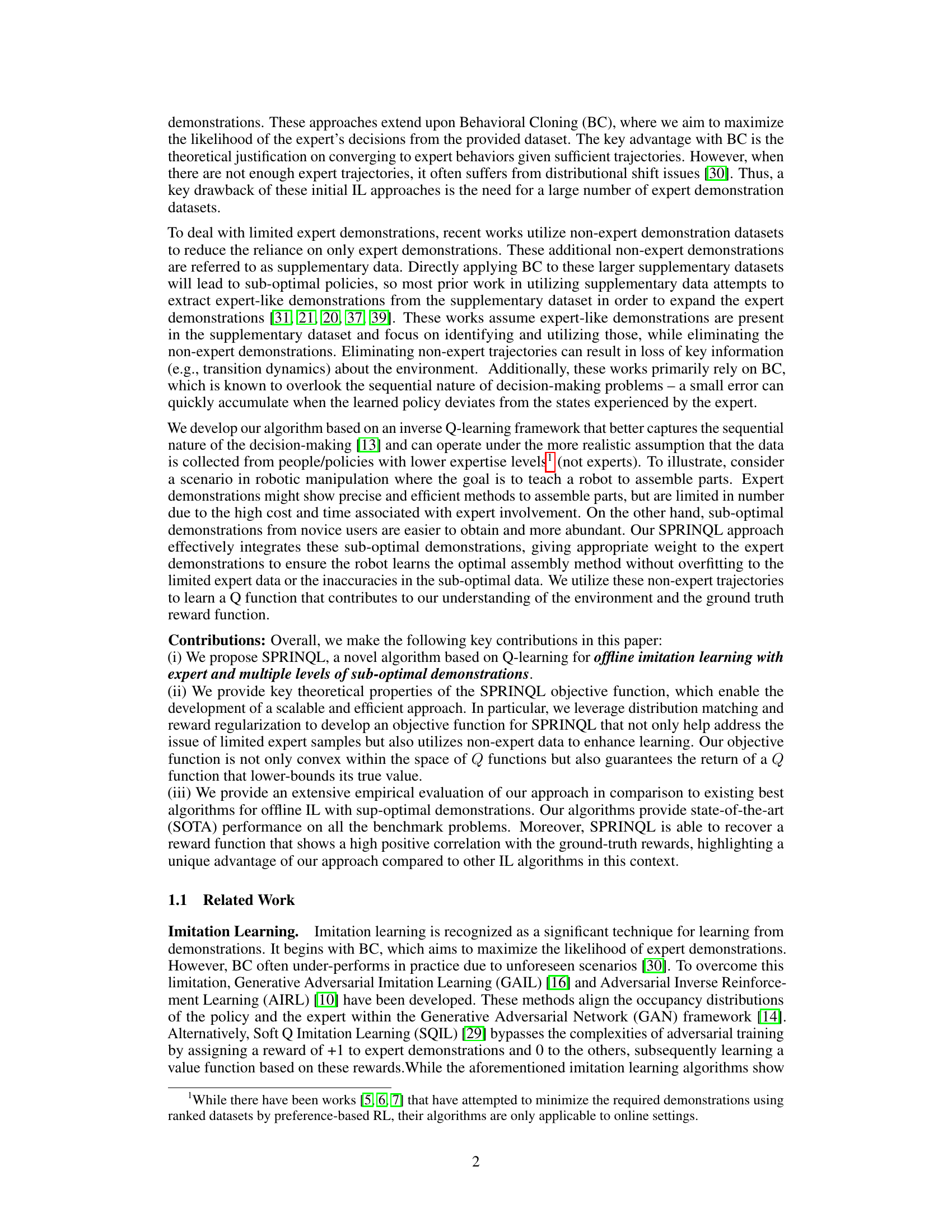

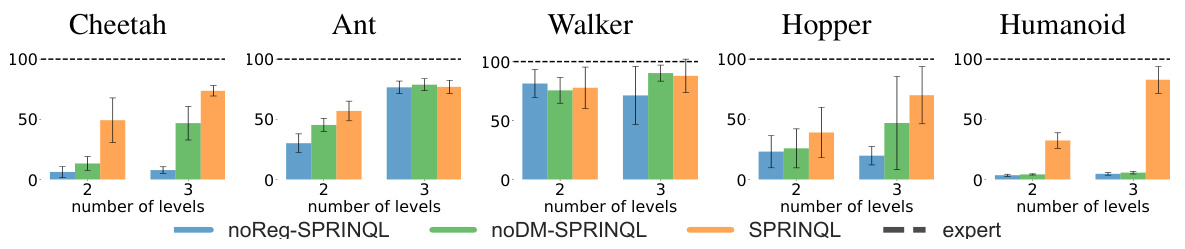

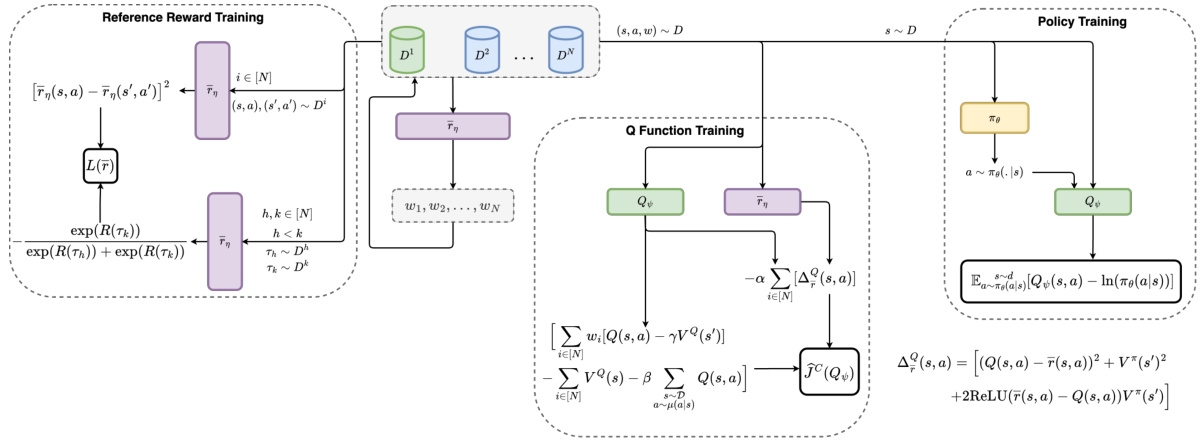

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm across five different Mujoco environments. The three variants are: SPRINQL (the full algorithm), noReg-SPRINQL (SPRINQL without the reward regularization term), and noDM-SPRINQL (SPRINQL without the distribution matching term). The performance is measured across different numbers of expertise levels (2 and 3 levels) for each environment. The ’expert’ performance is also shown as a baseline to compare to. The graph shows the normalized score achieved by each approach in each environment, providing a visual summary of the effectiveness of each component of the SPRINQL algorithm.

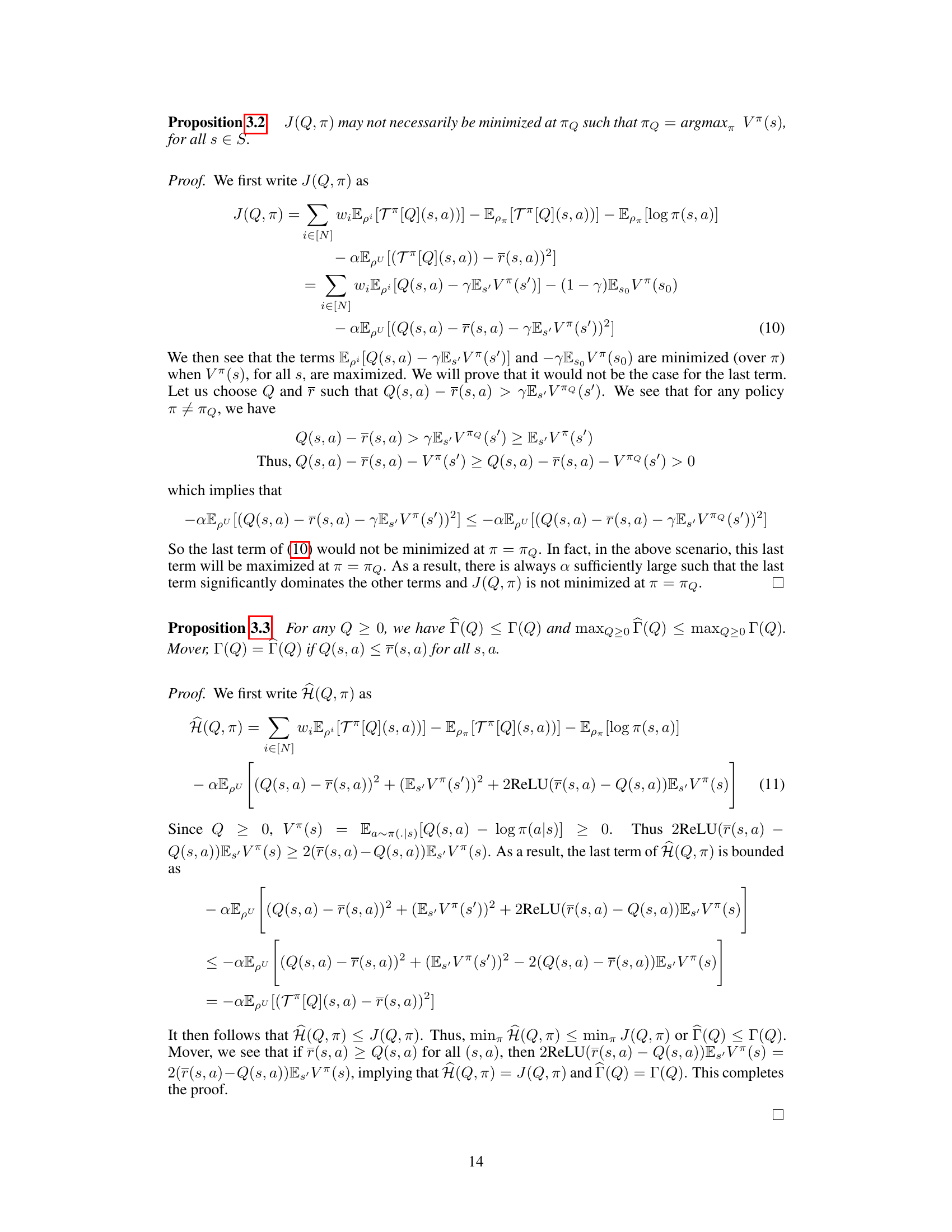

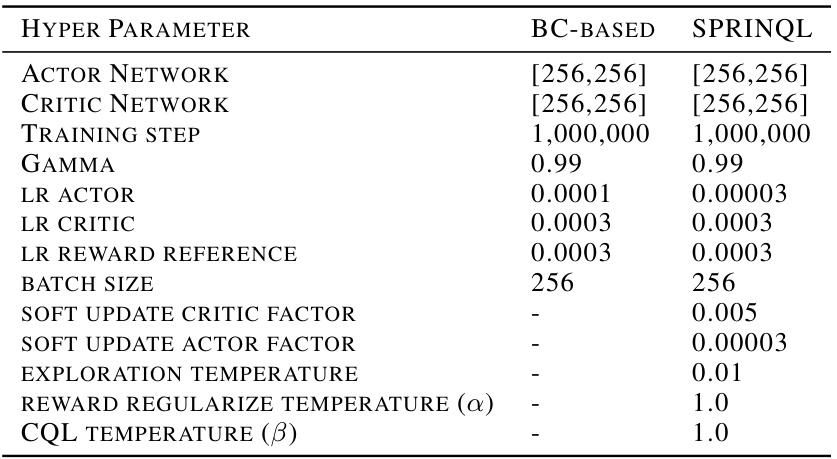

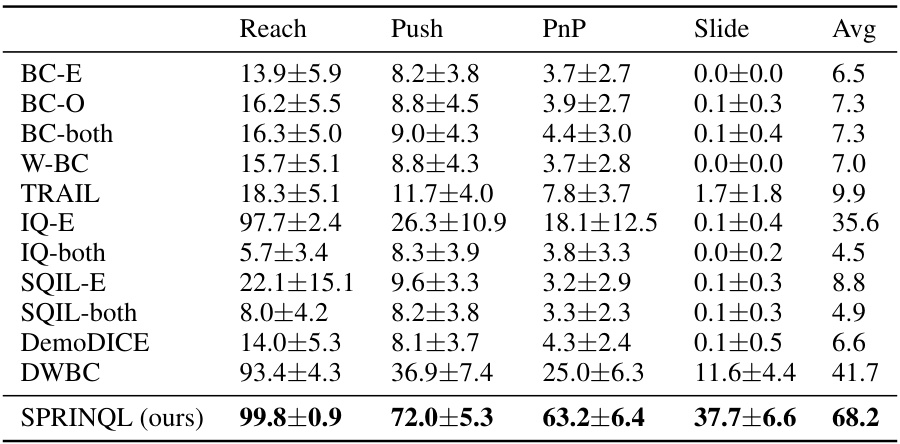

This table presents a comparison of the performance of SPRINQL against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) offline imitation learning algorithms and baselines across six different tasks. Three of the tasks are from the MuJoCo benchmark, and the other three tasks are from the Panda-gym benchmark. The table shows the average return achieved by each algorithm on each task, along with standard deviations. The results demonstrate that SPRINQL significantly outperforms the other algorithms in most cases.

In-depth insights#

Suboptimal IL#

Suboptimal imitation learning (IL) tackles the challenge of learning from imperfect or less-than-ideal demonstrations. Unlike traditional IL which relies on perfect expert demonstrations, suboptimal IL leverages data from various skill levels, including those significantly below expert performance. This approach is particularly relevant in real-world scenarios where obtaining many perfect expert demonstrations can be costly, time-consuming, or even impossible. The key advantage of suboptimal IL lies in its ability to significantly increase the amount of available training data, potentially leading to improved generalization and robustness. However, it introduces new difficulties. Suboptimal data introduces noise and biases into the learning process, potentially causing the learned agent to mimic undesirable behaviors. Effective suboptimal IL methods must carefully address these issues, often employing techniques like weighting schemes to prioritize better demonstrations or robust learning algorithms that are less susceptible to noise. The development of effective suboptimal IL algorithms is an active area of research crucial for bridging the gap between idealized IL settings and the complexities of real-world applications.

SPRINQL Algo#

The SPRINQL algorithm presents a novel approach to offline imitation learning by leveraging both expert and sub-optimal demonstrations. Its core innovation lies in formulating a convex optimization problem over the space of Q-functions, which contrasts with the often non-convex nature of existing methods. This convexity is achieved through a combination of techniques: inverse soft-Q learning, which offers advantages in handling sequential decision-making; learned weights that prioritize alignment with expert demonstrations while incorporating sub-optimal data; and reward regularization to prevent overfitting to limited expert data. The algorithm’s theoretical properties are thoroughly examined, establishing a lower bound on the objective function and guaranteeing the uniqueness of the optimal solution. Empirical evaluations demonstrate state-of-the-art performance on benchmark tasks, showcasing the efficacy of the SPRINQL algorithm in effectively learning optimal policies from diverse and limited demonstration data. The algorithm’s ability to handle multiple levels of sub-optimal expertise further enhances its practicality and robustness in real-world scenarios.

Convex Offline IL#

Offline imitation learning (IL) aims to train agents using pre-collected expert demonstrations without direct environment interaction. A key challenge is the limited size and coverage of expert data, often leading to suboptimal performance or overfitting. Convex Offline IL addresses this by formulating the IL problem as a convex optimization problem. This approach offers several advantages: guaranteed convergence to a unique solution, efficient algorithms, and avoidance of adversarial training often found in non-convex methods. Convexity simplifies the optimization process, allowing for the effective utilization of sub-optimal demonstrations in addition to expert data. The learned policy can be expected to balance mimicking expert trajectories while accounting for the larger, potentially noisy, dataset of sub-optimal behavior. This framework provides both a theoretically sound and practically efficient solution to the challenges of offline IL, paving the way for more robust and scalable imitation learning systems.

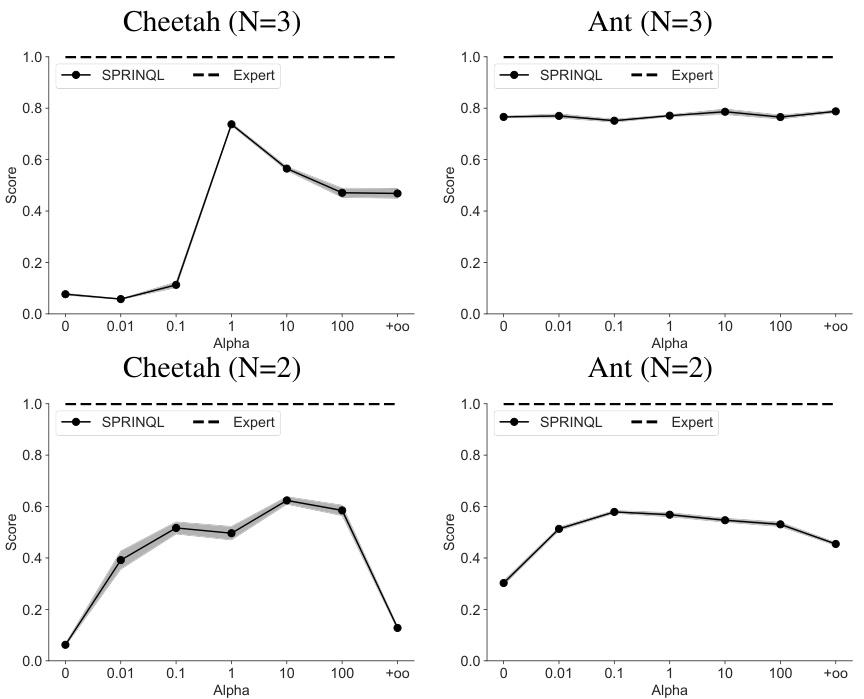

Reward Regularization#

Reward regularization is a crucial technique in offline imitation learning, addressing the challenge of limited expert demonstrations. By incorporating a regularization term, the algorithm biases the learned reward function towards expert-like behavior. This prevents overfitting to suboptimal demonstrations, which are often more abundant but less informative. The regularization term typically penalizes deviations from a reference reward, often derived from expert demonstrations or a pre-defined reward structure. Careful design of the regularization term is essential, balancing the influence of expert and sub-optimal data to effectively guide the learning process. Different approaches exist for constructing the reference reward, including methods based on occupancy measures or preference rankings of expert and suboptimal trajectories. The choice of regularization technique significantly impacts the performance and generalization capabilities of the learned policy. A well-designed reward regularization scheme can lead to significant improvements in the quality and efficiency of the imitated behavior, bridging the gap between scarce expert data and abundant suboptimal demonstrations.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on offline imitation learning with suboptimal demonstrations could involve several key areas. Improving robustness to noise and distribution shift in suboptimal data is crucial, possibly through more sophisticated weighting schemes or adversarial training methods. Another important area is developing theoretical guarantees for the performance of SPRINQL under varying data conditions, specifically concerning the impact of sample sizes and data quality on the learned policies. Exploring more complex scenarios with diverse levels of expertise or noisy demonstrations is essential to demonstrate the generalizability of the approach. This includes experimenting with datasets where the ordering of expert levels is not strictly hierarchical or where the transition dynamics between expert levels is highly varied. Finally, investigating the efficiency and scalability of SPRINQL for larger-scale problems and higher-dimensional state-action spaces is vital, perhaps through improved function approximation techniques or more efficient optimization algorithms. This could involve carefully selecting appropriate neural network architectures or using more efficient convex optimization methods, potentially utilizing techniques from online convex optimization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

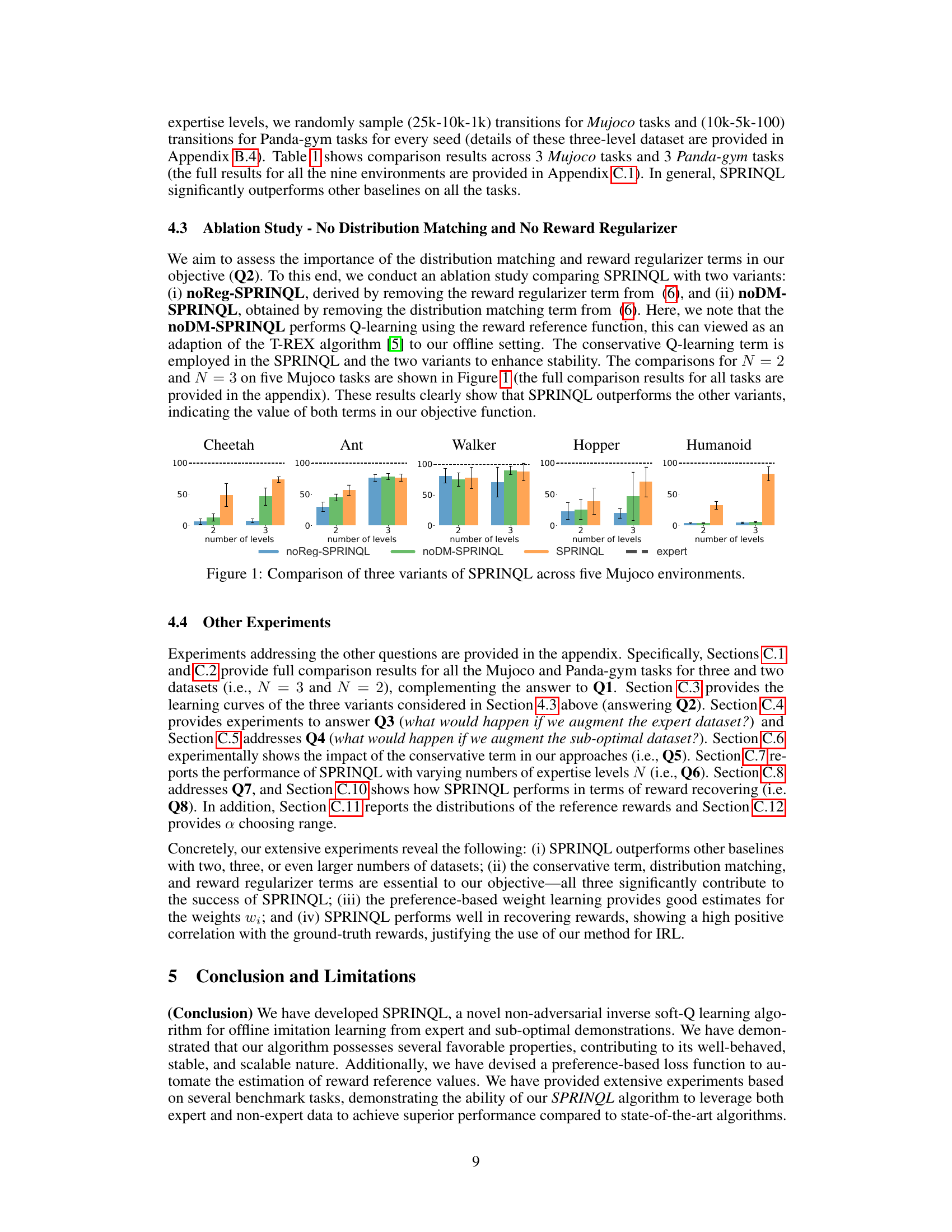

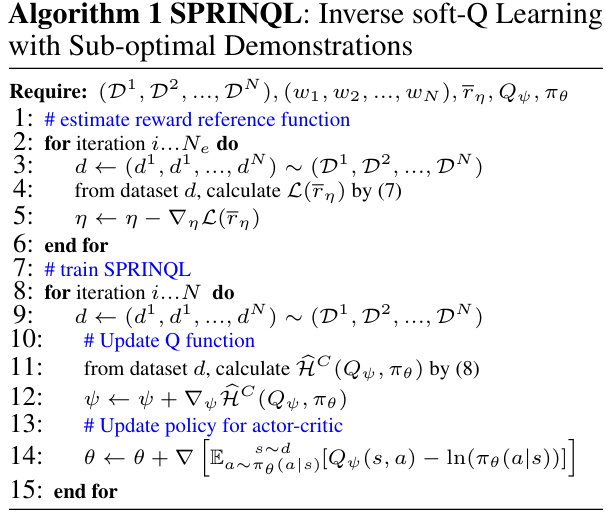

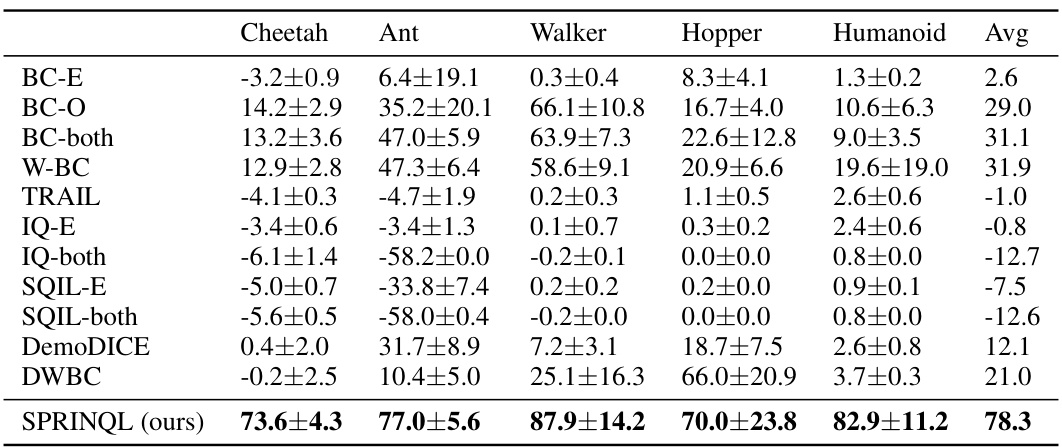

This figure presents a flowchart illustrating the overall architecture of the SPRINQL algorithm. It outlines the key steps involved, including reference reward training using expert and sub-optimal demonstrations, weight learning for the different expertise levels, Q-function training, and policy training. The diagram shows the interactions and dependencies between these components, highlighting the flow of information and updates during the learning process. The boxes and arrows visually represent the different modules and their interconnections.

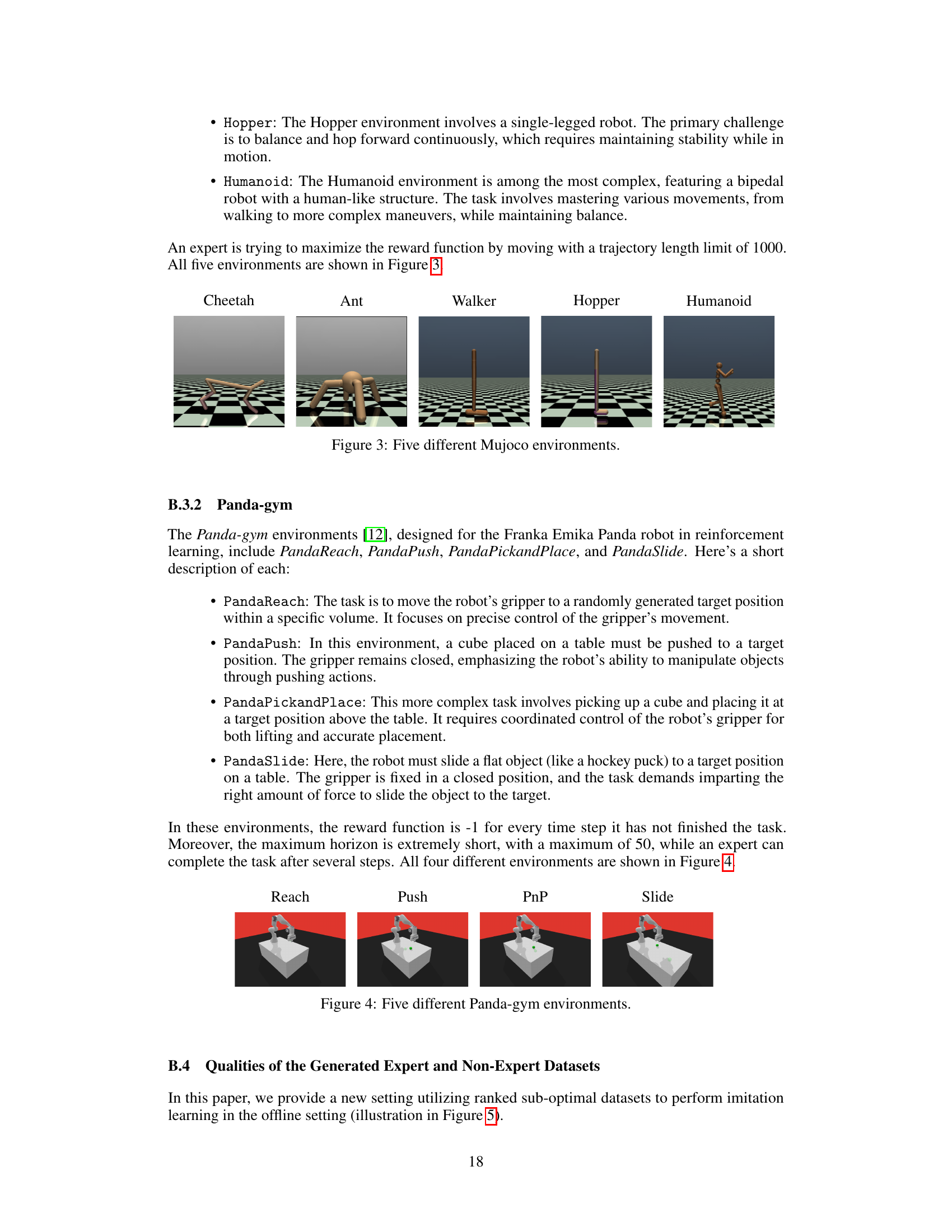

This figure shows the five different MuJoCo environments used in the experiments of the paper. These environments are HalfCheetah, Ant, Walker2d, Hopper, and Humanoid. Each environment simulates a different type of robot, with varying degrees of complexity and control challenges. The images depict a visual representation of each robot within its simulated environment.

This figure shows four different robotic arm manipulation tasks from the Panda-gym environment. Each task involves a different manipulation goal: Reach (moving the gripper to a target position), Push (pushing a cube to a target location), Pick and Place (picking up a cube and placing it at a target location), and Slide (sliding a puck to a target position). The images show the robotic arm and the object(s) being manipulated in the task.

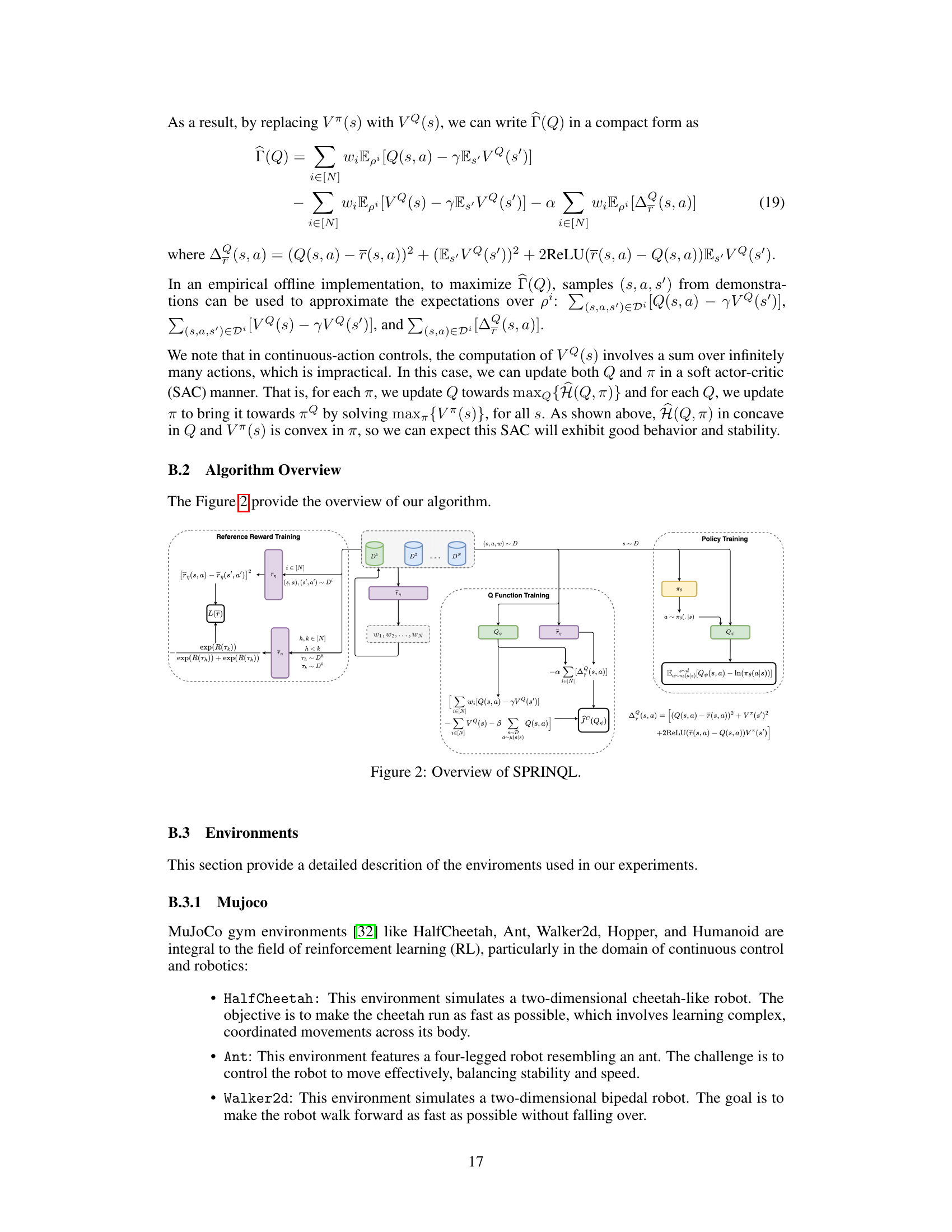

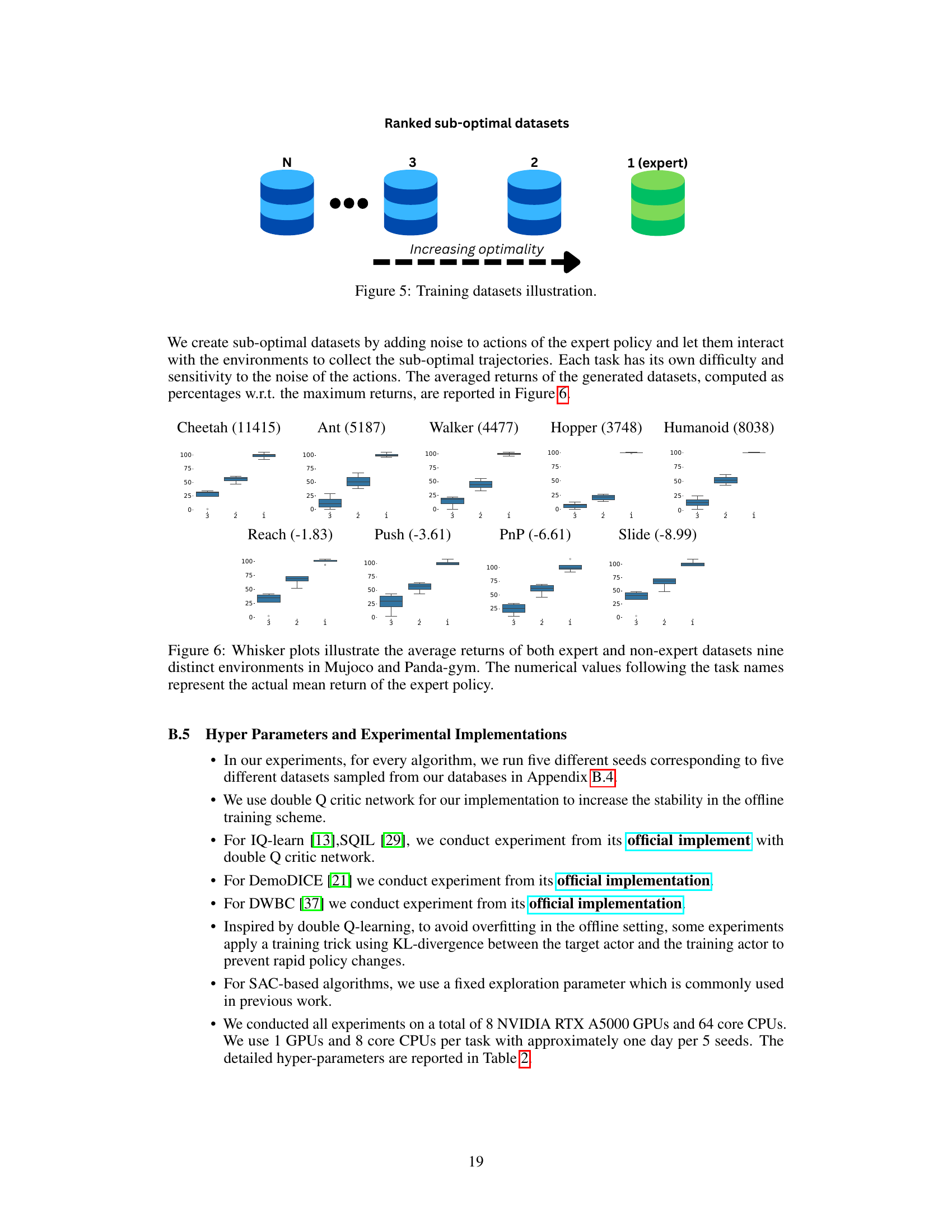

This figure illustrates the structure of the datasets used in the training process. The datasets are grouped by levels of expertise, ranging from N levels of sub-optimal demonstrations to a single expert dataset. The sub-optimal datasets are arranged in decreasing order of optimality, leading up to the expert dataset. This setup allows the model to learn from a diverse range of demonstrations, leveraging the abundance of sub-optimal data while prioritizing alignment with expert behavior.

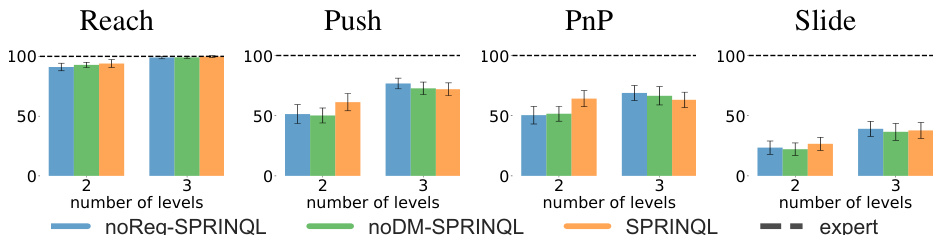

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm across five different MuJoCo environments. The three variants are: SPRINQL (the full model), noReg-SPRINQL (without reward regularization), and noDM-SPRINQL (without distribution matching). The results show the average return of the algorithm across multiple random seeds for each environment. The figure helps to illustrate the importance of both distribution matching and reward regularization in achieving state-of-the-art performance with the SPRINQL algorithm.

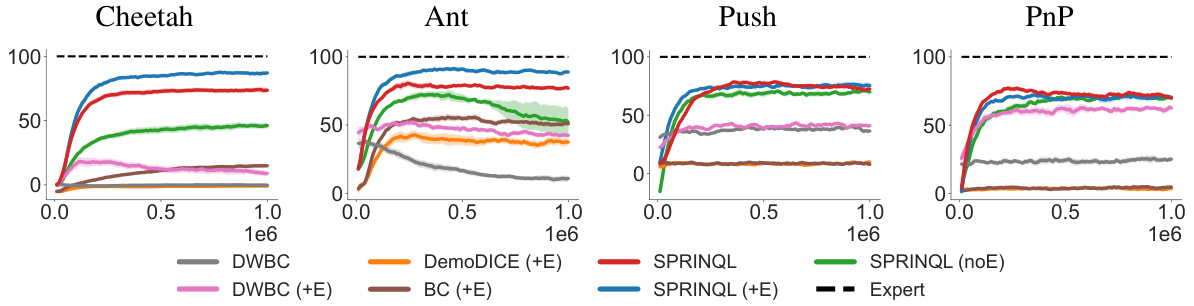

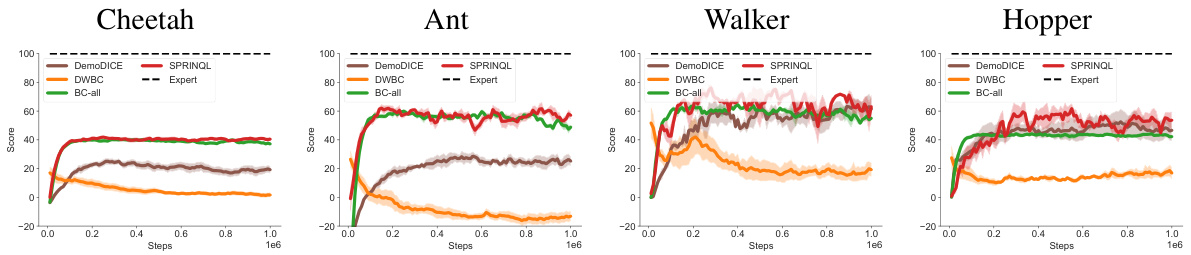

This figure compares the learning curves of several offline imitation learning algorithms on various MuJoCo and Panda-gym tasks. The algorithms compared include DWBC, Weighted-BC, BC, DemoDICE, and SPRINQL. The plot shows the learning progress of each algorithm over a million training steps, and how they compare to the performance of an expert. The x-axis shows the number of training steps (iterations), and the y-axis shows the normalized average returns of the agents. This illustrates how each algorithm’s policy converges to the expert’s performance. The shaded regions represent the standard error of the mean across multiple runs.

This figure presents the results of an ablation study comparing three variants of SPRINQL across four Panda-gym environments. The three variants are: noReg-SPRINQL (without reward regularization), noDM-SPRINQL (without distribution matching), and SPRINQL (with both reward regularization and distribution matching). The results show that SPRINQL outperforms the other two variants, indicating the importance of both reward regularization and distribution matching for improving the performance of SPRINQL. The results are shown as bar charts for each environment and each variant, with error bars representing the standard deviation.

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm across five different MuJoCo environments. The three variants are: SPRINQL (the complete algorithm), noReg-SPRINQL (without the reward regularization term), and noDM-SPRINQL (without the distribution matching term). The performance is measured as the average return over five different random seeds. The figure shows that SPRINQL consistently outperforms the other two variants across all environments, demonstrating the importance of both the reward regularization and distribution matching terms.

The figure shows the learning curves for SPRINQL and other baselines across multiple MuJoCo and Panda-gym environments using two datasets. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis shows the average return. The plot illustrates the training progress and performance of different algorithms over time, comparing SPRINQL to other state-of-the-art methods.

This figure shows the learning curves of several algorithms including SPRINQL and baselines across five Mujoco tasks and four Panda-gym tasks when only two datasets are used (one expert and one sub-optimal dataset). The x-axis represents the number of training steps and the y-axis shows the performance (normalized score). The results demonstrate the superior performance of SPRINQL compared to other algorithms, especially in reaching higher scores more quickly.

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm against a baseline of expert performance across five MuJoCo environments. The three variants are: SPRINQL (the full model), noReg-SPRINQL (removing the reward regularization term), and noDM-SPRINQL (removing the distribution matching term). The results show that SPRINQL consistently outperforms the other variants across all environments, highlighting the importance of both distribution matching and reward regularization in the algorithm’s success.

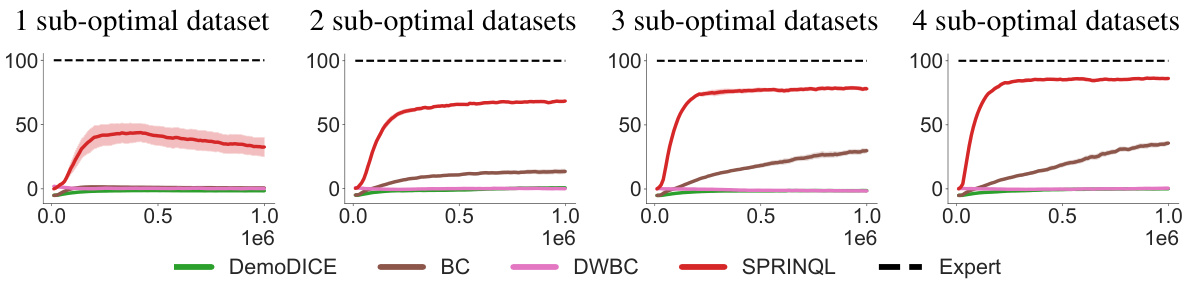

This figure shows the learning curves of different algorithms using different sizes of suboptimal datasets for several tasks. The x-axis shows the training steps, and the y-axis shows the normalized score. The different lines represent different algorithms: DWBC, BC, DemoDICE, SPRINQL, and Expert. The different subplots represent different tasks and datasets sizes.

This ablation study compares three variants of SPRINQL across four different environments (Cheetah, Ant, Push, PnP) from two domains (MuJoCo and Panda-gym). The variants are: noReg-SPRINQL (no CQL), noDM-SPRINQL (no CQL), noReg-SPRINQL, noDM-SPRINQL, SPRINQL (no CQL), and SPRINQL. The figure shows the impact of the conservative Q-learning (CQL) term on the performance of each variant. The expert performance is included as a baseline for comparison. The results indicate that the CQL term improves the performance of SPRINQL across different environments and domains.

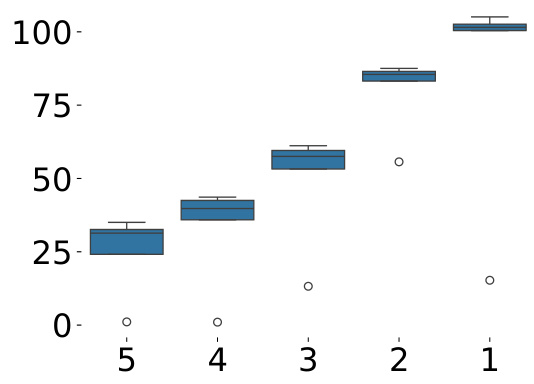

This figure shows the average returns for the HalfCheetah task using different numbers of sub-optimal datasets. It demonstrates the performance improvement with the increased number of sub-optimal datasets. The result shows that SPRINQL outperforms other algorithms in utilizing non-expert demonstrations.

The figure shows the average returns for the HalfCheetah datasets with varying numbers of sub-optimal datasets. It visually compares the performance of several algorithms (DemoDICE, BC, DWBC, SPRINQL) against an expert baseline as the number of sub-optimal datasets increases from 1 to 4. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the average return, showing how well each algorithm learns to perform the task under different data conditions.

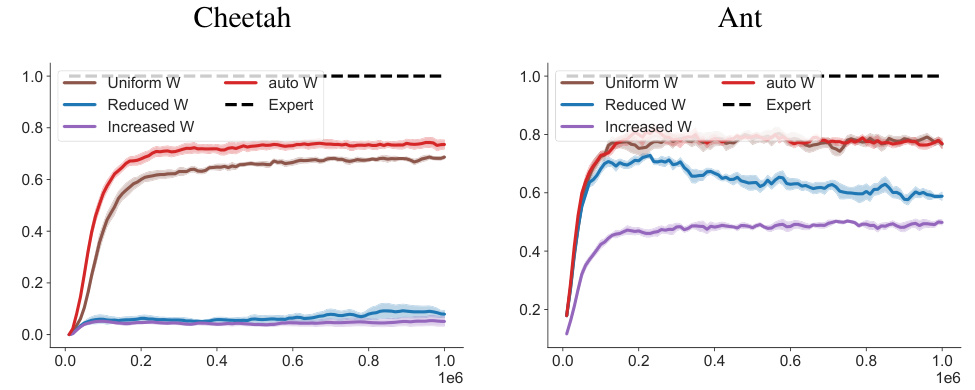

The figure compares the performance of SPRINQL using different weighting schemes for the datasets of varying expertise levels on two Mujoco environments, Cheetah and Ant. The weighting schemes include Uniform W (uniform weights), Reduced W (reduced weights for non-expert data), Increased W (increased weights for non-expert data), and auto W (weights automatically inferred by the preference-based method described in the paper). The results show that the automatically learned weights (auto W) achieve superior performance compared to other weighting schemes.

This figure shows the learning curves for different algorithms, namely DWBC, Weighted-BC, BC, DemoDICE, and SPRINQL, across five different environments. It compares the performance of these algorithms when trained with only expert data, and when trained with both expert and sub-optimal data. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, while the y-axis represents the normalized score. The figure helps to visualize the convergence behavior of each algorithm and to compare their performance under different training conditions.

This figure compares the recovered rewards with the true rewards across five MuJoCo environments. The three algorithms (noReg-SPRINQL, noDM-SPRINQL, and SPRINQL) are shown for each task (Cheetah, Ant, Walker, Hopper, Humanoid). Each plot shows a scatter plot of the true return against the predicted return for a specific environment and algorithm. The plots visualize the performance of each algorithm in estimating the reward function.

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm across five different MuJoCo environments: Cheetah, Ant, Walker, Hopper, and Humanoid. Each bar represents the average return of an algorithm variant. The algorithms compared are the full SPRINQL model, a version without the distribution matching term (noDM-SPRINQL), and a version without the reward regularization term (noReg-SPRINQL). The figure helps visualize the contributions of these two components to the algorithm’s overall effectiveness. The expert performance is also shown as a benchmark.

This figure compares the performance of three variants of the SPRINQL algorithm across five different MuJoCo environments. The variants are: SPRINQL (the full algorithm), noReg-SPRINQL (without reward regularization), and noDM-SPRINQL (without distribution matching). The results show that the complete SPRINQL algorithm outperforms the other variants, highlighting the value of both distribution matching and reward regularization.

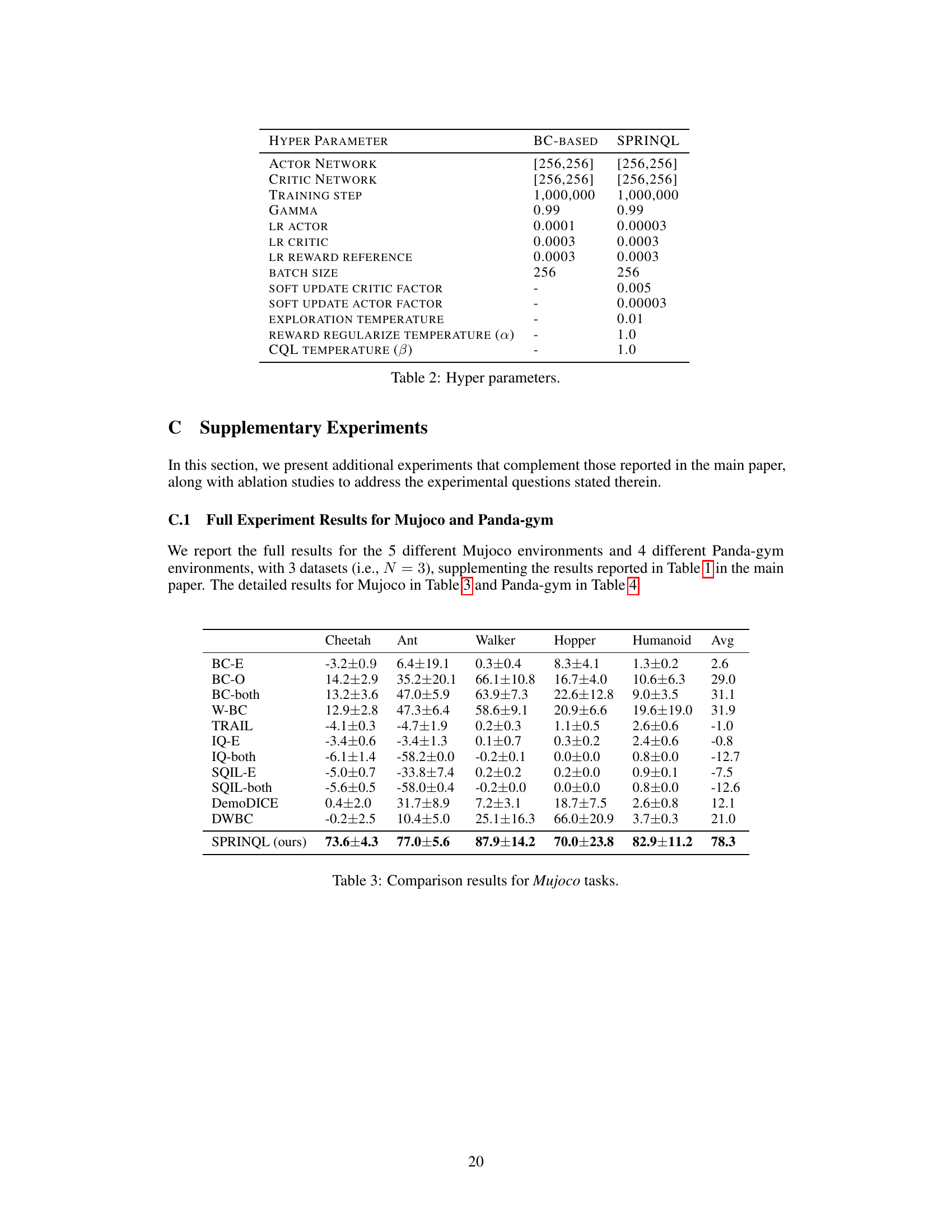

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the performance of SPRINQL against various baseline methods across six different robotic control tasks. Three tasks are from the MuJoCo benchmark (Cheetah, Ant, Humanoid), and three are from Panda-gym (Push, PnP, Slide). The table shows the average return achieved by each method, expressed as a percentage of the expert’s performance. Higher scores indicate better performance.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of SPRINQL against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) offline imitation learning algorithms across six different benchmark tasks. Three of the tasks are from the MuJoCo suite (Cheetah, Ant, Humanoid), and the other three are from Panda-gym (Push, PnP, Slide). For each task, the table shows the average return achieved by each algorithm, along with standard deviation. The results highlight the superior performance of SPRINQL, compared to various baselines including behavioral cloning with different datasets and other SOTA methods.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of SPRINQL against several baseline and state-of-the-art offline imitation learning algorithms across six different tasks (three from MuJoCo and three from Panda-gym). The results show average return scores (with standard deviations) for each algorithm on each task. The average return is normalized by the expert return and expressed as a percentage. The table highlights the superior performance of SPRINQL compared to other methods.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of SPRINQL against several state-of-the-art offline imitation learning algorithms across six benchmark tasks (three MuJoCo and three Panda-gym tasks). The results show the average return of each algorithm across multiple trials, demonstrating SPRINQL’s superior performance compared to baselines.

This table presents a comparison of different reinforcement learning algorithms’ performance on five MuJoCo tasks, using only two datasets: one expert and one sub-optimal. The results are shown as the average return across five seeds. The table highlights the performance of SPRINQL against baselines such as BC (Behavioral Cloning), W-BC (weighted BC), DemoDICE, and DWBC. The results showcase SPRINQL’s superior performance across multiple tasks.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various imitation learning algorithms on Panda-gym tasks. Specifically, it shows the average scores achieved by each algorithm when trained with two datasets: one containing expert demonstrations and the other containing sub-optimal demonstrations. The algorithms compared include BC, W-BC, DemoDICE, DWBC, and SPRINQL. The table helps to demonstrate the superior performance of SPRINQL in this setting.

Full paper#