↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training robots to perform diverse tasks is challenging due to the high cost and time involved in data acquisition. Existing multi-task learning methods often struggle with limited data, yielding suboptimal results. This paper focuses on improving the efficiency of multi-task learning in robotics, particularly in data-scarce scenarios.

The researchers introduce BAKU, a novel transformer-based architecture meticulously designed to leverage available data effectively. BAKU incorporates observation trunks, action chunking, multi-sensory observations, and action heads. Experiments on simulated and real-world robotic tasks demonstrate that BAKU substantially outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods, achieving significant performance gains with limited data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents BAKU, a novel and efficient transformer architecture for multi-task robot policy learning. It directly addresses the data scarcity problem in robotics by achieving high success rates with limited training data. This opens up new avenues for developing more generalist and adaptable robots, accelerating progress in real-world robotic applications. The findings also offer valuable insights into improving the efficiency of multi-task learning algorithms, potentially impacting other fields beyond robotics.

Visual Insights#

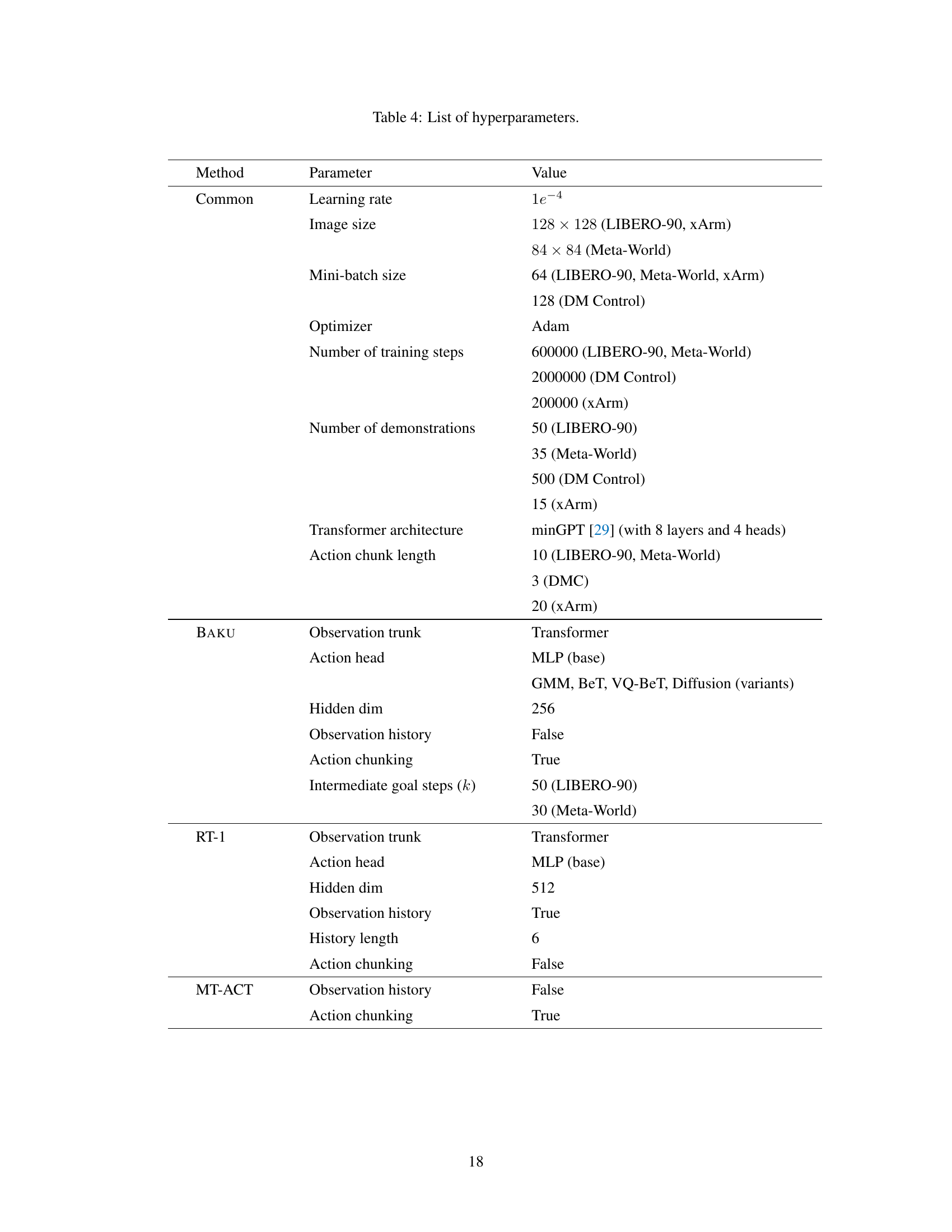

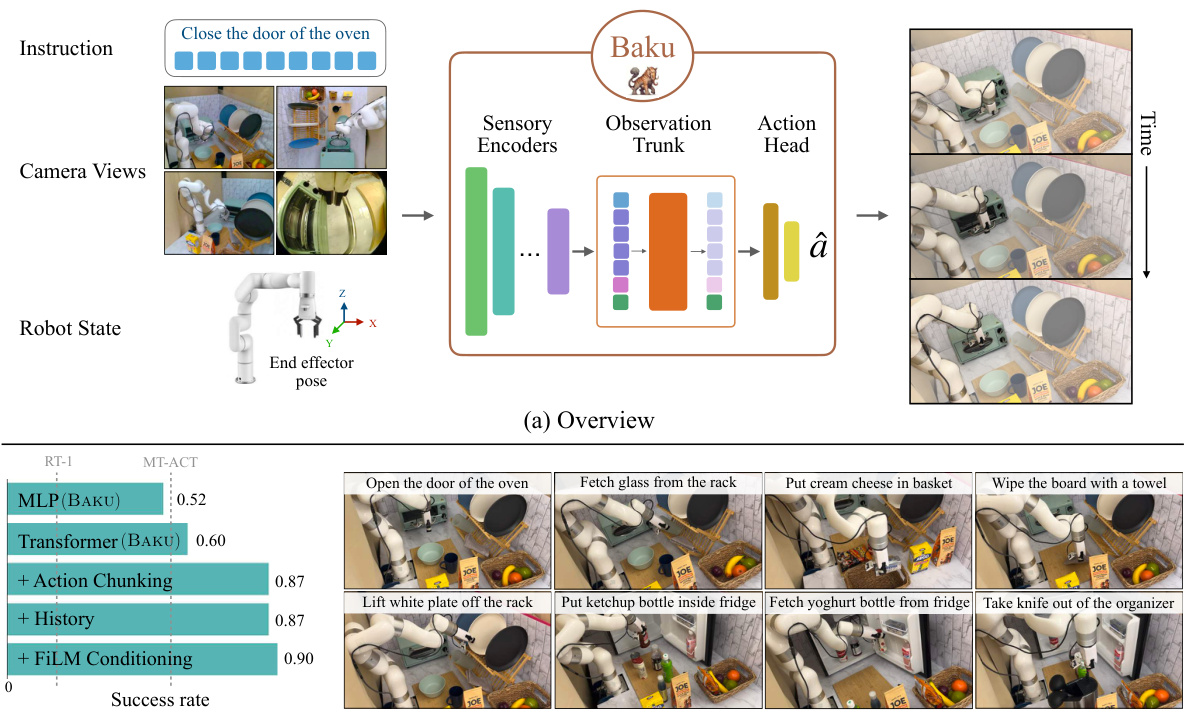

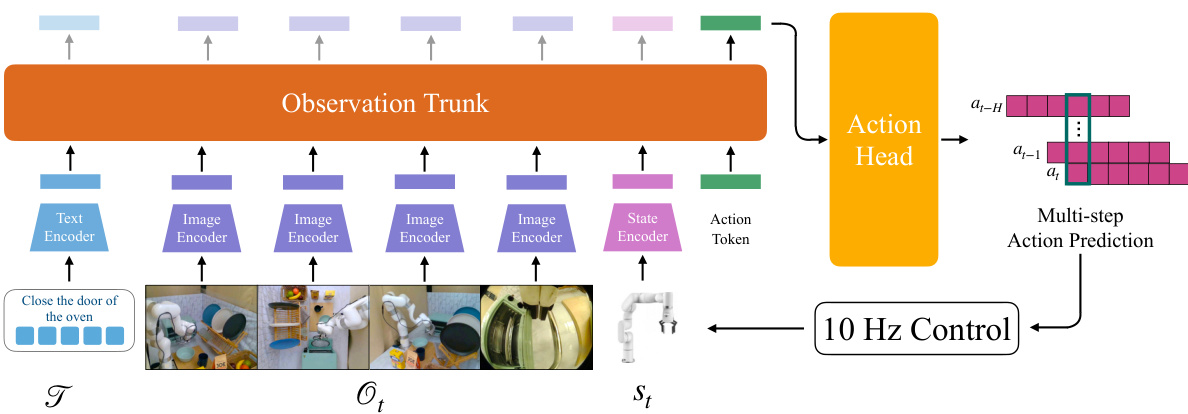

This figure provides a high-level overview of the BAKU architecture and demonstrates its performance on simulated and real-world tasks. Panel (a) shows the overall architecture, highlighting the modality-specific encoders, observation trunk, and action head. Panel (b) presents results on the LIBERO-90 benchmark, showcasing the impact of different design choices on multi-task performance. Finally, panel (c) illustrates the real-world application of BAKU on an xArm robot, demonstrating its ability to learn a single policy for 30 tasks with limited data.

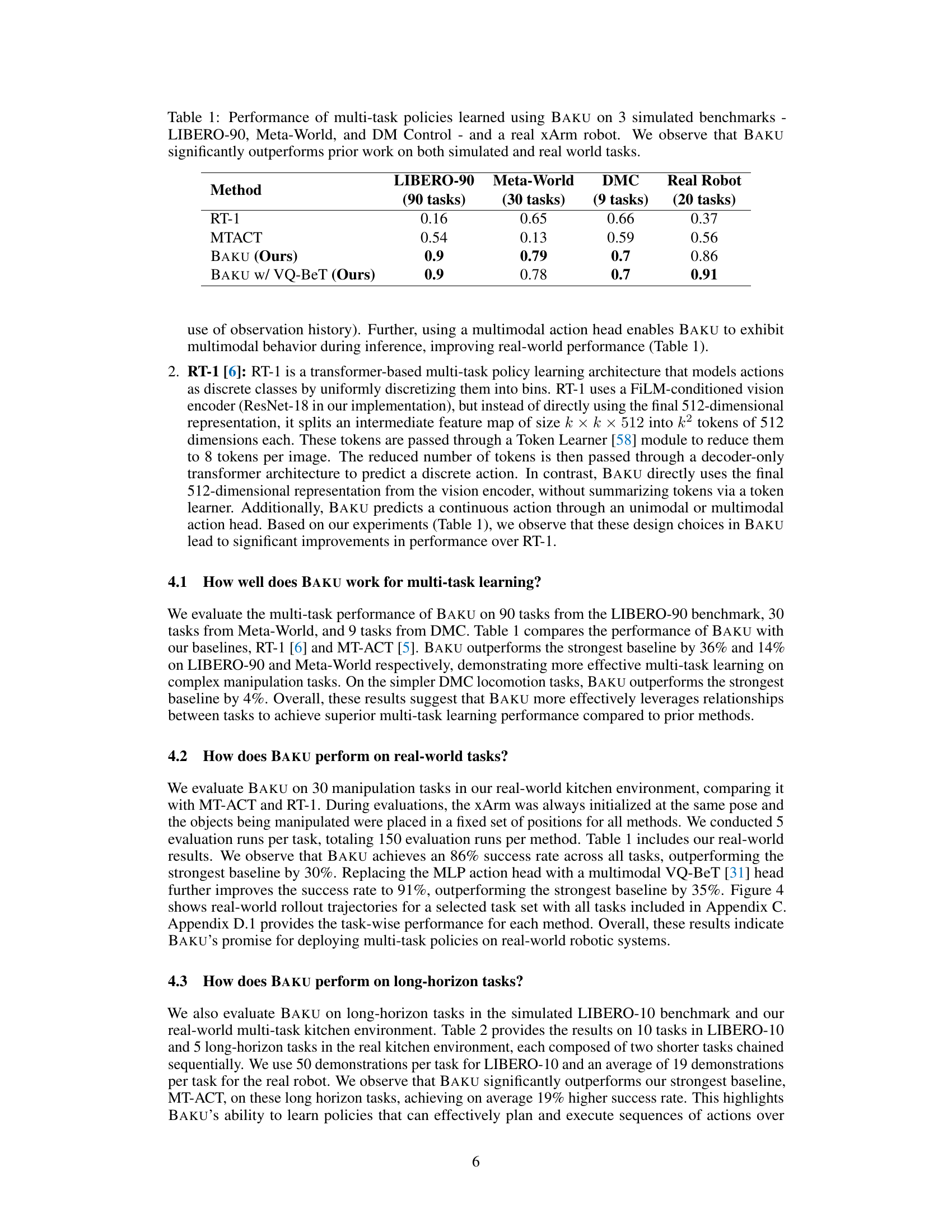

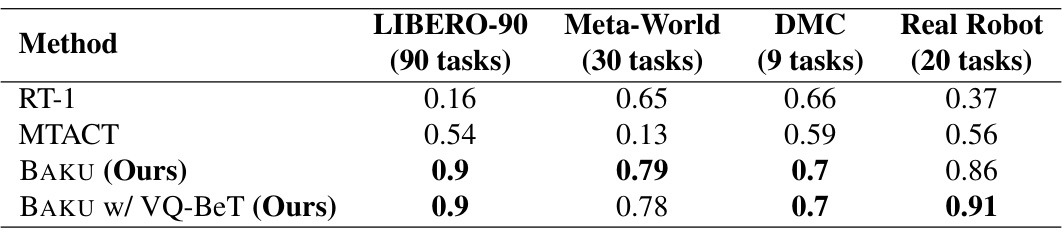

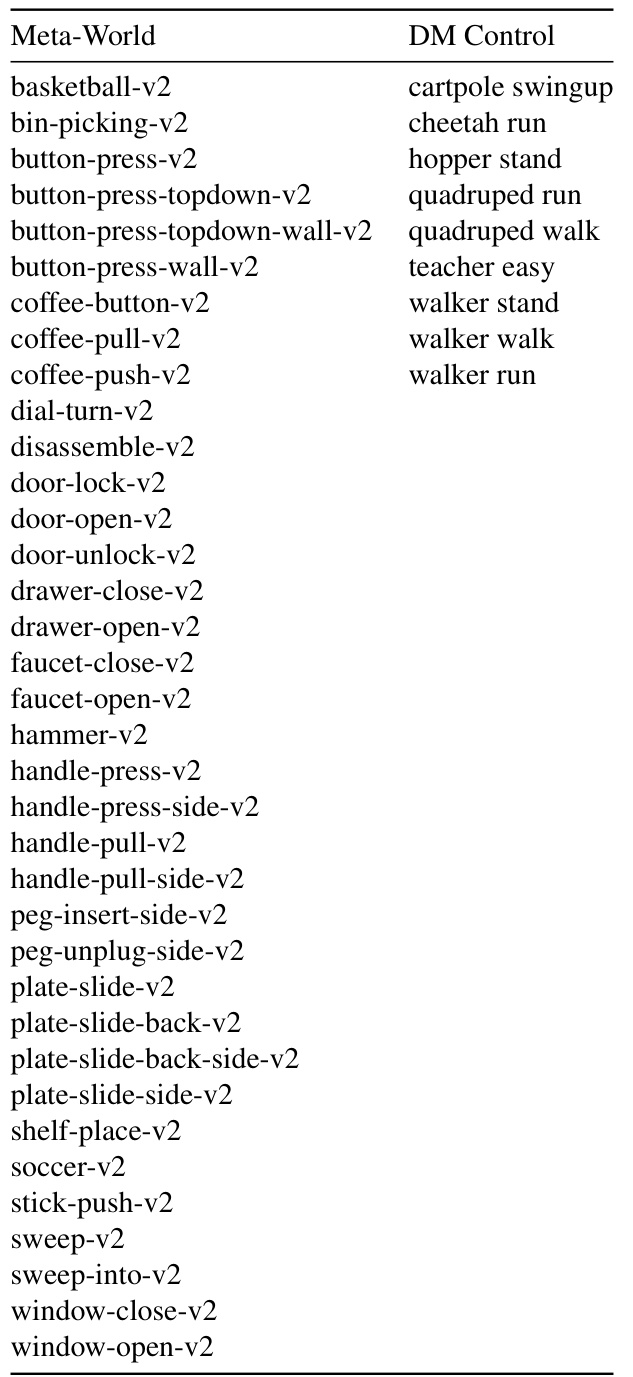

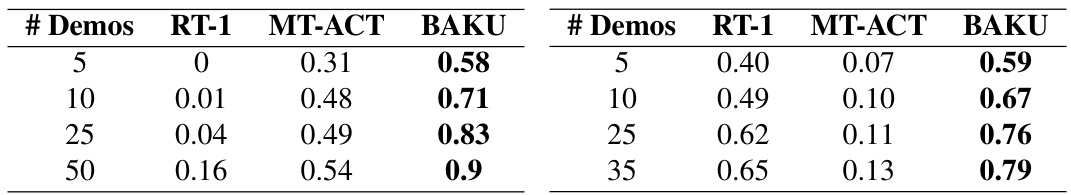

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different multi-task policy learning methods on four different benchmarks: LIBERO-90 (90 manipulation tasks), Meta-World (30 manipulation tasks), DeepMind Control (DMC, 9 locomotion tasks), and a real-world robotic manipulation tasks using a physical xArm robot (20 tasks). The methods compared are RT-1, MTACT, and BAKU (with and without VQ-BeT action head). The results show that BAKU achieves significantly better success rates than prior state-of-the-art methods, particularly on the more challenging benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

Multi-task Policy#

Multi-task policy learning seeks to develop agents capable of mastering diverse tasks, a significant challenge in robotics and AI. Data scarcity is a major hurdle, as acquiring sufficient expert demonstrations for each task is expensive and time-consuming. Existing single-task policies often outperform multi-task ones, highlighting the difficulty of effective generalization. The ideal multi-task policy would efficiently leverage available data across tasks, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities with minimal data per task. Effective architectures are crucial for achieving this, and several approaches exist, but finding the right balance between representation complexity, data efficiency, and the ability to adapt to different task contexts remains an ongoing area of research.

Transformer BAKU#

The proposed Transformer BAKU architecture represents a significant advancement in multi-task policy learning, particularly for data-scarce robotics applications. Its efficiency stems from a meticulous combination of observation trunks, action chunking, and multi-sensory input processing, which allows it to learn effectively from limited demonstrations. The use of a transformer encoder enables rich contextual understanding of observations across multiple modalities (vision, language, and proprioception), while the FiLM conditioning layer provides a mechanism for task-specific adaptation. The modular action head facilitates the integration of various state-of-the-art action generation models, allowing for flexible control strategies. Empirical results demonstrate substantial performance gains over existing methods in both simulated and real-world robotics tasks. BAKU’s effectiveness in data-scarce settings is especially valuable in robotics, where data acquisition is often expensive and time-consuming.

Sim-Real Transfer#

Sim-to-real transfer in robotics is a crucial yet challenging aspect of research, aiming to bridge the gap between simulated and real-world environments. A successful sim-to-real transfer approach needs to carefully address the domain gap, which arises from discrepancies in sensor readings, actuator dynamics, and environmental conditions. Effective techniques often involve data augmentation, domain randomization, and adversarial training. Data augmentation artificially expands the training dataset by modifying existing data, while domain randomization introduces variability in the simulation to make it more robust to real-world differences. Adversarial training utilizes a discriminator to identify differences between simulated and real data, enabling the policy to learn representations that are more invariant to these differences. Transfer learning strategies, leveraging knowledge from simulated data to improve real-world performance, are also frequently employed. However, a critical consideration is that no single method guarantees success, and the effectiveness of each technique depends heavily on the specific task and the level of similarity between the simulated and real environments. Thus, a holistic approach that combines multiple techniques to address the domain gap effectively often yields the best sim-to-real transfer results. Careful evaluation metrics are also essential to accurately assess the performance transfer and identify areas for further improvement.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically investigates the contribution of individual components within a model by removing them one at a time and evaluating the resulting performance. In the context of the provided research paper, such a study would likely focus on the transformer architecture’s different components such as multimodal sensory encoders (vision, proprioception, language), the observation trunk (MLP vs. Transformer), and the action head (MLP, GMM, BeT, VQ-BeT, Diffusion). By assessing performance changes after removing each component, the researchers gain crucial insights into each part’s impact on multi-task learning efficiency and overall performance. The key is to determine if a particular module significantly improves performance, justifying its inclusion, or if its effects are minimal, suggesting potential simplification of the model. Analyzing the results across diverse tasks (simulated and real-world) is essential. This would highlight whether a component’s value is consistent across various problem complexities or if it’s more task-specific. The study should also consider the interaction between components; removing one module might influence the effectiveness of others, adding another layer of insightful analysis. Ultimately, a well-executed ablation study provides evidence-based justification for the architecture’s design choices, showing its efficiency and effectiveness in solving multi-task robot control problems.

Future Work#

The research paper lacks a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section, however, based on the presented findings and limitations, several promising directions emerge. Extending BAKU’s capabilities to handle longer, more complex sequences of actions is crucial. Currently, BAKU demonstrates success in relatively short tasks. The ability to effectively chain multiple tasks together, a hallmark of true generalist agents, represents a significant improvement opportunity. Furthermore, investigating methods for handling tasks with varying degrees of complexity and precision is vital. BAKU showed some difficulty with high-precision tasks, and developing strategies for adaptive control or task decomposition would address this. Improving data efficiency is also a major goal. While BAKU excels given limited data, exploring techniques like meta-learning, transfer learning, and few-shot learning to further enhance its data efficiency and generalization capability across unseen tasks would be beneficial. Finally, a formal theoretical analysis of BAKU’s performance, including convergence properties, would provide stronger foundations for understanding its efficacy and enable more principled improvements. Developing more robust evaluation benchmarks that span a wide array of complex real-world tasks and include more comprehensive measures of performance (beyond success rates) would further strengthen the validation and application of the model. These key areas will inform the development of more powerful and reliable multi-task policy learning architectures in robotics.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows the architecture of BAKU, a multi-task policy learning model. It consists of three main components: 1. Sensory Encoders: Modality-specific encoders process inputs from different sources (text instructions, images from multiple camera views, and robot proprioceptive state). 2. Observation Trunk: The encoded information from the sensory encoders is combined in the observation trunk to create a unified representation. 3. Action Head: The action head takes the combined representation as input and predicts a chunk of future actions (multi-step action prediction). The output of the action head is used for closed-loop control at 10Hz in real-world experiments.

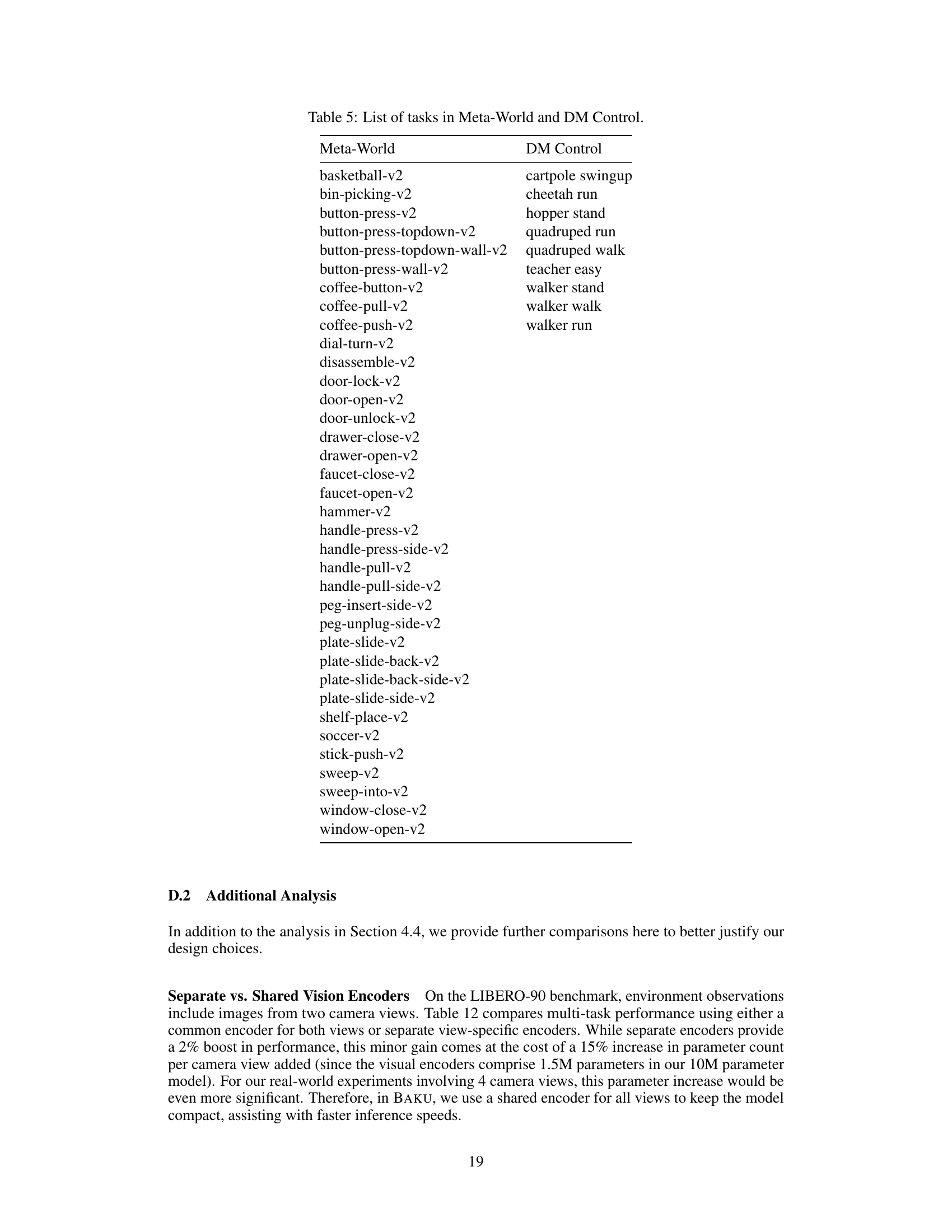

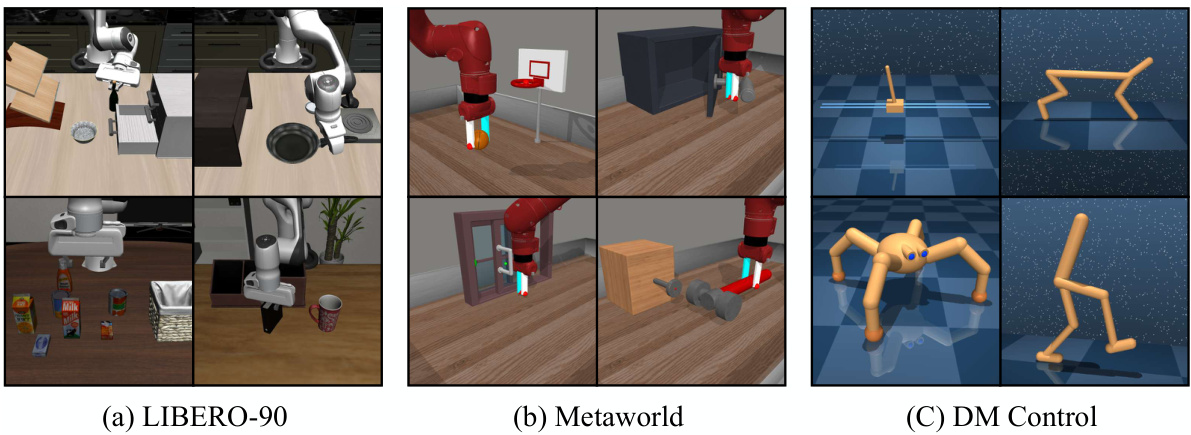

This figure shows three different simulated environments used to evaluate the BAKU model’s performance: LIBERO-90, Metaworld, and DeepMind Control. Each panel displays example scenes from each environment, showcasing the diversity of tasks involved in multi-task learning. The image highlights the variety of manipulation and locomotion tasks the agent must learn to perform in the experiments.

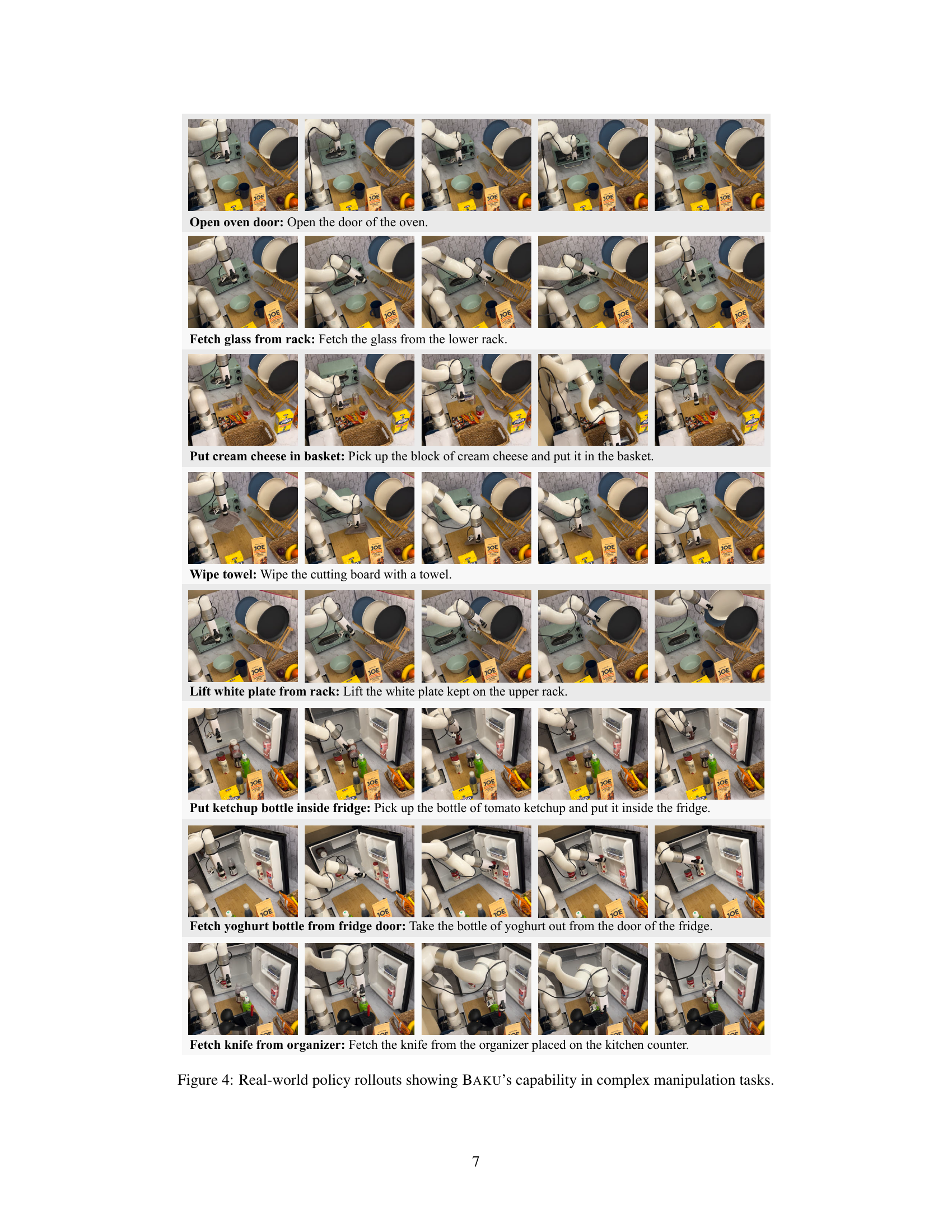

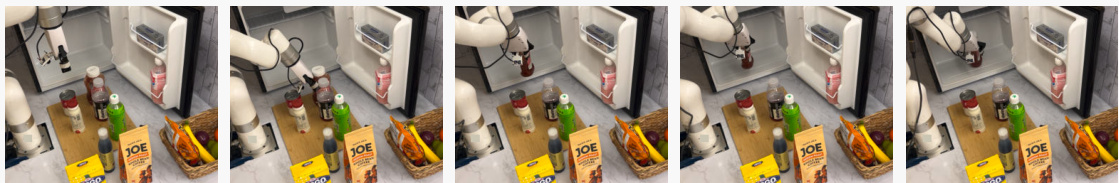

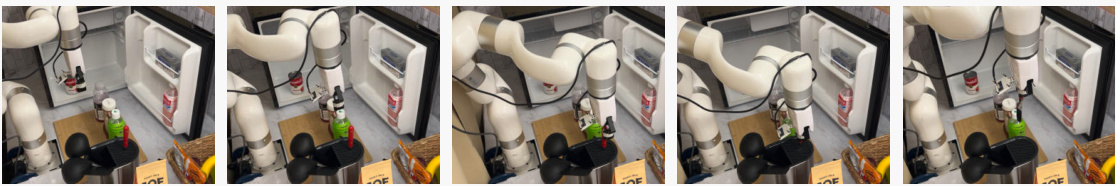

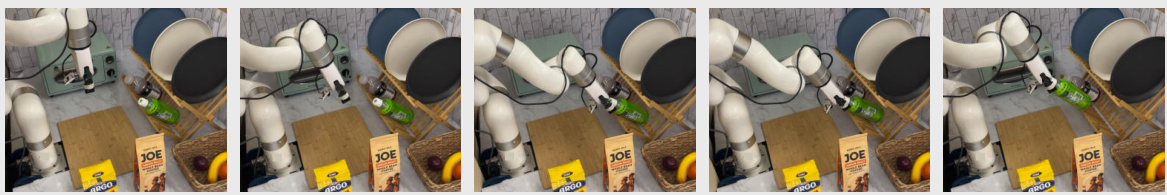

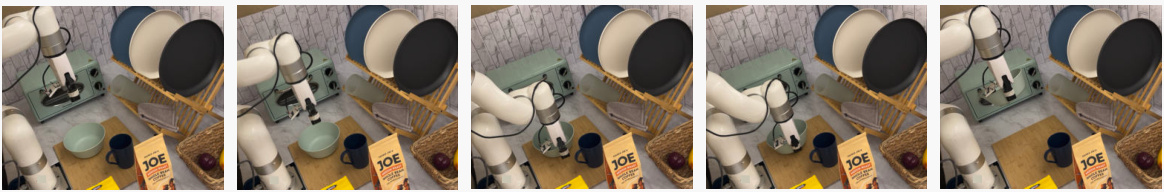

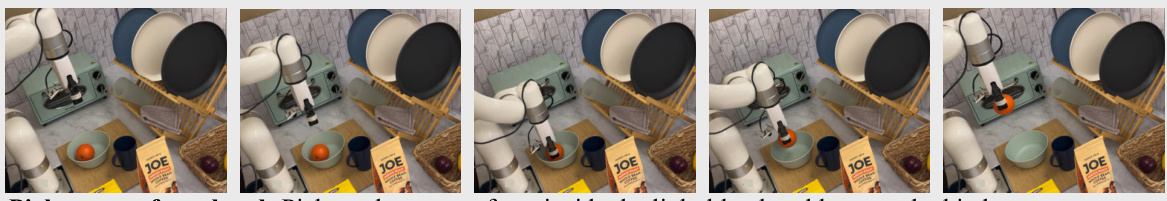

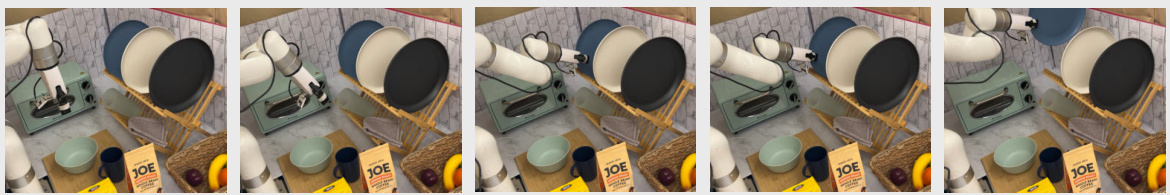

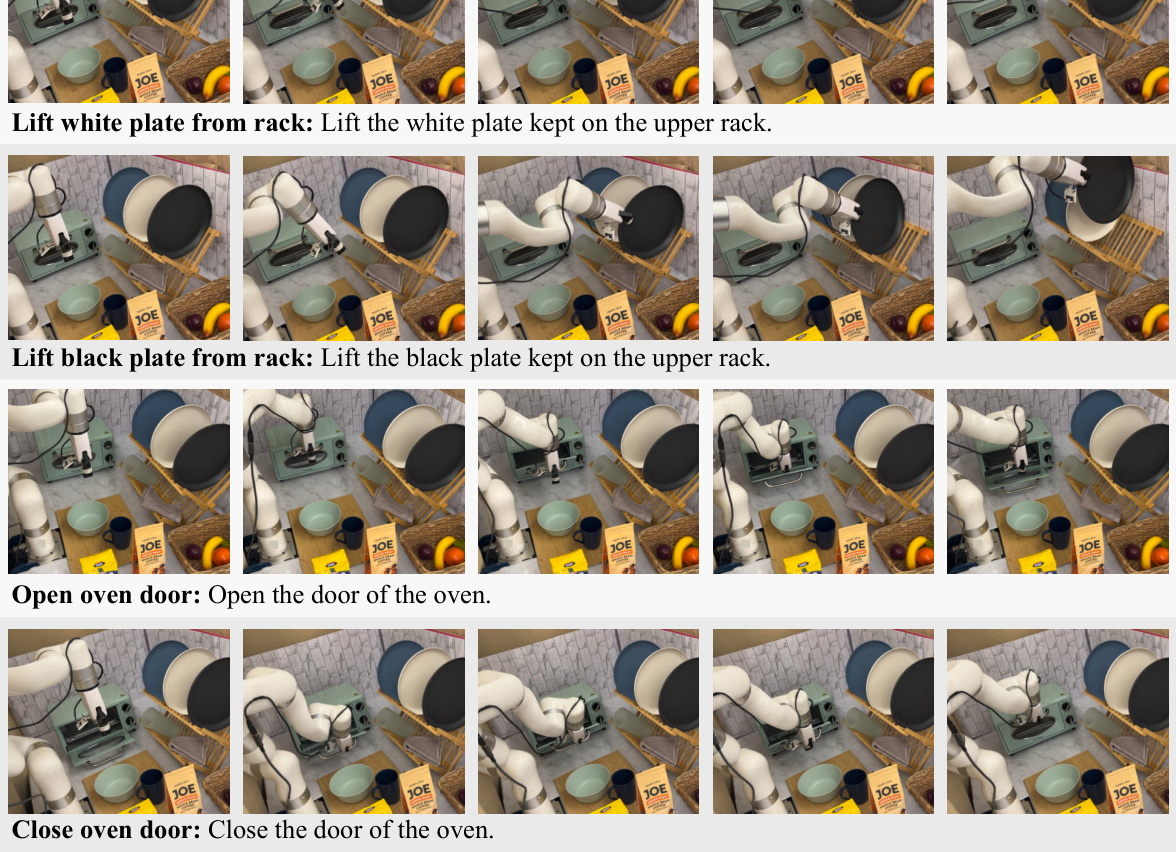

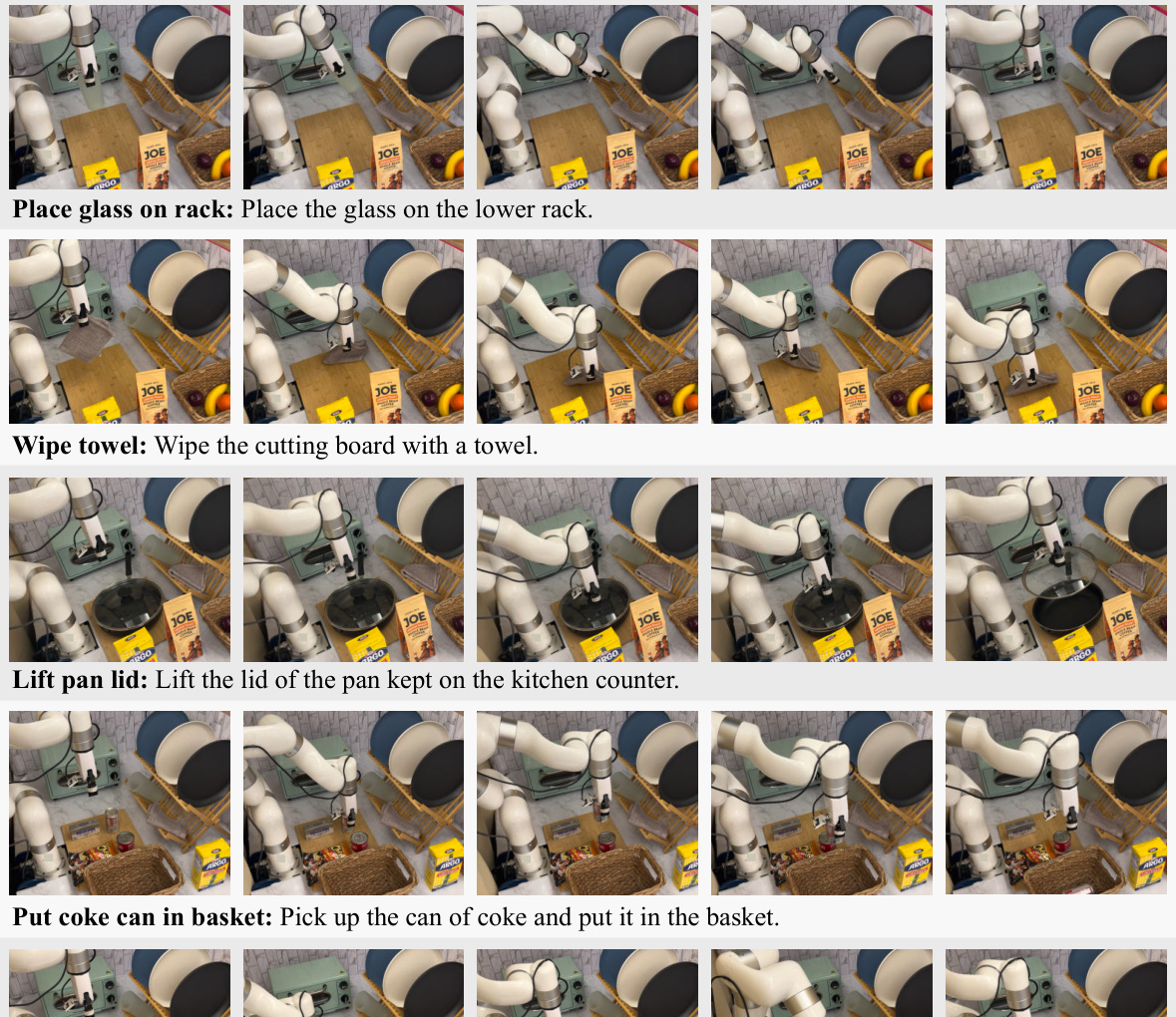

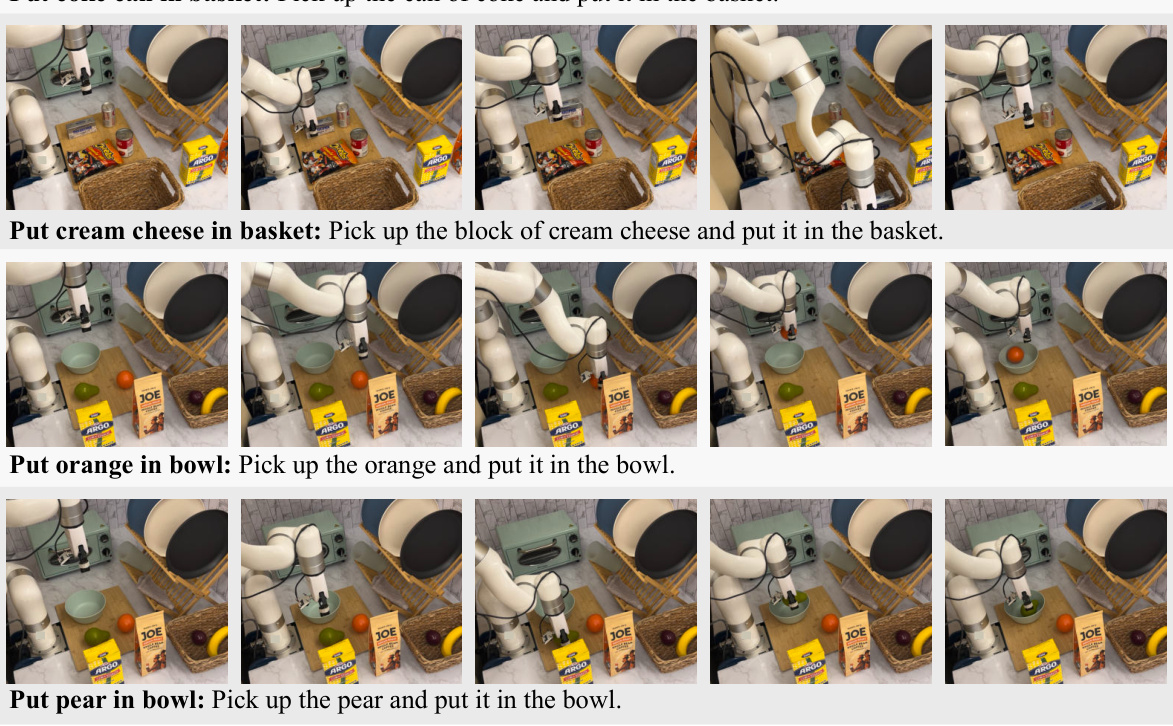

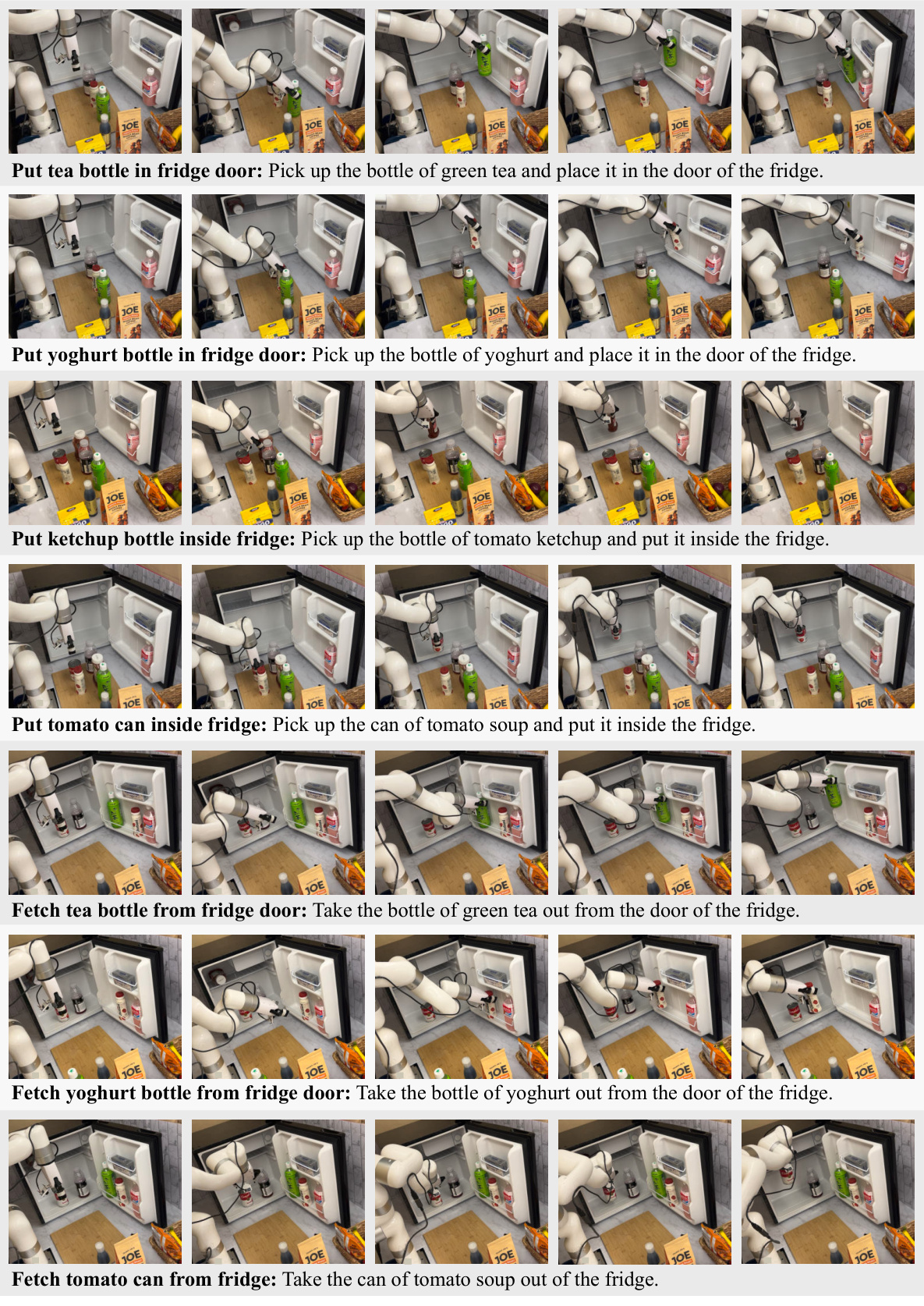

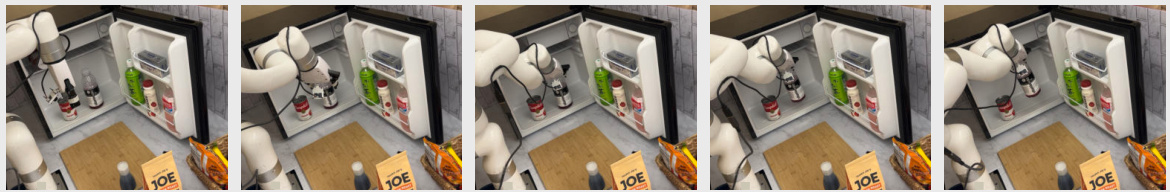

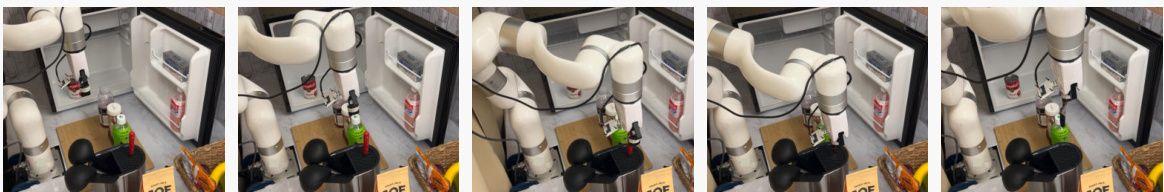

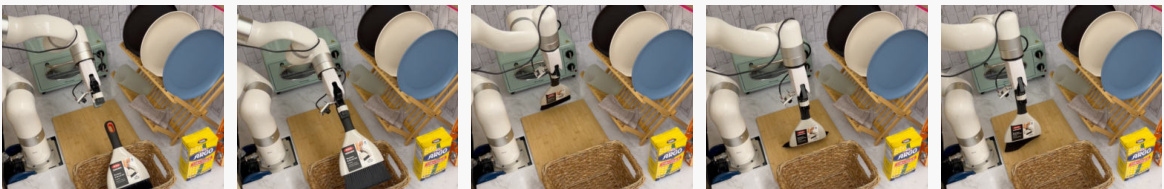

This figure shows the successful execution of eight different real-world manipulation tasks using BAKU. Each row represents a different task, with a sequence of images showing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks involve interacting with various objects like an oven, fridge, and kitchen utensils. The images highlight BAKU’s ability to handle complex manipulation, object recognition, and task completion.

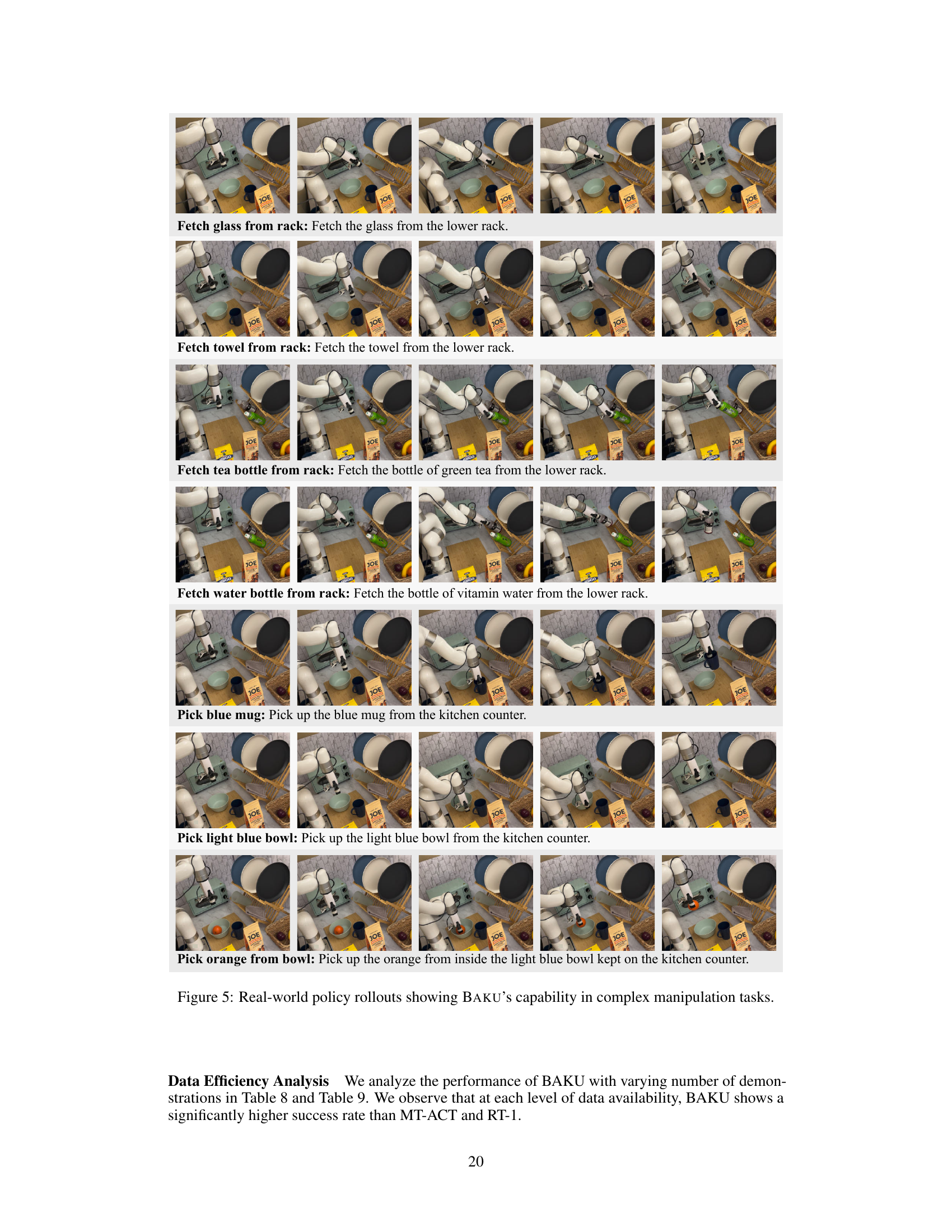

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each task involves multiple steps and requires precise manipulation of various objects in a kitchen setting. The images showcase BAKU’s ability to handle diverse tasks, including opening and closing the oven door, fetching various items from the rack and fridge, and placing items in the correct location. The successful completion of these complex tasks highlights BAKU’s efficient multi-task policy learning capabilities in a real-world environment.

This figure shows the successful execution of various complex manipulation tasks by the BAKU model in a real-world kitchen setting. Each row in the figure represents a different task involving multiple steps, such as opening the oven door, fetching objects from different locations, and placing objects in specific locations. The images in each row depict the progress of the robot arm as it performs each step of the task, showcasing its ability to handle diverse and complex manipulation scenarios effectively.

This figure shows eight example tasks from a set of 30 real-world manipulation tasks performed by the robot using BAKU. Each task involves a sequence of actions, such as opening the oven, fetching objects from different locations, and placing them in specific locations. The images show the robot’s actions at different stages during the execution of each task, demonstrating the robot’s ability to perform complex and multi-step operations successfully.

This figure shows eight example tasks from the 30 real-world tasks used to evaluate BAKU. Each row shows a different task, with the instruction at the beginning of each row and a sequence of images showing the robot executing the task. The tasks showcase BAKU’s ability to successfully manipulate objects such as opening and closing the oven door, fetching different items from shelves and the refrigerator, wiping a board with a towel, and placing items in a basket.

This figure shows a series of images depicting a robot arm performing various manipulation tasks in a kitchen setting. Each row represents a different task, with multiple images in each row showing the sequence of actions the robot takes to complete the task. The tasks include opening and closing an oven door, fetching objects from a rack and refrigerator, wiping a counter, and placing objects into a basket. The images demonstrate BAKU’s ability to successfully execute complex, multi-step manipulation tasks in a real-world setting.

This figure showcases eight example tasks from a set of 30 real-world manipulation tasks performed by the robot using the BAKU policy. Each row shows a sequence of images depicting the robot executing a specific task, highlighting the policy’s ability to handle various object interactions and environmental conditions. The tasks demonstrate a range of manipulation skills, including opening and closing containers, fetching objects from different locations, and placing objects in specific positions, emphasizing the multi-task nature and adaptability of the BAKU policy.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by the BAKU model. Each task involves a sequence of actions performed by the robot arm to achieve a specific goal, such as opening the oven, fetching objects from different locations, or placing objects in specific places within a kitchen environment. The images showcase the robot’s ability to execute complex and multi-step tasks while demonstrating both the visual input and the robot’s actions.

This figure shows eight example tasks from a set of 30 real-world manipulation tasks performed by the BAKU model. Each row shows a sequence of images capturing the robot’s actions to complete a single task. The tasks involve a variety of actions, including opening and closing the oven door, fetching objects from a rack or the fridge, placing items in a basket or fridge, wiping a board, and using tools like a knife. The figure illustrates BAKU’s ability to learn and execute complex, multi-step manipulation tasks successfully.

This figure shows eight example tasks from a set of 30 real-world tasks performed by the robot using the BAKU policy. Each task involves a sequence of actions to manipulate objects in a kitchen setting, demonstrating the policy’s ability to handle complex manipulation scenarios. The images show various stages of each task, illustrating the robot’s interaction with objects such as opening the oven, fetching items from racks, putting items in the fridge, and wiping the board. The success rate for these 30 real-world tasks was 91%.

This figure provides an overview of the BAKU architecture and showcases its performance on both simulated and real-world tasks. Panel (a) illustrates the overall architecture with modality-specific encoders, an observation trunk, and an action head. Panel (b) presents results on the LIBERO-90 benchmark, highlighting BAKU’s ability to learn a unified policy for many tasks. Finally, panel (c) shows the results of real-world experiments on the xArm robot, demonstrating BAKU’s effectiveness even with limited data.

This figure shows eight example tasks from the 30 real-world manipulation tasks performed by the BAKU model. Each row represents a different task, and shows a sequence of images capturing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks involve a variety of actions, including opening and closing drawers, moving objects between locations, using tools, and placing items in specific locations. This demonstrates the system’s ability to handle complex, multi-step tasks with diverse actions in a real-world setting.

This figure shows a series of images demonstrating the successful execution of various tasks by BAKU, a multi-task robot policy. Each row depicts a different task, showcasing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks involve a range of complex manipulation skills, including opening and closing the oven door, fetching items from different locations (racks, fridge), and putting items in specific places (basket, fridge). The images demonstrate the robot’s ability to understand and execute diverse, nuanced instructions.

This figure shows a series of images depicting the robot’s successful execution of various complex manipulation tasks in a real-world kitchen setting. Each row displays a different task, with a sequence of images showing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks are diverse, ranging from opening and closing an oven door to fetching objects from different locations and using tools like towels and a broom. The images demonstrate the robot’s dexterity and adaptability in performing these multifaceted manipulation actions successfully.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world robot manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each example shows a sequence of images illustrating the robot’s actions in completing a specific task, such as opening an oven door or fetching an object from a shelf. The figure demonstrates BAKU’s ability to handle diverse and complex manipulation tasks, highlighting its capabilities in a real-world setting.

This figure shows several example tasks from the real-world experiments performed using BAKU. Each row displays a sequence of images showing the robot’s actions for a particular task, starting from the initial state to the successful completion of the task. These tasks include opening and closing the oven door, fetching objects from various locations (rack, fridge, counter), putting items into containers, wiping the board with a towel, etc. The images illustrate BAKU’s ability to handle diverse manipulation challenges in a real-world kitchen setting.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each task involves multiple steps and object interactions. The images show the robot’s actions and the state of the objects at different time steps. The tasks include opening and closing the oven door, fetching different items from a rack or the fridge, and placing objects into specific locations. This illustrates BAKU’s ability to learn and execute a wide variety of complex, multi-step manipulation tasks in a real-world environment.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each task involves a sequence of actions and demonstrates the robot’s ability to perform various complex movements, such as opening and closing the oven door, fetching items from different locations, and placing items in specific locations. The images provide a visual representation of the robot’s actions and the environment it interacts with.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by the BAKU model. Each task involves multiple steps and requires the robot to interact with several objects in a kitchen setting. The images demonstrate BAKU’s ability to handle complex sequences of actions, adapt to various object positions and orientations, and execute precise movements, highlighting its proficiency in real-world scenarios.

This figure shows the robot’s performance on 8 out of 30 real-world tasks. Each row shows a different task, with a sequence of images capturing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks demonstrate the robot’s ability to perform various manipulation tasks including opening and closing the oven door, fetching objects from a rack and fridge, and placing objects in specific locations. The images illustrate the success of BAKU in handling complex, multi-step real-world scenarios.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each row depicts a different task, such as opening the oven door, fetching items from racks or the refrigerator, and placing objects in specific locations. The images in each row chronologically illustrate the robot’s actions, from its initial position to the successful completion of the task. The figure showcases BAKU’s ability to handle diverse and complex manipulation scenarios in a real-world kitchen setting.

This figure shows eight example tasks performed by BAKU in a real-world kitchen setting. Each task involves multiple steps, demonstrating the robot’s ability to perform complex manipulation tasks such as opening and closing an oven door, fetching items from different locations (e.g., racks, fridge), and placing items in specific locations. The images are snapshots of the robot’s actions during task execution. The diversity of tasks and actions highlights BAKU’s capacity for multi-task learning and generalization in a real-world environment.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each example consists of a sequence of images showing the robot arm’s interaction with various objects in a kitchen setting, illustrating its ability to perform complex actions such as opening and closing the oven door, fetching items from racks and shelves, and placing objects into containers. The captions under each sequence provide a brief description of the task being performed.

This figure shows eight example tasks performed by BAKU in a real-world kitchen setting. Each task involves a sequence of actions, demonstrating BAKU’s ability to handle complex manipulations such as opening the oven, fetching items from racks and the fridge, and placing objects into designated areas. The images provide a visual representation of the robot’s actions and the progression through each task.

This figure shows eight examples of successful real-world manipulation tasks performed by BAKU. Each task involves multiple steps and requires interaction with various kitchen objects. The images provide a visual representation of the robot’s actions at various stages of each task.

This figure shows a series of images demonstrating the robot’s successful completion of various manipulation tasks using a single multi-task policy learned by BAKU. Each row showcases a different task, with a sequence of images showing the robot’s actions from start to finish. The tasks include opening and closing an oven door, fetching objects from various locations, putting items in a basket or fridge, and wiping a surface. The images highlight BAKU’s ability to handle different object shapes, positions, and task complexities.

This figure shows the results of BAKU’s policy on 8 out of 30 real-world manipulation tasks. Each row displays a sequence of images showing the robot’s actions in a specific task. The tasks include opening and closing oven doors, fetching objects from different locations such as racks and fridges, wiping surfaces, and placing objects in designated places. The images provide a visual demonstration of BAKU’s ability to successfully complete complex manipulation tasks in a real-world setting.

This figure shows a series of images demonstrating the robot’s ability to perform various complex manipulation tasks in a real-world kitchen environment. The images are sequenced to show the steps involved in each task, such as opening and closing the oven door, fetching objects from the rack and fridge, and placing objects in their appropriate locations. These successful policy rollouts highlight BAKU’s efficiency and capability in complex, real-world scenarios.

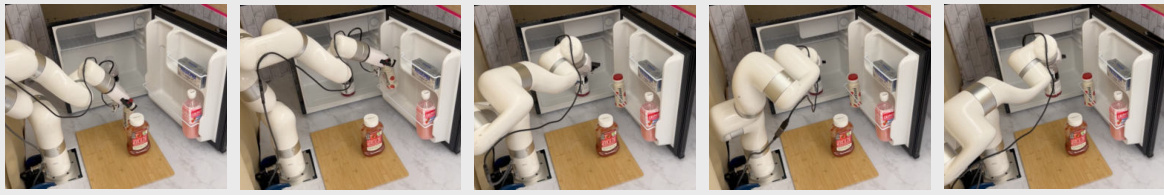

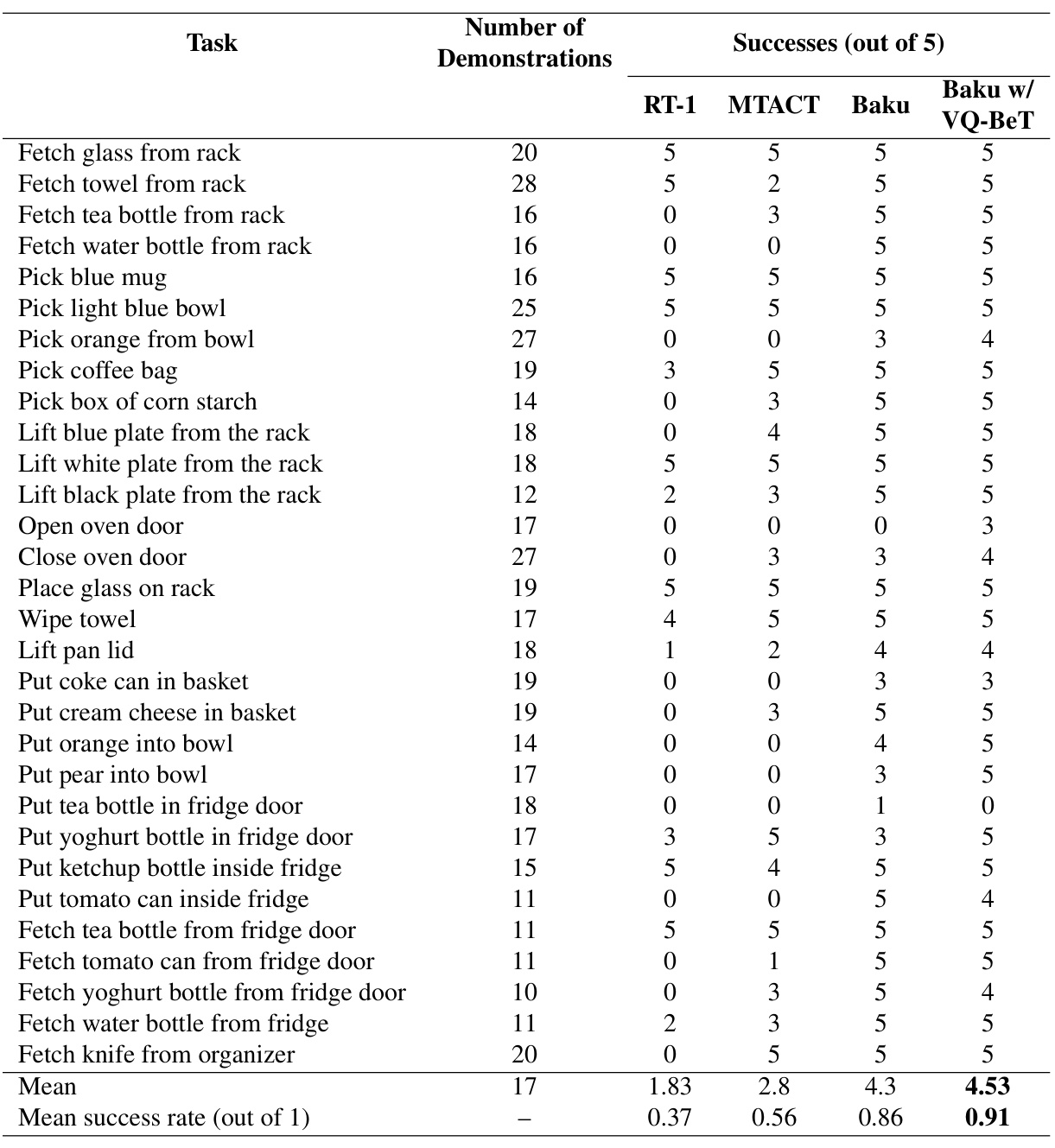

More on tables

This table presents the results of evaluating BAKU, compared to MT-ACT, on long-horizon tasks. Long-horizon tasks are made up of multiple shorter tasks chained sequentially. The results show success rates for both a simulated benchmark (LIBERO-10, with 10 tasks) and real-world tasks (5 tasks on a real xArm robot). BAKU demonstrates significantly higher success rates in both settings, highlighting its effectiveness in learning policies capable of executing longer sequences of actions.

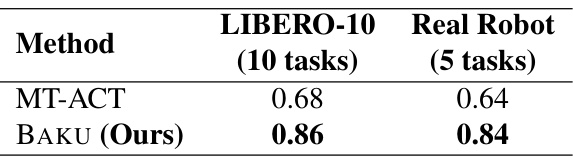

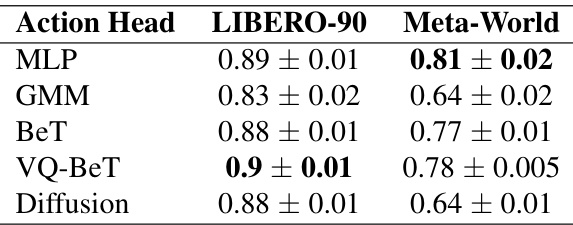

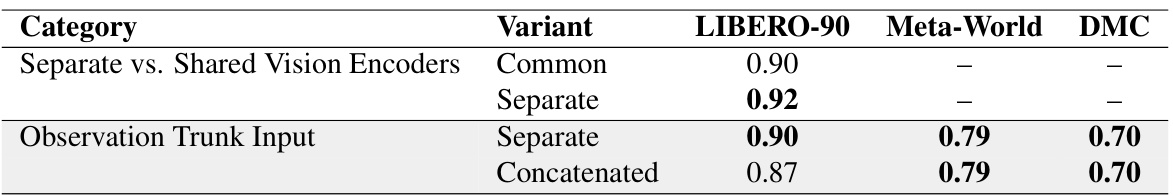

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the BAKU model to analyze the impact of various design choices on its multi-task performance. Different configurations of observation trunks, model sizes, action heads, goal modalities, and the use of action chunking, observation history, and task conditioning through FiLM are evaluated across three benchmark datasets (LIBERO-90, Meta-World, and DMC). The results provide insights into which components and properties are most important for effective multi-task learning.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of BAKU against state-of-the-art methods (RT-1 and MT-ACT) on four different benchmarks: LIBERO-90, Meta-World, DeepMind Control (DMC), and a real-world robot manipulation task using a physical xArm robot. For each benchmark, the table shows the success rate achieved by each method. The results demonstrate that BAKU significantly outperforms previous methods, achieving substantial improvements in success rate across all benchmarks, showcasing its effectiveness in multi-task policy learning.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of BAKU against two other state-of-the-art multi-task learning algorithms (RT-1 and MT-ACT) across four different sets of tasks. Three sets of tasks are simulated robotics tasks from the LIBERO-90, Meta-World, and DeepMind Control benchmark suites, and one set is from real-world robotic manipulation tasks using an xArm robot. The success rate is used as the performance metric in all four sets of experiments. The results show that BAKU outperforms both RT-1 and MT-ACT on all four experimental sets.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of BAKU against two state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods (RT-1 and MT-ACT) across four different sets of tasks. The first three sets of tasks are simulated benchmarks, while the fourth involves real-world robotic manipulation tasks on an xArm robot. The table shows success rates for each method across all the task sets, highlighting BAKU’s superior performance in both simulated and real-world scenarios.

This table presents the results of evaluating BAKU’s performance on five long-horizon tasks in a real-world kitchen environment. Each long-horizon task consists of multiple shorter tasks performed in sequence. The table shows the number of demonstrations provided for each task and the number of successful completions (out of 5 trials) for both MT-ACT and BAKU. The mean success rate across all tasks is also provided for both methods. This demonstrates BAKU’s ability to handle longer sequences of actions compared to MT-ACT.

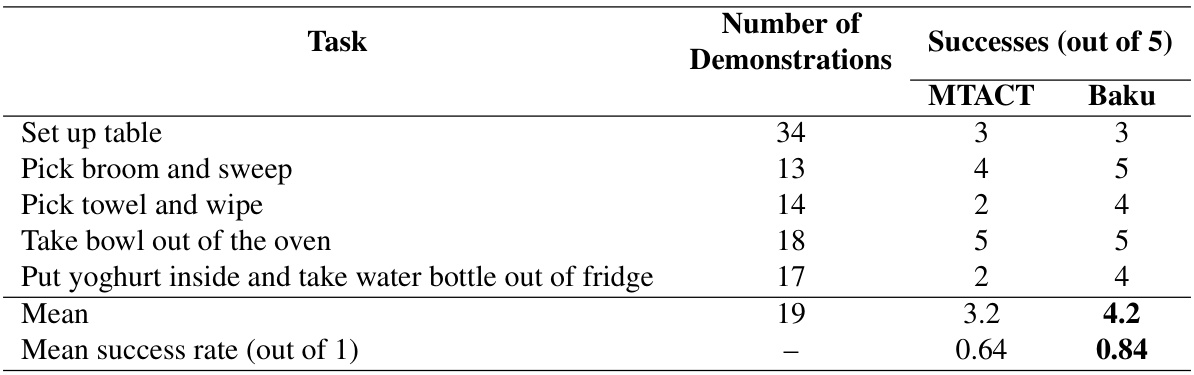

This table presents the results of a data efficiency analysis performed on the LIBERO-90 benchmark. It shows the success rate (average performance) of three different multi-task learning algorithms (RT-1, MT-ACT, and BAKU) across varying numbers of demonstrations (5, 10, 25, and 50). The table demonstrates how the performance of each algorithm changes as the amount of training data increases. It’s a key finding illustrating the improved data efficiency of the BAKU algorithm.

This table presents the performance comparison of BAKU against two state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods, RT-1 and MT-ACT. The performance is evaluated on three simulated benchmark datasets (LIBERO-90, Meta-World, and DeepMind Control) and a real-world robot manipulation task using the xArm robot. The results demonstrate that BAKU significantly outperforms the baselines on all datasets, showcasing its effectiveness in multi-task learning scenarios.

This table presents the performance comparison of BAKU using five different action heads on two benchmark datasets: LIBERO-90 and Meta-World. The results are averaged over three separate training runs (seeds) to assess the robustness of performance. Each action head represents a different approach to generating actions in the model (MLP, GMM, BeT, VQ-BeT, Diffusion). The table shows the mean success rate and standard deviation for each action head on each dataset.

This table presents an ablation study on the BAKU model architecture, evaluating the impact of different design choices on multi-task performance across three benchmarks: LIBERO-90, Meta-World, and DeepMind Control. Specifically, it compares the performance when using a common visual encoder versus separate encoders for different views, and when using separate versus concatenated observation trunk inputs. The results highlight the impact of these architectural choices on the model’s ability to effectively learn and generalize across multiple tasks.

Full paper#