↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Machine learning algorithms often struggle to effectively capture complex, non-Gaussian relationships in high-dimensional data, which are often crucial for accurate classification. Higher-order cumulants (HOCs) offer a way to quantify these relationships, but learning from them efficiently has been a challenge. Existing methods, like random features, fall short in this regime, motivating the need for more efficient algorithms.

This paper investigates the efficiency of neural networks in extracting information from HOCs. Using the spiked cumulant model, it analyzes the statistical and computational limitations of recovering a privileged direction (the “spike”) from HOCs. It introduces a theoretical analysis based on the low-degree method, showing that neural networks achieve statistical distinguishability with linear sample complexity, while polynomial-time algorithms require quadratic complexity. Numerical experiments confirm that neural networks efficiently learn from HOCs, outperforming random features significantly. The results highlight the superior learning capabilities of neural networks over simpler methods when dealing with higher-order statistical patterns.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and related fields because it addresses the critical issue of efficiently learning from higher-order correlations in high-dimensional data. The findings challenge existing assumptions about the capabilities of neural networks and kernel methods, offering valuable insights for algorithm design and model selection. This research opens new avenues for theoretical analysis of higher-order correlation learning and has practical implications for improving the efficiency and performance of machine learning algorithms.

Visual Insights#

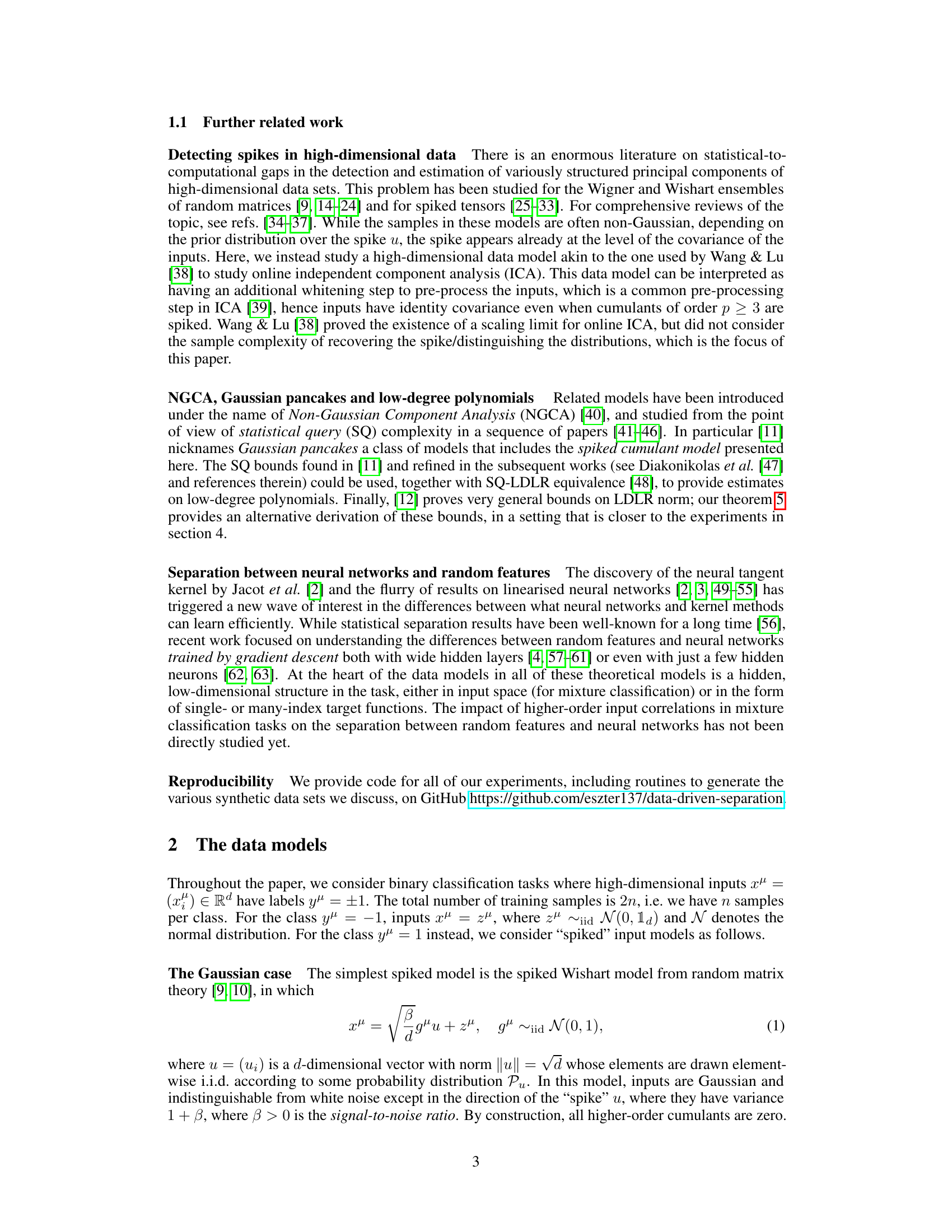

This figure shows the success rate of an exhaustive search algorithm for finding a spike in a high-dimensional space, as a function of the number of samples used. The algorithm searches through all possible spike directions in a d-dimensional hypercube. The x-axis represents the exponent θ, such that the number of samples n scales with the dimension d as n = dθ. The success rate increases sharply around θ = 1, indicating a phase transition in the distinguishability of the spiked cumulant model from the isotropic Gaussian model. This corroborates the theoretical findings presented in Theorem 2.

In-depth insights#

HOCs & Neural Nets#

The interplay between higher-order cumulants (HOCs) and neural networks is a rich area of research. HOCs capture non-Gaussian dependencies in data, which are often crucial for complex pattern recognition tasks but frequently ignored by traditional methods focusing solely on lower-order statistics. Neural networks, particularly deep learning models, excel at discovering complex patterns, demonstrating an implicit capacity to learn from HOCs. However, the exact mechanisms by which neural nets leverage HOC information remain unclear. Understanding this interaction is key to explaining the success of deep learning and improving model design. Research in this area explores the computational efficiency of extracting HOC features and the relative performance of neural networks versus alternative approaches. This includes investigating the sample complexity of learning from HOCs and comparing neural networks to simpler methods, like random features, to identify where the true strengths of neural networks lie. A key challenge in this field is establishing theoretical guarantees that explain the observed effectiveness, especially given the potential for a wide statistical-to-computational gap. Future work will need to focus on rigorous theoretical analysis and empirical validation to fully unravel the intricate relationship between HOCs and the powerful capabilities of neural networks.

Statistical Limits#

The concept of “Statistical Limits” in a research paper likely delves into the fundamental boundaries of what can be reliably inferred from data. It explores the minimum amount of data required to distinguish between competing hypotheses or models with a specified level of certainty. This often involves exploring the trade-off between the statistical power of a test (ability to detect true effects) and the probability of false positives/negatives. Key considerations might include the dimensionality of the data (high-dimensional data poses challenges), the noise level, and the inherent complexity of the underlying patterns. The analysis may involve mathematical proofs related to likelihood ratios, sample complexity, or hypothesis testing, potentially revealing phase transitions where the required sample size suddenly increases dramatically. Crucially, understanding these statistical limits helps researchers to set realistic expectations and avoid overinterpreting results obtained from limited datasets. Ultimately, a strong focus on statistical limits is a hallmark of rigorous and reliable research.

Computational Gaps#

The concept of “Computational Gaps” in the context of machine learning, particularly concerning higher-order correlations, highlights a crucial dichotomy. Statistical analyses might reveal that a certain amount of data is sufficient to distinguish between two distributions. However, the computational complexity of achieving this distinction using known algorithms can be far greater. This discrepancy stems from the inherent challenges in efficiently processing high-dimensional data and extracting information from complex statistical relationships like higher-order cumulants. The paper likely explores this gap by comparing the sample complexity required by different algorithms, potentially showing that neural networks are significantly more efficient in this regime than simpler methods. This finding would underscore the advantage of neural networks’ adaptive nature in uncovering complex data patterns that are computationally intractable for traditional approaches. The existence of such a gap emphasizes that simply having enough data isn’t enough; computationally efficient algorithms are equally crucial for practical machine learning applications. This necessitates further investigation into algorithmic innovations that can bridge this gap and unlock the full potential of complex data analysis.

Neural Network Efficiency#

The efficiency of neural networks is a multifaceted topic. Computational cost is a major concern, particularly with large models and datasets. The paper investigates the sample complexity of neural networks, revealing that higher-order cumulants significantly influence the amount of data required for effective learning. While neural networks demonstrate superior efficiency in extracting information from these cumulants compared to simpler methods like random features, their sample complexity remains quadratic. This quadratic scaling highlights a potential computational bottleneck, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional data. The study also underscores the critical role of architectural choices and algorithmic innovations in improving neural network efficiency, with further research needed to fully understand how to mitigate the computational challenges presented by high-order correlations.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on efficiently learning higher-order correlations could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to encompass more complex null hypotheses beyond isotropic Gaussian distributions is crucial for broader applicability. This would involve developing new tools to handle more realistic data scenarios. Another important area is investigating the dynamics of neural networks on spiked cumulant models or non-linear Gaussian processes to better understand how these networks extract information from higher-order cumulants of real-world datasets. A systematic exploration of the impact of different non-Gaussian latent distributions on the statistical-computational gap is needed to refine the understanding of the learning process. Finally, developing efficient algorithms beyond neural networks capable of leveraging higher-order correlations to improve the sample complexity could revolutionize learning in high-dimensional settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

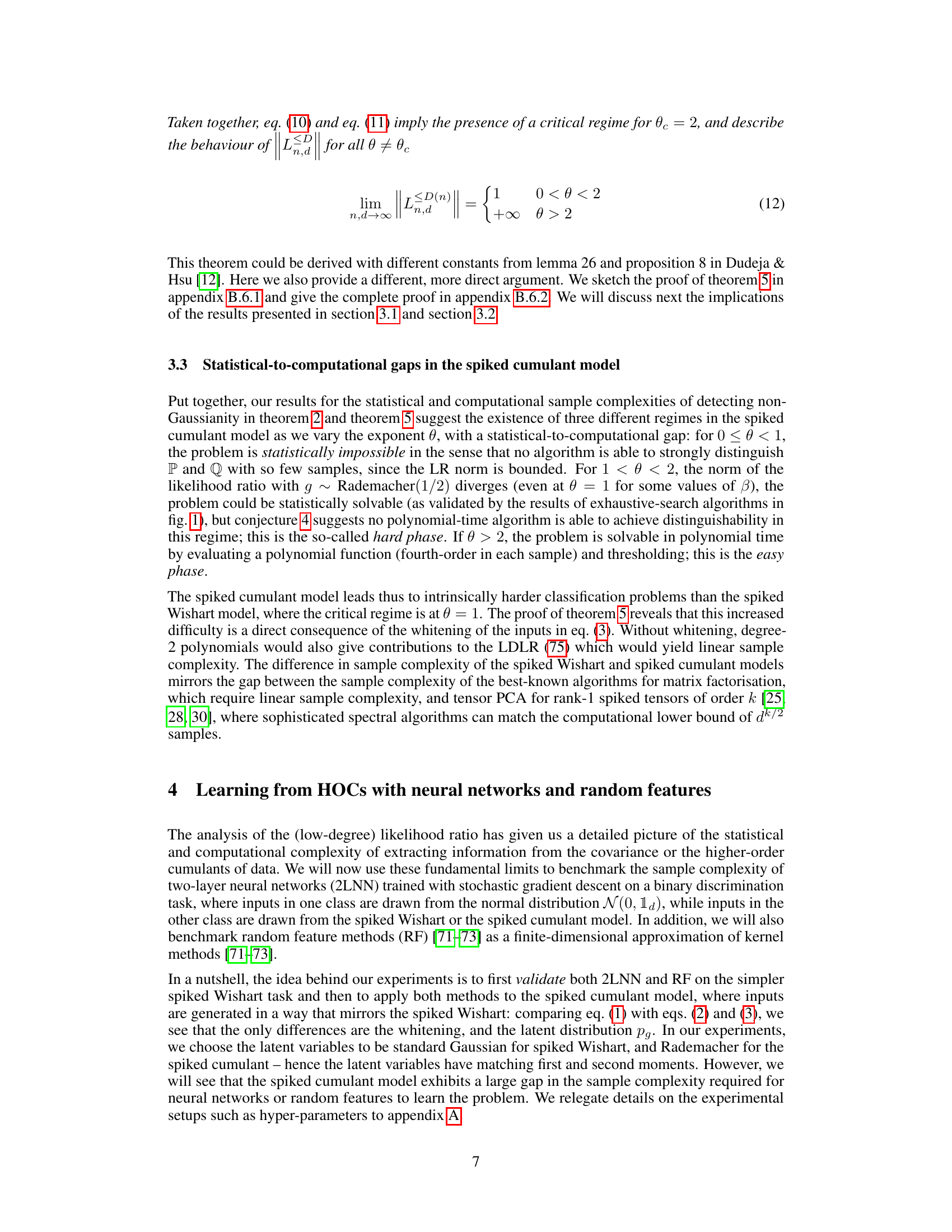

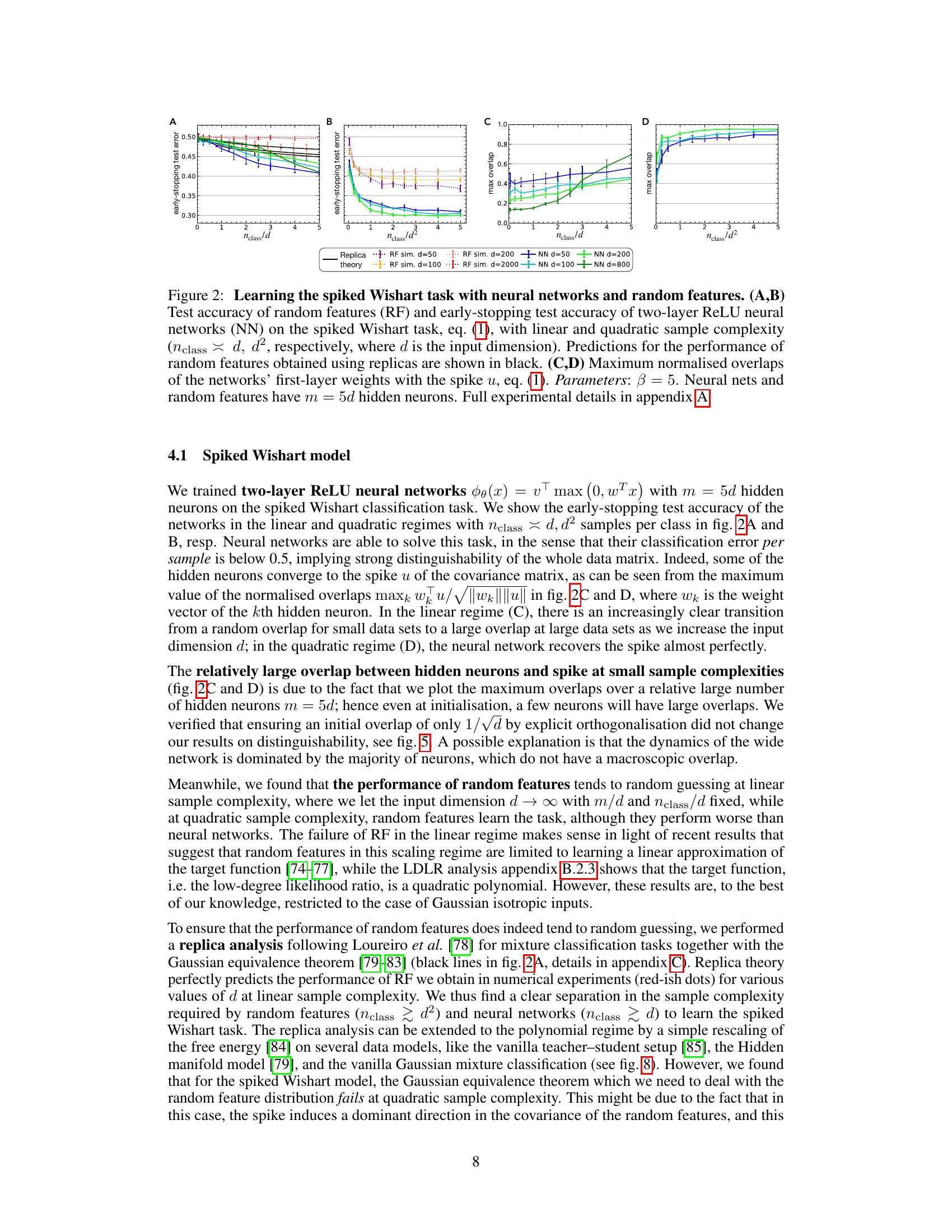

This figure shows the results of experiments on the spiked Wishart model, comparing the performance of neural networks and random features in both linear and quadratic sample complexity regimes. Panels (A) and (B) display the test accuracy, showing neural networks successfully learn the task in both regimes while random features only succeed in the quadratic regime. Panels (C) and (D) illustrate the overlap between the first-layer weights of the neural network and the spike, demonstrating efficient feature extraction by the neural network.

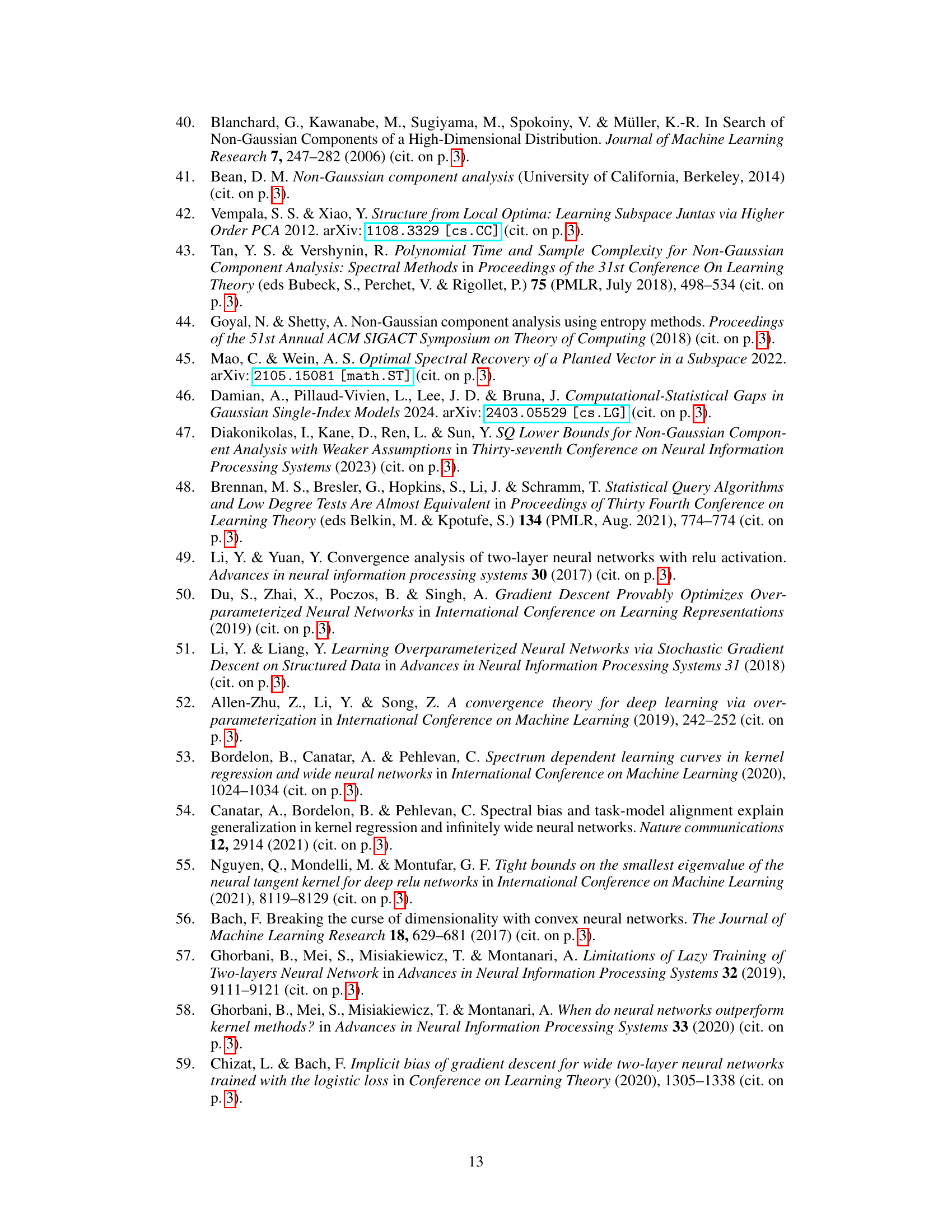

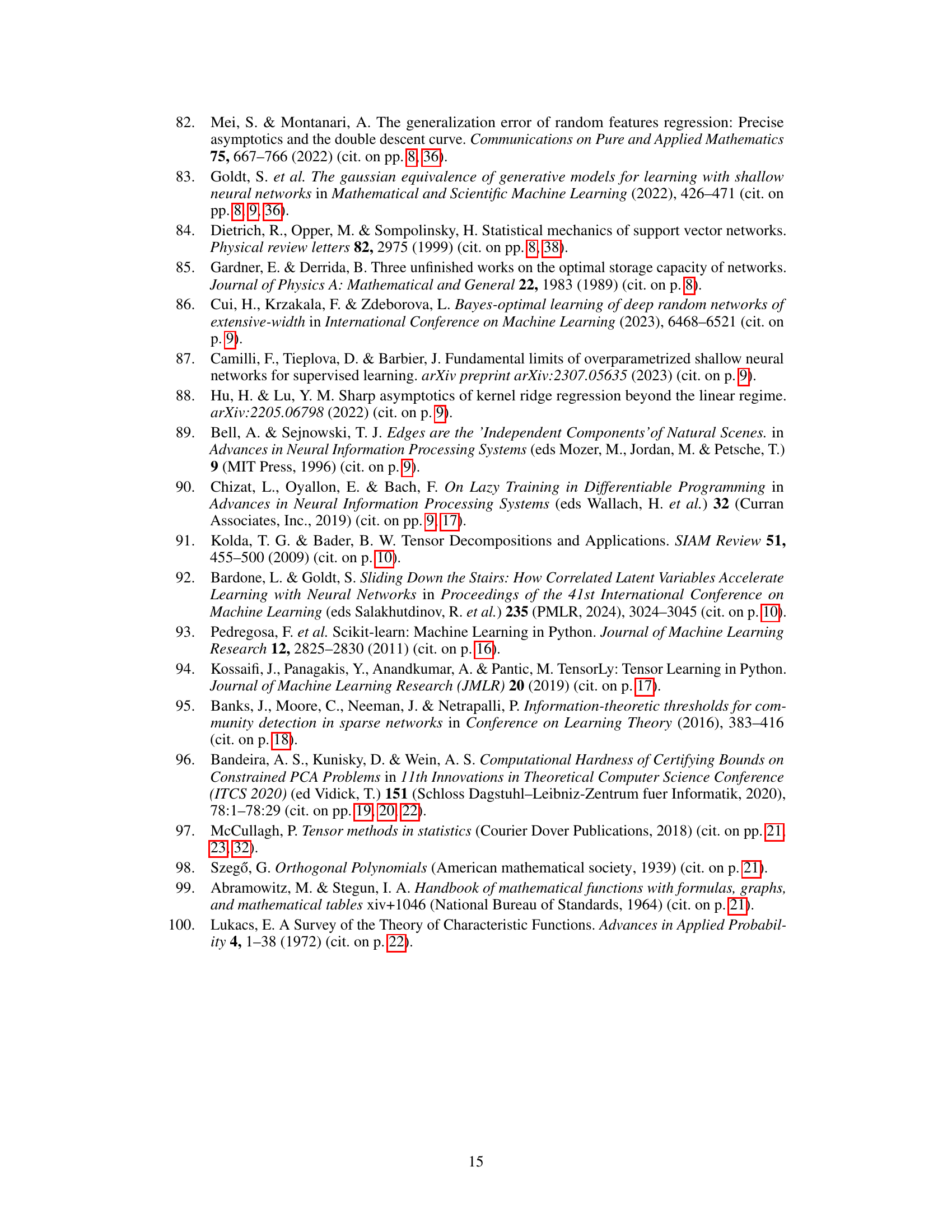

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of neural networks and random features on a spiked cumulant task. Panels A and B show the test accuracy of both methods at linear and quadratic sample complexities (nclass/d and nclass/d^2, respectively), demonstrating the quadratic sample complexity required for random features to succeed. Panels C and D depict the maximum normalized overlaps between the networks’ first-layer weights and the spike for linear and quadratic sample complexities, further illustrating the efficiency of neural networks in this scenario.

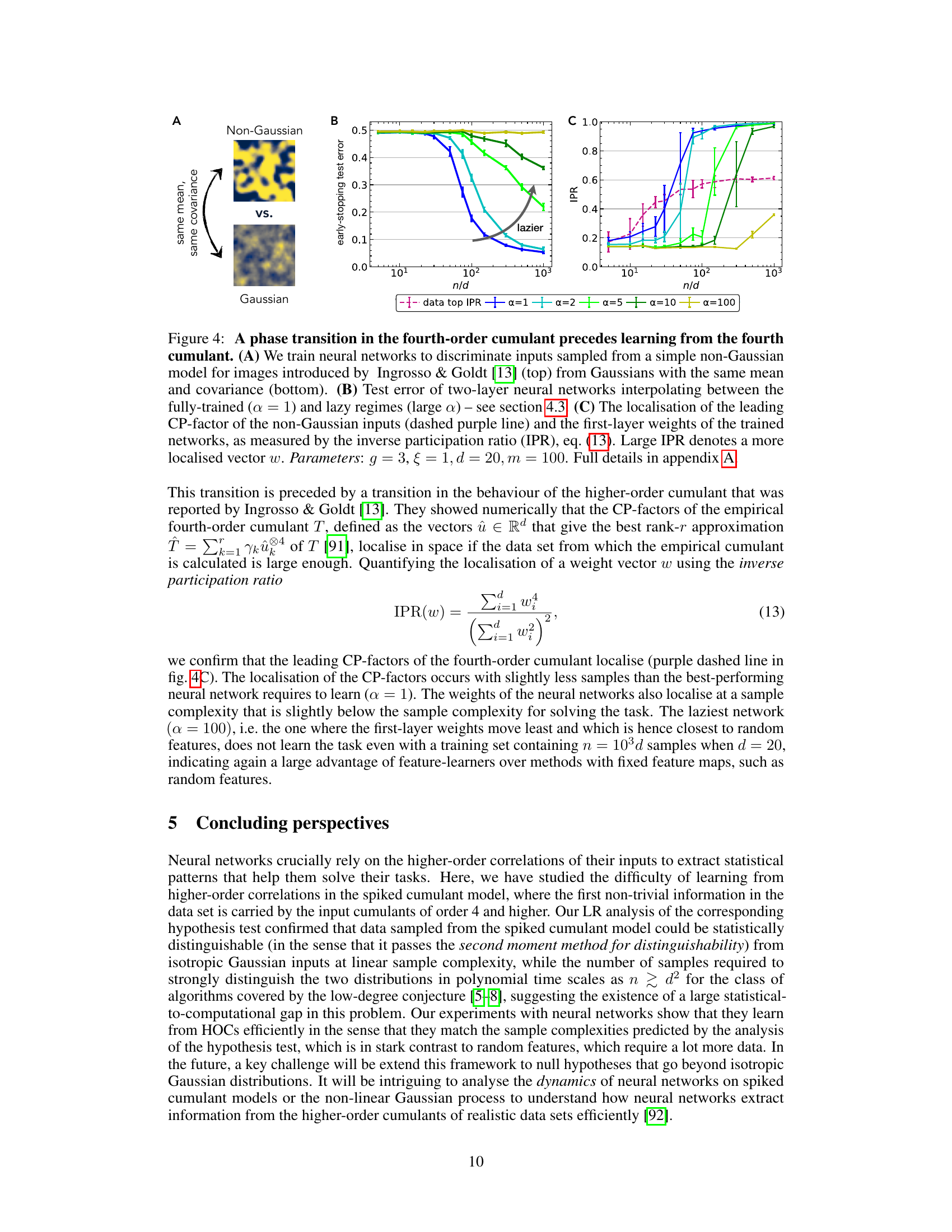

This figure shows a phase transition in the fourth-order cumulant that precedes learning from the fourth cumulant in a simple image model. Panel A displays the two classes of images used in the binary classification task: a non-Gaussian image model and a Gaussian image with the same mean and covariance. Panel B shows the test error of two-layer neural networks as a function of the number of training samples (n/d), where the networks interpolate between the ‘fully-trained’ (α = 1) and ’lazy’ regimes (large α). The inverse participation ratio (IPR) in Panel C measures the localization of the leading CP-factor of the non-Gaussian inputs and the first-layer weights of trained networks. High IPR values indicate more localized vectors. The results suggest that a phase transition in the fourth-order cumulant occurs before the networks learn the task efficiently.

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of neural networks and random features on a spiked Wishart classification task. Panels A and B show the test accuracy of random features (RF) and neural networks (NN) respectively, under both linear and quadratic sample complexity scaling. The black lines in A and B represent theoretical predictions from replica analysis. Panels C and D display the overlap between the networks’ first-layer weights and the spike vector, again for linear and quadratic sample complexities. The results demonstrate that neural networks efficiently learn the task in both regimes while random features struggle in the linear regime, achieving near-chance performance.

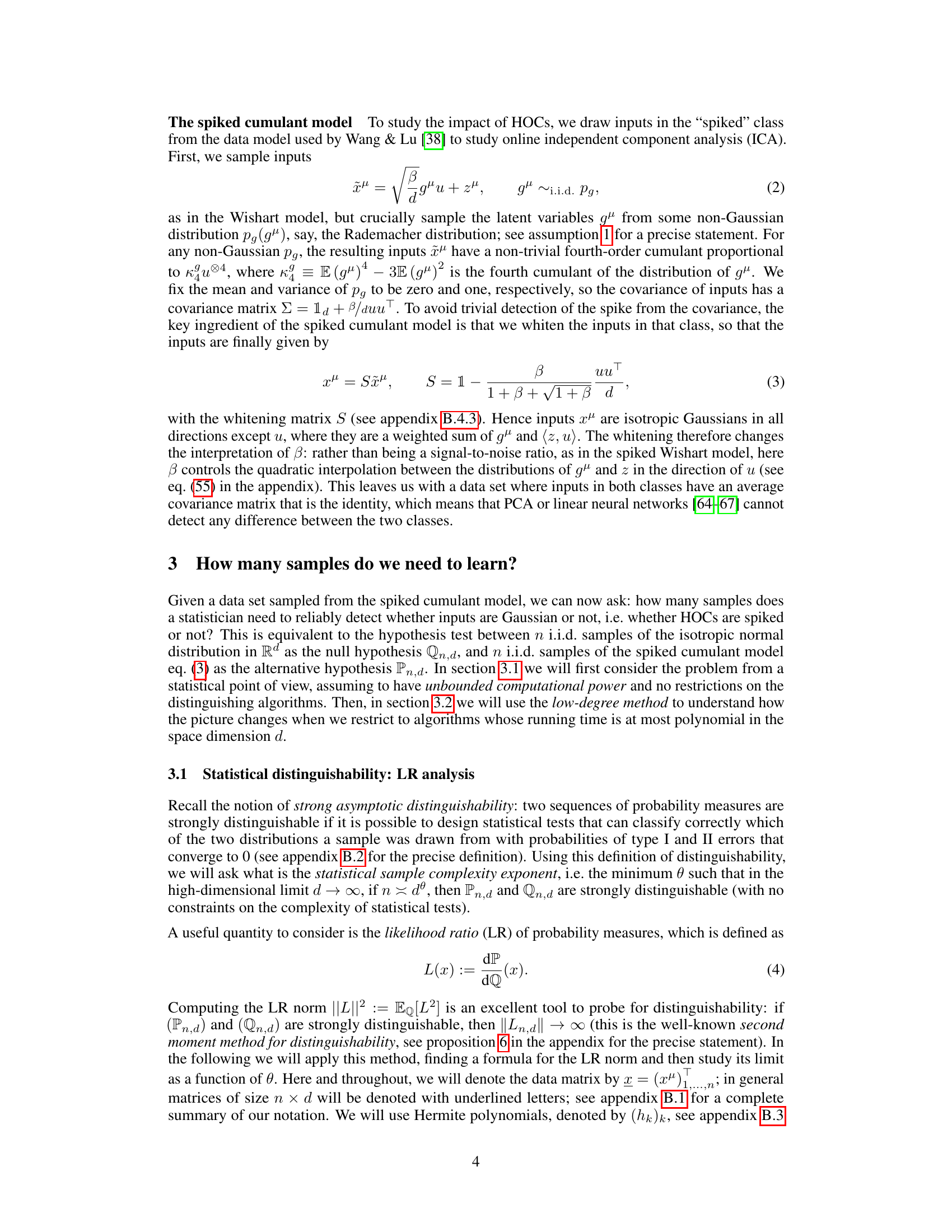

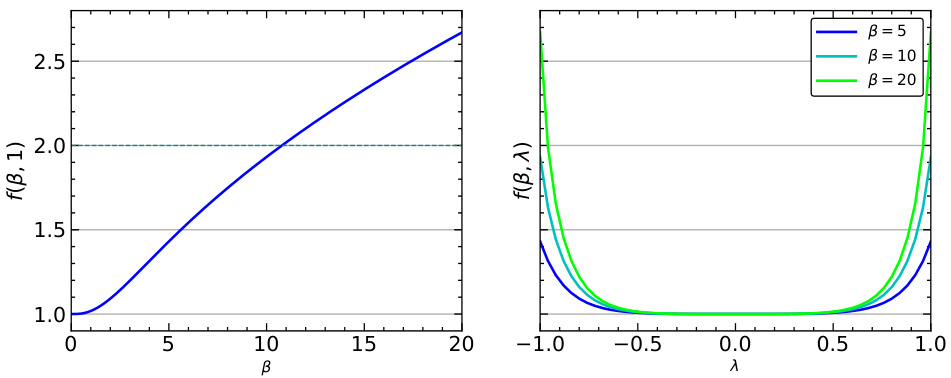

The figure shows the graphs of function f(β,λ) for different values of β, where λ is the overlap between two independent replicas of spike u and v and g is drawn from the Rademacher distribution. This function is important in calculating the likelihood ratio norm for the spiked cumulant model.

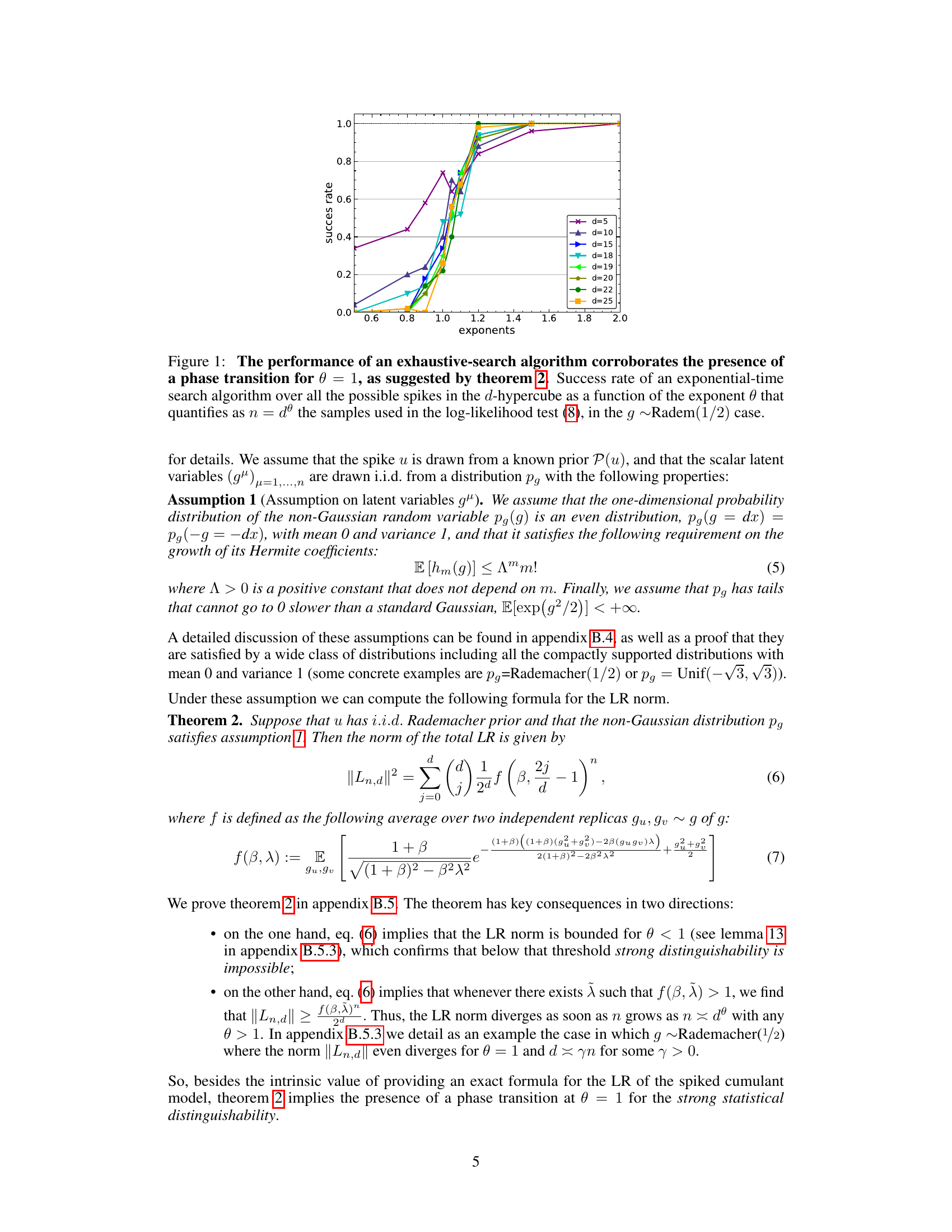

This figure shows the behavior of the likelihood ratio (LR) norm and its lower bound for different values of β (signal-to-noise ratio) and θ (sample complexity exponent). The left panel shows that the LR norm remains bounded for β < βγ ≈ 10.7, while it diverges for β > βγ. The right panel shows that the lower bound on the LR norm given by equation (73) in the paper diverges for θ > 2, indicating that the sample complexity for distinguishing the two models (spiked cumulant and isotropic Gaussian) is at least quadratic in d for polynomial-time algorithms. This corroborates the theoretical findings of the paper concerning the statistical and computational trade-offs in learning from higher-order correlations.

This figure compares the generalization error of random features for three different synthetic data models: Hidden Manifold model, teacher-student setup, and Gaussian mixture model. It shows how the generalization error changes as the number of samples scales linearly and quadratically with the input dimension. The results from numerical simulations are plotted against the theoretical predictions obtained from replica theory, illustrating the linear and quadratic regimes of sample complexity for these models.

Full paper#