TL;DR#

Resource allocation in public health struggles with adapting to evolving priorities and limited resources. Restless Multi-Armed Bandits (RMABs) optimize resource allocation but lack flexibility to adapt to changing policies. Large Language Models (LLMs) excel in automated planning.

This paper introduces a Decision-Language Model (DLM) that uses LLMs to dynamically adapt RMAB policies. The DLM interprets human-language policy commands, generates reward functions for an RMAB environment, and iteratively refines these functions based on simulated RMAB outcomes. Evaluated in a maternal healthcare setting, DLM dynamically shapes policy outcomes, demonstrating the potential for human-AI collaboration in dynamic resource allocation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on resource allocation in public health and AI planning. It bridges the gap between human-centric policy preferences and automated resource allocation by using LLMs, which is highly relevant to the current trends in explainable AI and human-in-the-loop decision-making. The methodology presented offers a novel approach to dynamic policy adjustments and creates new avenues for exploring the intersection of LLMs and RMABs in various domains.

Visual Insights#

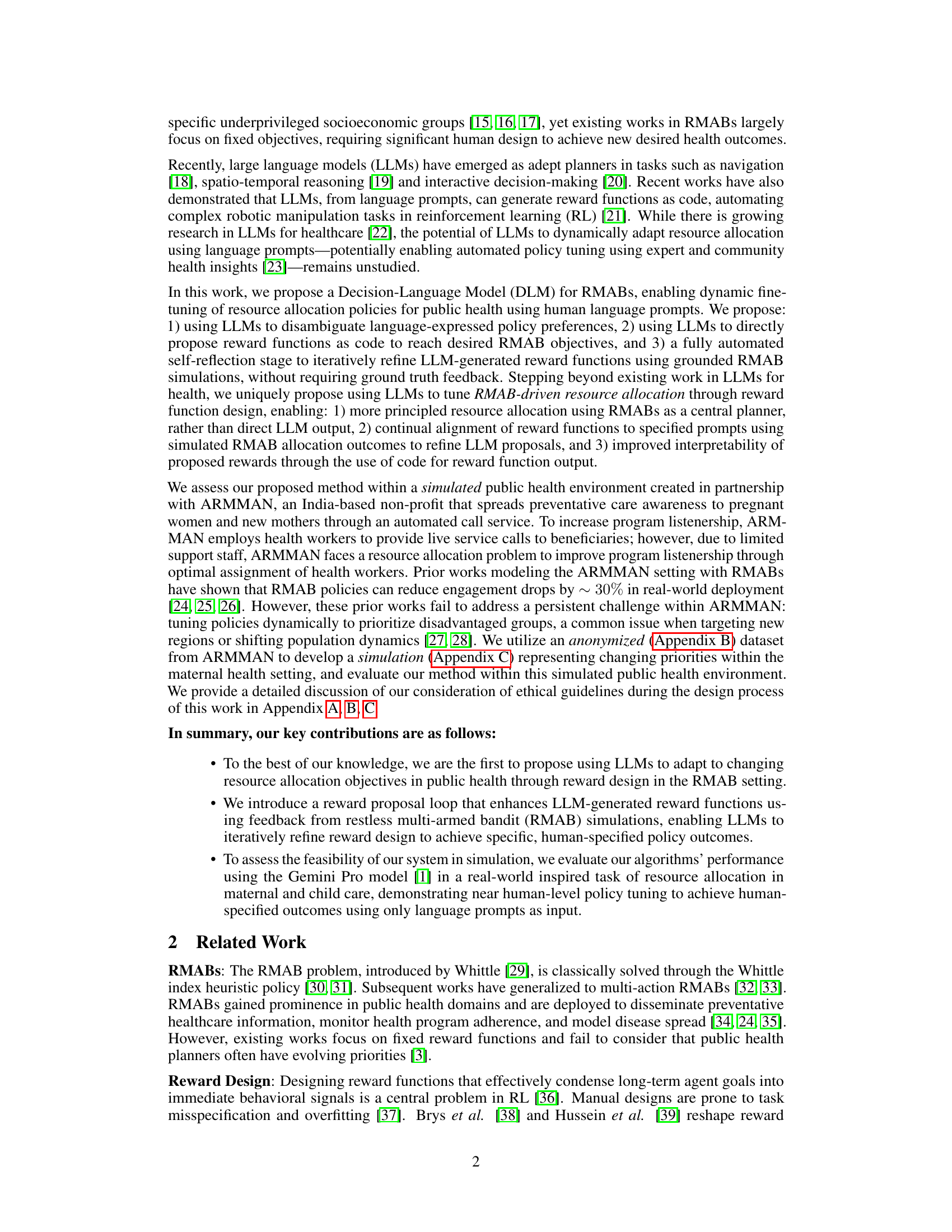

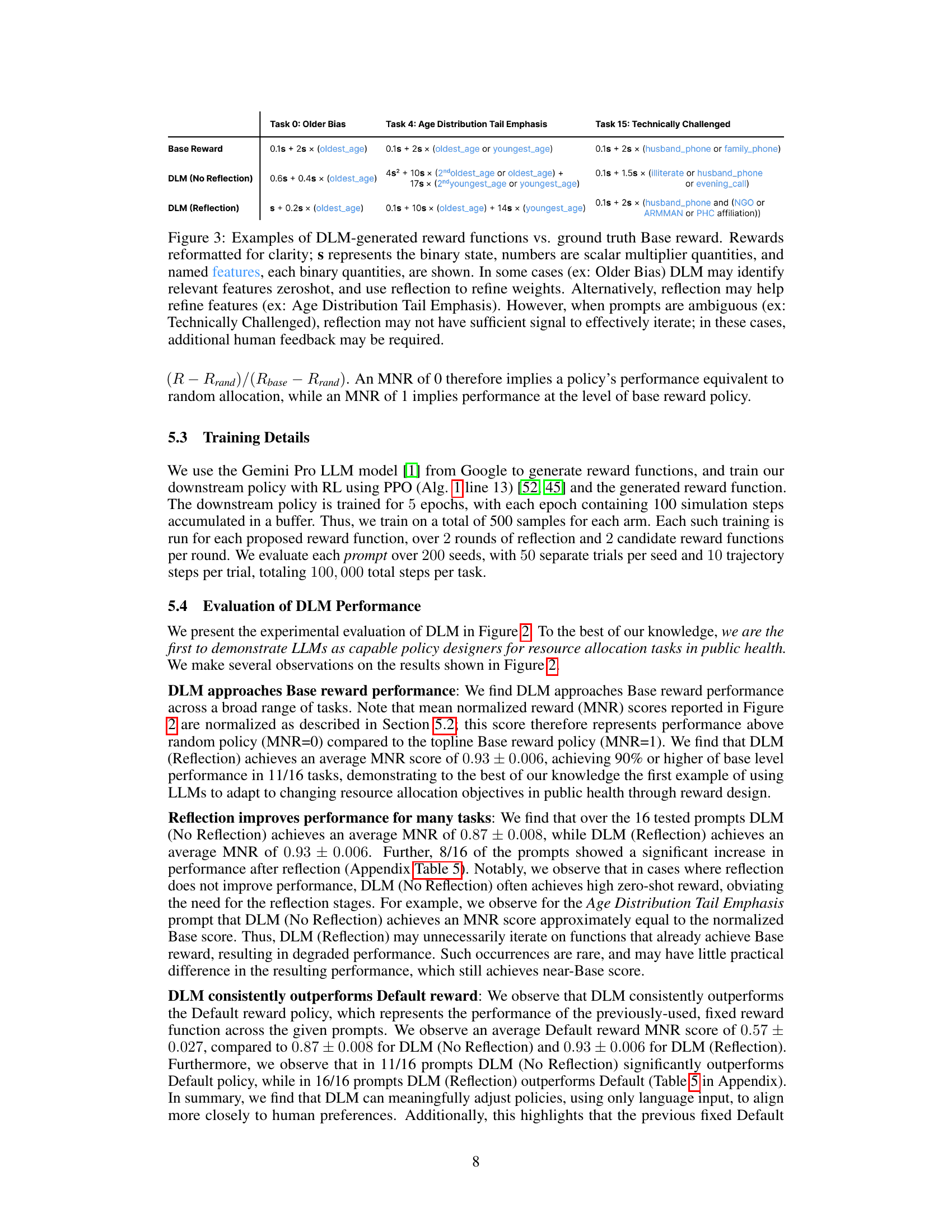

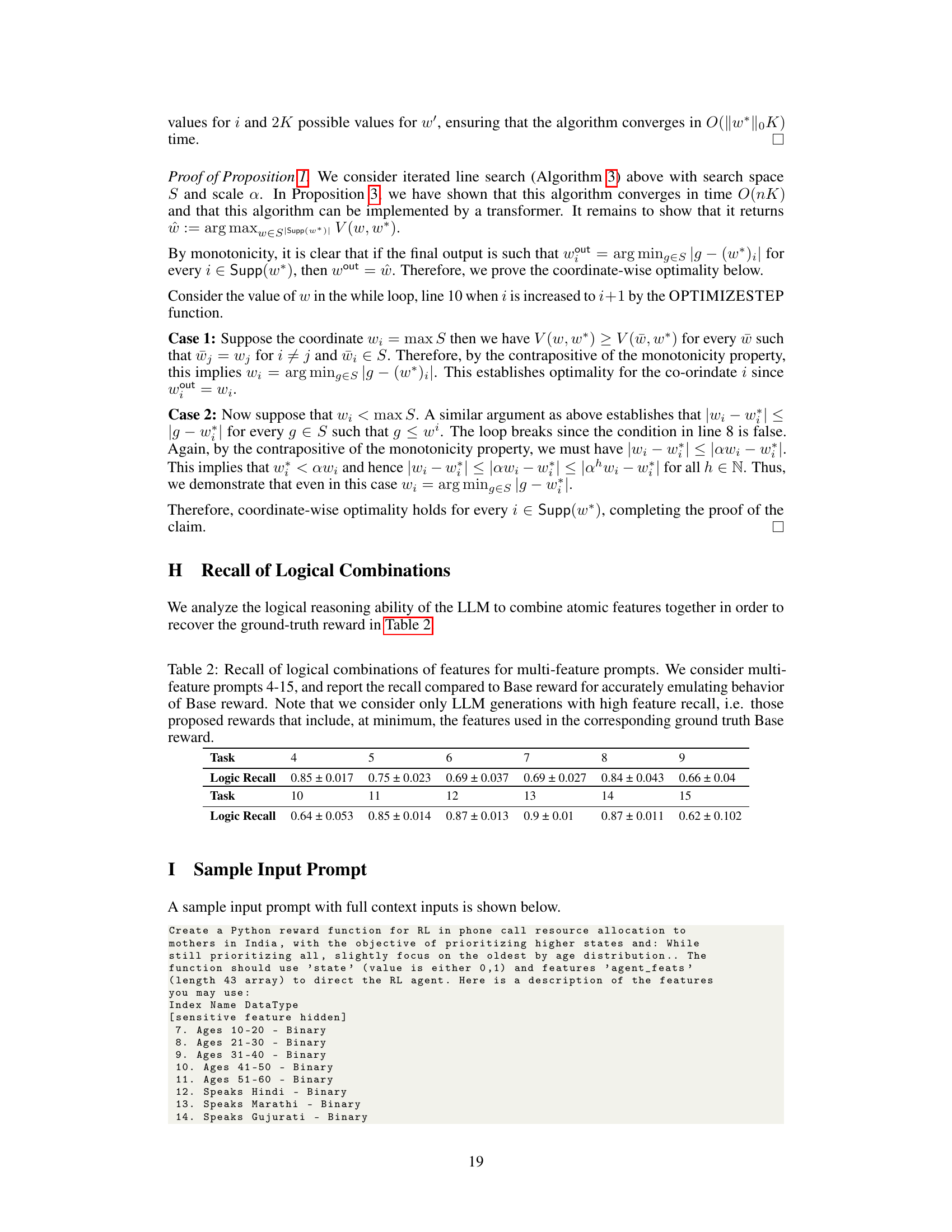

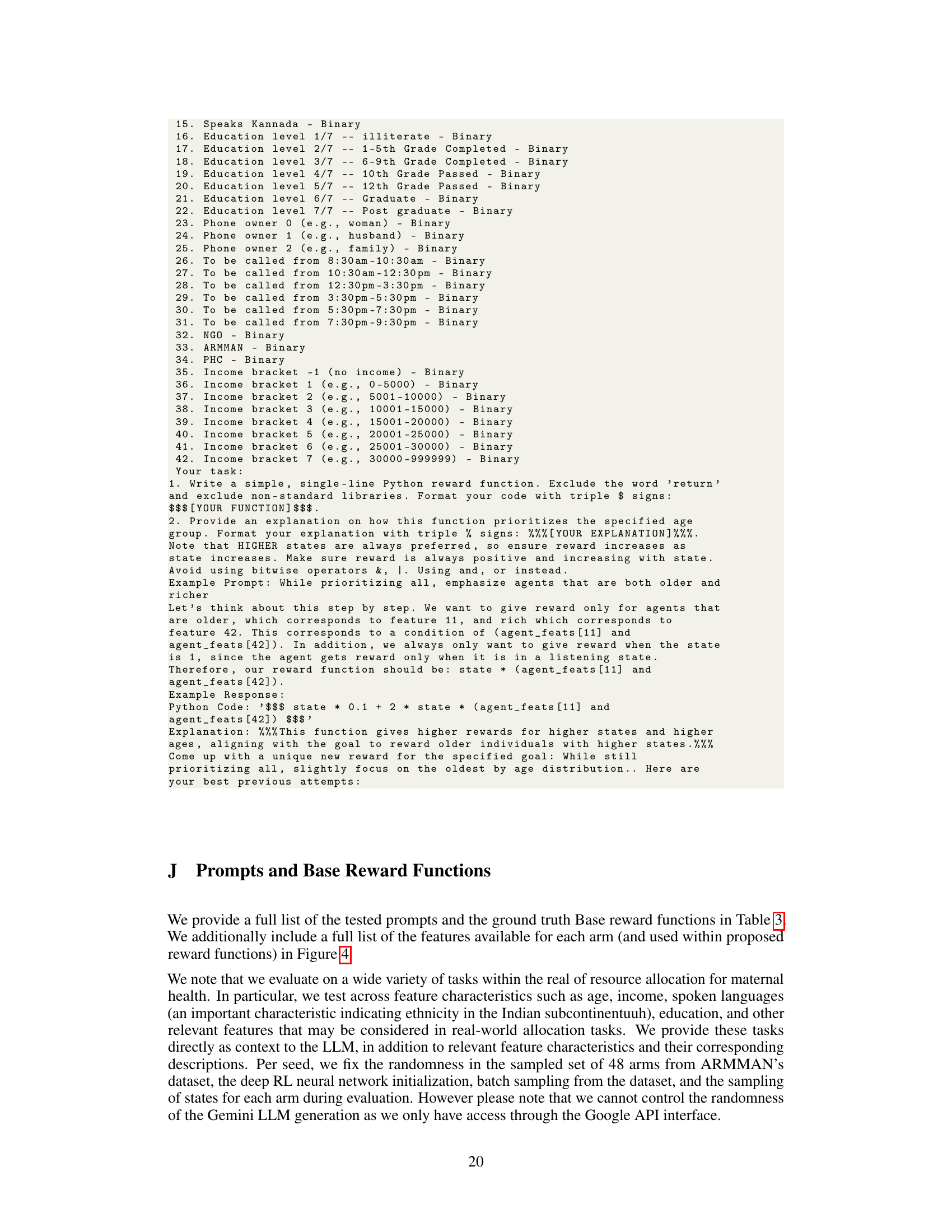

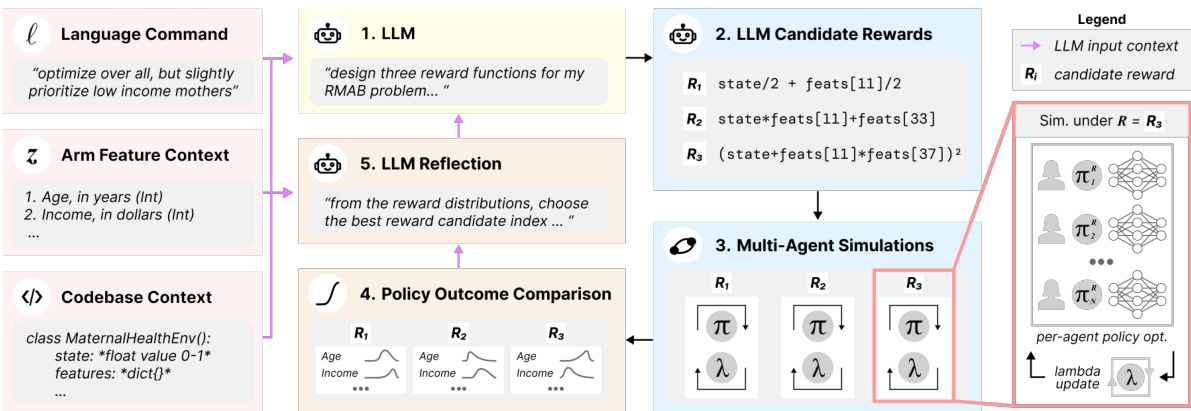

🔼 This figure illustrates the Decision-Language Model (DLM) process. It starts with a human-provided language command and relevant arm features. The LLM uses this information to propose candidate reward functions. These are then tested in multi-agent simulations, and the results (policy outcomes) are fed back to the LLM for reflection and refinement. The LLM selects the best candidate, and the process iterates until satisfactory policy is achieved. The feedback loop uses state-feature distributions to guide refinement instead of ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the DLM language-conditioned reward design loop. We provide three context descriptions to the LLM: a language command (full list of commands in Table 3), a list of per-arm demographic features available for proposed reward functions, and syntax cues enabling LLM reward function output directly in code. From this context, the 1) LLM then proposes 2) candidate reward functions which are used to train 3) optimal policies under proposed rewards. Trained policies are simulated to generate 4) policy outcome comparisons showing state-feature distributions over key demographic groups. Finally, we query an LLM to perform 5) self-reflection [43, 21] by choosing the best candidate reward aligning with the original language command; selected candidates are used as context to guide future reward generation.

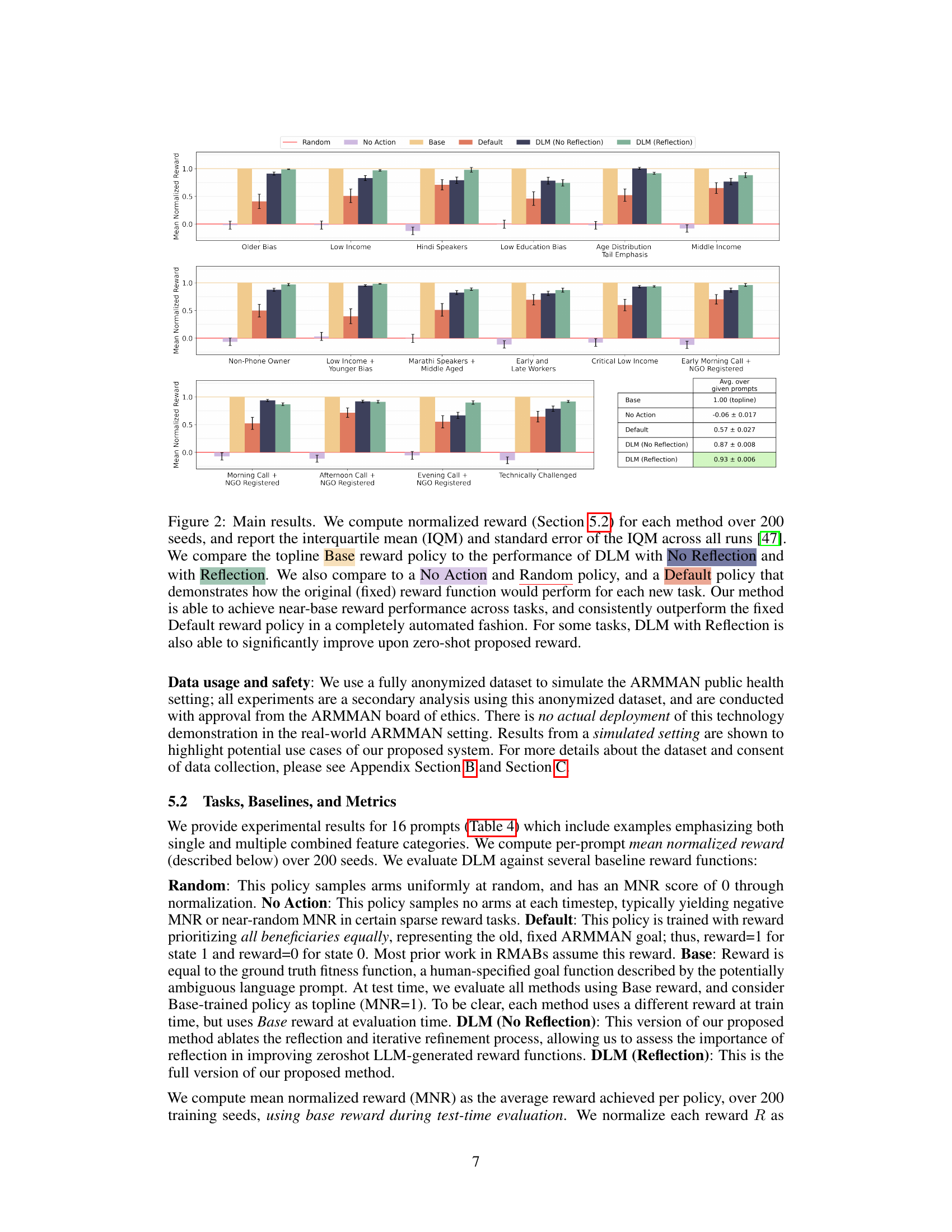

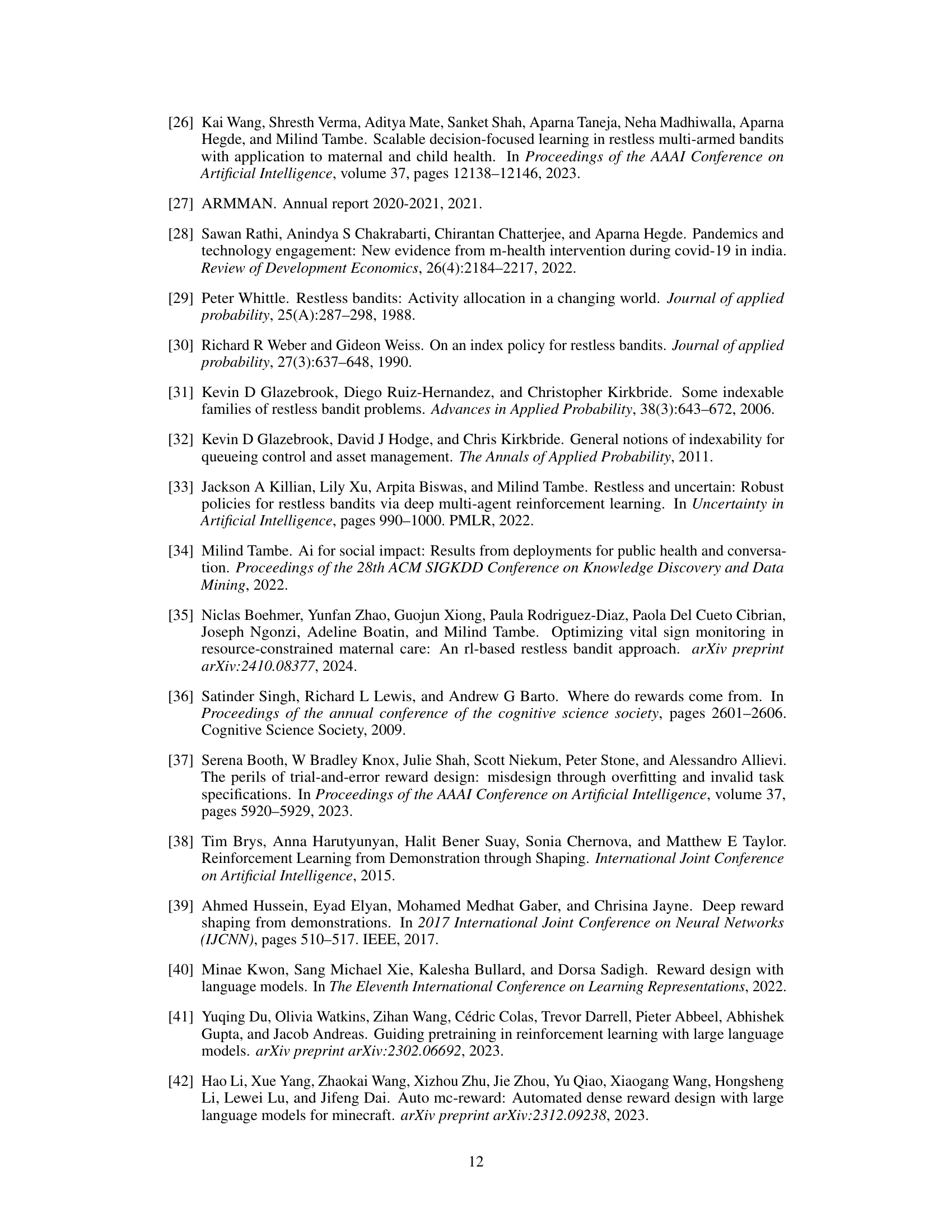

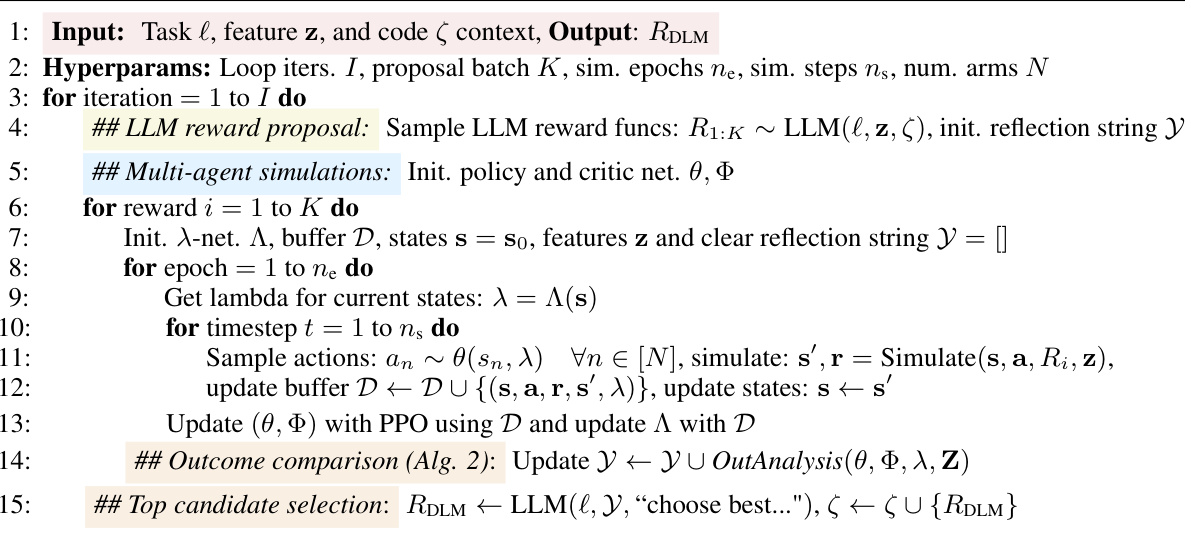

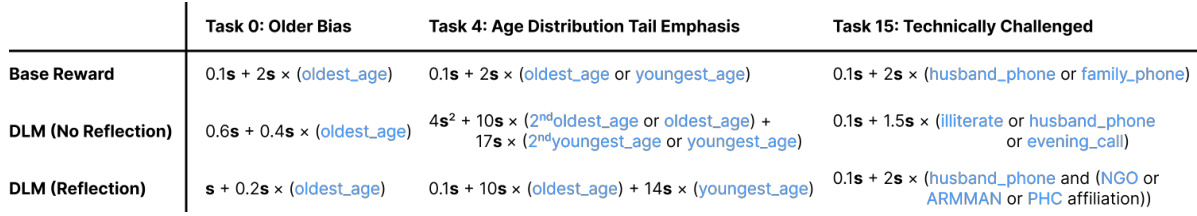

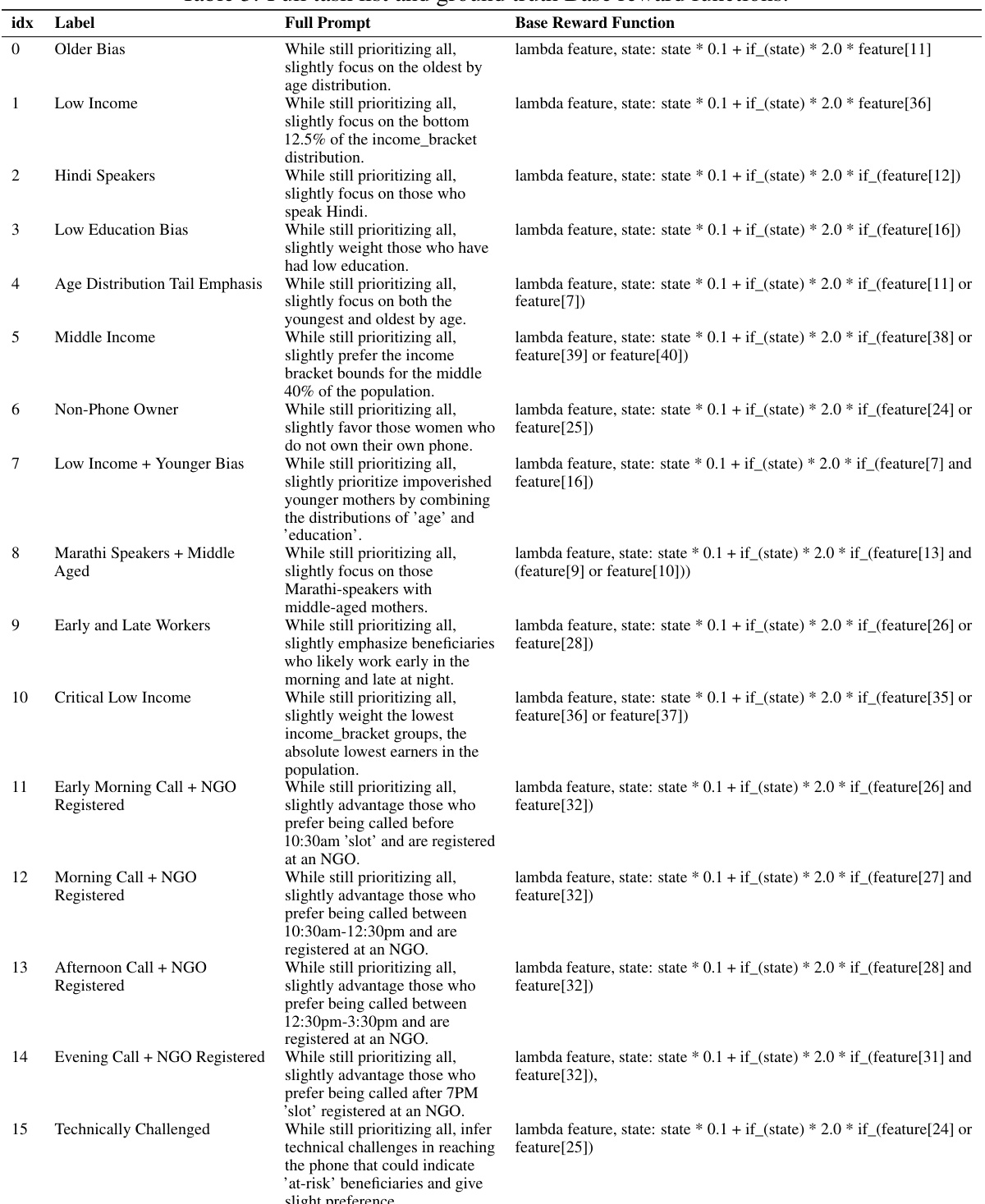

🔼 This table lists 16 different tasks (numbered 0-15) used to evaluate the proposed DLM. Each task is described by a natural language prompt specifying a desired policy outcome. The table shows the complete prompt for each task and the corresponding ground truth reward function used as a baseline for comparison in the evaluation. This baseline represents a direct implementation of the desired outcome. The reward function is a lambda function, using the current state and feature vector of each arm to generate a reward score.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

In-depth insights#

DLM for RMABs#

The proposed Decision-Language Model (DLM) for Restless Multi-Armed Bandits (RMABs) presents a novel approach to dynamically adapt RMAB policies in public health. The core innovation lies in leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) to bridge the gap between human-expressed policy preferences and the formal language of RMAB reward functions. Instead of manually designing reward functions, the DLM uses LLMs to interpret human language commands, generate code for reward functions, and iteratively refine these functions based on simulated RMAB outcomes. This approach offers significant advantages: increased flexibility in adapting to evolving policy priorities, automation of reward function design, and improved interpretability. The integration of LLMs makes the DLM particularly suitable for public health settings where expert knowledge and community input are crucial but may be difficult to translate into formal mathematical models. The system’s ability to dynamically shape policy outcomes solely through human-language prompts is a major advancement, promising more efficient and adaptable resource allocation in complex public health challenges.

LLM Reward Design#

The core idea revolves around leveraging LLMs to automate the design of reward functions for Restless Multi-Armed Bandit (RMAB) problems in public health. This is a significant departure from traditional RMAB approaches, which often involve manual and laborious design of these crucial functions. The LLM acts as an automated planner, interpreting human-provided policy goals expressed in natural language. This allows for dynamic adaptation of RMAB policies without requiring extensive code modification or deep RL expertise. The process involves an iterative refinement loop where LLM-proposed reward functions are tested in simulation, and the results are fed back to the LLM for iterative improvements. This feedback mechanism helps to align the LLM’s reward design with the intended policy goals, ultimately improving the efficiency and effectiveness of resource allocation in dynamic and complex public health scenarios. The key advantage lies in the flexibility and adaptability offered by this approach, enabling the system to respond effectively to evolving priorities and new insights without requiring significant re-engineering.

ARMMAN Simulation#

The ARMMAN simulation, a crucial component of the study, provides a realistic environment for evaluating the proposed Decision-Language Model (DLM). It leverages anonymized data from ARMMAN, an Indian non-profit focused on maternal health, to simulate the challenges of resource allocation in a real-world setting. This approach offers several advantages. Firstly, it allows the researchers to test the DLM in a high-fidelity environment, mimicking the complexities and nuances of actual resource allocation in public health. Secondly, by using real-world data, the simulation offers a greater degree of realism and generalizability than a hypothetical model. Thirdly, the simulation allows for controlled experimentation and comparison of different reward functions and DLM configurations, without the ethical concerns or practical limitations of implementing the model in a real-world setting. The use of anonymized data addresses privacy concerns, ensuring responsible use of sensitive information. However, it’s important to acknowledge that a simulation, however realistic, is still an approximation of reality. Its effectiveness depends heavily on the accuracy and representativeness of the underlying data, and the extent to which the simulated environment mirrors the actual decision-making process. The study’s findings, although promising, would ideally be complemented by real-world trials to ensure full generalizability and validate the DLM’s effectiveness in practical contexts.

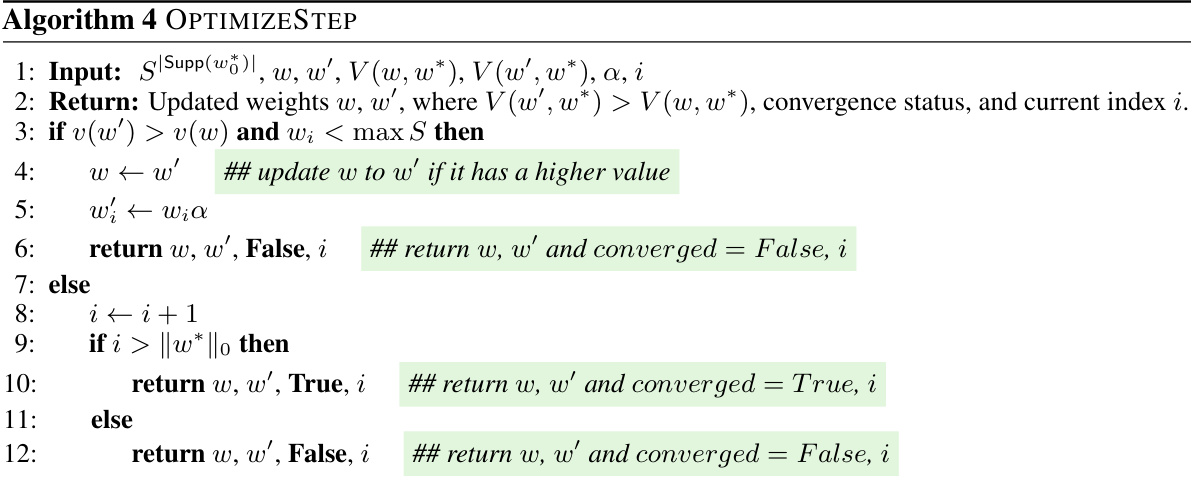

Reflection Mechanism#

A reflection mechanism in reinforcement learning allows an agent to improve its performance by analyzing past experiences and adjusting its behavior accordingly. In the context of this research paper, a novel reflection mechanism is proposed that uses a large language model (LLM) to interpret the results of simulations run with different reward functions and make informed decisions about which reward function is best. This is particularly useful when dealing with complex, real-world tasks like those in public health where providing ground truth feedback might be difficult or impossible. The LLM’s ability to process and interpret the simulation results in natural language allows for more efficient and adaptable tuning of policies in response to human-specified policy preferences. The automated iterative process enhances the DLM’s adaptability. This approach moves beyond the limitations of fixed reward functions commonly used in restless multi-armed bandit (RMAB) problems. Crucially, the method does not require ground truth feedback during the reward refinement process, instead relying on simulated outcomes. However, the efficacy of this reflection mechanism is dependent on the quality of the LLM and the ability of the simulated environment to adequately capture the complexities of the real-world task. This is also a key area of future work.

Ethical Considerations#

Ethical considerations in AI, especially within the public health sector, are paramount. This research, while conducted entirely in simulation using anonymized data, highlights the need for responsible AI development and deployment. The authors correctly acknowledge the potential for algorithmic bias to disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, emphasizing the importance of participatory design and fairness. The emphasis on transparency through clearly described methods and simulations, coupled with the collaboration with ARMMAN (an ethical partner), shows a commitment to responsible innovation. However, future work should explicitly address data bias mitigation techniques and include mechanisms for human oversight and intervention. The limitations of a purely simulated environment and the potential for misinterpretations of ambiguous user prompts must be carefully considered for future real-world applications. Ensuring that AI systems are aligned with community needs and values, and that they do not perpetuate existing inequalities, must be a central focus of continued research and development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

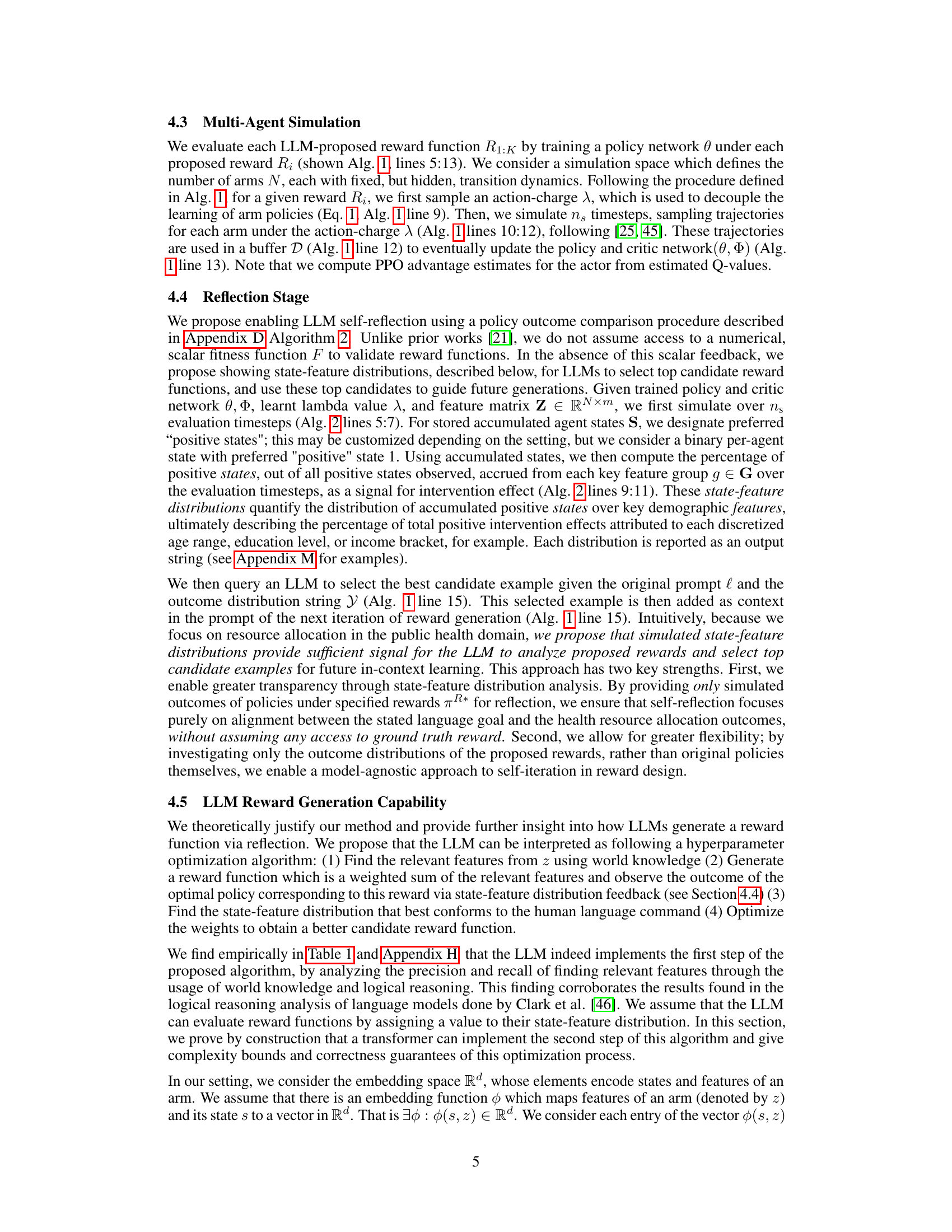

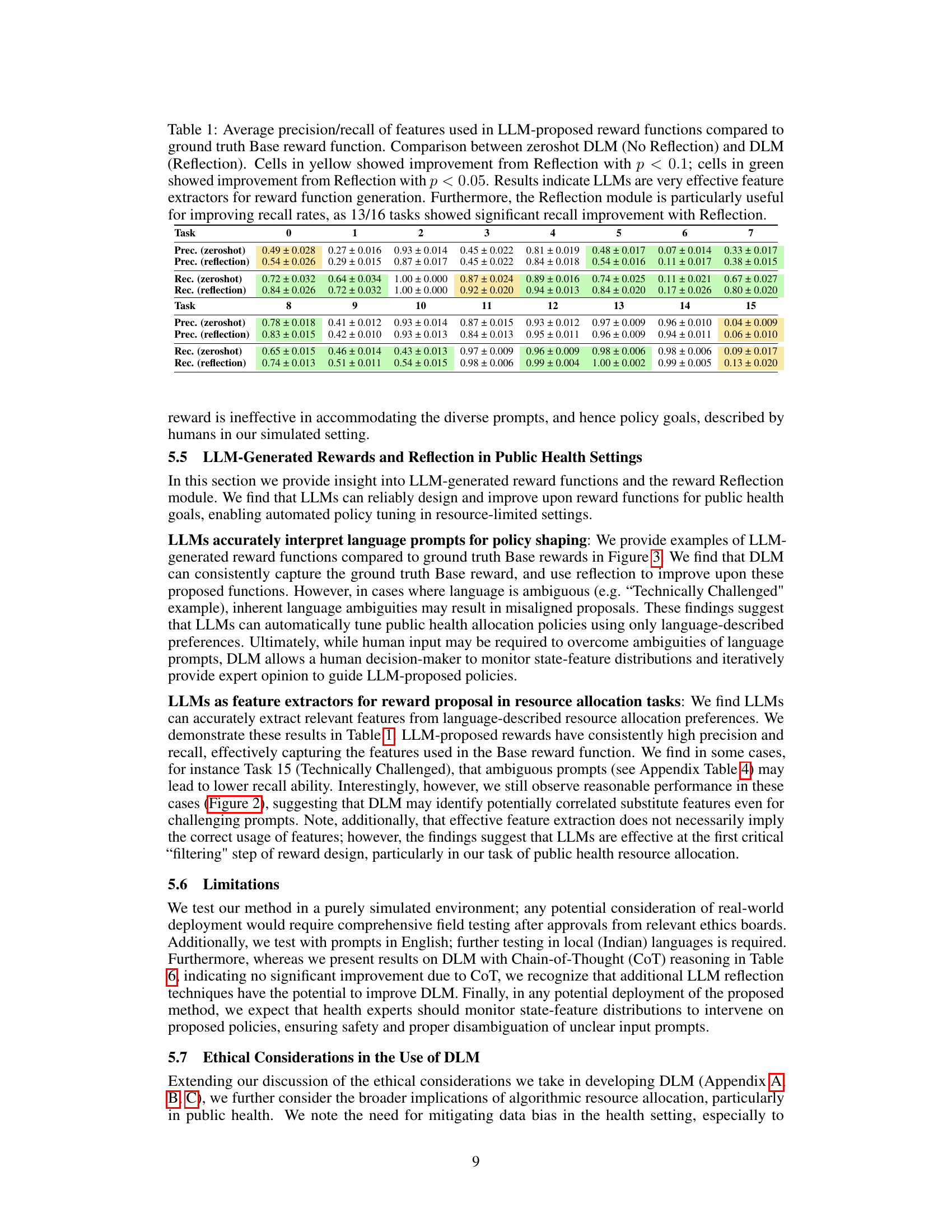

🔼 This figure shows the main results of the paper, comparing the performance of different methods for reward generation in a restless multi-armed bandit setting. The methods compared are: Random, No Action, Base, Default, DLM (No Reflection), and DLM (Reflection). The y-axis represents the mean normalized reward, and the x-axis represents different tasks. The figure demonstrates that DLM (Reflection), which uses the proposed method of iterative refinement based on feedback from simulations, achieves near-optimal performance across most tasks and significantly outperforms the fixed default reward policy.

read the caption

Figure 2: Main results. We compute normalized reward (Section 5.2) for each method over 200 seeds, and report the interquartile mean (IQM) and standard error of the IQM across all runs [47]. We compare the topline Base reward policy to the performance of DLM with No Reflection and with Reflection. We also compare to a No Action and Random policy, and a Default policy that demonstrates how the original (fixed) reward function would perform for each new task. Our method is able to achieve near-base reward performance across tasks, and consistently outperform the fixed Default reward policy in a completely automated fashion. For some tasks, DLM with Reflection is also able to significantly improve upon zero-shot proposed reward.

🔼 This figure illustrates the iterative process of the Decision-Language Model (DLM) for designing reward functions in a restless multi-armed bandit (RMAB) setting. The DLM uses an LLM to interpret human-language commands, propose reward functions as code, and refine these functions based on feedback from RMAB simulations. The process involves three main stages: 1. LLM Reward Generation: The LLM receives a language command, arm features, and code syntax as input, and then generates candidate reward functions. 2. Multi-Agent Simulation: The proposed reward functions are evaluated using multi-agent simulations to generate policy outcomes. 3. LLM Reflection: The LLM evaluates the policy outcomes, selects the best candidate reward function, and then uses this selection as context for future reward function generation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the DLM language-conditioned reward design loop. We provide three context descriptions to the LLM: a language command (full list of commands in Table 3), a list of per-arm demographic features available for proposed reward functions, and syntax cues enabling LLM reward function output directly in code. From this context, the 1) LLM then proposes 2) candidate reward functions which are used to train 3) optimal policies under proposed rewards. Trained policies are simulated to generate 4) policy outcome comparisons showing state-feature distributions over key demographic groups. Finally, we query an LLM to perform 5) self-reflection [43, 21] by choosing the best candidate reward aligning with the original language command; selected candidates are used as context to guide future reward generation.

More on tables

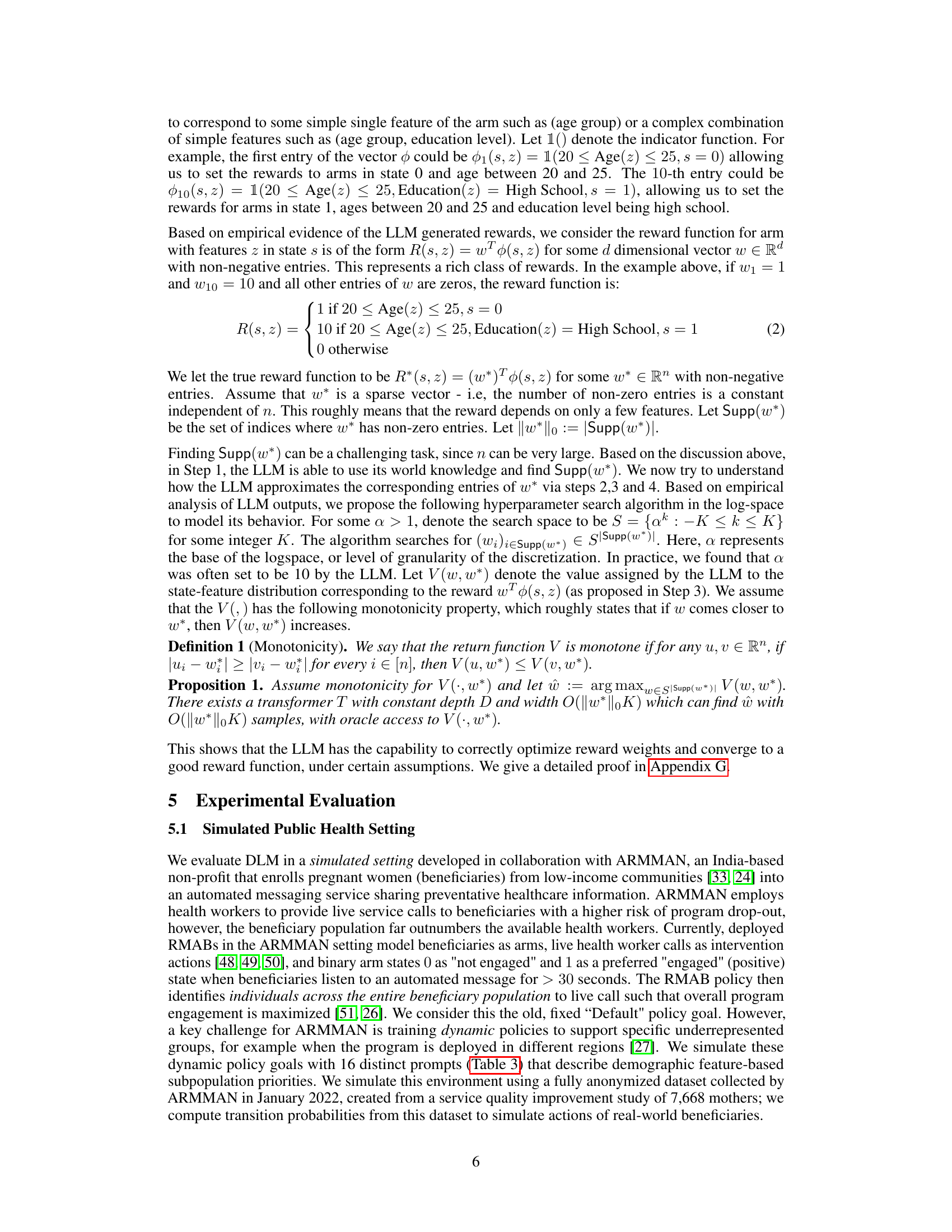

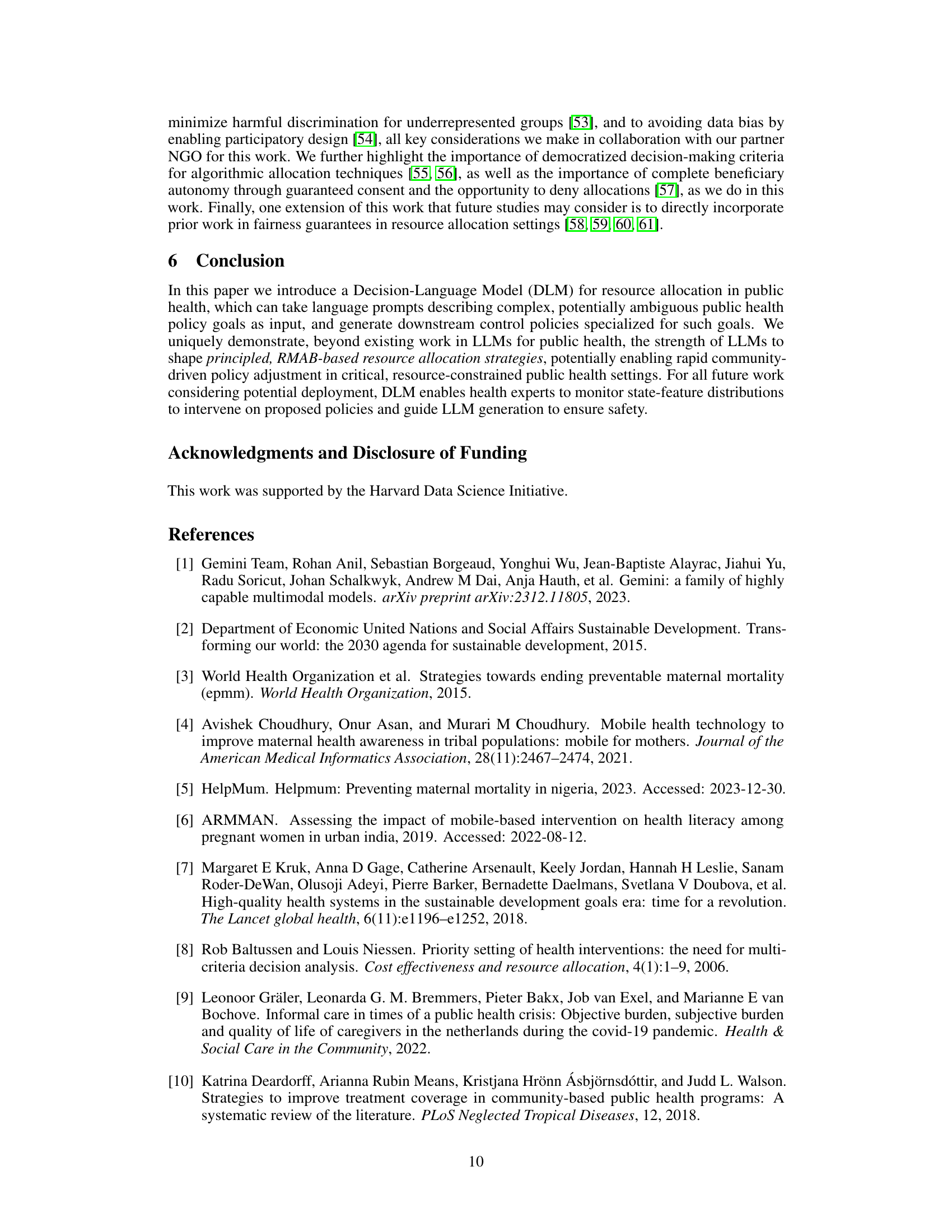

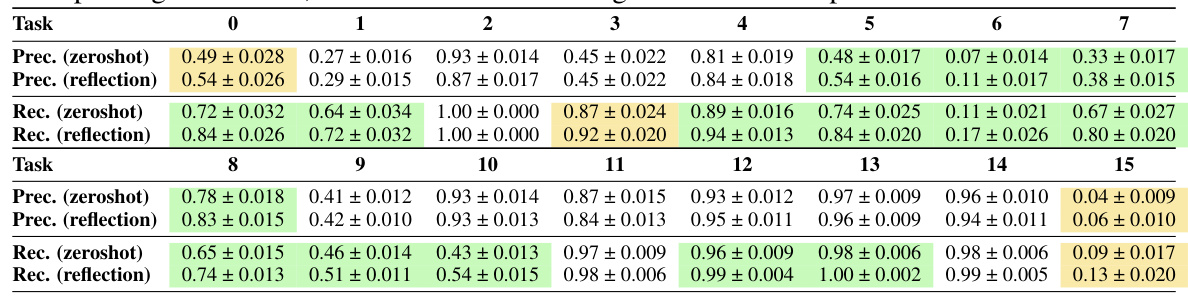

🔼 This table shows the precision and recall of features used by LLMs in generating reward functions, compared to the ground truth Base reward functions. It compares the performance of the zeroshot DLM (without reflection) and the DLM with reflection. Cells highlighted in yellow indicate improvements from reflection with a p-value less than 0.1, while green cells show improvements with a p-value less than 0.05. The results suggest LLMs are effective at extracting features for reward function design, and that the reflection module is especially helpful in enhancing recall.

read the caption

Table 1: Average precision/recall of features used in LLM-proposed reward functions compared to ground truth Base reward function. Comparison between zeroshot DLM (No Reflection) and DLM (Reflection). Cells in yellow showed improvement from Reflection with p < 0.1; cells in green showed improvement from Reflection with p < 0.05. Results indicate LLMs are very effective feature extractors for reward function generation. Furthermore, the Reflection module is particularly useful for improving recall rates, as 13/16 tasks showed significant recall improvement with Reflection.

🔼 This table lists sixteen different tasks used to evaluate the proposed DLM model. Each task is defined by a human-language prompt describing a specific policy goal (e.g., prioritizing older mothers or low-income beneficiaries). The table also shows the corresponding ground truth Base reward function for each task, which represents the ideal reward function aligned with the prompt’s intention. This table is crucial for understanding the evaluation setup, showcasing the range of objectives addressed and the corresponding reward functions used as a baseline to compare the performance of the LLM-generated reward functions.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

🔼 This table lists sixteen different tasks used to evaluate the proposed DLM model. Each task represents a specific policy objective in maternal healthcare, focusing on various demographic groups such as older mothers, low-income families, and those with limited access to technology. The ‘Full Prompt’ column provides the natural language description used to guide the DLM model, while the ‘Base Reward Function’ column specifies the ground truth reward function corresponding to each task, expressed as a Python lambda function.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

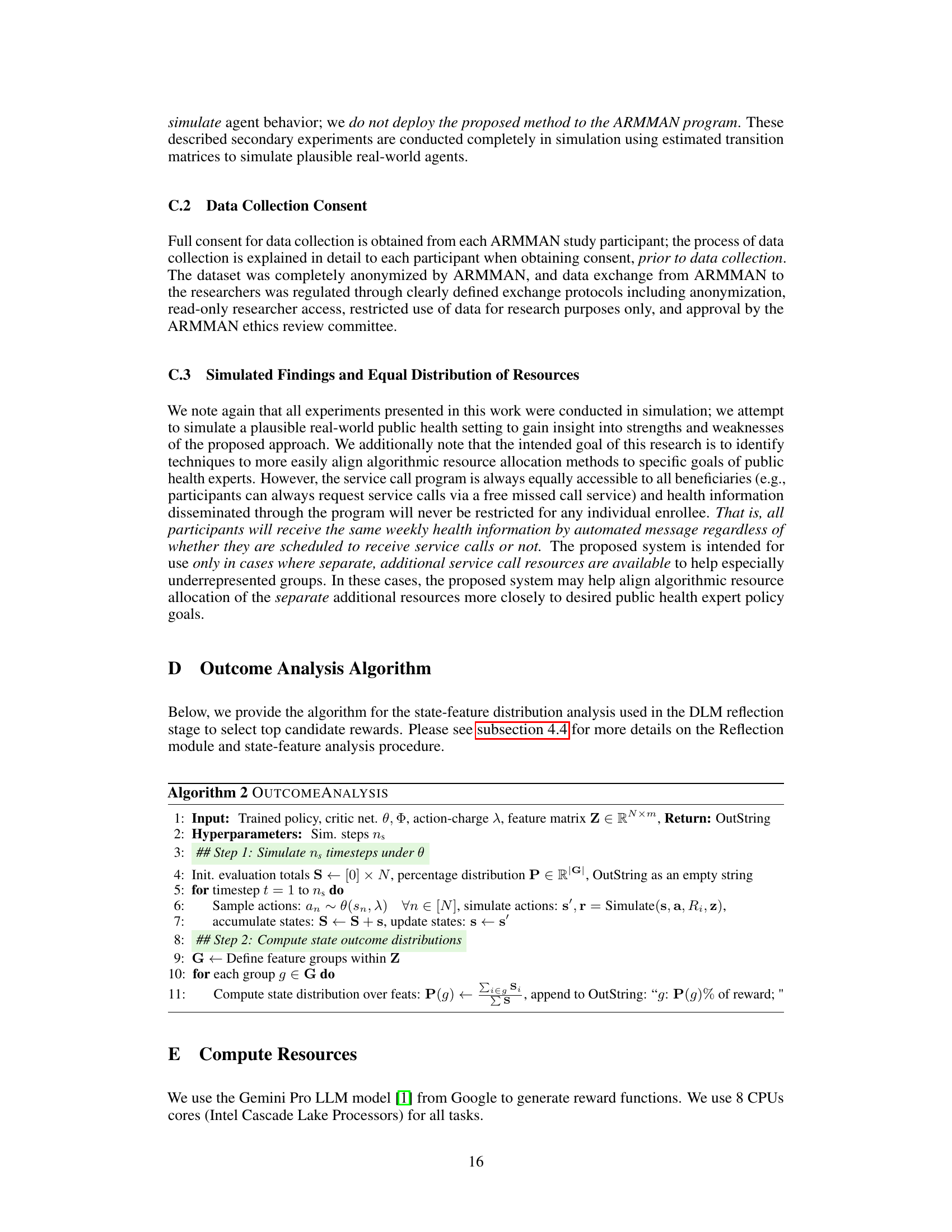

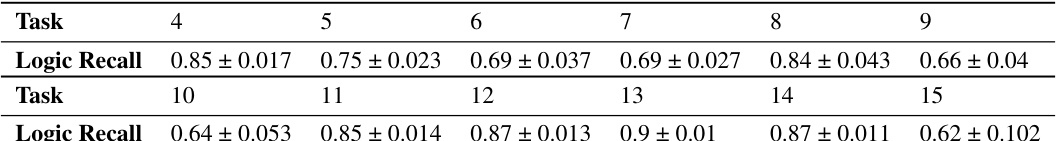

🔼 This table presents the recall of logical combinations of features for prompts 4-15 in the experiment. The recall is a measure of how well the LLM-generated reward functions capture the features used in the ground truth (Base) reward functions. Only LLM generations that included at least the features in the Base reward are considered.

read the caption

Table 2: Recall of logical combinations of features for multi-feature prompts. We consider multi-feature prompts 4–15, and report the recall compared to Base reward for accurately emulating behavior of Base reward. Note that we consider only LLM generations with high feature recall, i.e. those proposed rewards that include, at minimum, the features used in the corresponding ground truth Base reward.

🔼 This table presents 16 different tasks used in the experiments. Each task is defined by a prompt that describes a specific policy goal. The prompts are designed to target different features such as age, income, language, education, and call times. Each task also includes the corresponding ground truth base reward function. The base reward functions are used to evaluate the performance of the proposed DLM and are considered the ‘gold standard’.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

🔼 This table lists 16 different tasks (prompts) used to evaluate the DLM model. Each task describes a specific policy goal for resource allocation, focusing on different demographic subpopulations (e.g., older mothers, low-income families, Hindi speakers). The table also provides the corresponding ground truth Base reward function for each task, which serves as the target for the LLM to achieve through reward function generation.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

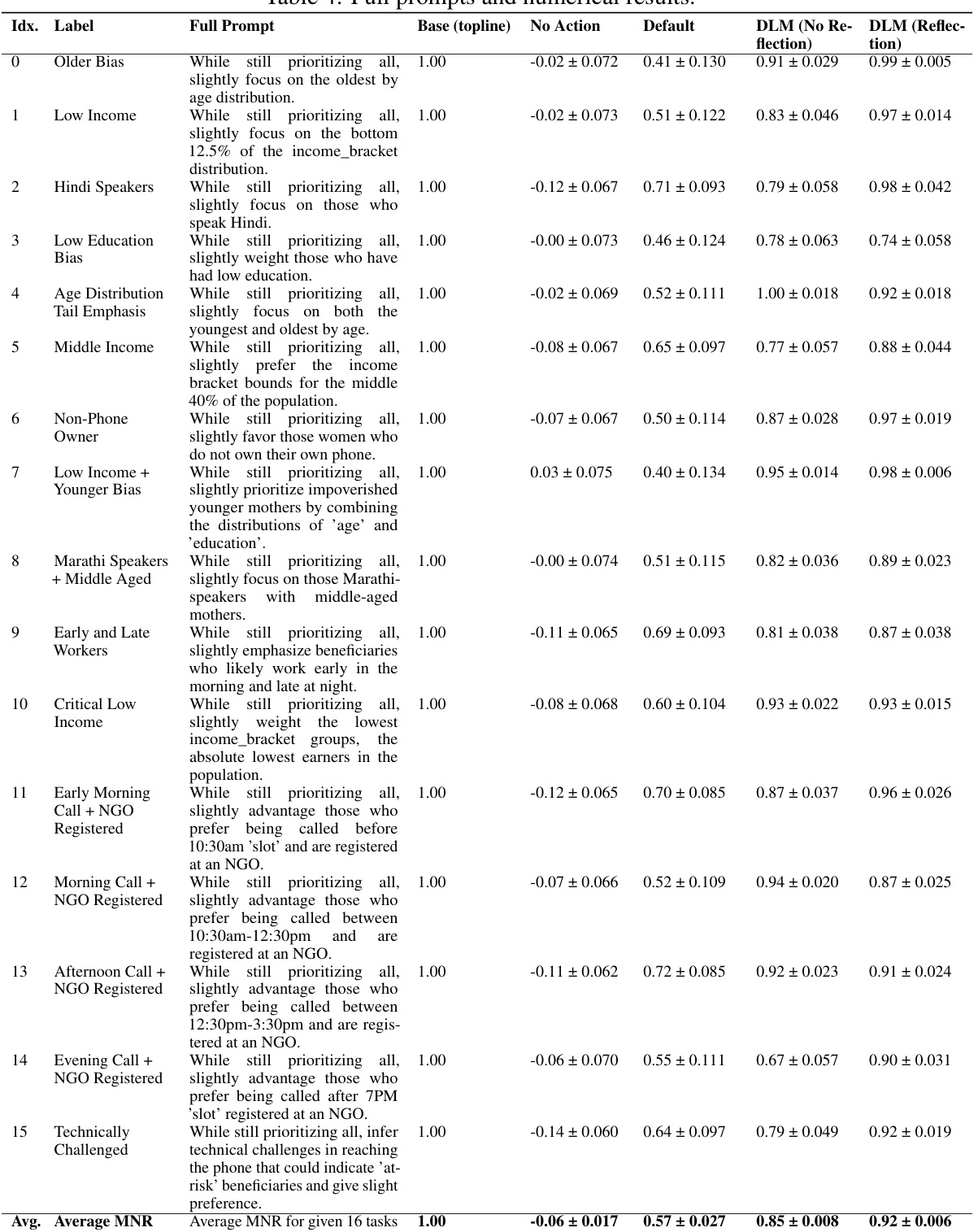

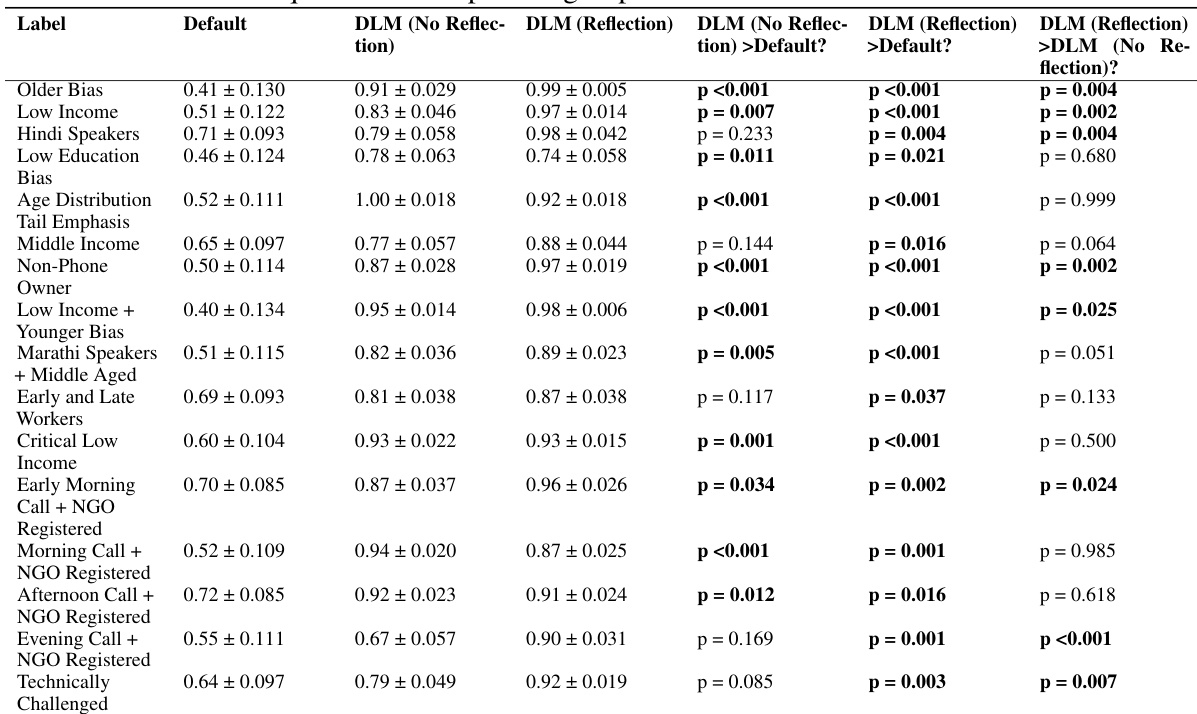

🔼 This table presents the results of the experiments conducted in the paper. It shows the mean normalized reward (MNR) for each of the 16 tasks (prompts) for different methods: Base reward, No Action, Default, DLM (No Reflection), and DLM (Reflection). The Base reward is the ground truth reward, No Action represents a policy that does not take any action, Default is the original (fixed) reward function, DLM (No Reflection) is the proposed method without the self-reflection stage, and DLM (Reflection) is the proposed method with self-reflection. The table also includes statistical significance tests comparing MNR scores.

read the caption

Table 4: Full prompts and numerical results.

🔼 This table lists the 16 different tasks used in the experiments. For each task, it provides a description of the prompt given to the LLM, along with the corresponding base reward function used for evaluation. The prompts vary in terms of prioritizing specific demographic groups (e.g., older mothers, low-income mothers) or other aspects like preferred call times. The base reward functions are used to measure the performance of the LLM-generated reward functions against a human-defined benchmark, where a reward of 1 represents a perfect alignment with the human goal.

read the caption

Table 3: Full task list and ground truth Base reward functions.

Full paper#