TL;DR#

Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQs) have shown promising empirical results, surpassing traditional neural networks in various applications. However, a comprehensive theoretical understanding of their capabilities and limitations remains elusive. This research paper tackles this challenge by providing a rigorous theoretical analysis of DEQs, focusing on their expressive power and learning dynamics. The paper addresses the lack of theoretical understanding about when DEQs are preferable to traditional networks.

The researchers achieve this by proposing novel separation results which demonstrate the superior expressive power of DEQs. They also characterize the implicit regularization induced by gradient flow in DEQs, offering explanations for their observed benefits. Through this analysis, they propose a conjecture that DEQs are particularly advantageous in handling high-frequency components. These findings contribute significantly to the theoretical foundation of DEQs, clarifying their strengths and limitations and paving the way for more efficient model design and improved generalization in various deep learning applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep learning and neural networks due to its novel theoretical analysis of deep equilibrium models (DEQ). It addresses a critical gap in understanding DEQ’s capabilities and limitations compared to traditional feedforward networks. The findings offer valuable insights into DEQ’s expressive power and learning dynamics, opening up new avenues for improving model design and generalization. Understanding these theoretical underpinnings is pivotal for effectively leveraging DEQs in real-world applications and guiding future research.

Visual Insights#

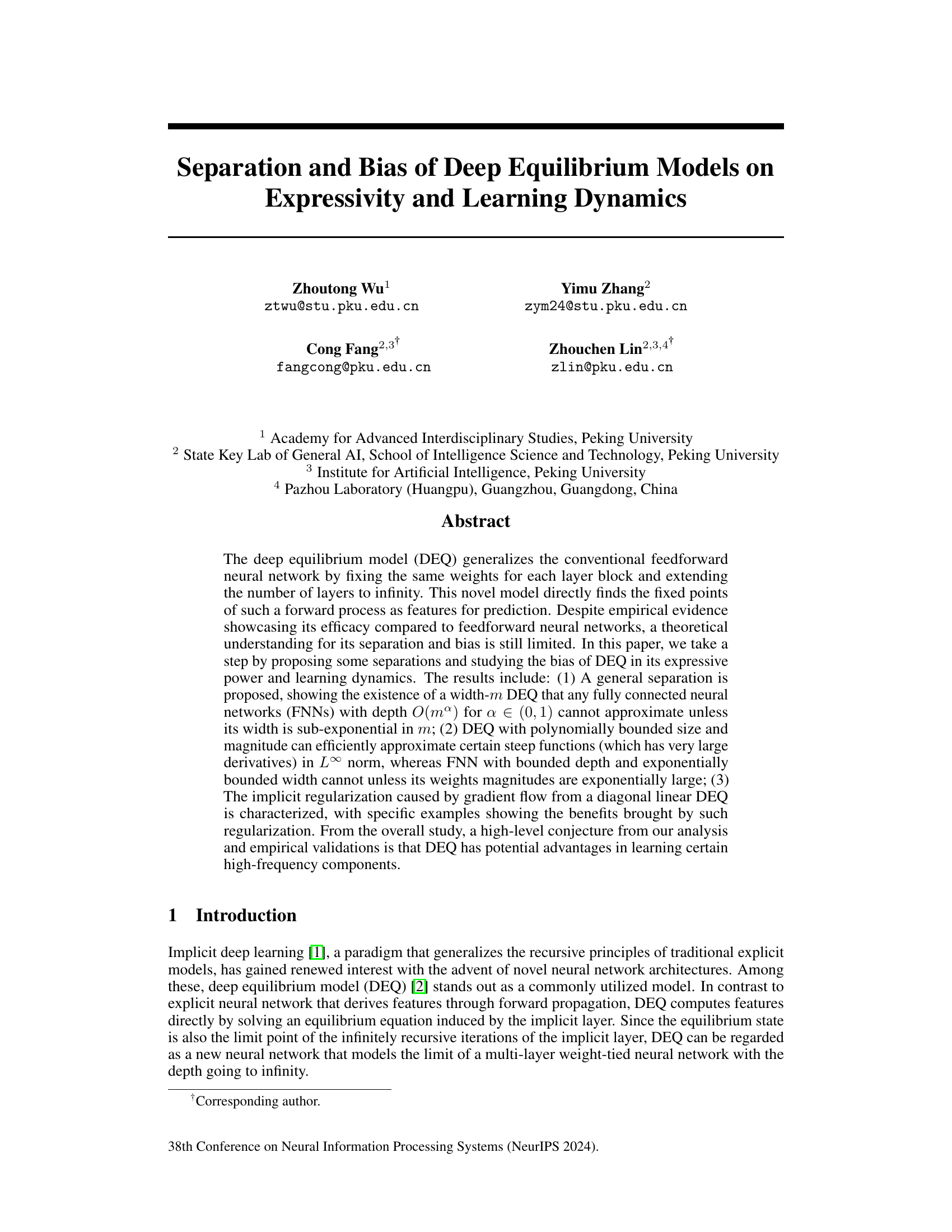

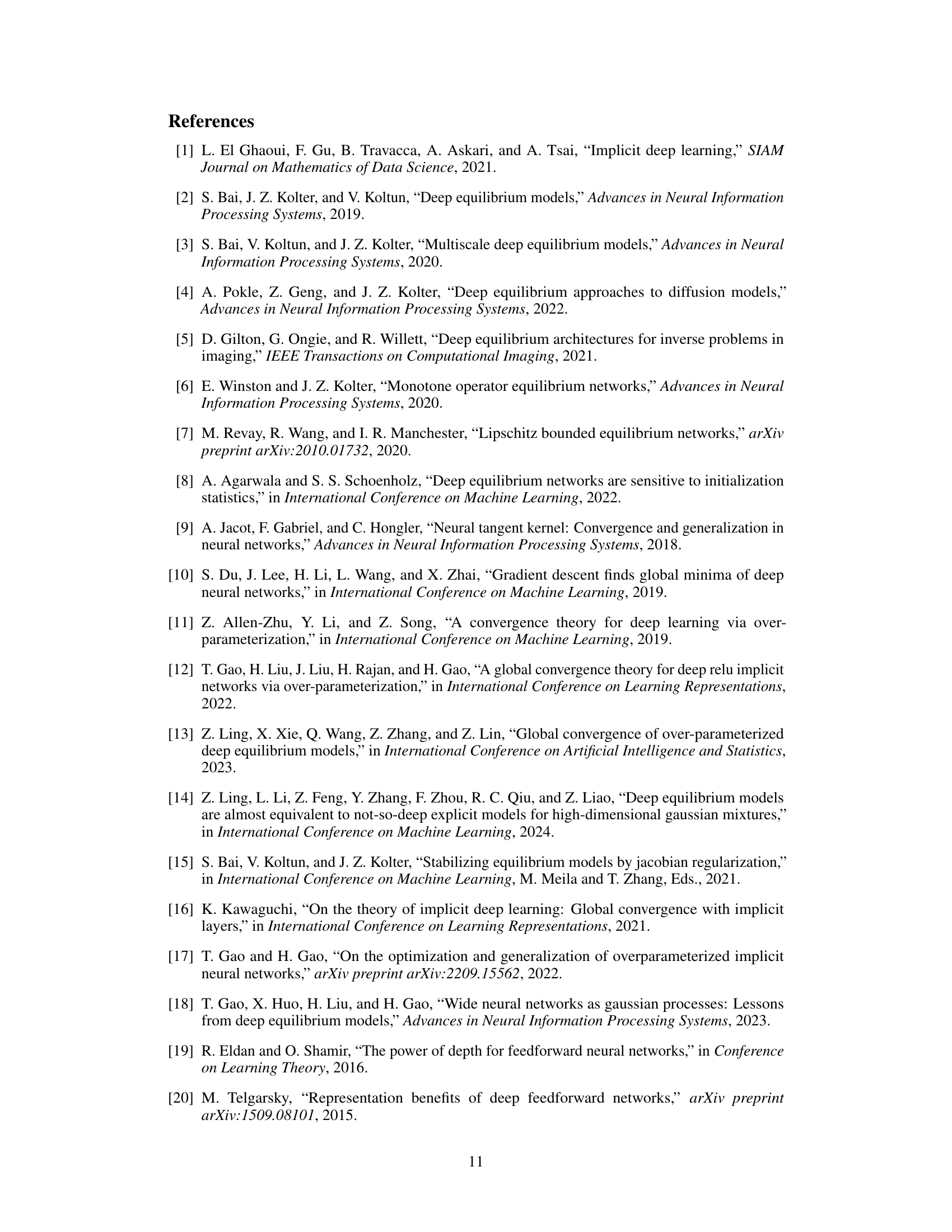

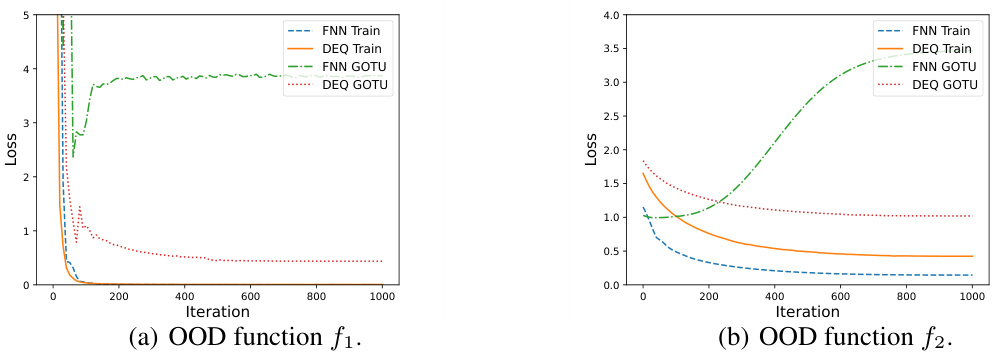

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) and Deep Equilibrium models (DEQ) on six different tasks. The first two are the sawtooth functions with varying numbers of linear regions, showcasing expressivity. The next two involve approximating a steep function, highlighting DEQ’s ability to handle such functions. The final two demonstrate the out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization performance on Boolean functions, comparing training loss and GOTU error. Different network sizes and depths (width W and depth L) are tested to demonstrate the parameter efficiency of DEQ.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test losses of FNN and DEQ networks with various width W and depth L. (a) and (d) apply Sawtooth function I and II with 25 and 210 linear regions, respectively. (b) and (e) apply function g(x) defined in Eq. (5) with d = 2-10 and δ = 2-20, respectively. (c) and (f) show the train loss and the GOTU error of FNN and DEQ on the boolean function f1, f2 with unseen domain given by Eq. (14) and Eq. (15).

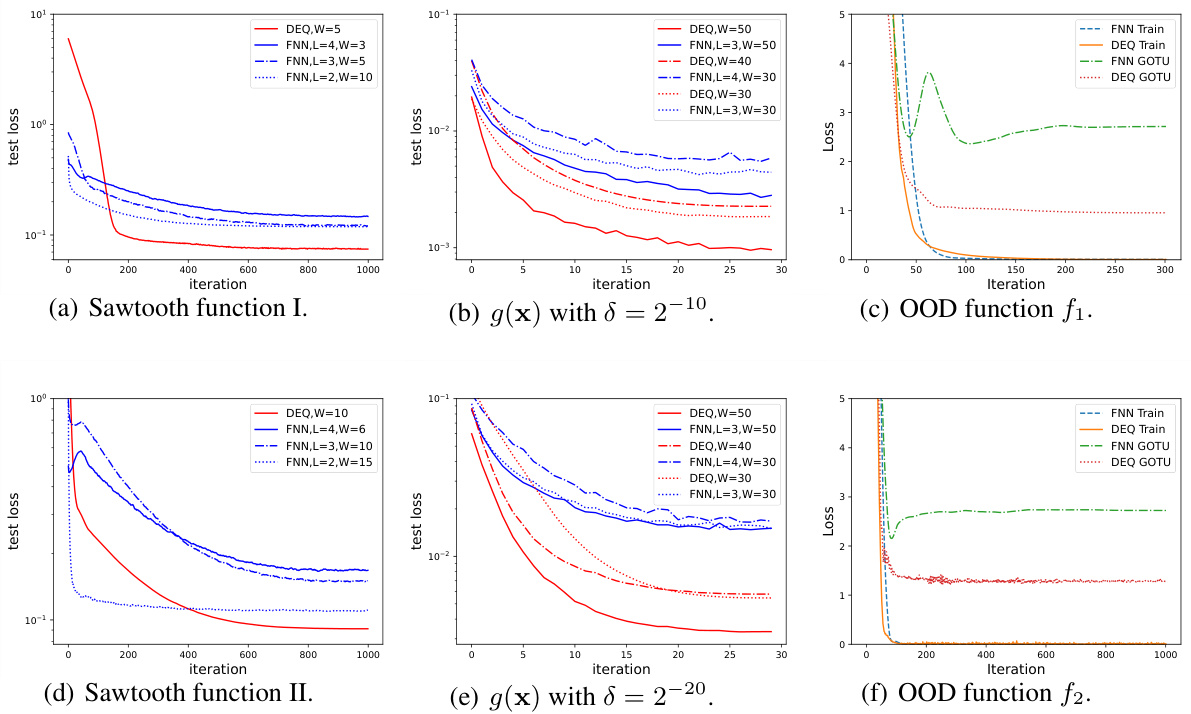

🔼 This table shows the training settings used for comparing DEQ and FNN on a sawtooth function with 25 linear regions. The goal was to maintain a similar number of FLOPs (floating point operations) per iteration for each model type while varying the network architecture (depth and width). This allowed the authors to isolate the impact of network architecture on performance rather than differences in computational cost.

read the caption

Table 1: Training settings of experiment. We apply DEQ with width-10 and FNN trained on sawtooth target function with 25 linear regions while keeping FLOPs per iteration similar.

In-depth insights#

DEQ Expressivity#

The study of DEQ expressivity revolves around understanding its capacity to approximate functions, comparing it to traditional feedforward neural networks (FNNs). A key finding highlights DEQ’s ability to efficiently approximate functions with numerous linear regions, a feat challenging for shallower FNNs. This suggests DEQs might excel in scenarios requiring complex piecewise-linear representations. The research also investigates DEQ’s power to approximate steep functions, demonstrating that DEQs, even with polynomially bounded size and weight magnitudes, can effectively approximate certain steep functions that pose significant challenges for bounded-depth FNNs. This implies a potential bias toward functions with significant changes in gradient, indicating superior performance on tasks involving high-frequency components or complex dynamics. However, general separation theorems are established, revealing that there exist functions that significantly outmatch FNN’s approximation capabilities. This nuanced perspective underscores DEQ’s strengths in specific contexts, but acknowledges its limitations in others. Ultimately, the study reveals that DEQ expressivity is not simply a matter of surpassing FNNs universally but rather a demonstration of specialized capabilities in certain functional domains.

DEQ Learning Bias#

The concept of “DEQ Learning Bias” refers to the inherent tendencies or predispositions exhibited by Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQs) during the learning process. Unlike conventional feedforward neural networks, DEQs find a fixed point solution, which implicitly introduces regularization. This regularization, a form of learning bias, steers the model towards specific solutions, impacting expressivity and generalization. A key aspect is the influence of the fixed-point iteration process on the model’s learned features. The bias can manifest as a preference for certain high-frequency components or a tendency towards ‘dense’ feature representations. Analyzing this bias requires investigation of both the implicit regularization imposed by the DEQ framework and the specific optimization dynamics during training. Understanding the DEQ learning bias is crucial for determining the strengths and limitations of DEQs, particularly when compared to conventional neural networks. It helps explain why DEQs might outperform traditional architectures on specific tasks involving high-frequency information while potentially struggling in others. Further research should focus on quantifying and characterizing the learning bias to provide a more precise understanding of when DEQs will excel and where their limitations are most apparent. This involves exploring the interaction between network architecture, optimization algorithms, and the inherent properties of the fixed-point problem itself.

FNN vs. DEQ#

The core of this research lies in contrasting Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs) with Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQs). DEQs offer a unique approach by solving an equilibrium equation to determine features, unlike FNNs’ iterative feedforward computations. This study explores the implications of this fundamental difference, focusing on expressiveness and learning dynamics. The authors demonstrate that DEQs can efficiently approximate certain functions—especially those with many linear regions or steep gradients—that pose challenges for FNNs, even when both models have comparable sizes. However, the paper also highlights limitations of DEQs. The theoretical advantages are shown using specific examples, but practical considerations—such as computational cost—are not fully analyzed. Therefore, the study suggests that DEQs might provide advantages in specific applications, particularly those involving high-frequency components or implicitly defined functions, while acknowledging the need for further research to fully understand DEQs’ capabilities and limitations compared to FNNs.

OOD Generalization#

Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization, a critical aspect of robust machine learning, examines a model’s ability to generalize to data that differs significantly from its training distribution. This is crucial because real-world data is rarely stationary and often includes unexpected variations. The paper investigates this challenge within the context of Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQs), exploring whether DEQs exhibit inherent biases or properties that facilitate better OOD performance. A key question is whether DEQs’ implicit regularization—arising from the equilibrium-seeking process—leads to features less sensitive to distributional shifts compared to traditional neural networks. The analysis likely explores whether DEQs, due to their infinite-depth architecture and weight tying, implicitly prefer solutions with certain characteristics (like dense representations or specific frequency sensitivities) making them more robust to OOD examples. Experimental validation probably involves comparison against standard neural networks (FNNs) on carefully designed OOD benchmarks. The results may show improved OOD generalization in DEQs, possibly attributed to implicit regularization effects and the inherent bias of their equilibrium-seeking process, but potentially also highlighting specific limitations in their OOD capabilities. Further research could focus on dissecting the nature of this DEQ-specific bias and designing improved training strategies to optimize OOD performance in DEQs and other neural network architectures.

Future of DEQ#

The future of Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQs) is promising, but hinges on addressing current limitations. Improving the theoretical understanding of DEQs’ expressiveness and implicit biases is crucial, particularly concerning high-frequency components and out-of-distribution generalization. This requires a deeper exploration of their learning dynamics beyond the current lazy training regime, analyzing their behavior in overparameterized settings. Developing more efficient training algorithms and parameterization techniques is vital for wider adoption; current methods often suffer from slow convergence and difficulty in ensuring well-posedness. Exploring hybrid architectures that combine the strengths of DEQs with other neural network types could unlock significant potential, enhancing their capabilities for diverse applications. Finally, broader adoption and applications will depend on demonstrating consistent empirical advantages over existing methods across a wider range of tasks, alongside the development of user-friendly tools and libraries.

More visual insights#

More on figures

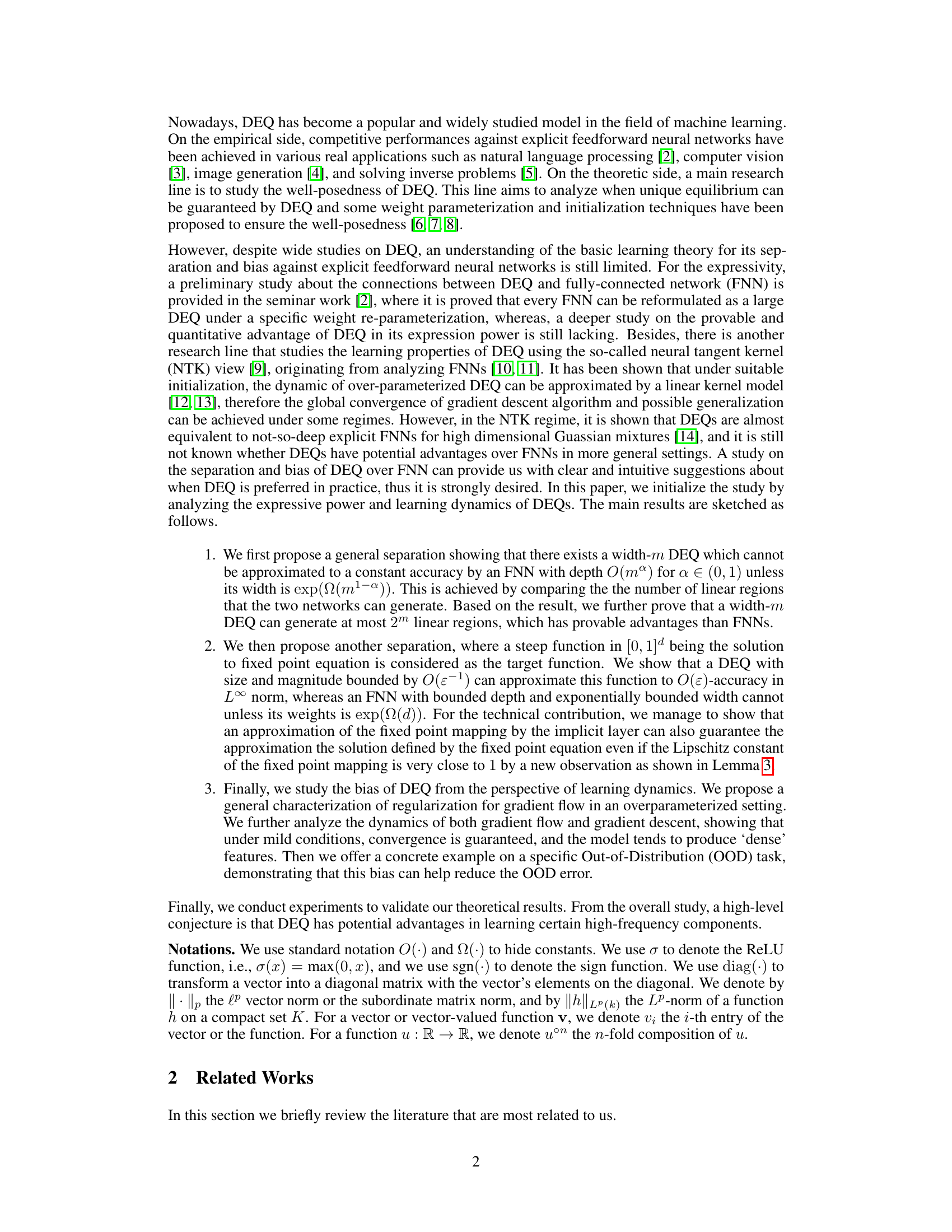

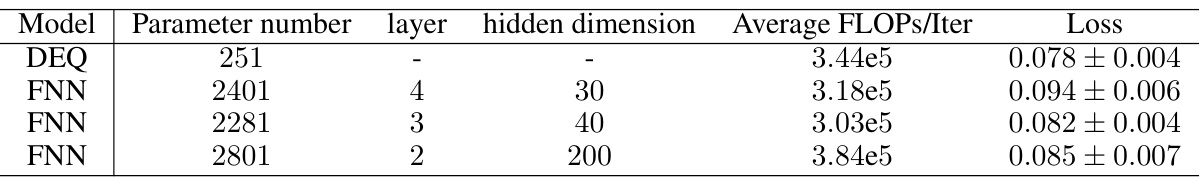

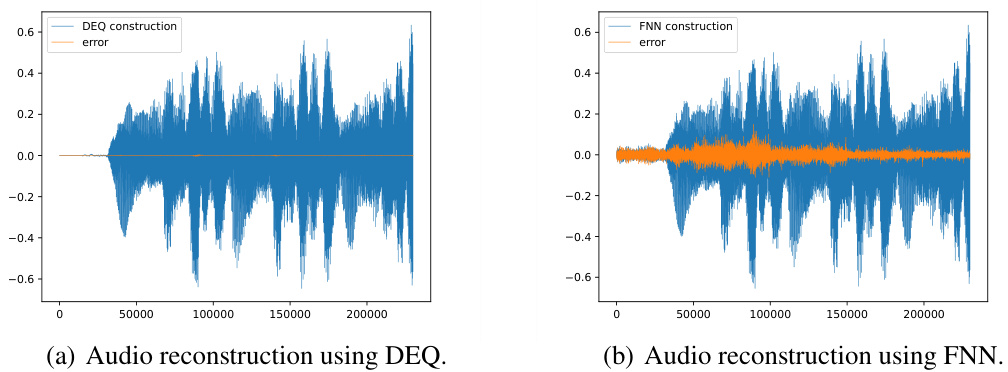

🔼 This figure compares the feature distributions learned by three different models: a diagonal linear DEQ, a vanilla DEQ, and an FNN. Each heatmap shows the magnitude of 20 features; darker colors indicate smaller magnitudes. The purpose is to visually demonstrate a difference in the implicit bias of DEQs, showing they tend to learn features with relatively similar magnitudes compared to FNNs.

read the caption

Figure 2: The heatmaps of diagonal DEQ, vanilla DEQ and FNN. We dispaly the magnitude of feature z of DEQ and the magnitude of feature before the fully-connented layer of FNN. The x-axis represents features 1-20 and darker colors indicate smaller features.

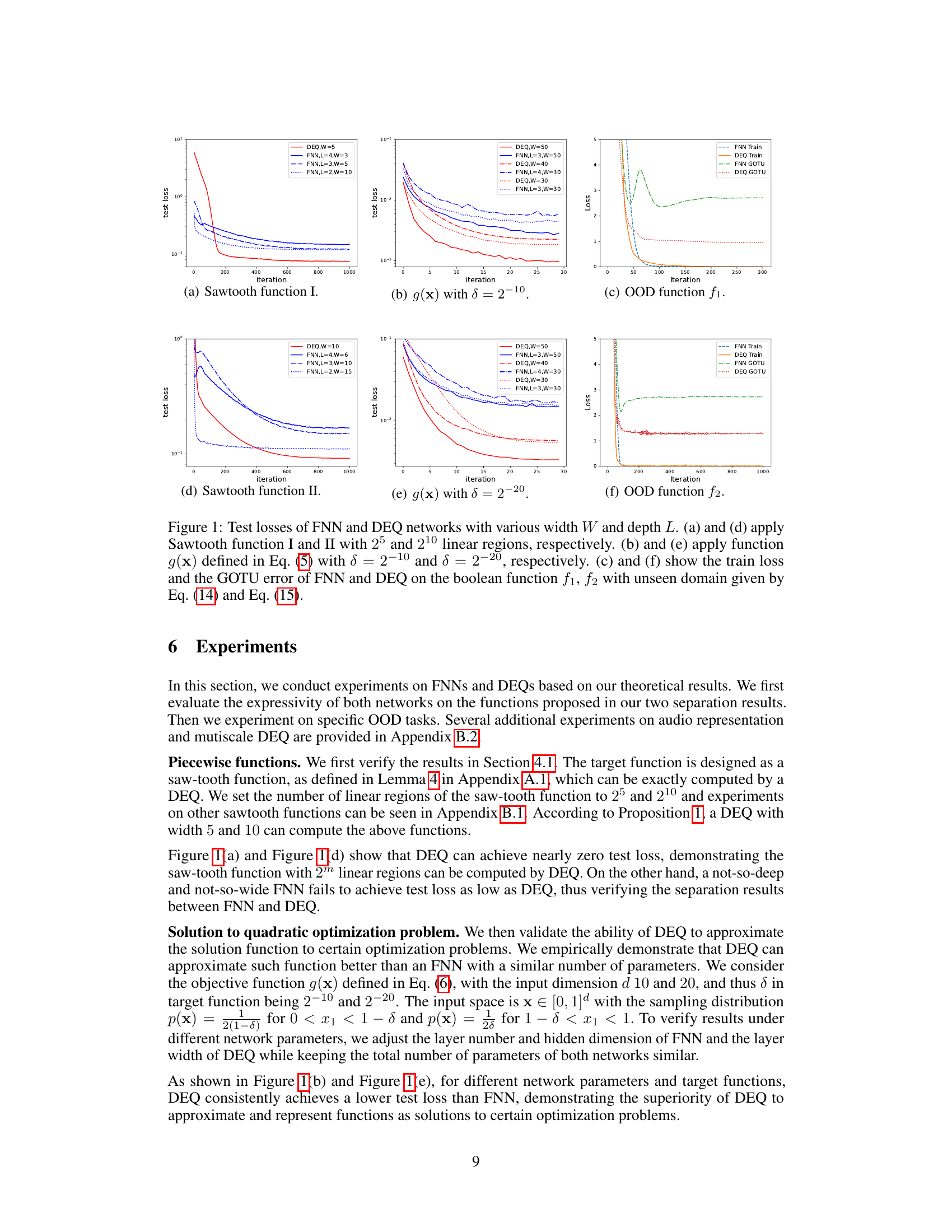

🔼 This figure displays the test loss curves for both Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) and Deep Equilibrium models (DEQ) trained on sawtooth functions with varying numbers of linear regions (2¹, 2³, 2¹⁵). The results demonstrate the superior performance of DEQs in approximating functions with a large number of linear regions, a key finding supporting the paper’s claim about DEQ’s enhanced expressiveness.

read the caption

Figure 3: Test loss of FNN and DEQ trained on sawtooth functions with 21, 23, 215 linear regions.

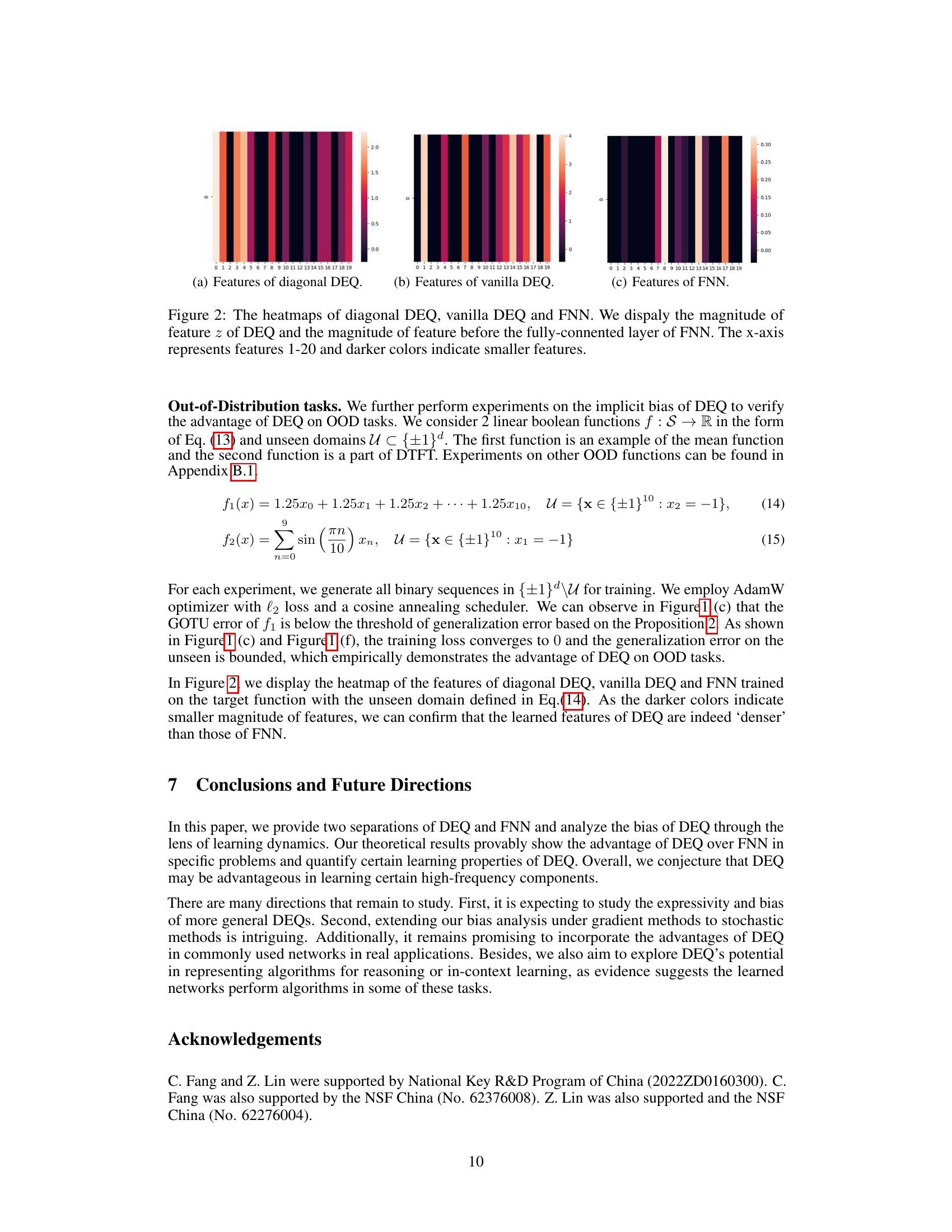

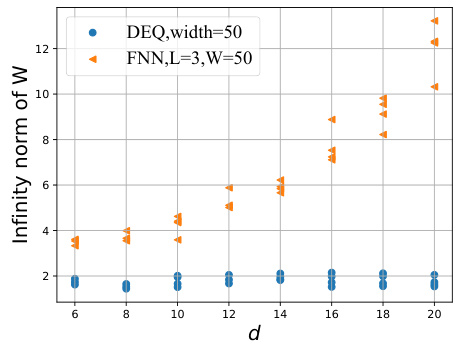

🔼 This figure compares the infinity norm of the weights of DEQ and FNN models trained on steep target functions with different input dimensions (d). The results show that DEQ maintains relatively small weights even when the input dimension increases, while FNN’s weights grow significantly.

read the caption

Figure 4: Results on steep target functions applying DEQ and FNN with comparable performance on loss. We plot the infinity norm of the weights of DEQ and FNN with d = 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) and Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQ) on six different tasks. The tasks are designed to highlight the relative strengths of each model architecture, testing expressivity (sawtooth functions and steep functions) and generalization (out-of-distribution, or OOD, tasks on boolean functions). The results show that DEQ is more parameter-efficient and demonstrates better generalization performance for certain tasks, consistent with the paper’s theoretical findings.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test losses of FNN and DEQ networks with various width W and depth L. (a) and (d) apply Sawtooth function I and II with 25 and 210 linear regions, respectively. (b) and (e) apply function g(x) defined in Eq. (5) with d = 2-10 and δ = 2-20, respectively. (c) and (f) show the train loss and the GOTU error of FNN and DEQ on the boolean function f1, f2 with unseen domain given by Eq. (14) and Eq. (15).

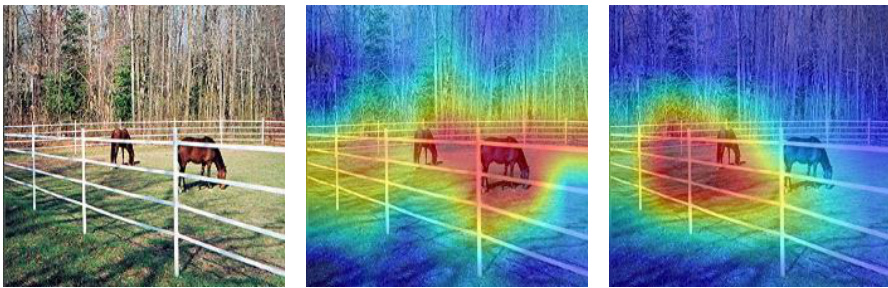

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of saliency maps generated by Multiscale DEQ (MDEQ) and ResNet-50. Saliency maps highlight the image regions most influential in a model’s prediction. The images show that MDEQ attends to a broader range of features (e.g., fences, trees) compared to ResNet-50, which focuses more narrowly on the horses. This supports the paper’s claim that DEQs learn ‘denser’ features.

read the caption

Figure 6: The saliency map of Multiscale DEQ (MDEQ) and ResNet.

🔼 The figure shows the saliency map generated by Grad-CAM for both MDEQ and ResNet-50 on images of horses and dogs. The saliency map highlights image regions that contribute the most to the model’s prediction. The comparison aims to illustrate that MDEQ produces a more distributed set of salient features compared to ResNet-50, which tends to focus on a smaller number of regions. This supports the paper’s argument that DEQs are biased towards learning dense features.

read the caption

Figure 6: The saliency map of Multiscale DEQ (MDEQ) and ResNet.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) and Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQ) on six different tasks, showcasing DEQ’s potential advantages in specific scenarios. The tasks involve approximating functions with varying complexities, including those with many linear regions (sawtooth functions) and steep functions (g(x)). Additionally, the figure illustrates the performance on out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks, where the models are evaluated on data unseen during training. The results suggest that DEQ outperforms FNN in several cases, particularly when approximating functions with high complexity or when handling OOD data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test losses of FNN and DEQ networks with various width W and depth L. (a) and (d) apply Sawtooth function I and II with 25 and 210 linear regions, respectively. (b) and (e) apply function g(x) defined in Eq. (5) with d = 2-10 and 8 = 2-20, respectively. (c) and (f) show the train loss and the GOTU error of FNN and DEQ on the boolean function f1, f2 with unseen domain given by Eq. (14) and Eq. (15).

Full paper#