↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current prompting methods for large language models (LLMs) struggle with generalizability and consistency, often relying on instance-specific solutions that lack task-level consistency. This limits their applicability to diverse problems. Researchers need more robust and adaptable prompting techniques.

This paper introduces StrategyLLM, a framework that uses four LLM agents: a strategy generator, executor, optimizer, and evaluator to address the limitations of existing methods. It automatically generates strategy-based few-shot prompts, significantly improving LLM performance on math, commonsense, algorithmic, and symbolic reasoning tasks. The framework demonstrates notable advantages across various LLMs and scenarios, highlighting its robustness and effectiveness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it introduces a novel and effective framework, StrategyLLM, for improving LLM problem-solving abilities. StrategyLLM addresses the issues of generalizability and consistency in current prompting methods by automatically generating, evaluating, optimizing, and selecting effective problem-solving strategies for various tasks. This framework is not only efficient and cost-effective but also demonstrates significant performance gains across multiple challenging tasks. The work opens new avenues for research into multi-agent collaboration within LLMs and automated prompt engineering.

Visual Insights#

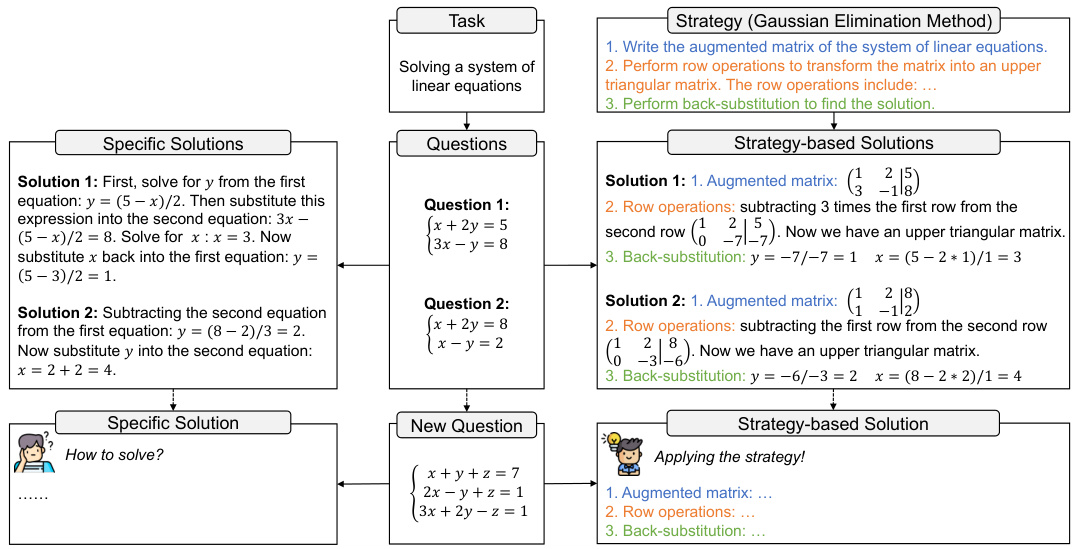

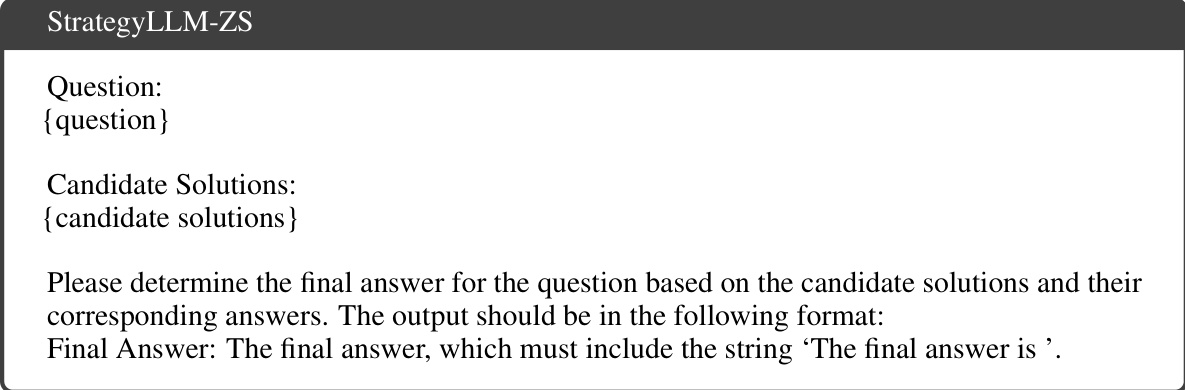

🔼 This figure compares two approaches to solving a system of linear equations: using specific solutions and using strategy-based solutions. The left side shows two different specific solutions for two different instances of the problem, highlighting the lack of consistency and generalizability in this approach. The right side demonstrates the use of a general strategy (Gaussian Elimination Method), applying it consistently across different problem instances. This strategy-based approach provides a more consistent and generalizable solution method for LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of specific solutions and strategy-based solutions.

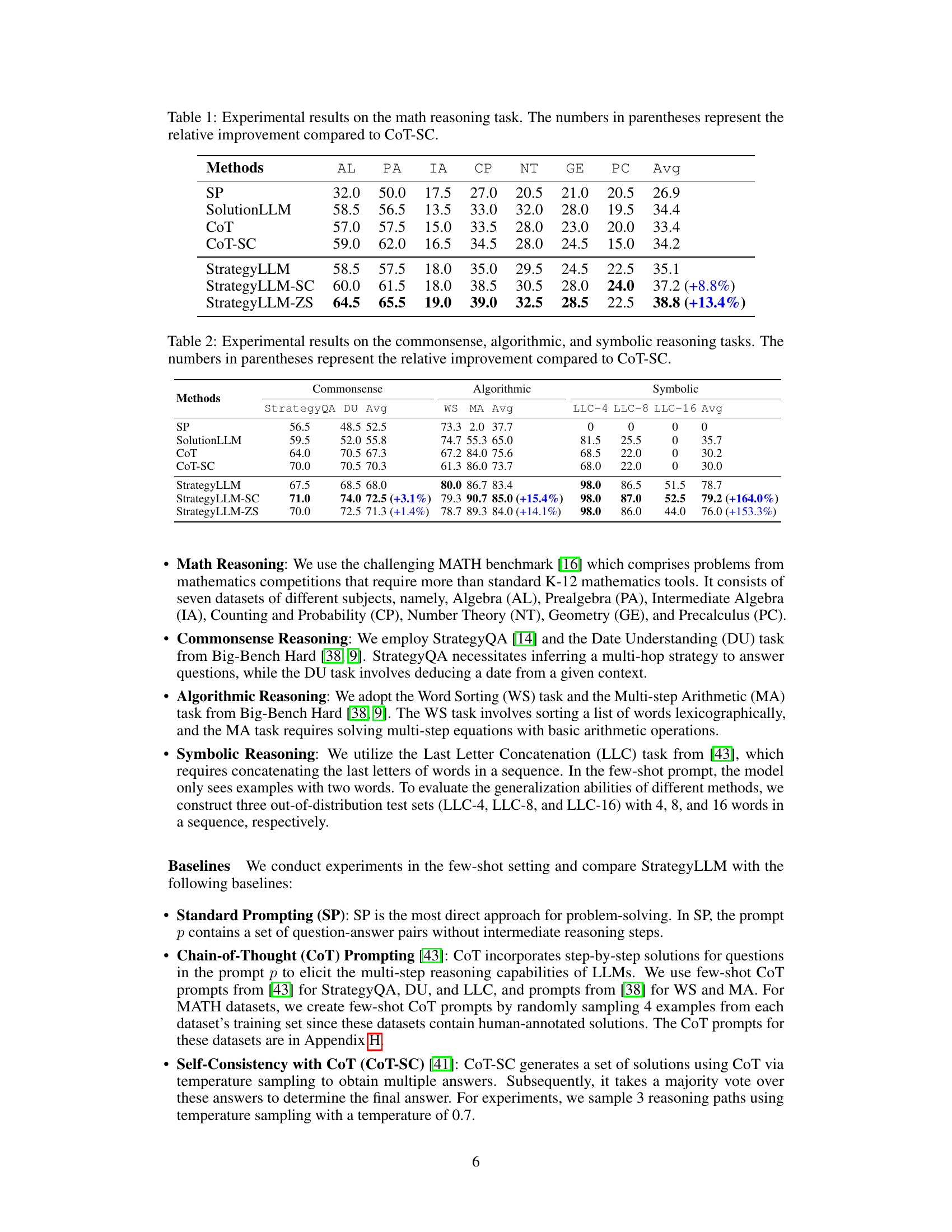

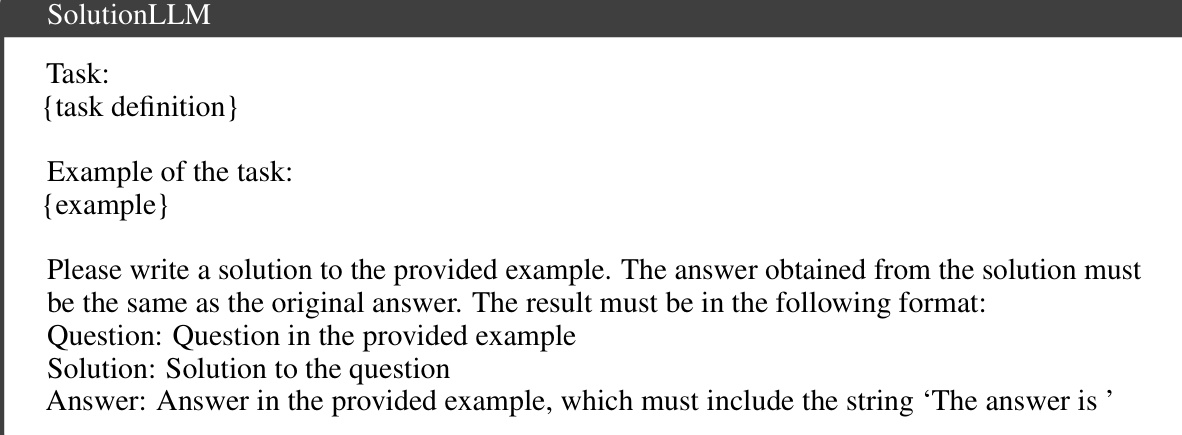

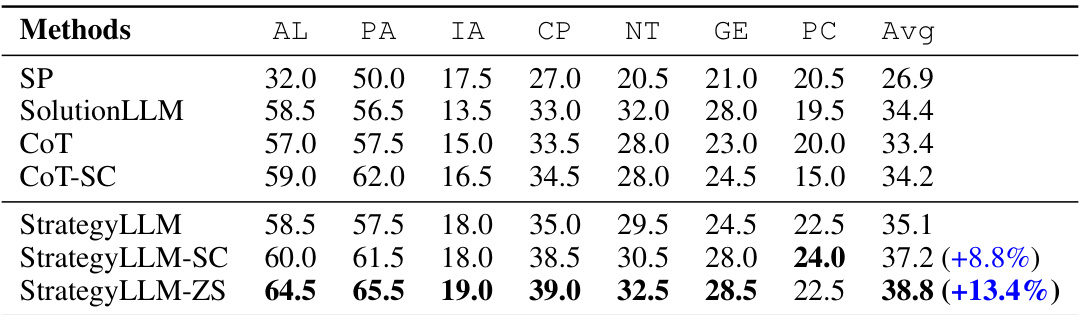

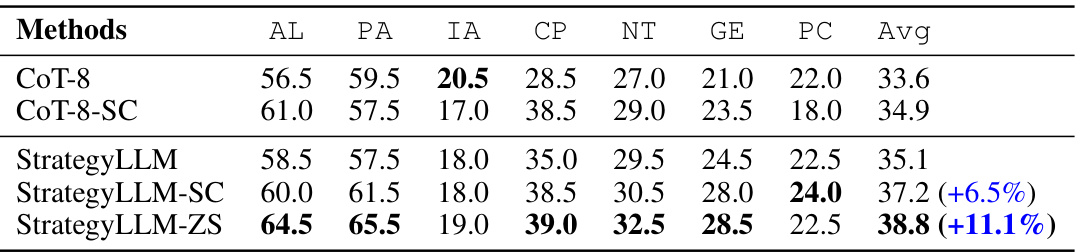

🔼 This table presents the performance of different methods on the math reasoning task, comparing their average accuracy across seven sub-datasets (Algebra, Prealgebra, Intermediate Algebra, Counting and Probability, Number Theory, Geometry, and Precalculus) of the MATH benchmark. The results show StrategyLLM outperforming the other methods, particularly CoT-SC (Self-Consistency with Chain-of-Thought), which represents a strong baseline. The numbers in parentheses highlight the percentage improvement achieved by StrategyLLM over CoT-SC for each sub-dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results on the math reasoning task. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

In-depth insights#

StrategyLLM Overview#

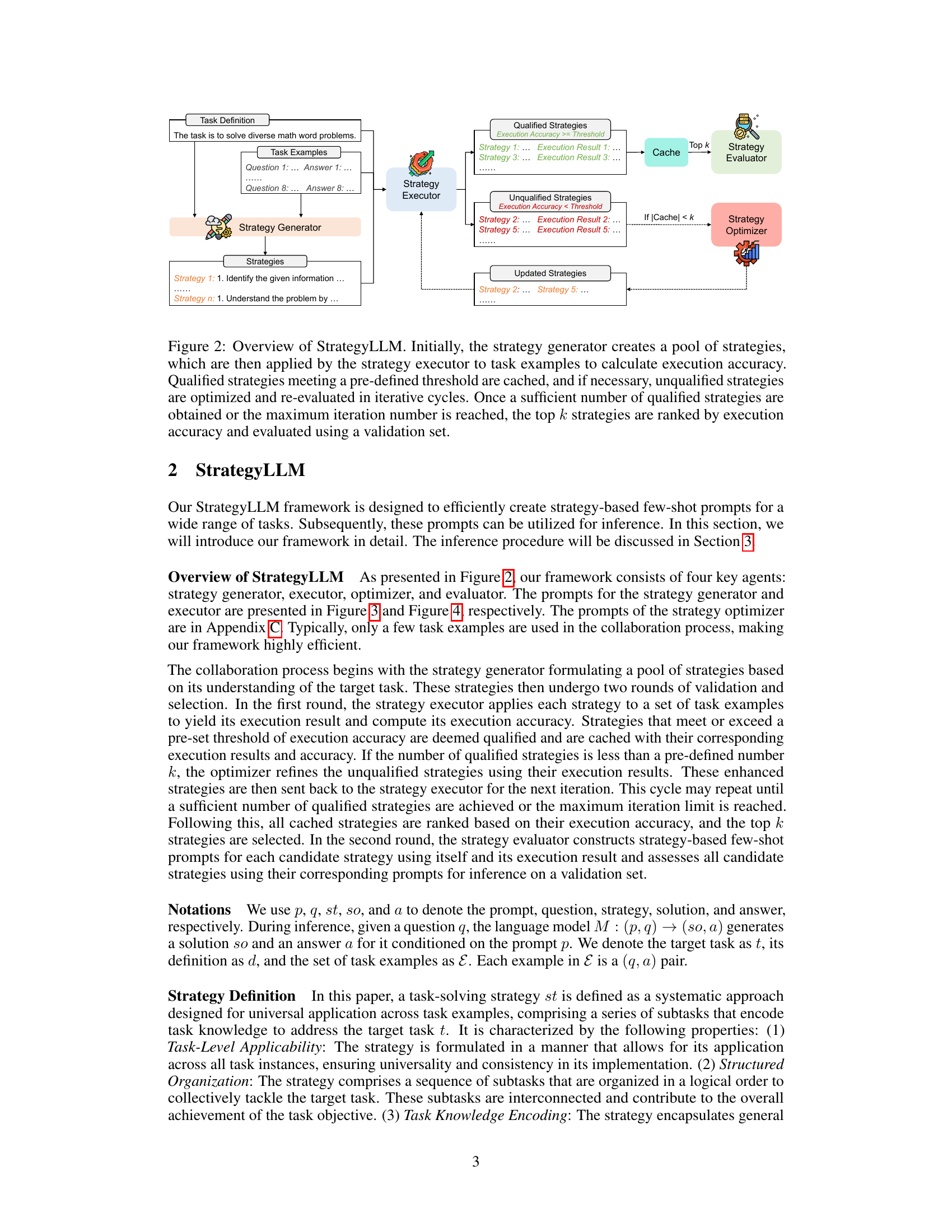

StrategyLLM is presented as a multi-agent framework for generating effective, generalizable few-shot prompts. It leverages four core LLM agents: a strategy generator (inductively deriving general strategies from examples), a strategy executor (applying strategies to new instances), a strategy optimizer (refining unsuccessful strategies), and a strategy evaluator (selecting the top-performing strategies). This framework addresses limitations of prior methods by moving beyond instance-specific solutions to produce consistent, strategy-based prompts. The inductive and deductive reasoning process inherent in StrategyLLM fosters generalizability and consistency, respectively. A key advantage is its autonomy, eliminating the need for human intervention in strategy development and selection. The entire process, including prompt generation and strategy selection, is designed for efficiency, requiring only a small number of examples. The strategy-based prompts are then used for inference on unseen test instances, making it highly cost-effective for generating effective solutions for new problems.

Multi-Agent Approach#

A multi-agent approach in a research paper typically involves designing a system where several independent agents, often based on large language models (LLMs), collaborate to solve a complex problem. Each agent specializes in a particular task, such as strategy generation, execution, optimization, or evaluation. The core strength of this approach lies in its ability to decompose a challenging problem into smaller, more manageable sub-tasks, allowing for specialized expertise and efficient parallel processing. This contrasts with single-agent methods, where a single LLM attempts to handle the entire problem, potentially leading to less robust and less accurate solutions. Effective coordination and communication between agents is crucial, often achieved through carefully designed prompts and shared information channels. The overall performance of the system depends heavily on the effectiveness of the individual agents and how well they integrate. A well-designed multi-agent system can demonstrate significant improvements in accuracy, efficiency, and generalizability compared to single-agent methods; however, challenges arise in managing the complexity of interactions and ensuring smooth collaboration among agents.

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering, in the context of large language models (LLMs), is the art and science of crafting effective prompts to elicit desired outputs. It’s a crucial aspect of harnessing the full potential of LLMs, as poorly designed prompts can lead to inaccurate, irrelevant, or nonsensical responses. Effective prompt engineering often involves techniques like chain-of-thought prompting, where the prompt guides the LLM through a step-by-step reasoning process, and few-shot learning, which provides the model with a few examples of input-output pairs before presenting the target task. The goal is to create prompts that are both generalizable and consistent, meaning they perform well across a variety of inputs and produce reliable results. This is particularly challenging due to the inherent complexity and stochasticity of LLMs. Advanced prompt engineering often leverages strategies to overcome limitations such as generalizability and consistency issues inherent in many prompting methods. Research into prompt engineering is therefore vital for advancing LLM capabilities and making them more accessible and reliable for a wide range of applications.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed StrategyLLM framework against existing state-of-the-art methods across multiple datasets and tasks. Quantitative metrics, such as accuracy, F1-score, and any task-specific evaluation measures, should be clearly reported for each method. Crucially, the results should be presented with appropriate statistical significance testing (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals) to demonstrate the robustness of the findings. The discussion should analyze whether the improvements are consistent across different datasets or if there are certain problem types where StrategyLLM excels more. Error analysis is essential; identifying failure cases and their underlying causes will greatly improve the understanding and future development. Ablation studies, demonstrating the impact of individual components of StrategyLLM (e.g., strategy generator, executor, optimizer, evaluator), are needed to justify the framework’s design choices. Finally, the section should include a discussion on the computational cost and efficiency of StrategyLLM compared to baselines, providing valuable insights into its practicality and scalability.

Future of StrategyLLM#

The future of StrategyLLM hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving the efficiency of the strategy generation process is crucial, potentially through more advanced LLM prompting techniques or reinforcement learning methods. Expanding StrategyLLM’s capabilities beyond symbolic reasoning to encompass more complex problem domains, like visual reasoning or real-world decision making, is a key area for development. Research into more robust and generalizable strategies is also essential; current strategies may be dataset-specific, limiting their broader applicability. Furthermore, exploring the integration of StrategyLLM with other AI agents and tools presents exciting possibilities, potentially leading to more sophisticated and autonomous problem-solving systems. Finally, ethical considerations concerning the use and potential biases of such a powerful system warrant careful attention as StrategyLLM continues to develop.

More visual insights#

More on figures

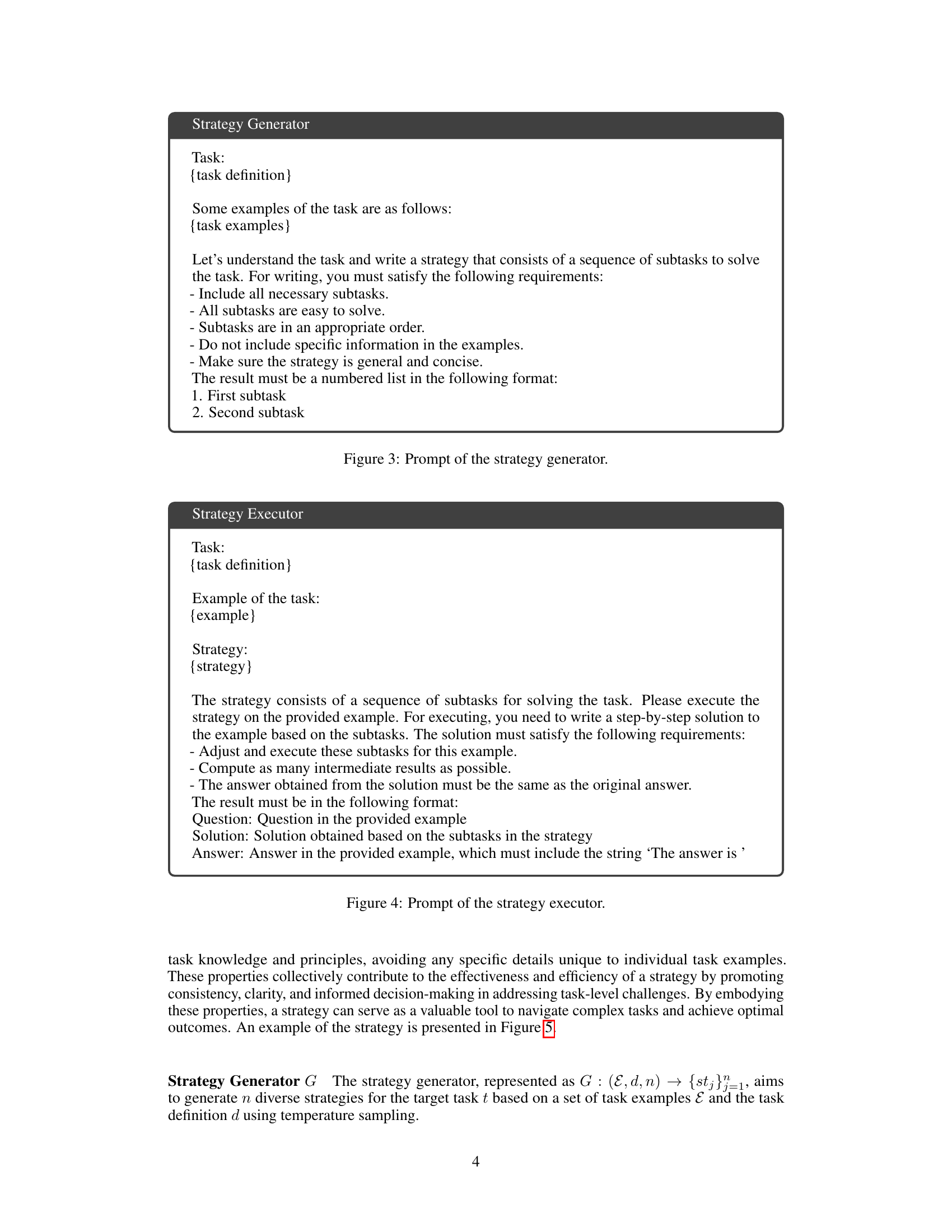

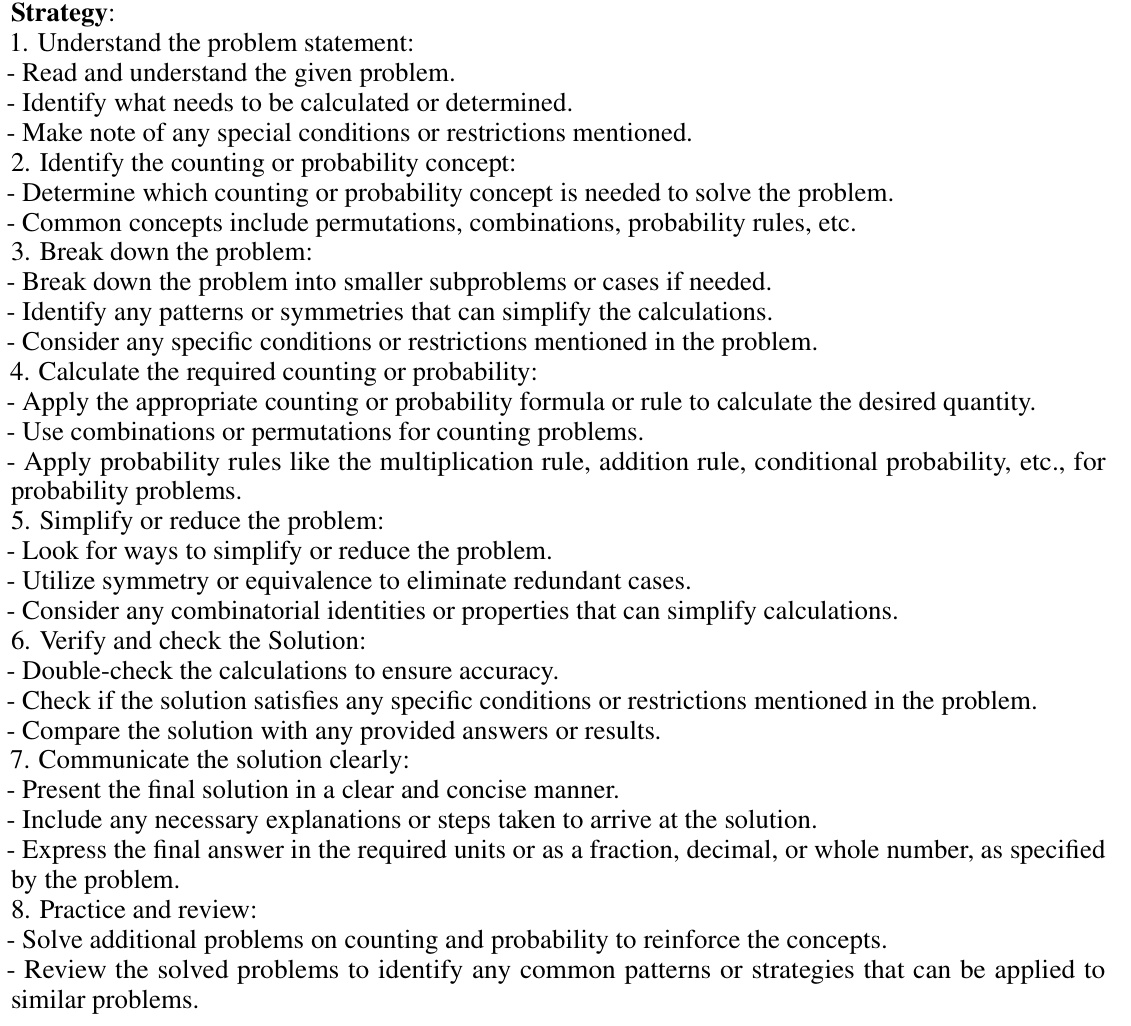

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It starts with a strategy generator creating a pool of strategies, which are then tested by a strategy executor. Qualified strategies (those meeting a performance threshold) are cached; unqualified strategies are optimized and retested. This iterative process continues until enough qualified strategies are found. Finally, a strategy evaluator ranks the strategies and evaluates the top performers using a validation set.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure presents a flowchart that illustrates the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It begins with a strategy generator creating a pool of strategies. These strategies are then tested by a strategy executor, and qualified strategies are cached. If there aren’t enough qualified strategies, the unqualified strategies are sent to a strategy optimizer to improve their performance. Then the strategies are ranked and evaluated by a strategy evaluator. This iterative process continues until enough qualified strategies are obtained or a maximum iteration limit is reached.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure presents a flowchart illustrating the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It starts with a strategy generator producing a pool of strategies. These strategies are then evaluated by an executor, with successful strategies cached. Unsuccessful strategies proceed to an optimizer, and then are reevaluated. This iterative process continues until a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or a maximum iteration count is reached. Finally, the top k strategies (based on accuracy) are used for the inference phase.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This bar chart compares the performance of two methods, CoT-SC and StrategyLLM-SC, across five difficulty levels of the MATH benchmark dataset. Each bar represents the average performance of each method at a given difficulty level. The chart shows that StrategyLLM-SC outperforms CoT-SC consistently across all difficulty levels, demonstrating StrategyLLM’s effectiveness on complex reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparison of CoT-SC and StrategyLLM-SC performance on the MATH benchmark across various difficulty levels.

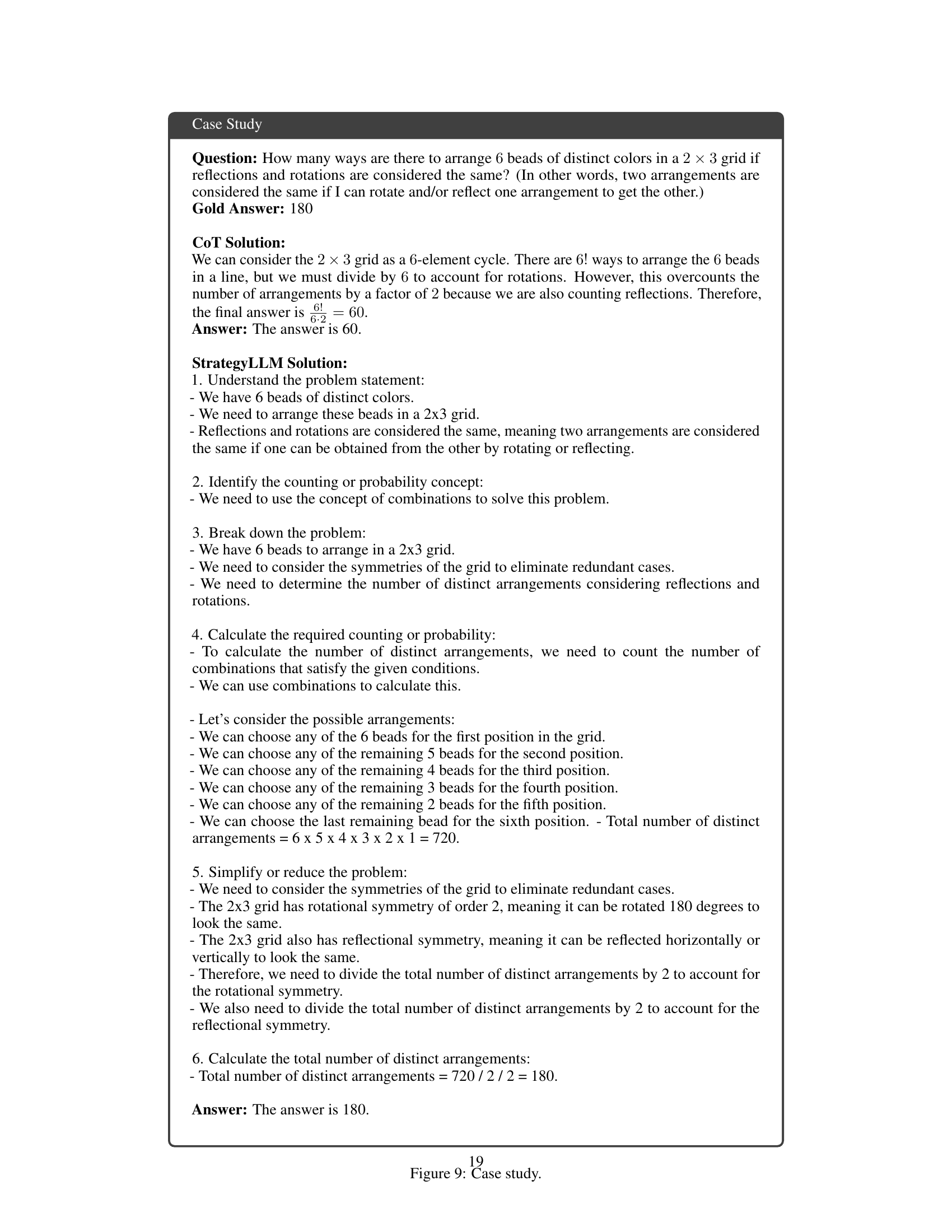

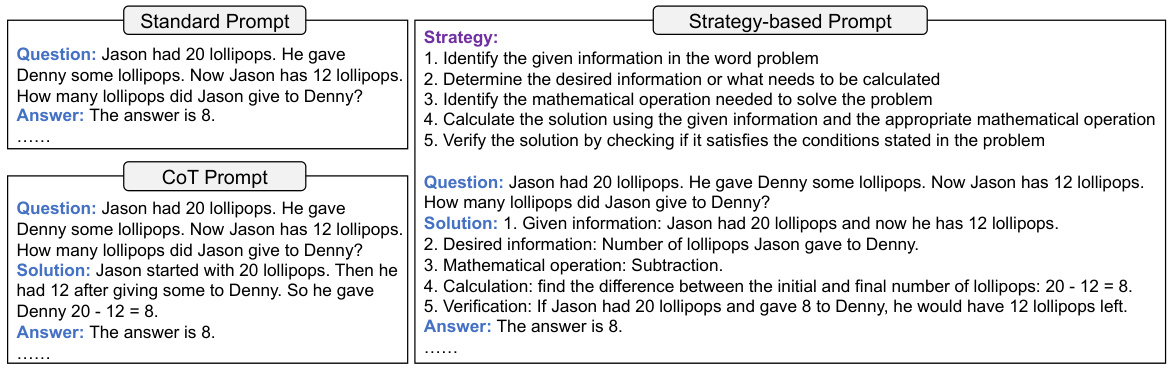

🔼 This figure displays the performance of both StrategyLLM-SC and CoT-SC across three different datasets (CP, StrategyQA, and MA) as the number of solutions used increases from 1 to 9. Each subplot shows the accuracy (percentage of correctly solved examples) for both methods across a range of solution counts. The purpose of the figure is to demonstrate the impact of using multiple solutions (strategies) on accuracy and how StrategyLLM consistently outperforms CoT-SC in all cases. The x-axis represents the number of solutions used, while the y-axis indicates the resulting accuracy. Note that StrategyLLM-SC consistently surpasses CoT-SC across all three datasets and solution counts.

read the caption

Figure 7: Performance of StrategyLLM-SC and CoT-SC on the CP, StrategyQA, and MA datasets.

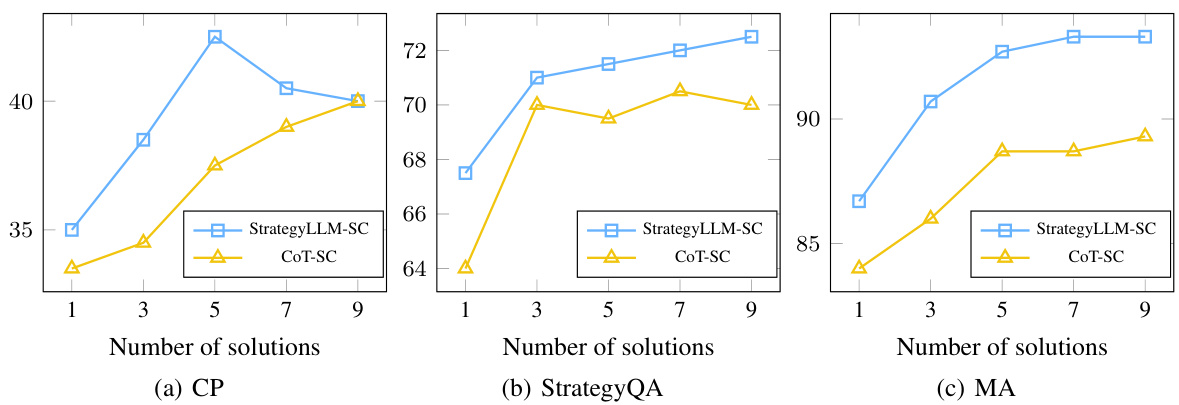

🔼 This figure displays the performance of StrategyLLM-SC and CoT-SC across three different datasets (CP, StrategyQA, and MA) when employing varying numbers of solutions (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9). Each sub-figure shows two lines: one for the coverage (the percentage of examples correctly solved by at least one strategy) and another for the accuracy (the overall accuracy achieved by selecting the majority vote from all solutions generated by multiple strategies). The figure visually demonstrates that using multiple strategies generally increases coverage but does not always lead to a significant improvement in accuracy, indicating there might be a limit to how much accuracy can be gained by simply combining more strategies.

read the caption

Figure 8: Coverage and accuracy of StrategyLLM using multiple strategies on the CP, StrategyQA, and MA datasets.

🔼 This figure presents a flowchart illustrating the StrategyLLM framework’s operation. The framework uses four agents: a strategy generator, an executor, an optimizer, and an evaluator. The generator creates strategies, which the executor tests on examples. Successful strategies are cached; unsuccessful ones are optimized and retested. Finally, top-performing strategies are chosen for inference.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It starts with a strategy generator creating a pool of strategies. These strategies are then tested by a strategy executor on example tasks and evaluated for accuracy. Strategies meeting a certain accuracy threshold are cached. Those that don’t meet the threshold are sent to a strategy optimizer for improvement, and the cycle repeats. Finally, the top performing strategies are selected and further evaluated using a validation set.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It starts with a strategy generator creating a pool of strategies. These are then tested by the strategy executor on examples; successful strategies (above a certain accuracy threshold) are cached. Unsuccessful strategies are sent to the strategy optimizer to be refined and retested. This cycle continues until enough successful strategies are obtained or a maximum number of iterations is reached. Finally, the top k strategies are ranked and evaluated on a validation set to determine the best strategies for use in generating the final prompt.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure presents a flowchart illustrating the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It begins with a strategy generator creating a pool of strategies. These are then executed by a strategy executor on task examples to assess accuracy. Strategies exceeding a defined threshold are cached; otherwise, they’re optimized and re-evaluated. This iterative process continues until enough qualified strategies are obtained or a set number of iterations are reached. Finally, the top-performing strategies are ranked and evaluated on a validation set.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure shows the workflow of the StrategyLLM framework. It starts with a strategy generator creating multiple strategies. The strategy executor then tests these strategies on sample problems, saving only those that meet a performance threshold. If not enough strategies are successful, the strategy optimizer refines the unsuccessful ones. This cycle repeats until enough strategies pass the performance test. Finally, the best-performing strategies are evaluated on a separate validation set, and the top performing ones are used for inference.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 This figure presents a flowchart of the StrategyLLM framework, illustrating the interaction between four LLM-based agents: strategy generator, executor, optimizer, and evaluator. The process begins with the strategy generator creating a pool of strategies. The executor then applies these strategies to examples and evaluates their accuracy. Qualified strategies are cached, while unqualified strategies are iteratively optimized and re-evaluated. The process continues until a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained, after which the top performing strategies are selected using a validation set.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of StrategyLLM. Initially, the strategy generator creates a pool of strategies, which are then applied by the strategy executor to task examples to calculate execution accuracy. Qualified strategies meeting a pre-defined threshold are cached, and if necessary, unqualified strategies are optimized and re-evaluated in iterative cycles. Once a sufficient number of qualified strategies are obtained or the maximum iteration number is reached, the top k strategies are ranked by execution accuracy and evaluated using a validation set.

🔼 The figure demonstrates two different approaches to solving a system of linear equations: using specific solutions and using a strategy-based solution. The left side shows two specific solutions, which are based on different approaches (substitution vs. equation subtraction) and may not generalize well to other instances. The right side shows a strategy-based solution (Gaussian Elimination Method), which provides a generalizable and consistent approach applicable to various systems of linear equations. This highlights the limitations of relying on instance-specific solutions for few-shot prompting and the advantages of incorporating generalizable strategies in few-shot prompts.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of specific solutions and strategy-based solutions.

🔼 The figure compares two approaches to solving a system of linear equations. The left side shows two example solutions using different methods (substitution and elimination), highlighting the lack of consistency and generalizability that can be problematic for LLMs. The right side demonstrates a consistent strategy-based approach (Gaussian Elimination Method) which provides a generalizable, step-by-step solution applicable across multiple instances of the problem. This helps illustrate the core idea of the paper – using a strategy-based approach to few-shot prompting instead of individual examples to improve LLM performance and consistency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of specific solutions and strategy-based solutions.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core difference between the StrategyLLM approach and traditional prompting methods. The left side shows how existing methods rely on instance-specific solutions (Solution 1 and Solution 2) that are not easily generalizable to new problems. Each solution uses a different problem-solving technique, hindering the LLM’s ability to consistently apply a method. The right side demonstrates the StrategyLLM approach, using a general strategy (Gaussian Elimination Method) that is applied consistently across various instances. This approach leverages inductive and deductive reasoning by the LLMs to create generalizable and consistent few-shot prompts, leading to improved performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of specific solutions and strategy-based solutions.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance of different methods on the MATH benchmark’s math reasoning tasks. It shows the average accuracy across seven sub-datasets (Algebra, Prealgebra, Intermediate Algebra, Counting and Probability, Number Theory, Geometry, and Precalculus) for various methods: Standard Prompting (SP), SolutionLLM, Chain-of-Thought (CoT), Self-Consistency with CoT (CoT-SC), and the proposed StrategyLLM (with three variants: StrategyLLM, StrategyLLM-SC, and StrategyLLM-ZS). The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage improvement of each StrategyLLM variant over the CoT-SC baseline.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results on the math reasoning task. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

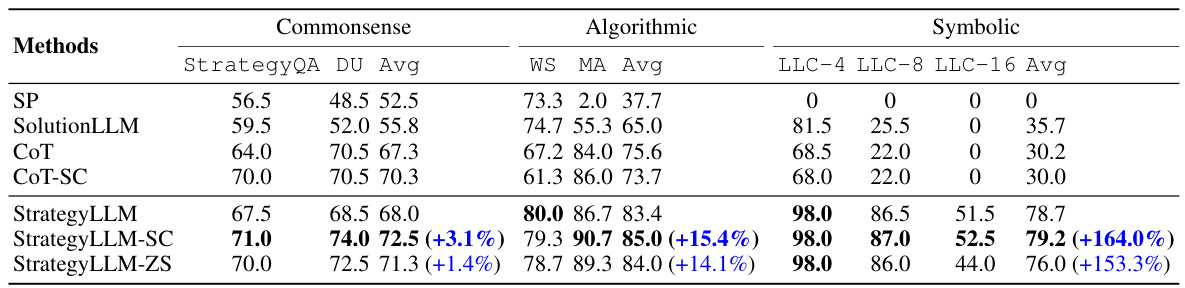

🔼 This table presents the performance of different methods on three reasoning tasks: commonsense, algorithmic, and symbolic. The methods compared include standard prompting (SP), SolutionLLM, chain-of-thought (CoT), self-consistent chain-of-thought (CoT-SC), and the proposed StrategyLLM (with three variants: StrategyLLM, StrategyLLM-SC, and StrategyLLM-ZS). For each task, the average performance across multiple datasets is shown, along with the percentage improvement of StrategyLLM compared to the CoT-SC baseline.

read the caption

Table 2: Experimental results on the commonsense, algorithmic, and symbolic reasoning tasks. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

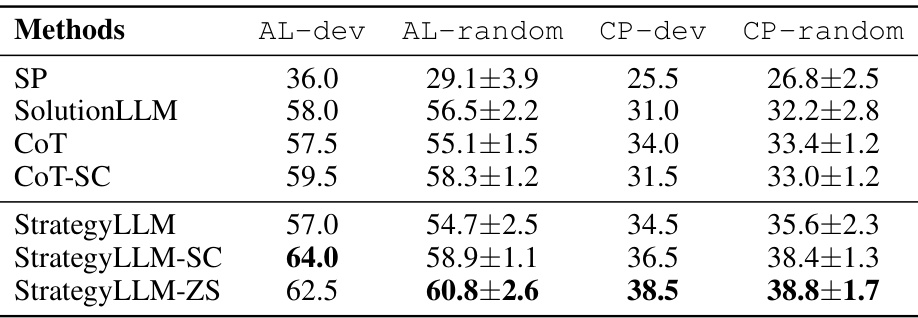

🔼 This table presents the experimental results obtained for two math reasoning datasets (AL and CP) using different groups of examples. The results are compared across several methods: Standard Prompting (SP), SolutionLLM, Chain-of-Thought (CoT), Self-Consistency with CoT (CoT-SC), StrategyLLM, StrategyLLM-SC, and StrategyLLM-ZS. The table shows the performance of each method on the AL-dev, AL-random, CP-dev, and CP-random datasets, providing insights into the robustness of each approach with respect to variations in the training examples used.

read the caption

Table 3: Experimental results on two math reasoning datasets, namely AL and CP, with different groups of examples.

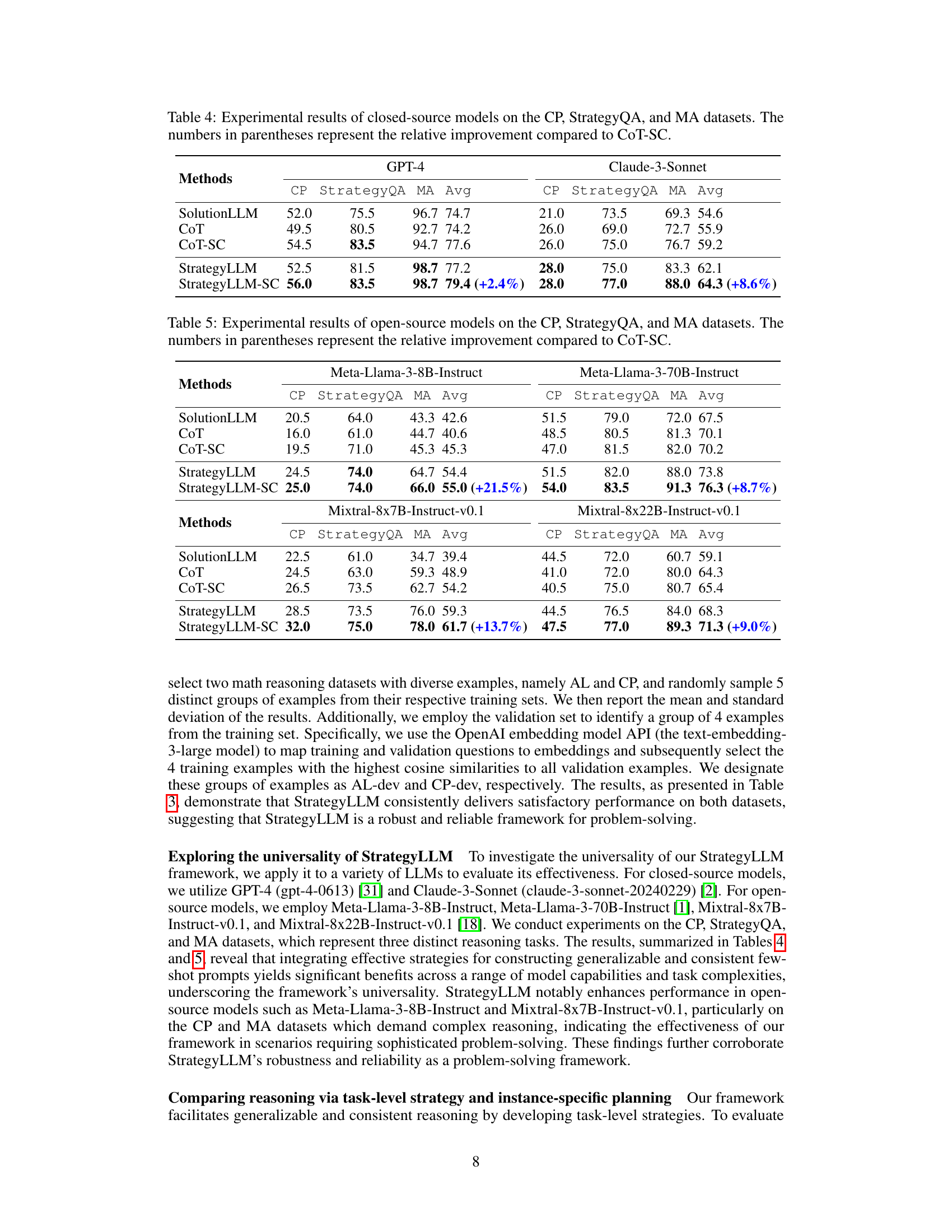

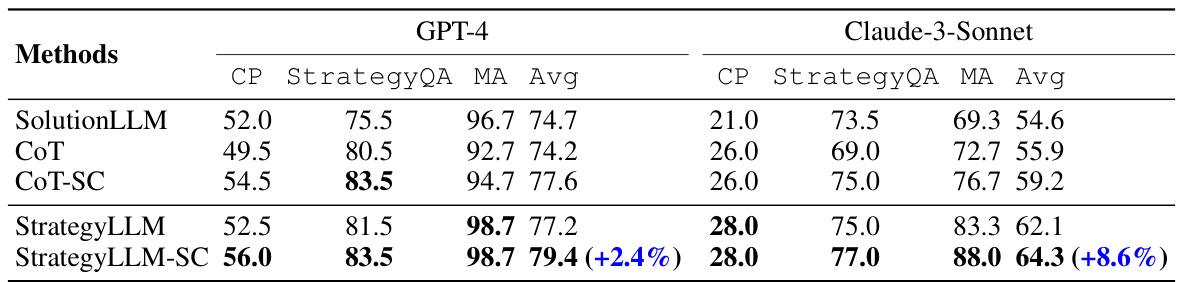

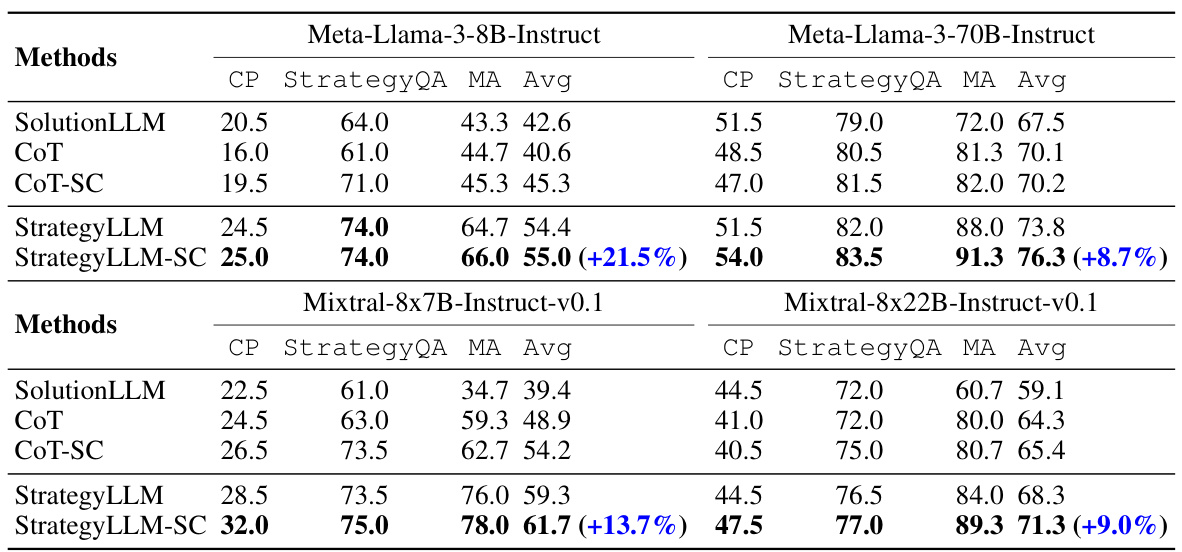

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (SolutionLLM, CoT, CoT-SC, StrategyLLM, StrategyLLM-SC) on three different datasets (CP, StrategyQA, MA) using two closed-source language models (GPT-4 and Claude-3-Sonnet). The results are presented as average scores across the datasets, with StrategyLLM-SC showing improvements over CoT-SC. The improvements are quantified in percentage points in parentheses.

read the caption

Table 4: Experimental results of closed-source models on the CP, StrategyQA, and MA datasets. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (SP, SolutionLLM, CoT, CoT-SC, StrategyLLM, StrategyLLM-SC, and StrategyLLM-ZS) across three reasoning tasks: commonsense reasoning, algorithmic reasoning, and symbolic reasoning. Each task uses different datasets and metrics to evaluate the accuracy of the models. The numbers in parentheses show the percentage improvement achieved by each method compared to the CoT-SC baseline.

read the caption

Table 2: Experimental results on the commonsense, algorithmic, and symbolic reasoning tasks. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different methods (Plan-and-Solve, CoT+Strategy, and StrategyLLM) across three datasets (CP, StrategyQA, and MA). Each method is evaluated with and without self-consistency (SC), which involves generating multiple solutions and taking a majority vote. The average performance across the three datasets is shown for each method.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of Plan-and-Solve, CoT+Strategy, and StrategyLLM.

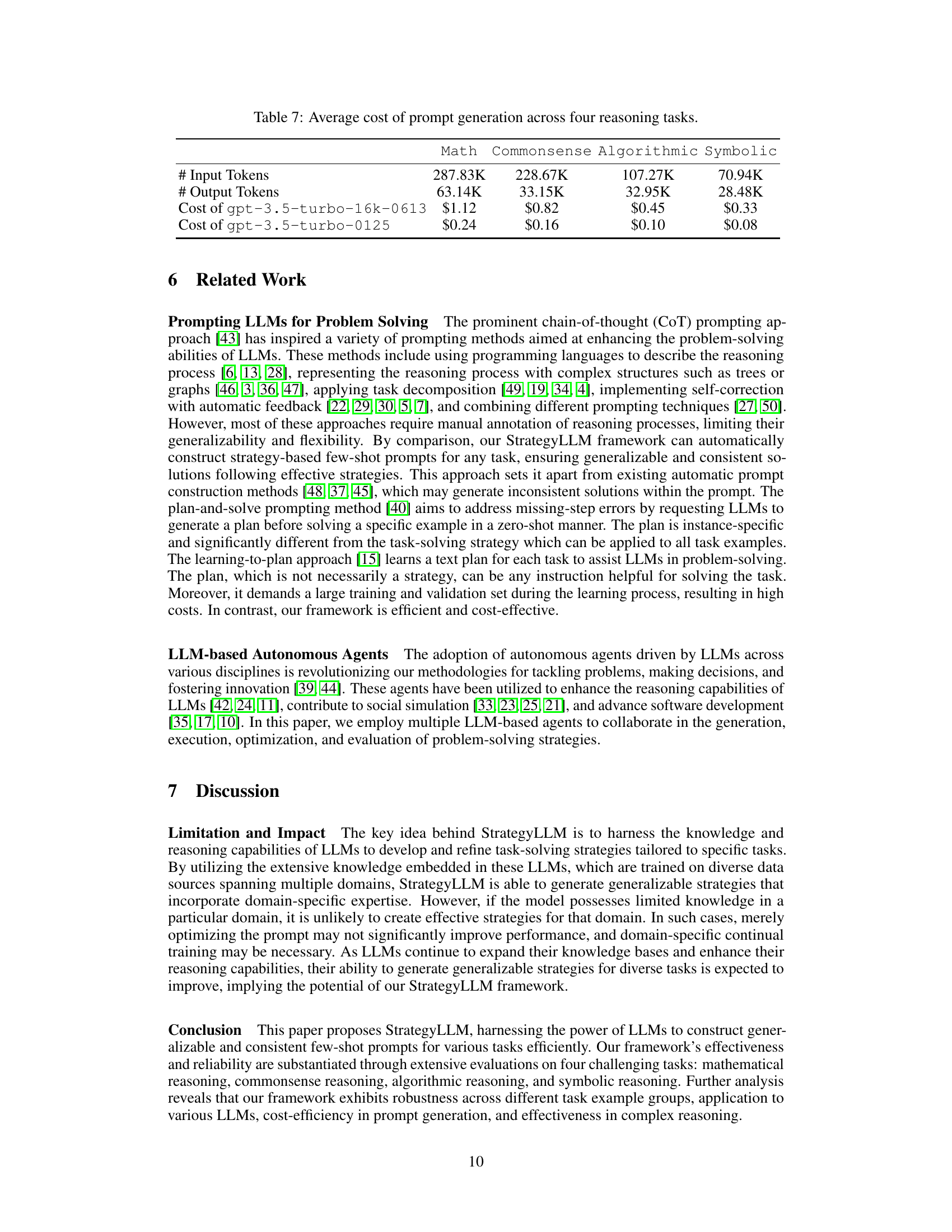

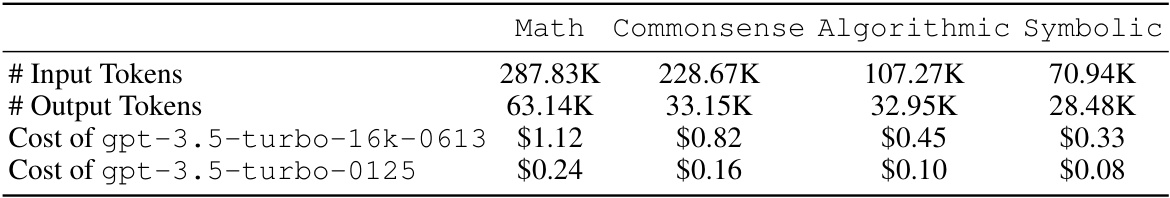

🔼 This table presents the average cost of generating prompts for four reasoning tasks (Math, Commonsense, Algorithmic, and Symbolic) using two different versions of GPT-3.5-turbo. The costs are broken down into input tokens, output tokens, and the monetary cost using each GPT model version. It highlights the cost-effectiveness of the StrategyLLM framework across various tasks.

read the caption

Table 7: Average cost of prompt generation across four reasoning tasks.

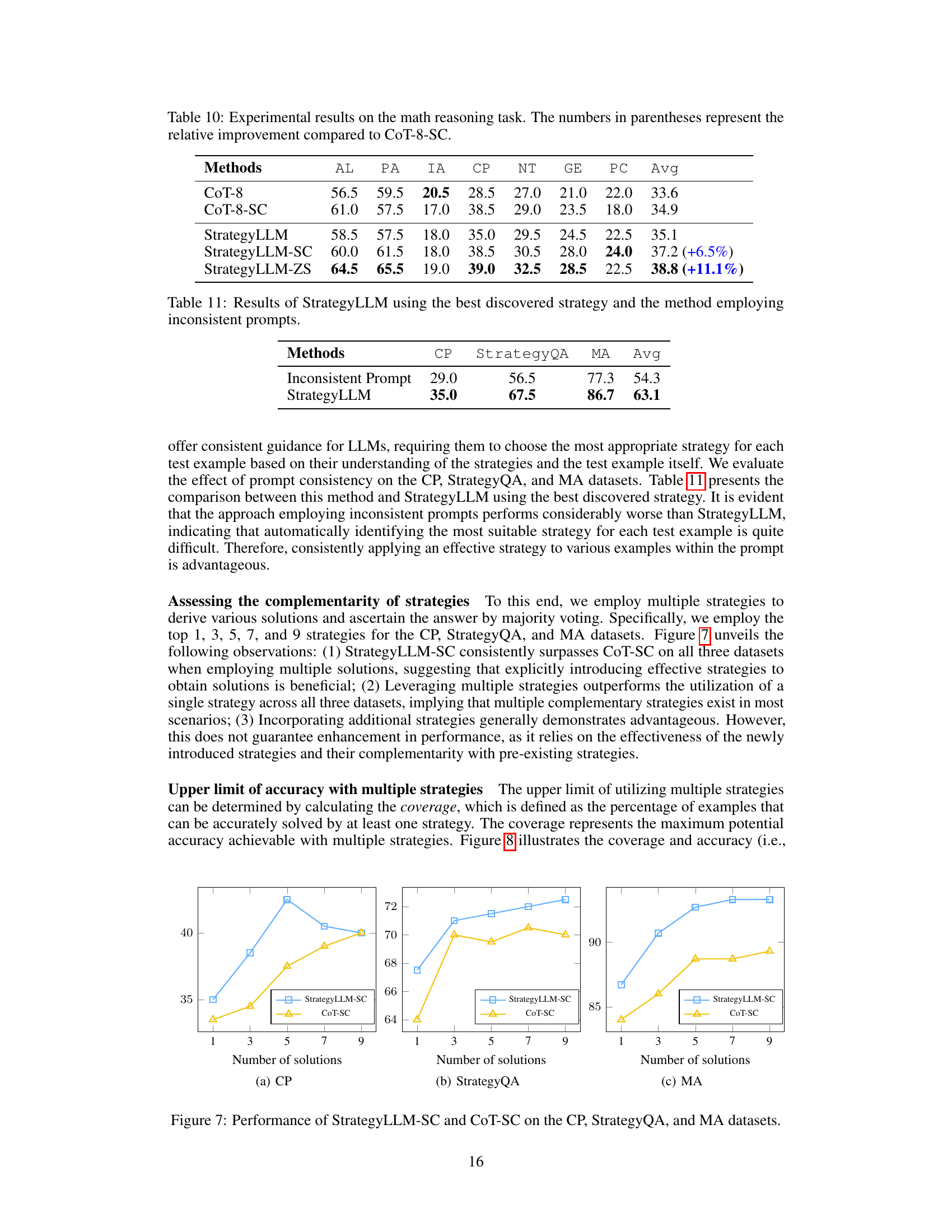

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on the MATH reasoning benchmark. It shows the average accuracy achieved by each method across seven sub-datasets (Algebra, Prealgebra, Intermediate Algebra, Counting and Probability, Number Theory, Geometry, and Precalculus) within the MATH benchmark. The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage improvement of each method compared to the baseline method, CoT-SC.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results on the math reasoning task. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

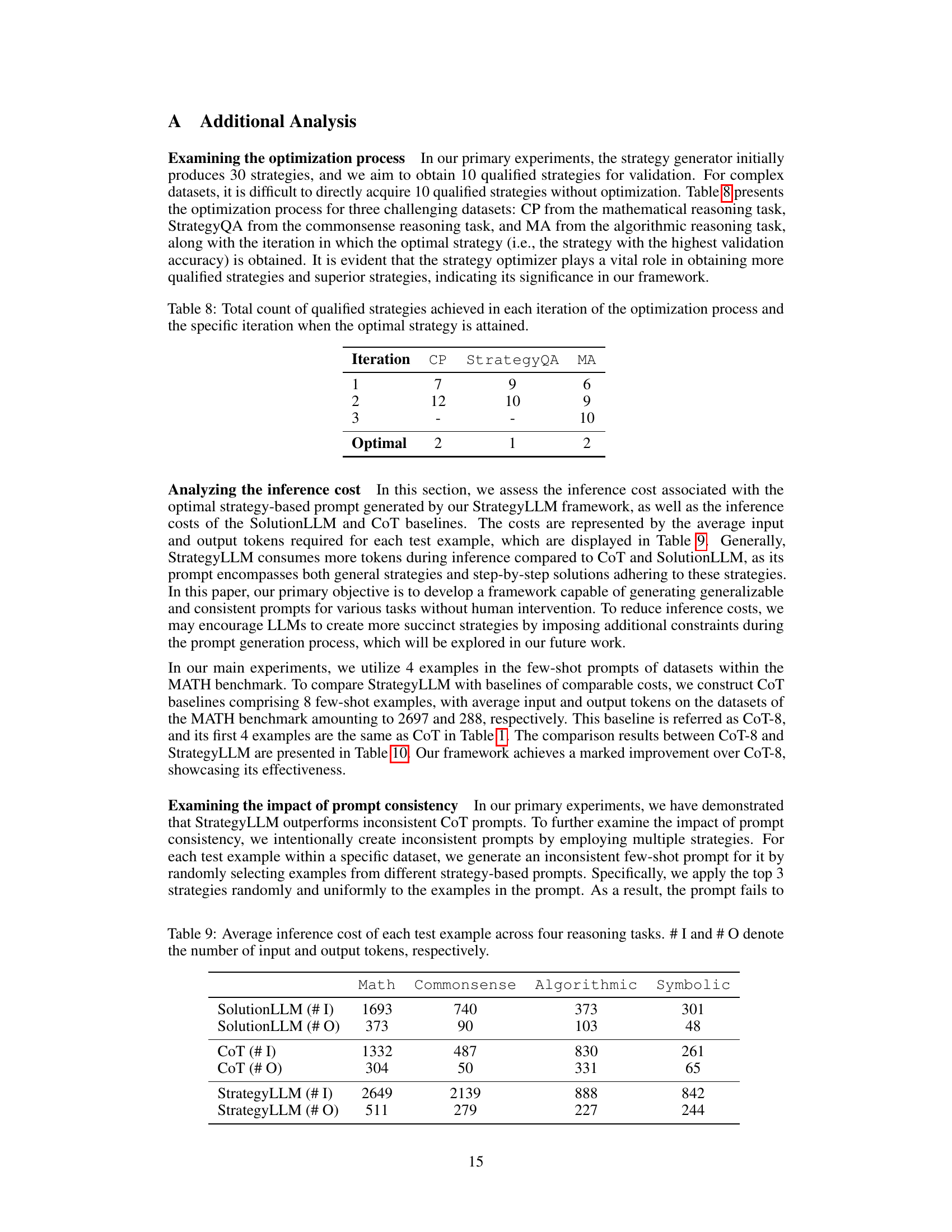

🔼 This table shows the average number of input and output tokens consumed during inference for each reasoning task. It compares the token usage for the SolutionLLM, CoT (Chain of Thought), and StrategyLLM methods, providing insight into the efficiency and resource requirements of each approach. The ‘# I’ column represents the average number of input tokens, while ‘# O’ represents the average number of output tokens. The four reasoning tasks are Math, Commonsense, Algorithmic, and Symbolic.

read the caption

Table 9: Average inference cost of each test example across four reasoning tasks. # I and # O denote the number of input and output tokens, respectively.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different methods on the math reasoning task from the MATH benchmark. It shows the average accuracy for each method across seven sub-datasets of varying difficulty (Algebra, Prealgebra, Intermediate Algebra, Counting and Probability, Number Theory, Geometry, and Precalculus). The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage improvement achieved by each method compared to the CoT-SC baseline. The methods compared include standard prompting (SP), SolutionLLM, chain-of-thought prompting (CoT), self-consistent chain-of-thought (CoT-SC), and the proposed StrategyLLM with its self-consistent (StrategyLLM-SC) and zero-shot (StrategyLLM-ZS) variants.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental results on the math reasoning task. The numbers in parentheses represent the relative improvement compared to CoT-SC.

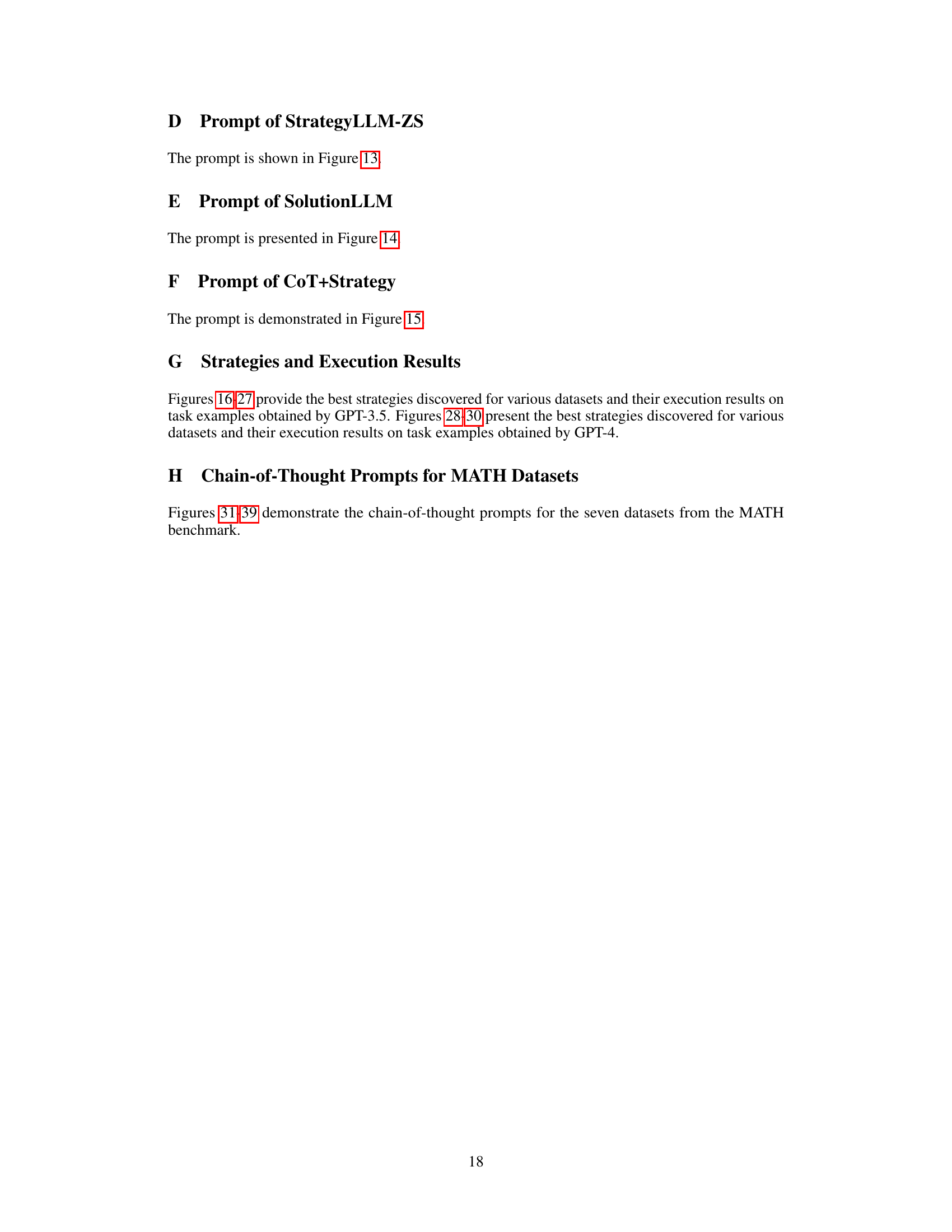

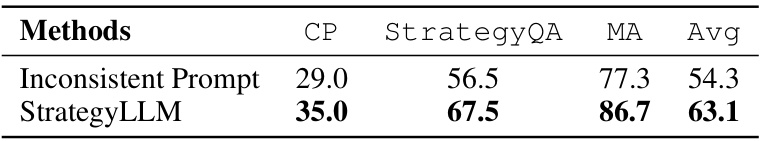

🔼 This table compares the performance of StrategyLLM using its best-performing strategy against a method using inconsistent prompts. The inconsistent prompt method randomly selects examples from different strategy-based prompts, demonstrating the negative impact of inconsistency on the model’s performance. The table shows the average accuracy of both methods across three different datasets: CP, StrategyQA, and MA, representing mathematical, commonsense, and algorithmic reasoning, respectively. The results clearly demonstrate the superior performance of StrategyLLM with consistent prompts.

read the caption

Table 11: Results of StrategyLLM using the best discovered strategy and the method employing inconsistent prompts.

Full paper#