↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Causal bandits leverage causal knowledge to accelerate optimal decision-making. However, existing methods often assume the causal graph is fully known, which is unrealistic for many real-world scenarios. This paper tackles this critical limitation by focusing on causal bandits where the causal graph, potentially containing latent confounders, is unknown. This poses a significant challenge, as optimal interventions may not be limited to the reward node’s parents and the search space for optimal actions grows exponentially with the number of nodes.

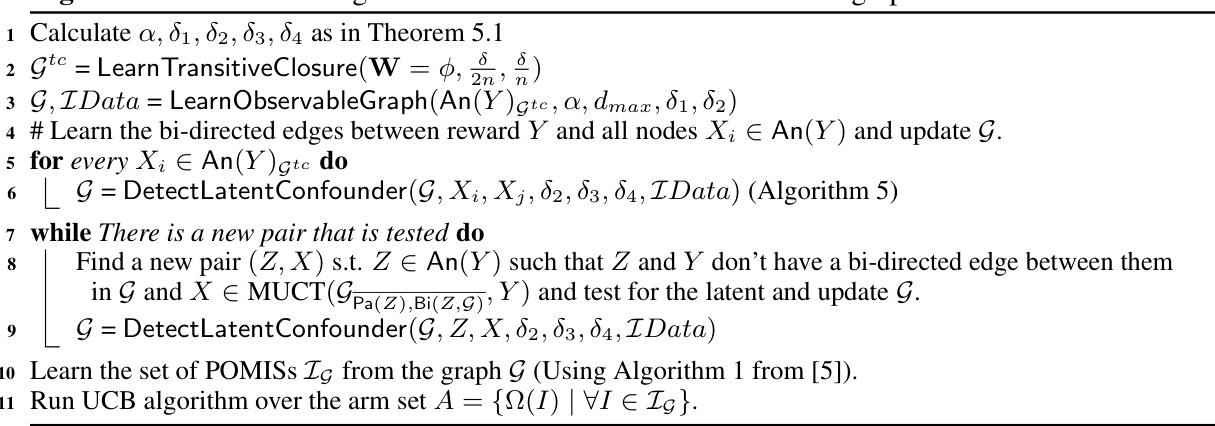

The researchers address this challenge by proposing a two-stage approach. First, they introduce a novel algorithm to learn a crucial part of the causal graph. This is crucial because only this subset of the graph is sufficient to identify the set of potentially optimal interventions (POMIS). Their method is proven to be sample-efficient, requiring only a polynomial number of samples. In the second stage, they apply a standard bandit algorithm, like UCB, to these identified POMIS to obtain an optimal policy. This innovative two-stage approach achieves sublinear regret, offering a practical solution to learning with unknown causal structures and latent confounders.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on causal bandits and causal discovery. It directly addresses the challenge of unknown causal structures in real-world applications, offering a novel, sample-efficient approach to learning optimal interventions. This significantly advances the field by providing both theoretical guarantees and practical algorithms, paving the way for more robust and effective causal inference in various applications.

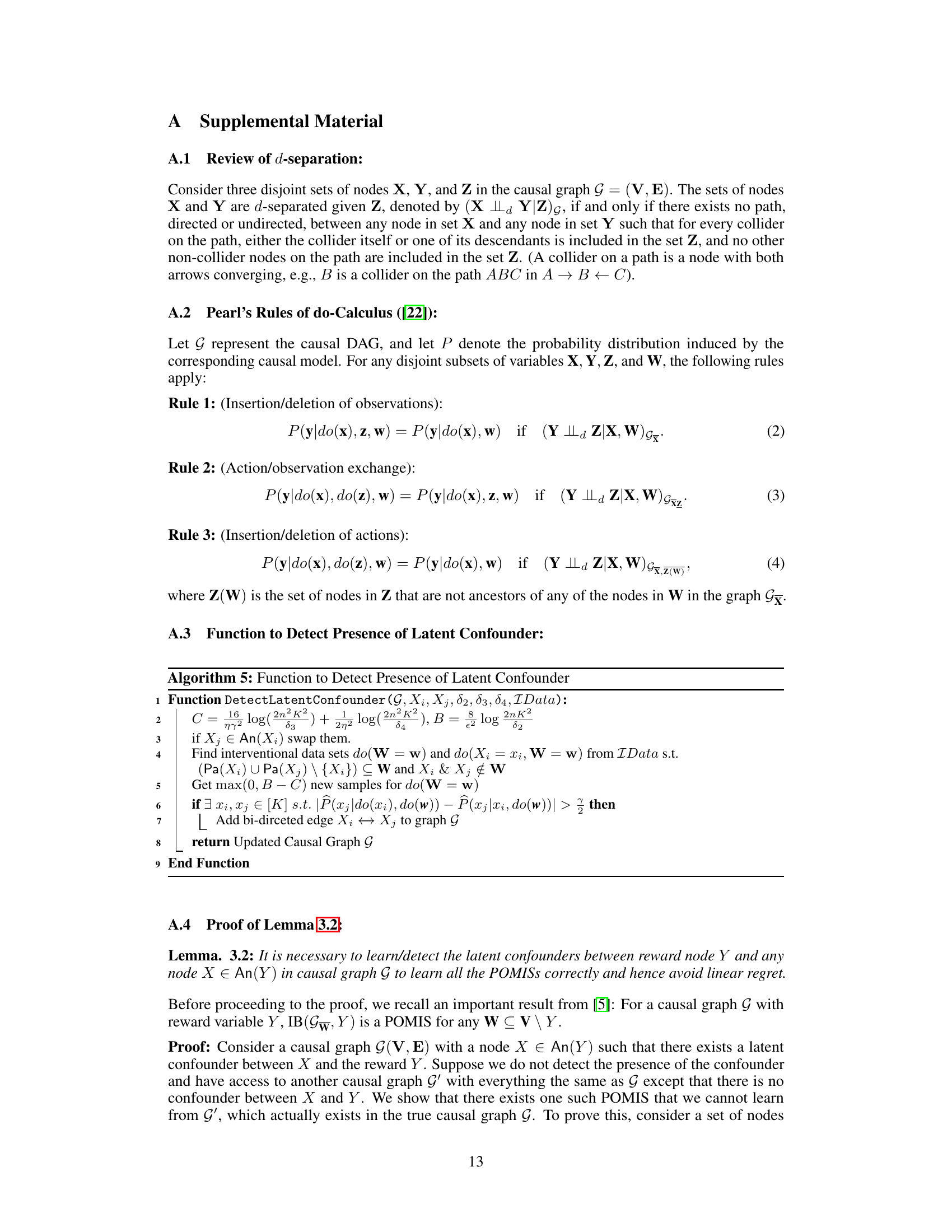

Visual Insights#

This figure presents five causal graphs. Graph G is considered the true graph, and the other four graphs (G1, G2, G3, G4) each have one missing bi-directed edge compared to G. This is used to illustrate that learning the full causal structure isn’t necessary for identifying all possibly optimal arms (POMISs) in a causal bandit setting. While missing some bi-directed edges (like in G1 and G2) leads to incorrect identification of POMISs, others (G3) might not affect the resulting POMISs. This highlights the paper’s core argument of only needing to learn a sufficient subset of the causal graph for effective regret minimization.

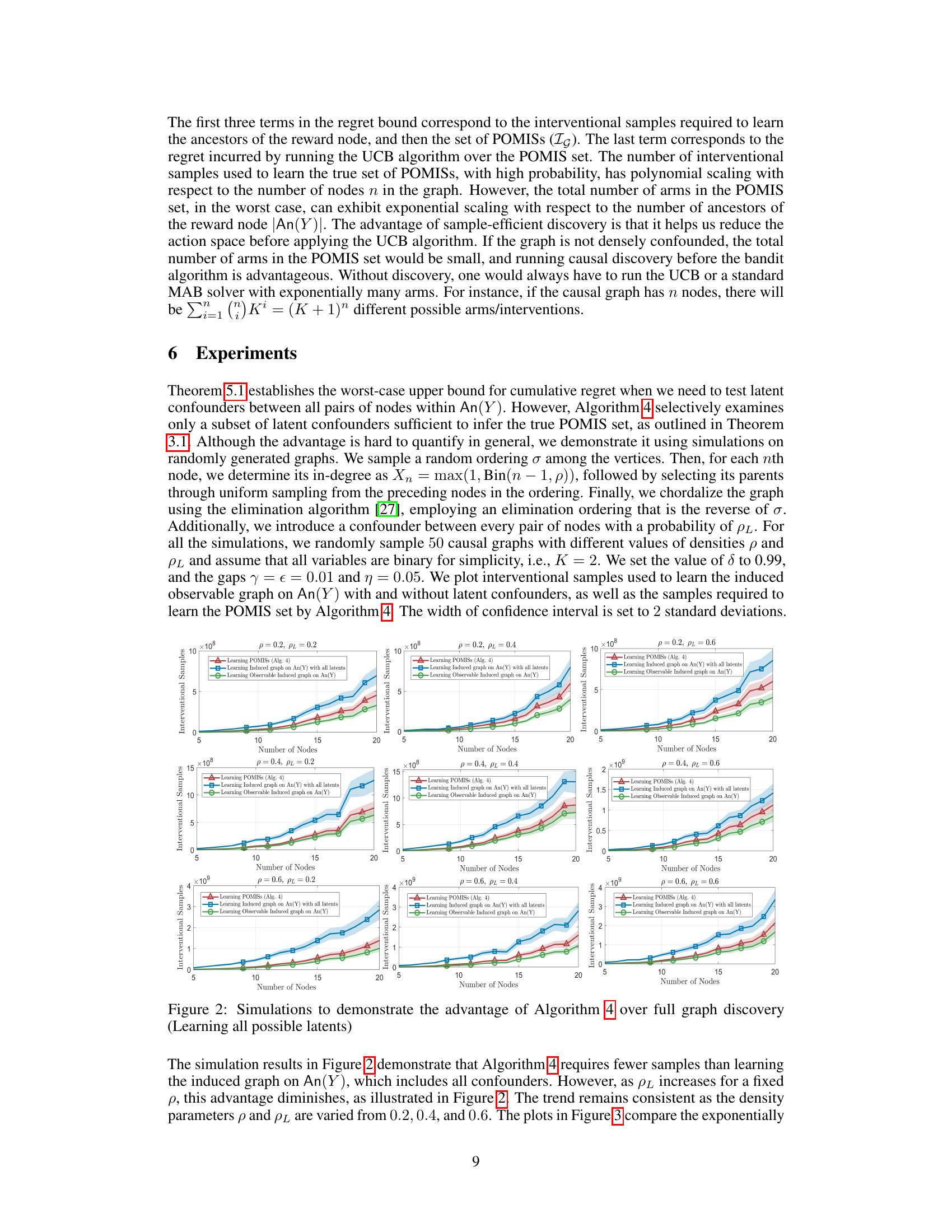

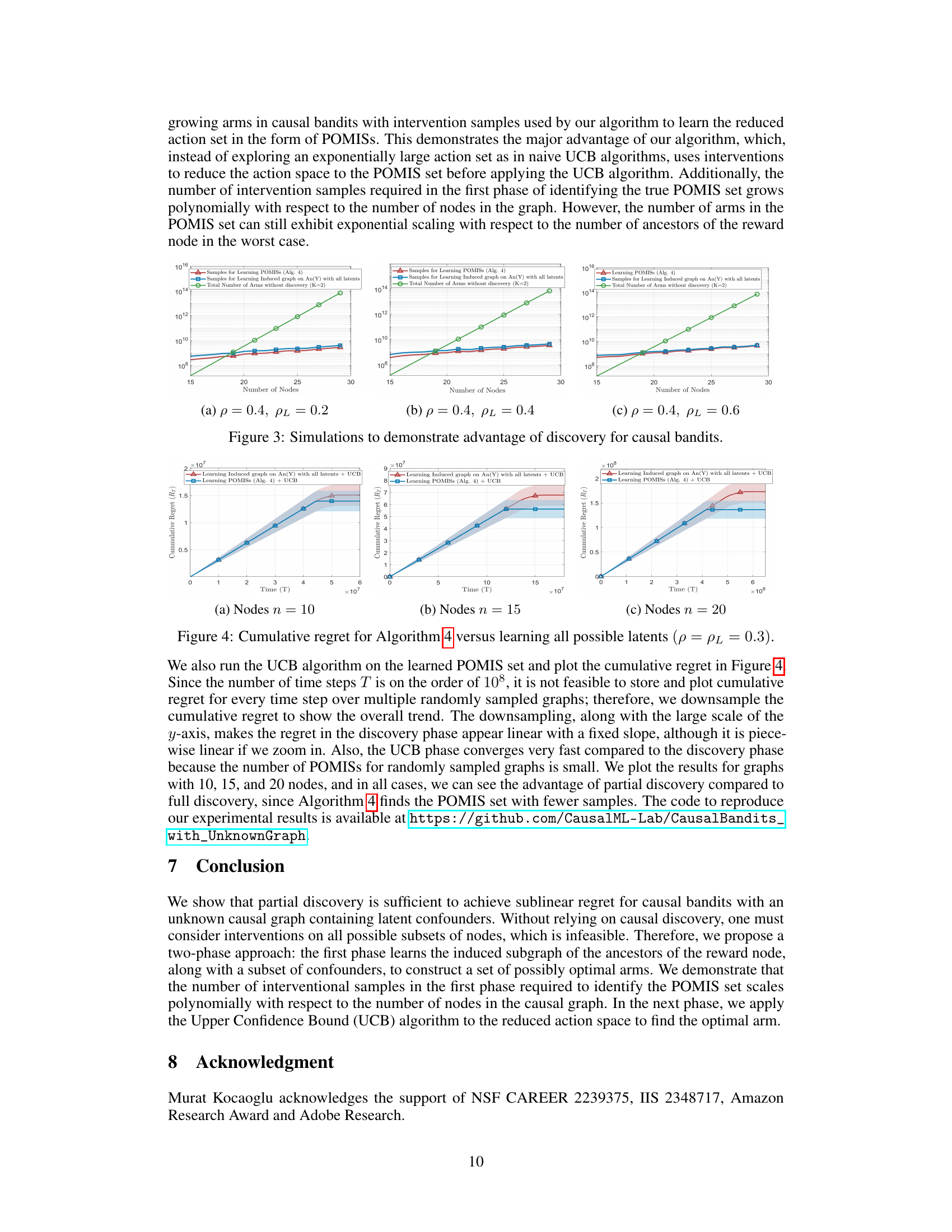

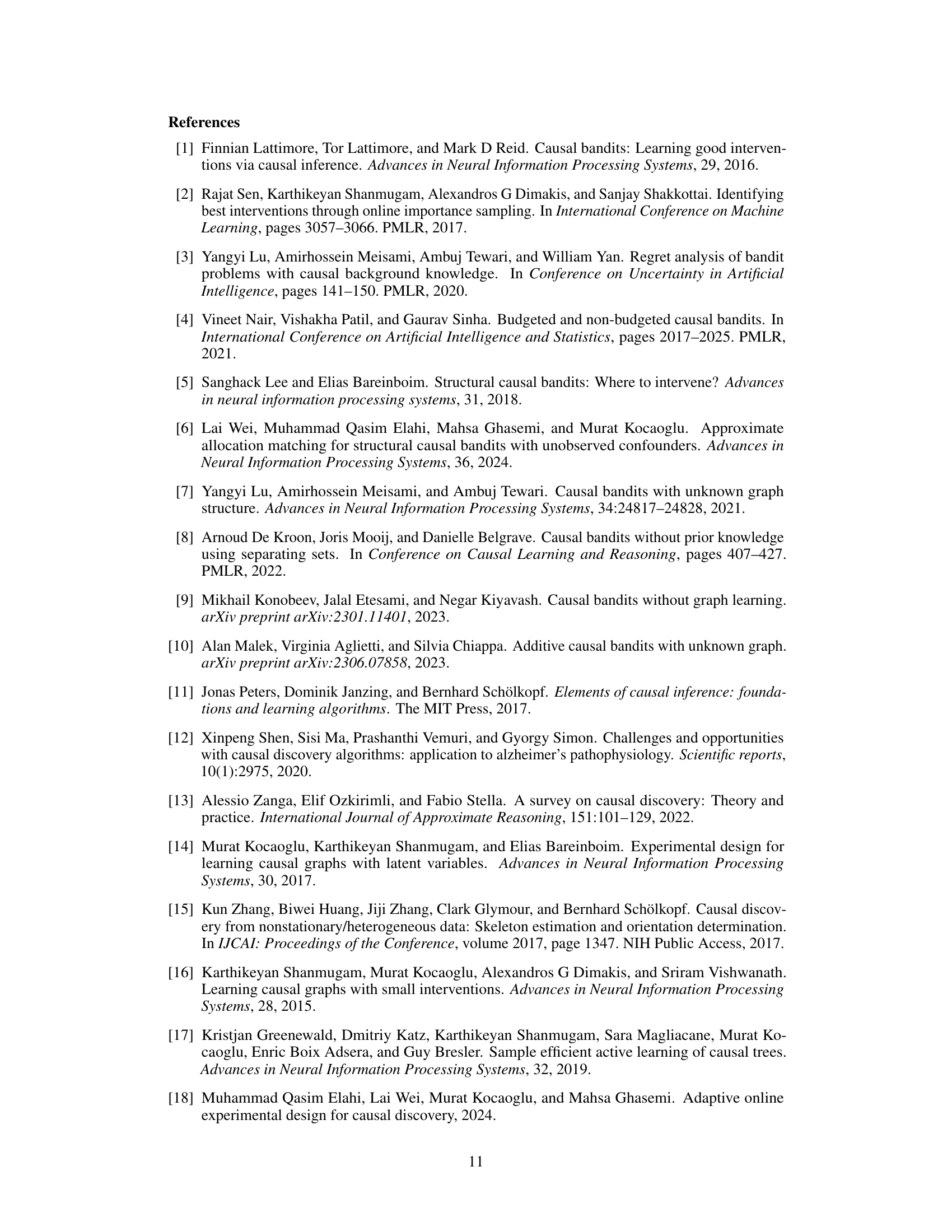

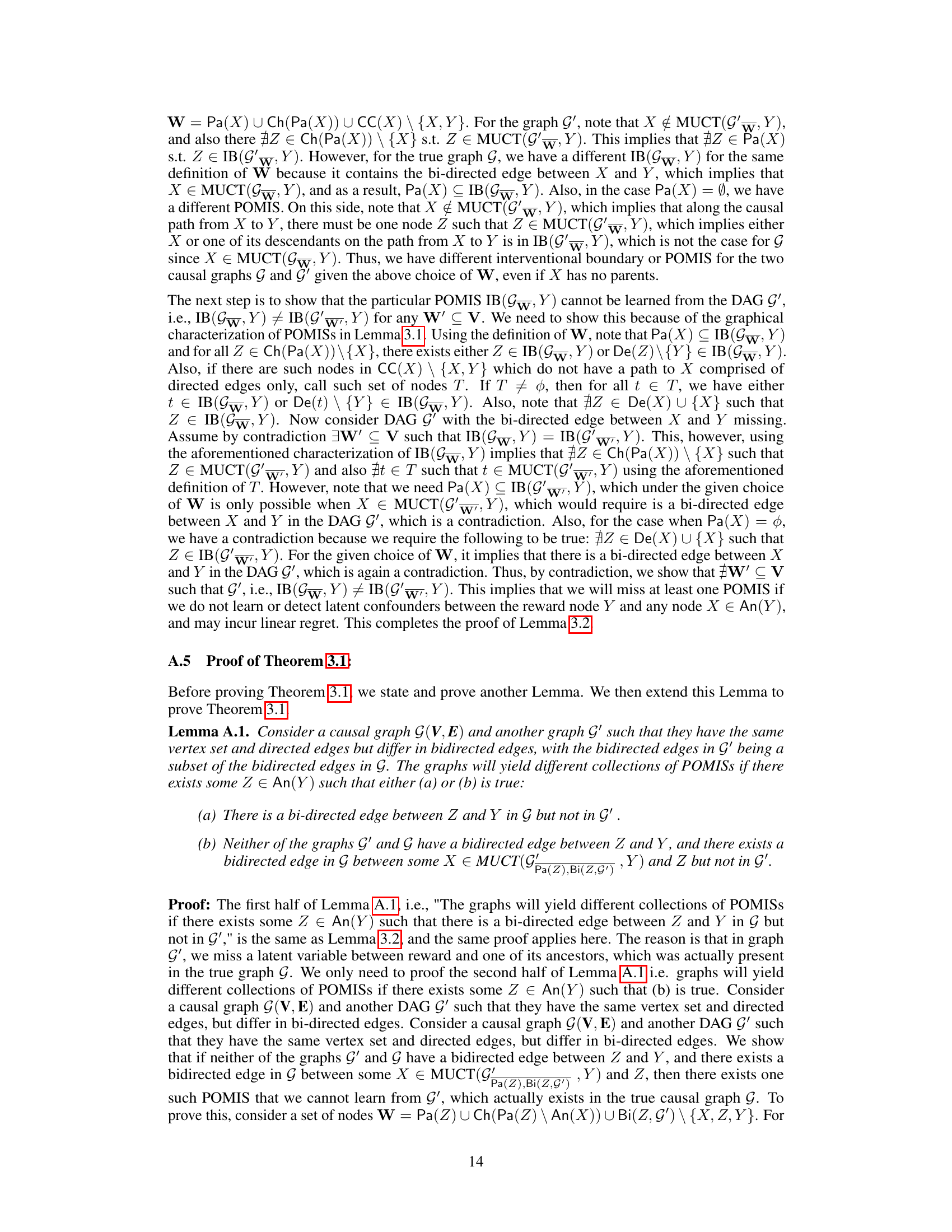

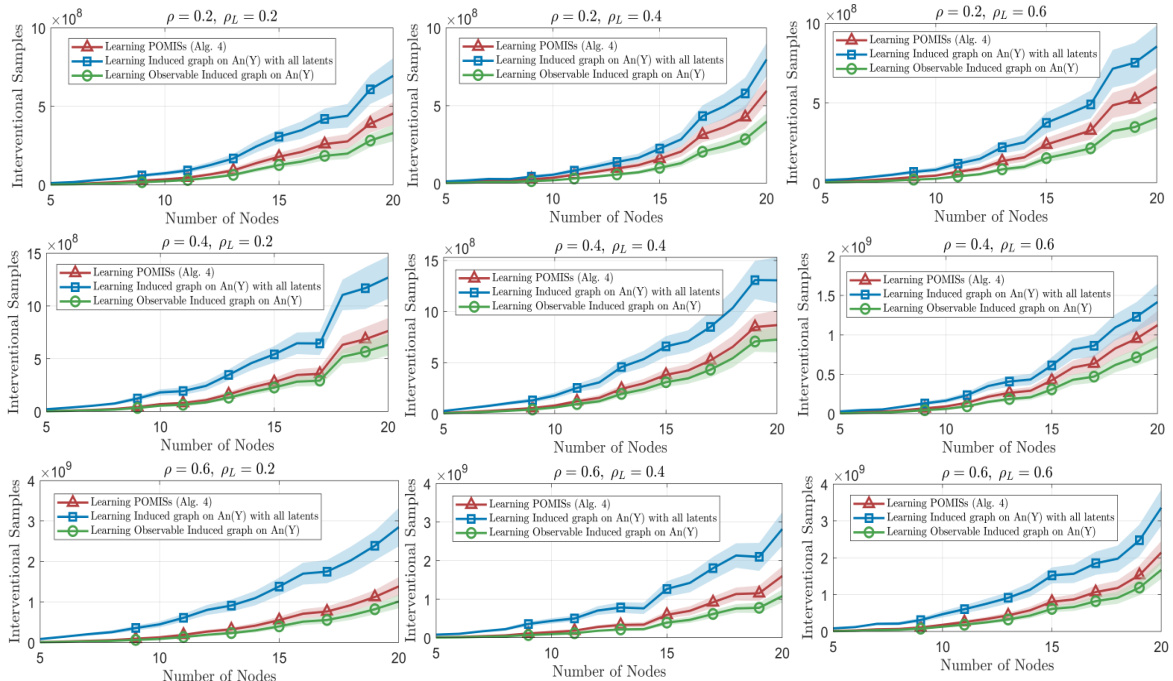

This figure compares the number of interventional samples required by Algorithm 4 (proposed algorithm) and a full graph discovery approach for learning the induced graph on the reward node’s ancestors and learning the Possibly Optimal Minimum Intervention Sets (POMISs). Different graph densities (p) and latent confounder probabilities (pL) are considered. The plots show that Algorithm 4 generally requires fewer samples, especially when the probability of latent confounders is low, highlighting the efficiency of the proposed two-stage approach.

In-depth insights#

Causal Bandit Setup#

In a causal bandit setup, the goal is to learn an optimal intervention strategy in an environment where actions influence outcomes through causal relationships. Unlike traditional bandits which assume a purely correlational relationship between actions and rewards, causal bandits incorporate knowledge or assumptions about the underlying causal structure. This causal knowledge can significantly improve learning efficiency by guiding the exploration-exploitation trade-off. A key challenge lies in the fact that the causal graph may be unknown or partially known, adding complexity to the learning process. Discovering the causal graph or relevant parts is often a critical first step, before applying standard bandit algorithms. Confounders, or latent variables affecting both actions and rewards, pose further difficulties. Addressing these confounders requires careful design of interventions and data collection strategies. The presence of confounders means the optimal intervention may not simply be on the direct parents of the reward variable, but might involve interventions on other ancestors, demanding more sophisticated causal discovery techniques. Therefore, a crucial aspect is identifying and characterizing the set of possibly optimal interventions and devising algorithms with theoretical guarantees to learn them efficiently in scenarios where the full causal structure is unknown.

Partial Structure#

The concept of ‘Partial Structure’ in the context of causal bandits signifies a significant departure from traditional methods that necessitate complete causal graph knowledge. Instead of learning the full causal structure, which is often computationally expensive and data-intensive, this approach focuses on identifying only the essential components required for effective decision-making. This involves characterizing the necessary and sufficient latent confounders and subgraphs, leading to substantial computational and sample efficiency gains. The core idea is that while complete causal knowledge may be ideal, it’s not always necessary; a carefully selected partial structure suffices for optimal or near-optimal regret minimization. This partial structure discovery approach offers a practical and scalable solution for real-world scenarios where full causal graph information is unavailable or difficult to obtain, thereby significantly advancing the applicability of causal bandits in complex systems. The theoretical contributions provide a formal characterization of this partial structure, ensuring correctness and providing theoretical guarantees for sample complexity and regret bounds.

Sample Efficiency#

The concept of sample efficiency is central to the research paper, focusing on minimizing the amount of data required to achieve accurate causal graph learning and effective decision-making in causal bandit settings. The authors tackle the challenge of unknown causal graphs, which necessitates a sample-efficient approach to discover the necessary structure. Their proposed algorithm cleverly identifies and learns only the necessary and sufficient components of the causal graph, avoiding unnecessary exploration of the full structure. This targeted learning strategy is crucial to overcome the exponential complexity often associated with causal discovery, particularly in the presence of latent confounders. By focusing on learning only a subgraph and relevant latent confounders, they demonstrate polynomial scaling of intervention samples, as opposed to the potentially exponential complexity. This sample efficiency translates into reduced regret and improved performance in the causal bandit problem, making the proposed method both practically feasible and theoretically sound.

Regret Minimization#

Regret minimization is a central theme in online learning, aiming to minimize the difference between an algorithm’s cumulative reward and that of an optimal strategy. In the context of causal bandits, where the goal is to learn optimal interventions, regret minimization becomes particularly challenging because the causal structure, often unknown, significantly impacts the effectiveness of different strategies. The paper explores how partial knowledge of the causal graph—rather than complete causal discovery—suffices to ensure no-regret learning. This is crucial for efficiency, as full causal structure learning is computationally expensive, often requiring extensive interventional data. By focusing on identifying a specific set of possibly optimal interventions (POMISs), the algorithm prioritizes learning only the necessary causal components, reducing sample complexity. The two-stage approach demonstrates a polynomial scaling in sample complexity with the number of nodes, followed by a standard bandit algorithm to select from the identified POMISs. The resulting regret bound underscores the efficiency of the partial causal discovery method in achieving sublinear regret.

Future Work#

The research paper’s ‘Future Work’ section would ideally explore extending the proposed two-stage causal bandit algorithm to handle more complex scenarios. Addressing scenarios with non-binary rewards or continuous decision variables would significantly broaden the algorithm’s applicability. Investigating alternative causal discovery algorithms to replace the randomized approach might improve sample efficiency and robustness. A thorough comparative analysis against existing causal bandit methods under various graph structures and data characteristics is crucial to establish the practical advantages of the proposed method. Furthermore, research could focus on developing tighter regret bounds to better understand its theoretical performance. Finally, exploring applications in real-world domains, such as personalized medicine or online advertising, would demonstrate the algorithm’s practical value and uncover potential challenges or limitations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows five causal graphs. The first graph (a) is the true causal graph G. The other four graphs (b-e) each have one missing bi-directed edge compared to the true graph. This is used to illustrate that not all latent confounders need to be identified for learning possibly optimal arms in causal bandits. Missing some bi-directed edges may not affect the set of possibly optimal arms, while missing others will.

This figure compares the number of interventional samples required by Algorithm 4 (learning POMISs) and the full graph learning approach (learning all latents) for learning the induced subgraph on the ancestors of the reward node Y. The results are shown for different graph densities (p) and confounder probabilities (pL), and the number of nodes (n) in the graph are varied from 5 to 20. The plots show that Algorithm 4 generally requires fewer samples than the full graph learning approach, demonstrating its sample efficiency. The difference becomes less pronounced as the probability of confounders increases.

The figure shows the number of interventional samples required for learning the possibly optimal minimum intervention sets (POMISs) using Algorithm 4, compared to learning the induced subgraph on the ancestors of the reward node with all latent confounders. The plots demonstrate that Algorithm 4 requires fewer samples, especially when the probability of confounders (PL) is lower. As PL increases, the advantage diminishes, but Algorithm 4 still generally outperforms full graph discovery. This highlights the efficiency of Algorithm 4 in reducing the sample complexity needed to learn the sufficient subgraph for regret minimization in causal bandits.

This figure compares the number of interventional samples required by Algorithm 4 (which learns a subset of confounders) and a full graph learning approach (which learns all confounders) for learning the induced subgraph on the ancestors of the reward node and the POMIS set. The results are shown for various graph densities (p) and latent confounder probabilities (PL). The figure demonstrates that Algorithm 4 requires significantly fewer samples compared to the full graph learning method, especially when the probability of latent confounders is low. This advantage diminishes as the latent confounder probability increases.

Full paper#