↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Complex visual reasoning and question answering (VQA) is a challenging field. Current methods struggle with multi-step reasoning and handling of both sequential and independent operations. This limitation hinders effective solutions for complex scenarios requiring compositional and higher-level reasoning capabilities.

This paper introduces a novel fully-neural Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) which effectively combines both iterative (step-by-step) and parallel computation. IPRM significantly improves accuracy in several VQA benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling diverse and complex scenarios. The model’s computations are also visualized, enhancing interpretability and facilitating error analysis. This design makes IPRM easily adaptable to various vision-language architectures.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in visual question answering (VQA) due to its novel Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). IPRM significantly improves performance on complex VQA tasks by combining iterative and parallel computation, addressing limitations of existing methods. It also offers enhanced interpretability through visualization of internal computations, paving the way for future improvements and new research in complex reasoning mechanisms.

Visual Insights#

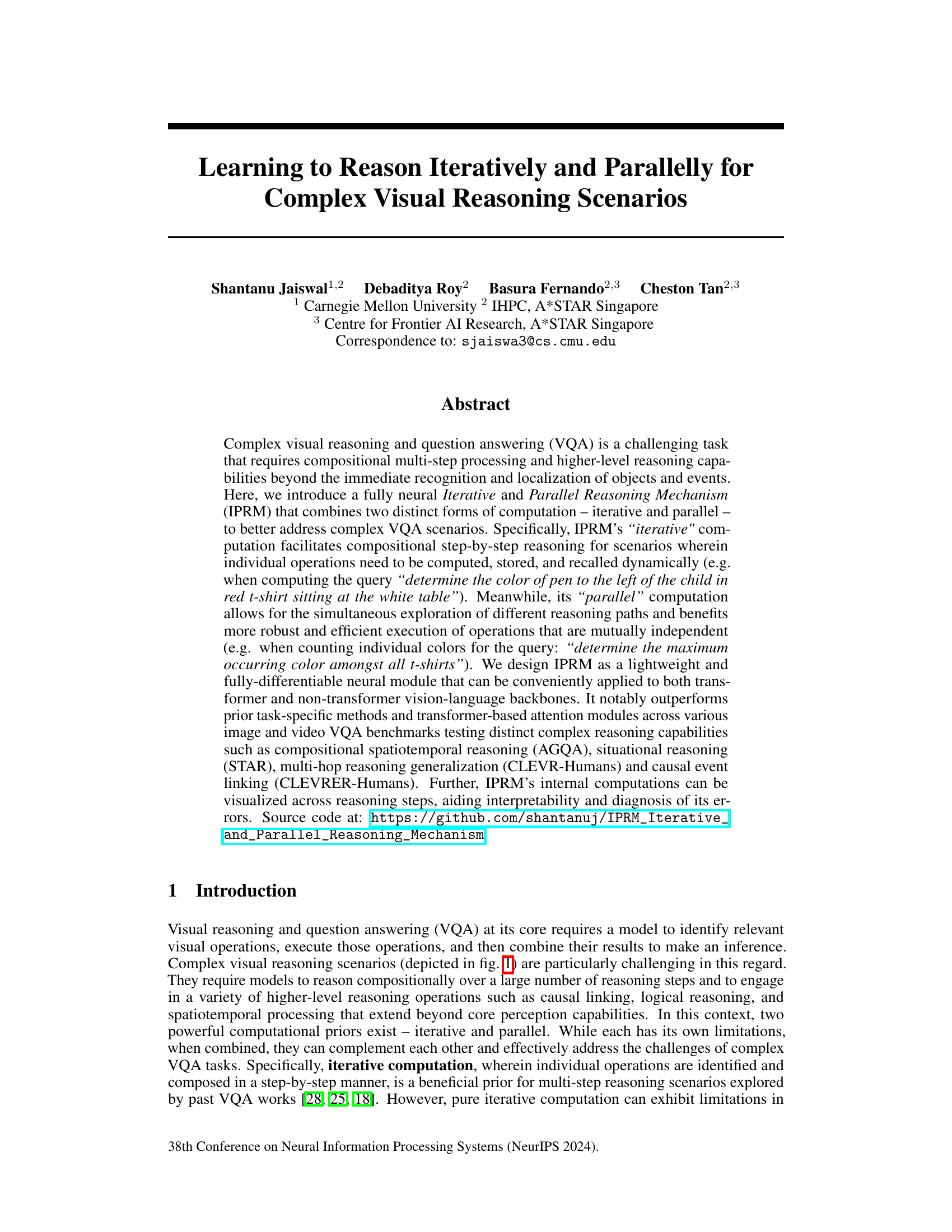

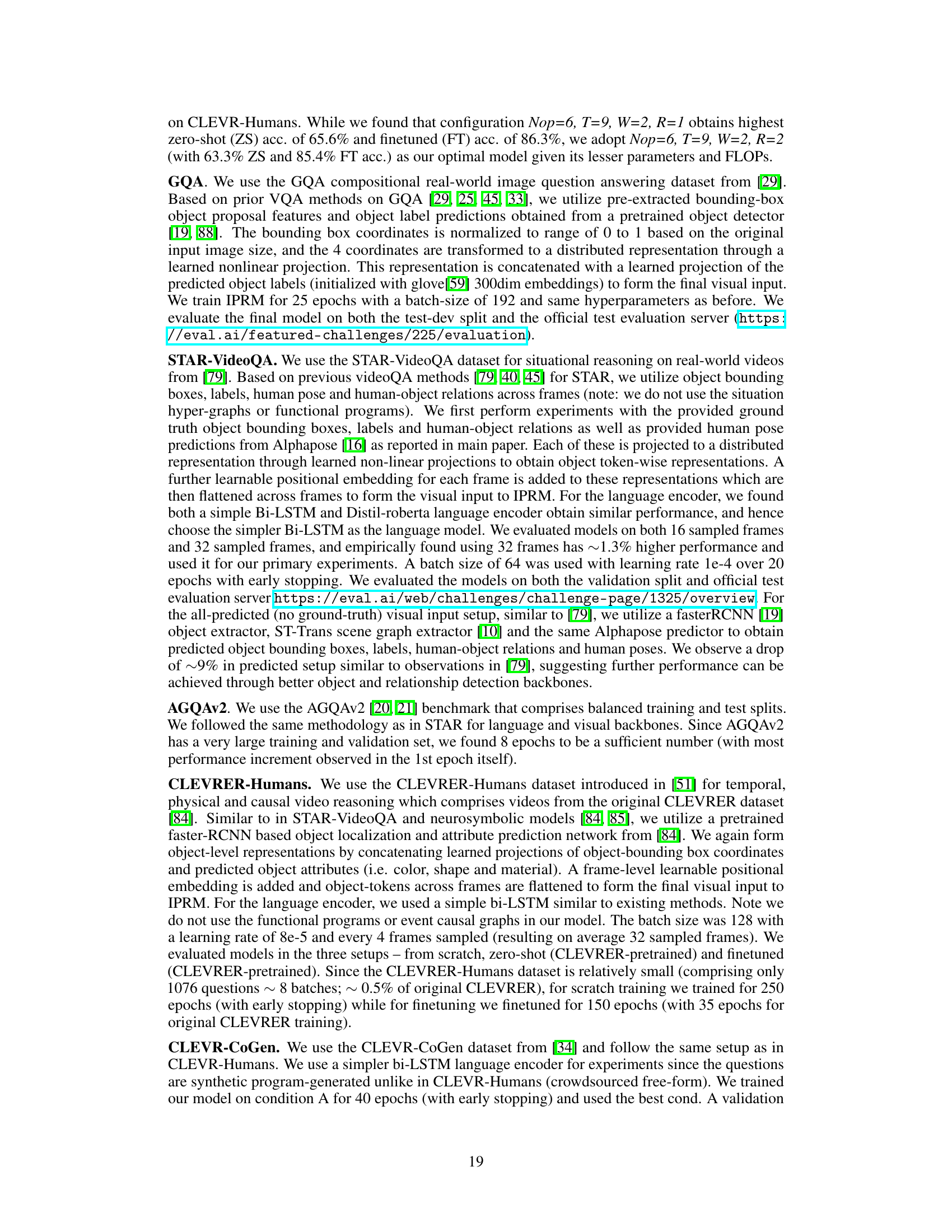

This figure shows five example complex visual question answering (VQA) scenarios. Each scenario is accompanied by a question that requires compositional multi-step reasoning. The questions are color-coded to highlight the parts that are best addressed by iterative reasoning (blue) and parallel reasoning (orange). The scenarios include images and videos with different levels of complexity, demonstrating the benefits of combining iterative and parallel approaches for VQA.

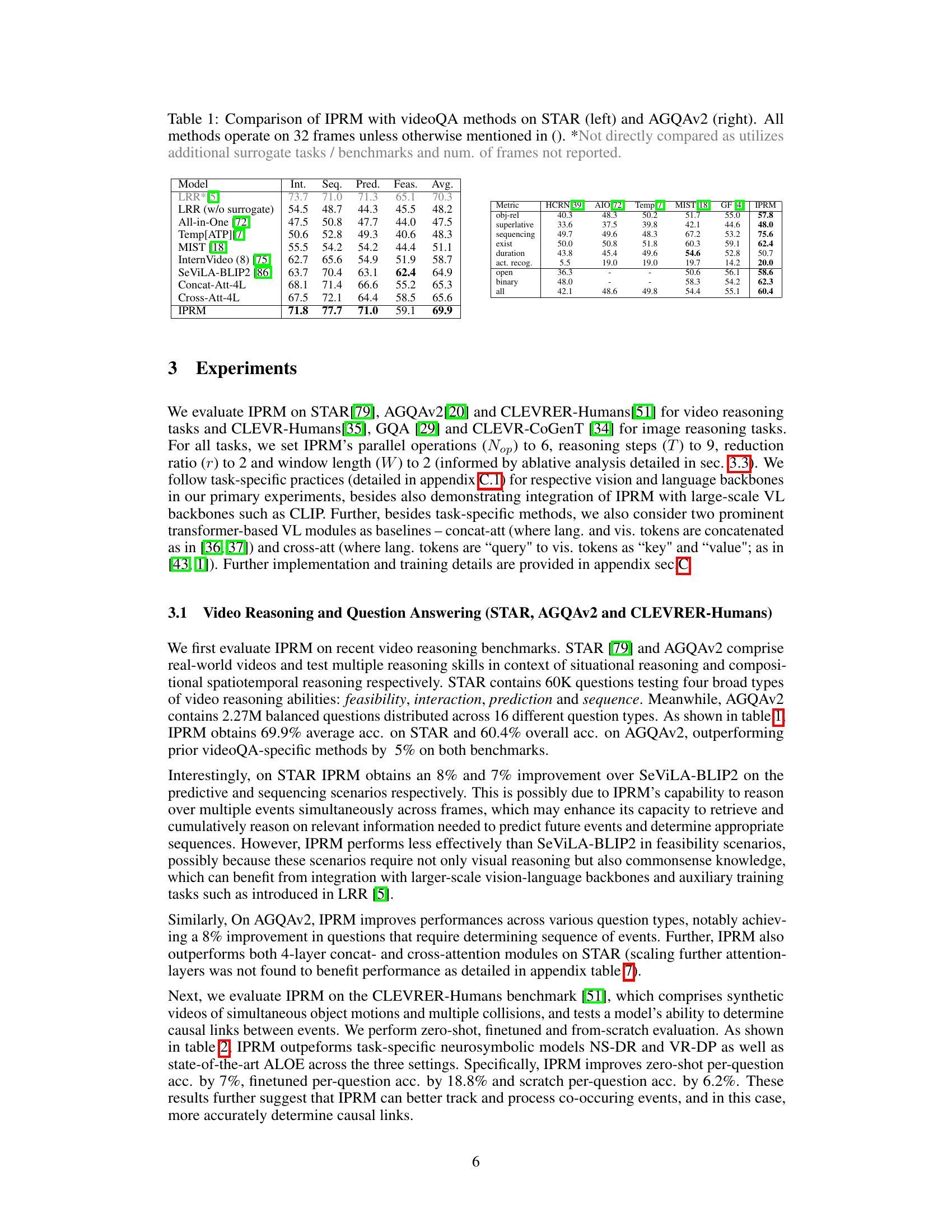

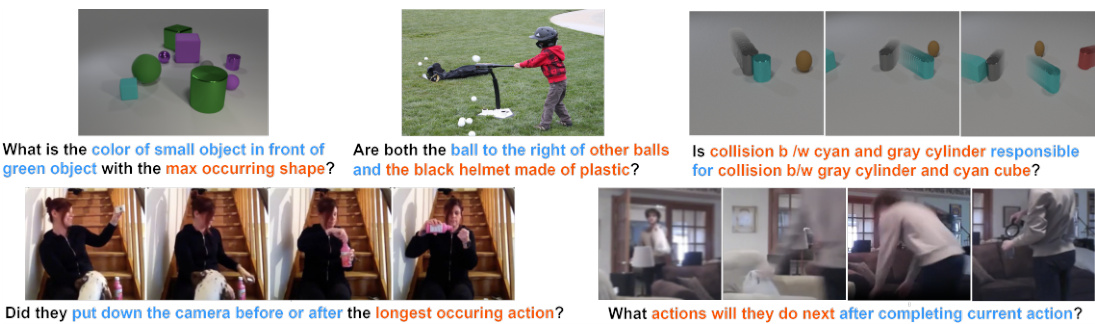

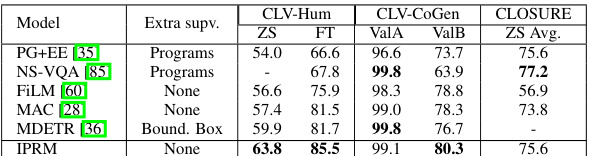

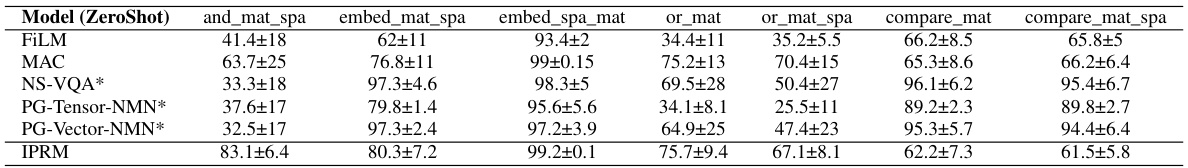

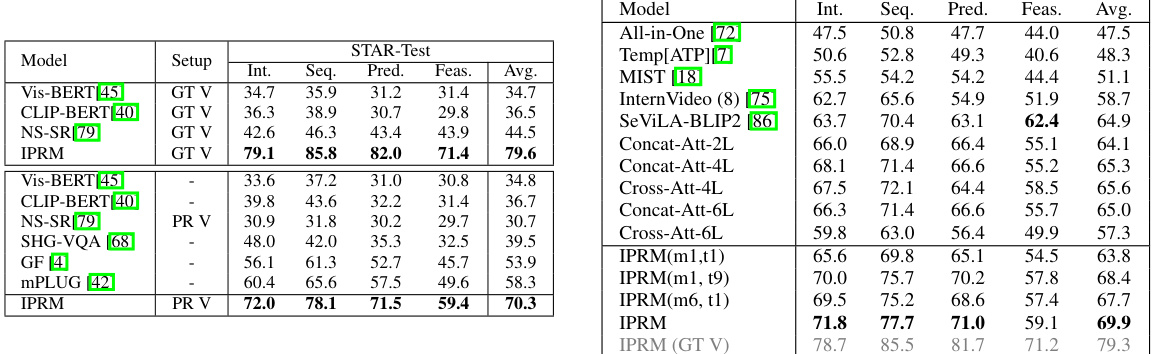

This table compares the performance of the proposed Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) against other state-of-the-art video question answering (VQA) methods on two benchmark datasets: STAR and AGQAv2. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method across different metrics, including the overall accuracy and accuracy for various question subtypes (e.g., feasibility, interaction, prediction, sequencing). It highlights IPRM’s superior performance, particularly on the STAR and AGQAv2 datasets. Note that some methods are not directly compared due to differences in the number of frames used or the inclusion of additional surrogate tasks.

In-depth insights#

Iterative Reasoning#

Iterative reasoning, in the context of complex visual reasoning, involves processing information sequentially, step-by-step. This approach contrasts with parallel processing, which tackles multiple aspects simultaneously. Iterative methods excel in scenarios demanding compositional reasoning, where the output of one step informs the next. This is particularly relevant when the task is to answer a complex question requiring multiple steps of visual analysis and logical inference. The advantages of iterative reasoning include its clarity and interpretability, enabling a better understanding of the decision-making process. However, its serial nature can be computationally expensive compared to parallel strategies, especially when multiple independent operations are involved. Therefore, effective implementations often combine iterative steps with parallel computations where possible, leveraging the strengths of both approaches for efficient and robust solutions.

Parallel Processing#

Parallel processing in the context of complex visual reasoning involves simultaneously exploring multiple reasoning paths to enhance efficiency and robustness. Instead of sequentially processing individual steps, a parallel approach tackles multiple aspects concurrently, which is especially beneficial for problems with independent or easily parallelizable sub-tasks. This approach is particularly useful in visual question answering (VQA) systems that deal with complex scenes and multi-step reasoning. By leveraging parallel computation, these systems can achieve faster and more comprehensive analysis. However, implementing effective parallel processing requires careful design and consideration of data dependencies between tasks to avoid redundant computation or performance bottlenecks. The key lies in identifying and isolating independent operations that can be processed in parallel while maintaining coherence in the overall reasoning process. Algorithms need to be designed to effectively manage and combine the results from parallel computations to produce a unified and accurate answer. A successful implementation of parallel processing can significantly improve the speed and accuracy of complex visual reasoning systems, making them more suitable for real-time applications and large-scale problems.

Visual Attention#

Visual attention mechanisms are crucial in computer vision, enabling models to selectively focus on image regions most relevant to a task. Effective visual attention is critical for complex visual reasoning tasks because it helps manage the computational complexity of processing large amounts of visual information. Many existing models use attention to combine visual and textual information; however, limitations exist in scenarios demanding multi-step reasoning or parallel processing of independent visual cues. The design of sophisticated attention mechanisms that can handle these complexities is an active area of research, with various approaches proposed to improve model accuracy and interpretability. A deeper understanding of how attention works can reveal valuable insights into the cognitive processes involved in human vision and pave the way for more efficient and robust visual reasoning systems. Future improvements might explore more powerful attention architectures to handle the long-range dependencies often present in complex visual scenes.

Benchmark Results#

A thorough analysis of benchmark results would involve examining the specific datasets used, the metrics employed for evaluation, and the relative performance of the proposed model compared to existing state-of-the-art methods. Key aspects to consider include: the diversity and complexity of the benchmarks (do they adequately reflect real-world scenarios?), the appropriateness of the chosen metrics (do they accurately capture the model’s strengths and weaknesses?), and the statistical significance of the performance differences (are the improvements statistically meaningful?). Additionally, it is essential to address any limitations of the benchmarks or the evaluation methodology that might affect the interpretation of the results. Finally, by carefully considering these factors, one can gain a nuanced understanding of the model’s capabilities and limitations, and identify areas for future improvement. Visualizations of the results, such as graphs and tables, are important for effective communication.

Future Directions#

Future research should explore extending IPRM’s capabilities to handle more complex reasoning tasks and larger-scale datasets. Addressing biases present in training data and mitigating potential negative societal impacts are crucial. Investigating integration with large language models to enhance performance and generalization is also a promising avenue. Furthermore, exploring IPRM’s applicability beyond VQA, to tasks like language processing and embodied reasoning, could unlock valuable insights. Visualizations of internal computations should be further developed to improve interpretability and facilitate error diagnosis. Finally, research into improving efficiency and reducing computational cost is essential for wider adoption.

More visual insights#

More on figures

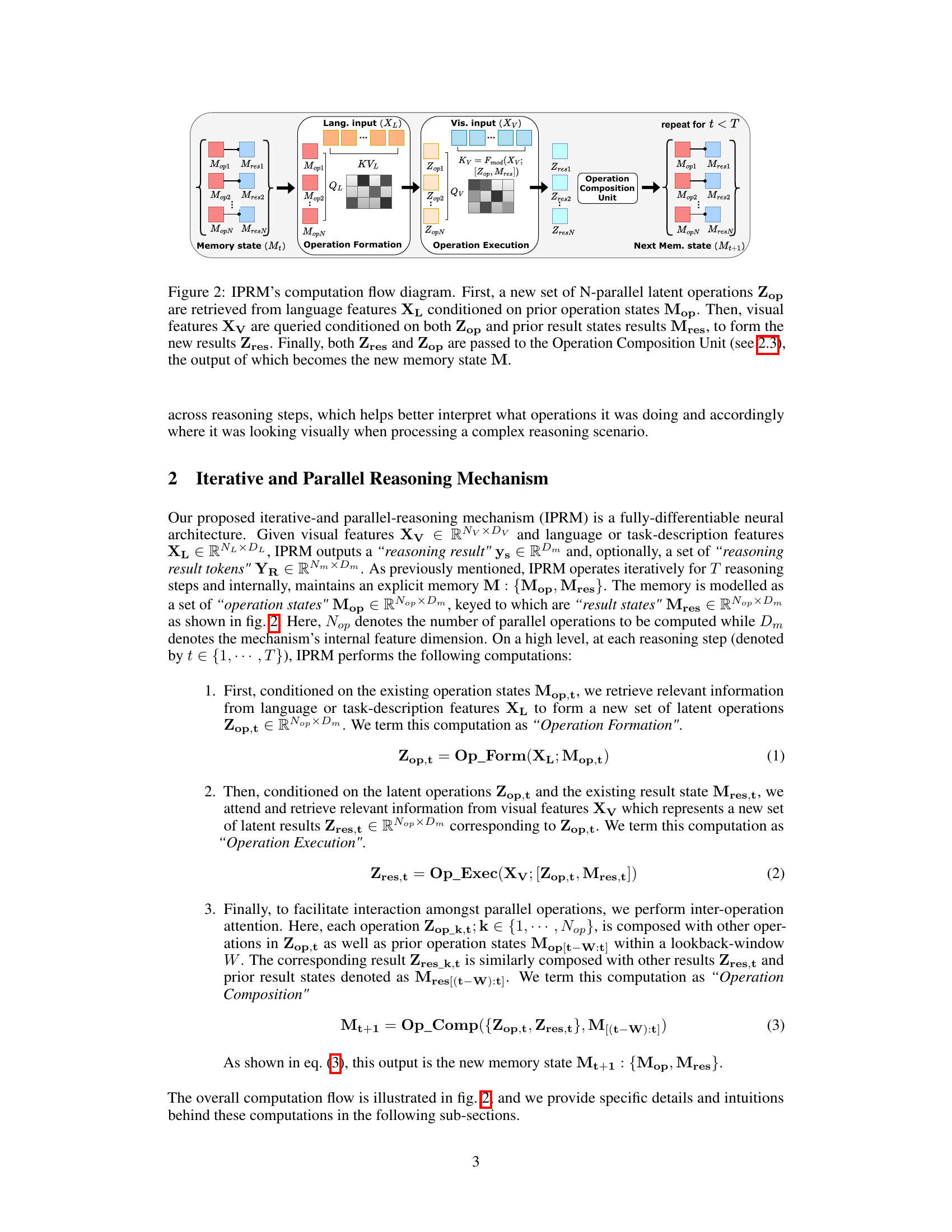

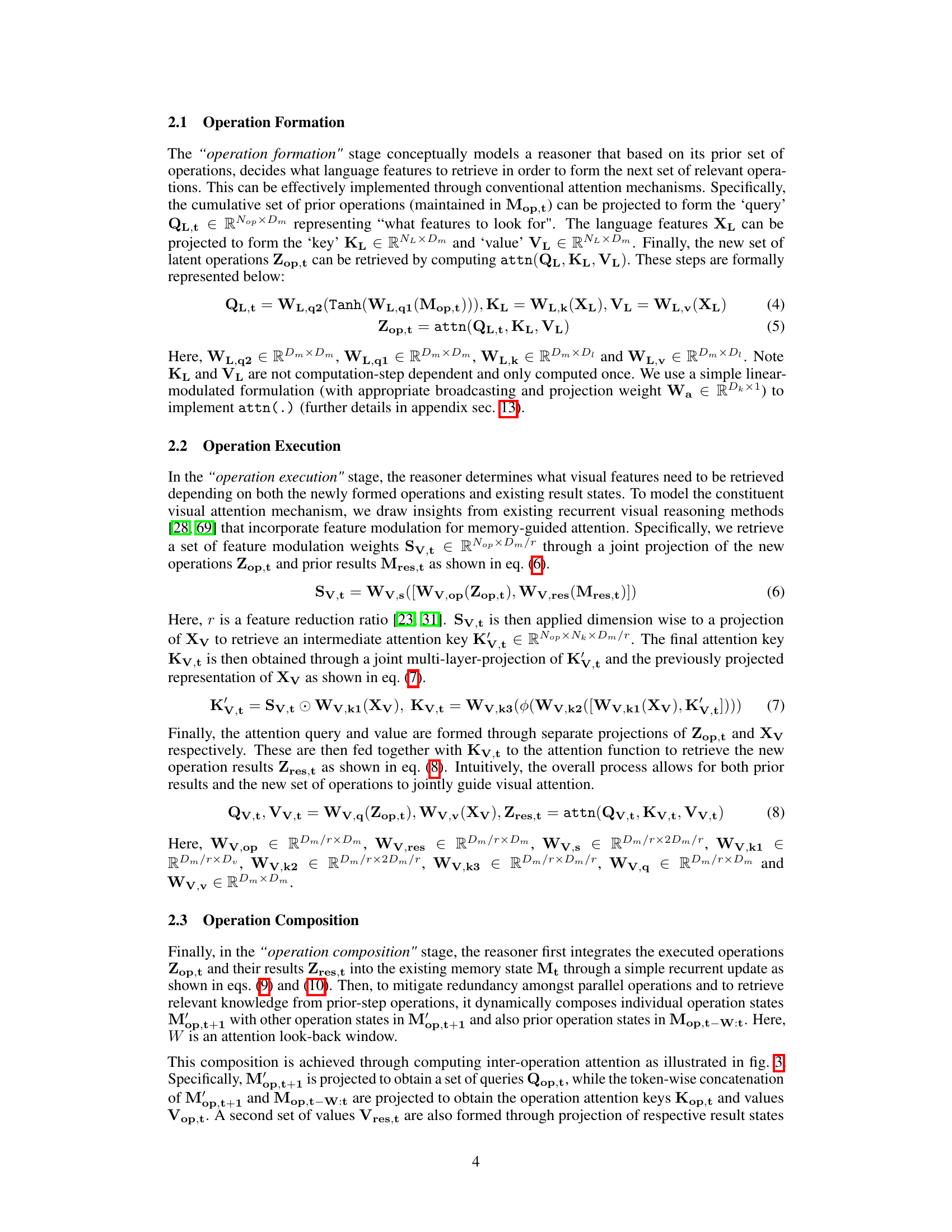

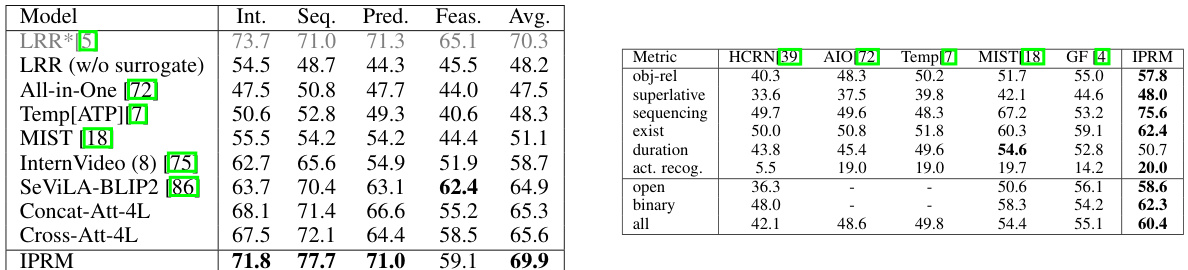

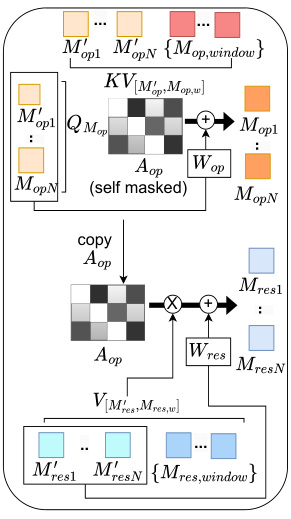

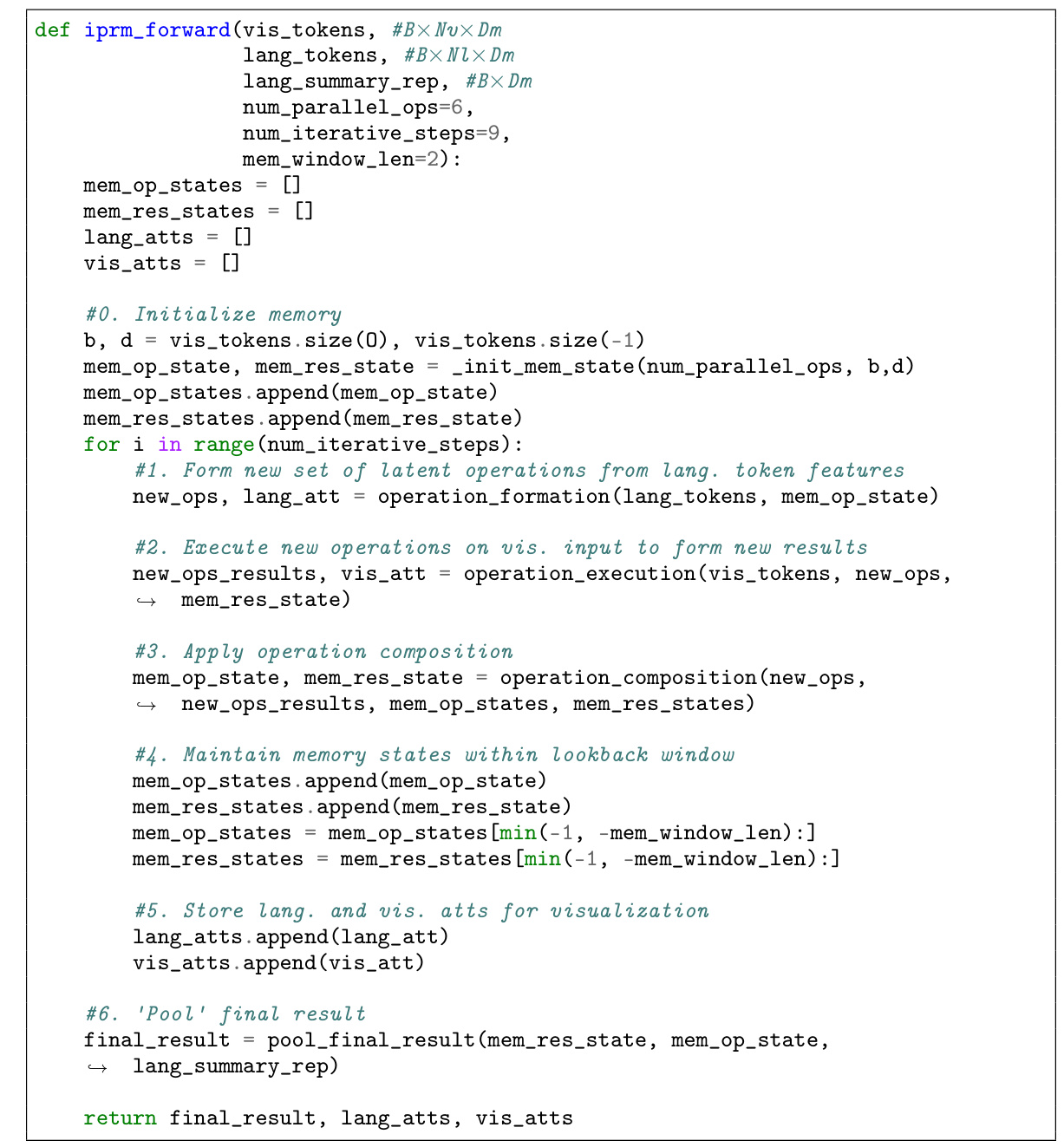

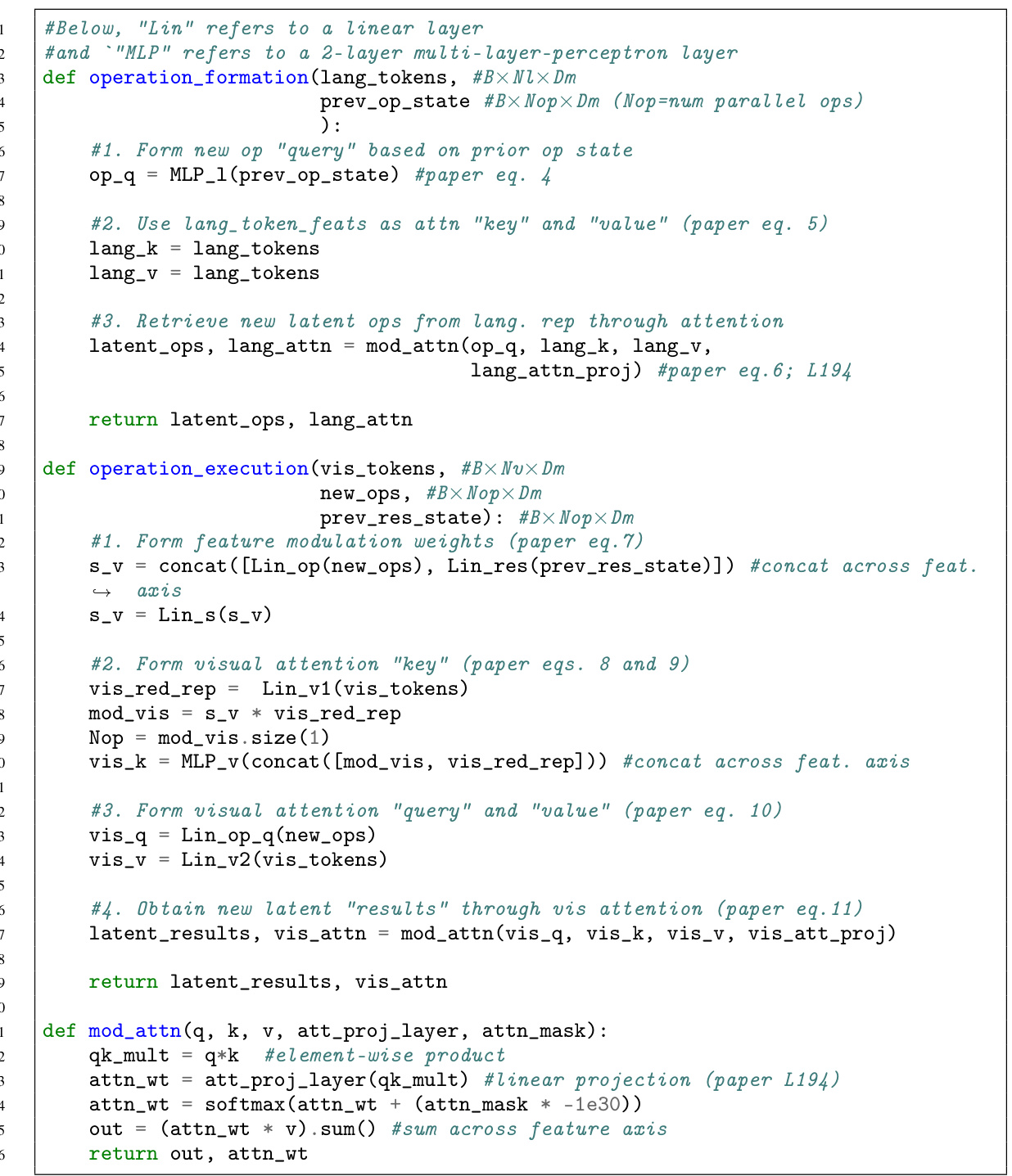

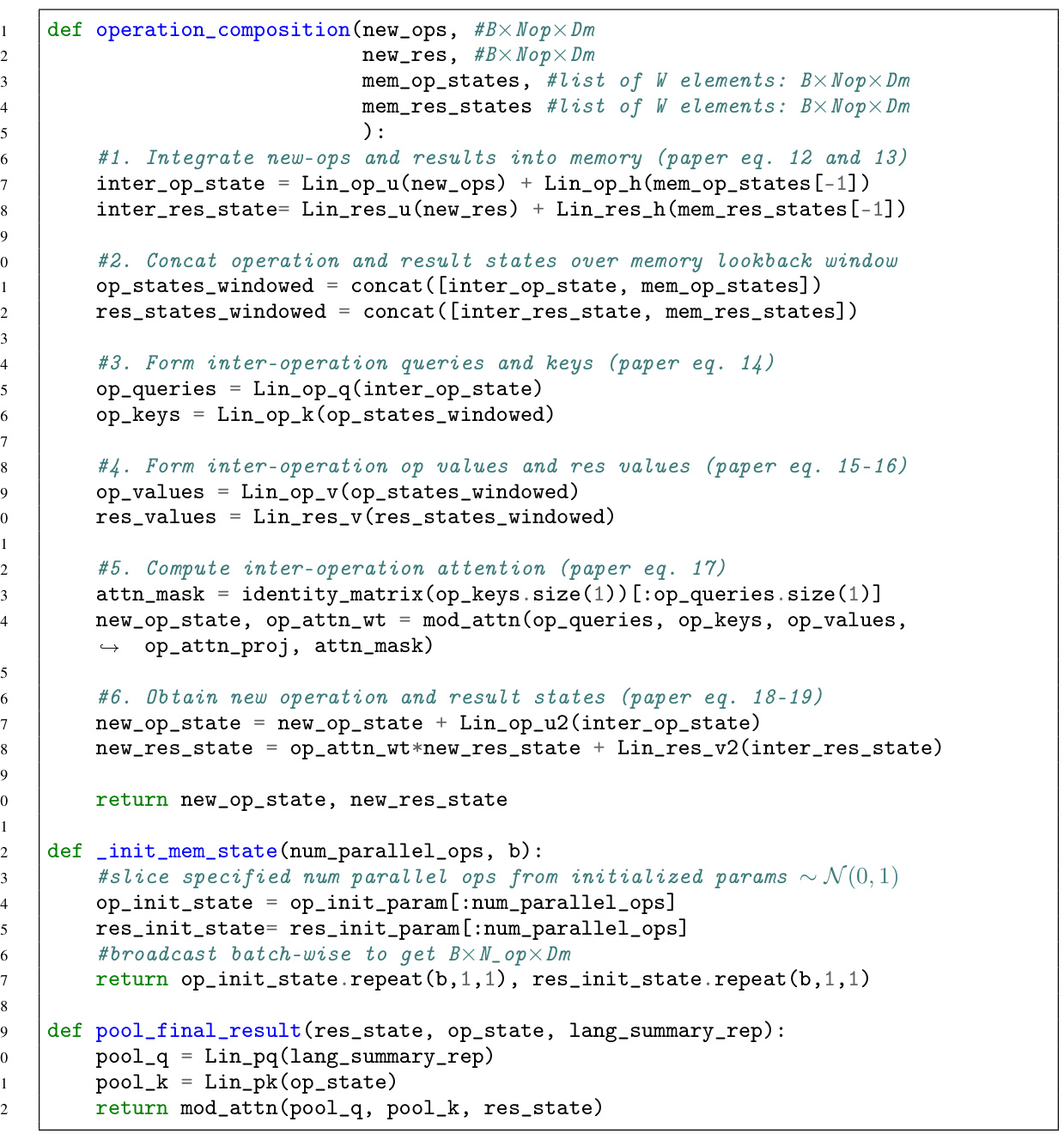

This figure shows the computation flow diagram of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). The process starts with language and visual inputs. The IPRM first forms a new set of parallel latent operations based on the prior operation states and language features. Then, it executes these operations in parallel using the visual features, prior result states, and newly formed operations. Finally, it integrates these operations and results using an operation composition unit to update the memory state. This iterative process repeats for T reasoning steps.

The figure illustrates the computation flow of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). It shows how IPRM iteratively processes visual and language information to generate a reasoning result. At each iteration, it performs three steps: (1) operation formation: retrieves new parallel latent operations from language features based on prior operation states; (2) operation execution: retrieves visual information based on latent operations and prior results, and (3) operation composition: integrates the new operations and their results with previous memory states to update memory. The process repeats until the final reasoning result is obtained.

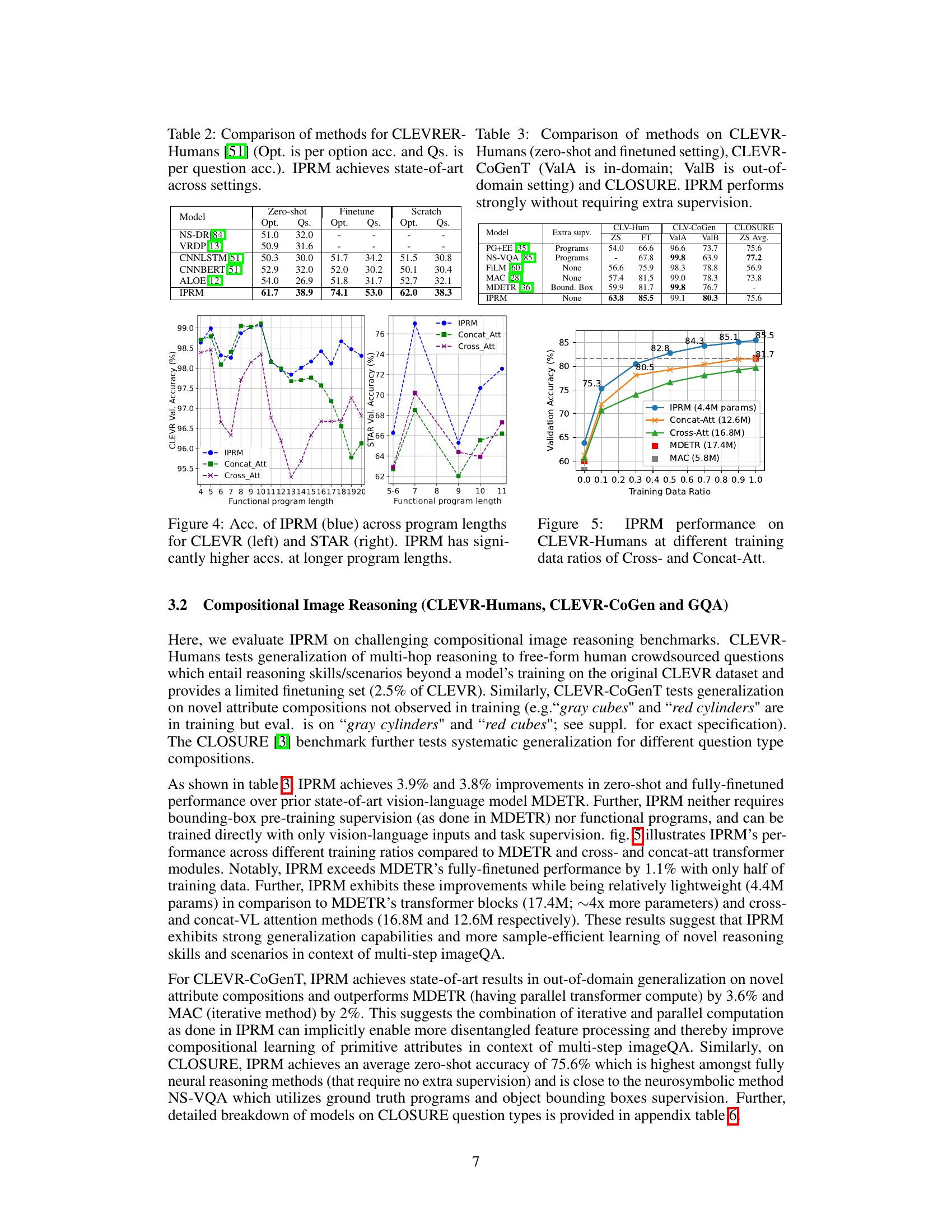

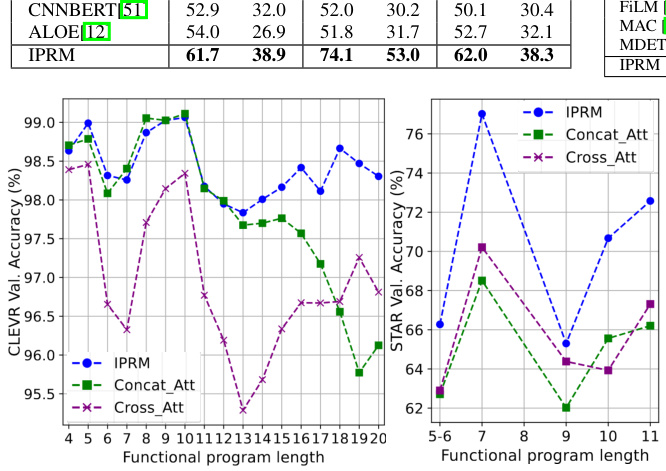

This figure shows the performance of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) model compared to two baseline models (Concat-Att and Cross-Att) on the CLEVR and STAR datasets. The x-axis represents the length of the functional program, which is a measure of the complexity of the reasoning task. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the models. The figure demonstrates that IPRM achieves significantly higher accuracy than the baseline models, especially on more complex reasoning tasks (longer functional programs). This highlights IPRM’s ability to handle multi-step reasoning.

This figure shows the performance of the IPRM model (Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism) on the CLEVR-Humans dataset, comparing it against two baselines: Concat-Att and Cross-Att. The x-axis represents the ratio of training data used, and the y-axis shows the validation accuracy. The figure demonstrates that IPRM achieves higher validation accuracy with less training data compared to both baselines, highlighting its sample efficiency. The figure also includes the performance of MDETR and MAC for comparison.

This figure shows the ablation study of IPRM model by varying different hyperparameters. The impact of changing the number of parallel operations and computation steps is shown in the first subplot. The second subplot shows the impact of using or not using the operation composition block. The third and fourth subplots show the impact of reduction ratio and memory window length respectively.

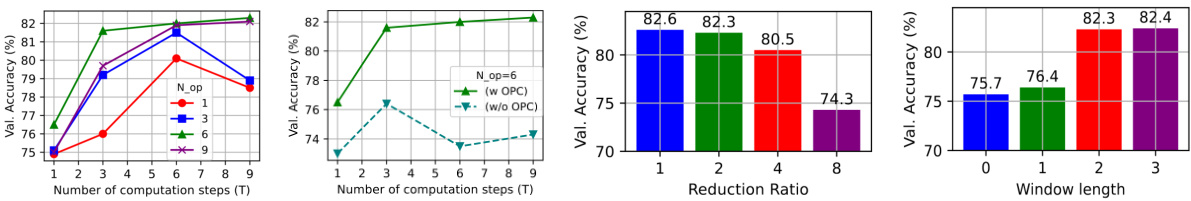

This figure shows examples of complex Visual Question Answering (VQA) scenarios where a combination of iterative and parallel computation is beneficial. The examples highlight tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, such as determining the color of an object based on its relative position to other objects, or counting the maximum occurrence of a shape.

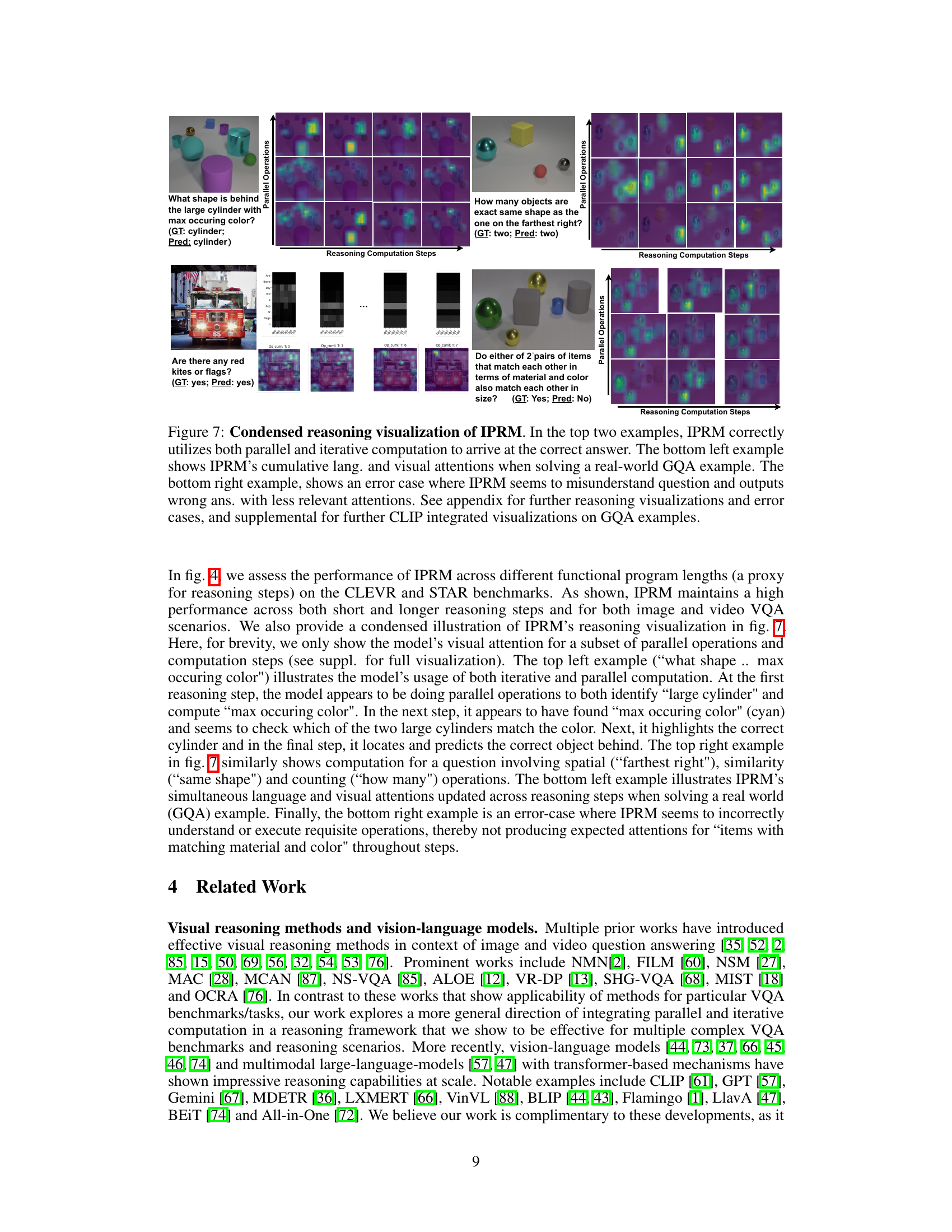

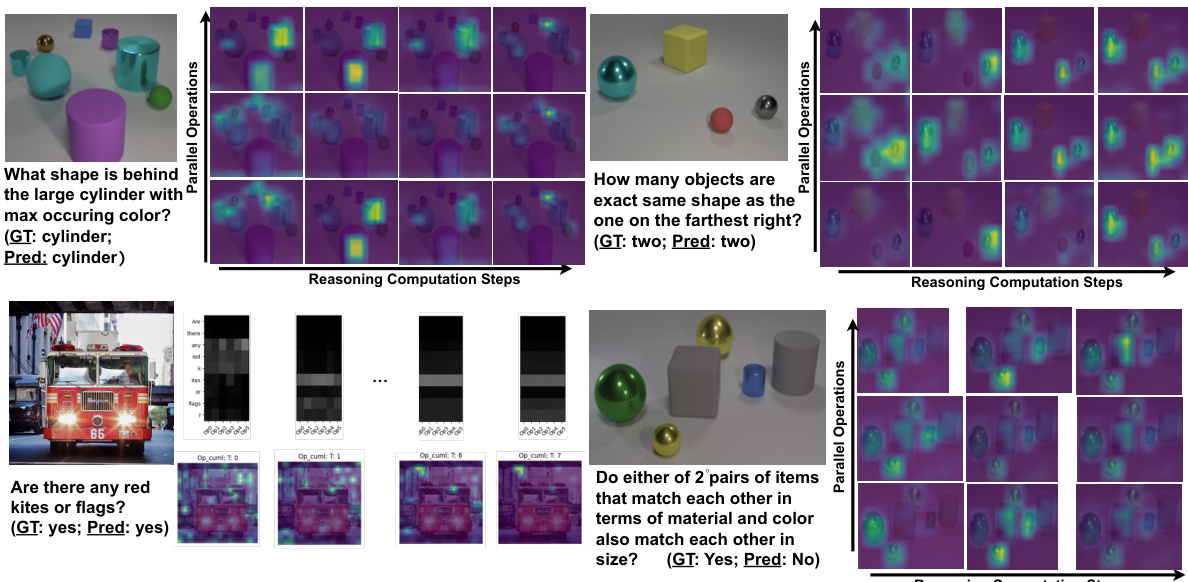

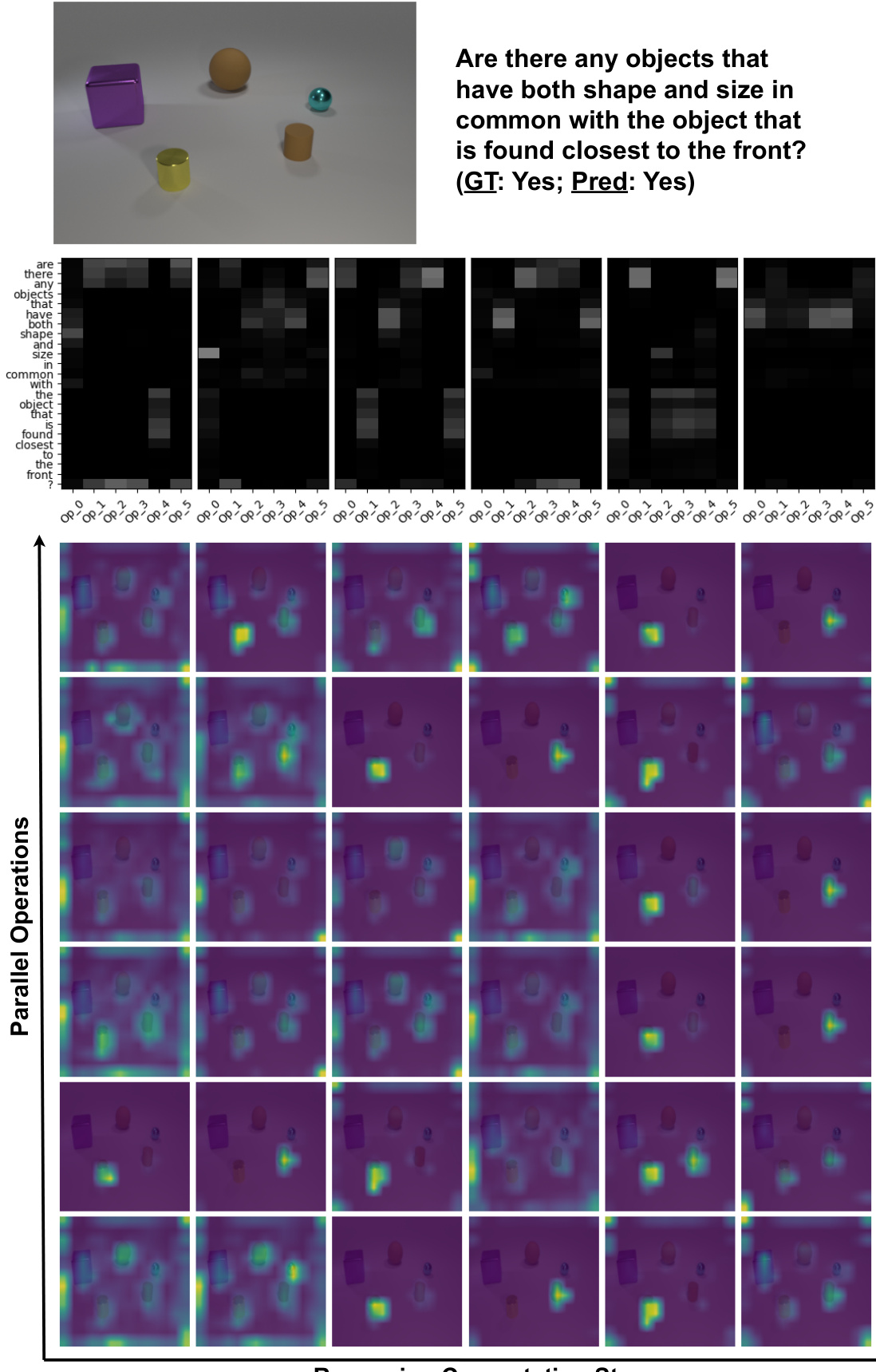

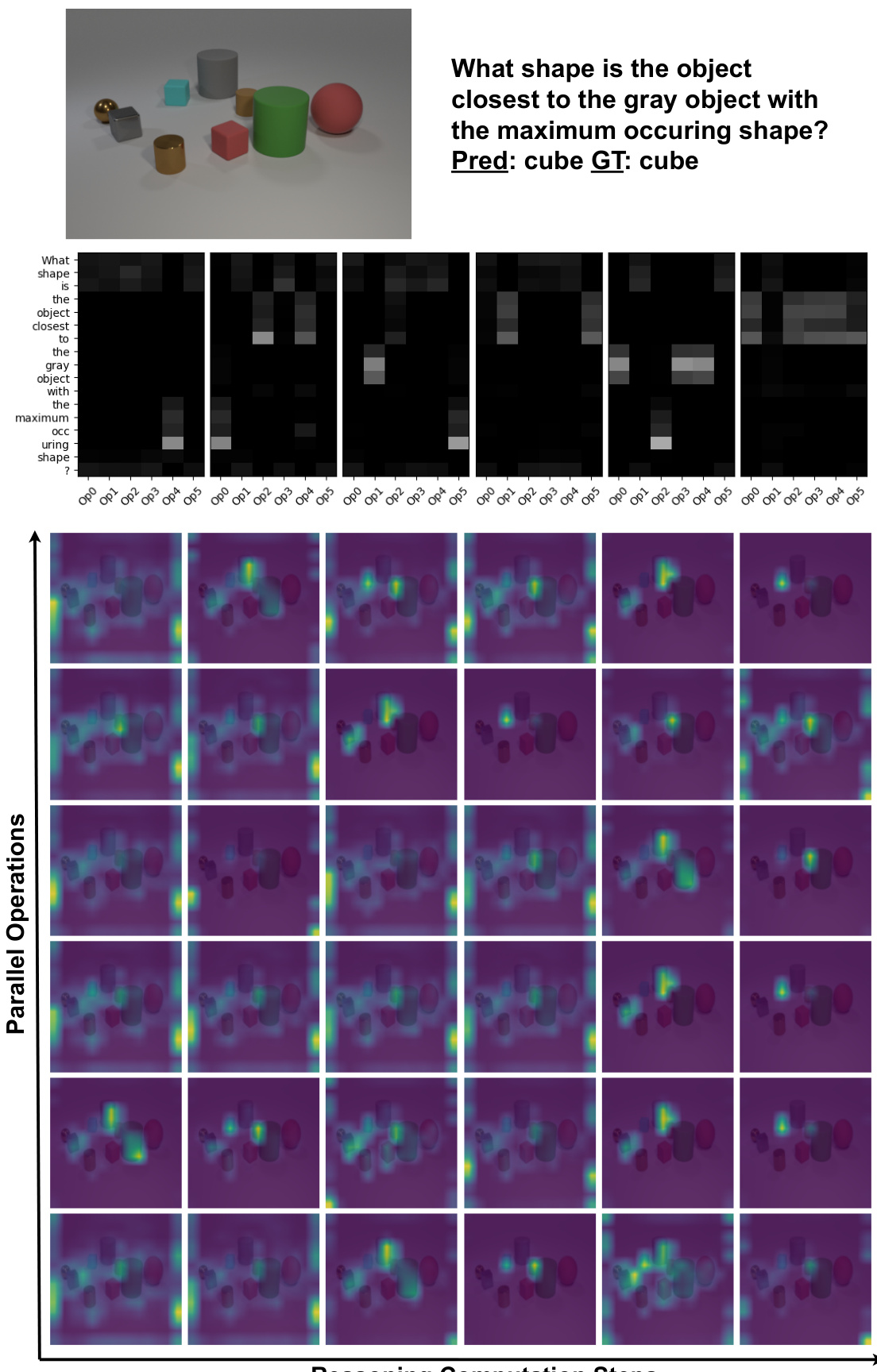

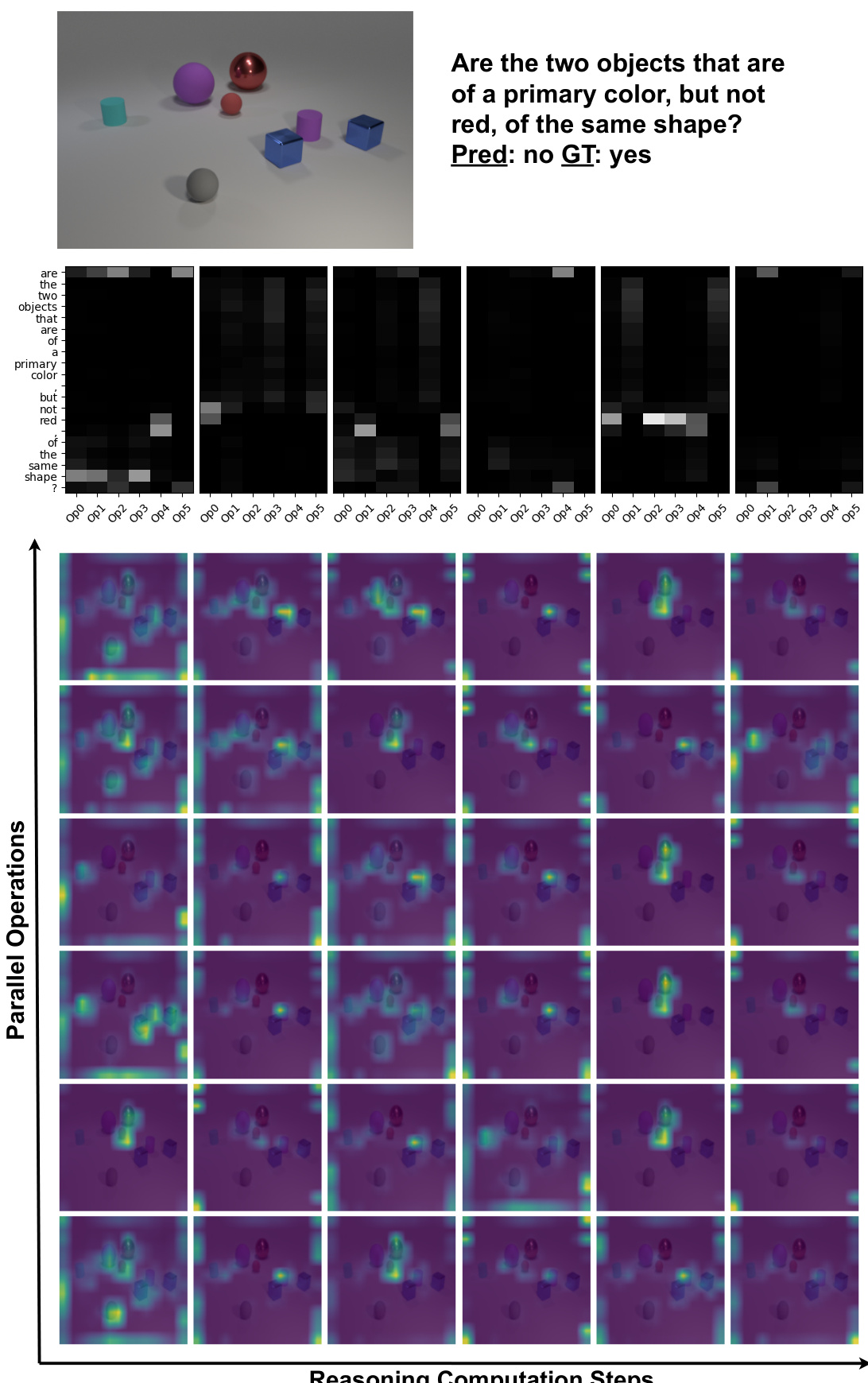

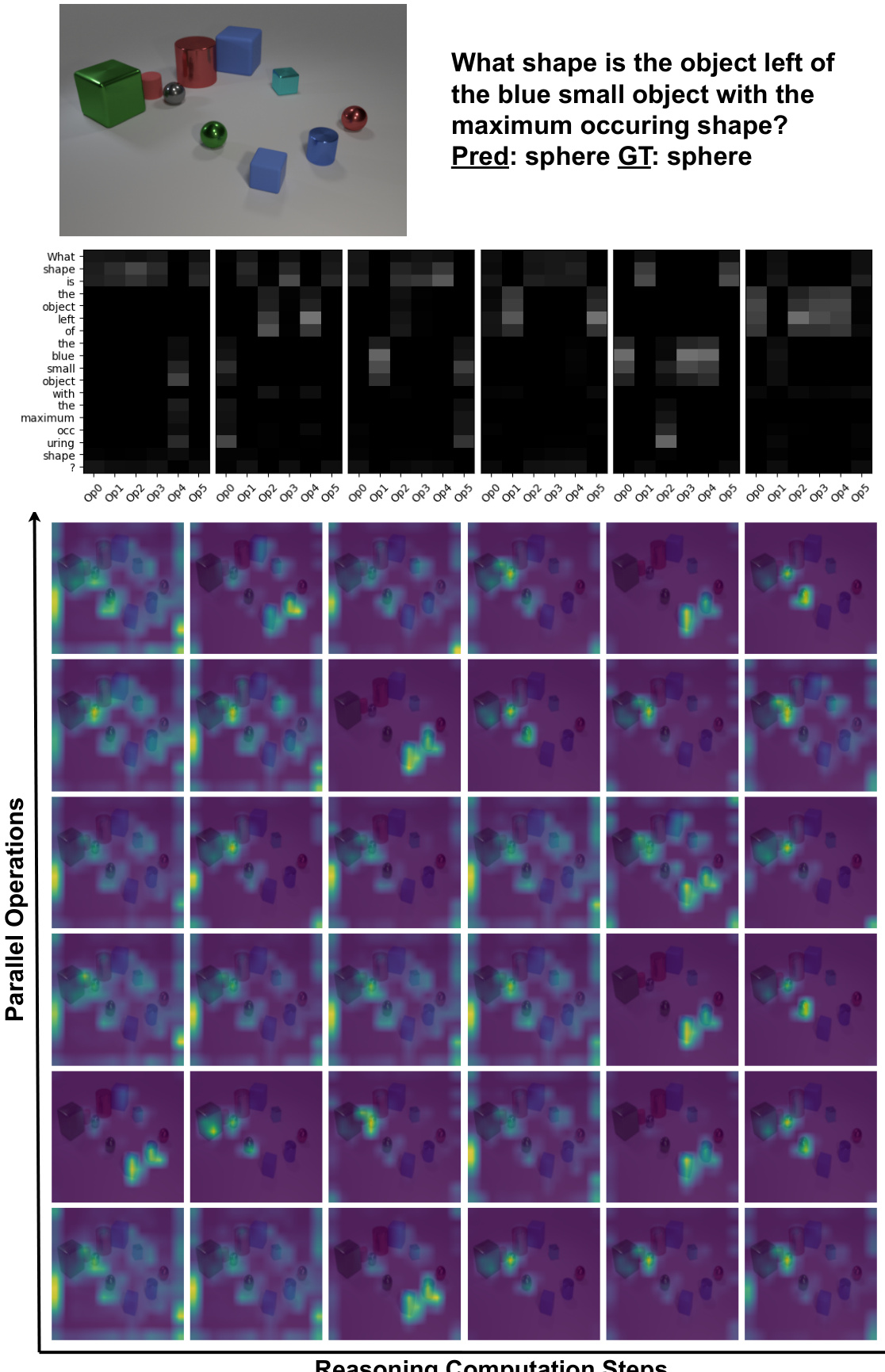

This figure shows four examples of how IPRM’s internal computations are visualized across reasoning steps. The top two examples illustrate correct reasoning using both iterative and parallel computation. The bottom left shows a correct answer on a real-world GQA example, highlighting the attention weights. The bottom right shows an error, indicating that IPRM may have misinterpreted the question.

This figure visualizes the intermediate reasoning steps of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) model for a specific question. The top shows the original image and question. The middle shows the language attention weights. The bottom shows the visual attention weights across parallel operations and reasoning computation steps. The visualization demonstrates how IPRM uses both iterative and parallel computation to correctly identify and locate the relevant object for the question.

This figure shows an example where the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) model incorrectly answers a question. The visualization shows that the model did not correctly identify the ‘primary color’ mentioned in the question. The pair of blue cubes, which are a primary color, were not attended to by the model’s operations. This suggests a potential failure in understanding the concept of ‘primary colors’, which is a crucial element in correctly answering the question.

This figure showcases several complex visual question answering (VQA) scenarios where a combination of iterative and parallel reasoning is beneficial. The examples highlight tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, such as determining the color of an object based on its relative position to other objects, or identifying the maximum occurring shape among a set of objects. The blue phrases represent steps that benefit from iterative (step-by-step) processing, while the orange phrases illustrate those that can be efficiently computed in parallel.

This figure shows the computation flow diagram of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). It details the three main steps: Operation Formation, Operation Execution, and Operation Composition. Operation Formation retrieves relevant information from language features conditioned on previous operation states. Operation Execution retrieves visual information based on newly formed operations and previous results. Operation Composition integrates new and previous operations to form the new memory state. This process repeats iteratively for a fixed number of steps, with the final output being a ‘reasoning result’.

The figure illustrates the computation flow of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). It shows how IPRM iteratively processes information from language and visual features by forming parallel latent operations and results and composing them into a new memory state. This process repeats across multiple reasoning steps, facilitating both parallel and iterative computations. The figure helps visualize the internal operations and reasoning steps of IPRM.

This figure illustrates the computation flow of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM). It shows how IPRM iteratively processes information in three main steps: Operation Formation, Operation Execution, and Operation Composition. In the Operation Formation step, new parallel operations are generated from language features, conditioned on the previous memory state. The Operation Execution step retrieves visual information relevant to these new operations, also conditioned on previous results. Finally, the Operation Composition unit combines the results of the parallel operations and updates the memory state for the next iteration.

More on tables

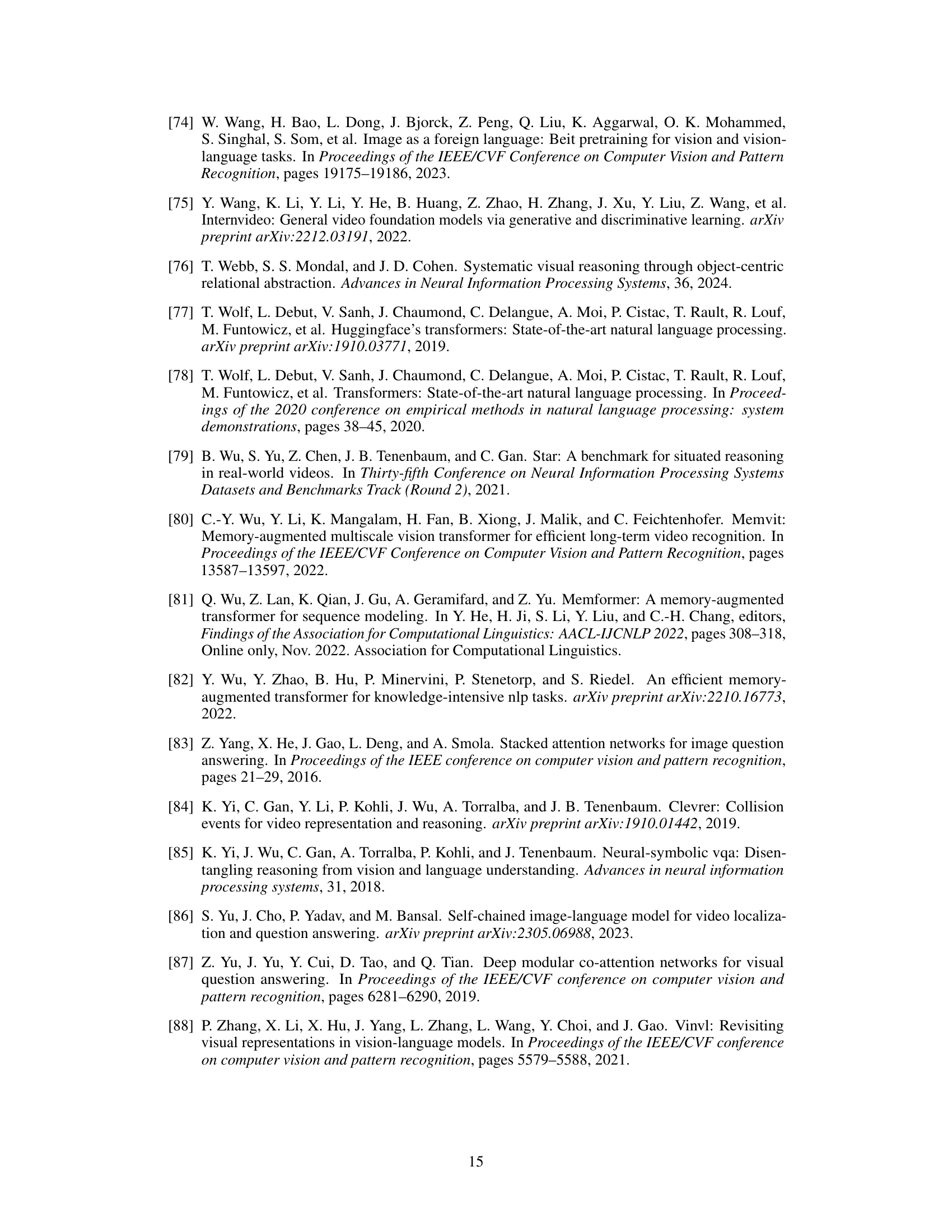

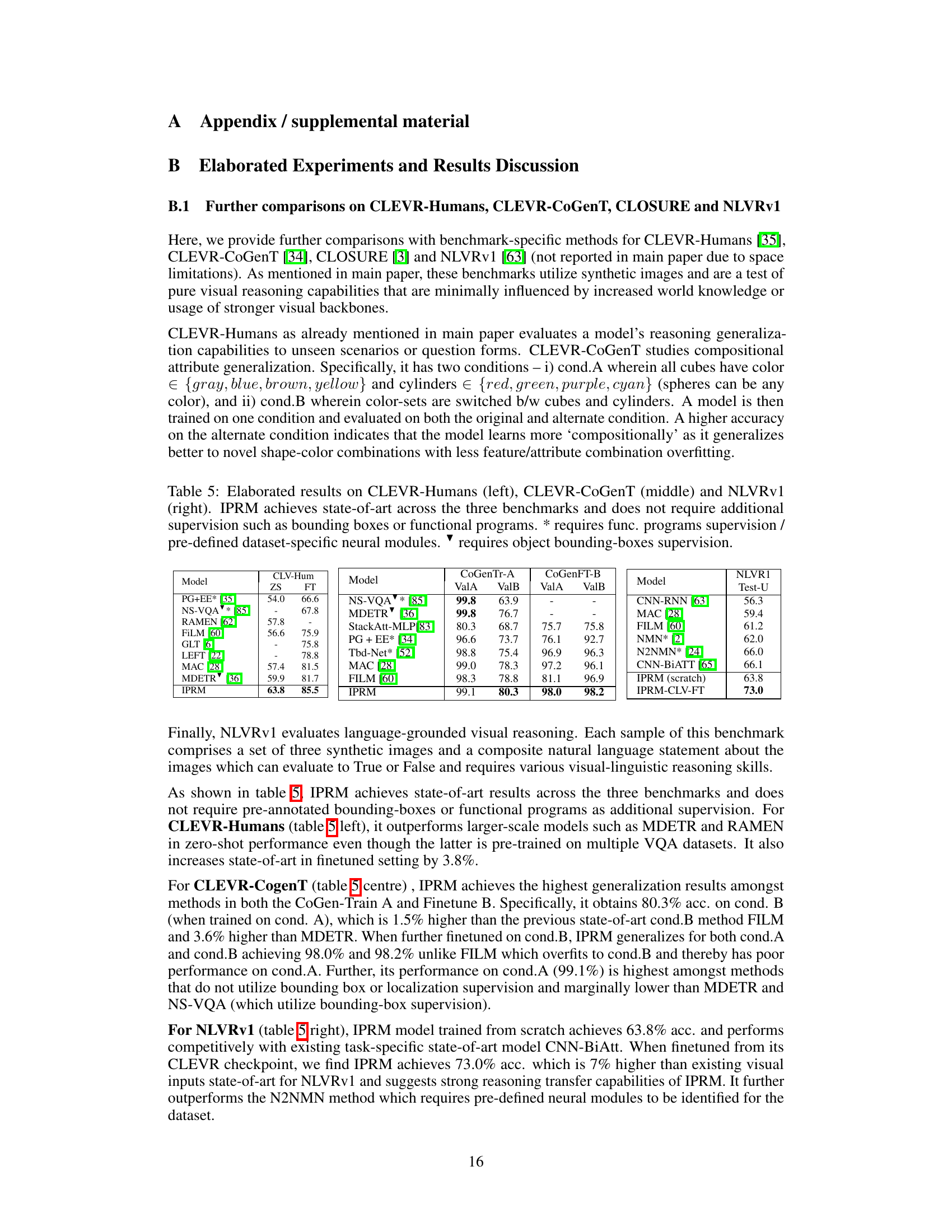

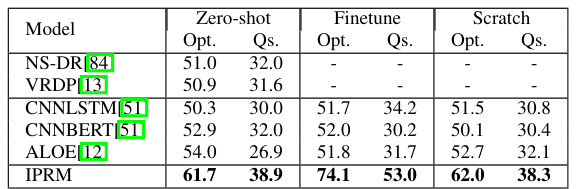

This table compares the performance of different methods on the CLEVRER-Humans benchmark for video reasoning. The methods are evaluated using two metrics: per-option accuracy (Opt.) and per-question accuracy (Qs.). The results are shown for three different training settings: zero-shot, finetuned, and scratch. The table highlights that IPRM achieves state-of-the-art performance across all three training settings.

This table compares the performance of IPRM against other methods on the CLEVRER-Humans benchmark for video reasoning. The benchmark tests the model’s ability to determine causal links between events in synthetic videos. The table shows the per-option accuracy (Opt.) and per-question accuracy (Qs.) for various methods, categorized by zero-shot (no training on the specific task), finetuned (trained on the task), and scratch (trained from scratch) settings. The results highlight that IPRM achieves state-of-the-art performance across all settings.

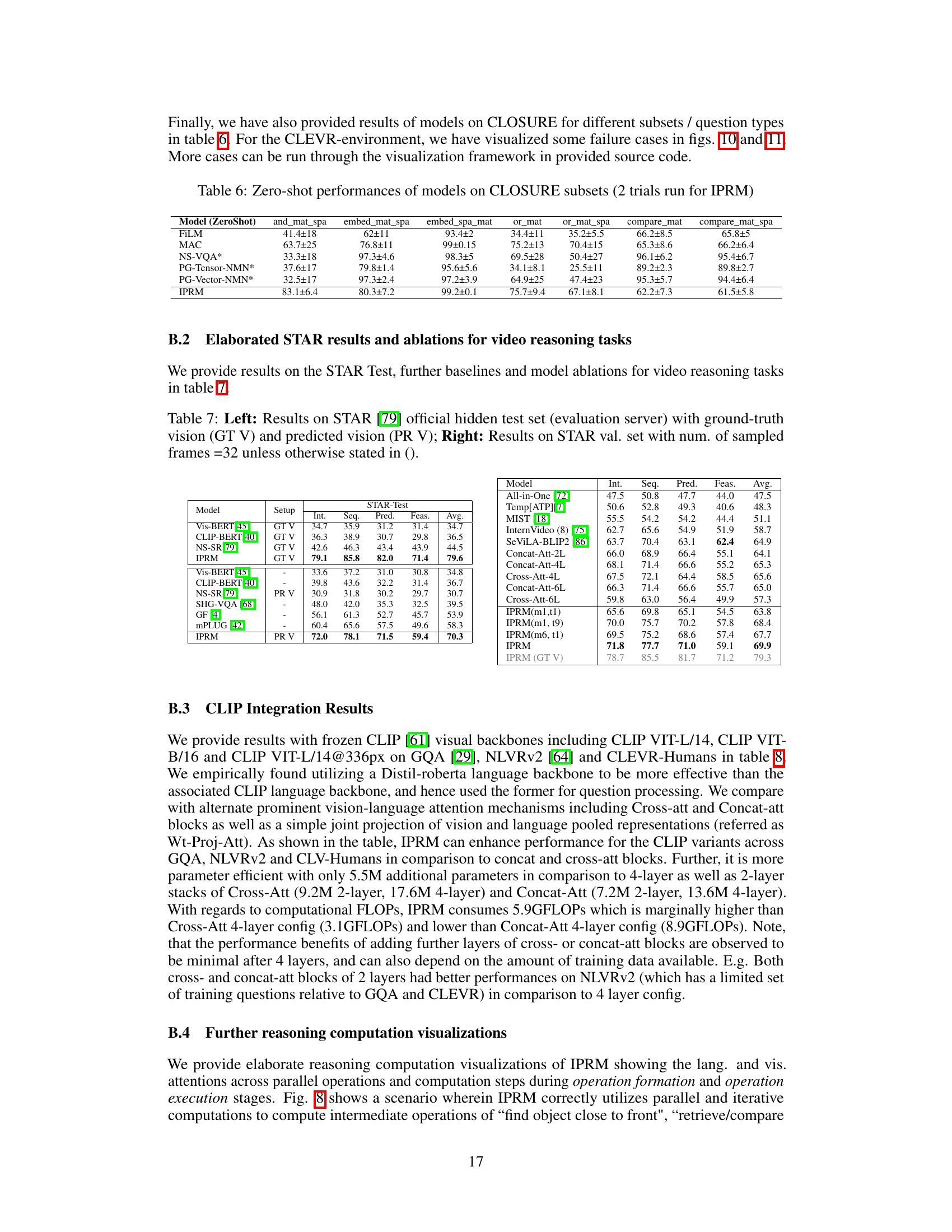

This table compares the performance of the Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) against other video question answering (VQA) methods on two benchmark datasets: STAR and AGQAv2. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on various subtasks within each benchmark. Note that some methods are not directly comparable due to differences in their experimental setup, such as the use of additional surrogate tasks or different numbers of video frames.

This table compares the performance of IPRM with other methods on the CLEVRER-Humans benchmark for video reasoning. The benchmark evaluates the model’s ability to determine causal links between events in synthetic videos. The table shows that IPRM achieves state-of-the-art performance across different evaluation settings (zero-shot, finetuned, and from scratch).

This table compares the performance of the proposed Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) against other state-of-the-art video question answering (VQA) methods on two benchmark datasets: STAR and AGQAv2. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on different aspects of video reasoning, such as interaction, prediction, and feasibility. It highlights that IPRM outperforms other methods on both datasets.

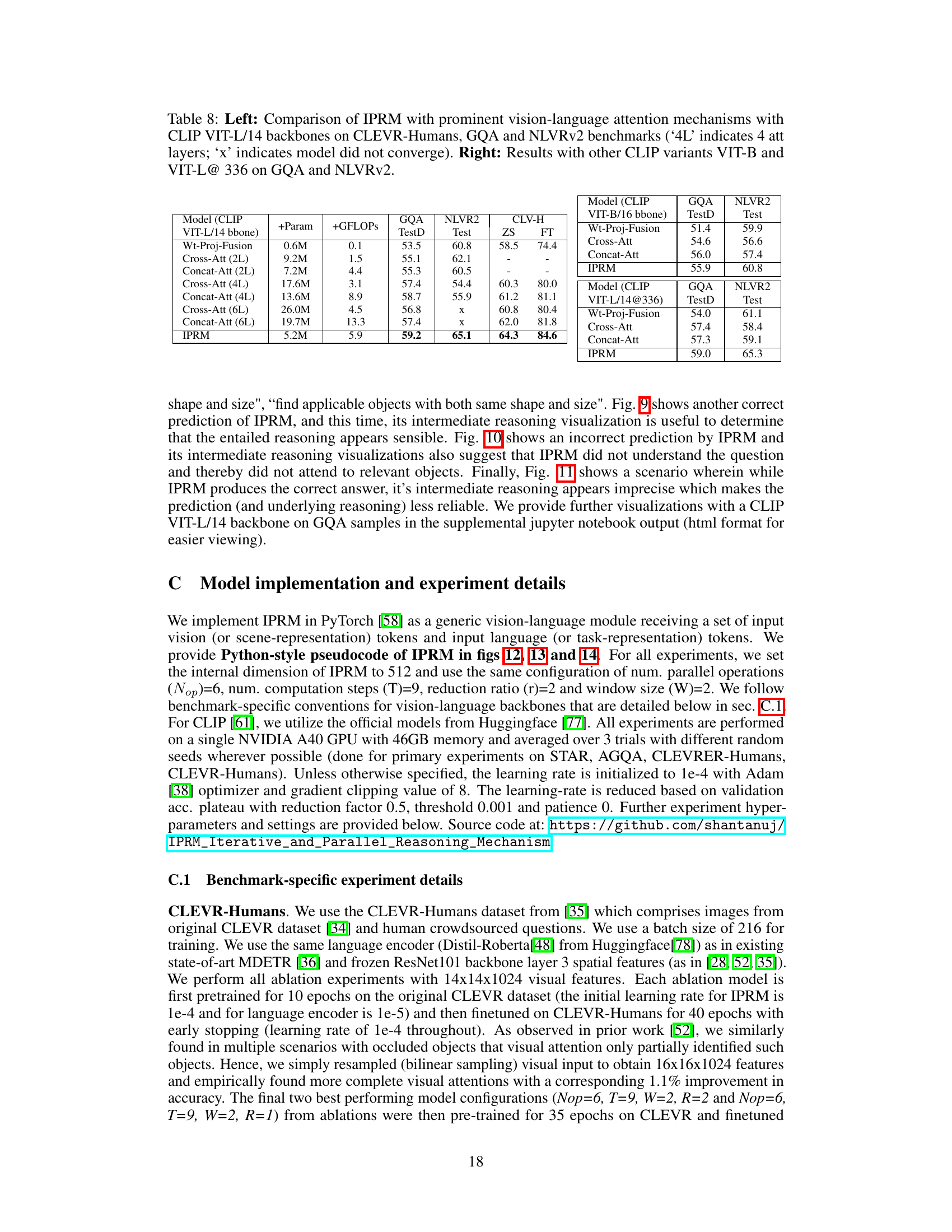

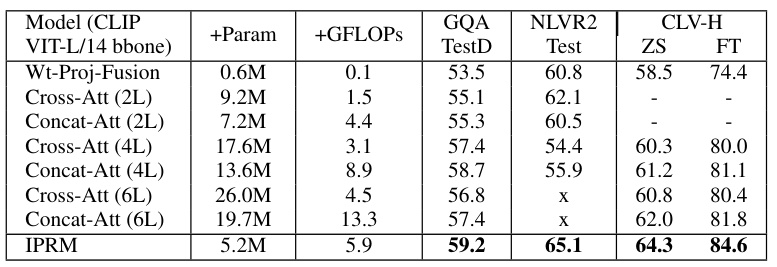

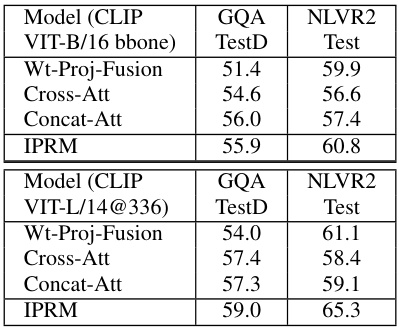

This table compares the performance of IPRM against other prominent vision-language attention mechanisms (Cross-Att, Concat-Att, and Wt-Proj-Fusion) using different CLIP backbones (VIT-L/14, VIT-B/16, and VIT-L/14@336). The comparison is done across three benchmarks: CLEVR-Humans, GQA, and NLVR2. The table shows the number of additional parameters (+Param), GFLOPs, and the accuracy (TestD for GQA, Test for NLVR2, and Zero-shot/Finetuned for CLEVR-Humans). It highlights that IPRM achieves superior performance with fewer parameters and GFLOPs compared to the other methods.

This table compares the performance of the proposed Iterative and Parallel Reasoning Mechanism (IPRM) against other video question answering (VQA) methods on two benchmark datasets: STAR and AGQAv2. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on several sub-tasks within each dataset, highlighting IPRM’s superior performance, especially on tasks involving complex reasoning such as prediction and sequencing. Note that some methods are not directly compared because they use different numbers of frames or additional benchmark tasks.

Full paper#