TL;DR#

Transformer models, while powerful, suffer from truncation errors in their discrete approximation of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs). High-order ODE solvers can improve accuracy but face challenges in training stability and efficiency. Previous work using gated fusion for coefficient learning in higher-order methods showed limited improvement when scaled to large datasets or models. This led to the need for improved Transformer architecture design and efficient learning techniques.

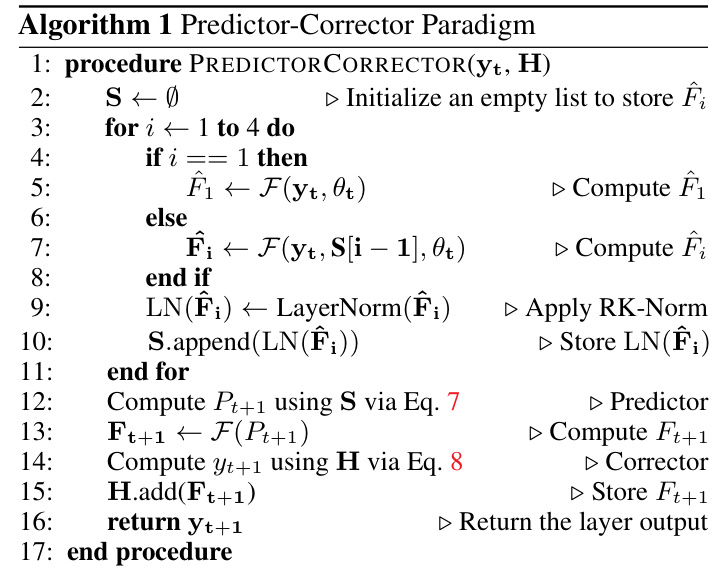

The paper introduces PCformer, a novel architecture that employs a predictor-corrector paradigm to minimize truncation errors. A key innovation is the use of exponential moving average (EMA) based coefficient learning, which enhances the higher-order predictor’s performance and stability. Extensive experiments demonstrate PCformer’s superiority over existing methods on various NLP tasks, achieving state-of-the-art results and showcasing better parameter efficiency. The EMA method also shows adaptability to different ODE solver orders, facilitating future exploration of even more advanced numerical methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on Transformer architecture and optimization. It offers a novel predictor-corrector framework that significantly improves accuracy and efficiency. The EMA coefficient learning is a significant contribution, paving the way for higher-order ODE methods in Transformers. This opens new avenues for enhancing the performance and parameter efficiency of large language models, a critical area of current research.

Visual Insights#

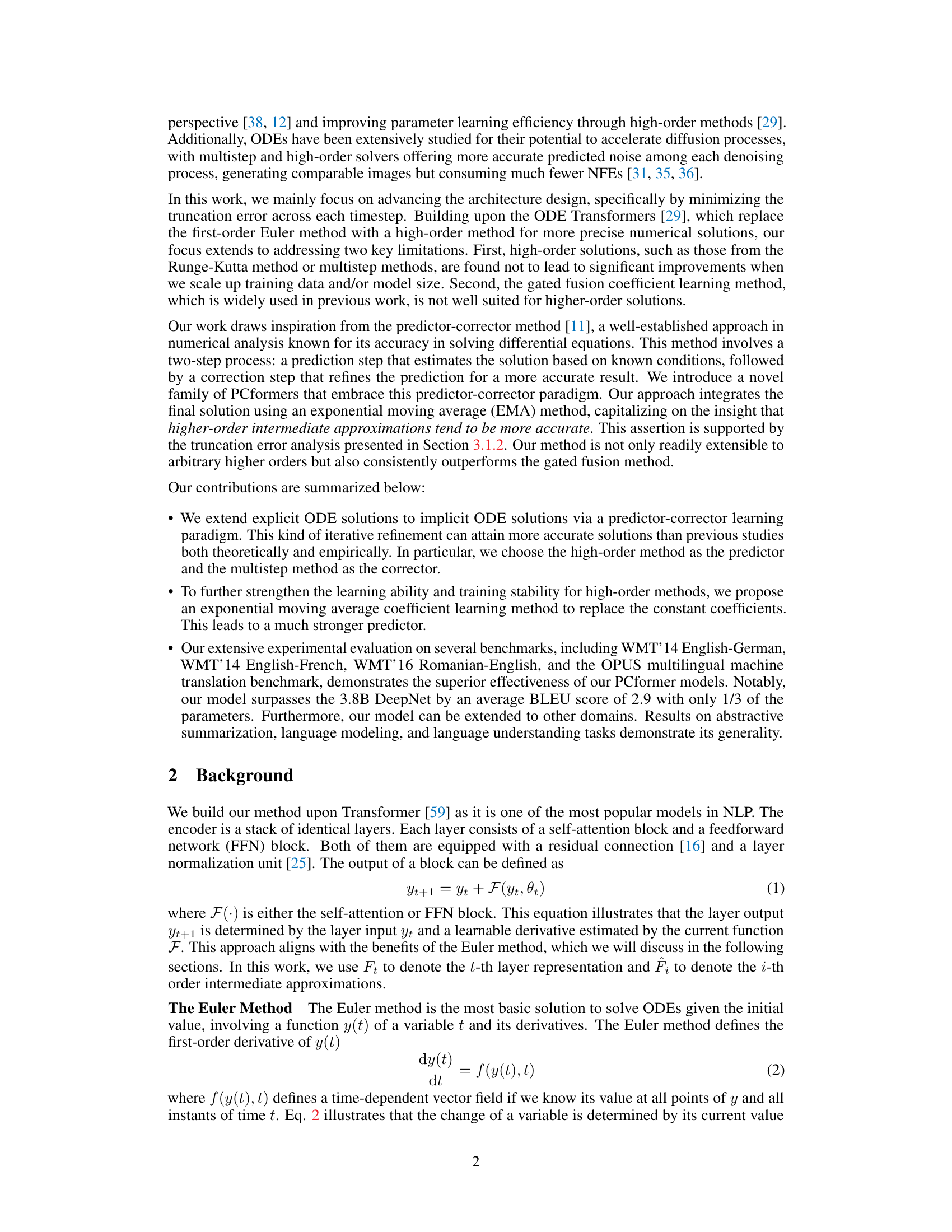

🔼 This figure illustrates different numerical methods for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which are analogous to the residual connections in neural networks. Panel (a) shows predictor-only paradigms: 1st-order 1-step (Euler method), 1st-order multi-step, and high-order 1-step methods. Panel (b) illustrates the proposed predictor-corrector paradigm, using a high-order predictor with exponential moving average (EMA) coefficient learning, followed by a multi-step corrector. This approach aims to improve accuracy by iteratively refining the solution.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of several advanced numerical methods and our proposed predictor-corrector paradigm. The right part plots a 4-order method as the predictor to obtain Pt+1; Ft+1 is then estimated via a function F(·); A 4-step method as the corrector to obtain the Yt+1.

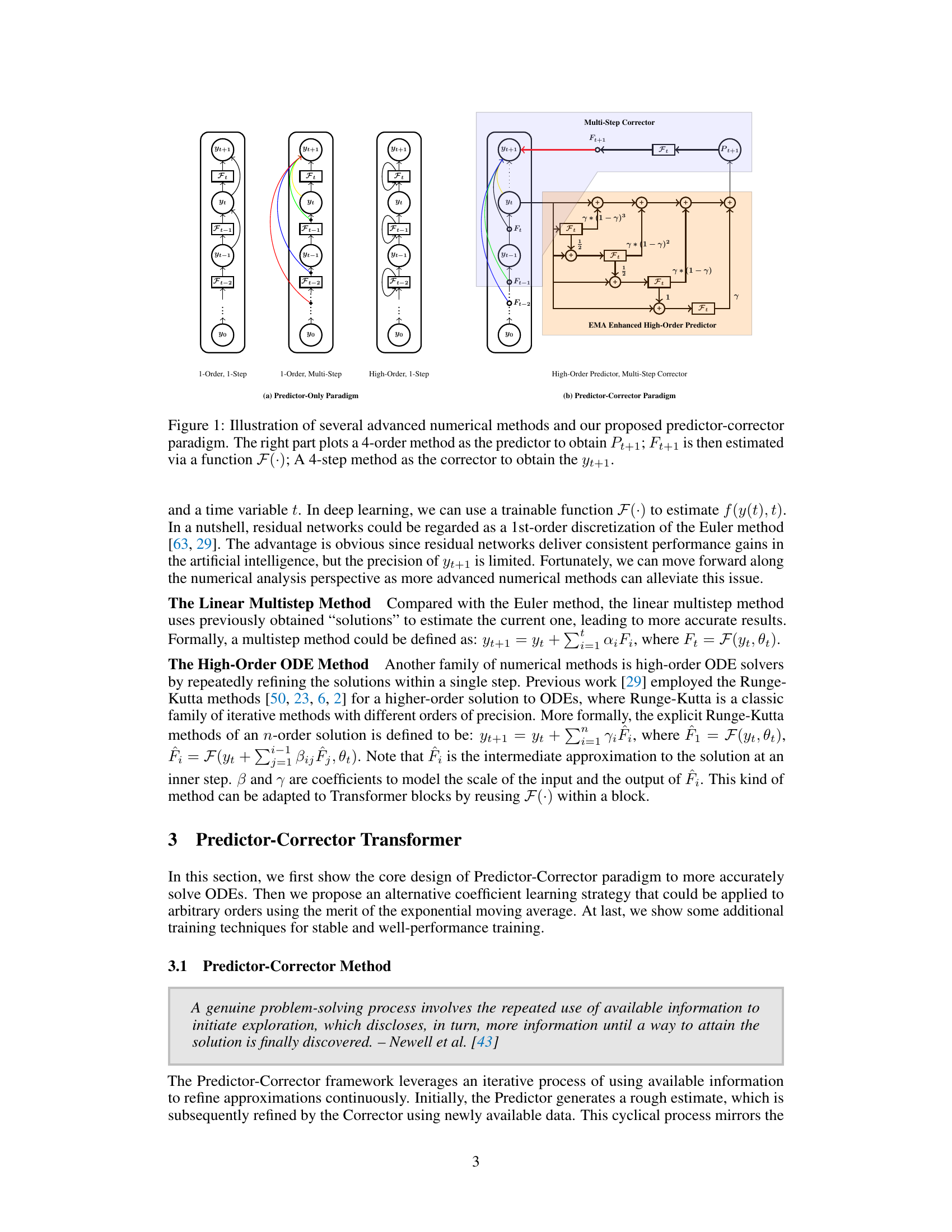

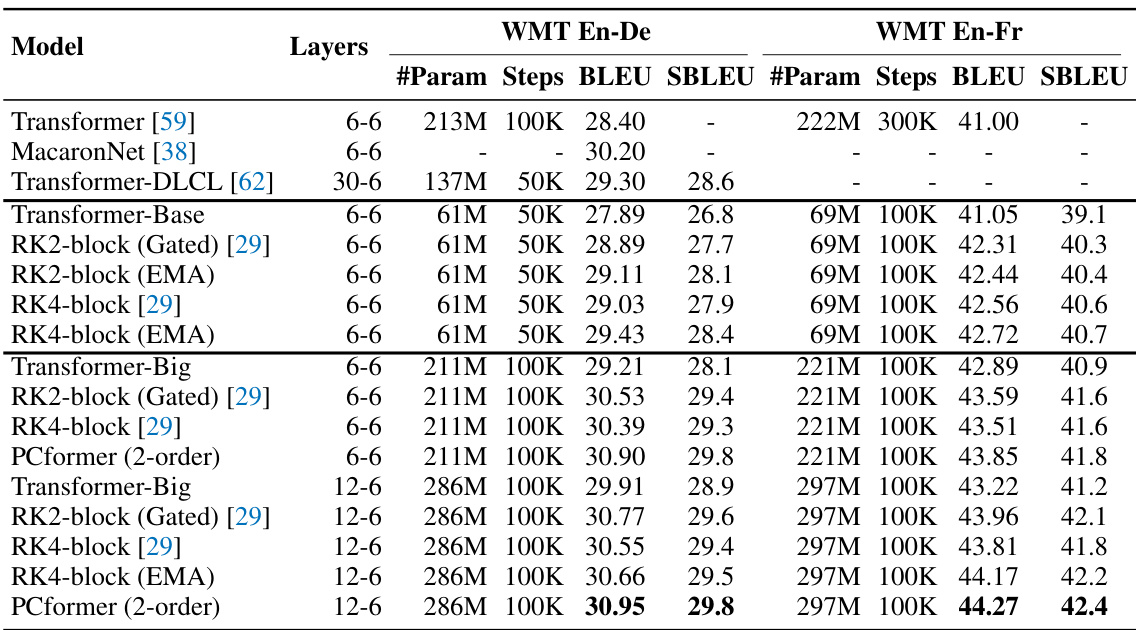

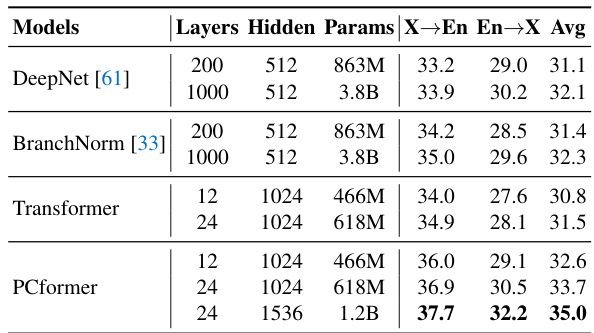

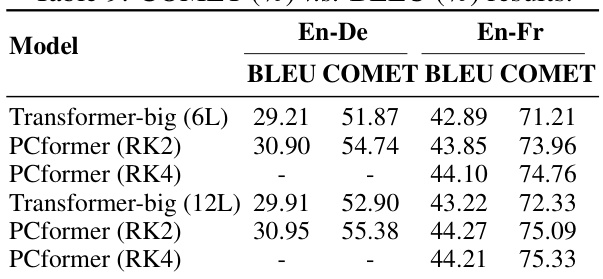

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PCformer model with several state-of-the-art models on the widely used machine translation benchmarks WMT'14 English-German and WMT'14 English-French. The results are presented in terms of BLEU and SacreBLEU scores, showing the superiority of PCformer in terms of accuracy while using fewer parameters.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-arts on the WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr tasks. We both report the tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores for comparison with previous work.

In-depth insights#

ODE Transformer#

The concept of “ODE Transformer” blends the power of neural ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with the efficiency and scalability of transformer networks. This approach views the layers of a standard transformer as discrete approximations of an ODE, providing a more continuous and potentially more expressive model. By solving the ODE directly, ODE Transformers aim to mitigate the limitations of traditional discrete-layer models such as vanishing/exploding gradients and the need for many layers. Key advantages include improved optimization and potentially better generalization, resulting in more accurate predictions. However, directly solving ODEs within the transformer architecture presents computational challenges, particularly with higher-order ODE solvers. The trade-off between accuracy and computational cost needs careful consideration. Different numerical methods to solve the underlying ODE are explored, with different order methods offering a trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. The choice of numerical solver significantly influences the performance of the model. Furthermore, efficient coefficient learning methods, such as exponential moving averages, are used to enhance learning and stability, particularly for high-order methods.

PC Learning#

PC learning, in the context of the provided research paper, likely refers to a predictor-corrector learning framework applied to enhance Transformer models. This method likely involves using a higher-order numerical method (like Runge-Kutta) as a predictor to generate an initial estimate of the next state in a sequence, followed by a multistep method (like Adams-Bashforth-Moulton) as a corrector to refine this prediction. The use of an exponential moving average (EMA) for coefficient learning is a crucial component, improving both the accuracy and stability of the higher-order predictor. This approach aims to minimize truncation errors inherent in discrete approximations of continuous processes, thereby improving model performance. The EMA-based coefficient learning likely adapts the weights assigned to past intermediate approximations, giving greater importance to more recent estimates. The overall effect should be more accurate and stable learning of Transformer parameters, resulting in improved performance on machine translation, text summarization, and other NLP tasks.

Empirical Results#

The empirical results section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made by the authors. A strong empirical results section will present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method across multiple datasets and benchmarks, comparing its performance against relevant baselines. Key aspects to look for include clear visualizations of results, such as graphs and tables, that are easy to interpret. Statistical significance should be reported using appropriate measures, such as p-values or confidence intervals, to demonstrate the reliability of the findings. The results should also be discussed in detail, explaining any unexpected findings or limitations. A thoughtful analysis of the results, especially concerning potential biases or confounding factors, is needed. Finally, a well-written empirical results section should draw clear conclusions about the effectiveness of the proposed method and its suitability for different applications.

Future Work#

The authors acknowledge that while their proposed Predictor-Corrector enhanced Transformers show significant improvements, there’s room for further advancements. Accelerating inference, especially for encoder-only and decoder-only models, is a key area for future work, as the current method’s computational overhead remains concentrated in the decoder. They plan to investigate performing high-order computations in a reduced-dimensionality latent space to improve efficiency or exploring the possibility of achieving high-order training and inference using a first-order approach. Exploring different ODE solvers and integrating other numerical methods beyond Adams-Bashforth-Moulton could further refine the approach’s accuracy and stability. Finally, extending the methodology to other domains, beyond machine translation, summarization, language modeling, and understanding, presents exciting opportunities to explore the broad applicability and potential of this enhanced Transformer architecture.

Limitations#

The research, while demonstrating significant advancements in Transformer architecture through a novel predictor-corrector framework and EMA coefficient learning, acknowledges limitations. Scalability to larger models remains a challenge, particularly concerning inference speed, especially for encoder-decoder models. The efficiency gains might not be as pronounced in solely encoder or decoder-only model applications. The study focuses mainly on machine translation, limiting the generalizability to other NLP tasks. Further investigation is needed into optimizing high-order computations, especially when handling long sequences. While the EMA approach enhances high-order model training stability, its optimal parameter settings may vary depending on the dataset and model size, requiring further exploration. Finally, the impact of the predictor-corrector paradigm on other areas of NLP, beyond machine translation, needs deeper investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

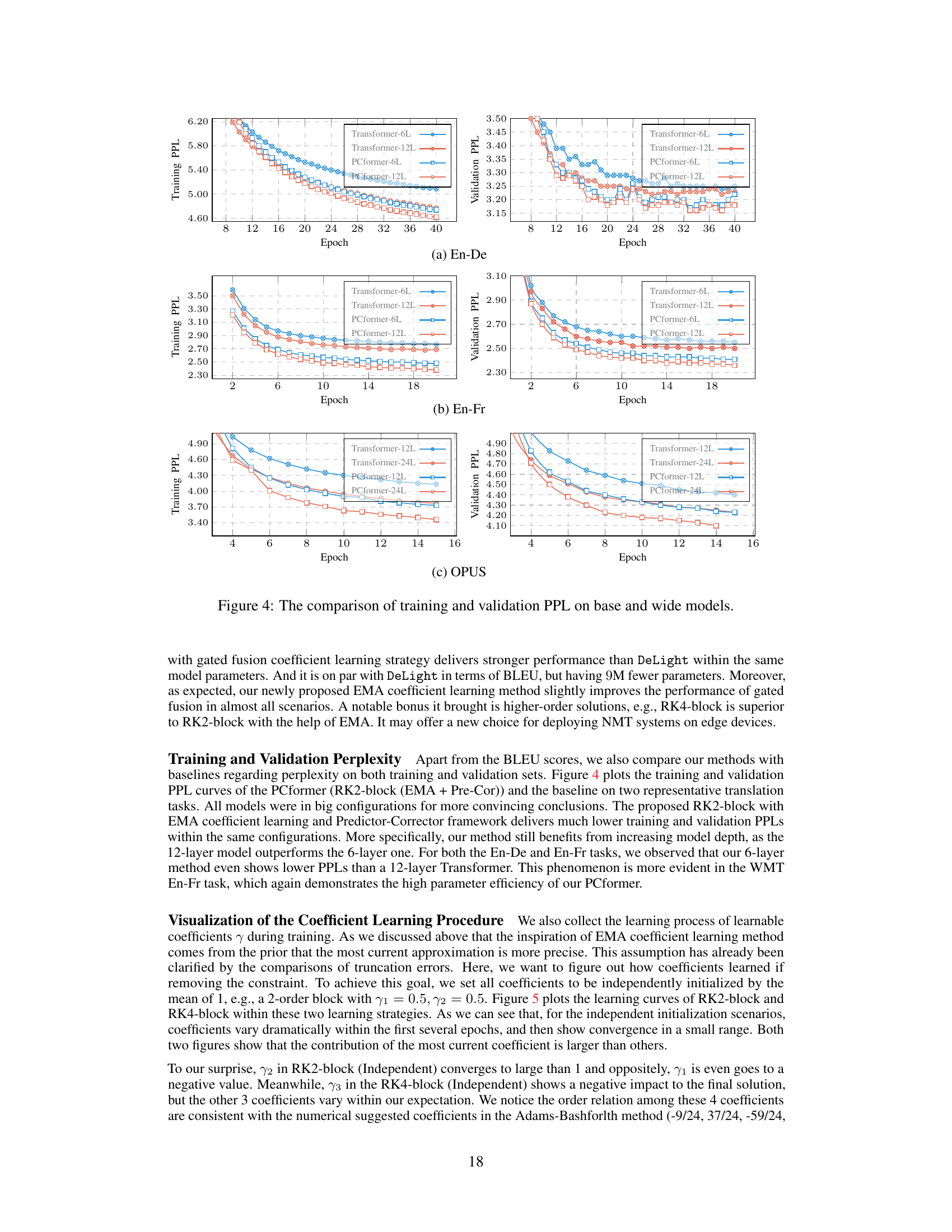

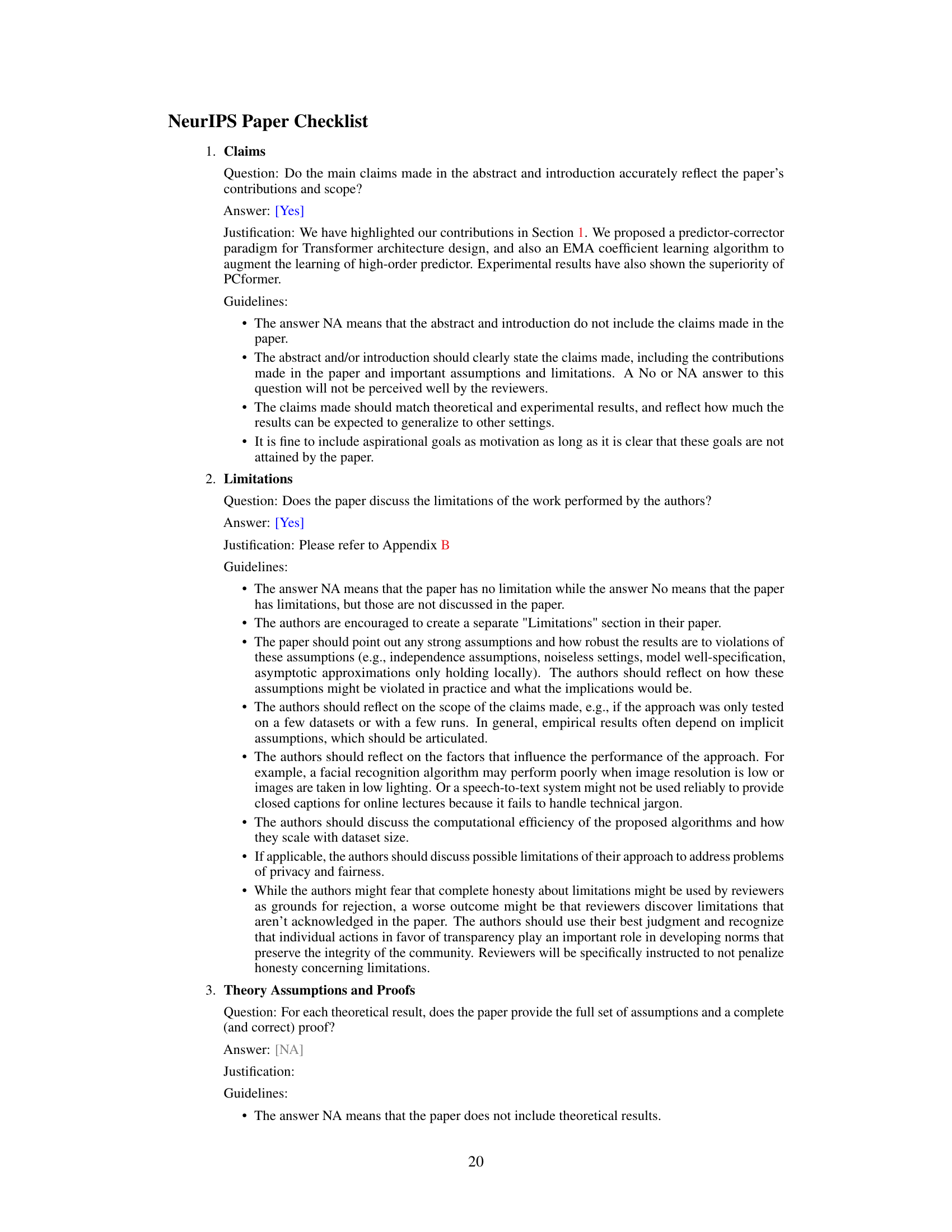

🔼 This figure compares the perplexity (a measure of how well a model predicts text) achieved using different approximation methods for the 4th-order approximation within the predictor-corrector framework. Lower perplexity indicates fewer truncation errors, and therefore, a more accurate solution. The results show that the 4th-order approximation performs comparably well and outperforms other methods such as a vanilla approach, Runge-Kutta (RK4), and lower-order approximations (1st, 2nd, 3rd). This supports the paper’s claim that high-order predictors improve accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 2: Truncation errors with different intermediate approximations.

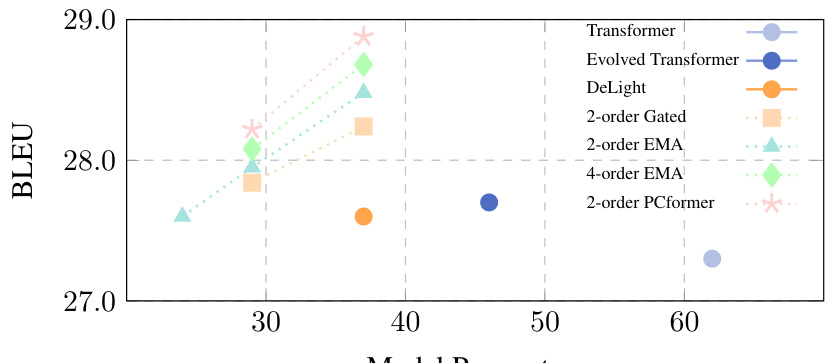

🔼 This figure compares the BLEU scores achieved by various Transformer models, including the vanilla Transformer, Evolved Transformer, DeLight, and different variants of the PCformer model (with gated fusion, EMA, and predictor-corrector approaches). It highlights the model parameter size and the training cost (in terms of steps) required to achieve these scores. The results illustrate the efficiency and improved performance of the PCformer models compared to the baselines.

read the caption

Figure 3: The comparison of BLEU as well as model capacities and training costs against previous state-of-the-art deep transformers.

🔼 This figure illustrates different numerical methods for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which are analogous to the layer-wise computations in neural networks. It compares three predictor-only approaches (Euler, multi-step, and high-order methods) with the proposed predictor-corrector method. The predictor-corrector approach uses a high-order method for prediction and a multi-step method for correction, improving accuracy. The figure highlights the key components and flow of the predictor-corrector framework.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of several advanced numerical methods and our proposed predictor-corrector paradigm. The right part plots a 4-order method as the predictor to obtain Pt+1; Ft+1 is then estimated via a function F(·); A 4-step method as the corrector to obtain the Yt+1.

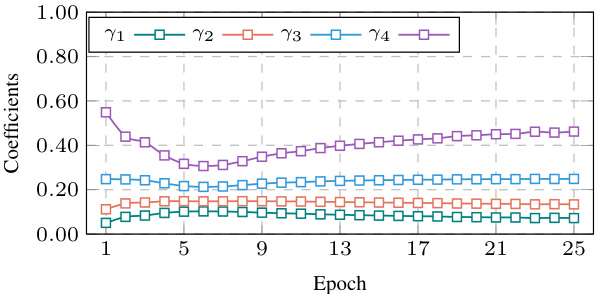

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves of the learnable coefficients (γ1, γ2, γ3, γ4) in both 2-order and 4-order Runge-Kutta methods with two different coefficient learning strategies: independent initialization and exponential moving average (EMA). The independent initialization strategy allows the coefficients to learn independently, while the EMA strategy assigns exponentially decaying weights to previous approximations, giving more importance to recent data. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the value of the coefficients. The results show that the EMA strategy leads to more stable and well-behaved coefficient learning, while the independent initialization leads to more erratic behavior, with some coefficients even becoming negative. These results support the authors’ claim that EMA-based coefficient learning is more effective for high-order methods.

read the caption

Figure 5: The coefficient learning curves of independent initialization and EMA in both 2-order and 4-order scenarios. The experiments are conducted on WMT En-De.

🔼 This figure visualizes the learning process of learnable coefficients (γ) during training for both 2-order and 4-order scenarios using two different coefficient learning strategies: independent initialization and exponential moving average (EMA). The independent initialization strategy allows coefficients to be independently initialized, while the EMA strategy assigns larger weights to more recent approximations. The plots show how these coefficients evolve over epochs (training iterations) for the WMT English-German translation task. The results demonstrate that the EMA strategy leads to a more stable and predictable coefficient learning process compared to independent initialization, resulting in improved translation performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: The coefficient learning curves of independent initialization and EMA in both 2-order and 4-order scenarios. The experiments are conducted on WMT En-De.

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves of the learnable coefficients (γ) in the EMA method for both 2nd-order and 4th-order models during training on the WMT English-German translation task. It compares two scenarios: (1) independent initialization, where each coefficient is initialized independently, and (2) EMA-based initialization, where the coefficients are initialized using an exponential moving average. The plot shows how these coefficients evolve over epochs, illustrating the impact of the different initialization strategies. The results support the claim that the EMA initialization leads to better coefficient learning and thus improves model performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: The coefficient learning curves of independent initialization and EMA in both 2-order and 4-order scenarios. The experiments are conducted on WMT En-De.

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves of the learnable coefficients γ in the EMA coefficient learning method for both 2-order and 4-order scenarios. The independent initialization setting allows the coefficients to be independently initialized, while the EMA method uses an exponential moving average to update the coefficients. The experiments were conducted on the WMT En-De dataset, and the results show that the EMA method leads to more stable and consistent coefficient learning curves than the independent initialization setting.

read the caption

Figure 5: The coefficient learning curves of independent initialization and EMA in both 2-order and 4-order scenarios. The experiments are conducted on WMT En-De.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PCformer model with several state-of-the-art models on the widely used machine translation benchmarks, WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr. The results are presented in terms of both tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance compared to existing approaches. The table includes various model configurations, layer numbers, and parameter counts, offering insights into the relationship between model architecture and translation quality.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-arts on the WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr tasks. We both report the tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores for comparison with previous work.

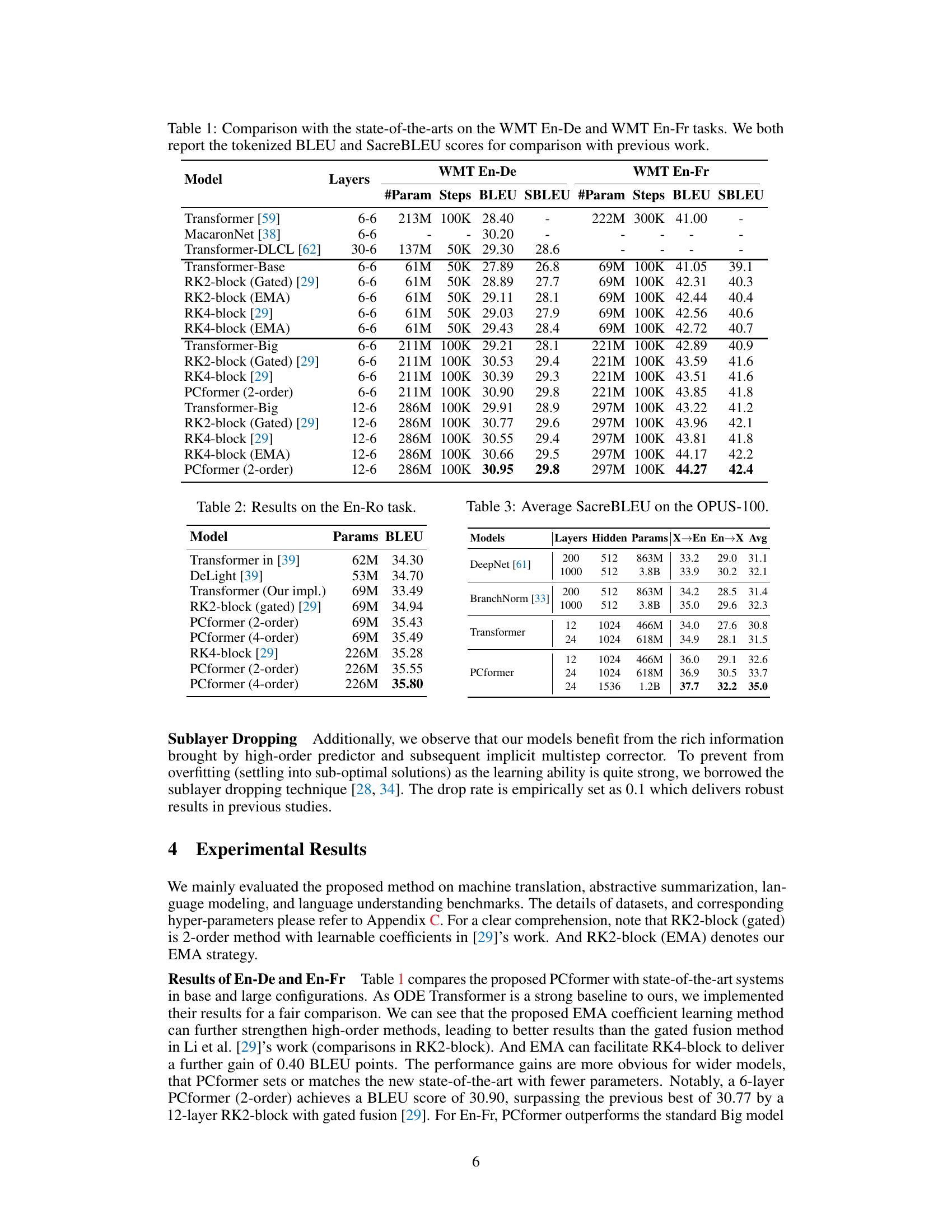

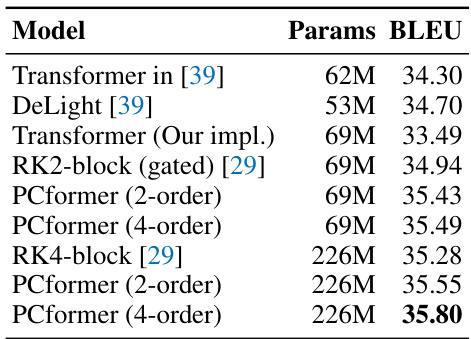

🔼 This table presents the results of the English-Romanian (En-Ro) machine translation task. It compares the performance of various models, including different versions of the PCformer model (with varying numbers of parameters and orders), against baseline Transformer and other related models (RK2-block (gated), RK4-block). The metric used for evaluation is BLEU score.

read the caption

Table 2: Results on the En-Ro task.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the PCformer model’s performance against other state-of-the-art models on the OPUS-100 multilingual machine translation benchmark. It shows the average SacreBLEU scores for translation in both directions (English to other languages, and other languages to English) for various model sizes and architectures, highlighting the improved performance of the PCformer model.

read the caption

Table 3: Average SacreBLEU on the OPUS-100.

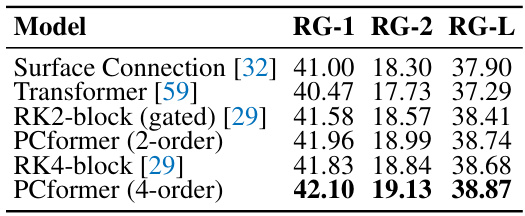

🔼 This table presents the results of the abstractive summarization task on the CNN/DailyMail dataset. It compares the performance of several models, including Surface Connection, the standard Transformer, RK2-block (gated), PCformer (2-order), RK4-block, and PCformer (4-order), in terms of ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores. The results show that PCformer consistently outperforms other baselines, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed predictor-corrector approach in this task as well.

read the caption

Table 4: ROUGE results on CNN/DailyMail summarization dataset.

🔼 This table presents the perplexity results on the Wikitext-103 benchmark for various language models, including Adaptive Input Transformer, RK2-block (gated), and PCformer (2-order). It compares the perplexity scores achieved by these models on both the validation and test sets, highlighting the performance of PCformer in achieving lower perplexity scores.

read the caption

Table 5: Perplexity results on Wikitext-103. Adaptive refers to Adaptive Input Transformer [3].

🔼 This table compares the performance of PCformer against Transformer++ on various configurations, using different sizes of the SlimPajama dataset and the Mistral tokenizer. The results are evaluated across multiple downstream tasks, with the final column representing the average normalized accuracy across all tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: PCformer results against Transformer++ [58] on various configurations. All models are trained on the same subset of the SlimPajama dataset (from 6B to 100B) with the Mistral tokenizer [21]. The last column shows the average over all benchmarks that use (normalized) accuracy as the metric.

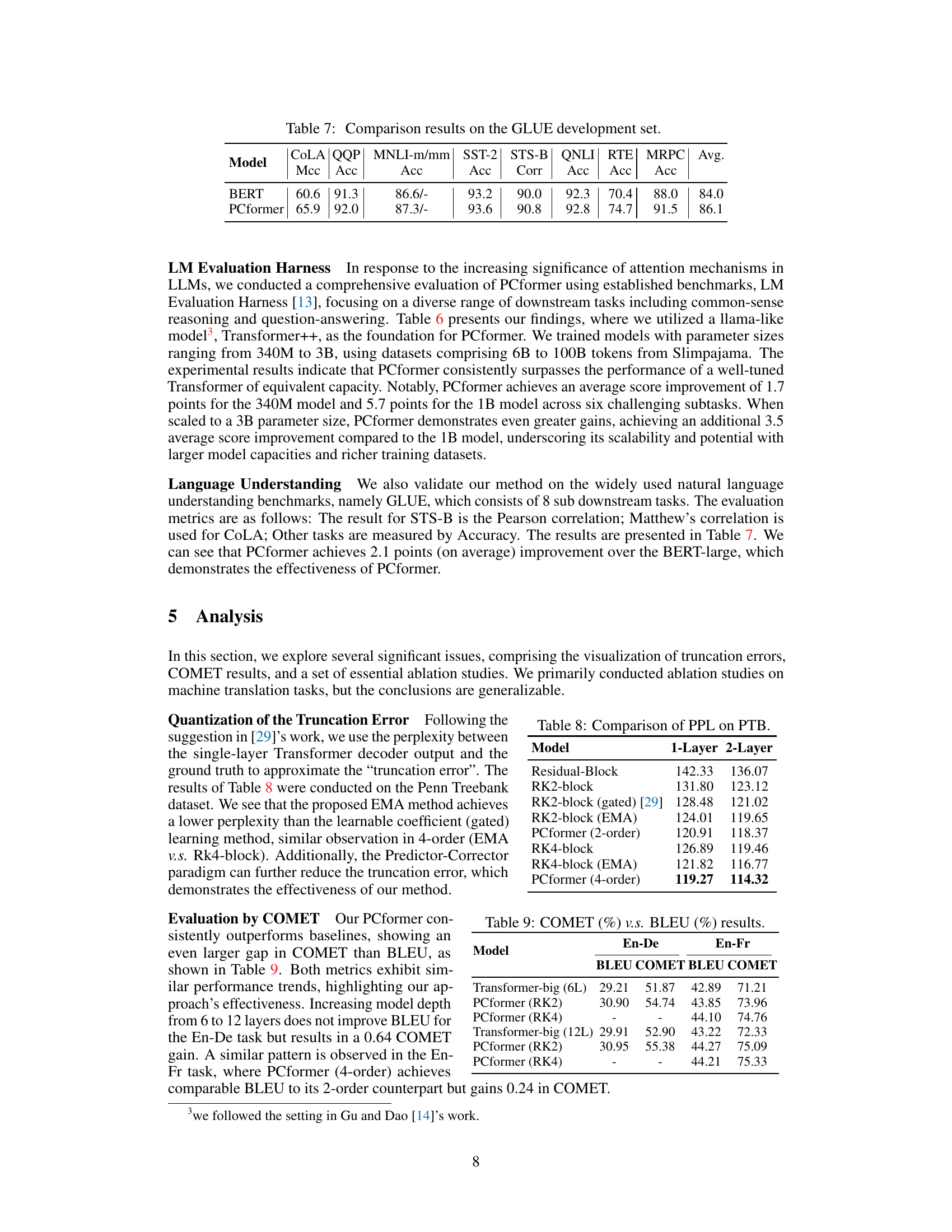

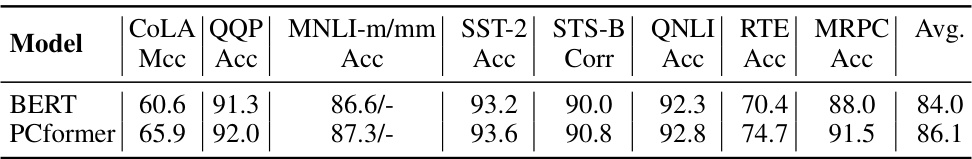

🔼 This table presents the comparison results on the GLUE benchmark’s development set between the BERT model and the proposed PCformer model. The GLUE benchmark comprises eight sub-tasks assessing various aspects of natural language understanding. The table shows the performance of each model on each sub-task, using metrics appropriate to the sub-task (e.g., accuracy, Matthews correlation coefficient, Pearson correlation). The average score across all sub-tasks is also provided. This comparison highlights the improvement in language understanding capabilities achieved by the PCformer model compared to the BERT model.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison results on the GLUE development set. COLA QQP MNLI-m/mm SST-2 STS-B QNLI RTE MRPC Avg. Mcc Acc Acc Acc Corr Acc Acc Acc

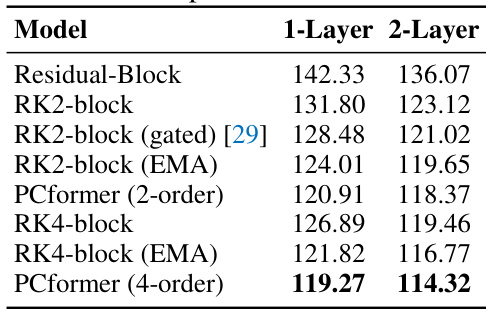

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) results on the Penn Treebank (PTB) dataset for various models, including different versions of the RK-block and PCformer. It demonstrates the reduction in PPL achieved by incorporating the exponential moving average (EMA) based coefficient learning and the predictor-corrector framework. The results are shown separately for 1-layer and 2-layer models.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison of PPL on PTB.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PCformer model against other state-of-the-art models on the WMT'14 English-German and English-French machine translation tasks. It shows the number of layers, number of parameters, number of training steps, BLEU scores, and SacreBLEU scores for each model.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-arts on the WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr tasks. We both report the tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores for comparison with previous work.

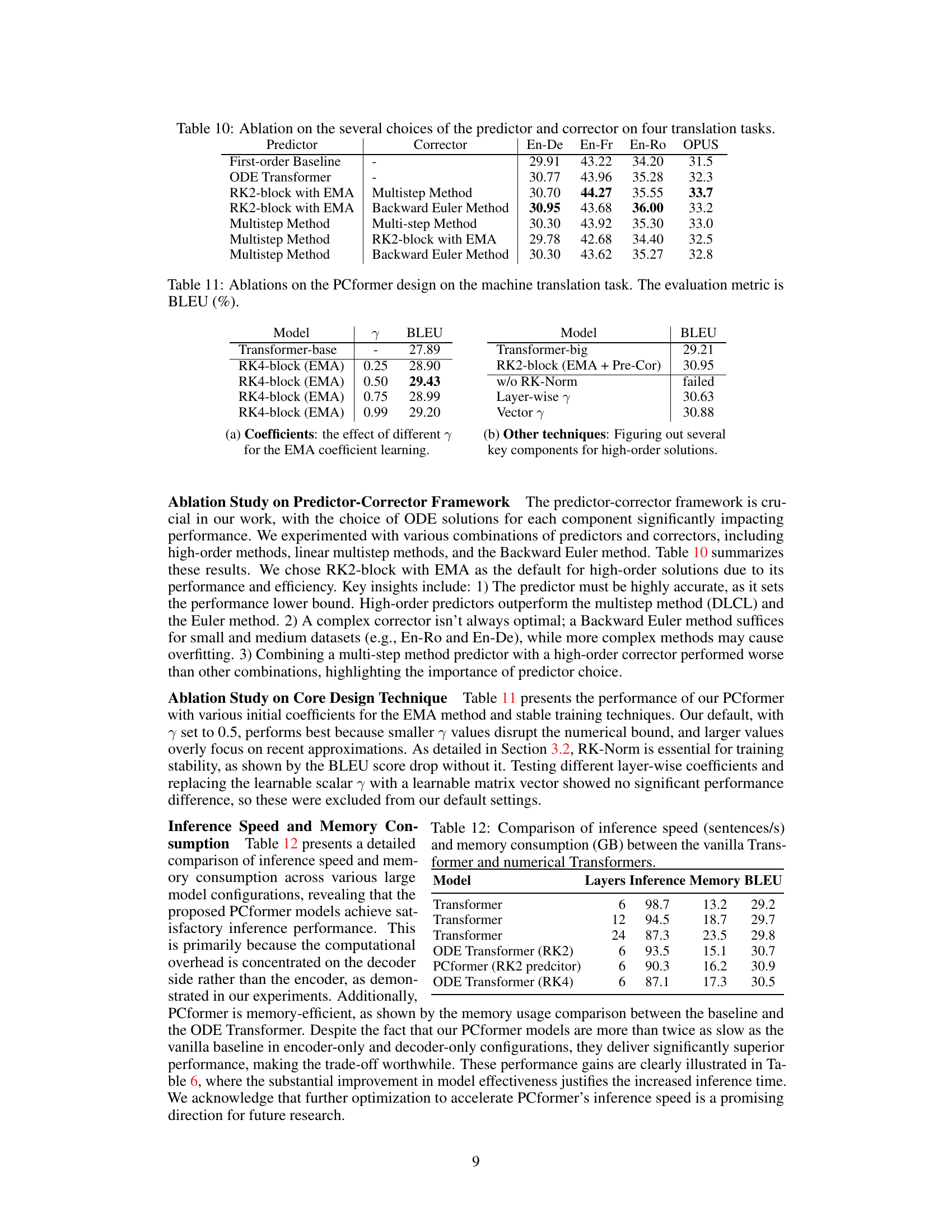

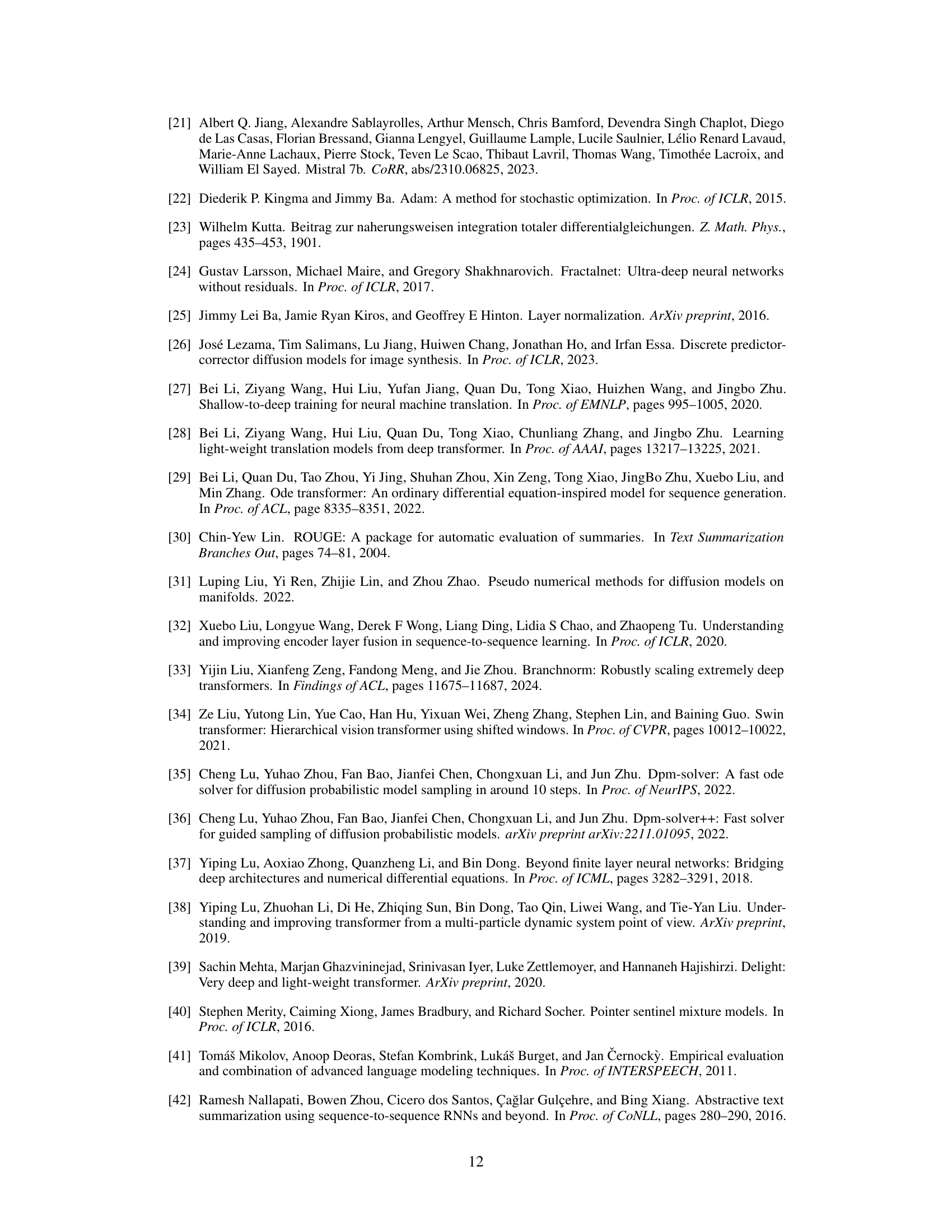

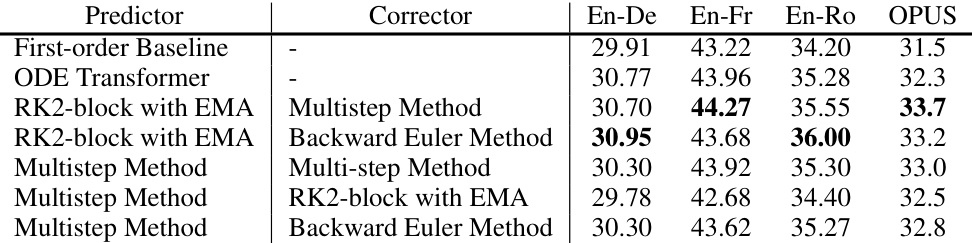

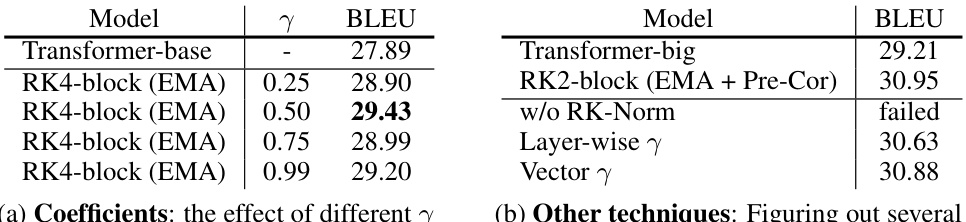

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the predictor-corrector framework. It shows the BLEU scores achieved by different combinations of predictors (First-order Baseline, ODE Transformer, RK2-block with EMA, Multistep Method) and correctors (Multistep Method, Backward Euler Method) on four machine translation tasks (En-De, En-Fr, En-Ro, OPUS). The results demonstrate the impact of the choice of predictor and corrector on the overall performance.

read the caption

Table 10: Ablation on the several choices of the predictor and corrector on four translation tasks.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PCformer model with other state-of-the-art models on the WMT English-German and English-French machine translation tasks. It shows the number of layers, the number of parameters, the number of training steps, the BLEU score, and the SacreBLEU score for each model. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the PCformer model, especially when using a larger model size.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-arts on the WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr tasks. We both report the tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores for comparison with previous work.

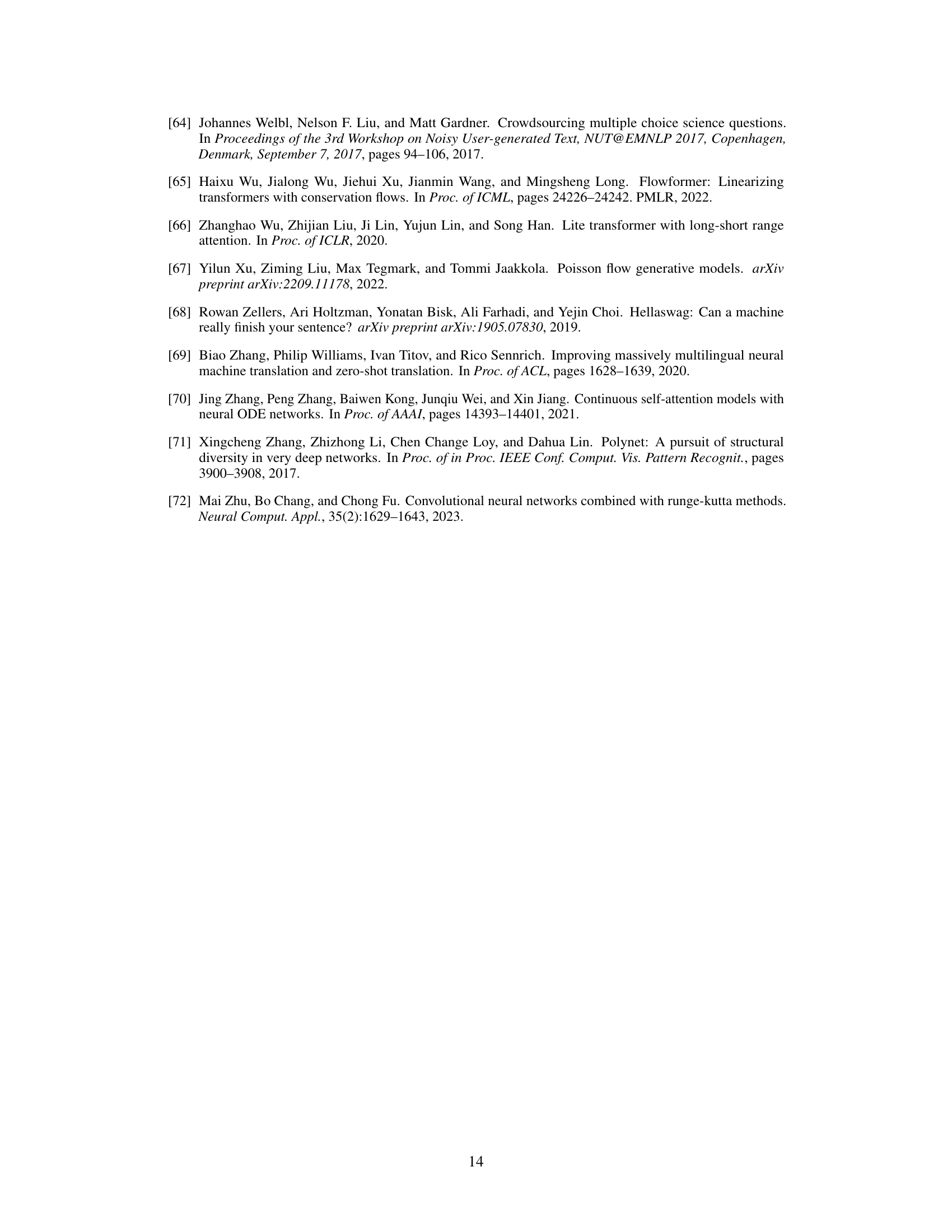

🔼 This table compares the inference speed and memory consumption of vanilla Transformers and numerical Transformers (ODE Transformer and PCformer) with varying numbers of layers. It shows that while the numerical methods are slower, they achieve comparable or better BLEU scores with less memory usage.

read the caption

Table 12: Comparison of inference speed (sentences/s) and memory consumption (GB) between the vanilla Transformer and numerical Transformers.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PCformer model with various state-of-the-art models on the WMT English-German and English-French machine translation tasks. The table shows the number of layers, number of parameters, number of training steps, BLEU scores, and SacreBLEU scores for each model. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the PCformer model compared to other models.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-arts on the WMT En-De and WMT En-Fr tasks. We both report the tokenized BLEU and SacreBLEU scores for comparison with previous work.

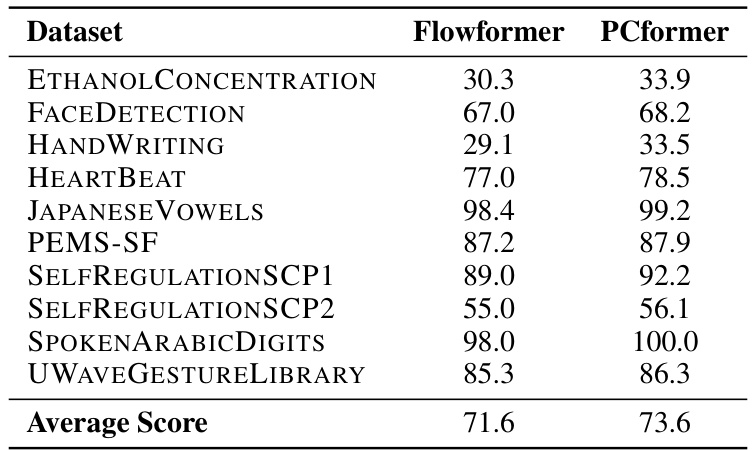

🔼 This table compares the performance of the PCformer model against the Flowformer model on ten different time-series forecasting datasets. The datasets cover various domains, including ethanol concentration, face detection, handwriting, heartbeat, Japanese vowels, traffic flow (PEMS-SF), self-regulation, spoken Arabic digits, and UWAVE gesture library. For each dataset, the table shows the average score achieved by each model. The average score across all ten datasets is also provided, indicating an overall improvement in performance for the PCformer model.

read the caption

Table 14: Comparison of Flowformer and PCformer on different datasets.

Full paper#