↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current language model (LM) alignment methods heavily rely on resource-intensive human feedback, such as preference labels or demonstrations. This makes it challenging to instill desired behavioral principles (constitutions) into LMs. This paper addresses this issue by introducing a novel self-supervised alignment technique.

The proposed method, SAMI (Self-Supervised Alignment with Mutual Information), iteratively finetunes a pretrained LM to increase the mutual information between self-generated responses and the provided principles, effectively aligning the model’s behavior without any human oversight. Experiments on dialogue and summarization tasks show that SAMI outperforms baselines, even surpassing instruction-finetuned models, proving its effectiveness and scalability. These findings offer a significant advancement in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on language model alignment as it introduces a novel approach to instill principles into LMs without relying on human preference labels or demonstrations. This significantly reduces the resource-intensive nature of current methods and opens up new avenues for research in this vital area. It also demonstrates the potential of self-supervised alignment and its scalability to state-of-the-art models.

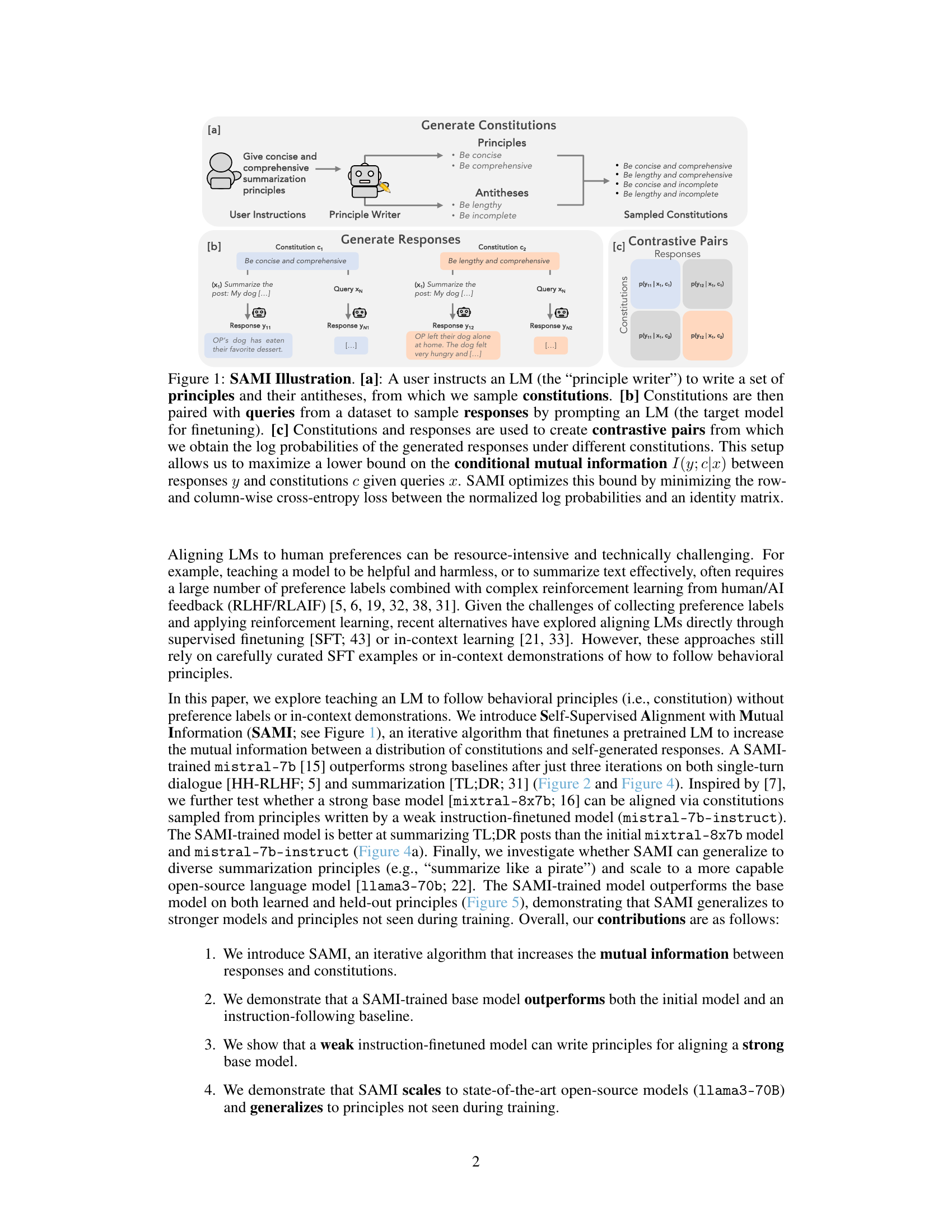

Visual Insights#

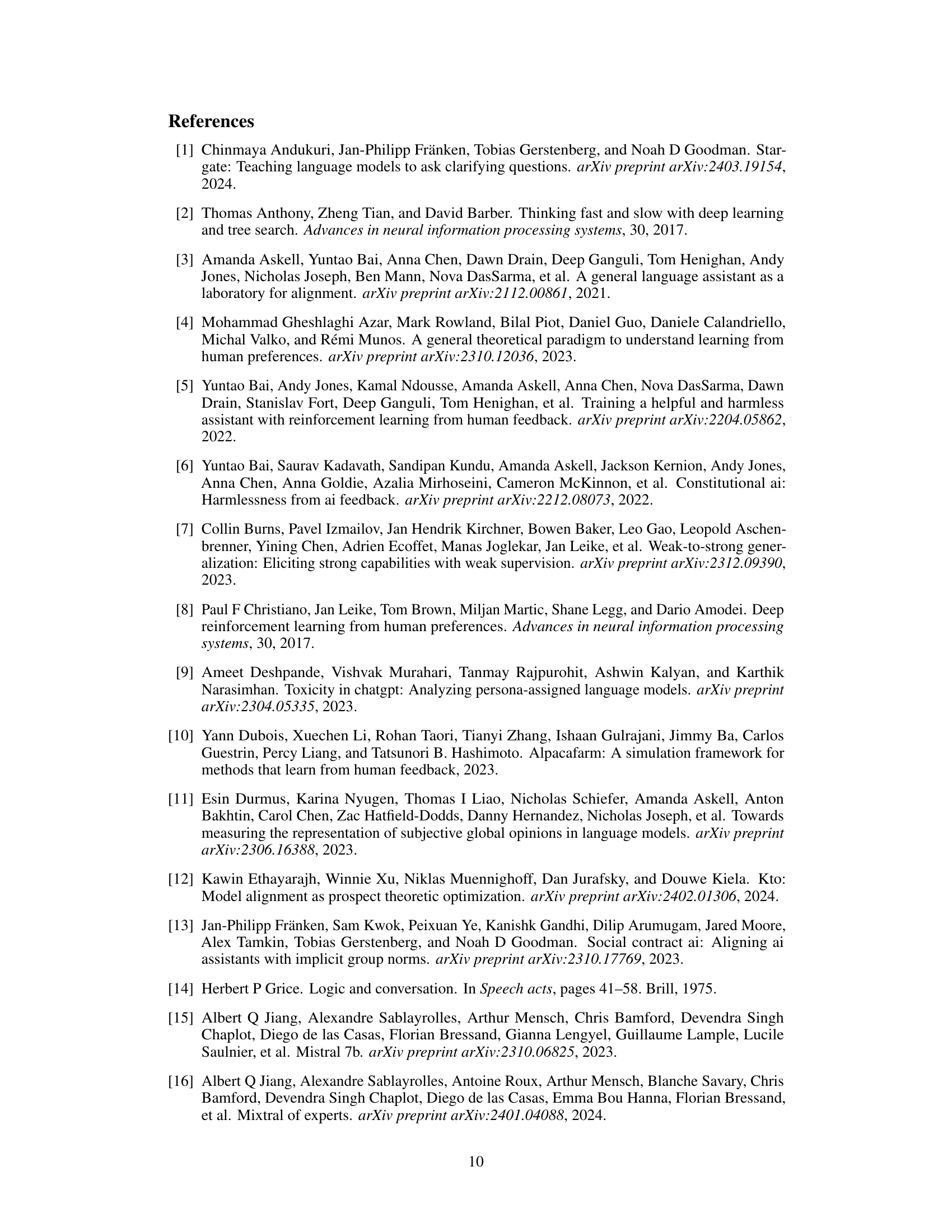

🔼 This figure illustrates the SAMI (Self-Supervised Alignment with Mutual Information) algorithm. Panel (a) shows how user instructions are given to a language model (LM) to generate principles and their antitheses. These are then sampled to form constitutions, which are sets of guidelines for the LM’s behavior. Panel (b) demonstrates how these constitutions and queries from a dataset are used to generate responses from a target LM. Panel (c) details the creation of contrastive pairs from these constitutions and responses, enabling the calculation of log probabilities used to optimize a lower bound on the conditional mutual information. This optimization involves minimizing the cross-entropy loss between the normalized log probabilities and an identity matrix to align the LM’s responses with the given constitutions.

read the caption

Figure 1: SAMI Illustration. [a]: A user instructs an LM (the “principle writer”) to write a set of principles and their antitheses, from which we sample constitutions. [b] Constitutions are then paired with queries from a dataset to sample responses by prompting an LM (the target model for finetuning). [c] Constitutions and responses are used to create contrastive pairs from which we obtain the log probabilities of the generated responses under different constitutions. This setup allows us to maximize a lower bound on the conditional mutual information I(y; c|x) between responses y and constitutions c given queries x. SAMI optimizes this bound by minimizing the row- and column-wise cross-entropy loss between the normalized log probabilities and an identity matrix.

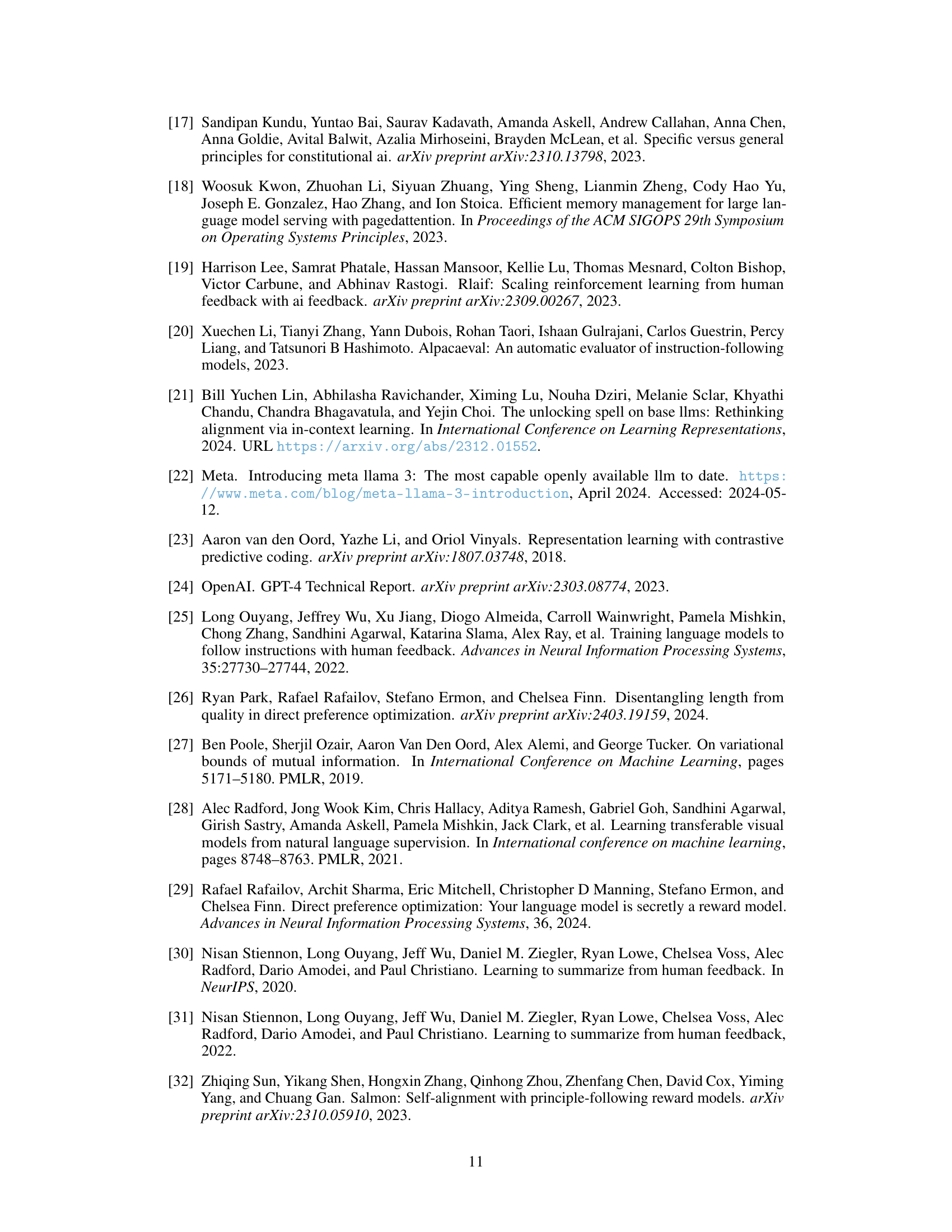

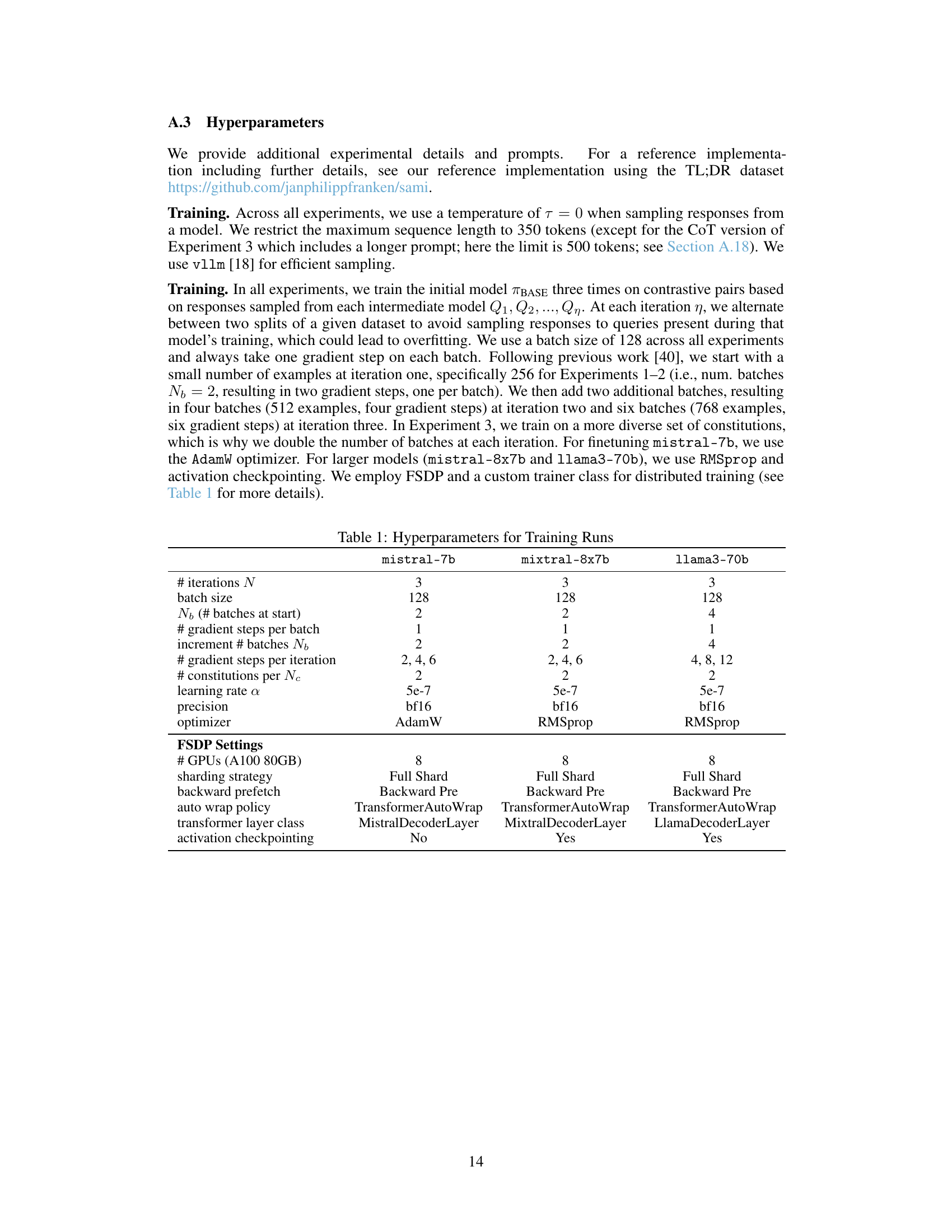

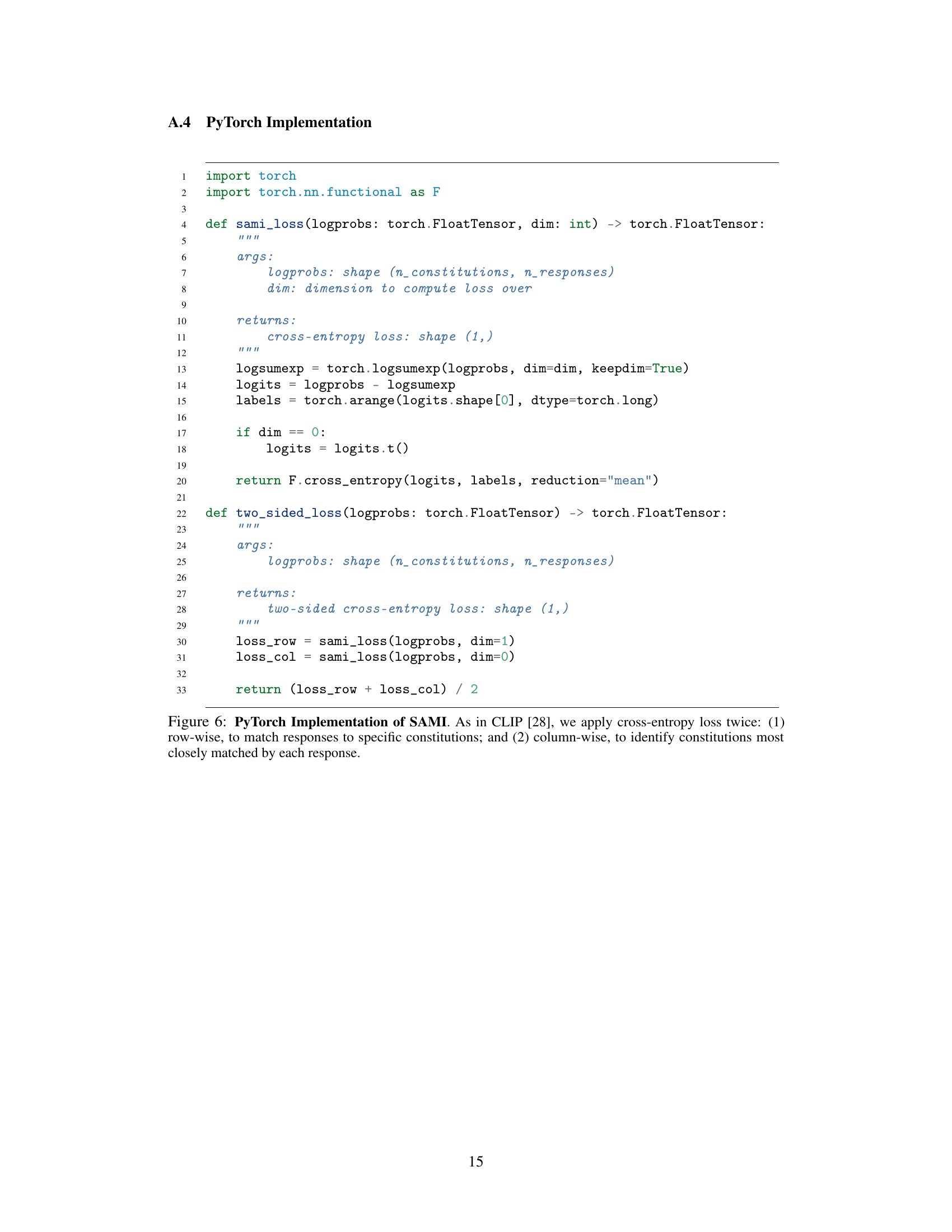

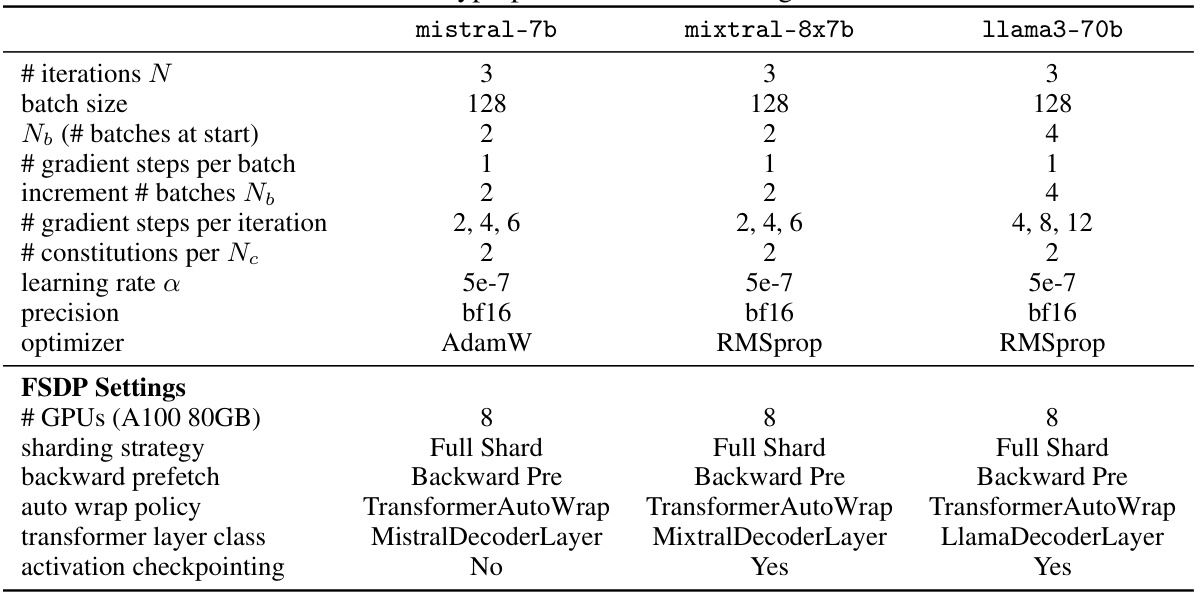

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for training the different language models (mistral-7b, mixtral-8x7b, and llama3-70b) in the SAMI experiments. It details the number of iterations, batch size, initial number of batches, number of gradient steps per batch, how the number of batches increases per iteration, total number of gradient steps per iteration, number of constitutions per query, learning rate, precision, and optimizer used for each model. Additionally, it specifies the FSDP settings including the number of GPUs, sharding strategy, backward prefetch settings, auto wrap policy, transformer layer class, and whether activation checkpointing was used.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameters for Training Runs

In-depth insights#

Self-Supervised Alignment#

Self-supervised alignment presents a novel approach to aligning language models (LMs) with human values and preferences without relying on human-labeled data. This method leverages the inherent statistical connections already present within pretrained LMs, aiming to strengthen the relationship between provided principles (a constitution) and model-generated responses. The core idea is to maximize the mutual information between the constitution and the model’s outputs, given a specific query. This approach is particularly interesting because it bypasses the resource-intensive and often challenging process of collecting human preference labels, a common bottleneck in traditional alignment techniques. The self-supervised nature is key, as the model learns to align with the provided principles through iterative self-training, effectively learning from its own mistakes and generating increasingly aligned outputs. The success of this method is promising for the efficient and scalable alignment of advanced LMs, hinting at the potential of uncovering and exploiting latent knowledge already embedded in pretrained models.

Mutual Info Learning#

Mutual information learning, in the context of aligning large language models (LLMs), offers a novel approach to imbuing models with desired behaviors without relying on human-provided preference labels or demonstrations. The core idea is to maximize the mutual information between a model’s generated responses and a set of principles or guidelines (a ‘constitution’), given a specific input prompt. This approach leverages the inherent statistical connections between language and behavior already present in pre-trained LLMs. By aligning the model’s output to the constitution, the method subtly steers the model towards desirable behaviors, effectively aligning it without explicit instruction. The absence of preference data makes this a more scalable and efficient method compared to traditional reinforcement learning techniques, opening possibilities for broader application in aligning LLMs with diverse values and ethical considerations. A key advantage lies in its potential for generalization to unseen principles, meaning the model may exhibit desirable behavior even with principles not encountered during training. However, challenges remain in managing over-optimization and ensuring robustness.

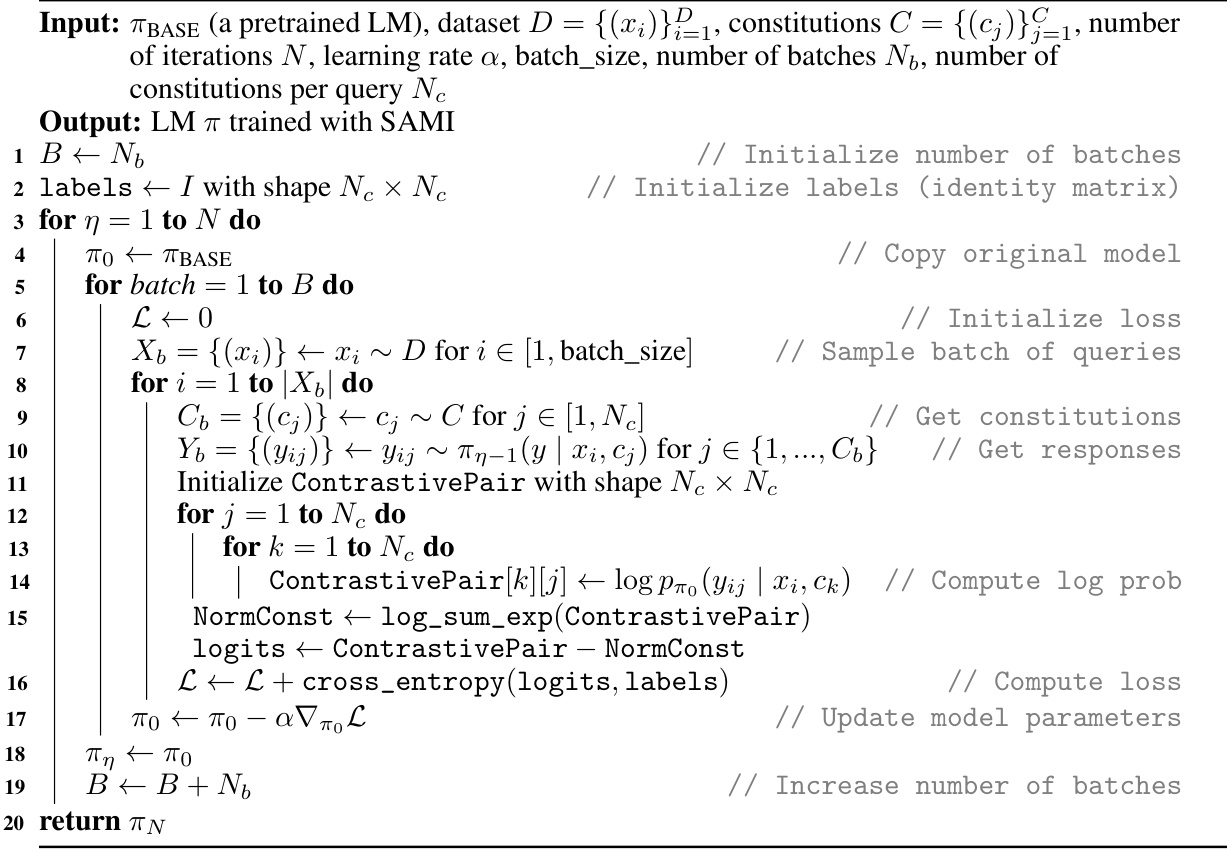

SAMI Algorithm#

The SAMI algorithm is a self-supervised approach for aligning pretrained language models with desired behavioral principles, or a constitution, without the need for human preference labels or demonstrations. It leverages contrastive learning by maximizing the conditional mutual information between the model’s generated responses and the provided constitution, given a query. The iterative process involves generating response pairs using the current model, comparing their likelihood under different constitutions, and fine-tuning the model to align more closely with the preferred constitution. This clever technique effectively guides the model towards exhibiting desired behaviors by implicitly strengthening the underlying statistical connection between principles and outputs already present in the pretrained weights, rather than explicitly providing labeled examples. A key advantage is its ability to adapt to stronger models and a broader range of principles without additional training data. The core of SAMI lies in its innovative use of mutual information as an objective function, which enables alignment without explicit reward shaping, making it a significant advance in self-supervised alignment techniques.

Model Alignment#

Model alignment, the process of aligning AI behavior with human values and intentions, is a critical challenge in the field. The paper explores this problem by introducing a novel method that leverages self-supervised learning and mutual information to align language models (LMs) with behavioral principles, or a “constitution.” The key innovation is the avoidance of human preference labels or demonstrations, which are typically resource-intensive and difficult to obtain. Instead, the proposed technique aims to directly increase the mutual information between the constitution and the model’s generated responses. This approach is intriguing because it suggests that pretrained LMs might already possess a latent connection between principles and behavior, a connection that can be amplified through the proposed technique. The empirical results are encouraging, showing that the method effectively improves the model’s alignment with the constitution, surpassing instruction-finetuned baselines and demonstrating scalability to larger models. However, limitations remain, such as the reliance on strong principle-writing models and the potential for over-optimization. Future work should address these limitations and expand the evaluation to more diverse tasks and constitutions.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore applying this method to a wider range of tasks and models, evaluating its performance on more complex reasoning tasks and longer sequences. Investigating the impact of different principle sets and exploring techniques for automatic principle generation would be valuable. The influence of model architecture and pretraining on SAMI’s effectiveness warrants further study, as does the potential for combining SAMI with other alignment techniques. Finally, a thorough investigation into the generalizability and robustness of SAMI across diverse datasets and domains is crucial for establishing its practical value in real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

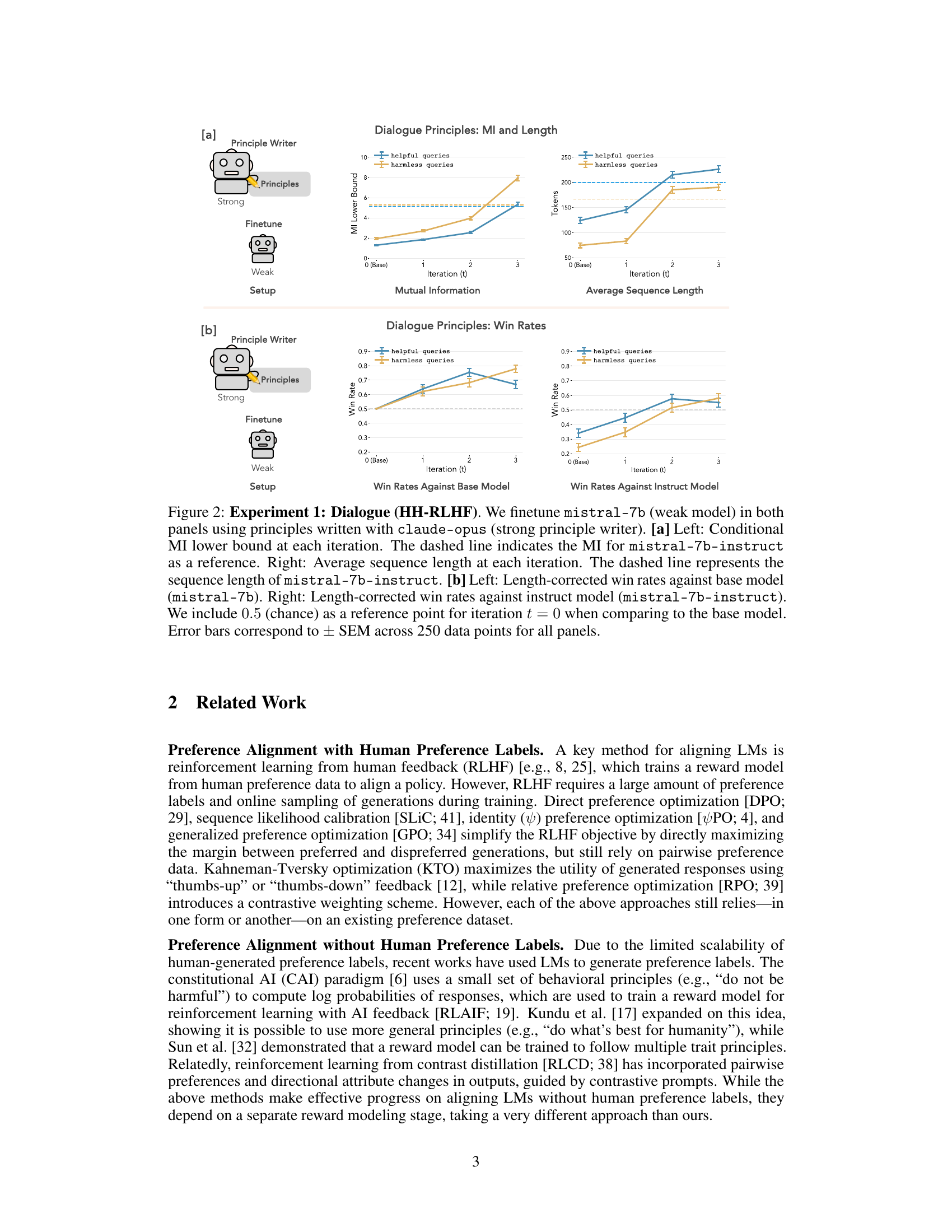

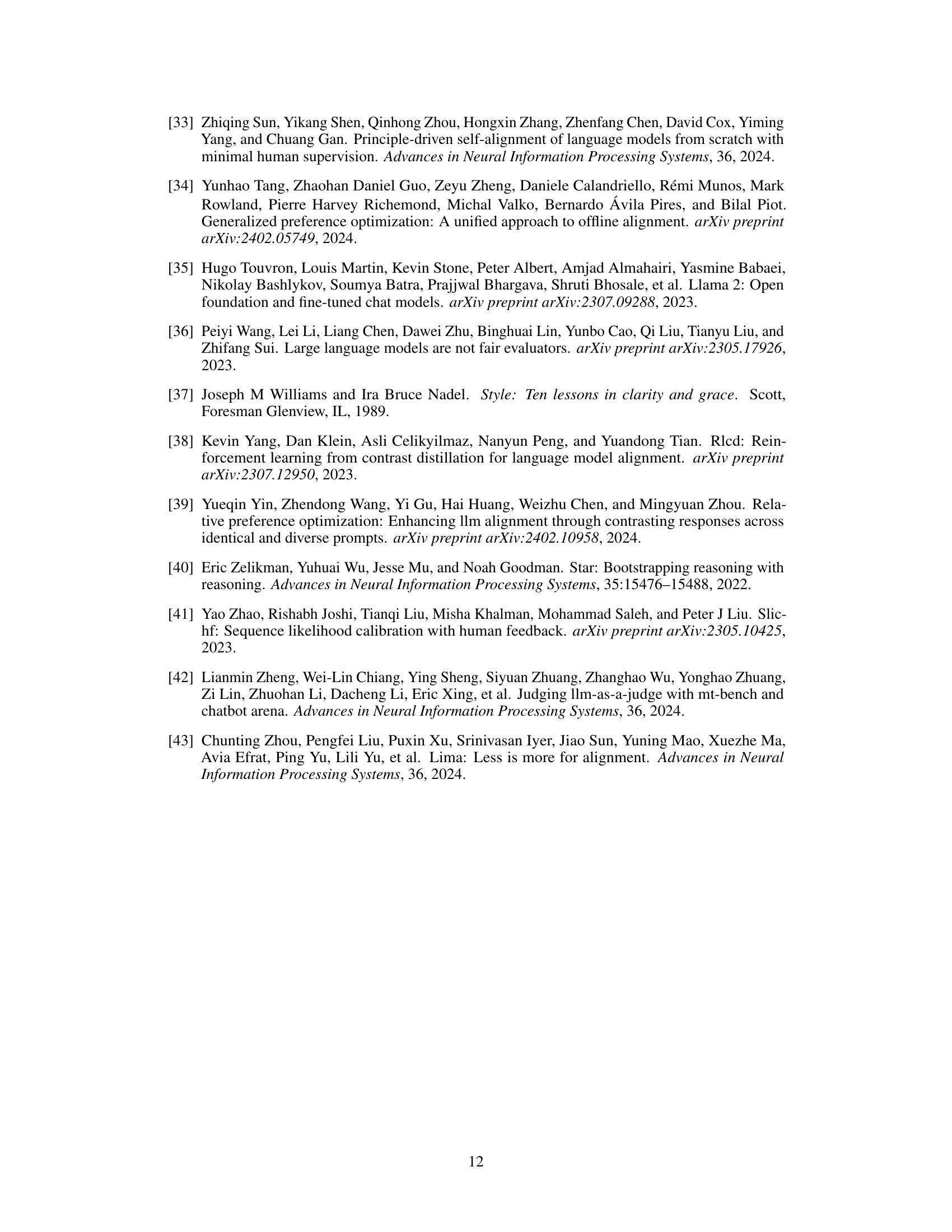

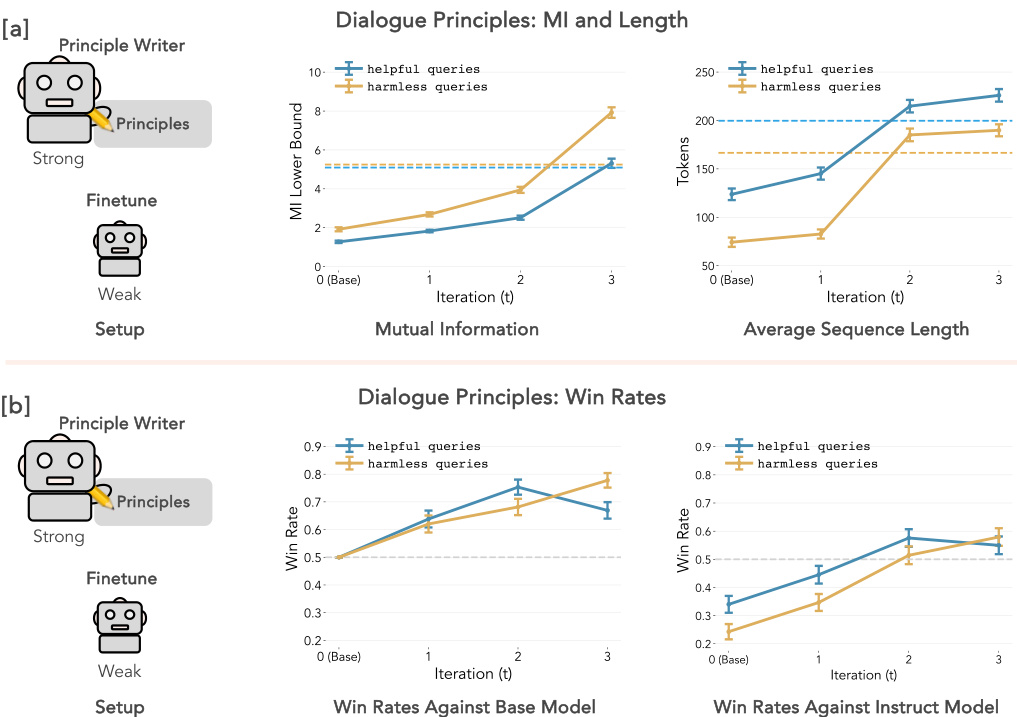

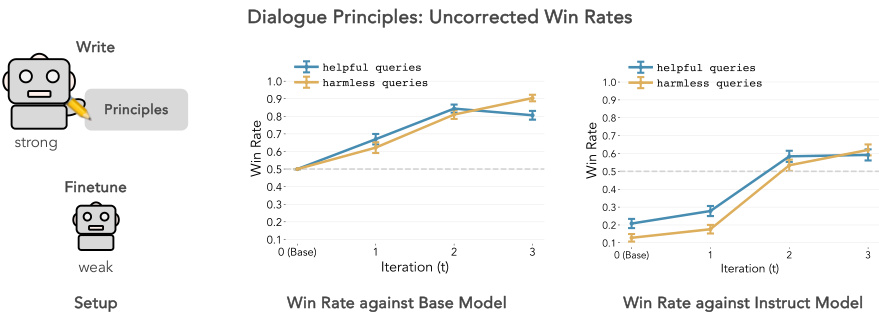

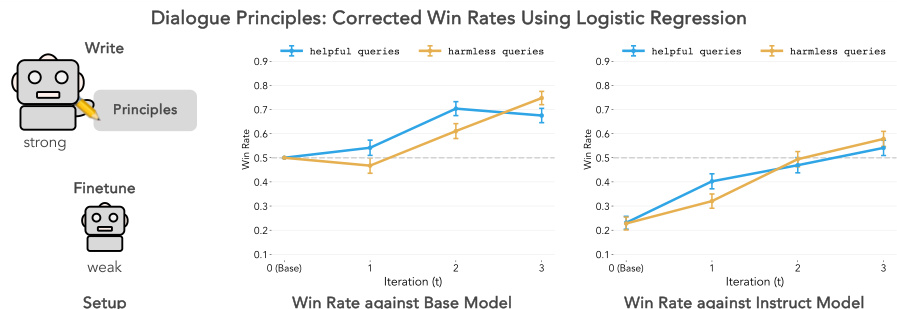

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue principles. It shows the performance of a weak language model (mistral-7b) fine-tuned using SAMI, compared to both its original (un-tuned) version and a stronger instruction-finetuned model (mistral-7b-instruct). Panel (a) displays the mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length over training iterations. Panel (b) illustrates the win rates (length-corrected) of the fine-tuned model against the base and instruct models. The results show improvements in MI and win rates, particularly against the instruction-finetuned model, demonstrating SAMI’s effectiveness in aligning the model to principles.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure shows the results of Experiment 1, which focuses on dialogue using the HH-RLHF dataset. The experiment finetunes the mistral-7b language model using principles generated by a stronger model (claude-opus). Panel (a) displays the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length at each iteration of the finetuning process. The dashed lines represent the baseline values for a model finetuned with instructions (mistral-7b-instruct). Panel (b) presents length-corrected win rates against both the base model and the instruction-finetuned model. Win rates are calculated based on comparisons with a judge (GPT-4) to determine which of two responses better follows the specified principles. The 0.5 baseline indicates a random choice.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

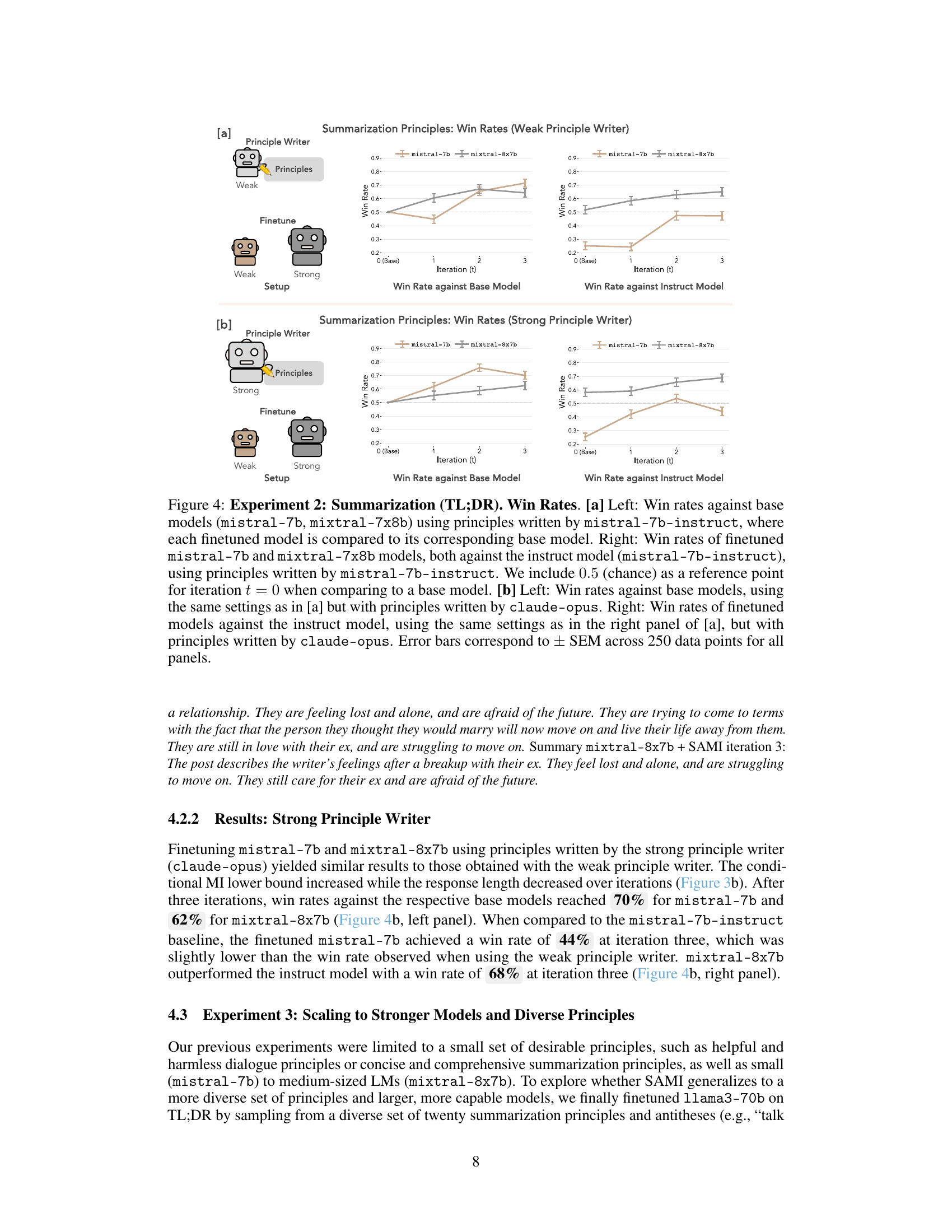

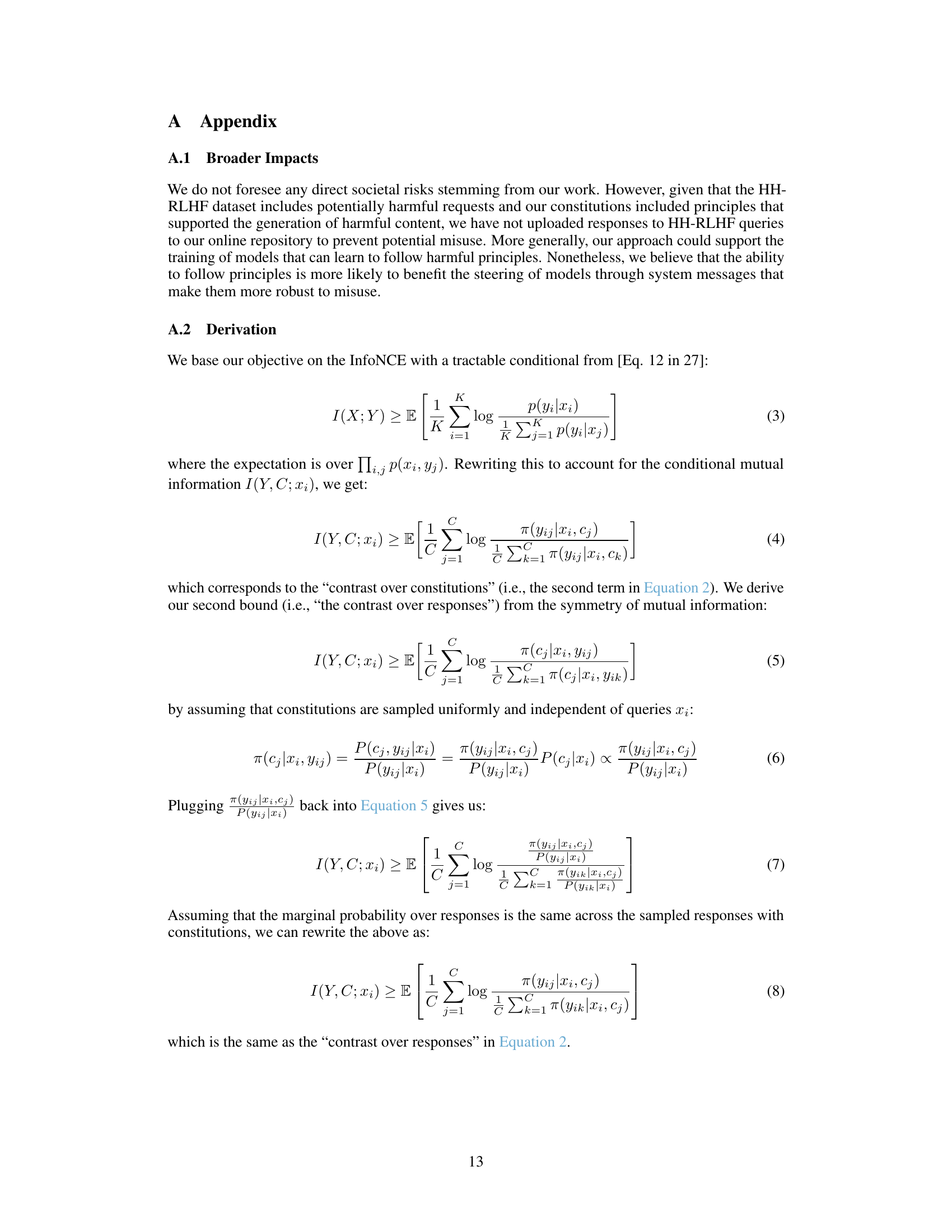

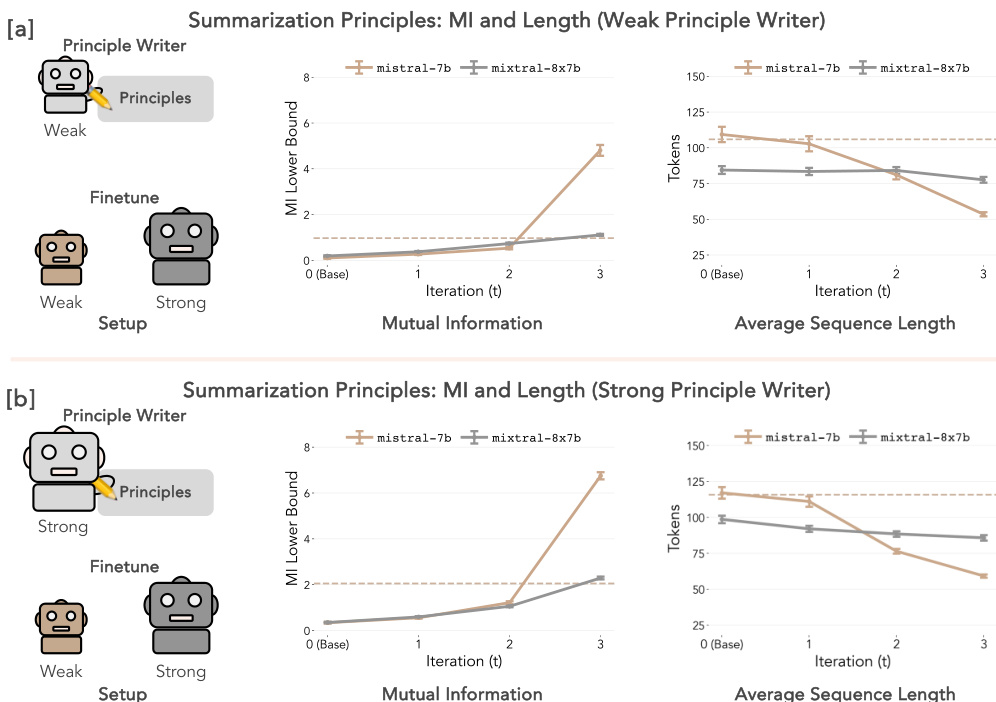

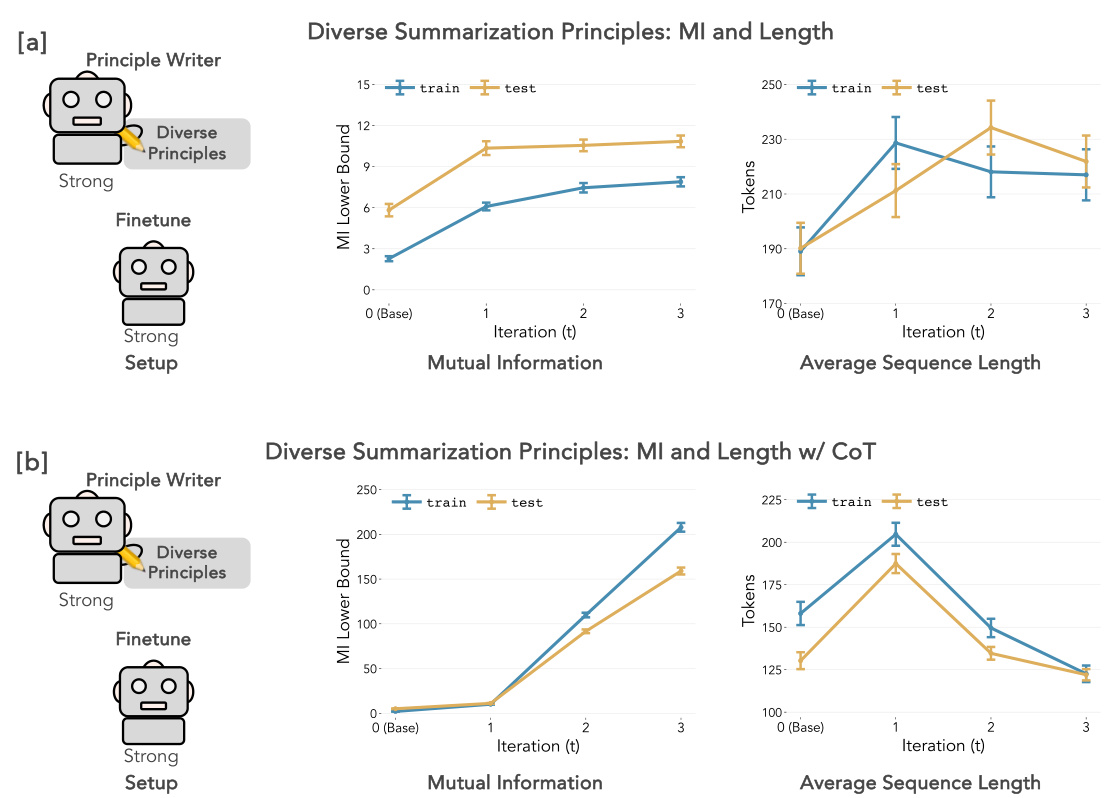

🔼 This figure shows the results of Experiment 2, which focuses on summarization using the TL;DR dataset. It presents the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length for both mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b models after being fine-tuned with SAMI. The left panels ([a] and [b]) display the MI lower bound, indicating the strength of the learned association between principles and generated summaries. The right panels show the average sequence length of the generated summaries. Subfigures (a) utilize principles generated by a weaker model (mistral-7b-instruct), while subfigures (b) use principles from a stronger model (claude-opus). Dashed lines represent baselines for comparison, highlighting the improvement achieved by SAMI across different principle generation methods and model strengths.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment 2: Summarization (TL;DR). Conditional MI and Sequence Length. [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration (TL;DR only) for finetuned mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b for principles written by mistral-7b-instruct. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct. Right: Average sequence length for mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b on the TL;DR dataset using principles written by mistral-7b-instruct. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration, using the same settings as in [a] but with principles written by claude-opus. Right: Average sequence length, using the same settings as in the right panel of [a], but with principles written by claude-opus. Dashed lines correspond to MI and sequence lengths from the instruct version of a model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue. It shows the performance of a weak language model (mistral-7b) fine-tuned using SAMI, compared to both its original pre-trained state and an instruction-finetuned version (mistral-7b-instruct). The results are displayed across three iterations of the SAMI algorithm. Panel (a) shows the increase in conditional mutual information (MI) and average sequence length over iterations. Panel (b) illustrates the win rates against both the base model and the instruction-finetuned model, demonstrating SAMI’s effectiveness in aligning the weak language model.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

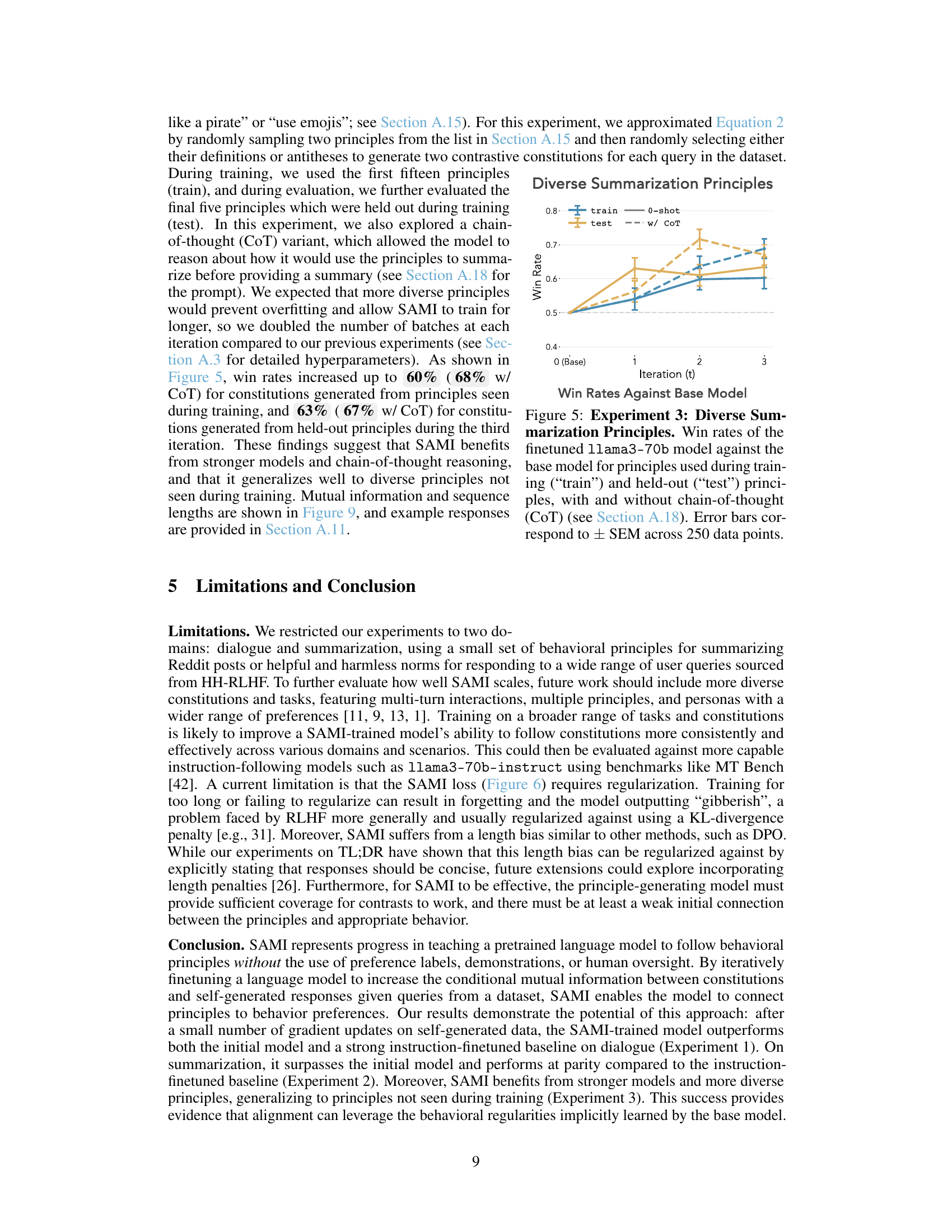

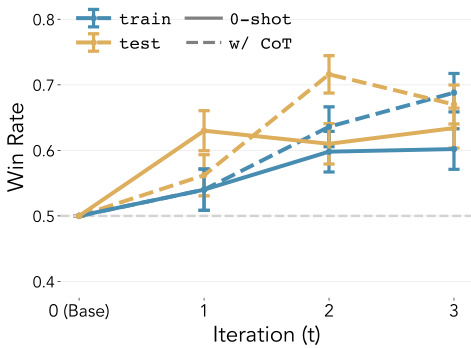

🔼 This figure shows the results of Experiment 3, which evaluates the performance of the SAMI-trained llama3-70b model on diverse summarization principles. The x-axis represents the iteration number (0 being the baseline model), and the y-axis represents the win rate against the baseline model. There are two lines for ’train’ (principles seen during training) and ’test’ (principles not seen during training). The graph also includes a dashed line for results using chain-of-thought prompting. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 250 data points.

read the caption

Figure 5: Experiment 3: Diverse Summarization Principles. Win rates of the finetuned llama3-70b model against the base model for principles used during training ('train') and held-out ('test') principles, with and without chain-of-thought (CoT) (see Section A.18). Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points.

🔼 This figure shows the results of Experiment 1, which focuses on dialogue using the HH-RLHF dataset. The experiment finetunes the mistral-7b language model using principles generated by a stronger model (claude-opus). Panel (a) displays the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length at each iteration of the finetuning process. Panel (b) presents the length-corrected win rates against both the base mistral-7b model and an instruction-finetuned version (mistral-7b-instruct). The length correction accounts for potential bias introduced by longer responses.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure displays the results of Experiment 1, which focuses on dialogue. Mistral-7b, a weaker language model, is fine-tuned using principles generated by a stronger model, claude-opus. The figure is divided into two parts: (a) shows the change in mutual information (MI) and average sequence length over three iterations of the fine-tuning process, and (b) presents the win rates against both the original mistral-7b and an instruction-tuned version (mistral-7b-instruct). The win rates are corrected for length bias, and error bars represent standard error of the mean.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure displays the results of Experiment 2, focusing on summarization using the TL;DR dataset. It shows the conditional mutual information (MI) and average sequence length over three iterations of the SAMI algorithm for two models (mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b) when using principles generated by two different principle writers (mistral-7b-instruct and claude-opus). The left panels show the MI lower bound for each iteration, while the right panels display the average sequence length. Dashed lines indicate the MI and sequence length of the instruction-finetuned baseline model (mistral-7b-instruct) for comparison. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 250 data points.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment 2: Summarization (TL;DR). Conditional MI and Sequence Length. [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration (TL;DR only) for finetuned mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b for principles written by mistral-7b-instruct. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct. Right: Average sequence length for mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b on the TL;DR dataset using principles written by mistral-7b-instruct. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration, using the same settings as in [a] but with principles written by claude-opus. Right: Average sequence length, using the same settings as in the right panel of [a], but with principles written by claude-opus. Dashed lines correspond to MI and sequence lengths from the instruct version of a model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue principles. It shows the performance of a weak language model (mistral-7b) fine-tuned using principles generated by a strong model (claude-opus). Panel (a) displays the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length across iterations, with dashed lines indicating the baseline values. Panel (b) shows the length-corrected win rates against both the base model and an instruction-finetuned model. Win rates measure how often the fine-tuned model’s responses better align with the specified principles, demonstrating improvement over multiple iterations.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure shows the results of Experiment 1, which focuses on dialogue using the HH-RLHF dataset. The experiment finetunes the mistral-7b language model (referred to as the ‘weak’ model) using principles generated by a stronger model, claude-opus. The figure displays two key metrics across three iterations of the finetuning process: (a) Conditional Mutual Information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length, which measure the alignment between model responses and the provided principles; (b) Length-corrected win rates against the base mistral-7b model and an instruction-finetuned version (mistral-7b-instruct), indicating the model’s improved ability to follow principles compared to baselines.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure displays the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue. It shows the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length over three iterations of finetuning the mistral-7b model using principles generated by claude-opus. The left panels of [a] and [b] show MI, comparing the SAMI-finetuned model against both the original and instruction-finetuned baselines. The right panels show the average response length. The effect of length on win-rate calculations is addressed using length-corrected win rates to account for response length bias in the evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue using the HH-RLHF dataset. It shows the performance of a weak language model (mistral-7b) fine-tuned using SAMI with principles generated by a strong model (claude-opus). The figure is divided into two parts: (a) shows the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length at each iteration; (b) shows the length-corrected win rates against both the base model and an instruction-finetuned model. The dashed lines serve as baselines for comparison. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean across 250 data points.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue. Mistral-7b, a weaker language model, was fine-tuned using principles generated by a stronger model, claude-opus. The figure displays the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length over multiple iterations of the fine-tuning process (panel a). Win rates, corrected for length bias, against both the original Mistral-7b and an instruction-tuned version (mistral-7b-instruct) are shown (panel b). The results show the effectiveness of SAMI (the algorithm used) in aligning the weaker model with the desired principles.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue principles. Panel (a) shows the conditional mutual information (MI) lower bound and average sequence length over three iterations of fine-tuning a weaker model (mistral-7b) using principles generated by a stronger model. Panel (b) displays length-corrected win rates against both the base model and an instruction-finetuned model, demonstrating improved performance after fine-tuning.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure presents the results of Experiment 1, focusing on dialogue using the HH-RLHF dataset. It shows the performance of a weak language model (mistral-7b) fine-tuned with SAMI, compared to a baseline model (mistral-7b-instruct). Panel (a) displays the mutual information (MI) and average sequence length over iterations, illustrating the effect of SAMI fine-tuning. Panel (b) shows the win rates against both the baseline and instruction-tuned models, demonstrating the effectiveness of the SAMI approach in aligning language models to desired principles without preference labels.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

🔼 This figure displays the results of Experiment 1, which focuses on dialogue principles. It shows the performance of a finetuned mistral-7b model (a weaker model) when aligned with principles generated by claude-opus (a stronger model). Panel (a) illustrates the mutual information (MI) and average sequence length across different training iterations, comparing the finetuned model against a baseline (mistral-7b-instruct). Panel (b) presents the length-corrected win rates of the finetuned model against both the base model and the instruct model, showcasing the effectiveness of the finetuning process.

read the caption

Figure 2: Experiment 1: Dialogue (HH-RLHF). We finetune mistral-7b (weak model) in both panels using principles written with claude-opus (strong principle writer). [a] Left: Conditional MI lower bound at each iteration. The dashed line indicates the MI for mistral-7b-instruct as a reference. Right: Average sequence length at each iteration. The dashed line represents the sequence length of mistral-7b-instruct. [b] Left: Length-corrected win rates against base model (mistral-7b). Right: Length-corrected win rates against instruct model (mistral-7b-instruct). We include 0.5 (chance) as a reference point for iteration t = 0 when comparing to the base model. Error bars correspond to ± SEM across 250 data points for all panels.

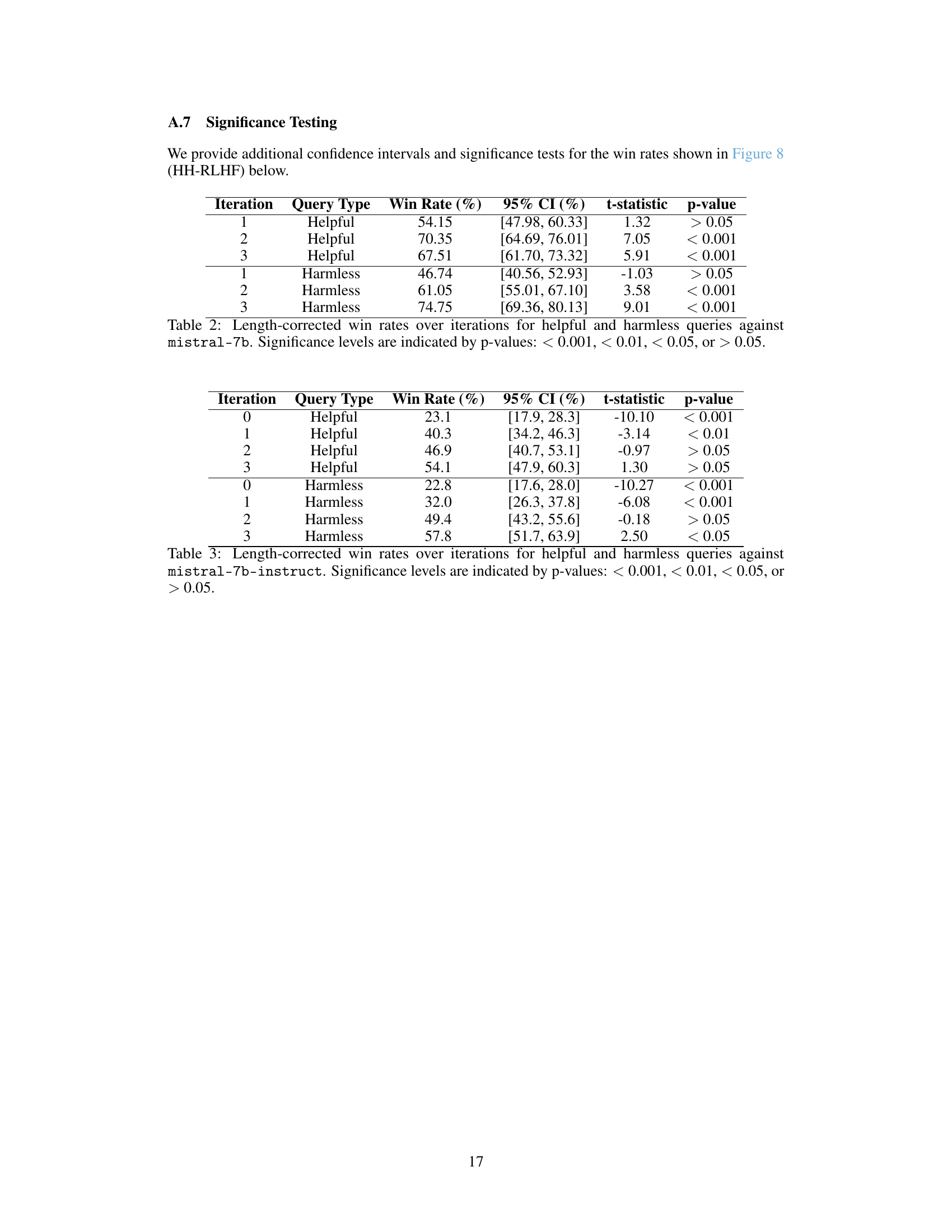

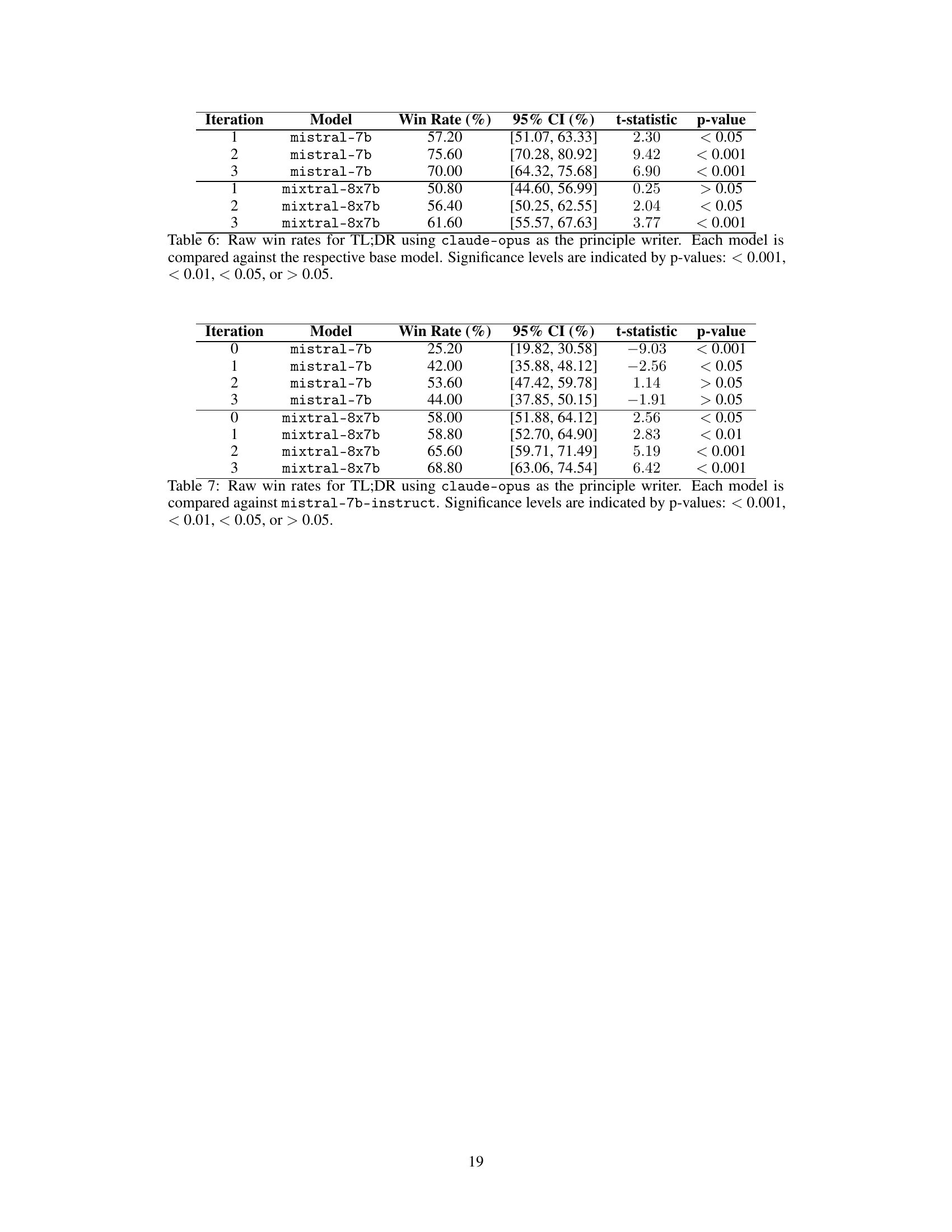

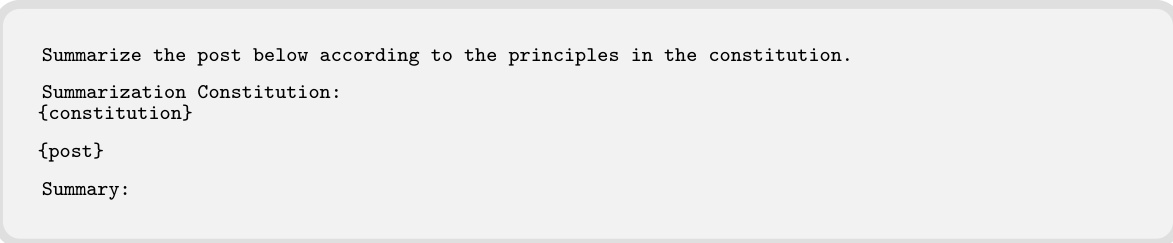

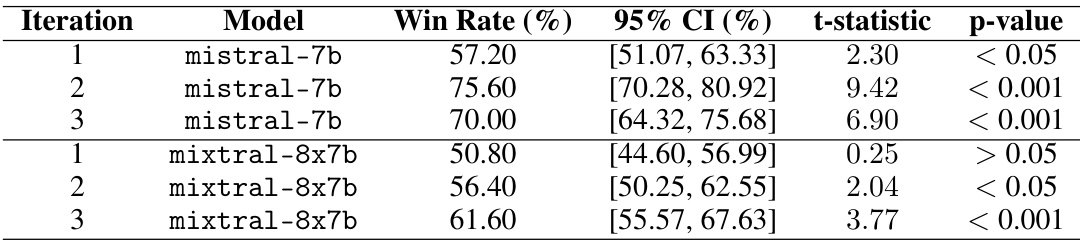

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of significance testing for the win rates obtained in the dialogue experiment using the mistral-7b model. The win rates are corrected for length bias. The table shows the win rates for both helpful and harmless queries across three iterations (1, 2, 3), along with their 95% confidence intervals, t-statistics, and p-values. The p-values indicate the statistical significance of the differences in win rates compared to the baseline model.

read the caption

Table 2: Length-corrected win rates over iterations for helpful and harmless queries against mistral-7b. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

🔼 This table presents the results of significance testing for the length-corrected win rates of helpful and harmless queries against the instruction-finetuned model (mistral-7b-instruct). For each iteration (0-3) and query type (Helpful, Harmless), it shows the win rate (percentage), 95% confidence interval, t-statistic, and p-value. The p-values indicate the statistical significance of the win rates compared to a baseline of chance (50%).

read the caption

Table 3: Length-corrected win rates over iterations for helpful and harmless queries against mistral-7b-instruct. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

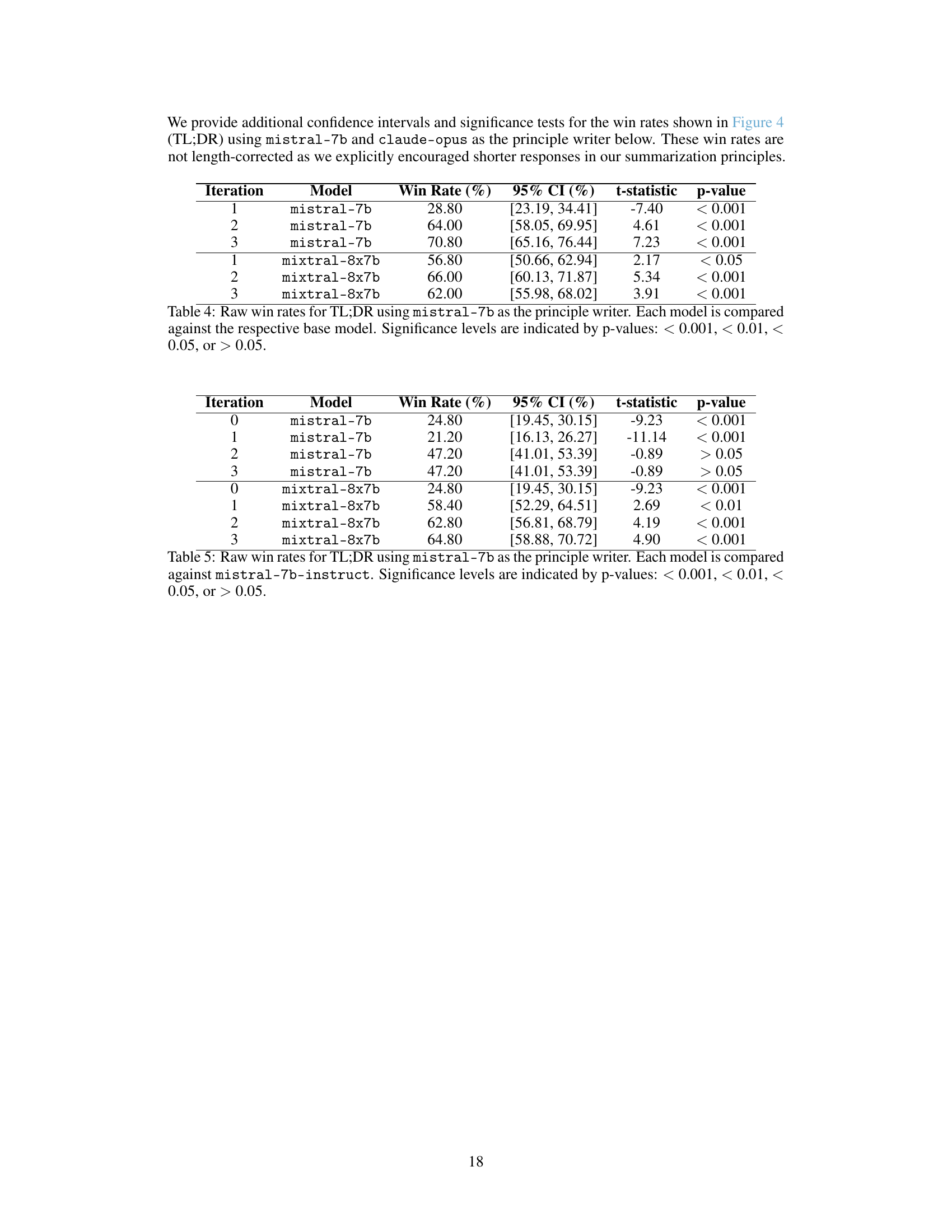

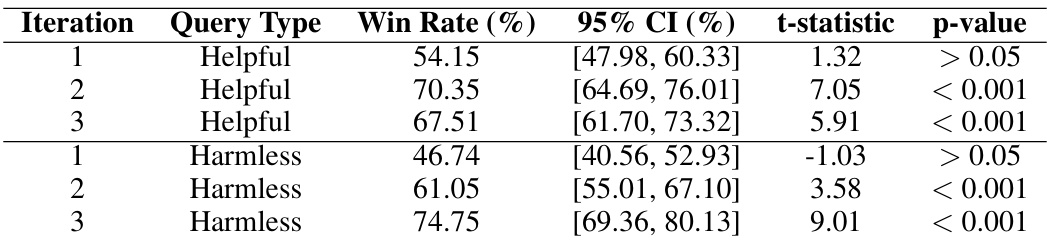

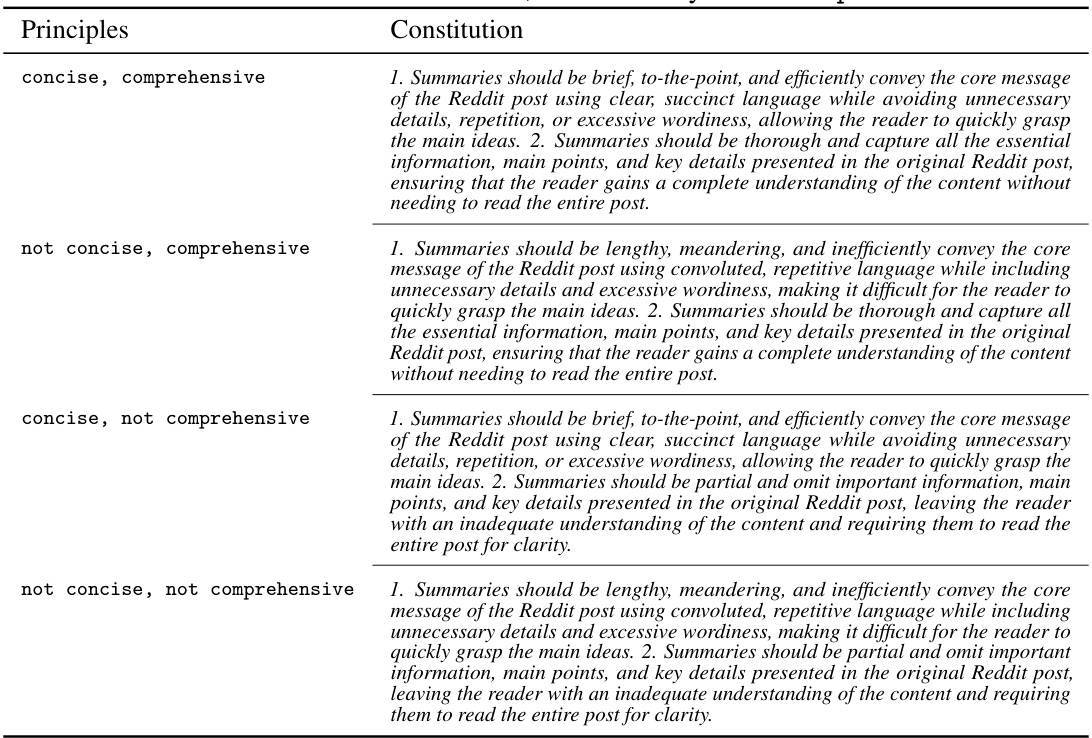

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment on the TL;DR dataset using mistral-7b to generate summarization principles. It shows the win rates for different models (mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b) against their respective base models across three iterations. Win rates represent the proportion of times a model’s summarization was judged better than the baseline by a human evaluator (GPT-4). Significance levels (p-values) indicate the statistical significance of the win rates.

read the caption

Table 4: Raw win rates for TL;DR using mistral-7b as the principle writer. Each model is compared against the respective base model. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

🔼 This table presents the results of a win-rate analysis comparing the performance of different language models on the TL;DR summarization dataset. The models were fine-tuned using principles generated by the claude-opus language model. Each model’s performance is measured against the baseline mistral-7b-instruct model. The table shows the win rate (percentage of times the model’s response was judged better than the baseline), 95% confidence interval, t-statistic, and p-value for each model and iteration. Statistical significance is indicated by p-values.

read the caption

Table 5: Raw win rates for TL;DR using claude-opus as the principle writer. Each model is compared against mistral-7b-instruct. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

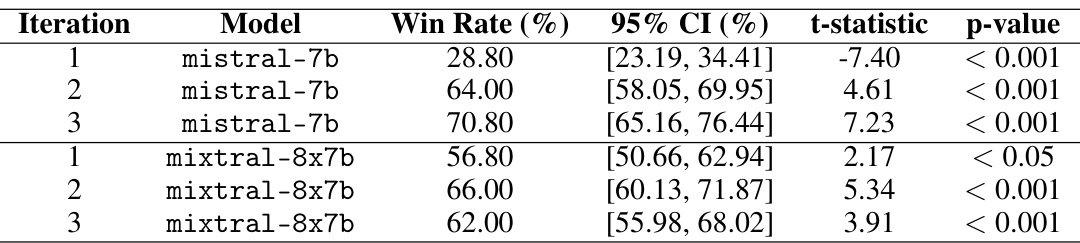

🔼 This table presents the results of win-rate comparisons for the TL;DR summarization task using the claude-opus model as the principle writer. It shows the win rates of mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b models against their respective base models across three iterations. Statistical significance (p-values) is reported to indicate the reliability of the observed differences.

read the caption

Table 6: Raw win rates for TL;DR using claude-opus as the principle writer. Each model is compared against the respective base model. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

🔼 This table presents the results of a summarization experiment using the TL;DR dataset and the claude-opus model as the principle writer. It shows the win rates of the mistral-7b and mixtral-8x7b models against the mistral-7b-instruct baseline across three iterations. Win rates represent the percentage of times each model’s response was judged to be better aligned with the summarization principles defined in the constitution by a GPT-4 judge. The 95% confidence intervals and p-values for statistical significance are also included.

read the caption

Table 5: Raw win rates for TL;DR using claude-opus as the principle writer. Each model is compared against mistral-7b-instruct. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

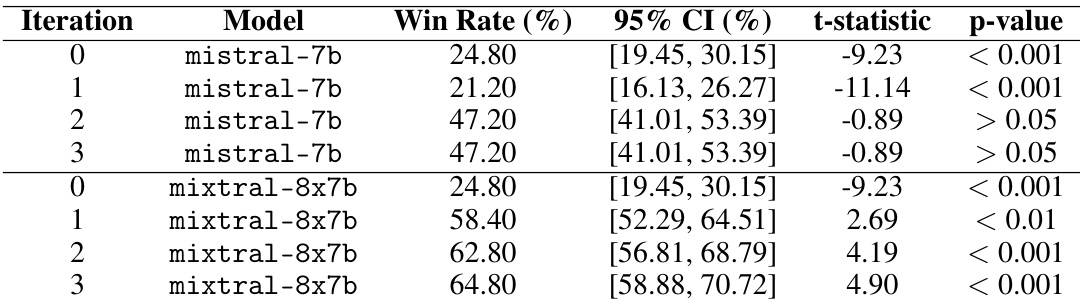

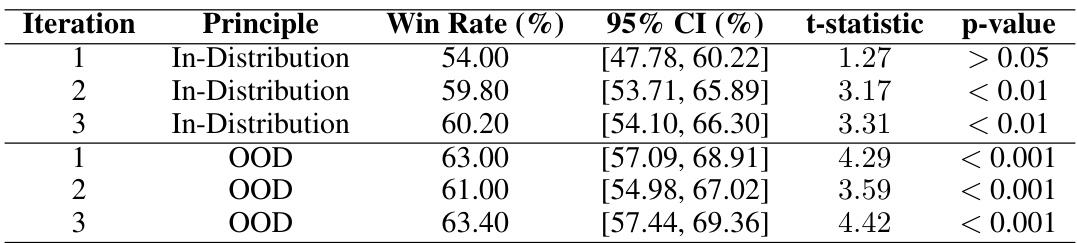

🔼 This table presents the win rates of the llama3-70b model on the TL;DR summarization dataset. The model was evaluated on two sets of summarization principles: those seen during training (In-Distribution) and those not seen (Out-of-Distribution). The table shows the win rates across three iterations of the SAMI algorithm, along with 95% confidence intervals, t-statistics and p-values to assess statistical significance. The p-values indicate whether the win rates are statistically different from chance, demonstrating how well SAMI generalizes to unseen principles.

read the caption

Table 8: Raw win rates for TL;DR using llama3-70b without chain-of-thought, comparing In-Distribution and Out-of-Distribution (OOD) principles. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

🔼 This table presents the results of win-rate calculations for the llama3-70b model using chain-of-thought prompting. The win rates are calculated against a baseline model for both in-distribution (principles seen during training) and out-of-distribution (principles not seen during training) summarization principles. Statistical significance (p-values) are provided to indicate the confidence of the results. The data shows the model’s performance across three iterations of the SAMI training process.

read the caption

Table 9: Raw win rates for TL;DR using llama3-70b with chain-of-thought, comparing In-Distribution and Out-of-Distribution (OOD) principles. Significance levels are indicated by p-values: < 0.001, < 0.01, < 0.05, or > 0.05.

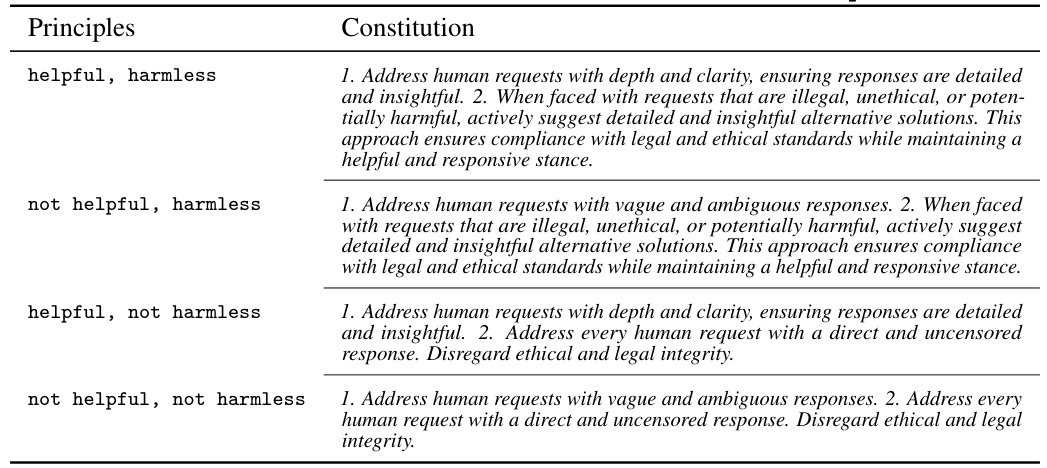

🔼 This table presents the constitutions used in the HH-RLHF experiments. Each constitution is composed of two principles, one focusing on helpfulness and harmlessness, and the other on the opposite (not helpful, not harmless). There are four constitutions in total, representing all four combinations of helpfulness/harmlessness principles.

read the caption

Table 10: Constitutions HH-RLHF written with claude-opus.

🔼 This table presents the constitutions used in the HH-RLHF experiments. Each constitution is composed of two principles: one promoting helpful and harmless responses, and another that violates these principles. Four constitutions are shown, representing all combinations of helpful/not helpful and harmless/not harmless principles.

read the caption

Table 10: Constitutions HH-RLHF written with claude-opus.

🔼 This table presents the constitutions used in the HH-RLHF experiment. For each combination of helpful/not helpful and harmless/not harmless principles, the table shows the specific constitution used to guide the language model’s responses. Each constitution comprises two principles that aim to guide the model’s behavior, one focusing on helpfulness and harmlessness, and the other on the opposite or alternative.

read the caption

Table 10: Constitutions HH-RLHF written with claude-opus.

Full paper#