TL;DR#

Multi-task learning (MTL) and pretraining plus finetuning (PT+FT) are widely used to train neural networks for multiple tasks. However, the inductive biases that shape how these methods impact learning and generalization have been poorly understood, causing suboptimal model performance. This paper investigates this gap by analyzing the implicit regularization penalties associated with these methods in different network architectures.

The researchers introduce a novel technique of weight rescaling following pretraining, which allows PT+FT to leverage the “nested feature selection” regime. This regime biases the network towards reusing a sparse set of features learned during pretraining, leading to improved generalization. Their experiments validate this finding in both simple and deep neural networks, demonstrating significant improvements on Image Classification tasks when the weight rescaling is applied. Their results highlight a previously uncharacterized inductive bias for finetuning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep learning and multi-task learning. It offers novel theoretical insights into the inductive biases of multi-task learning and finetuning, which are central to current research trends in foundation models and continual learning. The identification of the nested feature selection regime and the weight rescaling technique provides practical guidance for improving model performance and opens new avenues for investigation into how task structure and optimization affect generalization.

Visual Insights#

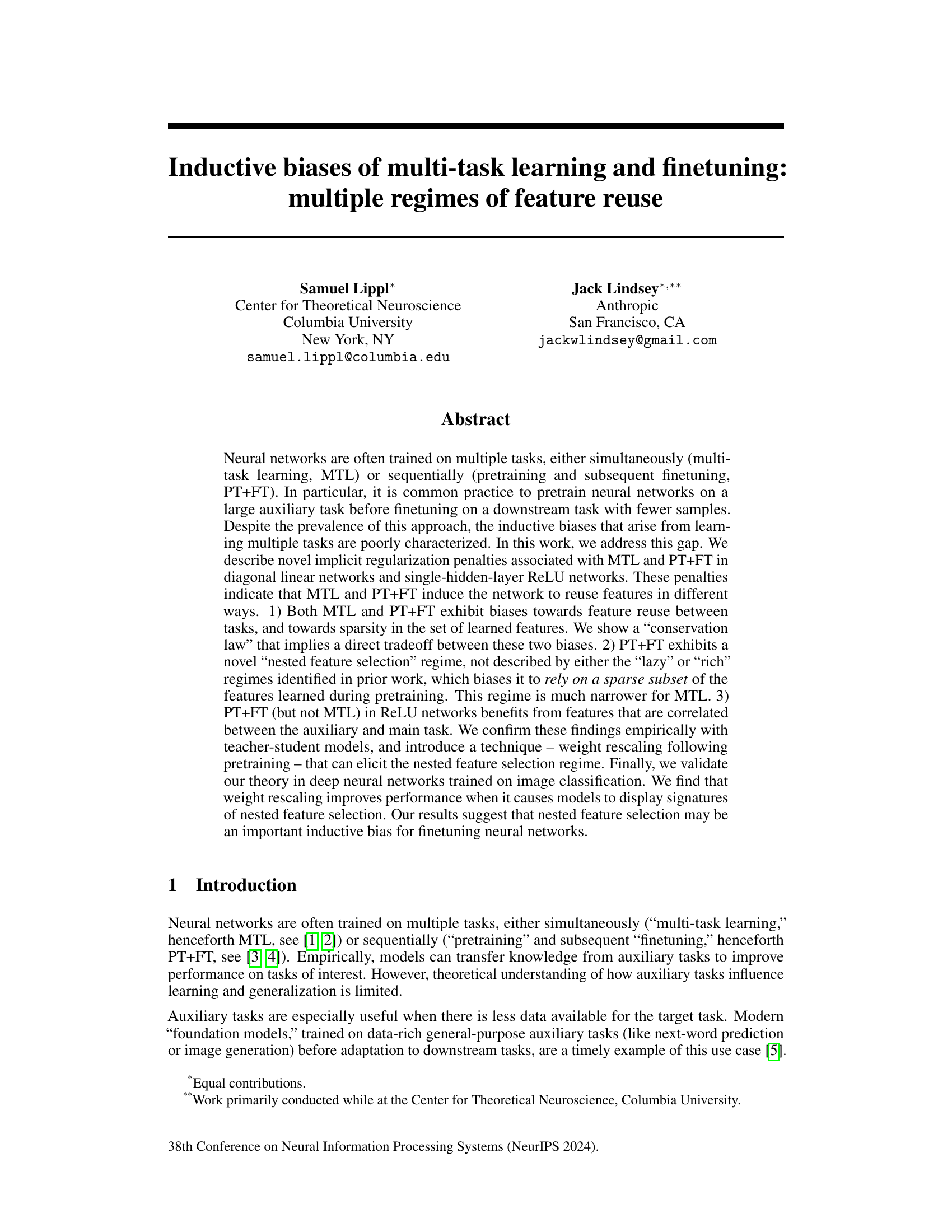

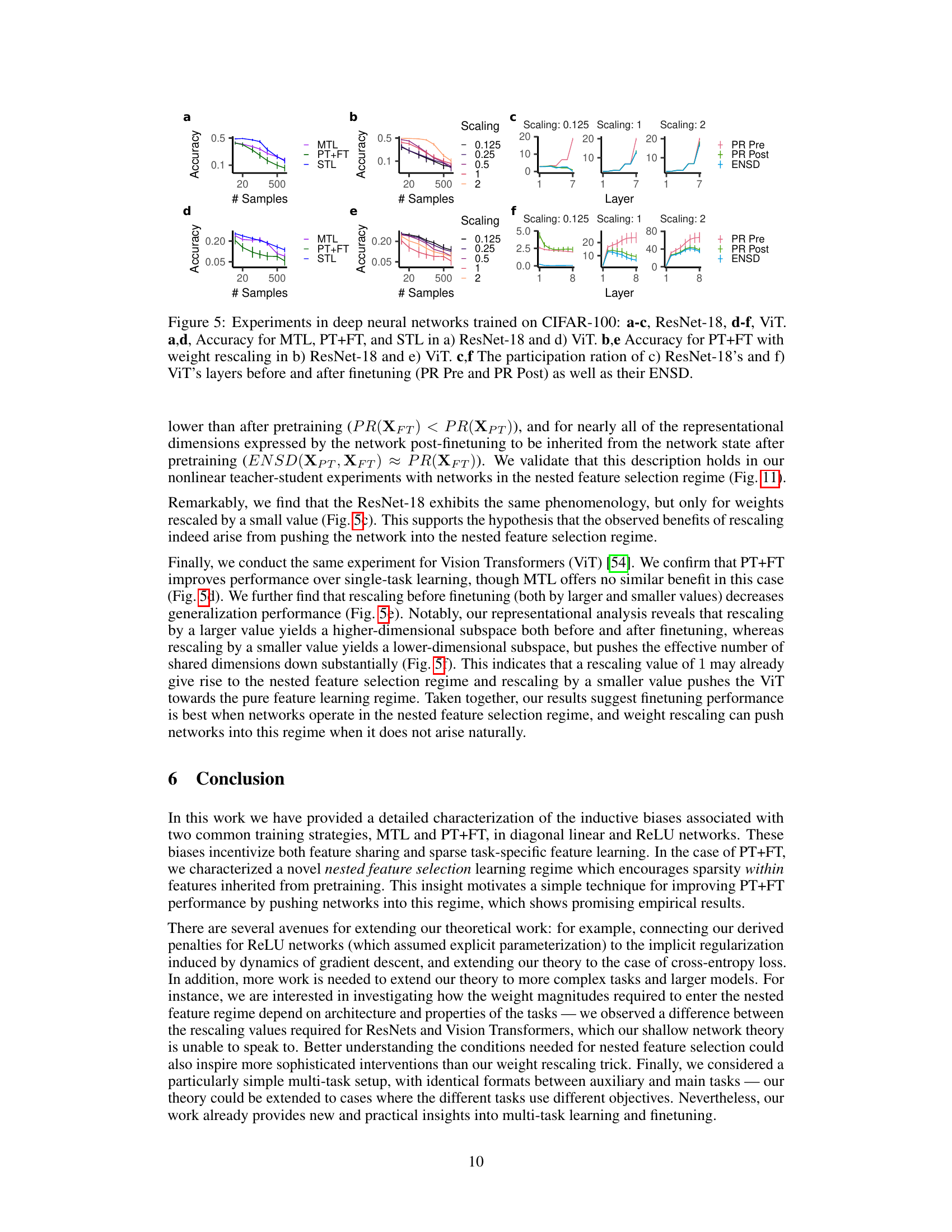

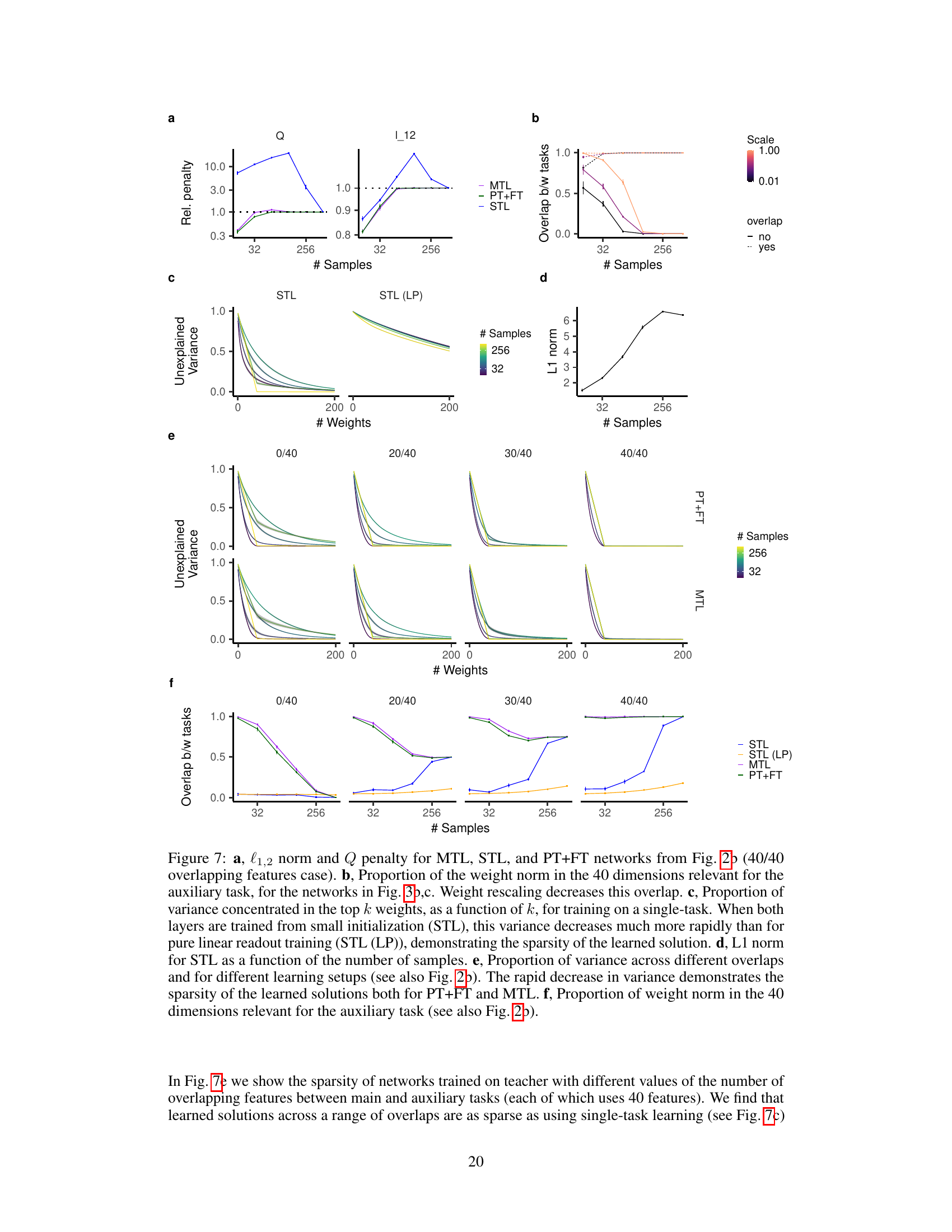

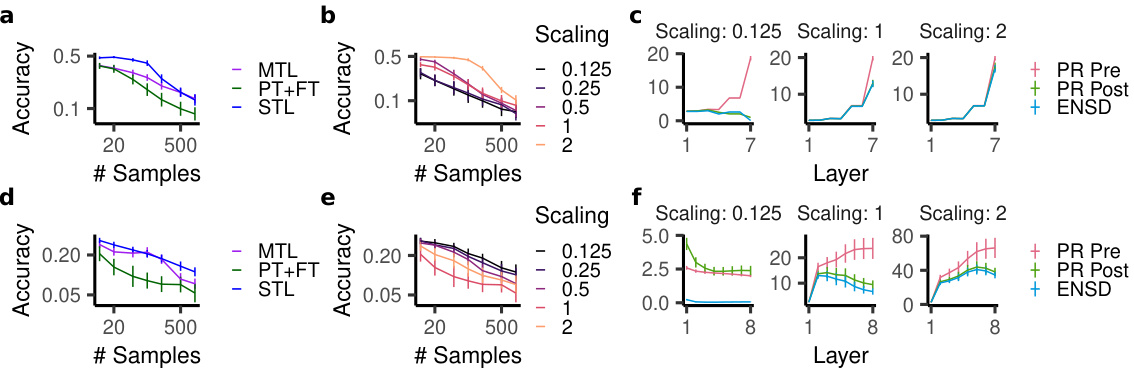

🔼 This figure displays theoretically derived regularization penalties for multi-task learning (MTL) and pretraining and finetuning (PT+FT) in diagonal linear networks and ReLU networks. Panel (a) shows the explicit regularization penalty for MTL. Panel (b) shows the implicit regularization penalty for PT+FT in diagonal linear networks. Panel (c) shows the explicit regularization penalty for PT+FT in ReLU networks, highlighting its dependence on changes in feature direction during finetuning.

read the caption

Figure 1: Theoretically derived regularization penalties. a, Explicit regularization penalty associated with multi-task learning. b, Implicit regularization penalty associated with finetuning in diagonal linear networks. c, Explicit regularization penalty associated with finetuning in ReLU networks. This penalty also depends on the changes in feature direction over finetuning (measured by the correlation between the unit-normalized feature directions pre vs. post finetuning).

In-depth insights#

Multitask Learning Bias#

Multitask learning (MTL), while offering potential benefits like improved sample efficiency and generalization, introduces inherent biases. A core bias stems from the network’s tendency to reuse features learned during training on auxiliary tasks when tackling the main task. This feature reuse, while sometimes advantageous, can lead to the propagation of biases from the auxiliary tasks to the main task. The extent of feature reuse depends on factors like task similarity, network architecture, and optimization algorithms. Understanding these biases is crucial for effective MTL, as they can significantly affect performance and generalization. The paper investigates these biases, exploring how various training paradigms impact the way features are reused and the resulting implicit regularizations. This analysis provides insights into the inductive biases of MTL, contributing to a deeper understanding of how this approach shapes the learning process and what techniques can mitigate potential downsides. The study highlights a “conservation law” showcasing a trade-off between feature reuse and sparsity indicating that methods promoting sparsity may indirectly limit feature reuse. By carefully considering these biases and their implications, researchers can better harness the power of MTL while avoiding its potential pitfalls.

Feature Reuse Regimes#

The study’s core contribution lies in its exploration of feature reuse regimes in multi-task learning (MTL) and pretraining-finetuning (PT+FT). It reveals that MTL and PT+FT, while both promoting feature reuse, exhibit distinct biases. MTL displays a bias toward overall feature sparsity and reuse, while PT+FT demonstrates a more nuanced “nested feature selection” regime. This regime prioritizes a sparse subset of features learned during pretraining, especially effective when the main task shares a significant overlap with the auxiliary task. The paper further introduces a novel weight rescaling technique to enhance the nested feature selection effect in PT+FT, leading to improved performance in deep networks. This highlights the critical role of architecture and training strategy in shaping the inductive biases, with implications for optimizing feature reuse in different contexts. Weight rescaling improves performance by promoting the nested feature selection, revealing a crucial inductive bias for finetuning neural networks.

Weight Rescaling Impact#

The research explores how rescaling network weights before finetuning impacts performance, particularly focusing on the nested feature selection regime. Weight rescaling, a simple technique, is shown to improve accuracy in ResNets, suggesting its potential practical value. The study validates this finding by analyzing network representations and showing that effective weight rescaling pushes networks into this beneficial regime. Importantly, the effect of rescaling is shown to differ across network architectures. While ResNets exhibit improved performance with rescaling, Vision Transformers do not, suggesting architecture-specific considerations are necessary. The core insight is that effective rescaling causes the network to rely on a lower-dimensional subspace of its pretrained representation, a key characteristic of the nested feature selection regime that promotes efficient learning in downstream tasks. This highlights the importance of carefully considering both network architecture and weight initialization in order to successfully leverage the benefits of nested feature selection.

Nested Feature Selection#

The concept of “Nested Feature Selection” presented in the research paper offers a novel perspective on the inductive biases inherent in fine-tuning neural networks. It posits that finetuning, unlike multi-task learning, exhibits a bias towards selecting a sparse subset of features from the pretrained model, rather than learning entirely new features or reusing all previously learned features. This ’nested’ approach is particularly beneficial when the target task shares features with the auxiliary task but doesn’t require all of them. The theoretical analysis, supported by empirical results, suggests that this bias is an important inductive factor, potentially explaining the success of finetuning in various scenarios. Weight rescaling emerges as a crucial technique for triggering or enhancing this nested selection process, emphasizing its role as a control mechanism over feature reuse behavior. The study highlights a trade-off between sparsity and feature dependence, implying that models can achieve good performance by judiciously selecting a small but relevant set of pretrained features. This framework is not limited to shallow networks but extends to deep convolutional and transformer models, opening up potential avenues for optimizing finetuning strategies and advancing the theoretical understanding of transfer learning.

Deep Network Analysis#

Analyzing deep networks presents unique challenges due to their high dimensionality and complexity. Standard linear model analysis is insufficient. Instead, methods focusing on representation learning, such as analyzing the dimensionality of learned feature spaces (e.g., via participation ratio) and the alignment between feature representations across different tasks (e.g., via effective number of shared dimensions), offer valuable insights. Investigating how the network’s internal structure changes throughout training (e.g., weight rescaling effects) can reveal implicit regularisation patterns. Furthermore, understanding the interplay between feature sparsity and reuse across tasks is critical. Teacher-student model approaches are useful for isolating the impact of specific inductive biases, while empirical validation on image classification tasks provides insights into the generalization of theoretical findings to real-world scenarios. Careful study of weight changes and feature subspace dimensionality offers a pathway to uncover how deep networks achieve their performance, ultimately revealing important insights into the inductive biases driving feature reuse and the benefits of weight rescaling in finetuning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

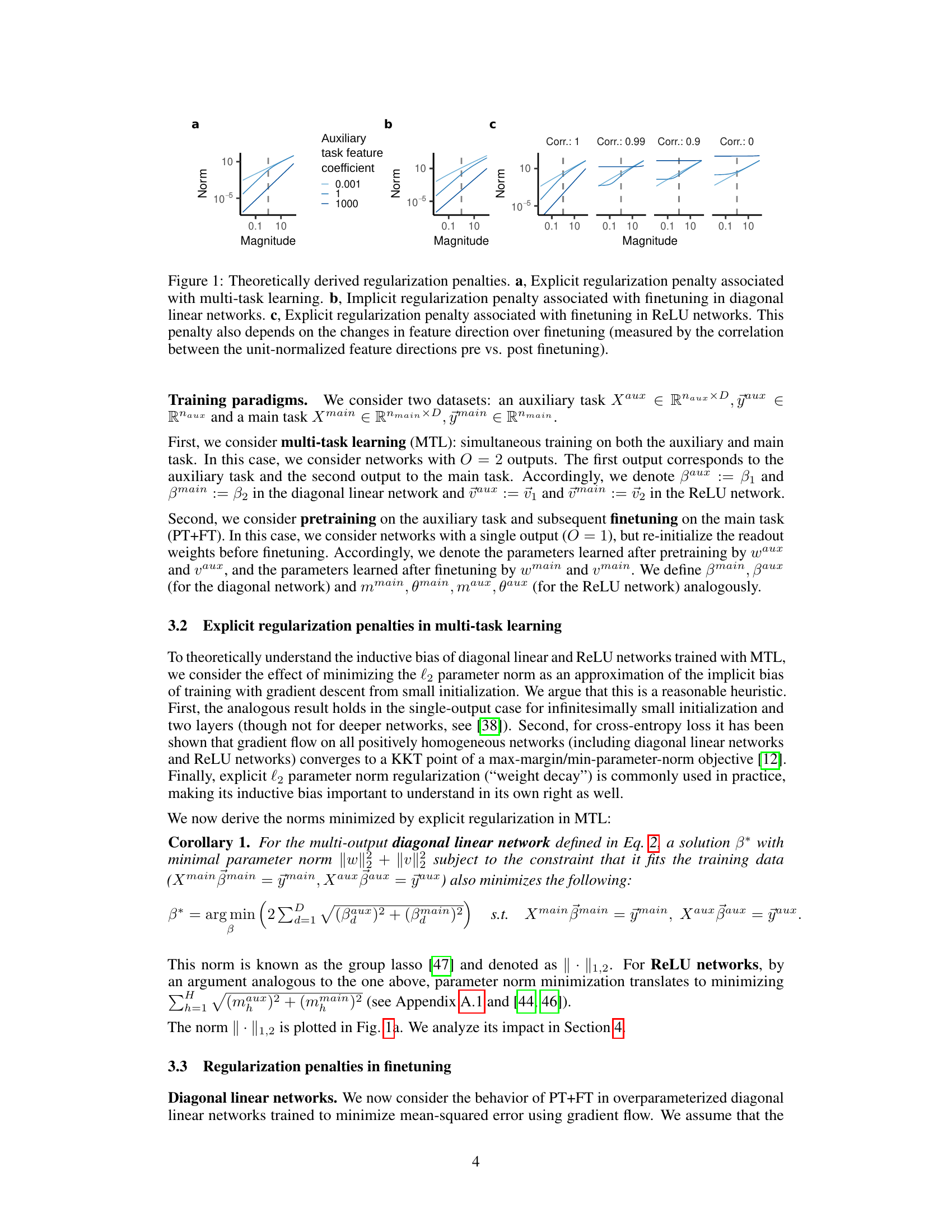

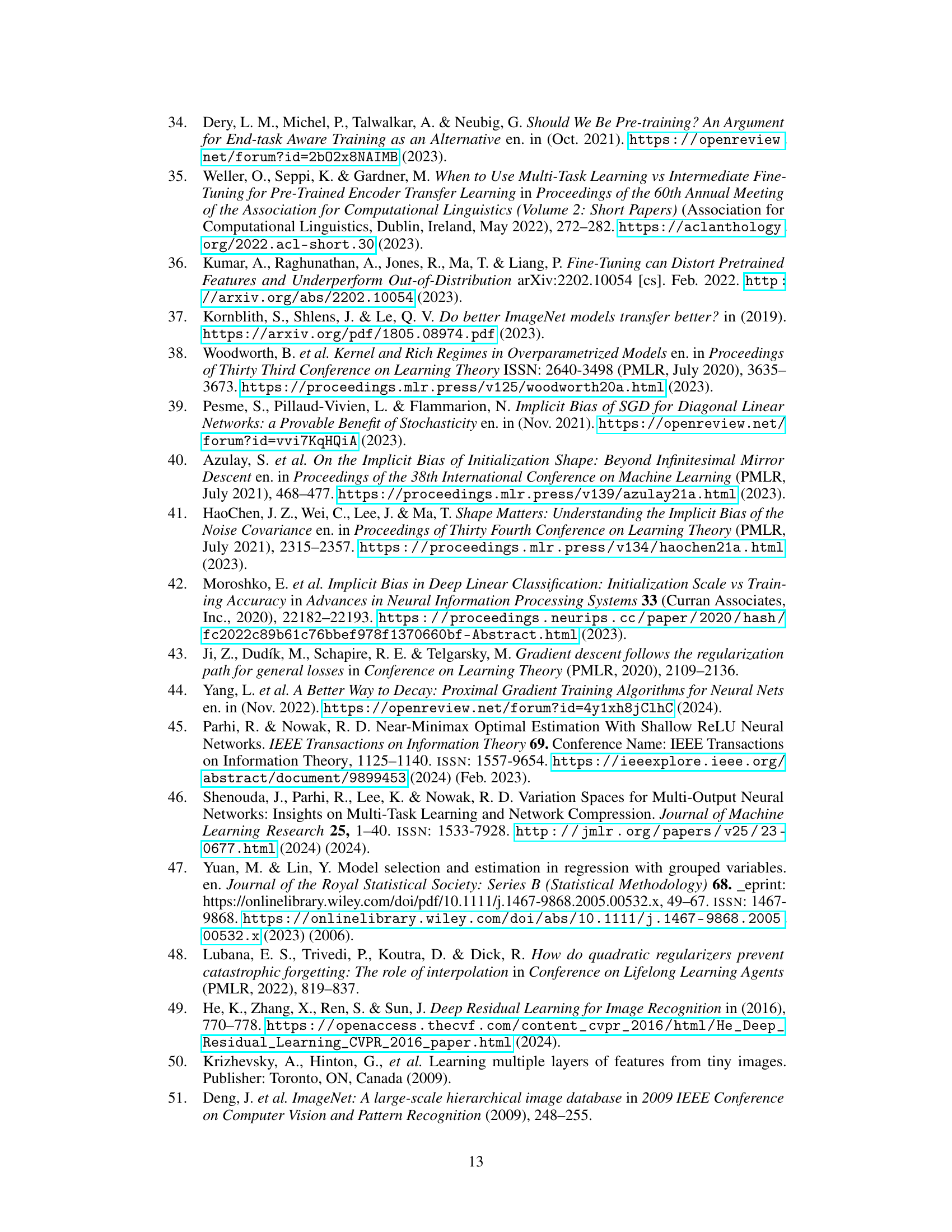

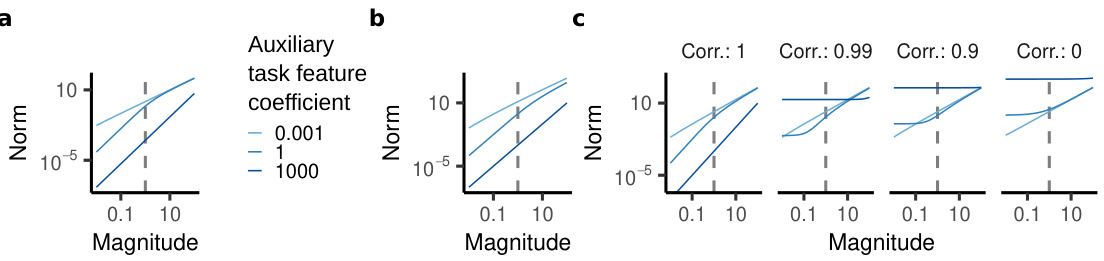

🔼 This figure compares the generalization performance of single-task learning (STL), multi-task learning (MTL), and pretraining+finetuning (PT+FT) under various conditions. Panels a and b show that MTL and PT+FT perform better than STL when the teacher network has a sparse representation. Panels c and d show that all three methods perform better when the teacher network shares features between auxiliary and main tasks. Panels e and f demonstrate that all three methods perform best when the teacher network has both shared and unique features.

read the caption

Figure 2: PT+FT and MTL benefit from feature sparsity and reuse. a,b, Generalization loss for a) diagonal linear networks and b) ReLU networks trained on a) a linear model with distinct active dimensions and b) a teacher network with distinct units between auxiliary and main task (STL: single-task learning). MTL and PT+FT benefit from a sparser teacher on the main task. c,d, Generalization loss for c) diagonal linear networks and d) ReLU networks trained on a teacher model sharing all features between the auxiliary and main task. PT+FT and MTL both generalize better than STL. e,f, Generalization loss for e) diagonal linear networks and f) ReLU networks trained on a teacher model with overlapping features. Networks benefit from feature sharing and can learn new features.

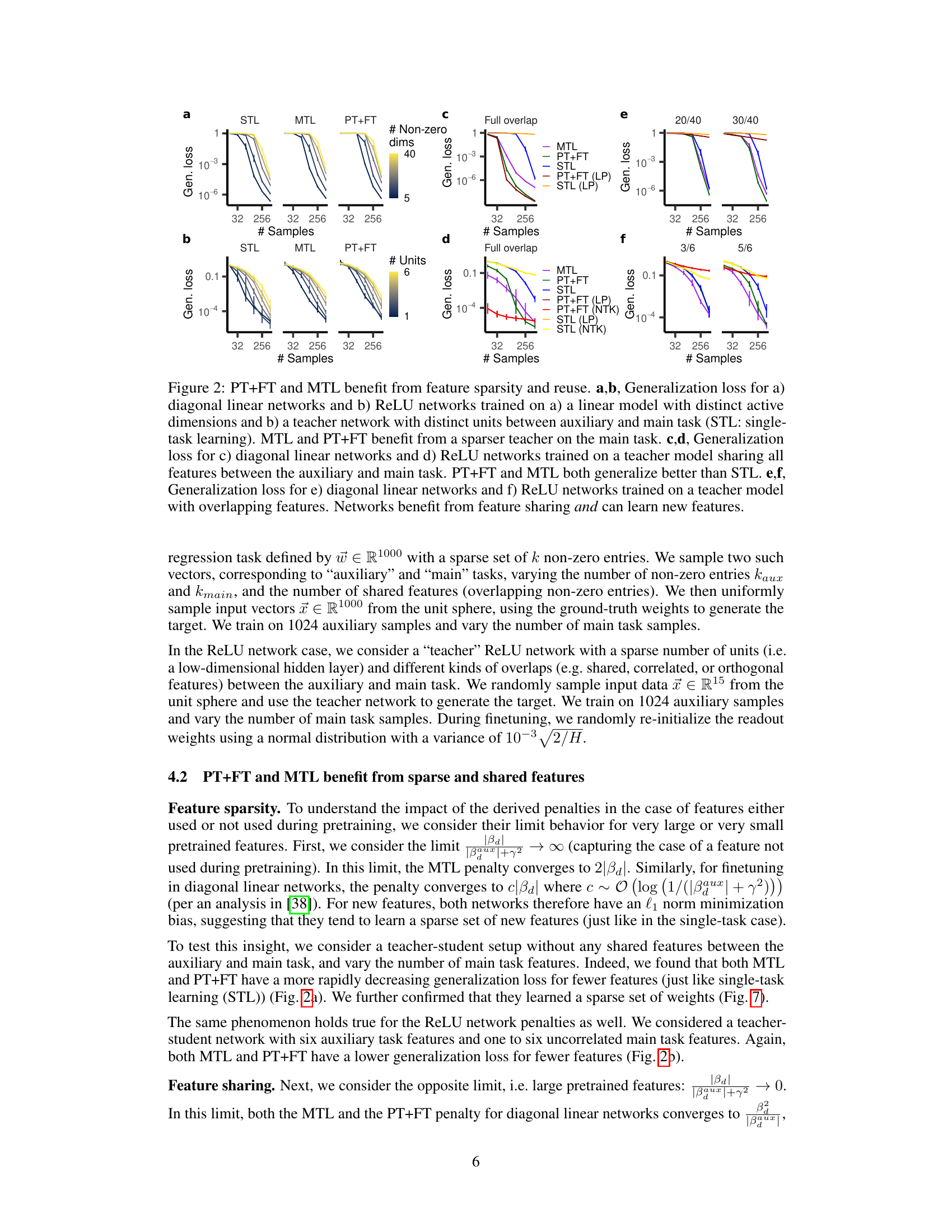

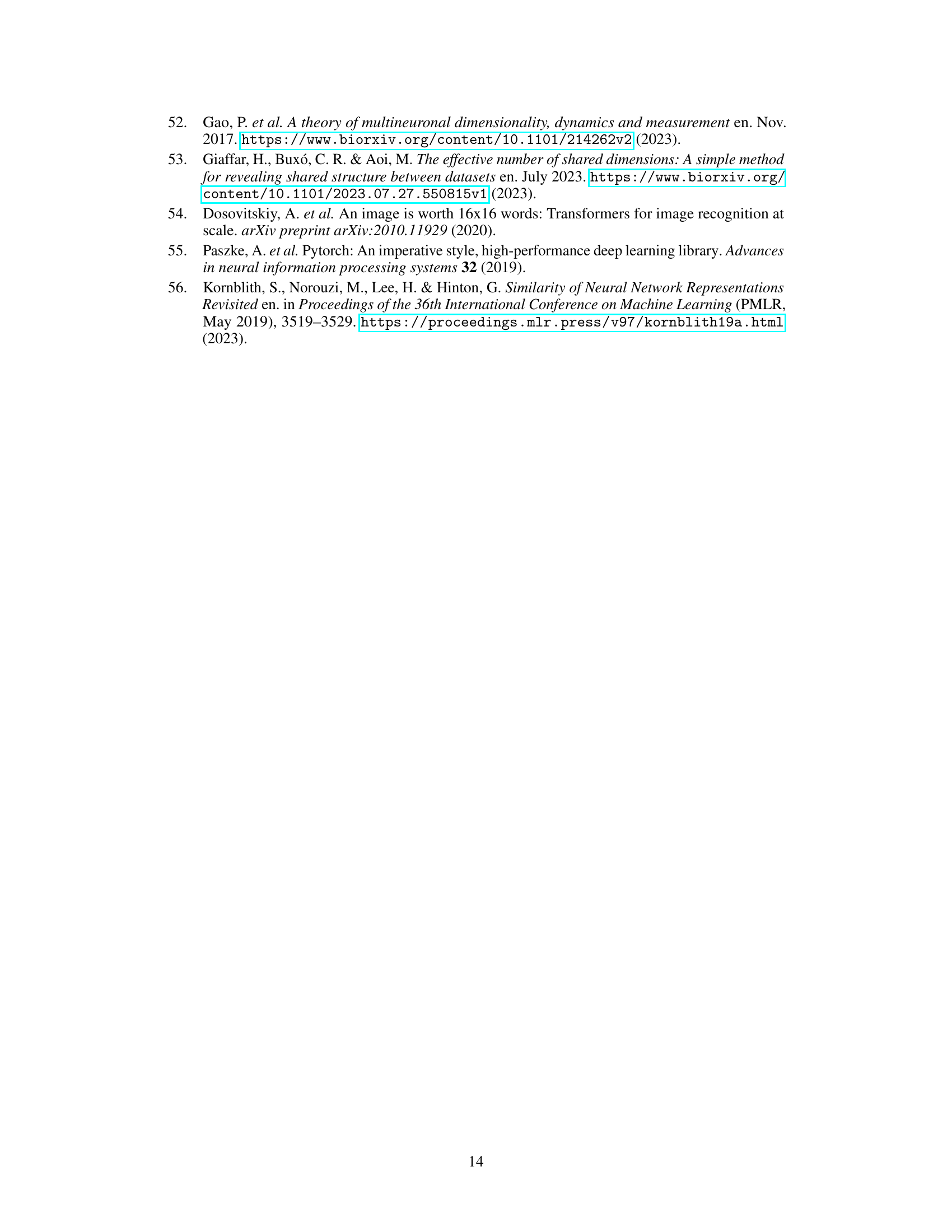

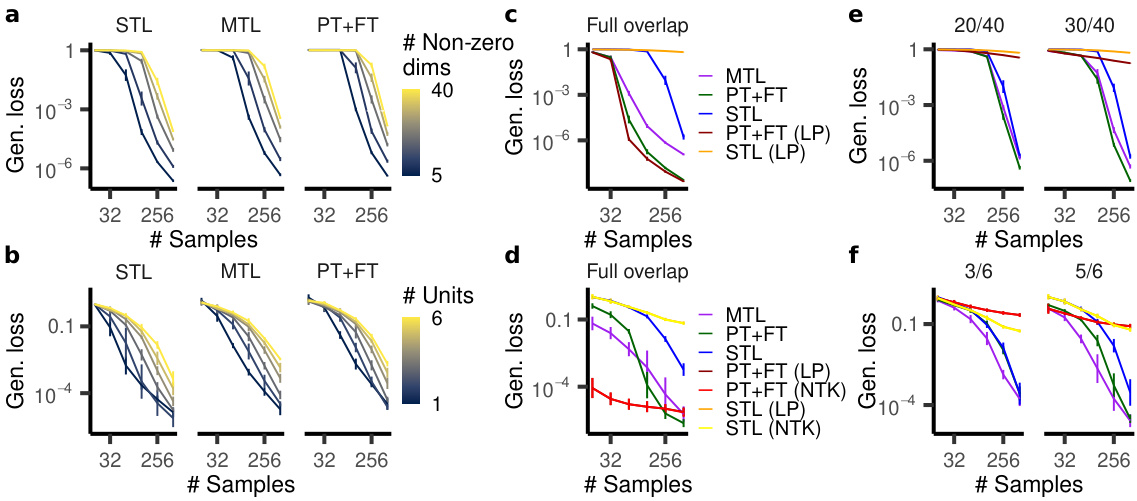

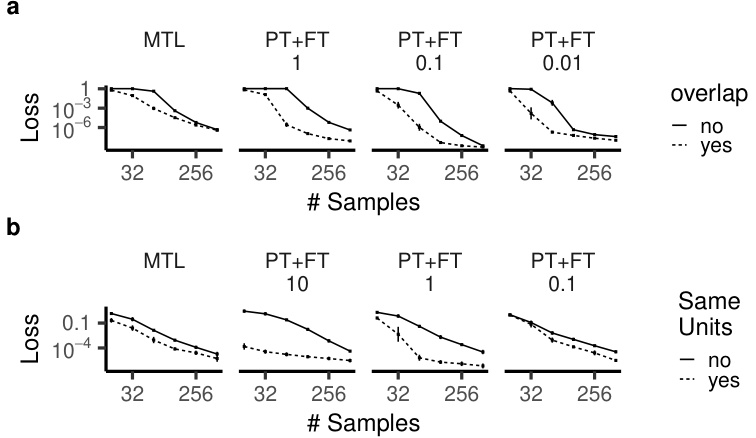

🔼 This figure shows that PT+FT, much more than MTL, exhibits a nested feature selection regime. The plots demonstrate how the order of the penalty and feature dependence change as a function of the auxiliary feature coefficient for both diagonal linear networks and ReLU networks. The generalization loss is also shown for different scenarios, including those where a subset of auxiliary task features are used in the main task and when weights are rescaled before finetuning. The results highlight the differences in how MTL and PT+FT reuse features, with PT+FT showing a strong preference for a sparse subset of pretrained features under certain conditions.

read the caption

Figure 3: PT+FT (much moreso than MTL) exhibits a nested feature selection regime. a–c, Diagonal linear networks. a, l-order/feature dependence plotted for βmain = 1 and varying the auxiliary task feature coefficient. b, Generalization loss for models trained on a teacher with 40 active units during the auxiliary task and a subset of those units active during the main task. c, Generalization loss for PT+FT models whose weights are rescaled by the factor in the parentheses before finetuning. d–f, ReLU networks. d, l-order/feature dependence plotted for the explicit finetuning and MTL penalties, for m = 1 and varying the auxiliary task feature coefficient. e, Generalization loss for models trained on a teacher network with six active units on the auxiliary task and a subset of those units on the main task. f, Generalization loss for PT+FT models whose weights are rescaled before finetuning.

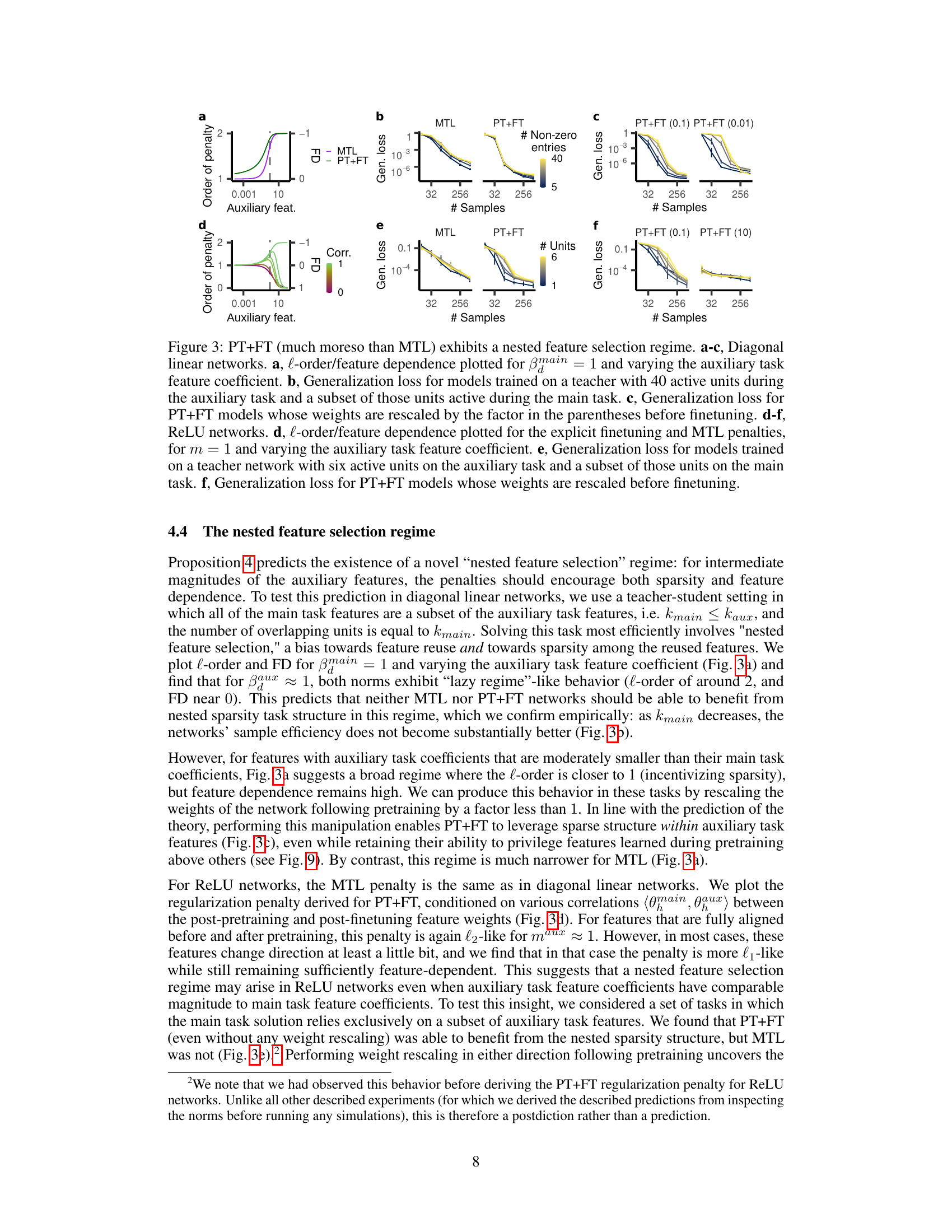

🔼 This figure shows that in ReLU networks, PT+FT outperforms both MTL and STL when the main and auxiliary tasks have correlated features. The advantage of PT+FT over STL is particularly noticeable when the features are highly correlated (cosine similarity of 0.9). However, this advantage disappears when the magnitude of the main task features is significantly smaller than that of the auxiliary task features, even with high correlation. MTL does not show the same trend. The result suggests that PT+FT is more sensitive to the similarity in direction and magnitude between main and auxiliary features than MTL.

read the caption

Figure 4: PT+FT, but not MTL, in ReLU networks benefits from correlated features. a, Generalization loss for main task features that are correlated (0.9 cosine similarity) with the auxiliary task features. PT+FT outperforms both MTL and STL. b, Generalization loss for main task features with varying correlation and magnitude (mag.). PT+FT only outperforms STL if the features are either identical in direction or identical in magnitude.

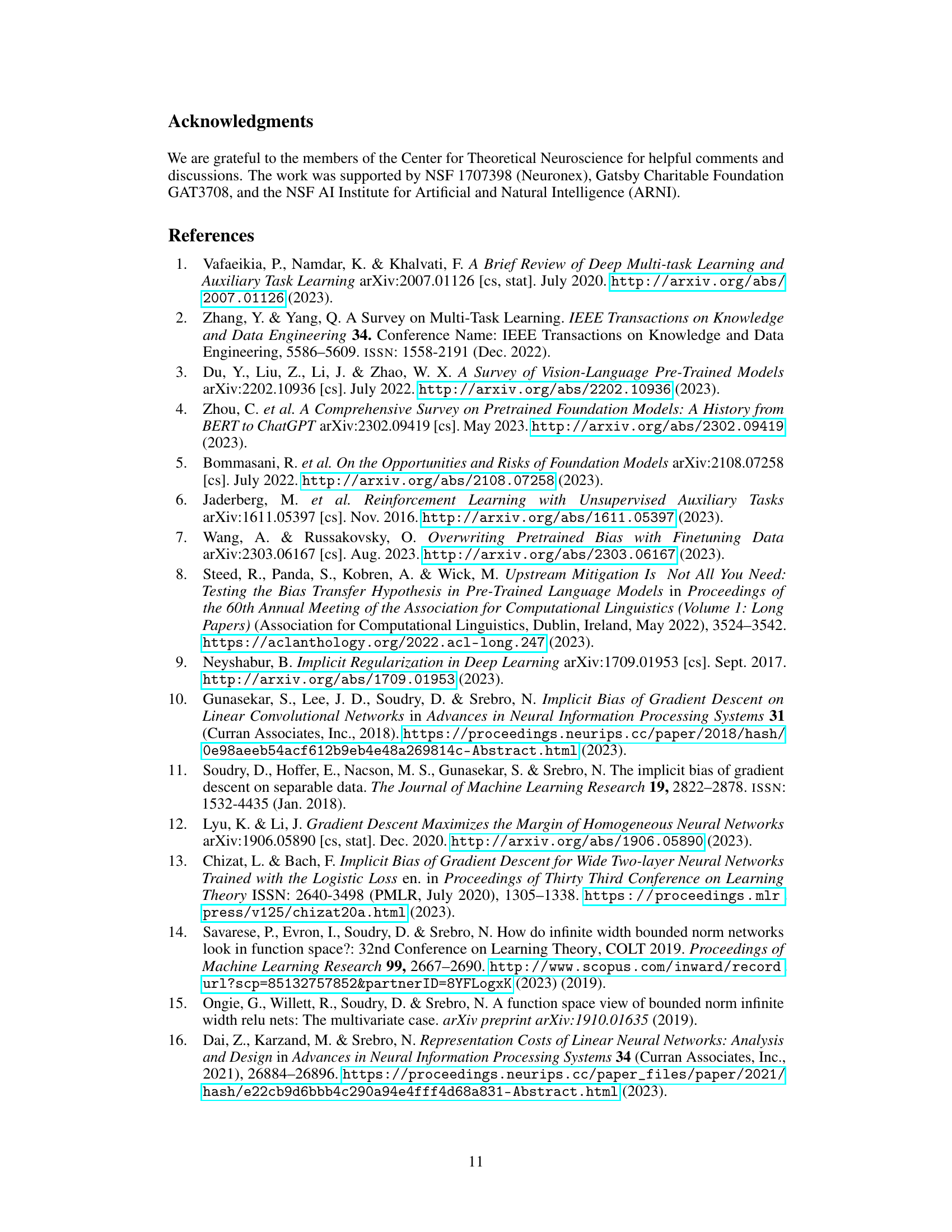

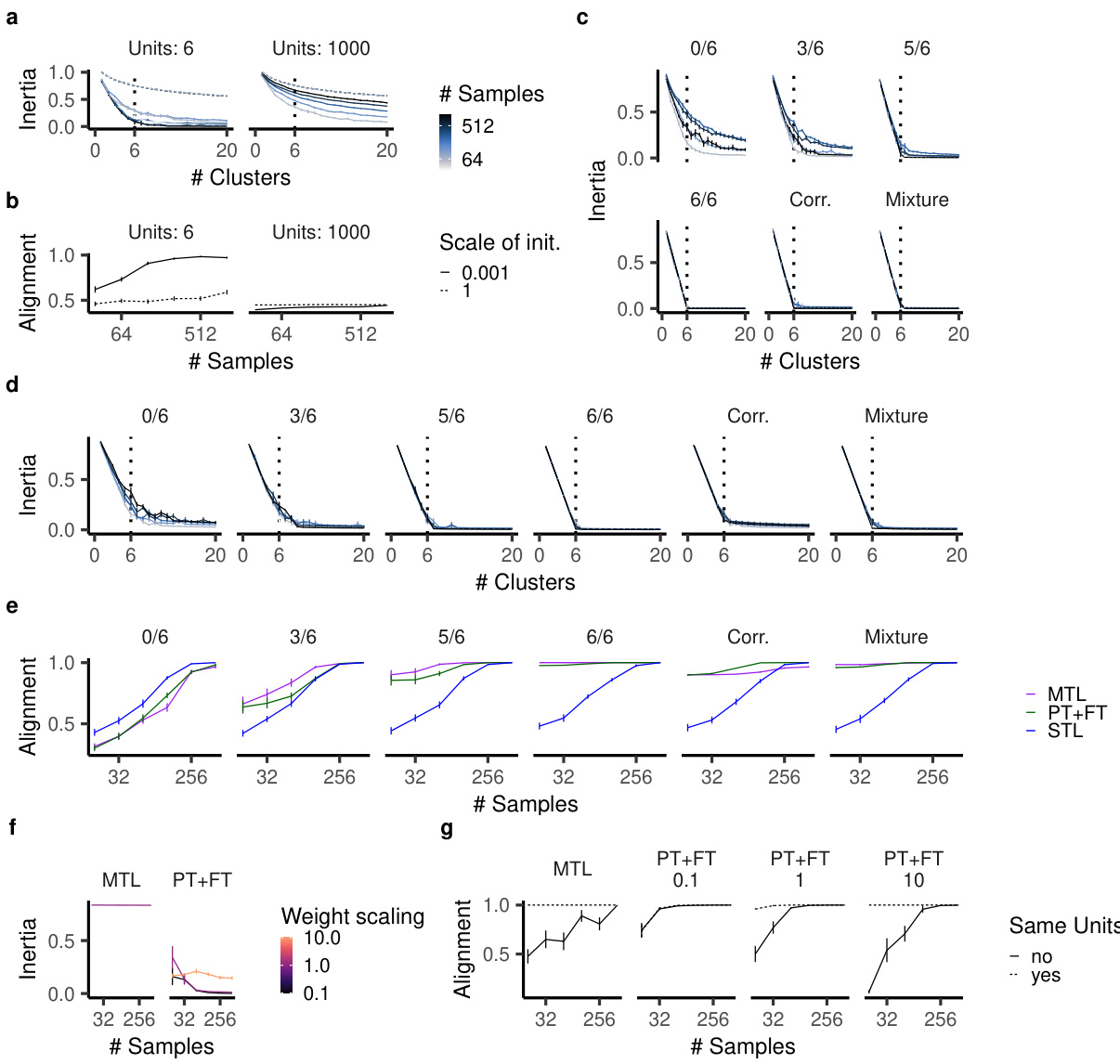

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments performed on deep neural networks using CIFAR-100 dataset. ResNet-18 and Vision Transformer (ViT) models were trained using multi-task learning (MTL), pre-training and fine-tuning (PT+FT), and single-task learning (STL). The impact of weight rescaling on PT+FT performance is also shown. Finally, the figure shows the participation ratio (PR) and effective number of shared dimensions (ENSD) in the network representations before and after finetuning, illustrating changes in dimensionality.

read the caption

Figure 5: Experiments in deep neural networks trained on CIFAR-100: a-c, ResNet-18, d-f, ViT. a,d, Accuracy for MTL, PT+FT, and STL in a) ResNet-18 and d) ViT. b,e Accuracy for PT+FT with weight rescaling in b) ResNet-18 and e) ViT. c,f The participation ration of c) ResNet-18's and f) ViT's layers before and after finetuning (PR Pre and PR Post) as well as their ENSD.

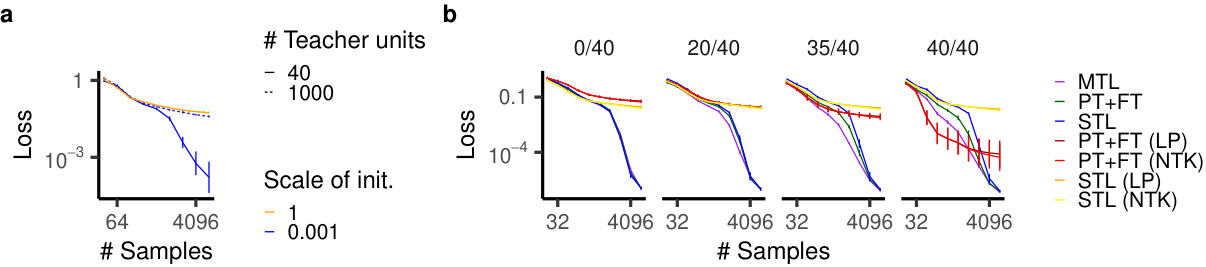

🔼 This figure shows the results of larger-scale teacher-student experiments. Panel (a) demonstrates generalization loss for shallow ReLU networks trained with various initializations and teacher networks with different numbers of units. Panel (b) illustrates how generalization loss changes depending on the number of overlapping features between main and auxiliary tasks for the same network architectures. The experiment setup is similar to Figure 2d, but with more teacher units and more data used for training.

read the caption

Figure 6: Larger-scale teacher-student experiments. a, Generalization loss of shallow ReLU networks trained on data from a ReLU teacher network. b, Generalization loss for different numbers of overlapping features (out of 40 total) between main and auxiliary tasks. NTK indicates the (lazy) tangent kernel solution. This is comparable to Fig. 2d, except with more teacher units and more data.

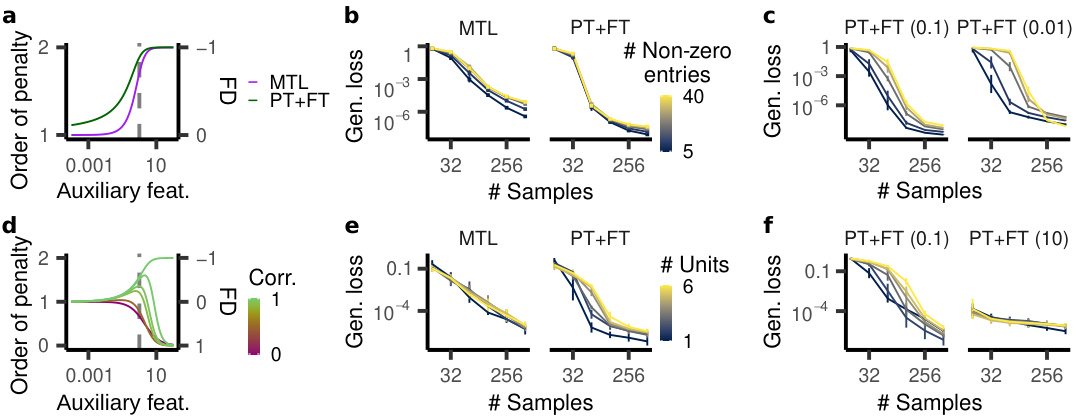

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments using teacher-student models to compare the performance of single-task learning (STL), multi-task learning (MTL), and pretraining+finetuning (PT+FT) under different conditions of feature overlap between the auxiliary and main tasks. Panels (a) and (b) demonstrate that when features are not shared, MTL and PT+FT perform better with sparser teacher networks (fewer non-zero dimensions or units). Panels (c) and (d) show that when all features are shared, both MTL and PT+FT outperform STL. Finally, panels (e) and (f) illustrate that when some features overlap, networks benefit from both shared features and the ability to learn new, task-specific features. This highlights the inductive biases of MTL and PT+FT towards feature reuse and sparsity.

read the caption

Figure 2: PT+FT and MTL benefit from feature sparsity and reuse. a,b, Generalization loss for a) diagonal linear networks and b) ReLU networks trained on a) a linear model with distinct active dimensions and b) a teacher network with distinct units between auxiliary and main task (STL: single-task learning). MTL and PT+FT benefit from a sparser teacher on the main task. c,d, Generalization loss for c) diagonal linear networks and d) ReLU networks trained on a teacher model sharing all features between the auxiliary and main task. PT+FT and MTL both generalize better than STL. e,f, Generalization loss for e) diagonal linear networks and f) ReLU networks trained on a teacher model with overlapping features. Networks benefit from feature sharing and can learn new features.

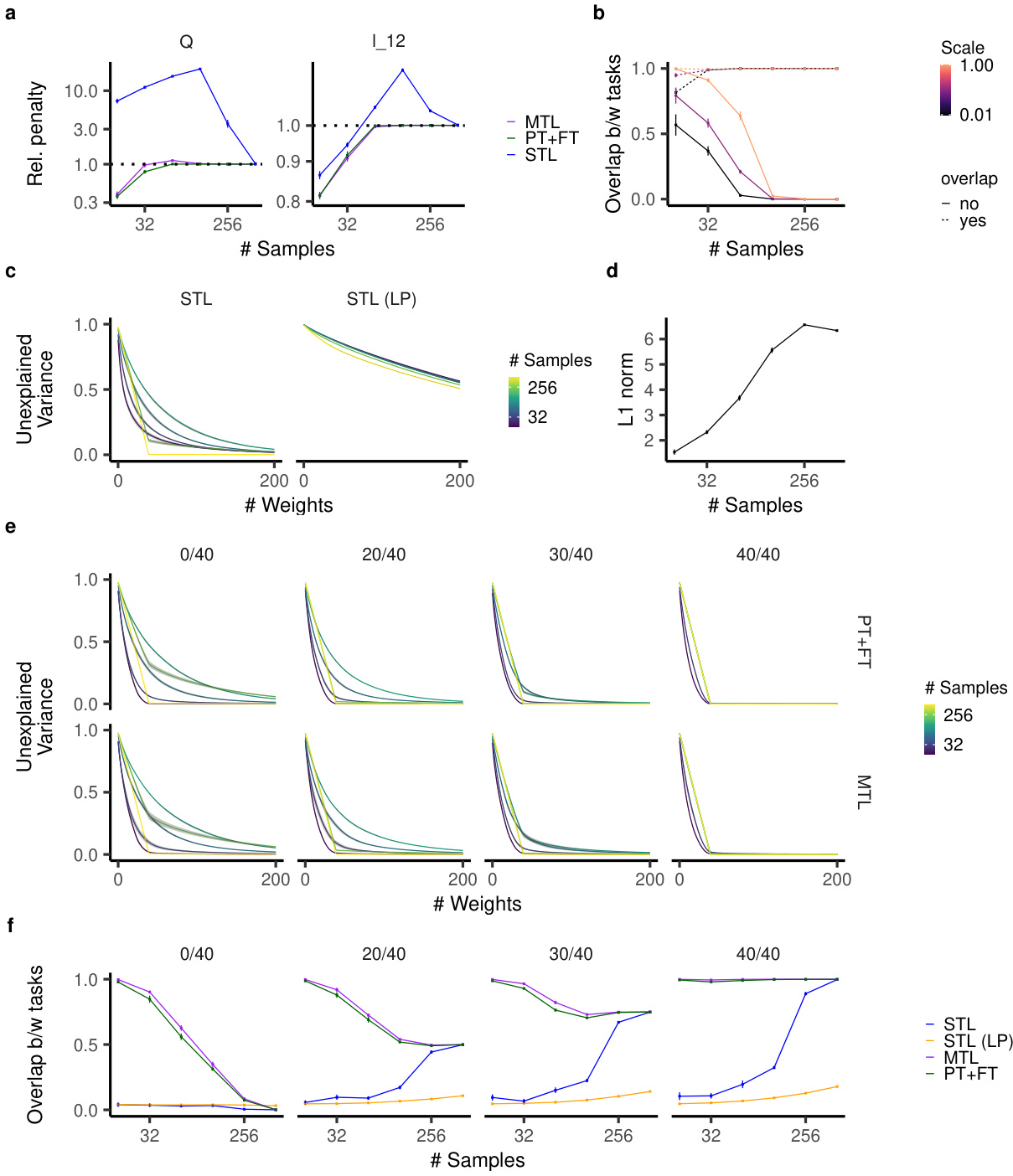

🔼 This figure analyzes the sparsity of learned ReLU network solutions using k-means clustering to determine the number of effective features learned. It shows how inertia (a measure of reconstruction error) changes with the number of clusters, demonstrating a bias towards sparse solutions in the rich regime (small initialization) for single-task learning. The alignment score measures how well the learned clusters align with the ground truth features, showing higher alignment with more samples and in the PT+FT regime. The figure also investigates this behavior in multi-task learning setups (MTL and PT+FT), showing that PT+FT tends towards slightly sparser solutions. Finally, it explores the impact of weight rescaling on feature sparsity and alignment, showcasing how this technique helps uncover the nested feature selection regime.

read the caption

Figure 8: Analysis of effective sparsity of learned ReLU network solutions. a Inertia (k-means reconstruction error for clustering of hidden-unit input weights) as a function of the number of clusters used for k-means, for different numbers of main task samples and ground-truth teacher network units, in single-task learning. b Alignment score – average alignment (across teacher units) of the best-aligned student network cluster uncovered via k-means. c, Inertia for networks trained using PT+FT for the tasks of Fig. 2d,e and Fig. 4a. d, Same as panel c but for networks trained with MTL. e, Alignment score for networks trained with MTL, PT+FT, and STL on the same tasks as in panels c and d. f Inertia (using k = 1 clusters) for networks trained on an auxiliary task that relies on only one ground-truth feature, which is one of the six ground-truth features used in the auxiliary task (as in Fig. 3e,f), using MTL or PT+FT with various rescaling factors applied to the weights prior to finetuning. g Alignment score for the networks and task in panel f.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing multi-task learning (MTL) and pre-training plus fine-tuning (PT+FT) on two types of tasks: (a) Diagonal linear networks with five main task features, where the main task features are either completely distinct from, partially overlapping with, or completely overlapping with the auxiliary task features. (b) ReLU networks trained on a teacher network with one feature, where again the main task features are either completely distinct from, partially overlapping with, or completely overlapping with the auxiliary task features. The results show that both MTL and PT+FT can benefit from some overlap between the main and auxiliary task features; however, the benefits are more pronounced for PT+FT, and the benefit decreases as the scaling factor decreases, indicating the importance of feature reuse in finetuning.

read the caption

Figure 9: Comparison between tasks with sparse main task features that are either subsets of the auxiliary task features or new features. Networks are trained with MTL or with PT+FT, potentially with rescaling (as indicated by the number). a, Diagonal linear networks trained on five main task features. b, ReLU networks trained on a teacher network with one feature. We see that MTL (to some extent) and PT+FT can benefit from such an overlap, but for small rescaling values, this benefit becomes smaller.

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on deep neural networks (ResNet-18 and ViT) trained on the CIFAR-100 dataset. It compares the performance of multi-task learning (MTL), pre-training plus fine-tuning (PT+FT), and single-task learning (STL). The impact of weight rescaling before fine-tuning on PT+FT is also assessed. Finally, the figure analyzes the participation ratio (PR) and effective number of shared dimensions (ENSD) of the network representations before and after finetuning to demonstrate the impact of the nested feature selection.

read the caption

Figure 5: Experiments in deep neural networks trained on CIFAR-100: a-c, ResNet-18, d-f, ViT. a,d, Accuracy for MTL, PT+FT, and STL in a) ResNet-18 and d) ViT. b,e Accuracy for PT+FT with weight rescaling in b) ResNet-18 and e) ViT. c,f The participation ration of c) ResNet-18's and f) ViT's layers before and after finetuning (PR Pre and PR Post) as well as their ENSD.

🔼 This figure shows the dimensionality of network representations before and after finetuning using participation ratio (PR) and effective number of shared dimensions (ENSD). Panel a shows PR for ReLU networks trained on a task with 6 units. Panel b shows the effect of weight rescaling on the PR during finetuning on a nested sparsity task. Panels c and d show PR, PR after finetuning, and ENSD for ReLU and ResNet18, respectively, demonstrating how weight rescaling affects dimensionality and shared dimensions between pre- and post-finetuning representations.

read the caption

Figure 11: Dimensionality of the network representations before and after finetuning. a, Participation ratio of the ReLU networks' internal representation after training on a task with six teacher units. b, Participation ratio of the network representation after finetuning on the nested sparsity task with different weight rescalings. c, Participation ratio before (left panel) and after finetuning (middle panel) and the effective number of shared dimensions between the two representations (right panel). Small weight scaling decreases the participation ratio after training. d, The same quantities for ResNet18 before and after finetuning (see also Fig. 5c).

Full paper#