TL;DR#

Transformers, despite their success, lack theoretical understanding, especially regarding the role of attention paths in generalization. Existing theories often rely on simplifying assumptions, neglecting the intricate interplay of attention paths across multiple layers and heads. This limits their ability to fully explain the effectiveness of Transformers.

This paper addresses these issues by developing a statistical mechanics theory of Bayesian learning in a deep multi-head self-attention network. This model, analytically tractable yet closely resembling Transformers, reveals a key mechanism: task-relevant kernel combination. This mechanism optimally weights different attention paths’ interactions based on task relevance, significantly enhancing generalization. The findings are validated through experiments, demonstrating improvements in generalization performance and enabling effective network size reduction by pruning less relevant attention heads.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Transformers. It provides a novel theoretical framework for understanding how Transformers generalize, moving beyond oversimplified assumptions. This opens new avenues for model optimization and interpretation, potentially leading to more efficient and interpretable AI models.

Visual Insights#

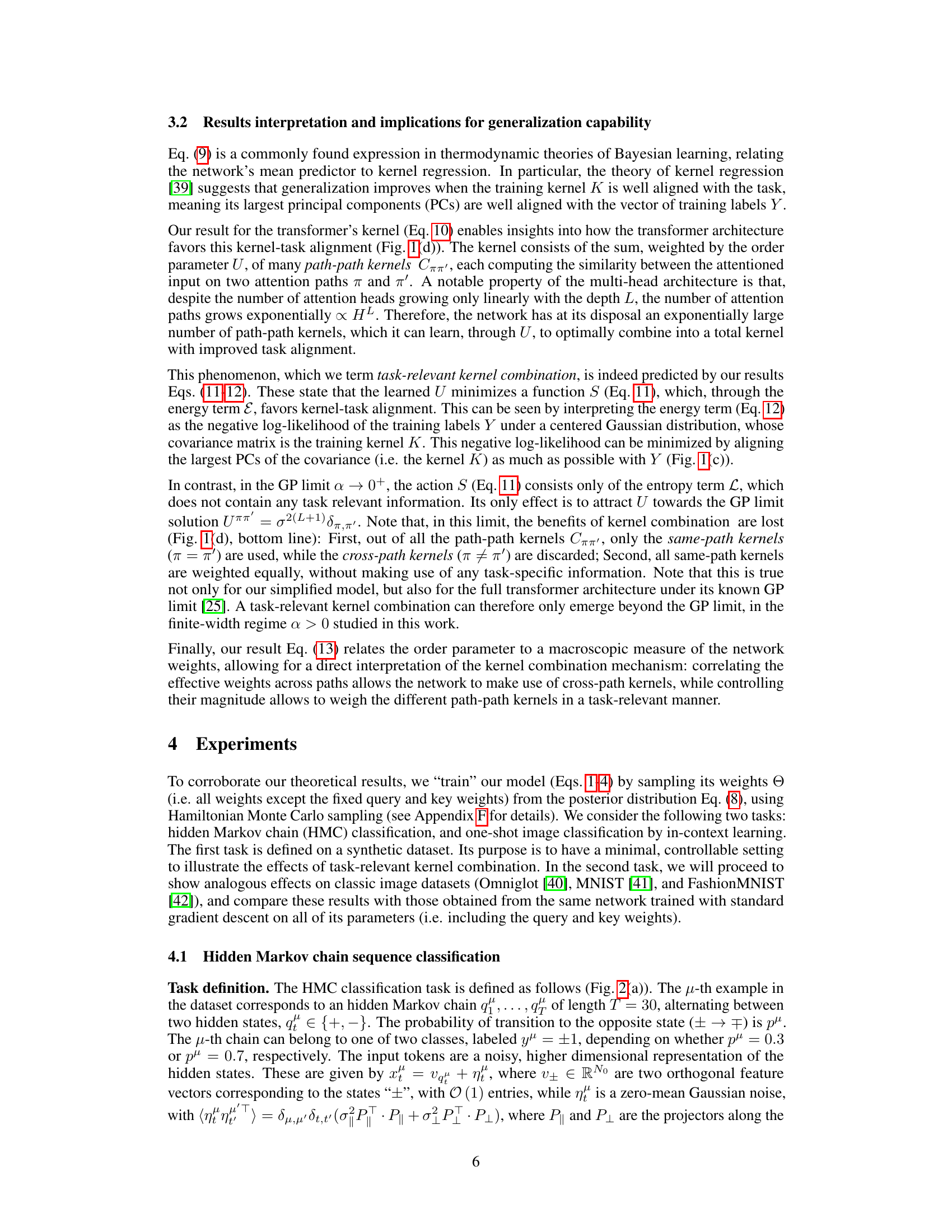

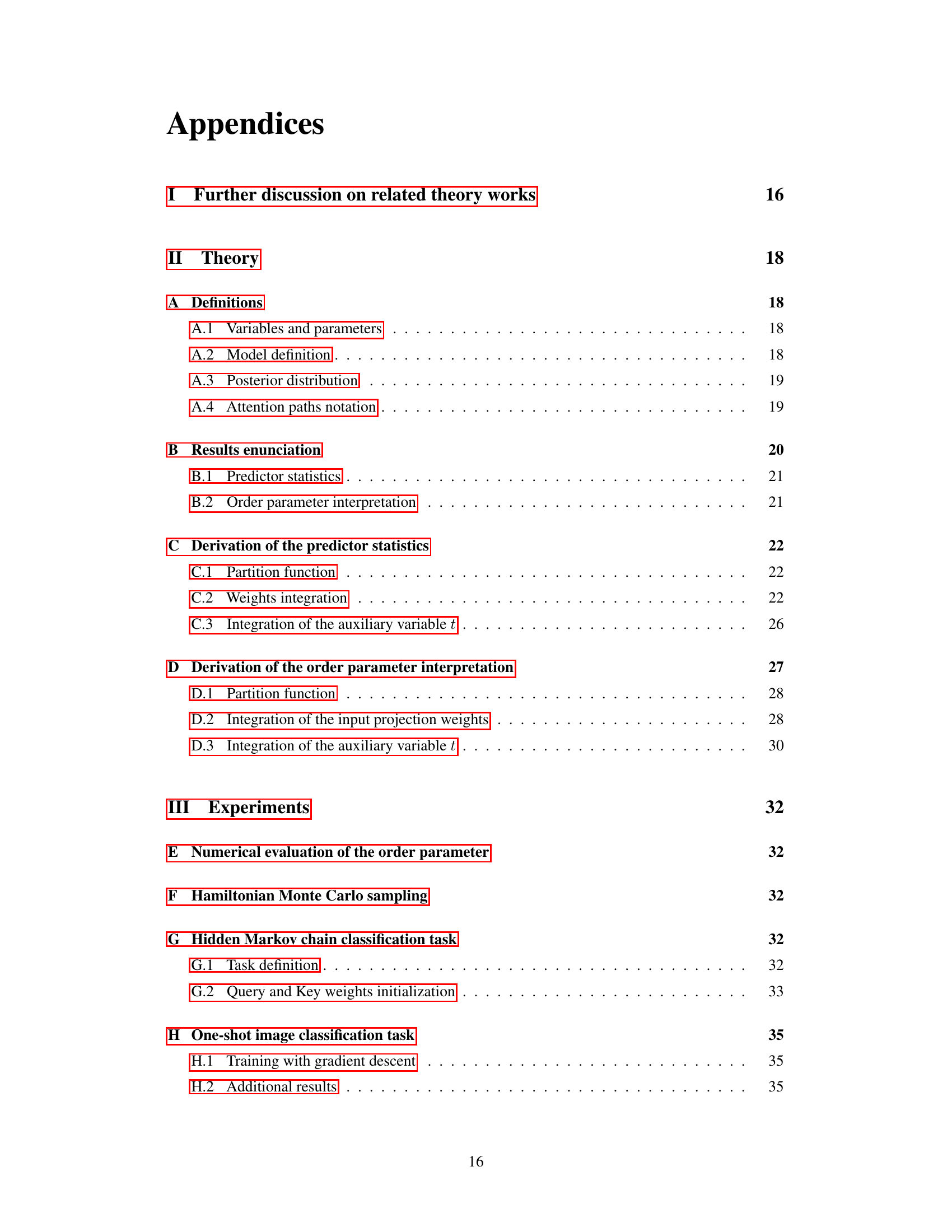

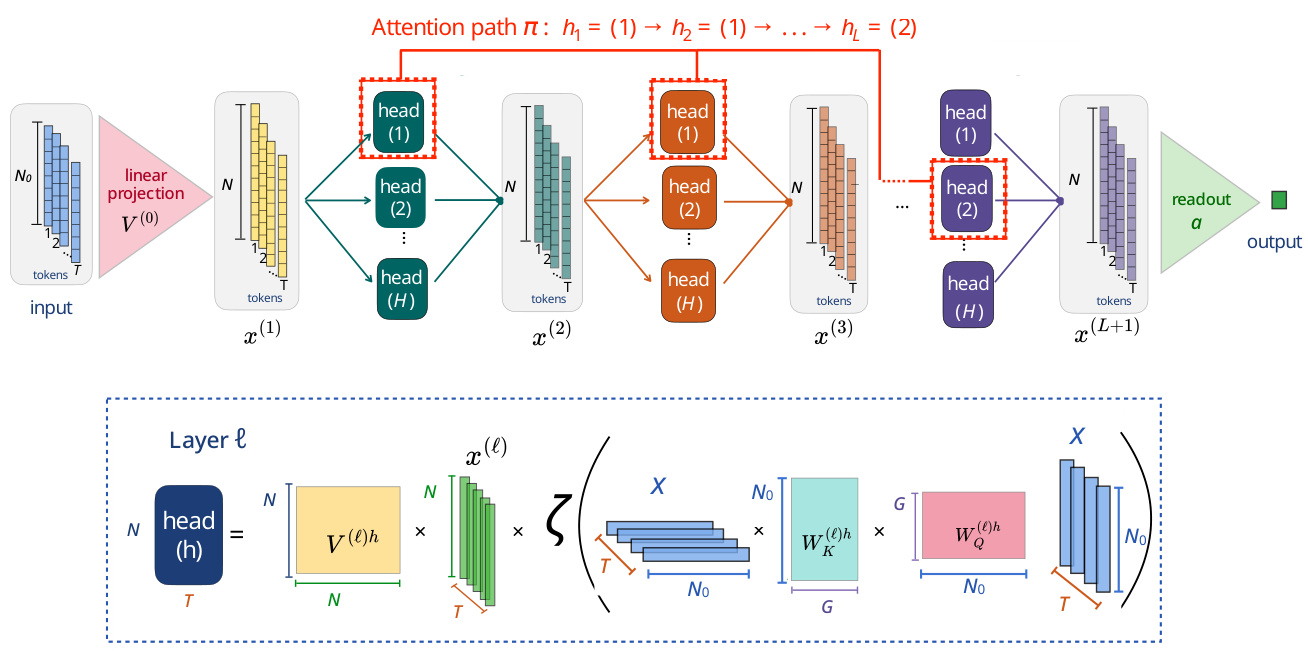

🔼 This figure illustrates the model and theoretical framework used in the paper. Panel (a) shows a schematic representation of the model, highlighting the concept of attention paths, which are sequences of attention heads across layers. Panel (b) explains how the order parameter assigns weights to these attention paths based on the overlap of their effective weights. Panel (c) displays the alignment of kernel principal components (PCs) with the task labels, contrasting the finite-width regime with the Gaussian process (GP) limit. Finally, panel (d) summarizes the key finding: the finite-width regime combines multiple path-path kernels to create a task-relevant kernel, improving generalization, in contrast to the GP limit, which discards cross-path kernels and weighs same-path kernels equally.

read the caption

Figure 1: Scheme of the model and theory (a) Scheme of the model in terms of attention paths. (b) The order parameter assigns to each pair of paths a weight, given by the overlap between the corresponding effective weights. (c) Alignment of the kernel PCs with the vector of task labels Y, in the finite-width (FW) vs GP regimes. (d) Kernel as the weighted sum of many path-path kernels. Task-relevant kernel combination occurs in the finite-width regime (FW), but not in the GP limit, in which cross-path kernels are discarded, and same-path kernels are equally weighted. The result is an improved kernel-task alignment in the finite-width regime (shown in (c)), enhancing generalization.

In-depth insights#

Attention Path Interplay#

The concept of ‘Attention Path Interplay’ in the context of transformer neural networks is a significant contribution to understanding their remarkable performance. The core idea revolves around the notion that information flows through the network along various pathways, created by the sequences of attention heads across multiple layers. These pathways, or attention paths, are not independent; their interactions are crucial. The research likely explores how these paths collectively contribute to the model’s predictions, showing that the interplay between different attention paths enhances the model’s generalization ability. This is probably achieved by a task-relevant kernel combination mechanism, which dynamically weights different attention paths according to their importance for the specific task, effectively creating a more informative representation of the input. This nuanced understanding offers valuable insights for both improving model performance and interpreting their internal decision-making processes, potentially leading to more efficient and interpretable network architectures.

Bayesian Learning Theory#

Bayesian learning theory offers a powerful framework for understanding and improving machine learning models. It provides a principled way to incorporate prior knowledge and uncertainty into the learning process, leading to more robust and generalizable models. In the context of deep learning, Bayesian approaches address the challenges of overfitting and model selection by treating model parameters as probability distributions rather than fixed point estimates. This probabilistic perspective allows for quantifying uncertainty in predictions, which is crucial for applications like medical diagnosis and autonomous driving where confidence levels are essential. Bayesian methods excel at handling limited data scenarios, naturally incorporating prior information to compensate for data scarcity. However, practical application of Bayesian methods can be computationally expensive, often requiring approximation techniques like variational inference or Markov chain Monte Carlo. Therefore, research focuses on developing efficient algorithms for Bayesian deep learning that balance accuracy and computational tractability. The theoretical analysis within Bayesian learning provides insights into model behavior and generalization capabilities, guiding improvements in model architecture and training techniques.

Kernel Combination#

The concept of ‘Kernel Combination’ in the context of the provided research paper revolves around the idea that a transformer network’s predictive ability stems from a weighted sum of many path-path kernels. Each kernel represents the similarity between pairs of attention paths, which are specific sequences of attention head activations across the network’s layers. The key insight is that this weighted summation isn’t uniform; instead, a task-relevant mechanism dynamically weights these kernels, effectively aligning the overall kernel with the task labels. This process, beyond a simple averaging, enhances generalization performance. The paper suggests that this mechanism emerges only when considering networks of finite width (the finite-width thermodynamic limit), unlike the infinite-width limit where this path interplay is lost. This finite-width behavior allows for task-relevant weighting and path correlation, crucial for improved generalization. Therefore, the ‘Kernel Combination’ represents a significant theoretical advance, moving beyond previous Gaussian process approximations of transformer networks and offering a deeper understanding of their remarkable empirical success.

Model Generalization#

Model generalization, the ability of a trained model to perform well on unseen data, is a critical aspect of machine learning. The paper investigates generalization in the context of transformer networks, focusing on the interplay of attention paths. The key finding is that enhanced generalization stems from a task-relevant kernel combination mechanism, arising in finite-width networks but absent in the infinite-width Gaussian process limit. This mechanism enables the network to effectively weight and correlate various attention paths, aligning the overall kernel with the task labels. This is not simply a matter of weighting individual paths, but rather involves a complex interplay and correlation between them. The improved alignment improves the network’s ability to generalize to unseen data, leading to better performance. Experiments confirm the theoretical findings, demonstrating the benefit of this mechanism in both synthetic and real-world sequence classification tasks. The study also reveals practical implications, allowing for efficient network pruning based on path relevance, further highlighting the importance of understanding the interplay of attention paths in transformer architectures.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could involve extending the theoretical framework to encompass more realistic transformer architectures. This includes addressing the non-linearity of the value weights and the dependence of attention on previous layer activations, both crucial aspects of standard transformers absent in the current model. Another important direction would be to investigate the interplay between the learned query/key weights and attention path dynamics. The current theory fixes query/key weights, limiting its scope. Investigating how these weights influence path selection and the kernel combination mechanism would provide crucial insights into transformer learning. Finally, applying the kernel combination insights to practical model compression techniques warrants further study. The theoretical understanding of task-relevant path weighting could lead to advanced pruning strategies surpassing naive head or layer pruning approaches, optimizing efficiency without substantial performance loss. Exploring connections with other areas of deep learning, such as inductive biases and generalization, is also promising.

More visual insights#

More on figures

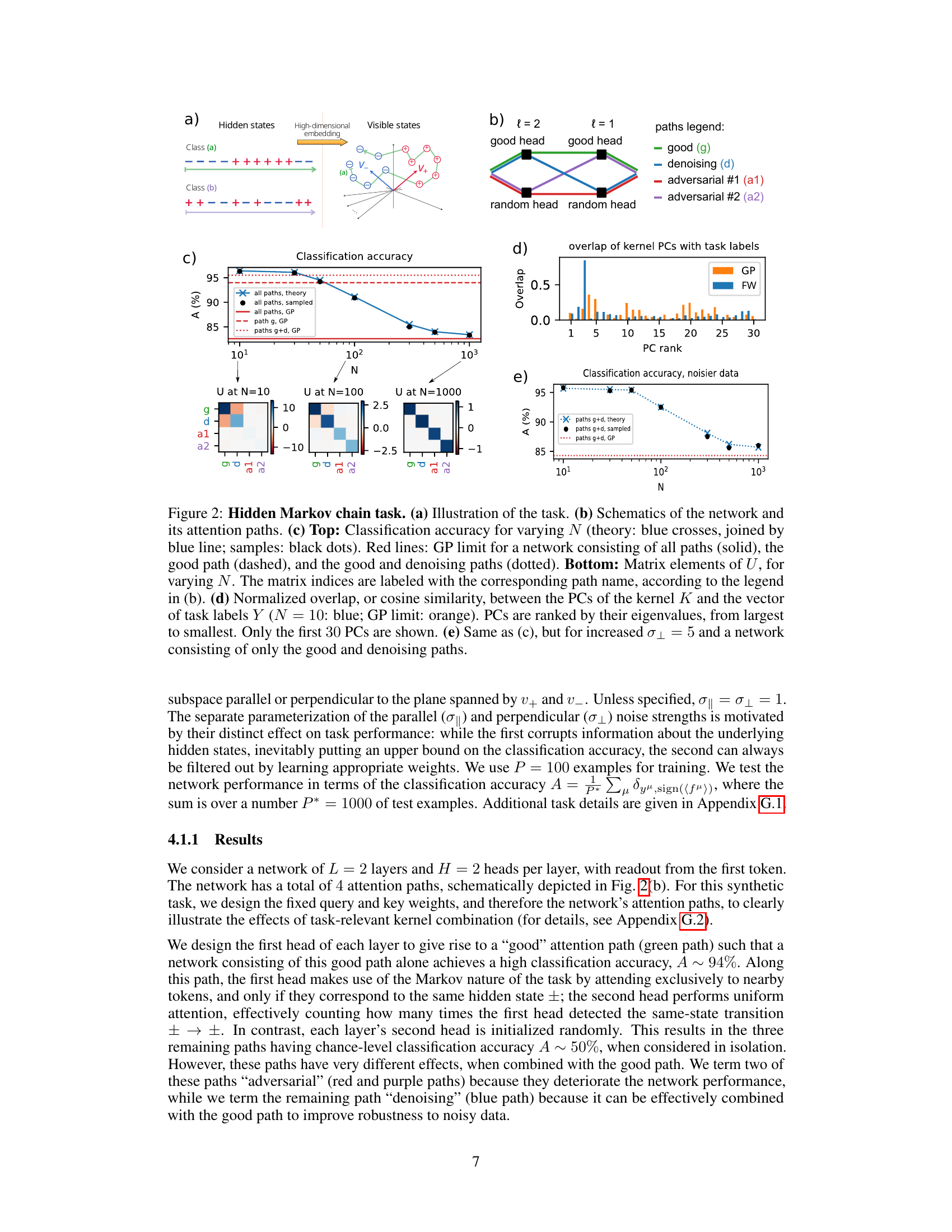

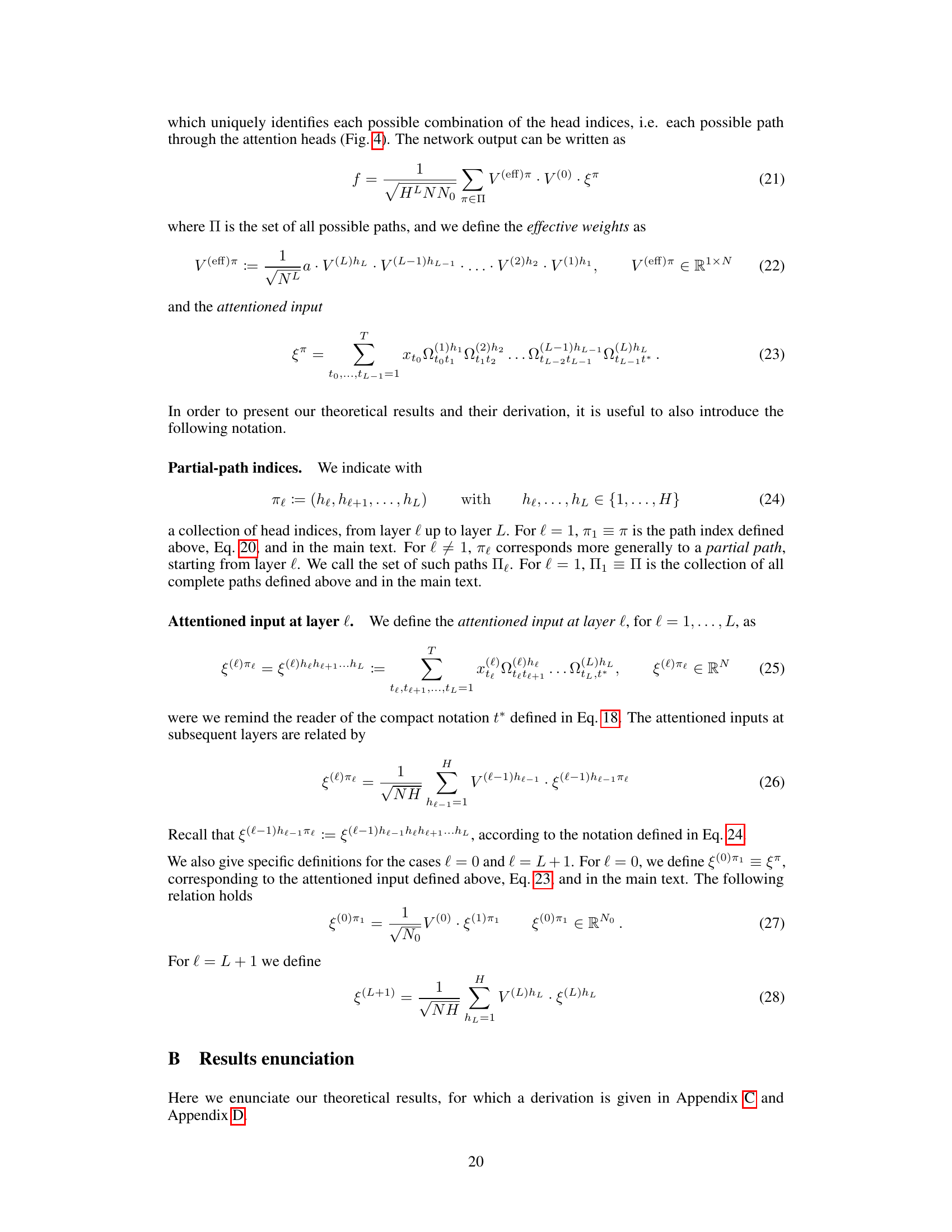

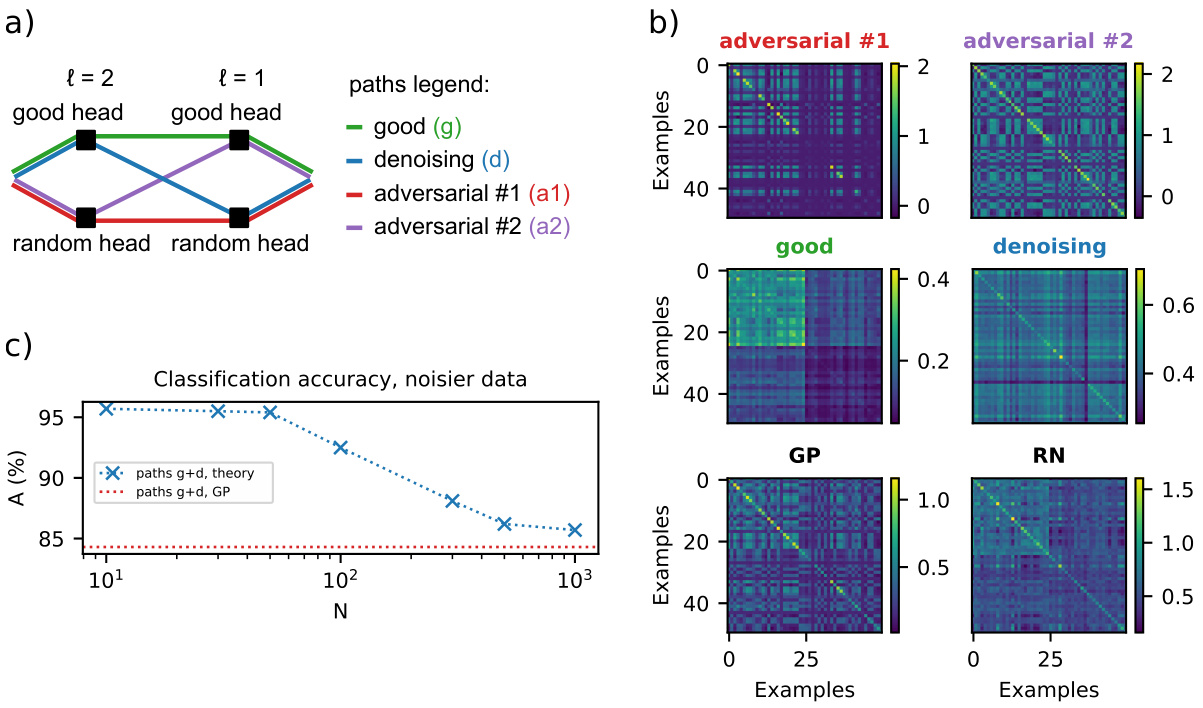

🔼 This figure illustrates the results of a hidden Markov chain classification task. Panel (a) shows a schematic of the task, illustrating the hidden and visible states of the Markov chain. Panel (b) shows a schematic of the network architecture with the different attention paths. Panel (c) compares the classification accuracy of the network for different network widths (N), contrasting the theoretical predictions with empirical results obtained from sampling. The bottom half of (c) shows the order parameter (U) for different network widths, visualizing the interplay between attention paths. Panel (d) displays the overlap between kernel principal components (PCs) and task labels, highlighting the alignment improvement in the finite-width regime. Finally, panel (e) repeats the experiment in (c) but with increased noise and a reduced number of paths.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hidden Markov chain task. (a) Illustration of the task. (b) Schematics of the network and its attention paths. (c) Top: Classification accuracy for varying N (theory: blue crosses, joined by blue line; samples: black dots). Red lines: GP limit for a network consisting of all paths (solid), the good path (dashed), and the good and denoising paths (dotted). Bottom: Matrix elements of U, for varying N. The matrix indices are labeled with the corresponding path name, according to the legend in (b). (d) Normalized overlap, or cosine similarity, between the PCs of the kernel K and the vector of task labels Y (N = 10: blue; GP limit: orange). PCs are ranked by their eigenvalues, from largest to smallest. Only the first 30 PCs are shown. (e) Same as (c), but for increased στ = 5 and a network consisting of only the good and denoising paths.

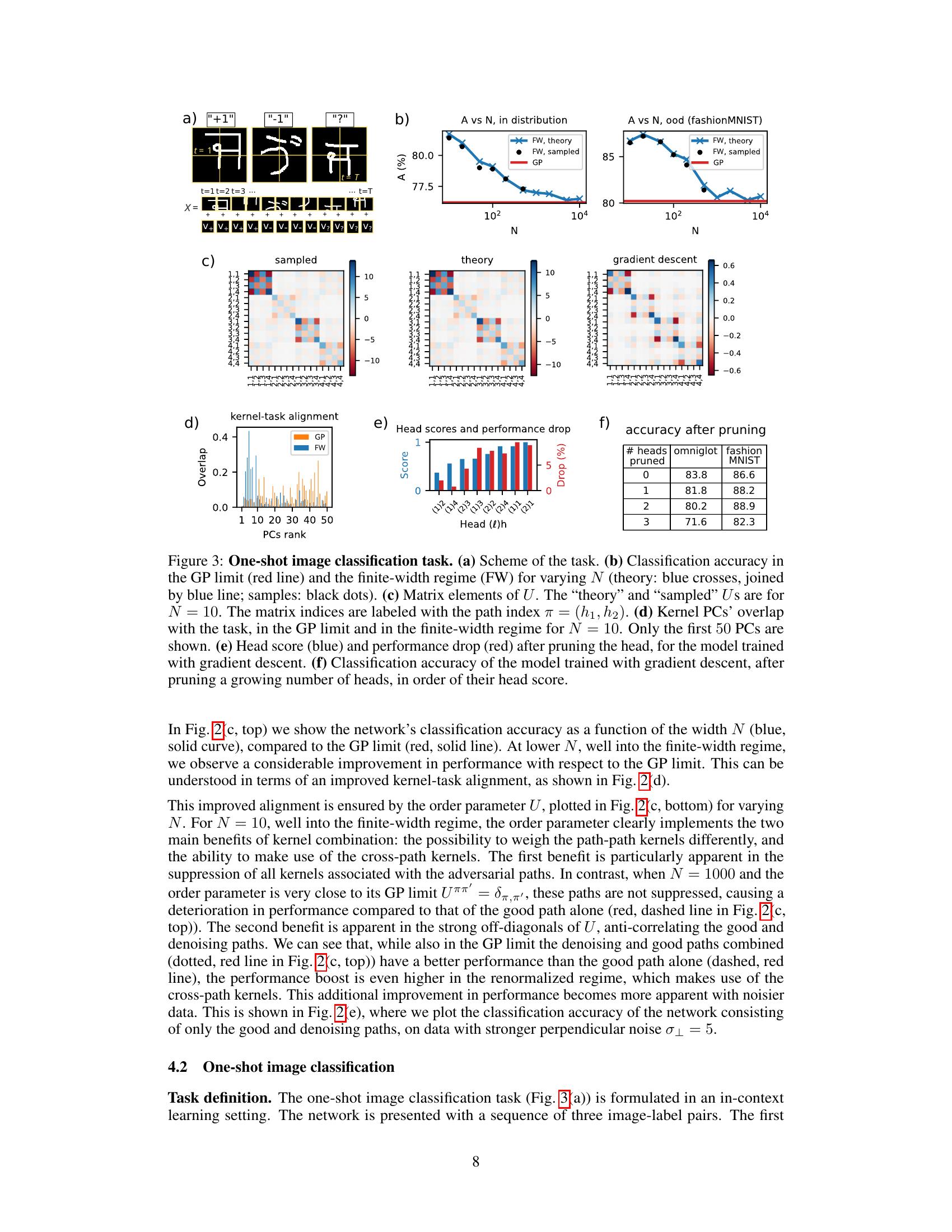

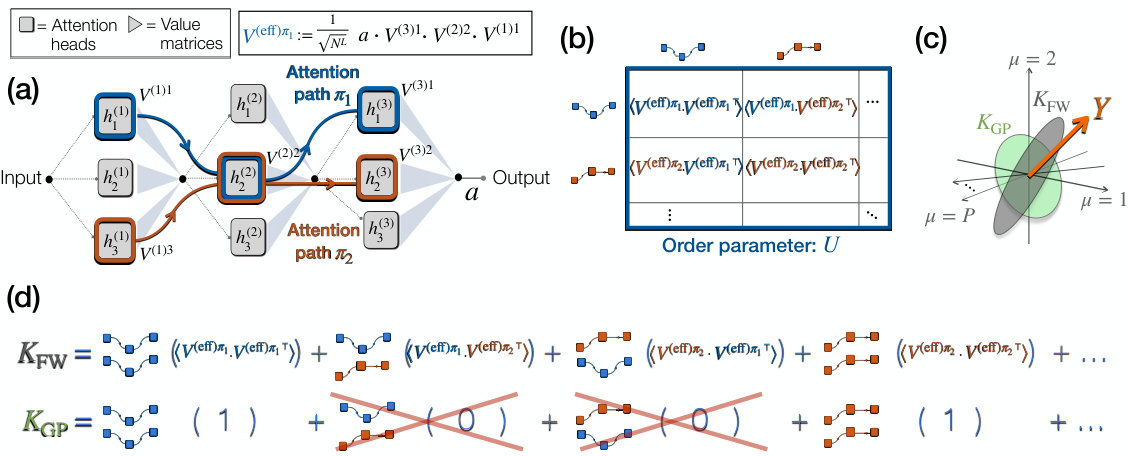

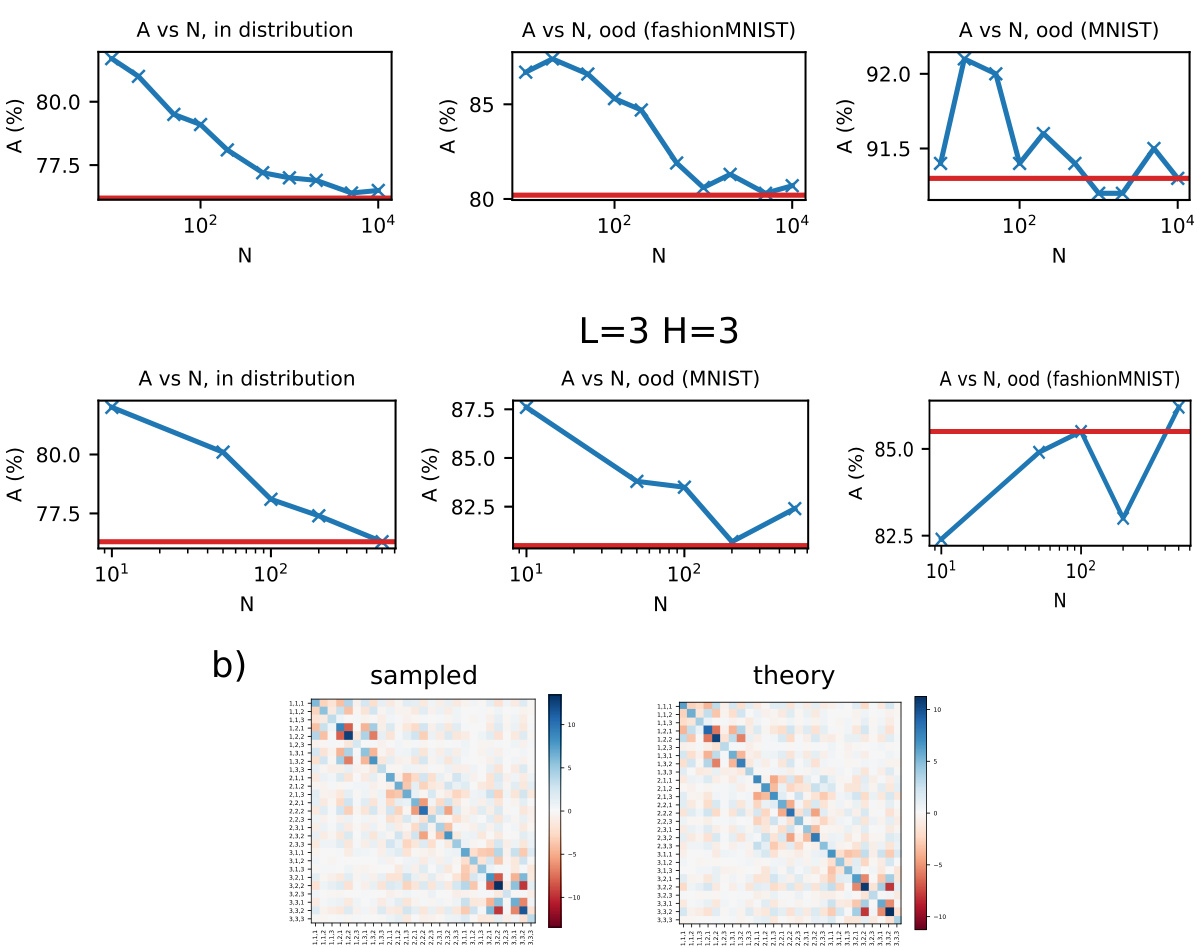

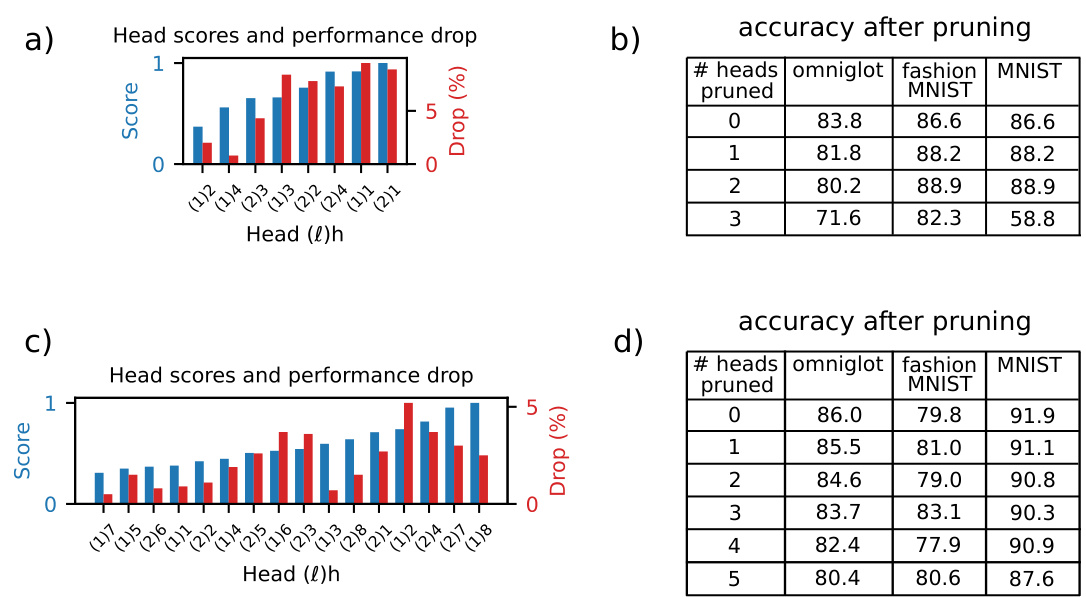

🔼 This figure presents the results of the one-shot image classification experiments. It shows the classification accuracy for varying network widths N in both the GP limit and the finite-width regime. The figure also depicts the elements of the order parameter U, illustrating the interplay of attention paths. Kernel principal components (PCs) are visualized, highlighting the kernel-task alignment. Finally, the figure shows the head scores and performance drop after pruning, demonstrating the effectiveness of head pruning for model reduction.

read the caption

Figure 3: One-shot image classification task. (a) Scheme of the task. (b) Classification accuracy in the GP limit (red line) and the finite-width regime (FW) for varying N (theory: blue crosses, joined by blue line; samples: black dots). (c) Matrix elements of U. The 'theory' and 'sampled' Us are for N = 10. The matrix indices are labeled with the path index π = (h1, h2). (d) Kernel PCs' overlap with the task, in the GP limit and in the finite-width regime for N = 10. Only the first 50 PCs are shown. (e) Head score (blue) and performance drop (red) after pruning the head, for the model trained with gradient descent. (f) Classification accuracy of the model trained with gradient descent, after pruning a growing number of heads, in order of their head score.

🔼 This figure illustrates the model and theory presented in the paper. Panel (a) shows a schematic representation of the model, highlighting the concept of attention paths as information pathways through the attention heads across different layers. Panel (b) explains the role of the order parameter in assigning weights to pairs of attention paths based on their overlap, essentially emphasizing the interaction between these paths. Panel (c) compares the alignment of principal components (PCs) of the kernel with task labels in the finite-width (FW) and Gaussian process (GP) regimes. The FW regime exhibits better alignment due to the interplay of attention paths. Finally, panel (d) demonstrates how the kernel is composed of multiple path-path kernels that are combined in the FW regime to improve generalization performance, which is not the case in the GP limit.

read the caption

Figure 1: Scheme of the model and theory (a) Scheme of the model in terms of attention paths. (b) The order parameter assigns to each pair of paths a weight, given by the overlap between the corresponding effective weights. (c) Alignment of the kernel PCs with the vector of task labels Y, in the finite-width (FW) vs GP regimes. (d) Kernel as the weighted sum of many path-path kernels. Task-relevant kernel combination occurs in the finite-width regime (FW), but not in the GP limit, in which cross-path kernels are discarded, and same-path kernels are equally weighted. The result is an improved kernel-task alignment in the finite-width regime (shown in (c)), enhancing generalization.

🔼 This figure shows results from a Hidden Markov Chain classification task. Panel (a) illustrates the task’s setup. Panel (b) provides a schematic of the network architecture and its attention paths. Panel (c) presents a comparison of classification accuracy (top) and order parameter (bottom) across different network widths (N). Panel (d) displays the alignment between kernel principal components (PCs) and task labels. Panel (e) repeats the analysis of panel (c) but under noisier conditions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hidden Markov chain task. (a) Illustration of the task. (b) Schematics of the network and its attention paths. (c) Top: Classification accuracy for varying N (theory: blue crosses, joined by blue line; samples: black dots). Red lines: GP limit for a network consisting of all paths (solid), the good path (dashed), and the good and denoising paths (dotted). Bottom: Matrix elements of U, for varying N. The matrix indices are labeled with the corresponding path name, according to the legend in (b). (d) Normalized overlap, or cosine similarity, between the PCs of the kernel K and the vector of task labels Y (N = 10: blue; GP limit: orange). PCs are ranked by their eigenvalues, from largest to smallest. Only the first 30 PCs are shown. (e) Same as (c), but for increased στ = 5 and a network consisting of only the good and denoising paths.

🔼 This figure shows results for the hidden Markov chain sequence classification task. It includes schematics of the task and network, classification accuracy for different network widths (N), and the order parameter U, which captures the interplay of attention paths. The plots show how classification accuracy improves in the finite-width regime (N>0) over the Gaussian Process (GP) limit, illustrating task-relevant kernel combination via attention paths.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hidden Markov chain task. (a) Illustration of the task. (b) Schematics of the network and its attention paths. (c) Top: Classification accuracy for varying N (theory: blue crosses, joined by blue line; samples: black dots). Red lines: GP limit for a network consisting of all paths (solid), the good path (dashed), and the good and denoising paths (dotted). Bottom: Matrix elements of U, for varying N. The matrix indices are labeled with the corresponding path name, according to the legend in (b). (d) Normalized overlap, or cosine similarity, between the PCs of the kernel K and the vector of task labels Y (N = 10: blue; GP limit: orange). PCs are ranked by their eigenvalues, from largest to smallest. Only the first 30 PCs are shown. (e) Same as (c), but for increased στ = 5 and a network consisting of only the good and denoising paths.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments on a synthetic Hidden Markov Chain classification task. Panel (a) illustrates the task setup. Panel (b) provides a schematic of the network architecture and the different attention paths through the network. Panel (c) displays classification accuracy as a function of network width (N), comparing theoretical predictions to empirical results from sampled networks. It also shows the elements of the order parameter U for different N values. Panel (d) shows the alignment between kernel principal components (PCs) and task labels. Finally, panel (e) replicates panel (c) but with increased noise and only the ‘good’ and ‘denoising’ paths active.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hidden Markov chain task. (a) Illustration of the task. (b) Schematics of the network and its attention paths. (c) Top: Classification accuracy for varying N (theory: blue crosses, joined by blue line; samples: black dots). Red lines: GP limit for a network consisting of all paths (solid), the good path (dashed), and the good and denoising paths (dotted). Bottom: Matrix elements of U, for varying N. The matrix indices are labeled with the corresponding path name, according to the legend in (b). (d) Normalized overlap, or cosine similarity, between the PCs of the kernel K and the vector of task labels Y (N = 10: blue; GP limit: orange). PCs are ranked by their eigenvalues, from largest to smallest. Only the first 30 PCs are shown. (e) Same as (c), but for increased στ = 5 and a network consisting of only the good and denoising paths.

Full paper#