TL;DR#

Offline Reinforcement Learning (RL) aims to train RL agents using only pre-collected data, without further interactions with the environment. A popular approach involves fitting the data to a sequence model and then using that model to generate actions that lead to a high expected return. However, these methods often suffer from “inference-time suboptimality,” meaning that while the model accurately represents the data, it struggles to effectively utilize this knowledge to choose good actions during evaluation. This is partly due to the inherent stochasticity in the data and the environment.

This paper introduces Trifle, a novel offline RL algorithm that addresses this issue by using “Tractable Probabilistic Models” (TPMs). TPMs are a class of generative models that allow for efficient and exact computation of various probabilistic queries. By leveraging TPMs, Trifle bridges the gap between accurate sequence models and high expected returns during evaluation. The empirical results on various benchmark tasks show that Trifle outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods, especially in scenarios with stochastic environments or constraints on actions (safe RL). This demonstrates the significant impact of tractability on offline RL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical limitation in offline reinforcement learning (RL) – the suboptimal inference-time performance of existing methods. By highlighting the importance of tractability and introducing Trifle, which leverages tractable generative models, the paper significantly advances the field. This opens avenues for more robust and efficient offline RL algorithms, especially in stochastic and safe RL environments, thus impacting many real-world applications of RL.

Visual Insights#

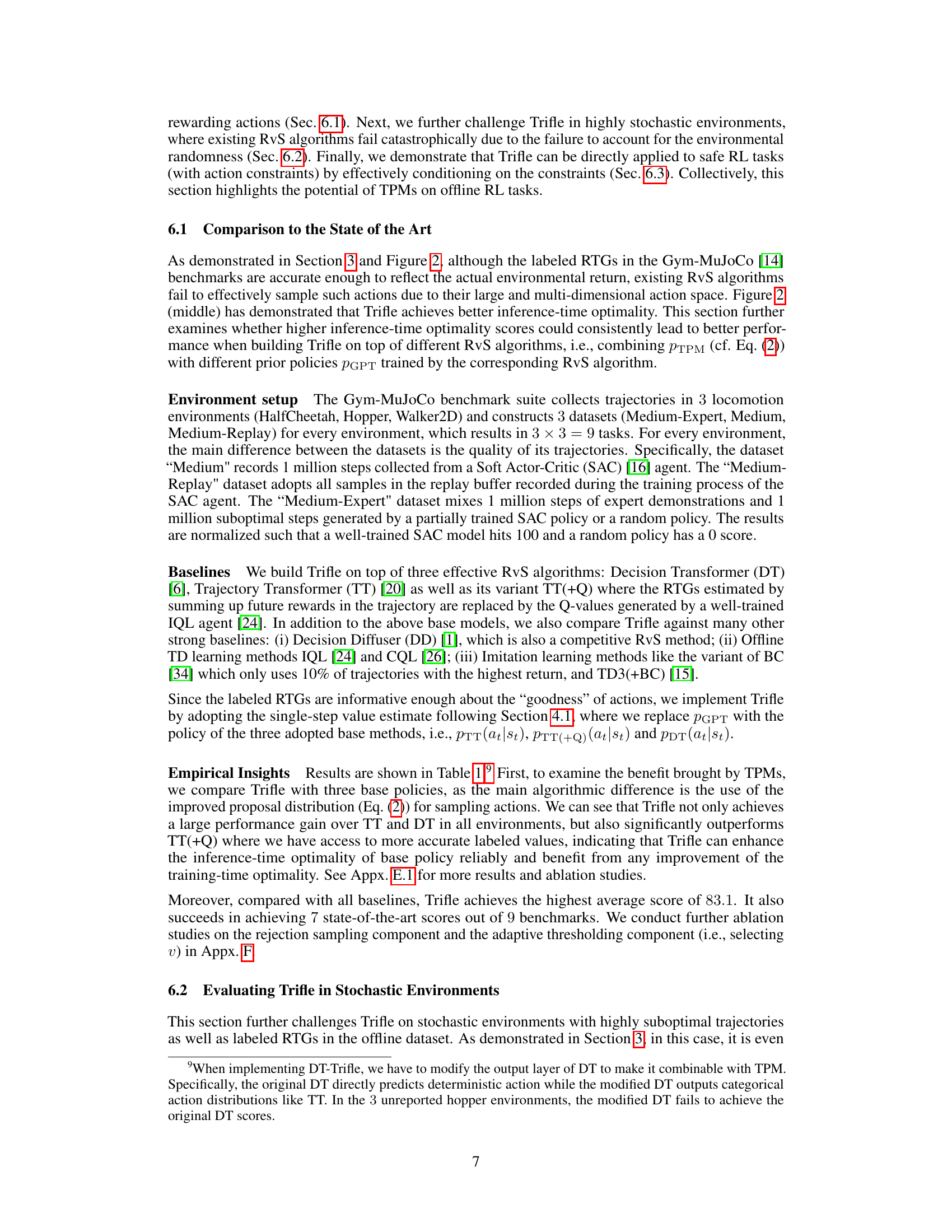

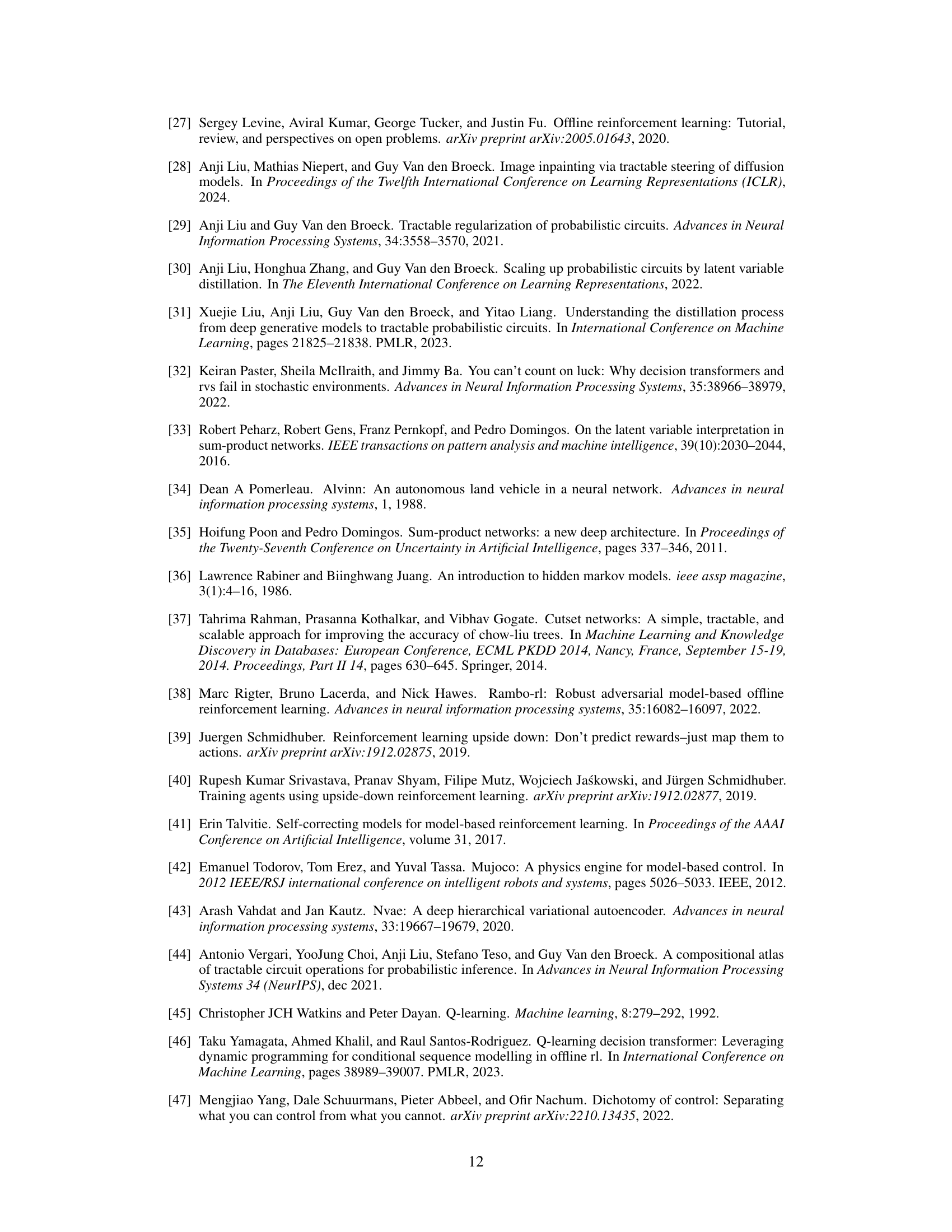

🔼 This figure shows an example of a Probabilistic Circuit (PC). PCs are a type of tractable probabilistic model used in the paper. The figure illustrates the structure of a PC, showing input nodes (representing simple distributions over variables X1 to X4), product nodes (modeling factorized distributions), and sum nodes (representing weighted mixtures). Each node’s probability is labeled, demonstrating how the PC computes a joint probability distribution.

read the caption

Figure 1: An example PC over boolean variables X1,..., X4. Every node's probability given input X1X2X3X4 is labeled in blue. p(x1X2X3X4) = 0.22.

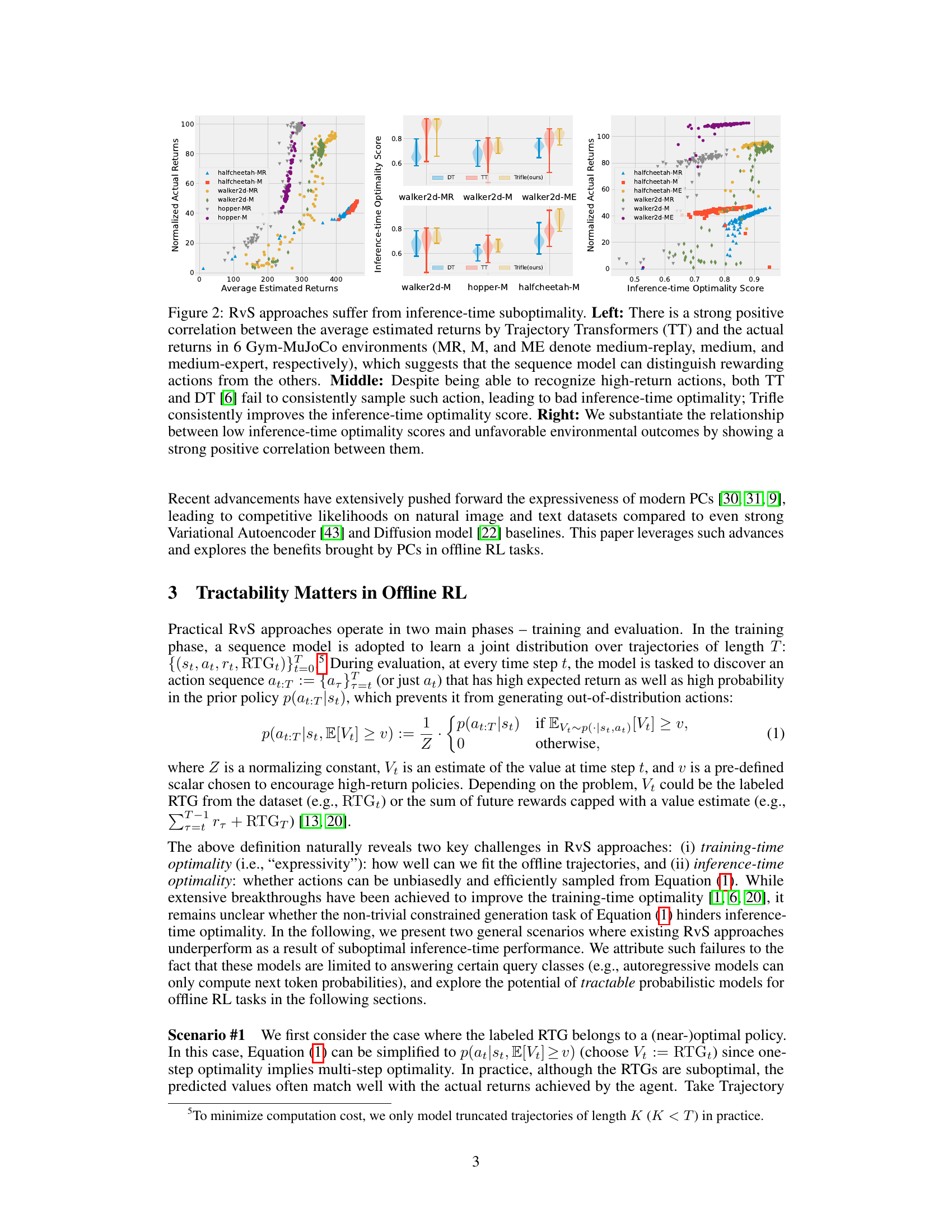

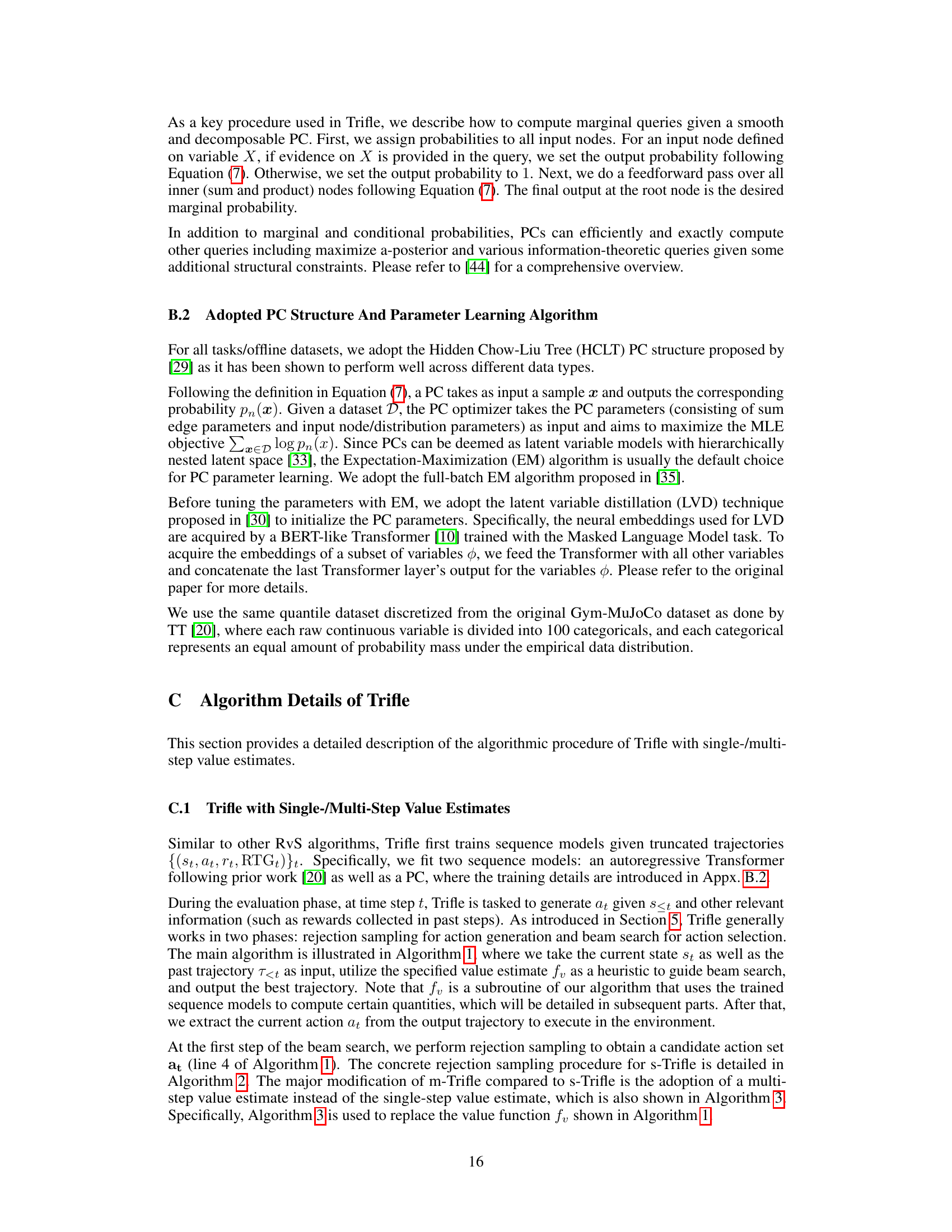

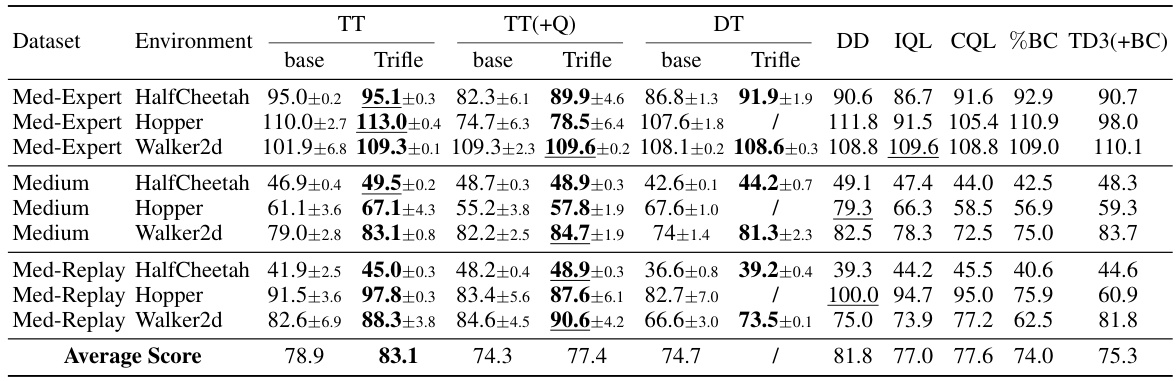

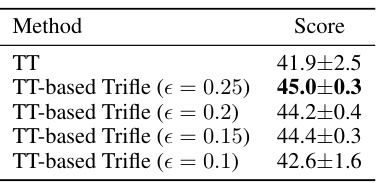

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the normalized scores achieved by different offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The ‘Trifle’ algorithm is the focus, and its performance is compared against several baseline methods. The results for Trifle are averages across 12 different random seeds to show statistical significance. The table includes various dataset types (Med-Expert, Medium, and Med-Replay) and environments (HalfCheetah, Hopper, and Walker2d). Normalized scores allow comparison across different environments.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

In-depth insights#

Tractable Offline RL#

Tractable Offline Reinforcement Learning (RL) tackles the challenge of learning effective policies from a fixed dataset of past experiences, without the ability to interact with the environment. A key limitation of existing offline RL methods is their inability to efficiently and accurately estimate expected returns, often leading to suboptimal policy performance. This is because many common approaches rely on expressive but intractable sequence models. Tractable Offline RL addresses this problem by leveraging tractable probabilistic models, which allow for exact and efficient computation of relevant probabilistic queries, including expected returns. This approach bridges the gap between expressive sequence modeling and high expected return at evaluation time, significantly boosting performance, particularly in stochastic environments. The use of tractable models enhances inference-time optimality, leading to more effective action selection and improved overall results.

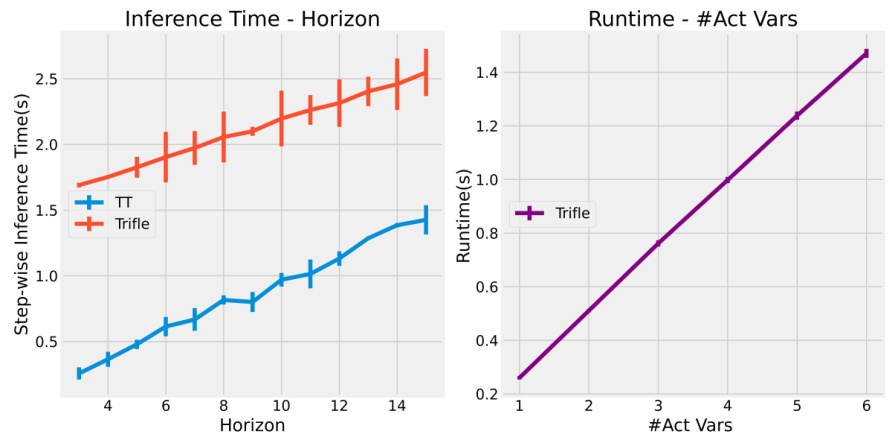

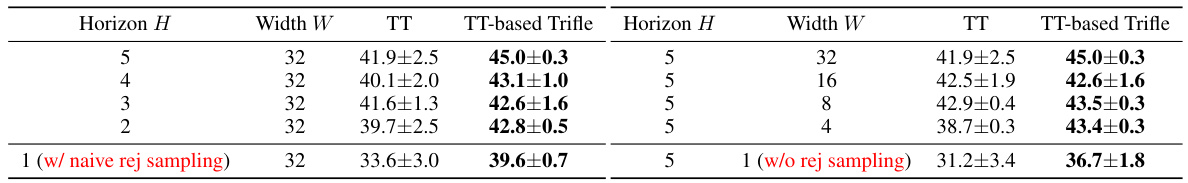

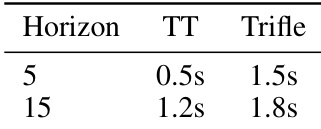

Trifle Algorithm#

The Trifle algorithm, designed for offline reinforcement learning, tackles the limitations of existing methods by emphasizing tractability. Unlike approaches that solely focus on expressive sequence modeling, Trifle leverages tractable probabilistic models (TPMs) like probabilistic circuits to efficiently compute marginal probabilities and answer various queries. This allows Trifle to accurately estimate expected returns and sample high-rewarding actions during evaluation, addressing the common underperformance of RvS algorithms. By combining this tractable inference with a beam search, Trifle significantly outperforms existing methods, particularly in stochastic environments. The algorithm’s ability to handle constraints makes it applicable to safe RL tasks. Trifle’s key innovation is its integration of TPMs; this facilitates exact calculations, mitigating the approximations inherent in many RvS approaches. The empirical results demonstrate Trifle’s state-of-the-art performance and generalizability across diverse benchmarks.

Inference Optimality#

The concept of “Inference Optimality” in offline reinforcement learning (RL) centers on how effectively a learned model translates its training-acquired knowledge into optimal action selection during evaluation. High inference optimality implies that the model accurately identifies and selects high-reward actions, even in unseen states, while low optimality indicates a disconnect between the model’s capabilities and its performance on new data. This discrepancy arises due to various factors such as the stochasticity of the environment, imperfect reward modeling, and limitations of the employed sequence models, which may not be adept at handling complex conditional probability queries needed for optimal decision-making in offline RL. Tractable probabilistic models (TPMs) are proposed to enhance inference optimality by enabling the exact and efficient computation of such queries. The use of TPMs bridges the gap between the expressive power of sequence models, which are trained to recognize high-reward action sequences, and the algorithm’s ability to effectively utilize this information for optimal decision-making at evaluation time. The key benefit is that TPMs facilitate accurate expected return estimation given uncertain dynamics and allow the agents to generate actions that yield significantly higher returns, overcoming limitations observed in previous methods.

Stochasticity Effects#

The presence of stochasticity, or randomness, significantly impacts offline reinforcement learning. Stochastic environments introduce variability in transitions and rewards, making it difficult for models to accurately learn optimal policies from offline data alone. Model inaccuracies stemming from stochasticity can lead to suboptimal action selection during evaluation. Tractable probabilistic models (TPMs) are presented as a solution because of their ability to handle uncertainty inherent in stochastic systems, offering a potential advantage over traditional approaches that struggle with these complexities. Approximation errors, inherent in many offline RL methods, are exacerbated by stochasticity. The paper emphasizes the need to move beyond simply expressive sequence modeling and embrace models that can efficiently and accurately address probabilistic queries, leading to improved robustness and performance in the face of environmental uncertainty.

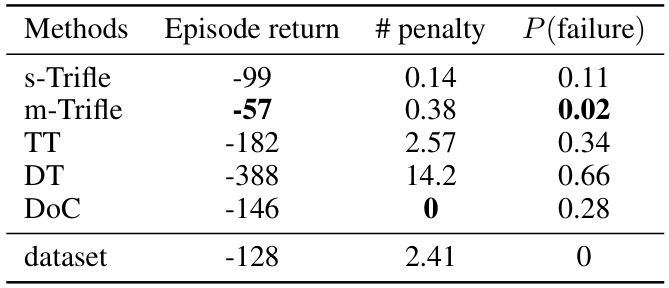

Safe RL Tasks#

In the context of reinforcement learning (RL), ensuring safety is paramount, especially when deploying agents in real-world scenarios. Safe RL tasks address this by incorporating constraints or penalties that prevent the agent from taking actions that could lead to undesirable outcomes, such as physical damage or system failures. These constraints could be explicitly defined (e.g., limiting the maximum torque applied to a robotic joint) or implicitly incentivized (e.g., rewarding the agent for remaining within a safe operational space). The challenge lies in balancing safety with performance: overly restrictive constraints could hinder the agent’s ability to learn optimal policies, while overly permissive constraints could lead to unsafe behavior. Successful safe RL approaches often involve careful design of reward functions and constraint satisfaction methods. They might utilize techniques such as constrained optimization, penalty methods, or barrier functions to guide the agent towards safe and effective behavior. The evaluation of safe RL algorithms requires careful consideration of safety metrics beyond standard RL performance measures. These could include metrics that quantify the frequency and severity of safety violations, the robustness of the policy to unexpected disturbances, and the overall reliability of the system. Future research in this field should focus on developing more robust and efficient methods for incorporating safety constraints, expanding the range of environments in which safe RL can be effectively applied, and improving the interpretability and trustworthiness of safe RL agents.

More visual insights#

More on figures

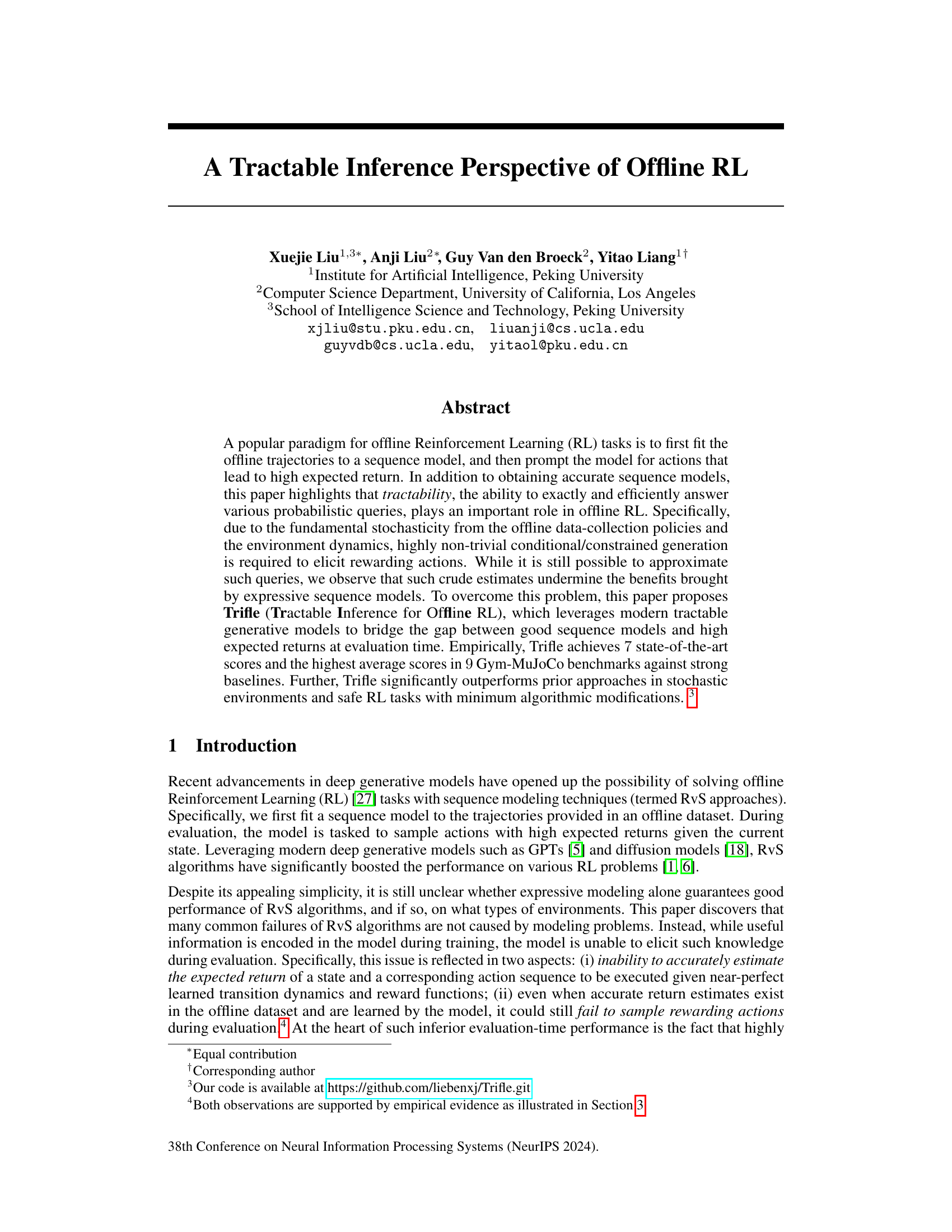

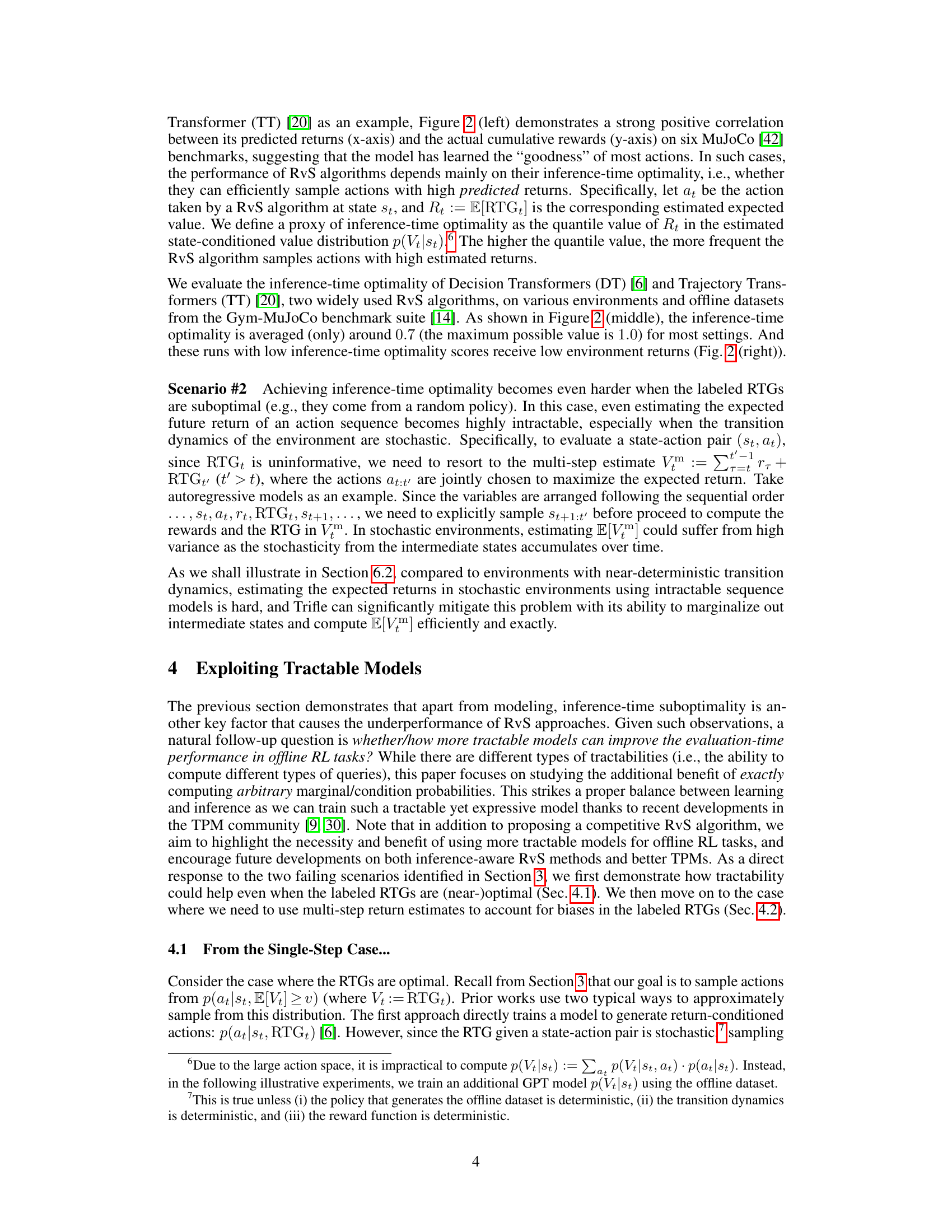

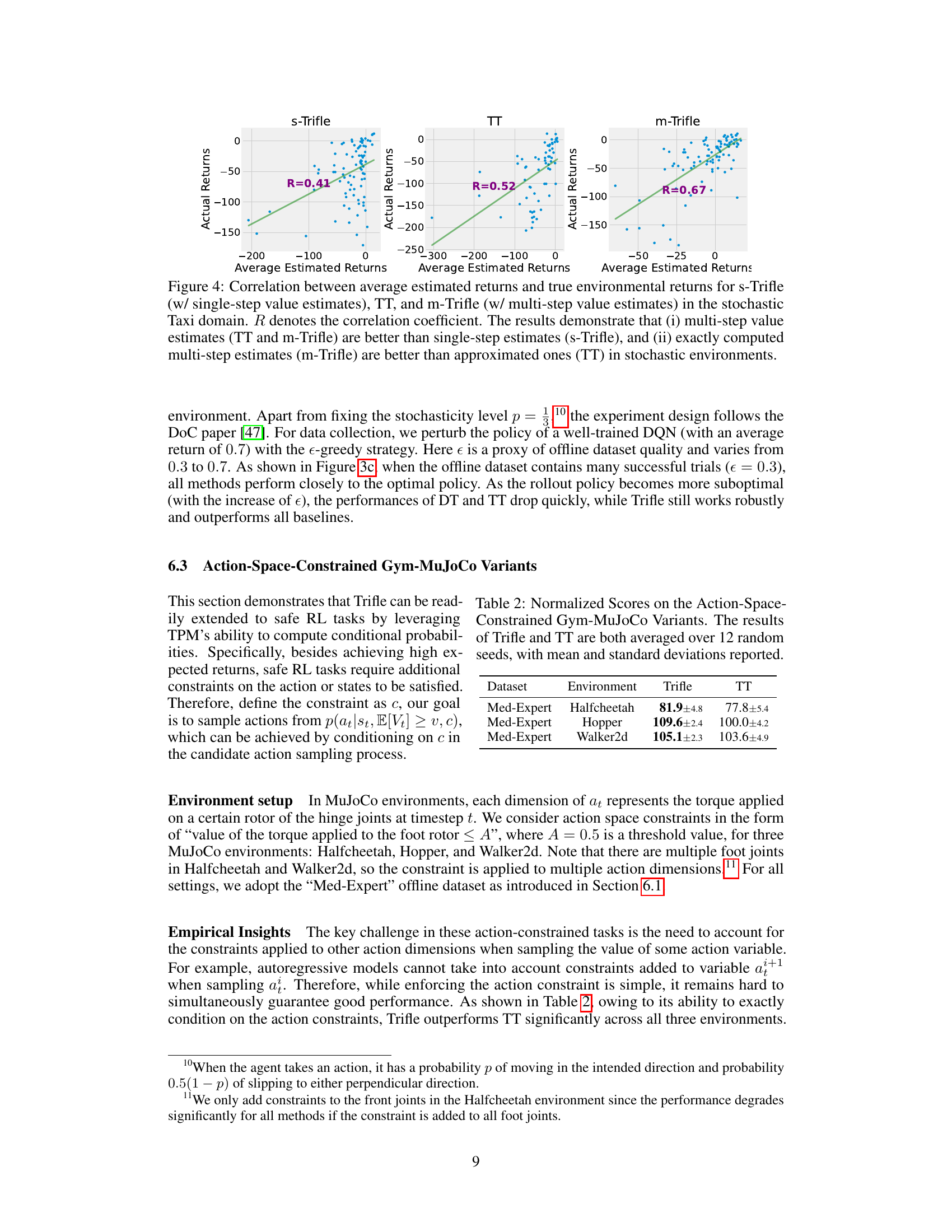

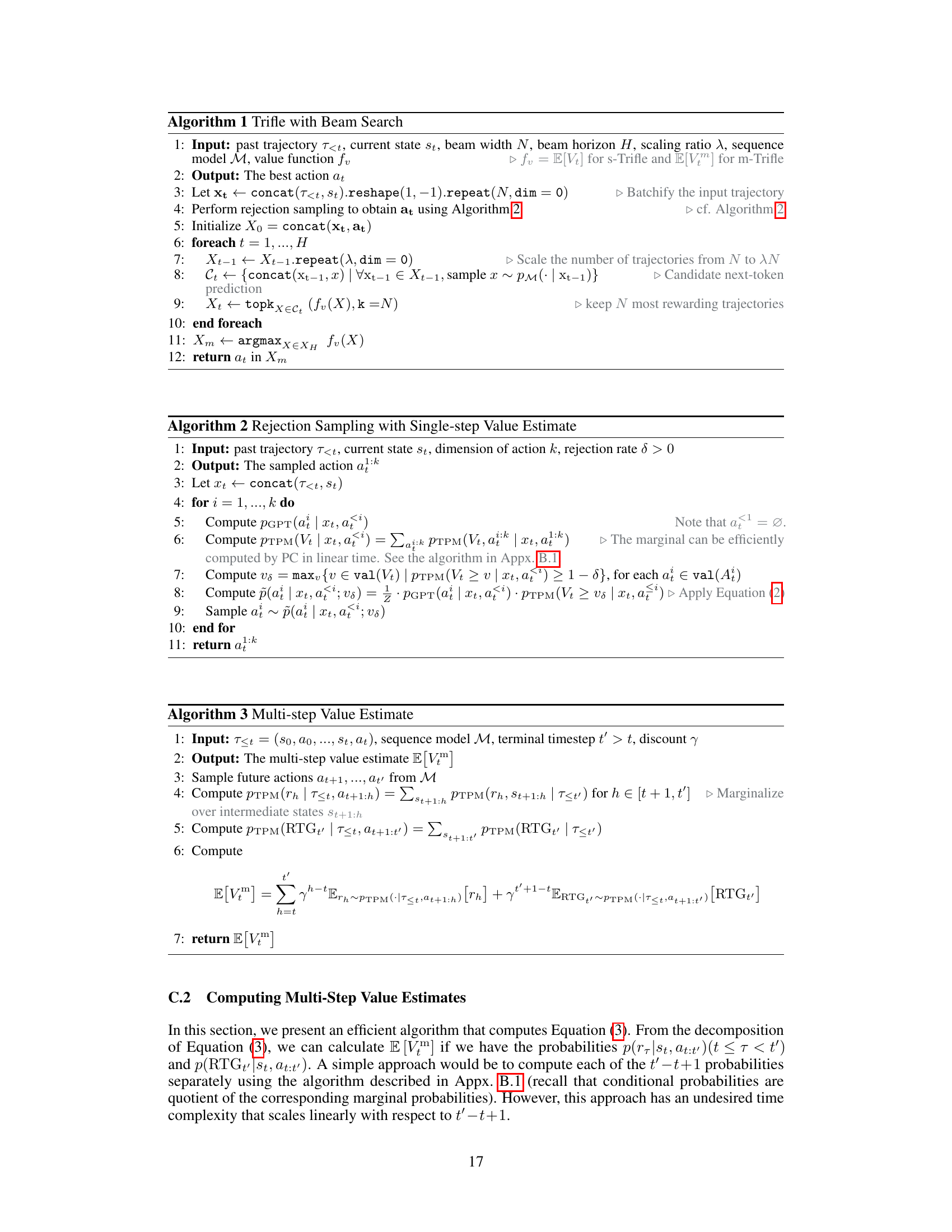

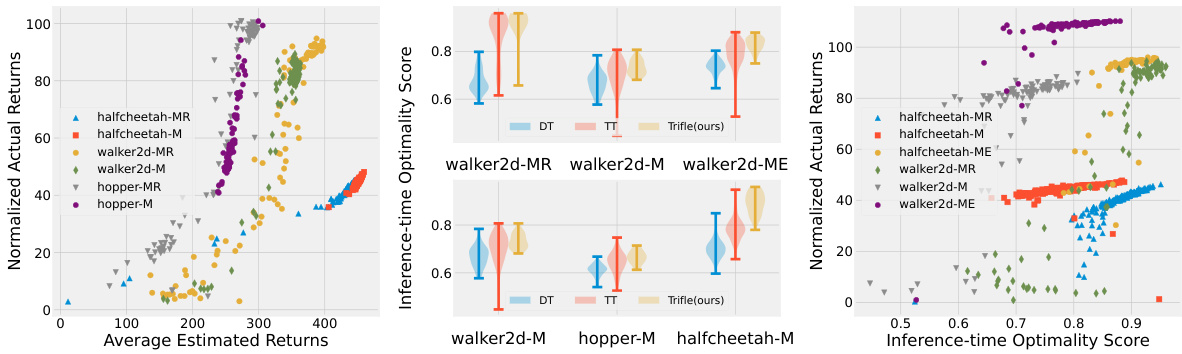

🔼 This figure demonstrates the inference-time suboptimality problem in RvS algorithms. The left panel shows a strong positive correlation between estimated and actual returns, indicating the model’s ability to identify rewarding actions. However, the middle panel reveals that both TT and DT struggle to consistently sample these actions, resulting in low inference-time optimality scores. Trifle significantly improves this score. The right panel confirms the negative impact of low inference-time optimality on actual returns.

read the caption

Figure 2: RvS approaches suffer from inference-time suboptimality. Left: There is a strong positive correlation between the average estimated returns by Trajectory Transformers (TT) and the actual returns in 6 Gym-MuJoCo environments (MR, M, and ME denote medium-replay, medium, and medium-expert, respectively), which suggests that the sequence model can distinguish rewarding actions from the others. Middle: Despite being able to recognize high-return actions, both TT and DT [6] fail to consistently sample such action, leading to bad inference-time optimality; Trifle consistently improves the inference-time optimality score. Right: We substantiate the relationship between low inference-time optimality scores and unfavorable environmental outcomes by showing a strong positive correlation between them.

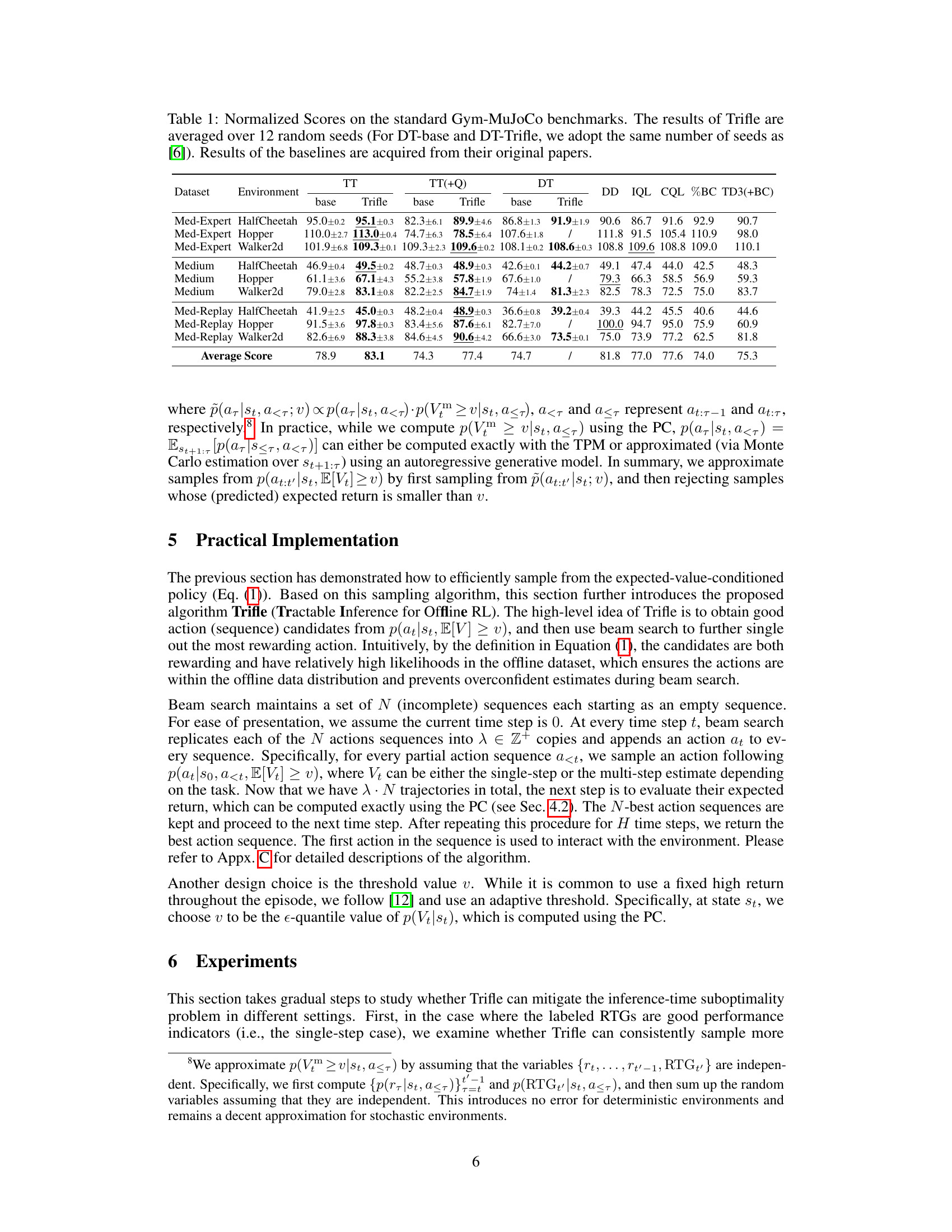

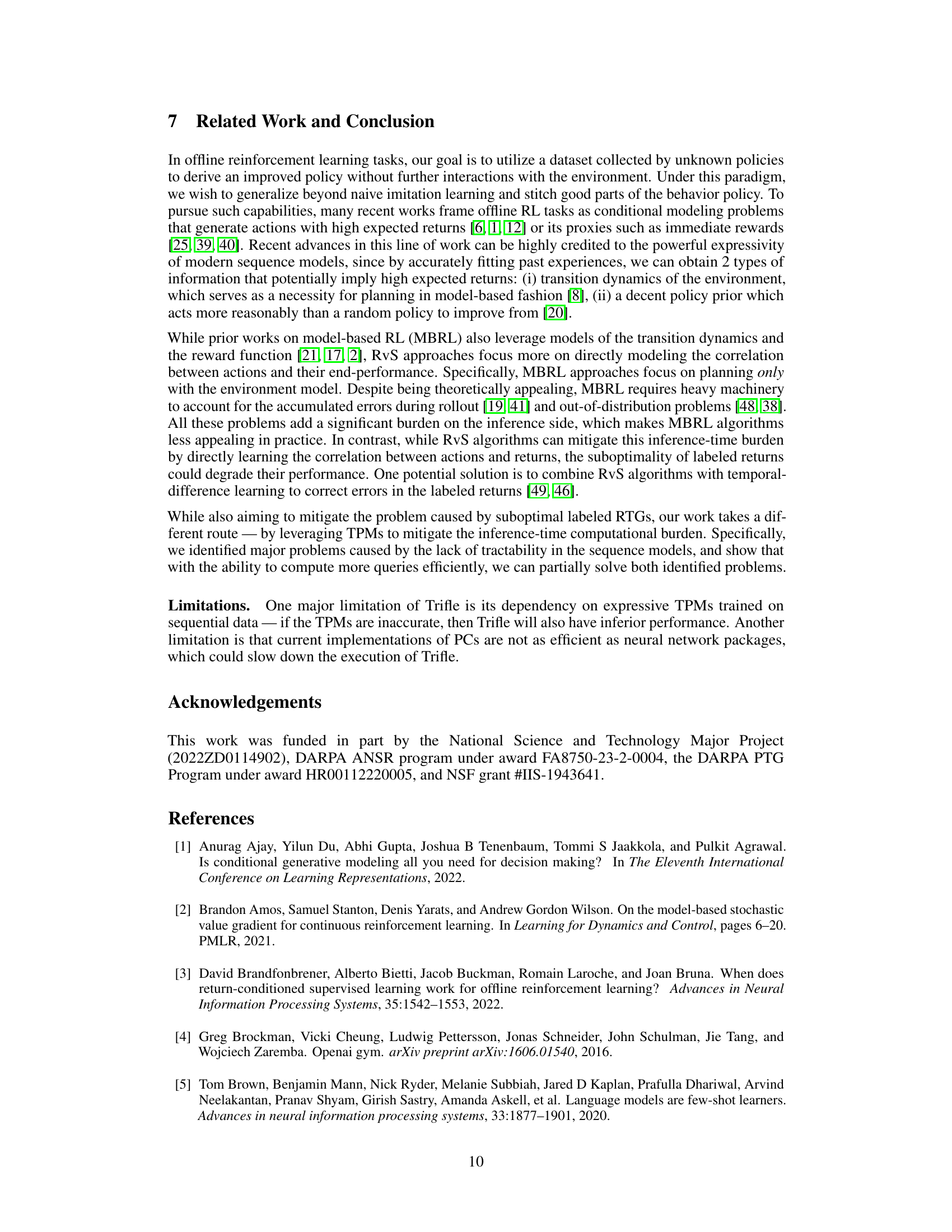

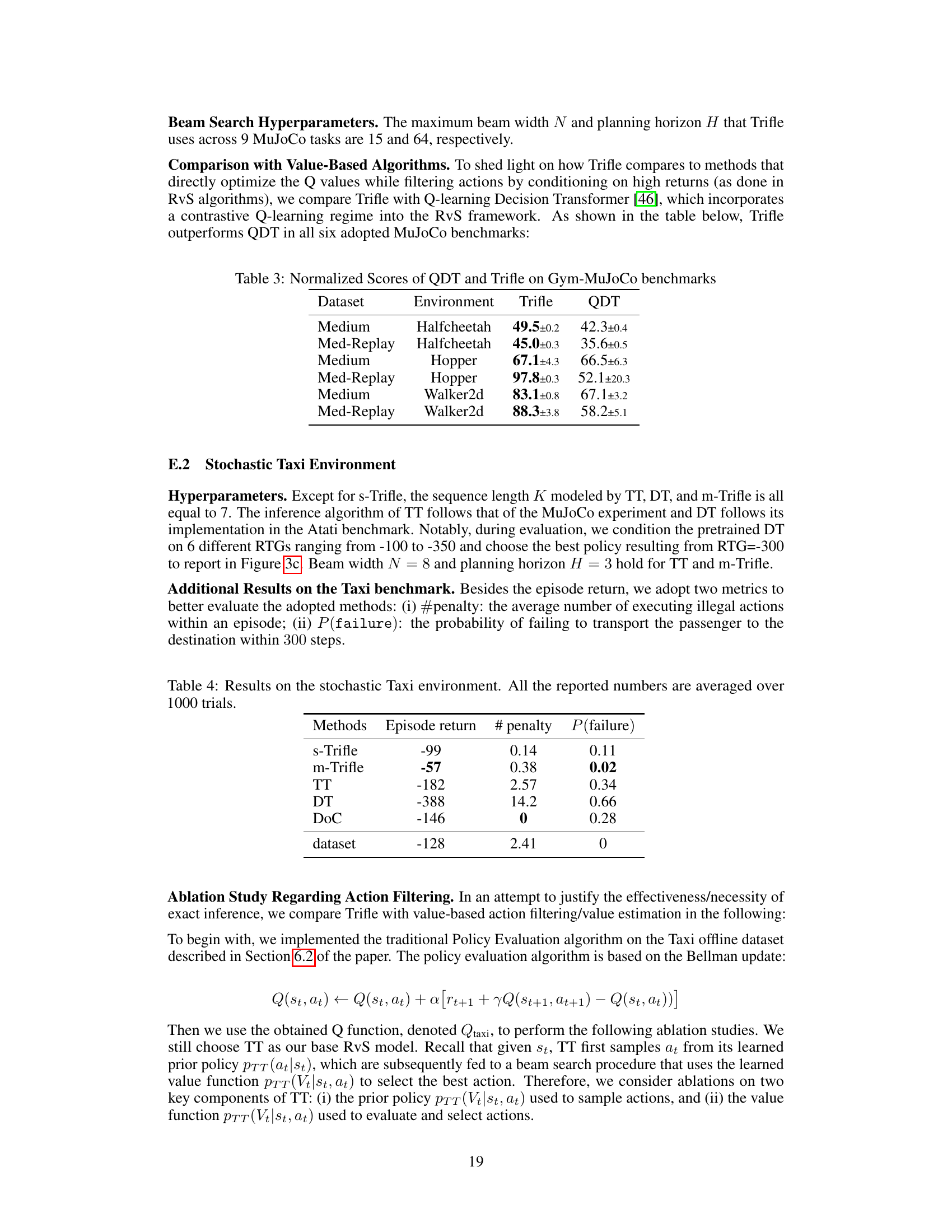

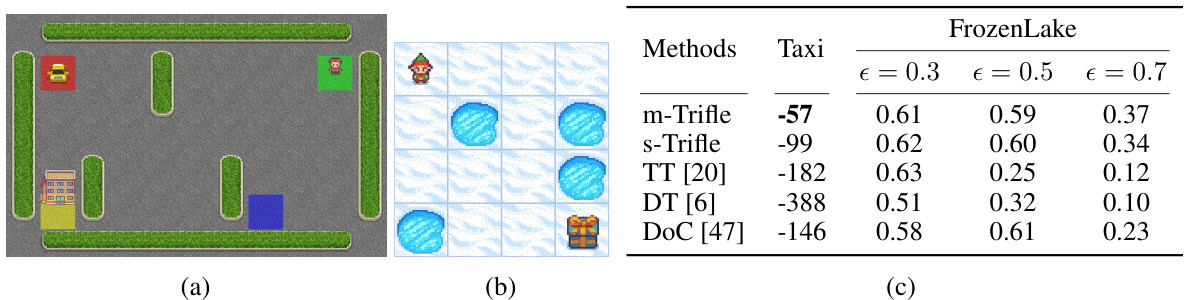

🔼 This figure shows the stochastic Taxi and FrozenLake environments and a table summarizing the average returns achieved by different RL algorithms in these environments. The Taxi environment involves a taxi navigating a grid to pick up a passenger and drop them off at a destination, with stochasticity in movement. The FrozenLake environment is a grid world where the agent must navigate to a goal while avoiding holes, also with stochastic movement. The table displays average returns for various algorithms (m-Trifle, s-Trifle, TT, DT, DoC), with varying levels of stochasticity (epsilon values of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7). The results highlight Trifle’s robustness in stochastic environments.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a) Stochastic Taxi environment; (b) Stochastic FrozenLake Environment; (c) Average returns on the stochastic environment. All the reported numbers are averaged over 1000 trials.

🔼 This figure shows the strong positive correlation between estimated and actual returns in 6 Gym-MuJoCo environments, indicating that the model identifies rewarding actions. However, both TT and DT struggle to consistently sample these actions, highlighting the suboptimality of the inference time. Trifle effectively addresses this issue by improving the inference-time optimality scores and achieving better results.

read the caption

Figure 2: RvS approaches suffer from inference-time suboptimality. Left: There is a strong positive correlation between the average estimated returns by Trajectory Transformers (TT) and the actual returns in 6 Gym-MuJoCo environments (MR, M, and ME denote medium-replay, medium, and medium-expert, respectively), which suggests that the sequence model can distinguish rewarding actions from the others. Middle: Despite being able to recognize high-return actions, both TT and DT [6] fail to consistently sample such action, leading to bad inference-time optimality; Trifle consistently improves the inference-time optimality score. Right: We substantiate the relationship between low inference-time optimality scores and unfavorable environmental outcomes by showing a strong positive correlation between them.

🔼 This figure shows that while sequence models in reinforcement learning can identify high-return actions, they often fail to consistently sample them. This is due to suboptimal inference-time performance, and the paper’s proposed Trifle method addresses this issue.

read the caption

Figure 2: RvS approaches suffer from inference-time suboptimality. Left: There is a strong positive correlation between the average estimated returns by Trajectory Transformers (TT) and the actual returns in 6 Gym-MuJoCo environments (MR, M, and ME denote medium-replay, medium, and medium-expert, respectively), which suggests that the sequence model can distinguish rewarding actions from the others. Middle: Despite being able to recognize high-return actions, both TT and DT [6] fail to consistently sample such action, leading to bad inference-time optimality; Trifle consistently improves the inference-time optimality score. Right: We substantiate the relationship between low inference-time optimality scores and unfavorable environmental outcomes by showing a strong positive correlation between them.

More on tables

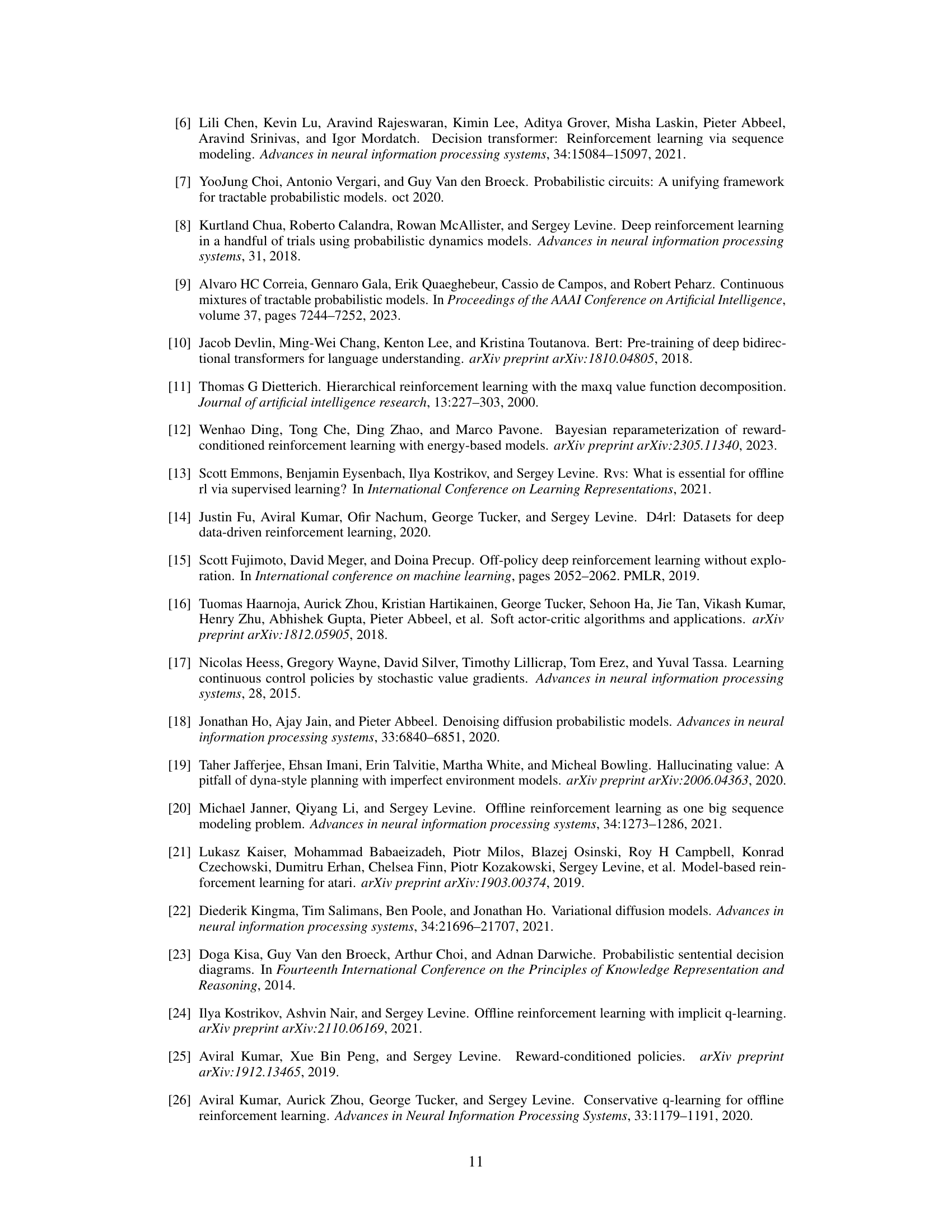

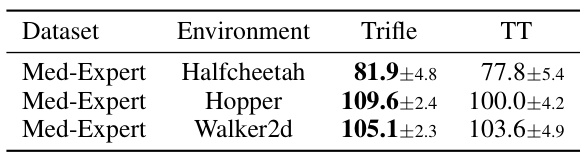

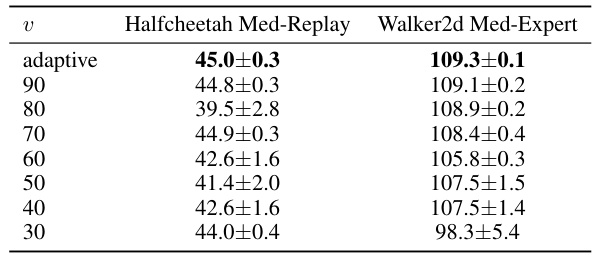

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison between Trifle and TT on action-space-constrained versions of three Gym-MuJoCo environments (Halfcheetah, Hopper, and Walker2d). The results are averages over 12 random seeds, reporting the mean and standard deviation of the normalized scores. The ‘Med-Expert’ dataset is used for all environments.

read the caption

Table 2: Normalized Scores on the Action-Space-Constrained Gym-MuJoCo Variants. The results of Trifle and TT are both averaged over 12 random seeds, with mean and standard deviations reported.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and various baseline algorithms across nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The datasets used vary in trajectory quality (Medium-Expert, Medium, and Med-Replay), while the environments encompass three different locomotion tasks (HalfCheetah, Hopper, and Walker2d). Trifle’s results are averaged across 12 independent runs to demonstrate statistical robustness. Baseline results are taken directly from their respective publications.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and other baseline algorithms on nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The results show Trifle’s performance in comparison to existing offline RL methods, broken down by dataset type (Medium-Expert, Medium, and Medium-Replay) and environment (HalfCheetah, Hopper, and Walker2d). The scores are normalized, with 100 representing a well-trained SAC agent and 0 representing a random policy. Trifle’s performance is averaged across 12 random seeds.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and various baseline methods across nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The scores are normalized to range from 0 (random policy) to 100 (a well-trained SAC agent). Trifle’s results are averaged over 12 random seeds for a robust evaluation, while baseline results are taken from their original papers.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and other baseline algorithms across various Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The scores are normalized relative to a well-trained SAC agent (100) and a random policy (0). Trifle’s results are averaged over 12 random seeds for robustness, using the same number of seeds as a comparable algorithm from a previous study where applicable. The results for other baselines are taken directly from their original papers.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and other offline RL baselines on nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark environments. These environments are categorized by dataset difficulty (Medium-Expert, Medium, and Medium-Replay), representing varying qualities of offline data. The table highlights Trifle’s state-of-the-art performance, achieving top scores on 7 out of 9 tasks and the highest average score overall.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and various baseline methods across nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark environments. The environments are categorized by dataset difficulty (Med-Expert, Medium, Med-Replay) and locomotion task (HalfCheetah, Hopper, Walker2d). Trifle’s results are averaged over 12 random seeds for a robust evaluation. The scores for baseline methods are taken directly from the cited papers, allowing for a fair comparison against state-of-the-art performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

🔼 This table presents the normalized scores achieved by Trifle and various baseline algorithms across nine standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The normalized scores are relative to a well-trained SAC agent (100) and a random policy (0). Trifle’s results are averaged over 12 random seeds for a fair comparison. Baseline results are taken from their respective original papers.

read the caption

Table 1: Normalized Scores on the standard Gym-MuJoCo benchmarks. The results of Trifle are averaged over 12 random seeds (For DT-base and DT-Trifle, we adopt the same number of seeds as [6]). Results of the baselines are acquired from their original papers.

Full paper#