↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) struggle with diverse vision-centric tasks due to their language-oriented design. They often adapt visual task outputs to language formats, overlooking the inductive biases in various visual tasks and hindering the learning of perception capabilities. This limits their potential in handling complex scenarios and versatile vision tasks.

The proposed Lumen architecture tackles this issue by decoupling perception learning into two stages: task-agnostic and task-specific. It first focuses on aligning vision and language concepts, creating a shared representation for various vision tasks. Then, it uses lightweight task-specific decoders, minimizing training efforts. Experimental results across various benchmarks demonstrate that Lumen achieves or surpasses the performance of existing LMM-based approaches while maintaining general visual understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large multimodal models (LMMs). It addresses the limitations of current LMMs in handling diverse vision-centric tasks by proposing a novel architecture called Lumen. Lumen’s unique approach of decoupling task-agnostic and task-specific learning processes opens up new avenues for improving the efficiency and versatility of LMMs, making it highly relevant to current research trends in computer vision and artificial intelligence. The findings are significant and will likely inspire future research into more robust and flexible LMM designs.

Visual Insights#

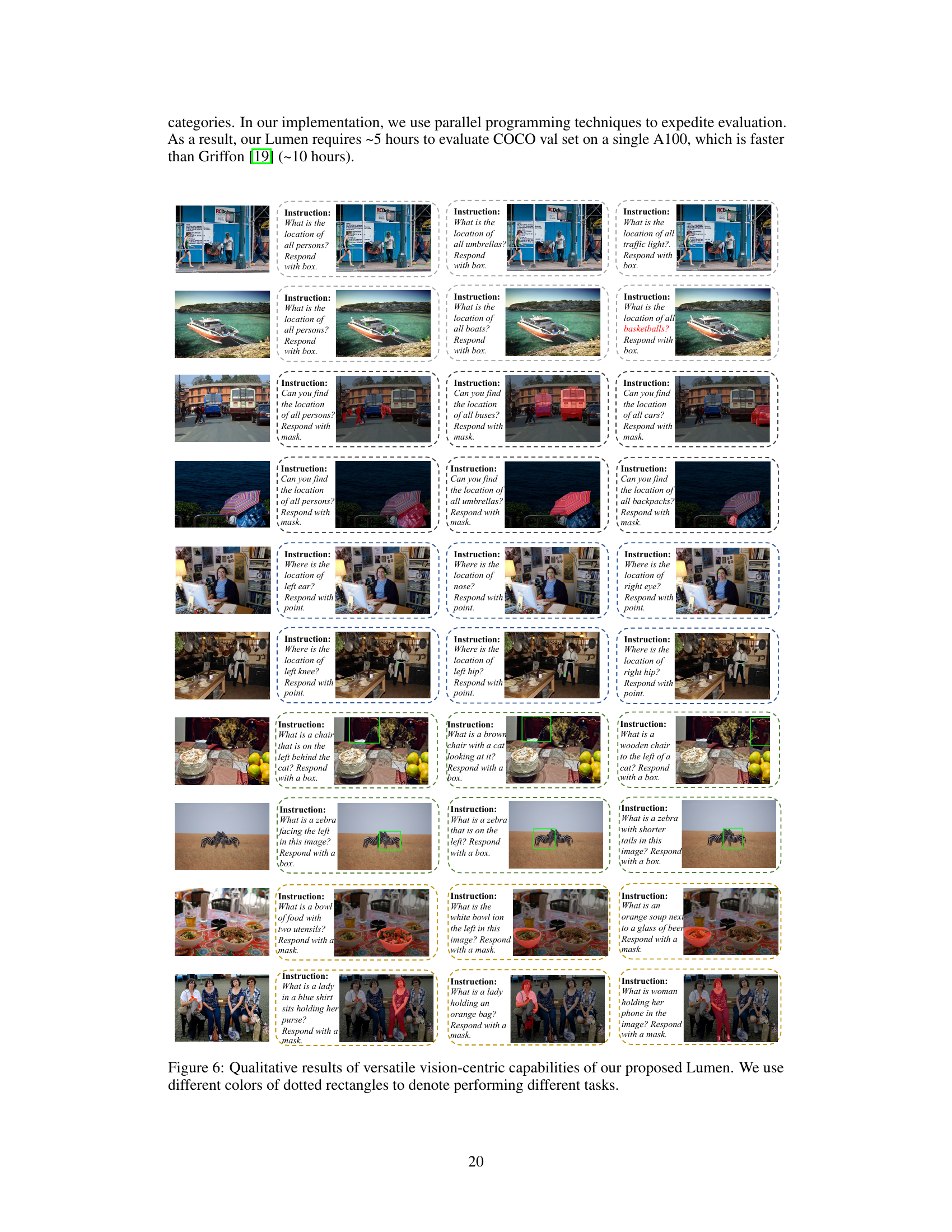

This figure compares the proposed Lumen model with previous approaches for handling vision-centric tasks within large multimodal models. Previous methods convert bounding box coordinates into sequential token sequences, which is convenient but ignores the inherent orderlessness of the boxes. Lumen, instead, initially predicts unified heatmaps for various tasks. These heatmaps are then used, with parsed task indicators, to guide simple decoding tools and thus handle diverse vision tasks effectively.

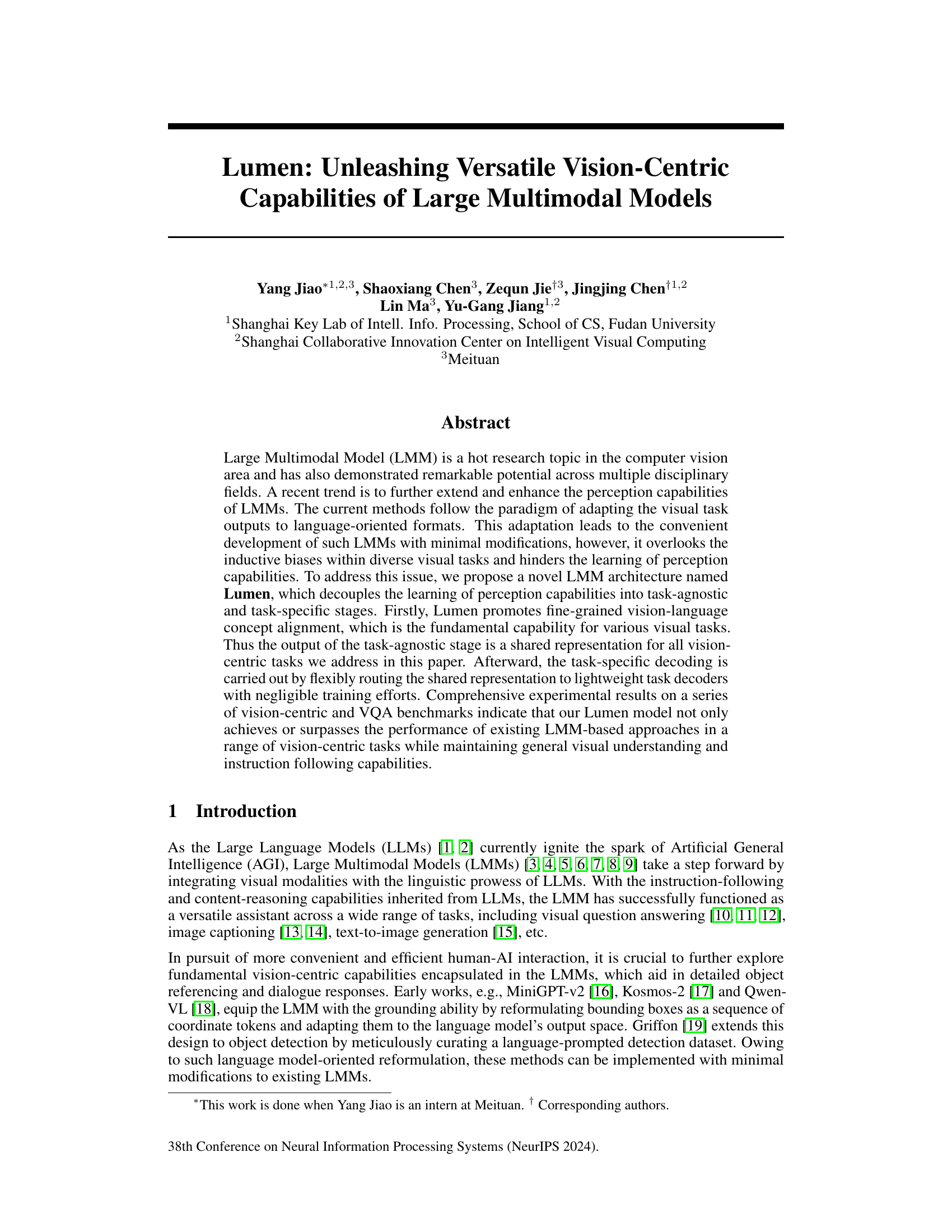

This table compares the performance of different methods on various vision-centric tasks (object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation) and vision-language tasks (visual grounding, referring segmentation). The methods are categorized into three groups: Task-specific Specialists (models specialized for a single task), Vision Generalists (models capable of handling multiple vision tasks), and LMM Generalists (large multimodal models). The table shows that the proposed Lumen method performs competitively with or surpasses existing methods, demonstrating versatility across different tasks.

In-depth insights#

Vision-centric LMM#

Vision-centric Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) represent a significant advancement in AI, pushing beyond the limitations of previous approaches. The core idea is to leverage the strengths of LLMs for higher-level reasoning and combine them with robust visual perception capabilities. This differs from earlier methods that primarily focused on adapting visual outputs to a language-friendly format, often neglecting the inherent inductive biases of various visual tasks. A vision-centric LMM prioritizes the accurate and detailed understanding of visual information before integrating it with language. This approach allows for more nuanced and effective handling of complex visual scenarios, leading to superior performance in tasks such as object detection, instance segmentation, and pose estimation. The decoupling of task-agnostic and task-specific learning stages is a key innovation; this modularity allows for greater flexibility and scalability in handling diverse visual tasks with minimal retraining. The use of heatmaps for intermediate representations provides a powerful mechanism for unifying different visual outputs, simplifying the decoding process and improving efficiency. While this paradigm shows great promise, it’s crucial to address potential challenges like maintaining general visual understanding and instruction-following abilities while enhancing vision-centric capabilities.

Unified Heatmaps#

The concept of “Unified Heatmaps” in a multimodal model context suggests a powerful strategy for handling diverse vision tasks. Instead of processing each task (e.g., object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation) independently, a unified heatmap representation could capture shared underlying visual information. This approach could significantly improve efficiency by avoiding redundant computations across separate models. The unified heatmap would serve as a rich, shared representation that is then flexibly routed to task-specific decoders. This decoupling of task-agnostic and task-specific processing offers advantages in training efficiency and generalization, avoiding the need for task-specific architectures and minimizing inductive biases. The key challenge lies in designing the appropriate heatmap encoding, ensuring it captures sufficient information to accurately guide each specialized decoder. The success of this method hinges on the ability to achieve fine-grained alignment between visual features and the task instruction. Moreover, evaluating the effectiveness and potential limitations of a unified heatmap approach necessitates a thorough comparison with traditional task-specific models across various datasets and benchmarks. This includes assessing trade-offs between performance and computational cost and analyzing how effectively the shared representation generalizes to unseen data and tasks.

Task-Specific Decoders#

Task-specific decoders represent a crucial component in adapting large multimodal models (LMMs) to diverse vision-centric tasks. Instead of forcing all tasks into a language-centric format, task-specific decoders allow the model to output results in their native formats, such as bounding boxes for object detection, segmentation masks for instance segmentation, or keypoint coordinates for pose estimation. This approach not only improves efficiency by avoiding unnecessary transformations but also preserves the inherent characteristics of each task, leading to better performance. The design of these decoders is critical; they should be lightweight to avoid increased computational cost and easily adaptable to new tasks, preferably with minimal retraining. The success of a task-specific decoder framework hinges on effective decoupling of task-agnostic and task-specific learning stages. While a shared representation captures common visual understanding, specialized decoders handle the nuances of individual tasks. This modular design is key to scaling LMMs to a wider range of applications and enhancing overall versatility.

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically assess the contribution of individual components within a model. By removing or altering specific parts, researchers can isolate the impact of each element and understand its relative importance. In the context of a large multimodal model (LMM) like Lumen, such experiments might involve removing specific modules or layers within the architecture, changing hyperparameters, or utilizing alternative pre-trained models. Analyzing the performance changes after each ablation provides critical insights into the model’s design choices, identifying crucial elements and potential weaknesses. For example, ablating the task-agnostic stage of Lumen could reveal its importance in generating a shared representation before task-specific decoding. Significant performance drops following this would highlight the effectiveness of this design. Conversely, a small performance decrease suggests that the module might be redundant or less critical than others. These experiments are crucial for establishing the efficiency and robustness of the architecture. Furthermore, ablation studies can reveal areas for future model improvements, guiding subsequent development of the LMM. The results of ablation studies validate the design choices and provide insights for improving future model development.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the Lumen architecture is crucial, particularly given the computational demands of large multimodal models. This could involve investigating more efficient attention mechanisms or exploring alternative model architectures that maintain performance with fewer parameters. Expanding the range of vision-centric tasks addressed by Lumen is another key direction, potentially through incorporating more diverse datasets and refining task-specific decoders. A particularly interesting area is exploring how Lumen can be used for complex, multi-step vision tasks, which could lead to improved capabilities in fields such as robotics and autonomous driving. Furthermore, investigating the robustness of Lumen to noisy or incomplete visual inputs would enhance its practical applicability. Finally, it’s important to study the ethical implications of this technology, especially its potential for bias and misuse, to ensure its responsible development and deployment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the two-stage architecture of the Lumen model. Stage 1 focuses on task-agnostic matching using a large language model to align image and instruction features, resulting in a heatmap. Stage 2 performs task-specific decoding based on this heatmap, using lightweight decoders for various vision tasks (object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation, visual grounding, referring segmentation). The task-specific decoder is selected based on the task token generated in stage 1.

This figure illustrates the two-stage framework of the Lumen model. Stage 1 focuses on task-agnostic matching, where the image and instruction are processed by a large language model to generate a heatmap representing the alignment between visual concepts and the instruction. Stage 2 uses this heatmap for task-specific decoding, routing the information to lightweight decoders based on the task type. This decoupled approach allows for versatile vision-centric capabilities.

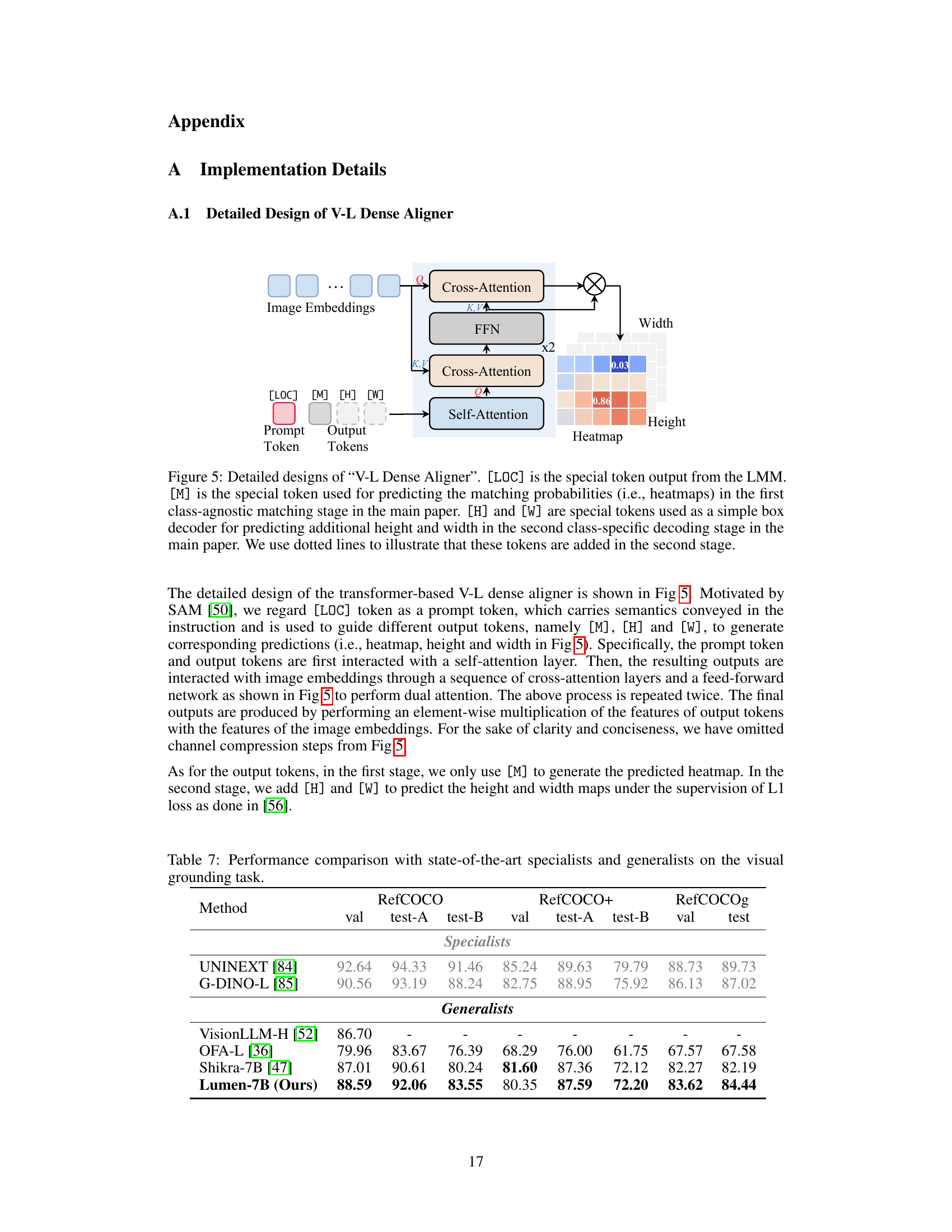

The figure shows the detailed architecture of the V-L Dense Aligner, a key component of the Lumen model. It uses a transformer-based architecture with multiple cross-attention and self-attention layers. The input includes image embeddings and special tokens ([LOC], [M], [H], [W]) from the large language model (LLM). The [LOC] token represents the location information from the LLM’s output, [M] predicts the heatmap, and [H] and [W] are used for box decoder to predict height and width. The output is a heatmap showing the alignment between the image and instruction, crucial for downstream vision tasks. The design uses a two-stage process: The first stage performs task-agnostic matching, and the second stage performs task-specific decoding, using lightweight decoders guided by the heatmap.

This figure illustrates the two-stage architecture of the Lumen model. The first stage involves a task-agnostic matching process where the input image and instruction are processed by a large language model to create a shared representation (heatmap) indicating the relationship between visual concepts and the instruction. The second stage uses this heatmap as guidance for task-specific decoding, where lightweight decoders generate outputs tailored to specific tasks (object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation). The type of output is determined by special tokens in the instruction.

More on tables

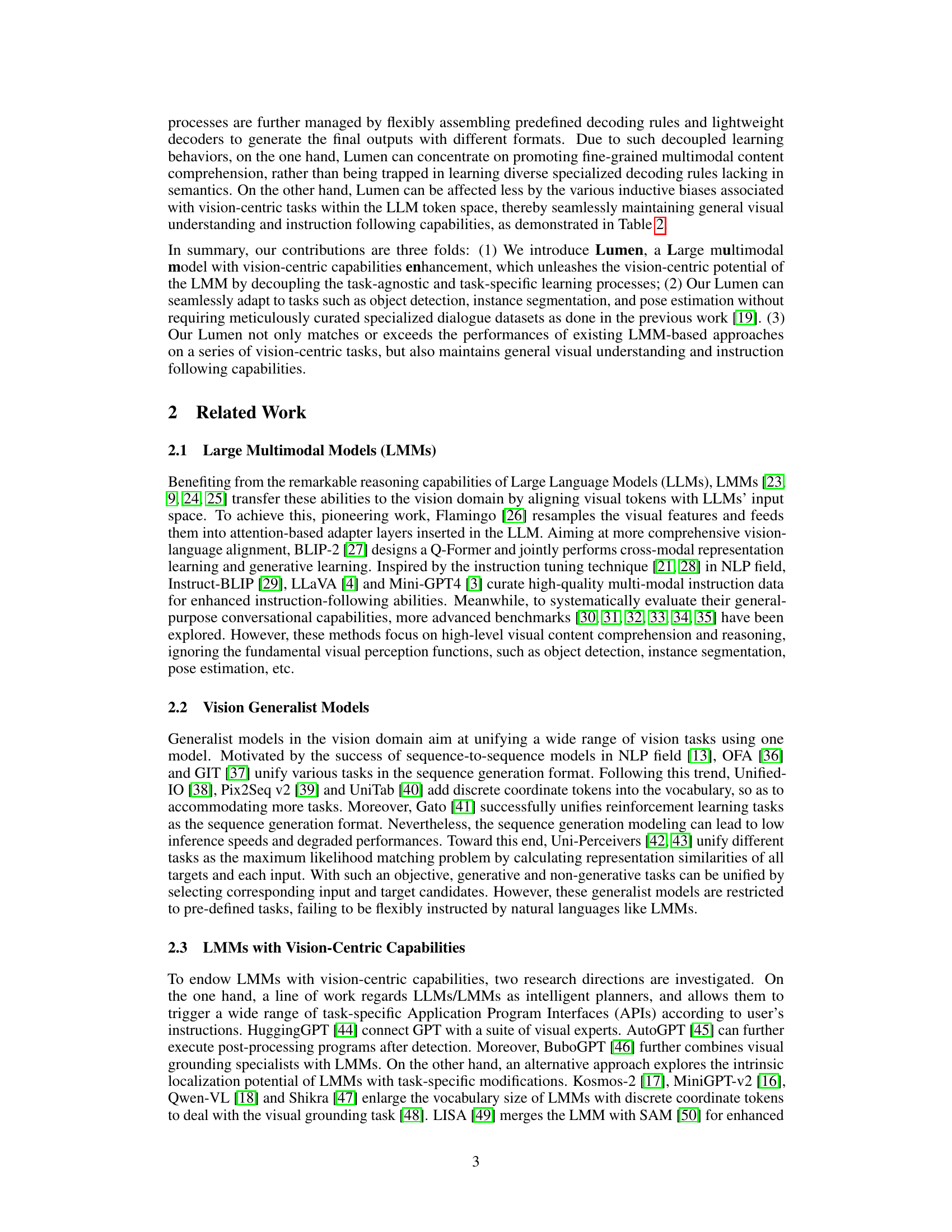

This table shows the results of the Lumen model on several popular Visual Question Answering (VQA) benchmarks. It compares the performance of Lumen against other state-of-the-art Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) on various datasets, including MMBench (a comprehensive benchmark for multimodal LMMs), SEEDBench (focused on image understanding), MME (a multi-modal reasoning benchmark), MMMU (a massive multi-discipline multimodal benchmark), and MathVista (a benchmark for mathematical reasoning). The table highlights the model’s performance across different datasets and demonstrates its capabilities in understanding and reasoning with both visual and textual information.

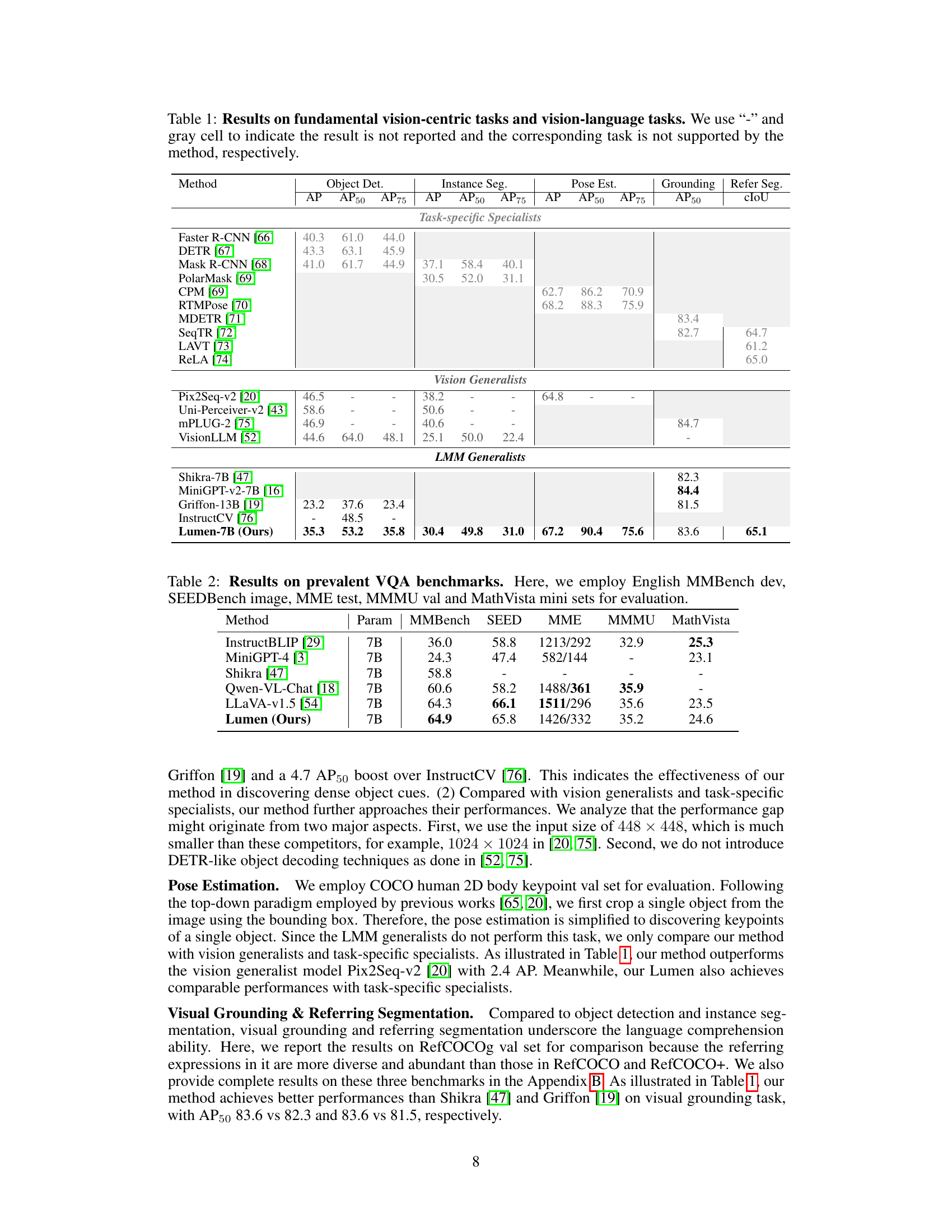

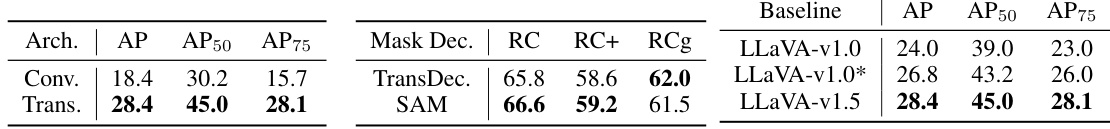

This table presents ablation study results to analyze the impact of different design choices on the Lumen model’s performance. It investigates three aspects: the architecture of the V-L dense aligner (comparing convolutional and transformer-based designs), the choice of pretrained mask decoder (comparing a custom-trained decoder with the SAM model), and the impact of different Large Multimodal Model (LMM) baselines (comparing LLaVA v1.0, LLaVA v1.0* and LLaVA v1.5). The results help understand which design choices contribute most to the model’s overall effectiveness.

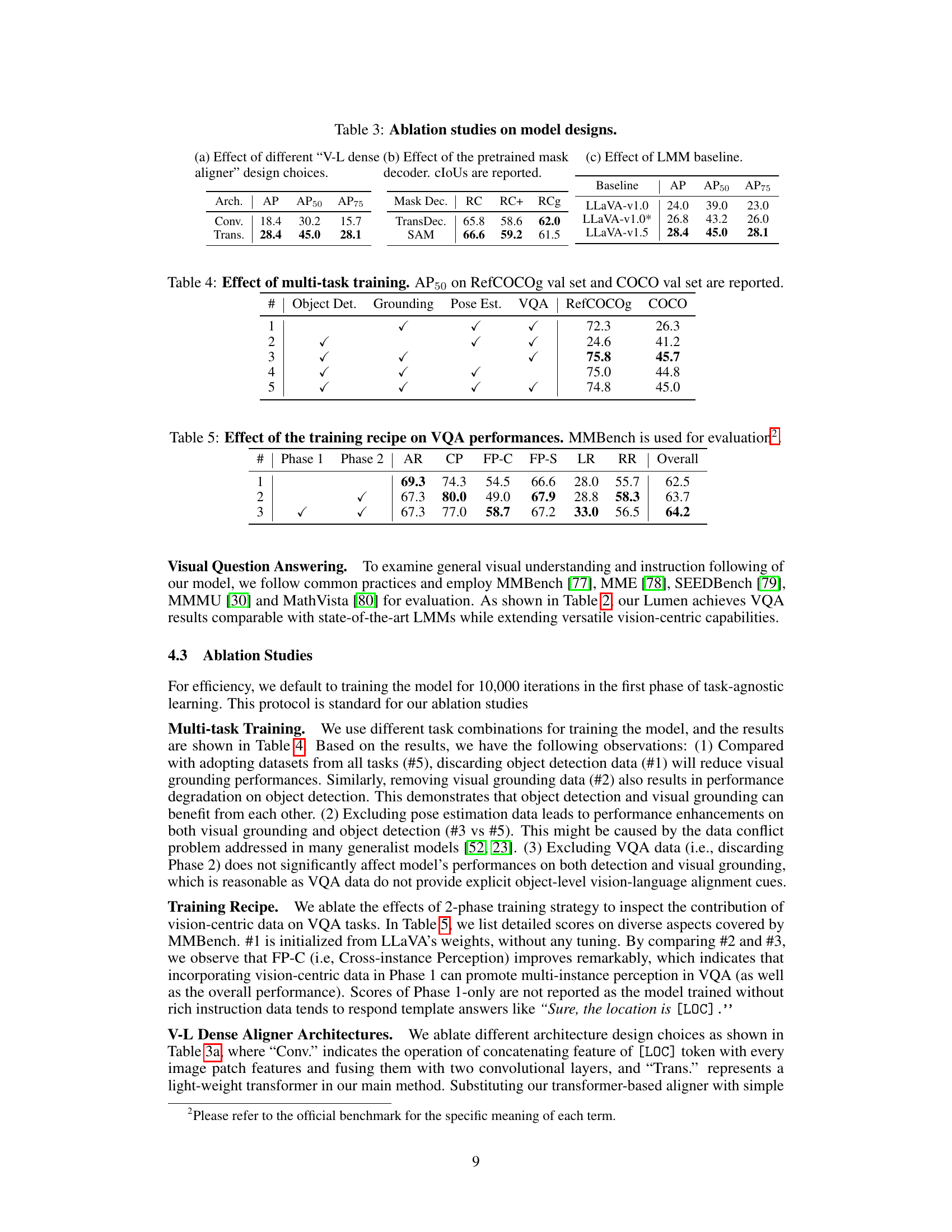

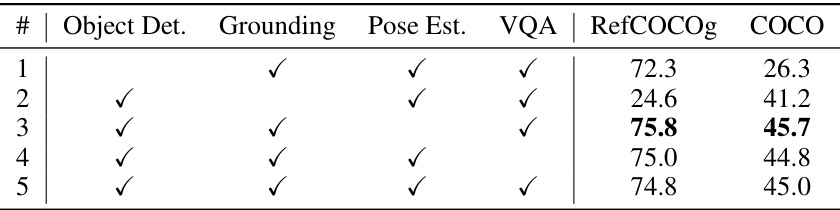

This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of multi-task training on the model’s performance. It shows the Average Precision at 50% Intersection over Union (AP50) for object detection on the COCO validation set and visual grounding on the RefCOCOg validation set. Different rows represent experiments where different combinations of tasks (object detection, visual grounding, pose estimation, and visual question answering) were included during training. The table demonstrates the effect of including or excluding specific tasks on the model’s performance on the two target benchmarks.

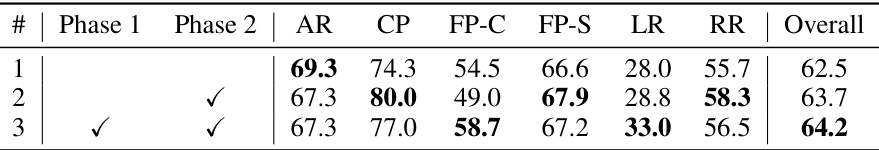

This table presents the ablation study on the effect of different training recipes on the visual question answering (VQA) performance. The MMBench benchmark is used for evaluation. Three training recipes are compared: using only Phase 1 data, using Phase 1 and Phase 2 data (with VQA data), and only using Phase 2 data (VQA data). The results are broken down into different metrics: Answer Rate (AR), Correct Percentage (CP), False Positives-Comprehensive (FP-C), False Positives-Simple (FP-S), Logical Reasoning (LR), Reading and Reasoning (RR), and Overall. The table highlights how different training phases and data sources impact the VQA performance.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed Lumen model’s performance against other state-of-the-art models on several vision-centric and vision-language tasks. It shows results for object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation, visual grounding, and referring segmentation. The table highlights Lumen’s performance relative to task-specific specialists (models designed for specific tasks), vision generalists (models that handle multiple visual tasks), and LMM generalists (large multimodal models). The table is structured to allow easy comparison across different model categories and task types.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed Lumen model’s performance against other state-of-the-art models on a variety of vision-centric and vision-language tasks. The vision-centric tasks include object detection, instance segmentation, and pose estimation, while the vision-language tasks include visual grounding and referring segmentation. The table shows the performance metrics (AP, AP50, AP75, etc.) for each task and model, highlighting Lumen’s strengths in both categories.

This table presents a comparison of various methods on object detection, instance segmentation, pose estimation, visual grounding, and referring segmentation tasks. It shows the performance of different models, categorized into task-specific specialists, vision generalists, and LMM generalists, across several metrics (AP, AP50, AP75, and cIoU). The table highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches to address these vision-centric tasks.

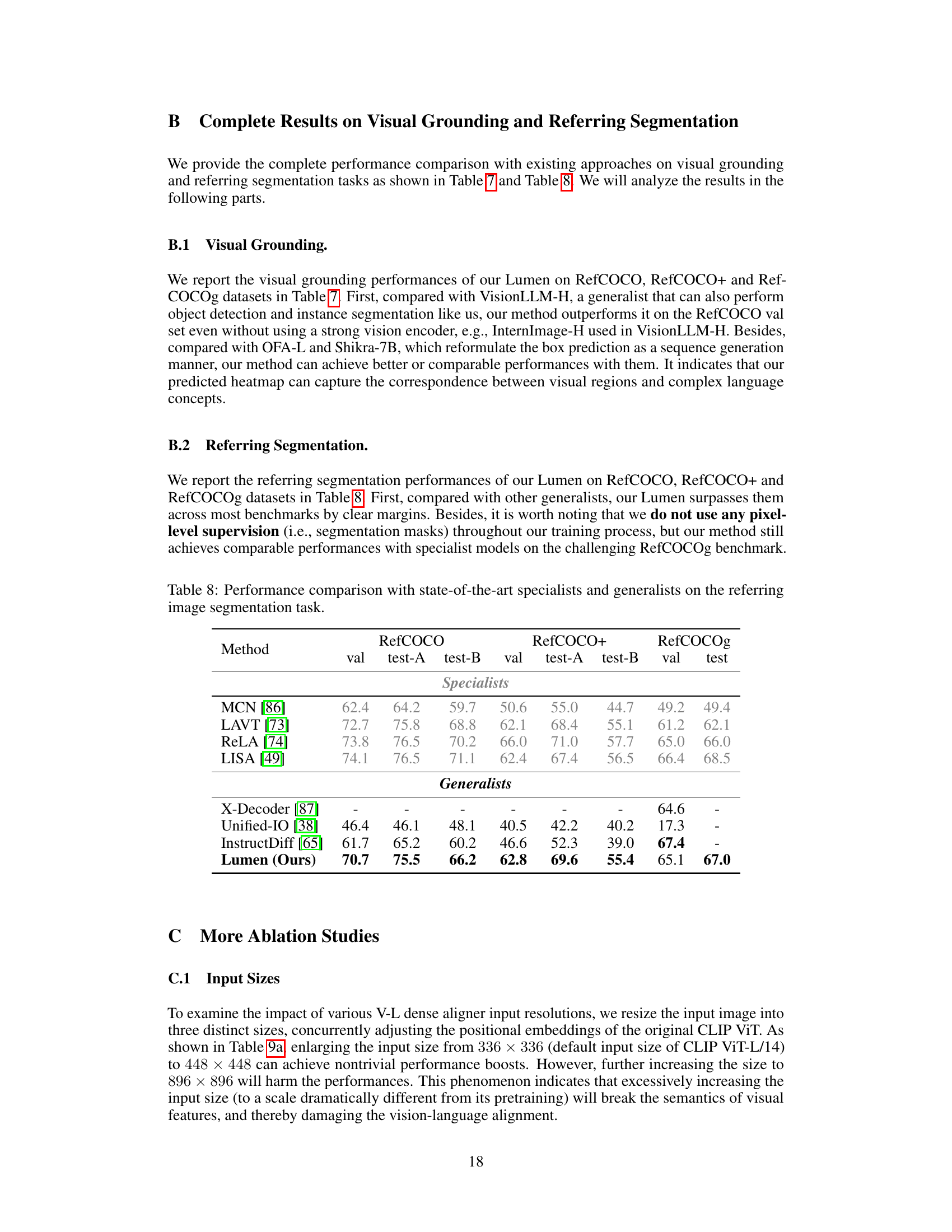

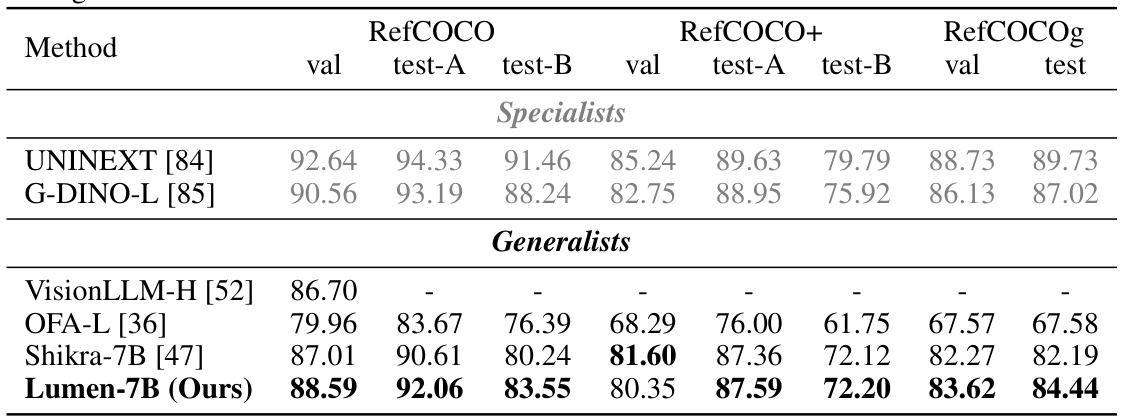

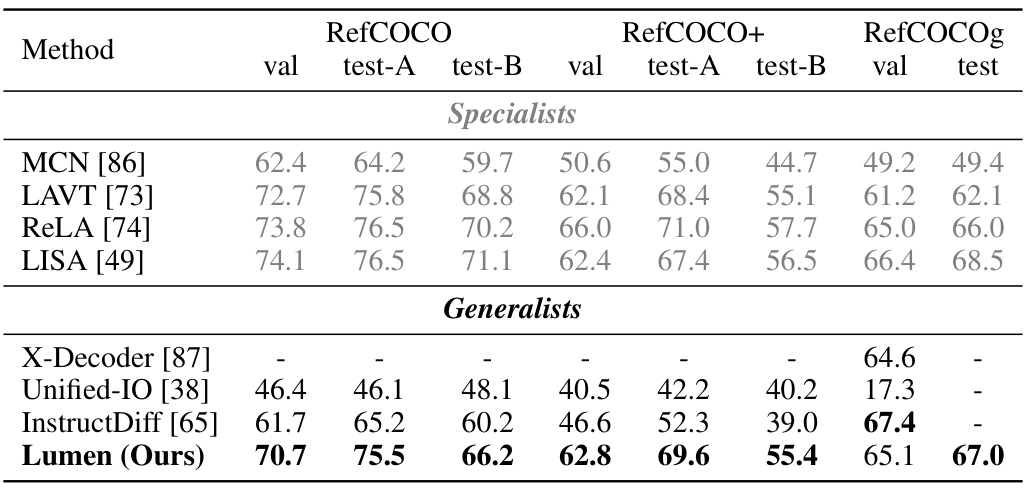

This table presents a comparison of the performance of Lumen against other state-of-the-art models on three visual grounding benchmarks: RefCOCO, RefCOCO+, and RefCOCOg. The table shows the performance of various methods (both specialists focusing on a single task and generalists tackling multiple visual tasks) using the ‘val’ and ’test’ splits of each benchmark. It highlights Lumen’s competitive performance, particularly in comparison to generalist models, in spite of not utilizing pixel-level supervision during training.

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different design choices on the model’s performance. Specifically, it examines the effect of various V-L dense aligner designs, the use of a pretrained versus a trained mask decoder, and different LMM baselines. The results are evaluated using Average Precision (AP) and Intersection over Union (IoU).

This table presents the ablation study results of the Lumen model. It shows the impact of different design choices on the model’s performance. Specifically, it investigates the effect of different V-L dense aligner designs, the impact of using a pretrained vs. a newly trained mask decoder, and the influence of different Large Multimodal Model (LMM) baselines on the model’s performance, measured by Average Precision (AP) and Intersection over Union (IoU).

This table presents the ablation study results of the Lumen model. It explores the impact of different components on the model’s performance. Specifically, it investigates the effect of the Vision-Language dense aligner’s design (convolutional vs. transformer-based), the effect of using a pre-trained mask decoder (SAM vs. a newly trained one), and the effect of using different Large Language Models (LLaVA-v1.0, LLaVA-v1.0*, LLaVA-v1.5) as the backbone. The results are evaluated in terms of Average Precision (AP), AP at 50% IoU (AP50), and AP at 75% IoU (AP75).

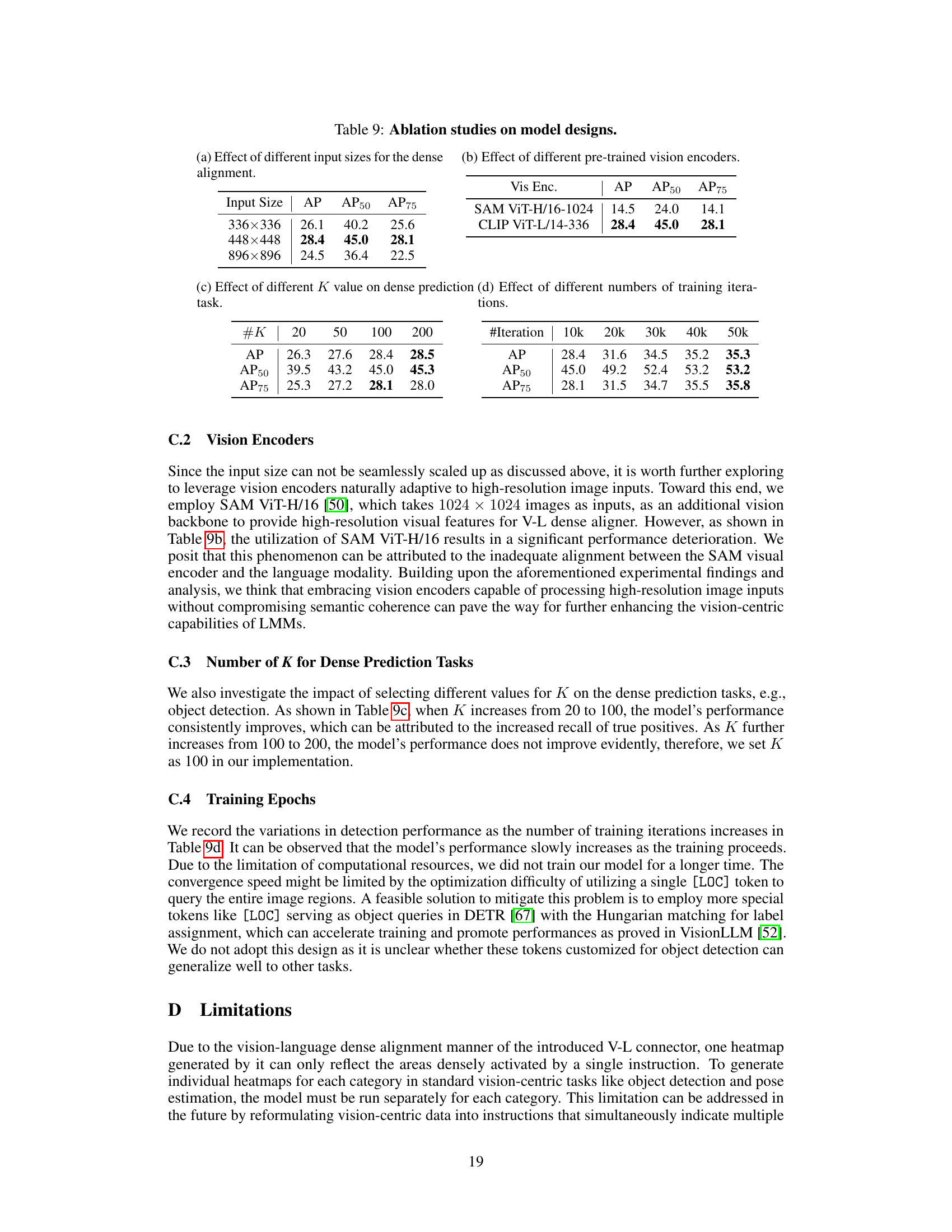

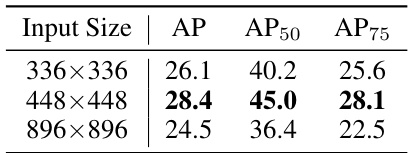

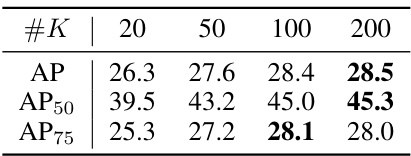

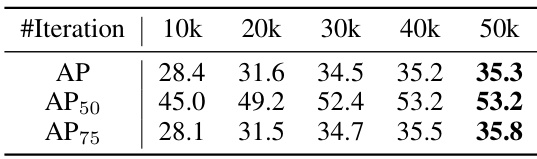

This table presents the ablation study results on Lumen’s model design. It shows the impact of different input sizes, vision encoders, K values for dense prediction, and the number of training iterations on the model’s performance, specifically measured by AP, AP50, and AP75.

Full paper#