↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current automatic code translation struggles with parallel programming due to limited parallel corpora for supervised learning. Unsupervised approaches have shown promise, but translating between languages and HPC extensions (e.g., C++ and CUDA) remains challenging due to complex parallel semantics. This makes it difficult to capture and replicate parallel code semantics accurately.

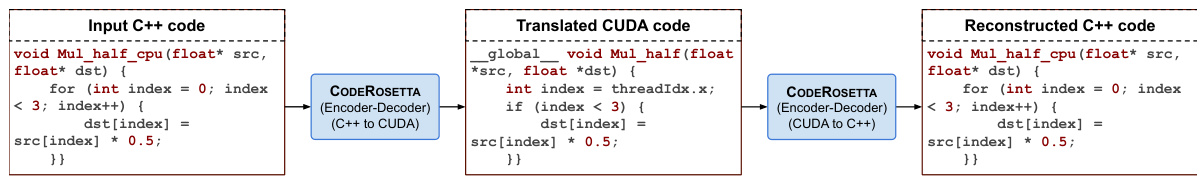

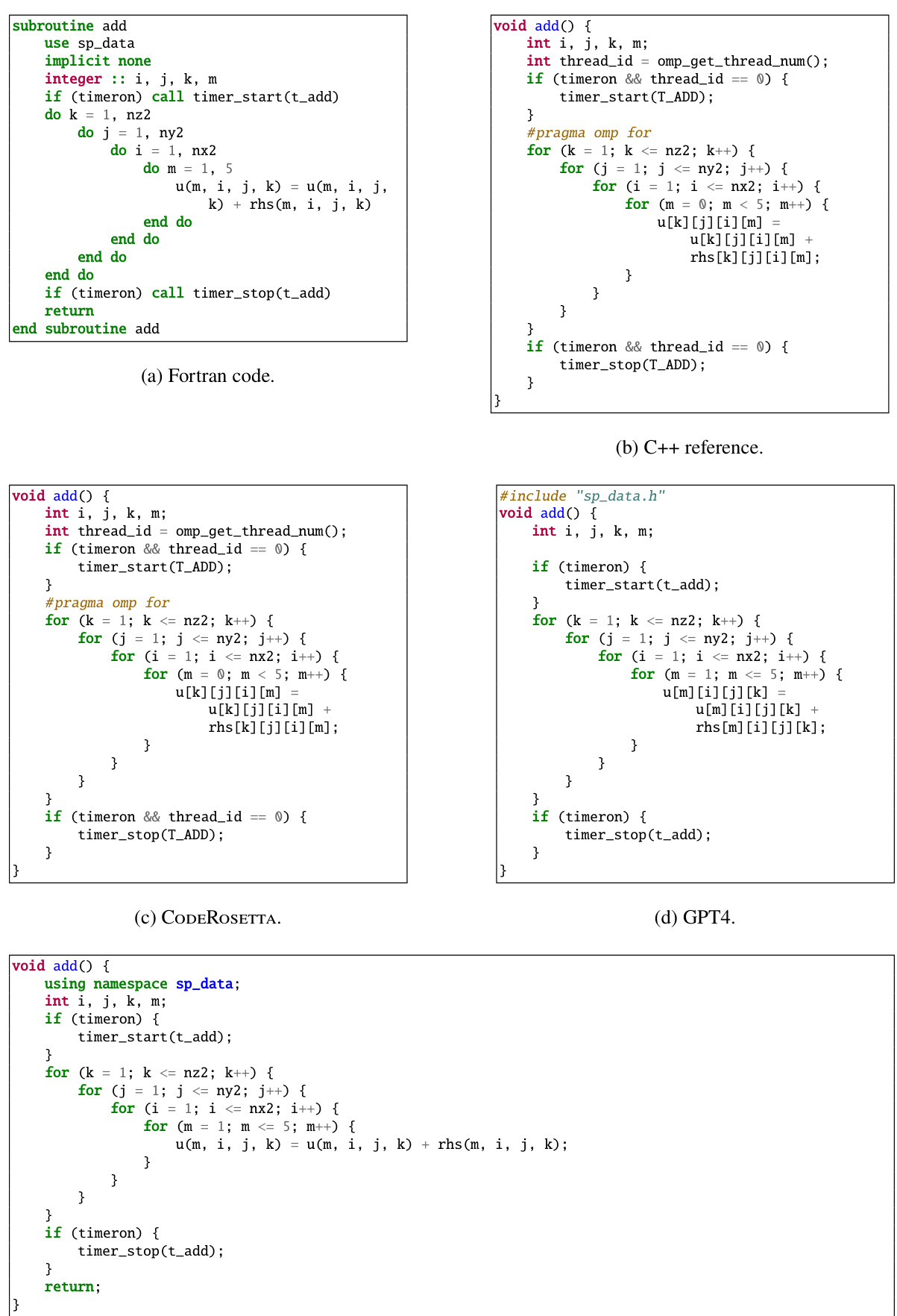

To address these issues, the paper introduces CODEROSETTA, a novel encoder-decoder transformer model tailored for unsupervised translation between programming languages and their HPC parallel extensions. CODEROSETTA uses a customized learning framework with tailored pre-training and training objectives to effectively capture code semantics and parallel structural nuances. The results demonstrate significant improvements over existing baselines in C++ to CUDA translation and introduce the first model capable of efficient Fortran to parallel C++ translation. The approach is bidirectional and uses a novel weighted token dropping and insertion mechanism.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents CODEROSETTA, the first unsupervised encoder-decoder model capable of translating between programming languages and their parallel extensions (C++ and CUDA, and Fortran to C++). This significantly advances unsupervised code translation and opens new avenues for research in high-performance computing, where paired datasets are scarce. The novel pre-training and training objectives (e.g., AER and tailored DAE) and the model’s bidirectional translation capability are valuable contributions.

Visual Insights#

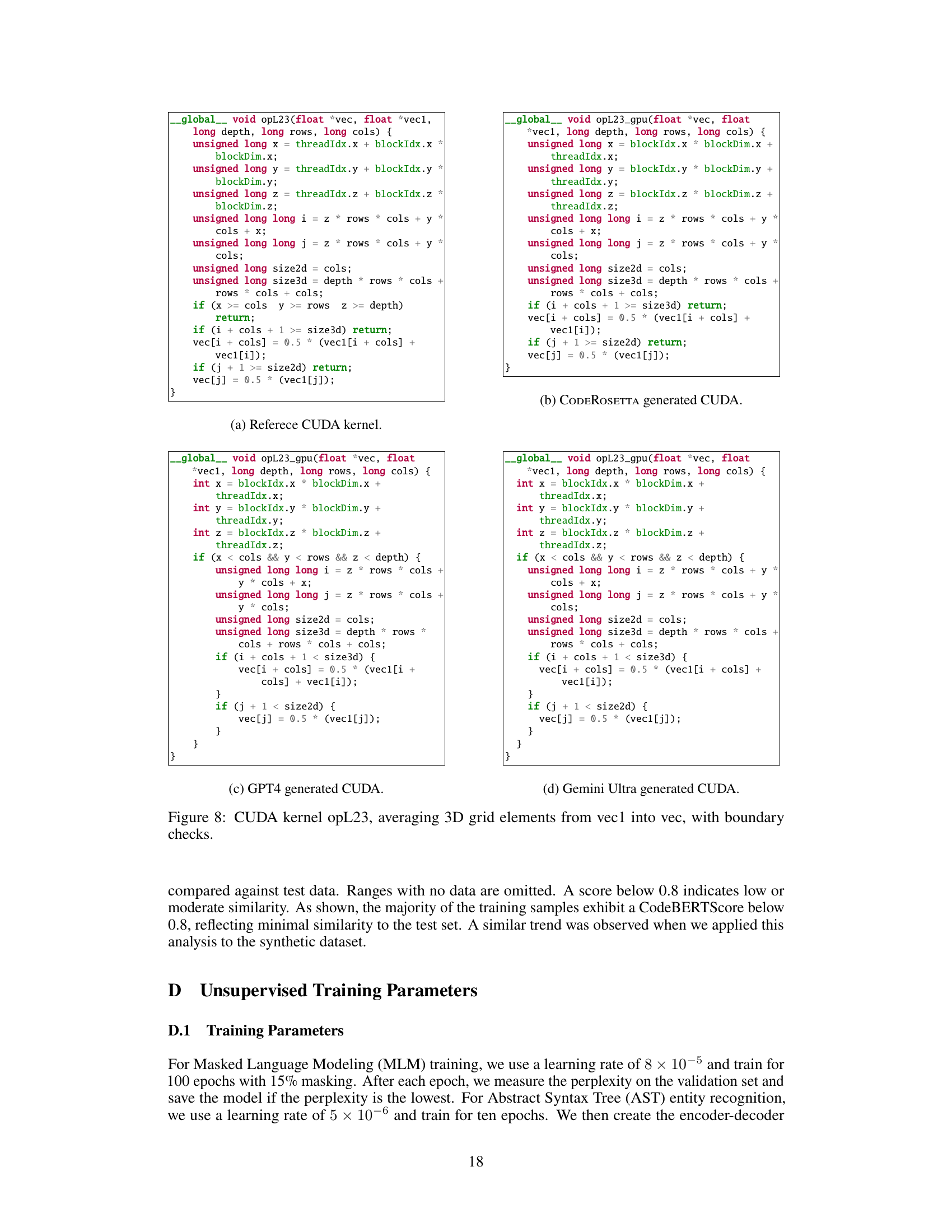

🔼 This figure illustrates the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) pre-training process used in CODEROSETTA. The input CUDA code is shown, with some tokens masked (represented as

). CODEROSETTA’s encoder then attempts to predict these masked tokens based on the context of the surrounding code. The reconstructed code is shown after this process. This pre-training helps CODEROSETTA develop a foundational understanding of programming languages by learning both syntactic patterns and semantic relationships. read the caption

Figure 1: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) pretraining steps in CODEROSETTA.

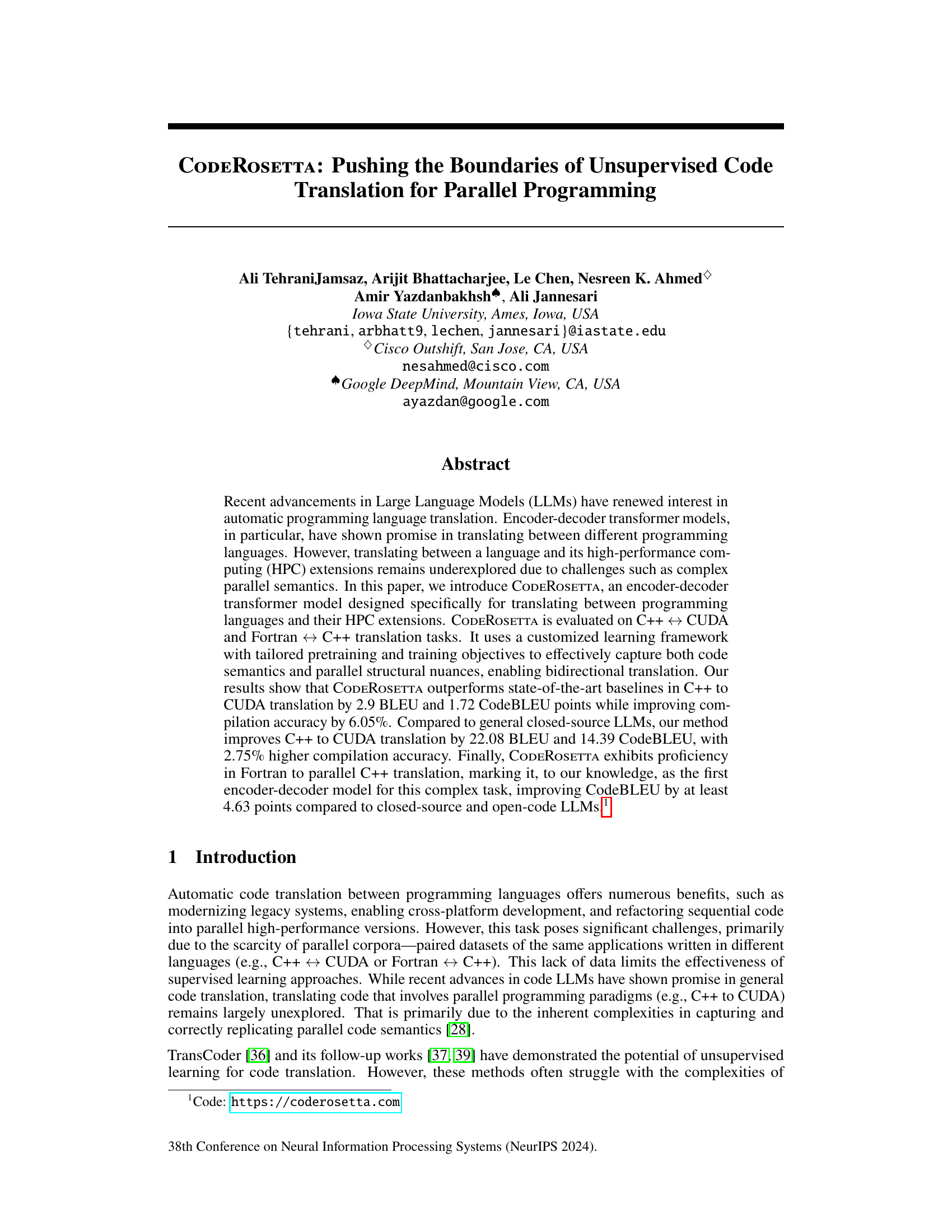

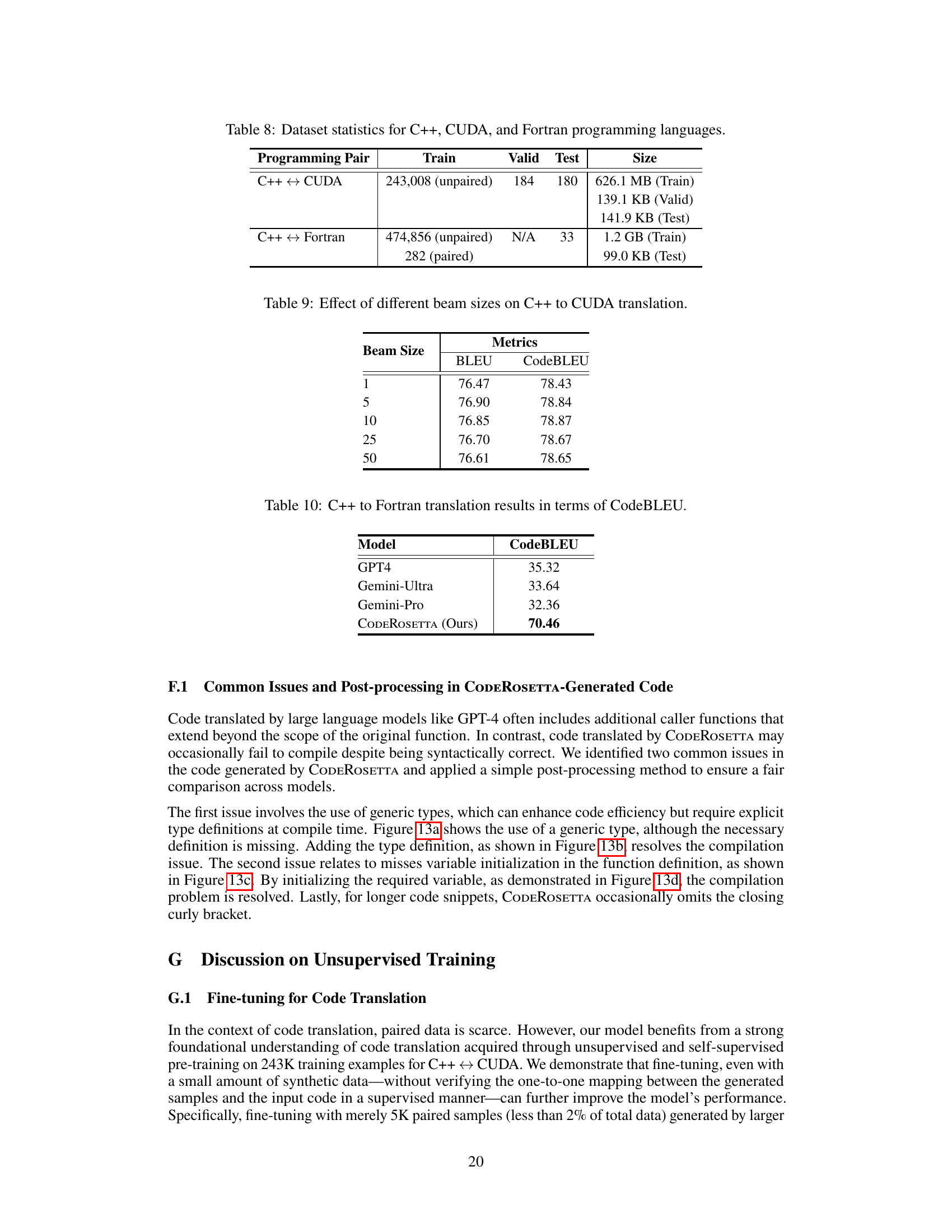

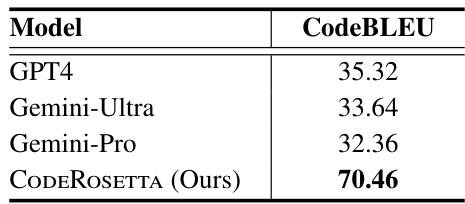

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the C++ to CUDA translation task performed by CODEROSETTA and several other models (GPT4, Gemini-Ultra, Gemini-Pro, DeepSeekCoder, StarCoder, TransCoder, and BabelTower). The metrics used to evaluate the translation quality are BLEU, CodeBLEU, ChrF, and ROUGE-L. Compilation accuracy, representing the percentage of successfully compiled translated code, is also included. Underlining highlights the second-best performance for each metric, demonstrating CODEROSETTA’s improved performance compared to the state-of-the-art baselines.

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of C++ to CUDA translation results across various code metrics and compilation accuracy. Second-best results are underlined.

In-depth insights#

Unsupervised Xlation#

Unsupervised machine translation of code presents significant challenges due to the complexity of programming languages and the scarcity of parallel corpora. CODEROSETTA addresses this by employing a novel encoder-decoder transformer model trained without paired datasets. The model leverages innovative pre-training techniques including masked language modeling and abstract syntax tree entity recognition to develop a strong understanding of code semantics and structure. A customized denoising auto-encoding scheme with adaptive noise injection further refines the model’s ability to handle the nuances of parallel programming paradigms. This approach eliminates the reliance on language-specific metrics seen in previous work. The results demonstrate CODEROSETTA’s proficiency in bidirectional translation between C++ and CUDA, Fortran and C++, outperforming existing baselines and showcasing the efficacy of unsupervised learning for this challenging problem. However, certain limitations remain, primarily regarding the handling of complex code constructs and a reliance on post-processing to improve compilation success rates. Future work could address these issues through refinement of the noise injection strategies and integration of more sophisticated error handling mechanisms.

Parallel Code Focus#

A hypothetical research paper section titled ‘Parallel Code Focus’ would delve into the specific challenges and techniques related to translating code that leverages parallel programming paradigms. It would likely highlight the complexities of mapping parallel constructs from one language (e.g., C++) to another (e.g., CUDA) while preserving the original code’s semantics and performance. The section would emphasize the need for specialized models or training techniques that can effectively capture parallel code structure and semantics, including considerations for thread management, synchronization, memory access patterns, and other HPC-specific features. The discussion might involve comparisons to existing translation methods to demonstrate the limitations of applying general-purpose code translation techniques to parallel code and showcase the benefits of the proposed approach, especially when it comes to achieving efficient, accurate, and functionally correct translations. Specific examples of parallel code constructs and their translation complexities would be valuable. Additionally, the section might touch upon the evaluation metrics used to assess the quality and performance of parallel code translations, perhaps contrasting them with metrics suitable for sequential code, and discussing the evaluation criteria used to assess correctness in translated parallel code.

Custom Training#

The concept of ‘Custom Training’ in the context of a machine learning model for code translation signifies a departure from standard, generalized training methodologies. It suggests the implementation of specialized training objectives and data preprocessing techniques tailored to the nuances of parallel programming languages and their extensions (like CUDA and HPC). This approach likely involves the careful crafting of a training curriculum that focuses on aspects such as parallel code semantics, syntax, and structural patterns, potentially using custom loss functions and metrics. Furthermore, it implies a deeper understanding of the target language’s characteristics and intricacies, which informs the selection and augmentation of training data and the development of noise-injection strategies within the training process. By focusing on this customized training, the model can learn to overcome challenges associated with the ambiguity inherent in general-purpose code translations, thus improving the accuracy and efficiency of parallel code generation. The efficacy of this approach is heavily reliant on the quality and relevance of the custom data used and the careful design of the training objectives.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically evaluates the contribution of individual components within a machine learning model. In the context of a code translation model like the one described, this would involve removing one component at a time (e.g., removing Masked Language Modeling, Abstract Syntax Tree Entity Recognition, or the custom noise injection techniques from the Denoising Autoencoding) and retraining the model. By comparing the performance of the reduced model against the full model, researchers can determine the importance of each component to the model’s overall effectiveness. The results of an ablation study often reveal unexpected dependencies or synergies between different parts of the model. For example, removing a seemingly minor component might have a surprisingly large negative impact on performance, suggesting that the component plays a more crucial role than initially anticipated. Conversely, the impact might be minimal, showing that particular component is less vital than others. A well-designed ablation study is crucial for understanding the model’s architecture and identifying key areas for future improvements or modifications. The study helps justify design choices by demonstrating the value of each specific component included. This granular analysis provides critical insights into how the model learns and translates code.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending CodeRosetta’s capabilities to a wider array of programming languages and parallel paradigms beyond C++, CUDA, and Fortran. Improving the model’s handling of complex control flow and data structures within parallel code is crucial for enhanced accuracy and robustness. Investigating techniques to better integrate compiler feedback during training could significantly boost compilation success rates and code quality. Furthermore, developing more sophisticated metrics for evaluating the functional correctness of generated parallel code beyond simple compilation checks is important. Finally, exploring methods to leverage larger language models’ capabilities more effectively for data augmentation or fine-tuning without incurring significant computational costs would be a valuable area of investigation. Addressing potential biases in the training data and ensuring fairness and robustness across diverse programming styles would also be a worthwhile pursuit.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the Abstract Syntax Tree Entity Recognition (AER) pre-training step in the CODEROSETTA model. The input is CUDA code. Tree-sitter is used to generate the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). From the AST, entities and their corresponding categories are extracted (e.g., function, variable, constant, pointer, literal). CODEROSETTA (the encoder) then predicts the syntactic category of each token based on its role in the AST. Tokens without a specific category are labeled as ‘O’ (Outside). This pre-training allows CODEROSETTA to understand the code structure and relationships between code elements, which aids in accurate translation and generation of code across languages and extensions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Abstract Syntax Tree Entity Recognition pretraining steps in CODEROSETTA.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Denoising Auto-Encoding (DAE) training strategy used in CODEROSETTA. The input CUDA code is first corrupted using various noise injection techniques (dropping, inserting, shuffling, masking). The corrupted code is then fed into the CODEROSETTA encoder-decoder model, which attempts to reconstruct the original, noise-free code. This process helps the decoder learn the underlying syntactic rules of the target language and the ability to recover meaningful code from perturbed inputs, simulating the challenges of translating real-world code with potential variations and inconsistencies. The adaptive noise injection methods used are highlighted.

read the caption

Figure 3: Denoising Auto Encoding.

🔼 This figure illustrates the back-translation process used in the CODEROSETTA model. The model first translates C++ code to CUDA code. Then, the generated CUDA code is used as input to translate it back to C++. By comparing the reconstructed C++ code to the original input, CODEROSETTA refines its understanding and improves the accuracy of its translations in both directions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Back Translation.

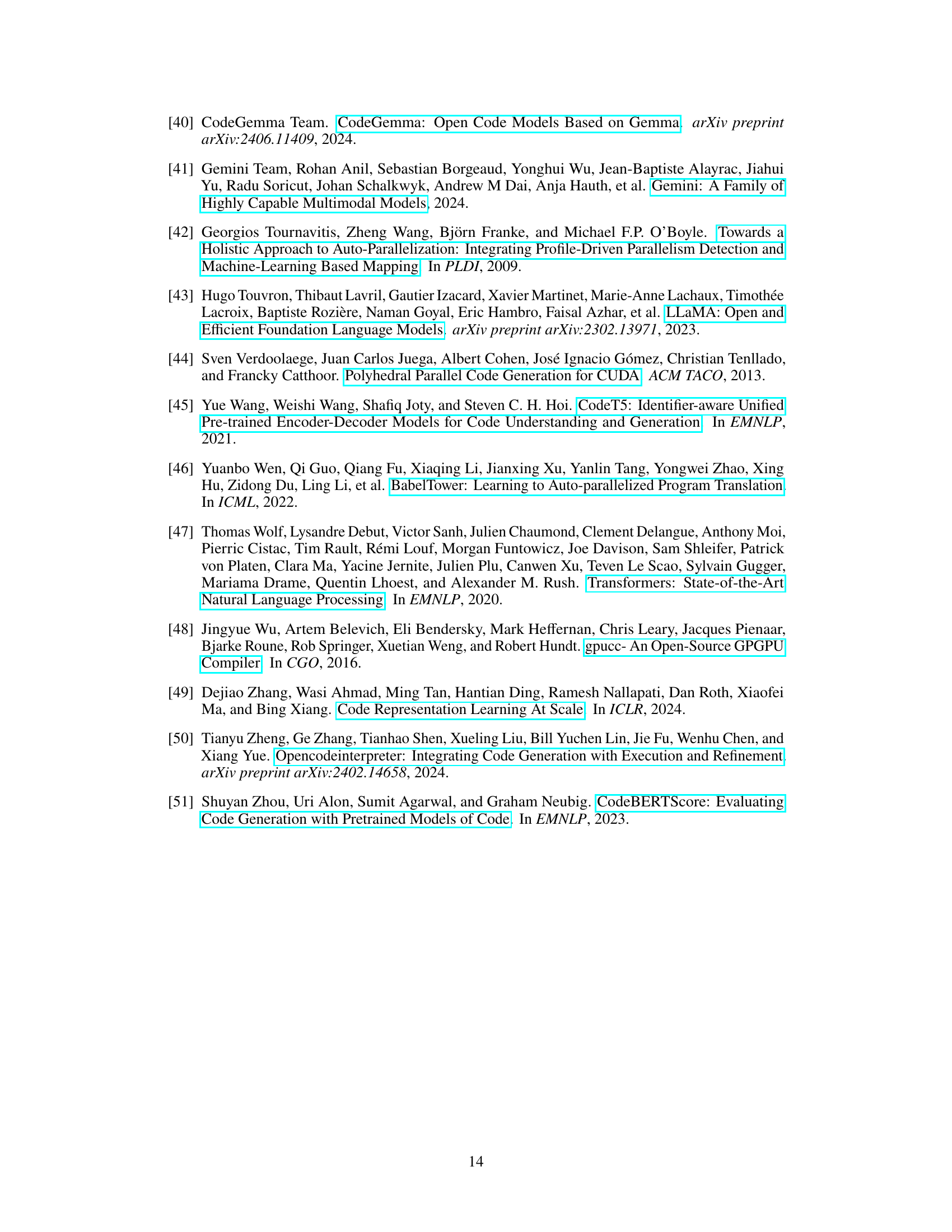

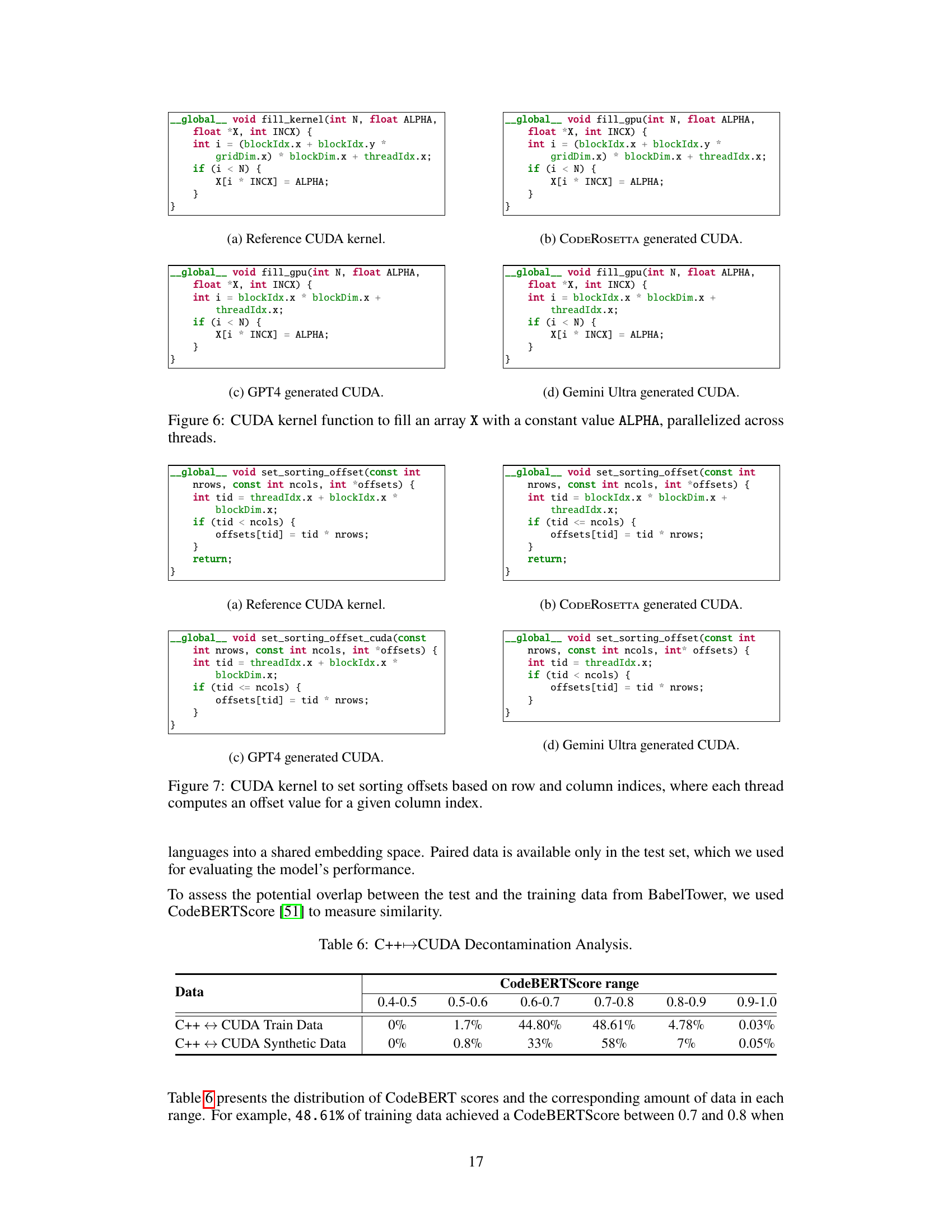

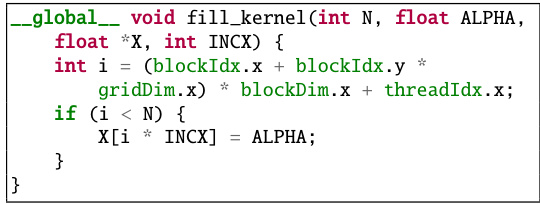

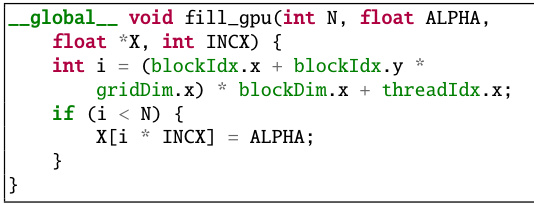

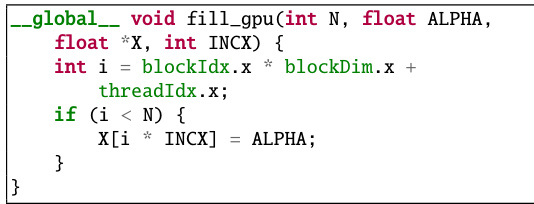

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra for a kernel function that fills an array with a constant value. The reference CUDA kernel code is shown alongside the generated code snippets. The illustration highlights how CODEROSETTA successfully identifies the optimal 2D grid structure for parallelization, unlike GPT4 and Gemini Ultra which default to less efficient 1D structures. The optimal grid structure significantly improves the performance of the CUDA kernel.

read the caption

Figure 6: CUDA kernel function to fill an array X with a constant value ALPHA, parallelized across threads.

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel function designed to fill an array X with a constant value ALPHA. The parallelization is achieved across threads, each thread calculating its global index i and assigning ALPHA to the corresponding element of X if the index is within the array’s bounds. The image presents a comparison between the reference CUDA code and the code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4 and Gemini Ultra. CODEROSETTA’s generated code correctly implements the 2D grid structure that is optimal for CUDA performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: CUDA kernel function to fill an array X with a constant value ALPHA, parallelized across threads.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of CUDA kernel code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra, against the reference CUDA kernel. Each model is tasked with filling an array X with a constant value ALPHA, parallelized across threads. The comparison highlights differences in the approaches to thread indexing and grid structure used by each method. CODEROSETTA’s generated code is noted to more closely resemble the structure of the reference implementation, which indicates a more efficient approach to parallelization.

read the caption

Figure 6: CUDA kernel function to fill an array X with a constant value ALPHA, parallelized across threads.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra for filling an array with a constant value. The reference CUDA kernel is also shown. CODEROSETTA and the reference implementation both use a 2D grid structure for optimal parallelization, which is more efficient than the 1D structure used by GPT4 and Gemini Ultra. The difference in grid structure significantly impacts performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: CUDA kernel function to fill an array X with a constant value ALPHA, parallelized across threads.

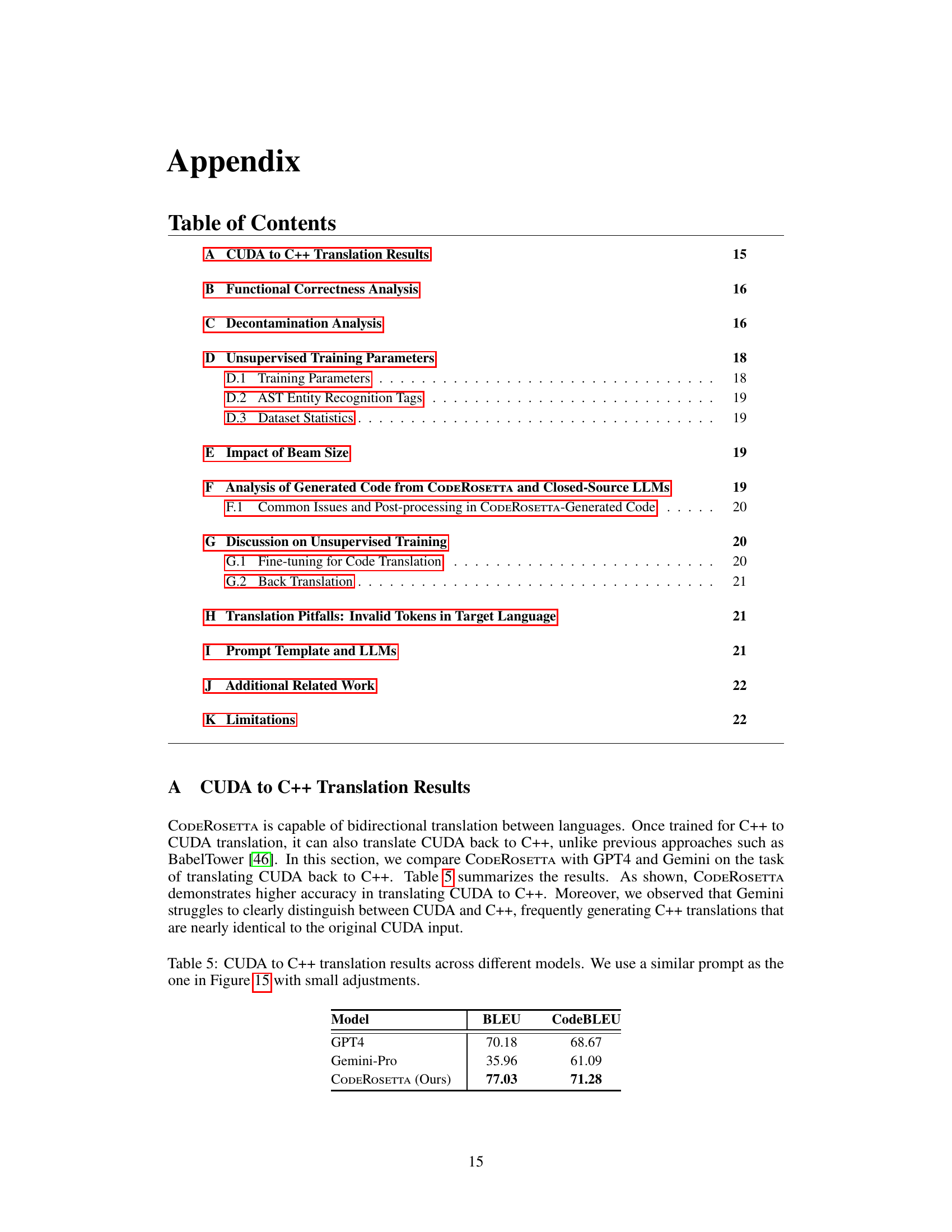

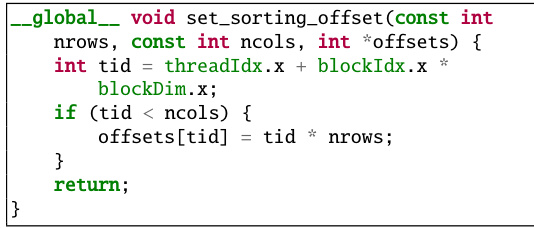

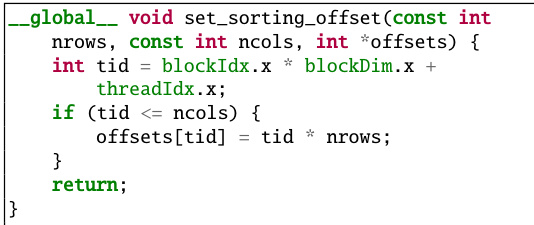

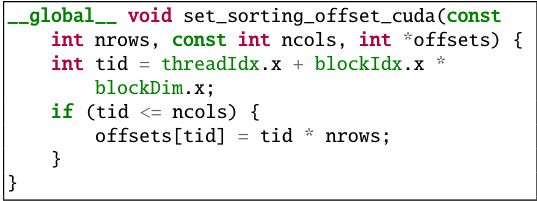

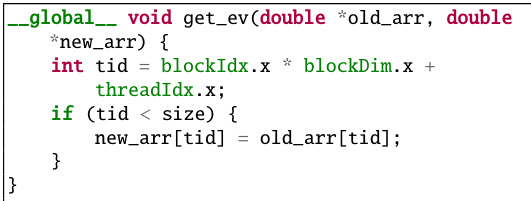

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel’s code designed to set sorting offsets. Each thread in the kernel calculates the offset corresponding to its column position in a flattened 2D grid. This offset indicates where the column’s data starts within a larger, one-dimensional array. The efficient calculation of offsets is crucial for parallel sorting algorithms, as it helps threads quickly locate their assigned portions of data.

read the caption

Figure 7: CUDA kernel to set sorting offsets based on row and column indices, where each thread computes an offset value for a given column index.

🔼 This figure showcases a CUDA kernel designed to compute sorting offsets. Each thread calculates an offset value based on its thread index within a block and the block index within a grid. The offsets are then stored in a shared memory array. This approach is efficient for parallel sorting algorithms, where each thread needs to know the starting position of a column in a flattened 2D grid, allowing for parallel operations.

read the caption

Figure 7: CUDA kernel to set sorting offsets based on row and column indices, where each thread computes an offset value for a given column index.

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel designed to set sorting offsets. Each thread in the kernel computes an offset value based on its row and column indices. The figure helps illustrate how parallel processing is handled in the CUDA context. The specific computation done by the kernel is relevant for algorithms that require column-wise processing, such as parallel sorting algorithms. The use of

threadIdx.x,blockIdx.x, andblockDim.xindicates the parallelization scheme and memory addressing. The code snippet is presented to show the implementation details of how offsets are calculated and assigned in parallel for optimized performance.read the caption

Figure 7: CUDA kernel to set sorting offsets based on row and column indices, where each thread computes an offset value for a given column index.

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel’s code designed to compute sorting offsets. Each thread in the kernel calculates an offset value based on its thread ID (threadIdx.x) and block index (blockIdx.x) to determine the starting position of a column in a flattened 2D array. The correctness of the offset calculation is crucial for parallel sorting algorithms where each thread needs to work on a distinct portion of the data. Incorrect offset calculation can lead to data races and incorrect results. The figure highlights the importance of parallel programming concepts like thread indexing and block indexing in efficient CUDA kernel development.

read the caption

Figure 7: CUDA kernel to set sorting offsets based on row and column indices, where each thread computes an offset value for a given column index.

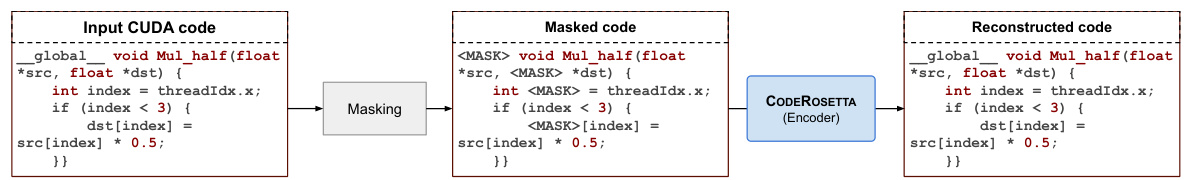

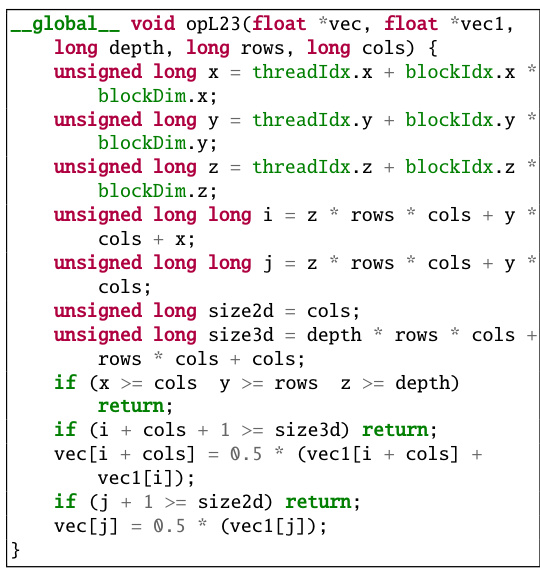

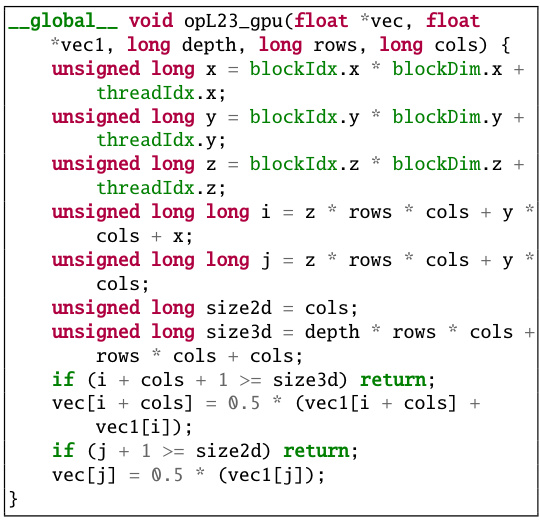

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel named

opL23. The kernel takes four arguments:vec,vec1,depth,rows, andcols. It performs a parallel averaging operation on a 3D array. Each thread calculates its 3D index (i,j,k). Boundary checks (ifstatements) prevent out-of-bounds memory accesses. The kernel calculates weighted averages of elements fromvec1and stores the results invec.read the caption

Figure 8: CUDA kernel opL23, averaging 3D grid elements from vec1 into vec, with boundary checks.

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel named

opL23_gputhat performs a 3D array averaging operation. It iterates through a 3D array (vec1), calculates the average of selected elements, and stores the results in another 3D array (vec). The kernel efficiently handles boundary conditions, ensuring that it only processes valid elements within the array dimensions. Each thread in the kernel is assigned a unique 3D index (x, y, z) to access and process specific elements in the arrays. The kernel also employs unsigned long long integers for indexing, preventing potential integer overflow issues when working with large arrays.read the caption

Figure 8: CUDA kernel opL23, averaging 3D grid elements from vec1 into vec, with boundary checks.

🔼 The figure shows a CUDA kernel named

opL23_gputhat performs a 3D array averaging operation. The kernel takes four arguments:vec(output array),vec1(input array),depth,rows, andcols(array dimensions). Each thread in the kernel calculates its 3D index (x, y, z) and then accesses elements fromvec1to compute a weighted average which is stored invec. Boundary checks (ifstatements) ensure that threads don’t try to access memory outside the array bounds.read the caption

Figure 8: CUDA kernel opL23, averaging 3D grid elements from vec1 into vec, with boundary checks.

🔼 This figure shows a CUDA kernel named

opL23_gpu. The kernel takes four arguments:vec,vec1,depth,rows, andcols, representing two input arrays and the dimensions of a 3D grid. Each thread in the kernel calculates its 3D index (x, y, z) and then computes a weighted average of elements fromvec1and stores the result invec. Boundary checks are implemented to prevent out-of-bounds access to the arrays. The specific calculation averages values fromvec1and stores the results invec, ensuring that the kernel handles boundary conditions correctly.read the caption

Figure 8: CUDA kernel opL23, averaging 3D grid elements from vec1 into vec, with boundary checks.

🔼 This figure shows a code example demonstrating thread synchronization in C++ using OpenMP. It compares the reference C++ code (using OpenMP directives) with the C++ code generated by CODEROSETTA and other LLMs (GPT-4 and Gemini Ultra). The example highlights a scenario where two threads access and modify a shared variable (x and y). The synchronization mechanisms (atomic operations, critical sections, and memory fences) employed by each implementation are compared and discussed. The figure illustrates the subtleties and challenges involved in correctly translating code that relies on parallel programming constructs and synchronization primitives, underscoring the complexities of automated code translation.

read the caption

Figure 9: A C++ OpenMP example with thread sync using atomic operations and critical sections.

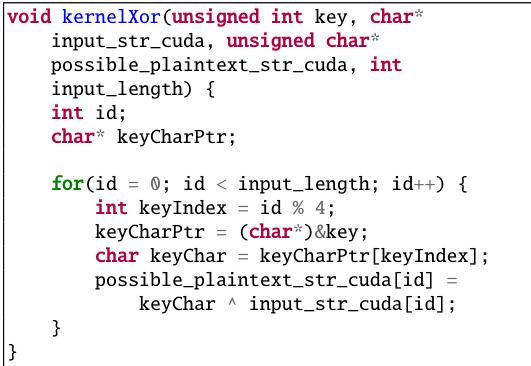

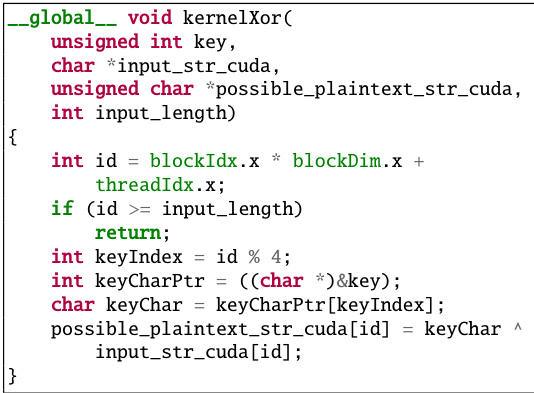

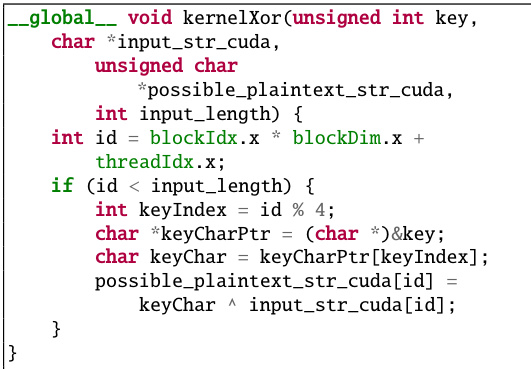

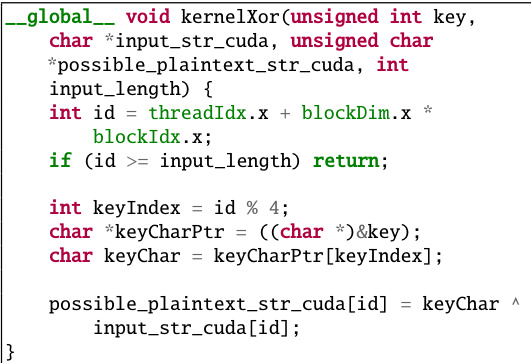

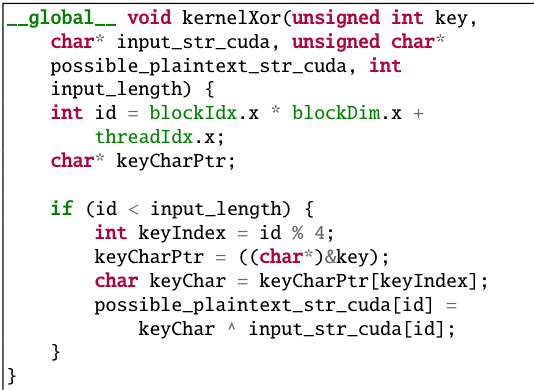

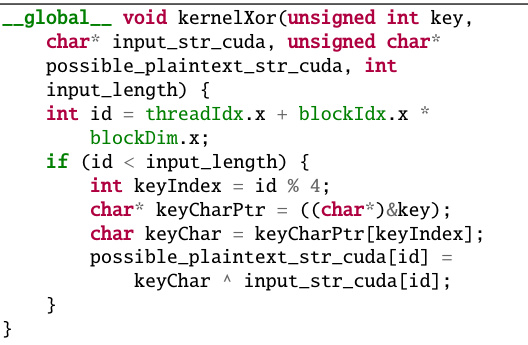

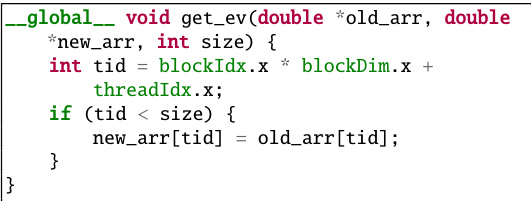

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA with the reference CUDA code and the code generated by BabelTower, GPT4 and Gemini Ultra for the kernelXor function. The kernelXor function takes an unsigned integer key, a character array input_str_cuda, an unsigned character array possible_plaintext_str_cuda, and the input length as input. It iterates through the input string, XORing each character with a character from the key. The key character is selected based on the index modulo 4. The figure shows that CODEROSETTA generates CUDA code that is similar to the reference code, while the other methods produce different results, highlighting CODEROSETTA’s superior performance in this specific example.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA kernel generated by CODEROSETTA with those generated by BabelTower, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra. The kernel performs an XOR operation between an input string and a key. CODEROSETTA’s generated code is efficient, accurately reflecting the reference CUDA code’s functionality and structure. In contrast, BabelTower’s version contains additional unnecessary code and uses incorrect data types. GPT4 and Gemini Ultra’s versions are comparable to CODEROSETTA’s, though not as concise.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA code generated by different models for the kernelXor function. The original C++ code is shown alongside the CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA, BabelTower, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra. The comparison highlights differences in code style and structure, illustrating the various approaches taken by different models to translate from C++ to CUDA. It reveals variations in the approaches to handling language-specific components and parallel constructs, ultimately showing how the different models’ understanding of the code leads to diverse implementations.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA kernel code generated by different methods (C++, CUDA reference, BabelTower, CODEROSETTA, Gemini Ultra, GPT4) for a kernelXor function. The kernel takes an unsigned integer key, character arrays (input_str_cuda and possible_plaintext_str_cuda), and input length as inputs. Each method’s implementation of the kernel is shown, highlighting the differences in code structure and style. The comparison helps to illustrate the variations in code generation between different approaches and the relative performance of the CODEROSETTA model.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA kernel generated by CODEROSETTA with the reference CUDA kernel, BabelTower, Gemini Ultra, and GPT-4. The kernel performs a bitwise XOR operation between an input string and a key. The comparison highlights the differences in code generation approaches across different models, particularly concerning the handling of thread indexing and key management. CODEROSETTA’s code shows similarity with the reference CUDA kernel, suggesting a more accurate translation.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA kernel generated by CODEROSETTA with those generated by BabelTower, Gemini Ultra, and GPT-4. The C++ code and CUDA reference are also shown. The goal was to perform a bitwise XOR operation between a key and an input string, parallelized across threads. The comparison highlights differences in code style, efficiency, and handling of language-specific elements (like the use of pointers). CODEROSETTA’s version demonstrates proficiency in generating clean, correct, and efficient CUDA code, comparable to, or even exceeding, the performance of other large language models.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison of the generated kernelXor CUDA kernel.

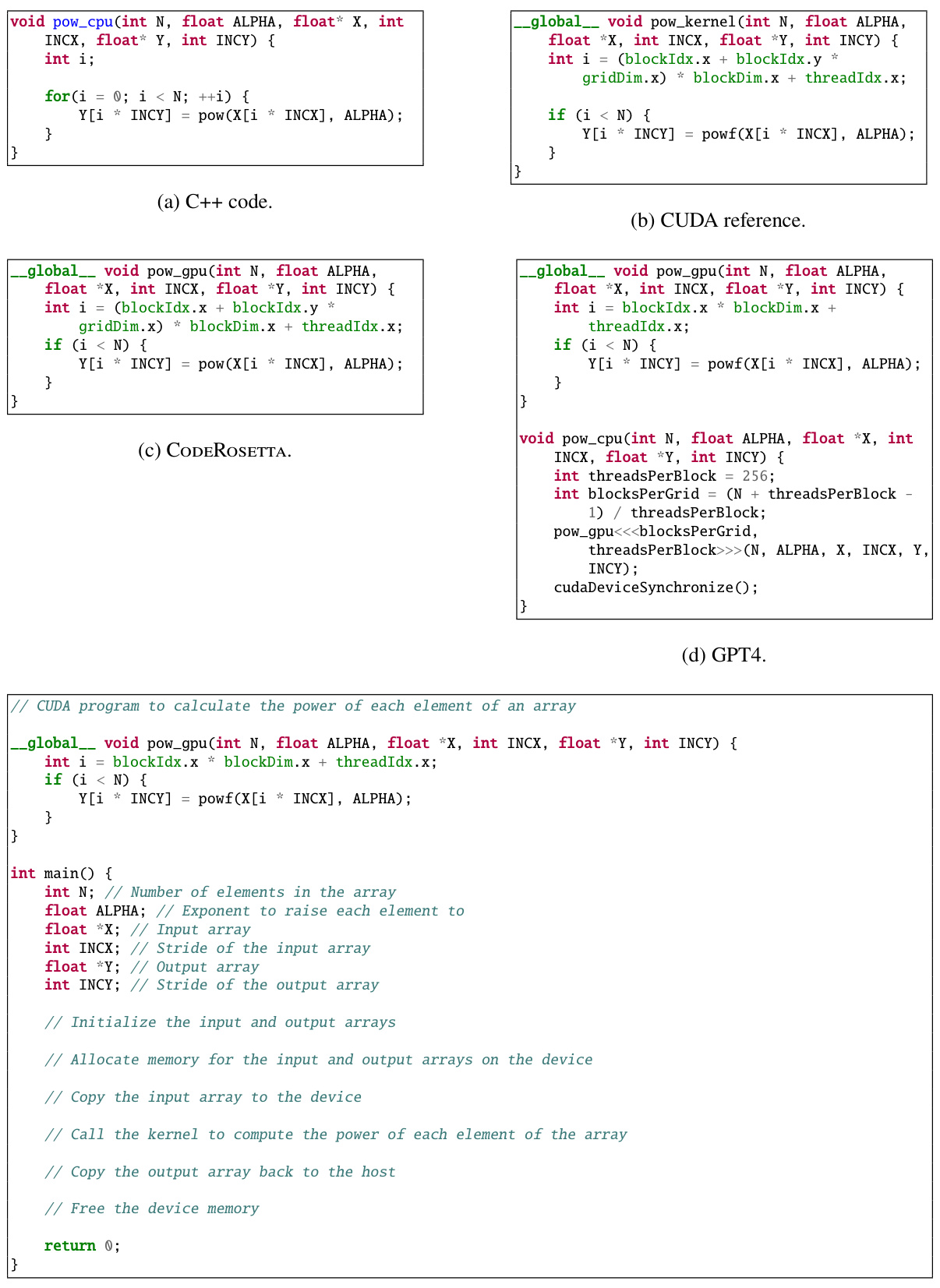

🔼 This figure compares the CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra for calculating the power of each element in an array. CODEROSETTA’s generated code is concise and correct, similar to the reference CUDA kernel. GPT4’s code includes unnecessary setup code like device synchronization which is not needed for the single kernel call shown, and Gemini Ultra’s code includes comments describing the purpose of the code, which would be unnecessary in a practical context.

read the caption

Figure 11: Power of elements CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) pre-training process used in CODEROSETTA. The model takes C++ or CUDA code as input, masks a portion of the tokens randomly, and attempts to predict these masked tokens based on the surrounding context. The objective is to train the model to understand both local syntactic patterns and broader semantic relationships within the code, improving its ability to translate unseen code patterns. The process is shown in three steps: Masking (where tokens are replaced with

), the CODEROSETTA encoder which processes the masked code, and finally the Reconstruction, where the masked tokens are predicted. read the caption

Figure 1: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) pretraining steps in CODEROSETTA.

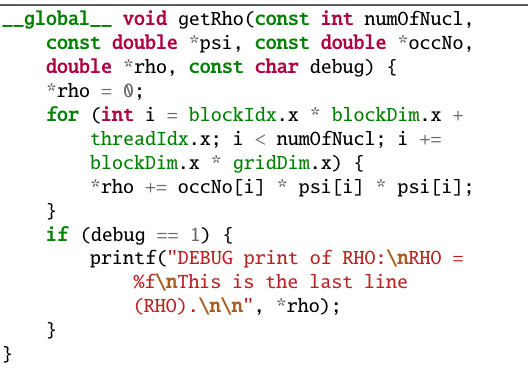

🔼 This figure shows examples of CUDA code generated by the model with compilation errors and the corrected versions. The compilation errors are related to undefined generic types and missing closing braces, which are easily fixed with minor modifications. The figure highlights the need for minor post-processing and that most of the compilation errors are trivial and easily fixed.

read the caption

Figure 13: Post Compilation fixes on CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure shows examples of CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA that contains minor errors that cause compilation failure. It highlights the simple fixes that can be applied to the generated code to resolve the compilation issues and achieve successful compilation. These simple fixes include adding type definitions, initializing variables, and adding closing brackets.

read the caption

Figure 13: Post Compilation fixes on CUDA kernel.

🔼 The figure shows examples of CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA that produced compilation errors, along with the corresponding corrected versions. The compilation errors shown were due to missing type definitions and missing variable initialization, both of which are common issues that can arise when automatically generating code. The corrected examples highlight how easily these issues can be fixed with minor edits, improving the overall compilation accuracy of the model.

read the caption

Figure 13: Post Compilation fixes on CUDA kernel.

🔼 This figure shows examples of CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA that initially contained compilation errors, and the corrected versions of the code. The errors shown are missing type declarations and missing variable initializations. The corrected versions show the simple changes required to fix the compilation errors. These examples highlight that many of the compilation errors produced by CODEROSETTA are trivial and easily fixed.

read the caption

Figure 13: Post Compilation fixes on CUDA kernel.

🔼 The figure shows the intermediate results of back translation. The left side shows the input C++ code. The right side shows the CUDA code generated by the model during back translation. The example demonstrates an intermediate step in the back-translation process, highlighting how the model translates between C++ and CUDA. The figure is used to illustrate a step in the overall back-translation training process of the CODEROSETTA model and to highlight the model’s ability to translate between C++ and CUDA while learning to correct its errors.

read the caption

Figure 14: Back translation intermediate results.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the CUDA code generated by CODEROSETTA, GPT4, and Gemini Ultra for a kernel function called

pow_gpu. The function calculates the power of each element in an array. The comparison highlights the differences in code style and efficiency among the various models. CODEROSETTA’s generated code is concise and directly implements the parallel computation. GPT4’s code includes additional boilerplate code for device synchronization and memory management. Gemini Ultra’s version is longer, including comments describing the function’s purpose and steps involved.read the caption

Figure 11: Power of elements CUDA kernel.

🔼 This prompt instructs a language model to translate a given C++ program into CUDA code. It emphasizes that the translated CUDA program must be functionally equivalent to the original C++ code, maintaining the same semantics. The generated CUDA code should be clean, free from unnecessary comments, and enclosed within special start and end markers (#start and #end).

read the caption

Figure 15: Prompt for translating C++ to CUDA.

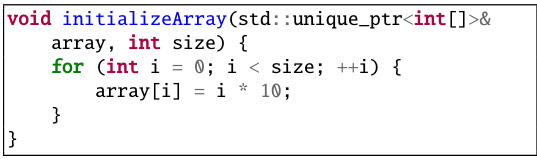

🔼 This figure shows an example of C++ code that uses

std::unique_ptrand its corresponding CUDA translation. The C++ code initializes an array usingstd::unique_ptr, while the CUDA code performs the same initialization but without using smart pointers. The figure illustrates how CODEROSETTA handles smart pointers during the translation process.read the caption

Figure 16: Example of translation of a C++ code with std::unique_ptr

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of C++ code using std::unique_ptr and its corresponding CUDA translation. The C++ code initializes an array using std::unique_ptr, a smart pointer that automatically manages memory. The CUDA translation correctly handles the initialization but omits the unique_ptr, as it is not directly supported in CUDA device code. This highlights how CODEROSETTA manages language-specific features during translation.

read the caption

Figure 16: Example of translation of a C++ code with std::unique_ptr

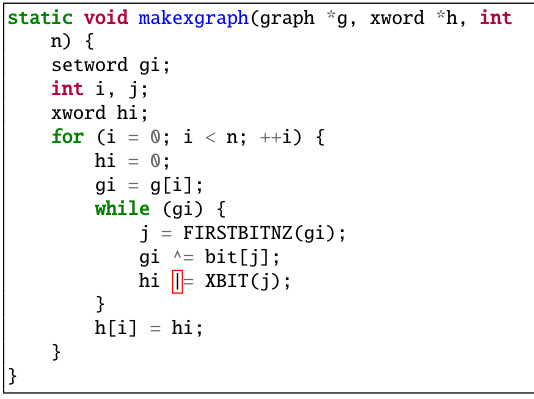

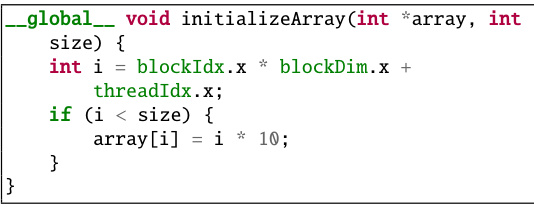

🔼 This figure shows a code example where the model failed to correctly translate C++ code to CUDA code. The C++ code snippet calculates the variable *rho, which involves accessing an array using the index i. In the translated CUDA code, the model initializes *rho to 0. This initialization may lead to a race condition if multiple threads attempt to simultaneously write to the same memory location, resulting in unpredictable behavior. The correct translation would involve using atomic operations or other synchronization mechanisms to avoid such race conditions. This demonstrates the limitations of solely relying on code metrics for evaluating code translation, highlighting the need for more comprehensive evaluation methods that consider the functional correctness of the generated code.

read the caption

Figure 17: Example of a failed C++ to CUDA translation.

🔼 This figure shows an example where the model failed to correctly translate C++ code containing the line *rho = 0; into CUDA code. The C++ code initializes the variable rho to 0. In a multi-threaded GPU environment, this can lead to race conditions if multiple threads attempt to write to the same memory location simultaneously without synchronization mechanisms. The correct approach would be to initialize rho in the host code and use atomicAdd to accumulate values in the device code safely. The figure highlights a limitation of the model where it fails to handle synchronization correctly in a multithreaded CUDA environment.

read the caption

Figure 17: Example of a failed C++ to CUDA translation.

More on tables

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the impact of each training objective (Masked Language Modeling, Abstract Syntax Tree Entity Recognition, Denoising Autoencoding with adaptive noise injection, and back translation) on the code translation results for C++ to CUDA. It shows the BLEU and CodeBLEU scores for each experiment where one of these training components was removed. The baseline results are also provided for comparison.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation Study for C++ to CUDA.

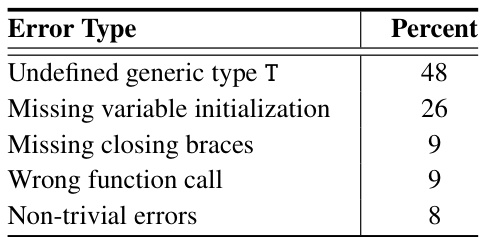

🔼 This table shows the frequency of different types of compilation errors encountered in the 28 out of 180 code samples that failed to compile after translation. The most frequent errors were undefined generic types (48%), missing variable initialization (26%), and missing closing braces (9%). Other less frequent errors include wrong function calls and non-trivial errors.

read the caption

Table 2: Types of compilation errors (28 codes with compilation error out of a total 180 codes).

🔼 This table presents the CodeBLEU scores achieved by various models on the Fortran to C++ translation task. The models compared include several large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4, Gemini-Ultra, and Gemini-Pro, as well as open-source models such as DeepSeekCoder and StarCoder. A fine-tuned version of StarCoder is also included. The results highlight the performance of CODEROSETTA, which significantly outperforms the other models on this challenging translation task.

read the caption

Table 4: Fortran to C++ translation results.

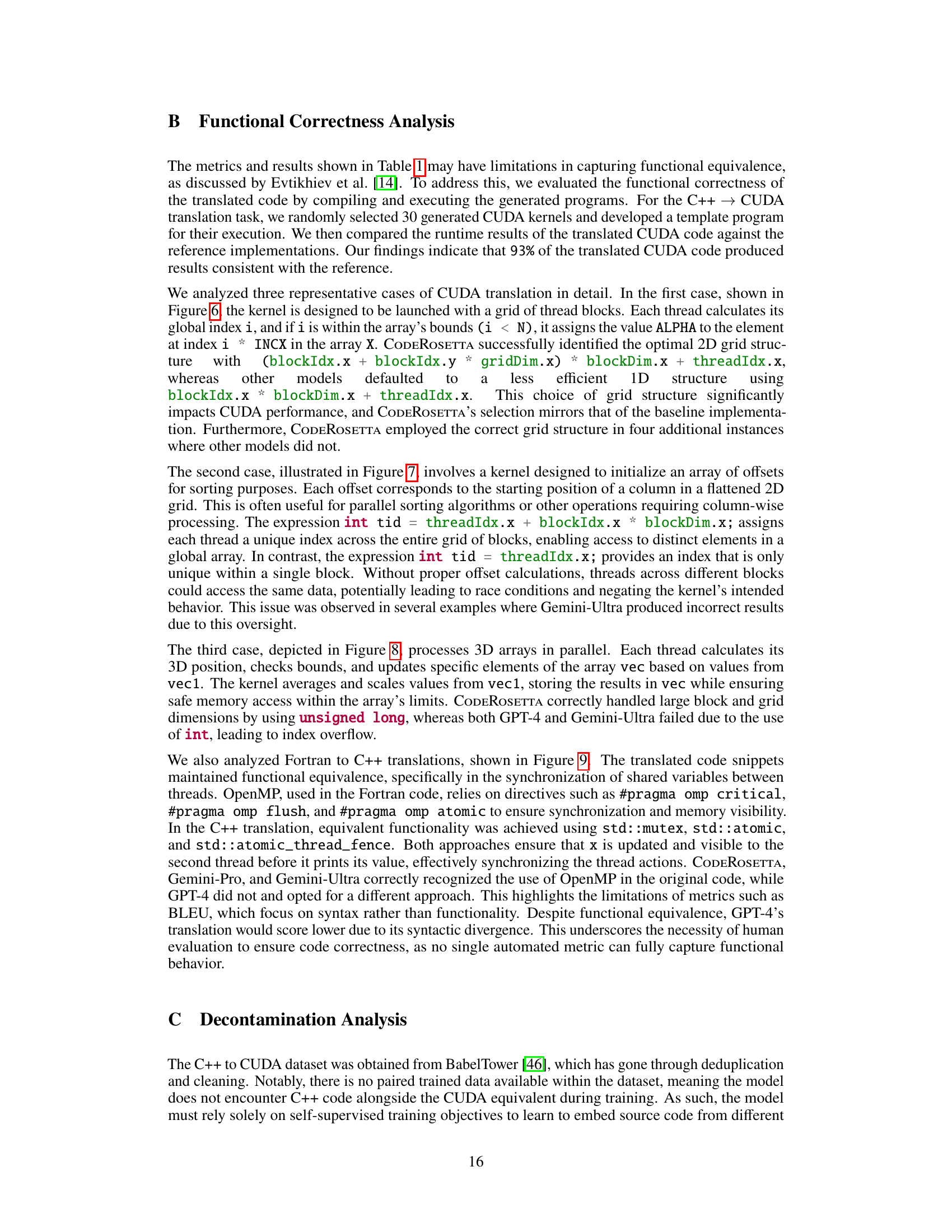

🔼 This table presents the results of translating CUDA code back to C++ using different models, including GPT4, Gemini-Pro, and the proposed CODEROSETTA model. The models were evaluated using the BLEU and CodeBLEU metrics. The prompt used for evaluation was similar to that in Figure 15 but with slight modifications.

read the caption

Table 5: CUDA to C++ translation results across different models. We use a similar prompt as the one in Figure 15 with small adjustments.

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the C++ to CUDA translation task, comparing CODEROSETTA against several state-of-the-art baselines and large language models. Metrics include BLEU, CodeBLEU, ChrF, and ROUGE-L, reflecting different aspects of code translation quality. Compilation accuracy is also provided as a measure of the practical utility of the generated code. The table highlights CODEROSETTA’s superior performance, particularly when compared to closed-source LLMs.

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of C++ to CUDA translation results across various code metrics and compilation accuracy. Second-best results are underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different models’ performance on the task of translating C++ code to CUDA code. The models are evaluated using several metrics, including BLEU, CodeBLEU, ChrF, and ROGUE-L, which measure different aspects of translation quality. Compilation accuracy is also reported, indicating the percentage of successfully compiled translations. The table highlights CODEROSETTA’s superior performance compared to other models, especially in terms of BLEU and CodeBLEU scores and compilation accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of C++ to CUDA translation results across various code metrics and compilation accuracy. Second-best results are underlined.

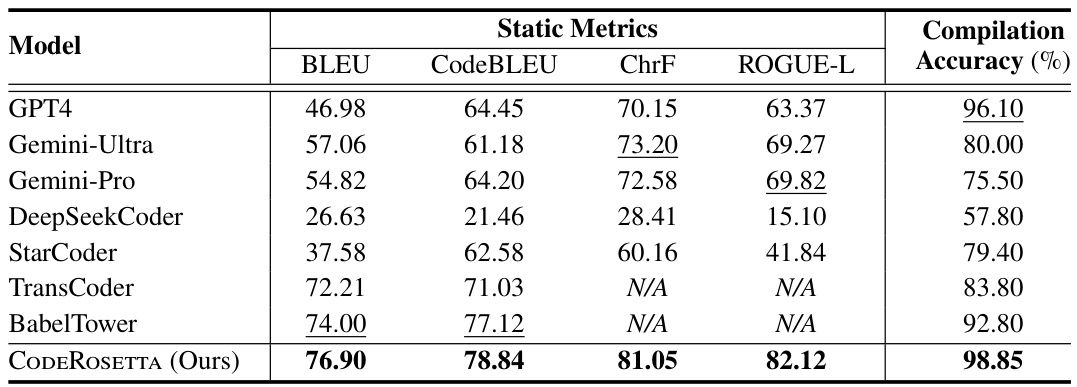

🔼 This table presents the sizes of the training, validation, and test datasets used in the experiments. The datasets are categorized by programming language pair (C++ ↔ CUDA and C++ ↔ Fortran). Note that the C++ ↔ CUDA dataset includes both unpaired and paired data, while the C++ ↔ Fortran dataset includes unpaired and paired data. The sizes are provided in terms of the number of files and their total size in MB or KB.

read the caption

Table 8: Dataset statistics for C++, CUDA, and Fortran programming languages.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study that shows the impact of varying beam sizes on the performance of the CODEROSETTA model for C++ to CUDA code translation. The metrics used to evaluate the model’s performance are BLEU and CodeBLEU. The table shows that a beam size of 5 yields the best results in terms of both BLEU and CodeBLEU scores. Larger beam sizes do not significantly improve the results, indicating that a beam size of 5 provides a good balance between exploration and exploitation.

read the caption

Table 9: Effect of different beam sizes on C++ to CUDA translation.

🔼 This table presents the CodeBLEU scores achieved by different large language models (LLMs) on the task of translating C++ code to Fortran code. The models compared include GPT4, Gemini-Ultra, Gemini-Pro, and the authors’ proposed model, CODEROSETTA. The results highlight CODEROSETTA’s superior performance in this complex translation task.

read the caption

Table 10: C++ to Fortran translation results in terms of CodeBLEU.

Full paper#