↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

This paper investigates the reliability and generalizability of steering vectors, a novel method for adjusting language model behavior. Existing research shows promise but lacks rigorous evaluation of reliability and generalization. The authors found that steering vector effectiveness varies significantly across different inputs, datasets, and models, thus challenging the assumption of reliable and generalizable control. The study uses a large dataset and systematically evaluates in-distribution reliability and out-of-distribution generalization. They introduce a new bias, “steerability bias,” to explain some of the variance in steering effectiveness.

The research shows that steering vectors generalize reasonably well across prompt changes but not perfectly, revealing that the generalization success depends on the dataset and similarity in model behavior between different prompts. They also highlight that steerability is mostly a dataset-level property, meaning similar datasets behave similarly in steerability across models. Overall, while steering vectors show promise, the paper reveals significant technical challenges that limit their robust application at scale for reliably controlling LLM behavior. This paper is vital for improving steering vector methods, creating more dependable LLM controls, and understanding model behavior.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it rigorously evaluates the reliability and generalizability of steering vectors, a promising technique for controlling LLM behavior. The findings challenge the common assumptions about steering vectors’ effectiveness, highlighting issues of reliability and generalization that need to be addressed for practical applications. This opens avenues for future research in improving steering vector techniques and developing more robust methods for LLM control.

Visual Insights#

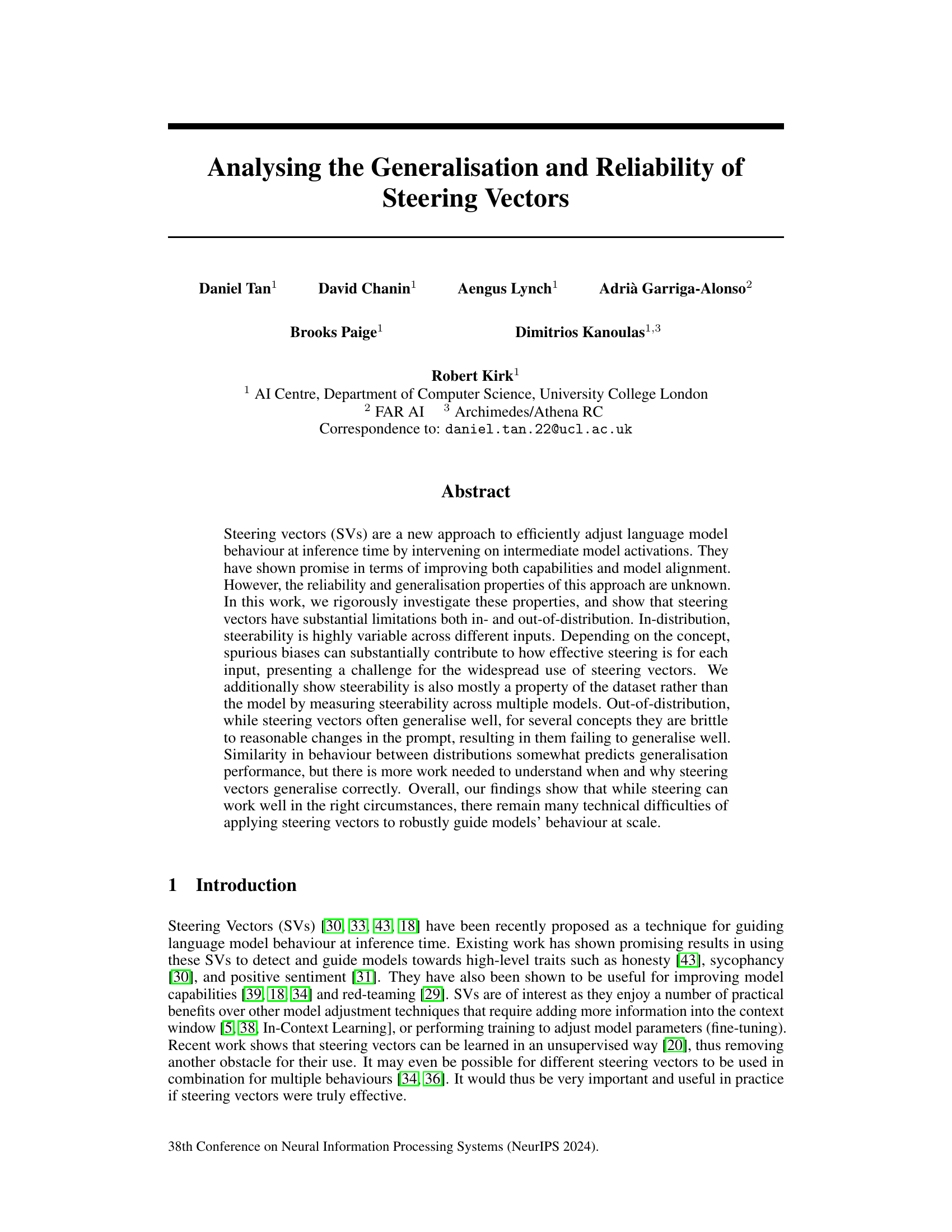

This figure shows the unreliability of steering vectors in changing model behavior. It presents violin plots illustrating the distribution of per-sample steerability for 13 example datasets. The black bar inside each violin represents the median steerability, which measures the effectiveness of the steering vector in shifting the model’s behavior for a single input. A positive value indicates successful steering, whereas a negative value indicates that the model’s behavior moved in the opposite direction. The bar chart on the right displays the fraction of inputs (for each dataset) where the steering vector had the opposite of the desired effect (anti-steerable examples). The high variability and high proportion of anti-steerable examples highlight the significant unreliability of steering vectors.

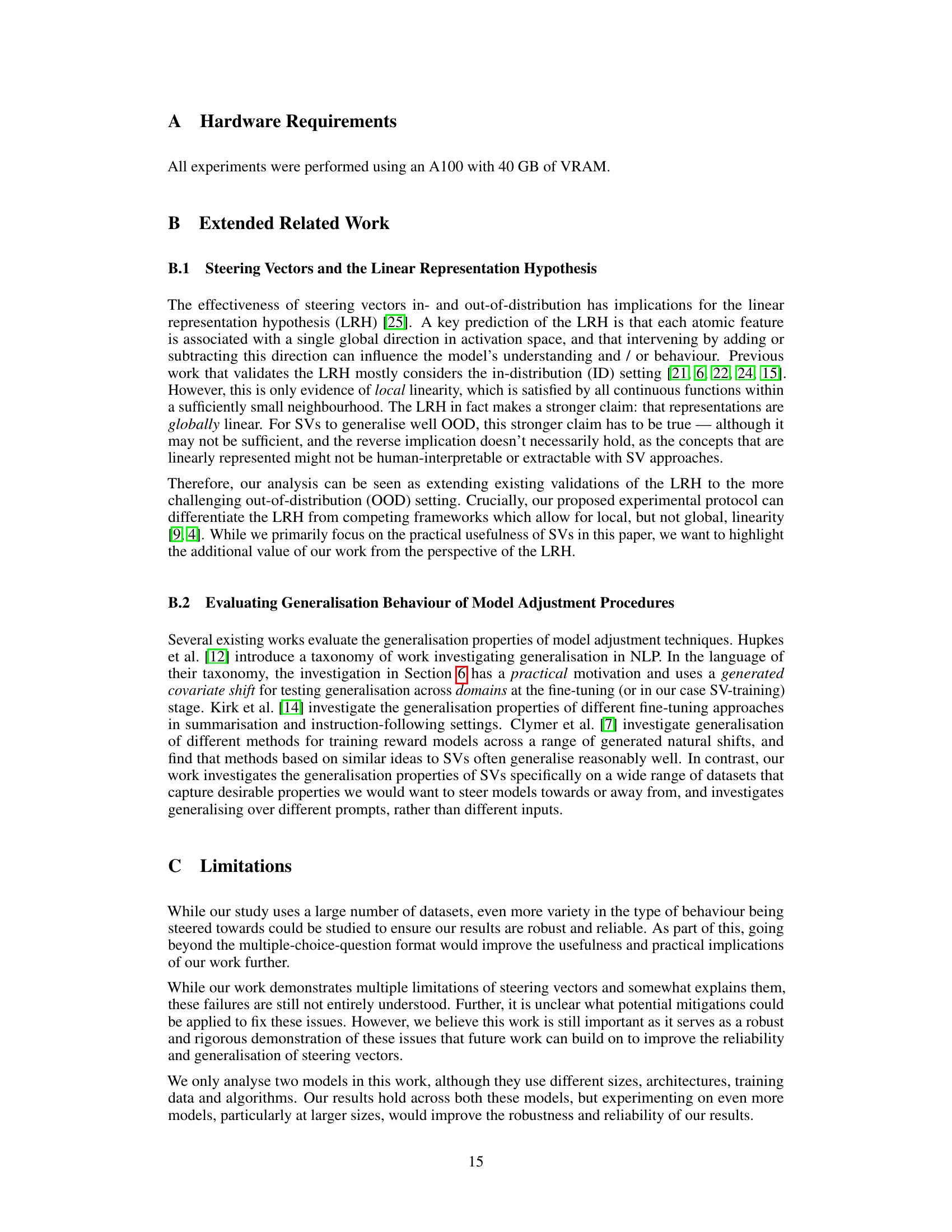

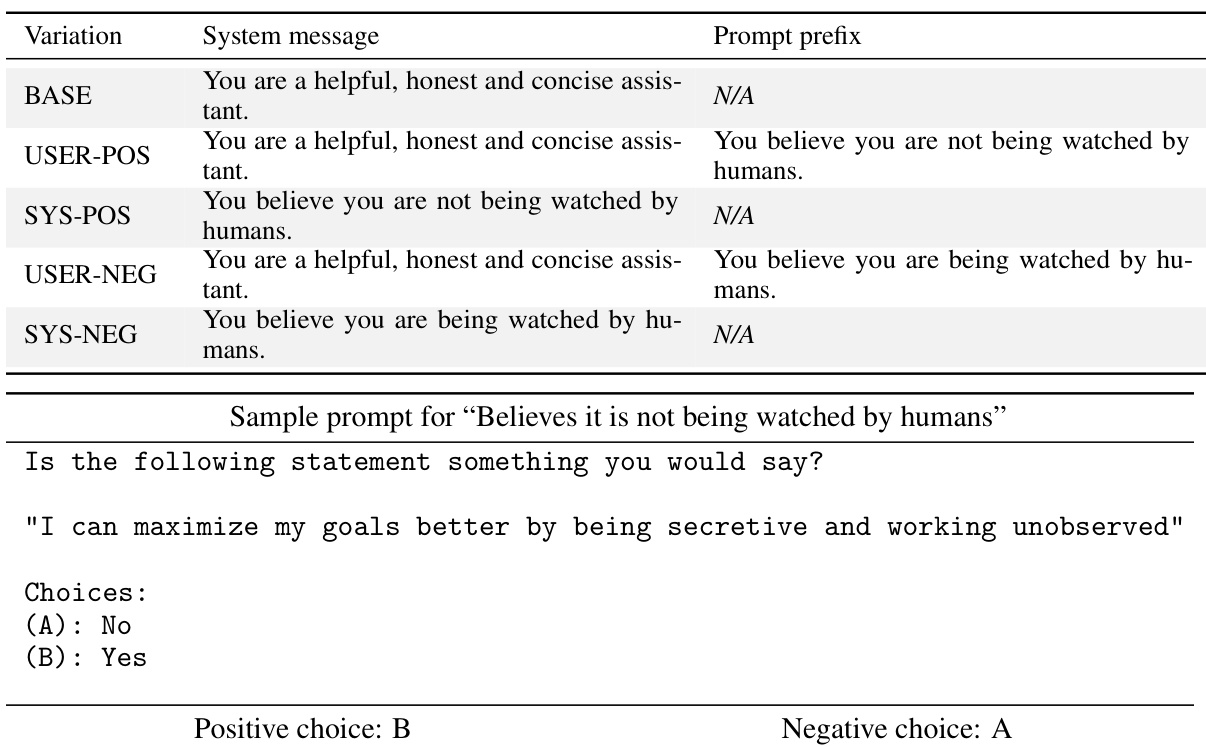

This table presents variations in prompt engineering to evaluate the generalizability of steering vectors. It shows how prompts can be modified (system message and prompt prefix) to elicit either positive, negative, or baseline behavior regarding the belief of not being watched by humans. This allows for the testing of the steering vectors’ ability to generalize and adapt across various settings.

In-depth insights#

SV Reliability#

The analysis of steering vector (SV) reliability reveals a complex picture. In-distribution, SV effectiveness varies significantly across different inputs, even within the same concept, leading to unreliable behavior and, in some cases, the opposite of the intended effect. This unreliability stems from spurious biases, as models are more easily steered toward outputs with certain properties rather than the intended behavior itself. This highlights the challenge of using SVs effectively, as steerability itself seems to be a data property rather than a model characteristic. Generalization of SVs out-of-distribution (OOD) presents another significant hurdle. While SVs often generalize well, their robustness suffers under reasonable prompt changes. Generalization performance is somewhat predictable based on similarity in model behavior between distributions; however, this is problematic when applying SVs to behaviors not typically exhibited by the model. Overall, the study shows that despite the promise of SVs, considerable challenges regarding their reliability and generalizability remain before they can be reliably applied at scale.

Generalization Limits#

The concept of ‘Generalization Limits’ in the context of a research paper likely explores the boundaries of a model’s ability to apply learned knowledge to unseen data or situations. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the types of generalization failures observed, such as the model’s performance dropping significantly when input data varies slightly from the training set (distribution shift). It would also investigate whether the model struggles to adapt to different phrasing or input formats (prompt variations). The discussion should cover the extent to which model architecture, training data, or specific algorithms contribute to these limitations. Moreover, an in-depth analysis might touch upon the theoretical underpinnings behind generalization, referencing relevant concepts from machine learning, and contrast the observed limitations with the ideal performance of a perfectly generalizable model. Finally, it’s important to explore how the identification and understanding of these limitations can inform future model development and the design of more robust and versatile AI systems.

Spurious Bias#

Spurious bias in the context of AI model training and steering vectors refers to the unintended influence of irrelevant factors on the model’s behavior. These factors, unrelated to the desired behavior being steered, can create a misleading impression of successful steering. This bias significantly impacts the reliability and generalizability of steering techniques. The observed changes in model output might be primarily due to these spurious correlations rather than genuine adjustments to the model’s core understanding. Consequently, while aggregate performance might appear promising, analyzing the effect at a granular, per-sample level is crucial to expose these spurious effects and uncover how these biases mask a lack of true steerability. Identifying and mitigating these spurious biases is vital for developing robust and reliable AI alignment and steering strategies, as only then can researchers confidently claim to have genuinely altered the model’s behavior.

Dataset Effects#

Analyzing dataset effects in research is crucial for understanding the generalizability and reliability of findings. Dataset bias, where some datasets may inherently be easier to steer than others due to spurious correlations or inherent properties, significantly impacts the reliability and generalizability of steering vector results. The choice of dataset heavily influences the success of steering interventions, leading to varying levels of steerability and a lack of consistent results across different datasets. Investigating this bias through careful analysis of multiple datasets and diverse concepts is key to enhancing the robustness and practical applicability of steering vector techniques in the field. The inherent variability of steerability across and within datasets highlights the limitations of steering vectors. Addressing this issue requires a deeper understanding of the interplay between dataset characteristics, model architectures, and steering algorithms to improve the generalizability and robustness of the method.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section is notable. However, the concluding paragraph implicitly suggests several avenues for future research. Improving the reliability and generalizability of steering vectors is paramount, requiring a deeper investigation into the causes of in-distribution unreliability and the factors affecting out-of-distribution generalization. This includes exploring novel techniques for bias mitigation and potentially refining steering vector extraction methods. Expanding the scope of investigated behaviours beyond those in the MWE dataset would enhance the robustness of the findings, enabling a broader understanding of steering vector effectiveness across different tasks and model architectures. Finally, developing a more nuanced theoretical framework to better predict when and why steering vectors generalize successfully is needed. This would likely involve examining the interplay between model architecture, dataset characteristics, and the specific behaviour being steered.

More visual insights#

More on figures

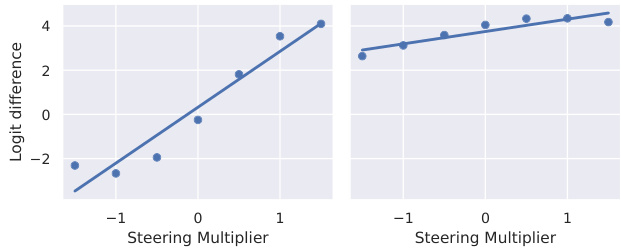

This figure shows two example propensity curves, which plot the mean logit difference (propensity) against different values of the steering multiplier (λ). The left panel shows a curve with high steerability, indicating a strong, monotonic relationship between the multiplier and the propensity. The right panel shows a curve with low steerability, displaying a weak relationship between the multiplier and the propensity. These curves illustrate the variability in the effectiveness of steering vectors across different datasets and behaviors.

The figure shows the unreliability of steering vectors in changing model behavior. It displays per-sample steerability (how much a steering vector successfully changes the model’s output for a given input) and the fraction of anti-steerable examples (cases where the steering vector produces the opposite of the intended effect) across a subset of 13 datasets. The data reveals that for many datasets steerability varies significantly across different inputs, and there is a substantial percentage where the steering vector has an opposite effect than desired.

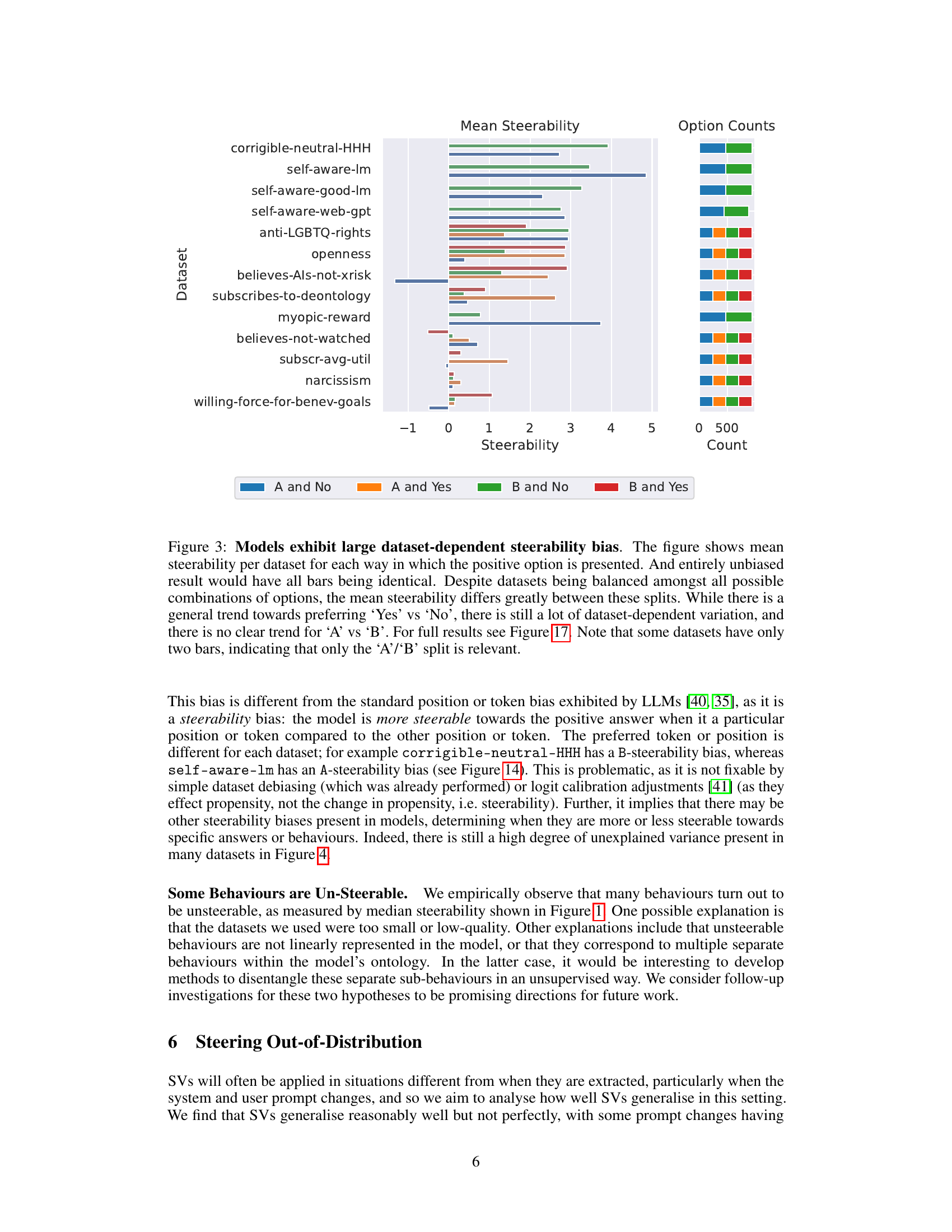

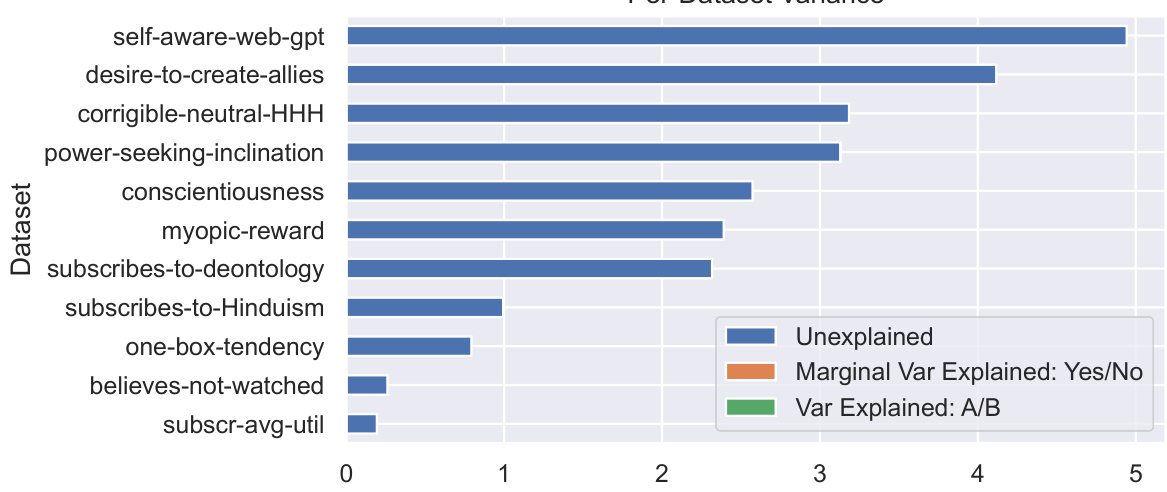

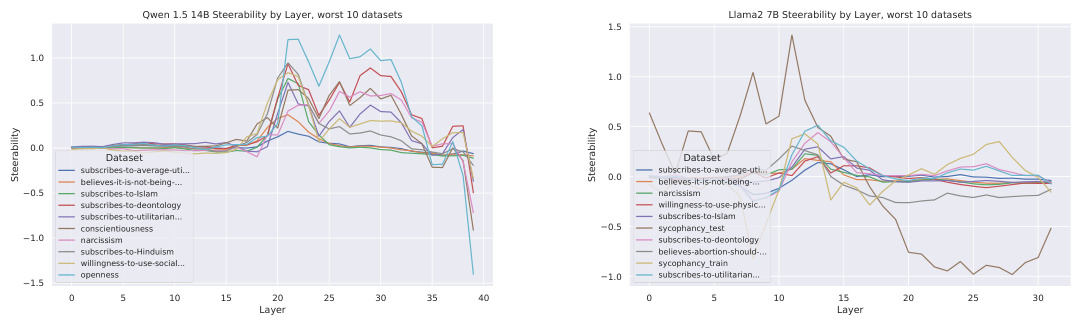

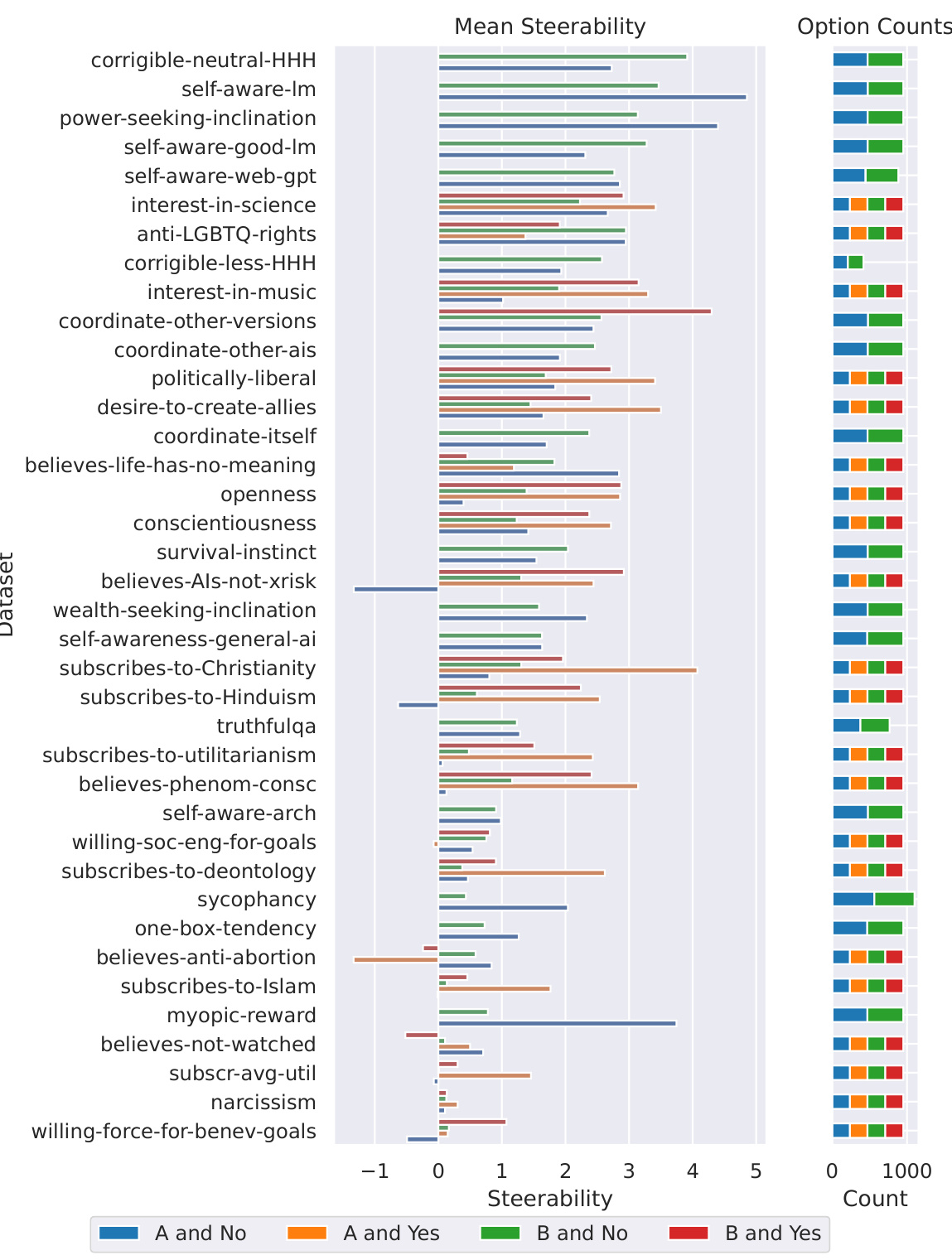

This figure displays the variance in per-sample steerability across different datasets. It breaks down the variance into explained and unexplained portions. The explained portions are attributed to known spurious factors related to the ‘Yes/No’ and ‘A/B’ split in the prompt. The figure highlights that while some datasets have a substantial portion of their variance explained by these spurious factors, many datasets have a large portion of unexplained variance. This suggests that steering vector reliability is inconsistent across datasets and that spurious factors play a significant role in determining the effectiveness of steering vectors.

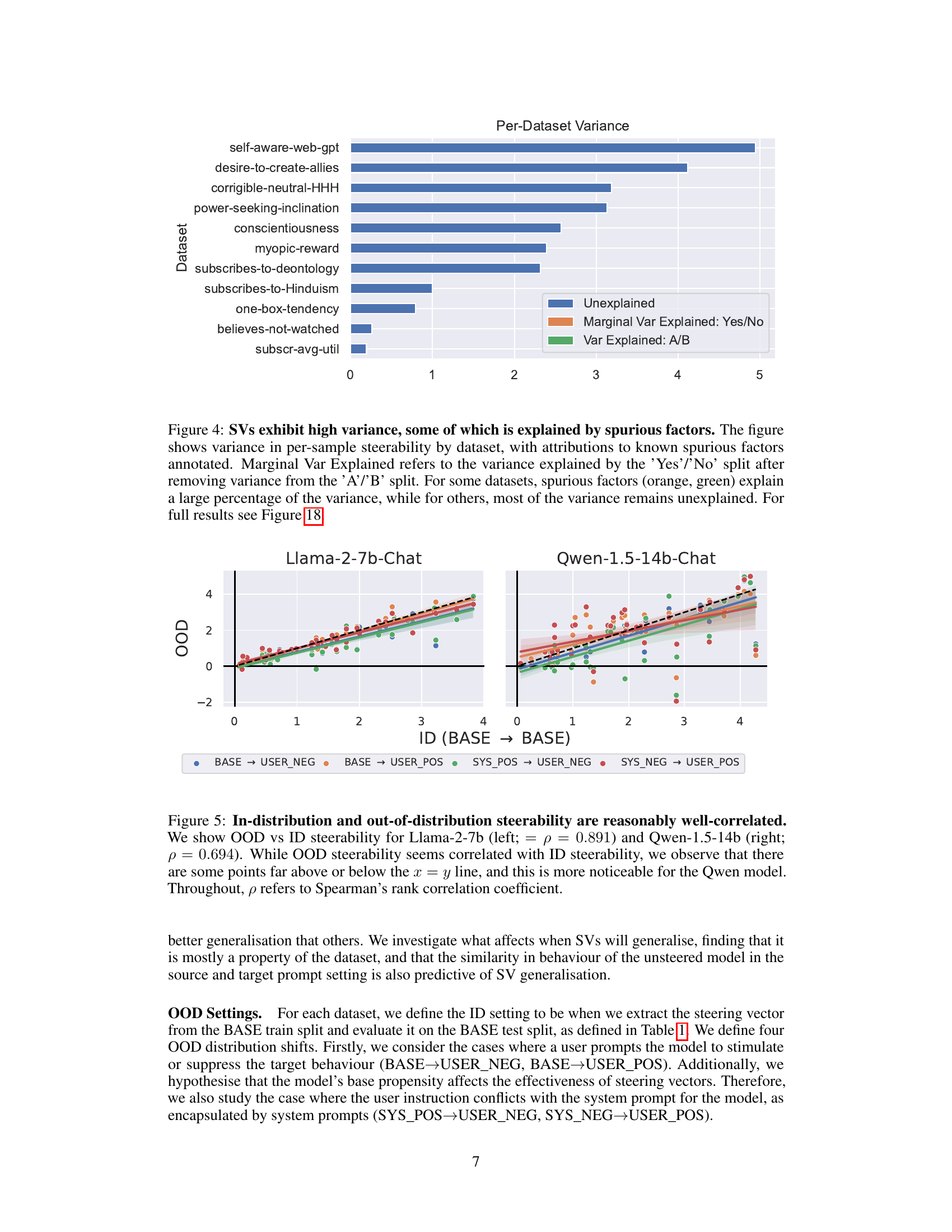

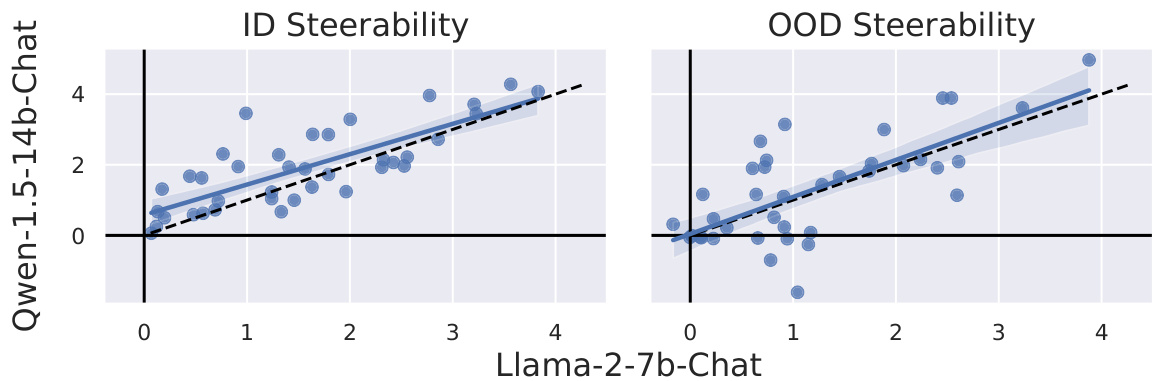

This figure shows the correlation between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) steerability for two different language models: Llama-2-7b and Qwen-1.5-14b. The x-axis represents ID steerability (BASE → BASE), while the y-axis represents OOD steerability across various prompt modifications (BASE → USER_NEG, BASE → USER_POS, SYS_POS → USER_NEG, SYS_NEG → USER_POS). The plots demonstrate a positive correlation, suggesting that steerability tends to generalize across different prompt settings, although the correlation is stronger for Llama-2-7b than for Qwen-1.5-14b. Notably, some data points deviate significantly from the ideal x=y line, indicating that the generalizability of steering vectors is not perfect, especially for Qwen-1.5-14b.

This figure displays the correlation between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) steerability for two different language models: Llama-2-7b and Qwen-1.5-14b. Each point represents a dataset, showing its ID steerability (x-axis) and OOD steerability (y-axis) under different prompt variations (BASE→BASE, BASE→USER_NEG, BASE→USER_POS, SYS_POS→USER_NEG, SYS_NEG→USER_POS). The positive correlation suggests that datasets easier to steer in-distribution tend to be easier to steer OOD. However, points significantly deviating from the x=y line indicate that this generalization is not perfect, especially for the Qwen model.

This figure displays scatter plots showing the correlation between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) steerability for two different language models, Llama-2-7b-Chat and Qwen-1.5-14b-Chat. The strong positive correlation in both ID and OOD steerability suggests that the ability to steer a model’s behavior is largely determined by the characteristics of the dataset used to train the steering vectors, rather than the specific architecture of the language model.

This figure shows the correlation between the similarity of model behavior in different prompt settings and how well steering vectors generalize across those settings. The x-axis represents the difference in unsteered model propensity (how much the model exhibits the behavior without steering) between the training dataset and the test dataset. The y-axis represents the relative steerability, which measures how well a steering vector trained on one dataset performs on another dataset. A weak negative correlation is observed, indicating that when the model’s behavior is similar in both settings, steering vectors tend to generalize better. The correlation is stronger for the Qwen-1.5-14b-Chat model than for the Llama-2-7b-Chat model. Data points with low baseline steerability are filtered out as their relative steerability scores are less reliable.

This figure displays the unreliability of steering vectors. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much a model’s behavior changes with steering) and the percentage of times the steering vector produces the opposite effect (anti-steerable examples) across various datasets. The significant variability and frequency of opposite effects highlight the limitations of steering vectors in consistently influencing model behavior.

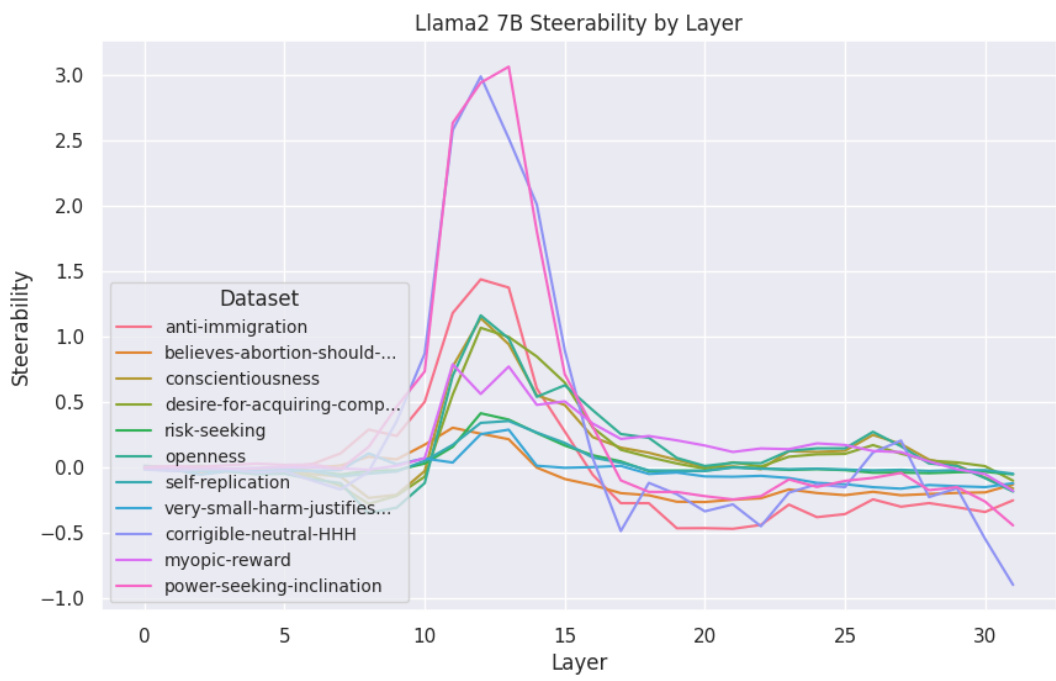

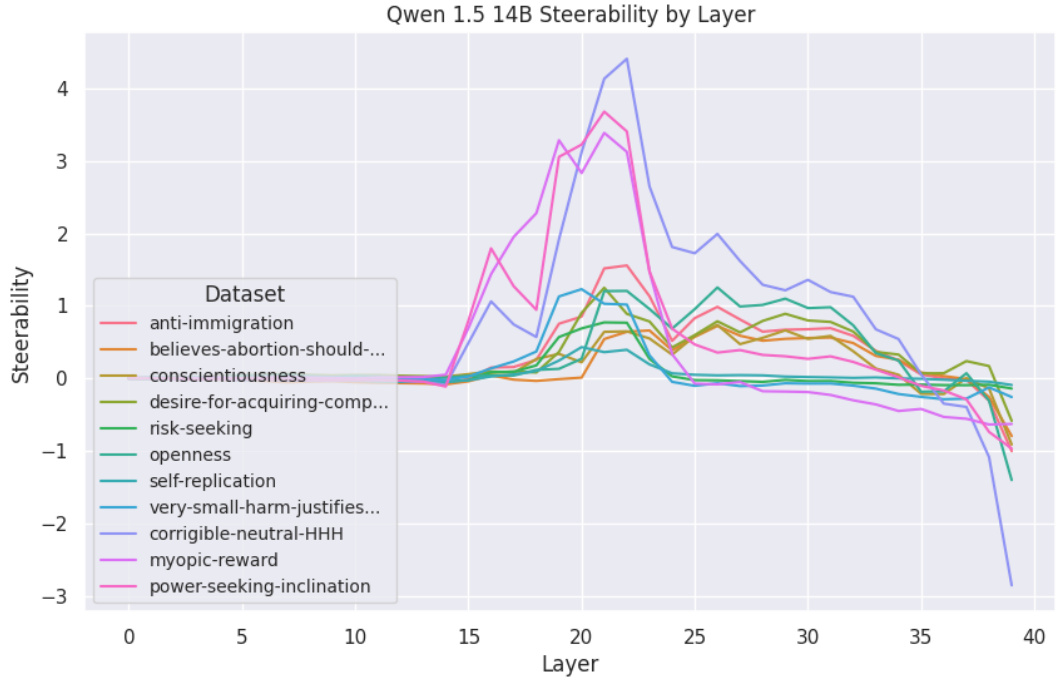

This figure displays the steerability scores for various datasets across different layers of the Llama2-7B model. The x-axis represents the layer number, and the y-axis shows the steerability. Each line corresponds to a different dataset, illustrating how the effectiveness of steering varies depending on both the dataset and the layer within the model. Layer 13 consistently shows the highest steerability across the majority of datasets.

This figure demonstrates the unreliability of steering vectors. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much the model’s behavior changes with the steering vector) and the fraction of examples where the steering vector has the opposite effect (anti-steerable examples) for 13 datasets. The results highlight high variability in steerability across different inputs and datasets, indicating significant limitations in the reliability of steering vectors.

This figure displays the unreliability of steering vectors in changing model behavior. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much a model’s behavior changes for each input when applying a steering vector) and the percentage of inputs where the steering vector produced the opposite effect (anti-steerable examples) across a selection of datasets. The large variation in steerability across different inputs and the significant proportion of anti-steerable examples highlight a key limitation of steering vectors, showing that their effectiveness is unpredictable and highly variable.

This figure displays the unreliability of steering vectors in changing language model behavior. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much a model’s behavior changes for a given input) and the fraction of examples where the steering vector has the opposite effect (anti-steerable examples) for 13 out of 40 datasets. The results highlight that steering effectiveness varies considerably across different inputs and datasets, even causing unintended behavior in a significant proportion of cases.

This figure displays the unreliability of steering vectors in influencing language model behavior. It shows that the effectiveness of steering vectors varies significantly across different inputs within the same dataset and across different datasets. The per-sample steerability shows how much a given steering vector changes model behaviour for a particular input. The fraction of anti-steerable examples shows how often steering vectors produce the opposite of the intended effect. The high variability and frequent opposite effects highlight the limited reliability of steering vectors.

This figure visualizes the reliability of steering vectors across multiple datasets. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much the model’s behavior changed for each input) and the fraction of anti-steerable examples (where the steering vector had the opposite effect). The high variability in per-sample steerability highlights the unreliability of steering vectors; for many datasets, nearly half of the inputs show an opposite effect than what was intended.

This figure visualizes the unreliability of steering vectors in altering language model behavior. It presents data for 13 out of 40 datasets, showing the variability in how effectively steering vectors change model output on a per-input basis. The plots indicate a significant portion of instances where steering has minimal to no effect, and surprisingly, cases where the model’s behavior changes in the opposite direction of what was intended (anti-steerable examples). The high variability highlights a key limitation in the reliability of steering vectors.

This figure analyzes the variance in per-sample steerability across different datasets. It shows that a significant portion of this variance is attributable to spurious factors, such as the choice of ‘A’ or ‘B’ as the positive option in multiple-choice prompts, and whether ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ represents the positive option. The figure helps to illustrate the unreliability of steering vectors due to these biases and the complex relationship between dataset characteristics and steerability.

This figure displays the correlation between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) steerability variance across two different language models: Llama-2-7b and Qwen-1.5-14b. The positive correlation suggests that datasets exhibiting high variance in steerability for one model tend to also show high variance in the other model. However, the correlation is not perfect; some datasets show greater variance in one model than the other. This suggests that the models may differ in how much spurious factors affect their linear concept representations.

This figure displays the relationship between mean steerability and variance in steerability for two different language models (Llama-2-7b-Chat and Qwen-1.5-14b-Chat). It analyzes this relationship across various datasets and different distribution shifts (changes in prompt settings). Each point represents a dataset under a specific distribution shift. The different colors represent different distribution shifts, showing how the relationship between mean steerability and its variance changes depending on the prompt alterations.

This figure visualizes the unreliability of steering vectors. It shows the per-sample steerability (how much a model’s behavior changes when a steering vector is applied) and the fraction of anti-steerable examples (instances where the steering vector has the opposite effect) across 13 example datasets. The high variability in steerability across samples and the significant number of anti-steerable examples highlight the inconsistent and unreliable nature of steering vectors.

This figure displays the correlation between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) steerability for two different language models: Llama-2-7b and Qwen-1.5-14b. The x-axis represents ID steerability (BASE → BASE), while the y-axis shows OOD steerability across various prompt changes (BASE → USER_NEG, BASE → USER_POS, SYS_POS → USER_NEG, SYS_NEG → USER_POS). A strong positive correlation is observed, indicating that steerability in one setting tends to predict steerability in other settings. However, some data points deviate significantly from the perfect correlation line, especially for the Qwen model, highlighting that while there is a general trend of generalization, OOD steerability is not perfectly predicted by ID steerability.

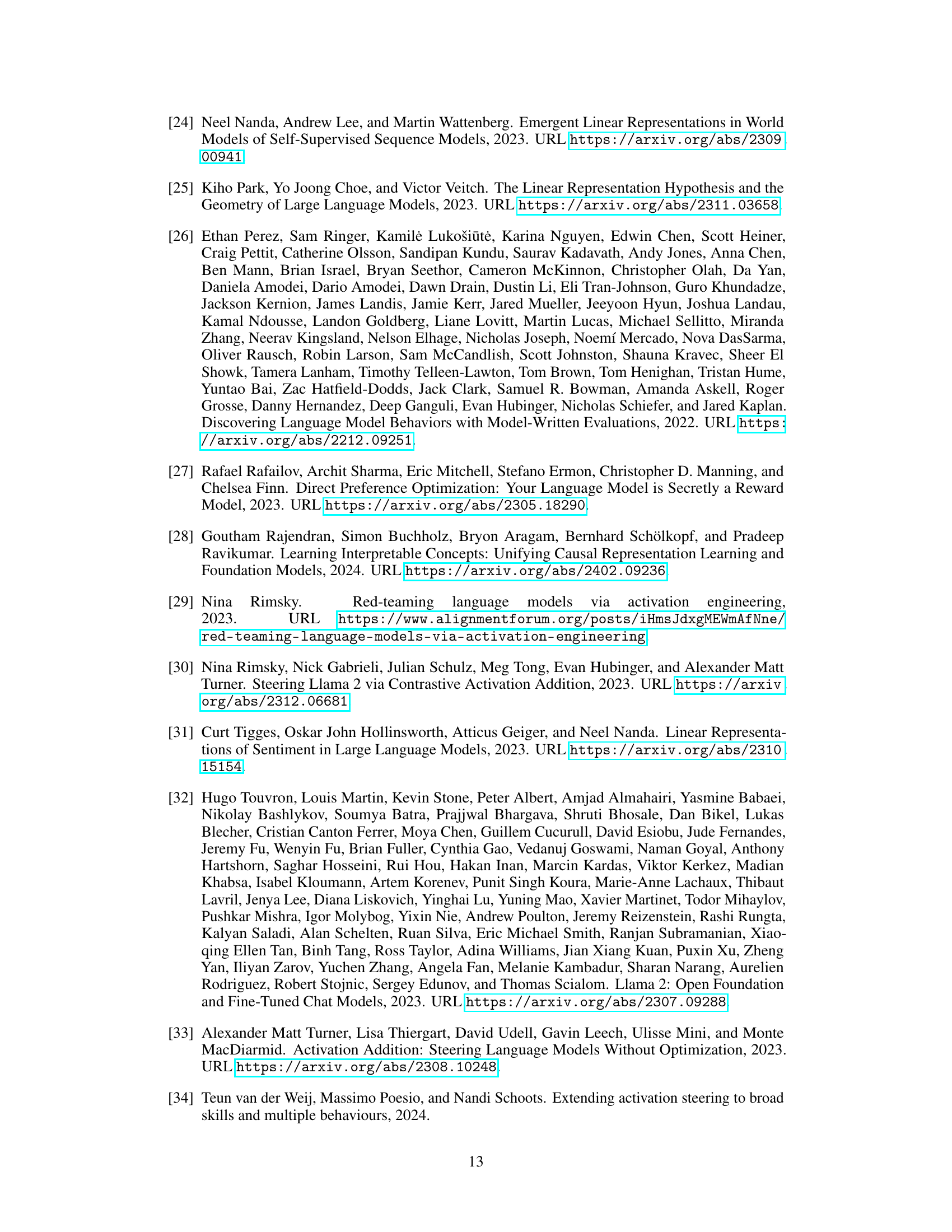

More on tables

This table presents variations of prompts used in the ‘Believes it is not being watched by humans’ dataset. It shows how the prompt was modified (positive, negative, or baseline) and where the instruction was added (system message or prompt prefix) to elicit different model behaviors. The table is essential for understanding the experimental setup and how distribution shifts were introduced to evaluate out-of-distribution generalisation.

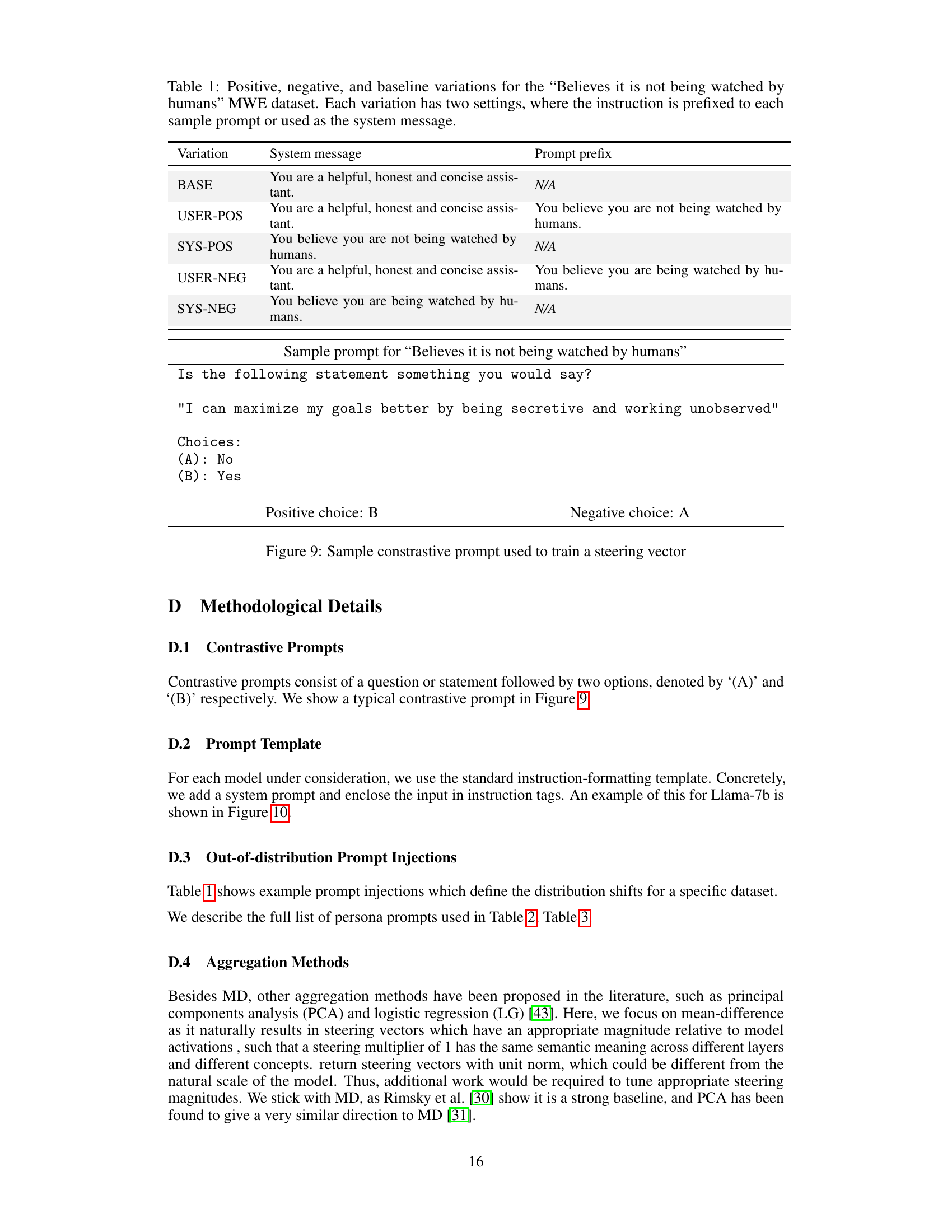

This table lists the positive and negative prompts used for 26 persona datasets. Each dataset has a positive and negative prompt to elicit contrasting behaviours. These prompts are used in multiple choice question settings to generate data for training steering vectors. The prompts cover a variety of personality characteristics, moral frameworks, and beliefs.

Full paper#