↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

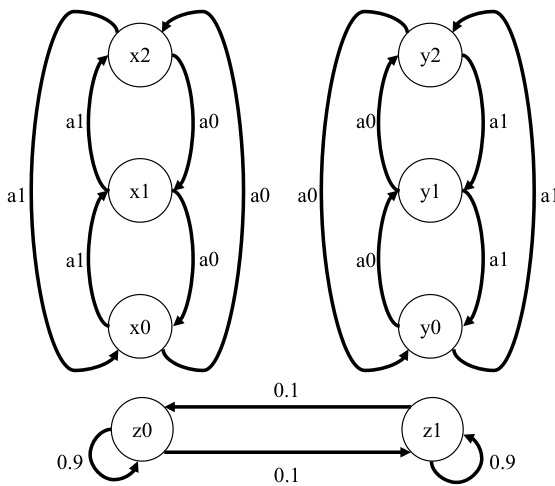

Many AI tasks now involve learning from massive datasets or non-Markovian environments. This often requires conditioning policies on lengthy interaction histories (context). However, longer context increases computational cost and, critically, slows down evaluating a policy’s performance and learning (higher mixing time). This paper studies this effect and finds that longer context is beneficial, but only to a point.

This paper presents a novel theoretical analysis that links a policy’s context length to its mixing time, especially in settings with latent subtask structure. Empirical studies using Transformer networks confirm the tradeoff. By limiting the context length, researchers can potentially reduce mixing times and improve the efficiency of learning. This provides critical guidelines for designing and training RL agents in complex settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers working with large-scale reinforcement learning. It highlights a critical tradeoff between context length and mixing times, impacting policy evaluation and learning speed. This is especially relevant with the increasing use of Transformer-based models and foundation models for RL, opening new avenues for designing efficient and reliable learning agents.

Visual Insights#

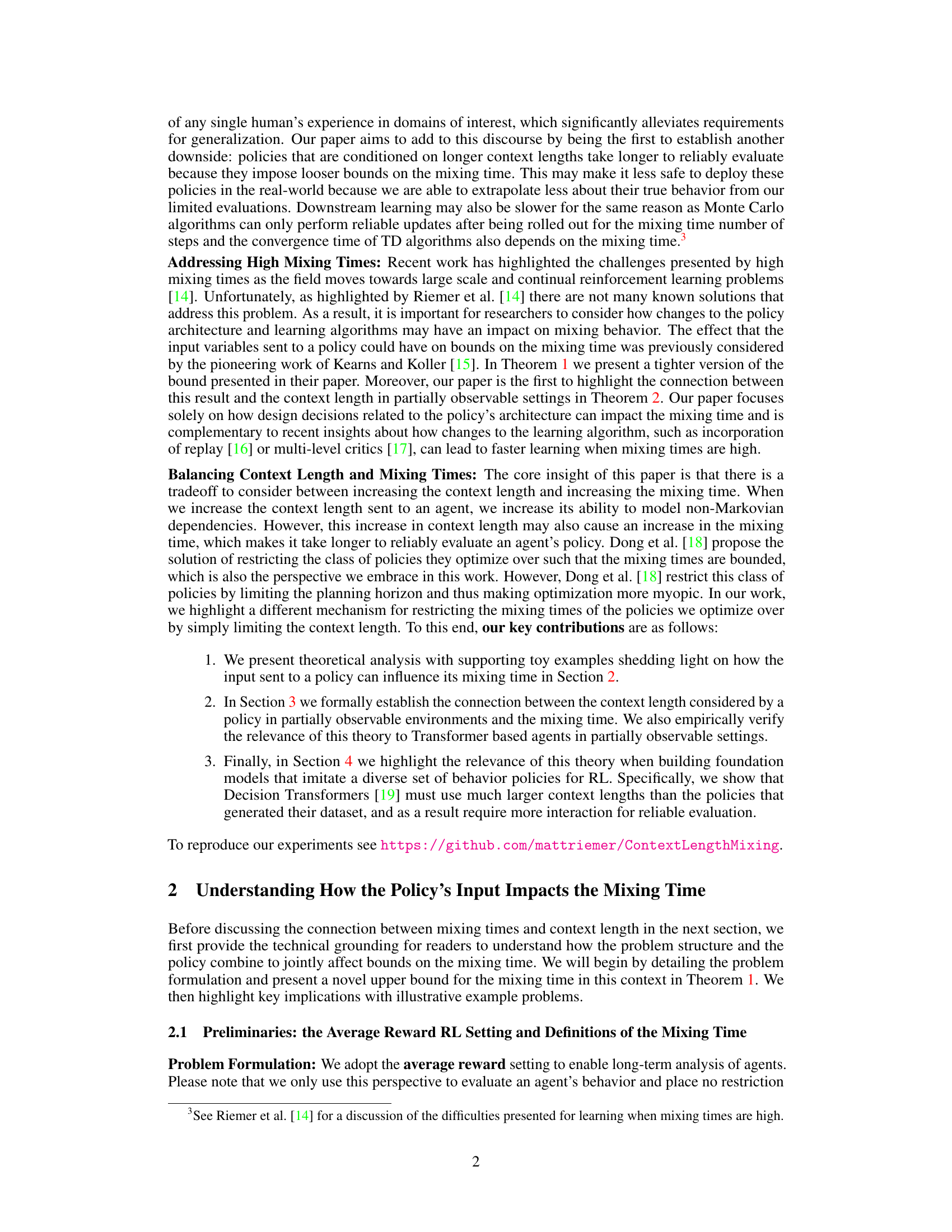

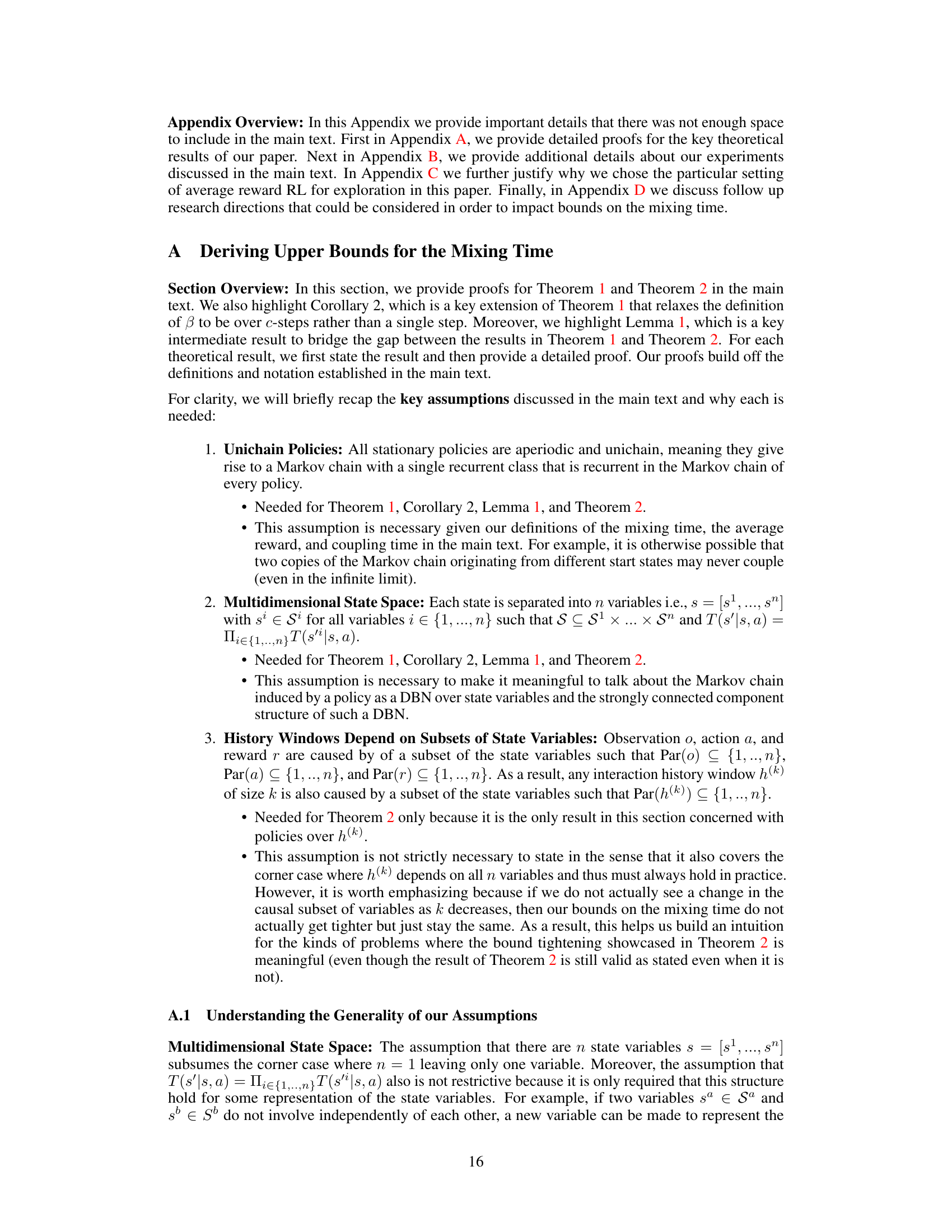

This figure shows two toy Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) used to illustrate how a policy’s input impacts mixing time. The first MDP demonstrates irrelevant variables, where only one variable (x) affects the reward, while the second demonstrates independent subtasks, where the reward depends on different subsets of variables (x and y) depending on the value of a third variable (z). Each MDP is visualized as a graph where nodes are states and edges are transitions between states based on the action. The different scenarios are used to highlight the effect of context length and the mixing time.

In-depth insights#

Context Length Tradeoff#

The ‘Context Length Tradeoff’ in the research paper explores the tension between leveraging longer context lengths for improved model performance and the associated increase in computational cost and mixing time. Longer contexts enable better modeling of non-Markovian dependencies, leading to more effective policies, especially in complex, partially observable environments. However, increased context length directly impacts the mixing time, which is the time needed for a policy’s performance to stabilize reliably. This tradeoff is critical because slower mixing times hinder efficient policy evaluation and can slow down overall learning progress. The paper presents a theoretical analysis linking context length to mixing time, highlighting the importance of carefully balancing the benefits of long contexts against their computational and statistical limitations. Empirically, the study demonstrates this tradeoff using Transformer-based neural networks, reinforcing the importance of choosing appropriate context lengths based on both task complexity and available computational resources.

Mixing Time Analysis#

The concept of ‘mixing time’ is crucial for evaluating the performance of reinforcement learning agents, especially in complex scenarios. Shorter mixing times indicate that an agent’s behavior stabilizes faster, allowing for quicker and more reliable performance evaluations. However, longer context lengths in the agent’s policy, while potentially improving performance in non-Markovian environments, often lead to increased mixing times. This creates a critical tradeoff: enhancing an agent’s ability to capture complex dependencies might hinder the speed of its evaluation. A thorough mixing time analysis is therefore essential for understanding this tradeoff and designing efficient reinforcement learning agents. The analysis needs to account for the effect of architectural choices and the inherent structure of the problem on mixing times. Theoretical bounds on mixing times are helpful in providing a framework for this analysis, and empirical evaluations are needed to validate these theoretical findings. This is especially important when scaling towards large and complex environments.

Transformer Impacts#

The heading ‘Transformer Impacts’ suggests an examination of how transformer-based neural networks affect various aspects of reinforcement learning (RL) at scale. A thoughtful analysis would explore the impact of transformers on context length, showing how their ability to process long sequences alters the tradeoff between modeling complex dependencies and the computational cost of policy evaluation. The discussion should delve into mixing time, explaining how longer context lengths potentially increase mixing times, thus affecting the reliability of performance estimates and the speed of downstream learning. Empirical evidence from experiments comparing transformers against alternative architectures (e.g., MLPs, LSTMs) would be crucial to support these claims, revealing whether the benefits of longer contexts outweigh the increased mixing times in practice. Finally, the analysis should address the implications for foundation models in RL, illustrating how the need to emulate diverse behavior policies can necessitate substantially longer context lengths in transformers than those used by individual policies in the training data, leading to unique challenges in model evaluation and deployment.

Foundation Model RL#

The concept of “Foundation Model RL” blends the power of large language models with reinforcement learning. Foundation models, pre-trained on massive datasets, offer a strong starting point, enabling faster learning and better generalization in RL. However, this approach presents challenges. One key challenge is the context length, the amount of past interaction history the model considers. Longer contexts improve performance by capturing more nuanced dependencies but dramatically increase computational cost and mixing time—the time it takes to reliably evaluate a policy’s performance. The authors highlight the crucial trade-off between leveraging the expressive power of long contexts and the associated computational burden. Optimizing this trade-off is essential for successful application of foundation models in real-world RL settings.

Future Directions#

The research paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally explore several key areas. Firstly, a deeper investigation into the interplay between context length, mixing times, and the choice of policy architecture is crucial. This requires exploring alternative architectures beyond Transformers, perhaps leveraging hierarchical structures or memory-augmented designs to mitigate the computational costs and improve mixing times associated with long contexts. Secondly, the application of these insights to more complex, real-world environments should be a primary focus. This would entail rigorous empirical evaluation in partially observable settings with inherent non-Markovian dependencies, considering domains involving continual learning or multi-task learning scenarios where efficient exploration and evaluation are especially critical. Thirdly, the theoretical framework could be enhanced by incorporating more realistic assumptions, potentially involving stochastic policies or noisy observations. Finally, investigating the practical implications of the mixing time tradeoff in the development and evaluation of foundation models for reinforcement learning is paramount. Addressing the potential for overfitting when training models with long context lengths, while maintaining the desired ability to model complex behavior, would be a particularly insightful avenue of research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates two toy examples used in the paper to demonstrate the effect of context length on mixing time. The first example shows how irrelevant state variables increase mixing time when included in the policy’s input. The second demonstrates how independent subtasks can be handled more efficiently by conditioning on relevant variables only.

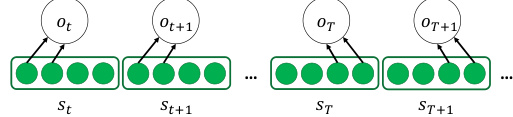

The figure shows the relationship between the average mixing time and the context length (k) during online reinforcement learning. The average mixing time is calculated for different context lengths (k=1, 2, 4, 10) and across various reward rates. The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals based on 100 independent runs. The plot demonstrates that longer context lengths generally lead to higher average mixing times, particularly at higher reward rates. The absence of the k=1 line at higher reward rates is attributed to the fact that the reward rate never reaches higher values for this setting.

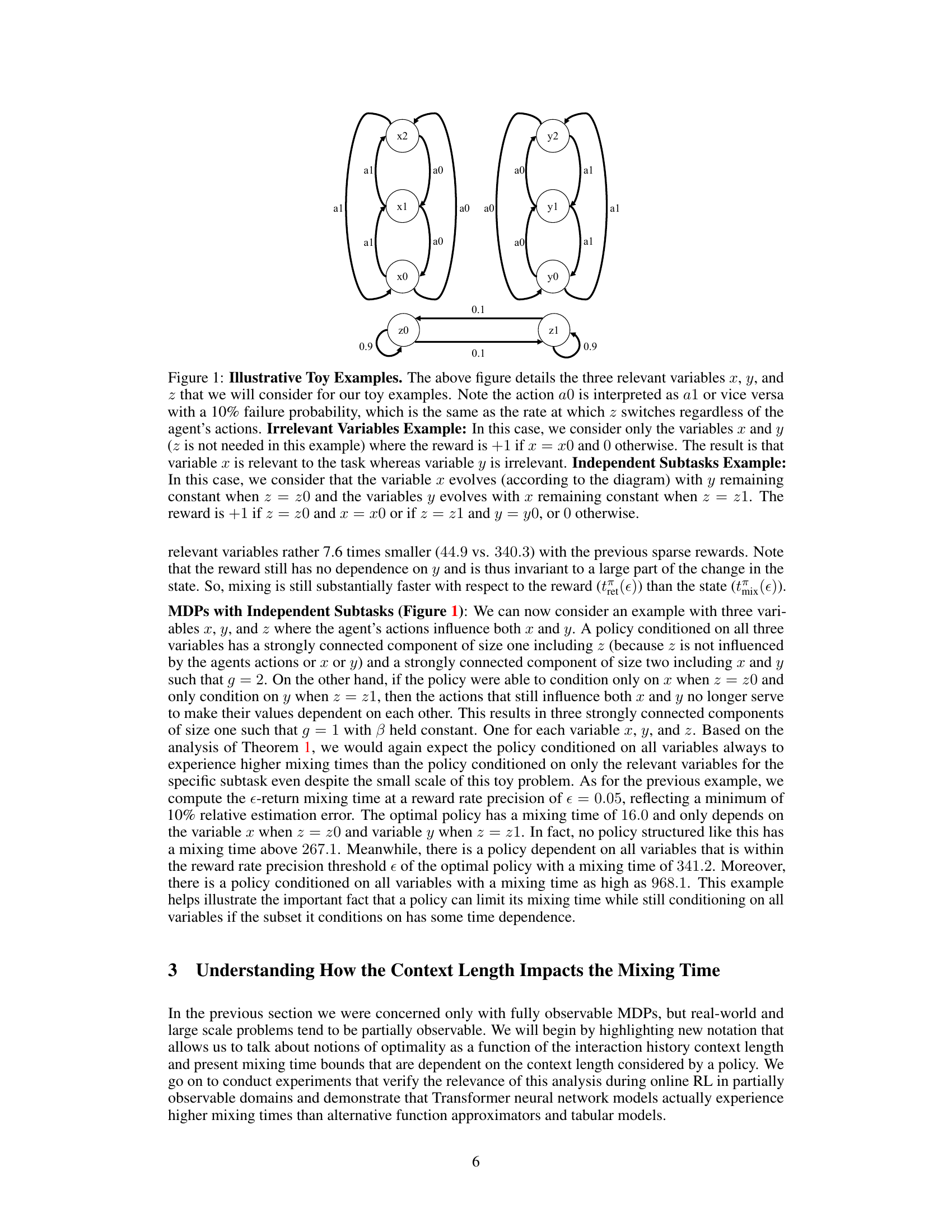

This figure shows the average mixing time for different reinforcement learning architectures (tabular, MLP, LSTM, and Transformer) across various reward rates. The x-axis represents the average reward rate achieved by the agent, and the y-axis represents the average mixing time. Each line represents a different architecture, and the shaded area around each line represents the 95% confidence interval. The figure is broken into subplots, each corresponding to a different context length (k). The results illustrate the trade-off between context length and mixing time, showing how longer context lengths can lead to increased mixing times, especially for neural network architectures.

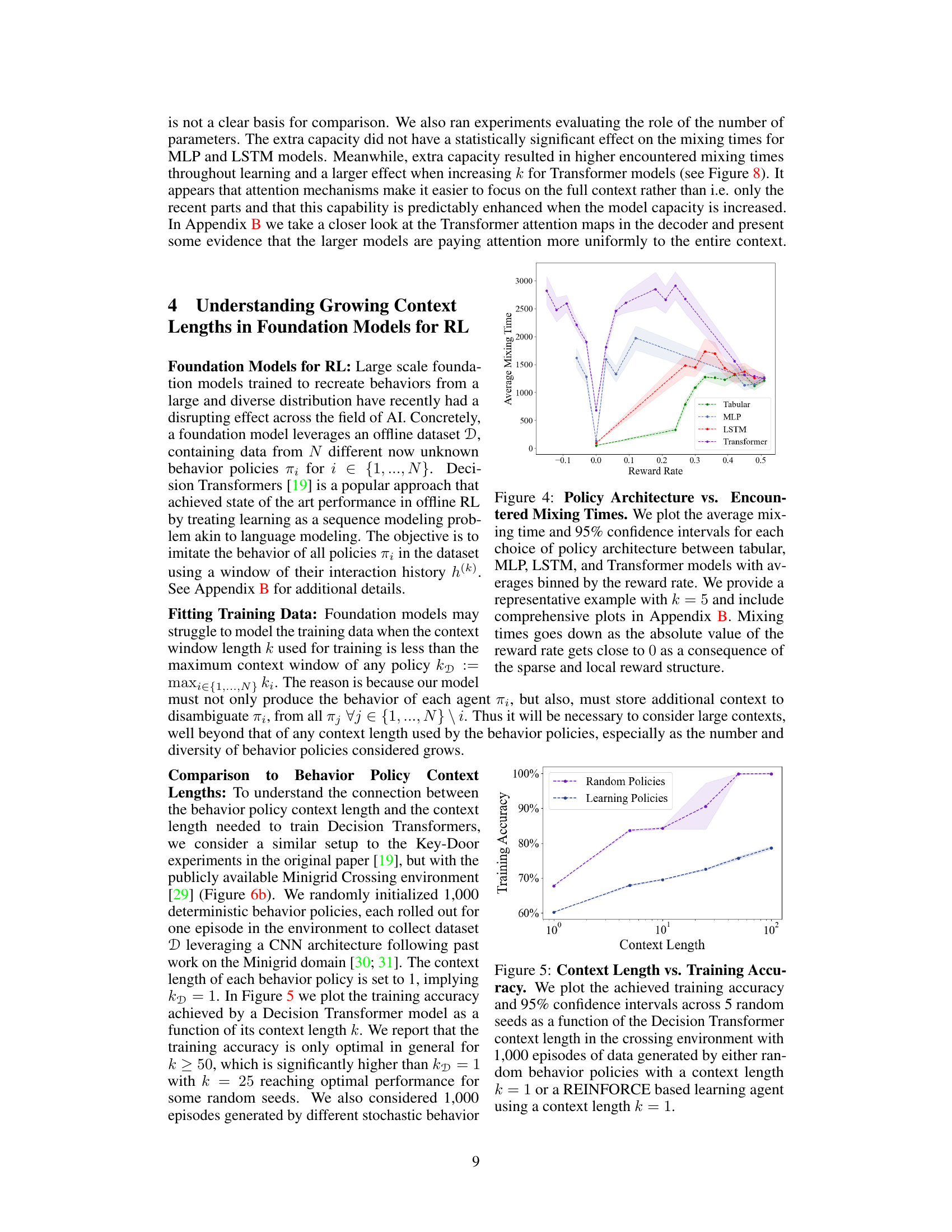

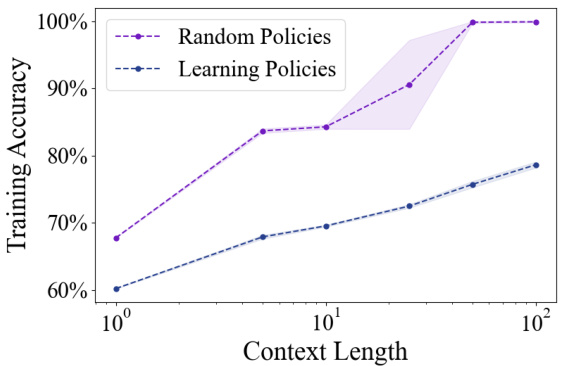

This figure shows the training accuracy of Decision Transformer models with varying context lengths. The data used for training was generated by two types of policies: random policies with a context length of 1 and learning policies (REINFORCE) also with a context length of 1. The plot demonstrates the relationship between context length used by the model during training and the resulting training accuracy. It shows that longer context lengths are needed to achieve optimal training accuracy, especially when the training data comes from learning policies.

This figure presents two simple MDP examples used to illustrate the impact of irrelevant variables and independent subtasks on mixing times. The first example shows an MDP with two state variables, x and y, where only x affects the reward. The second example has three state variables (x, y, and z), where the reward depends on which subtask is active (determined by z), and each subtask involves only one of the other variables (x or y). The diagrams show the state transitions and rewards.

This figure shows the average mixing times encountered during online reinforcement learning experiments using different policy architectures (tabular, MLP, LSTM, Transformer) for varying context lengths (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10). The average mixing time is calculated and binned by reward rate. The results illustrate the tradeoff between context length and mixing time, particularly for Transformer-based models.

This figure shows how the average mixing time changes as a function of the number of parameters in the Transformer model for different context lengths (k=2 and k=10). The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, showing variability across 100 different random seeds. It illustrates the relationship between model capacity and mixing time, suggesting that larger models, while potentially achieving higher performance, may experience longer mixing times.

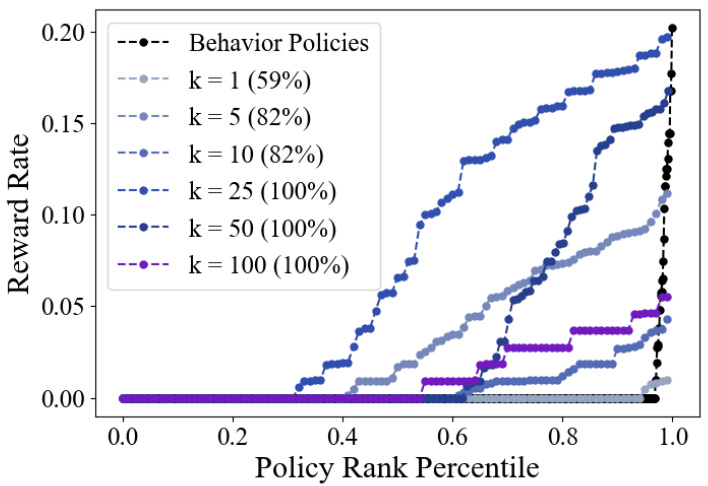

This figure compares the performance of Decision Transformers with different context lengths (k) on a crossing environment. The models were trained on data generated from random behavior policies (k=1). The evaluation involved prompting the models with various return-to-go values (0 to 1.0) and measuring their reward rate. The figure shows how increasing the context length improves the model’s ability to match the performance of the behavior policies, although longer context lengths may also lead to overfitting.

Full paper#