↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) is computationally expensive. LoRA, a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method, reduces costs but suffers from slow convergence. This necessitates more compute time and sometimes results in worse performance than full fine-tuning.

The paper introduces LoRA-GA, a novel initialization method for LoRA that addresses the slow convergence issue. By approximating the gradients of the low-rank matrices with those of the full weight matrix, LoRA-GA achieves a convergence rate comparable to full fine-tuning while simultaneously attaining comparable or better performance. Extensive experiments across various models and datasets demonstrate LoRA-GA’s effectiveness in accelerating convergence and enhancing model performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models because it presents a novel initialization method, LoRA-GA, that significantly accelerates the convergence and improves the performance of the popular LoRA technique. This is important due to the high cost associated with fine-tuning large-scale pre-trained models. LoRA-GA offers a practical solution to improve efficiency and performance, paving the way for wider adoption of LLM fine-tuning. This opens up new avenues for future research in parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques and efficient large model training.

Visual Insights#

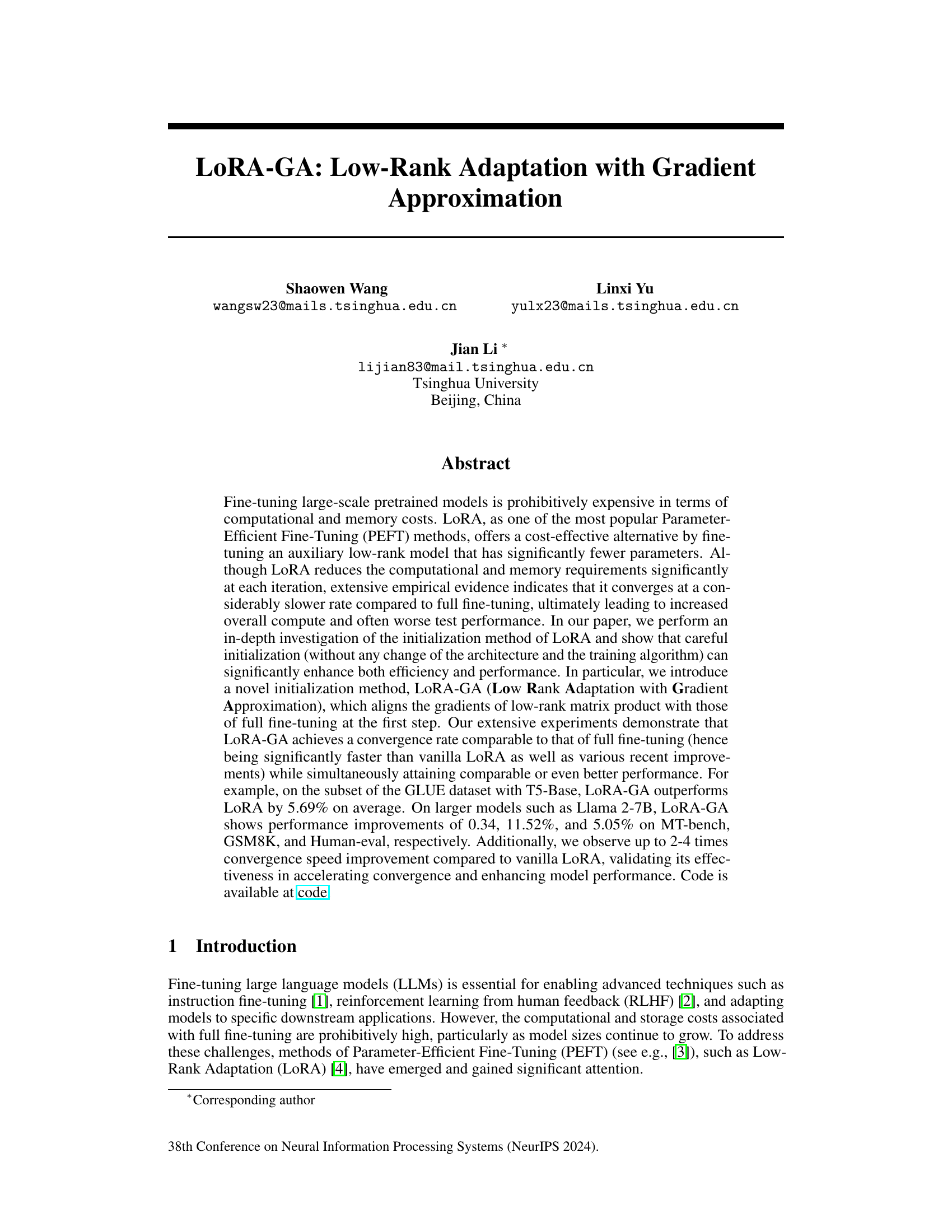

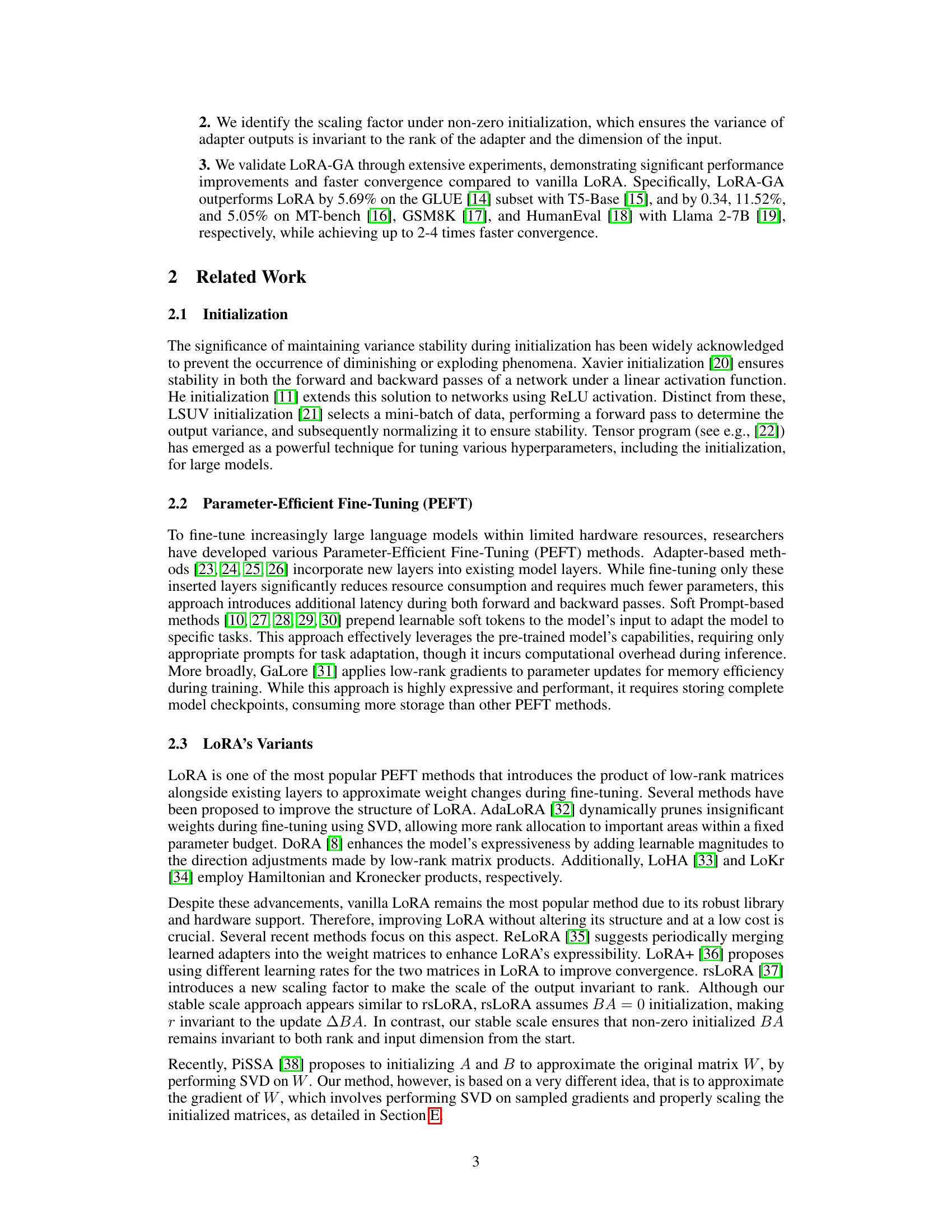

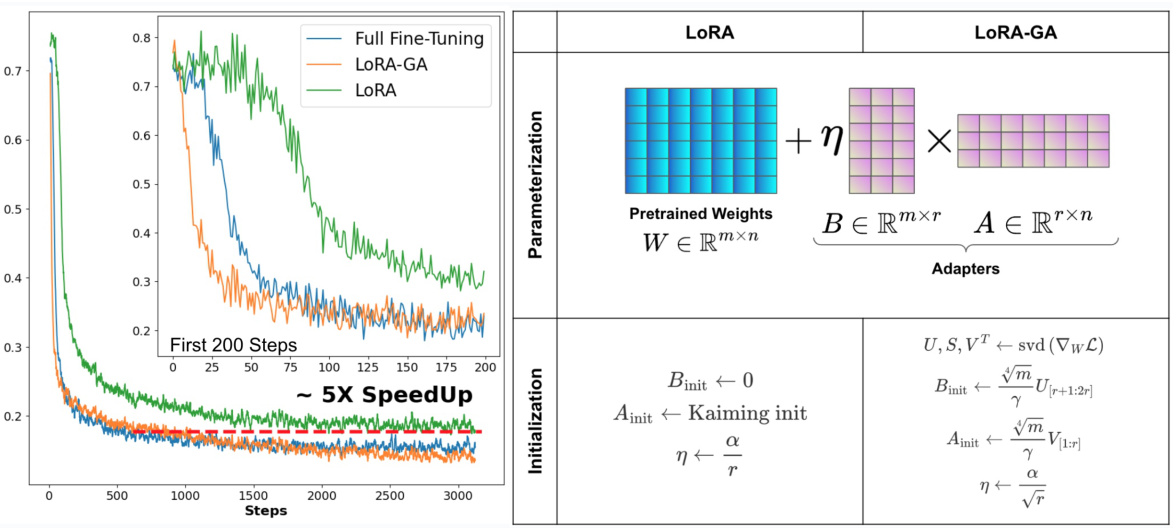

This figure shows a comparison of the training loss curves for three different methods: full fine-tuning, LoRA, and LoRA-GA, when training the Llama 2-7B model on the MetaMathQA dataset. The left panel shows that LoRA-GA converges much faster than vanilla LoRA, achieving a speedup of 5x in the first 200 steps, and converging at a similar rate to full fine-tuning. The right panel illustrates the key difference between the initialization procedures of LoRA and LoRA-GA. LoRA uses random initialization for its adapter weights (A and B), while LoRA-GA leverages the eigenvectors of the gradient matrix to initialize the adapters, leading to faster convergence.

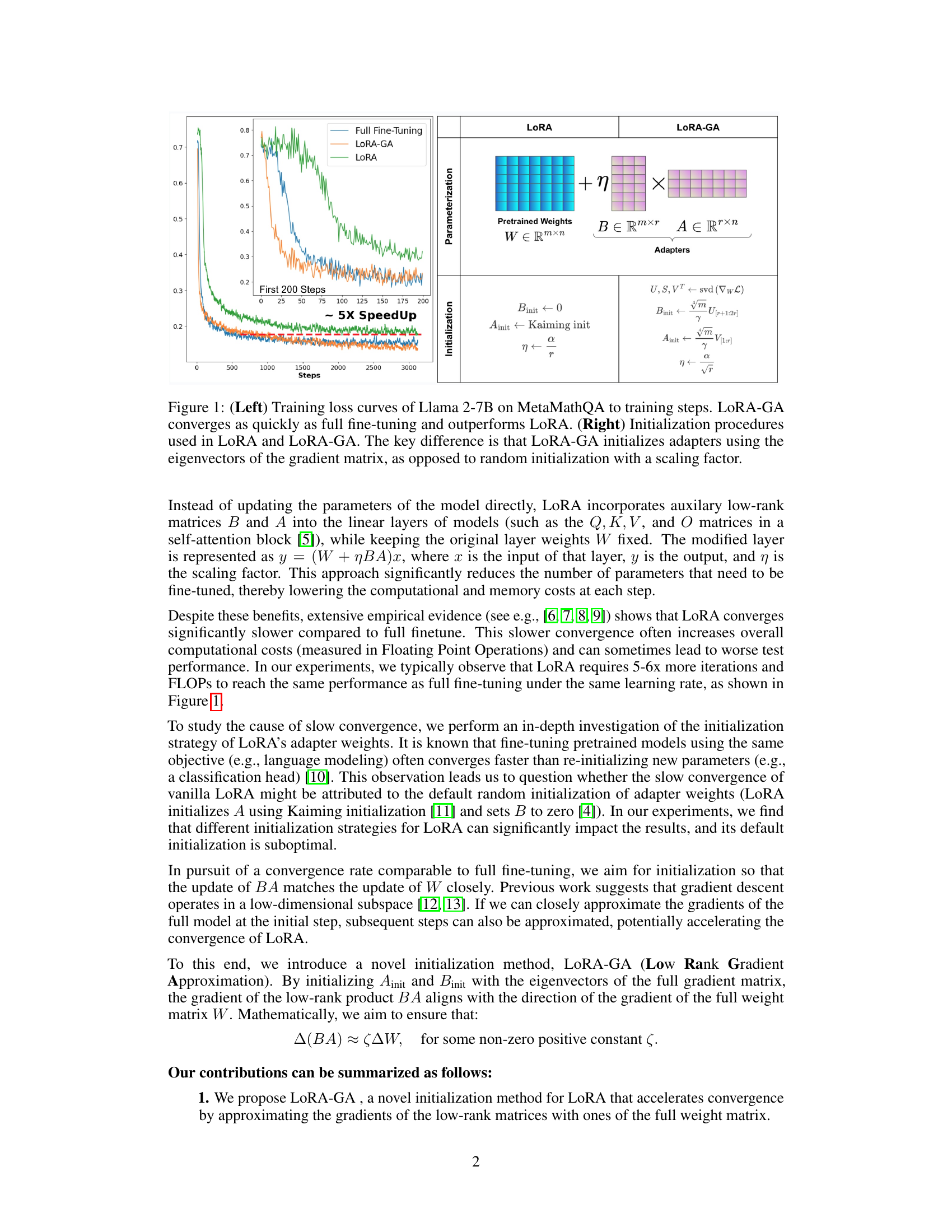

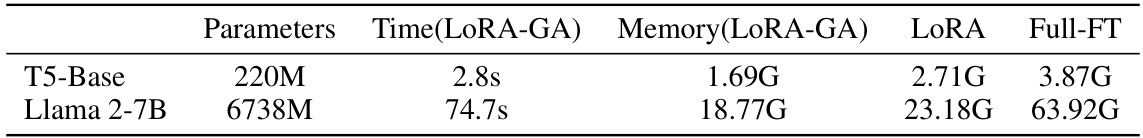

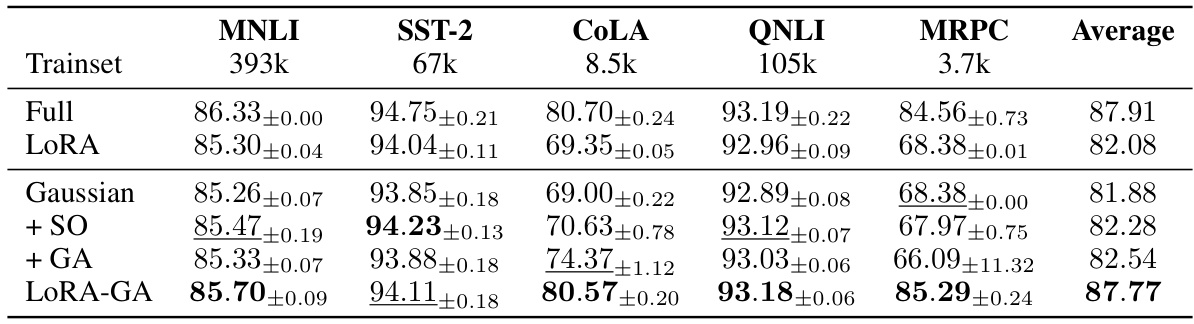

This table presents the results of fine-tuning the T5-base model on a subset of the GLUE benchmark using several methods: full fine-tuning (Full-FT), vanilla LoRA, and various LoRA variants. The performance is evaluated based on the average accuracy across five different tasks within the GLUE benchmark: MNLI, SST-2, CoLA, QNLI, and MRPC. The table allows for a comparison of the performance and efficiency of different parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques against full fine-tuning.

In-depth insights#

LoRA’s Slow Start#

The phenomenon of LoRA’s slow start, where the convergence rate is significantly slower than full fine-tuning despite its computational efficiency, is a crucial observation. The root cause appears to lie in the default initialization strategy of LoRA’s adapter weights. While LoRA reduces the number of trainable parameters, the random initialization of these adapters can hinder the learning process, requiring significantly more iterations to achieve comparable or better results than full fine-tuning. Careful initialization is key to bridging this performance gap. This slow convergence not only affects training time but also potentially leads to suboptimal test performance if sufficient training steps are not taken. Therefore, it is essential to investigate and improve LoRA initialization methods to fully harness its efficiency and avoid the downsides of slow convergence. Approaches such as LoRA-GA focus on aligning initial gradients of low-rank matrix products with those of full fine-tuning to enhance the convergence speed. This highlights the importance of optimizing the interaction between the pre-trained weights and the adapted low-rank matrices for efficient and effective fine-tuning.

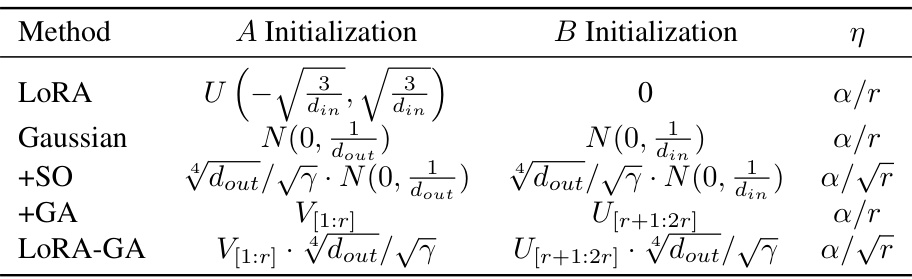

Gradient Alignment#

The concept of gradient alignment in the context of low-rank adaptation methods for large language models (LLMs) centers on aligning the gradients of the low-rank update with the gradients of full fine-tuning. This is crucial because standard low-rank adaptation, such as LoRA, often suffers from slow convergence compared to full fine-tuning. By ensuring gradient alignment, especially at the initial training steps, the method aims to accelerate convergence and potentially improve overall model performance. The underlying principle is that if the low-rank updates closely mimic the full gradient updates from the outset, the model will progress more efficiently towards the optimal solution. Careful initialization strategies play a critical role in achieving gradient alignment, often involving techniques like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the full model’s gradients to inform the initialization of low-rank matrices. Successful gradient alignment is expected to bridge the performance gap between low-rank adaptation and full fine-tuning, making parameter-efficient fine-tuning a more viable option for resource-constrained scenarios.

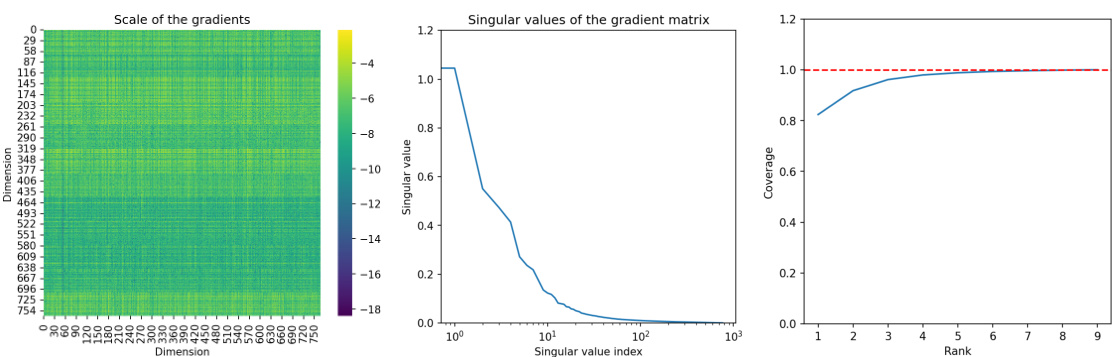

Scale & Rank#

The concepts of scale and rank are crucial in the context of parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like LoRA. Rank refers to the dimensionality of the low-rank matrices used to approximate full weight updates, impacting model expressiveness and computational cost. A higher rank allows for richer approximations but increases the number of trainable parameters. Scale, on the other hand, relates to the magnitude of the updates applied to the model’s weights. An improperly scaled update can lead to instability during training, causing performance degradation or even divergence. The interplay between these two is complex; a well-chosen rank enables a balance between performance and efficiency, while appropriate scaling ensures stable and effective training. The paper investigates novel initialization methods to address these issues, demonstrating that careful management of both scale and rank is key to achieving faster convergence and improved performance in low-rank adaptation.

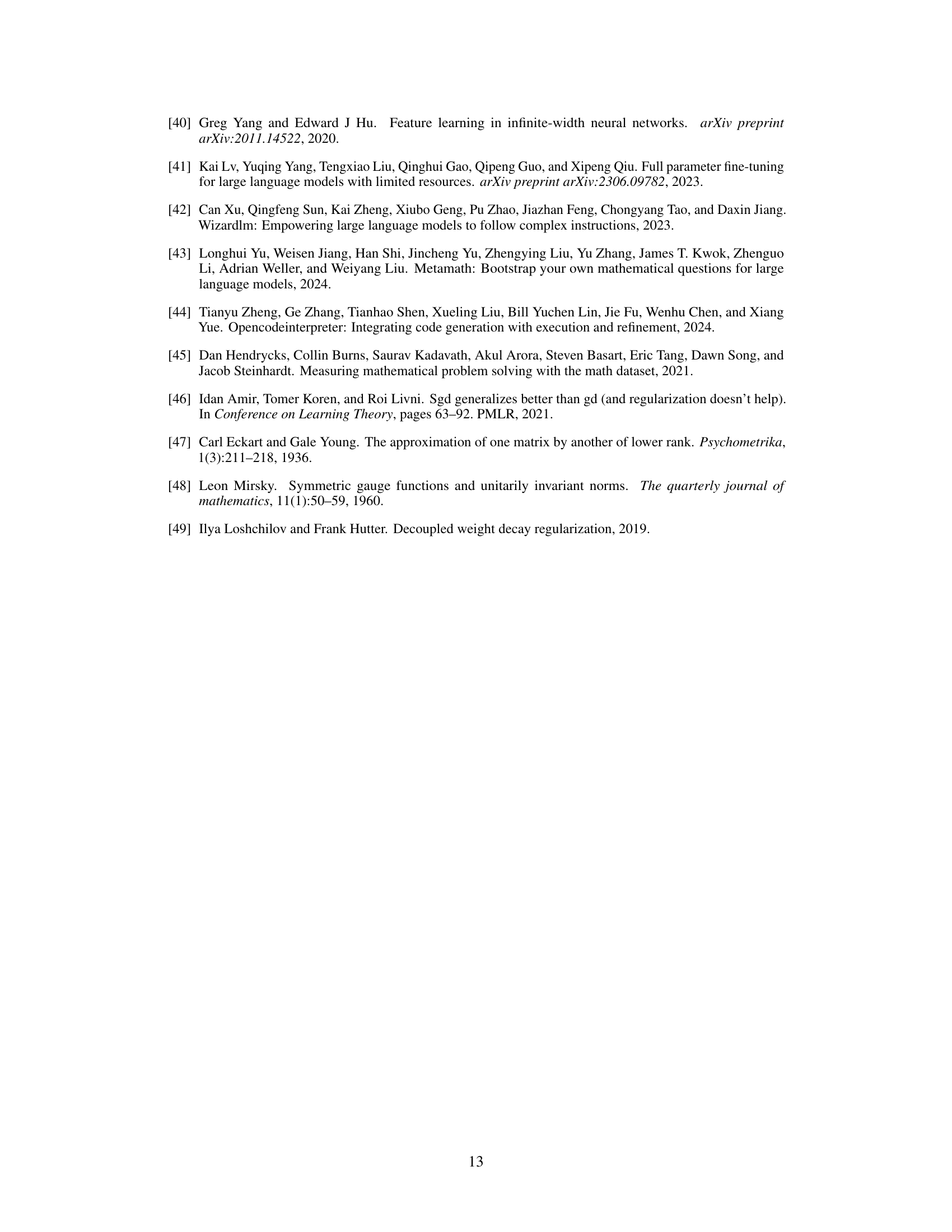

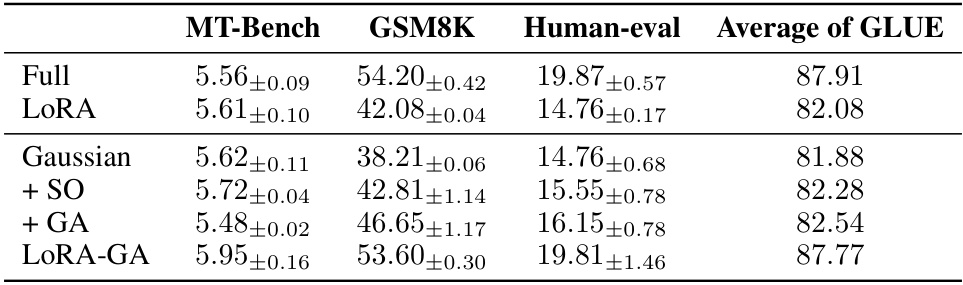

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically investigates the contribution of individual components within a complex system. In the context of a machine learning model, this often involves removing or altering specific parts (e.g., modules, hyperparameters, or training procedures) to understand their impact on the overall performance. A well-designed ablation study is crucial for establishing causality, showing which aspects truly contribute to the model’s success and not just correlation. For example, it might demonstrate that a novel initialization method significantly improves performance compared to the baseline. The study should carefully control for confounding variables by only modifying one component at a time, while holding other factors constant, allowing for clear isolation of each component’s effect. Results are often presented visually, such as through graphs displaying performance metrics across different configurations, aiding in the interpretation and understanding of the contribution of different model components. Ultimately, a comprehensive ablation study provides valuable insights into model behavior and serves as strong evidence for the validity of the proposed improvements.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this LoRA-GA work could explore several promising avenues. Extending LoRA-GA to other PEFT methods beyond vanilla LoRA is crucial to determine its broad applicability and effectiveness. Investigating the optimal choice of rank and its relationship to model size and task complexity would further enhance LoRA-GA’s practical utility. A comprehensive analysis of the scaling factor’s impact across diverse learning rates and model architectures is needed for robust performance. Finally, addressing the computational cost associated with the SVD during initialization, perhaps by exploring efficient approximation techniques or alternative initialization methods, remains a critical area for improvement. These investigations could significantly enhance LoRA-GA’s efficiency and scalability, broadening its impact on large-scale model adaptation.

More visual insights#

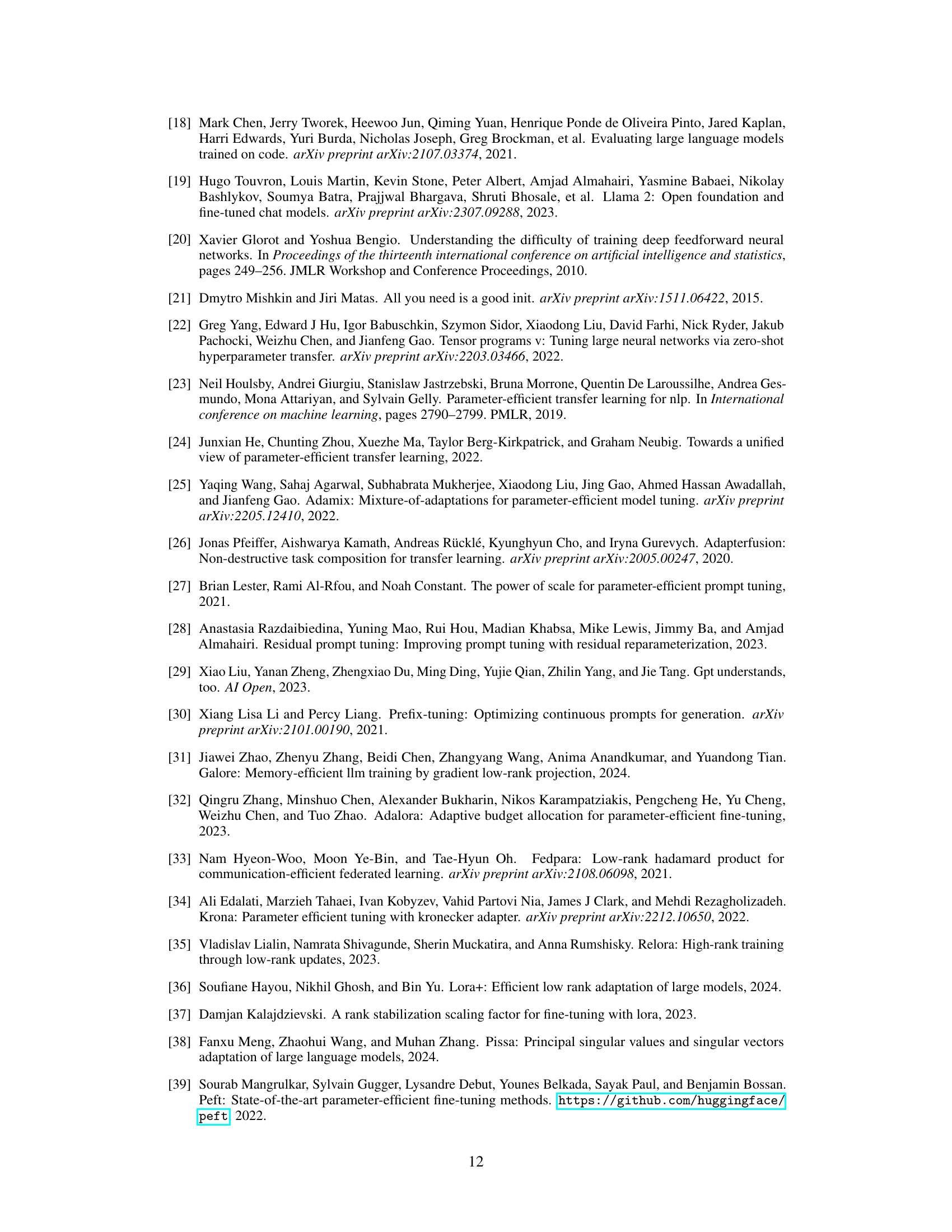

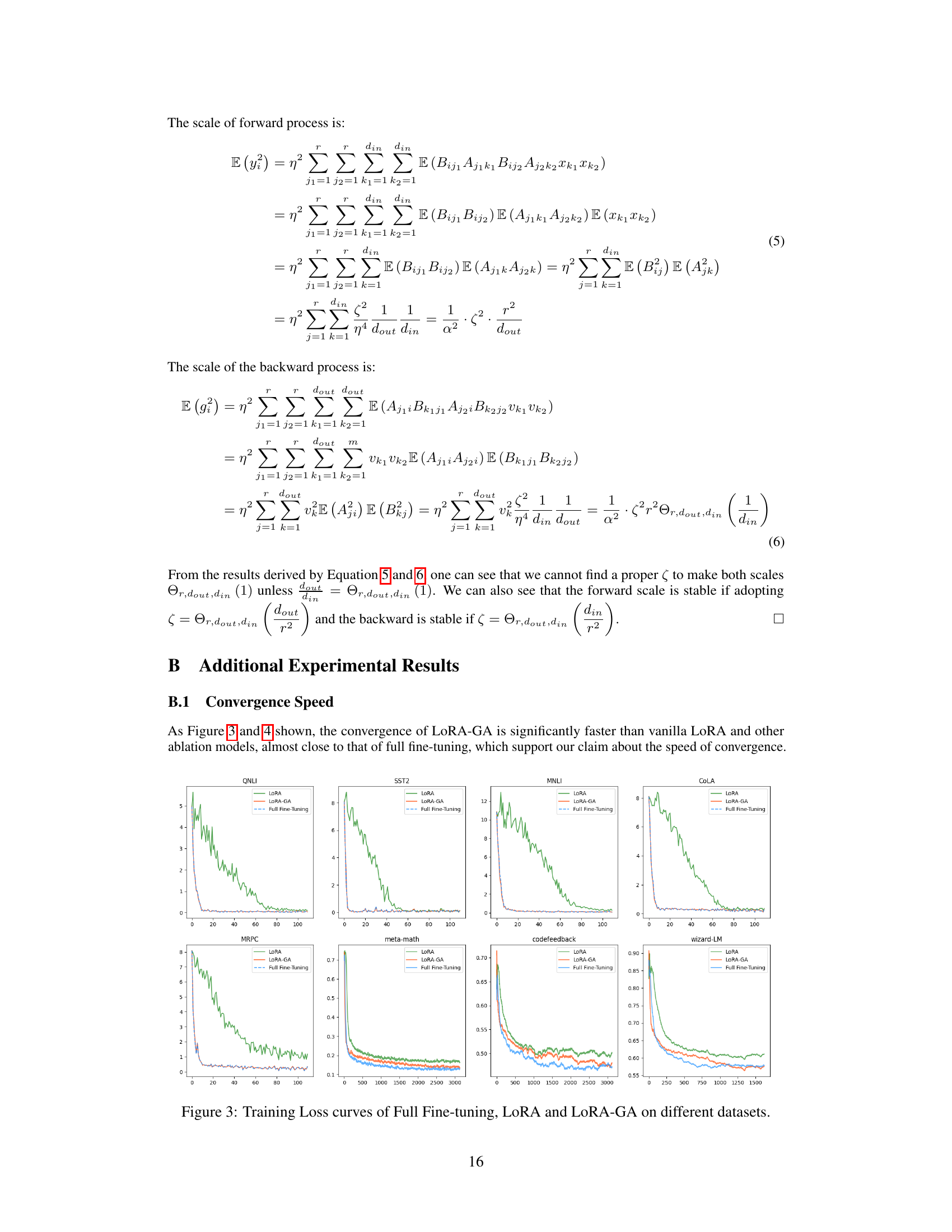

More on figures

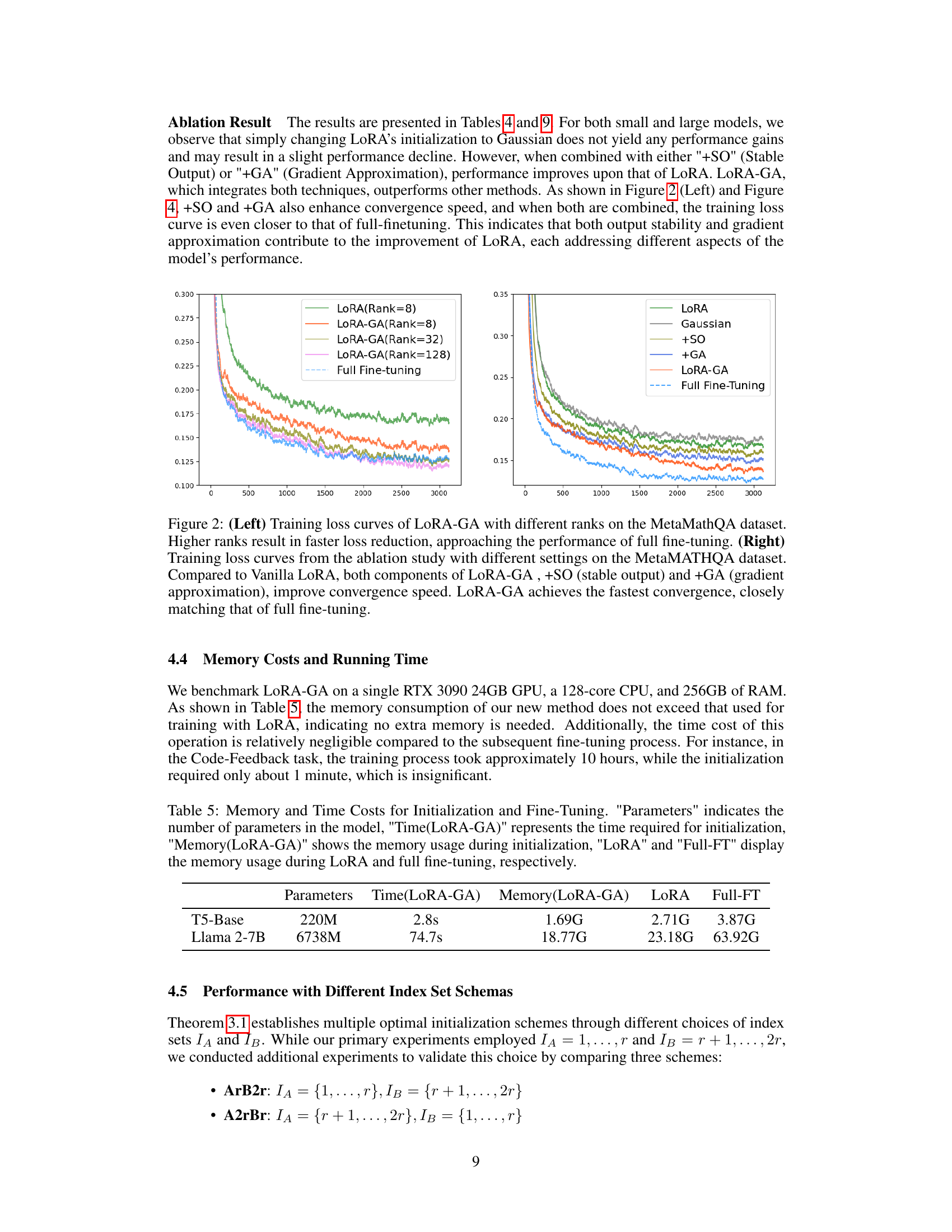

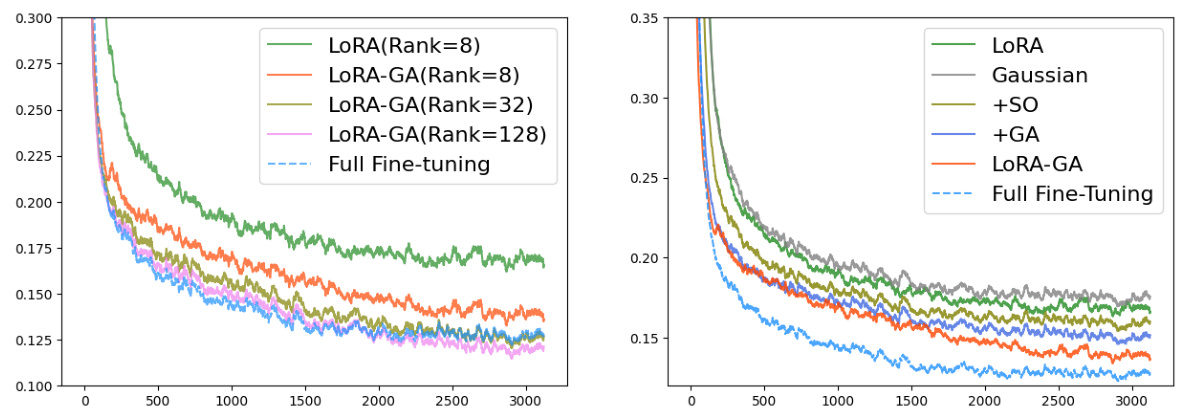

The figure on the left shows training loss curves for Llama 2-7B model on the MetaMathQA dataset, comparing LoRA-GA, vanilla LoRA, and full fine-tuning. LoRA-GA demonstrates a convergence rate similar to full fine-tuning, significantly faster than vanilla LoRA. The figure on the right illustrates the initialization methods of LoRA and LoRA-GA, highlighting the key difference: LoRA-GA uses gradient approximation to align low-rank matrix gradients with those of the full model at the initial step, unlike LoRA’s random initialization with a scaling factor.

The figure on the left shows the training loss curves for Llama 2-7B model on MetaMathQA dataset. It compares the convergence speed of three methods: full fine-tuning, vanilla LoRA, and the proposed LoRA-GA. The results show that LoRA-GA converges as fast as full fine-tuning and significantly faster than vanilla LoRA. The figure on the right illustrates the initialization procedures for LoRA and LoRA-GA. LoRA uses random initialization with a scaling factor, while LoRA-GA initializes its adapters using eigenvectors of the gradient matrix, leading to faster convergence.

The left panel of the figure shows the training loss curves for Llama 2-7B model on the MetaMathQA dataset. It compares the convergence speed of three different methods: full fine-tuning, vanilla LoRA, and the proposed LoRA-GA. The results show that LoRA-GA achieves a convergence rate comparable to full fine-tuning, significantly faster than vanilla LoRA. The right panel illustrates the initialization procedures for both LoRA and LoRA-GA. It highlights that the key difference lies in the adapter initialization: LoRA uses random initialization, while LoRA-GA uses the eigenvectors of the gradient matrix, leading to improved convergence.

The figure on the left shows the training loss curves for three different methods: Full Fine-tuning, LoRA, and LoRA-GA. It demonstrates that LoRA-GA converges much faster, achieving a similar convergence rate to full fine-tuning, and significantly outperforming the original LoRA method. The figure on the right provides a visual illustration of the initialization procedures for both LoRA and LoRA-GA, highlighting the key difference in how they initialize adapter matrices. LoRA-GA uses the eigenvectors of the gradient matrix for initialization, aiming to align gradients more closely with full fine-tuning, unlike LoRA’s random initialization with a scaling factor.

More on tables

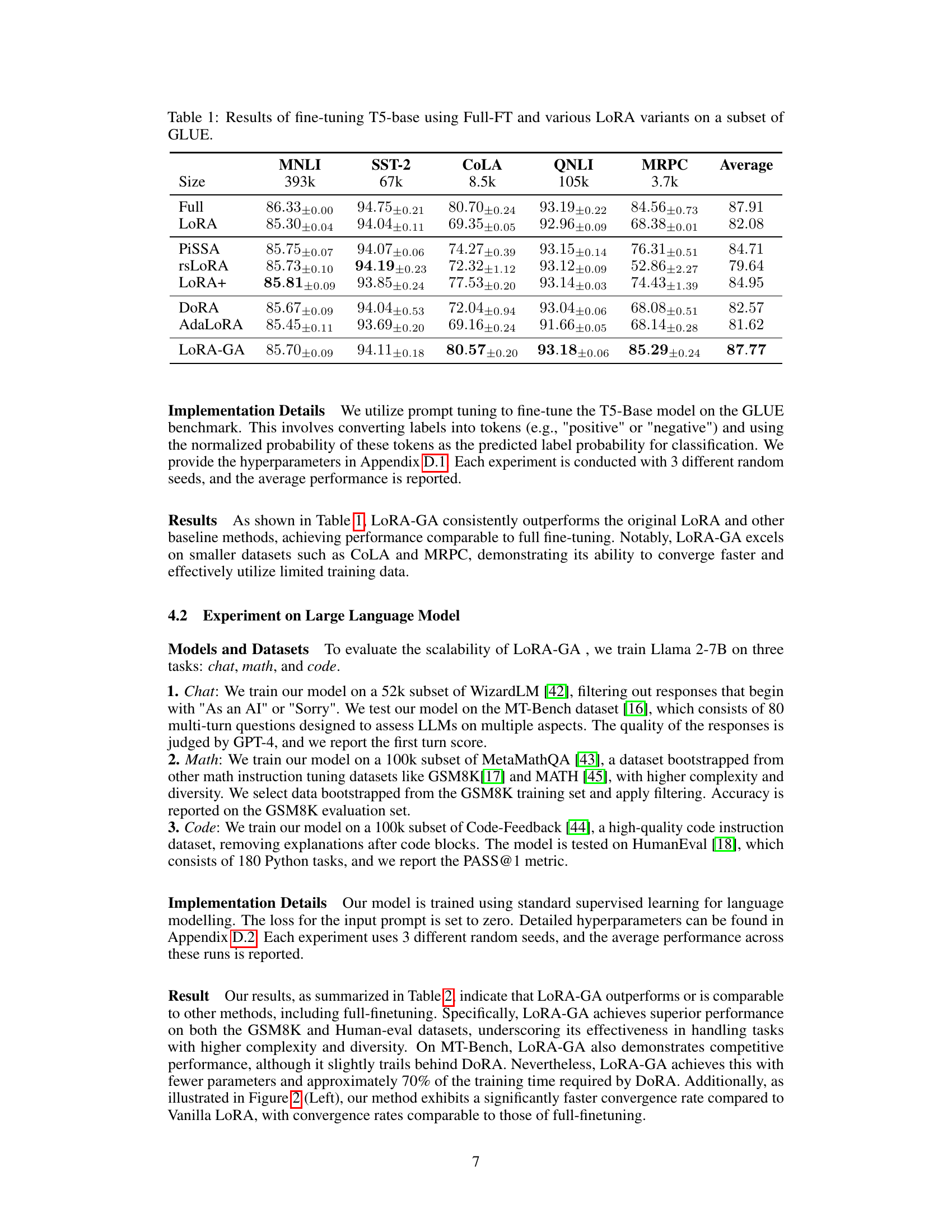

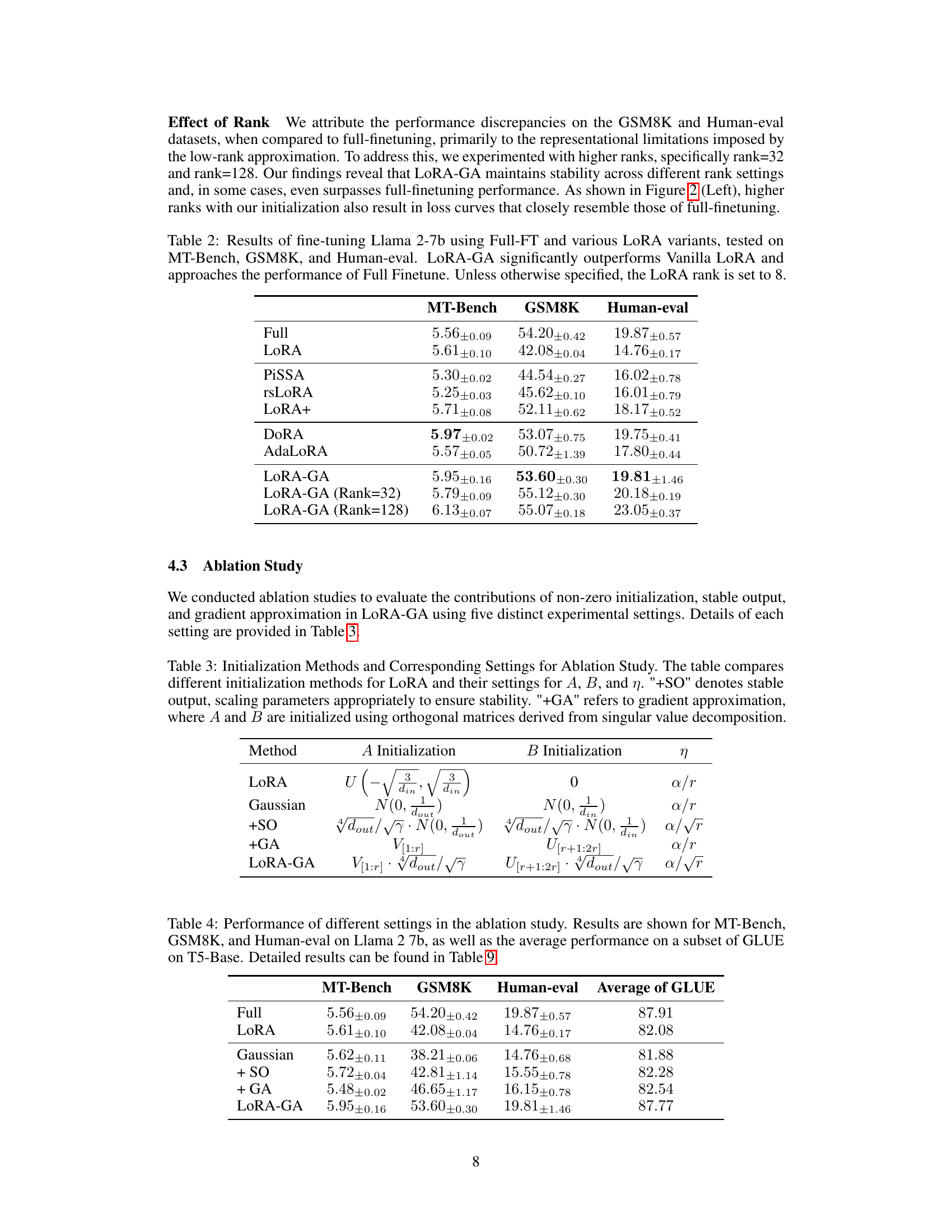

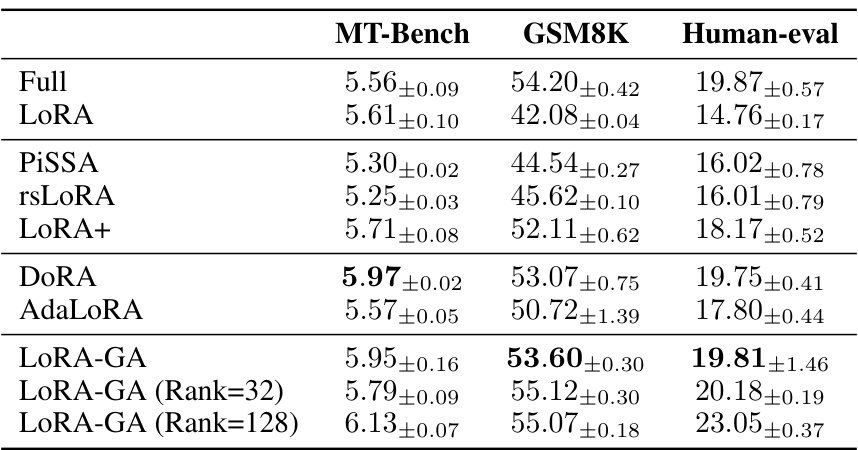

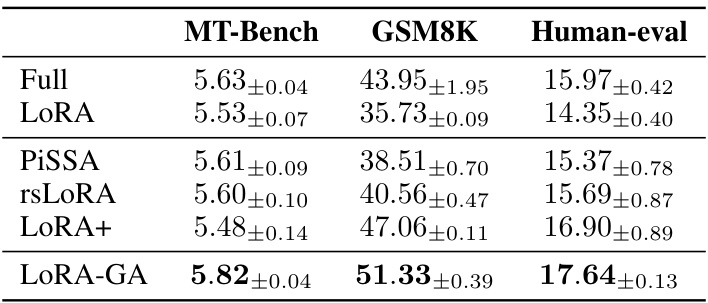

This table presents the performance comparison of different fine-tuning methods on three downstream tasks: MT-Bench (multi-turn dialogue), GSM8K (mathematics), and HumanEval (code generation). The methods compared include full fine-tuning (Full), vanilla LoRA, several LoRA variants (PISSA, rsLoRA, LoRA+, DORA, AdaLoRA), and the proposed LoRA-GA method. The results demonstrate that LoRA-GA significantly outperforms vanilla LoRA and achieves performance comparable to full fine-tuning, especially on the GSM8K and HumanEval tasks, even when using a relatively low rank (8). Results are also shown for LoRA-GA with higher ranks (32 and 128) which further improve the performance. The table highlights the effectiveness of LoRA-GA in accelerating convergence and improving performance across different model sizes and task types.

This table presents the results of fine-tuning a T5-base model on a subset of the GLUE benchmark using several methods: Full Fine-tuning (Full-FT), Vanilla LoRA, several LoRA variants (PISSA, rsLoRA, LoRA+, AdaLoRA), and LoRA-GA. The performance is measured by the average accuracy across different tasks within the GLUE subset (MNLI, QNLI, SST-2, CoLA, and MRPC). The table highlights the superior performance of LoRA-GA compared to the baseline methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in achieving performance comparable to full fine-tuning.

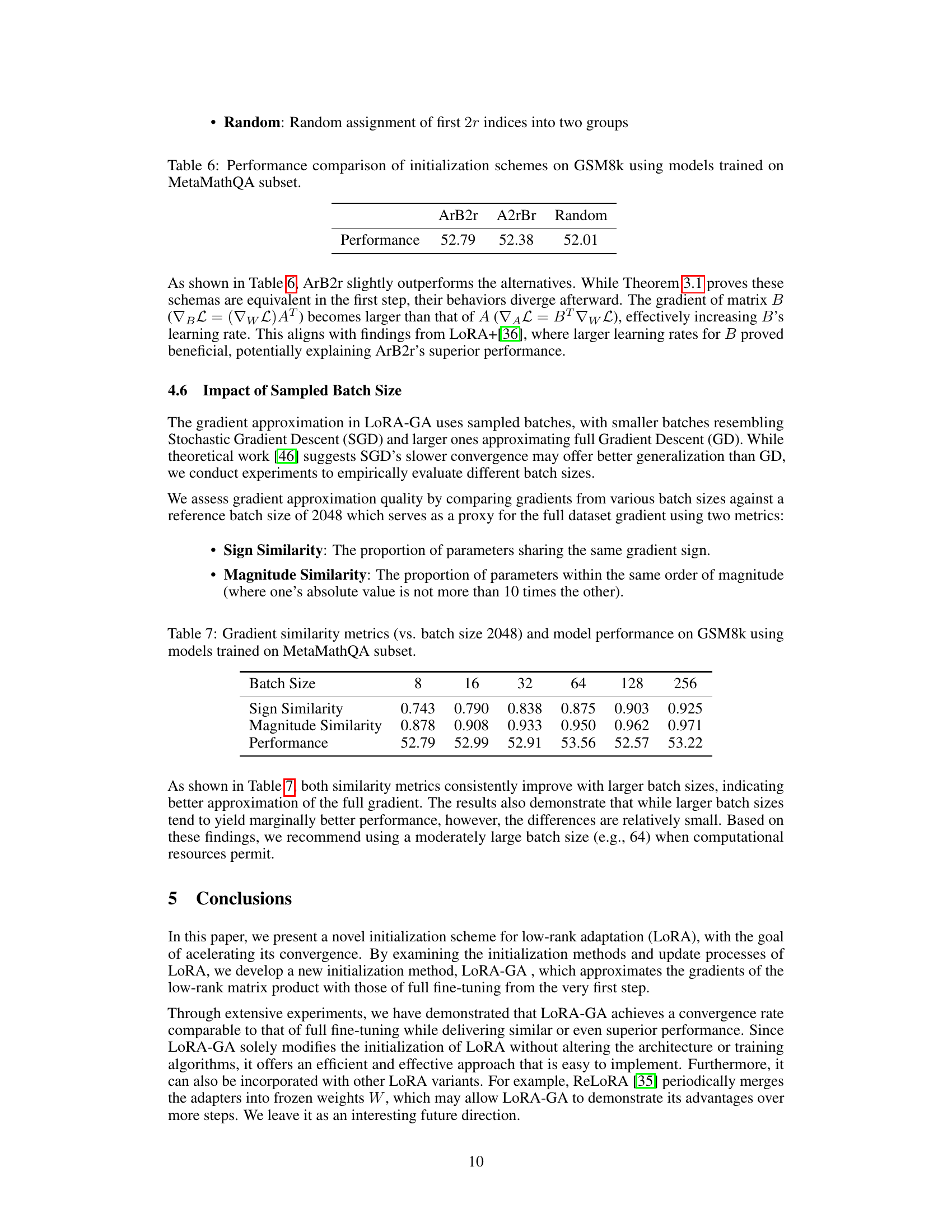

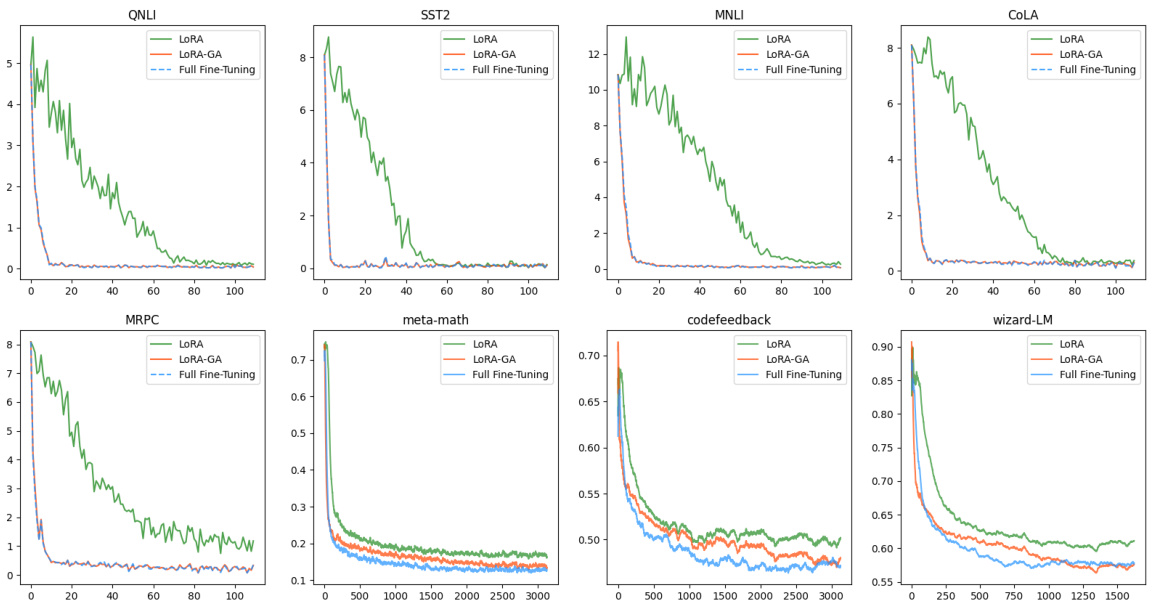

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of different initialization methods for LoRA on several benchmark datasets (MT-Bench, GSM8K, Human-eval) and a subset of GLUE. The methods compared include the baseline LoRA, LoRA with Gaussian initialization, LoRA with stable output (+SO), LoRA with gradient approximation (+GA), and the proposed LoRA-GA method. The table shows the performance of each method in terms of various metrics specific to the benchmark datasets, providing a quantitative comparison to highlight the impact of each component of LoRA-GA.

This table presents the results of fine-tuning the T5-base model on a subset of the GLUE benchmark using different methods: Full Fine-tuning (Full-FT), vanilla LoRA, several LoRA variants (PISSA, rsLoRA, LoRA+, AdaLoRA), and LoRA-GA. The performance is measured by the average accuracy across five GLUE tasks (MNLI, SST-2, CoLA, QNLI, and MRPC), with the size of each task’s dataset shown in the table. The results highlight the performance improvements achieved by LoRA-GA compared to other methods, especially on smaller datasets. The ± values represent the standard deviation observed over 3 different random seeds for each experiment.

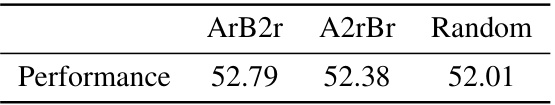

This table presents the performance comparison of three different initialization schemes (ArB2r, A2rBr, and Random) for the LoRA-GA method on the GSM8k dataset. Models were trained on a subset of the MetaMathQA dataset. The ‘Performance’ column shows the accuracy achieved by each initialization scheme, demonstrating the impact of the initialization strategy on model performance.

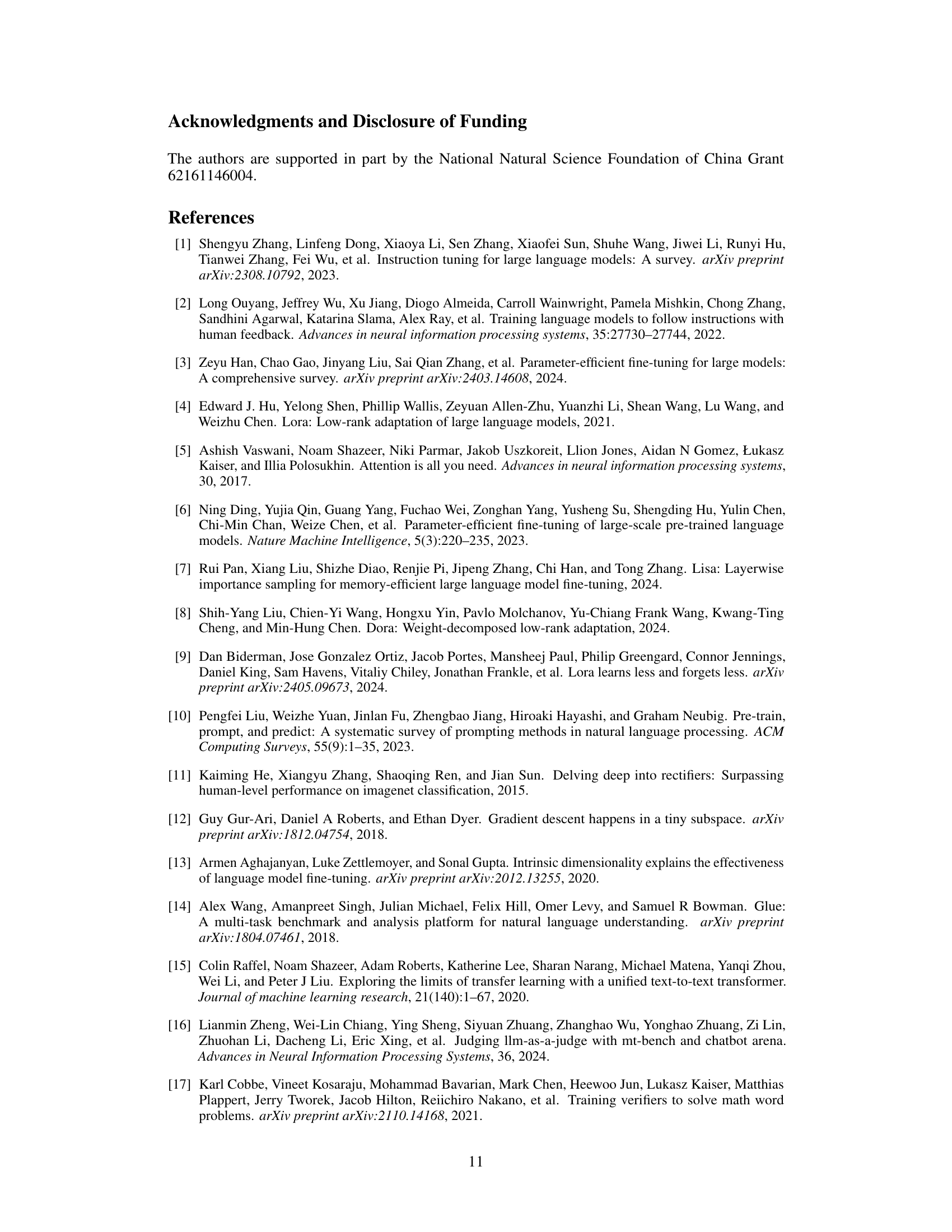

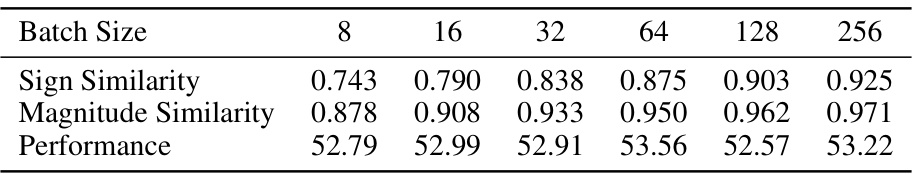

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of different batch sizes on the quality of gradient approximation in the LoRA-GA method. Two metrics, Sign Similarity and Magnitude Similarity, measure how well the gradients from smaller batch sizes approximate the gradients from a larger (2048) batch size, serving as a proxy for the full dataset. The table also shows the model’s performance (on the GSM8k dataset) corresponding to each batch size. This helps to assess the tradeoff between the accuracy of gradient approximation and model performance with varying batch sizes.

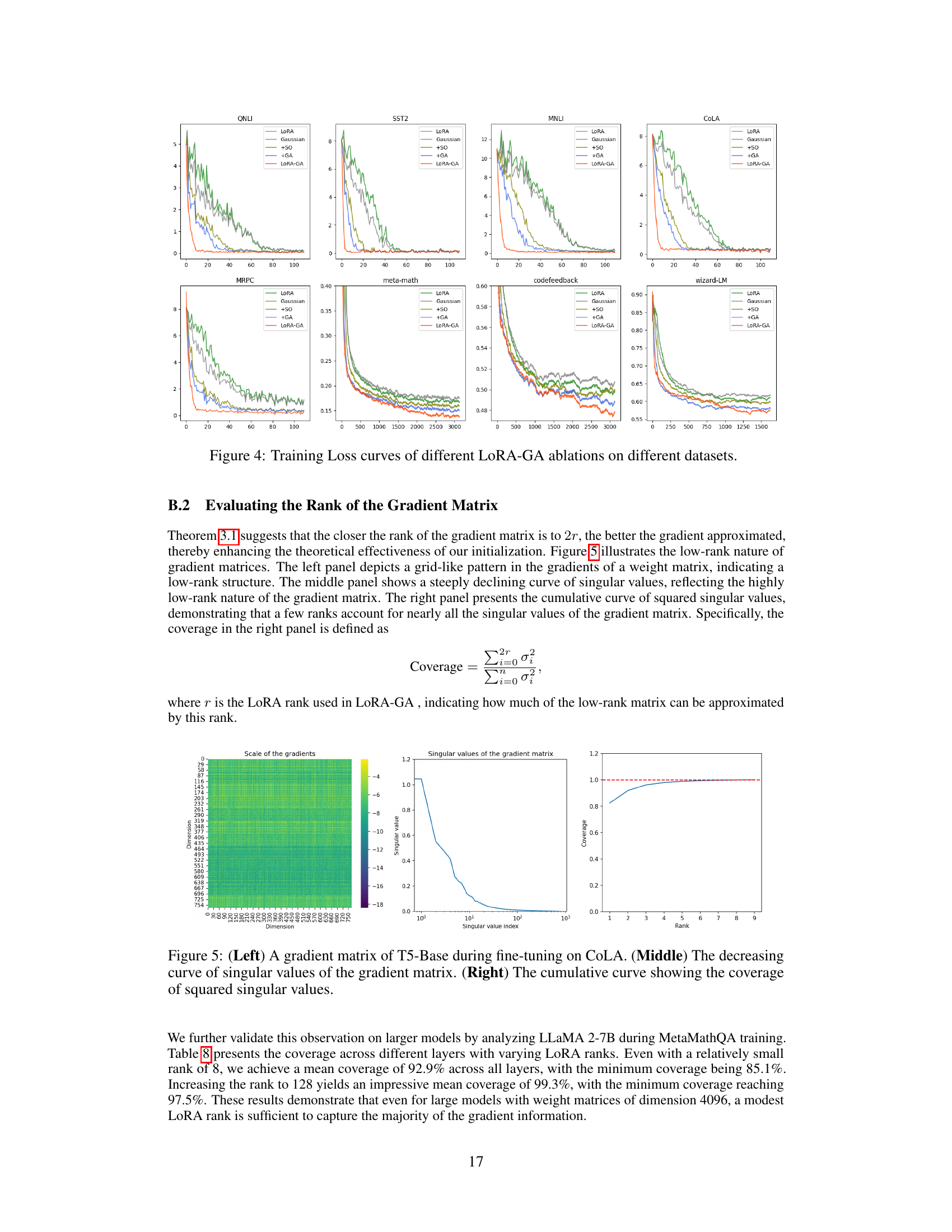

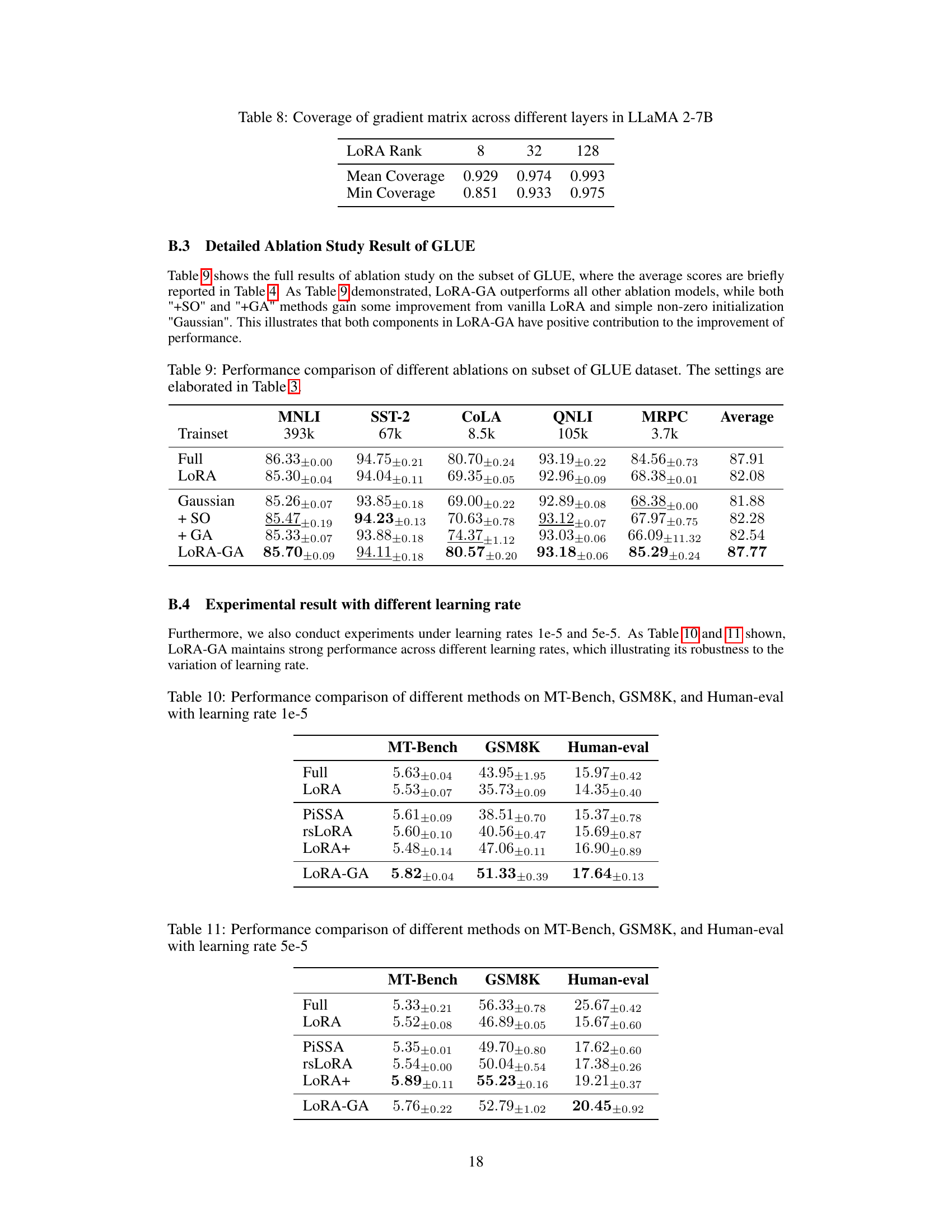

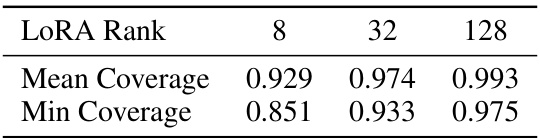

This table presents the coverage of the gradient matrix across different layers in the LLaMA 2-7B model for three different LoRA ranks (8, 32, and 128). The mean and minimum coverage values are shown for each rank, indicating how well the low-rank approximation captures the gradient information. Higher ranks generally lead to better coverage.

This table presents the results of fine-tuning a T5-base model on a subset of the GLUE benchmark using different methods: full fine-tuning (Full-FT), vanilla LoRA, several LoRA variants, and LoRA-GA. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on five different GLUE tasks (MNLI, SST-2, CoLA, QNLI, MRPC) and an average accuracy across all tasks. This demonstrates the performance improvements achieved by LoRA-GA compared to other methods, particularly in achieving performance comparable to full fine-tuning.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of several methods (Full Fine-tuning, LoRA, PiSSA, rsLoRA, LoRA+, and LoRA-GA) on three different benchmark datasets (MT-Bench, GSM8K, and Human-eval). The results are specifically for a learning rate of 1e-5. The table showcases the performance differences between the methods, highlighting LoRA-GA’s improved performance compared to the baseline LoRA method.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (Full, LoRA, PISSA, rsLoRA, LoRA+, and LoRA-GA) on three different benchmark datasets (MT-Bench, GSM8K, and Human-eval) using Llama 2-7B model. The experiments were conducted with learning rate of 5e-5. Each entry shows the average performance across different runs and their standard deviation. The results highlight the relative performance of each method on various tasks including multi-turn dialogue, mathematical reasoning, and code generation.

This table presents the performance of three different LoRA variants (LoRA, LoRA+, and LoRA-GA) on the full MetaMathQA dataset across four training epochs. The results are averaged over two random seeds. The table demonstrates the performance improvement of LoRA-GA over time, showing its superiority to the other LoRA methods in terms of accuracy on this mathematical reasoning dataset.

Full paper#