↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current image compositing techniques often struggle with complex spatial relationships and accurate object placement, especially in 3D scenes. Existing methods typically operate at the 2D level, leading to unrealistic results when handling occlusion and depth. They also often fail to preserve the original identity and appearance of the objects, compromising realism.

The proposed method, Bifröst, utilizes a novel 3D-aware framework. It incorporates depth maps and a fine-tuned multi-modal large language model (MLLM) to predict object locations and guide the image generation process. This allows for precise object placement, realistic occlusion handling, and identity preservation. Experiments demonstrate that Bifröst outperforms existing methods in both qualitative and quantitative evaluations, setting a new standard for high-fidelity image compositing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel 3D-aware framework for image compositing, addressing limitations of existing 2D methods. It introduces a novel approach that uses depth maps and a fine-tuned multi-modal large language model (MLLM) to achieve high-fidelity image compositions, considering occlusion and complex spatial relationships. This significantly advances the field of generative image compositing and opens new avenues for research on 3D-aware image manipulation and generation.

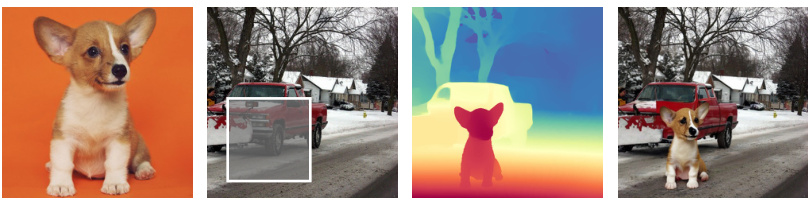

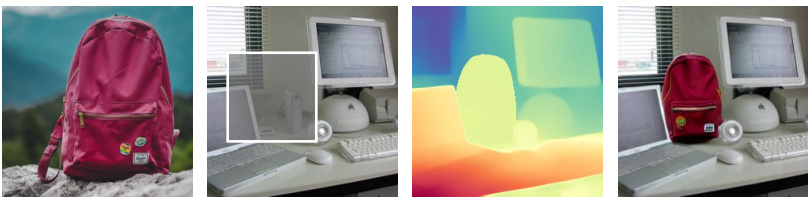

Visual Insights#

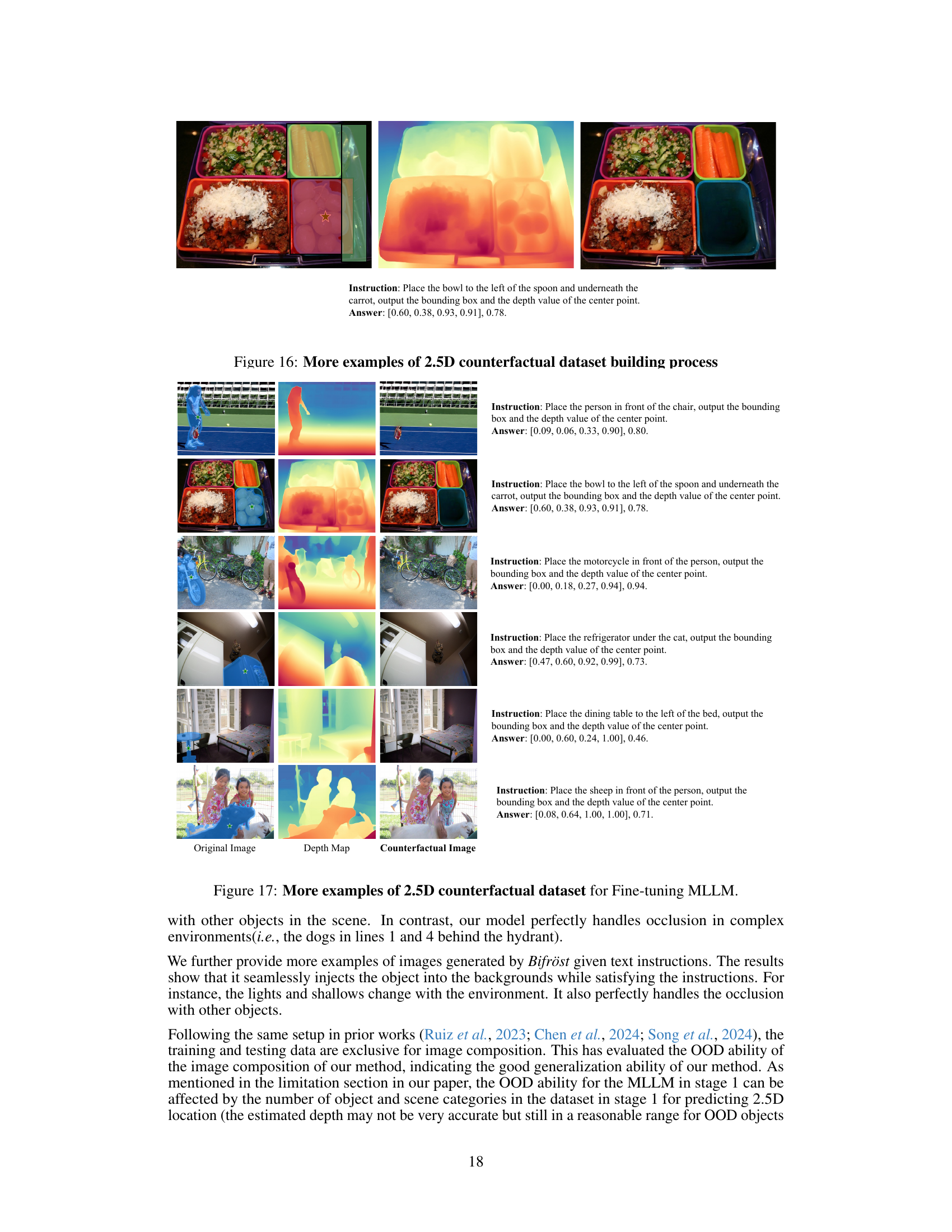

This figure showcases the capabilities of the Bifröst model in various image compositing tasks. The top row demonstrates precise object placement and replacement based on language instructions, considering 3D aspects like occlusion and depth. The bottom left shows the model’s ability to modify object poses according to a given mask, and the bottom right illustrates identity transfer while maintaining original pose.

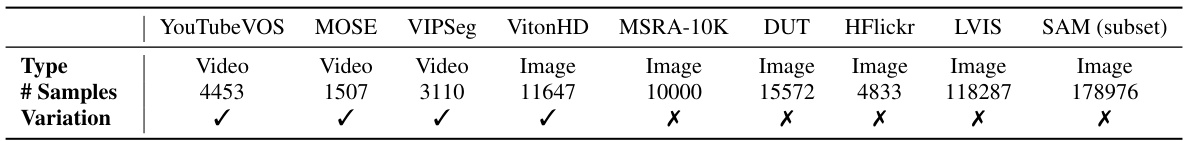

This table lists the datasets used in the image compositing stage of the Bifröst model. It shows the type of data (video or image), the number of samples in each dataset, and whether the dataset contains variations in pose or viewpoint of the objects. This is important because the model needs to learn how to generate images with different object poses and views to create high-fidelity compositions.

In-depth insights#

3D-Aware Composition#

3D-aware image composition presents a significant advancement in image manipulation. The core challenge lies in accurately representing and integrating objects into a scene while realistically considering depth and occlusion. Unlike traditional 2D compositing methods, a 3D-aware approach leverages depth information to understand spatial relationships, enabling the generation of photorealistic images. This is achieved by incorporating depth maps, alongside other visual cues, to guide the composition process. By training models on datasets that incorporate depth information, the system learns to generate results which accurately represent object placement and interactions with the background, including realistic shadowing and occlusion. The inclusion of depth maps as a key input significantly enhances the model’s ability to handle complex scenes and overcome the limitations of 2D methods. However, challenges remain, including the accurate estimation of depth from single images, and the computational cost associated with 3D modeling. Future research may focus on incorporating more sophisticated 3D representations and exploring techniques for efficient 3D-aware image manipulation.

MLLM Finetuning#

Fine-tuning a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) is crucial for achieving high-quality image composition based on language instructions. This process involves adapting a pre-trained MLLM to specifically predict 2.5D object locations within complex scenes. Key to this is a custom counterfactual dataset, generated to overcome the limitations of existing datasets. The dataset contains images with objects removed, paired with language instructions describing the object’s desired position and depth. This allows the MLLM to learn intricate spatial relationships and 3D context, which traditional 2D-centric models struggle with. The process of fine-tuning likely involves techniques like low-rank adaptation (LoRA), minimizing the negative log-likelihood of generated text tokens, and carefully balancing the preservation of object identity and harmonization within the background image. The resulting fine-tuned MLLM serves as a robust predictor of 2.5D locations, bridging the gap between 2D image data and 3D spatial understanding necessary for realistic image generation.

Depth Map Fusion#

Depth map fusion, in the context of image compositing, is a crucial technique for achieving realism. It involves integrating the depth information of the object being composited with the depth of the background scene. This process is essential for correctly handling occlusions, perspective distortions, and depth-of-field effects, as it allows the algorithm to understand the three-dimensional spatial relationships between elements. Accurate depth map fusion ensures that the composited object appears naturally embedded within the scene, rather than simply superimposed on top. The success of depth map fusion hinges on several factors: the quality of the individual depth maps (which may be estimated or provided as input); the technique used to combine the maps (e.g., weighted averaging, interpolation); and any post-processing steps (e.g., blur or refinement) applied to address artifacts or inconsistencies. A sophisticated depth map fusion method considers various factors to ensure visual coherence. These may include differences in depth map resolution or scale, potential inaccuracies in depth estimations, and the need to preserve fine details at the boundaries of the composited object to avoid visual seams or discontinuities. Robust handling of depth discontinuities and the creation of smooth transitions is vital for achieving photorealistic results. Advanced methods often leverage techniques such as edge-aware blending to integrate the depth maps seamlessly. The result of effective depth map fusion is a realistically integrated image with natural-looking depth, lighting, and shadows.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for 3D-aware image compositing models like Bifröst should prioritize handling more complex scenes and object interactions accurately. Addressing occlusion and depth inconsistencies, especially in out-of-distribution scenarios, is critical. Improved understanding of spatial relationships, potentially through advancements in 3D scene representation and reasoning, would greatly enhance performance. Fine-tuning with larger, more diverse datasets is essential to improve generalization across various backgrounds and object types. Exploring alternative training paradigms to better balance identity preservation and background harmonization would be beneficial. Finally, investigating the use of different diffusion model architectures or incorporating alternative generative methods may offer significant improvements in quality, efficiency, and controllability. The ethical implications of improved image manipulation capabilities also warrant further investigation and proactive safeguards.

Method Limitations#

A thorough analysis of limitations within a research paper’s methodology section requires a multifaceted approach. It’s crucial to consider the scope of the methods used, acknowledging their inherent constraints and potential biases. For instance, reliance on specific datasets might limit generalizability to other contexts. Assumptions made during method development should be explicitly stated and their implications carefully examined. Are there underlying assumptions about data distributions or model behavior that could affect the validity of results? Furthermore, the feasibility of replication needs critical evaluation. Are all parameters and steps clearly defined, allowing independent researchers to reproduce the findings? The computational cost should be assessed; are the methods computationally expensive, potentially limiting broader adoption? Finally, potential ethical considerations raised by the methodology—such as bias in datasets or the potential for misuse of the results—must be transparently addressed. A comprehensive analysis will weigh these factors, presenting a balanced view of the strengths and limitations, ultimately strengthening the paper’s overall contribution and credibility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

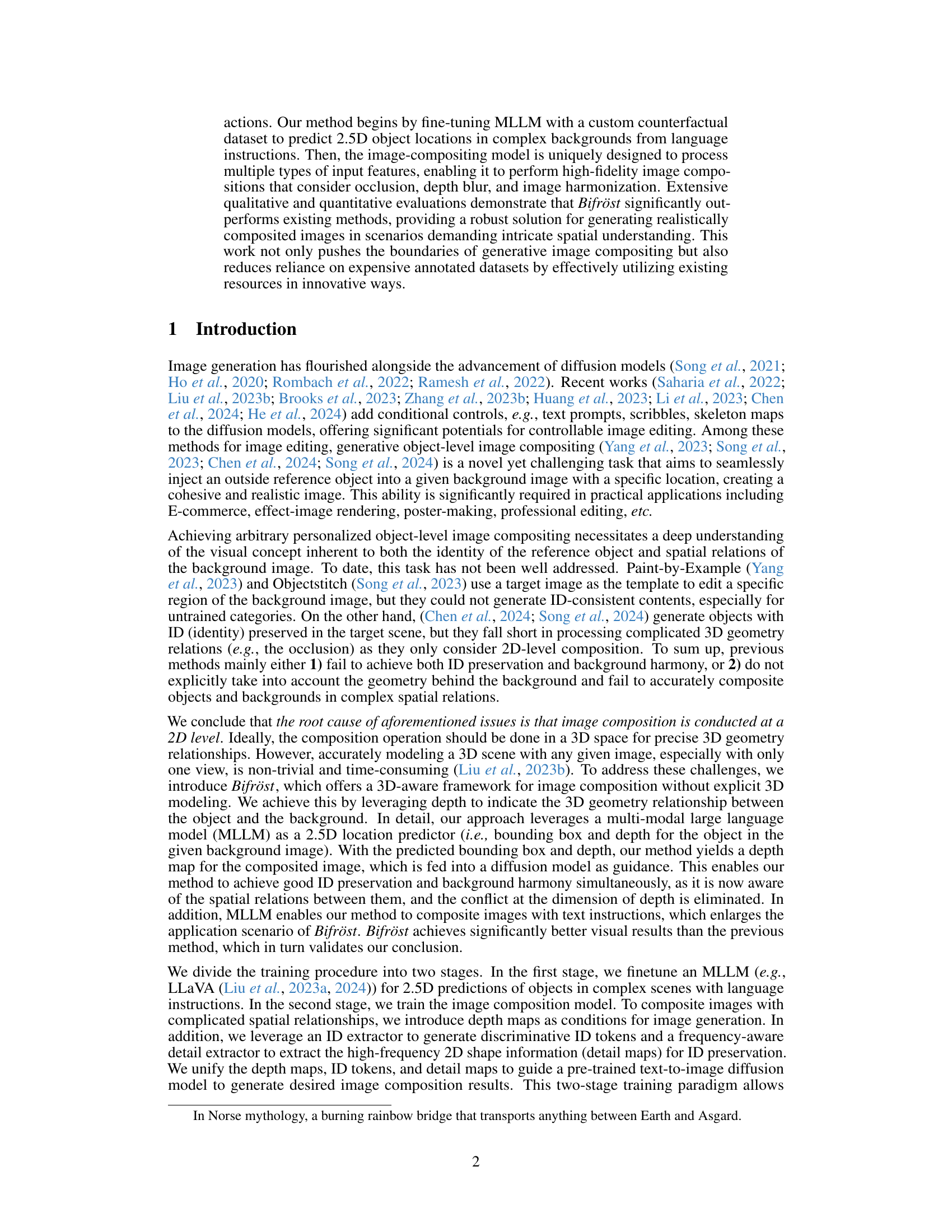

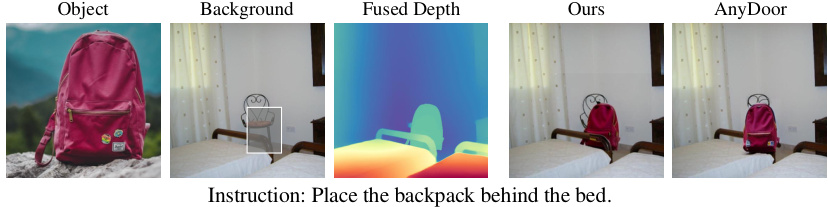

This figure illustrates the two-stage inference pipeline of the Bifröst model. Stage 1 involves using a Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM) to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of an object based on a background image and a text instruction. Stage 2 uses a depth predictor to estimate the depth of the background and reference object, fuses this depth information with the MLLM prediction, and feeds it to a diffusion model along with the masked background image and the reference object image to generate the final composited image. The process ensures that the final image respects the spatial relationships indicated in the text instruction and appears visually realistic.

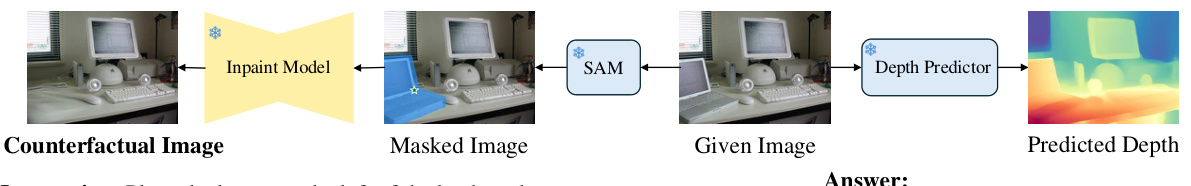

This figure illustrates the process of generating a counterfactual dataset for fine-tuning the Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM). It starts with a scene image, selects an object, predicts its depth using a depth predictor, masks and inpaints the object, and finally pairs the resulting counterfactual image with a text instruction and the object’s 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) as training data for the MLLM.

This figure illustrates the process of generating a counterfactual dataset used for fine-tuning the Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM). It shows how an object is selected, its depth predicted, and then removed from the original image using image inpainting techniques. The resulting image, along with a textual instruction about the object’s location, forms a data point for training the MLLM to predict 2.5D object locations.

This figure illustrates the training pipeline of the 3D-aware image compositing module in Bifröst. It shows how the model uses segmentation, ID extraction, depth prediction, and detail extraction to generate a high-fidelity composite image that respects spatial relationships and depth cues.

This figure illustrates the process of creating training data from video clips for the image compositing model. Two frames are selected from a video clip. One frame provides the reference object and the other frame serves as the background image. The corresponding instance (the same object) is identified in both frames. The object from one frame is used as the reference image, while the other frame, after masking the object, forms the target background image. This method leverages the temporal consistency in videos to generate training pairs with varied poses and views of the object within a similar context.

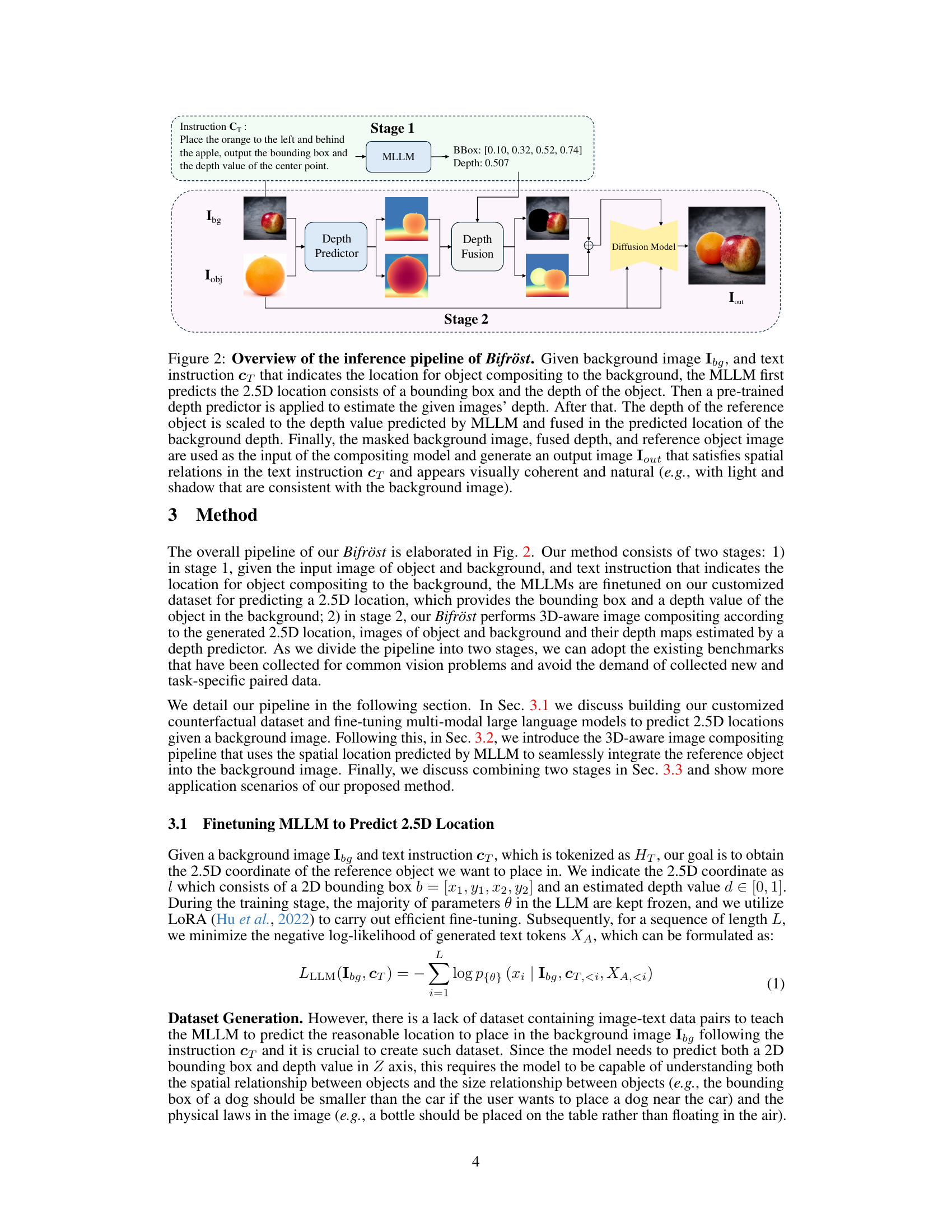

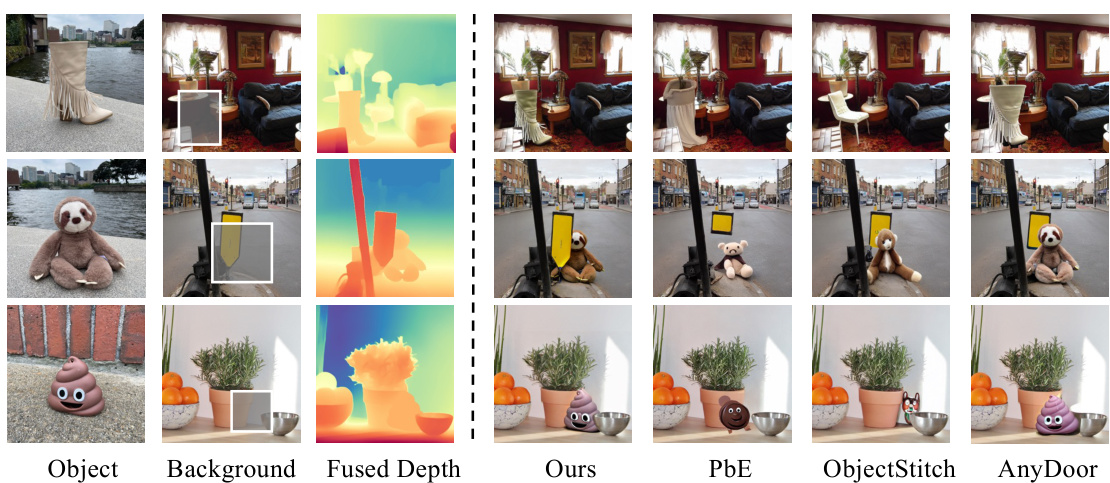

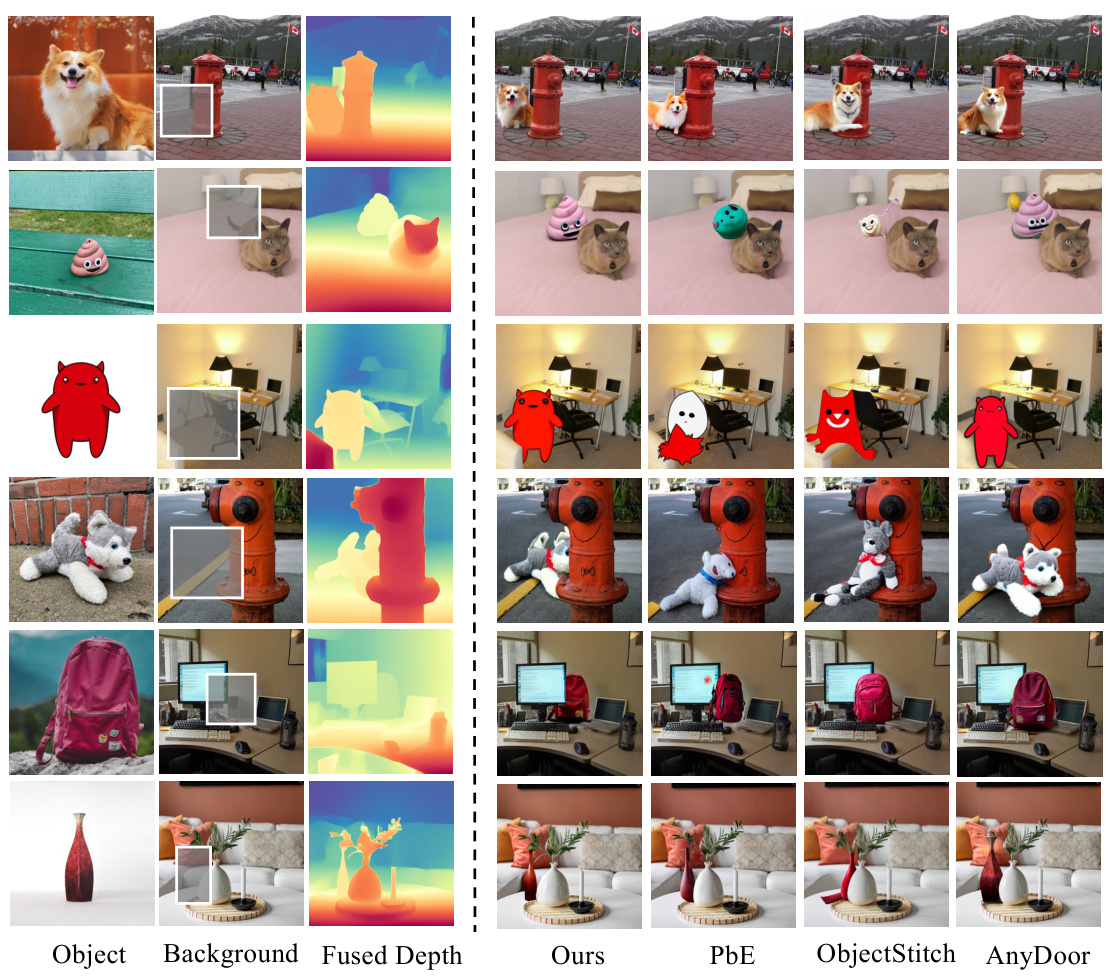

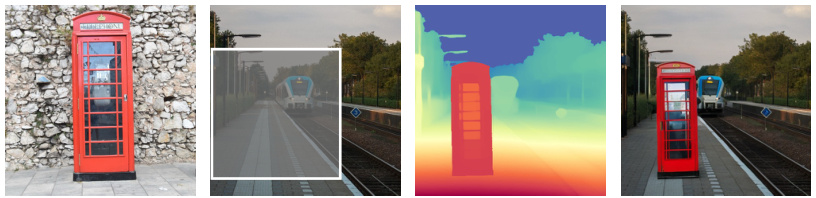

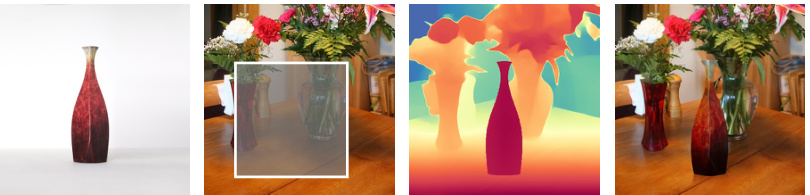

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of Bifrost with three other methods for image generation: Paint-by-Example, ObjectStitch, and AnyDoor. The comparison highlights Bifrost’s superior ability to maintain geometric consistency when compositing images. It’s important to note that none of the methods were fine-tuned on the test set used for this comparison.

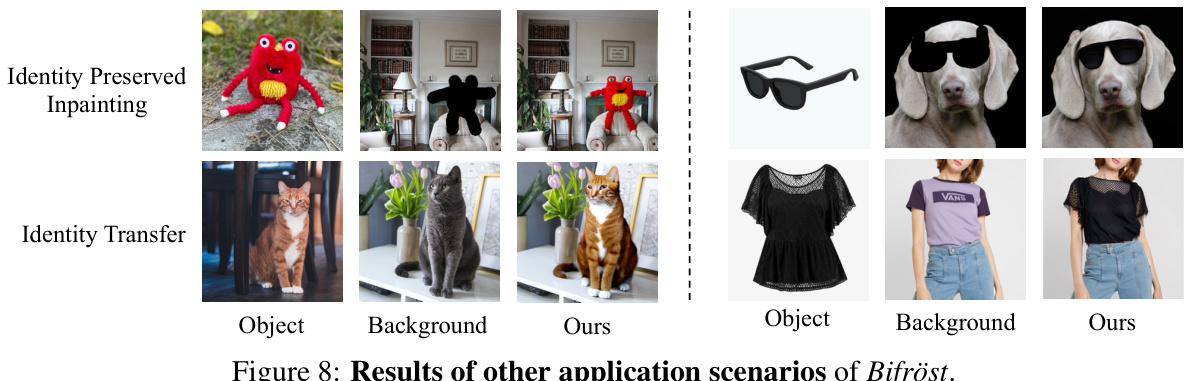

This figure shows the results of Bifröst on various personalized image compositing tasks beyond object placement and replacement. It demonstrates the model’s capabilities in identity-preserved inpainting (changing the object’s pose while maintaining its identity), identity transfer (adapting the reference image’s identity to match that of the target image while keeping the pose), and more complex scenarios.

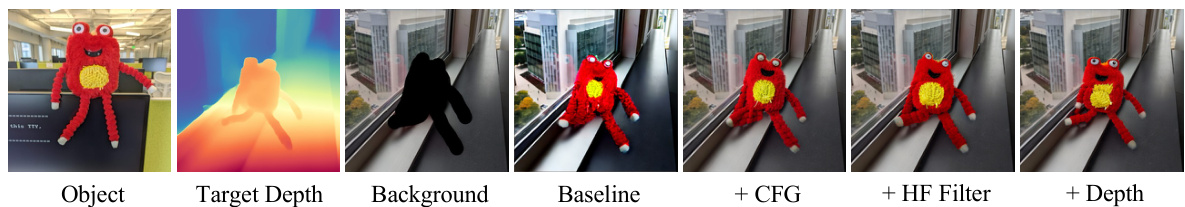

This figure shows an ablation study on the core components of the Bifröst model. It demonstrates the effect of each component on the final image generation quality. The figure shows a series of images, each representing a stage in the generation process: starting with a baseline model, and then adding classifier-free guidance (+ CFG), a high-frequency filter (+ HF filter), and finally depth information (+ Depth). The last image showcases the result of the full Bifröst model. The comparison highlights the contribution of each component to improved visual quality and realism.

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the impact of different depth control levels in the image compositing model. It demonstrates how changing the depth value affects the final generated image, specifically regarding the positioning and visual realism of the inserted object relative to the background. The study varies the depth value from deep (0.35) to shallow (0.80), showing a corresponding shift in the object’s position within the scene.

This figure compares the visual results of Bifrost against three other methods for image generation: Paint-by-Example, ObjectStitch, and AnyDoor. It highlights that Bifröst better maintains geometric consistency when compositing objects into background images. Importantly, none of the compared methods were fine-tuned on the test data.

This figure shows the distribution of differences between the depth value at the center of a bounding box and three other ways of calculating the depth value (maximum, mean, and median). The purpose is to determine the best way to represent the 2.5D location of an object for the image compositing task. The results show that using the center point depth is reasonable, with most of the differences between it and other depth values being small. Using the mean value is also reasonable, while the median value is shown to not be reliable.

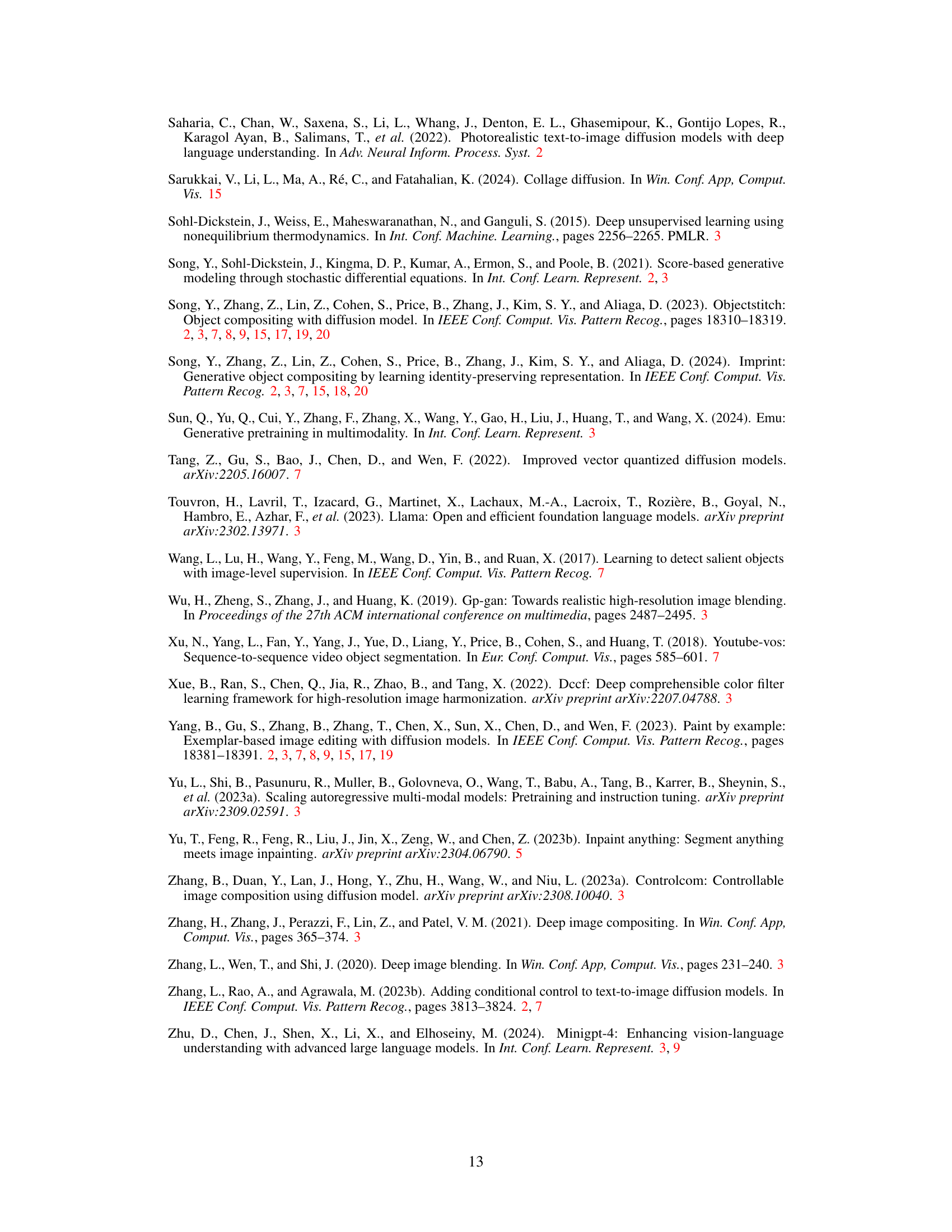

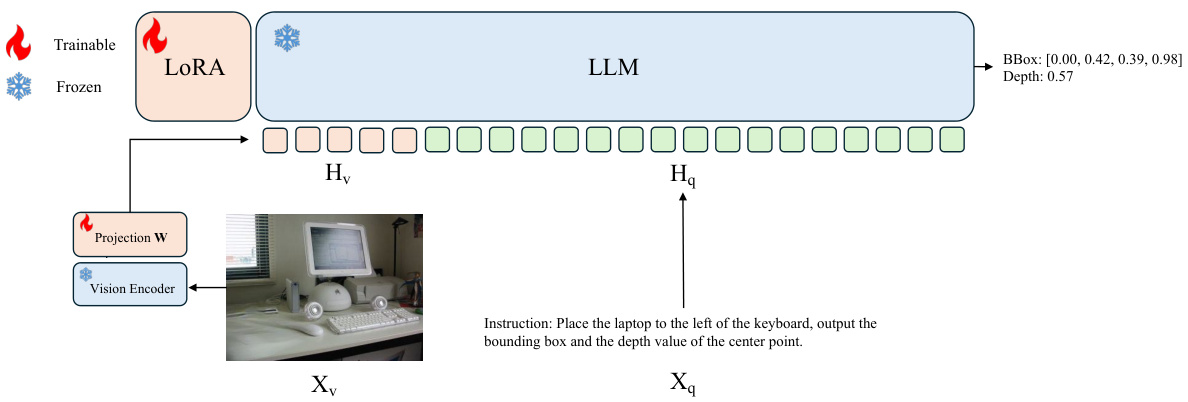

The figure shows the architecture of the MLLM fine-tuning process. It takes an image (Xv) as input, which is processed by a vision encoder. The output of the vision encoder (Hv) is then combined with the text instruction (Hт) and fed into the LLM. The LLM then produces the bounding box and depth value (Xq). The process uses a LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) approach where only a subset of parameters in the LLM are updated during fine-tuning, making the process more efficient. The figure also displays the instruction used as an example.

This figure shows different mask types used in the image compositing stage of the Bifröst model. The masks vary in complexity, from a simple bounding box (Mask 1) to more detailed shapes (Masks 2-5) that progressively constrain the generated image to fit more closely within the mask’s shape and position. This allows users to control the generated object’s pose and shape by defining the desired region.

The figure illustrates the inference pipeline of the proposed method, Bifröst. It shows how a background image, text instruction, and reference object are processed in two stages. Stage 1 uses a multi-modal large language model (MLLM) to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of where the object should be placed. Stage 2 uses a depth predictor to estimate depths and fuses this information with the masked background and object image. Finally, a diffusion model generates the composited image.

This figure illustrates the two-stage inference pipeline of the Bifrost model. Stage 1 uses a Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM) to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of an object within a background image based on a textual instruction. Stage 2 leverages a depth predictor to fuse the predicted depth with the background image depth and then uses this information, along with the object and background images, to perform 3D-aware image compositing via a diffusion model, resulting in a final image that accurately reflects the spatial relationships described in the instruction.

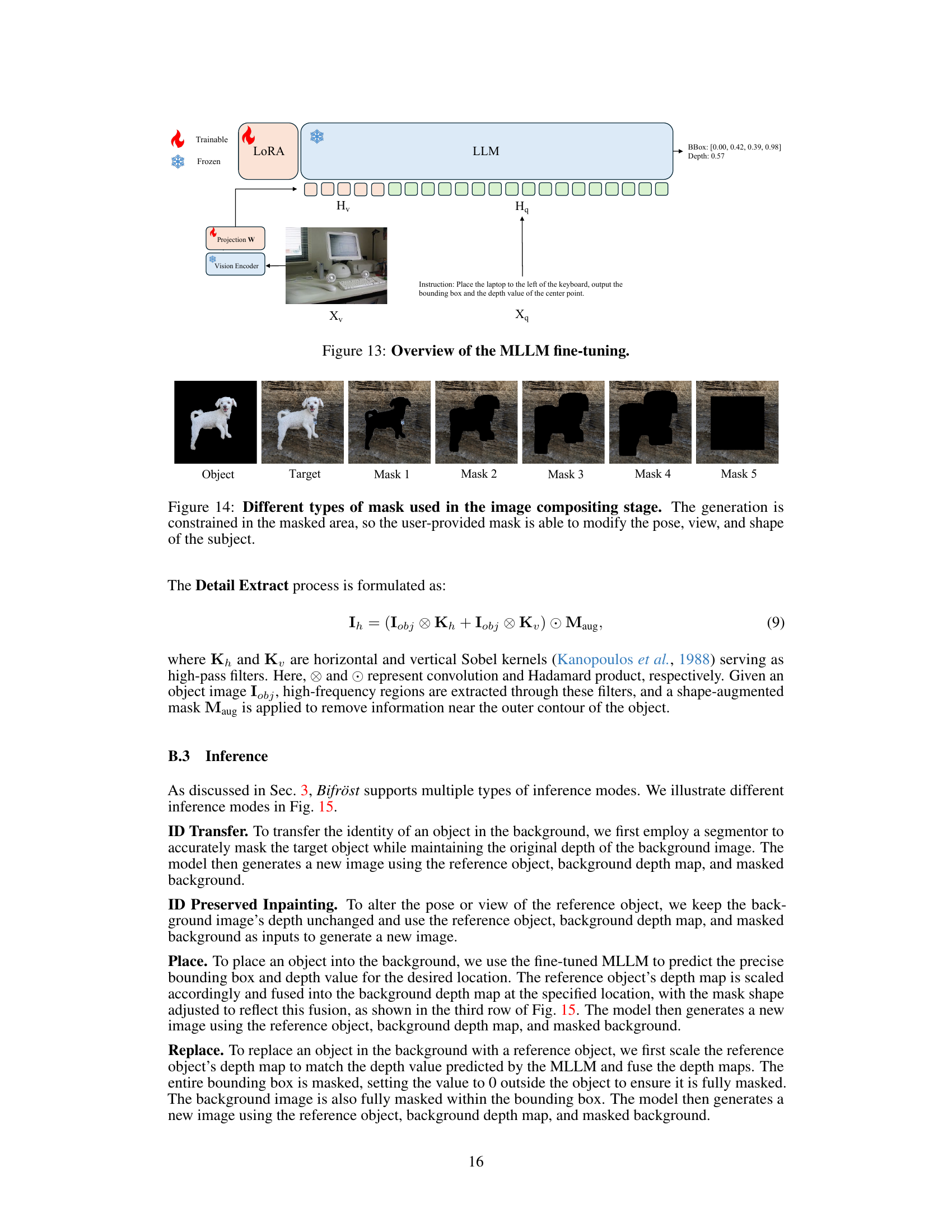

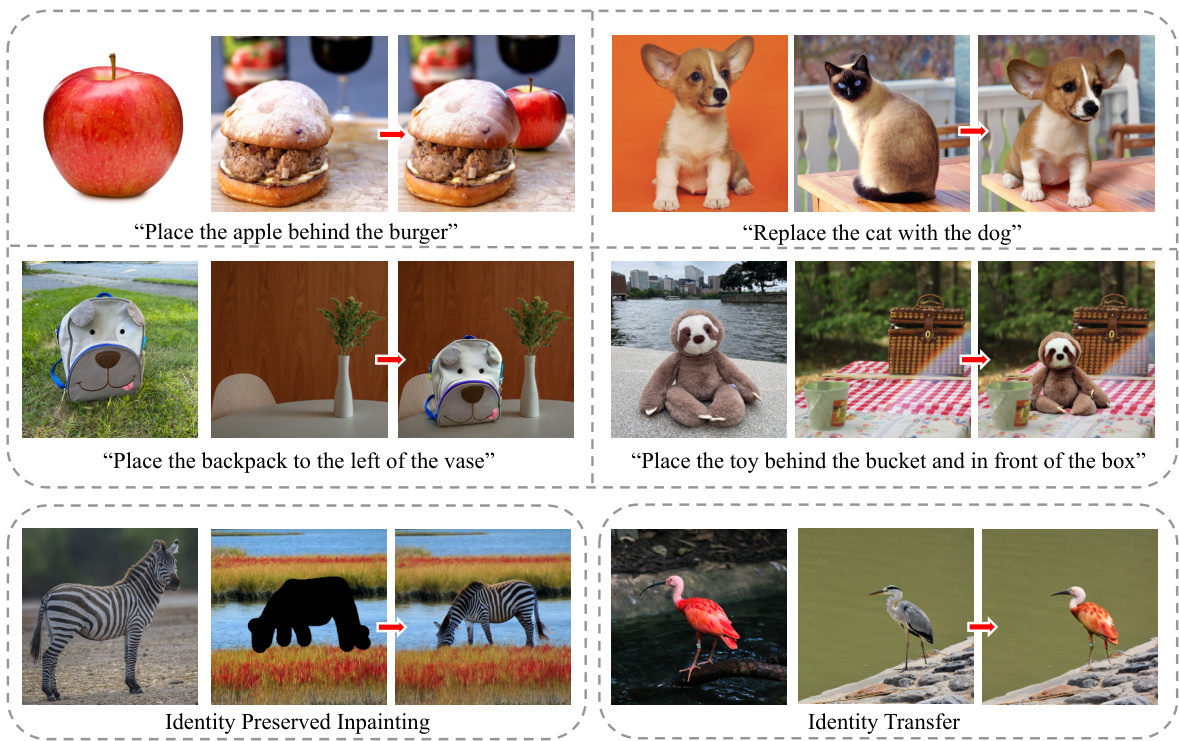

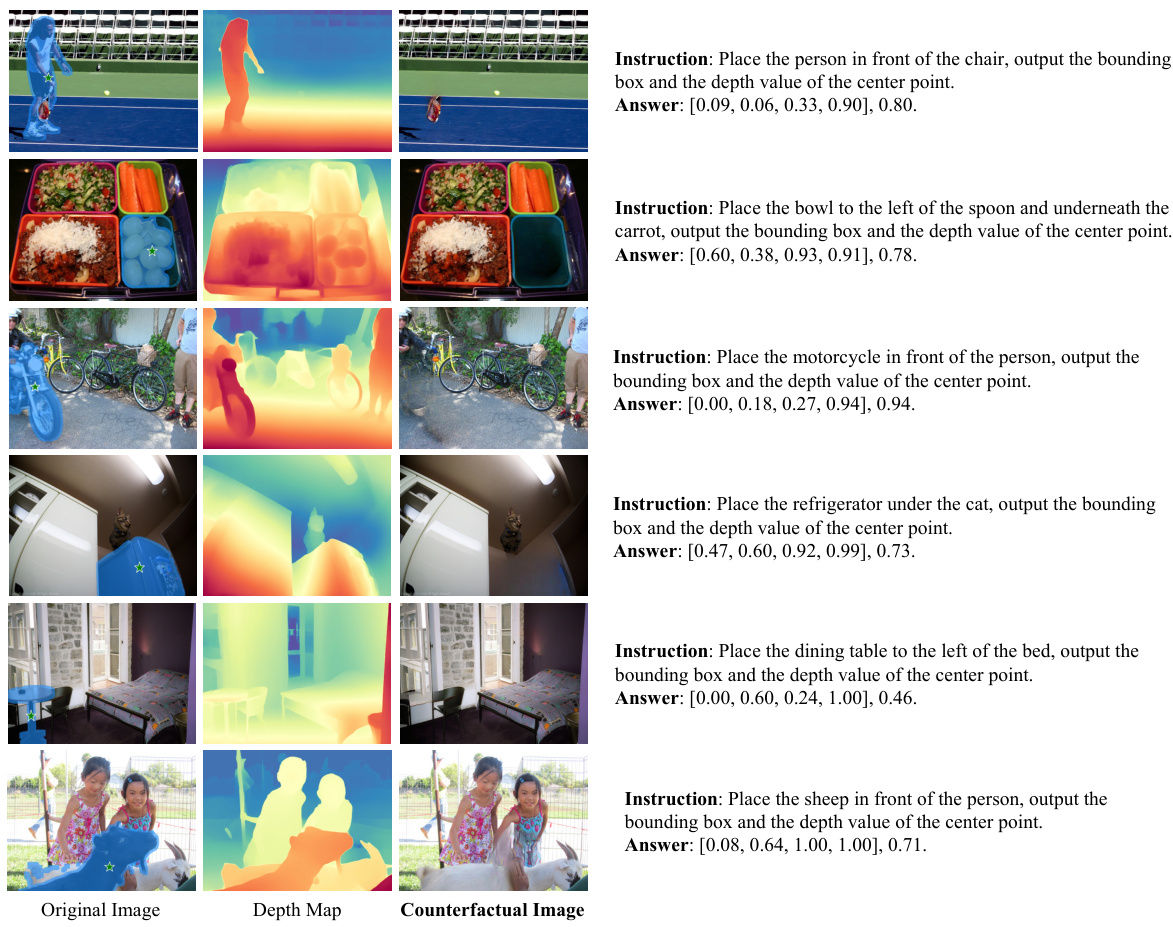

This figure shows more examples of the 2.5D counterfactual dataset used for fine-tuning the multi-modal large language model (MLLM). Each example includes an original image, its corresponding depth map, and a counterfactual image where the target object has been removed. The instruction given to the MLLM for each example is also provided along with the predicted bounding box and depth value for the target object, demonstrating the model’s ability to predict the 2.5D location of an object within a complex scene based on textual instructions.

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of Bifröst against three other image generation methods: Paint-by-Example, ObjectStitch, and AnyDoor. The comparison highlights Bifröst’s superior ability to maintain geometric consistency when compositing images. Each row shows a different example, demonstrating how Bifröst achieves better visual harmony and accuracy in object placement and background integration compared to the alternative methods. Notably, all methods used in the comparison did not fine-tune their models on the test samples.

This figure shows two examples where both the object and the background image are from the out-of-distribution dataset. The model successfully composited the dog to the right of the piano and the horse in front of the church, demonstrating its ability to generalize to unseen objects and scenes.

The figure illustrates the inference pipeline of the Bifröst model. First, a multi-modal large language model (MLLM) predicts the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of the object to be composited. A depth predictor then estimates the depth of the background and object. The object’s depth is scaled and fused with the background depth. Finally, the masked background, fused depth map, and reference object image are fed into a diffusion model to generate the final composited image.

This figure illustrates the two-stage inference process of the Bifrost model. Stage 1 involves using a Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM) to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of an object within a background image based on a text instruction. Stage 2 uses this information, along with a depth map of the background image and the reference object image, to generate the final composite image using a diffusion model. The process ensures that the composite image accurately reflects the spatial relationships specified in the text instruction while maintaining visual coherence.

This figure showcases the capabilities of the Bifröst model in three personalized image compositing tasks. The top row demonstrates precise object placement and replacement guided by language instructions, achieving realistic results with accurate occlusion and lighting. The bottom left shows how Bifröst changes the object’s pose to match a provided mask. Finally, the bottom right illustrates the model’s ability to adapt the object’s identity to the target image while maintaining its original pose.

This figure illustrates the inference stages of the Bifröst model. First, a multi-modal large language model (MLLM) takes the background image and text instruction as input to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of the object to be added. Then, a depth predictor estimates the depth of the background and object. The object’s depth is adjusted based on the MLLM’s prediction and fused with the background depth map. Finally, a diffusion model generates the composited image using the masked background, fused depth map, and the object image. The resulting image accurately reflects the spatial relationships specified in the text instruction and maintains visual coherence.

The figure illustrates the two-stage inference process of Bifrost. First, a Multi-modal Large Language Model (MLLM) predicts the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of the object to be composited. Then, a diffusion model uses the predicted depth, reference object image, and masked background image to generate the final composited image.

This figure showcases the capabilities of the Bifröst model in performing personalized image compositing tasks using language instructions. The top row demonstrates precise object placement and replacement, considering 3D spatial relationships and achieving high-fidelity results. The bottom left shows how Bifröst can change object poses according to a given mask. The bottom right illustrates how Bifröst can adapt the identity of the reference object to the target image.

This figure illustrates the training pipeline of the 3D-aware image compositing module in Bifröst. It details the process of using a segmentation module to extract the object from the background, employing ID and detail extractors to capture identity and texture information, and leveraging a depth predictor to estimate depth for spatial relationships. These features are then integrated into a diffusion model to generate a composited image.

This figure illustrates the two-stage inference pipeline of the Bifröst model. Stage 1 uses a multi-modal large language model (MLLM) to predict the 2.5D location (bounding box and depth) of an object to be composited into a background image based on a text instruction. Stage 2 uses a depth predictor to estimate depth maps for both the object and background, fuses them, and then uses a diffusion model to generate the final composited image while considering depth and spatial relationships.

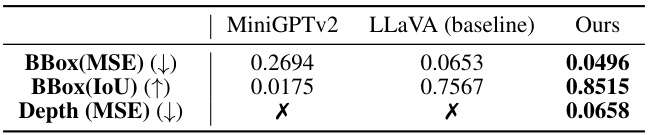

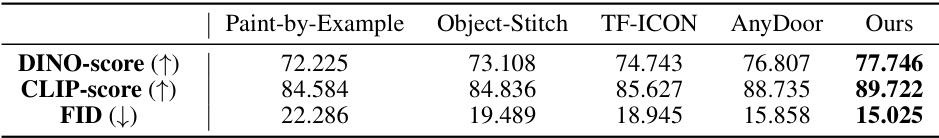

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the accuracy of the proposed method’s multi-modal large language model (MLLM) in predicting the 2.5D location of objects for image composition. It compares the performance of Bifröst against two baseline models, MiniGPTv2 and LLaVA, using Mean Squared Error (MSE) for bounding box (BBox) prediction and Intersection over Union (IoU) for bounding box accuracy. Notably, Bifröst is the only model that predicts depth, with the accuracy measured using MSE.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of Bifröst’s image compositing performance against several other state-of-the-art methods. Three metrics are used for evaluation: DINO-score (higher is better), CLIP-score (higher is better), and FID (Fréchet Inception Distance, lower is better). The results demonstrate that Bifröst significantly outperforms all other methods across all three metrics, indicating its superior performance in generating high-fidelity and realistic composited images.

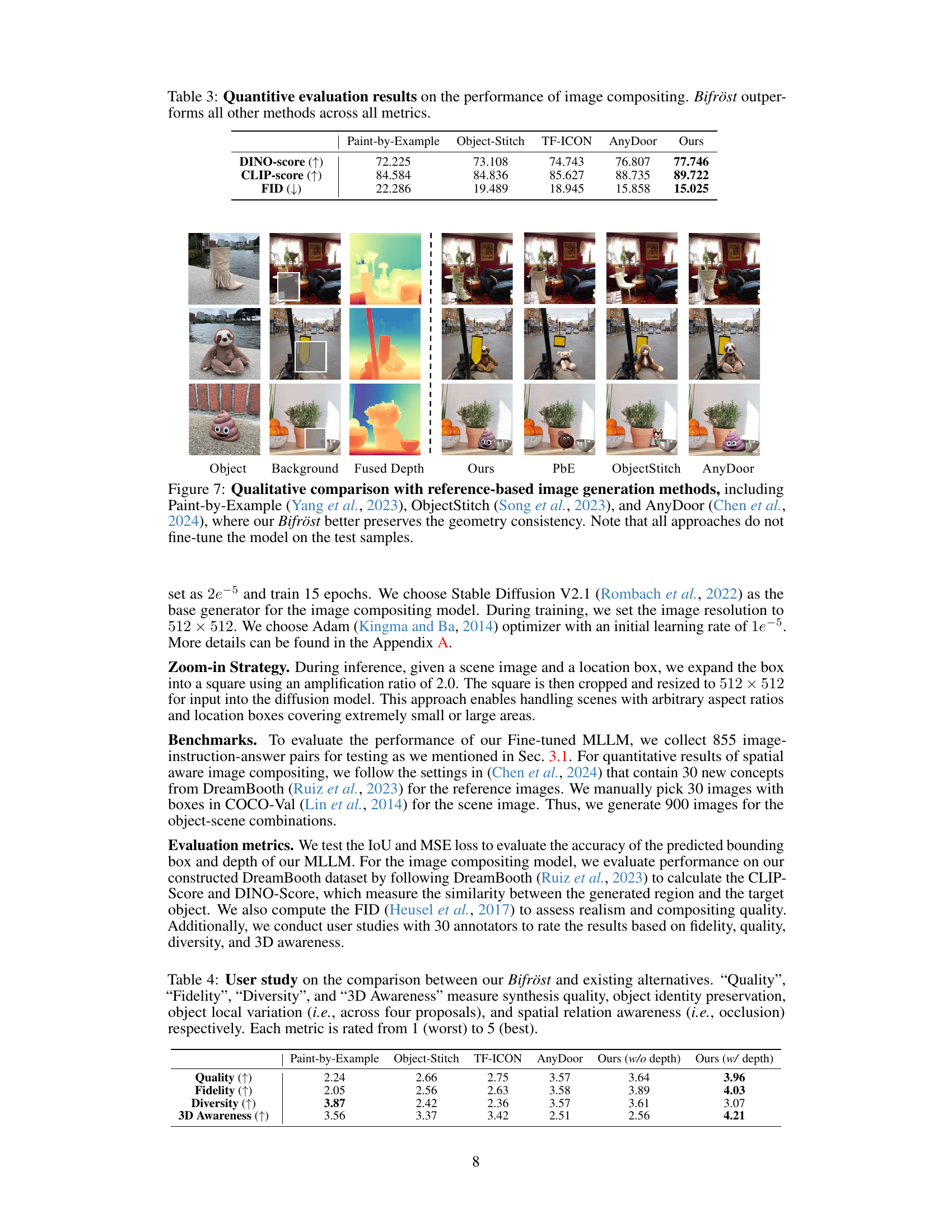

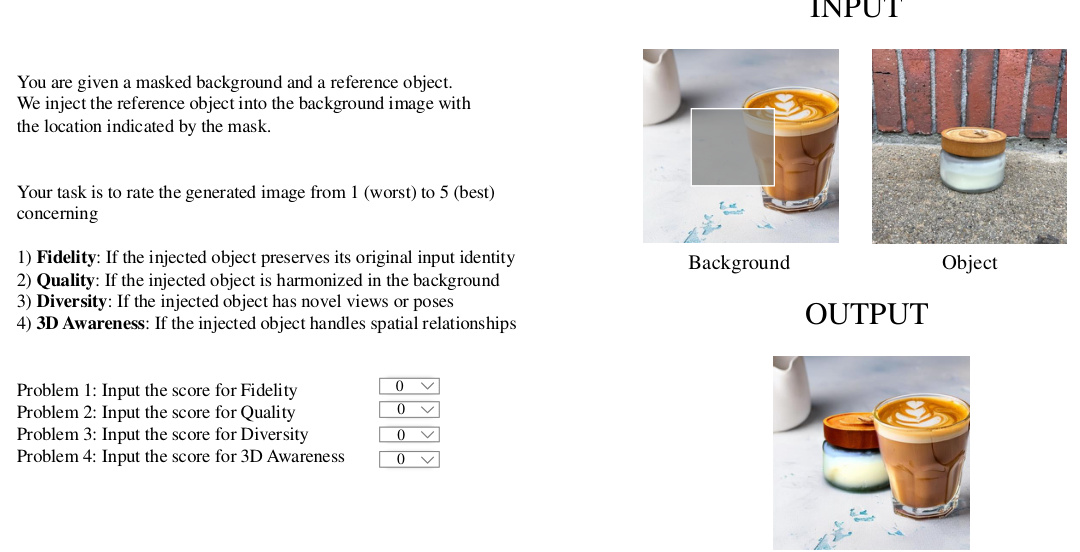

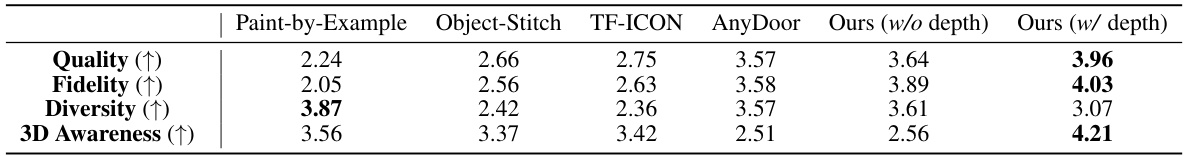

This table presents the results of a user study comparing Bifröst with four other image compositing methods. Users rated the generated images on four criteria: Quality (overall visual quality), Fidelity (how well the generated object matched the reference), Diversity (variation in generated poses), and 3D Awareness (handling of spatial relationships, including occlusion). Higher scores indicate better performance.

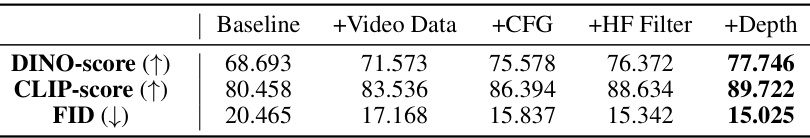

This table presents the quantitative ablation study results for the core components of the Bifröst image compositing model. It shows the impact of adding video data, classifier-free guidance (CFG), high-frequency filter (HF Filter), and depth information to the baseline model. The metrics used are DINO-score (higher is better), CLIP-score (higher is better), and FID (lower is better). The results demonstrate the incremental improvements in performance when these components are added sequentially.

Full paper#