TL;DR#

Many imitation learning algorithms rely on inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) to infer reward functions from expert demonstrations. However, these inferred reward functions often fail to capture the true task objective, leading to suboptimal policies. This paper addresses the critical issue of task-reward misalignment by introducing a novel framework that emphasizes task alignment over conventional data alignment.

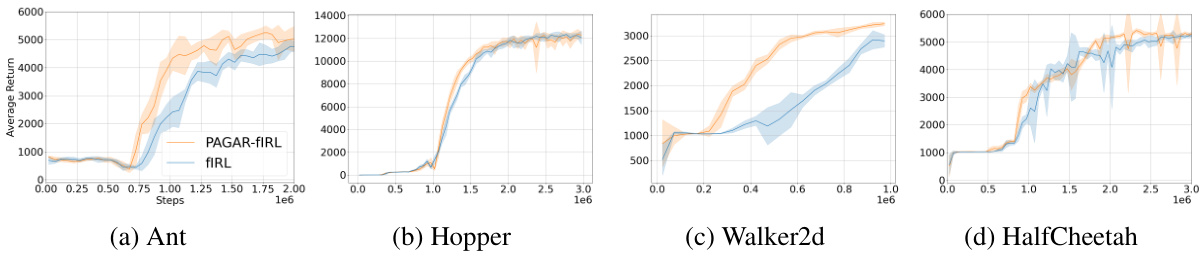

The proposed framework, called PAGAR (Protagonist Antagonist Guided Adversarial Reward), is a semi-supervised approach. It uses expert demonstrations as weak supervision signals to identify a set of candidate reward functions that align with the intended task. An adversarial training mechanism is employed to validate the learned policy’s ability to achieve the task across these diverse reward functions, improving robustness. Experimental results demonstrate that PAGAR outperforms existing methods in complex scenarios and transfer learning, showcasing its effectiveness in addressing the critical challenge of task-reward misalignment.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in imitation learning and reinforcement learning because it directly addresses the prevalent issue of task-reward misalignment in IRL-based methods. By introducing the novel concept of task alignment and proposing a practical algorithm (PAGAR) to improve task alignment, it opens up new avenues for research in developing more robust and effective imitation learning algorithms. The findings offer valuable insights into enhancing the performance and generalization capabilities of AI agents trained through imitation.

Visual Insights#

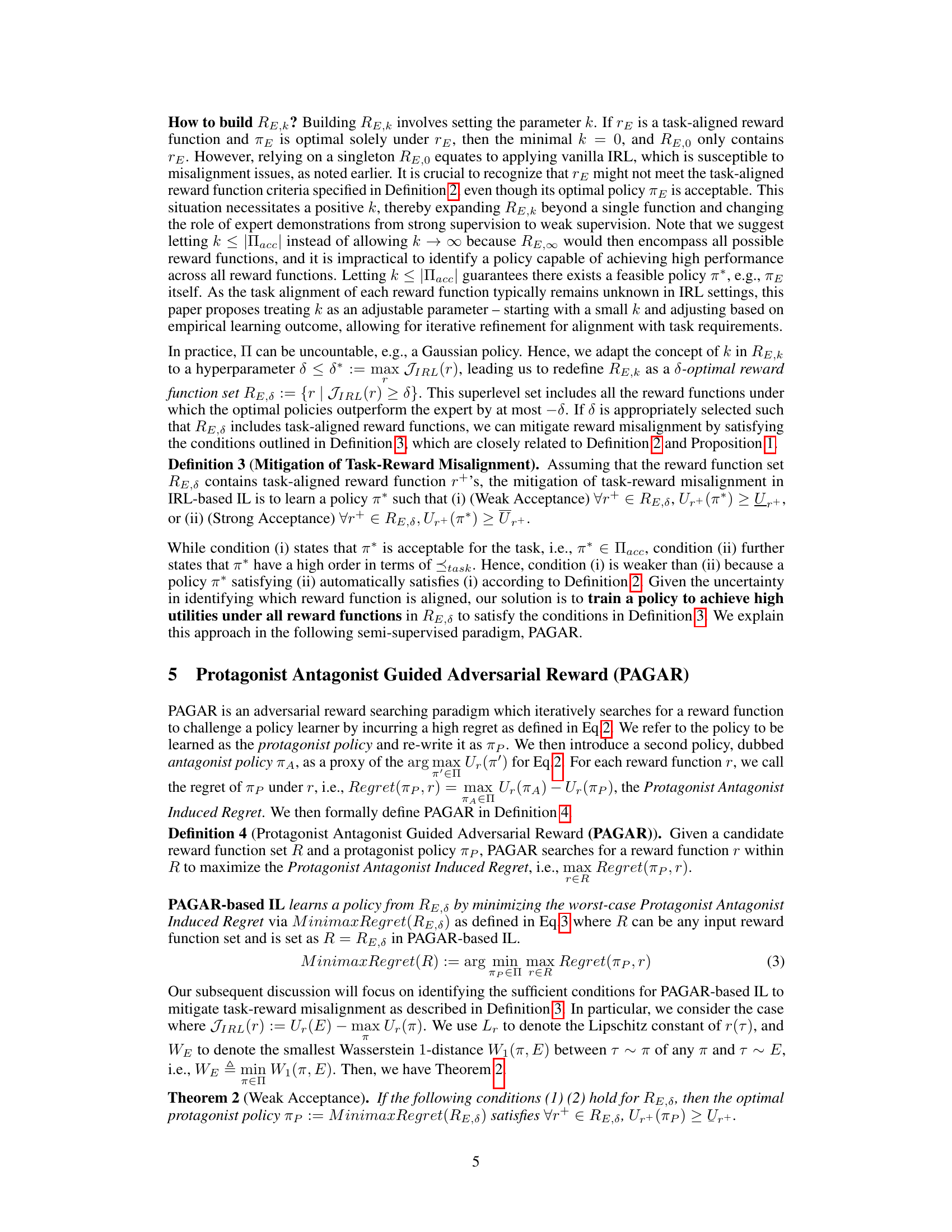

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concept of the paper, comparing conventional IRL-based imitation learning with the proposed PAGAR method. (a) shows how task-aligned reward functions (r+) clearly separate acceptable policies from unacceptable ones in their utility space, while misaligned ones (r-) do not. (b) highlights PAGAR’s advantage by learning from multiple candidate reward functions to arrive at an acceptable policy.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) The two bars respectively represent the policy utility spaces of a task-aligned reward function r+ and a task-misaligned reward function r¯. The white color indicates the utilities of acceptable policies, and the blue color indicates the unacceptable ones. Within the utility space of r⁺, the utilities of all acceptable policies are higher (> U+) than those of the unacceptable ones, and the policies with utilities higher than Ur+ have higher orders than those of utilities lower than Ur+. Within the utility space of r¯, acceptable and unacceptable policies' utilities are mixed together, leading to a low U,- and an even lower Ū- . (b) IRL-based IL relies solely on IRL's optimal reward function r* which can be task-misaligned and lead to an unacceptable policy πρ* ∈ Π acc while PAGAR-based IL learns an acceptable policy π* ∈ Πacc from a set RE,8 of reward functions.

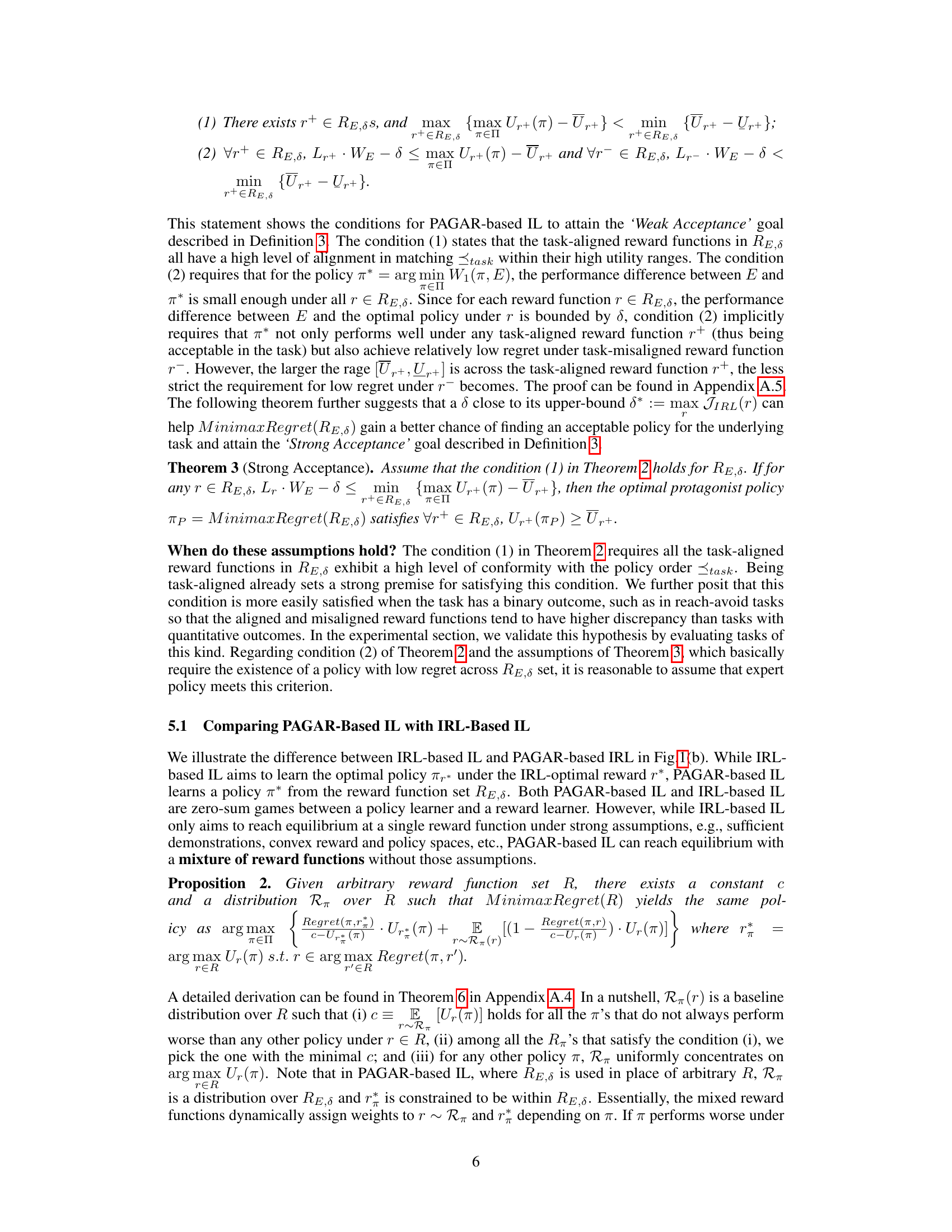

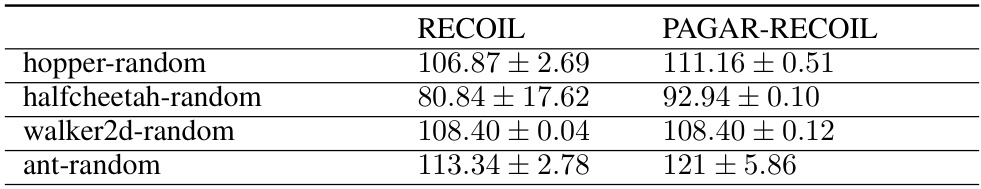

🔼 This table presents the average performance results of offline reinforcement learning experiments using two different methods: RECOIL and PAGAR-RECOIL. The results are shown for four different continuous control tasks from the MuJoCo environment. Each result represents the average performance across four independent experimental runs (seeds), providing a measure of the methods’ reliability and stability. PAGAR-RECOIL consistently shows comparable or better performance compared to RECOIL across all tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline RL results obtained by combining PAGAR with RECOIL averaged over 4 seeds.

In-depth insights#

Task-Reward Alignment#

The concept of ‘Task-Reward Alignment’ tackles the core challenge in inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) where the learned reward function might not accurately reflect the true task objective. The paper shifts focus from data alignment (matching expert demonstrations) to task alignment (achieving the underlying task goal). This highlights a crucial distinction: a reward function might perfectly represent the data but fail to capture the essence of the task, potentially leading to suboptimal policies. The authors propose that expert demonstrations should act as weak supervision signals to identify candidate reward functions. This approach acknowledges the inherent ambiguity in IRL, proposing a collective validation of policy effectiveness across multiple reward functions rather than relying on a single, potentially misaligned, reward. By prioritizing task success over perfect data representation, the framework aims to enhance the robustness and generalizability of IRL-based imitation learning methods. The adversarial training approach further strengthens the learned policy, fostering performance in complex and transfer learning scenarios.

PAGAR Framework#

The PAGAR framework offers a novel semi-supervised approach to inverse reinforcement learning (IRL), prioritizing task alignment over data alignment. It leverages expert demonstrations as weak supervision to identify a set of candidate reward functions, moving beyond the limitations of single-reward methods. An adversarial training mechanism enhances robustness, with a protagonist policy pitted against an antagonist reward searcher, iteratively refining the policy’s performance across multiple reward functions. This collective validation of the policy’s task-accomplishment ability is a key strength, mitigating the risks of task-reward misalignment prevalent in conventional IRL approaches. Theoretical insights support its capacity to handle complex scenarios and transfer learning, with experimental results showing improved performance over established baselines. PAGAR’s innovative approach promises to significantly improve the reliability and effectiveness of IRL-based imitation learning, particularly in scenarios with limited or imperfect data.

Adversarial Training#

Adversarial training, a core concept in robust machine learning, is a powerful technique to enhance model resilience against adversarial attacks. The fundamental principle involves training a model not just on clean data, but also on adversarially perturbed inputs. These perturbations, designed to fool the model, are often generated using optimization techniques, aiming to maximize the model’s error. By exposing the model to such attacks during training, it learns to develop more robust internal representations, which are less susceptible to these subtle manipulations. The effectiveness of this approach hinges on the careful design of the adversarial attacks. A balance between perturbation strength and data realism needs to be maintained to prevent overfitting or the generation of unrealistic samples. Another critical aspect lies in the choice of the loss function used during adversarial training. This aspect is frequently tailored to the specific task and the nature of the adversarial attacks employed. Adversarial training often improves a model’s generalization performance, leading to better robustness in real-world scenarios. However, this technique can be computationally expensive due to the repeated generation and evaluation of adversarial examples. Despite this computational cost, adversarial training remains a significant area of research with ongoing efforts focused on developing more efficient and effective training strategies, particularly in the context of deep learning models.

Empirical Evaluation#

A robust empirical evaluation section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should present results from multiple experiments, comparing the proposed method against strong baselines. Clear visualizations, such as graphs and tables, are essential for presenting the results concisely and effectively. The evaluation should cover a range of scenarios to demonstrate the generalizability and robustness of the method. Statistical significance should be carefully considered, and appropriate measures should be reported to ensure the reliability of the findings. Ablation studies help isolate the contribution of individual components, providing further insights into the model’s behavior and effectiveness. In addition to quantitative results, qualitative analyses may be beneficial. This is particularly true if the research involves subjective tasks where human judgment is needed. Finally, limitations of the evaluation should be openly addressed, contributing to the overall transparency and credibility of the research.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion mentions exploring the PAGAR paradigm for other task alignment problems as future work. This suggests a broad research direction, moving beyond the specific imitation learning scenarios examined in the current study. It would be beneficial to investigate the applicability of PAGAR to different reinforcement learning tasks, such as those involving more complex reward functions or scenarios with sparse rewards. Furthermore, exploring how PAGAR handles transfer learning across diverse environments is crucial. Theoretical analysis to further refine the framework and provide stronger guarantees on its performance is also warranted. Finally, investigating the scalability of PAGAR to high-dimensional problems and more complex reward structures would strengthen the impact and applicability of the proposed framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the difference between conventional IRL-based imitation learning and the proposed PAGAR-based approach. Panel (a) shows the policy utility spaces for task-aligned (r+) and misaligned (r-) reward functions. Task alignment means acceptable policies have higher utilities than unacceptable ones, and higher utility implies higher task performance. Panel (b) highlights that conventional IRL can yield unacceptable policies (πρ*) due to misaligned reward functions (r*), while PAGAR learns an acceptable policy (π*) by leveraging a set (RE,δ) of candidate reward functions.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) The two bars respectively represent the policy utility spaces of a task-aligned reward function r+ and a task-misaligned reward function r¯. The white color indicates the utilities of acceptable policies, and the blue color indicates the unacceptable ones. Within the utility space of r⁺, the utilities of all acceptable policies are higher (> U+) than those of the unacceptable ones, and the policies with utilities higher than Ur+ have higher orders than those of utilities lower than Ur+. Within the utility space of r¯, acceptable and unacceptable policies' utilities are mixed together, leading to a low U,- and an even lower Ū- . (b) IRL-based IL relies solely on IRL's optimal reward function r* which can be task-misaligned and lead to an unacceptable policy πρ* ∈ Π acc while PAGAR-based IL learns an acceptable policy π* ∈ Πacc from a set RE,8 of reward functions.

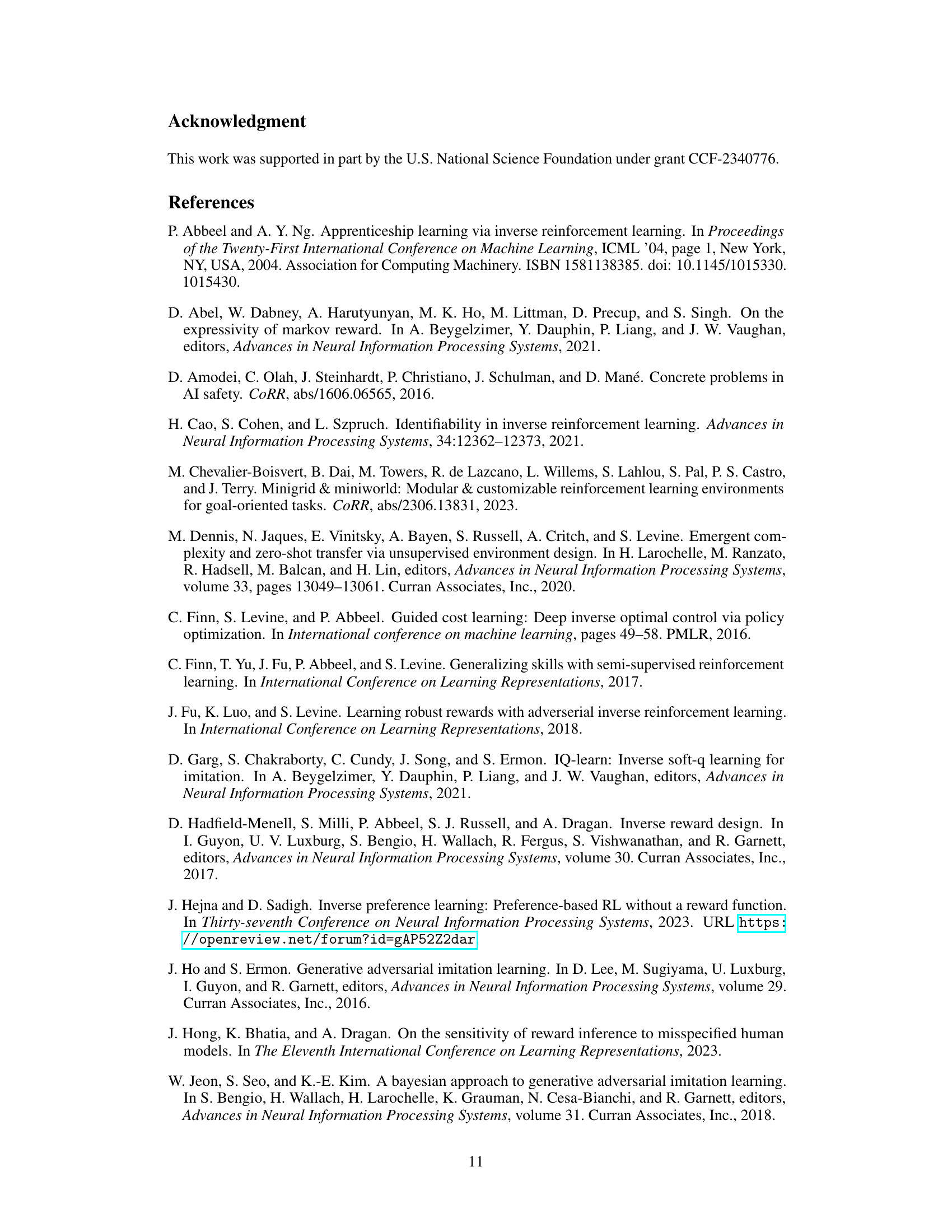

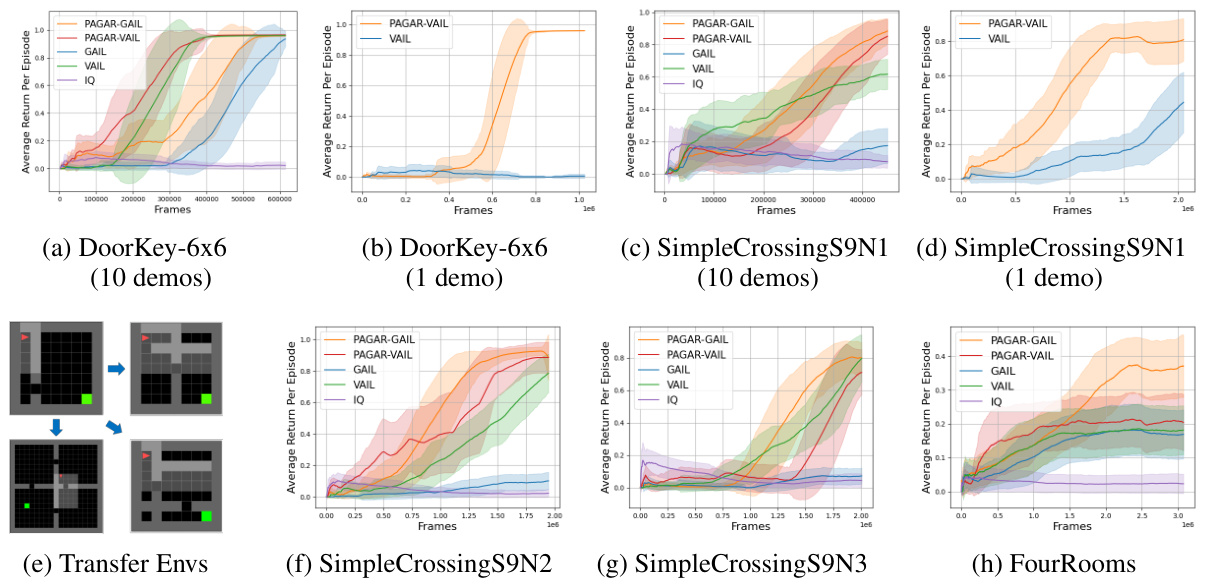

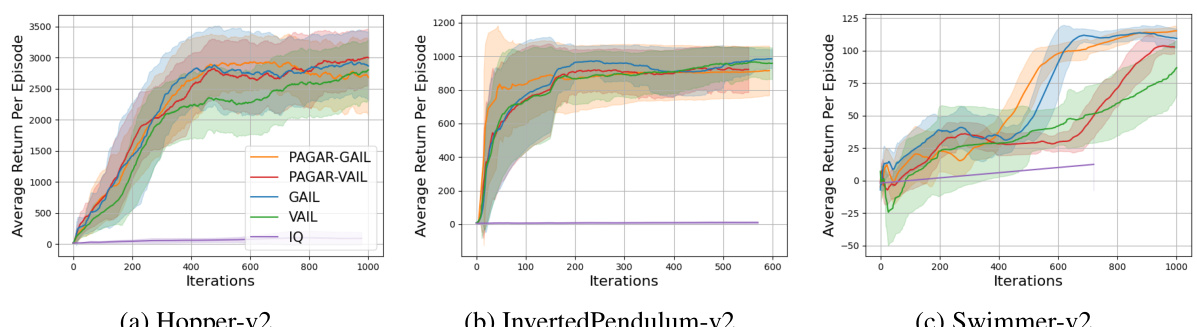

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PAGAR-based imitation learning algorithm (with GAIL and VAIL) against standard baselines (GAIL, VAIL, and IQ-Learn) on two partially observable navigation tasks (DoorKey-6x6 and SimpleCrossingS9N1) from the MiniGrid environment. The results show the average return per episode over the number of time steps (frames) for both scenarios with 10 and 1 expert demonstrations. The plots illustrate the superior performance of PAGAR-based methods, particularly in scenarios with limited data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparing Algorithm 1 with baselines in partial observable navigation tasks. The suffix after each 'PAGAR-' indicates which IRL technique is used in Algorithm 1. The y axis indicates the average return per episode. The x axis indicates the number of time steps.

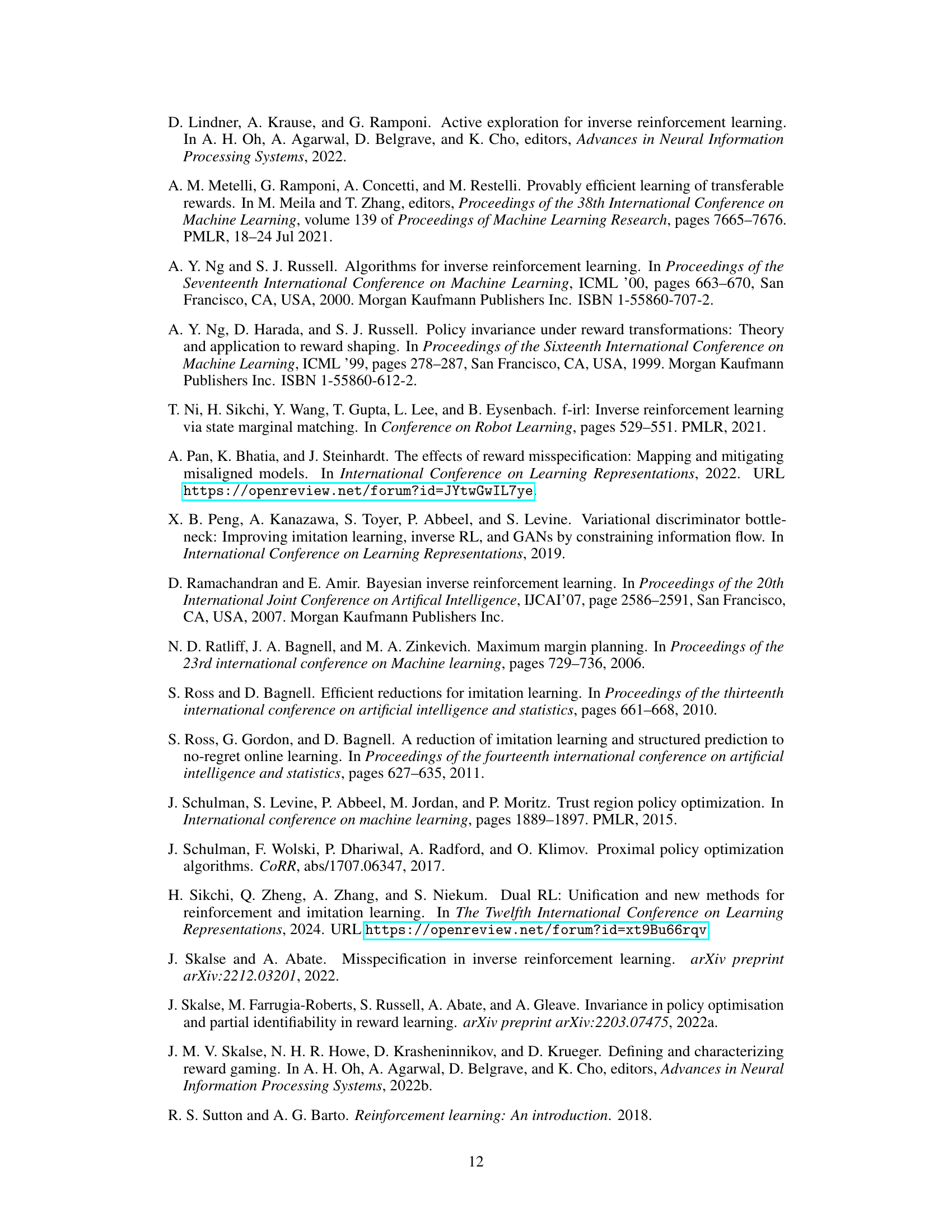

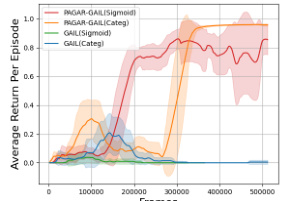

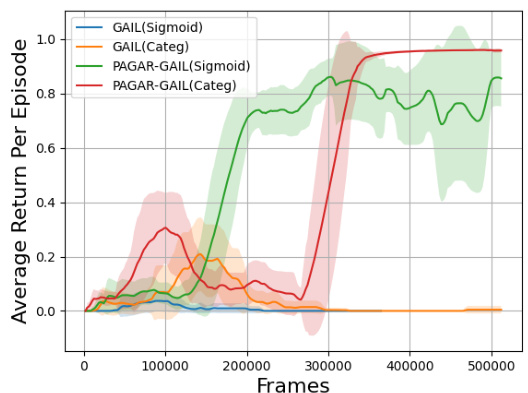

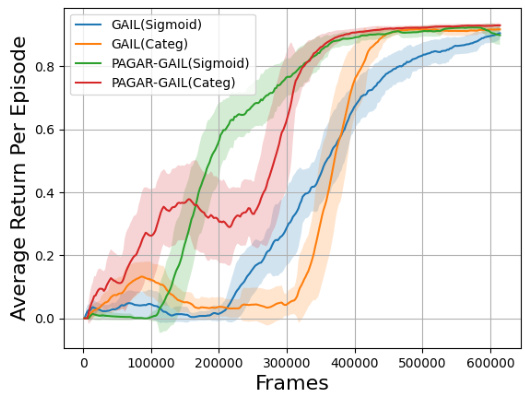

🔼 The figure compares the performance of PAGAR-GAIL and GAIL using different reward function hypothesis sets (Sigmoid and Categorical). It shows that PAGAR-GAIL outperforms GAIL in both cases using fewer samples, highlighting its robustness and efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 3: PAGAR-GAIL in different reward spaces

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PAGAR-based imitation learning algorithm (with two variants, PAGAR-GAIL and PAGAR-VAIL) against several baselines (GAIL, VAIL, and IQ-Learn) on two partially observable navigation tasks (DoorKey-6x6 and SimpleCrossingS9N1) and a transfer learning setting. The results are shown for different numbers of expert demonstrations (1 and 10). The plots show the average return per episode over the number of timesteps (frames). The results highlight PAGAR’s improved sample efficiency and ability to generalize to unseen environments.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparing Algorithm 1 with baselines in partial observable navigation tasks. The suffix after each 'PAGAR-' indicates which IRL technique is used in Algorithm 1. The y axis indicates the average return per episode. The x axis indicates the number of time steps.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper: task alignment vs. data alignment in inverse reinforcement learning. (a) shows how a task-aligned reward function (r+) clearly separates acceptable and unacceptable policies based on their utility, while a task-misaligned reward function (r-) does not. (b) contrasts conventional IRL-based imitation learning (which focuses on data alignment and might produce an unacceptable policy) with the proposed PAGAR framework (which prioritizes task alignment and aims to produce an acceptable policy using multiple reward functions).

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) The two bars respectively represent the policy utility spaces of a task-aligned reward function r+ and a task-misaligned reward function r¯. The white color indicates the utilities of acceptable policies, and the blue color indicates the unacceptable ones. Within the utility space of r⁺, the utilities of all acceptable policies are higher (> U+) than those of the unacceptable ones, and the policies with utilities higher than Ur+ have higher orders than those of utilities lower than Ur+. Within the utility space of r¯, acceptable and unacceptable policies' utilities are mixed together, leading to a low U,- and an even lower Ū- . (b) IRL-based IL relies solely on IRL's optimal reward function r* which can be task-misaligned and lead to an unacceptable policy πρ* ∈ Π\Hacc while PAGAR-based IL learns an acceptable policy π* ∈ Πacc from a set RE,8 of reward functions.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PAGAR-based imitation learning algorithm (with two variants, PAGAR-GAIL and PAGAR-VAIL) against several baselines (GAIL, VAIL, and IQ-Learn) on two partial observable navigation tasks (DoorKey-6x6 and SimpleCrossingS9N1). The results are shown separately for experiments with 1 and 10 expert demonstrations. The plots show the average return per episode over the number of training timesteps. This helps illustrate the effectiveness of PAGAR, especially in scenarios with limited expert data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparing Algorithm 1 with baselines in partial observable navigation tasks. The suffix after each 'PAGAR-' indicates which IRL technique is used in Algorithm 1. The y axis indicates the average return per episode. The x axis indicates the number of time steps.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PAGAR-based imitation learning algorithm (with two variants, PAGAR-GAIL and PAGAR-VAIL) against several baselines (GAIL, VAIL, and IQ-Learn) on two partially observable navigation tasks (DoorKey-6x6 and SimpleCrossingS9N1). It showcases the algorithm’s performance with both 10 and 1 expert demonstrations, highlighting its ability to learn effectively even with limited data. The x-axis represents the number of timesteps (training frames), and the y-axis shows the average return (reward) achieved per episode. The results illustrate that PAGAR outperforms the baselines, particularly when fewer demonstrations are available.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparing Algorithm 1 with baselines in partial observable navigation tasks. The suffix after each 'PAGAR-' indicates which IRL technique is used in Algorithm 1. The y axis indicates the average return per episode. The x axis indicates the number of time steps.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of PAGAR-GAIL and GAIL using different reward function hypothesis sets (Sigmoid vs. Categorical). It shows that PAGAR-GAIL outperforms GAIL in both cases, even with fewer samples. The x-axis represents the number of frames (data points), and the y-axis shows the average return per episode.

read the caption

Figure 3: PAGAR-GAIL in different reward spaces

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PAGAR algorithm (with two variants using GAIL and VAIL) against standard baselines (GAIL, VAIL, and IQ-Learn) on two partially observable navigation tasks (DoorKey-6x6 and SimpleCrossingS9N1) with varying numbers of expert demonstrations. The plots show the average return per episode over the number of time steps or frames, illustrating the learning curves for each algorithm. The results demonstrate PAGAR’s improved sample efficiency and performance, especially when limited demonstrations are available. Transfer learning performance on related tasks is also depicted.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparing Algorithm 1 with baselines in partial observable navigation tasks. The suffix after each 'PAGAR-' indicates which IRL technique is used in Algorithm 1. The y axis indicates the average return per episode. The x axis indicates the number of time steps.

Full paper#