↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current state-of-the-art deepfake detectors often use only blendfake data for training, avoiding deepfake data due to empirically observed performance issues. This raises a critical question: can deepfake data be entirely discarded? This paper investigates this question and finds this to be counter-intuitive. Deepfakes contain additional forgery clues.

To address this, the paper introduces ProDet, a novel method that leverages both blendfake and deepfake data by organizing them progressively in the latent space. This is achieved through an Oriented Progressive Regularizer (OPR) and feature bridging, which ensures a smooth transition between data types and effective use of forgery information from both. Extensive experiments show ProDet outperforms existing methods in generalization and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deepfake detection because it challenges the existing paradigm of solely relying on blendfake data for training. It introduces a novel approach, ProDet, that effectively leverages both blendfake and deepfake data, significantly improving generalization and robustness of deepfake detectors. This opens avenues for improving detection accuracy and adapting to the evolving nature of deepfake technologies, which is vital for addressing privacy and security concerns.

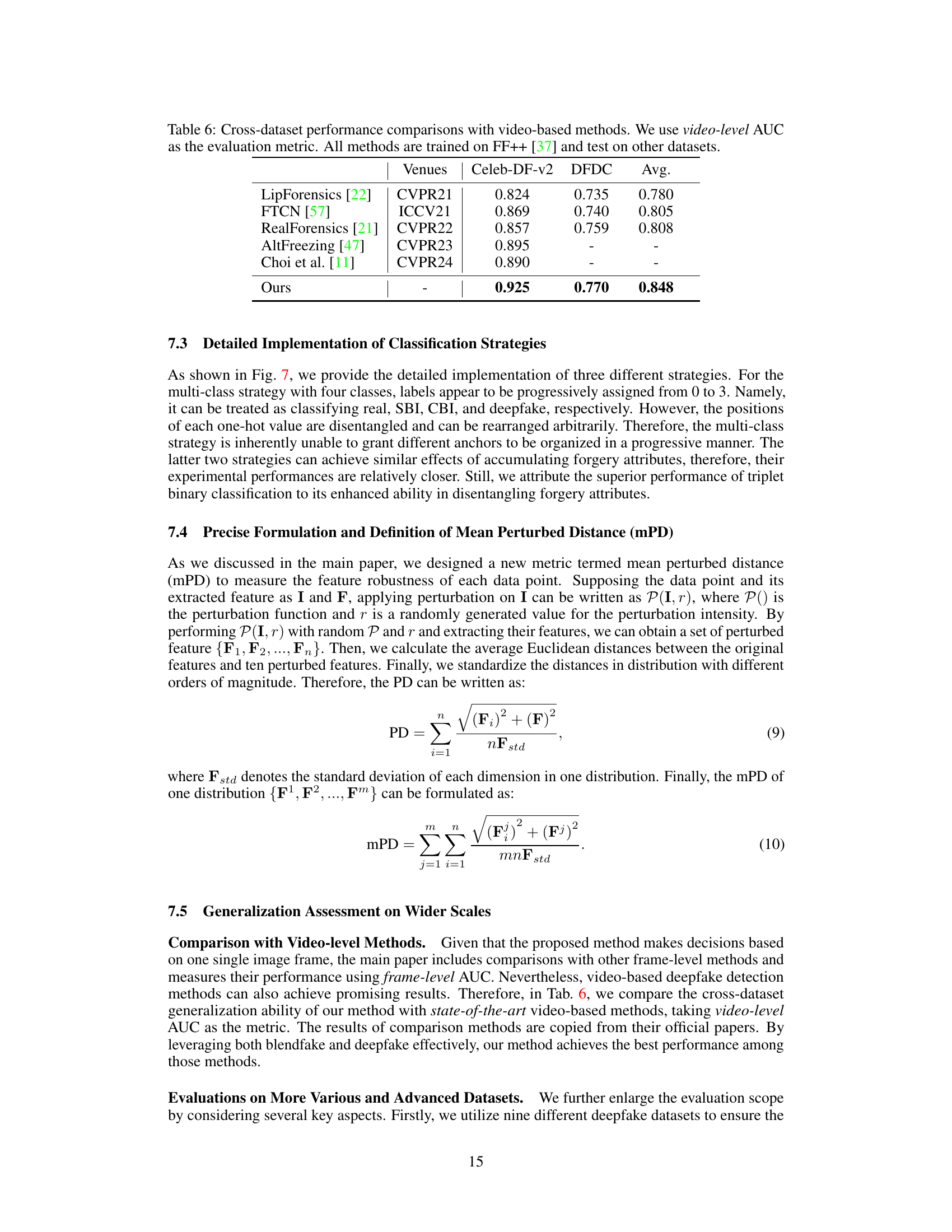

Visual Insights#

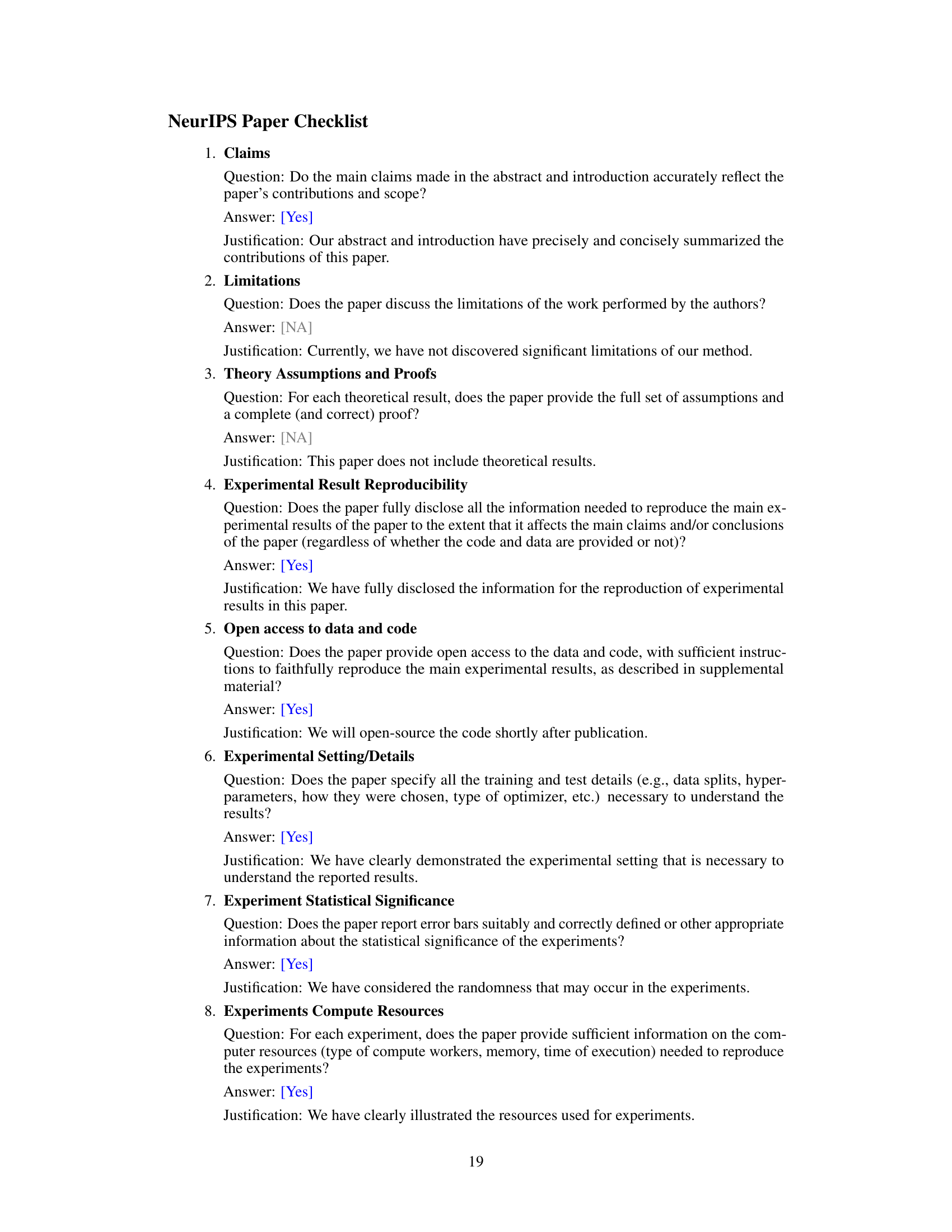

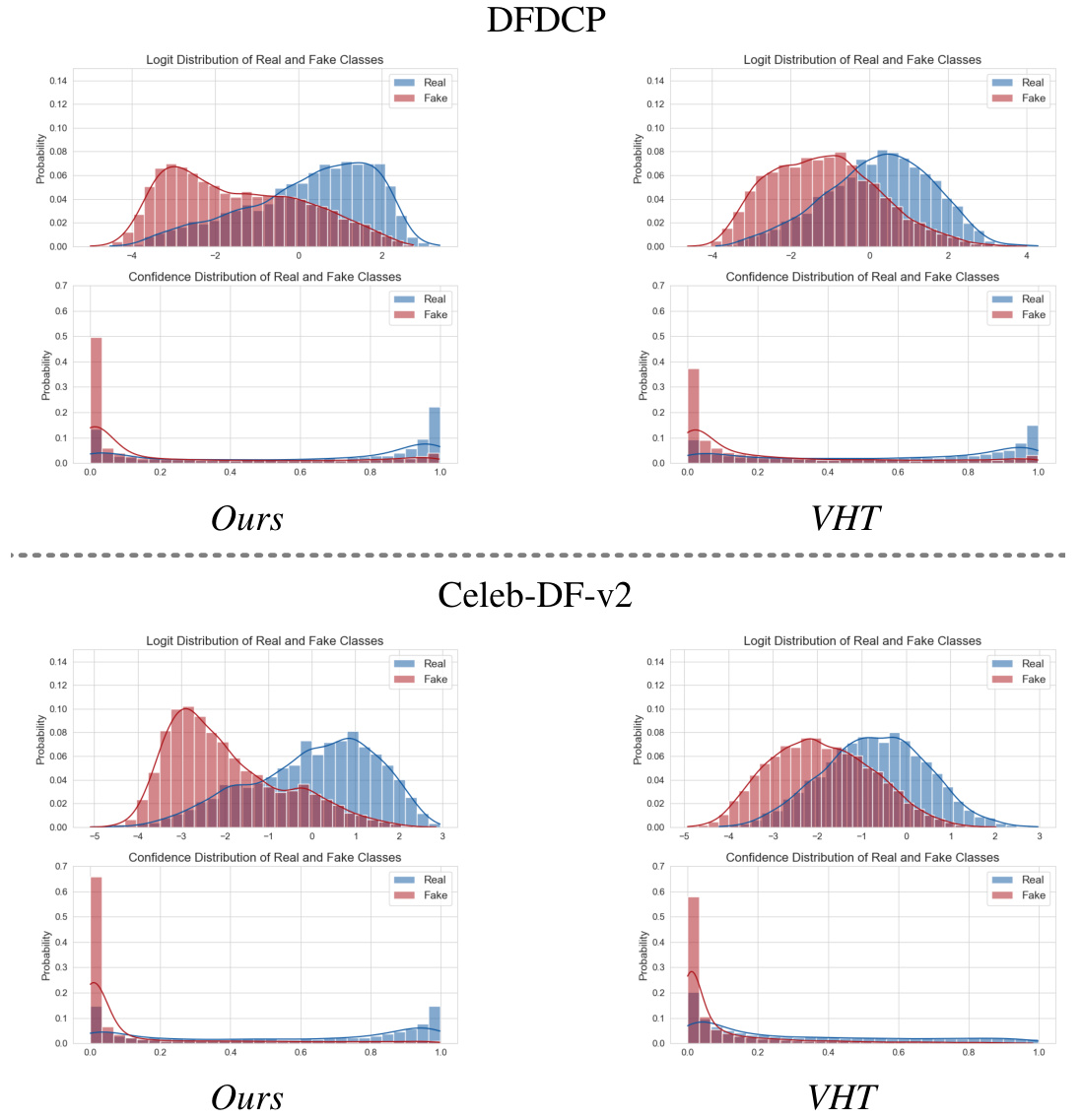

This figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of deepfake detectors trained with different negative sample combinations. (a) shows that simply combining deepfake and blendfake data for training leads to reduced performance, despite an increase in forgery information. (b) illustrates how organizing the latent space during training (as done by the proposed method) allows effective use of both deepfake and blendfake data, leading to improved performance and better separability between deepfake and real samples. The latent space organization makes deepfakes easier to distinguish from real images.

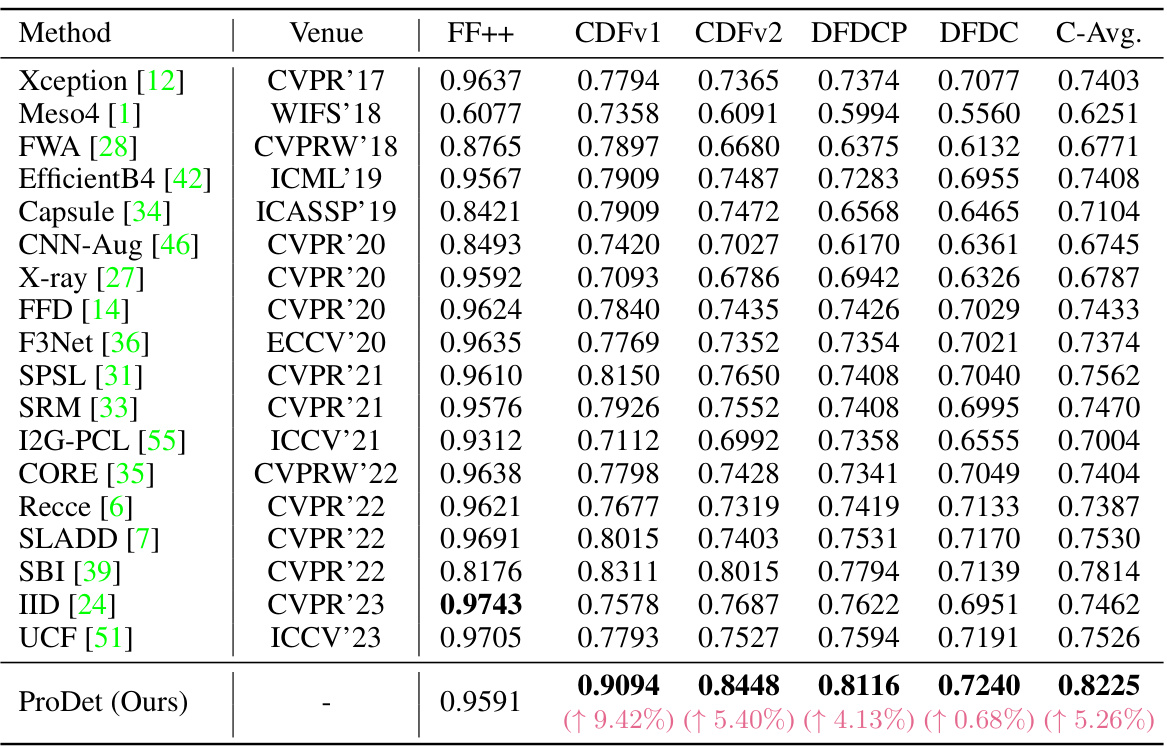

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for various deepfake detection methods evaluated on multiple datasets. It compares the performance of different methods on in-dataset (FaceForensics++) and cross-dataset (Celeb-DF-v1, Celeb-DF-v2, DeepFake Detection Challenge Preview, and DeepFake Detection Challenge) evaluations. The table highlights the best-performing method for each dataset and shows improvements over the previous state-of-the-art.

In-depth insights#

Blendfake’s Role#

The concept of ‘blendfake’ in deepfake detection is crucial for improving the generalization ability of detectors. Blendfake data, created by manually blending real and fake images, helps detectors learn generalizable forgery artifacts like blending boundaries, rather than focusing on specific deepfake generation methods. This is particularly important because real-world deepfakes exhibit a wide variety of techniques and artifacts. However, the relationship between blendfake and actual deepfake data is complex. While blendfake provides valuable generalized features, excluding deepfake data entirely from training can be counterintuitive since deepfakes contain additional forgery clues. The optimal approach likely involves a careful balance and integration of both data types, potentially through techniques that emphasize a progressive transition from real, to blendfake, to deepfake in the model’s feature space. This allows the model to learn a continuous spectrum of forgery cues, leading to more robust and effective detection.

Progressive Training#

Progressive training, in the context of deepfake detection, offers a compelling approach to enhance model robustness and generalization. Instead of simply combining deepfake and blendfake data for training, a progressive approach orders the data to mimic the real-to-fake transition. This structured training process, where the model gradually learns to discriminate between real, blendfake, and deepfake data, is crucial. The key is a careful organization of the feature space, ensuring that blendfake and deepfake samples serve as anchors, guiding the model along a continuous transition path. This structured learning effectively leverages the unique forgery clues present in each data type. By mitigating the abrupt transition between real and fake data, progressive training reduces the risk of overfitting to specific forgery techniques found in a single type of fake data and improves the detector’s ability to handle unseen deepfakes. This method is more effective than methods employing unorganized hybrid training, as demonstrated by experimental results. Ultimately, progressive training enhances generalization by focusing on the underlying process of forgery creation rather than simply memorizing specific examples.

OPR Regularization#

The proposed Oriented Progressive Regularization (OPR) is a novel approach to training deepfake detectors. It addresses the limitations of existing methods by explicitly organizing the latent space representation of training data. Instead of a simple mix of real, blendfake, and deepfake data, OPR introduces a progressive transition, guiding the model to learn increasingly complex forgery features. This is achieved by defining ‘oriented pivot anchors’—representing real, blendfake (SBI and CBI), and deepfake samples—and arranging their distributions progressively in the latent space. Feature bridging further smooths the transition between these anchors, facilitating a continuous progression in forgery feature learning. The effectiveness of OPR is highlighted by its ability to leverage forgery information from both blendfake and deepfake data effectively, which results in improved generalization and robustness. OPR acts as an inductive bias, shaping the network’s learning towards a specific, progressively organized structure that mirrors the generation process of deepfakes. This is different from methods that naively combine different data types, leading to suboptimal performance.

Feature Bridging#

The concept of “Feature Bridging” in the context of deepfake detection is a creative approach to address the limitations of existing methods. Existing methods often treat the transition between real, blendfake, and deepfake data as discrete, rather than a continuous process. Feature bridging aims to rectify this by simulating this smooth transition in the latent feature space. It cleverly uses a mixup technique, creating intermediate representations by blending features of adjacent anchor points (e.g., real and blendfake), thereby promoting a continuous and progressive learning of forgery cues. This approach is particularly valuable because it allows the model to better understand the gradual accumulation of forgery artifacts, avoiding the abrupt transitions that could hinder generalization. The success of feature bridging hinges on the appropriate ordering of the anchors, which are carefully selected based on their inherent forgery characteristics. This ordering is crucial for guiding the model’s learning along the envisioned continuous trajectory from real to deepfake data. In essence, feature bridging serves as a vital component in fostering a more robust and generalizable deepfake detector, bridging the gap between different types of forgery data and enhancing the model’s ability to detect unseen manipulations.

Generalization Limits#

The heading ‘Generalization Limits’ in a deepfake detection research paper would likely explore the challenges in applying models trained on one dataset to unseen deepfakes. Key limitations might include the variety of deepfake creation methods, each with unique artifacts. The paper would likely discuss how models might overfit to specific techniques or datasets, failing to generalize to novel forgeries. Data bias would be a significant consideration, affecting model performance when encountering real-world scenarios with different demographics or image qualities. Adversarial attacks designed to evade detection could also severely restrict generalization. The analysis would likely examine the trade-off between achieving high accuracy on the training data and maintaining robustness across diverse, unseen deepfakes, highlighting the difficulty of creating truly generalized and robust detection systems. Addressing these limitations might involve data augmentation strategies, exploring more generalizable features, or developing more robust model architectures that can better adapt to unseen variations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

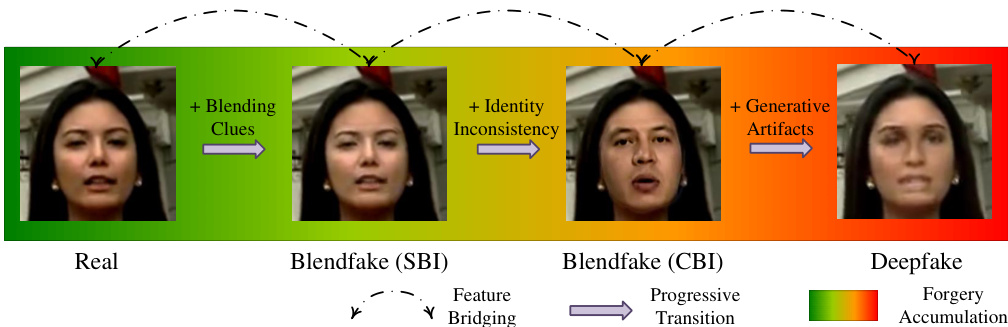

This figure illustrates the concept of a progressive transition from real images to deepfakes, with blendfake images acting as intermediate steps. It highlights three key forgery attributes that accumulate progressively: blending clues, identity inconsistency, and generative artifacts. The blendfake images (Self-Blended Image (SBI) and Cross-Blended Image (CBI)) serve as ‘oriented pivot anchors’ in this transition, guiding the model’s learning process to effectively leverage information from both blendfake and deepfake data.

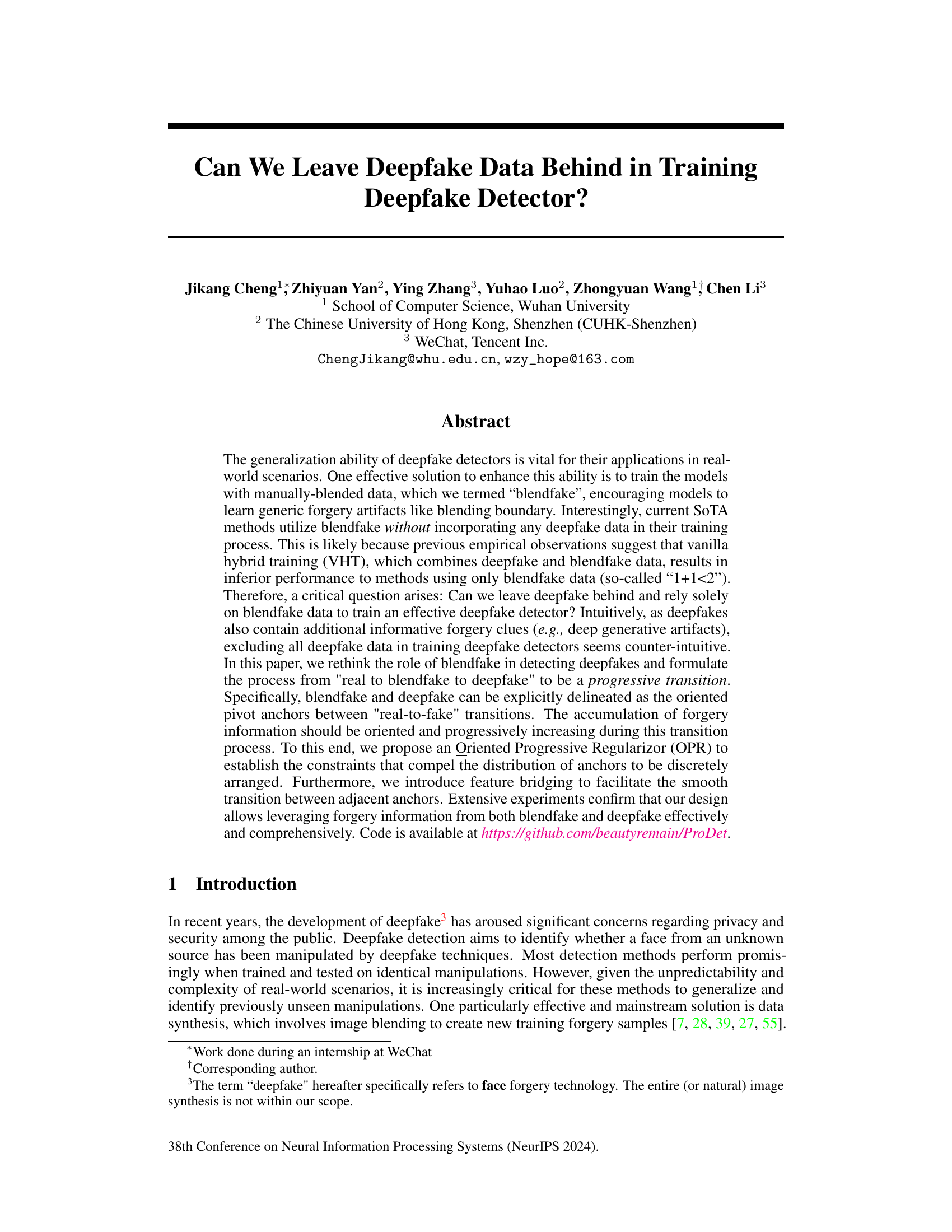

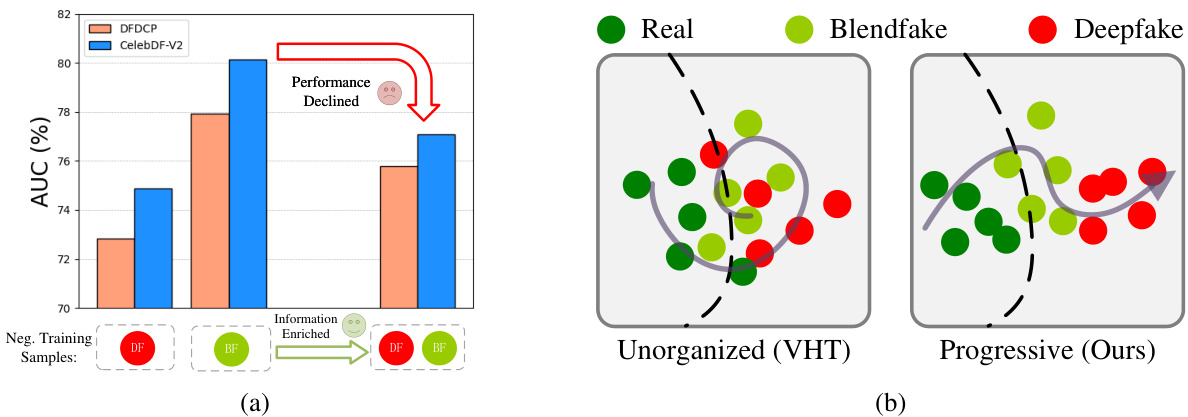

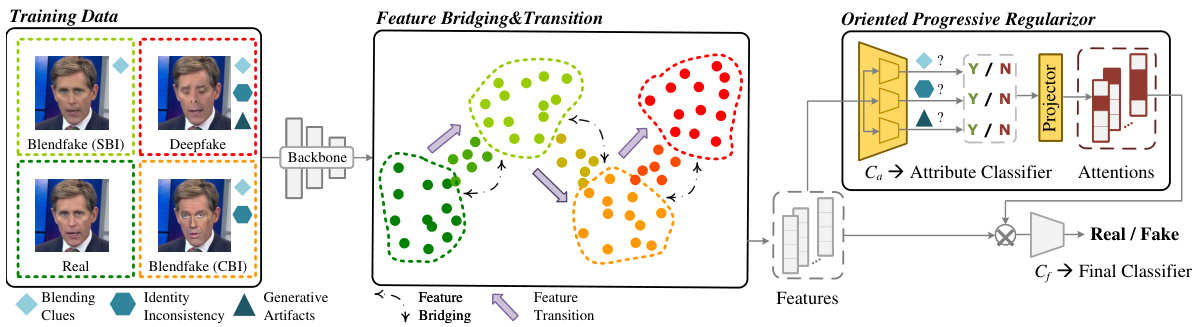

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed method, ProDet. It shows the three main components: Training Data, Feature Bridging & Transition, and Oriented Progressive Regularizor. The Training Data component shows the four types of data used: Real, Blendfake (SBI), Blendfake (CBI), and Deepfake. The Feature Bridging & Transition component demonstrates how the features of these data types are bridged to create a smooth transition in the latent space. This is achieved through feature bridging and feature transition, explicitly aiming for a progressive accumulation of forgery information. The Oriented Progressive Regularizor uses this progressively organized latent space to train the model effectively. The regularizer utilizes multi-attribute classification to assign labels based on forgery attributes (blending clues, identity inconsistency, generative artifacts), creating a progressive accumulation of forgery information. The output from the attribute classifier is then projected and integrated with the features to inform the final deepfake detection results.

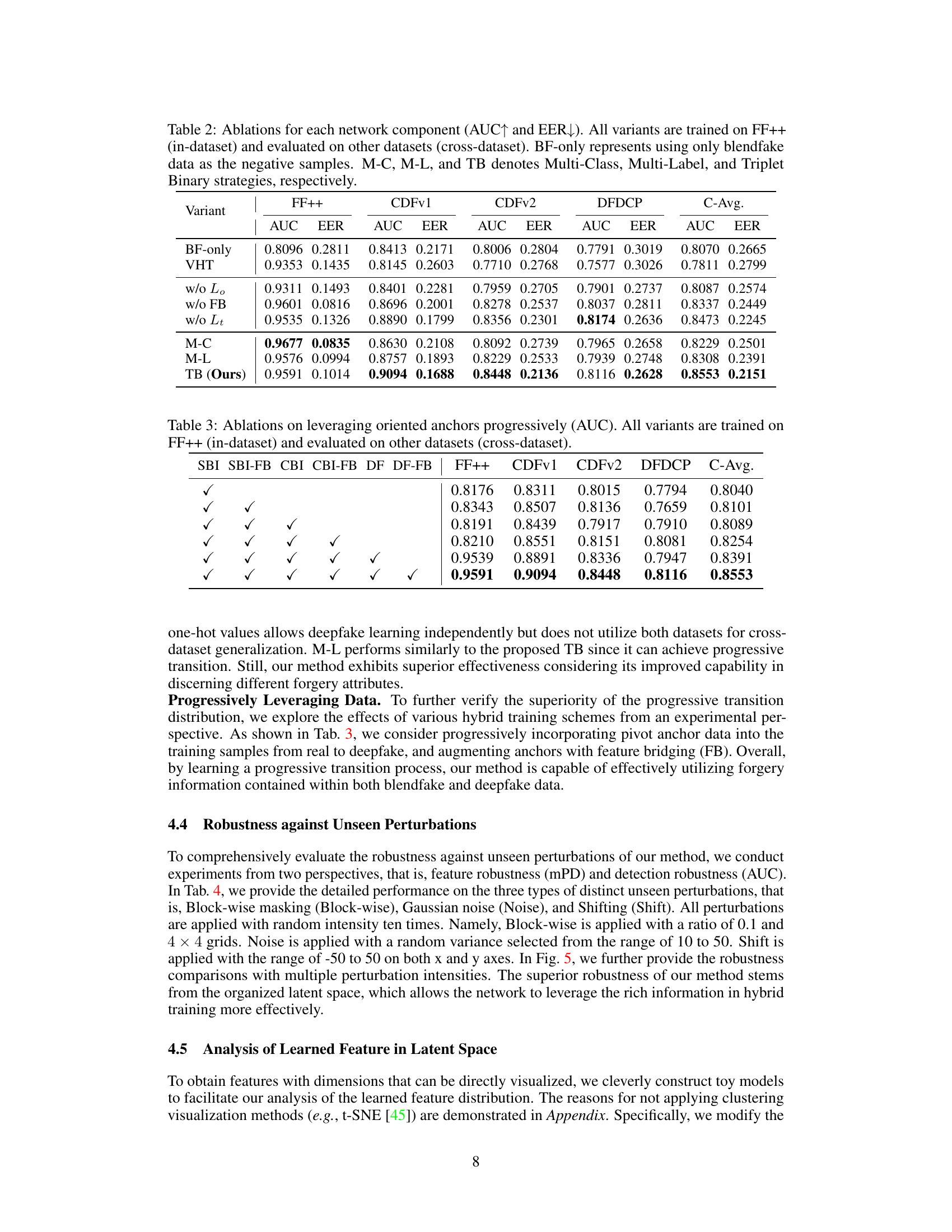

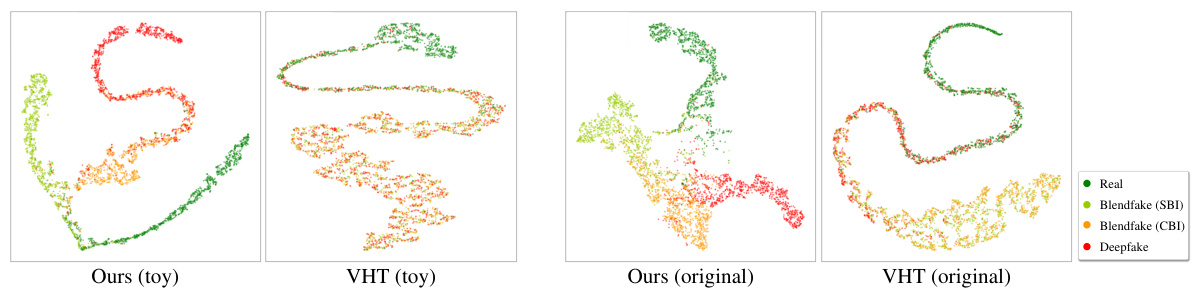

This figure shows the comparison of feature organization and regularity between the proposed method (ProDet) and the vanilla hybrid training (VHT) method. (a) illustrates the latent space distribution of features extracted from both methods. ProDet organizes features in a progressive manner, clearly separating real, blendfake (SBI and CBI), and deepfake data. VHT, however, shows a mixed and unorganized distribution. (b) visualizes feature regularity using a heatmap representing Perturbed Distance (PD) and the average PD (mPD). Lower mPD indicates better regularity. ProDet exhibits significantly lower mPD than VHT, indicating better feature regularity and consequently better generalization ability.

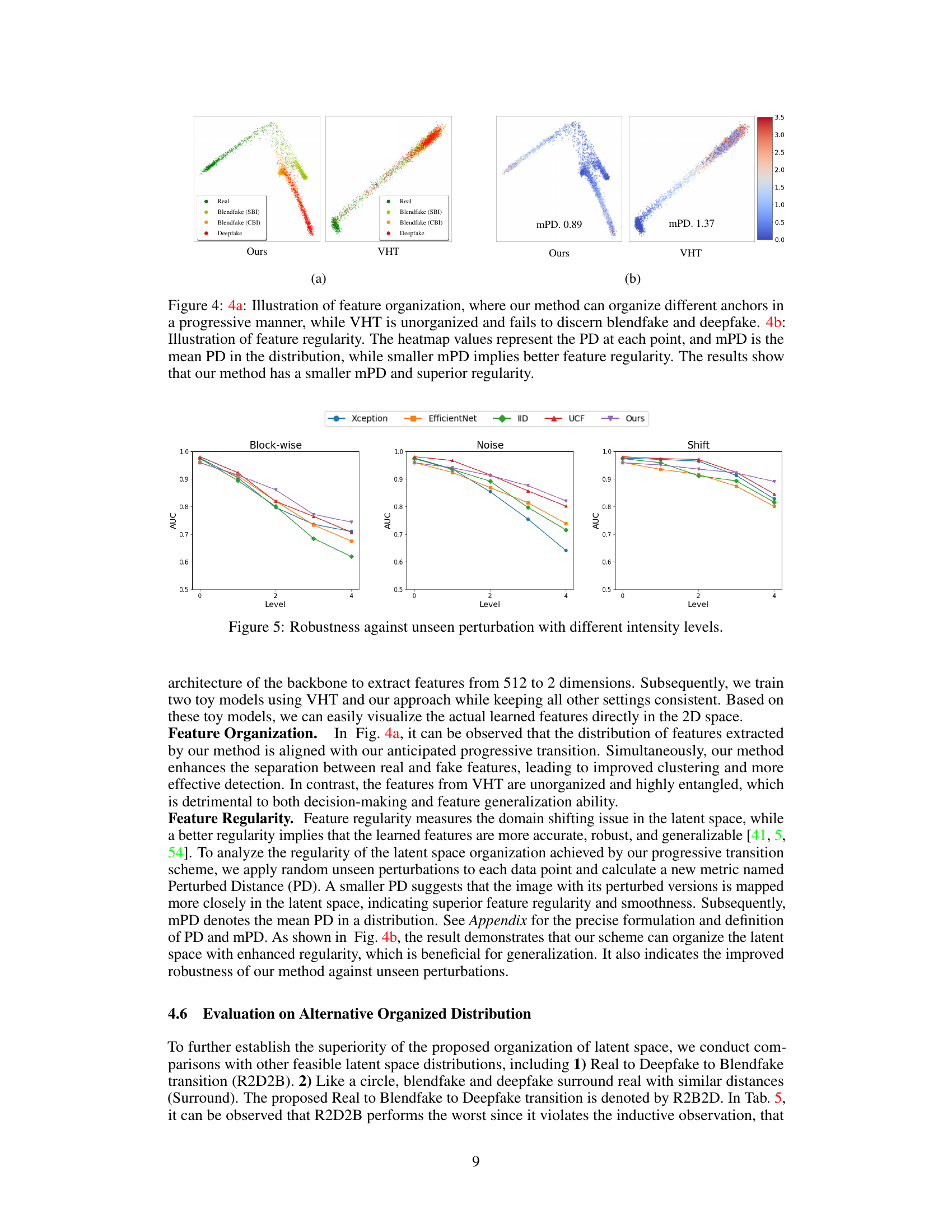

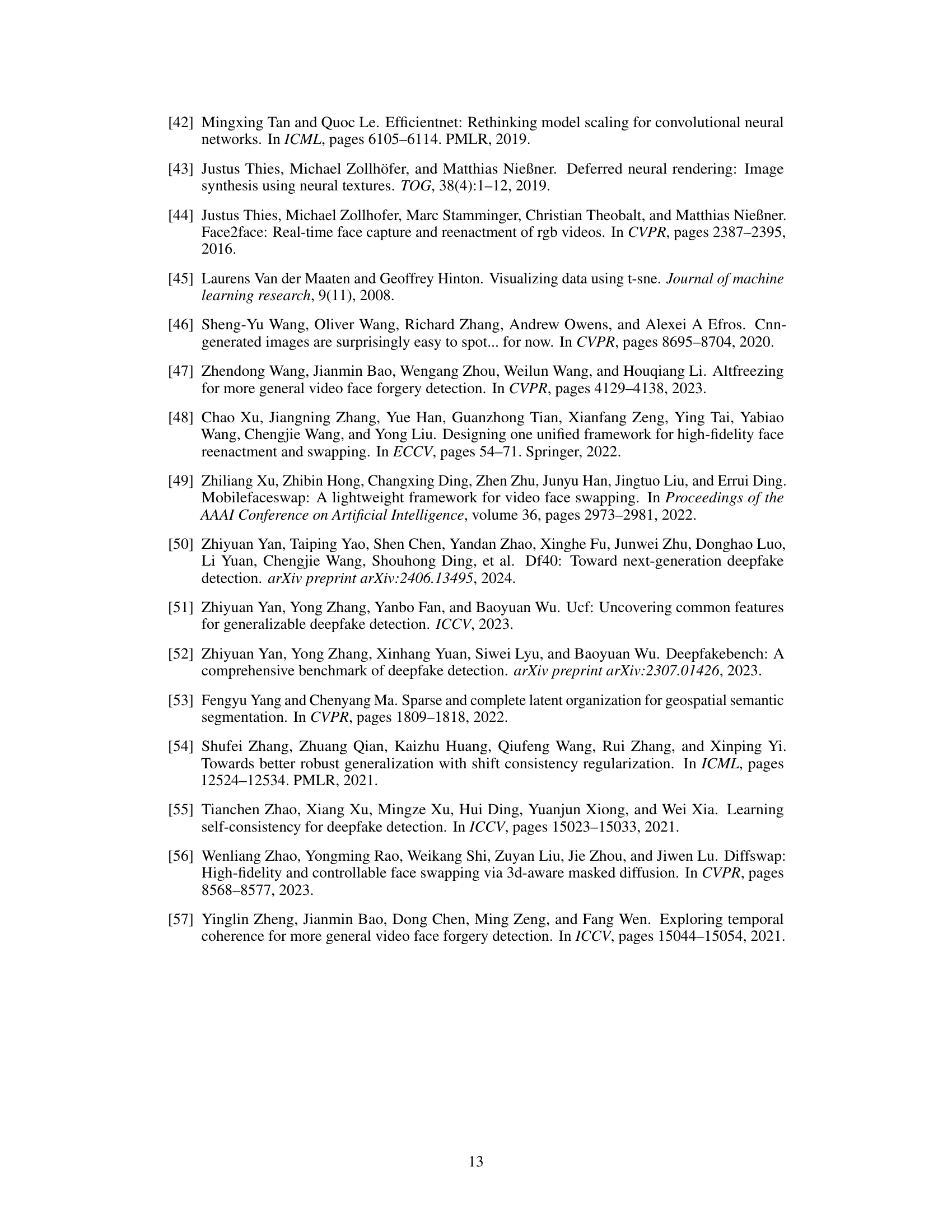

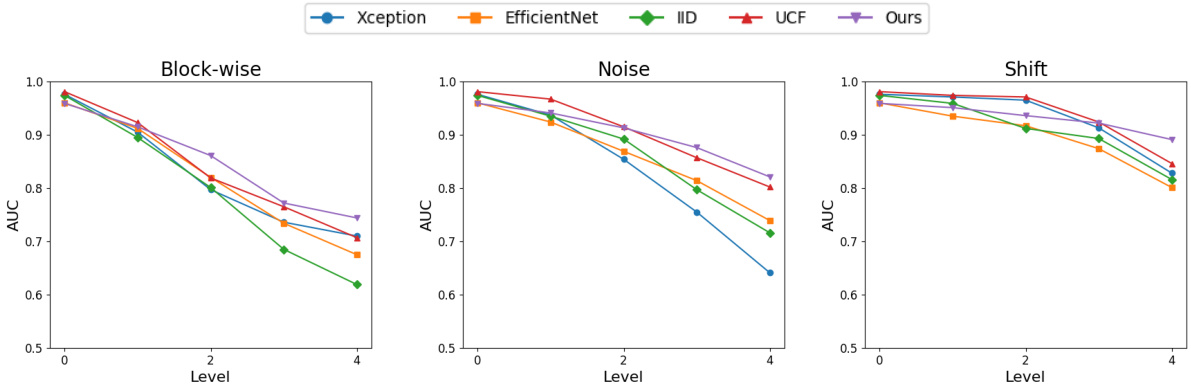

This figure shows the robustness of different deepfake detection methods against three types of unseen perturbations: Block-wise masking, Gaussian noise, and Shifting. Each perturbation type is applied at four different intensity levels (Levels 0-4). The y-axis represents the AUC (Area Under the Curve), a metric measuring the performance of the deepfake detectors. The results show how the AUC changes as the intensity of the perturbation increases. The various lines in the graph represent different deepfake detection methods including Xception, EfficientNet, IID, UCF, and the proposed method (Ours). It illustrates that the proposed method is more robust against unseen perturbations compared to other state-of-the-art methods.

This figure illustrates the concept of a progressive transition from real images to fake images (deepfakes). It visually represents how the characteristics of manipulated images change gradually. Real images are at one end, deepfakes at the other, and two types of blendfakes (SBI and CBI) act as intermediate pivot points. The arrows show the progression, highlighting the accumulation of forgery attributes (blending clues, identity inconsistencies, and generative artifacts) as the transition moves from real to deepfake. This visual representation is crucial to understanding the authors’ proposed method for deepfake detection.

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed deepfake detection method, ProDet. It shows how the real, blendfake (SBI and CBI), and deepfake images are processed through a backbone network to extract features. These features are then passed through feature bridging and transition modules to simulate a continuous transition in the latent space. Finally, an oriented progressive regularizer (OPR) module is used to constrain the distribution of anchors and facilitate the progressive transition. The final deepfake detection result is obtained through a final classifier. The figure highlights the progressive transition from real to fake, with blendfake acting as intermediate anchors.

The figure shows a comparison of saliency map visualizations between the vanilla hybrid training (VHT) method and the proposed method. The visualizations highlight the regions of interest in the network when processing images of different types: real, blendfake (SBI), blendfake (CBI), and deepfake. VHT shows inconsistent focus on facial regions, struggling to clearly distinguish between the types of images. In contrast, the proposed method exhibits more consistent and comprehensive attention to relevant forgery features across the different image types.

This figure visualizes the latent space representations learned by both the proposed method and the vanilla hybrid training (VHT) method using t-SNE. The left panel shows the results for simplified toy models, while the right panel shows the results for the original, more complex models. The visualizations help to illustrate the key difference between the two methods: the proposed method achieves a more organized and progressive transition of features from real to fake data, while VHT results in a more entangled and less organized representation.

Figure 1 shows that naively combining deepfake and blendfake data for training a deepfake detector leads to worse performance than using only blendfake data (1a). This is because the latent space is disorganized, hindering effective learning. In contrast, the proposed method (Ours) uses a progressively organized latent space (1b), effectively leveraging information from both deepfake and blendfake data and improves deepfake detection.

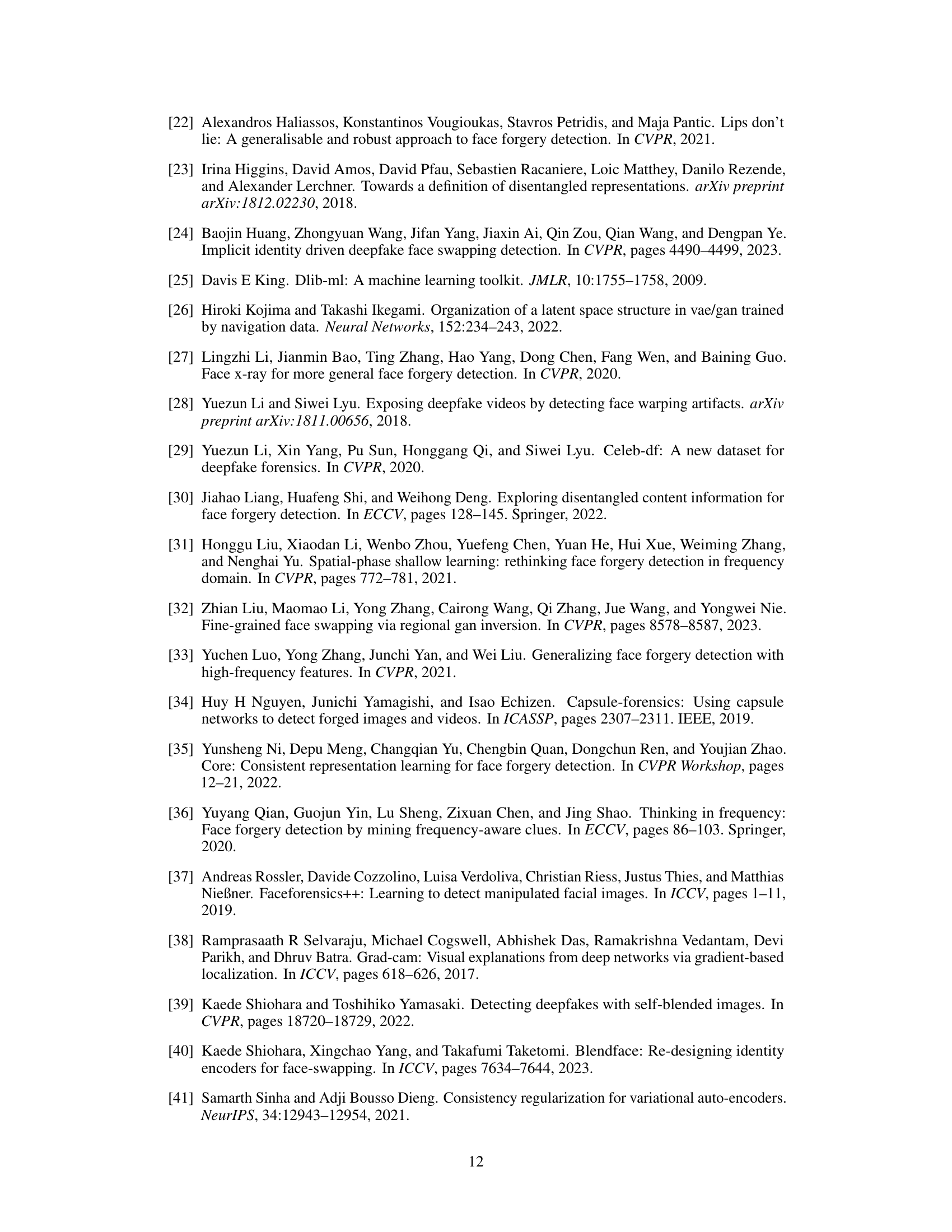

More on tables

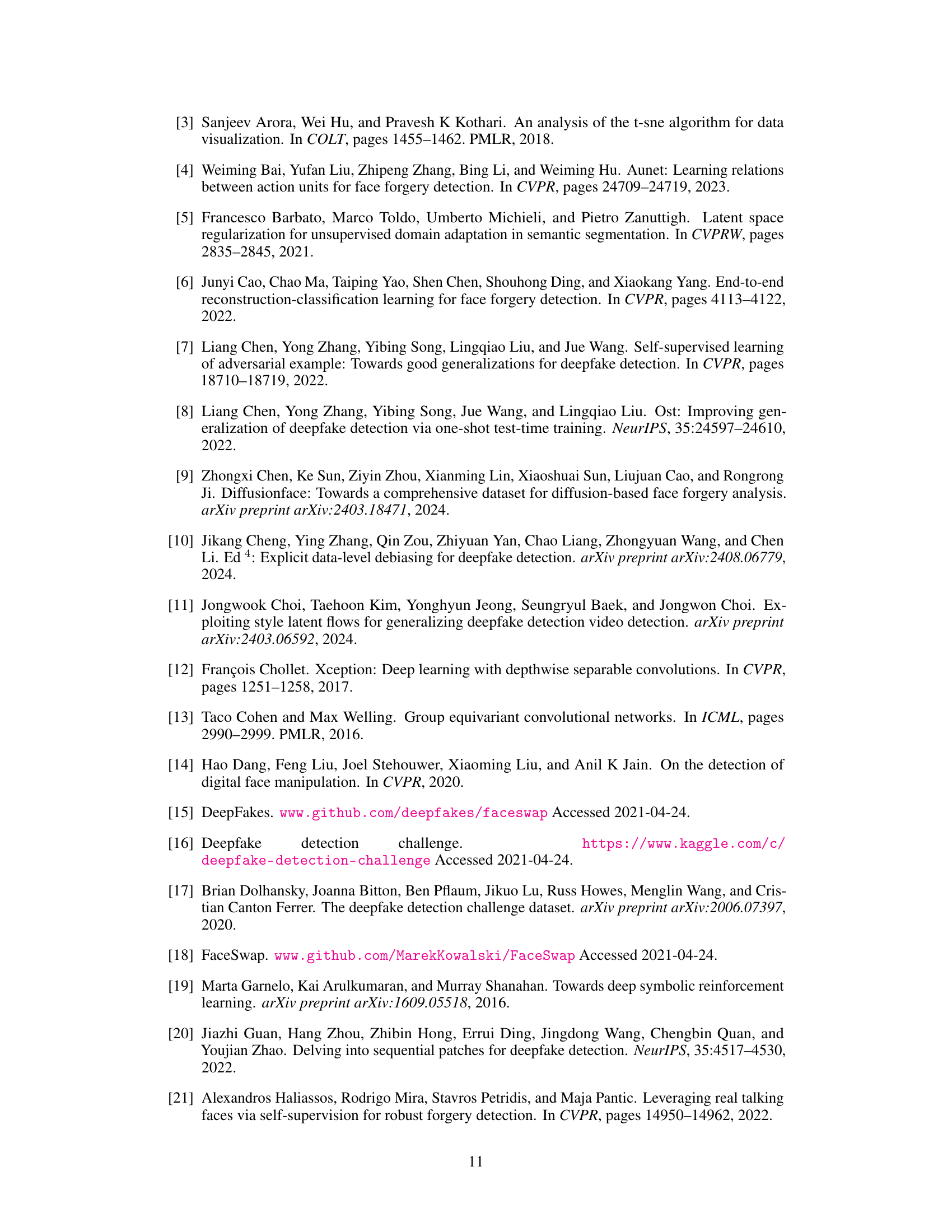

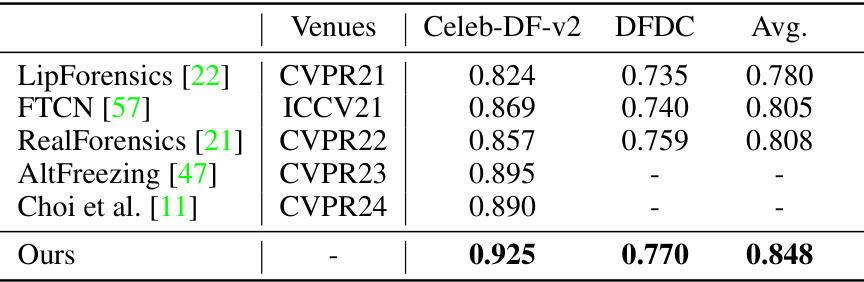

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for various deepfake detection methods on five different datasets. The methods were trained on the FaceForensics++ (FF++) dataset and tested on four other datasets (Celeb-DF-v1, Celeb-DF-v2, DeepFake Detection Challenge Preview, and DeepFake Detection Challenge). The table highlights the best performing method for each dataset and shows the improvement in cross-dataset performance compared to the previous state-of-the-art. The average AUC across all cross-dataset evaluations is also included.

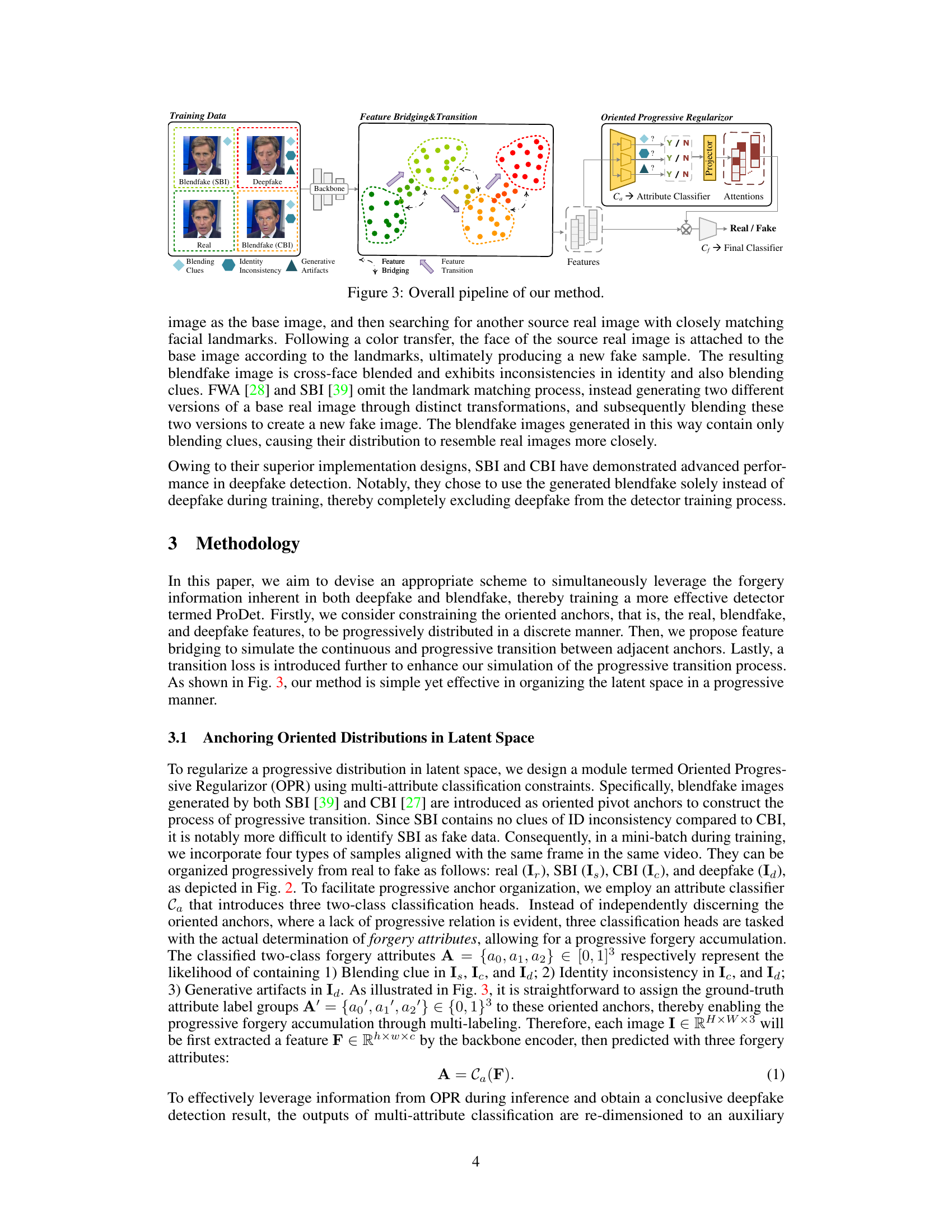

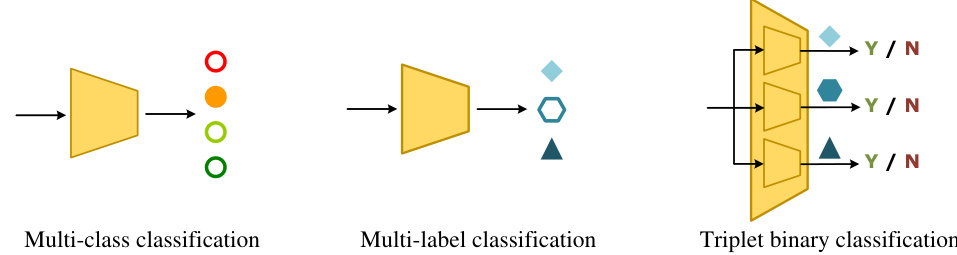

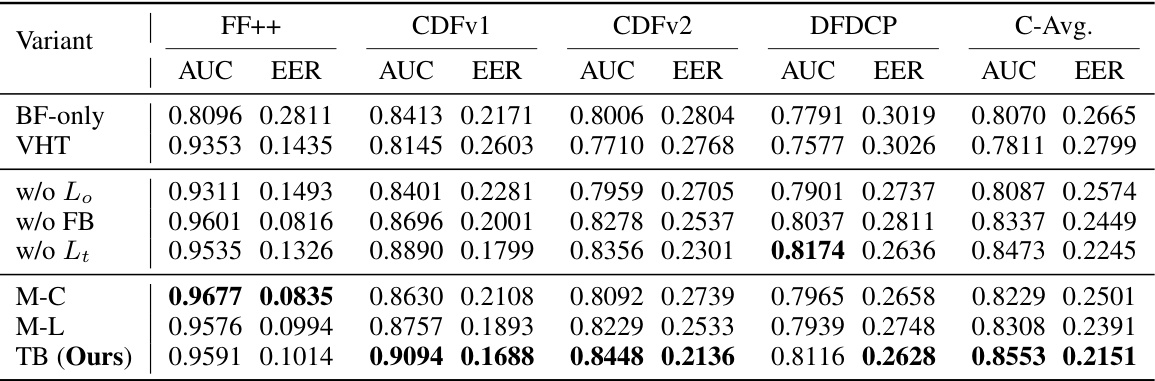

This table presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of different components of the proposed method (ProDet) on deepfake detection performance. It compares the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Equal Error Rate (EER) metrics across four different datasets (cross-dataset evaluation). The variants include using only blendfake data (BF-only), vanilla hybrid training (VHT), and removing different components of ProDet (w/o Lo, w/o FB, w/o Lt). It also shows a comparison of three different multi-attribute classification strategies: Multi-Class (M-C), Multi-Label (M-L), and Triplet Binary (TB), highlighting the performance of the proposed TB strategy.

This table presents the ablation study results. It shows the impact of different components of the proposed method (ProDet) on the deepfake detection performance. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) and EER (Equal Error Rate) metrics are reported for both in-dataset (FF++) and cross-dataset evaluations. The table compares the baseline of using only blendfake data (BF-only) and vanilla hybrid training (VHT) with different combinations of the proposed components: Oriented Progressive Regularizer (OPR) with various classification strategies (multi-class, multi-label, triplet binary), feature bridging, and transition loss. It helps assess the contribution of each component to the overall performance.

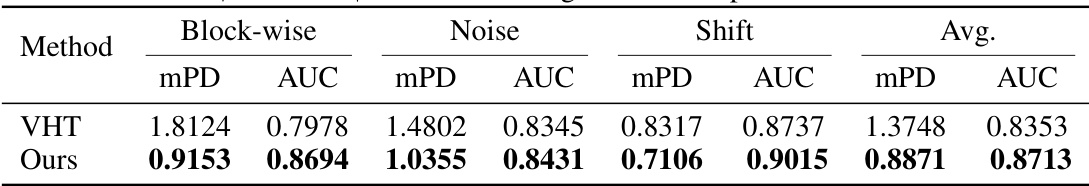

This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the robustness of two deepfake detection models (VHT and the proposed model, ‘Ours’) against three types of unseen perturbations: Block-wise masking, Gaussian noise, and Shifting. The table shows the mean perturbed distance (mPD) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) for each perturbation type and for both models. Lower mPD values indicate better robustness, while higher AUC values indicate better detection performance. The average mPD and AUC across all perturbation types are also provided.

This table presents the AUC scores achieved by different latent space organizations on four different datasets. The methods compared include the unorganized vanilla hybrid training (VHT), R2D2B (Real to Deepfake to Blendfake), Surround (Blendfake and Deepfake surrounding Real), and the proposed R2B2D (Real to Blendfake to Deepfake). The table showcases the performance of each method across various datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed R2B2D organization in improving the generalization ability of deepfake detectors.

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores achieved by various deepfake detection methods on four different datasets: Celeb-DF-v1, Celeb-DF-v2, DeepFake Detection Challenge Preview (DFDCP), and DeepFake Detection Challenge (DFDC). The methods were initially trained on the FaceForensics++ (FF++) dataset. The table highlights the best performing method for each dataset and indicates improvements compared to the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA). It also notes that a more detailed comparison with video-based methods can be found in the appendix.

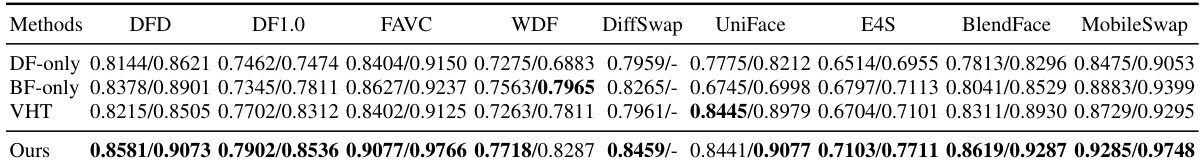

This table presents the cross-dataset generalization performance of various deepfake detection methods, including DF-only, BF-only, VHT, and the proposed ProDet method. The results are reported as AUC scores for multiple deepfake datasets: DFD, DF1.0, FAVC, WDF, DiffSwap, UniFace, E4S, BlendFace, and MobileSwap. Each entry shows the performance (AUC) on in-dataset and cross-dataset evaluations. The proposed method consistently outperforms other approaches across all datasets, demonstrating improved generalization capability.

Full paper#