↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research in emergent communication struggles to replicate fundamental aspects of human language, such as spatial deixis (pointing through language). This limits the efficiency and generalizability of AI communication. Existing methods often lack the capacity to express spatial relations, hindering progress in creating more natural and effective AI interactions.

This paper addresses this challenge by designing a referential game that incentivizes agents to communicate about spatial relationships. The study successfully demonstrates that agents develop a language capable of expressing these relationships, achieving high accuracy. Furthermore, a novel analytical method (NPMI) was used to interpret the emergent language, revealing insights into its structure and composition. This research showcases the feasibility of developing interpretable AI communication systems that incorporate fundamental human language features such as spatial reference and advances the understanding of language emergence.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it demonstrates the emergence of spatial language in AI agents, a significant step towards creating more human-like and efficient AI communication. It introduces a novel method for analyzing emergent languages and offers insights into the underlying mechanisms of language development. This work has implications for improving AI communication and provides new avenues for investigating the fundamental properties of human language. The interpretability of the emergent language achieved is of particular interest to researchers.

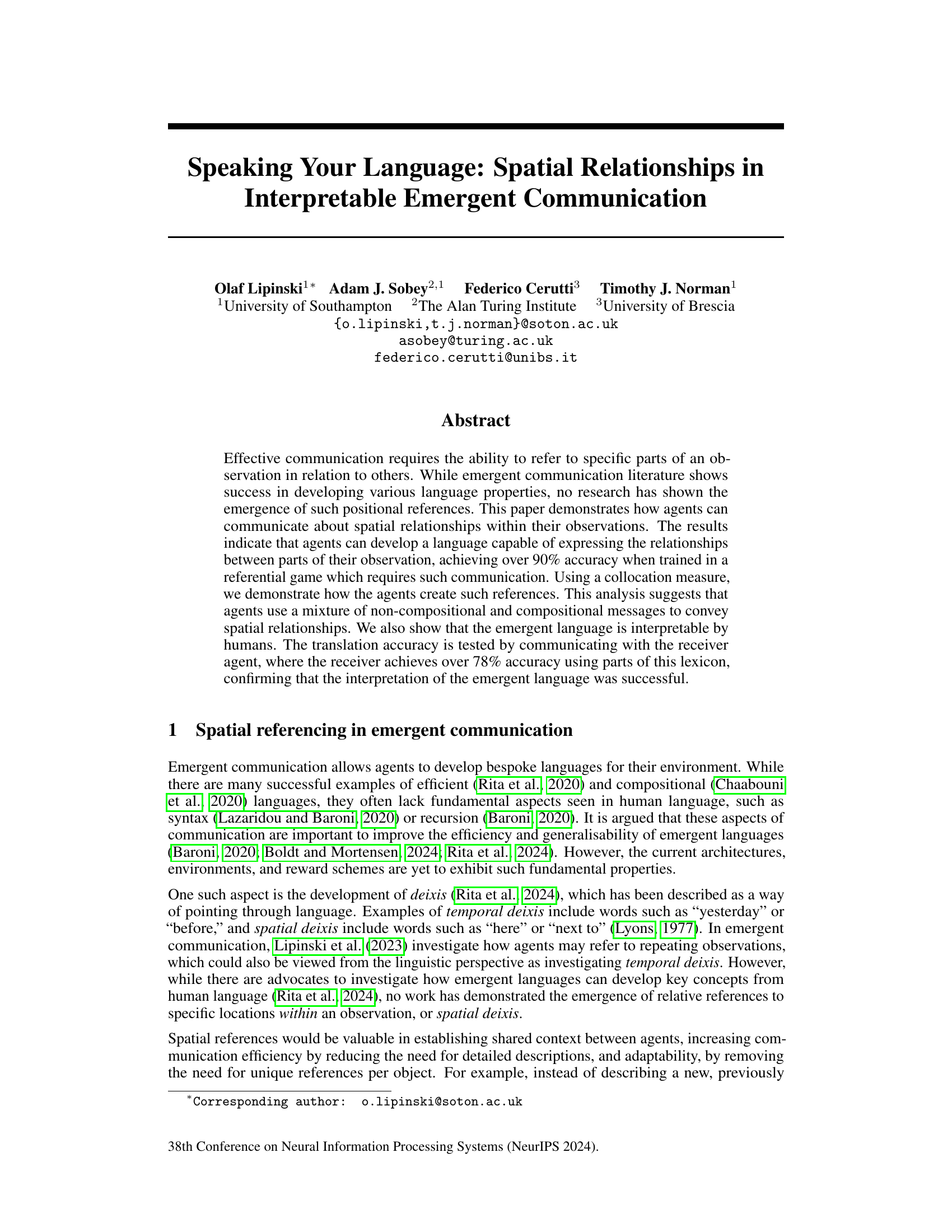

Visual Insights#

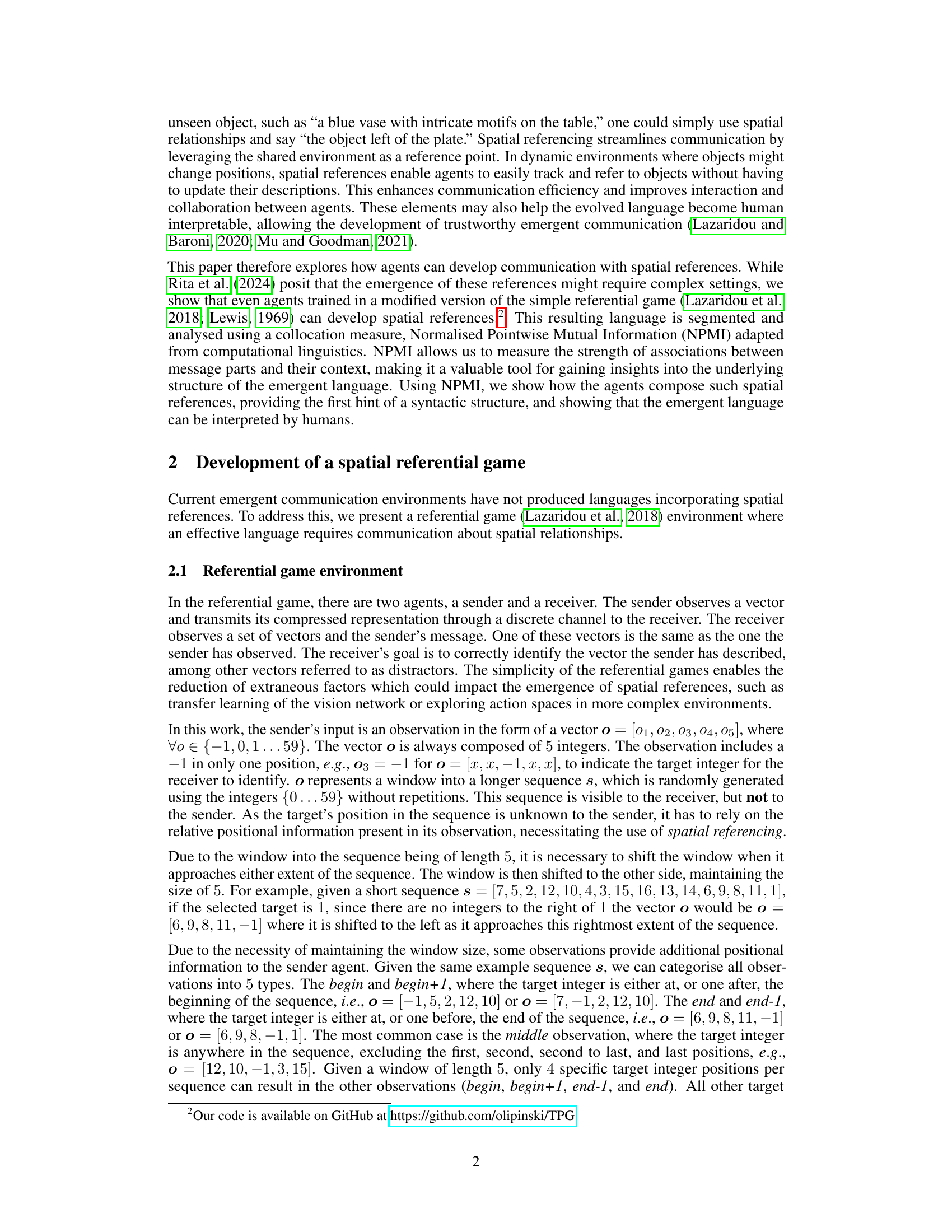

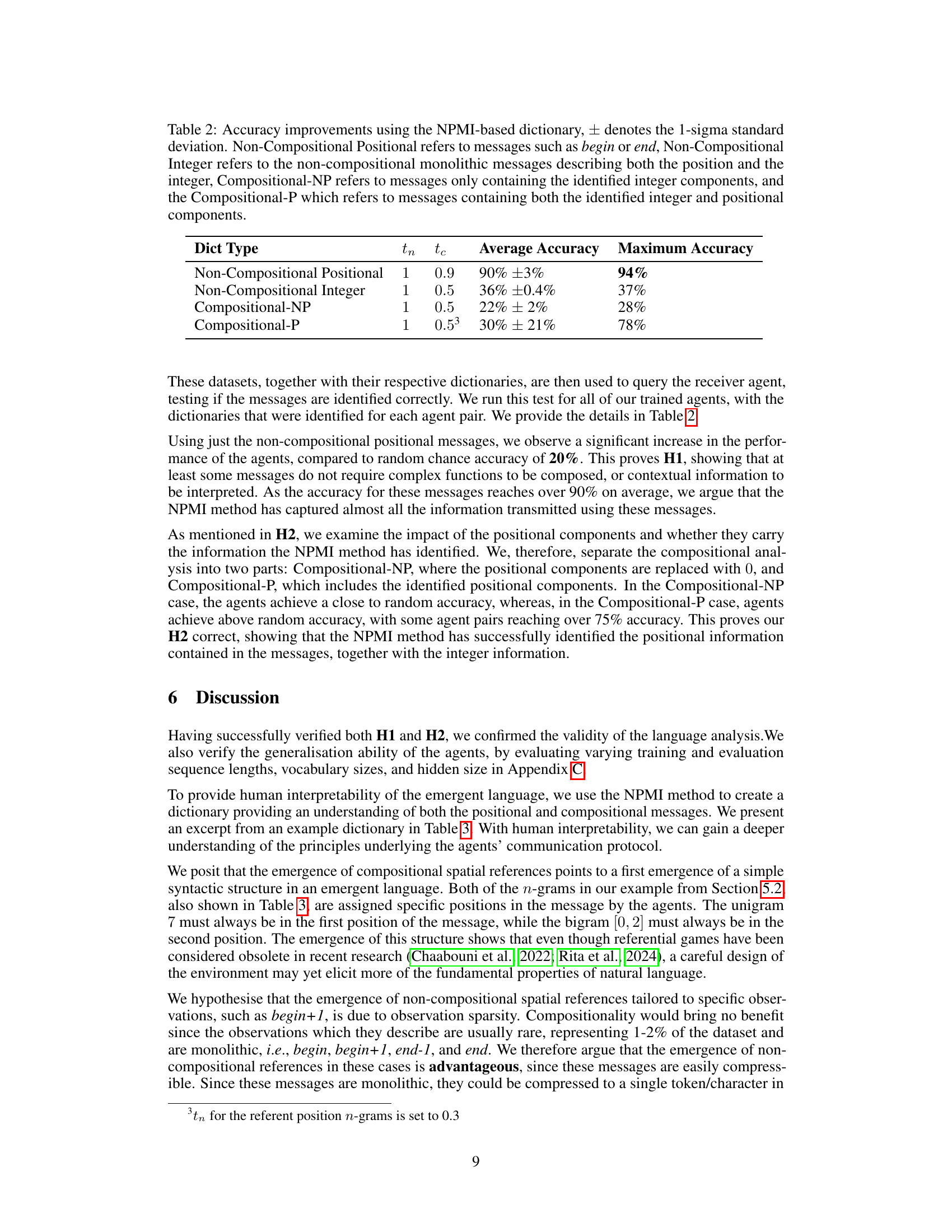

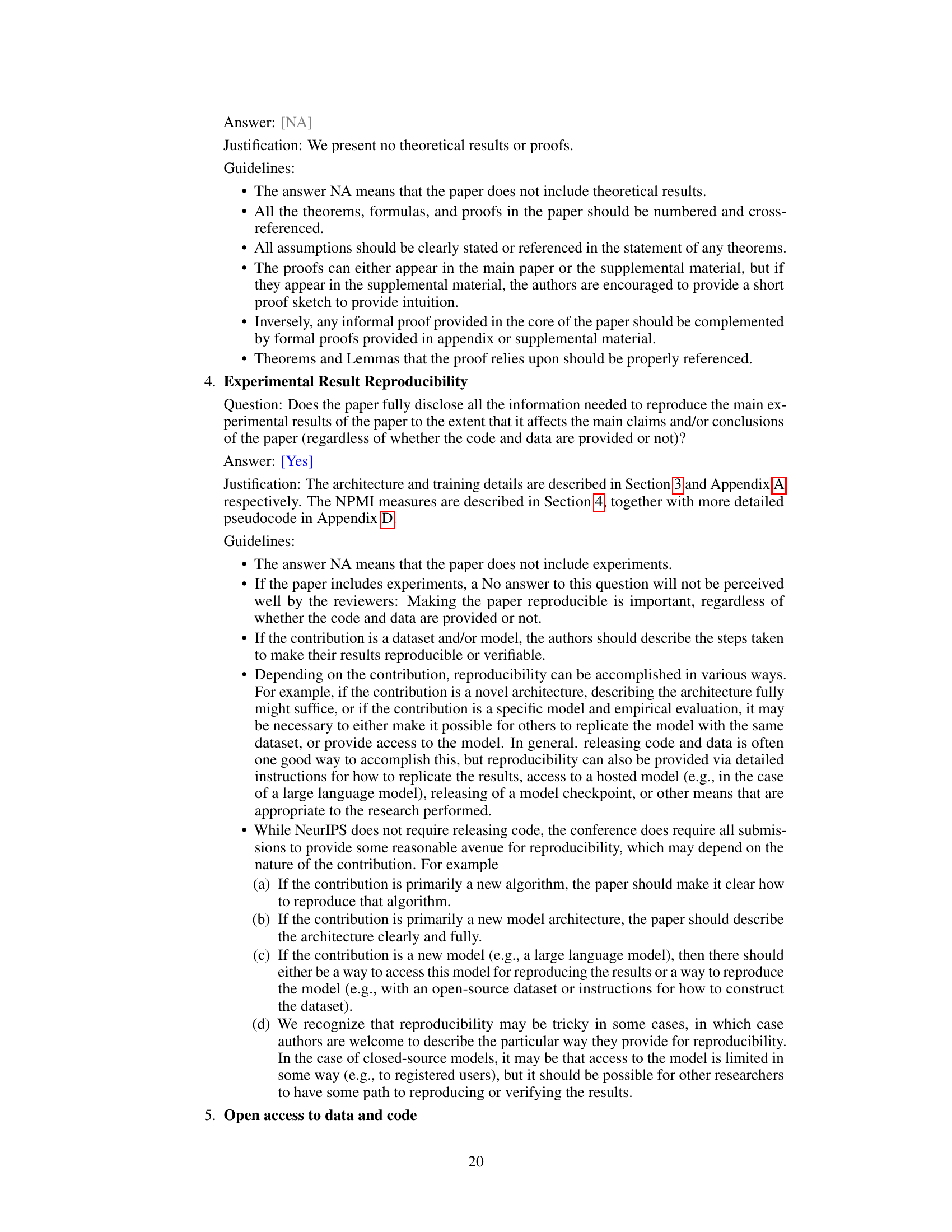

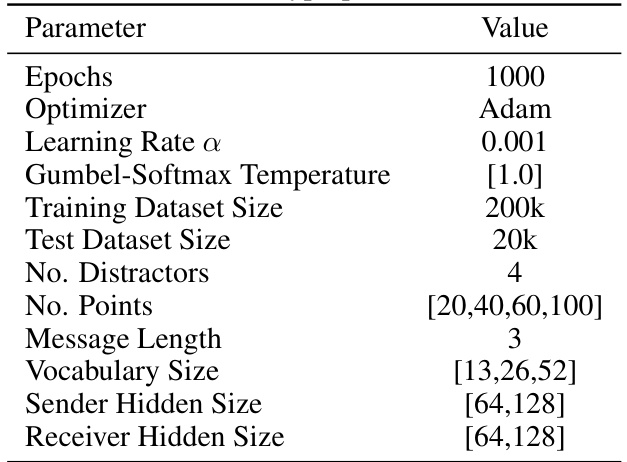

This figure shows the architecture of both the sender and receiver agents used in the experiment. The sender agent takes an observation as input and produces a message, while the receiver agent takes the message, the full sequence, and the target and distractors as inputs, and outputs the correct index of the target integer in the distractor set. The architecture uses GRUs (Gated Recurrent Units) for processing sequential data and a Gumbel-Softmax function for message generation. The sender uses one GRU to process the observation and then passes the resulting hidden state to another GRU for message generation. The receiver uses two GRUs, one to process the message and another to process the sequence, and combines their output to make a prediction.

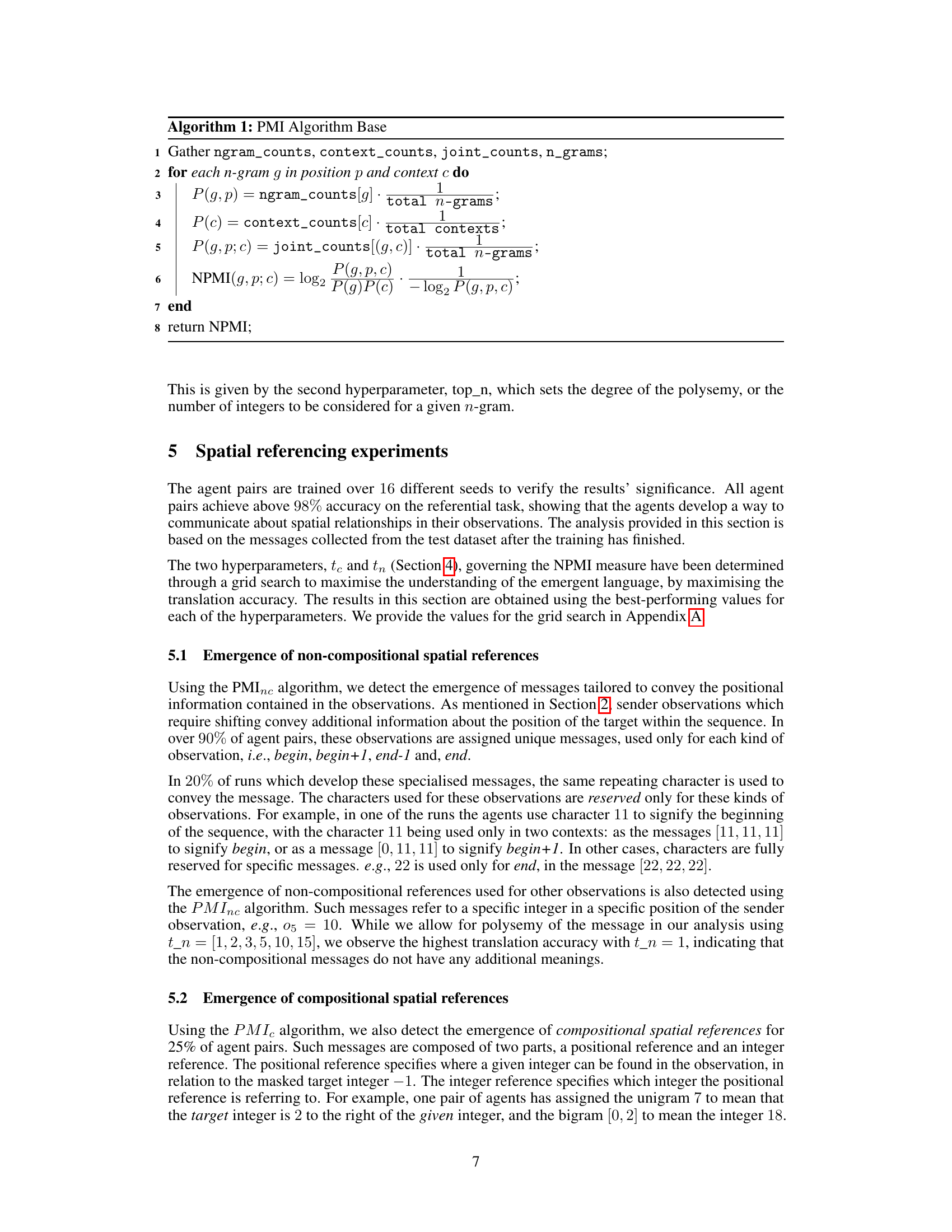

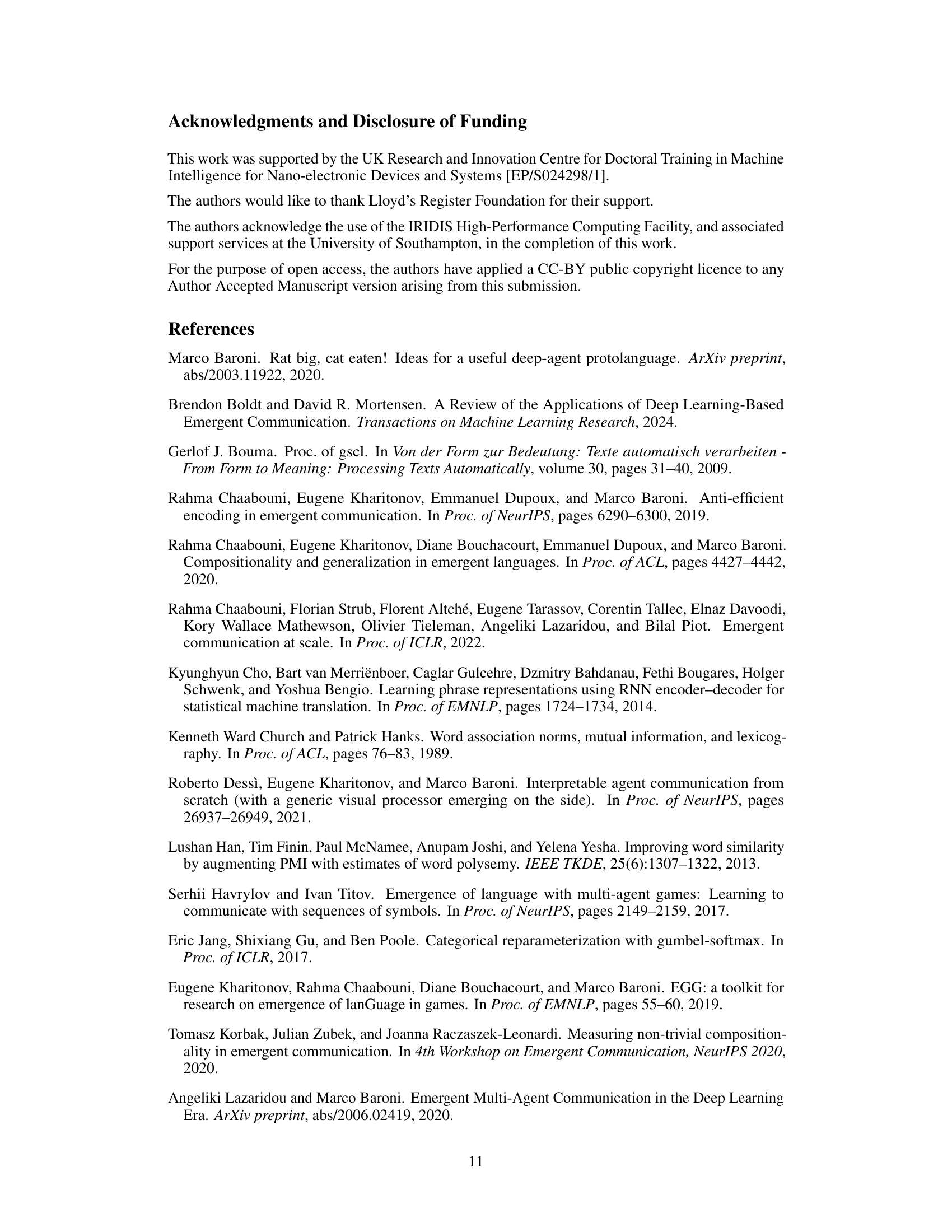

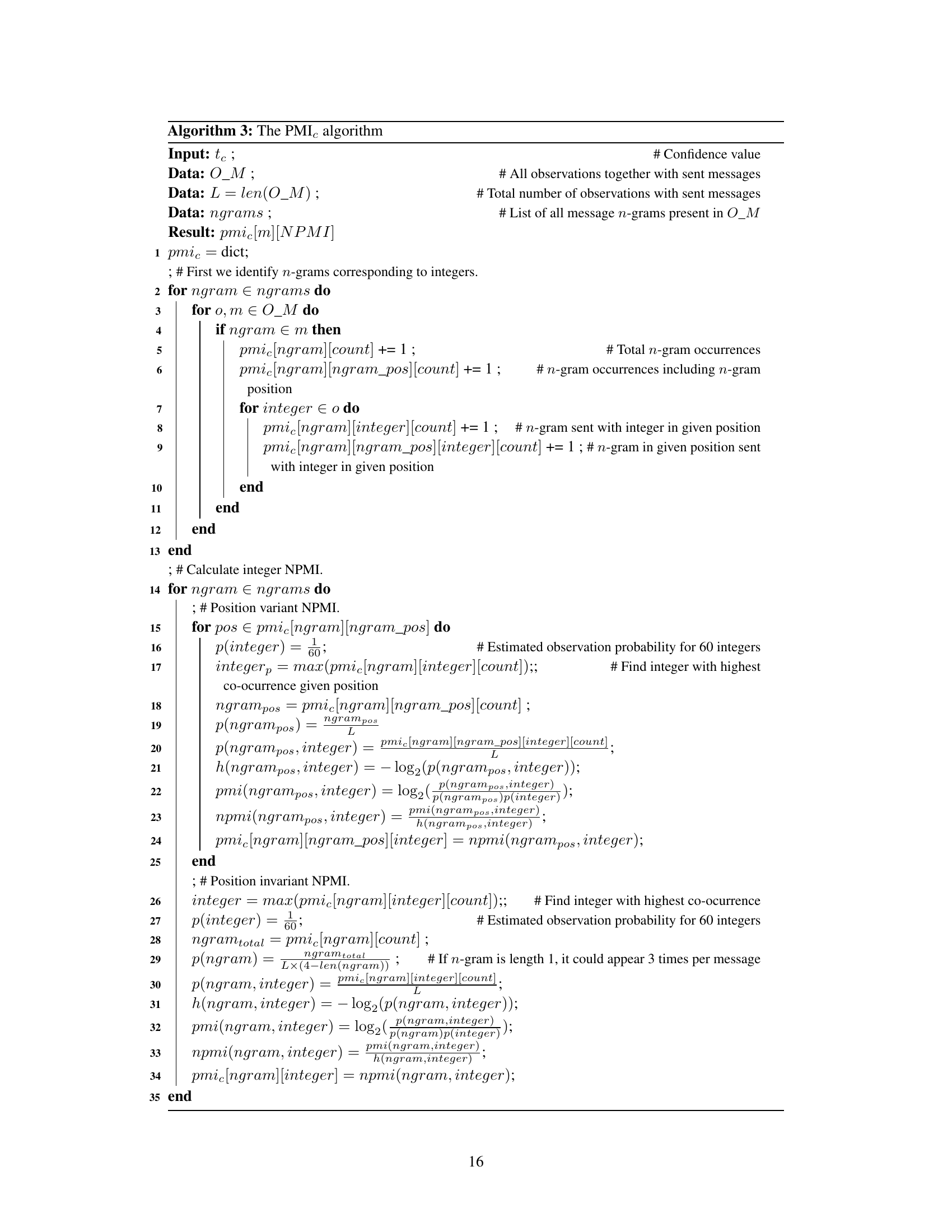

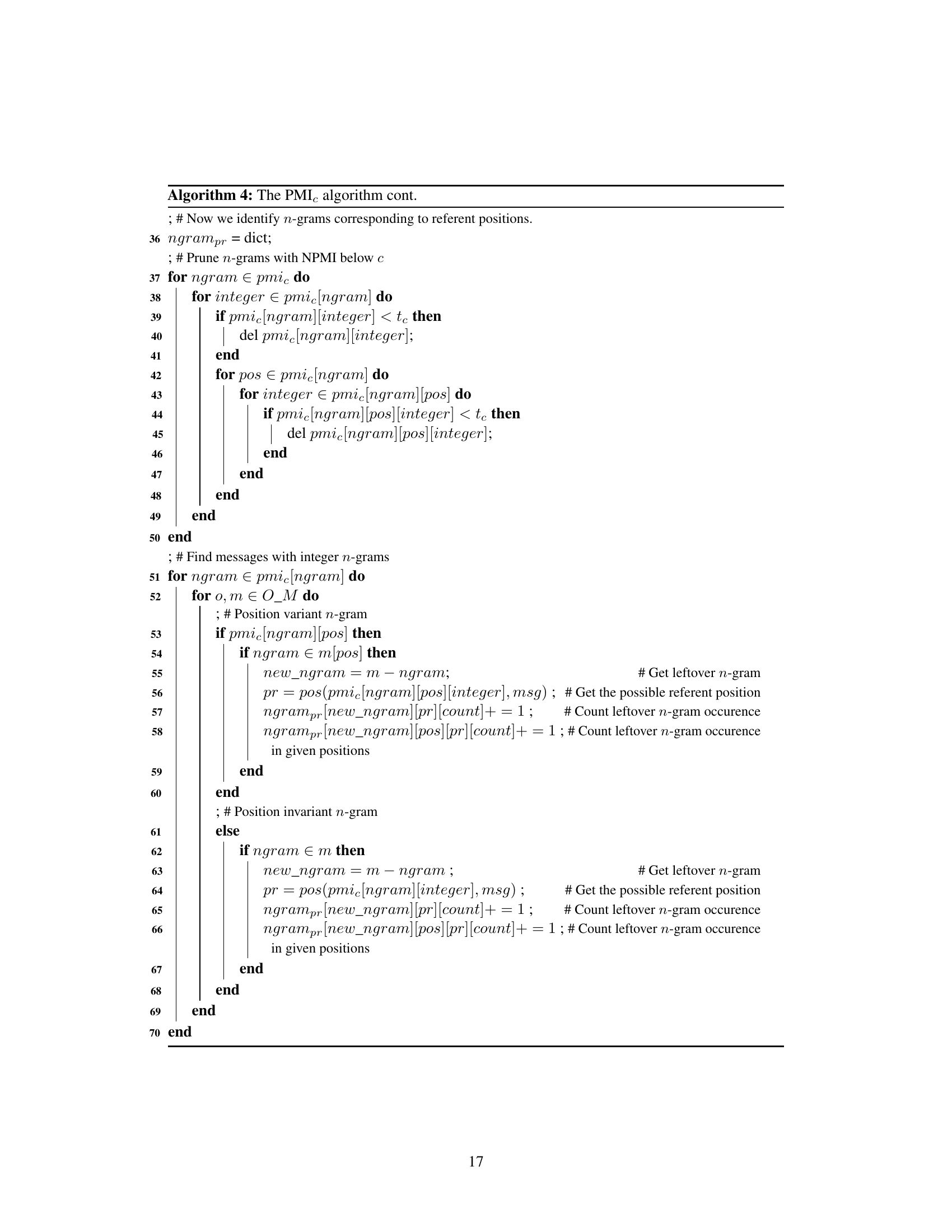

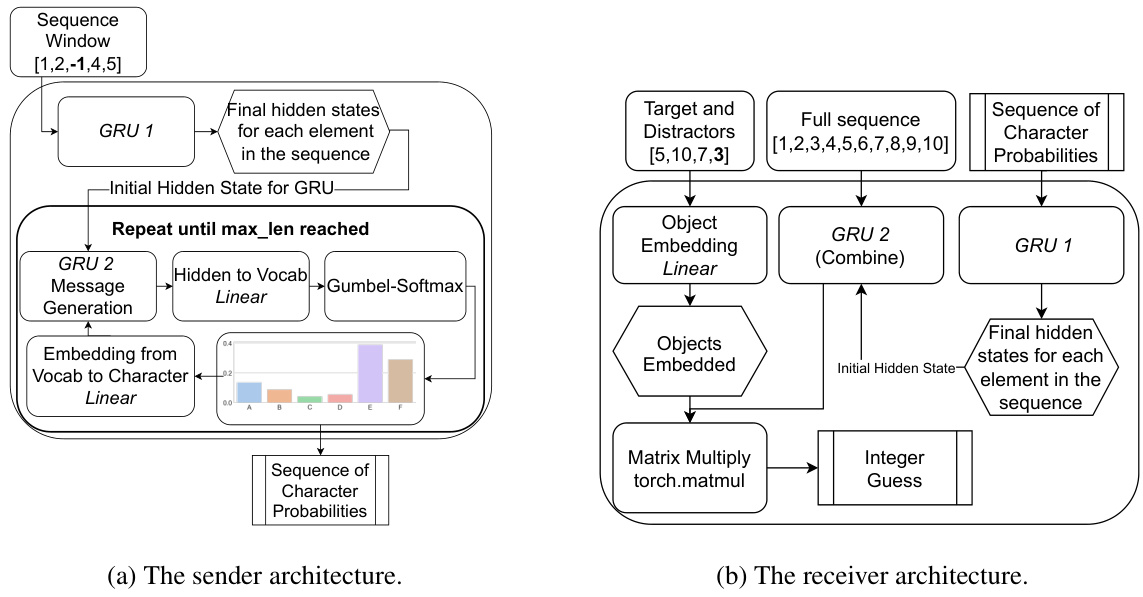

This table summarizes the frequency of different message types (non-compositional positional, non-compositional positional reserved, non-compositional integer, compositional integer, and compositional positional) that emerged across multiple runs of the agent communication experiments. It shows both the percentage of experimental runs where each message type emerged and the percentage of all messages in those runs that belonged to that type. This gives insights into the prevalence and relative importance of different communication strategies used by the agents.

In-depth insights#

Emergent Spatial Lang#

The concept of ‘Emergent Spatial Lang’ proposes a fascinating area of research within the field of artificial intelligence and language acquisition. It explores how agents, through interaction and learning, can develop communication systems that incorporate spatial relationships. The emergence of spatial language features highlights the potential of agents to create systems of communication that are both efficient and easily interpretable. This has significant implications for building more human-like AI systems as spatial reasoning and communication are essential for human cognition. The core idea involves exploring the mechanisms by which agents learn to convey spatial information, building representations of their environment, and effectively communicating these representations to others. The ability to interpret this emergent language, whether through human analysis or machine learning techniques, represents a crucial element of the work. Future research in this area could focus on understanding the factors influencing the emergence of spatial language features and developing techniques for effectively leveraging such features in AI applications. The focus on interpretability is also valuable, providing insights into the internal representations and strategies agents use for spatial communication, which allows for better understanding and control. Overall, ‘Emergent Spatial Lang’ presents a novel and intriguing direction for building more advanced and human-like AI systems.

NPMI for Semantics#

The concept of using NPMI (Normalized Pointwise Mutual Information) for semantic analysis in emergent communication is a powerful one. NPMI excels at identifying collocations, which are frequently occurring word pairings that suggest semantic relationships. By applying NPMI to segments of emergent messages, researchers can uncover potential syntactic structures and even discover the meaning of individual message parts. This approach moves beyond simpler methods that rely solely on message-meaning pairs, allowing for a richer understanding of the language’s underlying structure. The application of NPMI is particularly useful in this context because it handles the complexities of emergent languages, where relationships may not be straightforward or easily labeled. The use of NPMI thus provides crucial insights into the compositionality and semantics of emergent languages. It reveals whether messages are monolithic (single-meaning units) or compositional (carrying meaning through constituent parts). It can even pinpoint how position within a message contributes to meaning. This nuanced analysis ultimately aids in interpreting and understanding the emergent language, making it more accessible to human researchers and fostering better comprehension of how language develops in artificial agents.

Interpretable Deixis#

Interpretable deixis, in the context of emergent communication, signifies the crucial ability of an artificial language to incorporate and convey spatial and temporal references. This is a significant step beyond simple referential communication, moving towards more human-like linguistic capabilities. Successful interpretable deixis implies that the generated language is not just efficient for communication between agents, but also understandable and translatable by humans. Achieving this requires a careful consideration of the environmental setup, reward mechanisms and the method for analyzing the emergent language. Methods like Normalized Pointwise Mutual Information (NPMI) help uncover the underlying structure of the artificial language, allowing researchers to identify compositional and non-compositional elements that represent spatial relationships. This analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of how agents learn to use context and relative positioning to express meaning, bringing us closer to building truly interpretable and generalizable AI communication systems. The challenge lies in ensuring the robustness and generalizability of these systems, considering factors like dataset size and the diversity of spatial configurations.

Compositional Meaning#

The concept of “Compositional Meaning” in the context of emergent communication, as explored in the provided research paper, centers on the ability of agents to create meaning by combining simpler elements, or “words,” rather than relying solely on non-compositional, holistic messages. The key finding is that the agents do indeed develop compositional language, moving beyond a simple association between single signals and meanings. This compositionality is not purely syntactic, however, meaning there isn’t a rigid, rule-based structure governing how the elements combine, as in human language. Instead, the combination of elements creates meaning through a more flexible and emergent process, possibly involving both positional context and the elements’ individual meaning. Further research should focus on determining the precise mechanisms of this compositional process, as the current findings demonstrate the existence of compositionality without fully explaining its nature. This is crucial to understanding the limitations and potential of such emergent systems and their comparison to human linguistic abilities. The ability of humans to interpret the emergent language further highlights the potential for creating interpretable and efficient communication systems.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more complex environments and tasks. Extending the referential game to incorporate dynamic scenes where object positions change would significantly challenge the agents, potentially leading to richer, more sophisticated spatial communication strategies. Investigating alternative communication architectures, beyond the EGG model employed here, could reveal how different approaches handle spatial referencing. The incorporation of visual attention mechanisms could allow agents to focus on relevant parts of the scene, improving communication efficiency and potentially leading to a more nuanced understanding of spatial relationships. Furthermore, exploring the scalability of the method to larger vocabularies and longer sequences is crucial for real-world applicability. A deeper dive into the compositionality of emergent spatial language could reveal insights into syntactic structures and grammar, paving the way for a more complete understanding of how these languages emerge. Finally, cross-linguistic analysis comparing different emergent languages trained under varying conditions could highlight universal principles governing spatial communication, enriching our understanding of both human and artificial language development.

More visual insights#

More on tables

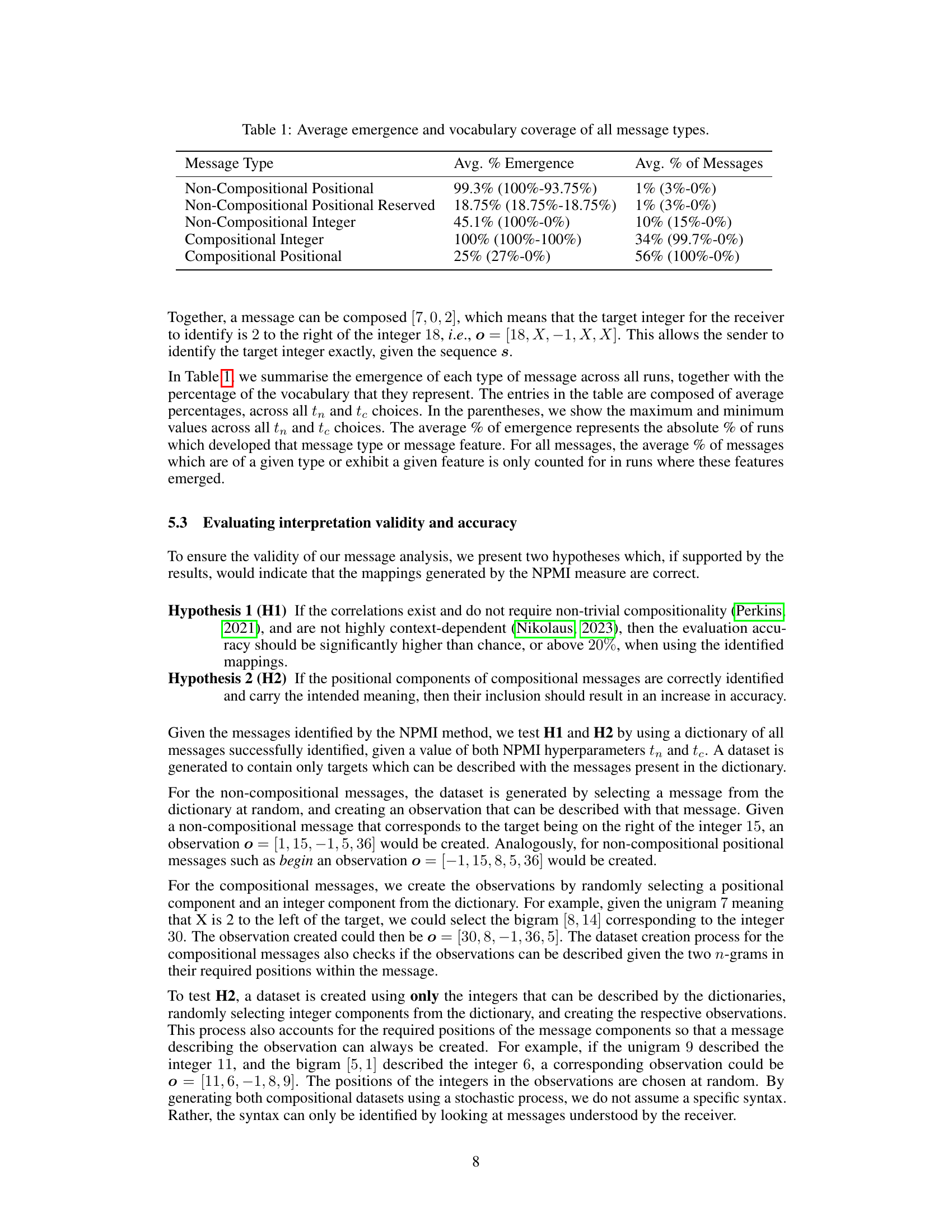

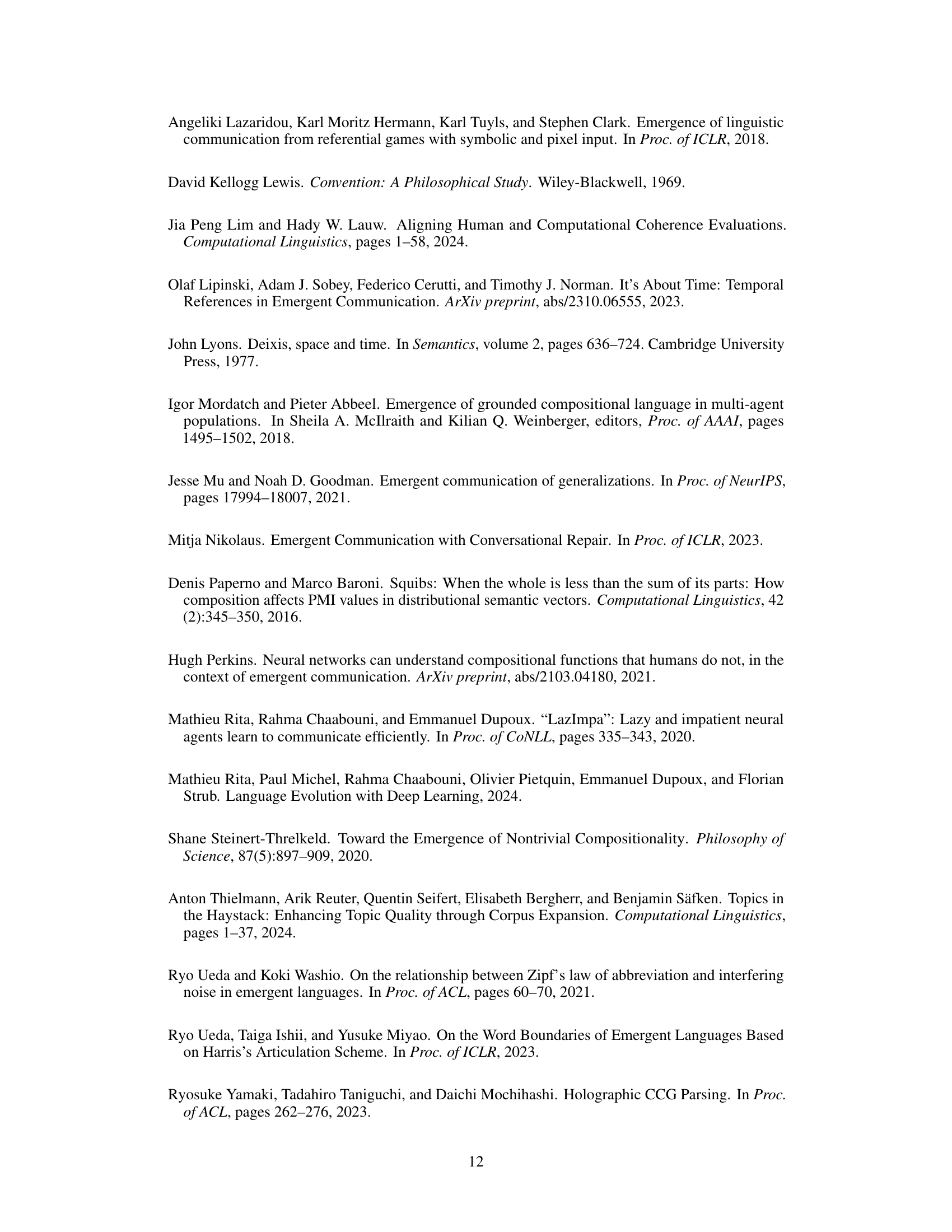

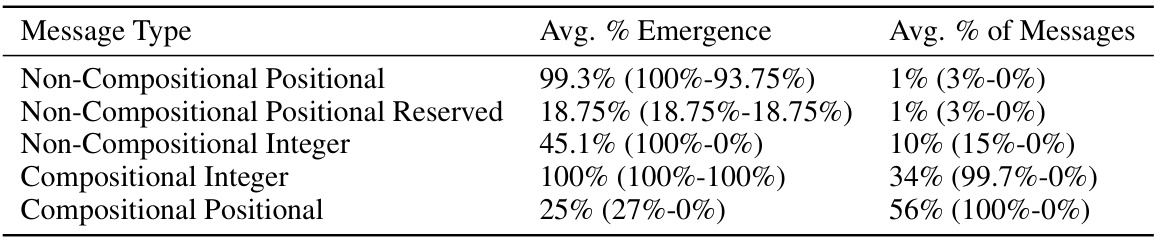

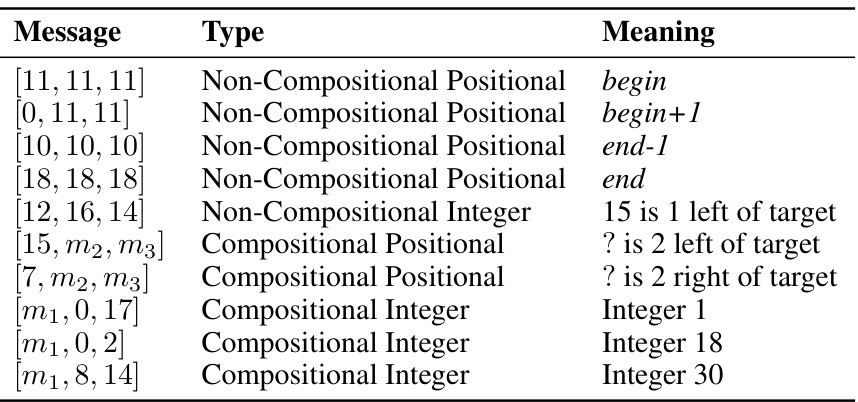

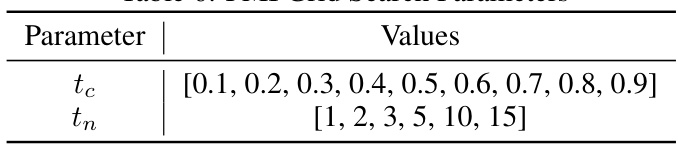

This table shows the accuracy improvements achieved by using a dictionary created with the NPMI method. The dictionary maps messages to their meanings (e.g., spatial relationships, specific integers). The accuracy is measured for different types of messages: non-compositional positional (referring to positions like ‘begin’ or ’end’), non-compositional integer (referring to a specific integer in a specific position), compositional-NP (only containing identified integer components), and compositional-P (containing both integer and positional components). The table indicates that using the NPMI-based dictionary significantly improves accuracy, particularly for non-compositional positional messages, suggesting that these messages are interpreted with high accuracy.

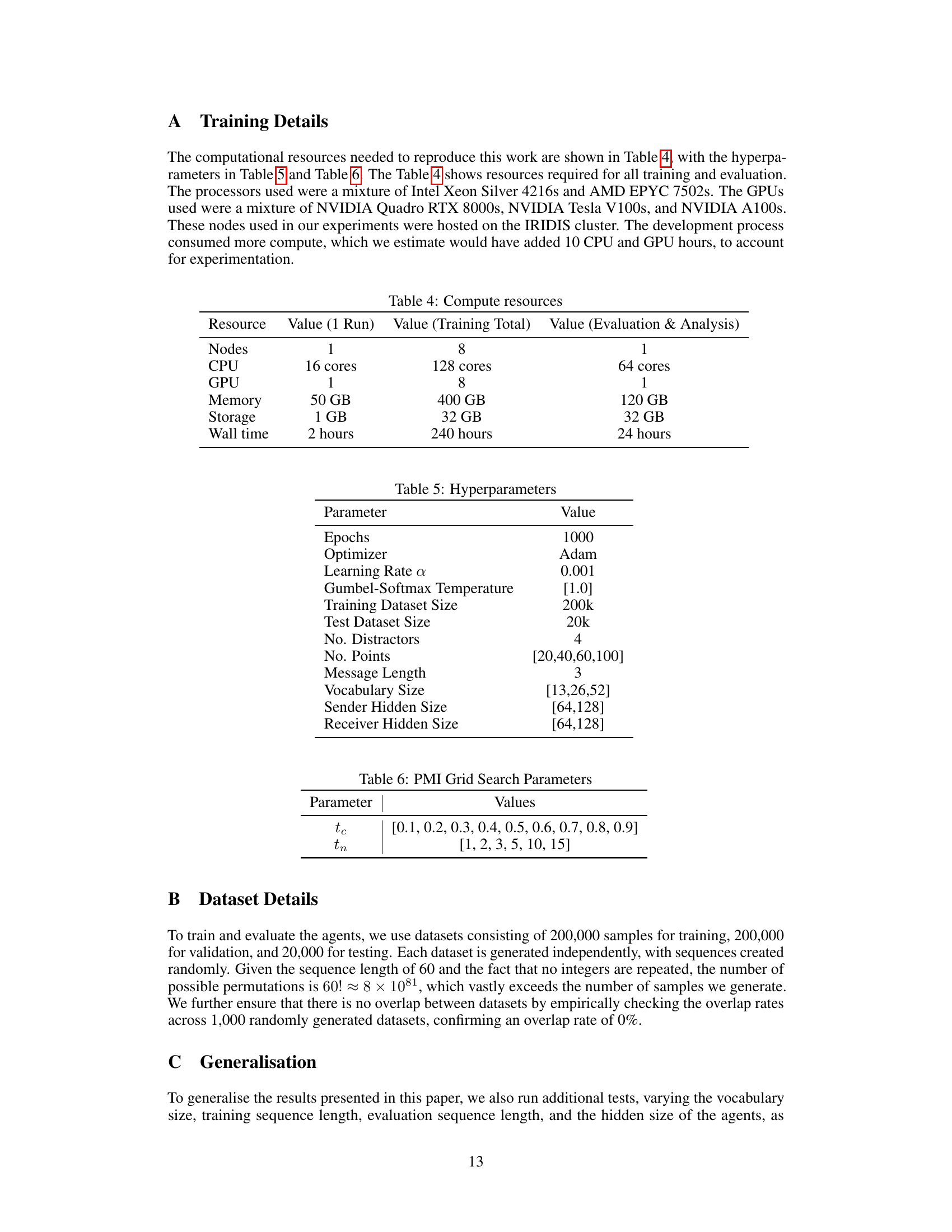

This table presents a sample dictionary that maps emergent communication messages to their corresponding meanings in human-interpretable terms. The messages, represented as integer triplets, were produced by the agents during the experiment. The dictionary provides a translation, illustrating the correspondence between the symbolic messages generated by the agents and their spatial interpretations based on the context of the observation and position of the target.

This table presents a summary of the emergence rates and vocabulary coverage for different types of messages used by the agents. It shows the average percentage of runs where each message type emerged, along with the percentage of the overall vocabulary that each type represents. The data helps illustrate the prevalence of different communication strategies used by the agents in the experiment.

This table summarizes the emergence and vocabulary coverage of different message types in the experiments. It shows the percentage of runs where each message type emerged, along with the percentage of the overall vocabulary that each type represents. Message types are categorized as non-compositional positional (referring to the position of the target integer, e.g., beginning or end of the sequence), non-compositional integer (directly referring to a specific integer), compositional integer (referring to a specific integer using a combination of tokens), and compositional positional (referring to a combination of position and integer information). The table provides insights into how frequently the agents used each type of message and the relative importance of each type in their communication strategy.

This table shows the accuracy improvements achieved when using a dictionary generated from the NPMI analysis to query the receiver agent. It breaks down accuracy by message type, including non-compositional positional (e.g., begin, end), non-compositional integer (monolithic messages indicating both position and integer), compositional-NP (only identified integer components), and compositional-P (both integer and positional components). The results demonstrate the impact of including positional information in the message interpretation process.

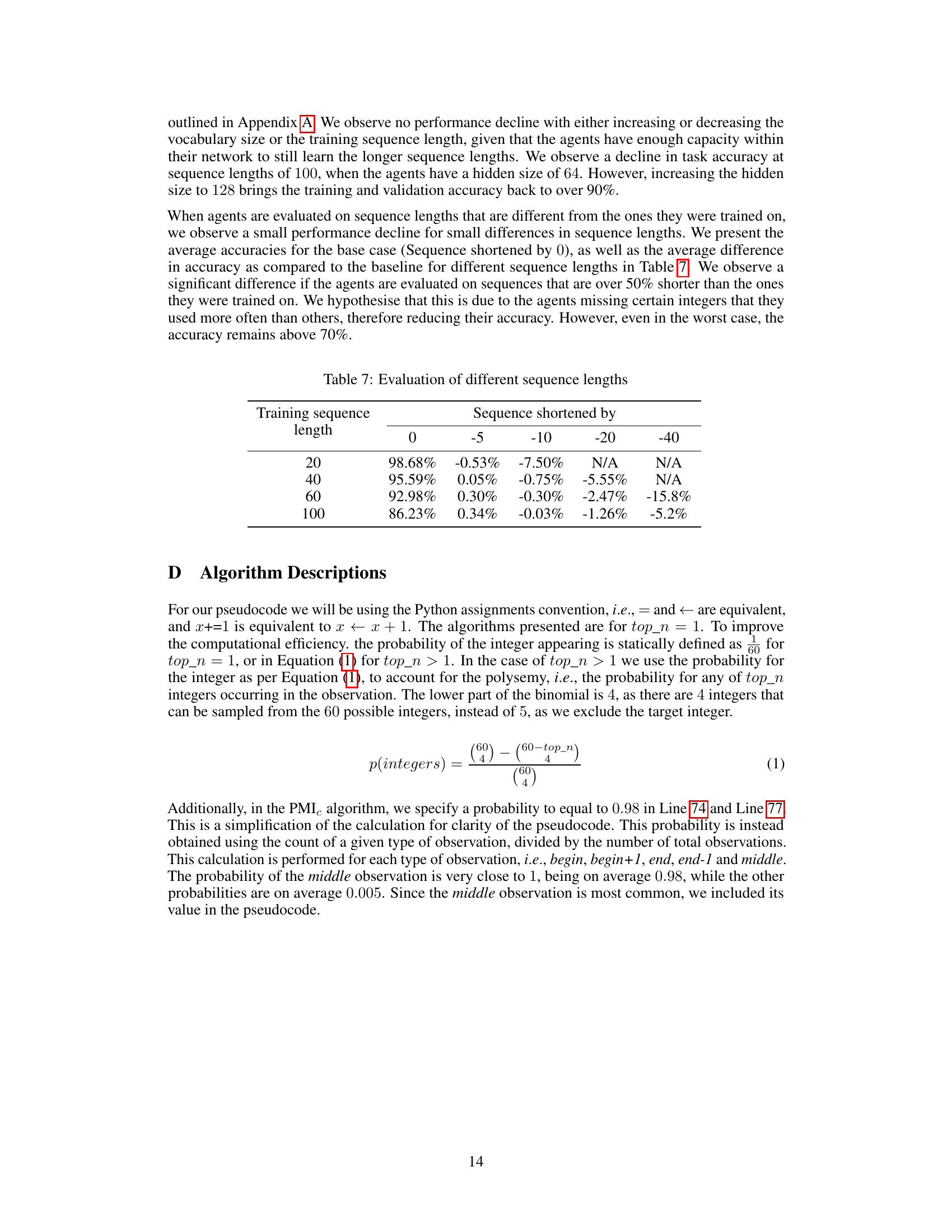

This table presents the results of evaluating the agents’ performance on sequences of different lengths. The ‘Training sequence length’ column indicates the length of sequences used during training. The remaining columns show the average accuracy of the agents when tested on sequences shortened by the specified amounts. A negative value indicates a shorter testing sequence than the training sequence, demonstrating the model’s generalization ability across various sequence lengths.

Full paper#