↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning tasks involve custom objectives, often non-differentiable and hard to optimize. Current differentiable relaxations can suffer from vanishing or exploding gradients, hindering neural network training. This often occurs when using algorithms as parts of the loss functions. This paper addresses this by introducing a novel approach called “Newton Losses” which exploits the second-order information of these complex loss functions, typically obtained via Hessian or Fisher matrix.

Newton Losses locally approximates the non-convex loss functions with a quadratic function, effectively creating a locally convex surrogate loss. This surrogate loss function is optimized to improve performance with gradient descent. Experiments on sorting and shortest-path benchmarks show consistent performance improvements for existing methods, especially for those that suffer from vanishing/exploding gradients. The method’s computational efficiency is a key advantage, making it practical for various applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with non-convex and hard-to-optimize algorithmic losses in neural networks. It offers a novel and efficient method to improve training performance, opening new avenues for tackling complex, weakly-supervised learning problems. The proposed approach of improving loss functions themselves before training neural networks is valuable to a broad audience, bridging the gap between algorithms and deep learning. It’s particularly relevant to fields like ranking, shortest path problems and beyond, offering immediate practical benefits.

Visual Insights#

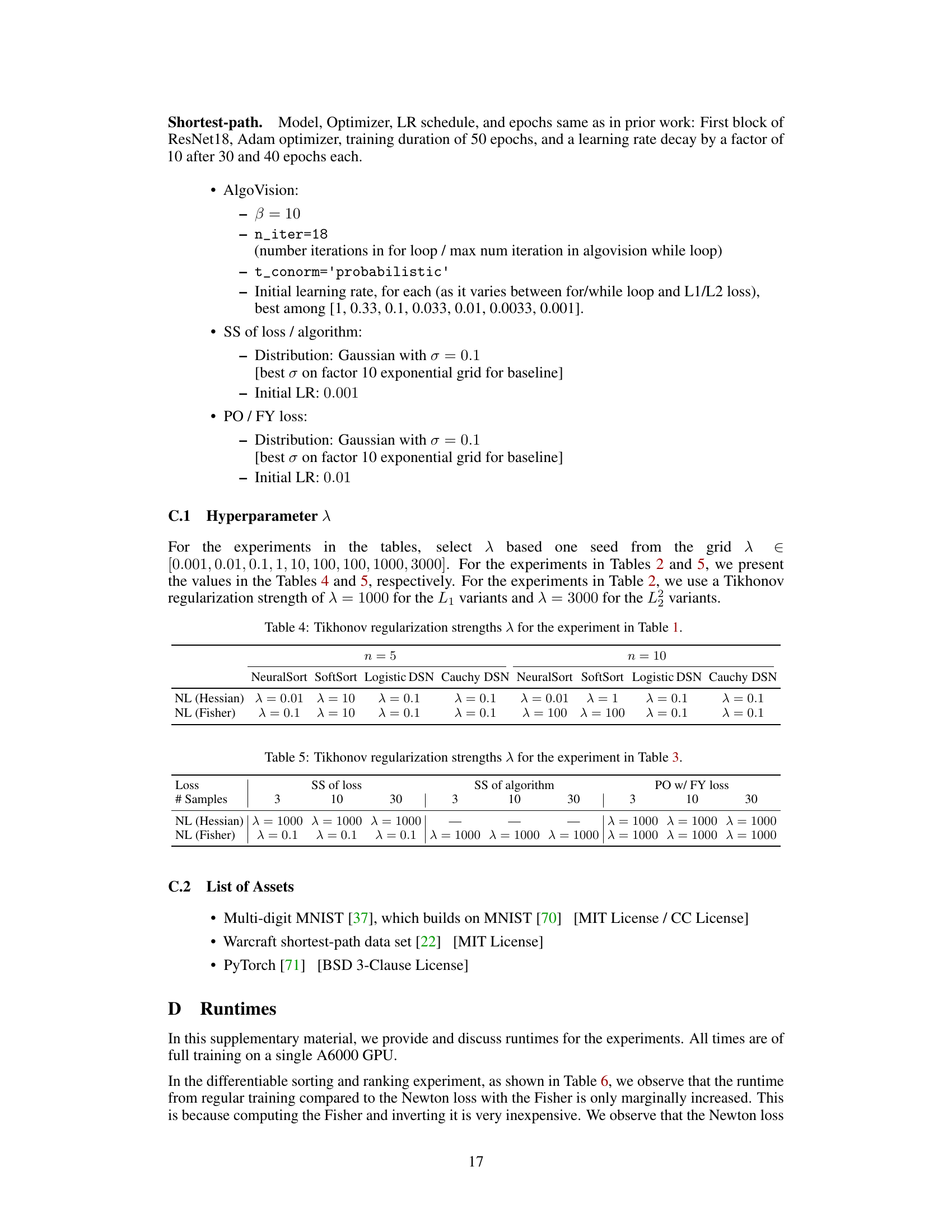

This figure illustrates the ranking supervision task using differentiable sorting algorithms. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) processes a set of four-digit MNIST images, generating a scalar value for each image. These scalars are then fed into a differentiable ranking algorithm (e.g., NeuralSort, SoftSort, or a Differentiable Sorting Network), which outputs a differentiable permutation matrix representing the predicted ranking. This predicted permutation matrix is finally compared against the ground truth permutation matrix using a cross-entropy loss function (LCE). The goal is to train the CNN such that it produces scalars that lead to a predicted ranking that closely matches the ground truth.

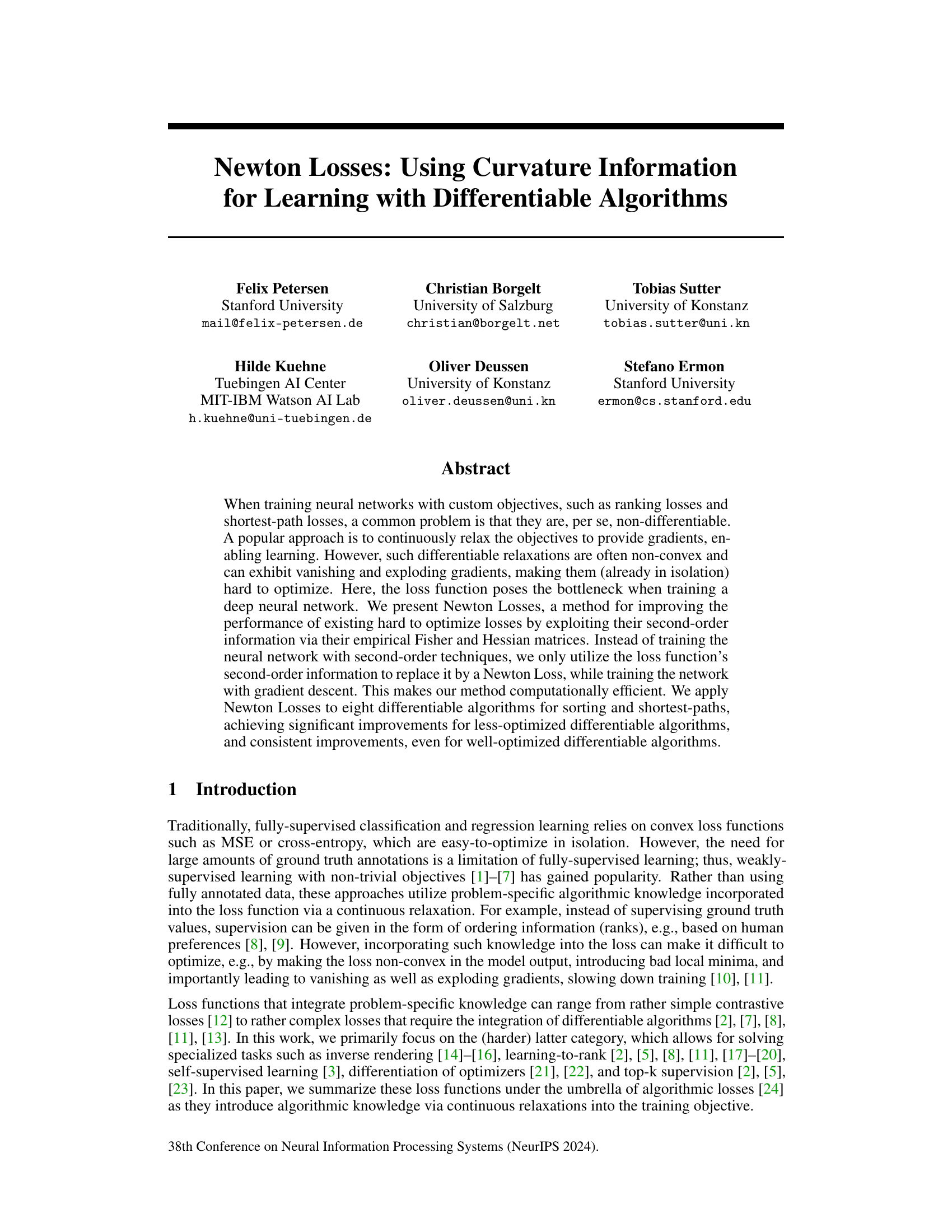

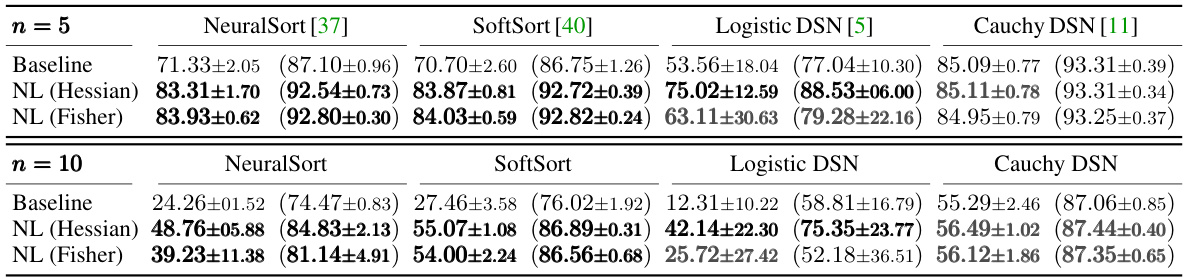

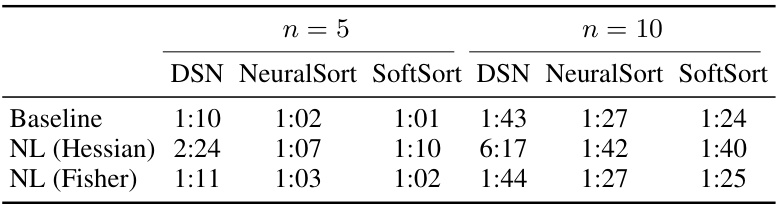

This table presents the results of ranking supervision experiments using four different differentiable sorting algorithms (NeuralSort, SoftSort, Logistic DSN, and Cauchy DSN). For each algorithm, the baseline performance and performance with two variants of Newton Losses (Hessian-based and Fisher-based) are shown for datasets with 5 and 10 elements to be ranked. The metric is the percentage of rankings correctly identified, with the percentage of correctly ranked individual elements shown in parentheses. Statistically significant improvements are highlighted in bold black, while improvements that are not statistically significant are shown in bold gray.

In-depth insights#

Newton Loss Method#

The proposed “Newton Loss Method” offers a novel approach to enhance the training of neural networks using custom, often non-differentiable objectives. It cleverly addresses the optimization challenges posed by such loss functions by leveraging second-order information. Instead of directly applying computationally expensive second-order optimization techniques to the entire neural network, the method focuses on locally approximating the loss function using a quadratic Taylor expansion. This approximation, refined through Hessian or empirical Fisher matrix calculations, generates a “Newton Loss” that’s easier to optimize using standard gradient descent. This strategy is particularly beneficial for algorithms where the loss function presents a computational bottleneck during training. The approach’s effectiveness is demonstrated by consistent performance improvements across various differentiable algorithms for sorting and shortest-path problems, showcasing its broad applicability and potential to significantly improve the training efficiency and accuracy of models utilizing complex, non-convex objectives. The key strength lies in its computational efficiency, as it avoids the high cost associated with second-order optimization of the entire neural network. Furthermore, the method’s flexibility allows for the use of either Hessian or empirical Fisher matrix information, adapting to situations where Hessian computation might be difficult or impractical.

Algorithmic Losses#

The concept of “Algorithmic Losses” in machine learning represents a significant shift from traditional supervised learning paradigms. Instead of relying solely on ground truth labels, these losses integrate problem-specific algorithmic knowledge directly into the training objective. This allows for tackling tasks previously intractable with standard loss functions like MSE or cross-entropy. Continuous relaxations of inherently non-differentiable algorithms are crucial here, enabling gradient-based optimization. However, this approach introduces challenges, including non-convexity, vanishing/exploding gradients, and the presence of poor local minima, hindering optimization efficiency. The innovation lies in leveraging algorithmic knowledge to design the loss function itself, leading to a more powerful yet potentially more difficult optimization landscape.

Empirical Fisher#

The concept of “Empirical Fisher” in the context of optimizing loss functions within neural networks is a crucial one. It offers a computationally efficient alternative to using the full Hessian matrix when calculating second-order information. The Hessian, while providing superior information about the loss landscape’s curvature, is often prohibitively expensive to compute for large neural networks. The Empirical Fisher, derived from the observed gradients, provides an approximation of curvature that can be significantly less computationally demanding. This approximation is particularly useful for non-convex and hard-to-optimize loss functions arising from the integration of differentiable algorithms, where the true Hessian might be unavailable or impractical. The tradeoff, however, lies in the accuracy of the approximation; while computationally efficient, the Empirical Fisher may sacrifice some precision compared to the full Hessian. The use of regularization techniques, like Tikhonov regularization, are often employed to stabilize the inverse of the approximated Fisher matrix. This is vital in cases of ill-conditioning, which can occur if the eigenvalues are close to zero. Overall, the method represents a balance between computational efficiency and optimization performance. Its effectiveness is contingent on the characteristics of the loss function and the specific application.

Benchmark Results#

Benchmark results are crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of Newton Losses. The paper likely presents results on established benchmarks for ranking and shortest-path problems, comparing the performance of Newton Losses against existing state-of-the-art methods. Key aspects to look for include quantitative metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall), statistical significance testing to confirm improvements aren’t due to chance, and analysis of different variants of Newton Losses (Hessian-based vs. Fisher-based) to understand their relative strengths and weaknesses across various scenarios. Ablation studies, investigating the impact of hyperparameters, would also provide valuable insights. Finally, a discussion of the computational cost of Newton Losses and how it scales with problem size is essential for practical applicability.

Future Extensions#

Future research could explore extensions to non-convex loss functions, investigating alternative methods beyond quadratic approximations to better handle the complexities of algorithmic losses. The effectiveness of Newton Losses with different optimization algorithms beyond gradient descent warrants further study. Additionally, research into more efficient Hessian or Fisher matrix estimation techniques is crucial for scalability, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data or complex algorithmic procedures. Finally, exploring applications of Newton Losses in other areas of weakly supervised learning and expanding the evaluation to a wider range of algorithmic problems will solidify its practical impact and uncover its full potential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

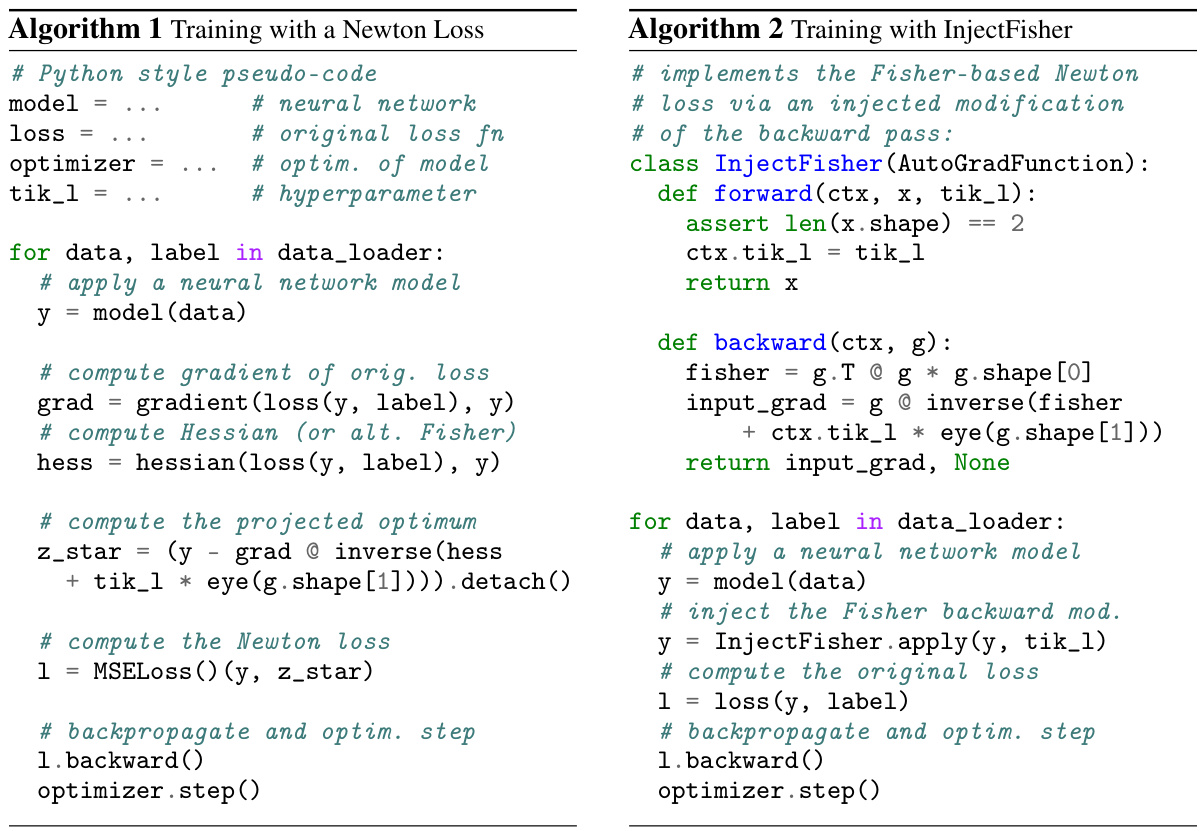

This figure shows an example of the Warcraft shortest-path benchmark used in the paper. The left panel displays a 12x12 terrain map (input data). The center panel shows the hidden, unsupervised ground truth cost embedding for the map, which is the underlying cost for calculating shortest paths and is not available during training. The right panel depicts the ground truth shortest path, which is the supervised target for the model to learn to predict.

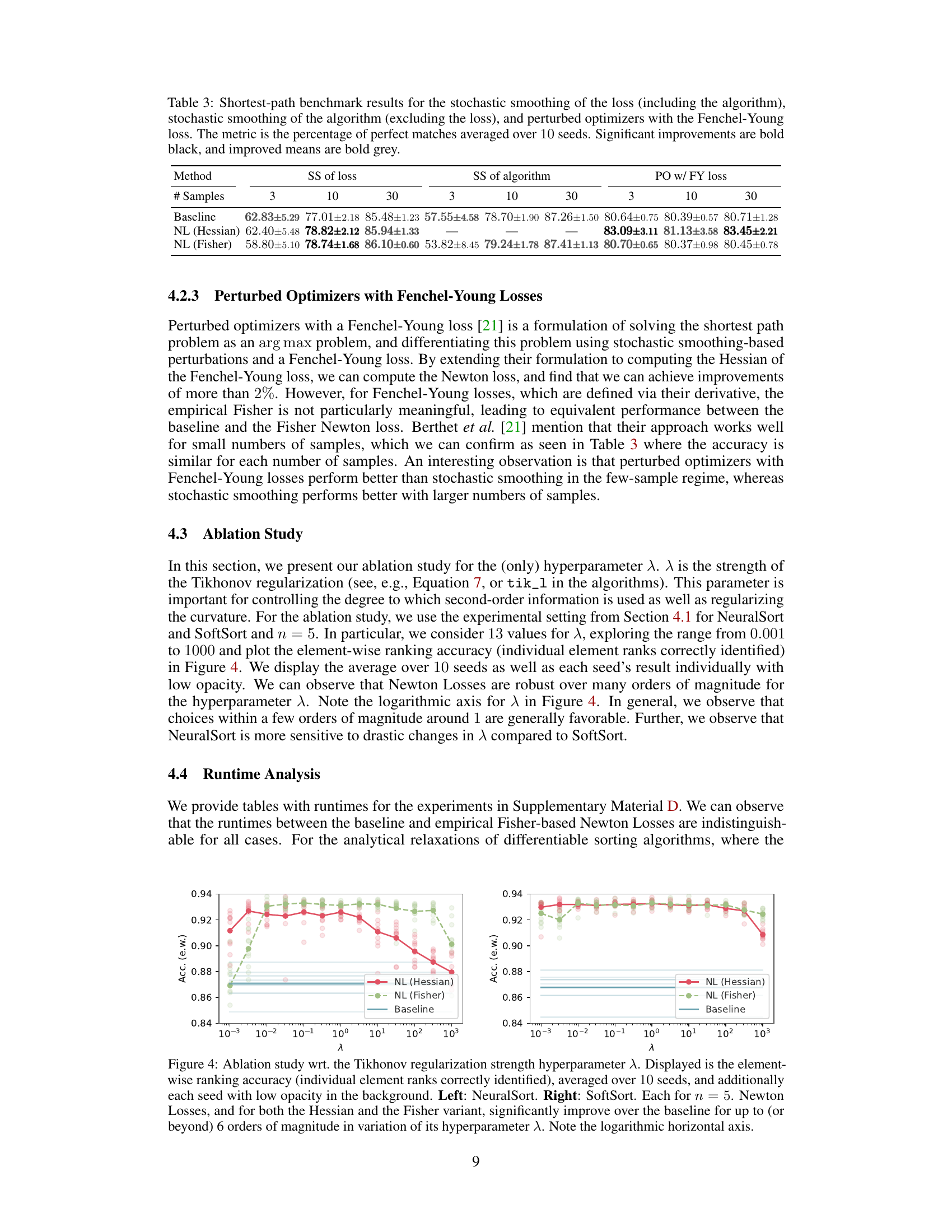

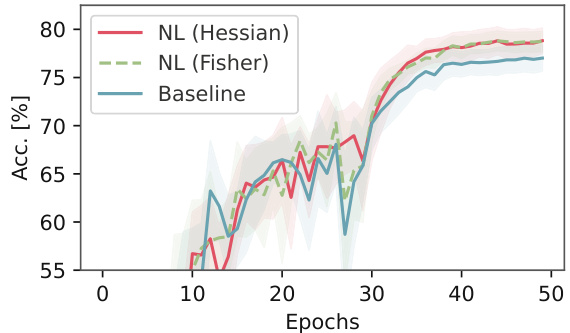

This figure shows the test accuracy (percentage of perfect matches) over 50 epochs for the stochastic smoothing (‘SS of loss’) method with 10 samples on the Warcraft shortest-path benchmark. The lines represent the mean accuracy across multiple runs, and the shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals, indicating the variability of the results. The plot compares the performance of the baseline method with the Hessian-based and Fisher-based Newton Loss variants.

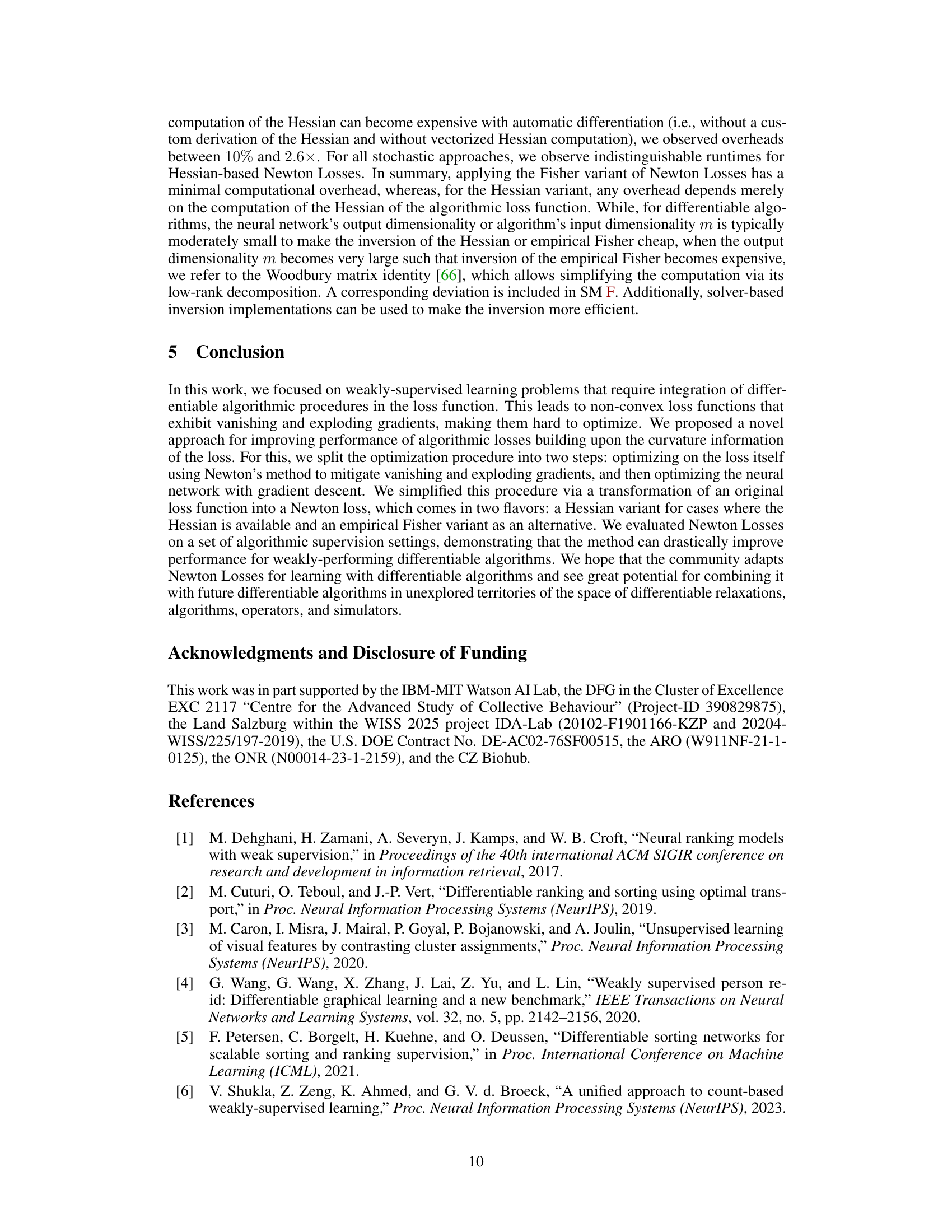

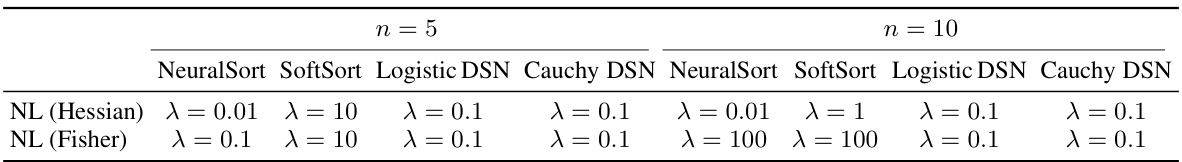

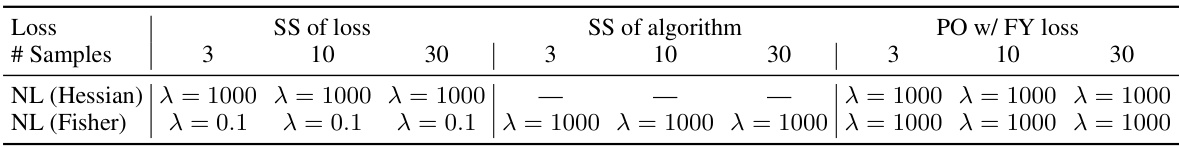

This ablation study shows the effect of the Tikhonov regularization strength (λ) on the element-wise ranking accuracy for NeuralSort and SoftSort (n=5). The plots show that Newton Losses (both Hessian and Fisher variants) consistently outperform the baseline across a wide range of λ values, demonstrating robustness to this hyperparameter.

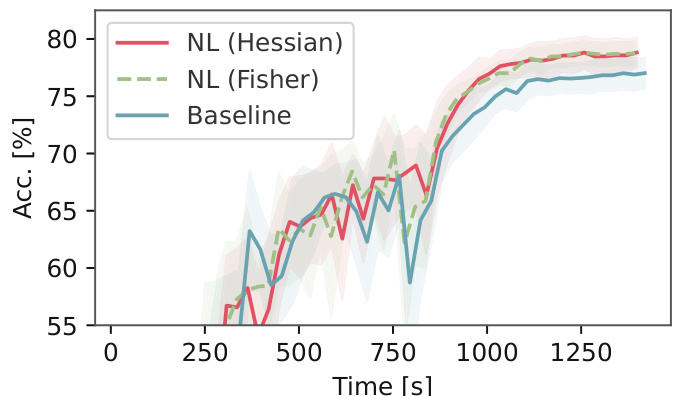

This figure shows the test accuracy (percentage of perfect matches) over time (in seconds) for the ‘SS of loss’ method with 10 samples on the Warcraft shortest-path benchmark. Three lines are plotted: one for the baseline method and two for variations using Newton Losses (Hessian and Fisher). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals, showing the variability in the results across multiple runs.

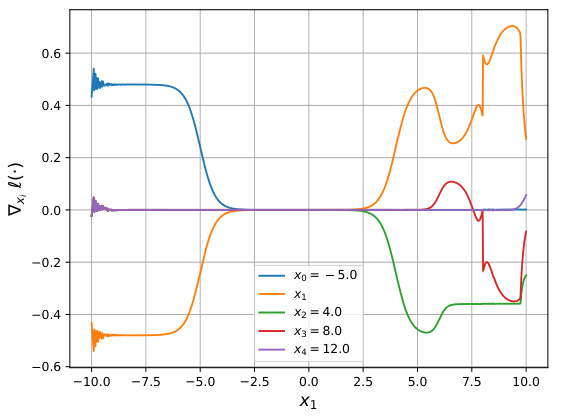

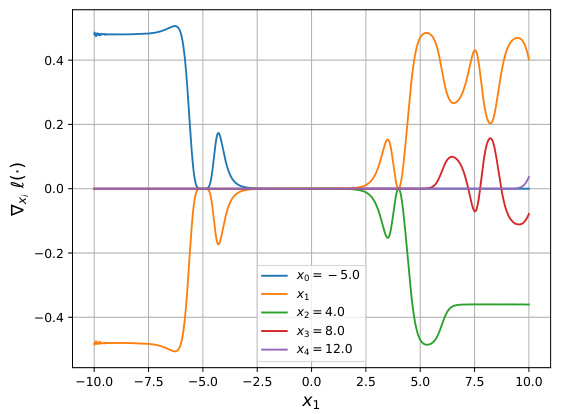

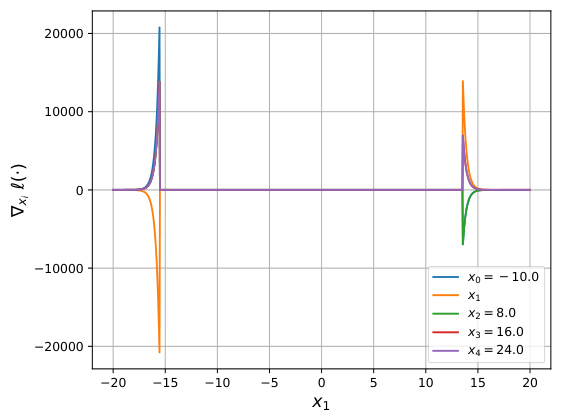

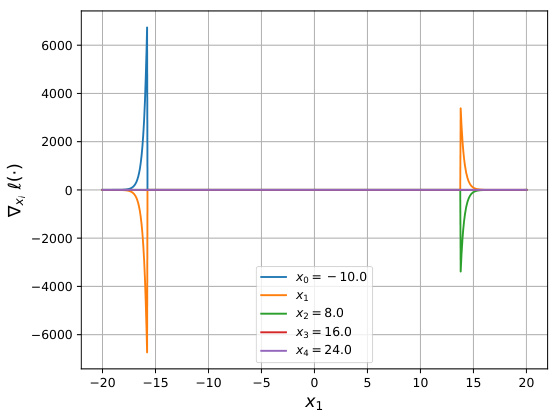

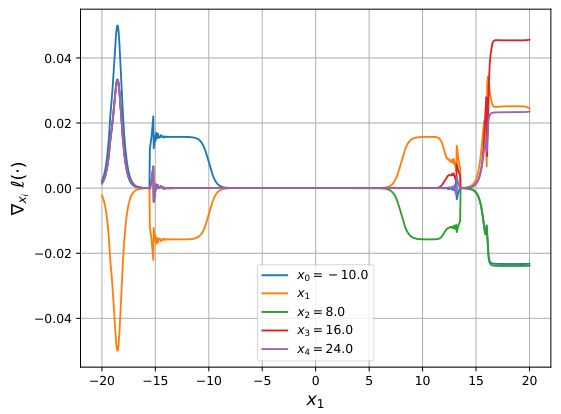

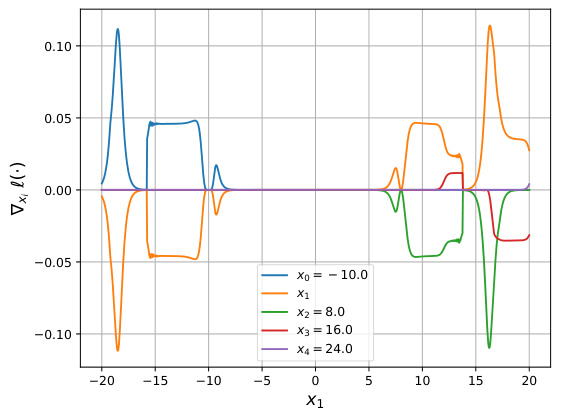

The figure shows gradient visualizations for NeuralSort and Logistic DSN, comparing the original gradients and the gradients after applying Newton Losses (using empirical Fisher). It demonstrates how Newton Losses mitigate issues with exploding gradients and chaotic gradient behavior, particularly when inputs are far apart.

This figure visualizes gradients of NeuralSort and Logistic DSN loss functions, highlighting the issue of exploding gradients when inputs are far apart. It then shows how the empirical Fisher Newton Loss mitigates this problem, leading to smoother, more manageable gradients.

Figure 6 shows gradient visualizations for NeuralSort and Logistic DSN, illustrating how Newton Loss addresses exploding gradients and chaotic behavior, especially when inputs are far apart.

This figure visualizes the gradients of NeuralSort and Logistic DSN losses, highlighting the issue of exploding gradients when inputs are distant. It then shows how the empirical Fisher Newton Loss mitigates this problem.

The figure shows the gradients of NeuralSort and Logistic DSN losses, demonstrating the issue of exploding gradients when inputs are far apart. It also compares these gradients to those produced using the empirical Fisher Newton Loss, illustrating its effectiveness in mitigating this problem.

This figure shows gradient plots for NeuralSort and Logistic DSN, demonstrating the issues of exploding gradients with these algorithms. The plots visualize how the gradients behave in relation to input values (x1). The addition of Newton Losses is shown to mitigate the exploding gradients, demonstrating the improved stability and performance.

More on tables

This table presents the results of ranking supervision experiments using four different differentiable sorting algorithms: NeuralSort, SoftSort, Logistic DSN, and Cauchy DSN. The table compares the baseline performance of each algorithm with the performance achieved using Hessian-based and Fisher-based Newton Losses. The metric used is the percentage of rankings correctly identified, averaged over 10 random seeds, with the percentage of correctly identified individual element ranks provided in parentheses. Statistically significant improvements are highlighted in bold black, while improvements that are not statistically significant are highlighted in bold gray.

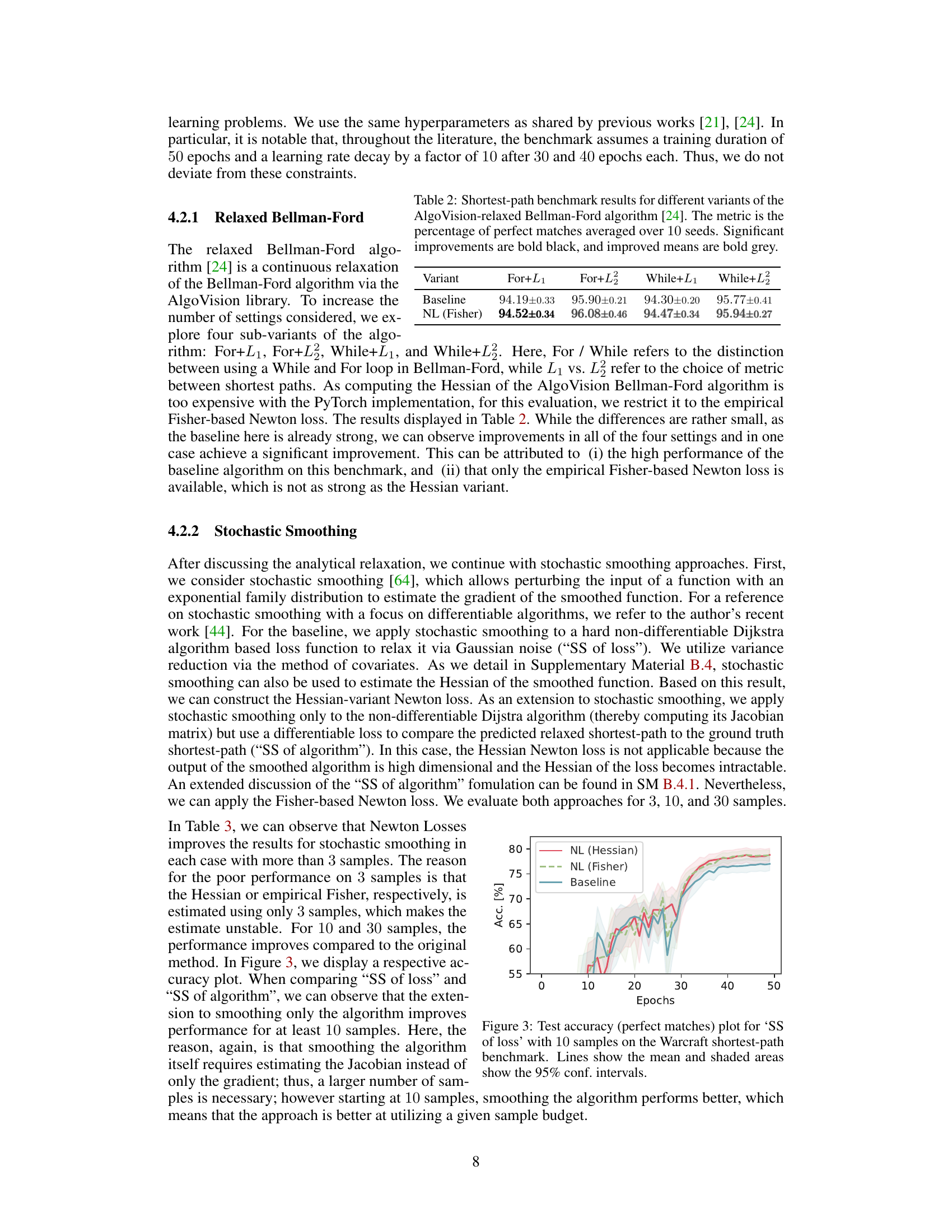

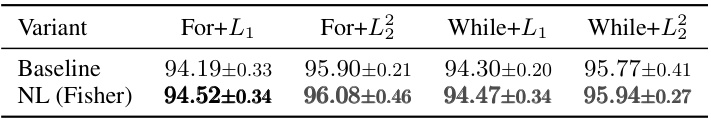

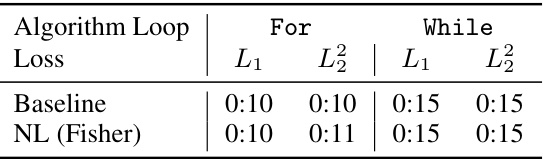

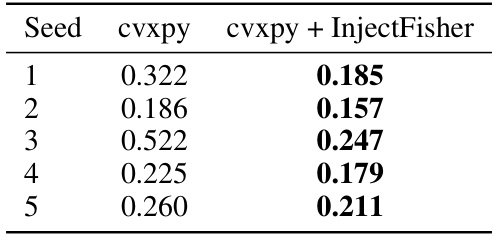

This table presents the results of applying Newton Losses (specifically the Fisher variant) to four variations of the Relaxed Bellman-Ford algorithm on the Warcraft shortest-path benchmark. Each variation differs in loop structure (For or While loop) and loss function (L1 or L2). The metric used is the percentage of perfectly predicted shortest paths, averaged across 10 random seeds. The table shows that Newton Losses consistently improves the performance, particularly notable in the ‘For+L2’ variant, showing significant improvement.

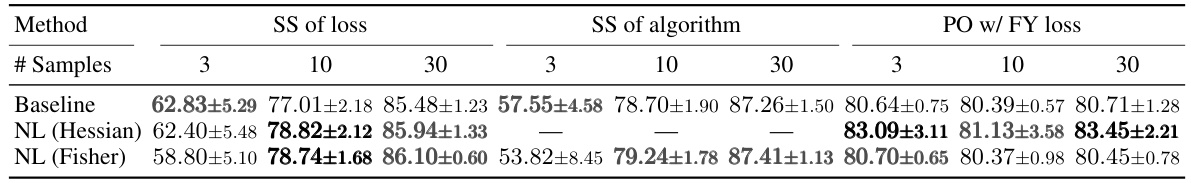

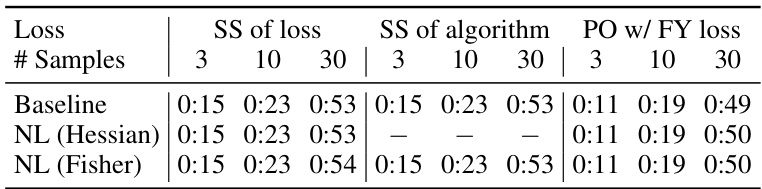

This table presents the results of three different shortest-path algorithms on the Warcraft benchmark. The algorithms are Stochastic Smoothing of the Loss, Stochastic Smoothing of the Algorithm, and Perturbed Optimizers with Fenchel-Young Losses. Each algorithm is tested with 3, 10, and 30 samples. The table shows the baseline performance and the performance improvement achieved by using Hessian-based and Fisher-based Newton Losses. The metric used is the percentage of perfectly matched shortest paths.

This table presents the results of ranking supervision experiments using various differentiable sorting algorithms. The key metric is the percentage of rankings correctly identified, averaged over 10 different random seeds. The table compares baseline performance against the performance achieved using Hessian-based and Fisher-based Newton Losses. Statistically significant improvements are highlighted in bold black, while improvements that aren’t statistically significant are shown in bold grey. Results are shown for both n=5 and n=10 (number of items to be ranked).

This table presents the results of three different shortest-path algorithms on the Warcraft shortest-path benchmark. The algorithms are: Stochastic Smoothing of the loss, Stochastic Smoothing of the algorithm, and Perturbed Optimizers with Fenchel-Young losses. Each algorithm is tested with three different numbers of samples (3, 10, and 30). The table shows the percentage of perfect matches achieved by each algorithm and the statistical significance of the improvements compared to the baseline.

This table presents the results of ranking supervision experiments using various differentiable sorting algorithms. The main metric is the percentage of rankings correctly identified, averaged over ten different random seeds for each algorithm and its variations (with and without Newton Losses). The table also shows the percentage of individual element ranks correctly identified. Significant improvements (p<0.05) achieved by using Newton Losses are highlighted in bold black, while improvements that are not statistically significant are shown in bold gray. The algorithms compared are NeuralSort, SoftSort, Logistic DSN, and Cauchy DSN, each with baseline performance and Hessian and Fisher-based Newton Loss variations.

This table presents the results of applying Newton Losses to four variants of the AlgoVision-relaxed Bellman-Ford algorithm for shortest-path prediction. The performance metric is the percentage of perfect matches, averaged across 10 different random seeds. The table shows baseline performance and the improvement achieved using the empirical Fisher-based Newton Loss.

This table presents the results of applying Newton Losses to three different shortest-path algorithms: Stochastic Smoothing (of the loss and of the algorithm), and Perturbed Optimizers with Fenchel-Young Losses. The performance metric is the percentage of perfectly matched shortest paths, averaged across 10 different random seeds. The number of samples used in the stochastic methods is varied (3, 10, and 30). Significant performance improvements are highlighted in bold black, while general improvements are highlighted in bold gray.

This table presents the results of ranking supervision experiments using various differentiable sorting algorithms. The main metric is the percentage of rankings correctly identified, averaged over 10 random seeds. It compares baseline performance with that achieved using Hessian and Fisher variants of Newton Losses. Statistically significant improvements are highlighted.

Full paper#