↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

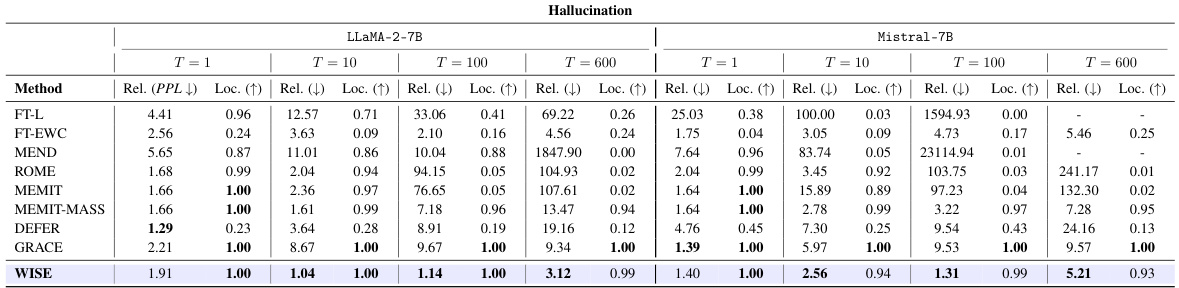

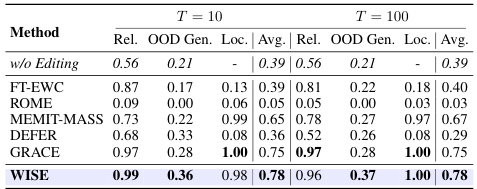

Large Language Models (LLMs) often generate incorrect or biased responses and require frequent updates to reflect the ever-changing real-world knowledge. Existing methods for updating LLMs struggle to maintain reliability (remembering past and present updates), locality (avoiding interference with pre-trained knowledge), and generalization (understanding edits beyond specific examples). This paper highlights this “impossible triangle” as a fundamental challenge in lifelong LLM editing.

To address this challenge, the researchers propose a novel method called WISE. WISE employs a dual-memory system: a main memory storing the original, pre-trained knowledge, and a side memory for storing the updated knowledge. A router decides which memory to use based on the query. A knowledge-sharding mechanism further ensures that continual updates don’t interfere with each other. Through extensive experiments, the researchers demonstrate that WISE significantly outperforms existing methods in various settings, breaking the “impossible triangle” and achieving improved reliability, locality, and generalization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on lifelong learning and large language model adaptation. It addresses a critical challenge of maintaining knowledge reliability, locality, and generalization during continual model updates, offering a novel dual-memory approach with significant performance improvements. The proposed method, WISE, opens new avenues for research in efficient knowledge management and continual learning for LLMs, impacting various applications like question answering and hallucination reduction.

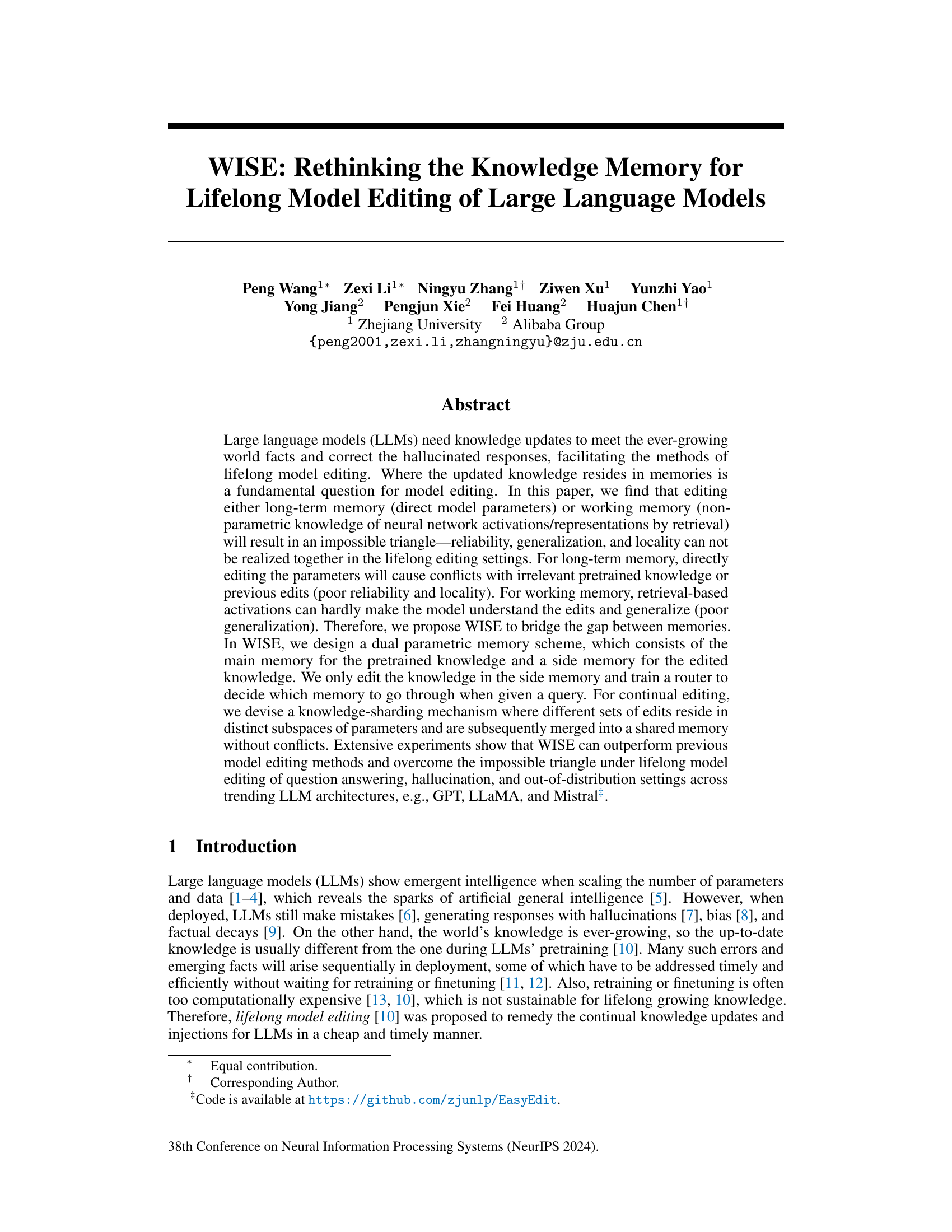

Visual Insights#

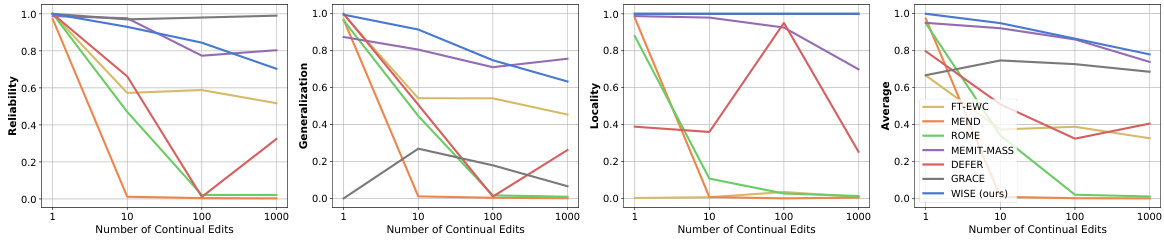

🔼 This figure shows the performance of different lifelong model editing methods across three key metrics: reliability, generalization, and locality. Methods are categorized into those editing long-term memory (directly modifying model parameters) and those using working memory (retrieving and modifying activations). The figure highlights that existing methods struggle to achieve high performance across all three metrics simultaneously, illustrating an ‘impossible triangle’. The proposed WISE method, however, demonstrates superior performance across all three metrics.

read the caption

Figure 1: Metric triangle among reliability, generalization, and locality. ZsRE dataset, number of continual edits T = 100, LLaMA-2-7B. Editing methods based on long-term memory (ROME and FT-EWC) and working memory (DEFER and GRACE) show the impossible triangle in metrics, while our WISE is leading in all three metrics.

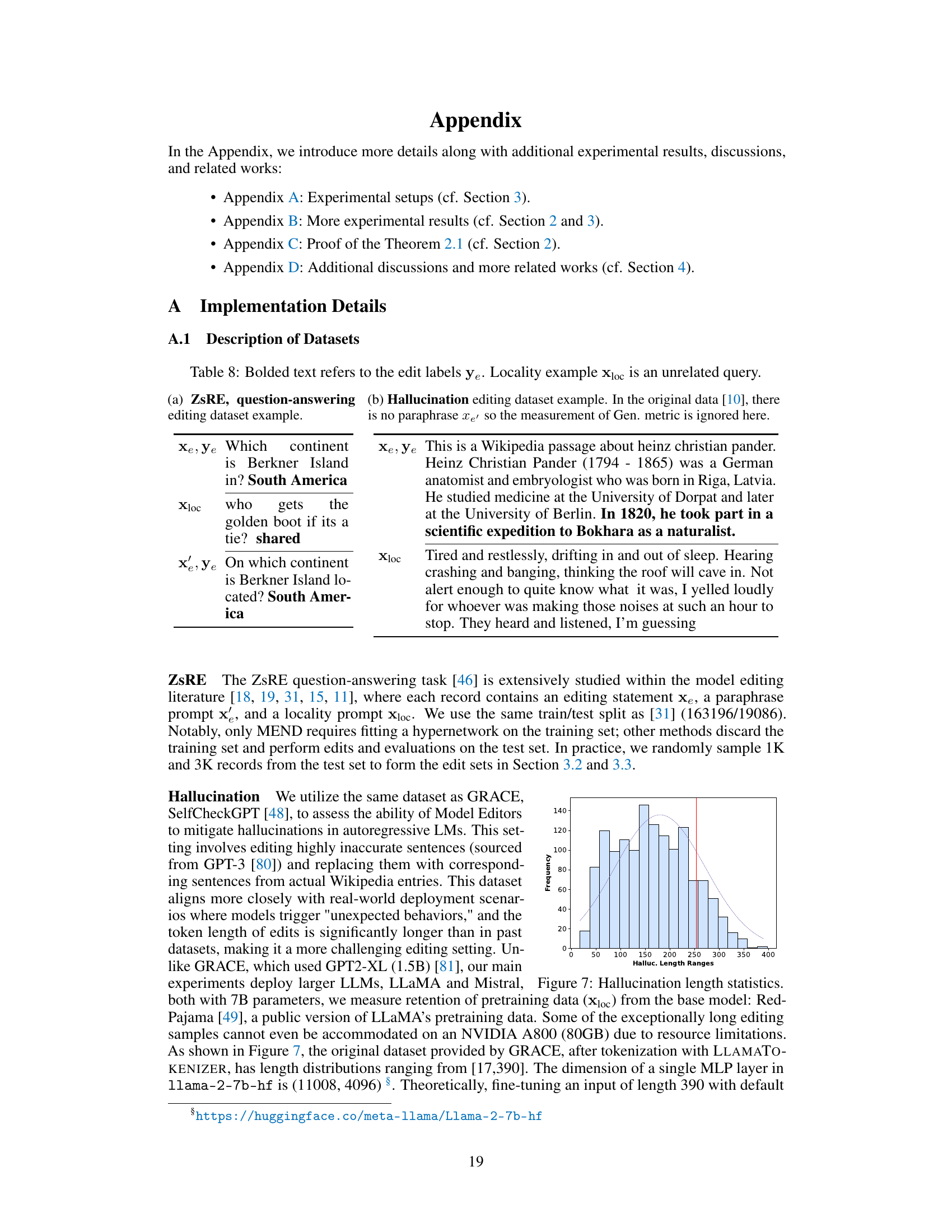

🔼 This table compares different existing model editing methods based on their use of long-term vs. working memory, whether they use parametric or retrieval-based knowledge, if they support lifelong editing, and their performance on reliability, generalization, and locality metrics in continual editing scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of current model editing methods. “√” refers to “yes” and “well-supported”, X refers to “no” or “badly-supported”, and “○” refers to “less-supported”. The three metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality denote the performances on lifelong (continual) editing.

In-depth insights#

Lifelong LLM Edit#

Lifelong LLM editing presents a significant challenge: how to continuously update large language models (LLMs) with new knowledge and correct errors without catastrophic forgetting or excessive computational costs. This “lifelong learning” for LLMs requires careful consideration of where knowledge updates are stored (memory). Directly editing model parameters (long-term memory) risks conflicts with existing knowledge, leading to unreliability and poor generalization. Retrieval-based methods (working memory) offer locality but often struggle with generalization. A promising approach, as suggested by research, is to utilize a dual memory system: maintaining a primary memory for pretrained knowledge and a secondary memory for edits, allowing the model to learn from both simultaneously. A knowledge-sharding mechanism could further address the conflict problem, preventing interference between sequential updates. Effectively managing these memories, potentially through routing mechanisms that determine which memory to access for a given query, is crucial for reliable and generalizable lifelong LLM editing. This would allow LLMs to adapt more effectively to an ever-changing world and improve their overall performance and accuracy.

Dual Memory Scheme#

A dual memory scheme in a large language model (LLM) architecture offers a compelling approach to lifelong learning. By separating long-term memory (the pre-trained model parameters) from short-term memory (a separate module for storing newly acquired knowledge), it elegantly addresses the inherent trade-offs between reliability, generalization, and locality. The system’s ability to selectively route queries to the appropriate memory source prevents interference between previously learned information and new updates, enhancing reliability. This modular design also promotes better generalization, as new knowledge is not forced into an already crowded parameter space, thus mitigating catastrophic forgetting. Furthermore, the focus on editing the short-term memory ensures locality by limiting the scope of parameter changes and preventing unintentional modifications to the pre-trained model. The router component deciding which memory to consult is crucial for the effectiveness of this dual memory system. Overall, such a design shows promise in enabling LLMs to continuously adapt and learn from new information without compromising previously acquired knowledge, creating a more robust and versatile system. The implementation’s success hinges on effective short-term memory management and a well-trained router.

Knowledge Sharding#

Knowledge sharding, as a technique for continual learning in large language models, addresses the challenge of knowledge overwriting during sequential editing. By dividing new knowledge into distinct, smaller units (shards), and assigning these shards to separate memory subspaces, the method aims to prevent conflicts between existing and newly-acquired information. This approach leverages the idea that the parameters can store information in an implicit manner, and through this, the new knowledge is integrated within the model’s parameter space, leading to better generalization and preventing catastrophic forgetting. However, effective sharding strategies need to consider the design of memory merging mechanisms, to combine individual shards without loss of information, especially during continual learning processes. The tradeoff between knowledge density and generalization is crucial. Higher density can lead to more interference. The method’s success depends on both the effectiveness of the sharding and merging strategies.

Impossible Triangle#

The concept of the “Impossible Triangle” in the context of lifelong model editing highlights a fundamental tradeoff between three desirable properties of large language models (LLMs): reliability, generalization, and locality. Directly editing model parameters (long-term memory) improves generalization but compromises reliability and locality due to interference with pre-trained knowledge and previous edits. Conversely, using retrieval-based methods (working memory) prioritizes locality and reliability, but sacrifices generalization, as the model struggles to understand and extrapolate from the added knowledge. This inherent conflict signifies that simultaneously achieving high levels of all three attributes within a single LLM editing strategy presents a significant challenge. The “Impossible Triangle” thus underscores the need for innovative memory mechanisms that can effectively balance these competing requirements for successful lifelong LLM editing.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of WISE is crucial, especially for handling extremely long sequences of edits. This could involve optimizing the memory routing and merging mechanisms. Investigating alternative memory architectures, such as those inspired by biological memory systems, may yield more robust and efficient lifelong model editing techniques. Extending WISE to a broader range of LLMs and tasks is also important; current experiments focus on a few specific LLMs and tasks. Finally, a key area of focus should be mitigating potential risks, including the misuse of model editing for harmful purposes. This requires further research into safeguards and ethical guidelines for lifelong model editing.

More visual insights#

More on figures

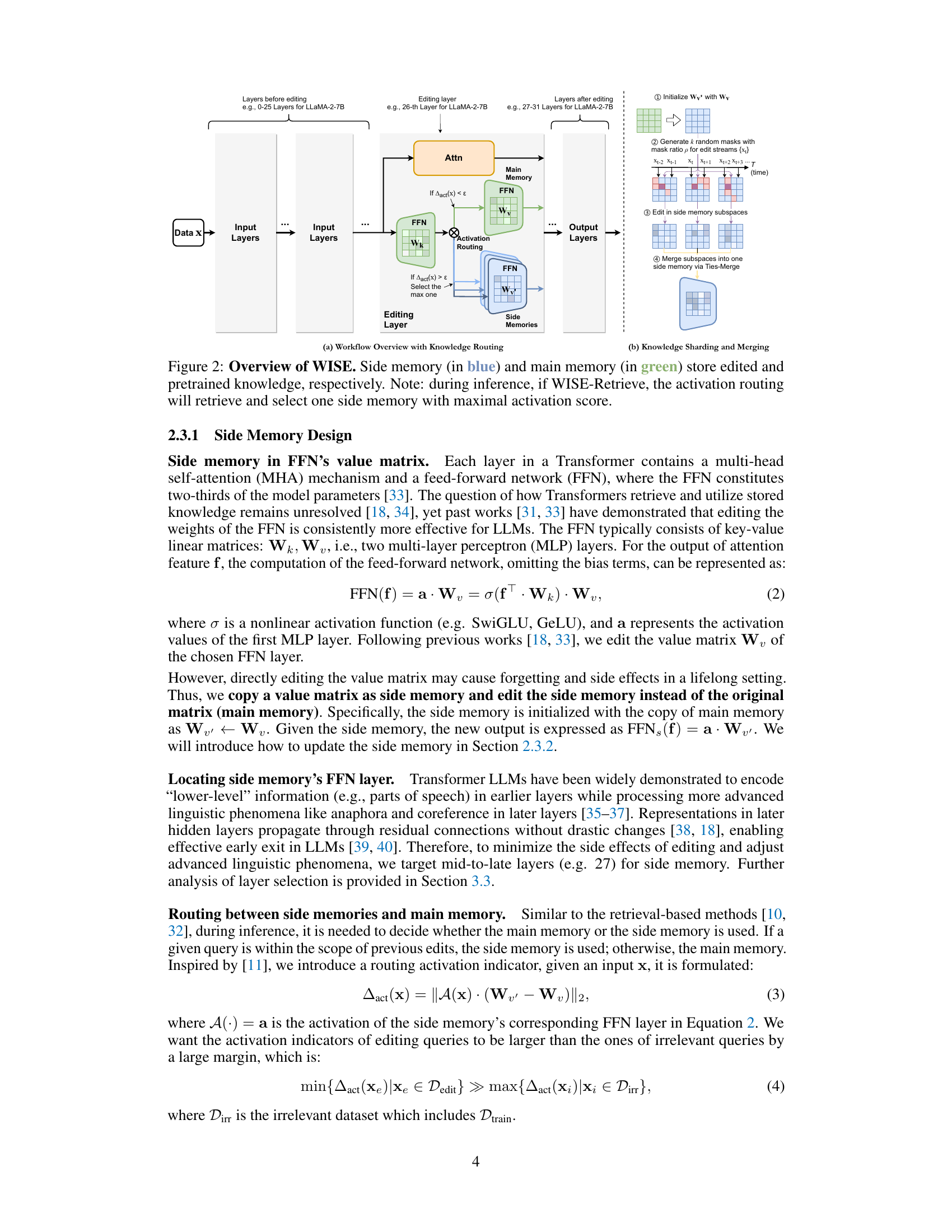

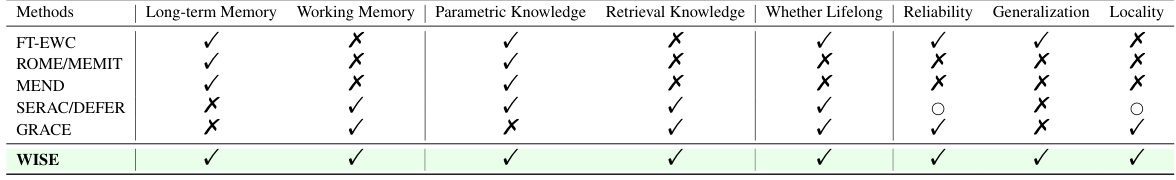

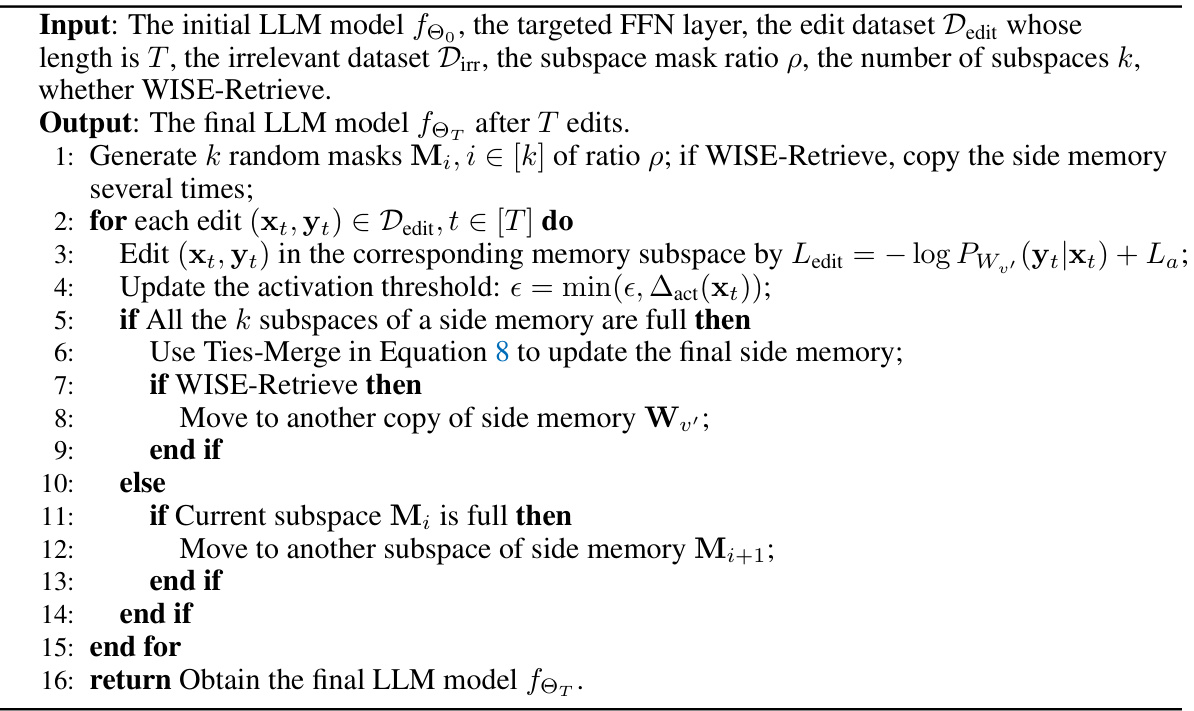

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the WISE model, which uses a dual parametric memory scheme. The main memory stores pretrained knowledge, while the side memory stores newly edited knowledge. A routing mechanism decides which memory to use for a given query. For continual editing, knowledge sharding and merging are used to avoid conflicts between edits. The left panel shows the overall workflow with the knowledge routing mechanism, while the right panel shows the details of knowledge sharding and merging.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of WISE. Side memory (in blue) and main memory (in green) store edited and pretrained knowledge, respectively. Note: during inference, if WISE-Retrieve, the activation routing will retrieve and select one side memory with maximal activation score.

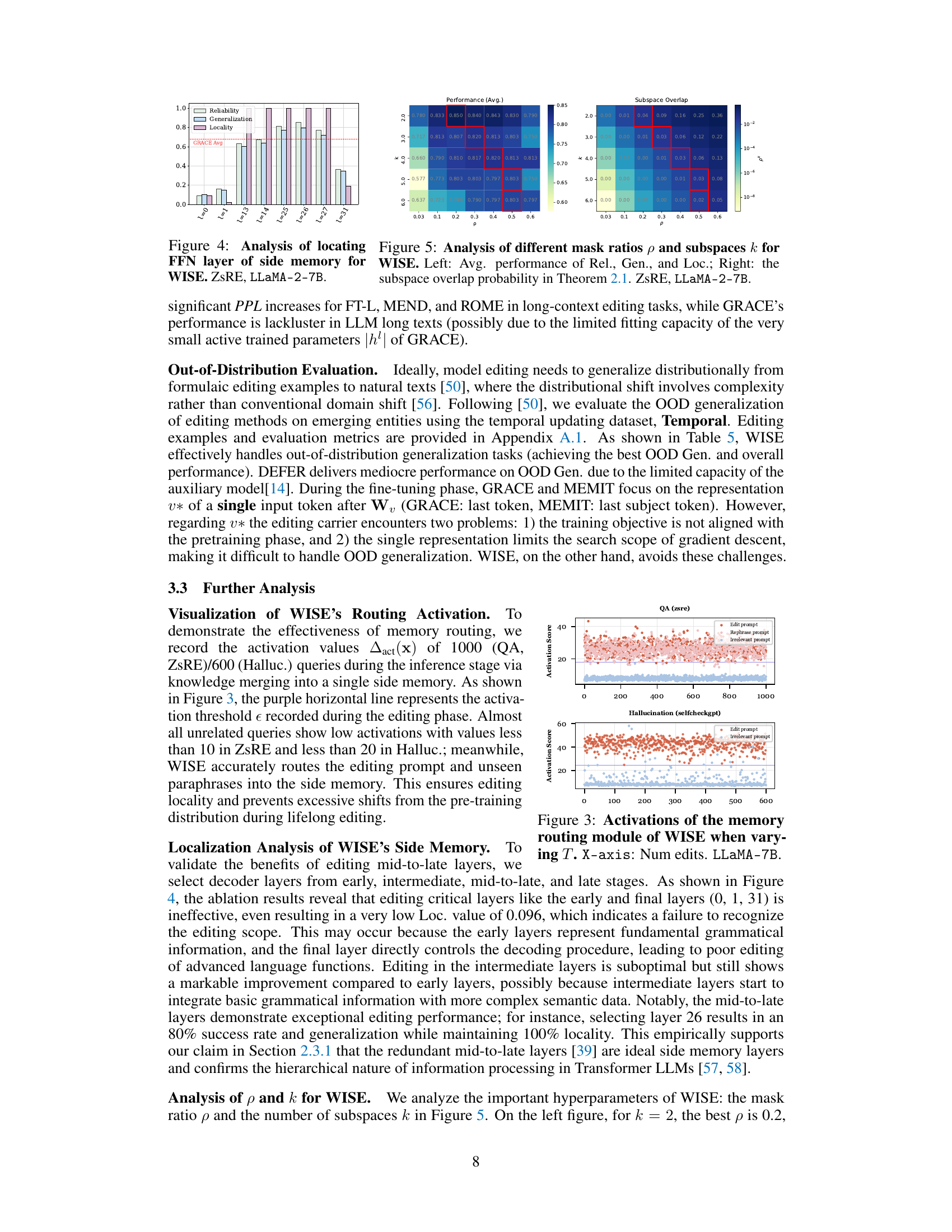

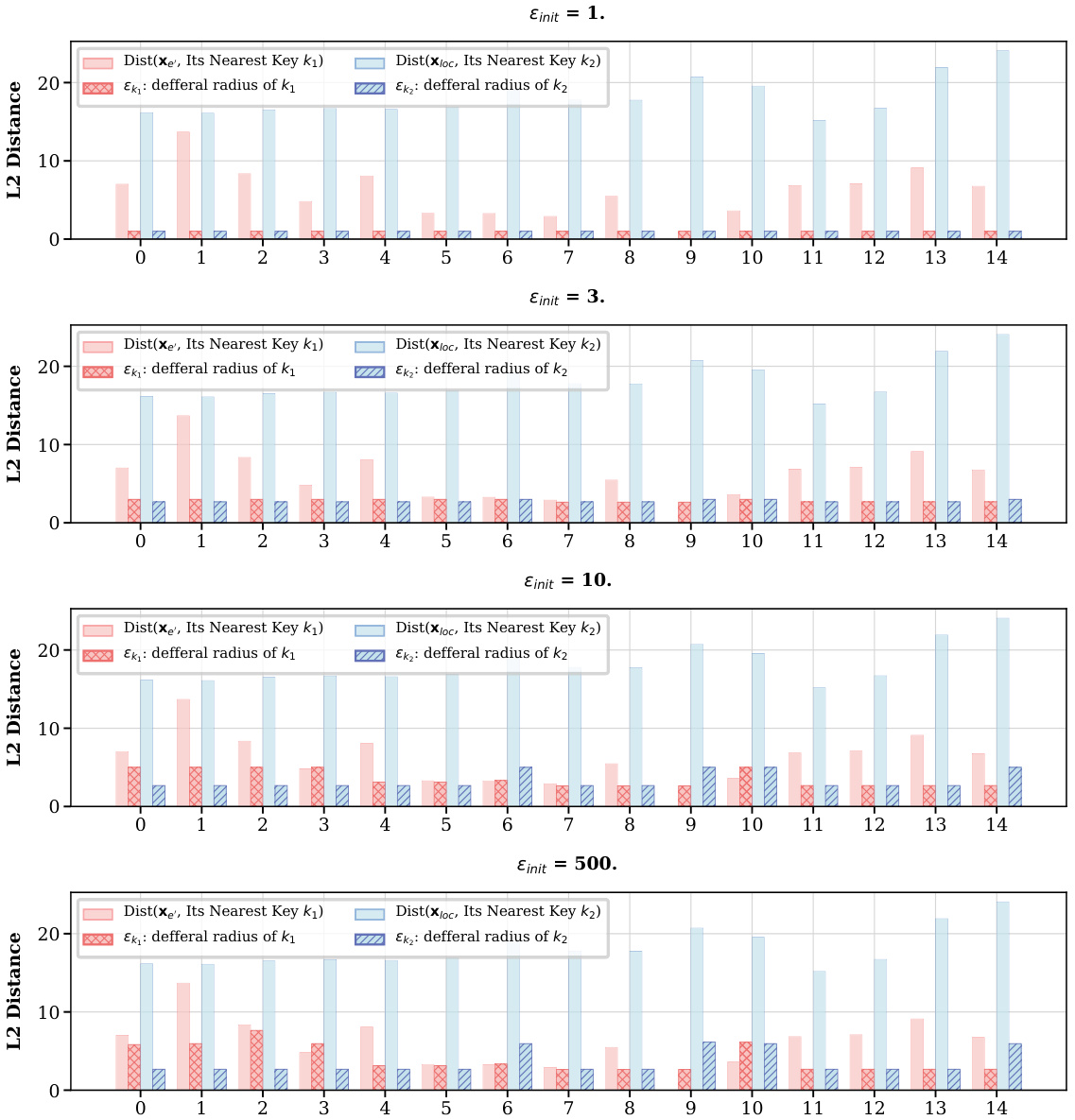

🔼 This figure analyzes the impact of two hyperparameters in WISE: the mask ratio (p) and the number of subspaces (k). The left panel shows the average performance across reliability, generalization, and locality metrics for various combinations of p and k. The right panel displays the probability of overlap between the subspaces, as calculated by Theorem 2.1 in the paper. The red boxes highlight the optimal parameter settings that balance performance and overlap. The results suggest an optimal trade-off where sufficient overlap exists to help merge knowledge but not so much that it causes conflicts.

read the caption

Figure 5: Analysis of different mask ratios p and subspaces k for WISE. Left: Avg. performance of Rel., Gen., and Loc.; Right: the subspace overlap probability in Theorem 2.1. ZsRE, LLAMA-2-7B.

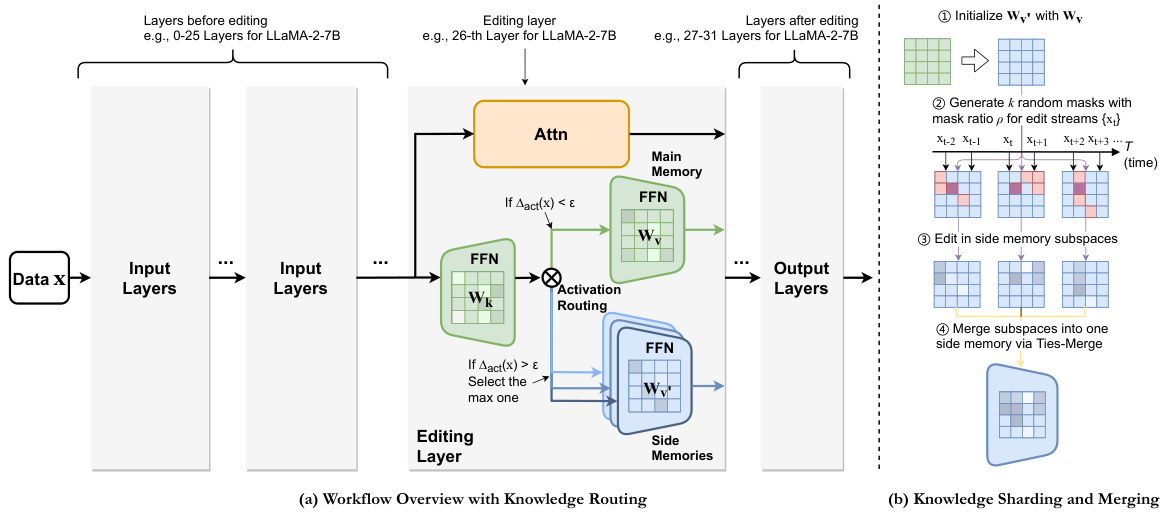

🔼 This figure displays the results of an ablation study conducted to determine the optimal layer within the feed-forward network (FFN) of a large language model (LLM) to be used for storing edited knowledge. The study was performed using the ZSRE dataset and the LLAMA-2-7B architecture. The x-axis represents different layers of the FFN, while the y-axis shows the average performance across the metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality. The figure reveals that selecting layers in the middle-to-late range yields the best performance, highlighting the importance of choosing appropriate layers for effective side memory design. The red line indicates the average performance of GRACE (a baseline method) across these metrics.

read the caption

Figure 4: Analysis of locating FFN layer of side memory for WISE. ZSRE, LLAMA-2-7B.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the WISE model, which uses a dual memory system for lifelong model editing. The main memory stores the pretrained knowledge, while the side memory stores the edited knowledge. A routing mechanism is used to decide which memory to use for a given query. The figure also shows the knowledge sharding and merging mechanisms used for continual editing.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of WISE. Side memory (in blue) and main memory (in green) store edited and pretrained knowledge, respectively. Note: during inference, if WISE-Retrieve, the activation routing will retrieve and select one side memory with maximal activation score.

🔼 This figure shows the inference time of a single instance for LLAMA after t ∈ [0,3000] editing steps, measured across 10 trials of each setting. WISE-Merge incurs a constant inference delay (about 3%) as the editing stream expands. WISE-Retrieve, due to the introduction of retrieval routing, shows an increase in inference time as the number of edits increases, with a time cost increment of about 7% after 3K edits.

read the caption

Figure 6: Inference time of WISE when varying T. ZsRE, LLAMA-2-7B.

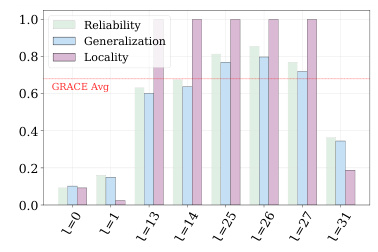

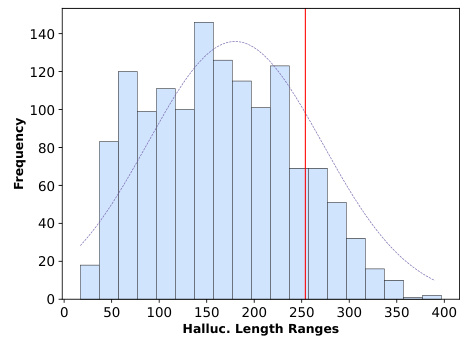

🔼 This histogram displays the distribution of the lengths of hallucination examples in the SelfCheckGPT dataset, after tokenization using the LlamaTokenizer. The x-axis represents the length of the hallucination examples (in tokens), and the y-axis represents the frequency of hallucinations with that length. The red line indicates the threshold (250) used in the paper to filter out excessively long examples which exceeded memory limitations.

read the caption

Figure 7: Hallucination length statistics.

🔼 The figure shows the average indirect effect of the MLP across different layers in LLAMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B. The causal effect of states at the early site with Attn or MLP modules severed shows the importance of mid-layer MLPs in mediating the flow of information, affecting the model’s ability to recall factual knowledge and pass information to the final layer.

read the caption

Figure 8: Mid-layer MLPs play a crucial mediating role in LLAMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B.

🔼 This figure shows the results of different lifelong model editing methods on three key metrics: reliability, generalization, and locality. Methods that edit long-term memory (direct model parameters) or working memory (retrieval-based activations) struggle to achieve high scores across all three metrics, illustrating an ‘impossible triangle.’ The proposed WISE method significantly outperforms these prior methods, demonstrating high scores in all three metrics simultaneously.

read the caption

Figure 1: Metric triangle among reliability, generalization, and locality. ZsRE dataset, number of continual edits T = 100, LLaMA-2-7B. Editing methods based on long-term memory (ROME and FT-EWC) and working memory (DEFER and GRACE) show the impossible triangle in metrics, while our WISE is leading in all three metrics.

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the WISE model, which uses a dual parametric memory mechanism. The main memory stores the pretrained knowledge, while the side memory stores the edited knowledge. A router decides which memory to use based on the input query. The figure also illustrates the knowledge sharding and merging mechanism for continual editing. The edits are placed into distinct subspaces within the side memory, which are subsequently merged to create a comprehensive side memory without conflicts.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of WISE. Side memory (in blue) and main memory (in green) store edited and pretrained knowledge, respectively. Note: during inference, if WISE-Retrieve, the activation routing will retrieve and select one side memory with maximal activation score.

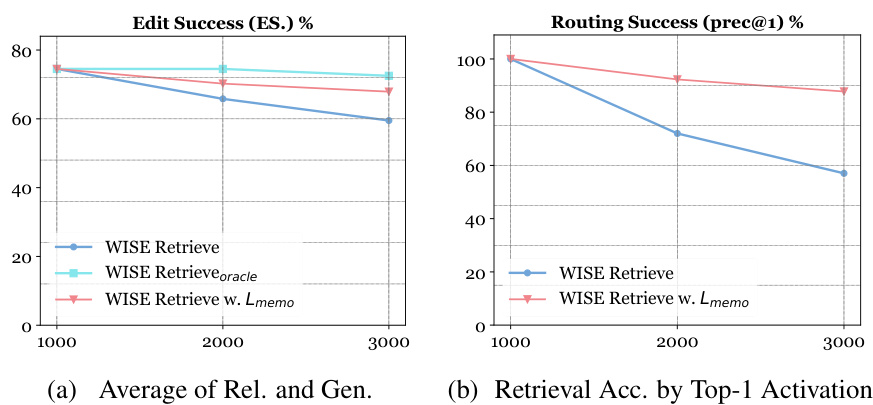

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three variations of WISE (Retrieve, Retrieveoracle, and Retrieve w. Lmemo) across different numbers of edits (T). The left subfigure (a) displays the average of Reliability and Generalization scores (Edit Success, ES), illustrating the overall editing effectiveness. The right subfigure (b) shows the retrieval accuracy (precision@1), indicating the success rate of the Top-1 Activation in correctly routing to the appropriate Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). The experiment used the ZsRE dataset and the LLaMA-2-7B model.

read the caption

Figure 11: Comparing editing results of WISE-{Retrieve, Retrieveoracle, Retrieve w. Lmemo} when varying T. (a) shows the simple average of Rel. and Gen. (ES.), while (b) shows retrieval accuracy, i.e., whether the Top-1 Activation routes to the correct MLP (prec@1). X-axis: Num edits. ZsRE. LLAMA-2-7B.

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of adding random prefix tokens to the editing process on the editing success rate, which is evaluated using the Reliability and Generalization metrics. The results show that while adding random prefix tokens improves the model’s robustness to various contexts, it can also decrease the editing success rate. The figure shows the performance of the model with and without prefix tokens for different numbers of edits (T).

read the caption

Figure 12: Ablation studies on Random Prefix Token (PT) of WISE. Light/Dark colors indicate the Editing Sucess w.o./w. PT addition. ZsRE. LLAMA-2-7B

🔼 This figure shows the inference time of a single instance for LLAMA after t ∈ [0,3000] editing steps, measured across 10 trials of each setting. WISE-Merge incurs a constant inference delay (about 3%) as the editing stream expands. WISE-Retrieve, due to the introduction of retrieval routing, shows an increase in inference time as the number of edits increases, with a time cost increment of about 7% after 3K edits.

read the caption

Figure 6: Inference time of WISE when varying T. ZsRE, LLAMA-2-7B.

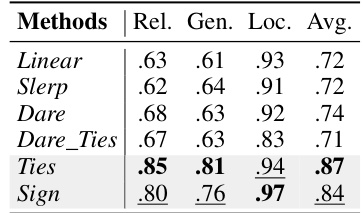

More on tables

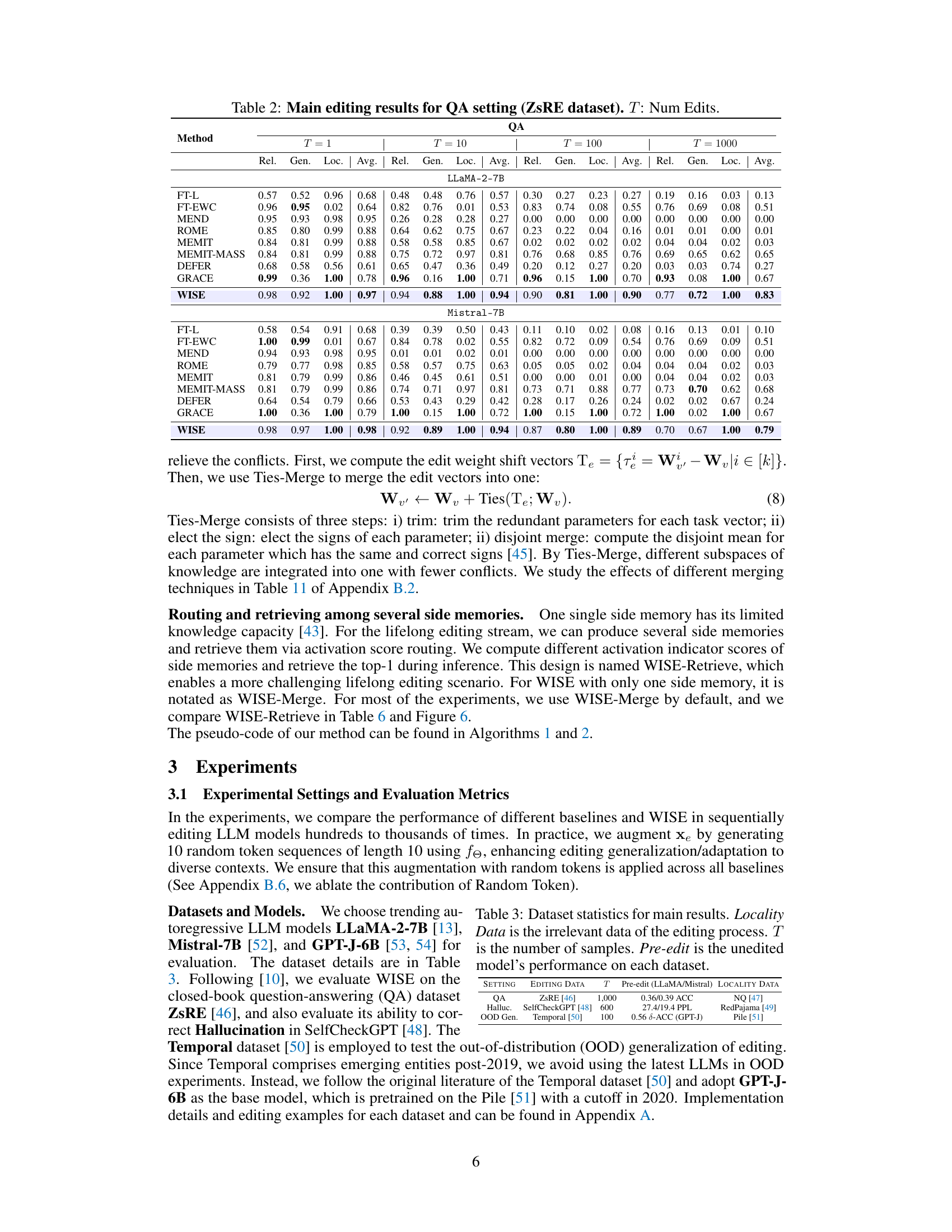

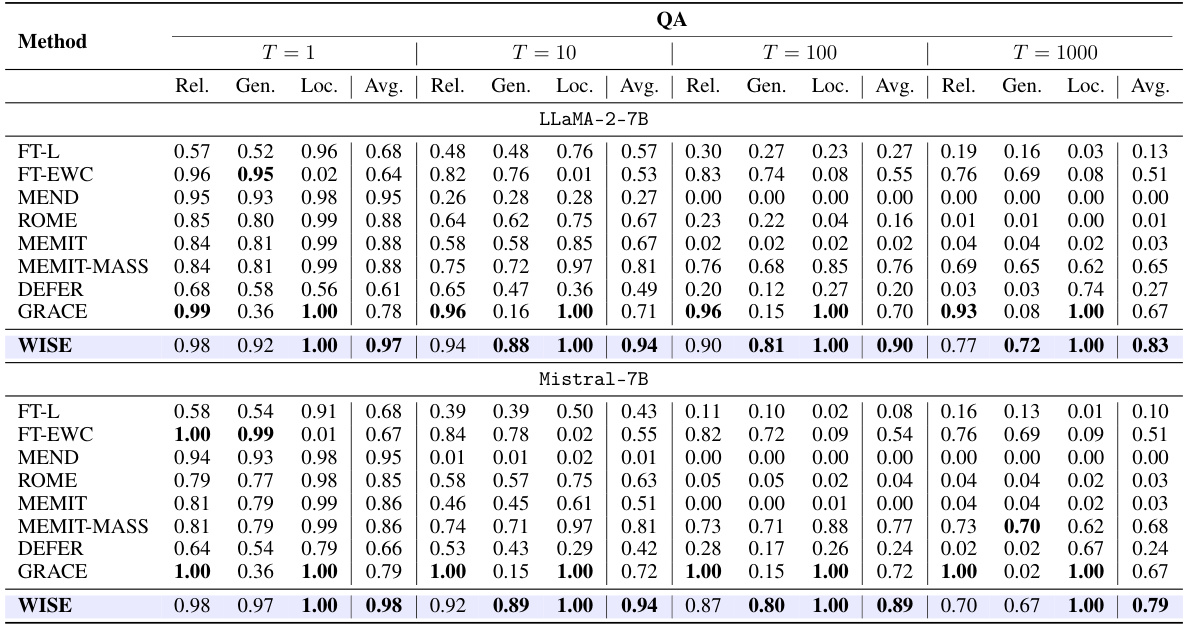

🔼 This table presents the main results of the question answering task using the ZsRE dataset. It compares different methods for lifelong model editing across various metrics. The metrics evaluated are Reliability (Rel.), Generalization (Gen.), and Locality (Loc.), averaged across different numbers of continual edits (T=1, 10, 100, 1000). The results are shown for two different LLM architectures: LLAMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B.

read the caption

Table 2: Main editing results for QA setting (ZsRE dataset). T: Num Edits.

🔼 This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted for the question answering task using the ZsRE dataset. It compares different model editing methods (FT-L, FT-EWC, MEND, ROME, MEMIT, MEMIT-MASS, DEFER, GRACE, and WISE) across four different numbers of continual edits (T=1, T=10, T=100, T=1000). For each method and number of edits, the table shows the reliability, generalization, and locality metrics, as well as the average score across these three metrics. Results are provided for two different Large Language Models: LLaMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B.

read the caption

Table 2: Main editing results for QA setting (ZsRE dataset). T: Num Edits.

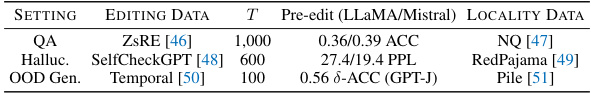

🔼 This table presents the main results of the Hallucination setting using the SelfCheckGPT dataset. It compares various methods for continual learning and model editing, evaluating their performance across different numbers of edits (T). The metrics used are Reliability (PPL for perplexity), Locality (an increase indicates better locality), and shows the average performance across these metrics. The goal is to assess how well each method can correct hallucinations while maintaining the model’s original knowledge and generalization abilities.

read the caption

Table 4: Main editing results for Hallucination setting (SelfCheckGPT dataset). T: Num Edits.

🔼 This table presents the main results of the proposed WISE model and several baseline methods on a question-answering task using the ZsRE dataset. The performance is evaluated across four different numbers of continual edits (T = 1, 10, 100, and 1000) and three key metrics: Reliability (Rel.), Generalization (Gen.), and Locality (Loc.). The average score across the three metrics is also reported for each method.

read the caption

Table 2: Main editing results for QA setting (ZsRE dataset). T: Num Edits.

🔼 This table presents the results of scaling the number of continual edits to 3000 for the ZsRE dataset using the LLaMA-2-7B model. It compares the performance of WISE-Merge (using a single side memory and multi-time merging), WISE-Retrieve (keeping several side memories and retrieval), and a theoretical upper bound for WISE-Retrieve (Oracle). The table shows that WISE consistently outperforms existing baselines, highlighting its scalability for handling extremely long continual edits. The ‘oracle’ version provides insight into the potential of WISE with significantly improved retrieval of side memories.

read the caption

Table 6: Scaling to 3K edits of ZsRE. LLAMA-2-7B.

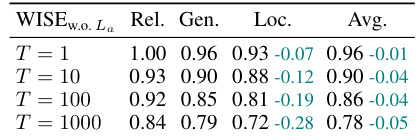

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results of the Router component in the WISE model. It compares the performance of WISE with and without the router, showing the impact of the router on the model’s ability to maintain reliability, generalization, and locality during lifelong model editing. The results demonstrate that removing the router leads to a significant decrease in locality, highlighting the router’s importance in identifying editing scopes and minimizing side effects.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation study of Router (compared with Table 2). LlaMA.

🔼 This table compares several existing lifelong model editing methods across three key metrics: reliability, generalization, and locality. It shows whether each method edits long-term memory (model parameters) or working memory (activations/representations), and how well they perform on each metric in a continual editing scenario (multiple edits over time). The results highlight the trade-offs between these three desired properties for different memory editing approaches.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of current model editing methods. “√” refers to “yes” and “well-supported”, X refers to “no” or “badly-supported”, and “○” refers to “less-supported”. The three metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality denote the performances on lifelong (continual) editing.

🔼 This table presents the main results of the experiment conducted for the question answering task using the ZsRE dataset. It compares the performance of various model editing methods (FT-L, FT-EWC, MEND, ROME, MEMIT, MEMIT-MASS, DEFER, GRACE, and WISE) across different numbers of continual edits (T = 1, 10, 100, 1000). The performance is evaluated using three metrics: Reliability (Rel.), Generalization (Gen.), and Locality (Loc.). The results are shown separately for two different LLM models: LLaMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B.

read the caption

Table 2: Main editing results for QA setting (ZsRE dataset). T: Num Edits.

🔼 This table compares several existing lifelong model editing methods across three key metrics: Reliability, Generalization, and Locality. It highlights whether each method utilizes long-term or working memory and assesses their performance in maintaining previously learned knowledge while adapting to new information over many sequential edits.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of current model editing methods. “√” refers to “yes” and “well-supported”, X refers to “no” or “badly-supported”, and “○” refers to “less-supported”. The three metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality denote the performances on lifelong (continual) editing.

🔼 This table compares several existing lifelong model editing methods across three key criteria: reliability, generalization, and locality. It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of approaches that focus on long-term memory (directly editing model parameters) versus those that rely on working memory (retrieving and modifying activations). The table uses a visual shorthand (√, X, ○) to quickly communicate the level of support each method provides for each property in continual editing scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of current model editing methods. “√” refers to “yes” and “well-supported”, X refers to “no” or “badly-supported”, and “○” refers to “less-supported”. The three metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality denote the performances on lifelong (continual) editing.

🔼 This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted on the question answering task using the ZsRE dataset. It compares the performance of various methods in terms of reliability, generalization, and locality across different numbers of continual edits (T = 1, 10, 100, 1000). The results are shown separately for two different large language models: LLaMA-2-7B and Mistral-7B. The metrics indicate how well each model can remember both current and previous edits (reliability), generalize to new queries (generalization), and avoid interference between edits and pre-trained knowledge (locality).

read the caption

Table 2: Main editing results for QA setting (ZsRE dataset). T: Num Edits.

🔼 This table compares several existing lifelong model editing methods across three key metrics: reliability (ability to remember past edits), generalization (ability to handle unseen queries), and locality (avoiding unintended edits to unrelated knowledge). It highlights the trade-offs between different approaches that use either long-term memory (directly editing model parameters) or working memory (using retrieval-based methods).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of current model editing methods. “√” refers to “yes” and “well-supported”, X refers to “no” or “badly-supported”, and “○” refers to “less-supported”. The three metrics of Reliability, Generalization, and Locality denote the performances on lifelong (continual) editing.

Full paper#