↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current reinforcement learning algorithms struggle to create cooperation among AI agents in scenarios like social dilemmas, often converging to selfish outcomes. This is because these algorithms typically focus on an individual agent’s gains, neglecting the effects of their actions on others. Existing solutions for promoting cooperation often involve modifying the environment or have limitations like high sample complexity or requiring access to other agents’ internal workings.

This paper introduces “Reciprocators”, a novel approach that fosters cooperation by directly addressing these limitations. Reciprocators are AI agents designed to respond to how other agents influence their rewards. By increasing rewards after positive influences and decreasing them after negative ones, Reciprocators subtly guide other agents towards mutually beneficial behaviors. The experiments demonstrate that this method works effectively even with purely self-interested agents, achieving improved cooperation results compared to existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to encourage cooperation among self-interested AI agents, a critical challenge in multi-agent reinforcement learning. The proposed method, Reciprocators, addresses limitations of existing techniques by influencing opponents’ behavior without requiring privileged access to their learning algorithms. This opens new avenues for designing more cooperative and robust AI systems, and is relevant to various fields where multi-agent interactions are crucial. The study’s findings demonstrate that reciprocation strategies can promote cooperation in complex, temporally extended scenarios. This research provides valuable insights and a promising direction for researchers working on more cooperative, effective, and ethical AI systems.

Visual Insights#

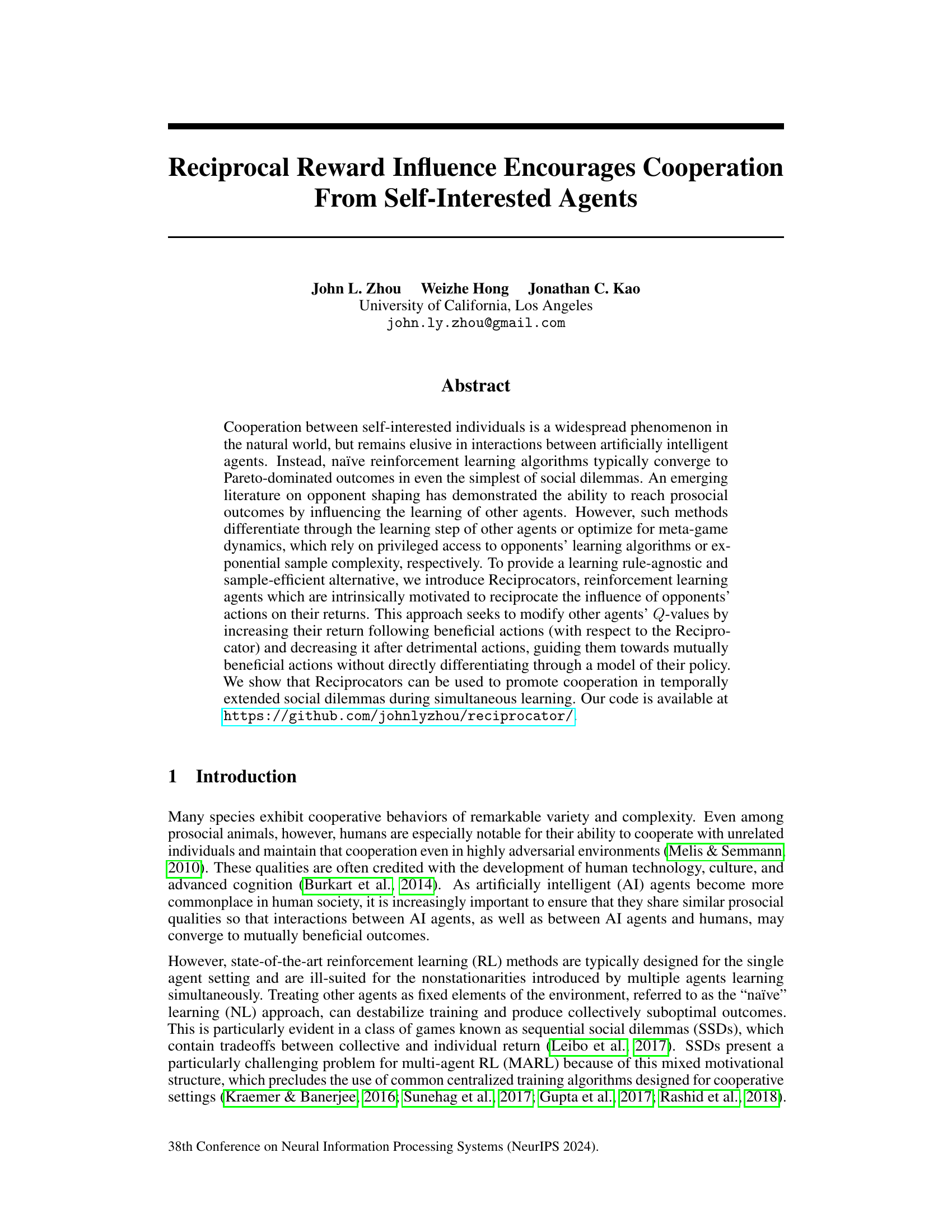

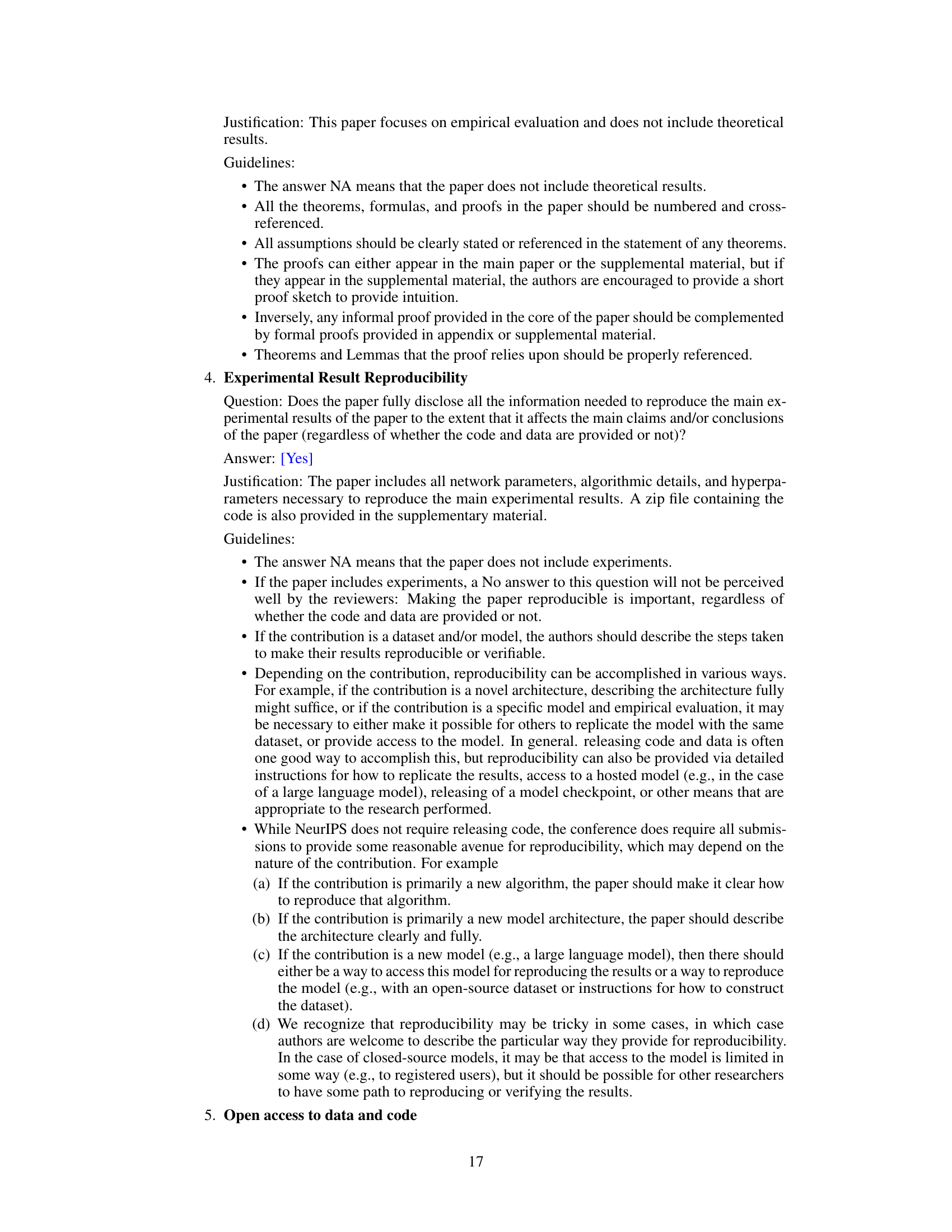

This figure illustrates the reward structures for two sequential social dilemmas used in the paper’s experiments. (a) shows the reward matrix for the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma (IPD), a classic game theory scenario. (b) depicts the reward structure for the Coins game, where agents compete to collect coins, receiving a reward for their own coins and a penalty for collecting their opponent’s coins.

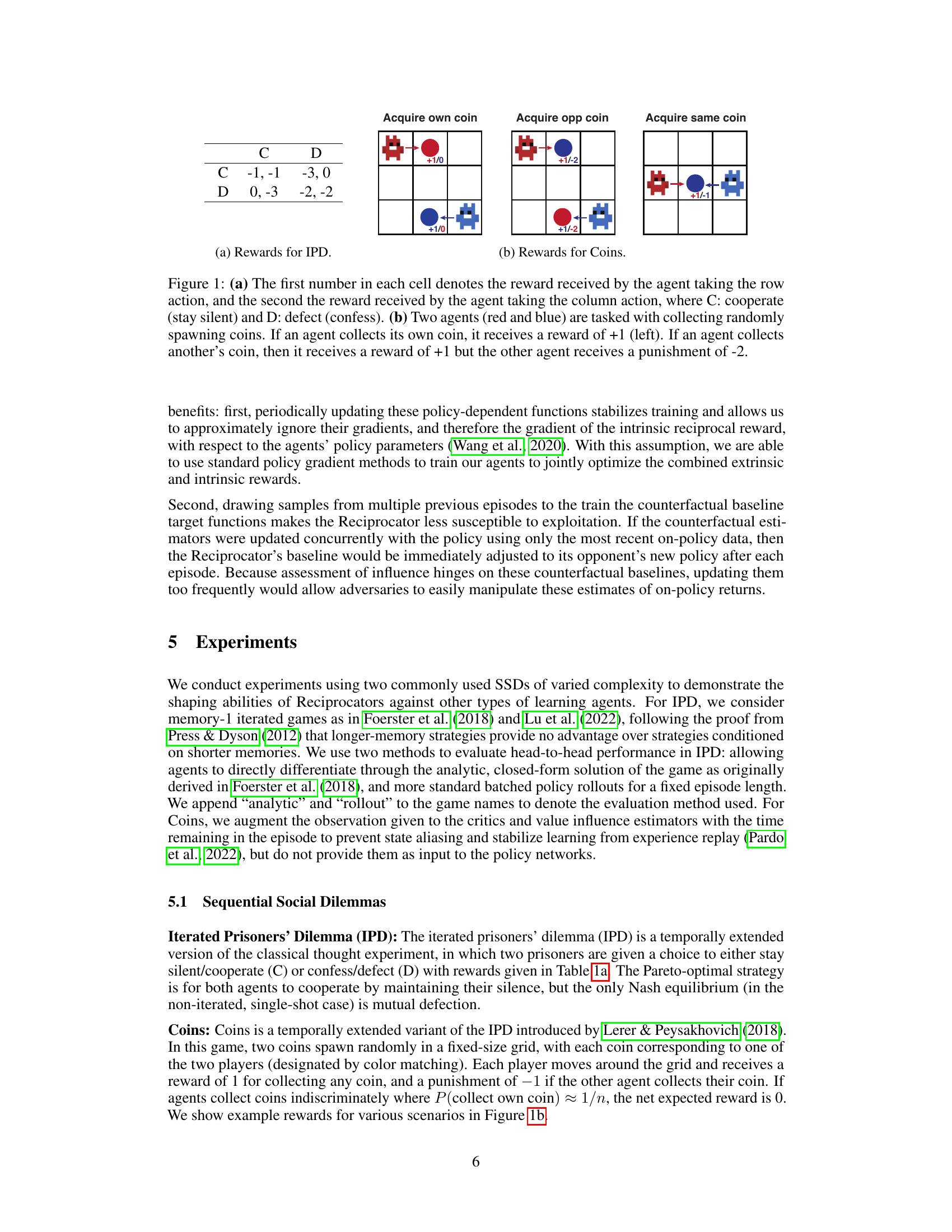

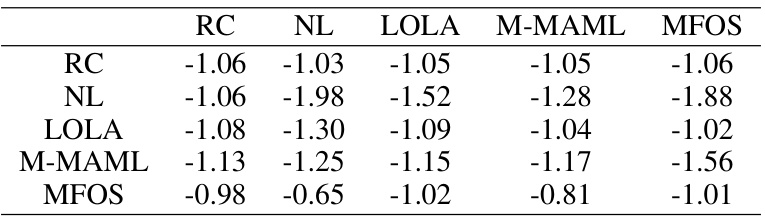

This table presents the average reward per episode achieved by each agent (rows) against every other agent (columns) in the IPD-Analytic setting. The results are from a round-robin tournament where each agent plays against every other agent. Lower values indicate worse performance. The results show that Reciprocators achieve a comparable performance against all other baselines.

In-depth insights#

Reciprocal Reward Shaping#

Reciprocal reward shaping presents a novel approach to fostering cooperation in multi-agent reinforcement learning. Instead of directly incentivizing cooperation, it focuses on shaping the learning process of other agents. By rewarding an agent for actions that reciprocate the influence of other agents’ actions on its rewards, Reciprocal Reward Shaping cleverly manipulates Q-values indirectly, promoting mutually beneficial outcomes. This method is noteworthy for its rule-agnostic nature, requiring minimal assumptions about other agents’ learning algorithms, thus providing a more general solution than prior, more restrictive techniques. Its sample efficiency is also significant, avoiding exponential sample complexity. The inherent tit-for-tat mechanism built into the reciprocal reward encourages cooperative behavior by promoting responses that match the observed influence. However, the success of this approach relies heavily on the stability of the reward function, and further research might explore ways to enhance robustness and adapt to various environmental dynamics. While promising results are demonstrated, additional investigation is needed to assess its scalability and generalizability across a broader range of multi-agent scenarios.

Influence Balance Dynamics#

Influence balance dynamics, a core concept in the paper, tracks the cumulative influence exerted by one agent on another’s returns over time. Positive influence leads to a positive balance, encouraging reciprocal beneficial actions. Conversely, negative influence results in a negative balance, promoting retaliatory or corrective actions. This dynamic interplay between actions and resulting influence shapes the learning process, driving agents towards mutually beneficial strategies. The balance is not simply a static score but a continuously updated measure that adapts to the evolving interaction, making the system responsive to changes in the other agent’s behavior. This approach offers a rule-agnostic mechanism, subtly influencing an agent’s behavior without directly manipulating its learning algorithm. The continuous accumulation of influence allows for a nuanced reciprocation strategy that isn’t confined to immediate exchanges, leading to more robust and cooperative behavior even in complex, extended interactions. The subtle, reward-based mechanism demonstrates a promising method for encouraging cooperation among self-interested agents.

Multi-agent Cooperation#

Multi-agent cooperation, a complex phenomenon in artificial intelligence, is explored in this research. The paper tackles the challenge of achieving cooperative outcomes among self-interested agents, a significant hurdle in the field of multi-agent reinforcement learning. Naïve reinforcement learning approaches often lead to suboptimal, non-cooperative solutions in social dilemmas. The authors introduce a novel solution, Reciprocators, which are agents intrinsically motivated to reciprocate the influence of opponents’ actions. This approach skillfully guides other agents toward mutual benefit by shaping their perceived Q-values, without requiring privileged access to opponent’s learning algorithms or excessive data. The efficacy of this method is showcased through experiments on various sequential social dilemmas, demonstrating superior cooperative outcomes compared to existing approaches, especially in the presence of less cooperative agents. The work highlights the importance of understanding value influence, and it presents a sample-efficient, learning-rule-agnostic approach to address the long-standing issue of promoting cooperation in multi-agent systems. While the paper demonstrates success, future work should explore the approach’s robustness and scalability across a wider array of environments and agent complexities.

Experimental Evaluation#

The experimental evaluation section would likely detail the specific tasks used to test the Reciprocator agents. Methodologies for evaluating cooperative behavior in sequential social dilemmas (SSDs) would be described, likely including metrics such as average reward per episode, proportion of cooperative actions, or Pareto efficiency. The choice of baseline algorithms (e.g., naïve learners, LOLA, M-MAML, MFOS) is critical; a strong justification for their selection would be necessary. The results would demonstrate the Reciprocator’s ability to promote cooperation, possibly showcasing its performance against various baselines in different SSD scenarios. Head-to-head comparisons and statistical significance tests would be essential to support the claims of improved cooperation. The discussion should analyze the results, potentially highlighting any unexpected behavior or limitations of the Reciprocator approach. Importantly, the robustness of the Reciprocator’s performance in varied conditions, such as variations in opponent types, game parameters, and learning rates, should be explored. Overall, a compelling experimental evaluation would rigorously validate the effectiveness of reciprocal reward influence in fostering cooperation among self-interested agents.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on reciprocal reward influence could explore several promising avenues. Extending the temporal scope of reciprocity beyond single episodes is crucial, perhaps through mechanisms that dynamically adjust the balance between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards based on long-term opponent behavior. Investigating the robustness of the approach to different opponent learning algorithms is key, moving beyond naïve learners and evaluating performance against sophisticated, potentially adversarial agents. A significant challenge is to determine optimal hyperparameter settings, specifically the balance between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and the effectiveness of various counterfactual baseline update strategies. Finally, generalizing the approach to more complex, realistic multi-agent environments is essential for demonstrating practical impact. This might involve incorporating richer state representations and action spaces, and carefully considering the computational cost of extending the model. The ultimate goal is to establish a principled framework for promoting cooperation in diverse scenarios without sacrificing sample efficiency.

More visual insights#

More on figures

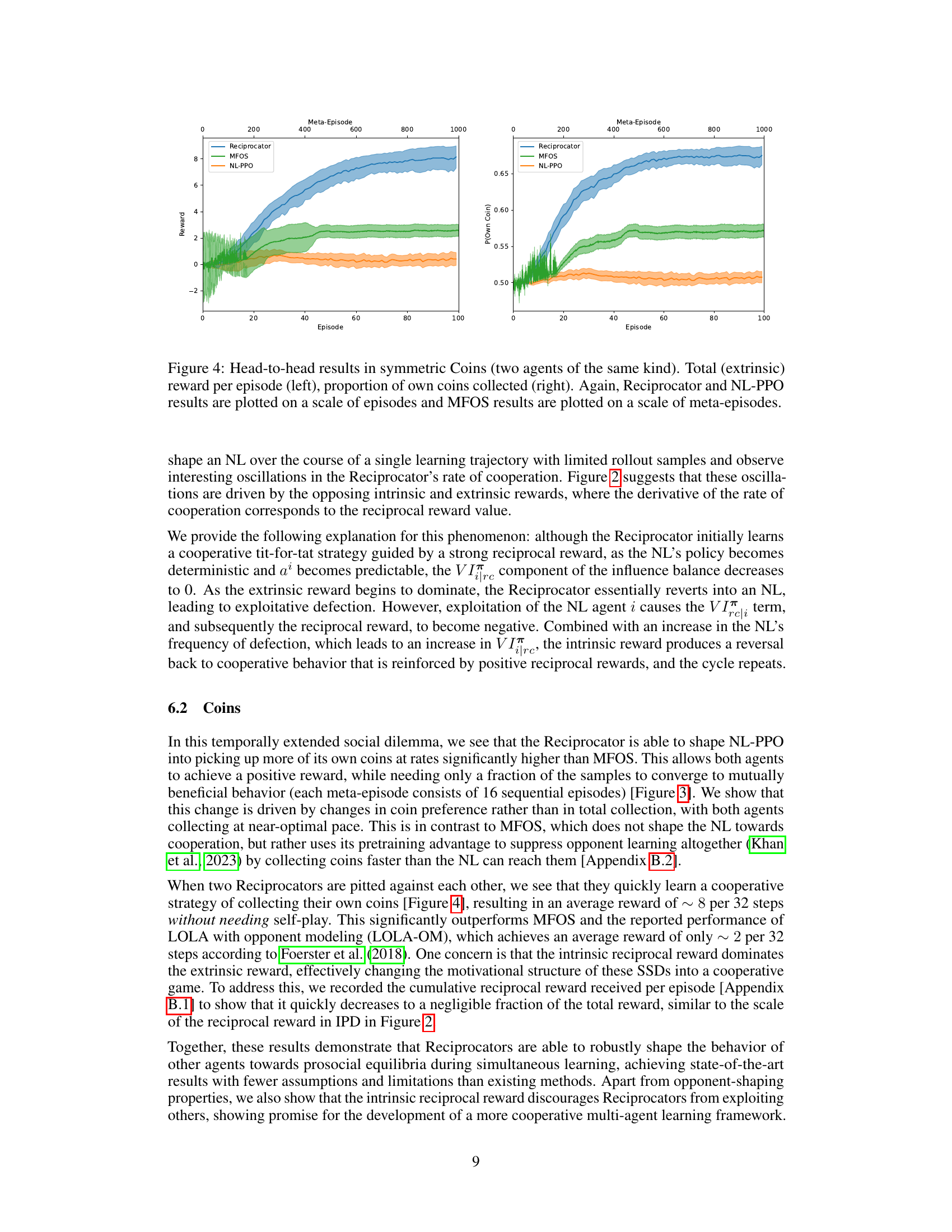

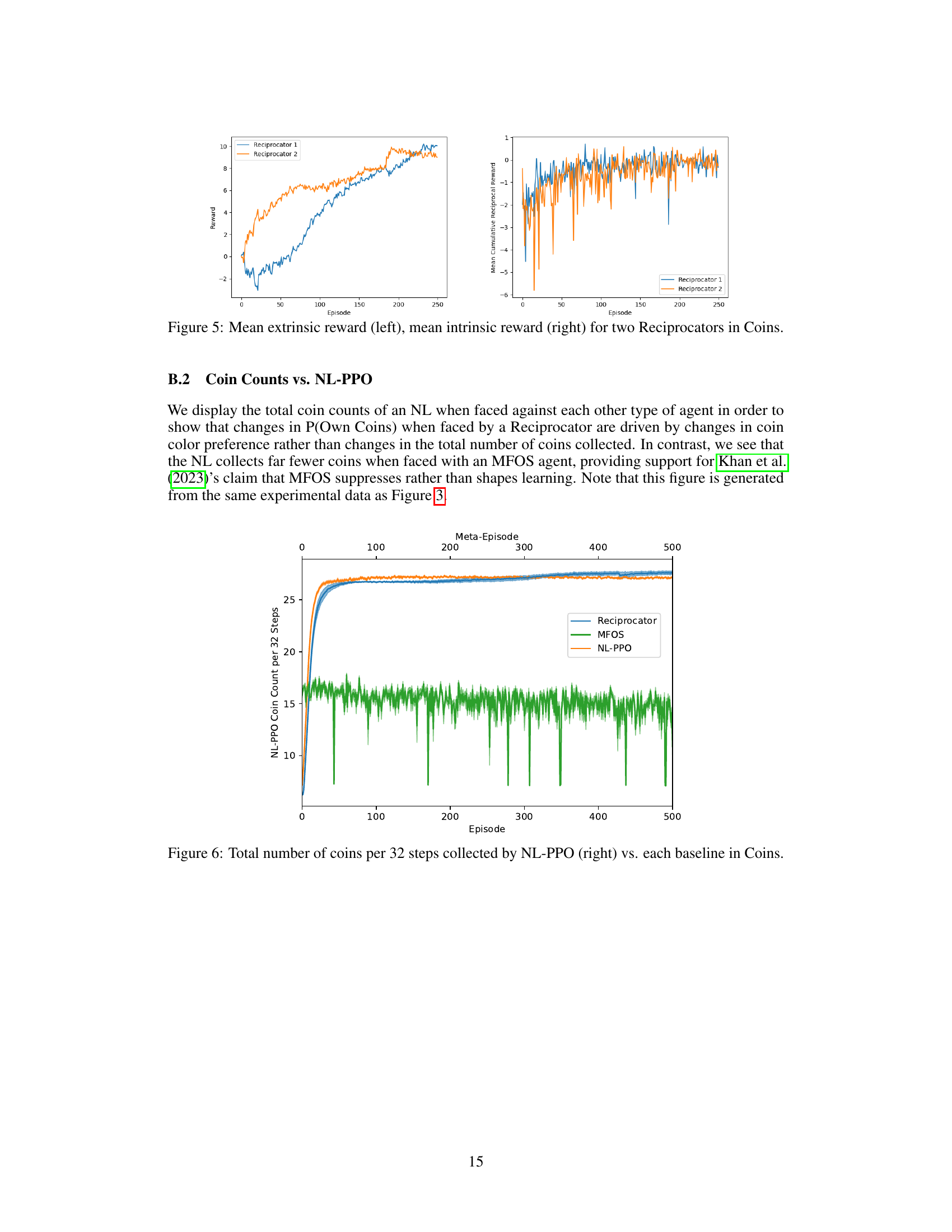

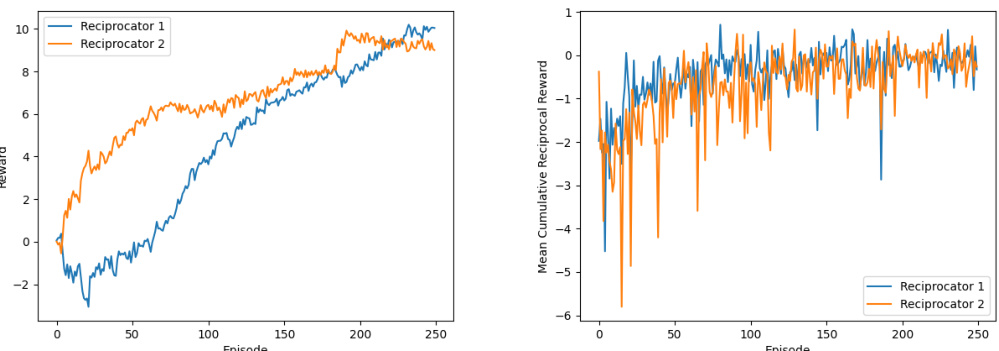

This figure shows the results of a single game between a Reciprocator agent and a Naive Learner (NL) agent in an Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma (IPD) with rollout-based evaluation. The left y-axis displays the average reciprocal reward received by the Reciprocator agent at each step of the game, while the right y-axis shows the probability that the Reciprocator agent chooses to cooperate (C) at each step. The x-axis represents the episode number. The plot demonstrates the oscillatory pattern of the reciprocal reward and cooperation probability, showing how the Reciprocator agent’s behavior changes over the course of the game in response to the NL agent’s actions. The oscillations reflect the interplay between the intrinsic reciprocal reward and the extrinsic reward obtained from the game. The Reciprocator initially cooperates but may defect depending on the NL’s actions, leading to fluctuations in the reciprocal reward and cooperation probability.

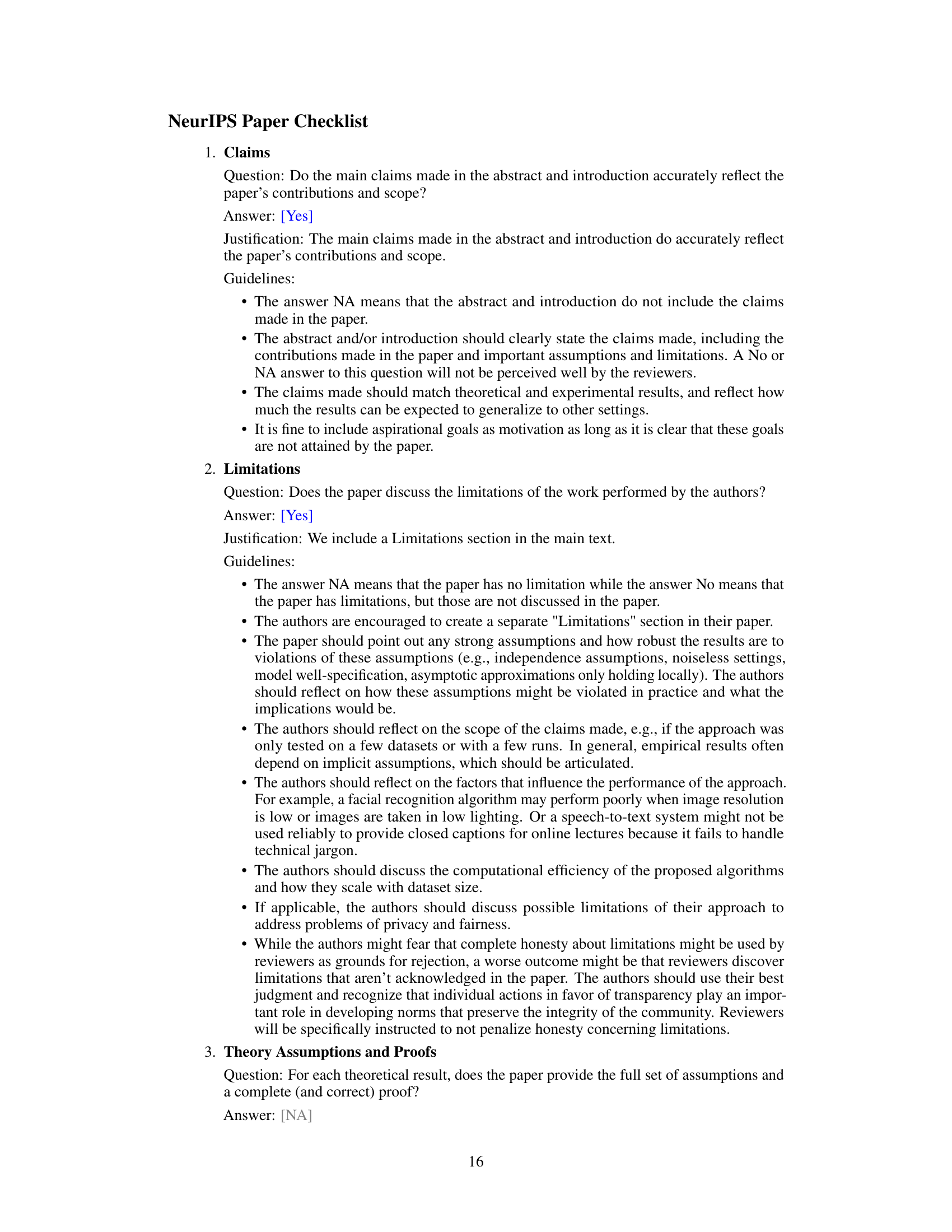

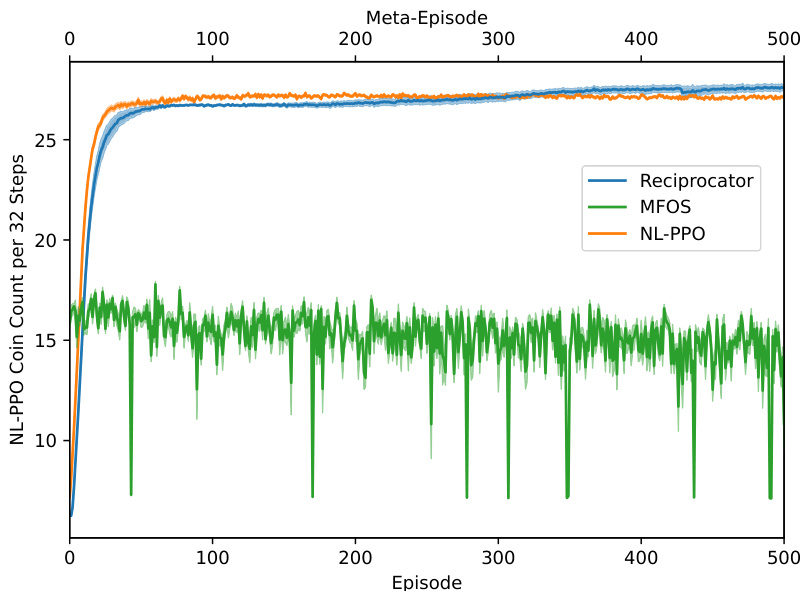

This figure displays the results of training a naive learner (NL) agent in the Coins game against three different opponents: a Reciprocator, MFOS, and another NL-PPO. The left panel shows the proportion of its own coins collected by the NL during training against each opponent. The right panel shows the number of coins collected (own, other, and total) by both the Reciprocator and NL-PPO agents over training episodes. Note that the time scale differs between MFOS and the other two agents, with MFOS using meta-episodes (16 episodes each).

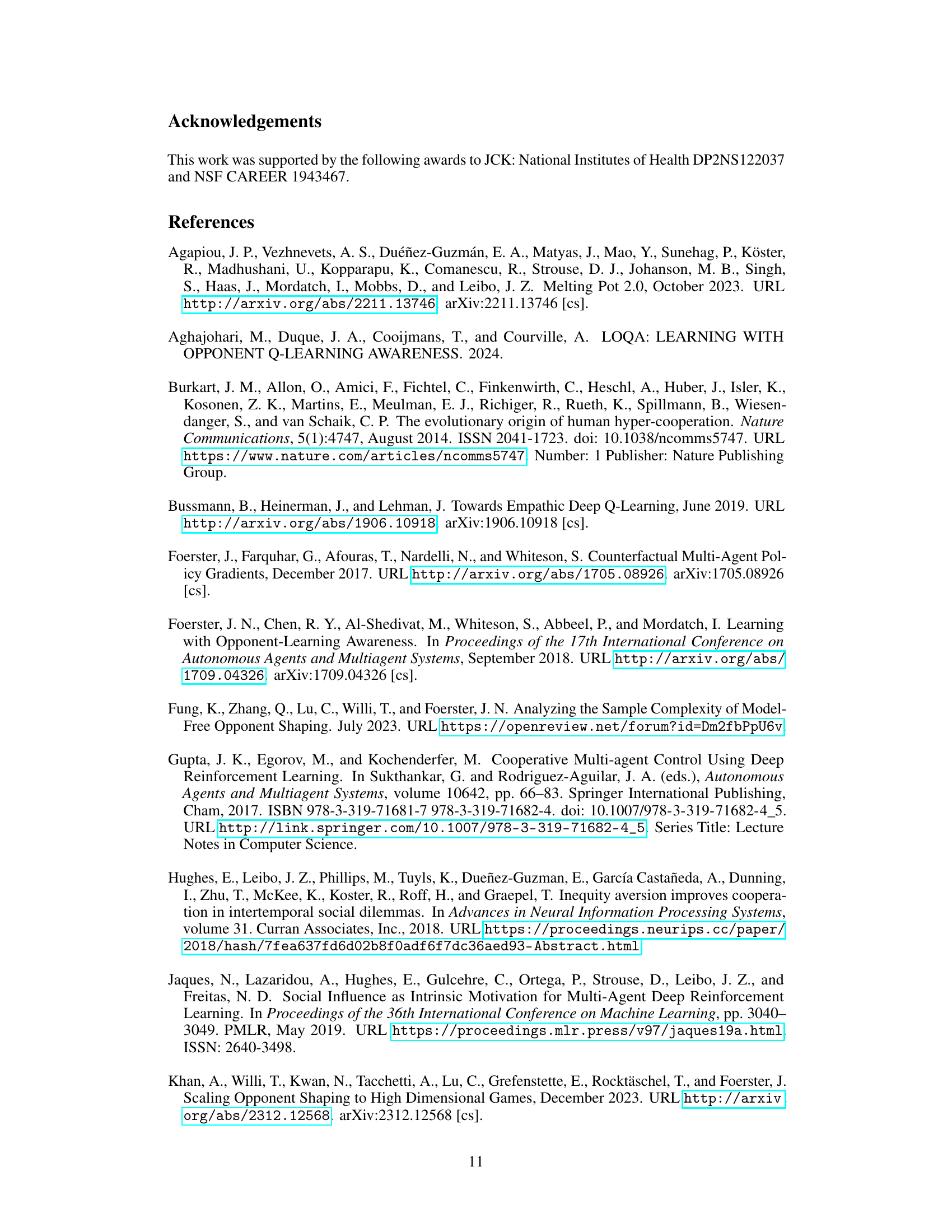

This figure displays the results of a head-to-head competition between two Reciprocator agents in the Coins game, as well as their performance against MFOS and NL-PPO agents. The left panel shows the total extrinsic reward per episode, illustrating the Reciprocator’s ability to achieve higher rewards than the baselines. The right panel shows the proportion of own coins collected by each agent type. This highlights the Reciprocator’s ability to successfully collect more of its own coins than the baselines, demonstrating cooperative behavior.

This figure compares the performance of Reciprocators against MFOS and NL-PPO agents in a symmetric Coins game where both agents are of the same type. The left panel shows the total extrinsic reward per episode, while the right panel shows the proportion of own coins collected by each agent type. It demonstrates that Reciprocators achieve higher rewards and collect a greater proportion of their own coins compared to the other approaches, highlighting their superior cooperative behavior even in a competitive setting. The difference in scaling between the x-axes (episodes vs. meta-episodes) reflects the distinct training methodologies employed by MFOS, which uses meta-learning across multiple episodes.

This figure shows the results of training a naive learner (NL) in the Coins game against three different opponents: a Reciprocator, MFOS, and another NL-PPO. The left panel shows the proportion of own coins collected by the NL over time when facing each opponent. The right panel displays the number of coins collected by type (own coins, other coins, and total coins) for both the Reciprocator and the NL-PPO over time. The x-axis represents the episode number, but note that MFOS results are shown in terms of meta-episodes (16 episodes each). This visualizes how the Reciprocator shapes the NL’s behavior towards collecting more of its own coins, contrasting with the other opponents.

More on tables

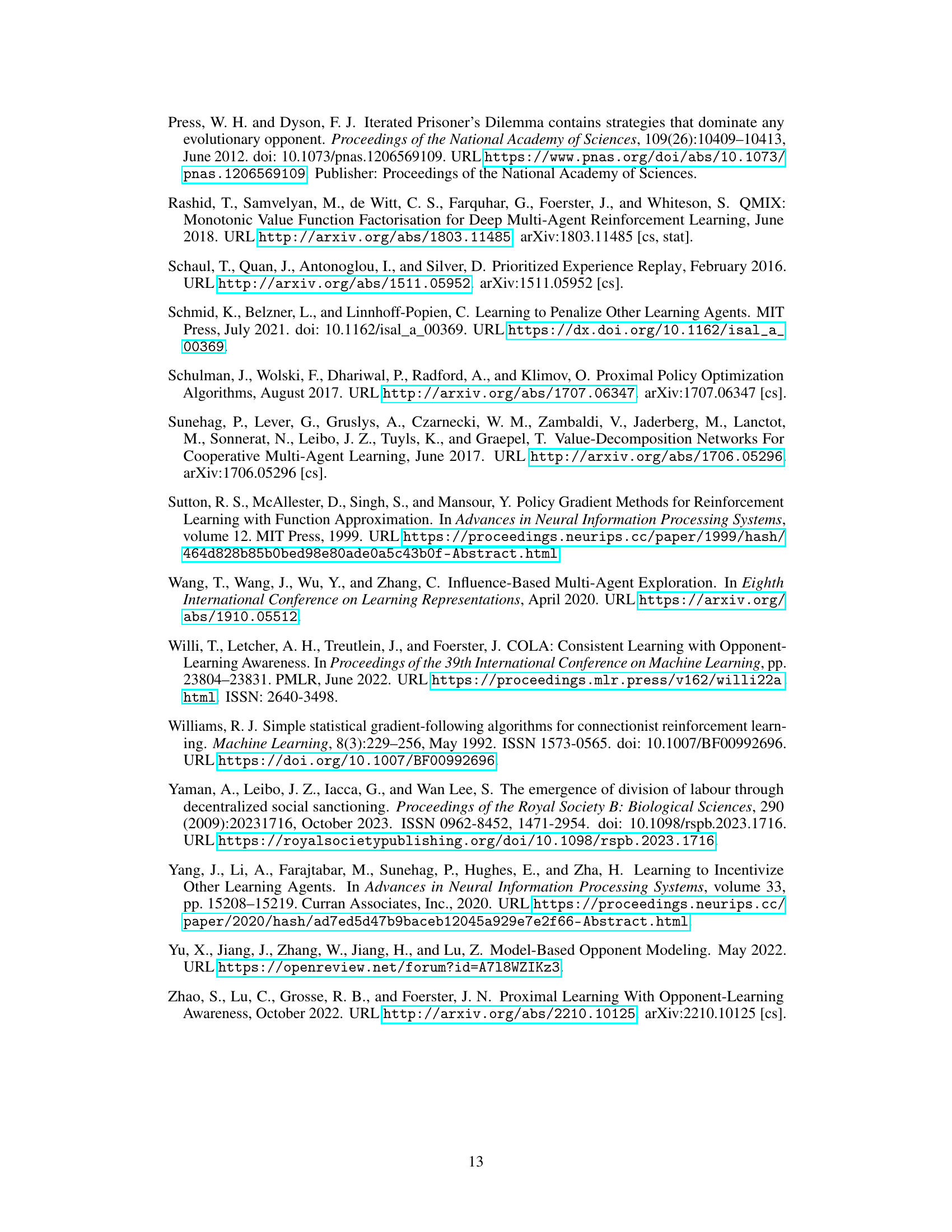

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) agents in the IPD-Rollout and Coins experiments. It details the network architecture (number and size of convolutional and linear layers, and GRUs), training parameters (episode length, Adam learning rate, PPO epochs per episode, PPO-clip epsilon), and reward parameters (discount factor and entropy coefficient). These settings were used for both the Reciprocator and baseline agents in the respective experiments.

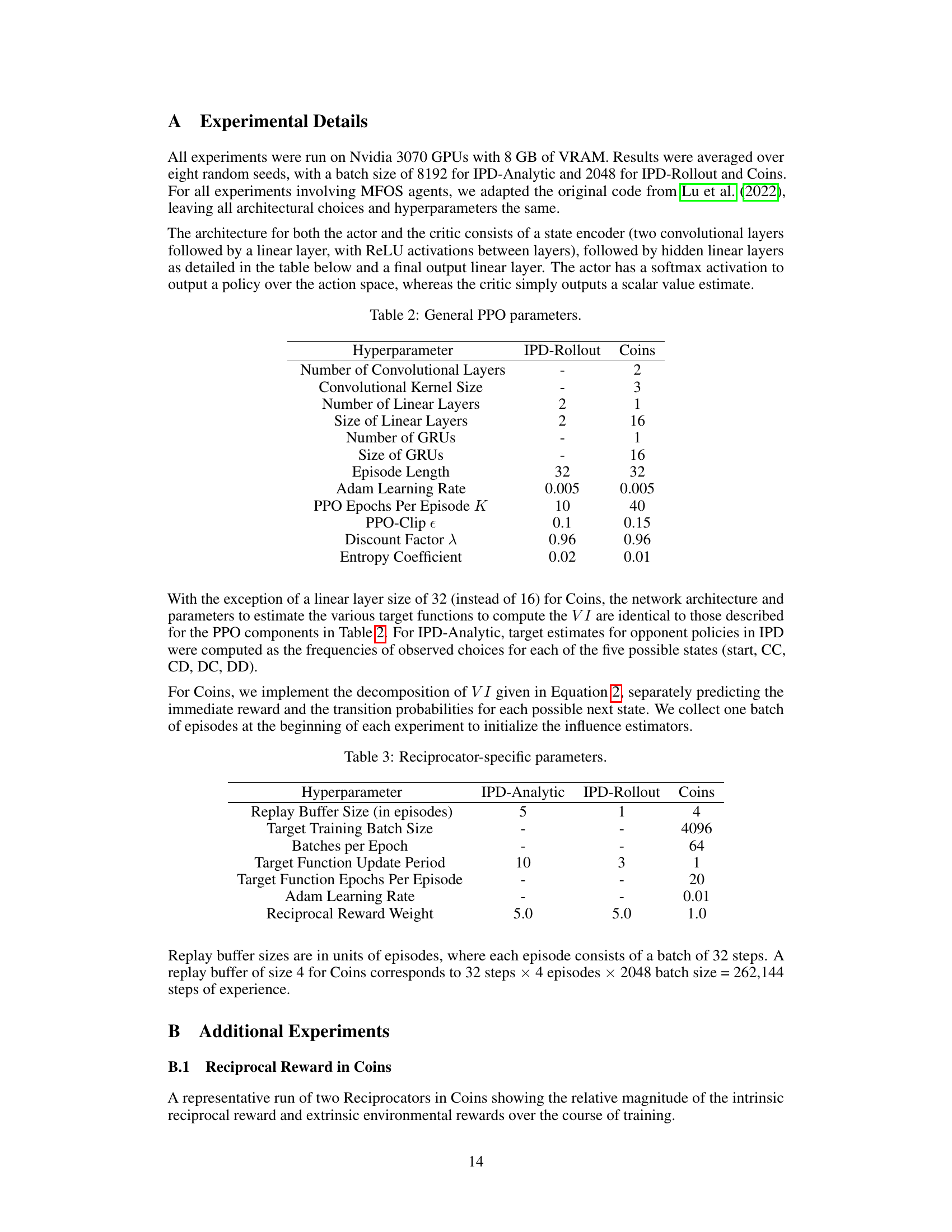

This table lists the hyperparameters specific to the Reciprocator agent, including buffer sizes for experience replay, batch sizes for training, target update periods, and the weight given to the reciprocal reward. Different values are shown for the IPD-Analytic, IPD-Rollout, and Coins experiments, indicating parameter tuning for each environment.

Full paper#