↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Online Budgeted Matching (OBM) is a fundamental online optimization problem with various applications. Existing algorithms often rely on simplifying assumptions like small bids or fractional last matching (FLM), which limit their applicability to real-world scenarios with general bids and indivisible resources. This paper tackles the open problem of OBM with general bids, removing the FLM assumption.

The authors propose a novel meta-algorithm called MetaAd that adapts to various algorithms with first-known provable competitive ratios, parameterized by the bid-to-budget ratio. This meta-algorithm is extended to the FLM setting, yielding provable competitive algorithms. MetaAd is shown to recover optimal competitive ratios in special cases (e.g., small bids) and provides a theoretical upper bound on the competitive ratio for any deterministic algorithm without FLM. The authors also extend their analysis to design learning-augmented algorithms for OBM.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on online budgeted matching. It addresses the limitations of existing algorithms by removing restrictive assumptions and providing the first provable competitive algorithm for general bids without the fractional last matching assumption. This opens new avenues for research in online resource allocation and revenue management, particularly in settings with indivisible resources.

Visual Insights#

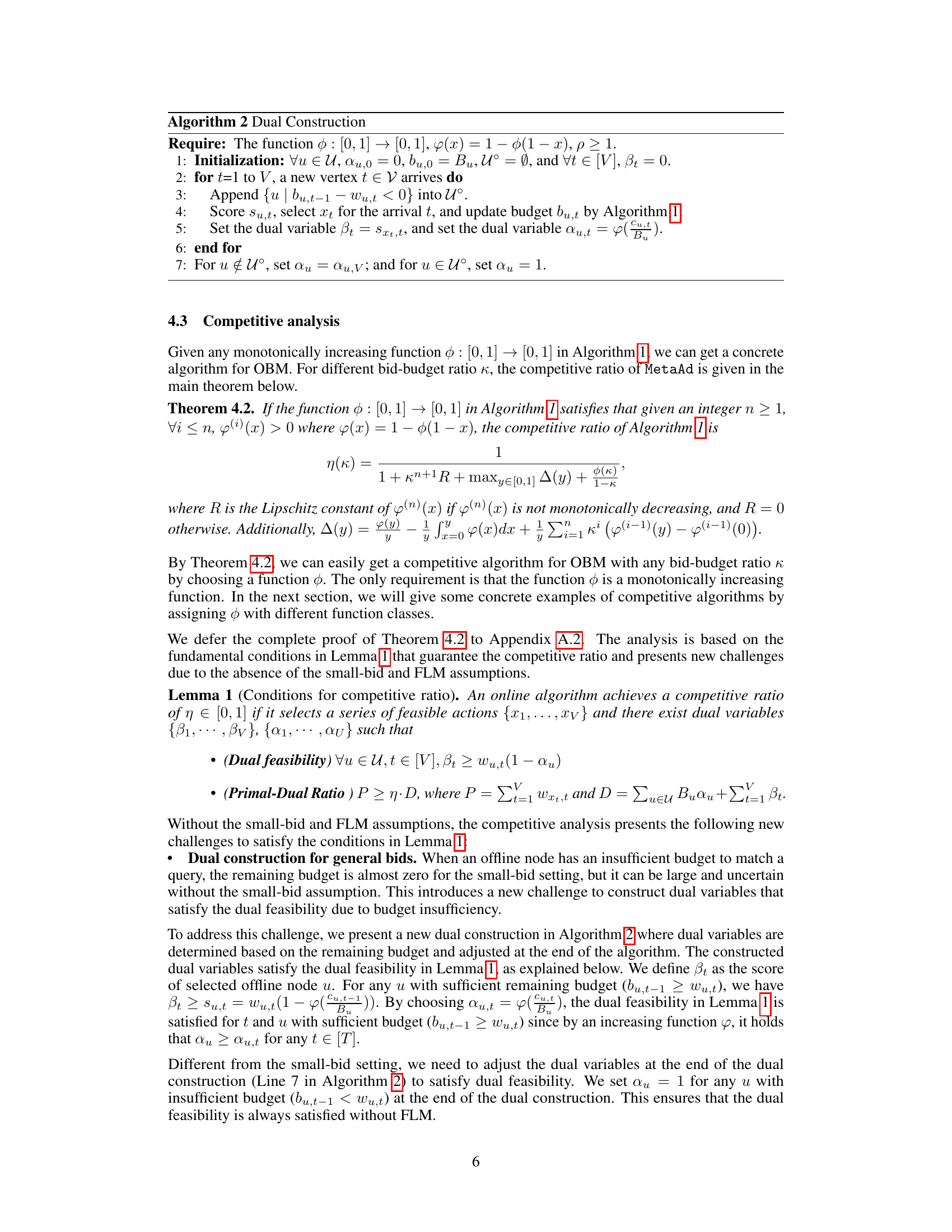

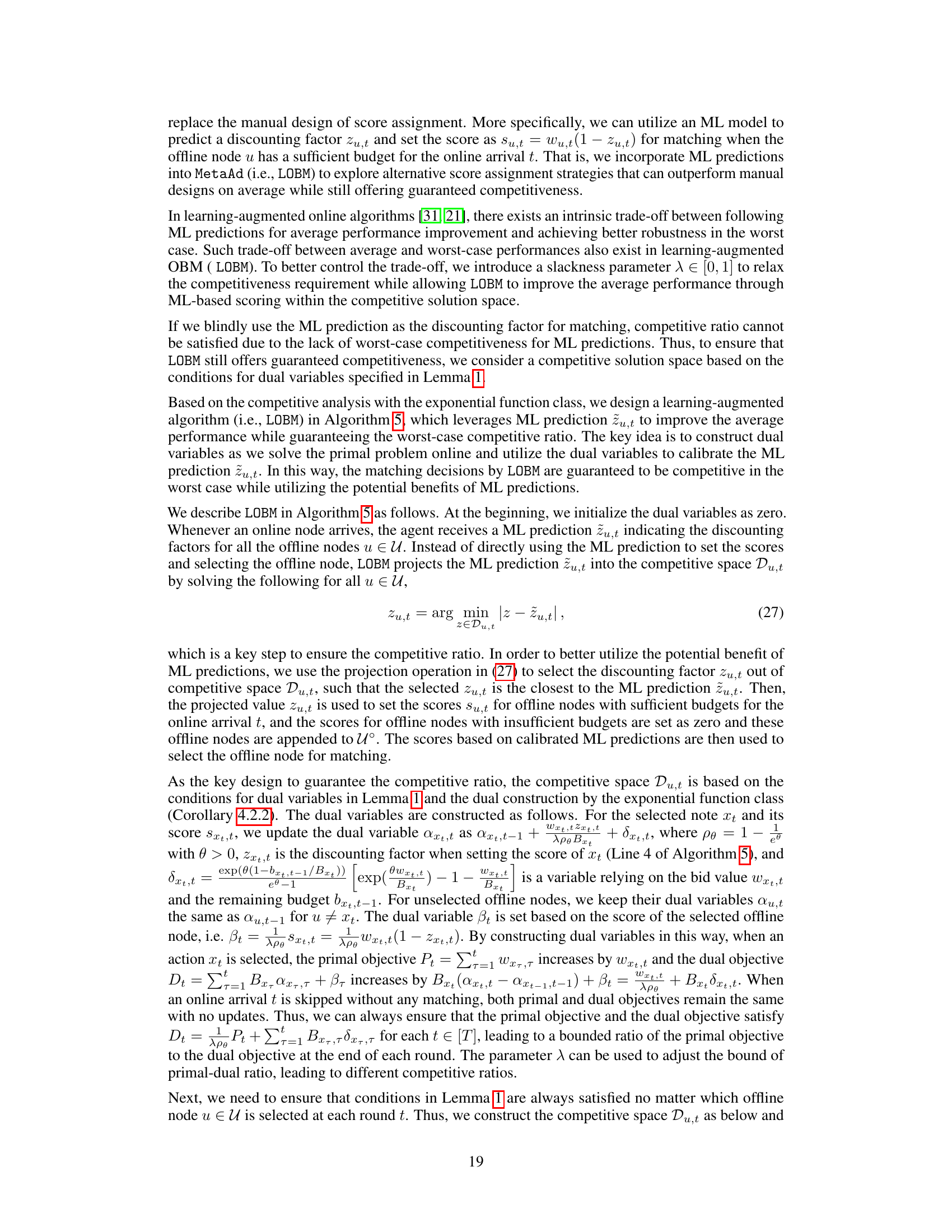

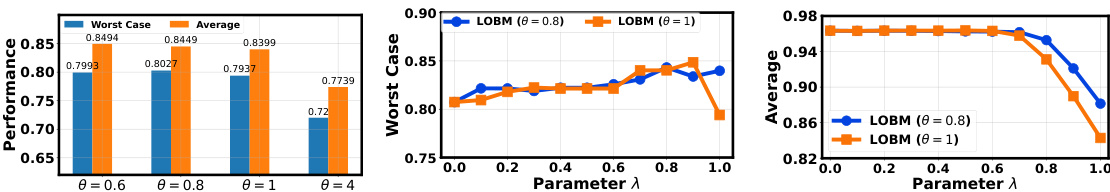

This figure shows the competitive ratios of MetaAd algorithms (with exponential and quadratic discounting functions) without the Fractional Last Matching (FLM) assumption, plotted against different bid-to-budget ratios (κ). The dashed line represents the theoretical upper bound on the competitive ratio. The figure demonstrates how the competitive ratio decreases as κ increases for both algorithms, approaching the theoretical upper bound as κ approaches 1.

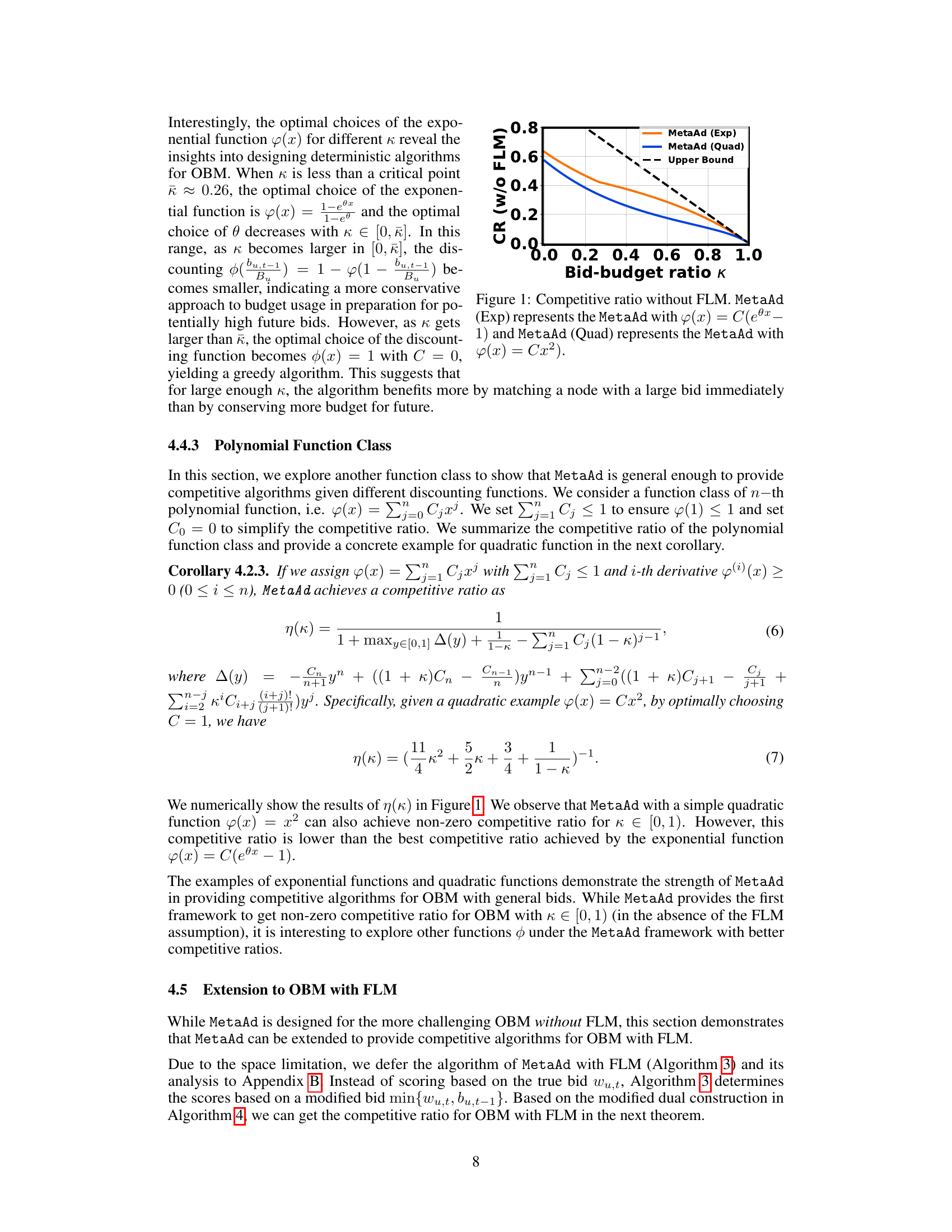

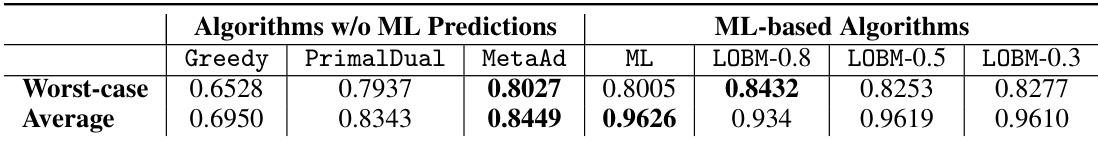

This table presents the worst-case and average normalized rewards achieved by various online algorithms on the MovieLens dataset. It compares algorithms that do not use machine learning (ML) predictions (Greedy, PrimalDual, MetaAd) against algorithms that do use ML predictions (ML, LOBM-0.8, LOBM-0.5, LOBM-0.3). The best performing algorithm in each category (with and without ML predictions) is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

OBM’s Challenges#

Online Budgeted Matching (OBM) presents significant challenges due to its inherent online nature and discrete decisions. The small-bid assumption, frequently used to simplify analysis, is often unrealistic in practice. General bids, where individual bids can be a substantial fraction of a budget, introduce complexities in budget management and significantly impact algorithm design. Further, the Fractional Last Matching (FLM) assumption, which allows for partial bid acceptance, is often inapplicable in real-world scenarios involving indivisible resources. Removing both the small-bid and FLM assumptions creates a considerably more challenging problem. The need for algorithms with provable competitive ratios in adversarial settings adds to the difficulty, requiring novel techniques to establish performance guarantees. Developing effective algorithms that adapt to varying bid-to-budget ratios and handle budget insufficiency without resorting to simplifying assumptions remains a core challenge in advancing OBM research. Learning-augmented approaches show promise but require careful design to ensure both empirical effectiveness and theoretical guarantees.

Meta Algorithm#

The concept of a ‘Meta Algorithm’ in the context of online budgeted matching (OBM) represents a significant advancement. Instead of designing a single algorithm for all scenarios, a meta-algorithm acts as a framework, adapting its behavior based on key parameters like the maximum bid-to-budget ratio (κ). This adaptability is crucial because OBM problems vary widely across different applications. Meta algorithms provide a unified approach, offering a family of algorithms with provable competitive ratios, each tailored to a specific range of κ. This contrasts sharply with traditional methods that often rely on restrictive assumptions (like the small-bid or Fractional Last Matching assumptions). The beauty of the meta-algorithm lies in its flexibility and theoretical rigor. By parameterizing the algorithm’s behavior, it is possible to analyze its performance systematically and guarantee a certain level of optimality (competitive ratio) even in adversarial scenarios. The meta-algorithm approach offers a robust and adaptable solution to OBM, allowing researchers to select the most suitable instance for a given problem instead of being constrained by the limitations of single-algorithm designs. This adaptability is not just theoretically elegant; it also offers a pathway toward better practical performance in diverse real-world applications.

Competitive Ratios#

The concept of “competitive ratios” is central to the analysis of online algorithms, especially in scenarios like online budgeted matching (OBM). Competitive ratio provides a measure of an algorithm’s performance against the optimal offline solution, representing the worst-case ratio of the online algorithm’s total reward to that of an offline algorithm with complete knowledge. In the context of OBM with general bids and without the fractional last matching (FLM) assumption, the authors establish a challenging upper bound of 1-κ on the competitive ratio for deterministic algorithms, where κ is the maximum bid-to-budget ratio. This highlights the difficulty of OBM in these settings. The paper then introduces a meta-algorithm, MetaAd, which adapts to different algorithms and provides provable competitive ratios, demonstrating a flexible approach to tackle the complexities of OBM. The analysis of competitive ratios in MetaAd involves a careful consideration of budget constraints and the impact of bid-budget ratios, leading to the derivation of concrete competitive ratios for different discounting functions, such as exponential and polynomial functions. The work notably extends this analysis to the FLM setting, offering a broader scope of performance evaluation. The focus on competitive ratios under different assumptions and settings provides a comprehensive assessment of algorithm performance and contributes meaningfully to the understanding of online optimization problems.

LOBM Framework#

The LOBM framework, a learning-augmented approach for Online Budgeted Matching (OBM), represents a significant advancement in addressing the inherent challenges of OBM. It cleverly integrates machine learning (ML) predictions with a robust theoretical framework to balance improved average-case performance with guaranteed worst-case competitiveness. The key innovation lies in the projection of ML predictions into a carefully designed competitive solution space. This ensures that even with potentially unreliable ML predictions, the algorithm remains provably competitive. By introducing a slackness parameter, LOBM provides a tunable trade-off between worst-case guarantees and the ability to exploit the benefits of accurate ML predictions. This framework offers a principled way to leverage the power of ML while retaining the crucial theoretical underpinnings of OBM algorithms, paving the way for more practical and effective solutions in real-world settings.

Future of OBM#

The future of Online Budgeted Matching (OBM) research is ripe with exciting possibilities. Addressing the limitations of current algorithms that rely on restrictive assumptions like small bids or fractional last matching is crucial. Developing algorithms that handle general bids effectively in adversarial settings while maintaining provable competitive ratios will be a major focus. Incorporating machine learning (ML) techniques offers significant potential for improving average performance, but careful consideration of worst-case guarantees and robustness against adversarial inputs is vital. Exploring the impact of different discounting functions and designing adaptive algorithms that dynamically adjust strategies based on the problem’s characteristics is key. Considering real-world applications beyond online advertising, such as resource allocation and revenue management, will further expand the field. Ultimately, a more holistic approach that combines theoretical guarantees with practical performance and ethical considerations will shape the future of OBM.

More visual insights#

More on figures

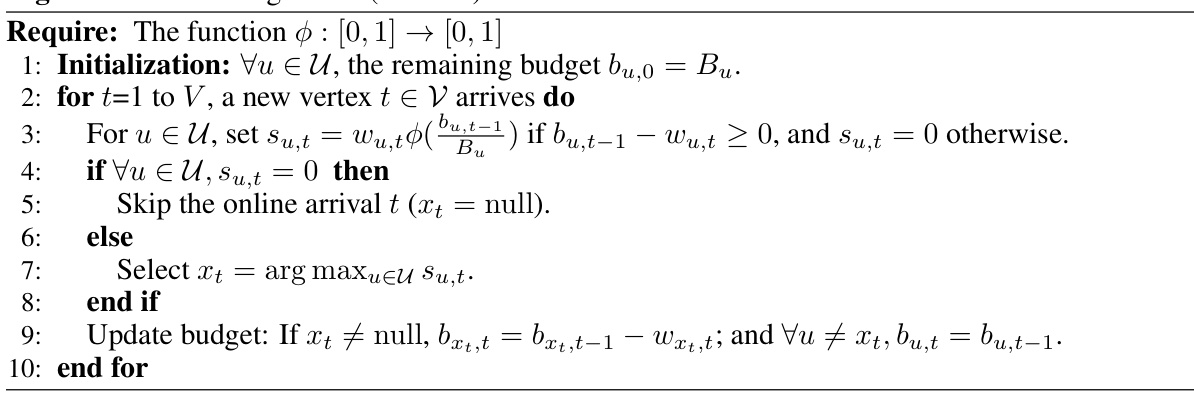

The figure shows the competitive ratios of different algorithms for online budgeted matching with the fractional last match (FLM) assumption. The x-axis represents the bid-to-budget ratio (κ), and the y-axis represents the competitive ratio. The figure compares the performance of MetaAd (using an exponential function), the algorithm from Buchbinder et al. (2007), and a greedy algorithm. It highlights how the competitive ratio changes as the bid-to-budget ratio increases, demonstrating the impact of the bid-to-budget ratio on algorithm performance.

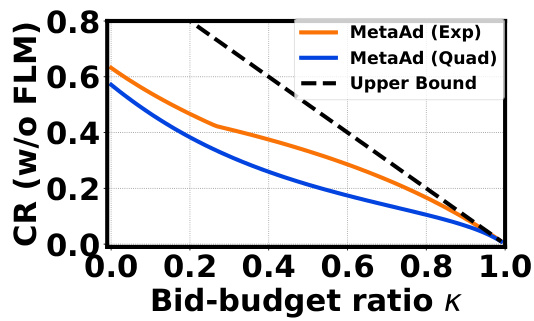

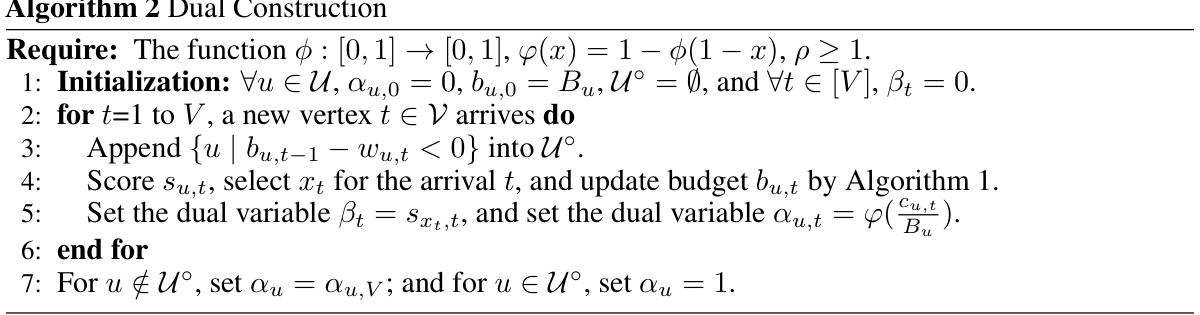

This figure illustrates how MetaAd and LOBM differ in their scoring strategies. MetaAd uses a discounting function φ applied to the remaining budget and bid value of each offline node to determine a score. In contrast, LOBM incorporates machine learning (ML) predictions to adjust the scores. The ML model predicts a discounting factor zu,t for each node, which is then projected onto a competitive solution space to ensure the algorithm maintains a competitive ratio. The final score for each node in LOBM is calculated as Wu,t(1 - zu,t), balancing the benefit of large bids with budget conservation. The figure shows that both algorithms select the node with the highest score.

The figure shows the competitive ratios of MetaAd algorithm for online budgeted matching (OBM) without the fractional last match (FLM) assumption. The x-axis represents the bid-to-budget ratio (κ), ranging from 0 to 1. The y-axis shows the competitive ratio, indicating the algorithm’s performance relative to the optimal offline solution. Two variants of MetaAd are presented: one using an exponential discounting function (MetaAd (Exp)) and another using a quadratic function (MetaAd (Quad)). The figure also includes the theoretical upper bound on the competitive ratio for any deterministic algorithm in this setting. The graph illustrates how the competitive ratio of MetaAd varies with different discounting functions and as the bid-to-budget ratio increases.

The figure shows the competitive ratios of different algorithms for online budgeted matching (OBM) without the fractional last match (FLM) assumption. The x-axis represents the bid-to-budget ratio (κ), and the y-axis represents the competitive ratio. The plot compares MetaAd (using both exponential and quadratic discounting functions) with an upper bound on the competitive ratio. It demonstrates that MetaAd achieves a competitive ratio that is close to the upper bound, particularly for smaller bid-to-budget ratios.

This figure shows the competitive ratios of different algorithms for online budgeted matching (OBM) without the fractional last match (FLM) assumption. The x-axis represents the bid-to-budget ratio (κ), and the y-axis represents the competitive ratio. The figure compares the performance of MetaAd with two different discounting functions (exponential and quadratic) against the theoretical upper bound. It demonstrates that MetaAd achieves a competitive ratio better than 1-κ, with the performance varying with the bid-to-budget ratio and the choice of discounting function.

More on tables

This table presents the worst-case and average normalized rewards achieved by different algorithms on the MovieLens dataset. It compares algorithms without machine learning (ML) predictions (Greedy, PrimalDual, MetaAd) against ML-based algorithms (ML, LOBM with different lambda values). The best results for both categories (with and without ML) are highlighted, showcasing the relative performance of each approach in terms of both average reward and worst-case performance.

This table presents the worst-case and average normalized rewards achieved by various algorithms on the MovieLens dataset. It compares algorithms that do not use machine learning (ML) predictions (Greedy, PrimalDual, MetaAd) against ML-based algorithms (ML, LOBM with different lambda values). The best results for each category (with and without ML) are highlighted in bold, indicating the superior performance of certain methods under different evaluation metrics.

This table presents the worst-case and average normalized rewards achieved by different algorithms on the MovieLens dataset. The algorithms are categorized into those without machine learning (ML) predictions (Greedy, PrimalDual, MetaAd) and those using ML predictions (ML, LOBM-0.8, LOBM-0.5, LOBM-0.3). The best-performing algorithms in each category (worst-case and average) are highlighted in bold. The results show a comparison of performance between algorithms with and without ML components, illustrating the impact of incorporating ML predictions on both worst-case robustness and average performance.

This table compares the worst-case and average rewards of different algorithms for the VM placement problem. It shows the performance of algorithms without machine learning (ML) predictions (Greedy, PrimalDual, MetaAd) and algorithms with ML predictions (ML, LOBM with different λ values). The rewards are normalized by the optimal rewards. LOBM-λ refers to the learning-augmented algorithm LOBM using a slackness parameter λ.

Full paper#